Social support as a buffer in the relationship between socioeconomic status and academic performance

Transcript of Social support as a buffer in the relationship between socioeconomic status and academic performance

School Psychology Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 4, 2006, pp. 375-395

Social Support as a Buffer in the Relationshipbetween Socioeconomic Status and Academic

Performance

Christine Kerres Malecki and Michelle Kilpatrick DemarayNorthern Illinois University

The present study was an investigation of the potential moderating effect of socialsupport on academic performance for students living in poverty. Data were col-lected in one urban middle school from 164 primarily Hispanic students using theChild and Adolescent Social Support Scale (CASSS; Malecki, Demaray, & Elliott,2000) and students' course grade point averages (GPA). Regarding socioeconomicstatus (SES), students were classified as lower-SES if they received free or re-duced-cost lunches or higher-SES if they did not receive free or reduced-costlunches. First, for students with higher SES, correlational analyses revealed no sig-nificant associations between social support and academic performance as mea-sured by GPA. Alternatively, for students of lower SES, significant, moderateassociations were found between GPA scores and social support scores. Second, aspredicted, regression analyses provided evidence that social support may moder-ate the relationship between poverty and academic performance. Implications forschool psychologists and suggestions for future research are provided.

Current statistics provide evidence that an increasing number of thecountry's adolescents (20-40%) are at risk for school failure (EducationalResource Information Center, 1999; Natriello, McDill, & Pallas, 1990).Moreover, the number of students living in poverty is also predicted toincrease (Clearinghouse on Urban Education, 2001; Natriello et al.,1990). Specifically, Natriello et al. (1990) predicted that by the year 2020approximately 25% of students will be living in conditions of poverty.Although poverty status is but one factor that puts a child at risk for fail-ure in school, there is evidence that poverty status is a strong predictorof lower academic performance among children and adolescents

Authorship is listed in random order. Both authors contributed equally to the preparationof this article.

Address correspondence to Christine K. Malecki, Northern Illinois University, Depart-ment of Psychology, DeKalb, IL 60115; E-mail: [email protected].

375

376 MALECKI AND DEMARAY

(Caldas & Bankston, 1997; Hecht & Greenfield, 2001; Rank & Hirschl,1999). Due to this link between academic performance and poverty sta-tus, it is crucial to further investigate contextual factors that could poten-tially buffer the deleterious effects of poverty on children's performancein school. One such potential buffering factor is social support. Thus, thecurrent study will utilize a buffering model to investigate therelationships among poverty status, social support, and academicperformance.

POVERTY AS A RISK FACTOR

Several studies have provided substantial evidence of a link betweenlow academic performance and low socioeconomic status SES (Caldas &Bankston, 1997; Hecht & Greenfield, 2001; Ma, 2000; Okpala, Okpala, &Smith, 1995; Okpala, Smith, Jones, & Ellis, 2000). For example, Caldasand Bankston (1997) found that along with several other salient charac-teristics, students' participation in a free or reduced-cost lunch programhas an independent, significant, negative relationship with high schoolstudents' standardized achievement scores. Okpala et al. (2000) foundthat a school's percentage of free/reduced-cost lunch program partici-pants was significantly and negatively related to students' reading andmath achievement. In one study (Ma, 2000) it was found that even takingother salient school and family characteristics into account, significantrelationships existed between students' SES and their academic achieve-ment across all core subject areas (reading, math, writing, and science).Thus, the literature has provided evidence that students' poverty status(often measured via free /reduced-cost lunch program status) is relatedto their academic performance in school.

For racial and ethnic minority youth, poverty and lagging academicachievement are particularly salient concerns. For example, according tothe U.S. Census Bureau (2002), 29 percent of racial minority children un-der 18 live in conditions considered to be below poverty level comparedto 9.5 percent of non-Hispanic White children. Furthermore, many re-searchers have found that SES was a significant predictor of academicachievement for minority youth (Battle, 2002; Mickelson, 1990). Consis-tent with the need to study this phenomenon and identify potential in-tervening factors, the sample of students in the current study consistedpredominantly of racial and ethnic minority students.

SOCIAL SUPPORT

Social support is defined as one's perceptions of supportive behaviorsfrom individuals in his or her social network (e.g., parents, teachers,

SOCIAL SUPPORT AS A BUFFER 377

classmates, close friends, school), that enhance functioning and/or maybuffer him or her from adverse outcomes (Malecki & Demaray, 2002).Tardy (1985) described social support as being from multiple sources(e.g., parents, friends, teachers, etc.) and of multiple types (e.g., emo-tional, appraisal, instrumental, and informational). Emotional supportrefers to caring behaviors from others. Appraisal support consists offeedback or evaluative information provided to someone. Resources,such as time or money provided to someone in need, are instrumentalsupport. Finally, information support consists of providing needed in-formation or advice. Social support can also be given or received and canbe actualized or simply available to people. In the current study, socialsupport was operationalized via Tardy's model and was conceptualizedas the support that students perceive as being available to them from theirparents, teachers, classmates, close friends, and their schools. The mea-sure used in the current study also represents Tardy's four types ofsupport (emotional, appraisal, informational, and instrumental).

Social Support and Academic Achievement

Previous research has found somewhat weak evidence for a link be-tween social support and academic performance. For example, when in-vestigating the relationship between social support and grade pointaverage (GPA) in a sample of seventh through 12th-graders, Maleckiand Elliott (1999) found a small but significant relationship between stu-dents' perceived support and their overall GPA. Additionally, theyfound a small, significant relationship between teacher support andGPA. Rosenfeld, Richman, and Bowen (2000) found that students withhigh support from three sources (parents, teachers, and friends) hadbetter grades in a large, representative sample of middle and high schoolstudents than did students without such support. Although these stud-ies indicate that there may be a relationship between social support andGPA, the evidence is not strong. Perhaps there are other factors that in-fluence the relationship between social support and academic perfor-mance that these researchers were unable to consider. For example,social support may be related to academic performance for some stu-dents but not for others. The current study is an investigation of one ofthese factors, students' SES.

Social Support as a Buffer

The resilience literature discusses potential protective factors, one ofwhich is social support, for students in high risk settings or for studentsunder stress (Becker & Luthar, 2002; Garmezy, Masten, & Tellegen, 1984;

378 MALECKI AND DEMARAY

Luthar, 1991; Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000). For example, in a reviewof the literature, Becker and Luthar (2002) found that parent and teachersupport are two important factors contributing to the success of disad-vantaged students. Peer support was found to be an important contrib-uting factor, depending on the values of the peer group (Becker &Luthar, 2002).

There have been several studies regarding the buffering relationshipbetween social support and academic achievement; however, the resultsand conclusions have been somewhat inconsistent. For example, a studyby Dubow and Tisak (1989) investigated the role of social support forchildren under stress and found a relationship between social supportand GPA. Additionally, Gillock and Reyes (1999) found a significant re-lationship between GPA and teacher support in a sample of tenth-grade,low-income, Mexican American students. Levitt, Guacci-Franco, andLevitt (1994) found a significant relationship between social support andstandardized test scores in a sample of multi-ethnic (African American,Hispanic American, and White) students; however, a relationship wasnot found between social support and GPA.

The results from the aforementioned studies may be interpretedwithin the resilience framework as demonstrating a process of resilience,with social support playing a protective-stabilizing role (Luthar et al.,2000). That is, social support may act as a stabilizing factor for studentsso that if a student has adequate social support in his or her life, his or heracademic achievement will be less likely to be affected by poverty statusor other risk factors. Researchers have investigated this phenomenonand have documented that social support plays a buffering role, leadingto a wide variety of positive outcomes for students (e.g., Becker &Luthar, 2002; Dubow & Tisak, 1989). However, as discussed previously,when investigating the relationship between social support and stu-dents' academic achievement the results have been mixed. Thus, thegoal of the current study was to examine a potential buffering effect ofsocial support on the academic performance of students of low SES.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND PREDICTIONS

The results of research relating social support and academic competencehave been somewhat inconsistent. Those findings that have been signifi-cant have demonstrated low to moderate associations between supportand academics. However, it is hypothesized that this relationship maydiffer for students of varying populations or situations. Thus, the goal ofthe current study was to examine this relationship for students of lowerand higher SES.

SOCIAL SUPPORT AS A BUFFER 379

Prediction 1

First, due to the relationship that social support has with a variety ofother outcomes (Cauce, Felner, & Primavera, 1982; Piko, 2000; White,Bruce, Farrell, & Kliewer, 1998), it was predicted that social supportwould be related to academic performance. However, under a resilienceor buffering theoretical orientation, it was predicted that this relation-ship would be more salient for students of lower SES than for those ofhigher SES.

Prediction 2

Furthermore, it was predicted that evidence would be found that socialsupport plays a moderating role (Baron & Kenny, 1986) in the relation-ship between SES and academic performance. Specifically, it was pre-dicted that evidence would be found for social support potentiallybuffering the effects of lower SES when examining students' academicperformance.

METHOD

Participants

This study utilized data from a total of 164 students in grades 6,7, and 8from an urban middle school in Illinois. See Table 1 for the sex, grade,and ethnicity of the sample. In addition, the ethnicity of the participantsin the current study can be compared to the ethnic breakdown of the en-tire school in the table note. All students were classified into two differ-ent groups based on SES; students receiving free (n = 93) or reduced-costlunches (ft = 17) were classified as having lower SES (n = 110, 67%) andthose not receiving free/reduced-cost lunches were classified as havinghigher SES (n = 54, 33%).

The school from which this sample is drawn from is in a low-incomeurban setting with approximately 68% of the students in the schoolqualifying as low-income. The community in general would be classi-fied as a lower middle-class to poverty-level area. Thus, even the stu-dents who did not qualify for free or reduced-cost lunches were likelyfrom lower middle-class families. The high percentage of Hispanicstudents in this community and school were primarily of Mexican de-scent. At the time of the study, this school was on the State of Illinois ac-ademic warning list with high numbers of academicallyunderperforming students.

380 MALECKI AND DEMARAY

TABLE 1. Participant Characteristics Overall and by SES

Sex

Boy

GirlGrade

6

7

8

EthnicityAfrican AmericanAsian AmericanLatinoWhiteOther

Total

N

83

81

57

75

32

31

2

106

13

12

%

50.6

49.4

34.8

45.7

19.5

18.9

1.2

64.6

7.9

7.3

SES Status

Lower

N

60

50

39

57

14

24

2

72

6

6

%

54.5

45.5

35.5

51.8

12.7

21.8

1.8

65.5

5.5

5.5

HigherN

23

31

18

18

18

7

0

34

7

6

%

42.6

57.4

33.3

33.3

33.3

13.0

0

63.0

13.0

11.1

Note. The ethnic make up of the entire school was 11.2% White, 25.4% African American, 62.3% Latino,.7% Asian/Pacific Islander, and .4% Native American.

Materials

Students' school records were accessed to document students' free/re-duced lunch cost status. Total GPA and grades in core courses (e.g.,reading, language, social studies, math, and science) were also obtainedvia school records for each participant. Students' perceptions of socialsupport were gathered via a student-completed rating scale, the Childand Adolescent Social Support Scale (CASSS; Malecki, Demaray, &Elliott, 2000).

SES. Students' free/reduced lunch status was collected as an indica-tor of students' SES (with a focus on financial rather than human or so-cial factors). Although some researchers have argued against usingfree/reduced-cost lunch status as a measure of SES (Entwisle & Astone,1994; Hauser, 1994), a recent empirical investigation of the validity ofmeasures of SES for adolescents reported that free and reduced-costlunch status showed strong correlations with other measures of SES, in-cluding family income (Ensminger et al., 2000).

Classroom Grades. Students' quarterly report card grades for Read-ing, Language, Social Studies, Math, and Science were recorded. All par-ticipating students had grades for all five subject areas. The first-

SOCIAL SUPPORT AS A BUFFER 381

through fourth-quarter grades were averaged to form a Total GPA forthe year in each subject. Additionally, a Total GPA for the year was com-puted by averaging these five grades. The grades were on a five-pointscale with "A" being 4 and "F" being 0. Correlations among the individ-ual subject area grades and the Total GPA ranged from .74 to .87.

Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale (CASSS; Malecki et ah,2000). The CASSS (2000) is a 60-item rating scale measuring perceivedsocial support from five sources: parents, teachers, classmates, closefriends, and school. Items on the CASSS (2000) consist of statementssuch as, "My parent(s) help me make decisions." Students respond byrating each item on two aspects: frequency and importance. Frequencyratings consist of a six-point Likert scale (1 = Never to 6 = Always) andimportance ratings consist of a three-point Likert scale (1 = Not Impor-tant to 3 = Very Important). Each subscale corresponds to one of fivesources of support and consists of 12 items that measure emotional, in-formational, appraisal, and instrumental support. Subscale frequencyscores are calculated by summing the frequency ratings on the 12 itemson each subscale (Parent, Teacher, Classmate, Close Friend, and School).In addition, a total frequency score can be calculated by summing all fivefrequency subscale scores. Subscale and total importance scale scorescan be computed using the importance ratings but are intended primar-ily for use in clinical interpretation and were not examined in this study.A Spanish version of the CASSS (2000) has been created as part of itsdevelopment.

The CASSS (2000) is a revision of an earlier instrument (Malecki,Demaray, Elliott, & Nolten, 1999) that had sound psychometric charac-teristics (Malecki & Demaray, 2002). The CASSS (2000) was updated byadding a subscale that taps overall school support and by adding or re-distributing items to create an equal number of items pertaining to thefour types of support (emotional, appraisal, informational, and instru-mental) within each of the five source scales (parent, teacher, classmate,close friend, and school). Data providing evidence for the reliability andvalidity of the CASSS (2000) has been produced as part of three pub-lished studies (Demaray & Malecki, 2002; Demaray & Malecki, 2003;Malecki & Demaray, 2003). These studies included data from a total of903 students in grades 5 through 8 from Illinois and New York. Morethan half of these students were from schools similar to those in the cur-rent sample (primarily Hispanic, low-income, urban population). TheSpanish version of the CASSS was used with approximately five percentof the students in these samples.

These psychometric data include a factor analysis that indicated aclear five-factor structure corresponding to the parent, teacher, class-mate, close friend, and school subscales. Factor loadings ranged from .52

382 MALECKI AND DEMARAY

TABLE 2. Means and Standard Deviations on Total Social Support and Total GPA byGender, Grade, and SES

GenderBoys (n = 83)

Girls (n = 81)

Grade6th (n = 57)

7th (n = 75)

8th (n = 32)

SESLower SES (n = 110)

Higher SES (n = 54)

MSDM

SD

MSDM

SDM

SD

MSDM

SD

Total Social Support

222.9555.14

258.3943.65

247.5950.50

237.2256.10

235.32

48.53

239.3954.93

242.62

48.36

Total GPA

2.39.84

2.58.80

2.41

.832.44

.82

2.73.81

2.36.82

2.73.80

to .81 within each factor with no dual loadings above .30. Theeigenvalues for the five factors ranged from 19.07 to 2.67. Reliabilityanalyses have revealed evidence that scores on the CASSS (2000) dem-onstrate strong internal consistency with a = .96 for the Total score andranging from .92 to .96 on the subscale scores. Furthermore, evidencewas found for 8 to 10-week test-retest reliability (r = .78). The CASSS(2000) Total score had a significant correlation of .55, p < .001 with the So-cial Support Scale for Children (SSSC; Harter, 1985). Furthermore, theinternal consistency of the CASSS (2000) was demonstrated in the pres-ent study with coefficient alphas of .96 for the Total Support score, and.93, .92, .92, .95, and .93 for the Parent, Teacher, Classmate, Close Friend,and School subscales, respectively.

Procedure

Parental consent was collected for all students participating in the studyduring a school-sponsored parent conference night that all parents wererequired to attend. Of the 571 students enrolled at the participatingschool, 203 (36%) students' parents provided consent to participate.Written student assent to participate was collected for all participants.Of the 203 students, 39 students were removed from the dataset due to

SOCIAL SUPPORT AS A BUFFER 383

TABLE 3. Means and Standard Deviations of Social Support and GPA Overall and by SES

Total Social Support

Parent Support

Teacher Support

Classmate Support

Close Friend Support

School Support

Total GPA

Reading GPA

Language GPA

Social Studies GPA

Math GPA

Science GPA

MSDM

SDM

SDM

SDM

SDM

SDM

SDM

SDM

SDM

SDM

SDM

SD

Total Sample240.4552.7355.4512.3749.2012.9742.6914.3649.4816.3743.6314.052.48

.832.62

.992.421.002.32

.902.461.012.641.09

SESLower239.3954.9354.7612.6349.4613.7243.0614.1548.9717.1543.1314.752.36

.822.49

.992.331.032.18

.892.36

.972.501.12

Higher242.6248.3656.8611.8148.6711.3841.9414.8850.5014.7444.6512.592.73

.802.89

.922.60

.912.61

.862.671.062.91

.96

incomplete data, resulting in a final sample of 164 students (81%). Partic-ipants were grouped (approximately 10-12 students) by their seating ar-rangements. Each group had one research assistant available to answerindividual questions and to make sure that students were completingthe forms correctly. The CASSS was read aloud by a researcher and allparticipants followed along as each item was read. In addition, some ofthe students completed the CASSS in Spanish and for those students, abilingual staff person was available to read aloud the items (in Spanish)and help them as needed. Grades and SES data were collected fromstudents' records.

RESULTS

First, results of two preliminary analyses are presented. Next, results ofthe main research questions are presented. See Table 2 for means and

384 MALECKI AND DEMARAY

TABLE 4. Intercorrelations among All Key Variables (SES, Social Support, and GPA)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

1. SES .08 .03 .04 -.04 -.05 -.03 -.20 -.13 -23 -.15 -.18 -.21

2. Parent Support — .34 .27 .28 .39 .58 .28 .25 .26 .16 .19 .26

3. Teacher Support — .46 .49 .63 .77 .34 .32 .19 .13 .27 .30

4. Classmate Support — .65 .45 .77 .19 .19 .08 .14 .13 .17

5. Cl. Friend Support — .52 .81 .25 .24 .13 .13 .07 .20

6. School Support — .80 .30 .26 .15 .07 .17 .23

7. Total Support — .35 .33 .21 .17 .22 .30

8. Reading GPA — .80 .66 .48 .65 .87

9. Language GPA — .58 .45 .58 .83

10. Social Studies GPA — .54 .66 .82

11. Math GPA — .57 .74

12. Science GPA — .85

13. Total GPA —

standard deviations on Total Social Support and Total GPA by gender,grade, and SES. Table 3 presents means and standard deviations for themain variables, social support, and GPA for the total sample and by SES.See Table 4 for correlations conducted with the entire sample among allkey variables.

Preliminary Analyses

Two preliminary analyses were conducted to investigate gender, gradelevel, and SES (higher vs. lower) differences in the primary dependentvariables (Total Social Support and Total GPA). First, an ANOVA wasconducted on Total Social Support by gender, grade level, and SES. Forsocial support, there was a significant gender main effect, F(l, 152) =10.17, p <.01, with girls scoring higher than boys. There was not a signifi-cant grade main effect, F(2,152) = .59, p = .56, or SES main effect, F(l, 152)= .12, p = .73. Lastly, none of the interactions were significant. Second, anANOVA was conducted for Total GPA, finding no gender main effect,F(l, 152) = 1.89, p = .17, or grade main effect, F(2,152) = .99, p = 37. As ex-pected, there was a significant SES main effect, F(l, 152) = 7.07, p < .01,with students who receive free/reduced-cost lunches (lower SES) hav-ing lower GPA scores than students not receiving free/reduced-costlunch. None of the interactions were significant.

SOCIAL SUPPORT AS A BUFFER 385

TABLE 5. Correlations among Social Support and GPA Scores

GPA

Total

Reading

Language

Social Studies

Math

Science

SES

Higher

Lower

Higher

Lower

Higher

Lower

Higher

Lower

Higher

Lower

Higher

Lower

Total

.06

.40**

.04

.48**

.09

.42**

.08

.27

.15

.18

-.03

.30

Social Support

Parent Teacher Classmate

-.01

.36**

.05

.36**

.01

.34**

.10

.32**

.01

.22

-.12

.30

.18

.37**

.12

.44**

.14

.40**

.13

.23

.26

.10

.15

.33**

-.05

.30

-.09

.33**

-.05

.31

-.06

.17

.11

.16

-.07

.24

Friend

.04

.25

.05

.32**

.13

.28

.06

.16

.07

.15

-.08

.12

School

.10

.27

.05

.38*

.13

.30

.10

.16

.12

.04

.04

.22

Note. **Using the Bonferroni method, only correlations significant at or less than .0007 were reported tokeep the p for correlational analyses at .05. Sets of correlations in bold are significantly different for stu-dents with higher SES than those with lower SES (p < .05 to p < .01).

Prediction 1: Relationship among Social Support and GPA Scores

Correlations were computed separately for the subsamples of studentsclassified as lower- and higher-SES. To avoid the problem of Type I errordue to the number of correlations conducted (72), only results significantat .0007 were noted (obtained by dividing .05 by the number of correla-tions, according to the Bonferroni method). All correlations for bothgroups (lower SES and higher SES) can be found in Table 5. No signifi-cant relationships were found between social support and GPA for stu-dents with higher SES. All correlations were low, as predicted, and werenonsignificant (using criterion of p < .0007). Alternatively, as predictedmany of the correlations for students with lower SES were moderate andsignificant among social support scores and GPA. For example, the rela-tionship between Total Social Support and Total GPA and Total SocialSupport scores and Reading and Language GPA scores were allsignificant.

Comparing Correlations for Lower SES and Higher SES Students. Al-though a visual analysis of the data suggests that the relationship be-tween social support and academic indicators is much stronger for stu-dents with lower SES than students with higher SES, a series of Fisher r toz transformation procedures was conducted to determine if these relation-ships were statistically different. The transformations were only conducted

386 MALECKI AND DEMARAY

when at least one of the correlations to be compared was statistically signifi-cant. Several of the correlations for the lower-SES sample were significantlystronger than for the higher-SES sample including those between Total Sup-port and Total, Reading, and Language GPA scores. All relationships thatwere significantly different from one another are noted in Table 5.

Prediction 2: Social Support as a Moderator between SES and GPA

To examine the possibility of social support serving as a moderator inthe relationship between SES and GPA, five simultaneous multiple re-gression analyses were conducted. The procedures followed were basedon Baron and Kenny (1986) and Aiken and West (1991). Social supportwas predicted to be a moderator because the relationship between SESand GPA was predicted to be different based on the level of social sup-port students perceived. Prior to analyses, the SES score was dummycoded as lower-SES = 0 or higher-SES = 1 (M = .329, SD = .471). The socialsupport source scores (parent, teacher, classmate, close friend, andschool) were centered as recommended by Aiken and West. Thus, all so-cial support source scores after centering had a mean of zero.

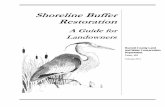

For all regression analyses, the dependent variable was Total GPA (M= 2.48, SD = .826). The independent variables always consisted of SESand a social support score (parent, teacher, classmate, close friend, orschool) in the first step and the SES by respective social support score in-teraction in the second step. Thus, in the first regression, the predictorswere SES and parent support in the first step, with the SES by parent sup-port interaction entered in the second step. The same procedure was fol-lowed for the remaining four regressions with different sources of sup-port (teacher, classmate, close friend, and school). See Table 6 for specificregression results. In summary, both steps of all five regressions weresignificant. In addition, every independent variable in the regressions(SES and support source) was a significant individual contributor (withthe exception of the interaction terms). With regard to the interactions,both the SES by parent support and the SES by classmate support inter-actions were significant. These interactions were probed using proce-dures outlined for probing significant interactions in multiple regres-sion described by Aiken and West (1991). These procedures arerecommended to understand the meaning of the interactions. Aiken andWest first recommend plotting the interaction followed by post hocstatistical testing. See Figure 1 for the plotting of both obtainedsignificant interactions.

The post hoc statistical testing of interactions described by Aiken andWest (1991) allows one to test the "significance of the simple slopes of re-gression lines at single values of a second predictor" (p. 14). For the sig-

SOCIAL SUPPORT AS A BUFFER 387

FIGURE 1. Parent and Classmate Social Support Moderating the Relation between SESand GPA. Note. The low-support group consists of students with social support scoresone standard deviation below the mean. The high-support group consists of students

with social support scores one standard deviation above the mean.

nificant SES by parent support interaction the simple slope for low-par-ent-support students was significant, £(161) = 23.69, p < .001. That is, forstudents with low parent support, those who had low SES had lowerGPA scores than students with higher SES. As a contrast, the simple

388 MALECKI AND DEMARAY

TABLE 6. Regression Analyses of SES and Social Support Scores Predicting GPA

Stepi *»*

2***

2***

2***

1**

9***

i * * *

2**

i * * *

2***

Independent Variable

SES*

Parent Support**

SES**

Parent Support***

SES x Parent Support*

SES**

Teacher Support***

SES**

Teacher Support***

SES x Teacher Support

SES**

Classmate Support*

SES**

Classmate Support**

SES x Classmate Support*

SES**

Close Friend Support*

SES**

Close Friend Support**

SES x Close Friend Sup-port

SES**

School Support**

SES**

School Support**

SES x School Support

B

-.332

.016

-.350

.023

-.023

-.381

.020

-.378

.022

-.009

-.377

.010

-.370

.017

-.020

-.351

.009

-.357

.012

-.010-.346

.013

-.352

.015

-.009

SEB

.131

.005

.130

.006

.011

.128

.005

.129

.005

.011

.133

.004

.131

.005

.009

.133

.004

.133

.004

.009

.132

.004

.132

.005

.010

3-.189

.242

-.200

.347

-.192

-.217

.306

-.216

.343

-.074

-.215

.178

-.211

.298

-.203

-.200

.186

-.204

.237

-.099-.198

.215

-.201

.255

-.078

R2

.102

.127

.137

.141

.075

.102

.078

.085

.090

.094

AK2

.026*

.004

.027*

.007

.004

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

slope for the students with higher parent support was not significant.Thus, for students with lower SES and students with higher SES, GPAscores were similar. This same pattern was observed for the SES by class-mate support interaction. The simple slope for low classmate supportwas significant, £(161) = 25.40, p < .001. Again, the simple slope for highclassmate support was not significant. Figure 1 illustrates these signifi-cant interactions by showing the plots of means for high- and low-sup-port groups (students with scores one standard deviation above andbelow the mean) by high- and low-SES status.

SOCIAL SUPPORT AS A BUFFER 389

DISCUSSION

Previous research has shown that social support is moderately tostrongly related to many personal, clinical, health, and social indicatorsfor school-aged children and adolescents (Cauce et al., 1982;Licitra-Kleckler & Waas, 1993; Piko, 2000; Uchino, Cacioppo, &Kiecolt-Glaser, 1996; White et al., 1998). However, the empirical evi-dence for associations between social support and academic indicatorshas been less convincing. Additionally, few studies have examinedthese relationships within a resilience theoretical orientation. Thus, thepresent study was an investigation of the potential buffering role of so-cial support (Cohen, Gottlieb, & Underwood, 2000) on the academic per-formance of a group of urban middle school students. Specifically, it washypothesized that social support may play a moderating role betweenSES and academic performance.

Several preliminary analyses investigated potential gender, gradelevel, ethnicity, and SES status differences on GPA and social support.Regarding GPA, the only demographic difference found was that stu-dents of lower SES had lower GPAs than students with higher SES. Thisresult was expected, as previous researchers have found that studentsliving in poverty fare worse in academic performance than students notliving in poverty (Caldas & Bankston, 1997; Hecht & Greenfield, 2001;Ma, 2000; Okpala et al., 1995; Okpala et al., 2000).

Regarding social support, girls scored significantly higher than boys.This gender effect was expected and has been found numerous times inthe literature (Demaray & Malecki, 2002; Frey & Rothlisberger, 1996;Jackson & Warren, 2000; Lifrak, McKay, Rostain, Alterman, & O'Brien,1997; Schraedley, Gotlib, & Hayward, 1999). No other demographic dif-ferences were found in social support or GPA scores. These findingsshould be interpreted with caution given that the current sample wasnot representative of the general population (see Limitations).

As predicted, different trends were found in the relationship betweensocial support and grades for students of low SES versus those classifiedas having higher SES. Specifically, for students of higher SES,correlational analyses found no significant associations between socialsupport and academic achievement as measured by GPA. Alternatively,for students of low SES, significant, moderate associations were foundbetween GPA scores and social support scores. Specifically, for studentsof low SES, total support was related to Total, Reading, and LanguageGPA; parent support was related to Total, Reading, Language, and Sci-ence GPA; and teacher support was related to Total, Reading, Languageand Social Studies GPA. Classmate, close friend, and school supportwere related to Reading GPA. The relations found between teacher sup-

390 MALECKI AND DEMARAY

port and academics are consistent with previous research that has foundteacher support as the source most likely to be related to GPA (Gillock &Reyes, 1999; Malecki & Elliott, 1999; Rosenfeld et al., 2000).

Regression analyses confirmed that SES and support from parents,teachers, classmates, close friends, and the school are significantly re-lated to students' GPAs. Thus, both SES and social support contribute toGPA. However, of primary interest was the finding that social supportserves as a moderator in the relation between SES and GPA for both par-ent and classmate support (not teacher, close friend, or school). That is,for students with lower parent or classmate support, they had a higherGPA if they had higher SES and a lower GPA if they had lower SES. Thisresult is expected given the research establishing a link between SES andGPA, but furthermore establishes that this link exists when studentshave lower levels of social support. For students with higher social sup-port, GPA scores were stable regardless of their SES status. That is, stu-dents with higher social support and lower SES had similar GPAs to stu-dents with higher social support and higher SES. This same trend wasfound for classmate support. Overall, as predicted, social support maybe playing a protective-stabilizing role in the relationship between SESand academic performance for students of low SES. It should be notedthat Figure 1 illustrates that a difference of approximately two standarddeviations in social support scores (parent and classmate) results in amodest one-half score increase in students' GPA (e.g., 2.0 to 2.5 GPA).However, collectively, these results suggest that for students of low SES,the relationship between social support and their performance in schoolis a salient one.

The implications of these findings are important, as students of lowSES (defined in the present study as participation in the free/re-duced-cost lunch program) are indeed those students most in need of in-terventions that may buffer the challenges inherent in poverty and facili-tate academic success for those students (Caldas & Bankston, 1997;Hecht & Greenfield, 2001; Ma, 2000; Okpala et al., 1995; Okpala et al.,2000). For students of low SES, social support may be an important vari-able that facilitates students' abilities to benefit from instruction (Elliott,Malecki, & Demaray, 2001). Although this study was not a broaderstudy of "resilience," it can be argued that these findings lend evidencethat social support could be a protective factor that takes into accountseveral contexts (the individual, the school, and the family) and is by na-ture a construct that crosses those contextual boundaries (Luthar et al.,2000; Pianta & Walsh, 1998).

Students in many schools are at risk of academic failure, and many ed-ucators and school psychologists are working hard to design and imple-ment interventions aimed at preventing this negative outcome for stu-

SOCIAL SUPPORT AS A BUFFER 391

dents. Research such as the present study can help provide furtherunderstanding of how social interventions may directly or indirectly berelated to the students' academic performance, especially for students oflow socioeconomic status. For example, given that adult social supportwas found to be related to GPA for students of lower SES and given pastresearch on the importance of adult social support on many other out-comes (e.g., Demaray & Malecki, 2002), increasing the adult support instudents' lives may be one relevant intervention goal in an overall inter-vention plan. For example, several interventions may be helpful particu-larly for students of low SES such as: (a) increasing parental involve-ment in students' schools, (b) providing teacher training on the types ofsocial support that they can provide students and how they can do so, (c)implementing peer tutoring to increase opportunities for students to ex-pand the classmate support they perceive, or (d) focusing on the poten-tially isolating effect that being of low SES may have for students andincreasing both the adult and peer social networks for those students.

Limitations and Future Research

The present study defined low SES via participation in the school's freeor reduced-cost lunch program. This method can be problematic as itcan miss students who qualify for the program but do not participate, orit may not take Into account the length of time a student has been livingin poverty (Ensminger et al., 2000). In addition, SES is a broad constructthat includes not only financial indicators (e.g., free/reduced-cost lunchprogram status) but also human and social factors (e.g., parental educa-tion, single-parent status, parental employment) (Ensminger et al.,2000). However, Ensminger et al. (2000), Entwisle and Astone (1994),and Mechanic (1989) all argue that even when including several factorswhen gaining a broad measure of SES, these indicators (e.g., financial,human, and social factors) should be analyzed separately. Many of thefactors often used to create a composite SES indicator are not alwayshighly interrelated (Liberatos, Link, & Kelsey, 1988), thus important re-sults can be missed by using a composite indicator. In the present study,participation in the free/reduced-cost lunch program may indicate lim-ited financial resources available to the student. Nevertheless, cautionshould be taken in interpreting the results of the present study, keepingin mind that more than one definition of poverty or low SES may bebeneficial in future research.

In the present study students' GPA was used as a measure of academicachievement. However, it is possible that other measures of achieve-ment would reveal different relationships between social support andsuch variables as SES. For example, curriculum-based measures may be

392 MALECKI AND DEMARAY

more sensitive to the day-to-day academic performance of students andmay be more influenced by students' social support.

Another limitation of the current study was the sample. The data camefrom only 28% of the students in one school. In addition to the low partic-ipation rate, the participants were predominantly Hispanic, which lim-its the generalizability of the results from this particular study. How-ever, given the levels of poverty and academic concern surroundingmany Hispanic students (Rosenthal, 2000), the results are important forunderstanding specific concerns relating to these students.

Finally, the current study's correlational findings represent only a firststep in demonstrating that social support may play a role in the relation-ship between SES and academic performance. The results, although in-triguing, do not suggest that social support is the critical factor in the re-lationship between SES and GPA, rather, that it is one potentiallyimportant factor. Further studies with experimental designs are neededto support the utility of social support interventions on academicperformance.

Conclusions

Is perceived social support related to students' academic success inschool? Results of the current study suggest that "it depends." For stu-dents experiencing economic disadvantage, social support was consis-tently related to classroom grades. For students not living in poverty, nosuch relationship was found. These findings contribute to a growingbody of literature supporting the buffering effects of social support andapply this model to students' academic performance. School psycholo-gists should consider assessing social support in students' lives and con-sider social support, especially from parents and teachers, as a target forintervention, particularly for students of low SES.

ReferencesAiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions.

Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). Moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psy-

chological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations, Journal ofPersonality and Social Psychology, 51,1173-1182.

Battle, J. (2002). Longitudinal analysis of academic achievement among a nationwide sam-ple of Hispanic students in one-versus dual-parent households. Hispanic Journal ofBehavioral Sciences, 24,430^47.

Becker, B. E., & Luthar, S. S. (2002). Social-emotional factors affecting achievement out-comes among disadvantaged students: Closing the achievement gap. EducationalPsychologist, 37,197-214.

SOCIAL SUPPORT AS A BUFFER 393

Caldas, S. J., & Bankston, C. L., III. (1997). Effect of school population socioeconomic statuson individual academic achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 90,269-277.

Cauce, A. M., Felner, R. D., & Primavera, J. (1982). Social support in high-risk adolescents:Structural components and adaptive impact. American Journal of Community Psy-chology, 10,417-428.

Clearinghouse on Urban Education. (2001). Latinos in school: Some facts and findings.ERIC Digest, 162,1-5.

Cohen, S., Gottlieb, B. H., & Underwood, L. G. (2000). Social relationships and health: Chal-lenges for measurement and intervention. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine, 17,129-141.

Demaray, M. K., & Malecki, C. K. (2002). Critical levels of perceived social support associ-ated with student adjustment. School Psychology Quarterly, 17,213-241.

Demaray, M. K., & Malecki C. K. (2003). Perceptions of the frequency and importance of so-cial support by students classified as bullies, victims, and bully/victims in an urbanmiddle school. School Psychology Review, 32,471^89.

Dubow, E. F. & Tisak, J. (1989). The relation between stressful life events and adjustment inelementary school children: The role of social support and social problem-solvingskills. Child Development, 60,1412-1423.

Educational Resource Information Center (1999). A nation still at risk (ERIC Digest). Clear-inghouse on Assessment and Evaluation, College Park, MD. (ERIC Document Re-production Service No. ED 429 998).

Elliott, S.N., Malecki, C.K., & Demaray, M.K. (2001). New directions in social skills assess-ment and intervention for elementary and middle school students. Exceptionality, 9,19-32.

Ensminger, M. E., Forrest, C. B., Riley, A. W., Kang, M., Green, B. F., Starfield, B. et al.(2000). The validity of measures of socioeconomic status of adolescents. Journal ofAdolescent Research, 15,392^19.

Entwisle, D. R., & Astone, N. M. (1994). Some practical guidelines for measuring youth'srace /ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Child Development, 65,1521-1540.

Frey, C. U., & Rothlisberger, C. (1996). Social support in healthy adolescents. Journal ofYouth and Adolescence, 25,17-31.

Garmezy, N., Masten, A., & Tellegen, A. (1984). The study of stress and competence in chil-dren: A building block for developmental psychopathology. Child Development, 55,97-111.

Gillock, K. L., & Reyes, O. (1999). Stress, support, and academic performance of urban, lowincome, Mexican-American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28,259-282.

Harter, S. (1985). Manual for the Social Support Scale for Children. Denver: University of Den-ver.

Hauser, R. M. (1994). Measuring socioeconomic status in studies of child development.Child Development, 64,149-169.

Hecht, S. A., & Greenfield, D. B. (2001). Comparing the predictive validity of first gradeteacher ratings and reading-related tests on third grade levels of reading skills inyoung children exposed to poverty. School Psychology Review, 30,50-69.

Jackson, Y., & Warren, J. S. (2000). Appraisal, social support, and life events: Predicting out-come behavior in school-age children. Child Development, 71,1441-1457.

Levitt, M. J., Guacci-Franco, N., & Levitt, J. L. (1994). Social support and achievement inchildhood and early adolescence: A multicultural study. Journal of Applied Develop-mental Psychology, 15,207-222.

394 MALECKI AND DEMARAY

Liberates, P., Link, B. G., & Kelsey, J. L. (1988). The measurement of social class in epidemi-ology. Epidemiologic Reviews, 10,87-121.

Licitra-Kleckler, D. M., & Waas, G. A. (1993). Perceived social support among high-stressadolescents: The role of peers and family. Journal of Adolescent Research, 8,381-402.

Lifrak, P. D., McKay, J. R., Rostain, A., Alterman, A., & O'Brien, C. P. (1997). Relationship ofperceived competencies, perceived social support, and gender to substance abusein young adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry,36, 933-940.

Luthar, S. S. (1991). Vulnerability and resilience: A study of high-risk adolescents. ChildDevelopment, 62,600-616.

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evalua-tion and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71,543-562.

Ma, X. (2000). Socioeconomic gaps in academic achievement within schools: Are they con-sistent across subject areas? Educational Research and Evaluation, 6,337-355.

Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2002). Measuring perceived social support: Develop-ment of the Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale. Psychology in the Schools, 39,1-18.

Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2003). What type of support do they need? Investigatingstudent adjustment as related to emotional, informational, appraisal, and instru-mental support. School Psychology Quarterly, 18,231-252.

Malecki, C. K., Demaray, M. K., & Elliott, S. N. (2000). The Child and Adolescent Social SupportScale. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University.

Malecki, C. K., Demaray, M. K., Elliott, S. N., & Nolten, P. W. (1999). The Child and AdolescentSocial Support Scale. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University.

Malecki, C. K., & Elliott, S. N. (1999). Adolescents' ratings of perceived social support andits importance: Validation of the Student Social Support Scale. Psychology in theSchools, 36,473^83.

Mechanic, D. (1989). Socioeconomic status and health: An examination of underlying pro-cesses. In J. P. Bunker, D. S. Gomber, & B. S. Kehrer (Eds.), Pathways to health: The roleof social factors (pp. 9-26). Menlo Park, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Mickelson, R. (1990). The attitude-achievement paradox among Black adolescents. Sociol-ogy of Education, 63,44-61.

Natriello, G., McDill, E. L., & Pallas, A. M. (1990). Schooling disadvantaged children: Racingagainst catastrophe. New York: Teachers College Press (Columbia University).

Okpala, C. O., Okpala, A. O., & Smith, F. E. (1995). Parental involvement, instructional ex-penditures, family socioeconomic attributes, and student achievement. Journal ofEducational Research, 95,110-115.

Okpala, C. O., Smith, F., Jones, E., & Ellis, R. (2000). A clear link between school and teachercharacteristics, student demographics, and student achievement. Education, 120,487-494.

Pianta, R. C, & Walsh, D. J. (1998). Applying the construct of resilience in schools: Cautionsfrom a developmental systems perspective. School Psychology Review, 27,407-417.

Piko, B. (2000). Perceived social support from parents and peers: Which is the stronger pre-dictor of adolescent substance use? Substance Use & Misuse, 35,617-631.

Rank, M. R., & Hirschl, T. A. (1999). The economic risk of childhood in America: Estimatingthe probability of poverty across the formative years. Journal of Marriage and the Fam-ily, 61,1058-1067.

Rosenfeld, L. B., Richman, J. M., & Bowen, G. L. (2000). Social support networks and schooloutcomes: The centrality of the teacher. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 17,205-226.

SOCIAL SUPPORT AS A BUFFER 395

Rosenthal, I. (2000). White House strategy session on Hispanic student achievement. Tech-nology & Learning, 21,18.

Schraedley, P. K., Gotlib, I. H., & Hayward, C. (1999). Gender differences in correlates ofdepressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 25,98-108.

Tardy, C. H. (1985). Social support measurement. American Journal of Community Psychol-ogy, 13,187-202.

Uchino, B., Cacioppo,J., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. (1996). The relationship between social sup-port and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mecha-nisms and implications for health. Psychological Bulletin, 119(3), 488-531.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2002). Current population survey. Internet release date: May 28,2003.Retrieved December 9, 2003, from www.census.gov/popula-tion/socdemo/race/api/ppl-l 63/tabl6.pdf.

White, K. S., Bruce, S. E., Farrell, A. D., & Kliewer, W. (1998). Impact of exposure to commu-nity violence on anxiety: A longitudinal study of family social support as a protec-tive factor for urban children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 7,187-203.

Action Editor:

Christine Malecki, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor in the Departmentof Psychology at Northern Illinois University and is Director of Under-graduate Studies of her department. Her research interests include so-cial support, curriculum-based measurement, and applications of theproblem-solving model. Dr. Malecki received her Ph.D. from theUniversity of Wisconsin-Madison.

Michelle Demaray, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor in the Departmentof Psychology at Northern Illinois University and is the Director of theSchool Psychology program. Her research interests include social sup-port and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Dr. Demaray re-ceived her Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.