The child and adolescent psychiatry trials network (CAPTN): infrastructure development and lessons...

-

Upload

georgetown -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of The child and adolescent psychiatry trials network (CAPTN): infrastructure development and lessons...

BioMed Central

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health

ss

Open AcceReviewThe child and adolescent psychiatry trials network (CAPTN): infrastructure development and lessons learnedMark Shapiro2, Susan G Silva1,2, Scott Compton1, Allan Chrisman1, Joseph DeVeaugh-Geiss1,2, Alfiee Breland-Noble1, Douglas Kondo1, Jerry Kirchner2 and John S March*1,2Address: 1Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA and 2Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA

Email: Mark Shapiro* - [email protected]; Susan G Silva - [email protected]; Scott Compton - [email protected]; Allan Chrisman - [email protected]; Joseph DeVeaugh-Geiss - [email protected]; Alfiee Breland-Noble - [email protected]; Douglas Kondo - [email protected]; Jerry Kirchner - [email protected]; John S March - [email protected]

* Corresponding author

AbstractBackground: In 2003, the National Institute of Mental Health funded the Child and Adolescent PsychiatryTrials Network (CAPTN) under the Advanced Center for Services and Intervention Research (ACSIR)mechanism. At the time, CAPTN was believed to be both a highly innovative undertaking and a highlyspeculative one. One reviewer even suggested that CAPTN was "unlikely to succeed, but would be avaluable learning experience for the field."

Objective: To describe valuable lessons learned in building a clinical research network in pediatricpsychiatry, including innovations intended to decrease barriers to research participation.

Methods: The CAPTN Team has completed construction of the CAPTN network infrastructure,conducted a large, multi-center psychometric study of a novel adverse event reporting tool, and initiateda large antidepressant safety registry and linked pharmacogenomic study focused on severe adverseevents. Specific challenges overcome included establishing structures for network organization andgovernance; recruiting over 150 active CAPTN participants and 15 child psychiatry training programs;developing and implementing procedures for site contracts, regulatory compliance, indemnification andmalpractice coverage, human subjects protection training and IRB approval; and constructing an innovativeelectronic casa report form (eCRF) running on a web-based electronic data capture system; and, finally,establishing procedures for audit trail oversight requirements put forward by, among others, the Food andDrug Administration (FDA).

Conclusion: Given stable funding for network construction and maintenance, our experiencedemonstrates that judicious use of web-based technologies for profiling investigators, investigator training,and capturing clinical trials data, when coupled to innovative approaches to network governance, datamanagement and site management, can reduce the costs and burden and improve the feasibility ofincorporating clinical research into routine clinical practice. Having successfully achieved its initial aim ofconstructing a network infrastructure, CAPTN is now a capable platform for large safety registries,pharmacogenetic studies, and randomized practical clinical trials in pediatric psychiatry.

Published: 25 March 2009

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2009, 3:12 doi:10.1186/1753-2000-3-12

Received: 25 September 2008Accepted: 25 March 2009

This article is available from: http://www.capmh.com/content/3/1/12

© 2009 Shapiro et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Page 1 of 13(page number not for citation purposes)

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2009, 3:12 http://www.capmh.com/content/3/1/12

ReviewClinical research networks are envisioned in the NIHroadmap as a means to reduce the costs associated withlaunching multi-center studies while increasing patientand physician participation in clinical research, whichtogether should accelerate the pace of medical discovery[1,2]. By clinical trials network we mean a clinical trialcoordinating center and a group of clinical trials sites thattogether are capable of conducting multiple and/orsequential clinical trials and safety registries that whereappropriate smooth the progress of biomarker discovery.The Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Trials Network(CAPTN) is among the largest and most sophisticated ofseventy-six clinical research networks targeting childrenand adolescents [3]. The stated mission of CAPTN is toimprove the care of children and adolescents with mentalillness through innovative clinical research. To accom-plish this mission and expand the evidence base in pedi-atric psychopharmacology, CAPTN seeks to conductpractical clinical trials (PCTs) that evaluate the benefitsand harms of widely-used but under-studied medicationswhen conducting such a study that would then serve animportant public health need.

In late 2003, we initiated a partnership between the DukeClinical Research Institute and the American Academy ofChild and Adolescent Psychiatry to develop CAPTN as a"proof of concept" PCT network, the first of its kind inpsychiatry, adult or pediatric. Funding for CAPTN camefrom the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)through the Advanced Center for Services and Interven-tion Research (P30) grant mechanism. Since then, CAPTNhas conducted one multi-center research study focused ondeveloping and validating a novel drug adverse eventsdetection tool, the Pediatric Adverse Event Rating Scale(PAERS), and is in the process of conducting two linkedmulti-national studies focused on (1) antidepressantsafety and the pharmacogenetics of antidepressantresponse and (2) a randomized controlled trial of newerversus older treatments for ADHD. The AntidepressantSafety in Kids (ASK: NCT00395213) study is a prospectivelongitudinal cohort "safety registry" study of predictors ofbenefits and adverse events in 500 youth with a depres-sive, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive or eating disorderexposed to an SSRI or SNRI. Running as a substudy withinASK, the Pharmacogenomics of Antidepressant Responsein Children and (PARCA: NCT00516932) study is anested genetic case-control association study evaluatingthe contribution of selected candidate genes as risk factorsfor a suicidal event behavioral activation or their associa-tion. The Newer Versus Older Treatments for ADHD(NOTA) study is an equipoise-stratified randomized con-trolled trials comparing for treatments for ADHD: Methyl-phenidate Transdermal System (Daytrana),Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate (Vyvanse), OROS MPH

(Concerta), and Mixed Amphetamine Salts ExtendedRelease (Adderall XR).

At the point we began to seek NIMH funding, CAPTN wasbelieved to be both a highly innovative undertaking and ahighly speculative one. One reviewer even suggested thatCAPTN was "unlikely to succeed, but would be a valuablelearning experience for the field." In actuality, many les-sons have been learned in the process of moving CAPTNfrom concept to functioning PCT network that are of gen-eral importance for practical clinical trialists and, in par-ticular, for those seeking to create multi-center clinicaltrials networks in pediatric and adult psychiatry. In previ-ous reports we documented the need for PCTs in pediatricpsychopharmacology [4], described common obstacles toconducting PCTs in psychiatry and proposed a set of solu-tions [5], and presented a theoretical rationale for CAPTN[3]. In this article, we specifically focus on infrastructuredevelopment issues (the "hardware") that enables practi-cal clinical trials (the "software") to run on CAPTN.

BackgroundIn the October 3rd, 2003 issue of Science, the Director ofthe National Institutes of Health (NIH), Dr. EliasZerhouni, described a roadmap for clinical research thatincluded three guiding principles believed to be funda-mentally important for improving patient care outcomes[1]: (1) develop partnerships among and better integra-tion between organized patient communities, commu-nity-based physicians, academic researchers, and the NIH,(2) develop new ways to organize how clinical researchinformation is recorded and make greater use of moderninformation technologies, and (3) devise new standardsfor clinical research protocols.

Consistent with the Roadmap initiative, CAPTN is prem-ised on the belief that an expansion of partnershipsamong stakeholders – academia, pharma, the FDA, theNIH and patient advocacy groups – will facilitate a public-health oriented research agenda that is based on the med-ical needs of patients and the informational needs of phy-sicians and healthcare policy-makers making patient caredecisions [4].

Almost two decades ago, Sir Richard Peto, who coined theterm large, simple trial [6], proposed that treatment out-come studies should have sufficient power to identifymodest clinically relevant effects, employ randomizationto protect against bias, and be simple enough to make par-ticipation by patients and providers reasonable [7]. Morerecently, Sean Tunis at the Center for Medical Services(CMS) described the defining features of an effectivenesstrial as comparing clinically important interventions, adiverse population of study participants representative ofclinical practice, a heterogeneous practice setting also rep-

Page 2 of 13(page number not for citation purposes)

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2009, 3:12 http://www.capmh.com/content/3/1/12

resentative of clinical practice, and a broad range of clini-cally relevant health outcomes [8]. Building on Peto andTunis, we recently made the case for practical clinical trialsin psychiatry [5]. Consistent with the proposed PCTframework, we formatted the network infrastructure sothat PCTs conducted on CAPTN would be characterizedby eight defining principles: (1) Questions must be sim-ple, clinically relevant, and of substantial public healthimportance; (2) PCTs are performed in clinical practicesettings; (3) study power is sufficient to identify small-to-moderate effects; (4) treatments should be in clinicalequipoise; (5) treatment conditions should be randomlyassigned to protect against bias; (6) outcome measuresshould be simple and clinically relevant; (7) treatmentsand assessments should enact a best practice standard ofcare; and (8), subject and investigator burden associatedwith research should be minimized.

While these characteristics are widely applicable to PCTsin general and, hence, are held in common by practicalclinical trialists independent of discipline [9,10], some ofthe challenges that we faced in developing a PCT networkin pediatric psychiatry are specific to the field of pediatricpsychiatry itself. Both field-specific and more generalchallenges provide instructive lessons for those seeking toinstantiate the PCT model in that they provide insight intothe factors that may inhibit or, conversely, facilitate net-work creation.

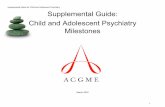

Network organization and governanceFigure 1 outlines the CAPTN organizational structure,including trial leadership, governance and coordination,sponsors, advisory boards, partners, network sites, infra-structure capabilities and projects.

Executive CommitteeAdopting a proper network governance structure is criti-cally important to the overall success of a multicenter clin-ical trials network. Thus, the first step in creating acollaborative research network, such as CAPTN, was todevise a system for governing the network and enlisting acore group of researchers to take on the managerial chal-lenges. In this regard, CAPTN has benefited from its prox-imity to many NIH- and foundation-funded researchnetwork initiatives based at the Duke Clinical ResearchInstitute. As the oldest and largest academic researchorganization (ARO) in existence, the DCRI http://www.dcri.duke.edu employs state-of-the-art operationalcapabilities, including data and site management, biosta-tistics, and safety surveillance, to facilitate the develop-ment, conduct and dissemination of results for NIH andindustry funded randomized controlled trials or safetyregistries. Moreover, the DCRI is a pillar in the DukeTranslational Medicine Institute (DTMI: http://www.dtmi.duke.edu), which is designed to address T1, T2

and T3 translation blocks identified on the NIH Road-map.

Thus, we were able to draw upon significant expertisewhen considering the organizational design of the CAPTNcoordinating center. In every organization, leadershipmust take on the questions of "Who sets the questions oragenda?", "Who has a seat at the table?" and "Where doesthe final authority lie?" Many network exercises failbecause the network leadership reflects either implicit orexplicit strategic agreements among powerful site-basedprincipal investigators who as often as not have little or notrack record of working together that everyone will "havea piece of the pie." Put differently, many clinical trials net-works are (usually covertly) structured to serve the scien-tific and financial interests of the investigators rather thanto meet the mission statement of the network itself. Aclear line of authority is necessary to help insure that net-work members remain stakeholders for the primary mis-sion of the network. Absence of a clear governancestructure devoted to the success of the network as a whole,or a failure in process, including means for reconcilingdisputes, often leads to the formation of subgroups based

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Trials Network (CAPTN)Figure 1Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Trials Network (CAPTN). Proposed organizational structure for CAPTN during the second five years ofNIMH funding. ISAB = internal scientific advisory board; ESAB = externalscientific advisory board; DSMB = data safety and monitoring board; IRB = insti-tutional review board; AACAP = American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; SODBP = Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. Pilot projects are small feasibility studies design to gatherpreliminary data to support developmental studies, which are R34 likeprelimi-nary studies intended to construct trial infrastructure and materialsin preparation for R01-like PCTs, safety registries or biomarker/biosignatureprojects.

Page 3 of 13(page number not for citation purposes)

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2009, 3:12 http://www.capmh.com/content/3/1/12

on self-interests, studies burdened with irrelevant andcostly instruments and procedures, sluggish progress onstudy design and implementation, and poor site andpatient enrollment. In developing CAPTN, we explicitlywanted the network to serve the interests of mentally illchildren and their doctors. We also wanted clear lines ofdecision making in which all the major stakeholders inpediatric psychiatry were represented, and we wanted tomaximize the public health value of every dollar spent onCAPTN.

From the outset, governance was entrusted to a coregroup, the CAPTN Executive Committee that is composedof Duke University faculty, the Project Leader from theDCRI, and representatives from the site management,data management and statistics functional groups. Withweekly meetings, this group provides a forum for bothstrategic decision-making and for overseeing the day-to-day operations of the coordinating center ensuring thatregular progress is made on all activities essential to thefunctioning of the network.

Advisory BoardsAdvising the Executive Committee is a larger group ofstakeholder experts: the CAPTN Steering Committee.Prior to the funding of CAPTN, we solicited commitmentsfrom key stakeholders in the field of child and adolescentpsychiatry. Among these were senior leadership from theAACAP, including representation from both the AACAPCouncil and the AACAP Workgroup on Research, NIMHProgram staff, and a representative from the National Alli-ance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI). In addition, expertsfrom academia were recruited to offer diverse viewpointsincluding child psychiatrists, psychopharmacologists, amedical practice researcher, and a pharmacoepidemiolo-gist, all of whom were based outside of Duke University.After funding for CAPTN was received, a representativefrom the NIMH program office, Dr. Benedetto Vitiello,who consulted to us during the ACSIR application proc-ess, was added as an ex officio member.

The core members of the Steering Committee were sup-plemented with rotating at-large appointments from par-ticipating network members. More than a dozenphysicians responded to our initial request for applicantsto join the CAPTN Steering Committee. Selecting appli-cants for the 2 1/2 year appointments proved to be morechallenging than anticipated. Applicants were all highlyqualified and diverse in the education, research experi-ence, practice setting, and geographic location, amongother factors. Ultimately, the committee selected threeapplicants who were primarily clinic-based practitionersbut each of whom had some prior research exposure. Thepurpose of this decision was to provide a reality check forthe Steering Committee in terms of the additional bur-

dens that we, as researchers, were asking of busy clini-cians. While the stated purpose of the Steering Committeewas to serve an active if consulting role in managing thenetwork and collaborating on CAPTN trials, the focus ondeveloping and refining the CAPTN infrastructure (a proc-ess largely internal to the DCRI) and the fact that the SCmembers were for the most part too busy to take otherthan a distant advisory role in CAPTN meant that the SCbecame in practice more like a traditional external scien-tific advisory board. Accordingly, going forward, the SCmodel will be supplanted with a smaller advisory ExternalScientific Advisory Board.

Our third group of advisors was an internal ScientificAdvisory Board. This group was composed of advisors, allfrom Duke University, in fields ranging from ethics, law,regulation, statistics, medicine, and clinical research. Thepurpose of this body was to help the CAPTN ExecutiveCommittee overcome obstacles or barriers to research thatemerged from either internal or external factors. Amongthe areas that this group advised on were related to struc-turing contracts, funding for research participation, Feder-alwide assurances, and ethical oversight for thoseunaffiliated with an institution with an IRB, bureaucraticinefficiencies within the Duke system, and fitting the mis-sion of the network to the changing regulatory environ-ment. In particular, many of the challenges we faced as apsychiatric network were related to difficulties transport-ing the mega-trials network model from areas of medicinethat take place within facilities with a history of medicalresearch, such as oncology and cardiology, to an area thattakes place largely in small, out-patient practice settings.

Dispute ResolutionIn the rapidly changing landscape of medicine, particu-larly in the area of drug safety research, the governancestructure must accommodate a need for swift dispute res-olution, should such disputes arise. Thus, the PrincipalInvestigator was responsible for bringing consensus to theExecutive Committee. In cases where consensus could notbe reached, the Executive Committee consulted with theSteering Committee. The Scientific Advisory Board wasavailable for consultation about specific challenges orgeneral guidance about factors outside of pediatric psychi-atry that nonetheless impacted the network or its researchaims. To ensure efficient decision-making, the PI retainedfinal authority over decisions, however with escalationand consultation, the Executive Committee was able toreach consensus over major decisions, the most challeng-ing of which was related to the collection and reporting ofSerious Adverse Events (SAEs). This is described below inthe section on AE reporting.

Page 4 of 13(page number not for citation purposes)

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2009, 3:12 http://www.capmh.com/content/3/1/12

CAPTN InvestigatorsRecruitmentFinding clinicians willing and able to participate in clini-cal research has been a challenge in many areas of medi-cine, including child and adolescent psychiatry. Of the20,000 cardiologists in the United States, fewer than 1000(.5%) participate in research. Currently, there are approx-imately 7,000 child and adolescent psychiatrists in theUnited States and, when we began CAPTN in 2003, onlya handful were primarily engaged in clinical research.Thus, the support of the AACAP was critical for our initialand ongoing investigator recruitment strategies. Througha series of surveys, conducted initially at the AACAPannual meetings on paper, and later through the CAPTNweb site, we detected a significant level of interest in clin-ical research among AACAP members: Approximately 300child and adolescent psychiatrists responded to theseearly surveys indicating a interest in clinical researchwithin the field, but significant uncertainty as to how onemight begin performing clinical research and what addi-tional demands such research would place on clinicians.These surveys were the basis for our initial claim that itwould be feasible to recruit and train approximately 200investigators to join CAPTN and conduct a series of clini-cal trials. This figure (.3%) is well within the range ofresearch participation by members of the American Col-lege of Cardiology, but far smaller than the near 100%participation rate in the Children's Oncology Group,which sees 95% of youth with cancer.

Once CAPTN was funded, we began by contacting therespondents to our initial feasibility surveys. In addition,we reached out through the AACAP to their membershipthrough their web site, email, and at the AACAP AnnualMeeting. We asked those interested to complete an inter-est questionnaire with their contact information and qual-ifications. During this initial phase of investigatorrecruitment, we succeeded in identifying 235 child andadolescent psychiatrists who indicated an interest inCAPTN. Including members associated with residenttraining programs in child and adolescent psychiatry,approximately 150 of these completed the progressionfrom interest to completing a master contract and theCAPTN requirements for human subjects protection. Thisprocess took almost three years for reasons outlinedbelow. We also quickly realized that in a group this large,a handful of people in any given month would need tosuspend their participation due to circumstances. Ulti-mately, in a large research network, a certain amount of"churn" is inevitable. In CAPTN, this turns out to be about10% of the network membership per year either tempo-rarily suspend their participation or permanently do so.Common reasons for this were moves, retirement, andpersonal reasons, such as divorce or family emergencies.This is an important consideration for those constructing

such networks since a steady-state network of 200 investi-gators must recruit and train about twenty new membersper year to sustain itself.

Training ProgramsOther than at a small number of research-oriented aca-demic medical centers, clinical research has not histori-cally been part of a child and adolescent psychiatrists'residency or fellowship training. Indeed, a survey of clini-cal trials publications in pediatric psychopharmacologyreveals a core group of fewer than 25 principal investiga-tors located mostly at prominent academic centers that areresponsible for the majority of recent pediatric psychop-harmacology literature. Fortunately, what we noticedfrom our initial recruitment efforts was that the majorityof our members were coming from outside of these majoracademic medical centers. While this was consistent withour goal of recruiting primarily clinicians, rather thanresearchers, our long-term network growth strategy wasbased on reaching out to residency and fellowship train-ing programs. Our intention was to interest trainees inresearch during their fellowship with the hope that theywould choose to continue conducting CAPTN clinical tri-als after completing their training.

Dr. Allan Chrisman, Child and Adolescent PsychiatryTraining Director at Duke, and a member of CAPTN'sExecutive Committee, developed a training program spe-cific initiative to identify and recruit CAPTN members atfacilities with ACGME certified residency training pro-gram. Through his efforts at AADPRT and the AACAPWorkgroup on Training, we signed up fifteen child andadolescent psychiatry training programs, each of whichagreed to engage their trainees in CAPTN research proto-cols. This outreach coincided with an increased emphasison research in the accreditation guidelines for psychiatrytraining programs, and the training we offered was amechanism for many programs to achieve this target. Forresearch networks, partnership with training programs isa critical strategy for ensuring continued growth in net-work membership, but more importantly, trainees staff-ing busy clinics serve as a force multiplier, substantiallyincreasing the capacity of the research network to enrollpatients.

International MembersInterestingly, while CAPTN was conceived of as a domes-tic (i.e., United States only) undertaking, our early surveysshowed a strong interest among Canadian members of theAACAP. Following discussions with the program officeand an application for Fogarty Center clearance, we pro-ceeded with enrolling Canadian child and adolescent psy-chiatrists and training programs. Although the drugs inuse differ somewhat country-to-country, a multi-nationalexpansion of clinical research networks will be essential

Page 5 of 13(page number not for citation purposes)

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2009, 3:12 http://www.capmh.com/content/3/1/12

for achieving the very large sample sizes that have becomecommon in PCTs in, for example, cardiology. WithinCAPTN, we are actively working to develop systems for abroader expansion into additional countries over the nextfew years.

Regulatory ComplianceOne of the main justifications given for clinical researchnetworks is the perceived savings associated with recruit-ing clinical trial sites once rather than ad hoc each time anew study is conceived or funded. To realize these costsavings for a post-marking drug research network, such asCAPTN, we set out to define a minimum set of require-ments necessary for investigator participation that wouldmeet applicable regulatory requirements. This activity ledto conversations with a wide variety of stakeholderswithin the Duke community, and ultimately, to a numberof investigator and site requirements. The burdens associ-ated with these requirements proved to be a significantbarrier to investigator recruitment and participation.

Site ContractsAmong these requirements was an executed site contract.Clinical trial site contracting has traditionally been per-ceived of as both slow and cumbersome, particularlywhen the contracting offices of major universities areinvolved. Because of the time and difficulty involved withthese negotiations, many in the pharmaceutical and con-tract research industries eschew academic sites that are notconsidered to be opinion leaders within the field. There-fore, we had hoped to simplify the process and, in somerespects, succeeded, but discovered many barriers toresearch that were nearly insurmountable within themodern university architecture.

To participate in CAPTN, all site principal investigatorsmust sign a Master Services Agreement. Ultimately, thisagreement was pared to seven pages in length but wascomplicated by several possible combinations of attach-ments specific to type of facility at which the investigatorworked. Under the MSA-model, future studies are all cov-ered under two-page, study-specific contract addenda.Although we hoped for shorter, simpler contracts, wefound that most investigators found the proposed lan-guage acceptable without modification. However, morelengthy negotiations ensued with other universities. Forexample, Arizona state law now makes all records of stateuniversities part of the public record. For the participationof state universities in Arizona this necessitated specificlanguage to protect the confidentiality of study recordsand meant that the study coordinating center had to markall study-materials sent to the site as "confidential." How-ever, the single largest contractual barrier we encounteredwas the issue of indemnification and medical malpracticeliability insurance.

IndemnificationWhile industry sponsors of clinical research regularlyindemnify clinical researchers for activities related to theperformance of a clinical study, the Federal governmentprovides no such indemnification for clinical trials. ForDuke University's Risk Management office, a large, com-munity-based clinical research network, such as CAPTN,presented a significant potential change in litigation expo-sure. Ultimately, it was decided that for us to proceed, wehad to document the presence of $3 M per incident and$5 M annual aggregate professional liability insurance forall CAPTN investigators. This was coupled with a reviewby Risk Management related to the solvency of the insurerand history of jury awards within each investigator'slocale. While the time involved in collecting and review-ing these documents slowed the contracting process, itturned out that their standards were significantly higherthan what is standard within child and adolescent psychi-atry, where we found that about 90% of practitioners hadcoverage of $1 M per incident and $3 M annual aggregate.We were frequently able to obtain waivers on a case-by-case basis for those with less than the required $3 M/$5 Mcoverage allowing them to participate in those CAPTNstudies that were considered non-interventional or mini-mal risk under 45 CFR 46 Subpart D. This degree of cau-tion is likely to be general for large institutions and thosethat self-insure since widely distributed geographic expo-sure and lesser oversight of extramural researchers in amulti-center setting may affect risk exposure and hence,the costs of re-insurance. Ultimately, we were able to pro-ceed with minimal risk research, but this issue reemergedwhen we began looking to expand CAPTN beyond theUnited States. These experiences are described below inthe section on international research.

Oversight: Institutional Review BoardRegardless of the funding source, clinical research must besubject to the oversight of a duly constituted IRB or equiv-alent body. In the case of CAPTN, the Duke UniversityHealth System IRB agreed to serve as the IRB of record forthose sites without access to a local IRB. The mechanismto allow this is the Unaffiliated Investigator Agreement(UIA), which was provided to those in solo practice whoenrolled in CAPTN. In this arrangement, individual clini-cians agree to operate under the purview of the DUHS IRBwith the UIA provided as an attachment to the MSAdescribed above. However, it was determined that Dukewould not add external institutions to its Multiple ProjectAssurance (MPA); later replaced by a Federalwide Assur-ance or (FWA). Thus, group practices and institutionswithout a local IRB would be required to possess a Feder-alwide Assurance. The FWA is a binding agreement to con-duct clinical research in compliance with the ethicalprinciples outlined in the Belmont Report of 1977 (forthose facilities located in the United States) or equivalent

Page 6 of 13(page number not for citation purposes)

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2009, 3:12 http://www.capmh.com/content/3/1/12

(e.g., the Tri-Council Policy Statement in Canada). Thus,for CAPTN, we helped 21 institutions to complete and filean FWA with the Office of Human Research Protection(OHRP). The FWA includes specific terms which the insti-tution must agree to abide by in order to receive the assur-ance. In addition to identification of a Human ProtectionAdministrator, the facility must adopt written policies andprocedures to ensure compliance with ethical and regula-tory requirements. While CAPTN has helped facilitiesdevelop these procedures, some potential CAPTN partici-pants balked when confronted with the time commitmentnecessary to complete the training and adopt the formalprocedures required.

Regulatory DocumentationIn addition to the contractual demands of research,another significant burden is the collection and mainte-nance of essential regulatory documents. For studies con-ducted under an IND pursuant to 21 CFR 312, thisdocumentation includes a form FDA 1572, investigatorresumes or curricula vitae, and medical licensure for everysite participating in the research. Finally, in psychiatry,and in particular, in child and adolescent psychiatry, useof medications scheduled under the Controlled Sub-stances Act is commonplace (for treatment of AttentionDeficit Hyperactivity Disorder). Since it was highly prob-able that we would conduct studies in this area, we optedto require network members to have prescribing authorityunder the CSA. This is commonly documented by theform DEA 223.

To date, CAPTN studies have not required an IND,although this might be expected in some cases, sincemany, if not most, medications used in this area areapproved for use in adults, but not in children. Therefore,we felt that the collection and maintenance of regulatorydocuments should be sufficient to meet the requirementsof an IND study, following the stipulation of 21 CFR312.53 and ICH 4.1.1 which require that sponsors ofresearch document that clinical investigators are qualifiedto conduct studies of the investigational product. ForCAPTN, this has been defined to mean those physicianswho are licensed in good standing to practice medicineand have completed specialty training in psychiatry andchild and adolescent psychiatry. We documented thiswith information from the American Board of MedicalSpecialties (ABMS) and AACAP, whose databases allow usto verify that our investigators have completed therequired residency training and board certification. How-ever, as an NIH-funded enterprise, CAPTN is also subjectto the requirements of 45 CFR 46.

For federally-funded studies, an NIH format BioSketchtakes the place of curriculum vitae. In addition, humansubjects' protection training and a Federalwide Assurance

(for studies that are more than Minimal Risk under 45CFR 46 Subpart D) are also required. For community sites,the human subjects' protection in research trainingrequirement is typically met with the on-line module enti-tled "Human Participant Protections Education forResearch Teams." This module is available from theNational Cancer Institute through their web site at http://cme.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/learning/humanparticipant-protections.asp. It is important to note that many Institu-tional Review Boards (IRBs) require their own trainingmodules which we allowed as substitutes for this trainingby those operating under a local IRB, if the local IRB wasregistered with OHRP and the institution had an activeFWA. This required training takes approximately an hourto complete on-line and provides a certificate document-ing completion of the training. For a small fee ContinuingMedical Education (CME) credit is available.

Clinical researchers may be audited by any of severalagencies that are empowered to restrict their ability to par-ticipate in clinical research. Among these are the OHRP,NIH Office of Civil Rights, and the FDA's BioResearchMonitoring Program. We require that all members beunrestricted by any of these regulatory agencies withrespect to their ability to participate in human subjects'research.

Managing Investigator BurdenAs these requirements became defined and we receivedfeedback from network members, it became clear to usthat the requirements were excessively burdensome. Sur-veys of those members who completed all requirementsindicated that the time required by investigators to pro-vide documentation that they had fulfilled these require-ments was estimated to be ten to fifteen hours. Note thatthis does not include any training for specific protocols.Ultimately this proved to be a drag on investigator recruit-ment and was complicated by the fact that CAPTN wasn'tbudgeted to cover the time costs of these requirements.

For experienced researchers working in facilities with sup-port infrastructure, such as a clinical research coordinator,ten hours may not seem onerous, but for CAPTN mem-bers, 80% of whom are in private practice, additionalpaperwork of this magnitude was seen as an overwhelm-ing barrier to participation. Consider that, in private prac-tice, and particularly, in solo practices, every hour spenton these activities means unseen patients and an opportu-nity cost to the practice. Child and adolescent psychiatryis a field where the wait to see a physician is six months inmany areas, meaning the time required to meet theserequirements occurred at a loss to patients, too. Recogniz-ing that the burdens were more time-consuming than weanticipated, we discussed the situation with our SteeringCommittee, Scientific Advisory Board, and the program

Page 7 of 13(page number not for citation purposes)

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2009, 3:12 http://www.capmh.com/content/3/1/12

office at the NIMH, and made a decision to offer reim-bursement for the costs of research above the costs of clin-ical care. While we recognize that the costs of this timediffer based on overhead costs in different regions andpractice settings, we settled on reimbursement at $150 perhour. This number was arrived at through both surveysand a consideration of our ability to pay, based on re-budgeting of the network coordinating center's fundsaway from other activities.

As the burden of regulatory and other requirementsbecame clear to us, we recognized that innovative strate-gies to lessen these burdens were imperative. We achievedsubstantial cost savings by automating the collection ofregulatory information and moving this burden frominvestigators to the study coordinating center. Ultimately,the system we developed led to an enormous cost savingsand represents a significant advancement in recruitmentof clinical investigators. This system is described below.

In recent years, an increasing amount of information hasbecome available in electronic format. Although clinicalresearch and medicine in general has lagged other busi-ness in terms of adoption of information technologies,many organizations are actively moving towards elec-tronic records. For CAPTN, we linked our web-basedenrollment survey system to a live database that inte-grated physician licensure information from the Federa-tion of State Medical Boards portal. Using custom scriptsfor each state's web site we were able to quickly automatecollection of licensure information for about 85% of theU.S. population. We combined this with imports of childand adolescent psychiatry training, demographic, andcontract information from the AACAP database, boardcertification information from an automated script for theABMS web site, DEA licensure information from the DEAregistrant database available from the National TechnicalInformation Service (NTIS), and FWA information fromthe OHRP. This system enabled us to quickly documentinvestigator qualifications from reliable and valid infor-mation sources.

When an investigator signs up for CAPTN through ourweb site, we are able to match up the information pro-vided on our short enrollment survey with this compositedatabase to verify that their credentials are current andsufficient for membership in CAPTN. The informationfrom this survey is then merged into the NIH format BioS-ketch and an email with a link to the required HSP train-ing.

While this system, an aggregate of more than sixty live andstatic databases, represents a significant innovation interms of documenting investigator qualifications under21 CFR 312 and ICH 4.1.1, we feel that it may be a starting

point for easing the burdens of research across specialties.Specifically, we envision a similar system operated cen-trally by the NIH or FDA in a manner analogous to FWAand IRB registries currently maintained by OHRP. A cen-tral system, linking qualification databases such as medi-cal licensure, residency training and board certification,and DEA registrant information together with the HSPtraining records database at the NCI and institutionalinformation from OHRP (IRB, FWA) could vastly simplifythe process of documenting investigator qualifications forresearch, and provide a means for centrally trackingresearch participation by oversight bodies within DHHS.A convenient platform for such a project already exists, inpart, through the http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. The bene-fits of joining these systems into a large clinical researchinformation architecture are that investigators would berelieved of providing duplicate regulatory documents foreach trial that they participate in to sponsors who arerequired to collect and process them. This reduced theoverall burden of research and facilitates the work of over-sight agencies and IRBs by allowing real-time tracking ofqualifications and HSP training along with study partici-pation.

Professionalism: Training Clinicians to be Clinical ResearchersA central myth in the field is the belief that being an expertclinician entitles one to do treatment research. Nothingcould be further from the truth. While it is very helpful tohave good clinical skills, the research skills necessary to bea Good Clinical Practice (GCP) compliant clinical trialistor to effectively run a GCP compliant clinical trial site areseparate from the basic skills required for clinical practice.

Accordingly, CAPTN, which by intent recruited investiga-tors without research experience, required us to put inplace a variety of vehicles for terrific clinicians to becometerrific research sites. In addition to the NCI's training ortraining offered by a local IRB, we made research ethicstraining created by Duke University's Trent Center forBioethics, Humanities, and the History of Medicine freelyavailable to all CAPTN investigators. These research ethicstraining modules cover a wide variety of the ethical andscientific aspects of performing human subjects' research.The modules also provide free continuing medical educa-tion (CME) credit. We felt that this was one potential ben-efit of participating to physicians participating in CAPTN.

In addition to HSP training, we partnered with the Com-munications Department at the Duke Clinical ResearchInstitute to offer a ten module series of on-line training inclinical research through the CAPTN web site. This train-ing is based on the clinical research textbook, Lessonsfrom a Horse Named Jim. This textbook was provided freeof charge to all CAPTN investigators after execution of the

Page 8 of 13(page number not for citation purposes)

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2009, 3:12 http://www.capmh.com/content/3/1/12

network MSA. Our aim was to provide both the book as areference and a tool for self-directed training in clinicalresearch. In the first two years that the on-line trainingmodules were available, fewer than a dozen networkmembers completed any of the training modules. Thismay have been due, in part, to the fact that initially CEU,but not CME was available for completing the modules.

In fact, the cost and requirements for obtaining accredita-tion for these modules to provide CME was a barrier forthe coordinating center. We found that working throughthe AACAP, which is an authorized provider of CME, sim-plifies the offer of CME credit for training modules createdby CAPTN. Recently, we have completed modules onUnderstanding in Incorporating Evidence-Based Medicineinto Clinical Practice and Understanding Issues of Diver-sity in Clinical Research and Patient Recruitment. Addi-tional modules are in development.

Cumulatively, CAPTN members were required to com-plete about two hours of training prior to participating inour first clinical research study. This training was deliveredvia the web-based modules, teleconferences, and webcasts. Our experience in the first Network Initiation studysuggests that this training alone is not sufficient for newclinical researchers.

Study MonitoringOne of the main costs, and thus barriers to, expanded clin-ical research within the context of medical practice is thecost of monitoring compliance at clinical sites. ICH 5.18.3requires monitoring of clinical trial sites, but doesn'tdefine a minimal level of monitoring of research studies.Since IRBs are required to review studies at least annually,this has become the minimum standard for monitoring ofclinical research sites. Historically, clinical research moni-tors (CRAs) have traveled to sites to verify source docu-ments, conduct training or retraining, and assesscompliance with ethical and regulatory guidelines. Forour first Network Initiation study, we required internet-based research ethics training and conducted a series ofweb cast protocol training sessions that lasted about onehour each. Coordinating Center personnel contacted sitesseveral times per month using phone, email, and/or fax toanswer questions, collect enrollment information, anddiscuss the conduct of the study. Over the next year, wephysically monitored all sixty-five sites that participatedfocusing on ethical and regulatory compliance. The find-ings of these activities showed a large number of issueswith the performance and documentation of informedconsent at approximately half of PAERS sites.

Since most investigators were research naïve prior to thisstudy, we discovered post hoc that an hour each of ethicsand protocol training was insufficient for most clinicians

with respect to the execution of the informed consentprocess. After working with sites to report these findingsto their IRB, we determined that the available training dida good job of educating clinicians about the regulatoryand ethical aspects of doing human subjects research, butdid not give them a framework for implementing proce-dures to comply with these guidelines. In response, wecreated SOPs to help sites enact procedures that wouldallow them to meet the requirements. In addition, wehave embarked on creating a professionally-produced,web-based interactive training that is scenario-based andmakes extensive use of video. This educational module iscurrently in production and will be completed and placedin the public section of the CAPTN website in Quarter 1 of2010.

Following this study, we surveyed participating investiga-tors and discussed the findings with our Steering Commit-tee. The at-large members were particularly helpfulexplaining to the Steering Committee the specific burdenscreated for doctors when they had to add additional timeto their patient care encounters (for example, for conduct-ing informed consent discussions) or increase their over-all paperwork burden. Indeed, three factors here areparticularly relevant for those attempting to increase par-ticipation in medical research by physicians. First, pres-sure from payers has reduced the amount of time childand adolescent psychiatrists (and other specialists) areable to spend with patients. Aggravating this is the severeshortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists in NorthAmerica. Our surveys of participants and potential partic-ipants indicated that their initial encounters with treat-ment-seeking children and families lasted a median ofone hour. For medication management visits, the mediantime spent with a patient was twenty-five minutes. CAPTNreimburses for the cost of research above the cost of rou-tine clinical care. After conducting our first study, wefound that it took an average of 45 minutes time to con-duct the informed consent process with the family,approximately thirty minutes to complete the researchportion of the clinical interview, and twenty-to-thirtyminutes to complete the case report forms required forour study. While this is a tiny time allocation relative toefficacy/effectiveness trials like the Treatment for Adoles-cents with Depression (TADS) study[11,12], it is notinconsequential for busy physicians. Hence, for participa-tion in research to be financially neutral for physicians,studies must be budgeted accordingly, and the budget forsite-based payments must be large enough to absorb thesample sizes required in practical clinical trials.

The Data Safety and Monitoring BoardIn addition to field monitoring for regulatory and ethicalcompliance, a Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB)was established as an independent body to periodically

Page 9 of 13(page number not for citation purposes)

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2009, 3:12 http://www.capmh.com/content/3/1/12

evaluate the progress of CAPTN studies. This includes areview of safety data for signals that might warrant modi-fication, suspension, or discontinuation of a particularstudy. In developing a charter for the Board, we madeextensive use of the NIH Policy on Data and Safety Moni-toring, FDA's draft guidance on the establishment andoperations of Clinical Trial Data Monitoring Committees,and the DAMOCLES study group's guidelines. In addi-tion, members of our executive committee drew on theirown experiences chairing or serving on numerousDSMBs/DMCs for NIH and industry.

When recruiting members of this board, the issue of liabil-ity insurance reemerged. Although lawsuits against DSMBmembers are rare, and have not, to our knowledge, beensuccessful, this remains a possibility and a barrier torecruiting qualified candidates. This is specifically since itis recommended that a majority of members be independ-ent of the sponsoring institution (Duke, in our case).Those serving on the board with appointments at Dukewould generally be covered under Duke's insurance butDuke generally does not indemnify independent contrac-tors, such as DSMB members, meaning that the externalmembers should either come from an institution thatwould cover them or they must purchase their own cover-age. As the importance of DSMBs increases, we anticipatemore difficulty in recruiting qualified candidates. To alle-viate this, liability insurance or indemnification should bemade available to those agreeing to serve on these boards.

We required that members of our DSMB submit annualConflict of Interest and Financial Disclosure certificationsmodeled after the policy for such disclosures at Duke. Therequirements for this disclosure stem from 21 CFR 54and, for NIH-funded projects, such as CAPTN, 42 CFR 50.The purpose of these disclosures is to ensure that thoseparticipating in CAPTN research are fully objective.

Based on Duke's policy and the guidance available fromthe NIH, FDA, and International Council of Medical Jour-nal Editors, we crafted a financial disclosure and conflictof interest (COI) policy for the network that is currentlyapplicable to CAPTN publications and CAPTN faculty.Respecting the balance between the ethical and regulatoryneed for full disclosure of competing interests and theadditional burden full disclosure might place on CAPTNinvestigators participating in CAPTN research projects, weare currently considering extending conflict of interestreporting to all CAPTN investigators using the CAPTNpractice profiling tool, the Practice Research Survey.

Study ArchitectureTo realize the efficiencies of a research network, we soughtto develop a standard platform on which to capture clini-cal trial information. This core Case Report Form battery

consisted of basic patient, practice, and diagnostic infor-mation for screening and enrollment, along with a stand-ard treatment-level form that included validated andreliable measures of safety, tolerability, and efficacy.

Diagnostic and Outcomes AssessmentAfter extensive research, we chose the youth- and parent-reported DISC Predictive Scale, version four (DPS-4) asour diagnostic instrument. The DPS-4 contains a series ofquestions drawn from the Diagnostic Interview Scale forChildren that can be answered with a simple yes or no.The information provided can quickly be scanned by a cli-nician to validate their clinical interview findings. Overall,the use of scales should be part of the best practice stand-ard-of-care, but such scales should not add extensive timeto the patient care encounter, or they would become unre-alistic in clinical practice. To improve usability and to pro-vide comparability to European PCTs, we considering aswitch from the DPS to the Health of the Nation OutcomeScale for Children and Adolescents (HoNOSCA), whichcomes in child, parent and clinician formats, is shorterand simpler to administer and score than the DPS, and isa proven clinical trial endpoint [13-17]

For evaluation of effectiveness of interventions, we chosethe Clinical Global Impressions, Severity and Improve-ment scores (CGI-I, CGI-S) and the Child Global Assess-ment Scale (CGAS). We ask clinicians to rate the severityof primary illness, that for which study treatment was ini-tiated, overall mental illness, and global functioning.Where appropriate, we also ask the investigator to provideClinical Global Impressions-Tolerability (adverse eventburden) and Acceptability (formulation acceptability)scores, which when combined with a CGI-I score allowthe investigator to provide a composite CGI-Effectivenessscore based on the balance of benefits, tolerability andacceptability. Together, these simple measures provide areliable snapshot of the subject's diagnostic status andfunctioning over time.

Adverse Event MonitoringAdverse events (AEs) following treatment with psycho-tropic medication are a common but understudied causeof iatrogenic morbidity. Drug-induced, adverse events(AEs), including suicidal events, are more common inadolescents than in adults, and more common in childrenthan in adolescents. However, despite the availability ofvalid and reliable PCT friendly diagnostic and endpointassessments, we found no suitable measure available foradverse event elicitation. This is consistent with recentcritical reviews conducted by the Research Units on Pedi-atric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) indicate that little isknown about the incidence and prevalence of AEs, espe-cially less common events and, until recently, the field hasnot had a standardized procedure for prospectively ascer-

Page 10 of 13(page number not for citation purposes)

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2009, 3:12 http://www.capmh.com/content/3/1/12

taining common, rare or unique treatment-specific AEs[18-20].

Consistent with GCP standards and the goals of CAPTNitself, safety monitoring is a primary aim of most if not allCAPTN trials. To accomplish safety monitoring with theframework of the CAPTN eCRF, we required (1) an AEmonitoring tool to identify and record common AEs and(2) a mechanism for recording severe harms that wouldbe informative from a data perspective and would satisfyDSMB/FDA requirements for serious adverse event report-ing. To this end, using CAPTN as the platform, we devel-oped and psychometrically validated a new AE ratingscale, the Pediatric Adverse Events Scale (PAERS), which isdesigned to allow rigorous prospective identification ofAEs in a PCT framework [21,22]. Fully integrated with theCAPTN eCRF, the PAERS addresses the following issues:(1) simplicity and ease of use; (2) clinical applicability toa wide variety of drug exposures; (3) frequency, severity,and subjective importance of an AE; and (4) empirically-derived, psychometrically validated item content. ThePAERS, which can be administered at every visit or atselected visits, is a 45 item AE inventory estimated to take10–15 minutes to complete. Forty-three items containempirically-derived and validated item content and 2items are open. The PAERS includes child and parentforms intended to set the prior probabilities for the clini-cian to formally ascertain AEs the baseline and all postbaseline visits. Absent, a child or parent form, the PAERSincludes a clinician interview option. All three versionsuse a Likert-style response format in which the informantindicates how much each item (sign or symptom) wasbothersome or a problem. Having reviewed the itemswith the patient and parent, the clinician records all AEsand summary information on the PAERS clinician formincluding specifying presence in the past week, resolution,attribution, severity, and impact on function. Both for-mats – child/parent and clinician interview – are accepta-ble to doctors and patients and, hence, are frequently usedby CAPTN investigators in clinical practice.

While the PAERS provides an acceptable level of detail fortypical adverse events, it does not adequately assess seri-ous or harm-related events. Thus, having reviewed thePAERS, the study investigator also completes a separatescreen for parasuicidal behavior, suicidal ideation andbehavior, harm to others, and medical and psychiatricserious adverse events. The eCRF also includes a sectionon behavioral toxicity, including but not limited to behav-ioral activation, agitation, akathisia, disinhibition, inhab-itation, emergence or worsening of ADHD, and theserotonin syndrome. Any or all of these or any severeadverse event may then trigger the CAPTN eCRF SAE/Harm Form. If the event is serious non-psychiatric (e.g.hospitalization for a femur fracture), psychiatric (e.g.

mania or severe panic), or harm-related (suicidal event orharm to others) so some combination of these, the clini-cian will record systematic information in checklist form,including: narrative description, seriousness assessment(FDA SAE checklist), relationship to study medication,event status, event characteristics, relationship betweenmultiple events, harm to self/others type and detailedcharacterization, contributing factors, and event resolu-tion. To avoid the necessity of event adjudication, theCAPTN eCRF specifically provides for event coding underthe FDA's rubric for seriousness and the Columbia Suicidecoding scale[23,24]. Events are held open and trackeduntil resolved. Branching logic allows for relatednessacross compound SAEs. At the next visit, an event resolu-tion workflow is automatically triggered until the event isresolved or the patient exits the study.

The CAPTN eCRFAfter gathering feedback about the CRF and assessmentmeasures, and extensive analysis of the study data, werevised and finalized our core CRF battery. This batterywas then built into an electronic format using Clinipace'sTEMPO electronic data capture (EDC) system. This systemallowed us to make extensive use of logic checks andbranching to minimize the number of questions an inves-tigator would need to answer about a study patient, basedupon their answers to pervious questions. The validationallowed us to enact complex logic checks on screen, elim-inating the need for post hoc queries which are not feasiblein a PCT setting. This system is currently being used in theCAPTN Antidepressant Safety in Kids (ASK) trial as well asin a pharmacogenomic sub-study looking at genetic pre-dictors of suicidality and behavioral activation, amongother endpoints, and will be portable with minor modifi-cations for all future CAPTN practical clinical trials. Astandard platform, shared across the network allows a sig-nificant cost savings across studies.

ConclusionIt is widely acknowledged that clinical trials in psychiatryfrequently fail to maximize clinical utility for practicingclinicians, or stated differently, available evidence isn'tperceived by clinicians (and other decision makers) as suf-ficiently relevant to clinical practice, thereby diluting itsimpact [4]. To maximize clinical relevance and acceptabil-ity, researchers in other areas of medicine – such as cancerand cardiology – have turned to practical clinical trials,which are always simpler and usually larger than conven-tional efficacy clinical trials [8]. We recently made the casefor transporting the practical clinical trials model to psy-chiatry, defining requirements for stable funding for net-work construction and maintenance plus methodologicalinnovation in assessment, treatment, data management,site management, and data analytic procedures. [5].

Page 11 of 13(page number not for citation purposes)

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2009, 3:12 http://www.capmh.com/content/3/1/12

During its first five years, CAPTN successfully addressedthe aims of the NIH roadmap. Specifically, we have madeextensive use of information technologies to developedinnovative solutions to reduce the burden and cost of clin-ical research. In addition, were have responded to thecharge of setting the research agenda with input from awider array of stakeholders by partnering with the AACAPand enlisting representatives from advocacy organiza-tions. Together, these have allowed us to move the fieldforward and prove the feasibility of PCTs as part of anoverall move towards increasing the use of EBM in thefield of child and adolescent psychiatry. Over the next twoyears, CAPTN will complete the largest safety registry everin its field – a 500+ subject patient safety study of antide-pressants that will include specific measures for safetymonitoring and evaluation of behavioral activation andits putative link to treatment-emergent suicidality. Thiswill be coupled with a pharmacogenomic study to assessgenetic markers for antidepressant benefits and harms. Inaddition, CAPTN is in the process of conducting an equi-poise stratified randomized comparison of newer versusolder medications in ADHD. The information gained willmeaningfully improve the ability of both clinical and pol-icy decision-makers to make decisions in the best interestsof youth with mental illness.

In response to PAR-08-088 for Advanced Centers for Inter-ventions and/or Services Research (ACISR), the CAPTNteam is in the process of applying for a second five yearsof NIMH funding. If successful, CAPTN will completeongoing studies; expand to 250 active participants includ-ing an extension into Developmental and BehavioralPediatrics; restandardize and disseminate the PAERS; ini-tiate a pioneering programs of research in diversity, office-based parent management training in ADHD, and adap-tive treatment strategies in pediatric bipolar disorder; addcollaborative NIMH- and industry-funded clinical trialsand in so doing open the Network to outside researcherswishing to use CAPTN to conduct PCTs; conduct jointlywith the NIMH five field-leading workshops on topics rel-evant to practical clinical trials in pediatric psychiatry; andexpand career development initiatives begun during thefirst five years of funding. Accordingly, CAPTN promisesto enhance the public health relevant evidence base inpediatric psychopharmacology and to further develop thecapacity to conduct practical clinical trials in mentally illchildren and adolescents.

Competing interestsMark Shapiro has no competing interests to disclose.

Susan Silva is a member of a DSMB overseeing researchconducted by the NIMH. She has no other competinginterests to disclose.

Scott Compton is a scientific advisor for the TSA ClinicalTrials Consortium. He is a member of a DSMB for NIHFunded Trials.

Allan Chrisman is a consultant or scientific advisor for EliLilly, Addrenex and the NIMH.

Joseph DeVeaugh-Geiss is a scientific consultant for Voy-ager Pharmaceuticals, Schwarz Biopharma, Febre-KramerPharmaceuticals, Pozen Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithK-line, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, NuPathe, CeNeRx BioPharmaand JDS Pharmaceuticals. He has equity holdings (ownsstock) in GlaxoSmithKline and Pozen Pharmaceuticals,and Voyager Pharmaceuticals. He receives consulting feesfrom the venture capital companies of Scale Venture Part-ners and Sofinnova Ventures.

Alfiee Breland-Noble receives > $25,000 under separateindependent grants from NIMH funded clinical trials.

Douglas G. Kondo receives minor research support fromRepligen, Inc.

Jerry Kirchner has no competing interests to disclose.

John March is a consultant or scientific advisor to Eli Lilly,Pfizer, Wyeth and GlaxoSmithKline; an equity holder inMedAvante; the author of the Multidimensional AnxietyScale for Children (MASC); a member of a DSMB oversee-ing research conducted by Astra-Zeneca and Johnson &Johnson; conducts sponsored research for Pfizer: andunder separate independent grants receives study drugfrom Eli Lilly and Pfizer for two NIMH-funded clinical tri-als. Dr. March does not participate in Speaker's bureaus orother promotional activities.

Authors' contributionsWith JM as the senior investigator and author, all authorscontributed to the design and implementation of CAPTNand to the conceptualization and writing of this manu-script. All authors read and approved the final manu-script.

Corresponding AuthorJohn S. March, MD, MPH, Director, Division of Neuro-sciences Medicine, Duke Clinical Research Institute, DukeUniversity Medical Center, Durham, NC 27705, Email:[email protected].

AcknowledgementsSupported by NIMH grants 1 K24 MHO1557, 1 P30 MH66386 and by a NARSAD Distinguished Senior Investigator Award to Dr. March. The cited research meets all applicable Duke University and Federal guidelines for research.

Page 12 of 13(page number not for citation purposes)

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2009, 3:12 http://www.capmh.com/content/3/1/12

Publish with BioMed Central and every scientist can read your work free of charge

"BioMed Central will be the most significant development for disseminating the results of biomedical research in our lifetime."

Sir Paul Nurse, Cancer Research UK

Your research papers will be:

available free of charge to the entire biomedical community

peer reviewed and published immediately upon acceptance

cited in PubMed and archived on PubMed Central

yours — you keep the copyright

Submit your manuscript here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/publishing_adv.asp

BioMedcentral

References1. Zerhouni E: Medicine. The NIH Roadmap. Science 2003,

302:63-72.2. Zerhouni EA: Translational and clinical science – time for a

new vision. N Engl J Med 2005, 353:1621-1623.3. March JS, Silva SG, Compton S, Anthony G, DeVeaugh-Geiss J, Califf

R, Krishnan R: The Child and Adolescent Psychiatry TrialsNetwork (CAPTN). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004,43:515-518.

4. DeVeaugh-Geiss J, March J, Shapiro M, Andreason PJ, Emslie G, FordLM, Greenhill L, Murphy D, Prentice E, Roberts R, Silva S, SwansonJM, van Zwieten-Boot B, Vitiello B, Wagner KD, Mangum B: Childand adolescent psychopharmacology in the new millennium:a workshop for academia, industry, and government. J AmAcad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006, 45:261-270.

5. March JS, Silva SG, Compton S, Shapiro M, Califf R, Krishnan R: Thecase for practical clinical trials in psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry2005, 162:836-846.

6. Peto R, Collins R, Gray R: Large-scale randomized evidence:large, simple trials and overviews of trials. Ann N Y Acad Sci1993, 703:314-340.

7. Peto R, Baigent C: Trials: the next 50 years. Large scale ran-domised evidence of moderate benefits [editorial] [seecomments]. Bmj 1998, 317:1170-1171.

8. Tunis SR, Stryer DB, Clancy CM: Practical clinical trials: increas-ing the value of clinical research for decision making in clini-cal and health policy. Jama 2003, 290:1624-1632.

9. DeMets DL, Califf RM: Lessons learned from recent cardiovas-cular clinical trials: Part I. Circulation 2002, 106:746-751.

10. DeMets DL, Califf RM: Lessons learned from recent cardiovas-cular clinical trials: Part II. Circulation 2002, 106:880-886.

11. TADS: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study(TADS): rationale, design, and methods. J Am Acad Child AdolescPsychiatry 2003, 42:531-542.

12. TADS: Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and theircombination for adolescents with depression: Treatment forAdolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomizedcontrolled trial. Jama 2004, 292:807-820.

13. Brann P, Coleman G, Luk E: Routine outcome measurement ina child and adolescent mental health service: an evaluationof HoNOSCA. The Health of the Nation Outcome Scales forChildren and Adolescents. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2001, 35:370-376.

14. Garralda ME, Yates P, Higginson I: Child and adolescent mentalhealth service use. HoNOSCA as an outcome measure. Br JPsychiatry 2000, 177:52-58.

15. Gowers SG, Harrington RC, Whitton A, Beevor A, Lelliott P, JezzardR, Wing JK: Health of the Nation Outcome Scales for Childrenand Adolescents (HoNOSCA). Glossary for HoNOSCAscore sheet. Br J Psychiatry 1999, 174:428-431.

16. Gowers S, Levine W, Bailey-Rogers S, Shore A, Burhouse E: Use ofa routine, self-report outcome measure (HoNOSCA-SR) intwo adolescent mental health services. Health of the NationOutcome Scale for Children and Adolescents. Br J Psychiatry2002, 180:266-269.

17. Harnett PH, Loxton NJ, Sadler T, Hides L, Baldwin A: The Healthof the Nation Outcome Scales for Children and Adolescentsin an adolescent in-patient sample. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2005,39:129-135.

18. Vitiello B, Riddle MA, Greenhill LL, March JS, Levine J, Schachar RJ,Abikoff H, Zito JM, McCracken JT, Walkup JT, Findling RL, RobinsonJ, Cooper TB, Davies M, Varipatis E, Labellarte MJ, Scahill L, CapassoL: How can we improve the assessment of safety in child andadolescent psychopharmacology? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychi-atry 2003, 42:634-641.

19. Greenhill LL, Vitiello B, Riddle MA, Fisher P, Shockey E, March JS, Lev-ine J, Fried J, Abikoff H, Zito JM, McCracken JT, Findling RL, RobinsonJ, Cooper TB, Davies M, Varipatis E, Labellarte MJ, Scahill L, WalkupJT, Capasso L, Rosengarten J: Review of safety assessment meth-ods used in pediatric psychopharmacology. J Am Acad Child Ado-lesc Psychiatry 2003, 42:627-633.

20. Greenhill LL: Assessment of safety in pediatric psychopharma-cology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003, 42:625-626.

21. Wehmeier PM, Schacht A, Lehmann M, Dittmann RW, Silva SG,March JS: Emotional well-being in children and adolescentstreated with atomoxetine for attention-deficit/hyperactivitydisorder: Findings from a patient, parent and physician per-

spective using items from the Pediatric Adverse Event Rat-ing Scale (PAERS). Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health2008, 2:11.

22. March J, Karayal O, Chrisman A: CAPTN: The Pediatric AdverseEvent Rating Scale. Scientific Proceedings of the 2007 Annual Meetingof the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; October 23–28, 2007; Boston, MA 2007:241.

23. Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M: ColumbiaClassification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA):classification of suicidal events in the FDA's pediatric suicidalrisk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry 2007,164:1035-1043.

24. Posner K, Melvin GA, Stanley B, Oquendo MA, Gould M: Factors inthe assessment of suicidality in youth. CNS Spectr 2007,12:156-162.

Page 13 of 13(page number not for citation purposes)