Teacher Training Matters: The Results of a Multi-State Survey of Secondary Special Educators...

Transcript of Teacher Training Matters: The Results of a Multi-State Survey of Secondary Special Educators...

Transition Training Matters 1

RUNNING HEAD: TRANSITION TRAINING MATTERS

Teacher Training Matters:

The Results of a Multi-State Survey of Secondary Special Educators Regarding Transition from

School to Adulthood

Mary E. Morningstar

University of Kansas

Debra Benitez

WestEd Inc.

Final Manuscript as Accepted Final Published as:

Morningstar, M. E., & Benitez, D. T. (2013). Teacher training matters: The results of a multistate survey of secondary special educators regarding transition from school to adulthood. Teacher Education and Special Education, 36(1), 51-64.

Transition Training Matters 2

Teacher Training Matters: The Results of a Multi-State Survey of Secondary Special

Educators Regarding Transition from School to Adulthood

Since 1990, and with subsequent amendments in 1997 and 2004, the transition provisions

of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) have been a strong impetus for special

educators to assume a coordinated approach to delivering transition services. The mandate

contains language identifying special education teachers as having primary responsibility for

overseeing the planning and facilitation of school to adulthood transitions. Despite such

legislative mandates, students with disabilities continue to face postschool outcomes in which

they are unprepared and unsuccessful (Newman, Wagner, Cameto, & Knokey, 2009). One

reason students with disabilities face such challenges may be due in part to secondary special

education teachers’ feeling unprepared to plan for and deliver transition services (Li, 2004;

Wolfe, Boone, & Blanchett, 1998). Effectively preparing personnel requires providing training

on specific knowledge and competencies often beyond what is included in most special

education teacher preparation programs (Anderson, Kleinhammer-Tramill, Morningstar,

Lehman, Kohler, Blalock & Wehmeyer, 2003). Special education teachers have reported a lack

of knowledge of transition competencies, and that this hinders their abilities to implement

effective practices (Blanchett, 2001; Knott & Asselin, 1999). Consequently, teachers who are

unprepared to plan and deliver transition services may be contributing to poor outcomes for

students with disabilities.

Given the changing roles of secondary special educators, it stands to reason that teacher

education programs would respond accordingly. Unfortunately, this has not yet proven to be the

case. In fact, findings from a national survey of special education personnel preparation

programs revealed that less than half of the special education programs offered a stand-alone

Transition Training Matters 3

course devoted to transition (Anderson et al. 2003). Whether special education teacher education

programs offer transition content and coursework is often dependent on state licensure

requirements as well as federal and state funding and incentives promoting specialized content.

Personnel development has been recognized as a central strategy for improvement among state

educational agencies (Blalock et al., 2003), yet clear guidance has yet to emerge for ensuring

high quality methods.

Implementing transition practices. Since all secondary special educators should be

involved in transition planning, it is critical that they possess core knowledge and skills to enable

them to effectively plan and deliver services. However, research findings over the past decade

indicate teachers are well aware of whether or not they have acquired in-depth transition

knowledge (Blanchett, 2001; Li, 2004, Wolf et al., 1998). Possessing limited knowledge and

skills impacts the use of effective practices, in that teachers who are not confident of their

transition skills are less likely to implement transition activities (Benitez, Morningstar & Frey,

2009).

In terms of actual practices, special education teachers have reported possessing a general

understanding of transition planning and mandates. Teachers have rated their level of

involvement in transition and IEP planning as moderate to high (Knott & Asselin, 1999).

Almost a decade later, a national study found similar results. Teachers rated being most prepared

to implement transition planning. However, secondary special education teachers were less likely

to implement activities in other domains (e.g., transition assessment, interagency collaboration,

transition-focused curriculum and instruction, and instructional planning, Benitez, et al., 2009).

Such findings suggest that typical teacher education programs have armed secondary special

educators with the skills needed to plan, but not deliver transition services.

Transition Training Matters 4

Limited transition training. Most secondary special educators report their transition

training was on-the-job, rather than through comprehensive teacher education (Greene &

Kochhar-Bryant, 2003). State priorities for transition personnel development and training can

impact the acquisition of transition competencies among practicing special educators. The

current state of transition professional development is illustrated by a lack of clear policies as

well as limited systems for planning, delivering and evaluating professional development

(Morningstar & Liss, 2004). In addition, the field has yet to agree on the critical content for

transition professional development; with most training focused on discrete knowledge and skills

outside the broader context of secondary educational systems (Morningstar & Clark, 2003;

Morningstar, Gaumer & Noonan, 2009). In addition, little effort has been placed on teaching

emergent evidence-based interventions or systems-level factors leading to change.

The field is aware of the problems associated with limited educator competence and the

impact this has to support students for the transition to adulthood. As described previously, the

relationship between level of knowledge and skills and the likelihood of implementing effective

transition practices is evident. Both barriers and facilitative factors supporting transition-specific

content within teacher education and professional development have been identified. However,

less is known about strategies and approaches toward increasing transition competencies. A

better understanding of critical factors and influences on effective methods for teacher education

and professional development is needed. Within our current constraints of reduced budgets for

teacher professional development, distilling essential and impactful approaches will strengthen

outcomes for students.

The purpose of this study was to more closely examine the critical features of secondary

special educator’s experiences with transition professional development in order to predict which

Transition Training Matters 5

variables were more likely to influence the frequency with which special educators perform

activities related to transition planning and services. The research questions guiding this study

were:

1. To what extent do secondary special educators and transition specialists feel prepared

to and with what frequency are they performing effective transition practices?

2. Is there a relationship between preparation experience and the frequency with which

they perform transition practices?

3. Are certain preparation variables more likely to predict how prepared secondary

special educators feel and how frequently they perform effective transition practices?

Methods

The results of this research were part of a larger study designed to more broadly examine

the transition competencies of secondary special educators (Benitez, Morningstar, & Frey, 2009).

The focus of this study is to specifically examine the factors most likely to influence the

frequency with which secondary special educators implement transition activities. In particular,

we examined the influence of a teacher’s preparation experience on frequency of implementing

transition competencies. A “preparation experience” construct was created as a composite

variable consisting of years teaching, certification/licensure levels, number of transition courses,

and hour of professional development in transition. Data was collected from a national sample

of 557 secondary special educators who responded to a survey of 46 transition competencies in

which participants were asked to report levels of preparation as well as the frequency with which

they performed the competencies.

Participants

Transition Training Matters 6

The participants included middle and high school special educators from 31 states. Using

a national educational marketing database of over 35,000 secondary special educators,

approximately 6,200 participants recognized as responsible for teaching youth with learning

disabilities (LD), intellectual disabilities (ID), emotional and behavioral disabilities (ED/BD),

and high incidence (non-categorical) students were identified and randomly selected. The

researchers employed a stratified random sampling procedure to select a representative sample of

teachers responsible for teaching students from four disability groups matching the categorical

proportion of students in special education as reported to the Department of Education. (U.S

Department of Education, 2005). From this stratified pool, 1,800 participants were randomly

selected using the following stratification among certain disability categories: (a) 1,200 (67%)

from the LD category; (b) 200 (11%) from the resource classroom category; (c) 200 (11%) from

the ED/BD category; and (d) 200 (11%) from the ID category.

Instrumentation

The Secondary Teachers’ Transition Survey (STTS, Benitez & Morningstar, 2005) was

developed specifically for use in this study, primarily due to the paucity of research in this

particular area, as well as the dated content of previous surveys available at the time of the initial

research. In particular, we were interested in ensuring that the most current transition

requirements under the IDEA 2004 were reflected in the survey, as well as competencies

identified by national organizations offering special education and transition teacher standards.

Additionally, the STTS incorporated current issues facing the secondary special educators as

well as the field in general that had emerged since previous standards were developed. For

example, items specific to cultural responsiveness to families and students, assistive technology,

access to the general education curriculum and accountability measures were included in the

Transition Training Matters 7

STTS item pool and incorporated into the final items. To develop the instrument and ensure

content and social validity, the researchers conducted a thorough review of the special education

transition literature to identify: (a) effective transition planning and service delivery practices; (b)

the provision of transition-related content within teacher preparation programs; and (c) teachers

perceptions of their own delivery of transition services (Blanchett, 2001; deFur and Taymans,

1995; Knott & Asselin, 1999). In addition, national certification standards were examined to

identify transition-related competencies (e.g., Council for Exceptional Children’s (CEC)

Standards for All Beginning Special Education Teachers in Individualized General Curriculum

(2009), and the CEC Standards for the Preparation of Transition Specialists (2009).

Selecting transition domains and competencies. The investigators reviewed several

research articles addressing transition competencies (e.g., Blanchett, 2001; deFur and Taymans,

1995; Knott & Asselin, 1999). The competencies contained in these articles were combined with

the CEC General Curriculum Standards for Beginning Teachers (CEC, 2009a), as well as the

CEC Advanced Standards for Transition Specialists (CEC 2009b) which yielded a total of 289

possible transition-related teacher competencies. A matrix was developed using the CEC General

Curriculum standards serving as an initial, pre-existing taxonomy into which the 289

competencies were grouped. Items selected for the STTS were determined through a content

analysis and data-reduction method that resulted in the classification of certain competencies

most often identified as critical for secondary special education teachers. The selection of a

competency was determined if it was present in at least 90% of all sources of

research/competency standards. The end result was the identification of 46 competencies that fell

within six domains: Instructional Planning, Curriculum and Instruction, Transition Planning,

Transition Training Matters 8

Assessment, Collaboration and Additional Competencies. Each domain included approximately

seven competency statements.

The STTS collected a variety of demographic information, of which this study was most

interested in: (a) number of years teaching, (b) number of transition courses taken, (c) number of

transition staff development hours, (d) level of certification for teaching, (e) classifications of

students taught, (f) types of educational classrooms, and (e) community setting. The second part

of the STTS was designed to elicit respondent perceptions regarding levels of preparation as well

as frequency with which participants performed the 46 transition competencies. For every listed

competency statement, the subjects responded to a 4-point Likert scale regarding their level of

preparation (1 = very unprepared to 4 = very prepared) and frequency of performance (1= never

to 4= frequently). Item consistency across the two rating subscales was determined using

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient; and demonstrated alphas of .96 and .94 respectively, indicated

high reliability (Santos, 1999). In addition, internal consistency reliability estimates (coefficient

alpha) for each of the seven subscales were computed and ranged from .83 to .95, indicating

good to high reliability.

Survey packets that included the STTS, a cover letter explaining the purpose of the study,

self-addressed, postage-paid envelope, and an incentive to complete and return the survey were

mailed to participants. Approximately 20 days after the first mailing, a postcard reminder was

sent to those individuals who had not yet responded. Several weeks after the postcard reminder, a

second survey packet was sent. Two months following, researchers completed a third round of

mailings resulting in a total of 557 returned surveys.

Results

Transition Training Matters 9

Of the original 1,800 surveys sent, 643 were returned; with 86 deemed unusable

(participants were not special educators), thereby decreasing the total number of possible surveys

from 1,800 to 1,714. In total, 557 valid surveys were completed and returned, generating a 33%

response rate.

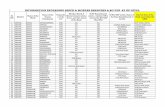

Demographic Results

Respondents indicated the types of students whom they taught: (a) 51% students with

learning disabilities (LD); (b) 11% students with intellectual disabilities (ID); (c) 9%

“Transition” as their primary teaching responsibility (e.g., transition specialists), (d) 6% students

with emotional/behavioral disabilities (E/BD), (e) 3% “low-incidence” students (e.g., deaf/blind,

significant intellectual disabilities, other health impairment). In addition, a “Combination” group

comprising 20% of the respondents was calculated based on teachers checking more than one

disability category. The majority of respondents taught at the secondary level (66% high school

& 23% middle school). Ten percent taught across grade levels. The type of settings in which

they provided instruction included: 39% resource room; 21% self-contained special education

classroom; 20% multiple settings; 10% co-teaching in general education; 5% “other” classrooms;

5% special schools, and 4% special education consultant services. The type of community in

which they worked included: 20% urban; 32% suburban; 46% rural; and 3% combination of

geographic locations.

Level of preparation experience. To calculate a “preparation experience” variable,

participants were asked to respond to items pertaining to teaching and professional development

experiences (years teaching, highest degree, number of transition courses, number of

professional development hours). The mean for total years teaching was 17 years (range 1- 41

years), with educators falling into three groups: 1–10 years teaching (33%); 11–21 years teaching

Transition Training Matters 10

(34%); and 22+ years teaching (33%). Thirty-two percent indicated highest degree was a

bachelor’s, while 63% held master’s degrees, .7% doctoral degrees, and 4.3% other degrees (e.g.,

associate of arts degrees). Twenty-one percent of the respondents indicated that they were

working on additional degrees.

The mean number of transition-related courses was 1.07, with an unusually wide range of

responses (0–70); therefore, all responses above six or more courses were analyzed as missing

data; leaving the total number of respondents for this item at 486. The average number of

transition-related staff development hours was 28 hours, with almost 14% reporting no

professional development in transition. The preparation experience variable was calculated by

first computing Z-scores for the four variables (i.e., certification, years teaching, transition

courses, professional development). These scores were then summed to compute a single score

reflecting “preparation experience.”

Levels of Preparation and Implementation of Transition-specific Competencies

Respondents rated their overall level of preparation to perform the 46 transition

competencies as somewhat unprepared to somewhat prepared (M=2.69, SD=.65) on a scale of 1

= very unprepared to 4 = very prepared. A one-way between groups ANOVA was conducted to

determine differences in preparation levels between special educators working with specific

student disability groups (i.e., LD, ID, ED/BD, combination, low-incidence, and transition). We

found significant differences between groups (F[5, 543] =5.21, p<.001), with a small effect size

(η2=.046) accounting for 5% of the variance. Post-hoc tests using the Tukey HSD test

demonstrated the mean score for preparation levels of the Transition group (M=3.08, SD=.08)

was significantly higher than certain other teacher groups: (a) LD (M=2.61, SD=.62, p<.00); (b)

Low-Incidence (M=2.53 SD=.64, p<.03); and (c) Combination (M=2.66, SD=.66, p<.002).

Transition Training Matters 11

Level of implementation of transition activities. Respondents indicated the frequency

with which they performed transition practices along a scale of 1=never to 5=frequently.

Average frequency fell within the range of rarely to occasionally (M=2.70, SD=.56). One-way

ANOVAs comparing student groups revealed that differences were statistically significant (F[5,

545]= 6.04, p<.001), with a moderate effect size (η2= .053). Post-hoc comparisons using Tukey

HSD indicated significant differences for frequency of implementing transition activities among

the Transition group (M=3.03, SD=.51) and certain subgroups of teachers: (a) LD (M=2.62,

SD=.53, p<.01), (b) Low-Incidence (M=2.54, SD=.66; p<.01), and (c) Combination (M=2.71,

SD=.56, p<.01). Thus, transition specialists were more likely than certain teachers to implement

transition activities. In addition, post-hoc comparison of means were significantly different

among teachers of students with ID (M=2.87, SD=.63,) and teachers of students with LD (p=.02);

indicating that teachers of students with ID were more likely to perform transition competencies

than were teachers of students with LD.

Preparation and frequency across the transition domains. Means and standard

deviations were calculated for the six transition domains across levels of preparedness and

frequency and are presented in Table 2. Means and standard deviation scores were calculated

across the dependent variables of preparedness and frequency scales and teacher groups. The

overall mean rankings for domains from highest to lowest were: (a) Transition Planning

(M=3.13, SD=.67), (b) Curriculum and Instruction (M=2.93, SD=.54), (c) Assessment (M=2.49,

SD=.71), (d) Instructional Planning (M=2.46, SD=.70), (e) Additional Competencies (M=2.43,

SD=.73), and (f) Collaboration (M=2.40, SD=.78) (see Table 1).

<Table 1 here>

Transition Preparation and Frequency Influenced by Preparation Experience

Transition Training Matters 12

An initial analysis determined the relationship between levels of preparation and

frequency of performance of transition activities. A Pearson Correlation showed a significant and

large positive correlation (r=.72, p<.01) indicating that the more prepared teachers perceived

themselves to be to plan and deliver transition services, the more frequently they reported

performing these activities.

Correlation analyses were then computed to determine the relationship between the

teacher preparation experience composite score (years teaching, number of courses, hours of

staff development) and level of preparation. Preparation experience and level of preparation were

significantly, positively correlated (r=.30, p<.01). The strength of the relationship was moderate

(Green, Salkind, & Akey, 2000), and indicated that the higher teachers’ preparation experience

scores, the better prepared they reported themselves to be to perform the transition activities.

Correlation coefficients were also computed for the preparation experience variable and the

frequency with which educators engaged in transition practices. Preparation experience was also

significantly and moderately correlated with frequency scores (r=.30, p<.01), with the results

indicating that high scores on the preparation experience variables were associated with high

levels of engagement in delivering transition services to students.

Based on these results, analysis of the preparation experience factors was completed to

confirm relationships among factors and frequency of implementation (see Table 2). These

results indicated significant moderate correlations among courses and staff development and a

low but significant correlation with certification status and frequency of implementation. A

regression analysis was conducted to examine which preparation experience factors were most

likely to predict frequency of implementing transition competencies. The predictors were the

preparation experience variables (i.e., certification status, years teaching, number of transition

Transition Training Matters 13

courses, staff development hours) and the criterion was frequency of implementing transition

practices. The results indicated that preparation experience was significantly related to frequency

of transition practice implementation, F(4, 467)=25.5, p<.001, and accounted for 18% of the

variability in frequency of implementation (R2=.18). Table 4 reports indices of the relative

strength of the individual predictors, with “total years teaching” as the only factor not being

significant.

<Table 2 & 3 here>

A second regression model (see Table 3) was analyzed removing “years teaching” with

overall results remaining virtually the same (R2=.18, F(3, 468)=33.96, p<.001), thereby

supporting the conclusion that years teaching was not a factor influencing frequency of

implementation over and above staff development hours, certification status, and number of

transition courses. Squared semi-partial correlations calculated in the second model revealed that

number of transition courses (r2=.07 p<.001) and staff development hours (r2=.08 p<.001) each

contributed to the overall variance in frequency of implementing transition practices, and after

accounting for any overlap among the predictors, appeared to be contributing equally. While

certification status did not contribute meaningfully to the overall model, it was statistically

significant (r2=.01 p<.05). These results indicate that the factors significantly influencing the

frequency with which educators implement transition activities were the number of transition

courses completed and number of transition staff development hours enrolled.

Discussion

The purpose of this investigation was to identify critical features of secondary special

educator’s experiences with professional development in order to predict variables most likely to

influence the frequency with which special educators perform transition activities. We analyzed

Transition Training Matters 14

a multi-state dataset that targeted secondary special educators and their perceptions regarding

levels of preparation and frequency of implementation of 47 transition-related practices. A

“preparation experience” variable was calculated from among four variables (years teaching,

highest degree, number of transition courses, number of professional development hours) as a

predictor of the frequency with which secondary special educators perform transition practices.

The results of this analysis revealed that training matters when it comes to implementing

transition practices among secondary special education teachers. The completion of transition

courses and involvement in professional development significantly influenced the degree to

which teachers implement transition practices. Certification status was a significant influence

but did not contribute to the overall variance; and number of years teaching was not a predictor.

These results have implications for establishing models of both preservice and inservice

transition professional development.

Implications

The results from this study offer noteworthy implications specifically for transition

teacher education and systems of professional development, as well as more general perspectives

for strengthening training of educators. One outcome of the research was to establish the

differentiated roles among secondary special educators who primarily serve certain groups of

students with disabilities, as well as to identify the critical role of the transition coordinator.

Additionally, the study clarified the types of professional development obtained by the

respondents. Of import is the finding that transition teacher education and professional

development are significant factors influencing the frequency with which secondary special

educators implement required transition services and practices. Given these results,

recommendations are offered for improving teacher education specific to content and methods

Transition Training Matters 15

for implementing transition teacher education. Finally, implications for professional

development are offered. While the results are explicitly described within the realm of transition

education and services, the implications for other specialized knowledge and skills should be

noted, particularly with regard to understanding the relationship between ongoing training and

the implementation of educational strategies and interventions.

Types of school personnel implementing transition. Teachers of secondary students

with LD made up more than one-half the entire group of respondents. This was expected as it

roughly corresponds to estimates of national special education teacher representation (U.S.

Department of Education, 2008) and parallels other transition competency research (Blanchett,

2001; Knott & Asselin, 1999). Almost one-half the total respondents came from rural areas and

held master’s degrees. Across all respondents, teachers had a mean of 16.6 years teaching

experience, a number that is comparable to previous special education research (Blanchett, 2001;

Carlson et al., 2002; Wagner, Cameto, Garza, & Levine, 2005).

Two types of school personnel are involved with transition education and services: (a)

secondary special education teachers engaged in IEP transition planning and instruction, and (b)

transition specialists who ensure a coordinated set of activities as specified in the transition

requirements of IDEA. Whereas, IDEA articulates that any special educator holding a valid

special education credential and working in a secondary school is responsible for transition

planning, the most effective programs have transition specialists who provide coordination and

support across students, families, teachers, and outside systems (Noonan, Morningstar, &

Gaumer, 2008). Differentiating the roles and responsibilities of secondary special educators and

transition specialists is an important endeavor, in that such distinctions can support teacher

training practices.

Transition Training Matters 16

In particular, the results from this study comparing the levels of preparation and

implementation among certain types of special educators support the conception that disparities

do exist. The results revealed that those respondents identified as transition specialists were the

most prepared, as well as more likely to implement transition practices. Among the other groups,

teachers of students working with students with intellectual disabilities reported the next highest

rates of preparation and implementation. Given the functional nature of curriculum for students

with more significant disabilities, these results are not surprising. Nor are the data indicating

teachers of students with learning disabilities reported the lowest levels of transition preparation

and implementation. Given that the duties of these teachers is often driven by the needs of

students included in general academic classes. However, transition planning and services are

equally critical for all types of students with disabilities, and ensuring that all secondary special

education teachers have sufficient training to implement established practices should be a

priority.

The position of transition specialist has emerged with the advent of transition-focused

education and related legislation. This specialized position consists primarily of coordinating

transition services, rather than providing direct services to students (Morningstar & Clavenna-

Deane, 2009; Blalock et al. 2003). Transition specialists enhance transition by ensuring that

teachers are informed of current information and methods for facilitating transition planning (e.g.

identifying students’ post-school interests, preferences, strengths, and needs). Furthermore,

transition specialists work as liaisons between students, parents, administrators, and staff to

connect postsecondary goals with curriculum decisions that drive course content.

Transition specialists are expected to possess certain knowledge and skills as reflected in

the CEC Advanced Content Standards for Transition Specialists (2009b). The CEC standards

Transition Training Matters 17

address advanced knowledge of transition philosophy, practices, and legal requirements as well

as competencies of knowledge and experience with transition assessment, diagnosis, and

evaluation and instruction on community based activities, vocational experiences, and academic

preparation for post-school environments. Few studies have assessed transition coordinators’

knowledge and skills or implementation of transition practices. This study identified a subgroup

of transition coordinators and, therefore, is able to provide at least preliminary results regarding

their duties.

Content and delivery of transition teacher training. In terms of transition coursework,

teachers in this study reported completing an average of one transition course at the

undergraduate or graduate level, and almost one-half had no transition courses. This parallels

previous research specifically focusing on universities’ offering of transition courses, with less

than one half offering standalone courses in transition (Anderson et al., 2003). The results from

this study seem to bear this in mind, with the highest ranked domains from the survey being

transition planning, curriculum and instruction and instructional planning, which are the most

commonly taught preservice content (Anderson et al., 2003). Whereas the domains of

interagency collaboration and transition assessment are less likely to be taught to preservice

students.

Over the past decade, researchers have investigated transition teacher education

programs, with the Division of Career Development and Transition (DCDT) recommending that

transition teacher education emphasize instructional content that aligns secondary curriculum and

transition services; and includes principles, models, and strategies proven to support career

development and transition (Blalock, Kocchar-Bryant, Test, Kohler, White, Lehman, J., et al.,

2003). In addition Morningstar and Clark (2003) describe five broad content areas for transition:

Transition Training Matters 18

(a) principles and concepts of transition education and services; (b) transition evidence-based

practices for student-focused planning; (c) community-referenced curriculum and instruction

targeting identified evidence-based practices: (d) promoting interagency collaboration; and (e)

addressing systemic problems in transition service delivery. These five areas are consistent with

research regarding effective practices and research leading to positive postschool outcomes

(Alwell, & Cobb, 2006; Kohler & Fields, 2003; Test, et al., 2009).

Morningstar and Clark (2003), describe four types of transition personnel preparation

programs: (a) transition master’s programs (30 or more hours toward an advanced degree); (b)

transition specialization programs (15 or fewer credit hours; focusing on a state endorsement or

licensure program for transition specialists); (c) transition class or classes; and (d) transition

content infused within existing courses. Transition master’s programs have primarily been

supported by federal personnel preparation grants, as well as higher education institutional

commitment to faculty specialization. Transition specialization programs have emerged in

response to federal preparation grants, or because of state transition certification standards. Little

data exists to articulate what courses and competencies are included, and how programs are

sustained. Anecdotally, however, it appears that transition specialization programs typically

consist of 3-4 classes and are based on the CEC standards for transition specialists (CEC,

2009b).

Offering a transition course is the most common form of transition content delivery, with

45% of institutions of higher education (IHEs) reporting this method (Anderson, et al., 2003; Hu,

2001). Unfortunately, offering single courses in transition are often tied to faculty interest and

knowledge of transition. Finally, infusing transition content within existing courses is the most

common approach to offering transition content when training special education teachers

Transition Training Matters 19

(Anderson et al., 2003). As states move toward K-12 non-categorical teacher standards, the

increased pressures on higher education faculty to cover the breadth of information will mean

that less time can be devoted to transition content. In addition, faculty who possess limited

knowledge are less likely to embed transition content into existing coursework.

Professional development

It is interesting to consider that high levels of implementation had less to do with whether

the educator was a veteran or beginning teacher. This was somewhat surprising, as it would be

expected that teachers who recently graduated from a teacher preparation program would have

had more opportunities to learn about transition education and services. Unfortunately, teacher

preparation has not caught up to the realities of secondary special education (Anderson et al.,

2003). The “transition” mandates have been legislated for over two decades, and it is evident

that secondary special educators require specialized knowledge and training in this area. From

this study, those who have had the opportunity to enroll in at least one transition course or for

whom professional development opportunities were provided were much more likely to feel

prepared and to implement specific transition competencies on a more frequent basis.

Respondents indicated a mean of 28 hours of transition staff development, with

approximately 14% indicating they had acquired no transition staff development hours

throughout their careers. Conversely, almost three quarters of the respondents reported they had

between 1 and 50 hours of transition in-service training. Such inconsistencies in the data imply

that professional development opportunities are erratic at best. Given the constraints associated

with teacher education models, the importance of highly effective and ongoing professional

development is even more pressing. Furthermore, states identify a primary method of transition

training takes place on-the-job rather than through comprehensive or systematic professional

Transition Training Matters 20

development efforts (Kochhar-Bryant, 2003). In the past, states have targeted transition

personnel development as a priority within special education state improvement grants and

statewide planning (Kocchar-Bryant, 2003; Storms & Sullivan, 2000), often without significant

impact over time.

Regrettably, transition professional development is often illustrated by a lack of clear

policies as well as limited systems for planning, delivering and evaluating its impact. Transition

professional development has been defined as a comprehensive system of training and technical

assistance that can take many formats (i.e., inservice training, mentoring systems, online;

Morningstar & Kleinhammer-Trammil, 2005). Comprehensive professional development

requires transition-related competencies to be identified and instructed across both preservice

and in-service levels as well as through a variety of methods and strategies (Morningstar &

Bassett, 2007).

A first element in such a model is to ensure that teachers acquire specific transition

knowledge to improve instructional practices. This notion also requires teachers to develop an

understanding of how they can incorporate transition-related content into subject matter and class

activities. For some time, effective professional development models incorporate coaching or

mentoring to ensure mastery of skills and implementation (Porter, Garet, Desimone, Suk Yoon,

& Birman, 2000; Sparks, 2002). This approach must also be replicated for transition in-service

training so that we move away from the “one-shot” workshops and toward a model that

incorporates effective knowledge generation combined with ongoing support and technical

assistance

Morningstar and Lattin (2012) have offered a model for enhancing professional

development through a blend of online self-directed learning, combined with participant

Transition Training Matters 21

facilitated learning using both face-to-face and online engagement. This approach is similar to

the concepts inherent in the “flipped classroom” where acquiring information through reading,

online modules, webcasts, or audio presentations occurs independently (i.e., homework), and

classroom time is devoted to applying knowledge (Bennett, Kern, Gudenrath, & McIntosh,

2011). For transition professional development, this approach lessens the costs associated with a

workshop or conference, where professionals travel to learn new information. Instead, district

teams learn about new interventions, policies or strategies using guided and self-directed

learning modalities. Then the teams come together (face to face or online) to plan for program

improvements and problem-solve solutions (Morningstar & Lattin, 2012).

Limitations

A limitation of this research was that respondents were asked to generate answers based

on their own perceptions of transition competencies. Because of the nature of self-report studies,

their answers may not reflect their true experiences. Another limitation was related to

respondents’ answers to two of the survey items: total number of transition courses and total

number of transition staff development hours. Specifically, respondents may have had difficulty

understanding the questions’ intentions (i.e., to focus only on those courses and professional

development hours that were specific to transition), or they may have had problems recalling and

estimating these responses. A third limitation to the study related to possible nonresponse bias.

This study could not obtain completed surveys from actual non-respondents and, therefore,

employed a technique of comparing early to late respondents. Thus, the investigators could not

determine if those secondary special education teachers who responded to the survey were

different from those who did not respond. The data collected in this research study are based on

information from special education teachers from 31 states. Generalization to the broader

Transition Training Matters 22

population of secondary teachers from states not represented in this study must be made with

some caution. Finally, close to 95% of the sample were fully certified to teach in the area in

which they were teaching. This means that the sample population may not represent the general

population of special education teachers, in that research indicates lower levels of certification

(McLeskey, Tyler & Saunders Flippin, 2004).

Conclusions

Transition planning is not a new phenomenon; federal mandates have been in place since

1990, and initiatives to improve postschool outcomes were pronounced during the 1980’s (Will,

1984). Rusch, Szymanski, and Chadsey-Rusch (1992) described how "transition services" for

youth with disabilities could be found as early as the 1930s for deaf students, and the 1940s for

students with mental retardation. It was not until the 1960s, however, that educational and

vocational models were systematically developed to comprehensively address career education

issues for students with disabilities (Halpern, 1992). The early career development and

vocationally orientated curricula are thought of as precursors to today’s efforts. Given the long

history of research and policies regarding how to prepare and support youth with disabilities to

achieve successful adult outcomes, there appears to be still work to be accomplished, particularly

in ensuring that educators possess the knowledge and skills needed to implement effective

practices. The results of this study offer a current understanding of secondary special educators

competencies regarding essential facets of transition, as well as their ensuing enactment of

practices. It would seem that training matters when expecting special educators to implement

specialized interventions and services. While certainly not a profound conclusion, these results

do lend credence to the importance of systematic professional development that originates with

established course content addressing specialized knowledge and skills, and is sustained and

Transition Training Matters 24

References

Alwell, M., & Cobb, B. (2006). A systematic review of the effects of curricular interventions on

the acquisition of functional life skills by youth with disabilities. What works in

transition: Systematic review project. Ft. Collins, CO: Colorado State University.

Anderson, D., Kleinhammer-Tramill, J. P., Morningstar, M., Lehman, J., Kohler, P., Blalock, G.,

et al. (2003). What’s happening in personnel preparation in transition? A national survey.

Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 26(2), 145–160.

Bassett, D. & Morningstar, M.E. (2011, May). Districts working with higher education to build

professional capacity. Presentation at the National Secondary Transition Technical

Assistance Center National Summit. Charlotte, NC.

Bennett, B., Kern, J., Gudenrath, A., & McIntosh, P., (2011, June, 23). The flipped classroom:

What does a good one look like? The Daily Riff [online magazine]. Retrieved from

http://www.thedailyriff.com/articles/the-flipped-class-what-does-a-good-one-look-like-

692.php

Benitez, D., & Morningstar, M.E. (2005). The Secondary Teachers’ Transition Survey.

University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS: Author.

Benitez, D., Morningstar, M.E., & Frey, B. (2009). Transition service and delivery: A multi-state

survey of special education teachers’ perceptions of their transition competencies. Career

Development for Exceptional Individuals, 32(1), 6-16.

Blalock, G., Kocchar-Bryant, C. A., Test, D. W., Kohler, P., White, W., Lehman, J., et al.

(2003). The need for comprehensive personnel preparation in transition and career

development: A position statement of the Division on Career Development and

Transition. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 26(3), 207–226.

Transition Training Matters 25

Blanchett, W. J. (2001). Importance of teacher transition competencies as rated by special

educators. Teacher Education and Special Education, 24(1), 3–12.

Carlson, E.L. & Schroll, K. (2004). Identifying teacher attributes of high quality special

education teachers. Teacher Education and Special Education, 27(4), 350-359.

Council for Exceptional Children. (2009a). CEC knowledge and skill base for all beginning

special education teachers of students in individualized general curriculum. Arlington,

VA: Author.

Council for Exceptional Children, (2009b). CEC advanced content standards for transition

specialists. What every special educator must know: The international standards for the

preparation and certification of special education teachers. (6th edition), pp. 167-171.

Arlington, VA: Author.

deFur, S.H., & Taymans, J.M. (1995). Competencies needed for transition specialists in

vocational rehabilitation, vocational education, and special education. Exceptional

Children, 62(1), 38-52.

Green, S. B., Salkind, N. J., & Akey, T. M. (2000). Using SPSS for Windows: Analyzing and

understanding data (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Greene, G.A. & Kochhar-Bryant, C. A. 2003. Pathways to successful transition for youth with

disabilities. Columbus, OH: Merrill Prentice Hall

Halpern, A. S. (1985). Transition: A look at the foundations. Exceptional Children, 51, 479-486.

Hu, M. (2001). Preparing preservice special education teachers for transition services: A

nation-wide survey. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Kansas State University, White,

Kansas.

Transition Training Matters 26

Knott, L., & Asselin, S. B. (1999). Transition competencies: Perception of secondary education

teachers. Teacher Education and Special Education, 22(1), 55–65.

Kochhar-Bryant, C. (2003). Building transition capacity through personnel development:

Analysis of 35 state improvement grants. Career Development for Exceptional

Individuals, 26(2), 161–184.

Kohler, P.A. & Fields, S. (2003). Transition-focused education: Foundation for the future.

Journal of Special Education, 37(3), 174-183.

Li, J. Bassett, S. D., Hutchinson, S.R. (2009). Secondary special educators’ transition

involvement. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, June 2009; 34(2): 163–

172

McLeskey, J., Tyler, N.C., & Saunders Flippin, S. (2004). The supply of and demand for special

education teachers : A review of research regarding the chronic shortage of special

education teachers. Journal of Special Education 38(1), 5-21.

Morningstar, M.E. (2010, May) Aligning multi-tiered models of support in secondary schools

with transition focused interventions. Presened at the National Secondary Transition

Technical Assistance Center Annual Capacity Building Institute, Charlotte, NC.

Morningstar, M. E., & Basset, D. (2007, October). Developing systems of professional

development in transition: Resources and strategies. Paper presented at the meeting of

the National Secondary Technical and Training Assistance Center, Orlando, FL.

Morningstar, M.E., & Benitez, D. (2010). Teacher knowledge to program implementation:

Transition professional development needed to impact outcomes. Presented at the

Council for Exceptional Children International Conference. Nashville, TN.

Transition Training Matters 27

Morningstar, M.E., Benitez, D., & Wade, D.K. (2012 April). Secondary Teachers Transition

Survey-Transition Coordinators (STTS-TC) Content Analysis Procedures. University of

Kansas, Lawrence, KS.

Morningstar, M. E., & Clark, G. M. (2003). The status of personnel preparation for transition

education and service: What is the critical content? How can it be offered? Career

Development for Exceptional Individuals, 26(3), 227–237.

Morningstar, M.E. & Clavenna-Deane, E. (2009, April). Effective practices during transition:

Does preparation make a difference? Presented at the Division of Career Development

and Transition International Conference, Savannah, GA.

Morningstar, M.E. & Kleinhammer-Tramill, J. (2005). Professional development for transition

personnel: Current issues and strategies for success. National Center on Secondary

Education and Transition Information Brief. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

Morningstar, M.E., & Lattin, D.L. (2012, September). Engaging learners in online professional

development for transition. Presentation for the National Secondary Transition Technical

Assistance Center Webinar.

Morningstar, M.E., & Liss, J.M (2008). A preliminary investigation of how states are responding

to the transition assessment requirements under IDEA 2004. Career Development for

Exceptional Individuals, 31(1), 48-55.

Noonan, P. N., Morningstar, M. E., & Gaumer-Erickson, A. (2008). Improving interagency

collaboration: Effective strategies used by high performing local districts and

communities. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals. , 31(3), 132-143.

Porter, A. C., Garet, M. S., Desimone, L., Suk Yoon, K., & Birman, B. F. (2000). Does

professional development change teaching practices? Results from a three-year study

Transition Training Matters 28

(Report to the U.S. Department of Education, Office of the Under Secretary on Contract

No. EA97001001 to the American Institutes for Research). Washington, DC: Pelavin

Research Center.

Santos, J. R. (1999). Cronbach’s Alpha: A tool for assessing the reliability of scales. Journal of

Extension, 37(2). Retrieved January 15, 2005, from

http://www.joe.org/joe/1999april/tt3.html

Sparks, D. (2002). Designing powerful professional development for teachers and principals.

Oxford, OH: National Staff Development Council.

Storms, J., & Sullivan, L. (2000). Summary of funded state improvement grant applications in

2000. Eugene, OR: Western Regional Resource Center.

Test, D. W., Fowler, C. H., Richter, S. M., White, J., Mazzotti, V., Walker, A. R., Kohler, P., &

Kortering, L. (2009). Evidence-based practices in secondary transition. Career

Development for Exceptional Individuals, 32(2), 115-128.

US Department of Education (2008). Thritieth Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation

of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Washington DC: Author. Retrieved

September 18, 2011, from http://www2.ed.gov/about/reports/annual/osep/2008/parts-b-

c/index.html

Wagner, M., Newman, L., Cameto, R., Garza, N., & Levine, P. (2005). After high school: A first

look at the postschool experiences of youth with disabilities. A report from the National

Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2). Menlo Park, CA: SRI Internationa

Wagner, M., Newman, L., Cameto, R., Garza, N., & Levine, P. (2009). The post-H]high school

outcomes of youth with disabilities up to 4 Years after high school. A report of findings

from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2) (NCSER 2009-3017). Menlo

Transition Training Matters 29

Park, CA: SRI International. Retrieved

from: www.nlts2.org/reports/2009_04/nlts2_report_2009_04_complete.pdf.

Wolfe, P. S., Boone, R. S., & Blanchett, W. J. (1998). Regular and special educators’ perceptions

of transition competencies. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 21, 87–106.