Supply chain modularisation: Cases from the French automobile industry

Transcript of Supply chain modularisation: Cases from the French automobile industry

Int. J. Production Economics 106 (2007) 2–11

Supply chain modularisation: Cases from theFrench automobile industry

Desmond Doran!, Alex Hill, Ki-Soon Hwang, Gregoire Jacob,Operations Research Group

Kingston Business School, Kingston University, Kingston Hill, Kingston upon Thames, Surrey KT2 7LB, UK

Available online 2 June 2006

Abstract

In recent years car manufacturers have been gradually moving from the procurement of discrete parts to theprocurement of modular systems. However, research into this development has not yet sought to identify how such a shiftis likely to influence the operations of key suppliers within a modular supply chain and more specifically, how suchsuppliers are likely to interpret their respective approaches to modular provision. The aim of this research is to addressthese issues using a case-based approach of a modular supply chain currently engaged in supplying cockpit modules to aFrench car manufacturer. The findings accord broadly with research undertaken in the United Kingdom [Doran, D., 2004.Rethinking the supply chain: an automotive perspective. International Journal of Supply Chain Management 9(1),102–109] which indicated that accommodating modular supply is both complex and challenging and requires a discrete setof competencies that move beyond traditional approaches to product procurement. Specifically the findings suggest thatstrategies commensurate with supplying on a modular basis are likely to involve an increased degree of risk sharing, astrategy for acquiring a cohesive set of supply chain management capabilities and a readiness to dispose non-core activitieswhile acquiring those activities that will enhance modular capabilities.r 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Modularisation; Supply chain management; Automotive

1. Introduction

The growth of modular assembly and modulardevelopment has gathered significant pace duringthe last decade and seems set to dominate thosesectors where product complexity is high andconsumer demands are constantly changing. Therate of modular growth has been attributed to anumber of factors, including the potential forincreased flexibility, increased speed to market and

reduced cost (McAlinden et al., 1999). Sanchez andCollins (2001) suggest that the most visible benefitsof modularity are the ability to configure newproduct variations quickly and at low cost bymixing and matching components within modularproduct architecture.

Similarly Velos and Kumar (2002) note thatthe move toward modules within the automotivesector has been influenced by declining profitper vehicle, shorter product life cycles and theincreasingly sophisticated demands of consumers inglobal markets. Earlier research by Langlois andRobertson (1992) centred upon the microcomputer

ARTICLE IN PRESS

www.elsevier.com/locate/ijpe

0925-5273/$ - see front matter r 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2006.04.006

!Corresponding author. Tel.: +44 020 8547 2000.E-mail address: [email protected] (D. Doran).

industry which is, perhaps, the benchmark formodular activity and noted that:

The development of modular systems can lead tovertical and horizontal disintegration, as firmscan often best appropriate the rents of innova-tion by opening their technology to an outsidenetwork of competing and co-operating firms.(p. 297)

However, defining what actually constitutes a‘module’ and what constitutes ‘modularisation’ is,as yet, an area of some debate. Noting thiscomplexity Camuffo (2000) describes modularisa-tion as:

a vaguely defined and ambiguously used term inthe auto industryya broad concept, applicableand applied to a number of systems (productdesign, manufacturing, work organisation, etc).(p. 2).

Carliss et al. (1997) capture the essence ofmodularity which they describe as:

building a complex product or process fromsmaller subsystems that can be designed inde-pendently yet function together as a whole.(p. 84)

Although the above descriptions of modularityand modularisation suggest a lack of clarity and abroadness of scope, Helper et al. (1999) predict thatvehicles will soon consist of self-contained func-tional units with standardised interfaces within oneor more standardised product architectures, manu-factured or supplied, and assembled as autonomousmodules. In terms of developing strategies com-mensurate with modularity, Helper et al. (1999)suggest a number of possible modular strategies:

! Modular design for some subsystems but notwhere costs outweigh benefits.

! Modules that are automaker specific with OEMsavoiding or blocking industry in their design

functionality, technical standards and commoninterfaces.

! Only some modules outsourced with criticalmodules produced by the OEM, outsourcingnon-modular components.

Within the automotive sector the most visibleexample of the trend toward modularisation is the‘Smart’ car collaboration between Mercedes-Benzand the watchmakers Swatch. Mercedes-Benz andSwatch took an innovative design, a purpose builtplant and a new supply base designed specifically toaccommodate modularisation of the Smart car.Whilst a typical car manufacturer would deal witharound 200–300 suppliers, the Smart car collabora-tion uses twenty-five module suppliers. Examples ofSmart modules include complete dashboard sys-tems, body structure, breaking control systems andseating modules. Indicative of the modular ap-proach is the transfer from the OEM of a higherpercentage of value-creating activities to upstreamsuppliers; at the Smart car assembly plant onlytwenty percent of value-creating activity is under-taken within the assembly plant. In reality, what thismeans to key suppliers within developing modularsupply chains (particularly, tier one, tier two andtier three suppliers) is that there will be opportu-nities to become more involved in activities thatwould normally be completed by their downstreamcustomers. So, for example, a tier one supplier maybe requested by a car manufacturer (OEM) custo-mer to undertake activities generally undertaken bythe OEM, while a tier one supplier may transfersome if its non-core activities upstream to a tier twosupplier, and so on. Determining what will be coreand non-core activities is, perhaps, at the heart ofstrategic thinking within a modular supply chainand will be highlighted in the cases and discussionpresented in this paper.

Much of the research concerning supply chainstends to represent such chains as a single direct-ion relationship with value-adding activity being

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Remaining tiers…..100% 0%

3rd Tier2nd Tier 1st Tier OEM

Value-added (%)

Fig. 1. Typical value chain.

D. Doran et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 106 (2007) 2–11 3

accumulated toward the OEM (Fig. 1). Within amodular context the OEM, in an effort to achievecompetitive advantage within an environment char-acterised by over capacity, is increasingly looking tofocus upon core competencies and to developstrategies appropriate to its primary resources (Sakoand Murray, 1999; Langlois and Robertson, 1992).

Such strategies, according to Doran (2004) haveled to the development of value transfer activity(Fig. 2). Value transfer activity (VTA) reflects achain-like transfer of value-adding activities toupstream suppliers as each operation (OEM orsupplier operation) seeks to focus upon thoseactivities viewed as core to modular manufacture/supply. VTA is, perhaps, a reflection of the need forsuppliers to reorganise operations activities in aneffort to accommodate the increased levels ofproduction and management (particularly SupplyChain Management) activities passed down fromthe OEM or module assembler and the subsequentcascading of value creating activities to 2nd, 3rd or4th tier suppliers. To summarise, the benefitsassociated with modular provision seem to relateprimarily to the increased ability to accommodatenew product variations in a shortened life cycleenvironment and at lower cost, representingchanges in both market structure and marketdemands. While there are a number of differentmodular strategies available to OEMs and suppliersthe ultimate long term aim of the modular approachwithin the automotive sector is the production of

self-contained functional modules with standardisedinterfaces that can be fitted across vehicle brandsand across geographic locations.

2. Methodology

The primary purpose of this research is to assessthe impact that modular supply has had upon fourkey suppliers within a developing modular supplychain and in so doing mirrors the research logicadopted in an earlier United Kingdom (UK) study(Doran, 2004) which explored the dynamics ofsupplying within a developing modular supplychain. The research examined the key issuesassociated with supplying on a modular rather thana non-modular basis and sought to determine andcodify the issues facing suppliers positioning them-selves to supply on a modular basis. The findingsfrom the UK research indicated that supplying on amodular basis presented a number of challenges forsuppliers at the 1st, 2nd and 3rd tier levels which ledto considerable operational change and the need toconsider strategic implications associated withmodular supply. Of particular note was the appar-ent need for suppliers close to the OEM to focusupon those activities seen as key to modular supplywhile transferring to upstream suppliers thoseactivities regarded as low value-adding, non-coreactivities.

In line with the UK study a case base approachhas been utilised for the French research which

ARTICLE IN PRESS

3rd Tier

Value transfer Value transfer Value transfer

OEM 1st Tier 2nd Tier

100%

Value-added (%)

0%

Fig. 2. Value transfer activity.

OEM

Case ACockpit Module

Case BAir conditioning

Case C Injection Mouldingsupplier

Case D

Engineering consultancy

supplier supplier

Fig. 3. French case study operations.

D. Doran et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 106 (2007) 2–114

defines the unit of analysis (Yin, 1994) as the keysuppliers within the developing modular supplychain. The basis of supplier selection relatedprimarily to the degree of value creation activity(the combined value created by these suppliers is inexcess of 50% of the total module value) and to thecloseness of such suppliers to the car manufacturer;closeness in this regard is determined as a proxy forproduction criticality (Fig. 3). A number of semi-structured interviews were undertaken with staff ateach supplier operation representing managerialand operational employees and concentrating uponhow such interviewees viewed the development ofmodular supply and how modular supply hasimpacted upon their respective operations.

3. Findings

The findings will commence with a case summaryof each supplier, which is then followed by ananalysis of the case operation’s approach tomodularisation.

3.1. Case A: cockpit module supplier

3.1.1. Case summaryThe supplier was created in the late 1990s through

a Joint Venture (JV) between two major Europeanautomotive suppliers. The main aim of the JV is torespond directly to the modularity logic for auto-motive cockpits by combining the specific compe-tencies in interior systems and electronics of the twofounding companies.

The supplier operates on a just in time basis withall its OEM customers in order to deliver completecockpits modules ready to be assembled into thevehicles. Although global developments are beingconsidered, its customers are primarily Europeancar manufacturers. Apart from the final assembly ofthe cockpit module, all manufacturing activities(plastic injection/moulding, electronics, small as-semblies, etc.) are left to lower-tier suppliers. Thesupplier also manages most of the upstream supplychain (logistics, procurement, payment of sub-suppliers, etc.), as well as providing Research andDevelopment (R&D) and system integration cap-abilities.

3.1.2. Approach to modularisationThe JV has been established with a clear focus on

modularity. The supplier’s only products are the

cockpit modules that it delivers fully assembled tothe OEM.

The Serial Support Manager stated that:

One hundred percent of our activity is modular.In fact, it is part of the company’s mission thatthe company will remain focused only on themodular activities linked to the particular cockpitmodule.

The company is involved at all stages of productdevelopment (design, assembly, quality assurance,synchronous delivery, etc.) and has developed anextensive knowledge of all aspects of the cockpitmodule and of project management associated withmodularisation.

Because of our focus, all our operations are ofcourse largely influenced by the modular strate-gies [of the OEM]y In terms of SCM, thismeans that we developed and acquired the abilityto manage complete cockpit projects. Our majortask is to integrate hundreds of sub-suppliers towork more efficiently together on each project.We describe that as ‘managing the complexity’,as our task is to simplify the interface betweenthe OEMs and all those suppliers.

This approach allows the module supplier to takeresponsibility for most of the upstream SCM. Whilethe OEMs keep control of the choice of the lower-tier suppliers, the cockpit supplier undertakes allother SCM activities. On each cockpit, the supplierhas to manage several dozens sub-suppliers.

At the R&D level, the supplier also ‘‘manages thecomplexity’’ given that it is responsible for all theinterfaces between the elements of the cockpit andthe definition of the interfaces between the cockpitand the rest of the vehicle:

Although on the first projects we were onlymanaging manufacturing aspects, we are nowable to provide a complete solution to ourcustomers: from R&D to final assembly of thecockpits into the car. We are able to link theOEM’s architect knowledge to the suppliers’specific component expertise; and that is in factour main task in R&D: define the correctinterfaces inside the cockpit to optimise the workof each sub-supplier.

The manufacturing activities undertaken by thesupplier only involve the final assembly of thecockpit module and all cockpits are delivered on asynchronous basis (often delivered within less than

ARTICLE IN PRESSD. Doran et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 106 (2007) 2–11 5

30min), ‘‘right first time,’’ and to the finalcustomers’ specifications. To allow for synchronoussupply, all production sites are located near theOEM’s production sites or, in some cases, withinthe OEM’s facilities. Additionally, the supplier isresponsible for cockpit quality and fully tests allcockpits before despatch to the OEM. The com-pany’s involvement in design has allowed someelements of standardisation across their differentcustomers, especially across the different brands ofthe same car manufacturers.

Our expertise has been acquired along numerousprojects with many car manufacturers. We havedeveloped a strong expertise on the cockpitmoduley which now allows us to transfer thisexpertise on new projects. As we work with manyOEMs, we are also able to standardise somehidden components, such as the steering column,between several OEMs.

While standardisation is limited, the supplier’swork with many different OEMs has permitted adegree of standardisation for some hidden parts(e.g. airbags, cross-car beam, etc.). Despite theselimitations to standardisation, modularisation ispresented by the supplier manager as a verybeneficial approach:

In the car cockpit sector, the modular approachhas been beneficial for every aspect: cost, deliverytime, development time, cockpit weight; and wehave not faced any major issue. If we could notdeliver all these improvements, the OEMs wouldbring back these activities in-house.

These potential developments of new modularactivities highlight the groups’ confidence in thefuture growth of modular procurement by OEMs.The interviewed manager believes not only thatmore and more cockpits will be supplied onmodular basis, but that modular supply will beextended to an increasing number of components ineach car. The modular supplier’s primary focus istherefore the management of the complexity asso-ciated with car cockpits both in the developmentand production stages. A key element of thesupplier’s responsibilities is supply chain manage-ment; such management extends to the next casestudy operation.

3.2. Case B: air-conditioning assembler

3.2.1. Case summaryThe assembler is part of one of world’s top

automotive suppliers which is present on allcontinents (Europe, North America, Japan, andemerging markets) and is positioned as a majorcomponent supplier focusing on design, production,and sales to OEMs. The supplier has contracts withall major OEMs and produces electrical andthermal systems as well as transmission componentson a global basis.

The plant visited for this research producesinstrument panels for climate control (plastic injec-tion of the panel faces and assembly with panelelectronics). In addition to its important productioncapabilities, the supplier has extensive R&D cap-abilities in its numerous technical centres. Innova-tion appears to be a critical aspect of the company’spolicies and R&D expenses represent more than 5%of the group’s income.

3.2.2. Approach to modularisationThe development of a modular approach appears

to be very recent. The supplier is only involved insmall sub-assemblies (e.g. air conditioning instru-mentation vs. complete cockpit for Case A) and stillfocuses primarily on the components it produces in-house and has developed only limited SCMcapabilities that could allow the management oflarger modules (involving more sub-suppliers).

Within the company, two department managerswere interviewed: one responsible for first-tierbusiness, and one responsible for second-tier busi-ness. The first-tier business manager pointed out thecompany’s general approach to modularisation:

We still largely supply the OEMs directly.However, and in this plant in particular, a lotof our products are actually delivered to modularsuppliers assembling the components on com-plete cockpit modules. The products we stilldeliver directly (to the car manufacturers) arecomplete air-conditioning systems.

The supplier feels that it has been left behind inthe race to accommodate modularity.

It is difficult to start a modular strategy whilethere already many suppliers positioned in thismarket. To catch up on this increasing trend, wewill have to use our main strengths: we are a largeglobal supplier, and this will allow us to deliver

ARTICLE IN PRESSD. Doran et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 106 (2007) 2–116

all the cost saving promises of the modularapproach.

The supplier is currently redefining its positionregarding modular supply; several low value-addingactivities (e.g. plastic injection/moulding) are beingtransferred to lower-tier suppliers while gatheringits activities around a few core businesses andinvesting heavily in the development of newtechnologies:

Many of our European plastic injection plantshave already been soldy We are concentratingour activities around our core expertise: thermaland electrical systems and we intend to remain aleader in those fields thanks to importanttechnological developments.

Indeed, the uniqueness of its technologies allowsthe supplier to maintain a leading position in manyfields. For example, the early development ofultrasonic parking assistance systems has permittedthe supplier to impose its standards and to dominatethis specific market. Whilst the supplier makesefforts to develop modular supply, its lack ofSCM capabilities and its general lack of flexibilitymake it difficult to develop its modular offering.

A manager of the company summarised thesepoints

Whilst the modular supply model will probablybecome dominant in some areas such as cockpits,front and rear ends, engine/powertrain we arecurrently developing the capabilities to undertakesuch projects. First we have to overcome anumber of internal obstacles to allow thecompany to evolve in this direction.

The supplier has extended R&D and productioncapabilities in its area of expertise. Its recentmodular approach has been difficult to implementbecause of the company’s general lack of flexibility.The supplier is progressively taking responsibilityfor larger sub-assemblies, which has changed thenature of its relationships with its sub-suppliers;such an enlarged role has led to changes in thesupplier’s relationship with the next supplier oper-ation–Case C.

3.3. Case C: injection moulding supplier

3.3.1. Case summaryThis supplier is one of the largest European

specialists of plastic injection/moulding and oper-

ates in Hungary and France. Over 40% of itsactivity is related to the automotive industry. TheFrench plant visited for this research works only inthe automotive industry and was bought from anautomotive supplier (case B) a few years ago and, atthe moment, works only for this supplier. Thesupplier has not developed SCM or R&D capabil-ities and work is carried out on a ‘‘build to print’’basis (i.e. the supplier produces according tospecifications defined by its customers). The pro-duction expertise allows very low reject rates whichis in line with other suppliers in the same field.

3.3.2. Approach to modularisationThe supplier does not seem to have any specific

approach regarding the modularisation of thesupply chains in which it is involved. Almost all ofthe supplier’s products are now part of a modularsupply chain, which has resulted in the suppliermoving from second-tier to third-tier within thismodular supply chain. The logistics manager whoparticipated in this research summarised the com-pany’s approach to modularisation:

At the moment, all our products go through amodular supplier that assembles them on acockpit before delivering them to the carmanufacturersy In fact, the components weinject are first assembled on the steering switches(a small sub-assembly) by a large second-tiersupplier, and then passed on to the modularsupplier that assembles the cockpit.

Although this has increased the pressure on priceby their downstream clients, the overall impactupon the business has been low and the supplier hasfelt little effect of the move to modularisation. Itsonly customer remains the same: the upstreamsupplier (here, case B).

The modularization of the supply chain in whichwe are involved has had very little influenceon our operationsy and has not raised anyparticular issue.

The supplier has, however, started a process ofidentifying key value-adding activities; parts paint-ing, for example, which is outsourced to a sub-supplier is likely to be integrated to the company’score activities in order to increase the in-house valuecontribution.

The supplier’s management team is considering thistype of acquisition but remains conscious of theimportance of the company’s flexibility. The logistics

ARTICLE IN PRESSD. Doran et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 106 (2007) 2–11 7

manager insists on the influence modularisation hashad on the company and its future:

Although modularization did not change thenature of our business, it forces us to reconsiderour positioning. We must always add more valueto our customer: to do so, we will have to bringin-house operations such as painting which are atthe moment outsourcedy This must be donewithout deteriorating the company’s flexibility.

The supplier is also considering sending morework to its Hungarian facility, and sending morework to their future North African facility (near afuture OEM’s site). Such choices, which requireimportant investment, are only taken when securedwith term contracts.

3.4. Case D: engineering consultancy

3.4.1. Case summaryThis supplier is one of Europe’s largest engineering

consultancies with over 3000 staff specialised invehicle development projects. The consultancy groupis based in Germany but now operates throughoutWestern Europe and North America in facilities closeto its primary OEM customers. The type of workundertaken has evolved considerably over the last tenyears; from providing testing capabilities a decadeago, the company is now able to provide completeengineering solutions for the development of com-plete vehicles. The supplier also takes advantage ofthe trend toward more car variants based on thesame platform and has positioned itself as a partnerto those OEMs that require engineering consultingoperations for complete vehicle projects.

As part of this ‘total solutions’ approach thesupplier has developed technical competencies inelectronics and safety systems as well as enhancingand developing its project management capabilities.

3.4.2. Approach to modularisationThe supplier works on several module develop-

ment projects (approximately 30% of the com-pany’s revenues). The development of car variants(e.g. convertible, Sports Utility Vehicles, stationwagon, etc.) from a single platform is becoming akey activity. The head of the mechanics departmentinterviewed for this research emphasises the direc-tion taken by the company:

An engineering consultancy like ours can nolonger be perceived as a simple ‘testing expert’y

A large part of our business is the design andintegration of modules, and increasingly, thedevelopment of complete vehicles, including themanagement of supplier and OEM teamsthroughout the development stages.

Furthermore, despite the absence of productioncapabilities, the company is developing SCMcompetencies in order to be able to control allprocess stages along the value chain during vehicledevelopment.

The supplier takes advantage of its small size(compared to the OEMs) to be flexible and agile,which allow it to respond quickly to the OEMs fortheir technical developments.

The manager points out the importance ofmodularisation and its advantages:

In a modular context, we are given the fulldevelopment responsibility of sub-assemblies. Wecan therefore use our wide range of expertise toprovide complete solutions in compressed devel-opment timesy The platform strategy, which isessentially a ‘chassis module’, provides us withthe opportunity to develop complete vehicles.This means that we must have all the necessarycompetences.

The manager adds:

It has taken us years to develop all thosecompetencies. We are now able to design avehicle as well as a car manufacturer would, butin an even more reduced time thanks to ourflexibility and expertise. Today, we can design anentire vehicle from scratch and manage alldevelopments up to production launch. Somespecialist companies can design the engines,powertrains, electronics, and so on; Magna Steyr,for example, can undertake the entire productionand assemblyy A car can go out on the roadwithout anything else from an OEM than thelaunch decision and the brand namey There area few examples of such cars, and this trend willincrease in the future.

The supplier offers the OEMs the possibility todevelop more car variants quicker. More compe-tencies are currently being acquired to be able tooffer even more technical integration and completeproject management. The supplier seems confidentthat the trend toward more car variants oneach platform will grow and will offer moreopportunities.

ARTICLE IN PRESSD. Doran et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 106 (2007) 2–118

The manager insists on the potential growth ofthe modular approach:

Our wide range of technical competencies andproject management expertise gives us a uniqueposition. If we can provide a complete solution,the car manufacturers will find no interest inbringing back in-house such projects, and there-fore, the module approach will increase inimportance in the future.

The engineering consultancy has developedthe various competencies needed to undertake thedevelopment of complete vehicles and manage thenumerous suppliers in these development stages.

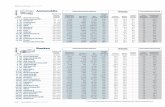

Table 1 summarises modular activities amongsteach of the case suppliers.

4. Discussion

The primary purpose of this research has been todetermine how modularisation influences the opera-

tions of key suppliers and how suppliers view theirrespective roles within a developing modular supplychain. The findings suggest that accommodatingmodular supply involves complexity, a need to focusupon core activities and the ability to recognise andreorganise activities that are not regarded as critical tothe supply of modules. Case A (the module cockpitsupplier) is a clear example of a supplier that haspositioned itself to provide modular solutions forOEMs with a coherent strategy for organising valueand developing the supply chain management skillsnecessary for the organisation and delivery of modularsolutions. Case B, however, is a newcomer to modularsupply and recognises the need to focus upon corecompetencies and has engaged in value transfer activity.However, location and people management issuesappear to inhibit moves towards modular supply. CaseC is a supplier of a commodity item and is not a keyplayer within this modular supply chain; it seems likelythat such a supplier may be consumed by productcompatible 1st or 2nd tier suppliers wishing to enhance

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Table 1Modular issues

Supplier Degree of modularactivities

Evidence of modular positioning

Case A—cockpit module supplier High Mission focussed upon modular logicHas developed extensive knowledge of all aspects ofmodularizationTakes responsibility for upstream SCMAbility to provide complete solutions for OEMsLocated close to OEMs in order to facilitate synchronous supplyMoving toward modular standardisation

Case B—air conditioning supplier Low Only involved in small sub-assembliesLimited SCM capabilitiesDelivers to module suppliers rather than directly to the OEMHas engaged in value transfer activityCurrently developing a strategy to increase modular offering

Case C—injection moulding supplier Low Has felt little impact of the move to modularisation by itsupstream customerHas started to identify areas where value can be added to itscurrent offeringLittle involvement in SCMMoved from 2nd to 3rd tier positioning within the supply chain

Case D—engineering consultancy High Facilities located close to OEMsAble to provide complete engineering solutions for thedevelopment of complete vehiclesWorks on several module development projectsFocus is upon the design and integration of modulesDeveloped its SCM competenciesGiven full development responsibility by the OEMsOffers the OEMs the possibility to develop more car variantsquicker

D. Doran et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 106 (2007) 2–11 9

their modular offerings. Case D—the engineeringconsultancy—is clearly focussed upon modular supplyand has developed its expertise in providing completemodular project solutions. It would appear that suchmodular engineering operations are likely to play anincreasing role in managing the complexity associatedwith modular supply and dealing with supply chainintegration issues associated with the move towardmodular supply.

The research findings accord with the benefits ofmodularity outlined by Sanchez and Collins (2001).However, such benefits would appear to be clusteredbetween two relationship strands—that of the OEMand the module assembler and that of the 1st tiersuppliers and the module assembler. The findings fromthis research suggest that the impact and the benefitsassociated with modularisation naturally dissipate asone moves towards 2nd and 3rd tiers of the supplychain. This said, one can also observe that thosesuppliers that might be regarded as distant from themodular epicentre are modularising to a lesser degreeby examining value transfer activity and value creationactivities that, in their own way, could be regarded asmodular activity, albeit at a more localised level. Thefindings also demonstrate that the issues of complexitynoted by Camuffo (2000) and Carliss et al. (1997) wereevident to some degree; however, those suppliers thatclearly see modularisation as a future operations modeltended to view modularisation in a more holisticmanner and were positioning themselves to providesolutions which reduce the complexity associated withthe modular logic while moving toward what Helperet al. (1999) described as ‘‘self-contained functionalunits with standardised interfaces within one or morestandardised product architectures, units conceived,manufactured or supplied, and assembled as autono-mous ‘‘modules.’’ In many respects the French casestudies broadly followed the findings of the UK-basedresearch (Doran, 2004), particularly in terms of thedevelopment of SCM capabilities of suppliers closeto the OEM (cases A and B) and the focus uponidentifying key value-adding activities and transferringnon-core activities to upstream suppliers (Table 1).Perhaps the key difference between the findings fromthe UK study when compared to the French study isthe important role played by the engineering con-sultancy (Case D). It seems apparent that as manu-facturing suppliers continue to concentrate upon keymodule activities the role played by engineeringconsultancies is likely to grow and will encompass avariety of activities that would have been regardedas key supplier activities less than five years ago—

particularly in terms of full module engineeringsolutions, development of SCM capabilities and theresponsibility to provide complete engineering solutionsfor the development of complete vehicles.

5. Implications and limitations

The implications associated with the developmentof modules are likely to be manifest in a number ofways and in a number of areas. Firstly, the modularlogic necessitates a new type of supplier—a supplierthat can ‘manage the complexity’ associated withintricate products and can also manage thoseupstream suppliers that contribute to the variouselements that constitute a module. In addition, asOEMs continue to transfer value to moduleassemblers it is likely that such suppliers will inturn seek to transfer non-core elements of theiractivities to 2nd and 3rd tier suppliers, resulting inwhat can be termed value transfer activity. Examin-ing the impact of modularisation through a macro-economic lens it seems apparent that there will beshifts in the location of suppliers as well asclustering and merging of suppliers that possessmodule complementarities. On a more general level,it would appear that modularisation is likely torequire a shift of research focus, particularly interms of issues relating to buyer–supplier relation-ships and issues relating to the debate concerninglean and agile production (again the debate maymove from its current OEM focus to a focus uponthose suppliers that supply high value modules andare in effect charged with managing production).

While the above findings indicate that modular-isation has a significant impact upon variouselements of modular supply chains one must notethat this research presents the findings of anexamination of a single supply chain and as suchdoes not attempt to suggest that the findings areuniversally applicable across the sector nor are theylikely to determine the approach adopted fordifferent modules within different OEMs in differ-ent locations. Moreover, the automotive sector as awhole does not have an industry view on whatconstitutes modularity and does not appear to bemoving toward the modular ‘plug and play’approach adopted in the computer sector wheremodules are completely interchangeable.

Appendix A

See Fig. A1.

ARTICLE IN PRESSD. Doran et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 106 (2007) 2–1110

References

Camuffo, A., 2000. Rolling out a ‘‘World Car’’: globalization,outsourcing and modularity in the auto industry. IMVPworking paper (http://imvp.mit.edu/papers).

Carliss, Y., Baldwin, Clark, B., 1997. Managing in the age ofmodularity. Harvard Business Review September–October,84–93.

Doran, D., 2004. Rethinking the supply chain: an automotiveperspective. International Journal of Supply Chain Manage-ment 9 (1), 102–109.

Helper, S., MacDuffie, J.P., Pil, F., Sako, M., Takeishi, A.,Warburton, M., 1999. Project report: modularization andoutsourcing: implications for the future of automotiveassembly. Paper prepared for the IMVP Annual Forum,MIT, Boston, 6–7 October.

Langlois, R., Robertson, P., 1992. Networks and innovation in amodular system: lessons from the microcomputer and stereocomponents industries. Research Policy 21, 297–313.

McAlinden, S., Smith, B., Swiecki, B., 1999. The future ofmodular automotive systems: where are the economicefficiencies in the modular-assembly concept? UMTRI ReportNo. 2000-24-1.

Sako, M., Murray, F., 1999. Modular strategies in cars andcomputers. Financial Times December (6).

Sanchez, R., Collins, R., 2001. Competing—and learning—inmodular markets. Long Range Planning 34 (6), 645–667.

Velos, F., Kumar, R., 2002. The automotive supply chain: globaltrends. ERD Working Paper. www.adb.org/Documents/ERD/Working_Papers/wp003.pdf.

Yin, R., 1994. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Sage,Beverly Hills.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Fig. A1. Definition of a cockpit module. Example shows ‘‘Class 1’’—cockpit.

D. Doran et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 106 (2007) 2–11 11