The content validity of the Behaviour Support Plan Quality Evaluation tool (BSP-QEII) and its...

Transcript of The content validity of the Behaviour Support Plan Quality Evaluation tool (BSP-QEII) and its...

The content validity of the Behaviour Support PlanQuality Evaluation tool (BSP-QEII) and its potentialapplication in accommodation and day-support servicesfor adults with intellectual disabilityjir_1602 1..13

K. McVilly,1 L. Webber,2 G. Sharp1 & M. Paris1

1 School of Psychology, Deakin University, Melbourne,Victoria, Australia2 Office of the Senior Practitioner, Department of Human Services, Melbourne,Victoria, Australia

Abstract

Background The quality of support provided topeople with disability who show challengingbehaviour could be influenced by the quality ofthe behaviour support plans (BSPs) on whichstaff rely for direction. This study investigated thecontent validity of the Behaviour Support PlanQuality Evaluation tool (BSP-QEII), originallydeveloped to guide the development of BSPsfor children in school settings, and evaluatedits application for use in accommodation andday-support services for adults with intellectualdisability.Method A three-round Delphi study involving apurposive sample of experienced behaviour supportpractitioners (n = 30) was conducted over an 8-weekperiod. The analyses included deductive contentanalysis and descriptive statistics.Results The 12 quality domains of the BSP-QEII were affirmed as valid for application inadult accommodation and day-support service

settings. Two additional quality domains weresuggested, relating to the provision of detailedbackground on the client and the need for plansto reflect contemporary service philosophy. Fur-thermore, the results suggest that some issuespreviously identified in the literature as beingimportant for inclusion in BSPs might not cur-rently be a priority for practitioners. Theseincluded: the importance of specifying replacementor alternative behaviours to be taught, descriptionsof teaching strategies to be used, reinforcers, andthe specification of objective goals against whichto evaluate the success of the interventionprogramme.Conclusions The BSP-QEII provides a potentiallyuseful framework to guide and evaluate the develop-ment of BSPs in services for adults with intellectualdisability. Further research is warranted to investi-gate why practitioners are potentially giving greaterattention to some areas of intervention practicethan others, even where research has demonstratedthese others areas of practice could be important toachieving quality outcomes.

Keywords assessment, behaviour support plan,challenging behaviour, validity

Correspondence: Dr Keith McVilly, School of Psychology,Deakin University, Melbourne, Victoria 3125, Australia (e-mail:[email protected]).

Journal of Intellectual Disability Research doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01602.x1

bs_bs_banner

© 2012 The Authors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Introduction

The quality of support provided to people withintellectual disabilities (ID) has long been debatedin the scientific literature, and many attempts havebeen made at both policy and clinical levels tomeasure this allusive construct (Borthwick-Duffy1996; Brown 1997; Stancliffe & Lakin 2005;Mansell 2006). For people with ID who alsoexhibit challenging behaviours, measures of servicequality have now moved beyond administrative cri-teria focusing on the extent to which services bringabout changes in the frequency and duration ofbehaviour, or clinical criteria addressing changes inthe form of behaviour, and the acquisition of alter-native behaviours. The contemporary servicequality agenda is now focused on the extent towhich services act ethically, recognise and upholdpeople’s human rights and, importantly, minimisepractices which infringe on people’s human rights(Allen 2008; French et al. 2010; Emerson &Einfeld 2011).

People whose behaviours give rise to their refer-ral for behaviour intervention, or behavioursupport, are particularly at risk of infringements oftheir human rights (Webber et al. 2010). Suchinfringements can take the form of restrictive prac-tices such as chemical restraint, physical ormechanical restraint, and seclusion (McVilly 2009),and can have long-term adverse effects (Bird &Luiselli 2000). To minimise the misuse of thesepractices and promote quality in both serviceprovision and service outcomes for this group,the principles and practices of Positive BehaviourSupport (PBS) are now widely accepted and pro-moted (Carr et al. 1999; Sugai et al. 2000; Allenet al. 2005; Lowe et al. 2005; McVilly 2007). PBSbuilds on the science of applied behaviour analysisand seeks to address both deficient skill sets andcoping abilities inherent in the individual, and atthe same time address deficiencies in the environ-ment that have contributed to the person’s initialneed to use challenging behaviours, and their con-tinued use of these behaviours (Carr et al. 2002;Johnston et al. 2006).

Clinical assessment and evidence-based formula-tion informed by PBS, together with the educationof those providing primary support are importantsystemic elements for ensuring quality in service

provision and service outcomes. However, giventhe complexity that often characterises the provi-sion of support, and the multiplicity of peopleinvolved, the quality of the documentation associ-ated with the process, namely the behavioursupport plan (BSP), could be critical to success(Webber et al. 2011a).

When considering the quality of BSPs, sixconcepts have been identified, and are empiricallysupported, as important for effective behaviouralsupport planning (Horner et al. 2000). Theseinclude: having an objective definition of the behav-iour and its hypothesised function – what are thebehaviours of concern and what functions doeseach serve; situational specificity – when and wheredo the behaviours occur, or not occur; strategies tosupport behavioural change – including both envi-ronmental change strategies and skills teaching;reinforcement of adaptive behaviours and the non-use of the behaviour; reactive strategies to use whenbehaviours emerge – along a continuum from theleast restrictive first; and team co-ordination andcommunication. Horner et al. (2000) assert that ifthese guidelines for the formulation of BSPs arefollowed, staff will develop an effective, evidence-based plan which should result in a better quality ofservice being provided to the client, and a servicewhich promotes their health, well-being and qualityof life and, importantly, supports their humanrights.

Phillips et al. (2010) developed a tool to assessthe extent to which BSPs for people with ID wereinclusive of best practice criteria, such as thoseproposed by Horner et al. Their study includeda comparison of plans prepared prior to and fol-lowing the introduction new legislation (DisabilityAct [Victoria], 2006) governing the support ofpeople with disability, including explicit provisionsfor the planning, implementation and review ofbehaviour support programmes designed to safe-guard people’s civil and human rights. The studyconcluded that there exists a lack of best practicecriteria in BSPs and direct support staff are illequipped to execute behaviour support strategies,despite a legislative framework to support theseinterventions. However, to date there is limitedevidence of the validity and reliability of theirtool, given the study was based on a relativelysmall sample, and drawn from a single community

2Journal of Intellectual Disability Research

K. McVilly et al. • BSP-QEII validity for adult services

© 2012 The Authors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

service provider agency. Further work in thisdirection holds promise to better inform policyand clinical developments.

In a similar attempt to construct a best practiceframework to both inform the education of staffand evaluate the formulation of BSPs, the Behav-iour Support Plan Quality Evaluation Guide II(BSP-QEII) was developed (Browning-Wright et al.2003). The BSP-QEII includes 12 rating itemsassessing various substantive aspects of plans (e.g.quality of behaviour definition, specification of ante-cedents, identification of behaviour function). It hasmainly been used and evaluated in the USA, ineducational settings to support children with chal-lenging behaviour, where it has been found to bea reliable evaluation tool (Cook et al. 2012). Forexample, one study examined plans written by edu-cators (Cook et al. 2007). The study found only11% of the plans developed by typical school teamswere rated as ‘Adequate’ compared to 65% of theplans from teams with more experienced and skilledstaff members involved, and who had received spe-cific instruction in the principles of PBS. In anotherschool setting for children with autism, the BSP-QEII was used to assess the effect of a specific brieftraining delivered to improve BSPs (Kraemer et al.2008). The study used the BSP-QEII to evaluateplans both pre and post training. Results revealedthat training improved the quality of BSPs.However, the findings indicated the majorityof BSPs developed were still inadequate andpotentially legally invalid due to substantive andprocedural violations.

Based on these findings, it is possible that theBSP-QEII could offer a potentially useful measureof the quality of behaviour support documentationin adult settings too. McVilly et al. (2012) andWebber et al. (2011b) report evidence of accept-able levels of inter-rater agreement for the major-ity of the individual items, when used by peoplewho have undertaken some minimal trainingand practice. With the exception of the abovestudies, to date the BSP-QEII has generally beenapplied in the USA to the assessment of BSPsdeveloped by teachers in school settings tosupport children with disability. The extent towhich these findings can be generalised to thesupport of adults in community-based accommo-dation and day-support organisations supported

by psychologists and allied health professionalsrequires further investigation.

As part of a programme of research examiningthe potential application of the BSP-QEII incommunity-based services for adults with ID,including the reliability of the tool (see McVillyet al. 2012), the current study investigated thevalidity of the BSP-QEII in the context of its useby psychologists and allied health professionals incommunity based services for adults with ID. Thevalidity of an assessment refers to its true capacityto measure what it purports to measure (Groth-Marnat 2009); in this instance, the quality ofBSPs. There are different ways of assessing valid-ity. At its most basic is face validity, which asks thequestion would those with expertise recognise thetool as measuring what it claims to measure.However, face validity remains relatively subjective.A related, but more rigorous approach is that ofestablishing content validity. While still relying onpractitioner judgement, content validity typicallyinvolves a series of practitioners selected for theirexpertise rating various items or domains of theassessment, according to an objective scale. Afterthe content validity has been established, furthermodelling can be conducted to establish the con-struct validity of the items (i.e. do individual itemsin the instrument measure-related issues, or dodifferent results emerge as might be predictedwhen the instrument is used in different situations,and can the instrument satisfactorily distinguishbetween plans developed in different situations orcircumstances). Where similar tools already exist, itwould be possible to evaluate the tool’s concurrentvalidity. Finally, it might be important to establishthe tool’s predictive validity, with respect to certainclinical criterion. For example, high scores ona tool such as the BSP-QEII might predicthigh-quality service outcomes for people witha disability.

The current study was designed to assess thecontent validity of the BSP-QEII. This was under-taken with reference to the opinion of clinicalexperts working with adults with ID in communitybased accommodation and day-support settings. Itwas predicted that given the criteria of the BSP-QEII is based on best practice as derived from theresearch literature there would be high endorsementof these concepts by experienced practitioners.

3Journal of Intellectual Disability Research

K. McVilly et al. • BSP-QEII validity for adult services

© 2012 The Authors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Method

Ethics

Ethics approval for this study was provided bythe Deakin University Human Research EthicsCommittee.

Procedure

Consistent with the focus on establishing thecontent validity of the BSP-QEII, within thecontext of service provision to adults with ID incommunity-based services, the investigation wasconducted as a three-round Delphi study (Mullen2003). Delphi studies are designed to source theopinion of persons who are expert in a particulararea, and to devise a consensus of opinion amongsuch an expert group. They typically involve mul-tiple rounds of data collection, where by partici-pants proposes the key constructs for considerationand then over a series of contributions provideratings and evaluation of each other’s opinions. Thecurrent Delphi study was conducted over a periodof approximately 8 weeks, with each round activefor up to 2 weeks at a time.

Round One asked participants to list in dot-point form, in their expert opinion, key indicatorsof a quality BSP. Deductive content analysis(Krippendorff 2004) was then used to group thecomments according to the existing 12 quality cri-teria of the BSP-QEII, with provision made forthe development of additional thematic groups asmight be suggested by the data. Deductive contentanalysis was used given that one aim of the studywas to evaluate the a priori theoretical frameworkof BSP-QEII. To address the potential for bias inthe analysis, members of the research team firstindividually considered the grouping of the items,and the final Round One grouping was then facili-tated though a consensus coding process amongthe research team as a whole, in which each ofthe responses were discussed and the rationale fortheir allocation to a category debated among theresearchers. Here it should be noted that weintentionally chose not to simply ask the expertpractitioners to make direct ratings on the 12

BSP-QEII items in Round One, to avoid tauto-logical endorsement of items that already had facevalidity in the research literature.

Round Two included three tasks. Participantsreviewed the researchers’ allocation of their com-ments (provided in Round One) to the various cat-egories. Participants indicated if they believed theallocation of each comment was appropriate, and ifnot they had the option to suggest a re-allocation.This process was devised to further address anypotential bias in the researchers’ original allocationof items, and to address issues of trustworthiness inthe data (i.e. the qualitative equivalent of validity).Participants then indicated if they considered eachindividual comment as being essential to a qualityBSP. Participants were then asked to rate each ofthe 12 BSP-QEII quality categories, and the twoadditional categories that had emerged from theanalysis of the Round One data, according to howessential these general overarching categories wereas quality indicators for BSPs. For these 14 over-arching categories, participants responded using a10-point Likert scale: 0 = not required; 1–3 = notimportant; 4–6 = important; 7–9 = very important;10 = essential for inclusion.

Round Three asked the participants to rate theindividual comments, originally generated in RoundOne and then identified as a sub-set in Round Twoas being among the most frequently endorsed asessential to a quality BSP. To provide these ratings,participants recorded responses on the same10-point scale used in Round Two to rate the 14

general overarching categories.

Participants

Purposive sampling was undertaken. This is therecommended approach for Delphi studies, whichby design seek to recruit persons with specificexperience and expertise. Subsequently, the inclu-sion criteria sought to recruit persons with experi-ence and professional responsibility for thedevelopment of BSPs in adult disability services.Primarily these people were employed ingovernment-run specialist behaviour interventionteams. However, some professionals with similarresponsibility in community service organisationswere also included in the recruitment process. Therecruitment process involved service managers cir-culating an approved Plain Language Statementinviting staff who met the inclusion criteria tovolunteer for the study.

4Journal of Intellectual Disability Research

K. McVilly et al. • BSP-QEII validity for adult services

© 2012 The Authors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

In total there were 80 eligible participants, ofwhich 30 agreed to participate (representing a37.5% response rate). There were 10 men and 20

women. They ranged in age from 23 to 57 years(M = 37.8; SD = 10.11). Their experience in disabil-ity services ranged from 6 months to 33 years(M = 12.58; SD = 8.73). They reported a variety ofqualifications (and combination of qualifications),including graduate level qualifications in psychol-ogy, speech pathology and occupational therapy, aswell as qualifications in nursing and as psycho-educational trainers. Overall, this group was typicalof those involved in the provision of assessment andbehaviour programme development for adults withID in this jurisdiction. All fulfilled very similarroles, dedicated full time to developing and review-ing BSPs for adults with ID in community-basedaccommodation and day-support services.

Results

Delphi Round One

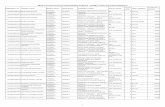

Participants in Round One provided 273 individualcomments. Each of the participants’ commentswere allocated to one of the 12 BSP-QEII catego-ries, by means of deductive content analysis andconsensus coding. Taking into account duplicationsand similar comments made by individual partici-pants, a total of 97 different comments were distrib-uted across the 12 BSP-QEII categories. Inaddition, two additional categories emerged as aresult of the content analysis (background on theperson with disability, and details reflecting contem-porary philosophy of service provision). The distri-bution of comments to the BSP-QEII categoriesand the two additional categories is given inTable 1.

Delphi Round Two

For the 97 individual comments extracted fromRound One and allocated across the 14 categoriesfor Round Two, 49 individual suggestions weremade for the reallocation of comments to other cat-egories. However, there were no consistent sugges-tions across participants (i.e. all suggestions forre-allocation were unique to individual partici-pants). Overall, these results were interpreted as

affirming the research team’s original consensusallocation of the items to the 12 BSP-QEII catego-ries plus the additional two categories whichemerged from the coding process. Consequently,the items as allocated following Round One wereretained in their respective groupings for RoundThree.

All 97 items presented to participants in RoundTwo were rated as essential to a quality BSP. Theseare presented in Table 2. However, the extent towhich they were endorsed ranged between 20% ofrespondents and 80% of respondents. Overall,items were endorsed as being essential by 47% ofparticipants.

From these items the researchers extracted thosethat had endorsement by at least 60% of respon-dents. Subsequently 26 items were identified. Theseitems formed the basis of Round Three (describedlater).

In Round Two, participants also rated the 14

overarching categories (12 from the BSP-QEII andthe additional two to emerge from the analysis ofthe Round One data) on a scale of 0 (not requiredin a BSP) to10 (essential for inclusion in a BSP).The results of these ratings are shown in Table 3.Overall, there was a high level of endorsement forall of the categories, with the mean scores indicat-ing respondents to consider each of the categoriesto be very important to essential to a quality BSP.The only category not to attain a mean ratingwithin the range indicating it to be at least veryimportant was ‘Reinforcers are described to encour-age the use of replacement behaviours and rewardthe non-use of BoC’. This item received a meanrating of 6.93 (i.e. important).

Delphi Round Three

Table 4 displays the mean item ratings from RoundThree for each of the 26 statements, which hadpreviously achieved endorsement as essential to aquality BSP by at least 60% of participants inRound Two. All items were rated by participantswithin the range indicating them to be very impor-tant (M = 9.40). The item with the highest level ofendorsement (M = 10.00) was ‘Purpose and func-tion of the behaviour’. The least endorsed itemwas ‘Authorisation’ (M = 8.88). Here it should benoted that only 10 of the 14 quality domains were

5Journal of Intellectual Disability Research

K. McVilly et al. • BSP-QEII validity for adult services

© 2012 The Authors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

represented by way of comments that were amongthose endorsed by at least 60% of participants. Thequality domains not represented in the final roundby comments from Round Two were: replacementor alternative behaviours to be taught, teachingstrategies, reinforcers, and goals and objectives forthe intervention programme.

Discussion

This study utilised a three-round Delphi methodwith a purposive sample of experienced behavioursupport practitioners to assess the content validityof the BSP-QEII. Validation was sought with spe-cific reference to the use of the BSP-QEII to assessthe quality of BSPs for adults with ID in commu-nity based accommodation and day-support set-

tings. Based on work in the USA (Cook et al. 2007;Kraemer et al. 2008), and preliminary evidencefrom a pilot study in Australia (Webber et al.2011b), it was predicted that given the criteria ofthe BSP-QEII is based upon best practice asderived from the research literature (i.e. it hasestablished face validity) there would be highendorsement of these concepts by experiencedpractitioners.

Round One of the study revealed that partici-pants’ responses concerning possible quality indica-tors for BSPs could generally be referenced withinthe 12 categories of the BSP-QEII. Here it shouldbe noted that we intentionally chose not to simplyask the expert practitioners to make direct ratingson the 12 BSP-QEII items at Round One, to avoidtautological endorsement of items that already had

Table 1 The allocation of 97 comments to the 12 BSP-QEII categories and the two additional categories

BSP-QEII categories

Number ofcommentsallocated(% of 97)

A. Behaviour of concern stated in a way that is observable and measurable 6.20B. Predictors/triggers of behaviour are described in detail 9.28C. Analysis (explanation) of what supports the problem behaviour is logically related to the identified predictors/

triggers10.30

D. Environmental changes (strategies) are logically related to what supports the problem behaviour 5.15E. Function of behaviour is explained in terms of what the person needs or gets; rejects or escapes; protests or

avoids3.10

F. Replacement behaviour (a positive alternative to the BoC which serves the same function) is identified forteaching

3.10

G. Teaching strategies for replacement behaviours are outlined in detail; i.e. how replacement behaviours will betaught

7.22

H. Reinforcers are described to encourage the use of replacement behaviours and reward the non-use of BoC 3.10I. Reactive strategies for managing BoC safely are described 6.20J. Goals and objectives for behaviour change are described; i.e. increase in use of replacement behaviours (positive

alternatives to BoC)5.15

K. Team co-ordination is described in terms of what roles people perform, who is responsible for particular tasksand by when

10.30

L. Communication about what information is to be recorded and how it is to be circulated 5.15

Additional categories

M. Background to the person including their personal history, strengths, preferences, support needs and diagnosesetc.

9.30

N. Contemporary Philosophy of service provision to people with disabilities is reflected in the plan in terms oflanguage used; issues addressed and lay out adopted

16.50

BoC, behaviour of concern; BSP-QEII, Behaviour Support Plan Quality Evaluation Guide II.

6Journal of Intellectual Disability Research

K. McVilly et al. • BSP-QEII validity for adult services

© 2012 The Authors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Table 2 Individual comments endorsed by respondents in round two as being essential to a quality behaviour support plan

Participant comments

% ofparticipantsprovidingendorsement

Behaviour of concernDescription of problem behaviour (observable and measurable) 80.00High rate times of occurrence 33.33Clear description of behaviours to be increased and decreased 60.00The impact of BoC on the person and others and how these affect QoL 40.00Data around frequency, intensity and duration not just anecdotal 46.70Any warning of build-up 40.00

PredictorsClear definition of predictors of behaviour (key indicators) 60.00History of BoC 33.33Things staff should avoid/not do when around the client 40.00Health/medical/psychiatric concerns 40.00Side effects of medications 40.00Current skills (what is client good at and what they have difficulty with) 40.00Communication skills 46.70Sensory stimulation 46.70Antecedents and functions of BoC 46.70

Analysis of what supports behaviourBehaviour recordings (settings, triggers, results) 40.00Observation (where appropriate and feasible) 20.00Motivational analysis (likes and dislikes, preferred activities) 26.70Functional behavioural analysis 53.33Understanding of why BoC occurs 60.00Concise inclusion of historical factors relating to BoC, i.e. trauma engagement style that works/exacerbates,

any schemas relating to BoC26.70

Understand why BoC – what are the reasons? 46.70Medical status 33.33Medications and side effects 33.33Hypothesis on function of BoC 53.33

Environmental structureShorts term change strategies 40.00Environmental factors that can be changed to decease BoC (long term) 60.00Change environment to increase choice making 60.00Prevention of BoC 60.00Details persons programme 40.00

Function of behaviourPurpose and function of the behaviour 66.70Why the behaviours are occurring in terms of what the person needs or gets; rejects or escapes; protests

or avoids46.70

Understanding the needs and behaviours of the person 46.70Replacement behaviours

Attempt and teach functionally equivalent behaviour 40.00Clear links between function of behaviour and strategy that meets the need 46.70What supports can be used so client will not have to use BoC and can use positive alternatives 46.70

Teaching strategiesLanguage understood by the client 53.33Positive programming 46.70Things the staff can do to increase the clients support 40.00Skills development (e.g. relaxation, communication, identify/monitor emotion) 53.33What the plan is to decrease restrictive procedures 33.33Include teaching strategies 40.00Clear succinct management and ideas to teach other ways to communicate 40.00

ReinforcersShort term strategies (rewards) 40.00Engage client in an activity that they enjoy 46.70Incentive programmes 33.33

Reactive strategiesReactive strategies on a continuum from least restrictive to most restrictive 60.00Consideration of persons human rights in utilising restrictive practice 60.00Clearly listing any restrictive practices and interventions and why these are necessary 53.33

7Journal of Intellectual Disability Research

K. McVilly et al. • BSP-QEII validity for adult services

© 2012 The Authors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Table 2 Continued

Participant comments

% ofparticipantsprovidingendorsement

Evaluation of proactive and restrictive intervention included 53.33Clear-concise info about restrictive interventions 46.70Safety of person and other 53.33

Goals and objectivesPerson goals/what the person want to achieve in their life 40.00Evidence the plan works 46.70Realistic goals within achievable time and resources 46.70Demonstration that ultimate goal in reduction of BoC and increase in QoL or person and their support 53.33What the plan is to decrease restrictive procedures 46.70

Team co-ordinationOngoing monitoring of BoC 60.00Monitoring of implementation of strategy or access to enjoyed activity 46.70Consultation with all involved parties (stakeholders) and multiple perspectives 66.70Maintained and updated appropriately 66.70Client/resident should have input into strategies so they feel some responsibility and want to take

some ownership46.70

Evidence of collaborative approach to development 40.00Endorsed by experienced practitioner (signed off) 33.33Action plan (who does what, when etc) 60.00Authorisation, e.g.Authorised Programme Officer 66.70Consent, e.g. client or guardian 60.00

CommunicationRecommendations/referrals to other relevant professional such as OT, speech etc. 46.70Evidence of review dates 60.00Monitoring progress and communication between stakeholders 40.00Information sources, e.g. people consulted, reports used to inform plan 46.70List of service providers/agencies 40.00

Contemporary philosophyClear to understand/plain English/no jargon 60.00Ease of implementation 40.00Concise – not too wordy – one/two page summary 33.33Gives a good balanced, non judgemental view of the client 40.00Person centred 60.00Clients likes and dislikes 40.00Politically correct language, e.g. not labelling or judging 60.00Positively focused not just a reactive strategy 60.00Useable strategies for staff/practical that work; social validity 46.70Demonstrating understanding of what constitutes a BoC and how this may differ from an ‘annoying’,

challenging or age typical behaviour46.70

Evidence based 53.33Supports system change 33.33Flexibility 26.70Office of the Senior Practitioner related pages of behaviour support plan should be omitted from working

document in unit as it only serves as a distracter to staff46.70

Short sharp direct procedure to mange BoC 20.00Sympathetic 20.00

BackgroundPersonal history 46.70Family background 40.00Person’s disability/diagnosis 46.70Medical history 40.00Skills (strengths) and support needs 60.00Cognitive ability and limitations 46.70Communication ability & support needs 60.00Sensory ability and support needs 46.70Personality (preferences, style, likes, dislikes, long/short fuse, etc.) 40.00

BoC, behaviour of concern; QoL, quality of life.

8Journal of Intellectual Disability Research

K. McVilly et al. • BSP-QEII validity for adult services

© 2012 The Authors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

face validity in the research literature. However, thedeductive content analysis revealed two additionalcategories that could be considered as important forevaluating a quality BSP: background information (onthe client) and contemporary philosophy (of serviceprovision). Generally, the comments made by par-ticipants were consistent with the principles andpractices associated with PBS (Carr et al. 1999,2002). Among those items that were most fre-quently commented on as important for inclusionin a quality plan were the need to objectively definethe problem behaviour and to conduct a systematicanalysis of what supports the continuation of theidentified problem behaviour.

The issues that, while raised by participants,were subject to relatively few comments were theuse of reinforcers, understanding the function of behav-iour, environmental changes and teaching replacementbehaviours. Consistent with the research literature,each of these issues could be considered vital to

the successful implementation of a BSP. The factthat experienced practitioners did not highlightthese aspects of behaviour support to a greaterextent is surprising, and warrants further investiga-tion. Failure to include, or at least consider suchissues in a BSP could jeopardise the effectivenessof that plan. The current data cannot explain whythese issues were not more highly endorsed.However, in contrast to the practitioners involvedin the development of the original BSP-QEIIitems, practitioners in the current study were notby profession educators. Although experiencedbehaviour support practitioners for adults, it couldbe that their training had neither emphasised theimportance of, nor equipped them to teachreplacement behaviours, or to take into accountand control the antecedents to problem behaviour.These findings suggest the need for furtherresearch into the congruence between the trainingcurriculum used to prepare practitioners for adult

Table 3 Round Two: average ratings of importance for the quality criteria, as given by expert participants

Categories Mean SD Median

BSP-QEII categoriesA. Behaviour of concern stated in a way that is observable and measurable 9.71 0.61 10B. Predictors/triggers of behaviour are described in detail 9.64 0.63 10C. Analysis (explanation) of what supports the problem behaviour is logically related to

the identified predictors/triggers9.57 0.76 10

D. Environmental changes (strategies) are logically related to what supports the problem behaviour 8.71 2.67 10E. Function of behaviour is explained in terms of what the person needs or gets; rejects or

escapes; protests or avoids9.57 0.65 10

F. Replacement behaviour (a positive alternative to the BoC which serves the same function) isidentified for teaching

8.21 2.64 8.5

G. Teaching strategies for replacement behaviours are outlined in detail; i.e. how replacementbehaviours will be taught

8.00 3.00 9

H. Reinforcers are described to encourage the use of replacement behaviours and rewardthe non-use of BoC

6.93 3.05 7.5

I. Reactive strategies for managing BoC safely are described 7.93 2.70 8.5J. Goals and objectives for behaviour change are described; i.e. increase in use of replacement

behaviours (positive alternatives to BoC)8.71 1.54 9

K. Team co-ordination is described in terms of what roles people perform, who is responsiblefor particular tasks and by when

8.14 2.07 9

L. Communication about what information is to be recorded and how it is to be circulated 7.46 2.27 8Additional categories

M. Background to the person including their personal history, strengths, preferences, supportneeds and diagnoses etc.

8.07 2.13 8.5

N. Contemporary Philosophy of service provision to people with disabilities is reflected inthe plan in terms of language used; issues addressed and lay out adopted

8.00 1.84 8

BoC, behaviour of concern; BSP-QEII, Behaviour Support Plan Quality Evaluation Guide II.

9Journal of Intellectual Disability Research

K. McVilly et al. • BSP-QEII validity for adult services

© 2012 The Authors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

services and what research has demonstrated to bethe essential components of effective practice.

Round Two affirmed the allocation by theresearchers of the participants’ comments fromRound One to the 14 categories. While some sug-gestions were made for re-allocation, there was noclear consensus that would have warranted anyre-allocation. On average, participants ranked allBSP-QEII items as being very important for inclu-sion in a BSP. They also affirmed the two additionalcategories which had emerged from the analysis ofthe Round One data. These results suggest theBSP-QEII (with the possible addition of the twoadditional items) to be a valid measure of qualitywhen reviewing BSPs developed for adults with IDsupported in community-based housing and day-support settings. This is an important findingbecause, apart from preliminary work by Webberet al. (2011b), previous research has only considered

the application of the BSP-QEII to plans developedfor children in school settings.

The results from Round Three affirmed theresults from Round Two, that the items that wereendorsed by at least 60% of respondents as essentialto a quality BSP were again rated on average asvery important. The item with the highest level ofendorsement related to the need for plans to clearlyidentify the ‘purpose and function of the behav-iour’. The item with the lowest average level ofendorsement, although still within the range indi-cating it was very important, was the need for plansto document the ‘authorisation’ of procedures.However, not all of the quality domains were repre-sented by way of comments in Round Three. Thequality domains not represented in the final roundby comments from Round Two were: replacementor alternative behaviours to be taught; teachingstrategies, reinforcers, and goals and objectives for

Table 4 Round Three: mean, median and standard deviation of participant responses

Quality domain Participant comments Mean SD Median

Behaviour of concern Description of problem behaviour (observable and measurable) 9.85 0.37 10Clear description of behaviours to be increased and decreased 9.62 1.02 10

Predictors Clear definition of predictors of behaviour (key indicator) 9.69 0.62 10Analysis of what supports

behaviourUnderstanding of why BoC occurs 9.73 0.60 10

Environmental structure Environmental factors that can be changed to decease BoC (long term) 9.58 1.10 10Change environment to increase choice making 9.12 2.43 10Prevention of behaviour of concern 9.60 0.74 10

Function of behaviour Purpose and function of the behaviour 10.00 0 10Reactive strategies Reactive strategies on a continuum from least restrictive to most

restrictive8.96 1.70 10

Consideration of persons human rights in utilising restrictive practice 9.69 0.62 10Team co-ordination Ongoing monitoring of BoC 9.27 1.31 10

Consultation with all involved parties (stakeholders) andmultiple perspectives

9.19 1.50 10

Maintained and updated appropriately 9.08 1.60 10Action plan (who does what, when etc.) 9.20 1.61 10Authorisation 8.88 1.75 10Consent, e.g. client or guardian 9.00 2.30 10

Communication Evidence of review dates 9.04 2.00 10Contemporary practice Clear to understand/plain English/no jargon 9.19 1.70 10

Person centred 9.46 1.14 10Politically correct language, e.g. not labelling or judging 9.00 1.41 9.5Positively focused not just a reactive strategy 9.73 1.80 10

Background Skills (strengths) and support needs 9.60 0.63 10Communication ability & support needs 9.60 0.63 10

BoC, behaviour of concern.

10Journal of Intellectual Disability Research

K. McVilly et al. • BSP-QEII validity for adult services

© 2012 The Authors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

the intervention programme. These areas are notwell covered in either certificate level disabilitycourses or undergraduate psychology coursesoffered in Australia. It could be that these areas arenot given sufficient emphasis in policy and profes-sional development activities. It is also possible thatpractitioners do not view these areas as appropriatefor or well understood by disability supportworkers, and therefore do not include them in plansthat they expect this workforce to implement. Giventheir potential importance to successful outcomesfor client programmes, why these issues might notbe of such concern to practitioners warrants furtherinvestigation.

The Delphi method proved both useful and effec-tive for the current study in determining thecontent validity of the BSP-QEII in a jurisdictionoutside of the USA, and for its application in set-tings outside of schools. It affirmed the preliminaryfindings of Webber et al. (2011b). Furthermore, itenabled new data to be generated concerning whatcomprises a quality BSP, and for practitioner opin-ions to be compared with an existing theoreticalframework purported to represent best practice inbehaviour support planning.

The samples of practitioners who responded wererepresentative of those persons involved in thedevelopment and review of BSPs for adults with IDin community-based accommodation and day-support services. The analyses at Round One sug-gested that data saturation within this sample hadbeen reached, based on the number of duplicateand parallel comments reported (amounting toapproximately 65% of all comments). Furthermore,all three rounds provided consistent results,whereby each round supported the previousfindings.

Policy makers and practitioners regularly seekadvice on what constitutes good practice and howservices, such as the provision of behaviour supportcould be evaluated. The current findings add to theliterature by making explicit those factors valued bypractitioners working in adult settings. A particularfeature of this study is that it used expert opinion toestablish generic best practice criteria and thenused these comments to garner validity of the BSP-QEII criteria. This approach was in contrast to thatof Horner et al. (2000) which provided respondentswith a list of what the authors believed to best prac-

tice criteria in the first instance. The approachadopted in the current study recognised the partici-pants to be experts in their own right, and com-menced the investigative process without presentingany a priori assertions about what constituted goodpractice. These, in the form of the BSP-QEIIdomains, were not introduced until Round Two.

There were however, some limitations to thecurrent research. The participants were generallyprofessional staff working mainly in governmentservices (government services comprise approxi-mately 50% of disability staff working in Victoria).Future research could include a broader expertgroup, incorporating private practitioners and directsupport staff. The opinions of direct support staffcould be very useful, especially given the fact thatthe majority of BSPs are designed by these staff.The findings from such a study would potentiallyshow what direct support staff value, know andneed to know in order to successfully implement aBSP, both in terms of the content and structure ofthese plans. At the time of conducting the study,the BSP-QEII was restricted in its use to a smallgroup of staff in the central office of the Depart-ment of Human Services. However, a small numberof practitioners involved in the current study mighthave had some limited prior exposure to the BSP-QEII. Here though it is unlikely that any suchexposure would have contributed any significantbias to the overall results. Finally, the initial alloca-tion of participant comments to the various catego-ries was undertaken by the research team, and thiscould conceivably have incorporated some unin-tended bias. However, accepted procedures fordeductive content analysis and consensus coding wereemployed, and further independent validation of theallocation was sought from participants in RoundTwo (i.e. recognised member checking procedures).Here though, future studies could be strengthenedif an independent panel were used for the contentanalysis and coding.

Overall, this study lends support to the use of theBSP-QEII as an acceptable best-practice frameworkfor the education and training of practitionersresponsible for the development and implementa-tion of BSPs. Furthermore, it affirms its validity asa tool for use in programme review and qualityassurance. Importantly, these findings suggest thatthe principles underpinning the BSP-QEII and the

11Journal of Intellectual Disability Research

K. McVilly et al. • BSP-QEII validity for adult services

© 2012 The Authors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

criteria comprising the tool, although originallydeveloped to support teachers planning supports forchildren in schools, are potentially equally appli-cable for use by practitioners in community-basedservices for adults with ID. This study also raisesquestions as to why some practitioners seem notso concerned about a number of issues, alreadyestablished in the research literature as importantto effecting behaviour change, and which havepotential to influence the quality of their BSPs andoutcomes in clinical practice.

With established validity for use in the assess-ment of BSPs devised for adults with ID, futureresearch needs to investigate the use of the BSP-QEII for both the auditing of service quality and asan educational framework in adult services. Fur-thermore, research could investigate different clientoutcomes that might arise from BSPs of varyingquality, and which emphasise different facets ofquality. It would also be feasible to use the BSP-QEII to investigate the effects of different servicepolicies, administrative protocols and educationalstrategies on the quality of BSPs and their associ-ated client outcomes. Such studies could be con-ducted as cross-sectional designs, incorporatingcomparisons between services and jurisdictions atparticular points in time, as well as longitudinaldesigns evaluating the impact of changes in policyand procedures over time on the quality of BSPsand, importantly, associated client outcomes.

References

Allen D. (ed.) (2008) Ethical Approaches to Physical Inter-ventions, Vol. II. BILD, Kidderminister.

Allen D., James W., Evans J., Hawkins S. & Jenkins R.(2005) Positive behavioural support: definition, currentstatus and future directions. Tizard Learning DisabilityReview 10, 4–11.

Bird F. L. & Luiselli J. K. (2000) Positive behavioralsupport of adults with developmental disabilities: assess-ment of long-term adjustment and habilitation followingrestrictive treatment histories. Journal of BehaviorTherapy and Experimental Psychiatry 31, 5–19.

Borthwick-Duffy S. (1996) Evaluation and measurementof quality of life: special considerations for personswith mental retardation. In: Quality of Life, Vol. 1 (ed.R. Schalock), pp. 89–100. American Association onMental Retardation, Washington, DC.

Brown R. (1997) Quality of Life for People with Disabilities:Models, Research and Practice. Stanley Thornes,Cheltenham.

Browning-Wright D., Saren D. & Mayer G. R. (2003) Thebehaviour support plan-quality evaluation guide. Avail-able at: http://www.pent.ca.gov (retrieved 1 December2011).

Carr E., Dunlap G., Horner R., Koegel R., Turnbull A.,Sailor W. et al. (2002) Positive behavior support: evolu-tion of an applied science. Journal of Positive BehaviorInterventions 4, 4.

Carr E. G., Horner R. H., Turnball A. P., Marquis J. G.,McLaughlin D. M., McAtee M. L. et al. (1999) PositiveBehavior Support for People with Developmental Disabili-ties: A Research Synthesis. American Association onMental Retardation, Washington, DC.

Cook C., Crews S., Wright D., Mayer G., Gale B.,Kraemer B. et al. (2007) Establishing and evaluating thesubstantive adequacy of positive behavioral supportplans. Journal of Behavioral Education 16, 191–206.

Cook C. R., Mayer G. R., Browning-Wright D., KraemerB., Wallace M. D., Dart E. et al. (2012) Exploring thelink among behavior intervention plans, treatment integ-rity, and student outcomes under natural educationalconditions. The Journal of Special Education 46, 3–16.

Emerson E. & Einfeld S. (2011) Challenging Behaviour,3rd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

French P., Chan J. & Carracher R. (2010) Realisinghuman rights in clinical practice and service delivery topersons with cognitive impairment who engage inbehaviours of concern. Psychiatry, Psychology & Law 17,245–72.

Groth-Marnat G. (2009) Handbook of Psychological Assess-ment, 5th edn. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ.

Horner R. H., Sugai G., Todd A. W. & Lewis-Palmer T.(2000) Elements of behavior support plans: a technicalbrief. Exceptionality: A Special Education Journal 8, 205–15.

Johnston J., Foxx R., Jacobson J., Green G. & Mulick J.(2006) Positive behavior support and applied behavioranalysis. The Behavior Analyst 29, 51.

Kraemer B. R., Cook C. R., Browning-Wright D., MayerG. R. & Wallace M. D. (2008) Effects of training onthe use of the behavior support plan quality evalutionguide with autism educators. Journal of Positive BehaviorInterventions 10, 179–89.

Krippendorff K. (2004) Content Analysis: An Introductionto Its Methodology, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Inc,Thousand Oaks, CA.

Lowe K., Allen D., Brophy S. & Moore K. (2005) Themanagement and treatment of challenging behaviours.Tizard Learning Disability Review 10, 34.

McVilly K. (2007) Positive Behaviour Support for Peoplewith Intelelctual Disabilities: Evidence-Based Practice

12Journal of Intellectual Disability Research

K. McVilly et al. • BSP-QEII validity for adult services

© 2012 The Authors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Promoting Quality of Life. Australasian Society for theStudy of Intellectual Disability, Melbourne.

McVilly K. (2009) Physical Restraint in Disability Services:Current Practices, Contemporary Concerns, and FutureDirections. Department of Human Services, Melbourne,Vic.

McVilly K., Webber L., Paris M. & Sharp G. (2012) Reli-ability and utility of the Behaviour Support Plan QualityEvaluation tool (BSP-QEII) for auditing and qualitydevelopment in services for adults with intellectual dis-ability and challenging behaviour. Journal of IntellectualDisability Research (in press).

Mansell J. (2006) Deinstitutionalisation and communityliving: progress, problems and priorities. Journal of Intel-lectual and Developmental Disability 31, 65–76.

Mullen P. (2003) Delphi: myths and reality. Journal ofHealth Organization and Management 17, 37–52.

Phillips L., Wilson L. & Wilson E. (2010) Assessingbehaviour support plans for people with intellectual dis-ability before and after the Victorian Disability Act2006. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability35, 9–13.

Stancliffe R. & Lakin C. (2005) Costs and Outcomes ofCommunity Services for People with Intellectual Disabilities.Brookes Publishing, Baltimore, MD.

Sugai G., Horner R., Dunlap G., Hieneman M., Lewis T.,Nelson C. et al. (2000) Applying positive behaviorsupport and functional behavioral assessment inschools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions 2, 131.

Webber L., McVilly K., Stevenson E. & Chan J. (2010)The use of restrictive interventions in Victoria, Australia:population data for 2007–2008. Journal of Intellectualand Developmental Disability 35, 199–206.

Webber L., McVilly K., Fester T. & Chan J. (2011a)Factors influencing quality of behaviour support plansand the impact of plan quality of on restrictive interven-tion use. International Journal of Positive BehaviouralSupport 1, 24–31.

Webber L. S., McVilly K., Fester T. & Zazelis T. (2011b)Assessing behaviour support plans for Australian adultswith intellectual disability using the ‘Behavior SupportPlan Quality Evaluation II’ (BSP-QE II). Journal ofIntellectual and Developmental Disability 36, 1–5.

Accepted 1 July 2012

13Journal of Intellectual Disability Research

K. McVilly et al. • BSP-QEII validity for adult services

© 2012 The Authors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd