The (Dis) Articulation of Colonial Legacies in Calixta Gabriel Xiquin's Tejiendo Los Sucesos En El...

Transcript of The (Dis) Articulation of Colonial Legacies in Calixta Gabriel Xiquin's Tejiendo Los Sucesos En El...

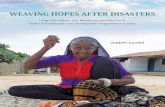

THE (DIS) ARTICULATION OF COLONIALLEGACIES IN CALIXTA GABRIEL XIQUÍN’S

TEJIENDO LOS SUCESOS EN EL TIEMPO/WEAVING EVENTS IN TIME

ALICIA IVONNE ESTRADA

THE bilingual collection of poetry Tejiendo los sucesos en el tiempo/Weaving Events in Time (2002) by Maya-Kaqchiquel writer and spiritualguide Calixta Gabriel Xiquín, is characterized by political denounce-ment to the social violence Mayas experienced during the Guatemalan(post)civil war period.1 The poems root this violence and historical mar-ginalization in colonial legacies that continue to exist in the country.These legacies also forcibly displace thousands of Guatemalans, includ-ing Gabriel Xiquín, to the United States. However, besides politicaldenouncement, Tejiendo los sucesos en el tiempo/ Weaving Events inTime equally expresses and inscribes not only Maya cultural and spiritu-al practices, but also affirms another way of remembering and recordingcontemporary Guatemalan history. The book provides a public culturalrecord that is critical of official historical accounts.

Calixta Gabriel Xiquín’s text is a lyrical textile. Each of the sevensections, “Roots,” “Uprooting,” “Quest,” “Taking the Word,” “Refuge,”

137

1 During the 36-year civil war in Guatemala (1960-1996) over 200,000 people died.The United Nations’ Historical Clarification Commission reports that over 80% of thosekilled by the army were Mayas. For more on the Guatemalan civil war, see the humanrights report Guatemala: Never Again! (1999). Also, Ricardo Falla’s Masacres de la sel-va: Ixcán, Guatemala (1975-1982) (1992); Susanne Jonas’s The Battle For Guatemala:Rebels, Death Squads, and U.S. Power (1991); Beatriz Manz’s Refugees of a HiddenWar: The Aftermath of the Counterinsurgency in Guatemala (1988); Rigoberta Menchú’stestimonial I, Rigoberta Menchu: An Indian Woman in Guatemala (1987); Victor Monte-jo’s Testimony: Death of a Guatemalan Village (1987).

“Testimony,” and “The Return,” encode the varied forms of physical,sexual, and epistemological violence historically waged against indige-nous peoples in Guatemala.2 All the sections denounce the established(neo) colonial systems that provide the foundation for transnational cap-italism that exploits Mayas today. To counteract these systems, the textinverts (neo) colonialism by centralizing Maya culture and spiritualityas important tools for resistance. Structurally, the language and use offree verse make the poems read like narratives that tell a story much likein the oral tradition. Many of the poems, like “Indian,” “Writing,” “TheWalk of the Poor,” and “Poem,” read like personal, and spiritual conver-sations between members of the Maya community, outsiders, as well aswith the spirits of Maya ancestors, the earth and heavens.

Gabriel Xiquín’s aesthetic style is one that Native American scholar,Janice Gould in “American Indian Women’s Poetry: Strategies of Rageand Hope” (1995), describes as a shared element in indigenous writings:“Our poetry, as story and record, is part of the fabric of oral tradition,transliterated finally into the rhythms, structures, and techniques of con-temporary verse. It is woven out of the life stories we tell one another,sometimes in tears, sometimes in rage, stories recollected, envisioned,and breathed into existence” (798). It is through these stories that Tejien-do los sucesos del tiempo/ Weaving Events in Time articulates Maya cos-mologies as a discourse that affirms Maya resistance and survival. Tak-ing this context as a point of departure, in this article I analyze fourpoems, “Indian,” “Writing,” “The Walk of the Poor,” and “Poem,” toargue, first, the ways in which language and the production of Eurocen-tric knowledge in the West sustains the everyday systematic violenceand marginalization of indigenous peoples. And second, I show howthese colonial legacies are challenged through the appropriation ofSpanish language to affirm Maya culture, history and spirituality.

COLONIAL LEGACIES AND CULTURAL RESISTANCE

In the poem “Indian,” the violence of colonization is made visibleby noting the ways in which colonialism continues to exist through the

138 ROMANCE NOTES

2 My own translation from the original Spanish, “El Retorno.” In the book, transla-tors Susan G. Rascón and Suzanne M. Strugalla, translate the section as “ComingHome.”

codification of language, as it is explicit in the title of the poem. It givestestimony to the everyday experience of Mayas in Guatemala where theterm Indio is many times used in derogatory ways by non-indigenousGuatemalans to justify and establish racial hierarchies.3

The adjective “Indian” is the first line for each of the ten stanzas.The repetition of the term underscores the visible presence of the con-cept in Guatemalan society. The denouncement becomes urgent, in theseventh stanza, particularly as the speaker lists the material conditionsof Maya communities in Guatemala, where they are denied basic neces-sities like the right to formal education, medical attention and drinkingwater. Addressing an audience that the speaker assumes is Indian, thepoetic voice notes:

Indian, survivor, you have no schools,drinking waterelectricity, orroads. You have no health care.

Indian,you are not acknowledged by the blind oppressor.

Indian, they tell you that you are ignorant, conformist, the country’s backwardness.They deny you everything. (7)

The depictions of these dire material conditions serve to raise the socialconsciousness of the speaker’s assumed Indian audience. The appeal toaction is further illustrated in the stanzas that follow when the speakerdismantles the misrepresentations constructed “by the [Indian’s] blindoppressor” (7). This is evident in the reconceptualization of the adjec-tive “Indian,” where the “Indian” is constructed as an active, thinkingsubject:

THE (DIS) ARTICULATION OF COLONIAL LEGACIES 139

3 For a study about racism in contemporary Guatemala see La metamorfosis delracismo en Guatemala (1998) by Marta Elena Casaús Arzú.

Indian, eternal owner of the earth,architect of the fields,born of corn,fighting for justice.

Indian, you seek equality among all,you are made of light, you are the world’s brightness, a free person of systems, independent.

Indian, you create free music,you sing with nature,you are the friend of birds, neighbor of plants, child of the day. (5)

In the above stanzas the speaker describes a subject that is actively cre-ating her own identity, her place in society and the world, asserting Indi-anness as an ethnic identity with positive value. Consequently, the sub-ject is now defined in harmony with nature and society. The referencesto corn, and particularly the connection of corn with birth, reaffirmMaya cultural practices and worldviews that define and singularize Indi-anness. In this space, where culture is affirmed, the Indian is a subjectfree and independent from the systems that subjugate him. This is high-lighted in the third stanza through the isolation of the adjective “indepen-dent,” which suggests a spiritual and cultural freedom from (neo) colonialsystems.

The poem ends where the racist linage of the pejorative categoryIndian, and the marginalization of Mayas, historically began:

Indian,this story began in 1492with the Spanish invasion andwas perpetuated by their offspring,marginalizing the Maya ever since. (7).

And whereas at the end of the poem there is a condemnation of colonial-ism, in the last verse the poetic voice replaces the conquistador’s imposed

140 ROMANCE NOTES

category with “Maya” to assert an ancestral identity and a politicizedethnic consciousness.4 In this context, the poem can be associated to theethnic movement that endorses Mayanness, rather that Indianness, asan ethnic category of empowerment. Thus, the affirmation of a Mayaidentity in the last verse reaffirms Maya cultural practices and world-views as a discursive practice of liberation from the subjugated subjec-tivity imposed by the colonial system.

THE (DIS)JUNCTIONS IN WRITING AND ORALITY

As the poem “Indian” denounces the ideologies and politics thatimpose an Indian identity, the poem “Writing” displays the (dis)junc-tions between writing and orality. The speaker in this poem emphasizesthat the West has used writing to epistemologically Other indigenouspeoples. At the same time, the speaker draws connections between writ-ing poetry and the oral tradition through the appropriation of literaryforms in order to document injustice. In his book Kotz’ib’: Nuestra Li-teratura Maya (1997), Maya Q’anjob’al writer and critic Gaspar PedroGonzález explains that Maya writers have used orality, the literature oftheir ancestors, as a base for contemporary Maya poetry, novels andshort stories (98). Gabriel Xiquín’s poem “Writing” highlights this con-nection between poetry and oral tradition when the speaker states:“Today I raise my song to heaven,/my song, the voice of my people”(3). Here, poetry is associated to a spiritual song in conversation withthe heavens.

The poem “Writing” simultaneously reminds us, like Walter Mingo-lo suggests in “Literacy and Colonization: The New World Experience”(1992), that Europeans built their own identity through the creation ofimages that Othered indigenous peoples. In this process, the notion thatindigenous people “lack alphabetic literacy” becomes a central markerof Otherness (54). And while for sixteenth-century Spanish missionar-ies alphabetic literacy was the only practice with the authority to pro-

THE (DIS) ARTICULATION OF COLONIAL LEGACIES 141

4 For Santiago Bastos and Manuela Camus, in Entre el mecapal y el cielo: Desarro-llo del movimiento maya en Guatemala (2003), to identify as Maya in Guatemala meansto be part of a historically grounded collectivity, which is tied to common ancestors, his-tory, and culture (18).

duce history (Mignolo 54), the supposed lack of letters did not impedeindigenous peoples from maintaining their history through orality. Inthis context, the poem “Writing” makes visible the ways in which West-ern ideological models, which situate indigenous knowledge at thebeginning of human development, continue to marginalize indigenouspeoples today. The speaker notes that

Researchersuse the indigenous peoples for their studiesexamining human beings as specimens,relics of history.

Ignorant of our philosophy and our culture,… (3)

The reference to the researchers’ construction of knowledge in GabrielXiquín’s poem suggests, much like the sixteenth century Spanish mis-sionaries and conquistadors’ colonial projects described by Mignolo, adehumanization of indigenous peoples by placing them as “specimens”and not subjects who contribute to our understanding of the world. Intheir exchange with indigenous peoples, the significance and culturalmeanings of the communities they write about are misrepresented,ignored and erased. The stanza also draws attention to the ways the Westwrites and capitalizes on the Other. In a similar claim to Edward Said’sconclusions about the West’s production of the Orient in Orientalism(1978), Gabriel Xiquín’s “Writing” reminds us that the knowledge aboutindigenous peoples produced, packaged, and circulated by Eurocentricresearchers is an essential aspect of (neo) colonial power structures.This is because through their marginalization and trampling the Westhas maintained an economic system that capitalizes on indigenous laborand culture to sustain itself.

And while there is a denouncement towards Western epistemologi-cal approaches, the very title of the poem, “Writing,” suggests an appro-priation of alphabetic literacy practices. In this process alphabetic litera-cy is used to denounce the power relations that are created andmaintained by today’s lettered class: “Researchers.” It is because of thisthat the poetic voice affirms:

142 ROMANCE NOTES

In blood I will write the history,the people’s suffering in misery.With poetry I record the chill of injustice,hunger,poverty andpain (3).5

Poetry, then, does not only provide an artistic and cultural space ofstruggle but it is also a mechanism used to (re)articulate the history of apeople, to simultaneously record the injustices committed against them.In many ways, like indigenous intellectuals from the 16th century, todaythe speaker continues to write “in blood…the history” (1) of indigenouspeoples. Similarly, just like her ancestors in previous centuries, theMaya speaker must deal with, what Mignolo calls, the “conflictive situ-ation” of recording the memories of the community while Western “menof letters” claim authority in the writing of those histories.6 Hence, thepoem suggests an urgent call and legacy, to write “in blood” the oral his-tories of a people that continue to suffer, but also resist, the legacies ofcolonialism.

(DIS)PLACEMENT

Besides denouncing injustices against indigenous peoples, Tejiendolos sucesos en el tiempo/Weaving Events in Time makes visible theirforced migration to the United States. While in the previous poems themarginalization of indigenous peoples takes place in their homeland, in“The Walk of the Poor” oppression acquires global significance. Thespeaker states that as a result of these transnational capitalist systemsindigenous peoples and the poor must cross:

THE (DIS) ARTICULATION OF COLONIAL LEGACIES 143

5 This is my own translation of the poem from the original Spanish: “Con sangre voya escribir la historia” (Gabriel Xiquín 2). The English translation appears as: “In blood Iwill write the story” (Gabriel Xiquín 3). I prefer to translate the Spanish historia as histo-ry rather than story because the latter suggests an account while history implies thespeaker’s knowledge of her community’s past.

6 Walter Mignolo’s direct claim is that “at the end of the sixteenth century…[indige-nous intellectuals were] dealing with the conflictive situation of rearticulating the memo-ries of their communities…[and] with the fact that men of the letters, missionaries, andsoldiers took the liberty to write Amerindian memories.” (190).

borders under rubble and bridges,hiding from immigration,because neither here nor there is there life for them,and wherever they go they will always come up against thesystems (53).

The isolation of the word “systems” in the stanza emphasizes displace-ment as a systematic experience. The speaker’s pronouncement that“…neither here nor there is there life for them,” roots the poor’s dis-placement on a transnational (neo) colonial dimension. And thus, thepoor must “…walk day and night without rest,” “hiding from immigra-tion,” to capitalist centers in search for “…nourishment” (53). Herdenouncement of the poor’s displacement is important, not only becauseit highlights migration as a consequence of global capitalism, but it alsosituates migratory movements as forced and not as an individual choice.It provides an important testament to the experiences shared by manyGuatemalans living in the United States, who were forced to leave thecountry as a result of the civil war.7

However, like in the previous poems, while there is a denouncementto repressive systems, hope is also expressed. This is illustrated at thebeginning of the poem, in recurring images that display migration notas a movement that equates a disconnection from the place of origin,but rather, a walk through their ancestral land, carving “the face ofIndoamerica with their steps” (53). The walk of the poor in this senserepresents a rootedness to the land that continues to exist through theexpression of their cultural, spiritual and philosophical practices in thediaspora.

144 ROMANCE NOTES

7 Nora Hamilton and Norma Stoltz Chinchilla note, in Seeking Community in GlobalCity: Guatemalans and Salvadoran in Los Angeles (2001), “[i]n 1984, for exam-ple,…[only] 0.4 (3 of 761) of Guatemalan requests [for political asylum] were granted”(135). This is because in the United States Guatemalan migration has been mainly per-ceived as “voluntary” and based on the individual’s desire for economic mobility. Thisclassification not only denies Guatemalan immigrants political asylum, but also fails torecognize their forced displacement as a direct result of a U.S. backed civil war. For moreon this topic see James Loucky and Marilyn M. Moors’s Maya Diaspora: GuatemalanRoots, New American Lives (2000).

POETIC TEXT(ILE)S

Tejiendo los sucesos en el tiempo/Weaving Events in Time ends withthe section titled “The Return,” and with “Poem,” which differs fromthe others in the collection. Instead of focusing on political denuncia-tion, it celebrates Maya women who weave and write poetry. In “Poem”poetry is heard, understood and created within Maya cultural settings.Poetry is, as the poetic voice notes, “Feeling and voice of my people,”(89). Writing poetry and weaving textiles are associated as alike artisticforms because they interweave Maya culture and history: The Mayawoman “…weaves the poetry of sorrow” (89). In this way, the poetrywritten by Maya women, like the textiles they wear and weave, remindus of Irma Otzoy’s assessment about “Maya Clothing and Identity”(1996). Textiles speak “of the Maya as a people, of their roots, of theirlives, and their causes.” (Otzoy 149). They maintain and illustrate a his-torical memory that is both personal and collective.

In this context, “Poem” transforms the meaning and function of theliterary form into a weaved textile which is meditated, sang, and imag-ined. Poetry and weaving, in turn, are equally tied to the oral tradition.With a celebratory tone the speaker declares:

Poem, I writePoem, I sayPoem,voice of the timeless man and womanPoem, I singpoems, I read with my peopleI meditate poemsshe weaves…poetry (89).

In the above stanza, poetry, like the Maya woman who weaves andwrites, becomes active artistic productions that convey the lived histo-ries of Maya peoples. The speaker notes that the Maya weaver’s

...soul creates hopewith her hands the colors,red, yellow, blue, green and black.With these colors she weaves the poetry of sorrow,of pain, of agony andof hope. (89)

THE (DIS) ARTICULATION OF COLONIAL LEGACIES 145

The poem concludes with the verse, “of hope,” which associates Mayaresistance to the textiles women weave and wear.8 In their textiles theinscriptions, of cultural and spiritual symbols, provide the world a textto read (Otzoy 147). This is evident in the reference to the colors theweaver uses “red, yellow, blue, green and black.” The colors in theweaver’s hands could be associated to the colors of the candles used forMaya spiritual ceremonies. Hence, Maya women through their dressdisplay their history, resistance, creativity and worldview. The poemdepicts Maya women as active historical subjects claiming their placeand authority in cultural settings that traditionally have excluded or rele-gated them to the margins.

CONCLUSION

Calixta Gabriel Xiquín’s Tejiendo los sucesos en el tiempo/ WeavingEvents in Time illustrates to readers alternate forms of knowing, readingand writing through a poetry that is inclusive of Maya history, ideolo-gies and cultural practices. The book also serves as a testimony to thecontemporary and historical struggles of Mayas in Guatemala. Similarto testimonial narratives many of the poems in Tejiendo los sucesos enel tiempo/ Weaving Events in Time aim at raising the social conscious-ness of its readers. In doing so, the text invites non-Maya readers to crit-ically consider the ways colonial legacies are also fundamental to theestablishment of transnational capitalism which further marginalize anddisplace indigenous peoples today.

In this multivocal text, Maya ideologies and cosmologies are situat-ed as central to the contemporary Maya movement, since they serve asan important tool of resistance and empowerment. Most importantly,Gabriel Xiquín’s poetry situates Maya women as active historical sub-jects and demonstrates the different ways Maya women participate indenouncing global and local systems of oppression. In particular, the

146 ROMANCE NOTES

8 For Otzoy the resistance is explicit in the courage Maya women express as they“openly defy a [racist] society that discriminates against them…in wearing [and weav-ing] Maya clothing, [they] demonstrate their identity and impart a lesson of active cultur-al resistance.” (147).

poems expose the intellectual and political contributions made by Mayawomen through their efforts to record both ancestral and contemporaryMaya history in the text(iles) they write, weave and wear.

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE

WORKS CITED

Bastos, Santiago and Manuela Camus. Entre el mecapal y el cielo: Desarrollo delmovimiento maya en Guatemala. Guatemala: Flacso, 2003.

Casaús Arzú, Marta Elena. La metamorfosis del racismo en Guatemala. Guatemala:Cholsamaj, 1998.

Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico. Guatemala: Memoria del Silencio. Gua-temala City: Litoprint, 1999.

Gabriel Xiquín, Calixta. Tejiendo los sucesos en el tiempo/Weaving Events in Time. Ran-cho Palos Verdes: Yax Te’ Foundation, 2002.

Gonzáles, Gaspar Pedro. Kotz’ib: Nuestra Literatura Maya. Cleveland: Yax Te’ Books,1997.

Gould, Janice. “American Indian Women’s Poetry: Strategies of Rage and Hope.” Signs.20.4 (1995): 797-817.

Hamilton, Nora and Norma Stoltz Chinchilla. Seeking Community in Global City:Guatemalans and Salvadoran in Los Angeles. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 2001.

Loucky, James and Marilyn M. Moors, eds. Maya Diaspora: Guatemalan Roots, NewAmerican Lives. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 2000.

Mignolo, Walter D. “Literacy and Colonization: The New World Experience.” 1492-1992: Rediscovering Colonial Writing. Eds. René Jara and Nicholas Spadaccini,Minneapolis: Prisma Institute, 1989. 51-96.

––––––. “When Speaking was not Good Enough: Illiterates, Barbarians, Savages andCannibals.” Amerindian Images and the Legacy of Columbus. Eds. René Jara andNicholas Spadaccini. Minneapolis: Minnesota UP, 1992. 312-345.

Otzoy, Irma. “Maya Clothing and Identity.” Maya Cultural Activism in Guatemala. Eds.Edward F. Fischer and R. McKenna Brown. Austin: Texas UP, 1996. 141-155.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

THE (DIS) ARTICULATION OF COLONIAL LEGACIES 147

Copyright of Romance Notes is the property of University of North Carolina, Department of RomanceLanguages and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without thecopyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles forindividual use.