The architectural conception of the museum in the work of Le Corbusier

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of The architectural conception of the museum in the work of Le Corbusier

The InternationalJournal of Museum Management and Curatorship (1983), 2, 177-189

The Architectural Conception of the Museum in the Work of Le CorbusieP

ALBERTO BORALEVI

Today the proposal of a historic reflection on the thought and museographical work of an architect who died almost twenty years ago, and about whom there is already a vast and highly varied critical bibliography, might perhaps appear inappropriate for a congress such as the Second International Congress of Museology (Florence, May 1982) entitled ‘The Museum in the Contemporary World, Concepts and Proposals’.-J- Even from its title, it seems rather that the Congress anticipated a concise debate on themes of burning current interest, with particular attention to the ‘planning’ and foreseeable aspects implied in the word ‘proposals’. Nevertheless, I consider that, in talking about museums, a discourse of a historical nature is always necessary, even when interest is primarily focused on present and future prospects, and I am firmly convinced that historical reflections, which are characterized and qualified by a museology that wishes to be a scientific, not improvised, discipline, are the only true guarantee against the danger of monotonous repetition of the same old stereotypes in which, unfortunately (and not only in Italy), the greater part of current debate on the museum is stagnating. On the other hand, it is easy to demonstrate the topicality of Le Corbusier’s message in the museographical and museological field, not only for the more narrowly architectural, planning aspect but above all for the ideas, the concept of the museum as he understood it. It is surprising, moreover, to note that this specific Le Corbusian theme has not yet been examined in depth, not even by the latest criticism, which has been principally engaged in distinguishing the formal aspects of Le Corbusier’s

architectural work from the validity of the socializing and standard-setting contents of his urbanistic thought. This fact is even more surprising when one realizes that a careful look at the eight volumes of the Oeuure Complde will suffice for one to understand how important the museum theme was to the ‘Maestro’. As was his habit, he worked on this theme at various times for almost forty years, spent between ‘patient research’ and ‘sudden insights’.

Le Corbusier’s interest in the museum was not, in fact, of an accidental nature, and did not spring from contingent circumstances, such as the commission of a project for a specific museum building. On the contrary, it was one of those themes we could call the great ‘leading motifs’ of his ‘poetics’, and come close in importance to the most celebrated projects such as The Housing Unit, or the Contempoyaq~ Citjjftiv Three Million Inhabitants. The latter, for example, conceived in 1922, was put forward again as the Plan Voisin in 1925, and then once more presented as a plan for Paris 1937, to be newly redeveloped in 1946. Likewise, and with perhaps even greater perseverance, the original idea in 1929 for a ‘World Museum’ (in the

* Edited translation from the Italian text by Cynthia Rockwell.

t The Italian version of this article was presented to this Conference.

0260~4779/83/020177-13$03.00 6 1983 Butterworth & Co (Publishers) Ltd

178 The Museum in the Work of Le Corbusier

/

‘!S

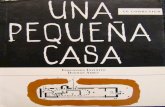

Figure 1. Le Corbusier, project for French Pavilion at the International Exhibition of 1939, San Francisco/Liege, general view and plan (Vol. III, 1934-38, p. 173).

context of Paul Otlet’s ambitious and utopian project for a Mundaneurn or world city of culture to be built on Lake Geneva) evolved from a ziggurat form to the ‘square spiral’ in the first development of a museum of ‘unlimited growth’, which was proposed in 1931 for the contemporary art collections of Paris. The same model was then presented in the context of the buildings to be put up for the Paris International Exposition of 1937, and then put forward again as the principal unit of the subsequent International Exposition of 1939, which was to have been held in Liege or San Francisco.

In spite of the war looming over Europe, the same project, further developed and articulated, was proposed yet again in 1938-39 for the city of Philipeville in North Africa and, after the War, the same distinctive ‘square spiral’ form reappeared amongst the buildings which comprised the Civic Centre (the ‘heart of the city’ in the wording later adopted by the CIAM)’ in the urban plan for Saint-Die (1945). Only between 1952 and 1959, however, was Le Corbusier able to realize two museums, at Ahmedabad and Tokyo, which we can define as prototypes of the ‘museum of unlimited growth’, to the same extent that the Pavilion of the Esprit Nouveau in 1925 was a .prototype of a cell of the Immeuble Villa, and the Unitk d’Habitation in Marseille was a single element of the Vile Radieuse. The idea of the extendability of the exhibition space was not abandoned with these projects, nor was that of

ALBERTO RORALEVI 179

the ‘museum complex’, composed, in addition to the museum itself (understood as a

‘machine for exhibiting’, as a house was to be a machine i habiter), of its ‘prolongations’ (obviously parallel to the ‘prolongations’ of a house). Indeed, the project for Tokyo, which also incorporated the experience of the studies made for an exhibition dedicated to the ‘Synthesis of the Major Arts’ (Porte Maillot, Paris 1950), already had this composite

Figure 2. Le Corbusier, project for a Museum of Unlimited Growth, Philipeville, North Africa, 1939, and the principle of the squared spiral (Vol. IV,

1938-46, p. 16).

configuration, and was to be developed subsequently in 1963 with the project for a M&e du XX Sikle, conceived on a European scale for the little town of Erlenbach, near Frankfurt-am-Main, situated at the intersection of the main routes connecting Stockholm with Rome, and Paris with Vienna, Belgrade and Bucharest. This project which, not by chance, was presented with the method we can without reservations define as ‘museological’ of the ‘CIAM Grill’, summarized all the preceding studies for the ‘museum of unlimited growth’, completed by a greater articulation of the so-called ‘prolongations’, composed of a pavilion for exhibitions with the characteristic double umbrella steel roof, some adjacent buildings dedicated primarily to the performing arts (the Boite i Miracles and the Thiatre Spontanhe), in addition, of course, to the studios, store rooms and a sculpture garden. Though this project also remained on paper, Le Corbusier managed at least to begin construction of a third prototype with the Museum of Fine Arts at Chandigarh (1964-65).

180 The Museum in the Work of Le Corbusier

Even without all its prolongations, this museum resembles fairly closely the museum building proposed for Erlenbach.

Le Corbusier’s constancy in reiterating and re-proposing his own ideas has become legendary and perhaps if he had lived a few years longer he would have succeeded in building a ‘Museum of the Twentieth Century’. His last project, in fact, and absolutely his last sketch, signed and dated ‘29/6/1965’, the very day of his death (which occurred, as is known, at Cap Martin while he was taking a swim), is the study for yet another museum of the twentieth century to be constructed at Nanterre, commissioned by Andre Malraux, then Minister of Cultural Affairs. After the ‘Master’s’ death, these sketches were worked up in 1969 in an outline plan by his collaborator, Andre Wogenscky, who re-proposed, although in a somewhat different context, the concept of the museum of ‘unlimited growth’ and of the ‘square spiral’. It is also remarkable that another delayed project for an exhibition structure was in the meantime completed; this time carried out in Zurich after the architect’s death, becoming in fact a ‘Le Corbusier Centre’, destined to house drawings, paintings and sculpture by the architect himself. This time the exhibition pavilion with a metal roof, having the characteristic squared double umbrella form, was used. The first studies for this probably date back to 1928 with the dismantlable publicity pavilion for the Nestle company, and were then revived in several projects for the French pavilion at the 1939 Exposition in Liege and for the exhibition centre to be set up in the Porte Maillot area in Paris (1950). The exhibition

yL& D’l+Eu!z DE MARCHE A PiaDs

Figure 3. Le Corbusier, plan of the Civic Centre for Saint-D%, France, 1945, showing (5) another version of the Museum of Unlimited Growth (Vol. IV, 193846, p. 139).

ALBERTO BORALEW 181

pavilion subsequently becomes a constant element in the various museum projects, both as ‘prolongation’ of the museum, starting with the first project for Tokyo, and also as a structure

in itself in the study for an Exhibition Palace to be constructed on the water in Stockholm (1962), which was intended to have works by Picasso, Matisse and Le Corbusier himself.

Figure 4. Le Corbusier, cross-section of the Museum of Unlimited Growth, designed as a part of the project for the Paris International Exhibition, 1939; detail showing the lighting system (Vol. III,

1934-38, p. 155).

The Le Corbusier Centre in Zurich was born, instead, as an experimental prototype of a structure that would respond to the dual function of home and museum, in which: ‘ “L’architecture” et les oeuvres doivent apparaitre dans “l’echelle modeste et nomade” d’une maison d’habitation avec ses mesures i “l’&helle humaine” Cvitant ainsi l’arbitraire kventuel des salles dites “d’expositions”.‘* The search for a ‘human scale’ for the museum seems to be a constant ofLe Corbusier’s work, and is made explicit, in this last project, by the application of the proportional system of the Modular.” Next to all these projects, which constitute the path of ‘patient research’ in the museographical field, Le Corbusier also studied other exhibition buildings which, although they diverge from the theory of the ‘museum of unlimited growth’, are still of assistance in understanding his specific concepts in the museal sector, demonstrating once again the diligence of his research, particularly with regard to the technical aspects of museography such as lighting and the internal circulation of the museum.

1935 is the date of an interesting study for two large museums housed in a single building, which were meant to be included in the works for the Paris International Exposition of 1939. The project, presented at the competition for the ‘Museum of the City and the Museum of the State’ in Paris, was immediately rejected by the jury, but was nevertheless published in the journal Mouseion, in which it was judged the only true museographical project proposed; that is, the only one that responded to the requirements of the modern science of museology. To understand the extent of Le Corbusier’s awareness of the museographical question, it is

182 The Museum in the Work of Le Corbusier

necessary to quote the very words with which he presented this project in Volume 3 of his Oeuvre CompGte:

Acoustics or physics of sound for the conference rooms, physics of light-law of incidence of light for the museums. This is a basis for working! And there are still more. The underlying concept of this project is the search for daylight, which enters the rooms under controlled conditions. Each of the two museums, once the threshold is crossed, becomes a continuous museographical event. Circulation occurs without interruptions and with perfect clarity through inclined ramps: there are no stairs. The visitors’ route is as clear as a mountain path which opens to the right and to the left into successive valleys. It is this directed path that constitutes the tourist visit. Each valley is a different museographical section, and can be further subdivided into two or three side galleries for study (where one finds those works considered at the time to be less significant than those displayed on the main tourist route) and a reserve gallery (where each museographical section organizes its objects in store in a display, and with prearranged

lighting). On the other hand, the museum is like a vast architectural symphony, in which

unexpected, intimate or majestic points of view converge, while the eye is often able to embrace the totality of the interior. The separation of the two museums is clear, but they share common systems for servicing the works, packing, maintenance, etc., as well as the vertical linking structures. Finally, the concept itself of the volumes, organically articulated, results in varied external architectural forms, suitable for enhancing the sculptures displayed outdoors.’

Another interesting project from the museographical point of view is the Visual Art Center of Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts (built 1961-64), where the concept of the ‘architectural promenade’ is present, derived from the Villa Savoye at Poissy and applied here to an exhibition route. Le Corbusier had already proposed a very similar idea for the project of the French pavilion for the 1939 Exposition at Liege, mentioned above. In this, the ‘route’ is separated completely from the structural container and becomes the architectural element that organizes the internal arrangement. Similarly in the VAC (which is also an exhibition hall, as well as an art school for Harvard students, who can visit it freely), the ramp traversing the building has the dual function of accentuating the idea of the interpenetration of the outside and inside environments, and of guiding the visitor on an itinerary with museum characteristics. The Museum of Knowledge at Chandigarh (1960-65) is entirely different, being the result of a transformation of a project originally conceived as the Governor’s Palace. It is, however, endowed with a system of extremely mobile and flexible internal fittings.

With regard to the organization of internal museum spaces, it is also necessary to refer to the various exhibitions projected or realized by Le Corbusier, starting with the pavilion of the ‘Esprit Nouveau’ (1925) with its large urbanistic dioramas, passing on to the ‘Pavillon des Temps Nouveaux’, proposed in 1937 to the Paris International Exposition as an ‘Essai de M&e d’Education Populaire (Urbanisme)‘. In this unusual pavilion, it was precisely the ‘didactic’ organization of the internal space that was notable, with a great profusion of dioramas, blow-ups, collages and photo-montages. In the so-called conference room at the centre of the exhibition space, an airplane model was displayed, recalling that designed for the Bat’a pavilion, planned but not realized by Le Corbusier for the same Paris exposition. Entrance to the pavilion was gained by a large revolving door, installed on the central axis, a system Le Corbusier was to use again both at Ronchamp and in the Zurich pavilion mentioned above. The light structure of canvas and steel cable was, instead, rather unusual

ALBERTO BORALEVI 183

for Le Corbusier, and perhaps comparable only to the curious project twenty years later for the Phillips Pavilion in Brussels in 1958, which foreshadowed the ‘tensile’ structures of the German architect, Frei Otto, in its formal results. In any case, the idea of constructing a shell, a covering within which the internal space is freely developed, is typical of Le Corbusier’s museological conception and analogous to the concept of the exhibition pavilion of Porte Maillot and of Zurich.

The same idea was also present in the less well-known 1938-39 project for an exhibition entitled the ‘Ideal Home’, which was to be held in London, and for which a fragment of the Ville Radieuse was to be constructed inside a large, pre-existent exhibition hall. Other internal arrangements of some interest are those of ‘so-called Primitive art’ in Le Corbusier’s

own apartment (1935), and the exhibiton of ‘France Overseas’ at the Grand Palais in Paris in 1940, in which the space was resolved in an original way, with a series of panels arranged obliquely with respect to the background wall and linked together by a false ceiling with the lighting system inside. The 1950 studies for Porte Maillot also contain numerous sketches of internal fittings, and the two shows on Le Corbusier, held at the National Museum of Modern Art in Paris in 1953 and at the Musie des Beaux-Arts in Lyon in 1956, offer the best image of what the Swiss architect meant when he spoke of a museum on the ‘human scale’.

Even such a rapid review of the museographical works serves, in my opinion, to give an idea of the importance this theme held for Le Corbusier, if only from what we might call a ‘quantitative’ point of view. From the ‘qualitative’ viewpoint instead, that is, if we wish to get down to the concepts and ideological contents of these projects, it is necessary first of all to observe that, in contrast to the Futurists or other so-called ‘avant-garde’ artistic groups, Le Corbusier never repudiated the museum, even if he criticized it severely, especially in its

Figure 5. Maison de 1’Homme (Centre Le Corbusier), Zurich, 1963-65

184 The Museum in the Work of Le Corbusier

nineteenth century form. He understood that the museum is above all a means of visual communication, and accepted it as such, developing it in the non-verbal language of images, objects and symbols which was the language most congenial to him. In 1925, in one of the articles dedicated to the famous Paris show of Decorative Arts, he expressed himself thus about the museum in the pages of Esprit Nouveau:

Museums. There are beautiful museums and ugly museums. And there are those that contain a

hodge-podge of the beautiful and the ugly. But the museum is a consecrated entity that circumscribes our powers of judgement.

Birthdate of the museum: 100 years, age of humanity: 40 or 400 000 years. Dear woman, just to see her purse her mouth when she says, ‘my little girl is at the

museum’, she seems convinced of being a pillar of humanity! Museums have just been born, they did not exist before. Let’s say then they don’t

answer a basic human need like bread, water, religion, writing. Certainly, they have their good sides, but let us risk a startling deduction: the

museum permits a denial of everything because, when everything is certain, everything has a place and an explanation, and nothing from the past has a direct use, because our life on earth is a road that doesn’t return on the same track. So that, in the end, it is the eternal law: in the tendentious incoherence of museums there is no model, it is there only for the elements of a judgement. . . .’

After criticizing the institution, however, Le Corbusier immediately retrieves it in order to turn it to a different, more modern, use from the moment he understands its importance and

real potential.

Let us imagine the true museum, that which holds everything and above all can furnish information centuries later when these will have destroyed (as only they know how to destroy) so well, so perfectly, that almost nothing is left except for the objects of great pomp, of great vanity, of great pleasure, which always escape disaster (to bear witness to the unfailing survival of vanity). To delineate this concept well, we want to build the museums of today with the objects of today, thus we list them:

A plain-coloured jacket, a bowler hat, a well-sewn shoe. A lightbulb in its socket; a radiator, a tablecloth of fine white cloth; and also the glasses we use every day, the bottles from Champagne and the Bordeaux region, etc. . . .6

The list goes on at some length, including among others the inevitable Thonet chairs, but at the end the unavoidable comment is that:

In truth this museum does not exist yet. That would be a loyal and honest museum; it would be useful in that it permits one to choose, to approve or reject; it would allow one to grasp the meaning of things and it would spur on improvement.

The tourists who climb Vesuvius sometimes stop at the museums of Pompeii and Naples, but what interests them most are the sarcophagi loaded with sculpture.

And yet Pompeii, following an event that has a touch of the miraculous, constitutes the only true museum worthy of the name. Noting how precious it is for the education of the masses, one can only hope to see a new Pompeian museum of the modern epoch built in our time. . . .’

This, then, was Le Corbusier’s idea of the museum in 1925, from which, leaving aside the polemical hints, his consciousness of the museum’s educational function, and thus its importance, appeared sufficiently clear. From 1929 we have the first museographical project:

ALBERTO BORALEVI 183

Figure 6. Le Corbusier, dismantlable exhibition pavilion for NestlC, 1928 (Vol. I, 1910-29, p. 174).

the World Museum, conceived in the particular context, delineated by his friend Paul Otlet, of the Mundaneum: ‘a world centre, scientific, documentary and educational, at the service of the International Associations, to be founded in Geneva in order to complete the institutions of the Greater League of Nations, and to commemorate in 1930 a decade of effort for peace and cooperation’. The stated aim of the Mundaneum is to exhibit and make known the evolution of human civilization through writings, words and objects. To foster knowledge through objects is thus the task of the World Museum (and of any museum). It is flanked by an International Library and a Centre, again international of course, of University Studies, as well as various other institutes. The singular feature of the museum, which as we have seen would have given rise to the museum ‘of unlimited growth’, is that of simultaneous exhibitions of the objects as well as the times and places that have produced them. This exhibition was intended to be organized in three parallel and continuous naves which were to run along a spiral route beginning, at the top, with prehistoric times, and slowly unfold in ever larger rings (and ever richer in informative contents) as they descended until they reached contemporary times. This, then, is a museum that intended to present exhibitions in their historical setting and cultural context, perfectly in tune with the most advanced museological theories of the day, such as those being tested by Alexander Dot-net-, then director of the Hannover Landesmuseum.

The idea of a museum of ‘unlimited growth’ made its debut in December 1930 with a letter addressed to Mr Zervos of Cahiers d2rt. The letter does not propose a museum project, but

186 The Museum in the Work of Le Corbusier

‘a means to arrive at building a museum in Paris according to conditions that are not arbitrary but, on the contrary, follow the natural laws of growth which are the same as those through which organic growth manifests itself: an element that is susceptible to adapting itself in harmony and in which the idea of the whole precedes the design of the parts’.* It seems clear that some fundamental elements of his museological conception were already defined in Le Corbusier’s mind at this stage. They may be tentatively summarized as follows:

1. Internal and external flexibility, according to a predetermined law of growth (the square spiral);

2. Overhead illumination, whether natural or artificial, with particular study of the angle of incidence and reflection of the flow of light;

3. The museum ‘without facade’, which one enters from beneath pilotis, or through a subterranean passage, penetrating directly to the core of the structure;

4. The central nucleus, a large square hall which constitutes the heart of the museum, entrance atrium and constant reference point for every visitor route, which uncoils with continuous circulation and without stairs;

5. Gardens surrounding the museum, initially as space to equip for services and outdoor sculpture display, and subsequently to accommodate the ‘prolongations’ of the museum itself.

In 1937, the same project for a museum ‘without facade’ was developed in detail, with particular attention to the study of the skylights for interior illumination, and to internal circulation around lightweight, movable screens. In the project which followed, for Philipeville in North Africa (193%39), the accent was instead on the standardization of the construction elements and the perfect modularity of the whole, based, naturally, on the proportional ratios of the golden section. To avoid the labyrinthine effect of the spiral, Le Corbusier also felt the need to provide orientation-a constant problem in museums. For this, he created priority directions along the four arms of a swastika, which were to extend from the central nucleus, and from which, on raised platforms, the visitor could have an overview of the entire exhibition at any time. In 1950, with the project for the Porte Maillot in Paris, Le Corbusier had the opportunity to give a greater organic unity to his concept of the museum, in which he saw the possibility of giving forms to his old idea of a ‘Synthesis of the Major Arts’. In fact, he sought an integration between painting, sculpture and architecture, and he found it precisely in the museum, which was to become a ‘Svnthesis Factory’ where cooperation between different artists was possible under ‘varied architectural conditions’. In any case, for Porte Maillot the project then almost exclusively concerned the study for the metal-structured exhibition pavilion, subsequently realized in Zurich. Originally it was conceived as a ‘metallic construction which permits the realization of interchangeable exhibitions, renewable at will, which can also be dismounted and sent to other countries’.

In the succeeding phase, characterized as we have seen by the realization of prototypes, one can observe that while, in the initial project for Ahmedabad (1952), the Bofte li Miracles appeared for the first time, destined to host performances that also take place outdoors, only with the plan for Tokyo (1956-59) did the museum acquire more complete definition with the principal exhibition nucleus and all its annexes, ‘les prolongements du mu&e’. In Tokyo the body of the museum is quite similar to that proposed for Philipeville, but the illumination technique is completely different, making use of a roof equipped with ‘illumination galleries’ and with a large ‘shed’ skylight, tetrahedral in form, which lights the central hall, the nucleus of the museum. These particular lighting devices assume in the building, which was realized by the Japanese architects Maekawa and Sakakura, a special prominence also for the formal

ALBERTO BORALEW 187

definition of the internal spaces, consistent with the principle that light is one of the dominant factors in the creation of the exhibition spaces. Apart from the Boite h Miracles, connected to an outdoor theatre, there is a large conference hall directly connected to the museum, a metal-roofed pavilion for temporary exhibitions, and a sculpture garden. The museum, on two floors, is also endowed with a TableauthZque, with the paintings mounted on sliding

Figure 7. Le Corbusier, General Plan of the Visual Arts Center, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1961-61 (Vol. VII, 1957-65, p. 55).

screens arranged like a comb. Finally, with the 1963 project for an International Art Centre to be constructed in the country at Erlenbach, near Frankfurt-am-Main, one arrives at the complete development of the M&e du Xx’ SiZcle, a project on a European scale that appears to have the same utopian ideals as the World Museum of 1929. In this way the museum acquires an urbanistic dimension, it is no longer a building that is to furnish the ‘heart of the citv’, as in the civic centre of Saint-D%, but a place in itself, centre of life and of cultural achvities, of communication of art and of performances.

In such a context the figure of Le Corbusier, as museologist and museographer, undoubtedly emerges, also with respect to other protagonists of twentieth century architecture such as Mies Van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright, Alvar Aalto, or, more recently, Louis I. Kahn. These, and yet others, have often ventured into the planning of museum buildings, and have also succeeded in realizing works of great value and interest, but in my

188 The Museum in the Work of Le Corbusier

opinion they have never attained Le Corbusier’s completeness of theoretical formulation. In the last analysis, Le Corbusier developed a veritable philosophy of the museum. Certainly Le Corbusier’s museum, like almost all the works of this architect, is essentially a model rather than a true architectural typology, with a strong utopian component, and is thus destined to change and degenerate in the moment of concrete application and in confrontation with the political and social realities of which it is obliged to become a part. In any case, simply because it is a model, it seems to me that this museum concept should be studied and carefully considered today, yet with a critical eye and a recognition of its limitations which are, as Ragghianti has observed, in not having taken into consideration the ‘differentiation of the works destined for the inside’. For Le Corbusier’s first great requirement was to ‘produce an expression of one’s own, with regard to the problem of building an organism of service, an

Figure 8. Le Corbusier, Interior of the Pavilion des Temps Nouveaux, Porte Maillot, Paris, 1937 (Vol. III, 1934-38, p. 163).

instrument of understanding of the works of art to be put in the container’.” One must admit, however, at least at the theoretical level, that Le Corbusier also sought to resolve the problem of the relationship between the works and the architectural container, in his declared search for a ‘Synthesis of the Major Arts’.

To achieve this synthesis in concrete form, and therefore succeed in preserving the principles of exhibition ‘on a human scale’, a flexibility of space, optimum lighting conditions, continuous circulation and ease of orientation for the visitor, would mean the final achievement of the Museum of the Twentieth Century which Le Corbusier never succeeded in realizing.

ALBERTO BORALEVI 189

Figure 9. Le Corbusier, Exhibition of ‘France Overseas’, Grand Palais, Paris, 1940 (Vol. IV, 1938-46,

p. 91).

Notes and References

1. International Conferences of Modern Architecture, founded by Le Corbusier in 1928 and prolonged until after the end of the Second World War. 2. Le Corbusier, Oeuvre Complite, vol. 7 (Zurich, 1957-65), p. 22.

3. Modular principle invented by Le Corbusier, based on the golden section and on the measure of 2.26 m,

corresponding to a man with his arm raised.

4. Le Corbusier, Oeucre Complite, vol. 3 (Zurich, 1934-38), pp. 82-89.

5. Le Corbusier, Arte Decorutica e Design (Bari, Laterza, 1972). p. 15.

6. Ibid. p. 16.

7. Ibid. p. 17.

8. Le Corbusier, Oeuvre Complth, vol. 2 (Zurich, 1929-3-I). p. 72.

9. Carlo L. Ragghianti, Arre, Fare e bjdere (Firenze, Vallecchi, 1974), p. 163.

Figures l-4 and 6-9 are taken from Le Corbusier, Oeuvre Compldte, by kind permission of the publishers Verlag

fur Architektur, Artemis, Zurich. Figure 5 is by the author.