Tensions of network security and collaborative work practice: Understanding a single sign-on...

Transcript of Tensions of network security and collaborative work practice: Understanding a single sign-on...

Journal Identification = IJB Article Identification = 2723 Date: July 2, 2011 Time: 3:6 am

Tpr

RU

a

A

R

R

1

A

K

H

A

S

W

E

C

1d

i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f m e d i c a l i n f o r m a t i c s 8 0 ( 2 0 1 1 ) xxx.e49–xxx.e61

j o ur nal ho mepage: www.i jmi journa l .com

ensions of network security and collaborative workractice: Understanding a single sign-on deployment in aegional hospital

osa R. Heckle ∗, Wayne G. LuttersMBC, United States

r t i c l e i n f o

rticle history:

eceived 5 May 2010

eceived in revised form

9 October 2010

ccepted 1 February 2011

eywords:

ealthcare

uthentication

ecurity

ork practices

thnography

SCW

a b s t r a c t

Background: Healthcare providers and their IT staff, working in an effort to balance appro-

priate accessibility with stricter security mandates, are considering the use of a single

network sign-on approach for authentication and password management. Single sign-on

(SSO) promises to improve usability of authentication for multiple-system users, increase

compliance, and help curb system maintenance costs. However, complexities are intro-

duced when SSO is placed within a collaborative environment. These complexities include

unanticipated workflow implications that introduce greater security vulnerability for the

individual user.

Objectives and methodology: In this work, we examine the challenges of implementing a single

sign-on authentication technology in a hospital environment. The aim of the study was to

document the factors that affected SSO adoption within the context of use. The ultimate

goal is to better inform the design of usable authentication systems within collaborative

healthcare work sites. The primary data collection techniques used are ethnographically

informed – observation, contextual interviews, and document review. The study included a

cross-section of individuals from various departments and varying rolls. These participants

were a mix of both clinical and administrative staff, as well as the Information Technology

group.

Results: The field work revealed fundamental mis-matches between the technology and rou-

tine work practices that will significantly impact its effective adoption. While single sign-on

was effective in the administrative offices, SSO was not a good fit for collaborative areas.

The collaborative needs of the clinical staff unearthed tensions in its implementation. An

analysis of the findings revealed that the workflow, activities, and physical environment

of the clinical areas create increased security vulnerabilities for the individual user. The

clinical users were cognizant of these vulnerabilities and this created resistance to the

implementation due to a concern for privacy.

Conclusion: From a preliminary analysis of our on-going field study at a community hospital,

there appears to be a number of mismatches between the SSO vision and the realities of

e ca

routine work. While wits goals in a hospital envi

will make the manageme

∗ Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 703 983 9973.E-mail address: [email protected] (R.R. Heckle).

386-5056/$ – see front matter © 2011 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights resoi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.02.001

nnot conclusively say if a SSO adoption will be effective in meeting

ronment, we do know that it will affect the work practice and that

nt of the SSO system problematic.

© 2011 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

erved.

Journal Identification = IJB Article Identification = 2723 Date: July 2, 2011 Time: 3:6 am

i n f

xxx.e50 i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f m e d i c a l1. Introduction

Healthcare organizations are struggling to meet ever increas-ing security requirements and comply with stricter regulatoryrequirements for individual accountability. Calls for more effi-cient operations are issued in tandem with demands fortighter privacy and security controls. In response to thesemandates, healthcare administrators are challenged to reachan optimum level of security while negotiating the trade-offs associated with the expense, acceptance, and usability ofpotential solutions which must respond to the unique require-ments of a healthcare environment.

User authentication mechanisms for data access controlsand audit capabilities are central to any comprehensive secu-rity program. This is the process of identifying and confirmingthe identity that a user is asserting to be and then grantingaccess privileges to resources based on that identity. Currentlysingle sign-on (SSO) technologies have emerged as an effec-tive means of addressing these authentication challenges. SSOprovides a computer user the ability to log in to a networkonce and then be able to navigate the myriad of applicationsseamlessly without the need to enter authentication creden-tials for each application. SSO promises to improve usability ofauthentication for users of multiple-systems, increase com-pliance, and help curb system maintenance costs. However,while SSO is very effective for some organizations, for othersit is problematic. Difficulties emerge in trying to fit authenti-cation that is individually oriented into an environment thatis collaborative in nature.

1.1. Regulatory environment

The ability to share patient medical data using electronichealth records (EHR) is a critical factor in the United States’national effort to increase the quality of healthcare for allindividuals. The goal for EHR systems is that they should con-tain a comprehensive record of an individual’s personal healthinformation and this record should be available to all medicalproviders, at any location, at any time. However, the visionfor interoperable electronic health records has not yet cometo fruition and its implementation has been fraught with con-troversy. One of the main barriers to widespread EHR adoptionis the concern for confidentiality of personal health informa-tion [1–5]. To protect patient privacy in the United States, theFederal government introduced the Health Information Porta-bility and Accountability Act (HIPAA). According to HIPAA, anorganization must guarantee the integrity, confidentiality, andsecurity of sensitive patient data. In addition, access controlsmust not only ensure appropriate access, but must also main-tain audit records of actual access for accountability [6].

Authentication mechanisms are one security measure thatprovides the data access controls and audit capabilities calledfor in these regulations. There is a range of possible technicaland business solutions for electronic authentication. Thesesolutions vary in terms of their cost, complexity, and assur-

ance levels. The challenge of identifying an optimal solutionlies in the fact that there are a multitude of forces exertingtensions on the design decisions and ultimately the adoptionof authentication mechanisms. The organization has to deter-o r m a t i c s 8 0 ( 2 0 1 1 ) xxx.e49–xxx.e61

mine how to manage the competing needs of the regulatoryrequirements with the functionality of competing suites oftechnologies, within an already strained budget. In addition,addressing workflow in data access security is a very difficultproblem, with many socio-technical complexities. While therehave been great strides made in the development of advancedtechnologies; when these technologies are placed in context,they rarely work as the designers intended [7,8]. For exam-ple, in a healthcare environment, there is a need to balanceinformation security without impeding the quality, timeli-ness, and effectiveness of healthcare delivery [9–12]. In thisenvironment, total security is an impractical goal; however,total insecurity is negligent. Rather, the goal is an equilibriumamong multiple criteria, where the tradeoffs in security andusability are equally weighted against the objectives of thesystem and the needs of its users.

With any authentication mechanism, there is an inher-ent tradeoff between security strength and usability [13–15].Mechanisms that are easy to use frequently relinquishsome security strength, just as those mechanisms that offerstronger security often prove more cumbersome to use. Mech-anisms that promise both usability and strength come withgreater financial costs. While there are many unique secu-rity approaches that stand to make significant in-roads overthe next decade – biometrics for one – the authentica-tion method of choice for now, for most industries, is thetraditional id/password pair. The id/password method forauthentication has the advantage of being both simple andeconomical. However, problems arise when users have tomanage a large number of unique username/password com-binations as they navigate all of the applications required forthe job. A host of studies have documented the problems withpassword authentication, citing human cognitive limitationsat the core of the issue [13,16,17]. There is an increasing pushtoward stronger, more abstract passwords (e.g., “%rT31x$” vs.“Susan1942”). However, these are difficult to remember caus-ing users to be reluctant to change them or they write themdown thus subverting the mechanism and causing a securitybreach.

SSO technologies are designed to allow a user to loginto a network once with a single robust password and thenbe able to navigate their myriad of applications seamlesslywithout the need to enter further authentication credentialsfor each application. There are many stated benefits to SSOtechnology. It promises to improve usability of authentica-tion for multiple-application users, increase compliance, andhelp curb system maintenance costs. In theory this approachappears to be a simple technical solution; however, in practice,when the technology is placed within a highly collaborativeenvironment such as that of a healthcare facility, the complexsocio-technical challenges emerge.

The healthcare environment poses many challenges to nor-mal authentication that are not apparent in other industries.Its unique organizational structure, multiple professionalcultures, and criticality of its work can create barriers toauthentication technology acceptance and use. In health-

care, there is an explicit need to balance the accessibility ofa patient’s health information (usability) to support collab-orative work with the need to comply with HIPAA privacyand security mandates (security strength). However, individ-Journal Identification = IJB Article Identification = 2723 Date: July 2, 2011 Time: 3:6 am

o r m a

utommdeTai

lcnsmAnbcmcshafsfchcttb[mctftSa

2

Sbsteibuntoiao

i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f m e d i c a l i n f

al authentication and collaboration are in a fundamentalension. To address this, hospitals have promoted a policyf providing data only on a “need to know” basis. However,edicine is not a mechanistic process where roles and infor-ation needs are all known in advance; instead, it is a dynamic

iscipline where many individuals require access to differentlements of a patient’s record throughout their care lifecycle.hus, the “need to know” rule cannot be codified in softwarend automatically applied to all situations; it is something thats routinely negotiated through social means.

The problem of bridging individual authentication and col-aborative work has been reviewed in the past. One of thehallenges identified in the limited research literature is theeed to use authentication mechanisms that recognize thehift from individual work to collaborative work as well asechanisms that do not interrupt the daily workflow [10,12].t the present time “the conventional log in procedures doot in any sense recognize the nature of medical work aseing nomadic, interrupted, and cooperative around sharingommon material [12].” In addition, the healthcare environ-ent is a rich ecology of heterogeneous technologies whose

omplexity is only increasing among hardware configurations,oftware applications, and vendors. The many applicationsave a wide variety of log in protocols, account structures,nd user ID/password control mechanisms. As the user movesrom one application to another, which is the norm in clinicalettings, the user is often required to re-authenticate with dif-erent user credentials. For the user, they must remember theirredential for all of these systems and they must rememberow the application interface works for each separate appli-ation. This is particularly problematic when one considershe work structure of a hospital and clinical setting wherehe physicians may only be at a given hospital on a sporadicasis and clinicians move from one department to another

10]. To be effective in this environment the design and imple-entation of an authentication mechanism must take into

onsideration the particular dynamics of the environment. Ashe CIO of GH commented, “We know we want to get a strongorm of authentication in there, but which one works best ishe big question. We don’t know that yet.” The question is: willSO technologies be an effective authentication technology in

healthcare setting?

. Research motivation

SO is a relatively new technological innovation so there haveeen limited large-scale implementations and even fewertudies of its deployment. Thus, little is known of its adop-ion patterns and ultimate effectiveness in most healthcarenvironments. As is true of all socio-technical systems, themplementation of a technology not only affects work practice,ut the technology is, in turn, affected by the dynamics of itssage environment [18]. Therefore, to determine the effective-ess of SSO as a viable authentication solution for healthcare,

he technology must be examined within its intended context

f use. For collaborative technologies, research suggests thatt is important to design systems that are “flexible, nuanced,nd contextualized,” [19] allowing for the natural balancingf social and technical system components. This is difficult

t i c s 8 0 ( 2 0 1 1 ) xxx.e49–xxx.e61 xxx.e51

in general, but particularly vexing for access control systems.These systems appear to portray a very simplistic usage modeland implementers often take a very technology deterministicview of their implementation. However, authentication tech-nology when used in collaborative environments presents amore complex set of issues. To address this, research suggeststhat a socio-technical approach to system design may be help-ful. The effectiveness of an authentication security technologycannot be judged by simply evaluating the merits of its func-tions. The technology must be viewed and evaluated upon itsmerits within the particular context within which it will beused [10,12,13,20,21].

Recall that, increased government regulations placed pres-sure on healthcare organizations to increase IT usage andgovernance programs in an effort to meet at least the baselinerequirements and demonstrate adequate audit due process.In response to these external pressures, our study site wasimplementing SSO because it was considered an industrybest practice [22], as well, the vendor technology availablewould be cost effective as it integrated well with their exist-ing infrastructure. The vision the organization had for theimplementation included: increased security, meeting regu-latory compliance, and improved productivity. ImplementingSSO would improve security risk by reducing authenticationcomplexity for end users, as well as reducing the burden ofpassword management for MIS. The implementation was seenas a simple back-end technology change that would appearseamless for the users. The staff was already accustomed toauthenticating to gain access to applications and this wouldbe no different.

Seeking to deepen our understanding of the SSO approach,the first author followed an SSO pilot project at a regional hos-pital. The aim of the study was to document the factors thataffected its adoption within the context of use. The ultimategoal is to better inform the design of usable authenticationsystems within collaborative healthcare work sites. While notwo hospitals are exact replicas of each other, all hospitalsmaintain some commonality of structure, environment, cul-ture, and purpose; therefore, many of the things identified inthis particular study will be relevant to other hospitals whoare trying to implement single sign-on mechanisms.

The choice to use a healthcare environment for this studywas motivated by the literature. Hospitals are high reliabil-ity and high liability environments. In this environment, ifsomething goes wrong it can be catastrophic; therefore, indi-vidual accountability is critical. As a result it is consideredan extreme environment; and as such, poses many chal-lenges to normal authentication that are not apparent in otherindustries. By selecting extreme cases, the aim is to amplifythe findings, thereby making the constraints, limitations, anddifferences easier to observe. This often helps expose theunderlying structures of the phenomena that are commonacross many diverse environments. The unique characteris-tics of a hospital make technology implementations difficult.This environment is extremely collaborative in nature with awide variety of workers – physicians, pharmacists, nurses, res-

piratory technicians, social workers, and physical therapists.Each of these has very different domain knowledge, profes-sional culture, and work practices. This diversity creates adata rich environment. The situated and socially organizedJournal Identification = IJB Article Identification = 2723 Date: July 2, 2011 Time: 3:6 am

i n f

xxx.e52 i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f m e d i c a lcharacter of cooperative work in this environment requires areflection on not only the tasks and activities that occur withinthe cultural framework and social context. It also requires acareful reflection on the practices and reasoning, which aredeveloped and warranted within this particular setting, andwhich systematically inform the work and interaction of thevarious roles with the technology [23].

3. Study design

Building on the existing research about security technologyimplementations is a challenge. The study of security usabilityissues is difficult to replicate in an experimental environment,and self-reported data is skewed because often what peo-ple say they do and what they actually do when it comes tosecurity is quite different [14,15]. To get a true understandingof security technology use, it is more helpful to take a sys-temic holistic approach accomplished by viewing the securitytechnology implementation in context [20,21]. For these rea-sons, this study took the form of a 15-month field study thatfollowed the entire systems development lifecycle from analy-sis (including vendor selection) through design, development,testing, implementation, and post implementation review.The results are presented as a case study. The primary datacollection techniques used were ethnographically informed –participant observation, contextual interviews, meetings, anddocument review. The decision to triangulate among theseis based on a desire to capture the interplay between for-mal and informal systems [24]. The strength of observationis the ability to discover discrepancies between what partici-pants say (and often believe) should happen and what actuallydoes happen. The observer is able to differentiate betweenthe formal work practices (what policy requires) with infor-mal or routine work practice (what is actually required tocomplete a task). Contextual interviews complemented theobservation and were open-ended, unscheduled, and oppor-tunistic. Usually these were brief (5–10 min) and done rightat the person’s work area as not to interrupt their routinework. Insight into the formal organizational structure, work-flow procedures, as well as the corporate culture that wasbeing promoted was obtained through document reviews oforganizational mandates, computer usage policies, trainingmaterials, and workflow protocols. The meetings and inter-view notes were transcribed immediately. The documents andtranscripts were analyzed using NVivo 6.0 qualitative analy-sis software. This inductive content analysis was guided by aGrounded Theory approach [25]. After a preliminary reviewand analysis of the data, formal questions were created toaddress and clarify specific issues with specific key personnelin various roles.

This single sign-on pilot took place in an organizationwhich will be referred to as General Hospital (GH) from thispoint forward. Using the American Hospital Associations hos-pital data, GH ranks slightly higher than the mean of allhospitals within its geographic region and throughout the

United States with regard to the normal hospitals measure-ment criteria of number of beds, discharges, and inpatientdays. Currently technology use for GH is rated as “moder-ate.” However, GH is progressively moving to a fully functionalo r m a t i c s 8 0 ( 2 0 1 1 ) xxx.e49–xxx.e61

electronic medical record (EMR). By moving toward a fullyfunctional EMR, GH would align itself with the overall nationalgoal of universal, portable electronic health records. To clarifythe distinction between EMRs and EHRs: EMRs are the legalrecordings of a patient’s visit to a medical provider and are theproperty of the provider. A compilation of the various EMR’smake up an individual’s complete electronic health record(EHR) [26].

Participants for this research project were a mix of bothclinical and administrative staff, as well as the ManagementInformation Systems group (MIS). While many studies in theliterature tend to focus on one role or department, we wantedto include a comprehensive sampling to ensure an adequatecross-section of individuals affected by the implementation.Clinical staff included physicians, nurses, technicians, radi-ologists, or those individuals who were directly involved inpatient care. Administrative staff included all other employ-ees; such as those in the billing offices, physicians’ offices,volunteer offices, and other “back office” administration.Every medical organization is a unique configuration of rou-tine roles, routines, and requirements; therefore, the lessonslearned about the SSO implementation at General should havea high degree of transferability to other organizations withsimilar configurations.

4. Case description

The following sections describe what we found during theexecution of the SSO project, focusing on the challengesencountered during its implementation. The analysis revealeda difficulty with the implementation of SSO in the clinicalareas. The content analysis suggested that SSO was prob-lematic in the collaborative areas because it affected theworkflow. In an effort to address the workflow issues with bothorganizational and technical workarounds, new security vul-nerabilities were inadvertently introduced. The clinical staffwas cognizant of these vulnerabilities and the ramificationson their professional identities and this created resistance tothe implementation. Following a discussion of these findings,a set of general recommendations for SSO implementations isoffered.

To adequately describe the environment before SSO, thefollowing is a vignette of what was observed in the EmergencyDepartment (ED). The network is already up and runningbecause the room’s computer is never turned off. The NurseMartin simply logs in to the Meditech application to begin doc-umenting her findings. Meditech is an integrated informationsystem used by the clinicians to document, track, and moni-tor ongoing treatment for a patient. Dr. Harris comes in andinterrupts her. They discuss the situation and work togetheron caring for the patient. Nurse Martin leaves to obtain somesupplies and Dr. Harris logs in to her own session of Meditechon the computer to check on the patient’s X-rays. She doesthis by simply minimizing Nurse Martin’s Meditech sessionand logging into her own session. When Nurse Martin returns,

they both walk toward the patient to continue their care. Nei-ther Nurse Martin nor Dr. Harris has logged off. When theyhave completed their work with the patient, Dr. Harris simplyleaves. As she does so, she glances at the overhead monitor toJournal Identification = IJB Article Identification = 2723 Date: July 2, 2011 Time: 3:6 am

i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f m e d i c a l i n f o r m a t i c s 8 0 ( 2 0 1 1 ) xxx.e49–xxx.e61 xxx.e53

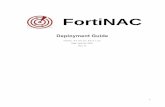

Fig. 1 – A high-level comparison of the authentication architecture before and after SSO implementation.

stastpcMmsawp

4

TvpSnubtrpiolahaSsftSncpwwmt

ee who her next patient is. She moves quickly as she noticeshe emergency room is beginning to get busy. Nurse Martinlso walks out of the room to obtain the medications pre-cribed. In the meantime Thomas, the admitting clerk, entershe patient’s room to complete the admitting process. He sim-ly does that by logging into the admitting application on theomputer. When Nurse Martin returns, she maximizes hereditech session and proceeds to do what is needed to docu-ent the administration of medication to the patient. When

he is done with her work, she logs off her Meditech session,nd Thomas returns to complete the admitting process, all thehile Dr. Harris has inadvertently forgotten to log off as she isaged on the loudspeaker and quickly exits.

.1. Project details

he single sign-on initiative started in October of 2006. As pre-iously stated there were several strategic imperatives for theroject, the first of which was to address security concerns.SO allowed greater audit ability of users on the organization’setwork while simplifying password management for theser. By using a single password, MIS believed that there woulde reduced risk from common user work-arounds for mul-iple, complex passwords, such as writing down passwords,eusing passwords, sharing passwords, or using easily guessedasswords. They purchased comprehensive single sign-on and

dentity management solutions from Novell, Novell SecureL-gin and Novell Identity Manager respectively. Recall thatogically all SSO technology works under the same premise:uthenticate to the network using one strong password andave access to all your applications without having to re-uthenticate to each one individually. Technically, however,SO vendor products differ significantly. The technology cho-en in this case was client-based. This design made it possibleor users’ credentials to be stored and retrieved from a cen-ral repository, simplifying administration. In addition, NovellecureLogin is an application-based SSO. As such, there iso need to alter the existing underlying infrastructure or theode of the applications to which it will authenticate. Theroduct uses software scripts to integrate the SSO capabilities

ith the existing applications. Novell Secure Login recognizeshen an application is calling for authentication and it auto-ates the process through its pre-defined scripts which maphe appropriate fields from the application to the user’s stored

credentials. While there are some pre-existing scripts avail-able for popular applications, a majority of the scripts had tobe custom coded.

Before the implementation of SSO, user authentication atGH facilities was tied to a job function, not a role or a specificperson. The users in the administrative offices were alreadyusing their unique user identity and password to log onto thenetwork. However, staff in the clinical areas used a generic idto log into the network; for example, Labuser1 and Labuser2.Once the network was up, however, other individuals access-ing an application that required authentication would thenuse their own unique identity and password to access a par-ticular application (Fig. 1).

In the new authentication process, each user must log ontothe network with their personal user id and password. Genericuser ids would be removed. However, once the user is on thenetwork, all applications are available to the user withoutthe need to authenticate to any particular application. If theuser launches an application and the application requires ausername and password, SSO intercepts the request for userauthentication and retrieves the user’s credentials, providesthe credentials to the application program, and access to theapplication is granted. This process happens seamlessly with-out the user ever being aware of what is happening.

To provide for more network control, the overarchingdesign requirement was that everyone using the organiza-tion’s network must log in with a unique individual userid. For the staff in the administrative areas, they werealready familiar with logging onto the network because thatis what they already did. For the staff that used a com-puter that was logged onto the network under a genericuser id, individual network authentication would be new tothem.

The deployment plan was carefully considered and a stag-gered department-by-department and ward-by-ward roll outplan was set. Administrative offices would be implementedfirst, as they would be the easiest to do. MIS recognized thecomplexity and difficulties the implementation would bring tothe clinical areas. To address the complexity, further require-ments gathering would be conducted for each specific clinical

area and a pilot implementation would be done on one ofthe nursing units. Feedback received from this pilot wouldallow them to make necessary modification before continu-ing.Journal Identification = IJB Article Identification = 2723 Date: July 2, 2011 Time: 3:6 am

i n f

xxx.e54 i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f m e d i c a l4.2. SSO affects collaborative workflow

The implementation of SSO in the administrative offices wentwell. Their physical environment, as well as the work environ-ment, was very different from the clinical areas. For one, eachadministrative staff member had his or her own computer.Even if they needed to share a computer for a particular pur-pose, their work was not time critical and could tolerate thetime lag of a brief log off/log in process. In addition, the usersin these offices were already familiar with using a network login as they already logged onto the network each morning withtheir personal id and password. If an individual did inadver-tently walk away from their computer, the threat would stillbe minimal as the physical location was secure. To access anyof the computers, an individual would have to pass througha closed door, often times with an administrative assistantsitting right at the entrance. For the administrative staff SSOwould provide them with great benefit without affecting theirnormal workflow. These users were looking forward to reduc-ing the burden of remembering many passwords.

Further investigation into the requirements for variousclinical areas, on the other hand, revealed a very differentsituation. The MIS team along with the Compliance Officervisited each diagnostic area (the Emergency Room, the Lab,the Oncology Lab, as well as the Radiology Department), in aneffort to understand their specific needs and concerns. Withthis further investigation it was clear that SSO would be prob-lematic for certain areas due to their high-collaborative needs.For example, in many of the diagnostic areas, different indi-viduals would have access to different information; however,all of that information would have to be viewed as a whole (atone time) in order to review patient data, schedule patients,and analyze test results. One oncology radiology techniciannoted the common need to compare historical diagnostic data,“We need to have the ability to pull up more than one imageand compare them side by side.” The director of the OncologyDepartment also felt that the computers in the shared workareas would be problematic in the SSO implementation. Hefelt that SSO would impact their work practices if they hadto log off and on with each user. He stated that the applica-tions used take quite a bit of time to open and shut down and“That would really slow us down.” He particularly felt that thephysicians would complain extensively and commented: “Youknow doctors; they are the most impatient people. They’re notgoing to want to wait for so and so to log off so they can login.”

As another example, the operating rooms were equippedwith computers that were used to document procedures. Thedocumenting nurse logs on at the beginning of a procedureand remains logged on until the end of the procedure. Even ifthere is a change in nursing staff, the first nurse to log ontothe system must remain logged onto the computer. It was thisway due to two factors: for one, during a procedure, the timelag necessary for one nurse to log off the network and anotherto log in could not be tolerated. In addition, the documentationapplication in use would lock the patient’s record if the patient

record was closed for any reason. The patient record could notbe reopened unless an administrator unlocked the record. Sounless the nurses could change identities without closing thepatient record, it would preclude them from using SSO. A nurseo r m a t i c s 8 0 ( 2 0 1 1 ) xxx.e49–xxx.e61

from the operating room noted: “First and foremost, you arenot going to get the nurse nor are they going to have the time,if there’s more than one in there documenting, to log off andthen log in with their own id.”

In the Labor and Delivery Department, the computersserved multiple purposes. Here again, one individual wouldlog onto the network or use their individual user id to log ontothe network. Once the network was up, the computer could beused for multiple purposes. Often the computer was used forfetal monitoring, in addition to being used by the clinicians todocument the patient’s medical data. While the monitor wasrunning, a nurse could log onto the Meditech application todo patient documentation. When they were done, they wouldlog off the application. All the while fetal monitoring was notdisturbed. These monitoring computers cannot be shut downto accommodate staff logins/logoffs. The nurse explained: “Itwould not be a good idea to have these as SSO because thenwhen a nurse leaves her shift, she would have to log off andthen someone would have to logon, and I don’t know what thatwould do to the fetal monitor.” In addition, these computersare in the patient’s rooms and once an individual logs onto thecomputer, their identity remains on that computer until theylog off. The nurses working in Labor and Delivery move frompatient to patient (room to room). Leaving an SSO-enabledcomputer logged on with their individual identity will leave alltheir applications vulnerable. The charge nurse commented

“The nurses may not like having their id on a particular PCbecause they won’t be able to monitor that PC all day longand they can’t log off. If it had SSO, then the individualwho logged in would have all their applications open on aPC that they cannot see and control all throughout the day.So someone else could get on that PC and work throughthat nurse’s user id.”

Due to these issues, the CIO decided that these areas wouldbe excluded from the SSO implementation. However, the piloton the nursing units would continue. The issues discoveredduring analysis were not insurmountable and workaroundswere developed to address them.

4.3. Workarounds to improve workflow createdsecurity vulnerabilities

MIS created technology fixes by modifying the Novell software.However, sometimes these fixes had unintentional conse-quences leading to an increase in security vulnerabilities.These are particularly well illustrated by two system modi-fications: the Ctrl-L and the Ctrl-Alt-L keyboard shortcuts.

The Ctrl-L function was created to address the need fortightly coupled collaboration between clinicians. For example,a physician and supervisory nurse were working together on apatient. The physician reviewing the EMR in Meditech consid-ered placing the patient in the hospital overnight. He wouldask the supervising nurse to check on bed availability. Beforethe SSO implementation the nurse and the physician coulddo that by simply logging into the applications they needed

on the same computer. With SSO, the physician would needto log off the application and log off the network. The nursethen would log on the network, and then log in to the appli-cation to check bed availability. Once a nurse has checked forJournal Identification = IJB Article Identification = 2723 Date: July 2, 2011 Time: 3:6 am

o r m a

ahmfwssfircAtsucwWrcWnw

tntqf

ccneicnoeanwFnuagci

i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f m e d i c a l i n f

vailability, he would have to log off and the physician wouldave to log on again to continue working. To address this, MISodified the Novell software to provide the Ctrl-L customized

eature. The Ctrl-L function would log the user off the net-ork, but that user would remain logged into their Meditech

ession. It then allows another individual to open a secondession of the Meditech application using their identity. Thisunction enhanced the workflow, as it would allow multiplendividuals to use the same computer. However, it had secu-ity ramifications as there were now two users on the sameomputer, but only one of them was identified to the network.

security vulnerability is created for the user that is identifiedo the network because all of their applications are now acces-ible without re-authentication. Thus giving the second usernauthorized access to all of the first authorized user’s appli-ations. Therefore, while use of the Ctrl-L hot key enhancesorkflow and collaboration, it creates a security vulnerability.hile this may not have been of great concern in most envi-

onments, in a medical environment where interruptions areommon, this presented a greater vulnerability to the user.ith SSO, the user would now have all their applications vul-

erable if they inadvertently moved away from their computerithout properly logging off.

The Ctrl-Alt-L function was provided to address the some-imes urgent nature of clinicians’ work. Clinicians, particularlyurses, needed to be able to save their data and log off ofhe network if they needed to walk away from their computeruickly. This slow process would be particularly troublesomeor the nurses, as reported by the nurse educator:

“This is a huge impact to nursing workflow. There needsto be a way to suspend a Meditech session without allow-ing access to GroupWise and Kronos [a calendaring andtime reporting system respectively]. I constantly have tosuspend my Meditech session in the middle of document-ing an assessment to assist a patient to the bathroom orto get pain medicine for another. The patients should nothave to wait for me to finish my documentation, log offMeditech and then the network, before responding to theirrequests.”

To address this workflow issue, MIS created a second spe-ial hot key, the Ctrl-Alt-L. This function would allow thelinician to quickly log off all applications, including theetwork, with one keystroke. While this modification wasffective in addressing the multiple logoff issue, the way it wasmplemented did not work well with the nomadic nature of thelinicians’ work. The functionality was enabled only on keyursing computers, most commonly on the shared computern wheels (COWs). It was not standardized across all comput-rs. For the nomadic clinicians, they computer that they couldccess when they came onto a unit was limited by availability,ot function. To the nurses and other clinicians a computeras merely a tool and they should all behave the same way.

or example, if a clinician needed a computer and one desig-ated for a nurse supervisor was available, then that would besed. Therefore, a consequence of this configuration was that

clinician might use the Ctrl-Alt-L key thinking they were log-ing off, when in fact they were not because they were on aomputer that did not have this functionality. If the cliniciann their haste did not hang around long enough to verify that

t i c s 8 0 ( 2 0 1 1 ) xxx.e49–xxx.e61 xxx.e55

they were in fact logged off, this created a security vulnera-bility. With SSO this vulnerability was even more troublesomebecause all the applications that the user had rights to wouldnow be accessible without further authentication.

4.4. Secondary uses of passwords

SSO does not operate in isolation, but rather in a rich ecology ofsecurity practices, both digital and physical. In this case pass-words served multiple purposes. They were not only used foraccess control to the network, they were used as access controlto physical environments, as well as being used as a digital sig-nature. For example, at GH when a patient was administeredinsulin, a second nurse was required to review and confirmthe administration of the medication for the nurse performingthe task. The second nurse did this by using their Meditech idand password as a digital signature. Therefore, even thoughSSO alleviated the need for the nurse to remember theirid/password to authenticate to the Meditech application, thenurse still needs to remember the application’s id and pass-word for medication co-signing purposes. However, now it waseven more difficult to remember the password because it wasonly used on a sporadic basis. In addition, there was still a pro-liferation of passwords for many other functions not includedin the SSO implementation such as access to medical supplycabinets, access to the narcotics room, and the dispensing sys-tem. Each of these functions also needed unique passwordsfor access. These passwords were outside of the network andcould not be controlled by the SSO system; therefore, the dif-ficulties of managing multiple passwords still existed for thenursing staff.

4.5. Security vulnerabilities and current culture createconcerns for SSO users

Everyone in GH shared a common concern for patient pri-vacy. This was a shared cultural understanding. However, thiswas borne out differently based on the constraints of differ-ent roles (e.g., administration vs. nurses vs. lab technicians).While everyone agreed on the value, there was tension in theactual practice; and this was particularly true for clinicians.The concern for patient confidentiality and abiding by HIPAAregulations was always a concern for the clinicians. As care-givers, they understood the need for patient privacy. They werecognizant of what they needed to do to preserve it, and thehospital continuously reminded them of this through policiesand training. One nurse explained: “. . . that’s important if thepatient doesn’t want her condition to be known by others.”Another stated: “We go through a required HIPAA training ona yearly basis, where we have to sign that it was completed.”The ramifications of not following policy were also known, as anurse remarked “They’ve let some contract nurses go becausethey didn’t complete their HIPAA training.”

The clinicians were also cognizant of the need to use theirown identity in any system work that they do. They openlystated that they did not want to enter their patient care

documentation using another’s identity because they are con-cerned about their own medical licenses. One registered nursenoted, “It’s important to use your own user id, because it’slike your signature. It’s my professional license, and I want toJournal Identification = IJB Article Identification = 2723 Date: July 2, 2011 Time: 3:6 am

i n f

xxx.e56 i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f m e d i c a lprotect that.” Another agreed, “The rule is: Your id, your doc-umentation. I don’t want anyone to document with my id.” Athird confirmed, “My work only is supposed to go under my id.”

General Hospital’s Information Security Program Policystates that “in accordance with HIPAA compliance require-ments the hospital provides each computer system user witha unique ‘USER IDENTITY’, and system users are not permit-ted to share and/or disclose their user identity.” This stance isreiterated again in the HIPAA training module that the nursesare required to complete before they are allowed to work atGH. In summary, it states:

“Your user identity is what is used to monitor your activityon the system.

Do not leave yourself signed on to a computer and thenwalk away without signing off.

You are responsible for any activity that occurs under youruser identity.

Your user identity appears on audit reports which are fre-quently monitored.” [Source: HIPAA training module via GHintranet]

However, even with these good intentions and clear train-ing, the workarounds to the policy emerged when cliniciansfelt the situation warranted it. For clinicians, policy and workpractice did not always coincide as the nurse educator stated:“. . . the easiest way for clinicians to work is probably not quitethe way policy says it is working because there are all thesesecurity and privacy concerns which are not necessarily theirpriority when they are just thinking: I just want to get thisdone. I just want to help my patient.”

Remarks by nurses similarly allude to the contentious sit-uation:

Nurse Smith - “I can’t tell you how many times I have hadto just document under someone else’s ID.”

Nurse Harvey - “Sometimes, I just come here to quickly putin my patient’s information, and I just use whatever sessionis up. I can’t take the time to pull up my own session.”

Nurse Martin - “Physicians will leave the Meditech Sessionopen for another physician as a professional courtesy.”

Lab Director – “Sometimes I just need to come in here andlook up a result very quickly, and I just say ‘can I get in herea minute’.”

Understanding the way SSO worked and knowing howtheir environment was very unpredictable, clinicians real-ized that SSO would create security vulnerabilities. The nursesupervisors were particularly sensitive to this as they hadaccess to data and applications on their systems that they didnot want to be accessible to all of the staff, including theiremail communications, staff performance evaluations, nurs-ing schedules. One noted, “I’m the supervisor, I don’t want justanyone getting on my computer and sending out an email withmy name on it.” The interaction of the SSO technology (with

the perceived increase in vulnerability), within the high reli-ability and high liability clinical environment caused concernamong those that used the technology because the impli-cations of the corporate culture of accountability were wello r m a t i c s 8 0 ( 2 0 1 1 ) xxx.e49–xxx.e61

understood. For the users, a breach in data access could resultin the loss of their job, as well as their professional license.

4.6. MIS misunderstood how SSO would impactworkflow

MIS took an understandably technological deterministic viewof the implementation. SSO would be a simple networkUI upgrade. However, this became very complicated whenenmeshed with social practice. This was particularly obviousin the fact that the most important behavior in an SSO envi-ronment is logging off, and that behavior was not guaranteedin practice. MIS realized that SSO would not be effective if thecurrent log on/log off behavior did not change. This was statedin the project charter: “If a user leaves a computer withoutlogging off, multiple applications will be able to be accessed.If this is not taken into consideration especially for the clin-ical environment, the advantage and usefulness of the newtechnology will be questioned.” As just discussed, users wereadmonished to not leave their computer logged on and unat-tended during yearly HIPAA training, initial Meditech training,and policy documents. However, it was generally known thatthis was a regular occurrence, particularly in the clinical areaswhere users really could not always control when they wouldleave their computers or how long they would be away. Intours of the Lab, Radiology, and nursing units, the concern wasraised that work practices were not matching organizationalpolicies, and SSO would be mechanistically enforcing thosepolicies. The project manager recognized this and stated: “Wefound that in a lot of areas that, you know, they were sharingIDs. It was easy for them. Now they are being forced to workthe way they should have been, anyway.”

The same comments concerning practice vs. policy werereiterated many times. In a conversation between MIS, thecompliance officer, and a nurse, the nurse questioned: “So thedoctor is going to have to remember to suspend his sessionand do Ctrl-L or the next doctor or whoever comes up behindhim is going to look up under him?” The MIS representativereplied: “That’s right. Because that’s no different than whatthey should be doing today. They should be doing that any-way.” This was then confirmed by the compliance officer whoreiterated “I mean, they really should be working this way,today, without single sign-on.” This tension between policyand practice was amplified when SSO went live. The MIS groupclaiming that the clinicians must start working as policy statesthey should, and the clinicians defending that they do for themost part, but sometimes they simply cannot.

These case vignettes detail the implementation of the SSOin select areas. They illustrate the complexities of the technol-ogy within the collaborative clinical environment. However,while the implementation did not go as smoothly as planned,it was not a failure. Throughout, the MIS group was able toreflect upon the situation, garner lessons learned along theway, and then act upon them.

5. Discussion

One of the more compelling stories emerging from the datastarts with the difficulties in retrofitting an individually based

Journal Identification = IJB Article Identification = 2723 Date: July 2, 2011 Time: 3:6 am

o r m a

aeobmpuefeMeTw

ovmaefmawniiiiwe

iutgwoeeMiWiai

matiwetuntfao

i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f m e d i c a l i n f

uthentication mechanism within an extremely collaborativenvironment. As previously noted, the vision for single sign-n was that it would be easy to implement and appreciatedy its users. SSO would help facilitate password manage-ent not only for users, but for MIS as well. However, as the

roject unfolded, the collaborative needs of the clinical staffnearthed tensions in this implementation. While SSO wasffective in the administrative offices, it was not a good fitor collaborative areas. The workflow, activities, and physicalnvironment of the clinical areas were considerably different.edical work is based on sharing data and materials; how-

ver, authentication cannot be shared, it must be personal.he need for individual authentication contradicts with theay most medical work is done.

SSO was problematic for additional reasons as well. Forne, it affected the workflow of the clinical user while not pro-iding a perceived added benefit for that user. As previouslyentioned, many of the nurses used Meditech as their only

pplication on the network that requires a password. How-ver, they still managed a host of passwords that were requiredor job duties off the network. These passwords could not be

anaged by the SSO system. SSO did not solve all of theiruthentication needs, and as a result, it actually made pass-ord management more difficult. So, in summary, SSO didot provide a clear benefit to the clinical user, and instead

mpeded workflow and created increased security vulnerabil-ties. Clinicians often fail to embrace a technology if they feelt interferes with their workflow, takes too much time, andf they do not see its relevance to their practice [27,28], so itas not surprising in hindsight that there would be limited

nthusiasm for the SSO implementation.MIS tried to address the workflow issues by implement-

ng technology fixes. However, sometimes these brought aboutnintentional consequences. Their continued effort to moveoward a more effective secure environment (organizationaloal), the design choices (workarounds) made to address theorkflow issues (user goals) actually subverted the strengthf the security mechanism itself and in the end made thenvironment less secure and more difficult to maintain. Forxample, the Ctrl-L function that allowed users to lock theireditech application, log off the network, and then another

ndividual could log onto the network on the same computer.hile this appeased workflow, it created a security vulnerabil-

ty. The organization at this point needs to assess whether thessurance level needed is compromised by the workaround orf it can be tolerated to appease workflow issues.

Another factor that added to the troubles of the SSO imple-entation was the mismatch between organizational policy

nd the realities of SSO in the context of routine work. Whilehe formal policies were very strict in their verbiage concern-ng computer log in and data access, the work environmentas not compatible with the formal work policies. Clinicians

ngaged in several workarounds to these policies in an efforto get the work done. For example, the informal practice ofsing a generic ID to log onto the network was specificallyot allowed in policy, but it was a generally known fact that

his was a regular practice as it facilitated the workflow. Theact was that if the immediacy of the moment prescribed that

clinician should simply use an available application with-ut re-logging on with their unique user ID, then that is what

t i c s 8 0 ( 2 0 1 1 ) xxx.e49–xxx.e61 xxx.e57

was done. When formal work policies and informal work prac-tices did not coincide, it created tension in an already hecticenvironment that was particularly sensitive to accountabilityand consequences. The complex nature of the environmentcreated novel circumstances with each passing moment, andwhile intentions were where they should be, the reality didnot always support those intentions. Technologies used in col-laborative environments must allow for situational awarenessbecause individuals make decisions on how to act based uponthe situation they are confronted with at the moment [29]. Inthis case the cultural environment was a strong force in theimplementation that was not anticipated. The hospital cultureemphasized accountability and consequences; the environ-ment was unpredictable and SSO created vulnerabilities. Thistension impacted the entire implementation.

In this case the technological deterministic stance takenby MIS presented an oversimplified perspective of the inter-action of the SSO technology and its implications within thework environment. The problems encountered in the imple-mentation were not simply a mistake in systems analysis; itwas the complex socio-technical interplay that was underes-timated. Technology is not neutral; it has consequences forthe organization as well as for the individual [30]. Contextmatters, and the sensitivity of the context within this case isstrong. The differences in the contextual settings are instru-mental, as they set up the initial conditions under which SSOwould be implemented, as well as the conditions within whichit would interact. Medical environments, such as GH, presentchallenges to normal authentication that are not apparent inother industries [10,12]. The biggest difference between a clini-cal environment and other industries is that access to patientinformation can be critical at times. While the organizationstrived to increase control of network access, the cliniciansneeded unencumbered access to data to perform their workadequately.

The extreme nature of this environment calls for greateraccountability. This is another critical contextual element– that clinicians need to protect their professional identitybecause its loss has grave ramifications. While authenticationmechanisms are aimed at access controls to organizationaldata, they have personal implications for its users. Thereforethere is a distinctive need for a high trust value between theclinicians and MIS’s implementation of SSO. Trust require-ments for an SSO authentication technology are directlycorrelated to the user’s perceived risk exposure and this trustis necessary for user acceptance of the technology [31]. At GH,the clinicians were concerned about the risks that SSO posedto their professional identities and because of this fear theyopenly resisted the implementation. Resistance, in relation toIT implementation, is a generalized opposition to the tech-nology created by the anticipated adverse consequences ofthe technology, not by the technology itself [32]. In this casethe resistance was not caused by the new SSO authenticationmechanism, because the staff were used to authenticating.It was the perceived changes that would occur with theimplementation of SSO that was causing the concern. As an

example, prior to SSO implementation, a physician wouldleave the Meditech application open for the next physician as aprofessional courtesy. Under SSO, this was still possible; how-ever, a physician might think twice about doing so becauseJournal Identification = IJB Article Identification = 2723 Date: July 2, 2011 Time: 3:6 am

i n f

xxx.e58 i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f m e d i c a lof the personal ramifications. There is an implied level oftrust between clinicians and physicians as they are united inthe goal of quality patient care. SSO could create a wedge inthis trust with its vulnerability implications. Once logged ontothe network, a clinician may not so easily step aside to letanother clinician quickly check on a test result under theiridentity.

To effectively address this socio-technical balance for effec-tive security systems requires taking a systemic and holisticapproach [20]. A hospital environment is a multi-faceted envi-ronment. Its complexities and interdependencies demandexploration from the frame of reference of those who aredirectly involved in the process as the situation emerges.There has been abundance of security research focused onthe technical aspects of authentication mechanisms andan increasing amount of work on their usability [12,13,15].However, improving the overall usability of authenticationsystems, and hence the effectiveness of the technology itselfis not enough; the context within which the technology isused will greatly affect its usefulness [21,33]. In this case thedecision to use an ethnographically informed field study wasextremely effective in correlating the user’s true perceptionsand their actual behavior. We were able to ascertain a clearerunderstanding of the real life situation, causal relations, andunforeseen and unintended consequences of the implemen-tation. While the CIO, the MIS staff, as well as the vendorclaimed that the SSO implementation was a success, fromobservation, a different story was evident. While technically itsucceeded, operationally it suffered. Practitioners were expertat performing work arounds when things stood in the way ofthem performing their jobs. Work arounds to SSO authentica-tion were not an exception. Clinicians still walked away fromtheir computer without signing off – because they had to. Theystill shared logins in time of necessity and they shared loginswhen collaborating. So in essence, a review of the merits ofthe technology for usability and functionality may have beenuseful; but when the technology was placed in context of aclinical environment, it lost it applicability. The only way thisinformation could be ascertained is by getting a dynamic viewof the interplay of the technology within the environment, andthe iterative feedback when it is actually used on a day to daybasis.

5.1. Organizational implications

As a start of any security implementation the organizationmust determine the level of assurance they want to achieveso they can effectively choose and implement security mea-sures to achieve that specified level. If workarounds to addressusability are implemented for a particular area, the organi-zation needs to reassess whether the predefined assurancelevel is compromised by the workarounds or whether it canbe tolerated. One of the reasons for implementing SSO at GHwas to increase security and productivity; SSO would man-age user passwords and password resets would automaticallybe resolved. However, the findings suggest that while there is

added benefit to the administrative areas, there is no real ben-efit to the collaborative clinical areas. In addition, there aresignificant soft costs to these clinical areas due to the impacton workflow and employee dissatisfaction.o r m a t i c s 8 0 ( 2 0 1 1 ) xxx.e49–xxx.e61

In addition, SSO was part of a larger risk management pro-gram, with one of its goals being an effort to meet regulatorycompliance standards for auditing. However, this may be prob-lematic as the environment in the collaborative areas raiseidentity issues. For example, if SSO was not used properly,whether it was intentional or unintentional due to contex-tual circumstances, one could not be completely sure who wasactually working on a particular computer. While the com-puter could be uniquely identified by the IP address and theindividual logged onto the network could be uniquely iden-tified; the person actually using the computer may not bethe person who was authenticated leading to plausible deni-ability. While there is policy against this, the physical workenvironment is such that policy cannot always be followed.The questions are: If one cannot prove who actually accesseda particular record to any legal standard, then will it meet reg-ulatory compliance? If it cannot meet regulatory compliance,then is it worth the effort and cost to implement?

Organizations need to be cognizant of the fact that neitherchanging people, nor changing technical features of a systemwill increase implementation success if the initial conditionsupon which the technology is introduced are not conduciveto the implementation [34]. In this case the characteristicsof the clinical areas of being collaborative, high-liability, andhigh reliability must be acknowledged. Placing SSO technologyin this environment with its perceived increased vulnerabilitywill be problematic. While there are policies in place to man-date certain behaviors that would eliminate the vulnerabilitySSO presents, in the clinical environments these behaviors arenot evident within the work practices, nor can they be guaran-teed. In most all system implementations, the fact is that youcan never fully predict user behavior prior to the actual imple-mentation; therefore, it is important to have a mitigation planin place.

5.2. System design implications

Recall from the case that MIS did a fairly good job at therequirements gathering; the right people were consulted,the right data collected, the right methods used. However,there were several missteps and misjudgments concerningthe implications of the changes that SSO would bring. Thelargest challenge was not fully recognizing the role of SSOwithin the cultural context of the daily work, the people,and the organizational policies. MIS focused on the tech-nological functions of the system and underestimated thesocial design changes that were necessary. While they didacknowledge the social implications and changes the imple-mentation might bring; they did very little engineering ofthe social components to address them. This may be due inpart because the standard requirements analysis process doesnot allow for it. Traditional methods of requirements analy-sis are focused on capturing the basic user, system, and dataneeds. However, they do not allow for a comprehensive viewof the contextual environment with the technology in play.The dynamics between social and technical change vary in

different contexts. This necessitates an iterative approach ofmultiple phased pilots, careful observation, and active partic-ipation from all user groups. The MIS team at GH was headingin the right direction with their approach, and was able toJournal Identification = IJB Article Identification = 2723 Date: July 2, 2011 Time: 3:6 am

o r m a

cWedwa

robtwiloicfictetactSt‘tb[S

mtrdeatccitiausfstaoishOtcc

i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f m e d i c a l i n f

atch many of these problems before they became disastrous.hile this additional work may have been seen as an unnec-

ssary extra cost, the project could have done irreparableamage to the trust between employees, the efficiency of theirork practice, and ultimately patient care. This was thankfully

verted.This analysis of the use of single sign-on in a collabo-

ative environment has several implications for the designf authentication technologies within healthcare settings,ut also it suggests broader issues. So far, we have arguedhat the SSO authentication mechanism as a simple soft-are component that led to considerable usability problems

n the routine work in the GH clinical areas. However, theog in mechanism alone cannot be faulted as the root causef these problems. It was just a minor part of a complex

nformation system. While the Novell Secure Login appli-ation initially fit the backend information architecture andt well in the administrative offices, it did not support theollaboration needs of its clinical users for whom the sys-em worked under normal conditions, but failed in routinelyxceptional conditions. These could be in emergency situa-ions when unencumbered access to patient data is criticalnd when an individual transitions from individual work toollaborative work. The reality is that the talented staff couldransition effortlessly, while the technology could not. [23].SO, the key to more than one application in this switch,hen becomes a hindrance rather than a help. It keeps thestorefront open’, increasing security vulnerabilities. The needo transition from individual work to collaborative work andack again has consistently been a design issue for CSCW

35] and continues to be an issue for authentication withSO.

This problem could be addressed with the increased use ofobile devices where each individual could control the data

hey have access to and share that data with their collabo-ators. For example, the nurse would pull up the data on hisevice, the physician on hers. They could then simply viewach other’s data that they are entitled to view/update. Inddition in CSCW research, it is known that individuals needo dynamically control information access depending on theircumstances at hand [29]. While technology at this pointannot determine these nuanced needs automatically; if eachndividual had their own mobile device, the individual couldhen control with whom they share and when. Some interest-ng initial research into these enabling technologies involvesn RFID-tagged pen (actually a pointing device) to identify theser [12]. This would allow each individual to work on theame document at the same time while individually identi-ying each user. The problem of consistently logging off wouldtill exist in this environment. However, physical system con-rols would now be in place to fortify the logical access controlsnd administrative controls. As we saw in the administrativeffices, physical controls did alleviate some of the vulnerabil-

ties when a user forgot to log off of their workstation. Theseame physical controls could be added if each individual userad a mobile computer that they were physically controlled.

f course mobile devices have their share of difficulties in thisype of environment, but it would be interesting to see if theyould alleviate some of the difficulties in individual authenti-ation in collaborative areas.

t i c s 8 0 ( 2 0 1 1 ) xxx.e49–xxx.e61 xxx.e59

6. Conclusion

Single sign-on is a simple means of managing passwords andauthenticating to varied applications for users. Technicallythe SSO approach seems like a viable solution to a simplepassword management problem. In reality the problem ismuch more complex. There are a multitude of forces exertingtensions on the implementation. These tensions stem fromconflicting and oftentimes stringent requirements from thedifferent stakeholders; the hospital wants quality patient care;HIPAA wants patient privacy preserved; clinicians need easyaccess in a timely manner to provide quality care. From theanalysis of our data, we found SSO to be problematic in collab-orative environments and ineffective in bridging collaborationand individual authentication. There appears to be a numberof mismatches between the SSO vision and the realities of rou-tine work. SSO technology does not recognize the shift fromindividual work to collaborative, while causing disruption inthe daily workflow. The log-in procedures do not in any senserecognize the nomadic, interrupted, and cooperative nature ofmedical work. The features that make SSO strong in normalenvironments become a hindrance in collaborative environ-ments by increasing security vulnerabilities.

We do not claim generalizability of our findings to all hospi-tals. However, we have provided a detailed illustration of whathas happened in one and provide opportunities for transfer-ence to other similar settings. Additionally, lessons learnedfrom this research can be applied to future research into infor-mation security-related fieldwork, and to the future designsand evaluations of authentication mechanisms.

6.1. Beyond SSO

The scenarios described in this study are not drastically dif-ferent from those as described in the work of other healthcareresearchers. Clinical work is universally nomadic, chaotic, andinterrupt driven. The need for collaboration will always bea critical part of the environment. The difference today isthat technology has taken on a very critical supportive roleto the staff’s daily work tasks. As technology use increases,so must the controls increase on patient data confidentiality.However, the time-critical constraint in this high-reliability,high-liability environment compounds security technologyimplementation issues.

While this study concentrated on an SSO authenticationmechanism and the difficulties that were presented in itsimplementation, these findings are not just pertinent to SSOauthentication. Biometrics, smart cards and proximity devicesare all making inroads in healthcare. As these technologiesadvance, each promises greater security and ease of use. How-ever, each presents their own particular set of issues whenplaced in context. For example, proximity devices can helpclinicians easily log on and automatically log off when theywalk away. However, these devices may prove problematic inthe clinical areas where proximity boundaries are difficult to

define. A high-density of workers, such as in an operatingroom, causes dynamic overlaps at a granularity not yet inter-pretable by our sensor networks. Biometrics devices can helpclinicians easily log on, but does not help with the problemJournal Identification = IJB Article Identification = 2723 Date: July 2, 2011 Time: 3:6 am

i n f o r m a t i c s 8 0 ( 2 0 1 1 ) xxx.e49–xxx.e61

r

Summary pointsWhat was already known:

• Authentication is primarily a technical problem. Thisis a network operating system (NetOS) issue with littlecontextual impact – one solution works most places.

• Individual authentication is essential for the audittrails required by increase security regulations. Stan-dard methods work across all industries (e.g., financial,retail, healthcare).

• Single sign-on authentication approaches improvesecurity by increasing user compliance through moreusable software.

• For collaborative technologies to be effective, tech-nology must be flexible and be able to adjust to thesituation.

• Usability of security technology is important for assur-ing proper use and proper assurance.

What this study added:

• Authentication is actually a complex socio-technicalproblem. The co-evolution of technical interventionand social practice ensures that all implementationswill be meaningfully different. Understanding contex-tual factors is critical.

• In some contexts individual authentication may beneither desired (e.g., access by function, such as labequipment) nor possible (e.g., time critical, heavily col-laborative settings such as an ED OR).

• In some work environments, SSO implementationsmay actually decrease security through increasedreliance on work-arounds and less usable softwareinterfaces.

• Single sign-on technology negatively affects the work-flow in collaborative areas.

• There are significant add-on costs to adjust single signto work in the collaborative areas.

• Single sign-on introduces greater vulnerabilities in col-laborative environments.

xxx.e60 i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f m e d i c a l

of automatically logging off if the user forgets to do it. Tech-nology advances, in turn, have also brought about changesin the environment. For example, the influx of more mobiletechnology will allow a one-to-one user-computer ratio simi-lar to that of the administrative worker, easing collaborationneeds as each individual can pull up the information theyneed. In addition, this may eliminate the need for one pieceof equipment recognizing the transition from individual workto group work, as each individual will be authenticated totheir personal device. Each of these technologies when imple-mented will affect the environment within which they will beused, and the environment will in turn affect the technologyimplementation.

This case study is indicative of the need to take a moresocio-technical approach to security systems design. Whenmaking technology design choices, designers must alwaysaddress the environment within which the technology will beused, be sensitive to the complex co-evolution of sociotechni-cal systems, and be prepared to iterate on their designs.

Authors’ contributions

Dr. Rosa Heckle was the principle investigator and primaryauthor.

Dr. Wayne Lutters was a co-investigator and co-author.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

e f e r e n c e s

[1] T.C. Rindfleisch, Confidentiality, information technology andhealth care, Communications of the Association ofComputing Machinery 40 (1997) 93–100.

[2] M.J. Succi, Z.D. Walter, Theory of User Acceptance ofInformation Technologies: An Examination of Health CareProfessionals. Hawii International Conference on SystemSciences, Hawaii, IEEXplore, 1999.

[3] W. Hersh, Health care information technology progress andbarriers, Journal of the American Medical Association 202 (8)(2004) 2273–2274.

[4] R. Rada, Privacy and Health, Roy Rada, 2005.[5] J. Slutsman, K. Nancy, J. McGready, M. Wynia, Health

information, the HIPAA privacy rule, and health care: whatdo physicians think, Health Affairs 24 (3) (2005) 832.

[6] 104-191, PUBLIC LAW, Health Insurance Portability andAccountability Act of 1996, in: 104th Congress, 1996.

[7] W.J. Orlikowski, The duality of technology: rethinking theconcept of technology in organizations, OrganizationScience 3 (3) (1992) 398–427.

[8] V.L. O’Day, D.G. Bobrow, M. Shirley, The Socio-technicalDesign Circle, 1996.

[9] J. Grimson, W. Grimson, et al., The SI challenge in healthcare, Communication of the ACM 43 (6) (2000) 48–55.

[10] S.V. Pellissier, et al., Effective Authentication in a Medical

Environment. A. IPT, U.S. Army Medical Research andMateriel Command, Frederick, MD, 2001.[11] R. Rada, Health Information Security, HIPAA HypermediaSolutions Limited, 2003.

[12] J.E. Bardram, The trouble with log in: on usability andcomputer security in ubiquitous computing, Personal andUbiquitous Computing 9 (6) (2005) 357–367.

[13] A. Adams, M.A. Sasse, Users are not the enemy: why userscompromise computer security mechanisms and how totake remedial measures, Communications of the ACM 42(12) (1999) 41–46.

[14] A. Sasse, S. Brostoff, et al., Transforming the “weakest link”:a human–computer interaction approach to usable andeffective security, BT Technical Journal 19 (3) (2001) 122–131.

[15] L.F. Cranor, S. Garfinkel, Secure or usable? IEEE Privacy &Security 2 (5) (2004) 16–18.

[16] D. Weinshall, S. Kirkpatrick, Passwords you’ll never forget,but can’t recall, in: ACM Conference on Computer Human

Interaction, Vienna, Austria, 2004.[17] J.B.A. Yan, et al., Password memorability and security:empirical results, IEEE Privacy & Security 2 (5) (2004) 25–31.

Journal Identification = IJB Article Identification = 2723 Date: July 2, 2011 Time: 3:6 am

o r m a

i n t e r n a t i o n a l j o u r n a l o f m e d i c a l i n f[18] M. Berg, Implementing information systems in health careorganizations: myths and challenges, International Journalof Medical Informatics 64 (2–3) (2001) 143–156.

[19] M.S. Ackerman, The intellectual challenge of CSCW: the gapbetween social requirements and technical feasibility,Human-Computer Interaction 15 (2000) 179–203.

[20] L. Yngstrom, A holistic approach to IT security, in: J. Ellof, S.von Solms (Eds.), Information Security – The Next Decade,IFIP SEC’95, Chapman & Hall, London, 1996.

[21] A.S. Patrick, A.C. Long, et al., HCI and security systems, in:CHI ‘03 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in ComputingSystems, ACM Press, Ft. Lauderdale, FL, USA, 2003.

[22] HIMSS, 2006 Himss Leadership Survey – Trends inHealthcare Information Technology, September 2006,Available online: http://www.himss.org/2006survey/docs/Healthcare CIO key trends.pdf.

[23] C.C. Heath, P. Luff, Collaboration and control: crisismanagement and multimedia technology in LondonUnderground line control rooms, Journal of ComputerSupported Cooperative Work 1 (1) (1992) 24–48.

[24] M.Q. Patton, Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods,Sage Publications, 1990.

[25] A. Strauss, J. Corbin (Eds.), Grounded Theory in Practice,Sage Publications, London, 1997.

[26] D. Garets, M. Davis, Electronic Medical Records vs. Electronic

Health Records: Yes, There is a Difference, A HIMSSAnalytics White Paper, HIMSS Analytics, Chicago, IL, 2006,Available online: http://www.healthstik.com/downloads/WP EMR EHR.pdf.t i c s 8 0 ( 2 0 1 1 ) xxx.e49–xxx.e61 xxx.e61

[27] C. Bourret, Data concerns and challenges in health:networks, information systems and electronic records, DataScience Journal 3 (2004) 96–113.

[28] J.S. Ash, D.W. Bates, Factors and forces affecting EMR systemadoption: report of a 2004 ACMI discussion, Journal of theAmerican Medical Informatics Association 12 (1) (2005)8–12.

[29] L.A. Suchman, Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem ofHuman–Machine Communications, Cambridge UniversityPress, Cambridge, UK, 1987.