The Late Gravettian and Szeleta Cave, northeast Hungary

Transcript of The Late Gravettian and Szeleta Cave, northeast Hungary

lable at ScienceDirect

Quaternary International xxx (2015) 1e10

Contents lists avai

Quaternary International

journal homepage: www.elsevier .com/locate/quaint

The Late Gravettian and Szeleta Cave, northeast Hungary

Gy€orgy Lengyel a, *, Zsolt Mester b, P�eter Szoly�ak c

a University of Miskolc, Department of Archaeology and Prehistory, 3515 Miskolc-Egyetemv�aros, Egyetem utca 1, Hungaryb E€otv€os Lor�and University, Institute of Archaeological Sciences, 1088 Budapest, Múzeum krt. 4, Hungaryc Herman Ott�o Museum, Pannon Sea Repository of Geological and Natural History, 3529 Miskolc, G€orgey Artúr u. 28, Hungary

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:Available online xxx

Keywords:Late GravettianDeveloped SzeletianBifacial technologyLeaf-shaped tools

* Corresponding author.E-mail addresses: [email protected] (G. Le

(Z. Mester), [email protected] (P. Szoly�ak).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.09.0141040-6182/© 2015 Elsevier Ltd and INQUA. All rights

Please cite this article in press as: Lengyel, Ghttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.09.01

a b s t r a c t

The archaeological sequence of Szeleta Cave, northeast Hungary, had represented the development of abifacial leaf-shaped point lithic industry between the late Middle Palaeolithic and the Upper Palaeolithicwith the evolution of Early Szeletian into the Developed Szeletian culture. In the 1990s, a hypothesisemerged that reconsidered the Developed Szeletian and related the artifacts with a Gravettian that usedbifacial leaf point technology in Eastern Central Europe. Unfortunately, details on artifact types remainedunpublished, which could have supported the Gravettian thesis. To test this hypothesis, we undertook atypological analysis of the lithic assemblages from the lowermost to the uppermost stratigraphicoccurrence of Gravettian tool types. Our analysis found the Gravettian thesis supportable. We argue forclassifying Layers 5 and 6 of Szeleta Cave Late Gravettian, among which Layer 6 could represent a LateGravettian with leaf points. We claim that the bifacial tool technology could have been an integral part inthe Eastern Central European Late Gravettian archaeological record.

© 2015 Elsevier Ltd and INQUA. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Over several decades in the archaeological research of EasternCentral Europe, the sequence of Szeleta Cave represented thedevelopment of a bifacial leaf-shaped point lithic industry betweenthe late Middle Palaeolithic and the Upper Palaeolithic (Kadi�c, 1916,1934; Hillebrand, 1935; Mottl, 1938; G�abori, 1953; V�ertes, 1968;Allsworth-Jones, 1986; Ringer, 1989).

Prior to the 1950s, the lithic industries of Szeleta representedthe local development of the Solutrean (Kadi�c, 1916, 1934;Hillebrand, 1935; Mottl, 1938; G�abori, 1953). �Cervinka in the1920s (Valoch, 1996), and later Pro�sek (1953) proposed to use theterm Szeletian instead of Solutrean. Since the 1960s Szeleta Cavewas widely known as the eponymous site of the Szeletian. TheSzeletian culture, at Szeleta Cave, had two phases: the Early Sze-letian and the Developed Szeletian (V�ertes, 1968; Allsworth-Jones,1986). Svoboda and Sim�an (1989) and Sim�an (1990) broke thetraditional interpretation of the archaeological sequence andproposed to reclassify the Developed Szeletian industry into aspecial type of Gravettian that produced bifacial leaf points (BLP).

ngyel), [email protected]

reserved.

., et al., The Late Gravettian a4

Gravettian tool types, such as the Gravette point and the backedbladelet, were always noticed in the lithic inventories of Szeleta,but were never considered an integral part of the BLP industrybefore. Most probably the similarity to the lithic assemblage ofTren�cianske Bohuslavice in Slovakia (B�arta, 1988), and P�redmostíin the Czech Republic (Absolon and Klíma, 1977) supported theGravettian thesis. Sim�an (1990, 1995), however, did not presentthe Gravettian tools in details, neither their frequency in the as-semblages of Szeleta layers. This was due to that the exact strat-igraphic and spatial position of the finds was hardly demonstrableuntil the years of 2000s. Difficulties in find positioning ledAllsworth-Jones (1986) and Adams (1998) to simplify the archaeo-stratigraphy and study the artifacts by two broad stratigraphicunits following Kadi�c (1916): “lower” and “upper” levels. Due tothe same difficulty, the review of Svoboda and Sim�an (1989) reliedon no more than 10% of the total 2000 items recovered by Kadi�c(1916). Likely, Sim�an (1990, 1995) based the Gravettian thesis onthe same sample, too. Meanwhile, Adams (1998, 2009a) created acontradiction in the typological data by identifying only a singleGravettian tool, a backed blade, in the “upper levels” of Szeleta.Until now, the contradictions in interpreting the relation betweenthe Gravettian tools and Szeletian finds remained uncovered indetails. Due to a handwritten find inventory made by Kadi�c, whichis currently stored at the Hungarian National Museum archives(Ringer and Mester, 2000; Mester, 2002), a detailed

nd Szeleta Cave, northeast Hungary, Quaternary International (2015),

G. Lengyel et al. / Quaternary International xxx (2015) 1e102

reconsideration of the Gravettian finds and their relation to theBLPs can be undertaken. Our aim with this paper was to test theintegrity of the Gravettian thesis (Sim�an, 1990).

2. Setting

Szeleta Cave, 60 m long, is located in the eastern Bükk Moun-tains, 349 m asl (Fig. 1). The cave was divided into seven sections:Entrance (A), Hall (B), Main Corridor front (C), Main Corridor rear(D), Side Corridor front (E), Side Corridor rear (F), and the Stalag-mite Cavity (G) (Fig. 2) (Kadi�c, 1916; Mester, 2002).

Kadi�c (1916) begun the first excavation in 1906 and conductedseven further seasons until 1913. After Kadi�c, a few short campaignswere carried out in 1928, 1936, 1947, 1966, 1989, 1999, 2004, 2007,and 2012 (Mester, 2002; Adams and Ringer, 2004; Lengyel et al.,2008e2009; Ringer, 2008e2009; Mester et al., 2013).

Kadi�c (1916) found the stratum thickest in the Hall (12.5 m) anddistinguished six Pleistocene layers (Fig. 3). Arbitrary spits of0.50 m divided further the layers. Spit numbering went from top tobottom with roman numerals, while layer numbering in reverswith Arabic numerals (Kadi�c, 1916; Mester, 2002). Horizontally,Kadi�c applied a grid of 2 � 2 m squares to divide the area of thecave.

Layer 2, the lowermost with artifacts, was exposed in the Halland the Main Corridor. Its greatest thickness was 5.0 m in the Hall.

Fig. 1. Location of

Please cite this article in press as: Lengyel, G., et al., The Late Gravettian ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.09.014

This layer covered the bedrock, except in the Hall, where anarchaeologically sterile pebble layer lay underneath. Layer 2 con-tained two sublayers (2a and 2b) in the Hall, which yieldedMousterian finds (V�ertes, 1965; Mester, 1994; Lengyel et al.,2008e2009). From the upper level of Layer 2, a few bifacial toolswere designated with the Middle Palaeolithic B�abonyian (Ringerand Mester, 2000). Radiocarbon measurements on cave bearbones from the upper border of Layer 2 indicated that this layer isolder than 40 ka BP (Adams and Ringer, 2004; Lengyel and Mester,2008). Further bone samples of cave bear from deeper levels ofLayer 2 inside the cavewere measured older than 50 ka BP (Lengyelet al., 2008e2009).

Layer 3, exposed all over the cave, yielded the Early Szeletianfinds. The maximum thickness of Layer 3 in the Hall was 3.50 m,while in the corridor 1.50 m. Eroded rock debris, animal bones,and lithics indicated admixture within the matrix (Kadi�c, 1916;Allsworth-Jones, 1978; Lengyel and Mester, 2008; Adams,2009b). Later, radiocarbon dates from Layer 3 ranging from 26 to11 ka BP in erratic chronological order also referred to post-depositional disturbance in Layer 3 (Adams and Ringer, 2004;Lengyel and Mester, 2008). Layer 3 included three sublayers inthe Hall, 3a, 3b, and 3c, which Kadi�c (1916) identified hearthlayers. Today Layer 3 is the uppermost sediment that still isavailable in the cave. All layers above, 4, 5, and 6, were completelyremoved.

Szeleta Cave.

nd Szeleta Cave, northeast Hungary, Quaternary International (2015),

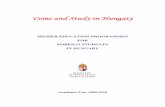

Fig. 2. The plan of Szeleta Cave. A e Entrance, B e Hall, E e Side Corridor front, F e

Side Corridor rear, C e Main corridor front, D e Main corridor rear, G e StalagmiteCavity, 2012 e the trench of the excavation in 2012. (Modified after Kadi�c, 1916, Taf.XIII).

G. Lengyel et al. / Quaternary International xxx (2015) 1e10 3

Layer 4, found over the entire area of the cave, was 0.50 m thick.This represented the Early Szeletian (V�ertes, 1965, 1968), and latelythe Developed Szeletian (Ringer et al., 1995). The age remainedundetermined by radiocarbon dates due to being completelyremoved from the cave by Kadi�c (Mester, 2002).

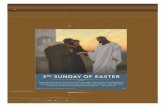

Fig. 3. The stratigraphy of Szeleta Cave. (

Please cite this article in press as: Lengyel, G., et al., The Late Gravettian ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.09.014

Layer 5 lay only in the two corridors with a maximum thicknessof 0.50 m. It yielded the Developed Szeletian, and similarly to Layer4 its age remained undetermined by radiocarbon dates.

Layer 6 was the uppermost Pleistocene layer, found all over thecave. It yielded most of the Developed Szeletian material. Layer 6was light grey, turning gradually yellow in the Side Corridor (Layer6b), in the Entrance, and on the terrace of the cave (Layer 6a), too.Several “hearths” extended in this layer (Ringer and Szoly�ak, 2004).Layer 6's thickness was between 0.5 and 1.0 m in the cave. The layerbecame significantly thicker from the Entrance towards the terrace.Adams and Ringer (2004) obtained a radiocarbon date ~22 ka BP oncharcoal from the Entrance of Layer 6a, but the sample mostprobably derived from the collapsed section of the earlier excava-tions (Lengyel and Mester, 2008).

The fauna of all strata contained primarily cave bear, consistingnearly 99% of the total number of bones. Besides the cave bear,other species were present only with a few fragments. These boneswere not specified to levels within the layers unlike the lithic ar-tifacts. In Layer 2, mammoth, cave lion, cave hyena, wolf, fox, andred deer were found. Layer 3 fauna was similar to Layer 2, butadditionally contained giant deer, and did not contain mammothand red deer. In Layer 4, hyena andwolf boneswere found along thecave bear. Layer 5 included only cave bear remains. Layer 6, 6a, and6b together yielded the widest spectrum of species: giant deer, fox,ibex, horse, wolf, lynx, rein deer, chamois, and vulture. The wholefauna from Layer 2 to Layer 6was dated simply to theMiddleWürm(J�anossy, 1986; V€or€os, 2000), the comprehensive re-evaluation ofwhich has never been undertaken. This is due to the fragmentarystate of the bone collection other than cave bear, the identificationof which could be erratic. For instance, elk bones were mistakenlyclassified giant deer in the Hungarian Upper Pleistocene vertebratefaunal sequence until the 1970s (M�esz�aros and V�ertes,1955; Dobosiand V€or€os, 1979).

3. Materials and methods

The results presented herewere obtained from data collected byone of us (Z. M.) from the collection recovered by Kadi�c in1906e1913 during the years between 1988 and 1998. This collec-tion yielded the greatest lithic assemblage, 2000 items, recoveredby a uniform methodology. The finds are stored at the HungarianNational Museum (HNM) in Budapest, Herman Ott�o Museum(HOM) in Miskolc, and National Historical Museum of Transylvaniain Cluj-Napoca, Romania. We did not include material retrievedwith methods different from that applied by Kadi�c (Sa�ad, 1929;Sa�ad and Nemesk�eri, 1955; V�ertes, 1968; Allsworth-Jones, 1978)and those still unpublished (Ringer, 2008e2009).

Modified after Kadi�c, 1916, Taf. XIV).

nd Szeleta Cave, northeast Hungary, Quaternary International (2015),

Table 1The lithic tool typology by layers and sections of Szeleta.

Cave section B E C D

Layer 6 4 3 6 5 4 6 5 4 3 6 5 4 3

End-scraper 7 2 8 2 1 1Burin 2 2 5 2 1 1Borer 1 1Truncation 2 1 2 1Retouched blade 8 5 11 1 1 1 3 2Retouched bladelet 2Retouched flake 3 4 1 1Backed bladelet 3 2 1Retouched point 1 1 1Gravette 1 1Microgravette 2 1Shouldered point 1 1 1Leafpoint 3 2 6 2 4 2 10 2Bifacial fragment 8 2 23 1 1 1 4 8 7 4 1 1 13Unfinished bifacial 9 1 3 1 1 2 1Side-scraper 2 2 1Notch, denticulate 2 4 11 1Total 39 17 81 8 9 5 18 3 13 9 17 8 3 18

G. Lengyel et al. / Quaternary International xxx (2015) 1e104

To locate the finds in the stratigraphy and in the area of the cave,we relied on original documents: 1) the handwritten find inventoryof Kadi�c, 2) unpublished maps of the cave areas with the grid, andthe drawings of the stratigraphic section stored at the HungarianGeological and Geophysical Institute (Mester, 2002, 2007).

Originally, each stone artifact bears an ink written identitynumber. This number represents the artifact in the list of the findinventory, in which Kadi�c registered the finding place of eachartifact by the stratigraphic position (layer and spit number) and bysquare (Mester, 2002, 2007). Using the original documents wascrucial, because Kadi�c changed the numbering of the grid squareson the cave plans for the final publication in 1916 (Mester, 2002).Therefore, square numbers in the inventory do not match those areon the published maps.

We recovered the origin of 1478 artifacts out of the 2000specimens listed by Kadi�c. Of the 1478 artifacts, we excluded arti-facts found in pits and Holocene deposits. Our revision focused onthe Gravettian lithic artifacts and their association with the rest ofthe assemblages in the same stratigraphic units. This included eachlayer between level VII of Layer 3 and Layer 6. Approximately thehalf of the original assemblage, 1031 knapped lithics, was provenreliable to take part in this analysis.

To identify Gravettian tools we followed the type list of Demarsand Laurent (1992), and further studies on Gravettian tool typology(Soriano, 1998; Pesesse, 2008, 2011; Moreau, 2009, 2012; Simonet,2011). Gravettian lithic tool types herein are the Gravette point,microgravette point, backed bladelet, pointed retouched blade,fl�echette, and the shouldered point. These types are chief charac-ters of the Gravettian in Eastern Central Europe (Sobczyk, 1995;Kozłowski, 2013, 2015; Lengyel, 2014, 2015; Wilczy�nski et al.,2015b).

We created general typological groups for the Upper Palaeolithic(UP) tool types: end-scraper, burin, borer, and truncation. The soleMiddle Palaeolithic (MP) type was the side-scraper. Notches, den-ticulates, and edge-retouched specimens were regarded chrono-logically neutral types, unless they were made of blade, which werelated to UP technology.

Bifacial leaf points (BLP) were divided into two types followingthe criteria of Mester (2010, 2014): 1) symmetrical with alternatingretouch, and 2) asymmetrical with alternate retouch. Latter rep-resents typical late MP shaping method (Kot, 2013). Our analysisrelied solely on the classifiable, mostly the complete specimens.Furthermore, we distinguished fragments, and incomplete speci-mens. Fragments include tools having invasive bifacial shaping.These did not retain the original form of the bifacial tool. Incom-plete bifaces category included those specimens seem to have beendiscarded before accomplishing the final form.

A significant portion of the artifacts bore pseudo-retouch, mostprobably due to geological and biological agents (Allsworth-Jones,1978; Adams, 2009a, 2009b; Lengyel et al., 2008e2009). Amarker of such damage is the irregularly appearing alternatingretouch, denticulation, notches, from semi-abrupt to abrupt angleon the edges, alike found by trampling experiments (McBreartyet al., 1998). This edge damage often accompanied surface wear

Table 2The frequency of knapped products by layers and sections of Szeleta.

Cave section B E

Layer 6 4 3 6 5 4

Flake 89 63 189 2 8 6Blade 63 44 103 1 1 11Bladelet 4 2 10 4Plaquette 1 2Debris 27 21 86 3 8 3Total 184 130 390 10 17 20

Please cite this article in press as: Lengyel, G., et al., The Late Gravettian ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.09.014

that blurred the edges of and scar ridges. We excluded these arti-facts from the tools.

4. Results

We did not find Gravettian tool types in the Entrance of the cavein the 1906e1913 collection. Mostly other types, such as edgeretouched and denticulated tools, a few BLP and bifacial fragments,end-scrapers, and burins were found. The rear of the Side Corridorexcept three artifacts from Layer 5, two of which are BLP fragments,was archaeologically sterile. Chamber G was filled up with thesediment of Layer 2 and no finds later than Mousterian were found(Lengyel et al., 2008e2009). Because no Gravettian types appearedin these sections of the cave, the finds from there were excludedfrom our analysis.

We found Gravettian types in the Hall, Side Corridor front,Main Corridor front and rear of the cave (Table 1). The latestfieldwork on the yet unexcavated terrace recovered a few knap-ped artifacts including a small fl�echette from the top of Layer 6ain 2012 (Fig. 4: 10). This excavation opened only one squaremeter in 5 cm thickness of Layer 6a that was abundant of bonesand rock debris (Mester et al., 2013). An AMS date on a cave bearbone found with the fl�echette resulted in 25 222 ± 121 BP(DeAe2625) (Fig. 5).

The Gravettian finds inside the cave appeared first in theupper portion of Layer 3 (level VII) in the Hall. Layer 3 Gravet-tian tools are backed bladelets (Fig. 4: 5) and retouchedblade points. From within the same levels of Layer 3, thegreatest proportion of the assemblage consisted of fragmentedbifacial tools. Besides bifaces, we found the dominance of UPtool types and blades in the toolkit of unifacial tools (Tables 2and 3).

C D

6 5 4 3 6 5 4 3

33 3 26 7 26 7 4 1118 2 14 1 7 4 4 171 1 1 12 2 1 1

13 2 14 8 14 4 1 1667 7 57 16 48 15 10 46

nd Szeleta Cave, northeast Hungary, Quaternary International (2015),

Table 3Blanks of the tools by layers and sections of Szeleta.

Cave section B E C D

Layer 6 4 3 6 5 4 6 5 4 3 6 5 4 3

Flake 13 2 21 1 2 2 1 1 1 1 1Blade 17 13 28 1 2 5 1 3 1 3 1 3Bladelet 3 4 1 1 1Plaquette 2 2 1Unidentifiable 9 2 27 3 8 3 9 2 7 8 14 4 1 13Total 39 17 81 8 9 5 18 3 14 9 17 8 3 18

Table 4The frequency of raw material in the tool kits of Szeleta assemblages. H e hornstone, LS e limnic silicite, O e obsidian, P e perlite, PT e porphyry tuff, MR emetarhyolite, R e

radiolarite, F e flint.

Layer Raw material Total

H LS O P PT MR R F

6 Gravettian types 6 6UP types 16 2 10 1 1 30Leaf points and fragments 1 1 17 19diverse 5 1 1 7unfinished BLP 3 3bifacial fragment 1 16 17subtotal 22 3 1 53 2 1 82

5 Gravettian types 2 2UP types 2 1 3Leaf points and fragments 1 1 7 1 10unfinished BLP 3 3bifacial fragment 1 1 2subtotal 1 6 12 1 20

4 Gravettian types 3 3UP types 16 2 18Leaf points and fragments 2 2diverse 1 1unfinished BLP 2 2bifacial fragment 12 12subtotal 19 20 39

3 Gravettian types 1 5 6UP types 12 1 22 35diverse 3 1 1 7 2 14unfinished BLP 10 10bifacial fragment 3 38 1 1 43subtotal 20 2 1 82 3 1 109

Total 1 67 5 1 1 167 6 2 250

Table 5Distribution of bifacial leaf points in Szeleta layers.

Layer Bifacial leaf point Total

Asymmetric Symmetric

6 4 17 215 3 5 84 1 1 23 5 1 6Total 13 24 37

G. Lengyel et al. / Quaternary International xxx (2015) 1e10 5

In Layer 4, Gravettian types are a Gravette point, and two frag-ments of shouldered points (Fig. 4: 9). Again, bifacial tool fragmentsare the most numerous, and UP tool types and blades are dominant.Besides the tools, there are three bladelet cores, which correspondto UP laminar technology.

In layer 5, a Gravette point and a shouldered point fragmentrepresent the Gravettian (Fig. 4: 7, 8). Other tool types, which weremade of blades, are rare, and BLP are prevalent.

In Layer 6 (Layer 6, 6a, and 6b together) backed bladelets,microgravettes, and a retouched pointed blade represent theGravettian (Fig. 4: 1, 2, 4, 5, 6). BLP and their fragments rule theassemblage, in the rest of which UP tool types are dominant. Thereare three bladelet cores in this assemblage, too. The blanks ofunifacial tools are again chiefly blades.

In the assemblages, further evidences of UP blade technologyare the crested blade in Layer 6 (1 item) and the neo-crested bladesin Layer 3 (7 items) and in Layer 6 (2 items).

The raw material spectrum of the assemblages are very similar(Table 4). Except Layer 4, the lithics of which consisted of mainlylimnic silicite (LS), each assemblages was dominated by meta-rhyolite (MR) also called quartz-porphyry (V�ertes and T�oth, 1963;Mark�o et al., 2003). LS source is situated 10 km east to the cave atAvas hill in the town Miskolc (Hartai and Szak�all, 2005). Abundant

Please cite this article in press as: Lengyel, G., et al., The Late Gravettian ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.09.014

MR source is located southeast 3 km of the cave (Szoly�ak, 2011;T�oth, 2011). Besides LS and MR, there is a piece of red porphyrytuff originated 1.8 km of the cave, a few obsidian of Carpathian type2, and a perlite, both from TokajePre�sov Mountains 50 km east-wards in Hungary (Bir�o et al., 2000). There are a few radiolariteitems, the closest source of which is in East Slovakian river gravels(P�richystal, 2013). Flint in the assemblage is the Jurassic type fromKrak�oweCzestochowa plateau north to the Upper Vistula basin inPoland.

The Gravettian types were made mainly of MR in Layer 3 and 6,but in Layer 4 and 5 their raw material are mainly LS. The rawmaterial of UP types corresponds to that of the Gravettian types ineach layer except Layer 6 where LS outnumber MR. In each layerbifacial tools were dominantly made of MR.

From Layer 3 upper levels to the top of Layer 6 we found nosignificant correlation between the stratigraphic distribution offlakes and blades (rs ¼ e 0.005, p ¼ 0.889), Gravettian types versusother tool types (rs ¼ 0.002, p ¼ 0.970). However, the symmetricalBLP proportion growth in the upper portion of the stratigraphy wassignificant (rs ¼ �0.453, p ¼ 0.005) (Table 5), so did the decrease ofthe bifacial fragments from Layer 3 upwards Layer 6 (rs ¼ 0.553,p ¼ 0.000).

nd Szeleta Cave, northeast Hungary, Quaternary International (2015),

Fig. 4. Gravettian types in the Szeleta assemblages. 1, 6 e pointed retouched blade, 2, 4 e microgravette, 3, 5 e backed bladelet, 7 e Gravette point, 8, 9 e shouldered points, 10 e

fl�echette. The origin of the finds: 6 e B, Layer 6; 9 e B, Layer 4; 1, 2, 4 e E, Layer 6; 3 e C, Layer 3; 5 e D, Layer 6; 7, 8 e D, Layer 5; 10 e Szeleta terrace, Layer 6a.

G. Lengyel et al. / Quaternary International xxx (2015) 1e106

5. Discussion

The composition of Gravettian tools showed a minor change inthe sequence. Layer 3 specimens, the backed bladelets and pointedretouched blades, could fit Early Gravettian typology for instance atWillendorf II Layer 5 (Moreau, 2009, 2012), in which the fl�echetteand the microgravette are characteristic, too. In the Carpathianbasin, the presence of Early Gravettian, however, is dubious(Verpoorte, 2002, 2004; Lengyel, 2014, 2015), and most Gravettiansites seem to be datable to the Late Gravettian ~25e20 ka BP(Kozłowski, 2013). Despite the Early Gravettian, all the tool typesmentioned above are known in Late Gravettian assemblages, co-appearing primarily with shouldered points, and occasionallywith bifacial leaf points (Wilczy�nski, 2007; �Za�ar, 2007; Kozłowski,2008; Oliva, 2009; Lengyel, 2015; Wilczy�nski et al., 2015a, 2015b).

Relying on the morphological analyses of BLPs (Mester, 2010,2014), the asymmetrical shape and alternate retouch, which isthe character of Layer 3 BLP assemblage, is common in the Szeletian(Nerudov�a and Neruda, 2004), B�abonyian (Ringer, 1983), Janko-vichian (Mester, 2014), and Late MP assemblages (Kot, 2013). Theprevalence of asymmetrical bifaces in Szeleta Layer 3 Levels VIeVIImay indicate that the co-appearance of Gravettian artifacts and BLPcan be the result of admixture between Szeletian and Gravettian, sodo the laminar technology that is uncommon in Szeletian assem-blages (Kaminsk�a et al., 2011). Due to the low archaeologicalintegrity of Layer 3, including radiocarbon dating and the ambiguityof Gravettian occupations prior to 26 ka BP in the Carpathian Basin,we cannot correlate Layer 3 lithic material with Early Gravettian.The features we found likely indicate that Layer 3 upper part rep-resents an admixture.

Please cite this article in press as: Lengyel, G., et al., The Late Gravettian ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.09.014

Relying on the tool typology, Layer 4 with the Gravette point andthe shouldered point may represent a classic Late Gravettian(Kozłowski and Sobczyk, 1987; Sobczyk, 1996; Wilczy�nski, 2007;�Za�ar, 2007; Lengyel, 2014, 2015; Wilczy�nski et al., 2015a). Layer 4assemblage, however, similarly to Layer 3, includes a number ofbifacial tool fragments and there are only two classifiable BLPs: anasymmetric and a symmetric specimen. We cannot confirmtherefore that BLPs and the UP Gravettian component of Layer 4 isan assemblage of Gravettian with leaf points.

In Layer 5, but chiefly in Layer 6, symmetrical BLPs outnumberthe asymmetrical specimens that are characteristic to Layer 3(Mester, 2010, 2014). Because symmetrical types made with alter-nating retouch and biconvex cross-section significantly differ fromLayer 3 specimens (Mester, 2010), we suppose these pieces repre-sent a different lithic industry. Although we found no correlationbetween the abundance of Gravettian types and the stratigraphic,we claim that Layer 6 may represent the Late Gravettian withbifacial technology (B�arta, 1988; Kozłowski, 2013).We based this onthe BLP type change, the decreased traits of admixture, and thesame raw material use for Gravettian types and BLP. The raw ma-terial use in the assemblages of Szeleta also is characteristic to theLate Gravettian in Hungary, with the exploitation of mainly localsources (Lengyel, 2014, 2015). The low rate of MR material amongUP types is common in Gravettian context (Lengyel, 2015). Thenearest Gravettian site to Szeleta, Saj�oszentp�eter Margit-kapu-d}ul}o13 km northeast in the Saj�o valley (Ringer and Holl�o, 2001), alsoused MR restrictedly, but out of the three Gravettian types two, amicrogravette and a backed bladelet, are of this material, whilemost of the general UP types were made of local limnic silicites.Besides the typological similarity given by the backed bladelets,

nd Szeleta Cave, northeast Hungary, Quaternary International (2015),

G. Lengyel et al. / Quaternary International xxx (2015) 1e10 7

microgravettes, and a retouched pointed blade, the blade domi-nance in the lithic production and the toolkits fit the Late Gravet-tian technology, too (Wilczy�nski, 2007; �Za�ar, 2007; Lengyel, 2014,2015; Wilczy�nski et al., 2015a, 2015b). We observed, nonetheless,a low frequency of burins at Szeleta, the tool type that often makesup at least 20% of the toolkits in Late Gravettian assemblages(Kozłowski and Sobczyk, 1987; Oliva, 2007; Wilczy�nski, 2007;Nov�ak, 2008). At present, we cannot explain this difference,because the typology of Szeleta assemblages is biased by the fre-quency of BLPs. The bias probably refers to a functional variabilityamong Late Gravettian sites in Central Europe (Kozłowski, 2013).

Gravettian assemblages with BLP are rare in Hungary. One isSaj�oszentp�eter-Nagykorcsol�as, 12 km northeast to Szeleta on theeastern foothills of Bükk Mountains, where Sim�an (1985) dividedthe assemblage into two groups based on typology: a bifacial in-dustry, and a Gravettian assemblage similar to Bodrogkeresztúr-Henye (Lengyel, 2015). Another site could be Hont-Parassa III,130 km west of Szeleta, where a single leaf point was foundtogether with a Gravette point and a few backed bladelets (Dobosiand Sim�an, 2003).

In V�ah valley in western Slovakia, and Moravia in Czech Re-public sites yielded similar assemblages to Szeleta Layer 6, alldated to the Late Gravettian period. Pet�rkovice I lithic assemblage,dated to 21e23 ka BP, contained Gravettian tool types typical tothe shouldered point horizon and a few BLPs (Oliva, 2007; Nov�ak,2008). Tren�cianske Bohuslavice dated to 22e25 (Verpoorte, 2002;

Fig. 5. The section of the 2012 excavation on the terrace of Szeleta. 1 e stone debris ofthe excavation of Kadi�c, 2 e a thin, sterile layer, 3A-C e backfill of Kadi�c excavation, 4 e

Holocene layer with Neolithic and Iron Age shards, 5 e Pleistocene layer, 6 e heavyrock debris; arrow points the sample of radiocarbon dating.

Please cite this article in press as: Lengyel, G., et al., The Late Gravettian ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.09.014

Vla�ciky et al., 2013) yielded also leaf points with fl�echettes andseveral backed bladelets (�Za�ar, 2007). Although there are un-certainties in linking layers and artifacts at Tren�cianske Bohusla-vice due to poor documentation (�Za�ar, 2007), until now B�arta's(1988) view, that BLPs and Gravettian finds belong together, hasnot been convincingly confuted. The latest fieldwork at the sitedated the earliest Gravettian finds to 24.5 ka BP, and found noremnants of Szeletian occupation in the stratigraphy (Vla�cikyet al., 2013). Further evidences for bifacial tool production inLate Gravettian are fragments of BLP at Moravany-Lopata II(Kozlowski, 1998) and Nitra Ie�Cerma�n (Kaminsk�a and Kozłowski,2011). The BLP found at Tren�cianska Turn�a in abundant LateGravettian context, however, were separated as Early UP intrusion(Kaminsk�a et al., 2008). These BLPs seem to have symmetricalshape and bi-convex cross-section due to alternating shapingretouch (Oliva, 2007; �Za�ar, 2007; Svoboda, 2008), which could beequivalent of the bifacial technology found at Layers 6 assemblageof Szeleta Cave. Comparing the shape of BLP from Tren�cianskeBohuslavice, we saw similarity with Szeleta Layer 6 (Fig. 6). Theonly difference that could be striking is the greater size of someBLPs at Szeleta. However, the size spectrum of Tren�cianskeBohuslavice is present in the Szeleta collection.

Far best known instances of bifacial leaf points in the UP inEurope are in Middle Solutrean assemblages dated to the LastGlacial Maximum (LGM) ca. 20.5 ka BP in southwestern France,postdating Gravettian occupations (Renard, 2011). Banks et al.(2009) claimed that BLPs of the Middle Solutrean represent anadaptation to a cold steppe ecological niche. Therefore, the begin-ning of Solutrean is often regarded as a cultural response to harshcondition of the LGM which forced the majority of the NorthernEuropean population to migrate southwards below the 48th lat-itudinal (Strauss, 2015). Besides the BLP, the shouldered point in thehunting armature of the Solutrean could be another similarity withLate Gravettian, although their productions are greatly dissimilar(Aubry et al., 1998). In Eastern Central Europe the few dated sites,Tren�cianske Bohuslavice 22e25 ka BP, Pet�rkovice I 21e23 ka BP,Szeleta terrace 25 ka BP, and Moravany Lopata II 21e24 ka BP alsopost-date Gravettian occupations in a cooling climate that led to thepeak of the LGM (Marks, 2012). Another instance of bifacial tech-nology in the period of Late Gravettian is Kostienki 8 level I inRussia (Flas, 2015). The Late Gravettian chronological positionpredates the Solutrean bifacial technology of southwestern France.However, if glacial conditions indeed played a role in the occur-rence of bifacial tool technology in the UP, then Eastern CentralEurope being closer to the Fennoscandinavian ice sheet may havefaced earlier the ecological consequences of the cooling climate.Wesuspect therefore that an earlier occurrence of bifacial technologycan be reasonable in this region.

Classifying Szeleta Layer 6 into the Late Gravettian with leafpoints makes the term Developed Szeletian doubtful. The twofolddivision of the Szeletian always was hardly explainable in theCentral European archaeological record, because Szeleta cave wasthe only site ever where the two phases of the Szeletian lay insuperposition. At other sites in Hungary, BLP always emerged inpoor lithic assemblages (Dobosi, 1990, 2008e2009), except therecently discovered sites in Cserh�at Mountains 100 km west ofBükk Mountains (P�entek and Zandler, 2013). These assemblagestypologically look similar to the Szeletian in the Czech Republic anddissimilar towhat we found in the “Developed Szeletian” of Szeleta.The dissimilarity is due to the high proportion of flakes in the toolkits, which is a striking character of the Szeletian assemblagesdated to approximately 45e39 ka BP (Kaminsk�a et al., 2011;Nemergut et al., 2012; Połtowicz-Bobak et al., 2013). The Late Sze-letian in Slovakia dated to 33 ka BP, characterized by the Moravany-Dlh�a type broad convex based BLP, also differs from the “Developed

nd Szeleta Cave, northeast Hungary, Quaternary International (2015),

Fig. 6. Shapes of bifacial leaf points from Tren�cianske Bohuslavice (1e7) (after Kaminsk�a, 2014: Obr. 85) and Szeleta Cave (8e14).

G. Lengyel et al. / Quaternary International xxx (2015) 1e108

Szeletian” of Szeleta due to the same reason (Kaminsk�a et al., 2011;Nemergut et al., 2012; Kaminsk�a, 2015).

The archaeological evidences discussed above may support ourand others' (B�arta, 1988; Sim�an, 1990; Svoboda, 2008; Kozłowski,2013; Flas, 2015) argument that Late Gravettian hunter-gatherersin Eastern Central Europe likely used bifacial technology.

6. Conclusion

We found supportable the proposal of Sim�an (1990) that theDeveloped Szeletian at Szeleta cave indeed is the representation ofLate Gravettian occupations. We demonstrated that Layer 3 upperpart could already have been formed during UP occupations, butthe admixture of sediment particles from different periods makesthis claim insecure. Certainly, Layer 3 upper part has a strong UPcharacter due to the proportion of laminar tools, which is unusualin the Szeletian of Eastern Central Europe. In Layer 4, we alsocannot make association between leaf points and Gravettian arti-facts, and the presence of the former type in this layer can also bethe result of admixture. Layer 5 probably, but Layer 6 moreconvincingly can represent a Late Gravettianwith leaf points. Beingaware of the generally low archaeological integrity of Szeleta Cavelayers, we assume that the co-appearance of bifacial leaf points andGravettian artifacts cannot straightforwardly represent admixtureof different cultural relicts. The lack of archaeological evidences forDeveloped Szeletian superposing Early Szeletian elsewhere, the

Please cite this article in press as: Lengyel, G., et al., The Late Gravettian ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.09.014

difference in lithic tool assemblage composition of Szeletian andLate Szeletian assemblages led us to support Sim�an's proposal toabandon the term Developed Szeletian regarding Szeleta Cave. Weargue that a Late Gravettianwith bifacial leaf point productionmustbe considered in the Eastern Central European archaeologicalrecord.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the reviewers' for their comments that helpedimprove this paper. Special thanks go to Ildik�o Horv�ath for the in-formation on the lithic finds from Szeleta Cave stored in Cluj-Napoca, Romania.

References

Absolon, K., Klíma, B., 1977. P�redmostí ein Mammutj€agerplatz in M€ahren. FontesArchaeologiae Moraviae 8. Archeologický Ústav �CSAV v Brn�e, Brno.

Adams, B., 1998. The Middle to Upper Paleolithic Transition in Central Europe. TheRecord from the Bükk Mountain Region. BAR International Series 693.Archaeopress, Oxford.

Adams, B., 2009a. The Bükk Mountain Szeletian: Old and New Views on “Transi-tional” Material from the Eponymous Site of the Szeletian. In: Camps, M.,Chauhan, P. (Eds.), Sourcebook of Palaeolithic Transitions. Methods, Theories,and Interpretations. Springer, New York, pp. 427e440.

Adams, B., 2009b. The Impact of Lithic Raw Material Quality and PosteDepositionalprocesses on Cultural/Chronological Classification: The Hungarian SzeletianCase. In: Adams, B., Blades, B.S. (Eds.), Lithic Materials and Paleolithic Societies.WileyeBlackwell, Chichester, pp. 247e255.

nd Szeleta Cave, northeast Hungary, Quaternary International (2015),

G. Lengyel et al. / Quaternary International xxx (2015) 1e10 9

Adams, B., Ringer, �A., 2004. New C14 dates for the Hungarian Early Upper Palae-olithic. Current Anthropology 45, 541e551.

Allsworth-Jones, P., 1978. Szeleta Cave, the excavations of 1928, and the CambridgeArchaeological Museum collection. Acta Archaeologica Carpathica 18, 5e38.

Allsworth-Jones, P., 1986. The Szeletian and the transition from Middle to UpperPalaeolithic in Central Europe. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Aubry, T., Walter, B., Robin, E., Plisson, H., Ben-Habdelhadi, M., 1998. Le site sol-utr�een de plein-air des Maitreaux (Bossay-sur-Claise, Indre-et-Loire): un faci�esoriginal de production lithique. Pal�eo 10, 163e184.

Banks, W.E., Zilh~ao, J., d'Errico, F., Kageyama, M., Sima, A., Ronchitelli, A., 2009.Investigating links between ecology and bifacial tool types in Western Europeduring the Last Glacial Maximum. Journal of Archaeological Science 36,2853e2867.

B�arta, J., 1988. Tren�cianske Bohuslavice e un habitat gravettien en Slovaquie occi-dentale. L’Anthropologie 92, 173e182.

Bir�o, K.T., Dobosi, V.T., Schl�eder, Z., 2000. Lithotheca e The Comparative Raw Ma-terial Collection of the Hungarian National Museum. Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum,Budapest.

Demars, P.-Y., Laurent, P., 1992. Types d’outils lithiques du Pal�eolithique sup�erieuren Europe. Presses du CNRS, Paris.

Dobosi, V., 1990. Leaf-shaped implements from Hungarian open-air sites. In:Kozłowski, J.K. (Ed.), Feuilles de pierre. Les industries �a pointes foliac�ees duPal�eolithique sup�erieur europ�een. E.R.A.U.L. 42. Universit�e de Li�ege, Li�ege,pp. 175e188.

Dobosi, V.T., 2008e2009. Leaf points in non-Szeletian context. Praehistoria 9e10,71e79.

Dobosi, V.T., Sim�an, K., 2003. HonteParassa III. Orgon�as, Upper Palaeolithic settle-ment. Communicationes Archaeologicae Hungariae 2003, 15e29.

Dobosi, V.T., V€or€os, I., 1979. Data to an evaluation of the finds assemblage of thePalaeolithic paint mine at Lovas. Folia Archaeologica 30, 7e26.

Flas, D., 2015. The Extension of Early Upper Palaeolithic with blade-leaf points(Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician): the issue of Kostienki level I. In:Ashton, N., Harris, C. (Eds.), No Stone Unturned: Papers in Honour of RogerJacobi, London. Lithic Studies Society, London, pp. 49e58. Occasional Paper 9.

G�abori, M., 1953. Solyutreyskaya kul’tura Vengrii (Le Solutr�een en Hongrie). ActaArchaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 3, 1e68.

Hartai, �E., Szak�all, S., 2005. Geological and mineralogical background of thePalaeolithic chert mining on the Avas Hill, Miskolc, Hungary. Praehistoria 6,15e21.

Hillebrand, J., 1935. Die €Altere Steinzeit Ungarns. Archaeologia Hungarica 17.Magyar T€ort�eneti Múzeum, Budapest.

J�anossy, D., 1986. Pleistocene Vertebrate Faunas of Hungary. Developments inPalaeontology and Stratigraphy 8. Elsevier, AmsterdameOxfordeNewYorkeTokyo.

Kadi�c, O., 1916. Ergebnisse der Erforschung der Szeletah€ohle. Mitteilungen aus demJahrbuche der k€oniglichen Ungarischen Geologischen Reichsanstalt 23,161e301.

Kadi�c, O., 1934. Der Mensch zur Eiszeit in Ungarn. Mitteilungen aus dem Jahrbuchder kgl. Ungarischen Geologischen Anstalt 30, 1e147.

Kaminsk�a, L.'., 2014. Stredn�a f�aza mlad�eho paleolitu. In: Kaminsk�a, L.'. (Ed.), Star�eSlovensko 2: paleolit a mezolit, Archaeologica Slovaca Monographiae STASLO,Tomus 2. Archeologický ústav SAV, Nitra, pp. 194e268.

Kaminsk�a, L'., 2015. Szeletian finds from tren�cianske Teplice, Slovakia. Anthro-pologie 53, 203e213.

Kaminsk�a, L'., Kozłowski, J.K., 2011. Nitra I-�Cerm�a�n v r�amci �struktúry osídleniagravettienskej kultúry na Slovensku (Nitra I-�Cerm�a�n against the background ofthe Gravettian settlement structure in Slovakia). Slovensk�a archeol�ogia 59,1e86.

Kaminsk�a, L'., Kozłowski, J.K., Sobczyk, K., Svoboda, J.A., Michalík, T., 2008. �Struktúraosídlenia mikroregi�onu Tren�cína v strednom a mladom paleolite (Settlementstructure of the Tren�cín microregion in the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic).Slovensk�a archeol�ogia 56, 179e238.

Kaminsk�a, L'., Kozłowski, J.K., �Skrdla, P., 2011. New approach to the Szeletian e

chronology and cultural variability. Eurasian Prehistory 8, 29e49.Kot, M.A., 2013. The earliest Palaeolithic bifacial leafpoints in Central and Southern

Europe: techno-functional approach. Quaternary International 326e327,381e397.

Kozłowski, J.K. (Ed.), 1998. Complex of Upper Palaeolithic Sites Near Moravany,Western Slovakia. Moravany-lopata II (Excavations 1993e1996), vol. 2. Jagel-lonian University, Institute of Archaeology, Krak�ow.

Kozłowski, J.K., 2008. The shouldered point horizon and the impact of the LGM onhuman settlement distribution in Europe. In: Svoboda, J.A. (Ed.), Pet�rkovice: onShouldered Points and Female Figurines. The Dolní V�estonice Studies, vol. 15.Institute of Archaeology at Brno, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic,Brno, pp. 181e192.

Kozłowski, J.K., 2013. Raw materials procurement in the Late Gravettian of theCarpathian Basin. In: Mester, Z. (Ed.), The Lithic Raw Material Sources andInterregional Human Contacts in the Northern Carpathian Regions. PolishAcademy of Arts and Sciences, Krak�owebudapests, pp. 63e85.

Kozłowski, J.K., 2015. The origin of the gravettian. Quaternary International359e360, 3e18.

Kozłowski, J.K., Sobczyk, K., 1987. The upper Paleolithic site Krak�oweSpadzistastreet C2. Excavations 1980. Prace Archeologiczne 42, 7e68.

Lengyel, G., 2008e2009. Radiocarbon dates of the “Gravettian Entity” in Hungary.Praehistoria 9e10, 241e263.

Please cite this article in press as: Lengyel, G., et al., The Late Gravettian ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.09.014

Lengyel, G., 2014. Distant connection changes from the Early Gravettian to theEpigravettian in Hungary. In: Otte, M., Le Brun-Ricalens, F. (Eds.), Modes decontacts et de d�eplacements au Pal�eolithique eurasiatique: Modes of contactand mobility during the Eurasian Palaeolithic. E.R.A.U.L. 140 e Arh�eoLogiques 5.Universit�e de Li�ege, Li�egeeLuxembourg, pp. 331e347.

Lengyel, G., 2015. Lithic raw material procurement at BodrogkeresztúreHenyeGravettian site, northeast Hungary. Quaternary International 359e360, 292e303.

Lengyel, G., Mester, Z., 2008. A new look at the radiocarbon chronology of theSzeletian in Hungary. Eurasian Prehistory 5 (2), 73e83.

Lengyel, G., Szoly�ak, P., Pacher, M., 2008e2009. Szeleta Cave earliest occupationreconsidered. Praehistoria 9e10, 9e20.

Mark�o, A., Bir�o, K., Kasztovszky, Z., 2003. Szeletian felsitic porphyry: nonedestructive analysis of a classical palaeolithic raw material. Acta ArchaeologicaAcademaiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 54, 297e314.

Marks, L., 2012. Timing of the Late Vistulian (Weichselian) glacial phases in Poland.Quaternary Science Reviews 44, 81e88.

McBrearty, S., Bishop, L., Plummer, T., Dewar, R., Conard, N., 1998. Tools underfoot:human trampling as an agent of lithic artifact edge modification. AmericanAntiquity 63, 108e129.

Mester, Z., 1994. A Bükki Moust�erien Revízi�oja. Magyar Tudom�anyos Akad�emia,Budapest. Unpublished CSc thesis.

Mester, Z., 2002. Excavations at Szeleta Cave before 1999: methodology and over-view. Praehistoria 3, 57e78.

Mester, Z., 2007. Pour continuer les investigations sur les gisements classiques enHongrie : les grottes Szeleta et d'Ist�all�osk}o. In: �Evin, J. (Ed.), XXVIe Congr�esPr�ehistorique de France, Congr�es du Centenaire de la Soci�et�e pr�ehistoriquefrançaise, Avignon, 21-25 septembre 2004 : Un si�ecle de construction du dis-cours scientifique en Pr�ehistoire, «Des Id�ees d’hier...», Vol. II. Soci�et�epr�ehistorique française, Paris, pp. 239e248.

Mester, Z., 2010. Technological analysis of Szeletian bifacial points from Szeleta Cave(Hungary). Human Evolution 25, 107e123.

Mester, Z., 2014. Technologie des pi�eces foliac�ees bifaces du Pal�eolithique moyen etsup�erieur de la Hongrie. In: Bir�o, K.T., Mark�o, A., Bajnok, K.P. (Eds.), AeolianScripts. New Ideas on the Lithic World. Studies in Honour of Viola T. Dobosi.Inventaria Praehistorica Hungariae 13. Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum, Budapest,pp. 41e62.

Mester, Z., Szoly�ak, P., Lengyel, G., Ringer, �A., 2013. SzeleStra: új r�etegtani kutat�asoka Szeletien kultúra n�evad�o lel}ohely�en. Litikum 1, 60e65.

M�esz�aros, G., V�ertes, L., 1955. A paint mine from the early Upper Palaeolithic agenear Lovas (Hungary, County Veszpr�em). Acta Archaeologica Academiae Sci-entiarum Hungaricae 5, 1e32.

Moreau, L., 2009. Geißenkl€osterle. Das Gravettien der Schw€abischen Alb im euro-p€aischen Kontext. Tübinger Monographien zur Urgeschichte, Kerns Verlag,Tübingen.

Moreau, L., 2012. Le Gravettien ancien d’Europe centrale revisit�e :mise au point etperspectives. L'Anthropologie 116, 609e638.

Mottl, M., 1938. Faunen, Flora und Kultur des ungarischen Solutr�een. Quart€ar 1,36e54.

Nemergut, A., Cheben, M., Gregor, M., 2012. Lithic raw material use at the Palae-olithic site of Moravany nad V�ahomeDlh�a. Anthropologie 50, 379e390.

Nerudov�a, Z., Neruda, P., 2004. Les remontages des gisements szeletiens en Moravie(R�epublique Tch�eque). Anthropologie 42, 279e309.

Nov�ak, M., 2008. Flint and radiolarite assemblages: technology and typology. In:Svoboda, J.A. (Ed.), Pet�rkovice: on Shouldered Points and Female Figurines.The Dolní V�estonice Studies 15. Institute of Archaeology at Brno. Academy ofSciences of the Czech Republic, Brno, pp. 70e142.

Oliva, M., 2007. Gravettien Na Morav�e. Dissertationes Archaeologicae Brunenses/Pragensesque 1. Masarykova univerzita, Filozofick�a fakulta, BrnoePraha.

Oliva, M., 2009. �Stípan�a industrie sektoru G (Chipped Industry in Sector G. In:Oliva, M. (Ed.), Sídli�st�e mamutího lidu u Milovic pod P�alavou. Milovice: Site ofthe Mammoth People below the Pavlov Hills, Studies in Anthropology, Palae-oethnology, Paleontology and Quaternary Geology, Vol. 27. Moravsk�e Zemsk�eMuzeum, Brno, pp. 161e216.

P�entek, A., Zandler, K., 2013. Nyílt színi Szeletien telep Sz�ecs�enkeeKis-Ferenc-hegyen. Litikum 1, 36e49.

Pesesse, D., 2008. Le statut de la fl�echette au sein des premi�eres industries grave-ttiennes. Pal�eo 20, 45e58.

Pesesse, D., 2011. R�eflexion sur les crit�eres d’attribution au Gravettien ancien. In:Goutas, N., Klaric, L., Pesesse, D., Guillermin, P. (Eds.), A la recherche desidentit�es gravettiennes. M�emoire de la Soci�et�e Pr�ehistorique Française, Paris,pp. 147e159.

Połtowicz-Bobak, M., Bobak, D., Badura, J., Wacnik, A., Cywa, K., 2013. Nouvellesdonn�ees sur le Sz�el�etien en Pologne. In: Bodu, P., Chehmana, L., Klaric, L.,Mevel, L., Soriano, S., Teyssandier, N. (Eds.), Le Pal�eolithique sup�erieur ancien del’Europe du Nord-Ouest. R�eflexions et synth�eses �a partir d’un projet collectif derecherche sur le centre et le sud du Bassin parisien. Actes du colloque de Sens(15e18 avril 2009). Bulletin de la Soci�et�e Pr�ehistorique Francaise, Memoire 56,Paris, pp. 485e496.

P�richystal, A., 2013. Lithic Raw Materials in Prehistoric Times of Eastern CentralEurope. Masaryk University, Brno.

Pro�sek, F., 1953. Szeletien na Slovensku (Le Szeletien en Slovaquie). Slovensk�aarcheol�ogia 1, 133e194.

Renard, C., 2011. Continuity or discontinuity in the Late Glacial Maximum ofsouthewestern Europe: the formation of the Solutrean in France. WorldArchaeology 43, 726e743.

nd Szeleta Cave, northeast Hungary, Quaternary International (2015),

G. Lengyel et al. / Quaternary International xxx (2015) 1e1010

Ringer, �A., 1983. B�abonyien: Eine Mittelpal€aolitithische Blattwerkzeugindrustrie inNordost-ungarn. E€otv€os Lor�and Tudom�anyegyetem, Budapest.

Ringer, �A., 1989. L’origine du Sz�el�etien de Bükk en Hongrie et son �evolution vers lePal�eolithique sup�erieur. Anthropologie 27, 223e229.

Ringer, �A., 2008e2009. Nouvelles donn�ees sur le Sz�el�etien de Bükk. Praehistoria9e10, 21e34.

Ringer, �A., Holl�o, Z., 2001. Saj�oszentp�eter Margit-kapu-d}ul}o, egy fels}o-paleolitlel}ohely a Saj�o v€olgy�eben (Saj�oszentp�eter Margit-kapu-d}ul}o, un site dupal�eolithique sup�erieur dans la vall�ee de Saj�o). A Herman Ott�o Múzeum�Evk€onyve 40, 63e71.

Ringer, �A., Mester, Z., 2000. R�esultats de la r�evision de la grotte Szeleta entreprise en1999 et 2000. Anthropologie 38, 261e270.

Ringer, �A., Szoly�ak, P., 2004. A Szeleta-barlang t}uzhelyeinek �es paleolit leleteinektopogr�afiai �es sztratigr�afiai eloszl�asa. Adal�ekok a leletegyüttesújra�ert�ekel�es�ehez (The topographic and stratigraphic distribution of thePalaeolithic hearths and finds in the Szeleta Cave. Contribution to re-interpretation of the assemblage). Herman Ott�o Múzeum �Evk€onyve 43, 13e32.

Ringer, �A., Kordos, L., Krolopp, E., 1995. Le complexe B�abonyieneSz�el�etien enHongrie du norde est dans son cadre chronologique et environnemental. Pal�eoe Suppl�ement No 1, 27e30.

Sa�ad, A., 1929. A Bükk-hegys�egben v�egzett újabb kutat�asok eredm�enyei. Archae-ologiai �Ertesít}o 43, 238e247.

Sa�ad, A., Nemesk�eri, J., 1955. A Szeletabarlang 1947. �evi kutat�asainak eredm�enyei.Folia Archaeologica 7, 15e21.

Sim�an, K., 1985. Paleolit leletek Saj�oszentp�eteren. Herman Ott�o Múzeum �Evk€onyve22e23, 9e20.

Sim�an, K., 1990. Considerations on the “Szeletian unity”. In: Kozłowski, J.K. (Ed.),Feuilles de pierre. Les industries �a pointes foliac�ees du Pal�eolithique sup�erieureurop�een. ERAUL 42, Universit�e de Li�ege, Li�ege, pp. 189e198.

Sim�an, K., 1995. La grotte Szeleta et le Sz�el�etien. Pal�eo e Suppl�ement No 1 37e43.Simonet, A., 2011. La pointe des Vachons Nouvelles approches d’un fossile directeur

controvers�e du Gravettien �a partir des exemplaires du niveau IV de la grotted’Isturitz (Pyr�en�eesAtlantiques, France) et des niveaux 4 des abris 1 et 2 desVachons (Charente, France). Pal�eo 22, 271e298.

Sobczyk, K., 1995. Osadnictwo Wschodniograweckie W Dolinie Wisły Pod Krako-wem. Rozprawy habilitacyjne, Universitet Jagiello�nski, Krak�ow.

Sobczyk, K., 1996. Krak�oweSpadzista unit D: excavations 1986e1988. Folia Qua-ternaria 67, 75e127.

Soriano, S., 1998. Les microgravettes du P�erigordien de Rabier �a Lanquais (Dor-dogne): analyse technologique fonctionnelle. Gallia pr�ehistoire 40, 75e94.

Strauss, L.G., 2015. Recent developments in the study of the Upper Paleolithic ofVascoeCantabrian Spain. Quaternary International 364, 255e271.

Svoboda, J., 2008. Conclusions. In: Svoboda, J.A. (Ed.), Pet�rkovice: on ShoulderedPoints and Female Figurines. The Dolní V�estonice Studies 15. Institute of

Please cite this article in press as: Lengyel, G., et al., The Late Gravettian ahttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.09.014

Archaeology at Brno. Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Brno,pp. 233e236.

Svoboda, J., Sim�an, K., 1989. The MiddleeUpper Paleolithic transition in South-eastern Central europe (Czechoslovakia and Hungary). Journal of World Pre-history 3, 283e322.

Szoly�ak, P., 2011. Els}odleges nyersanyag-feldolgoz�as nyomai a szeletai kvarcporfírlel}ohely�en (Bükkszentl�aszl�o). A Herman Ott�o Múzeum �Evk€onyve 50, 47e66.

T�oth, Z.H., 2011. Újabb adal�ek a szeletai üveges kvarcporfír elofordul�ashoz:Bükkszentl�aszl�o, Hideg-víz. Gesta 10, 147e149.

Valoch, K., 1996. Le Pal�eolithique en Tch�equie et en Slovaquie. Pr�ehistoire d’Europe3. J�erome Millon, Grenoble.

Verpoorte, A., 2002. Radiocarbon dating the Upper Palaeolithic of Slovakia: results,problems and prospects. Arch€aologisches Korespondezblatt 32 (3), 311e325.

Verpoorte, A., 2004. Eastern Central europe during the Pleniglacial. Antiquity 78,257e266.

V�ertes, L., T�oth, L., 1963. Der Gebrauch des glasigen Quarzporphyrs imPal€aolithikum des Bükk-Gebirges. Acta Archaeologica Academiae ScientiarumHungaricae 15, 3e10.

V�ertes, L., 1965. Az }osk}okor �es az �atmeneti k}okor eml�ekei Magyarorsz�agon. AMagyar R�eg�eszet K�ezik€onyve 1. Akad�emiai Kiad�o, Budapest.

V�ertes, L., 1968. SzeletaeSymposium in Ungarn, 4e11 September 1966. Quart€ar 19,381e390.

Vla�ciky, M., Michalík, T., Nývltov�a Fi�s�akov�a, M., Nývlt, D., Moravcov�a, M., Kr�alík, M.,Kovanda, J., P�ekov�a, K., P�richystal, A., Dohnalov�a, A., 2013. Gravettian occupationof the Beckov Gate in Western Slovakia as viewed from the interdisciplinaryresearch of the Tren�cianske BohuslaviceePod Tureckom site. Quaternary In-ternational 294, 41e60.

V€or€os, I., 2000. Macro-mammal remains on Hungarian Upper Pleistocene sites. In:Dobosi, V.T. (Ed.), BodrogkeresztúreHenye (NE Hungary), Upper PalaeolithicSite. Hungarian National Museum, Budapest, pp. 186e212.

Wilczy�nski, J., 2007. The Gravettian and Epigravettian lithic assemblages fromKrak�oweSpadzista BþB1: dynamic approach to the technology. Folia Qua-ternaria 77, 37e96.

Wilczy�nski, J., Wojtal, P., Dobieraj, D., Sobczyk, K., 2015a. Krak�ow Spadzistatrench C2: new research and interpretations of Gravettian settlement. Qua-ternary International 359e360, 96e113.

Wilczy�nski, J., Wojtal, P., Łanczont, M., Mroczek, P., Sobieraj, D., Fedorowicz, S.,2015b. Loess, flints and bones: multidisciplinary research at Jaksice IIGravettian site (southern Poland). Quaternary International 359e360,114e130.

�Za�ar, O., 2007. Gravettienska Stanice V Tren�cianskich Bohuslavicach. Filozofick�aFakulta, Univerzita Kon�stantína Filozofa v Nitre, Nitra. Unpublished MAthesis.

nd Szeleta Cave, northeast Hungary, Quaternary International (2015),