ELECTROMAGNETIC TRANSMISSION THROUGH FRACTAL APERTURES IN INFINITE CONDUCTING SCREEN

The influence of heightened body-awareness on walking through apertures

Transcript of The influence of heightened body-awareness on walking through apertures

APPLIED COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGYAppl. Cognit. Psychol. (2009)Published online in Wiley InterScience

(www.interscience.wiley.com) DOI: 10.1002/acp.1568*4*C

C

The Influence of Heightened Body-awareness on WalkingThrough Apertures

STACY LOPRESTI-GOODMAN1*, RACHEL W. KALLEN2,MICHAEL J. RICHARDSON2, KERRY L. MARSH1 and

LUCY JOHNSTON3**1University of Connecticut, USA

2Colby College, USA3University of Canterbury, New Zealand

SUMMARY

The reported study measured the ratio between aperture-width and hip-width that marked the criticaltransition from frontal walking to body rotation for male and female participants. Half of theparticipants of each sex wore form-fitting lycra clothes and half loose-fitting jogging suits.Participants wearing the form-fitting clothing reported heightened body awareness relative to thosewearing the loose-fitting clothing. For male participants this difference was reflected in a smalleraperture-to-hip ratio in the form-fitting than loose-fitting clothing condition. That is, males walkedfrontally through smaller apertures when wearing form-fitting than when wearing loose-fittingclothing. For females there was no difference in walking action as a function of clothing style. Resultsare discussed in terms of the perception of action opportunities in the environment, the influence ofbody awareness on such perception and sex differences. Copyright# 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Navigating successfully and safely through the environment is a complex skill that involves

the detection of action and interaction possibilities by the perceiver. Gibson (1979)

introduced the term ‘affordances’ to describe the complementarity of the organism and its

environment, as well as that of perception and action (Michaels & Carello, 1981;

Stoffregen, 2003; Turvey, Shaw, Reed, & Mace, 1981). Affordances are the sorts of

behaviours permitted (and denied) to perceivers by objects, people and places in the

environment. An affordance is the action or interaction opportunities available to the

individual perceiver. For example, an orange may afford eating, another person may afford

dancing with and a gap in traffic may afford crossing the road. Importantly affordances are

neither properties of the individual, nor of the environment but are relational properties of

the two. An orange is not eatable per se but rather it affords eating to those individuals who

have the capabilities (effectivities; Michaels, 2003; Reed, 1996; Shaw & Turvey, 1981;

Turvey & Shaw, 1979) to eat it, that is thosewho have the ability to grasp the orange, to peel

and to bite it and to digest it. Accordingly, for some individuals the orange may not afford

Correspondence to: Stacy Lopresti-Goodman, CESPA, Department of Psychology, University of Connecticut,06 Babbidge Road, Unit 1020, Storrs, CT 06269-1020. E-mail: [email protected]*Correspondence to: Lucy Johnston, Department of Psychology, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800,hristchurch, New Zealand. E-mail: [email protected]

opyright # 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

S. Lopresti-Goodman et al.

eating. Similarly, a gap in traffic may afford road crossing to somebody with a fast walking

speed but not somebody with a slow walking speed (Simpson, Richardson, & Johnston,

2003). Some effectivities are fixed. So, for example, a blind individual is never able to

detect affordances specified in the optic array. Other effectivities may be acquired, such as

grasping skills. An orange may not, then, afford eating for the young child as they cannot

grasp the fruit in order to peel and bite it, but as their motor skills develop the orange will

come to afford eating. Understanding how differential sensitivity to the organism–

environment fit influences the width of a gap passed through, brought about by wearing

different clothing, is the aim of the current experiment.

The concept of affordances focused researchers’ attention to the question of how

individuals perceive environmental surfaces and objects in relation to their own bodily

dimensions or capabilities (Gibson, 1979; Shaw & Turvey, 1981; Turvey & Shaw, 1979).

The detection of affordances involves more than the mere perception of properties of the

environment; rather the environment is perceived in terms of what actions are afforded to

the particular perceiver in question. That is, the relational properties of the self and the

environment must be perceived.

Although, the perception of affordances is relative to the individual perceiver, such

detection is not subjective. Affordances are perceived by detecting lawfully structured

information that invariantly specifies capabilities of an individual in relation to objective

features of an object, person or event (Gibson, 1979; Michaels & Carello, 1981). Such lawful

regularities of an animal–environment system govern and can predict action possibilities for

all individuals. For example, steep stairs may afford stepping on for some people (e.g. those

with long legs) and not for others (e.g. those with short legs). The basis on which these actions

are determined is, however, invariant across individuals. Regardless of leg length, the size of

stair which is step-on-able for a given individual is a constant ratio of leg-length-to-riser-

height (Warren, 1984). Dimensionless ratios such as this one are referred to as body-scaled

ratios, or pi numbers, with E/A, (E is the measured environmental property and A is the

measured action-relevant property of an agent) representing a more general formalism. These

body-scaled invariant ratios identify affordance boundaries, points at which the limits of an

action are reached and a transition to a new actionmust be made (e.g. the point at which a stair

is no longer step-on-able but may be climb-on-able). Pi-numbers also allow for meaningful

comparisons across individuals who may, for example, be of different size, or ability.

Previous research has identified body-scaled invariants for the affordance of sit-on-

ability of surfaces at different heights (e.g. Mark, 1987), the reach- and grasp-ability of

objects at different distances (e.g. Carello, Grosofsky, Reichel, & Solomon, 1989), the

walk-up-ability of slopes of different angles (Kinsella Shaw, Shaw, & Turvey, 1992), and,

of particular relevance to the present research, the walk-through-ability of doorway like

apertures of different widths (Warren & Whang, 1987).

Warren and Whang (1987) investigated the affordance of passability through doorway-

like apertures of differing widths by ‘large’ and ‘small’ males. As expected, there was a

difference in the absolute width of the apertures that walkers of different sizes could walk

forward through without body rotation. However, a transformation of the data to a pi-

number (aperture width/shoulder width) resulted in an invariant ratio for large and small

participants that specified the critical aperture width at which frontal walking was no longer

afforded. A pi number of approximately 1.30 specified the aperturewidth at which shoulder

rotation was seen, regardless of walker size.1 Detecting the affordance of passability

1A ratio> 1 allows for a ‘margin of safety’ given the natural body sway that occurs during walking.

Copyright # 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/acp

Body-awareness and passability

requires awareness of the size, shape and movement of one’s body relative to the available

gap. The present research extended that of Warren and Whang, through investigation of

whether heightened body awareness influenced the pi-number of aperture passability for

both male and female walkers.

Before considering the predicted influence of heightened body awareness on perception,

we first consider the impact of temporary changes to a perceiver’s effectivities. Changes to

effectivities may arise gradually due to maturation (e.g. increased ability to grasp) and

to aging (e.g. decreased walking speed). Accordingly the relationship between the

individual and the environment is malleable; as one ages one may detect action

opportunities not available when younger but also some action opportunities available in

youth are no long available in older age. Individual perceivers adapt well to changes in their

effectivities in such circumstances. Similarly, temporary changes to effectivities frequently

occur and are adapted to quickly by perceivers. For example, in a task which involved

perceivers in an immersive virtual environment selecting gaps in a flow of traffic through

which to ‘safely cross’ the virtual road, Murray (2003) showed that attaching a leg brace to

fit walkers resulted in rapid adaptation and selection of larger gaps in traffic through which

to cross than before the brace was attached. Removal of the brace similarly resulted in a

rapid return to the selection of smaller gaps in traffic through which to cross the road. In a

seminal demonstration of the flexibility of effectivities and the detection of affordance,

Mark (1987; see also Mark, Balliett, Craver, Douglas, & Fox, 1990; Mark & Vogele, 1987)

showed that attaching wooden blocks to individual’s shoes resulted in their regauging their

perceptual boundaries, with only a little experience of moving with the blocks attached

needed in order to do so. Importantly, Mark considered two tasks, judging the sit-on-ability

of chairs of different heights and the step-on-ability of stairs of different riser heights.

Attaching blocks to the shoes changed the perceiver’s capabilities for the former but not the

latter task (which relies on upper leg length only), changes that were reflected in the

behaviour of the experimental participants which was consistent with these new

capabilities. Researchers have not only examined how foot attachments (blocks or very

high shoes: Japanese getas) lead individuals to retune their perceptions of maximum

seating height (Mark et al., 1990) and of their ability to step over a bar (Hirose & Nishio,

2001), but researchers also explored a variety of other ways effectivities might change.

Thus, the geometry and dynamics of individual’s action system have been changed using

hand-held tools (rods for pushing over an object, hammers, pokers, claw-like reach

extenders, hooks for pulling an object towards one, tennis rackets and bats) or wheelchairs

(Bongers, Michaels, & Smitsman, 2004; Bongers, Smitsman, & Michaels, 2003b; Carello,

Thout, Anderson, & Turvey, 1999; Richardson, Marsh, & Baron, 2007; Shaw, Flascher, &

Kadar, 1995; Steenbergen, van der Kamp, Smitsman, & Carson, 1997; van Leeuwen,

Smitsman, & van Leeuwen, 1994; Wagman & Carello, 2001, 2003).

The perceptual processes involved when a tool becomes a part of an individual’s action

system reflect similar processes as to when one acts without a tool. Perceived ability to pass

between barriers in a wheelchair is determined by a comparable pi number as when

perceiving whether one can pass through on foot (Shaw et al., 1995), and perceptions of

when one would move planks of wood with a tool that extended one’s grip is determined by

a comparable pi number as for affordance boundaries without tools (Richardson et al.,

2007). Thus, even when physical objects extend an individual’s effectivities, the key

determinant of perceived affordance boundaries is still the organism–environment relation

or the fit between quantifiable aspects of the person plus tool system and the environment.

Moreover, the way an individual produces an action is tightly linked with the constraints of

Copyright # 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/acp

S. Lopresti-Goodman et al.

the object one is using. For instance, the types and rigidity of grips that children displayed

when using spoon-like tools to transport rice between buckets were determined by

variations in the orientation between the stem and bowl of the spoon (Steenbergen et al.,

1997). The way adults grasped an object varied depending on whether a tool was for

imparting force (e.g. hammer) or primarily for precision movement (e.g. a fire poker,

Wagman & Carello, 2001, 2003). Adults and children also show evidence of anticipating

tool-induced change in effectivities, varying, for instance, the distance from a target when

stopping to displace it with a rod that varies in length or mass characteristics (Bongers

et al., 2003, 2004a,b). One of the most critical lessons of the literature on how physical

conditions change effectivities is how important one’s own exploratory activities are for

discovering affordances and for refining one’s effectivities when using the tool (e.g. Mark

et al., 1990). Whether by merely visually exploring by moving one’s head, or changing

one’s posture (Mark et al., 1990) or by using dynamic, haptic information—swinging an

object around without vision (Wagman & Carello, 2001, 2003)—individuals become

increasingly attuned to the information that specifies affordances such as the sweet spot of

an tennis racket or bat (Carello et al., 1999) or whether a surface is too high to sit on (Mark

et al. 1990).

In addition to the impact of changes to physical effectivities on perception, recent

research has shown that perception can also be influenced by social psychological factors,

such as how perceivers regard themselves. Researchers have suggested that changes in

mood, attitudes and social relationships may all influence the perceiver’s perception of the

environment. For example, emotional state has been shown to influence perceptions of

distance (Balketis &Dunning, 2007) and slant (Stefanucci, Proffitt, Clore, & Parekh, 2008)

and self-esteem to influence height perception (Harber & Valree, 2008). In the present

research, we extend this research further by considering the impact of changes in self-

awareness on the detection of action opportunities in the environment. Specifically, we

consider whether an increase in body awareness influences the perception of the pass-

through-ability of apertures.

Investigation of the impact of heightened body awareness on behaviour has emerged

from self-objectification theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997) which has hypothesized

that women have a heightened awareness of their body size and shape as a consequence of

living in a culture saturated with the objectification of women’s bodies (Fredrickson &

Roberts, 1997; McKinley & Hyde, 1996). Of particular relevance to the present research is

the creation of a temporary state of heightened body awareness. Such a state can be brought

about by situational factors, such as receiving comments regarding one’s body or

appearance (Swim, Hyers, Cohen, & Ferguson, 2001) or dressing in form-fitting or

revealing clothing (e.g. Fredrickson, Roberts, Noll, Quinn, & Twenge, 1998; Quinn,

Kallen, Twenge, & Fredrickson, 2006a; Quinn, Kallen, & Cathey, 2006b). For example,

Fredrickson et al. (1998) showed both men and women dressed in clothes that revealed

their body size and shape (a swimsuit) to have heightened body awareness in comparison to

individuals dressed in less revealing clothes (a sweater), as evidenced by more references

to body size and shape and physical appearance terms in the self-descriptive modified

twenty statement test (TST; Kuhn & McPartland, 1954).

Despite similar levels of heightened body awareness, the subsequent impact of such

heightened self-awareness has been shown to be very different for males and females. For

females, heightened body awareness has been associated with greater body shame and

heightened negative self-related emotions, with restrained eating, and with poorer

cognitive functioning. Such negative consequences of heightened body awareness is not

Copyright # 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/acp

Body-awareness and passability

typically seen, however, for male participants (e.g. Fredrickson et al., 1998; Kallen &

Quinn, 2007).2

In the present study, we considered how enhanced body awareness might lead to

differential action in an aperture passability task. Feelings of dissatisfaction with one’s body

size and shape are most frequently centered on the abdomen, hips and thighs (Gupta,

Chaturvedi, Chandarana, & Johnson, 2001) and accordingly we employed a waist/hip

height aperture to focus participants’ attention to these regions of the body. Moreover, we

heightened participants’ attention to their bodies by having them don form-fitting clothing.

Of primary interest was whether this increase in attunement to their body dimensions would

influence the action of participants in the passability task. Previous research employed tasks

for which attention to body size and shape could be considered a distraction, such as a

Stroop task (Quinn et al., 2006a) or math problem-solving task (Fredrickson et al., 1998).

The present task, in contrast, is one in which awareness of body size is an integral part of the

task. Rather than heightened body awareness disrupting performance on the present task,

which couldmanifest in a larger pi-number, heightened attunement to one’s bodymight lead

to enhanced performance, manifesting in a smaller pi-number, representing a greater

awareness of the fit between one’s own body and the environment.

Given the differential impact of enhanced body awareness for males and females as

detailed above, the present study also considered sex differences in passability. Warren and

Whang (1987) only recruited male participants so it is unknown whether there are sex

differences in the pi number for passability. It is noteworthy that, with the exception of one

study (Pepping & Li, 2000), past research on the detection of affordances and body-scaled

ratios has not considered sex differences. Researchers have either only included

participants of one sex (Hirose & Nishio, 2001; Mark, 1987) or where both male and

female participants were tested, the sex of participants was not included as a factor in the

reported data analysis (Mark et al., 1990; Stoffregen, Yang, &Wagman, 2005; Wagman &

Taylor, 2005; Wraga, 1999). Seemingly, researchers in this domain have not considered

perceiver sex to be a factor likely to influence the detection of affordances. Indeed, the one

study that did consider participant sex found no sex differences in the perception of

maximum reachability and no sex differences in the impact of adding blocks to the feet on

these perceptions of reachability (Pepping & Li, 2000). Research on the impact of

heightened body awareness has, however, consistently revealed sex differences, as detailed

above, and hence is important to consider in the present research.

The self-objectification literature might lead to the prediction that if females, as a

consequence of societal pressures, have a chronically heightened sensitivity to body size

relative to males (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; McKinley & Hyde, 1996), they would

already bemore aware of the self-environment fit and hence would have a smaller pi number

on the passability task than males. That is, females would be more aware of the (smallest)

size of aperture through which they could walk frontally. As such females may have little

scope for improvement in their judgments of gap size, and hence not be influenced by

temporally heightened body awareness. On the other hand, it is also possible that societal

pressures on women regarding body size and shape result in increased salience of body size

issues but lead women to have a less accurate awareness of body shape (generally seeing

2Chronically high levels of self-objectification (high trait self-objectification) have also been associated withnegative consequences amongst women, such as negative effect, disruption of attention and cognitive perform-ance, body shame, sexual dysfunction and eating disorders, but not amongst males (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997;Muehlenkamp & Saris-Baglama, 2002). The present research only investigated the impact of a temporary state ofheightened self-objectification, however.

Copyright # 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/acp

S. Lopresti-Goodman et al.

themselves as larger than they actually are). In this case, women might have a chronically

higher pi-number but, like men, would have scope for change on the passability task as a

function of heightened body awareness. Such further heightening of body awareness may

lead either to enhanced awareness of self-environment fit and hence to smaller pi-numbers

for women, or to a greater distortion of beliefs about body size and hence lessened accuracy

in awareness of self-environment fit, leading to larger pi numbers.

METHOD

Participants

Thirty-two male and 31 female3 University of Connecticut undergraduate students

volunteered to participate in partial fulfilment of course requirements. Procedures were

approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board.

Materials

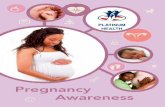

The experimental set-up is shown in Figure 1. A waist-high aperture was formed by two

wooden partitions, each 86.5 cm high4. One partition remained stationary, while a second

moveable partition extended beyond a ceiling-to-floor black felt curtain that divided the

room. Thirteen aperture widths, ranging from 30 to 90 cm in 5 cm increments, were created

by sliding the second partition along floor markers occluded from the participant’s view. At

each end of the room, a white line marked the point fromwhich each trial began. Hanging on

the wall adjacent to each starting line were wall mounted full-length mirrors, which, if

attended to by participants would enhance their self-awareness (Webb, Marsh, Schneider-

man, & Davis, 1989; Wicklund & Duval, 1971).5 A 60 cm wooden dowel (diameter 2.5 cm)

was held by the participant in both hands at chest level throughout the experiment. The focus

of this paper is on the impact of enhanced body self-awareness on action. Given the focus of

body awareness on the abdomen, hips and thighs (Gupta et al., 2001), we wished to ensure

that the impact of the hip area was considered in the research. Having participants hold the

dowel rod at chest height ensured that only hip width influenced whether participants could

walk frontally through the apertures, the possible influence on determining aperture

passability of the normal swinging of the arms that accompanies walking was eliminated.6

All trials were recorded using a 2m high tripod mounted digital camcorder.

3Data from two additional participants were excluded from analyses. One male participant in the form-fittingclothing condition failed to follow instructions and one female in the loose-fitting clothing condition had aphysical disability that affected her gait. It should be noted that no participants choose to withdraw from the studyafter learning about the clothing manipulation involved.4Although the height of the partition was the same for all participants, the height was such that for all participantsthe top of the partition was at or above hip height. Accordingly, for all participants hip width would haveinfluenced whether participants could walk frontally through the aperture.5Consistent with most research using manipulations of self-focused attention, we did not have a check on whetherparticipants looked in the mirrors or not, nor do we know whether men and women differed in their mirror-gazing.Past research examiningmale and female mirror-gazing in a naturalistic setting found only physical attractiveness,and not sex, predicted gazing (Lipson, Przybyla, & Byrne, 1983). Accordingly, although there may have beenindividual differences in the extent to which participants attended to the mirror, it is unlikely that there weresystematic sex differences.6The use of the dowel rod in current task may have influenced the natural gait of participants and drawn someattention to the shoulder area. Given the focus of the present research was on walking through a hip height apertureit is unlikely that such enhanced awareness of the shoulders would have influenced the present findings. Futureresearch might, however, consider alternative, more natural, means by which the impact of swinging arms beeliminated (e.g. walking with the arms crossed over the chest).

Copyright # 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/acp

Figure 1. Experimental set-up

Body-awareness and passability

Procedure

Participants were tested individually by a female experimenter.7 Half of the male and half

of the female participants were randomly assigned to the form-fitting clothing (heightened

body awareness) and half to the loose-fitting clothing condition. The participant was asked

to change into the relevant clothes which it was said was to ensure uniformity in attire

across participants. Changing occurred in a private dressing room containing a large full-

length mirror. The participant selected the appropriate clothing size from a box in the

changing room. In the form-fitting condition the participant was told that the lycra clothes

7Given that only a female experimenter was employed in the present research it is possible that the effects reportedare not specific to males but are due to being in the presence of an opposite sex experimenter. We believe that this isunlikely, however, as the previous studies investigating self objectification reported in the text (Fredrickson et al.,1998; Kallen & Quinn, 2007; Quinn et al., 2006a, 2006b) all employed only a female experimenter. This pastresearch showed higher body self-awareness for males and females in the objectification studies (as in ourresearch) but showed no impact on subsequent tasks for males (in contrast to our study). In addition, theexperimenter in our study was not visible to the participants during the walking part of the study (she waspositioned behind the curtain adjusting the aperture width between trials) so minimizing the likelihood of theexperimenter’s sex influencing the participants’ behaviour on this task.

Copyright # 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/acp

S. Lopresti-Goodman et al.

(pants and top) should be tightly figure hugging and in the loose-fitting condition that the

jogging-suit should be a loose fit. After changing, the participant completed a demographic

questionnaire and the TST (Kuhn & McPartland, 1954).

Each of the 13 aperture widths occurred four times, giving a total of 54 trials, presented

in a unique random order for each participant. Each trial consisted of having the participant

walk from one end of the room to the other, through the aperture, while holding the wooden

dowel at chest level. To ensure that he or she could not see whether the aperture width

increased or decreased between trials, the participant remained facing the opposite wall

until the experimenter indicated that the next trial was to begin. Although the focus of the

present research was on action, participants also completed a set of perception trials in

which they stood at one end of the room and judged whether they would be able to walk

through each aperture width without hip rotation. Each aperture width was again presented

four times, in a unique random order for each participant, and participants closed their eyes

between trials while the experimenter adjusted the aperture width. After completion of the

trials, the participant’s height, hip width and weight were recorded.

RESULTS

Self-objectification manipulation check

The frequency of body size and shape and physical appearance terms (e.g. tall, thin) in

the TSTwas coded by two independent coders, yielding an inter-rater reliability of 99%.

A 2 (sex: Male/female)� 2 (clothing: Form-fitting/loose-fitting) ANOVA revealed a

marginally significant main effect of clothing only, F(1, 59)¼ 3.76, p¼ .057, h2p ¼ .06.

More body related statements were made by participants in the form-fitting than

loose-fitting clothing condition (Ms¼ 2.38 vs. 1.60). These findings are consistent

with previous use of the TST as a measure of self-objectification (e.g. Fredrickson et al.,

1998), where the wearing of revealing clothing leads to an increased focus on

body size and shape in both men (Ms¼ 2.25 vs. 1.25) and women (Ms¼ 2.50

vs. 1.80).

A further coding of the valence of the body size and shape and physical appearance

items was completed by two independent coders. Each of the items was coded according

to whether it was a positive, negative or neutral statement. Inter-rater agreement was

94%. A 2 (sex: Male/female)� 2 (clothing: Form-fitting/loose-fitting)� 3 (valence:

Positive/negative/neutral) ANOVAwith repeated measures on the third factor, revealed a

main effect of valence, F(2, 88)¼ 41.00, p< .001, h2p ¼ .48, that was qualified by a

significant valence by clothing interaction, F(2, 88)¼ 5.91, p¼ .004, h2p ¼ .12. Post hoc

tests (Tukey, p< .05) showed there to be more neutral than either positive or negative

statements made when wearing the form-fitting lycra (Ms¼ .83 vs. .10 and .07) and more

neutral than positive statements when wearing the loose fitting jogging suit (Ms¼ .57 vs.

.12). Comparisons between participants wearing the form-fitting and loose-fitting clothes

revealed no differences in the proportion of either positive (Ms¼ .10 vs. .31) or negative

statements (Ms¼ .07 vs. .12). This analysis reveals that the majority of the body-relevant

statements made on the TST were neutral in tone. Importantly also there were no main

effects or interactions with sex of participant indicating that males and females did not

differ in the affective content of the enhanced body awareness.

Copyright # 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/acp

Figure 2. Mean Pi numbers (aperture width/hip width) as a function of sex of participant andclothing type condition

Body-awareness and passability

Passability through apertures

Each trial was coded from the video-tapes as involving hip rotation or not by two

independent coders. Rotation was determined to have occurred if the frontal plane of the

participants’ body (i.e. hips and legs) visibly deviated from the coronal plane: That is, they

were no longer parallel to the aperture. Inter-rater reliability was 96%, with discrepancies

subsequently resolved by discussion. Participants walked through each aperture four times

in a random presentation order. For some aperture widths, then, participants walked

frontally on some but not all of the four trials. In order to identify the critical aperture width

of passability, at which participants changed from frontal to rotated walking, two apertures

were identified for each participant—the smallest aperture through which the participant

always walked frontally (i.e. did not rotate the hips for any of the four presentations), and

the largest aperture through which the participant always rotated his/her hips (i.e. rotated

the hips for each of the four presentations). To calculate a critical width of ‘passability’ the

mean of these two apertures was computed (Richardson et al., 2007; van der Kamp,

Savelsbergh, & Davis, 1998). A pi-number was then calculated for each participant by

dividing this mean passability width by the individual’s hip width.

A 2 (sex:Male/female)� 2 (clothing: Form-fitting/loose-fitting) ANCOVA, with BMI as

the covariate,8 was computed on the pi numbers. This yielded no significant effect of the

covariate, but did reveal a marginally significant interaction effect between sex and

clothing, F(1, 58)¼ 3.73, p¼ .058, h2p ¼ .06, as shown in Figure 2.

Simple main effects analysis showed a significant effect of clothing type for male

participants, F (1, 58)¼ 4.51, p< .04 (Ms¼ 1.23 vs. 1.15 for the loose-fitting and form-

fitting conditions, respectively) but no effect for female participants (Ms¼ 1.14 vs. 1.17;

8Previous research has shown a positive correlation between the amplitude of body sway and body mass index(BMI) for healthy young adults (Angyan, Teczely, & Angyan, 2007). Since the amount of body sway duringlocomotion may influence the aperture width through which individuals pass without body rotation, BMI wasincluded as a covariate for the analysis of pi numbers.

Copyright # 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/acp

S. Lopresti-Goodman et al.

p¼ .54). There was a significant effect of sex of participant in the loose-fitting clothing

condition, F (1, 58)¼ 4.63, p< .04 (Ms¼ 1.23 vs. 1.14 for male and female participants,

respectively) but no sex difference in the form-fitting condition (Ms¼ 1.15 vs. 1.17;

p¼ .64).

Perception of aperture width

In order to identify the critical aperture width of perceived passability, two apertures were

identified for each participant—the smallest aperture through which the participant always

said he/she could walk frontally without rotating the hips, and the largest aperture through

which the participant always said he/she would rotated the hips. To calculate a critical

width of ‘perceived passability’ the mean of these two apertures was computed. A

pi-number was then calculated for each participant by dividing this mean perceived

passability width by the individual’s hip width.

A 2 (sex: Male/female)� 2 (clothing: Form-fitting/loose-fitting) ANCOVA, with BMI as

the covariate, was computed on the pi numbers. This yielded only a significant effect of sex,

F(1, 58)¼ 5.69, p¼ .02, h2p ¼ .09, with females having a lower mean pi-number than males

(M¼ 1.06 vs. 1.16).

DISCUSSION

The present experiment extended research on affordances and the identification of invariant

body-scaled ratios that mark the boundary between two action modes—frontal walking

and body rotation. Consistent with Warren andWhang’s (1987) finding that pi-numbers for

passability through door like apertures was independent of participant height, we showed

low variability in pi numbers across participants, indicating that pi-numbers for passability

through hip-height apertures were independent of participant height and weight. Such

findings are consistent with the proposition that body-scaled invariants do identify

affordance boundaries across a number of domains. In addition, in the present research, we

investigated whether pi numbers varied as a function of differential attunement of

individuals to their body size and shape and self-environment fit as a consequence of the

clothing being worn, and as a function of the sex of participants.

As predicted, dressing in form-fitting clothing created a state of heightened body

awareness for both male and female participants, relative to participants wearing loose-

fitting clothing, as revealed by the results of the TST. Of interest was whether this

heightened body awareness had consequences for the action of walking through the waist-

high apertures. It was predicted that greater body awareness would lead to greater

attunement to body-scaled action possibilities, which would be reflected in greater self-

environment awareness, as reflected by a lower pi-number. This effect was seen in the

present research, but only for males. Males wearing the form-fitting clothes had lower pi-

numbers than males wearing the loose-fitting clothes, reflective of greater attunement to

self-environment fit when wearing the lycra outfit. Somewhat surprisingly, there was no

effect of clothing type for female participants, despite evidence from the TST measure of

heightened body-awareness in the form-fitting clothing condition.

Previous research on the impact of heightened body awareness has reported

consequences on behaviour only for female participants (e.g. Fredrickson et al., 1998).

Further, the effects reported have been negative (e.g. Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997;

Copyright # 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/acp

Body-awareness and passability

Fredrickson et al., 1998; Kallen &Quinn, 2007; Muehlenkamp& Saris-Baglama, 2002). In

the present research, the consequences of heightened body-awareness were actions that

reflected greater attunement to the self-environment fit, that is, greater accuracy in judging

which apertures afforded walking through frontally. The consequences of enhanced body

awareness may differ as a function of the nature of the task being completed.

It is important also to note what was not found. Wearing form-fitting lycra did not lead to

more distorted or negative perceptions of the body–environment fit for women (i.e. higher

pi numbers, or perceptions that they were too big to fit through an aperture). The different

consequences for women of heightened body-awareness in different paradigms illustrates

that the context in which such heightened body-awareness occurs matters. The same

experimental manipulations (e.g. form-fitting clothing) in different contexts can have

substantially different meanings. Thus, enhanced awareness of one’s body in a context in

which the action is relevant to body-awareness (fitting one’s body through an aperture) is

substantially different from settings in which being induced to be aware of one’s body is not

relevant to the task (e.g. cognitive tasks).

However, the present results should also be considered within the context of a society

where sexual objectification of women’s bodies is prevalent, and societal pressures on

male’s physical appearance are much weaker (e.g. Swim et al., 2001). Accordingly women

may normally show a greater level of body awareness, and hence awareness of body–

environment fit, than males. Some support for this comes from the finding of a significant

sex difference in pi-numbers in the loose-fitting clothes condition. Women had lower pi-

numbers than men in this condition, consistent with the suggestion that women have a

chronically higher level of body awareness. As such, wearing the form-fitting outfit might

not have had as great an impact on the female participants in our study. Indeed the

pi-number for the male participants in the form-fitting clothing condition reduced to a level

similar to that of the female participants, a finding that is, consistent with females having a

chronically higher level of body awareness and self-environment fit.

In addition, only a main effect of sex of participant was seen for the perception trials.

Female participants had a significantly lower pi-number on the perception trials than did

male participants. This finding would also be consistent with the notion that females have a

chronically higher level of body awareness than do males. That the perception trials, unlike

the action trials, did not yield an interaction between sex and clothing type is not too

surprising given the difference in perception and action processes. Action involves a

continual retuning of perceptions. Perception, when examined in isolation from normal

action reattunement processes, lacks the tight interaction between perception and action

that is seen in action tasks (Richardson et al., 2007).

The current experiment has extended previous findings on the perception of self-

environment fit, specifically with reference to passability (Warren & Whang, 1987), and

also the impact of social psychological factors on such perception (Balketis & Dunning,

2007; Harber & Valree, 2008; Stefanucci et al., 2008). Our findings have demonstrated the

importance of considering the context in which actions occur. We showed that heightened

body awareness amongst male participants resulted in greater attunement to self-

environment fit, as represented by lower pi-numbers. The lack of impact of clothing type

for female participants is, we hypothesize, a consequence of chronically higher levels of

body awareness amongst females (e.g. Swim et al., 2001). A more stringent test of our

hypothesis that enhanced body awareness influences self-environment fit might have been

to use a fully within-subjects design with each participant completing the task wearing

each set of clothing. Clothing type was a between-subjects variable in the present research

Copyright # 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/acp

S. Lopresti-Goodman et al.

for pragmatic reasons—to reduce the time involved for each participant and, more

importantly, to reduce the possibility of participants becoming suspicious regarding the

experimental hypotheses and particularly that a difference was predicted in behaviour as a

function clothing type such that participants differentially altered their behaviour in

response to each clothing type. Future research should, however, consider within-subjects

effects.

At a more general level, our findings demonstrate that physical actions, such as walking

through a gap, are situated within a social environment. That individuals are situated within

social environments has consequences for their physical actions. The present research was

limited to consideration of waist-high apertures. Many apertures in everyday settings

extend above waist-height. For such apertures hip width may not be a salient feature, with

navigation through such apertures being influenced primarily by shoulder rather than hip

width (Warren & Whang, 1987). The extent to which tight-fitting clothing such as used in

the present research to heighten body awareness increases awareness of shoulder width is

unknown but it is likely to be less pronounced than the effect on hip width (Gupta et al.,

2001) and accordingly the impact of the form-fitting clothing and the consequent enhanced

body awareness may be limited to waist high apertures and not those apertures through

which navigation is primarily influenced by shoulder rather than hip width.

In addition to enhancing our understanding of individual’s navigation through the

environment, our findings have implications for situations in which individuals may be

being trained to be more body-aware, for example in sporting domains or in rehabilitative

physiotherapy. Increasing body-awareness can improve an individual’s ability to precisely

and accurately assess what they can do in a given environment—whether a handhold can

be reached in a climb, for instance, or whether an aperture can be navigated in a wheelchair.

Such skills are especially important for those recovering from injury or illness (e.g. strokes)

or for those acquiring or developing new skills in a sporting domain (e.g. high-jumping or

pole vaulting). Our research also suggests that attire might provide an avenue to increased

body-awareness. Such increased body-awareness again might be especially relevant in a

sporting domain. Although it has been noted that clothing in sports can improve the

effectivities of athletes (e.g. advances in swimsuit design in the 2008 Olympics, or lycra

biking shorts decreasing the effects of drag and decreasing muscle fatigue through the build

up of lactose acid and increasing muscle efficiency), the potential for increased body

awareness to mediate performance is overdue for study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a National Science Foundation grant, BSC-0342802,

awarded to Kerry L. Marsh, Claudia Carello, ReubenM. Baron andMichael J. Richardson.

REFERENCES

Angyan, L., Teczely, T., & Angyan, Z. (2007). Factors affecting postural stability of healthy youngadults. Acta Physiologica Hungarica, 94, 289–299.

Balketis, E., &Dunning, D. (2007). Cognitive dissonance and teh perception of natural environments.Psychological Science, 18, 917–921.

Copyright # 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/acp

Body-awareness and passability

Bongers, R. M., Smitsman, A. W., & Michaels, C. F. (2003). Geometrics and dynamics of a roddetermine how it is used for reaching. Journal of Motor Behavior, 35, 4–22.

Bongers, R. M., Michaels, C. F., & Smitsman, A. W. (2004a). Variations of tool and taskcharacteristics reveal that tool-use postures are anticipated. Journal of Motor Behavior, 36,305–315.

Bongers, R. M., Smitsman, A. W., & Michaels, C. F. (2004b). Geometric, but not kinetic, propertiesof tools affect the affordances perceived by toddlers. Ecological Psychology, 16, 129–158.

Carello, C., Grosofsky, A., Reichel, F. D., & Solomon, H. Y. (1989). Visually perceiving what isreachable. Ecological Psychology, 1, 27–54.

Carello, C., Thout, S., Anderson, K. L., & Turvey, M. T. (1999). Perceiving the sweet spot.Perception, 28, 307–320.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’slived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206.

Fredrickson, B. L., Roberts, T.-A., Noll, S. M., Quinn, D. M., & Twenge, J. M. (1998). That swimsuitbecomes you: Sex differences in self-objectification, restrained eating, and math performance.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 269–284.

Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.Gupta, M. A., Chaturvedi, S. K., Chandarana, P. C., & Johnson, A. M. (2001). Weight-related bodyimage concerns among 18–24-year-old women in Canada and India: An empirical comparativestudy. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 50, 193–198.

Harber, K. D., & Valree, D. (2008). Security, self-esteem, and the perception of height. Posterpresented at the meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Albuquerque, NM.

Hirose, N., & Nishio, A. (2001). The process of adaptation to perceiving new action capabilities.Ecological Psychology, 13, 49–69.

Kallen, R. W., & Quinn, D. M. (2007). That swimsuit disturbs me: Self-objectification processes,appearance ideals, and ideology. Manuscript under review.

Kinsella Shaw, J. M., Shaw, R. E., & Turvey, M. T. (1992). Perceiving ‘‘walk-on-able’’ slopes.Ecological Psychology, 4, 223–239.

Kuhn, M. H., & McPartland, T. S. (1954). An empirical investigation of self-attitudes. AmericanSociological Review, 19, 68–76.

Lipson, A. L., Pryzybyla, D. P., & Byrne, D. (1983). Physical attractiveness, self-awareness, andmirror-gazing behavior. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 21, 115–116.

Mark, L. S. (1987). Eye height-scaled information about affordances: A study of sitting and stairclimbing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 13, 361–370.

Mark, L. S., Balliett, J. A., Craver, K. D., & Douglas, S. D. (1990). What an actor must do in order toperceive the affordances for sitting. Ecological Psychology, 2, 325–366.

Mark, L.S., & Vogele, D. (1987). A biodynamic basis for perceived categories of action: A study ofsitting and stair climbing. Journal of Motor Behavior, 19, 367–384.

McKinley, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (1996). The objectified body consciousness scale: Development andvalidation. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 181–215.

Michaels, C. F. (2003). Affordances: Four points of debate. Ecological Psychology, 15, 135–148.

Michaels, C. F., & Carello, C. (1981). Direct perception. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.Muehlenkamp, J. J., & Saris-Baglama, R. N. (2002). Self-objectifications and its psychologicaloutcomes for college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 179–371.

Murray, S. J. (2003). The road-crossing safety ratio as an index of reduced mobility and risk-taking.Masters thesis, University of Canterbury, NZ.

Pepping, G. J., & Li, F. X. (2000). Sex differences and action scaling in overhead reaching. Perceptualand Motor Skills, 90, 1123–1129.

Quinn, D. M., Kallen, R. W., Twenge, J. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2006a). The disruptive effect ofself-objectification on performance. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 59–64.

Quinn, D. M., Kallen, R. W., & Cathey, C. (2006b). Body on my mind: The lingering effect of stateself-objectification. Sex Roles, 55, 869–874.

Reed, E. S. (1996). Encountering the world: Toward an ecological psychology. New York: OxfordUniversity Press.

Copyright # 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/acp

S. Lopresti-Goodman et al.

Richardson, M. J., Marsh, K. L., & Baron, R. M. (2007). Judging and actualizing intrapersonal andinterpersonal affordances. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Perform-ance, 33, 845–859.

Shaw, R. E., Flascher, O.M., &Kadar, E. E. (1995). Dimensionless invariants for intentional systems:Measuring the fit of vehicular activities to environmental layout. In J. Flach, P. Hancock, J. Carid,& K. Vicente (Eds.),Global perspectives on the ecology of human-machine systems (pp. 293–357).Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Shaw, R. E., & Turvey, M. T. (1981). Coaliltions as models of ecosystems: A realist perspective onperceptual organization. In M. Kubovy, & J. Pomeranz (Eds.), Perceptual organization (pp. 343–415). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Simpson, G., Johnston, L., & Richardson, M. J. (2003). An investigation of child road-crossing in avirtual environment. Journal of Accident Analysis and Prevention, 35, 787–796.

Steenbergen, B., van der Kamp, J., Smitsman, A.W., & Carson, R. G. (1997). Spoon handling in two-to four-year-old children. Ecological Psychology, 9, 113–129.

Stefanucci, J. K., Proffitt, D. R., Clore, G., & Parekh, N. (2008). Skating down a steeper slope: Fearinfluences the perception of geographical slant. Perception, 37, 321–323.

Stoffregen, T. A. (2003). Affordances as properties of the animal-environment system. EcologicalPsychology, 15, 115–134.

Stoffregen, T. A., Yang, C.-M., & Bardy, B. G. (2005). Afforance judgments and nonlocomotor bodymovements. Ecological Psychology, 17, 75–104.

Swim, J. K., Hyers, L. L., Cohen, L. L., & Ferguson, M. J. (2001). Everyday sexism: Evidence for itsincidence, nature and psychological impact from three daily diary studies. Journal of Social Issues,57, 31–53.

Turvey, M. T., & Shaw, R. E. (1979). The primacy of perceiving: An ecological reformulation ofperception for understanding memory. In L. G. Nilsson (Ed.), Perspectives on memory research:Essays in honor of Uppsala University’s 500th anniversary (pp. 167–222). Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Turvey, M. T., Shaw, R. E., Reed, E. S., & Mace, W. M. (1981). Ecological laws of perceiving andacting: In reply to Fodor and Pylyshyn(1981). Cognition, 9, 237–304.

van der Kamp, J., Savelsbergh, G. J. P., & Davis, W. E. (1998). Body-scaled ratio as a controlparameter for prehension in 5- to 9-year-old children.Developmental Psychobiology, 33, 351–361.

van Leeuwen, L., Smitsman, A., & van Leeuwen, C. (1994). Affordances, perceptual complexity, andthe development of tool use. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception andPerformance, 20, 174–191.

Wagman, J. B., & Carello, C. (2001). Affordances and inertial constraints on tool use. EcologicalPsychology, 13, 173–195.

Wagman, J. B., & Carello, C. (2003). Haptically creating affordances: The user-tool interface.Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 9, 175–186.

Wagman, J. B., & Taylor, K. R. (2005). Perceived arm posture and remote haptic perception ofwhether an object can be stepped over. Journal of Motor Behavior, 37, 339–342.

Warren, W. H. (1984). Perceiving affordances: Visual guidance of stair climbing. Journal ofExperimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 10, 683–703.

Warren, W. H., & Whang, S. (1987). Visual guidance of walking through apertures: Body-scaledinformation for affordances. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception andPerformance, 13, 371–383.

Webb, W. M., Marsh, K. L., Schneiderman, W., & Davis, B. (1989). Interaction between self-monitoring and manipulated states of self-awareness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychol-ogy, 56, 70–80.

Wicklund, R. A., & Duval, S. (1971). Opinion change and performance facilitation as a result ofobjective self-awareness. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 7, 319–342.

Wraga, M. (1999). The role of eye-height in perceiving affordances and object dimensions.Perception and Psychophysics, 61, 490–507.

Copyright # 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/acp