Social Participation in Conservation Efforts: A Case Study of a Biosphere Reserve on Private Lands...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

7 -

download

0

Transcript of Social Participation in Conservation Efforts: A Case Study of a Biosphere Reserve on Private Lands...

This article was downloaded by: [University of Calgary]On: 15 February 2015, At: 09:46Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Society & Natural Resources: AnInternational JournalPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/usnr20

Social Participation in ConservationEfforts: A Case Study of a BiosphereReserve on Private Lands in MexicoAnna Pujadas a & Alicia Castillo aa Centro de Investigaciones en Ecosistemas, Universidad NacionalAutónoma de México , Morelia, Michoacán, MéxicoPublished online: 15 Dec 2006.

To cite this article: Anna Pujadas & Alicia Castillo (2007) Social Participation in Conservation Efforts:A Case Study of a Biosphere Reserve on Private Lands in Mexico, Society & Natural Resources: AnInternational Journal, 20:1, 57-72, DOI: 10.1080/08941920600981371

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08941920600981371

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Social Participation in Conservation Efforts: A CaseStudy of a Biosphere Reserve on Private Lands

in Mexico

ANNA PUJADAS AND ALICIA CASTILLO

Centro de Investigaciones en Ecosistemas, Universidad NacionalAut!oonoma de Mexico, Morelia, Michoac!aan, Mexico

Biosphere reserves protect ecosystems in a context that recognizes that humans mustbe included in conservation efforts. This article presents the case study of a biospherereserve created from the lands of a private owner and a university research station.Our main objective was to analyze the role of social participation in the design andimplementation of this reserve by examining the perspectives of different stake-holders. From the government perspective, there is a clear need to promote localparticipation in conservation. The only objectives of the institutions administeringthe reserve are conservation and scientific research inside their boundaries. Fromthe perspective of an adjacent rural settlement, the presence and objectives of thereserve are alien. This study questions whether the strict conservation goals of pri-vate landowners and the inherent limitations of academic scientific institutions areconsistent with the biosphere reserve vision of including local stakeholders.

Keywords biosphere reserves, conservation, Mexico, protected areas on privatelands, role of science, rural people’s perspectives, social participation, tropicaldry forests

Protected areas have been a main instrument of ecosystem conservation and havecontributed to stopping ecosystem degradation and to maintaining essential ecologi-cal processes. However, the main attitude underlying their management has beentheir isolation from human populations (Pretty and Pimbert 1995). The exclusionof local inhabitants, mainly through prohibiting traditional uses of naturalresources, has promoted a lack of livelihood security for people living within or

Received 24 May 2005; accetped 12 February 2006.This study received financial support from the Lucille and David Packard Foundation

through the project Capacity Building in Conservation and Restoration Ecology in Mexicocoordinated by Dr. Jose Sarukh!aan. We are most grateful to the people of San Mateo, the Cha-mela Biological Station of UNAM, and the Cuixmala Ecological Foundation. We thankHeberto Ferreira and Georgina Garcia for technical support, Julia Carabias and Luisa Parefor valuable comments, Laura Hoffman for English editing, and the anonymous reviewersfor their good observations and suggestions.

Address correspondence to Anna Pujadas, Centro de Investigaciones en Ecosistemas,Universidad Nacional Aut!oonoma de Mexico, Apartado Postal 27–3, Morelia, Michoac!aan58190, Mexico. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]

Society and Natural Resources, 20:57–72Copyright # 2007 Taylor & Francis Group, LLCISSN: 0894-1920 print=1521-0723 onlineDOI: 10.1080/08941920600981371

57

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

adjacent to protected areas, which ultimately undermines conservation objectives(Ghimire and Pimbert 1997; Nygren 2004). The need to acknowledge local people’srights to meet their socioeconomic and cultural needs and the acceptance that con-servation programs should have the dual objective of protecting ecosystems andimproving people’s well-being have been strongly advocated, particularly in develop-ing countries (Wells and Brandon 1993; Peters 1999). At present, nevertheless, callsfor strong protection measures in protected areas have reappeared, questioning theidea of pursuing social goals in conservation efforts, provoking the resurgence of adebate (Wilshusen et al. 2002; Kellert et al. 2000).

Biosphere reserves are a special category of protected areas, created to integrateecosystem conservation with social development, through the participation of localpeople in conservation efforts (Batisse 1982; Halffter 1995; Bridgewater 2002;UNESCO 2006). Biosphere reserves are expected to promote the interaction betweenstakeholders in order to strengthen their co-responsibility and commitment to con-structing sustainable development at regional scales. These reserves, however, havenot been exempt from conflicts. Multiple and frequently opposing perspectivesregarding ecosystems and human involvement in ecosystems have been known tocreate conflicts between reserve administrators and local inhabitants (Sundberg1999). These conflicts are not only over the use of certain resources but also cognitivein nature. Often, the conflicts are over differences in knowledge and understandingabout laws and institutions, ideas or beliefs, or about the empirical context fromwhich knowledge about resources are obtained. Both types of conflicts can seriouslyaffect the possibilities of collaboration and participation of people in conservationefforts (Adams et al. 2003). How conservation is conceptualized and how its practiceis viewed and lived by different stakeholders involved in protected areas should besystematized and understood in order to plan and implement better strategies thatpromote long-term conservation and sustainable development.

In Mexico, the first biosphere reserves (La Michilıa and Mapimı BiosphereReserves) were decreed in the mid-1970s with the explicit objective of promotinglocal participation in conservation (Reyes 1991; Kaus 1993). A relevant feature ofthese reserves was that their management was entrusted to research institutionswhose scientists were expected to study and apply research findings to managementproblems (Halffter 1984; Pe~nna et al. 1998). This ‘‘Mexican model’’ of biospherereserves, as it was referred to internationally, particularly under the Man and theBiosphere Program of UNESCO, supported the creation of reserves in relation toscientific institutions, and local participation in management was given a highpriority. At present, there are 34 biosphere reserves in Mexico covering more than10 million hectares (CONANP 2005). In most of them, local participation is consid-ered low or nonexistent, and scientific research may be absent. However, this type ofprotected area is acknowledged to be a very important instrument of biodiversityconservation and a model under continuous experimentation (G!oomez-Pompa1998; Pe~nna et al. 1998).

Most lands in protected areas in Mexico are not state owned. There is a mosaicof tenancy that includes private lands owned by individuals or nongovernmentalorganizations (NGOs) and communal properties managed by indigenous or pea-sants’ communities. According to information provided by CONANP (NationalCommission of Protected Areas), most lands in the National System of ProtectedAreas belong to ejidos, one of the two types of communal land tenure in the country(Gutierrez, personal communication). Protected areas on private lands that belong

58 A. Pujadas and A. Castillo

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

to individuals, NGOs, or commercial entities are not common. Nevertheless, theacquisition of lands and the development of legal tools and incentives to protectthese types of private lands have been promoted in Mexico and in other countriesin Latin America (Swift et al. 2003). At present, federal environmental law allowsproperty owners to designate their lands for conservation. One of the few reservesin Mexico in which most of the lands are owned by an NGO is the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve, the case study examined in this paper.

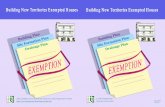

On the Pacific coast of Mexico, between the ports of Manzanillo and PuertoVallarta (see Figure 1), the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve was decreed in1993 (DOF 1994) in order to protect an area of 13,142 hectares mainly covered bytropical dry forests (Ceballos et al. 1999). Tropical dry forests make up more than60% of the tropical vegetation in the country and are considered severely threatened(Trejo and Dirzo 2000). In 1971, the National Autonomous University of Mexico(UNAM) established the Chamela Biological Station with the aim of protectingand studying an area of over 3,000 hectares (Sarukh!aan et al. 1979). In 1988, a Britishprivate owner (Sir James Goldsmith) designated a portion of his lands for conserva-tion and created the NGO Cuixmala Ecological Foundation for administering thesite. According to the reserve’s management plan (Ceballos et al. 1999) these landsnow belong to the NGO. The reserve is part of the National System of Natural Pro-tected Areas. In 1996 the federal government accepted that the National Universityand the NGO should administer the reserve. Although no human communities arefound within the reserve’s boundaries, it is surrounded by ejidos.

Apart from securing the long-term protection of remaining natural ecosystems,the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve has as its central aims to conduct basic

Figure 1. Location of the Chamela-Cuixmala region on the Pacific coast of Mexico.

Social Participation in a Biosphere Reserve 59

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

and applied scientific research and to carry out educational activities that promote thesustainable use of natural resources in the adjacent human communities (Ceballoset al. 1999). To disseminate an environmental awareness and to establish a dialoguewith local people to negotiate and agree on new forms of appropriating ecosystem ser-vices in this region should be at the center of interest for the institutions administeringthe reserve, to include social participation in the management of this protected area(Castillo 2001; Paz 2005). In this context, our study examines how the participationof local people is understood and how people’s participation has been considered inthe process of designing and implementing the biosphere reserve. The analysis consid-ers the perspective portrayed in the written documents that regulate the managementof the reserve, as well as the points of view of the institutions responsible for thereserve’s management and that of inhabitants of an ejido adjacent to the reserve.The main research questions include: How are the concepts of conservation and bio-sphere reserves understood, in particular regarding the Chamela-Cuixmala BiosphereReserve? How was social participation understood and considered during the processof designing and implementing the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve? Is there aninteraction between the reserve and the local population through which a jointconservation responsibility is constructed?

The Social Context of the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve

Despite its beauty, ecological relevance, and tourism potential, the Chamela-Cuixmala region was long ignored by governmental authorities (INE 2001). Exceptfor a few isolated communities established since the mid-19 century, it wasn’t untilthe 1950s that governmental policies aimed at colonizing the Mexican coasts andproviding tenure security for small private owners enhanced the establishment ofhuman settlements in the area (Ortega 1995). Most rural people came to the regionfrom different Mexican States between 1950 and 1970 as part of land-distributionprograms and formed ejidos (Castillo et al. 2005a). Ejidos in the Chamela-Cuixmalaregion range from 2000 to more than 17,000 ha (a larger area than the reserve) andthey cover more than 70% of the municipality of La Huerta where the reserve islocated (INEGI 2000). This communal land tenure system, although rooted in indi-genous precolonial forms of land tenure, was developed from the Agrarian Reformthat resulted from the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1917. Ejidos are a primarymechanism allowing local people to have access to land. Ejidos also allow localpeople the capacity to allocate and enforce rights to resources (Warman 2001).

In the region surrounding the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve there areabout 50 settlements with a population of about 10,000 people (INEGI 2001). Theserural settlements are socioeconomically characterized by a low level of well-being, highlevels of illiteracy, high migration rates, and unequal access to services such as healthand education (SEMADES 1999; INE 2000). Very few employment opportunitiesexist; the main source of income is activities related to cattle raising and agriculture(INEGI 2001). The development of ejidos has been identified as an important driverof ecosystem deterioration due to ecosystem transformation into agricultural and pas-ture lands. Conversion of forests into pasture involves vegetation removal, burning ofplant material to release nutrients into the soil, and cultivating maize, beans orsorghum. After a few years, as productivity declines as a result of soil degradation,nonnative grasses are introduced for cattle pasture. The nonnative grasses may lastmany years, depending on management practices (Maass 1995; Maass et al. 2002).

60 A. Pujadas and A. Castillo

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

Despite the large body of biological and ecological knowledge (around 400scientific articles and 170 theses; Instituto de Biologıa 2006) that has been generatedon the site, very little has been studied about the social dimensions of ecologicalchange. It has only been in the last 5 years that topics such as environmental history,local people’s perceptions of forest use, degradation, and conservation, and theiropinions of the biological station, the NGO, and the biosphere reserve have been stu-died (Castillo et al. 2005a). These studies have identified the agricultural develop-ment model promoted by government for decades as the main driver of ecosystemtransformation. This is a different view from the model that directly blamed ejidatar-ios as responsible for deforestation. These results have also shown that peasant peo-ple are proud of the pasture lands that have replaced native forests. They believe thatthe lands were given to them by the government in order to make them productive.The conservation policies implemented during the last two decades, on the otherhand, are viewed by local people as impositions. Through these policies, people thinkthey will be forced to stop using their lands, thus directly affecting their family liveli-hoods. Nevertheless, people gave value to services provided by ecosystems, forinstance, water supply, food provision, soil fertility maintenance, aesthetic apprecia-tion, and the enjoyment of shade from trees (Castillo et al. 2005a).

Methodology and Methods of Research

In order to understand social participation in the processes of the design and imple-mentation of the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve, a qualitative researchapproach was chosen, because the goal was to analyze the social phenomena in termsof the meaning that actors give to it (Denzin and Lincoln 2000). Research methodssuch as semistructured interviews and participant observation were used (Taylor andBogdan 1987; Robson 1993).

Initial interviews were conducted with regional key informants to get anapproximation for the problem and to meet different local actors. These informantsincluded biologists that have worked in the region for more than 10 years and hadexperience in the administration of the reserve and also some ejidatarios who wereidentified by local people as leaders among the rural communities. To understandthe institutional perspective about social participation in the establishment and man-agement of the reserve, 20 official documents were reviewed (8 international, 9national, and 3 related to the reserve under study) in relation to the laws and formalagreements that govern the management of protected areas in the country (specifi-cally biosphere reserves) and the particular case of the Chamela-Cuixmala BiosphereReserve. To examine the perspective of the reserve, access was obtained to interviewthe director of the biological station and two people at the NGO responsible forresearch programs and managing the reserve (one of them is considered the spokes-man for the reserve’s private owners who do not live in the area permanently). Toanalyze the perspective of the local rural community, the population of the ejidoSan Mateo was selected. This ejido is adjacent to the reserve, sharing an extendedboundary with the station and the reserve. Ejido San Mateo is also an importantadministrative center for the municipality and is recognized by the region’s inhabi-tants to be an exemplary community for the other ejidos surrounding the reserve.Agricultural and cattle raising activities of San Mateo are carried out under the samemanagement pattern as the rest of the ejidos surrounding the reserve (Maass 1995).In an initial phase, three local authorities of San Mateo were interviewed. Using the

Social Participation in a Biosphere Reserve 61

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

information obtained from those interviews, we designed a detailed and concreteinterview format and administered it to 13 randomly selected members of the ejido.These 13 people represented almost half of the total number of present ejidatarios.

All the interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed into a word processor(interviews could last 3 hours and transcripts could be 60 pages long). Analysiswas carried out using the Atlas.ti program version 4.2 for qualitative analysis (SSDB1997). Through a line-by-line revision of transcripts, categories were created fromthe data with the aim of producing concepts that fit the data. Categories were linkedand intertwined in order to construct interpretive texts around the themes understudy. Observations collected in the field from informal talks and the everyday coha-bitation with the different actors were used to contextualize, complement, and verifythe information collected in the interviews.

Data obtained through the interviews with members of the ejido San Mateo werealso used to quantify specific answers to the topics we addressed with the intervie-wees in order to summarize results. This method is in accordance with the qualitativeapproach, since the instrument was designed to search for people’s own perspectives(Denzin and Lincoln 2000).

Study Findings: The Diversity of Perspectives Regarding SocialParticipation in Conservation

The Formal Institutional Perspective

In the legal and normative framework of protected areas in Mexico, ecosystem con-servation is understood as those policies aimed at enhancing the maintenance of eco-systems in the country (DOF 1996). Protected areas aim to preserve representativehabitats in order to ensure their evolution and functioning and the continuousappropriation of natural resources by human societies (DOF 1996; 2000). The inte-gration between ecological and social objectives is emphasized in biosphere reserves,which are conceived of as part of regional development strategies. To achieve theseobjectives in protected areas, specifically in biosphere reserves, collaborationbetween the institutions responsible for protected areas and other stakeholders, withemphasis on local actors, is essential (DOF 1996; SEMARNAP 1996). Social parti-cipation is recognized as an element that needs to be promoted throughout the initia-tion, design, formulation, execution, monitoring, and evaluation phases of protectedarea implementation (DOF 1996; Poder Ejecutivo Federal 1996; 2001). Conse-quently, social participation is used to legitimatize conservation policies and to facil-itate the promotion of shared responsibilities and commitments among differentstakeholders (DOF 1996; Poder Ejecutivo Federal 1996).

In the particular case of the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve, and accord-ing to its decree (DOF 1994) and management plan (Ceballos et al. 1999), the reservehas as its main objectives the protection of the habitats within its boundaries anda commitment to contribute to the long-term sustainable development of theChamela-Cuixmala region. The reserve’s creation responded to a public interest,and it is acknowledged that an involvement from the local population to participatein conservation is required. The decree established that a consultation process withadjacent communities should have been conducted prior to the creation of thereserve (DOF 1994) and that the views of local actors should have been obtainedfor the elaboration of the management plan. The management plan stipulates that

62 A. Pujadas and A. Castillo

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

the reserve’s governing structure must have sufficient representation from the differ-ent stakeholders (Ceballos et al. 1999). In 1996, the management of the reserve wasassigned to the Chamela Biological Station and the Cuixmala Ecological Foundationthrough an agreement with the federal government in which the government kept asupervising role (INE 1996). In addition, the decree and the management plan statethat the reserve is obliged to collaborate with the local populations in order topromote sustainable development. Scientific research in the reserve was also acknowl-edged to be directed toward the construction of sustainable ecosystem managementstrategies that could also improve local people’s well-being. Understanding the socialcontext of the region and of working to disseminate information, technical assistance,and environmental education were also recognized as relevant aspects.

The Perspective of the Institutions Responsible for the Biosphere Reserve: TheChamela Biological Station and the Cuixmala Ecological Foundation

For the station and the foundation, the concept of conservation derives from the bio-logical sciences; it is understood as the maintenance of ecosystem processes andimplies the protection of areas from human disturbances. The reserve is defined asa delimited area dedicated to conservation and scientific research and is not opento outsiders. The reserve is also understood as the sum of the lands owned by thestation and those owned by the foundation. Both institutions acknowledged thatalthough they jointly manage the reserve and recognize a need to coordinate activ-ities, they are independent entities. Both institutions recognized that their interac-tions are sometimes difficult.

From the point of view of the station, the concept of social participation meansthat local people should have a commitment to conservation principles. This com-mitment is understood as the result of an effort that the two institutions involvedin the reserve’s management should accomplish through a transfer of useful informa-tion ‘‘to change people’s natural resource management systems’’ and for raisingenvironmental awareness among locals. For the foundation, social participation isthe necessary involvement of the local population in the reserve’s functioning onlyif the reserve increases its area and incorporates human settlements. In such a case,an environmental awareness campaign would be needed ‘‘to make them real stake-holders in the management of the protected area.’’

At present, both organizations recognize that local people and other stakeholdersare excluded from the management decision process. Government is perceived as hav-ing a limited supervisory role and the local populations are not considered as relevantactors. The major justifications are that most lands are private, no human commu-nities live inside the reserve, and the activities in the reserve do not affect them. Bothorganizations agreed that the objectives of the station are the conservation of its landand the facilitation of biological research and that the objectives of the foundation arethe protection of its lands (by not allowing the entrance of people using a high-security system involving guards and patrol vehicles) and biological research. Bothactors recognized that the foundation also has the additional objective of administra-tion of a private ranch adjacent to the reserve.

Regarding the regional impact of the reserve, interviewees from both institutionsacknowledged that although scientific research generates information that could beused to solve environmental problems, at the moment most research is academic innature. The station also recognized that as part of the National Autonomous

Social Participation in a Biosphere Reserve 63

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

University of Mexico, it has a rigid structure that makes it difficult to developactivities that link the reserve with the surrounding communities. The foundationhas a more dynamic structure with higher capabilities to act collaboratively with localpeople. However, it was also recognized by the two institutions that neither of themactually assumes this task, although they have carried out isolated environmentaleducation activities, mainly with schoolchildren. The foundation also mentioned their‘‘supportive actions which benefited communities such as the construction of bridges,football grounds and urban recreation areas.’’

The Perspective of the Ejido San Mateo

According to the information provided by key informants and a sample of the ejidopopulation (percentages given are according to this sample, n¼ 13), the concept ofconservation is understood as a decision ‘‘to leave the monte [rural term appliedto non-used vegetated lands] untouched.’’ All interviewees emphasized that this deci-sion can be made either by government or by ‘‘private owners who can have landsthey do not need to use.’’ Some people (23%) emphasized that this ‘‘luxury’’ cannotbe taken by them: ‘‘We depend directly on the use of land or how else are we going tofeed our children?’’ For them, the reserve is a ‘‘protected zone’’ located contiguous toSan Mateo ‘‘where care is taken of the monte.’’ In this case, the reserve is equivalentto the lands of either the station or the foundation. For some others (38%) thereserve is understood as all land assigned for conservation by the government:‘‘monte that nobody can touch in order to protect wildlife.’’ In this sense, it shouldbe mentioned that people consider the reserve as equivalent to the Ecological Land-Use Planning Program decreed in 1999 by the state government, which covers theChamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve and the lands of different ejidos (includingSan Mateo). Finally, some people (23%) admitted having no understanding at allof the purpose of the reserve.

In relation to the station, most people (77%) recognized that ‘‘it is a reserve orprotected lands’’ and 46% recognized that it is ‘‘a centre of the National Autono-mous University of Mexico where studies and experiments with plants and animalsare carried out.’’ Two informants stated that ‘‘unfortunately, their achievements donot benefit the country but that it could benefit the region if researchers had someinterest in applied studies.’’ In reference to the foundation, five people (38%) hadnever heard about it and the rest (62%) recognized it as ‘‘a protected land’’ and alsoas ‘‘a very extensive property where rich people live.’’ Because the family owningthese lands also has a ranch that employs about 200 people, people associate theranch with the foundation and they recognize the provision of jobs to locals. Atten-tion was also given to the richness of animal species, which is seen as ‘‘huntinggrounds for the family owners and their visiting friends.’’

From the interviews it was not possible to extract a precise concept of social par-ticipation among people of San Mateo. For them, social participation has no sense inthe conservation context. They understand that government is the one that decidesto impose conservation as a land use, or that private owners ‘‘can decide what todo in their lands without consulting anyone.’’ When asked about the existence ofa consultation process when the biosphere reserve was created, all people stated thatthey were never consulted and that ‘‘informing us would have been a nice gesture.’’When asked about possible involvement in the biosphere reserve’s management,many people (62%) argued again that ‘‘it is private; they should not ask us for

64 A. Pujadas and A. Castillo

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

permission or opinion’’ because ‘‘it is their business and it does not really affect us.’’About other possible links that they could have with scientists or administrators ofthe station and the foundation, all people agreed that until now there had been ‘‘nointerest or intention’’ from these institutions, or from them either, to develop a com-mon interest and to establish a linkage. People explained, however, that some scien-tists have hired local people for their fieldwork and that the station sometimes hadinvited schoolchildren and that through these visits, local people could develop anunderstanding of the work carried out.

Discussion: Private Participation in Conservation and the Roleof Scientific Institutions

The Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve contributes to the preservation of theextremely rich biodiversity of tropical dry forests in Mexico, particularly on the Paci-fic coast where major areas of this ecosystem are located (Noguera et al. 2002; Trejoand Dirzo 2000). The reserve has been claimed as a model of protected areas‘‘because it has solved the main problems that limit the efficiency of nature reservesincluding land tenure, financial support and social problems’’ (Ceballos and Garcıa1995, 1349). This opinion is based on the argument that the lands are privatelyowned and owners are willing to invest in conservation; therefore, conservation facesno obstacles. Our results, however, show a different panorama than that of a suc-cessful conservation experience.

Since the mid-1980s, it has been strongly advocated that people should be con-sidered as part of biosphere reserves (Price 2002) and that the scale of influence ofsuch reserves should be regional through consideration of ‘‘outer transition areas’’(UNESCO 2006). The perspective presented in government documents recognizesthe need to develop strong links with the human communities surrounding theChamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve and to support the development of sustain-able forms of managing ecosystems. However, the way in which the reserve is man-aged indicates that it still functions with a 1970s vision of only protecting the areaand conducting ecological research. The social development objectives establishedsince the reserve’s creation have not yet been satisfactorily fulfilled. Three mainaspects may explain this situation: (1) the private character of the reserve, (2) thereluctance of the scientific community to accept the challenge of establishing contin-uous and interactive linkages with local stakeholders, and (3) the lack of close super-vision from the federal agency responsible for protected areas.

In Latin America, the establishment of protected areas on private lands has beenseen as an opportunity to enlarge the national systems of protected areas and as away to support conservation efforts because, frequently, governments lack financialresources or the political will to support these actions. The Fifth World Park Con-gress recognized that more incentives should be offered to create protected areas onprivate lands and that legal and technical support should be provided for them.Emphasis was given to the need to promote cooperation between private ownersof reserves and other social actors. Enhancing and improving the exchange of tech-nology, knowledge, and experiences between owners and local stakeholders wasidentified as crucial (Langholz and Krug 2003). In Mexico, environmental law wasmodified in 1996 to allow private groups, particularly landowners, to participatein the maintenance, protection, and administration of protected areas. Fiscal incen-tives were provided to promote this new protected area policy, taking advantage of

Social Participation in a Biosphere Reserve 65

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

having public and private support (Arrieta n.d.; INE 1995). In this way the NationalSystem of Protected Areas in the country can benefit from private support and itlooks meritorious that private landowners voluntarily set aside lands to be protectedand agree to manage them in order to secure their long-term conservation.

The creation of the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve responded to theinterest of some conservation biologists who in the 1980s strongly advocated thenecessity of conserving a larger area of tropical dry forest than was encompassedby the Chamela Biological Station. These biologists were successful in convincinga private landowner to protect his property through the creation of a reserve. Unlikemost environmental NGOs in Mexico, the Cuixmala Ecological Foundation worksto protect private lands. Currently, not only are outsiders excluded from the reserve,but recently the foundation has denied permission to some researchers to conductscientific studies. The Chamela Biological Station, on the other hand, controls theaccess to the university lands and premises, and it allows the visit of school groupsas part of its educational role. Because the National University is public, the use ofits premises clearly responds to its scientific and educational objectives. What wasraised in our results, nevertheless, was that the surrounding human communitiesobtained no benefits from the University’s presence apart from a few jobs for localpeople at the research station. For both the foundation and the station, the fact thatthere are no human settlements within the reserve’s boundaries is used as a strongargument for not considering the participation of locals in the reserve’s design andimplementation, and also for not taking action to establish linkages with localcommunities. The fact that most of the lands are privately owned is also used asan argument by the foundation. They admit that the local people who live aroundthe reserve should be considered, but only in terms of alerting them to the impor-tance of managing their lands in more sustainable ways. At present, the foundationdoes not provide any advice to facilitate the transformation of people’s managementpractices. The foundation has expressed that educational activities should be con-ducted, but it do not yet have an educational program; it only conducts isolatedactivities.

As discussed by Wilshusen et al. (2002), the line of reasoning that combines‘‘pragmatic’’ (strict systems of protection) and ‘‘moral arguments’’ (ecosystemsand biodiversity protection for their own sakes) is a common rationale among con-servationists. Not paying attention to people’s understandings of natural systemsand to their own interests and needs tends to create a false dilemma in which therights of humans are pitted against the rights of nature. This conception, whichexpresses no consideration for the views of local people, shows how the institutionsresponsible for the management of the reserve present themselves as detached fromthe existing economic and power differences among all local stakeholders (Sundberg1999). Furthermore, the foundation claimed to support local social developmentthrough ‘‘actions such as the construction of bridges or football grounds’’ andthrough its ‘‘major presence at the regional level’’ participating in municipalityand state meetings, and ‘‘disseminating environmental conservation ideas.’’ Thiskind of paternalistic relationship, although sometimes useful for solving emergentproblems, ignores the capability of the local people to identify their own needsand to formulate and implement their own development strategies. Consequently,it does not represent any incentive for people and can become a factor of economicand technological dependence and can inhibit social participation in conservationefforts (Guerra 1997).

66 A. Pujadas and A. Castillo

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

As a consequence, local people see no reason to be involved in the reserve’smanagement or in the protection effort because ‘‘the lands in the reserve have privateowners.’’ For local people, decisions to conserve or ‘‘not use’’ a piece of land shouldbe made by the local owners of those lands and should not be imposed on them. Theyare clear that land conservation is a decision that only concerns owners, and perceiveno purpose in contributing to the decisions of others. This notion that the people ofSan Mateo have that private owners are free to decide what to do on their land also isconnected with the idea that people owning the protected area ‘‘are wealthy,’’ thatthey can buy lands and can have the ‘‘luxury’’ to designate them for conservation.The argument for conservation in the public interest appears to be lacking in localpeople or not completely understood. Consequently, people easily accept not beinginvolved in the decisions regarding the reserve. As rural producers, they act to max-imize short-term gains and perceive their interests as tangible and immediate, whilethe idea of conservation is unclear and intangible (Haenn 1999). The issue of disinter-ested local people ‘‘participating’’ in the conservation effort also has an explanationresulting from the way in which participation interventions have evolved in LatinAmerica and Mexico. On the one hand, since the 1970s participation has been a topicstrongly associated with the ideas of Paulo Freire, for whom participation was relatedto the raising of consciousness among poor people and to their need for emancipationin order to transform their own realities (Freire 1973). Experiences throughout thecontinent, particularly in the context of NGOs, have been based on the recognitionof people’s capacity to process social experiences, to reflect, and to act accordingly.Participation in development projects and policy formulation, on the other hand,has been different. People, particularly in poor and rural areas, have been consideredas passive actors and their participation has been conceived as a final step where theyonly conduct what has been decided by others (Reyes 1997). From projects financedby international agencies such as the World Bank to many governmental programs,this form of top-down development in Mexico has been widely used (Paz 2005). Con-servation interventions such as the implementation of protected areas have inheritedthis latter form of development, and our results show how the Chamela-CuixmalaBiosphere Reserve was created using this logic. At present, the conception of thescientists and reserve administrators regarding social participation in conservationreflects this kind of thinking, where people are considered as empty recipients whoshould be filled with conservation ideas so that they stop destroying ecosystemsand advocate the conservation cause.

The second issue to discuss concerns the role of academic research. As a result ofmore than 30 years of scientific investigations carried out in the biological stationand the biosphere reserve, the Chamela-Cuixmala site is one of the best studied siteswithin the Neotropics (Noguera et al. 2002). This large body of knowledge not onlyhas contributed to our understanding of the biology and ecology of tropical dry for-ests, but also has played an important role in the formulation of conservation poli-cies in the country. At the local level, almost no contribution has been offeredregarding the construction of alternative forms of appropriating ecosystems thatat the same time secure their long-term maintenance and give access to rural inhabi-tants for more sustainable and dignified livelihoods.

The way in which the scientific activity is organized at UNAM does not facilitateor support the establishment of linkages between scientists and their work and theneeds or demands of social sectors such as rural producers (Castillo et al. 2005b). Asan academic institution, the National University is immersed in a current scientific

Social Participation in a Biosphere Reserve 67

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

ethos that praises the role of the individual scientist and his or her own capacity togenerate knowledge (Fortes and Lomnitz 1991). What the system favors is the pub-lication of as many papers as possible in international journals, and it gives low valueto collaboration with nonscientific sectors. The result is that scientists who study thenever-ending and fascinating details of ecosystems like tropical dry forests get incen-tives and recognition, whereas scientists conducting applied research and workingwith different social sectors do not. In relation to environmental problems, othermodels have been proposed that emphasize the role of science as a tool to solveproblems defined by clients (in contrast to finding solutions to problems definedby the curiosity of the single investigator or his or her idea of practical problems).Consequently, a group involved in constructing solutions and alternative paths isformed not only by scientists but includes different stakeholders. ‘‘Extended peercommunities’’ and acceptance of other types of knowledge (not only scientific) aretherefore needed when the interest is the continuous construction of sustainablesocieties (Funtowicz and Ravetz 1991). In this sense, the conflicts between the stationand the foundation negatively affect the possibility of constructing a common strat-egy that strengthens the connection with local stakeholders. Unless there is a coor-dinated effort, the distance between the research conducted and the realities lived inthe Chamela-Cuixmala region will continue to grow. The types of scientific researchcarried out must be broadened and more interdisciplinary approaches should beconsidered. It is essential to increase the number of studies that help explain ruralproducers’ land-use decisions and that uncover their needs and expectations in orderto improve the ways in which conservation and other environmental interventionsare implemented.

Finally, the lack of close supervision by CONANP, the federal agency responsi-ble for protected areas, over the work of the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserveis another relevant factor allowing the reserve to fulfill its mission regarding conser-vation and ecological research while ignoring its stated social responsibilities. Theagreement through which the responsibility to administer the reserve was trans-mitted from the government clearly specifies the need to promote the participationof society in conservation actions. It should be noted, however, that from the per-spective of the federal government, the mere transmission of responsibilities througha signed agreement constitutes a form of social participation in conservation (INE1995). Consequently, the station and the foundation have complete autonomy notonly to take decisions, but to construct and justify the lack of inclusion of localpopulations in matters of interest to the reserve. This understanding seems to relieveCONANP not only from financing the reserve’s management, but also from securingthe fulfillment of any other responsibilities (Sundberg 1999). If this reserve has realpublic value for government, CONANP should play a more active role (Guerra1997). As pointed out by Price (2002), countries should have monitoring systems thatsystematically review biosphere reserves to determine if they are up-to-date with theevolving concept of local participation. This is particularly important in countriessuch as Mexico, which are biologically mega-diverse and which have large popula-tions of locals whose livelihoods directly depend on biodiversity.

Recommendations

The present study has shown that the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve activ-ities do not coincide with what its creators initially intended or what is stipulated

68 A. Pujadas and A. Castillo

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

in official documents and scientific publications. Although the reserve is claimed tobe a success in the protection of the area within its boundaries, in the wider socialand cultural context this statement masks the other political roles played by thereserve and by the institutions behind it.

To change the way in which the reserve is managed, a reversal is needed in thecurrent management approach (Chambers 1993). A radical change in the behaviorand attitudes of the institutions responsible for the reserve is required in order to pro-mote the conservation, sustainable use, and restoration of ecosystems at the regionalscale. Instead of a strict protection scheme, it is important to share with local stake-holders the knowledge scientists have discovered about the ecosystems and the ser-vices they provide to humans. A clear separation of the private landowner’sinterests from the work conducted in the reserve is fundamental for building trustbetween the reserve and local people. A real commitment from scientists to partici-pate with stakeholders in the construction of alternative ways of managing landsand natural resources is necessary. It is extremely important to acknowledge ejidosas relevant local institutions and to work with them in the construction of strategiesthat promote the conservation of the remaining vegetated area, the sustainable use ofnatural resources and other ecosystem services, and the restoration of degraded lands.

If social participation is incorporated as part of the reserve’s managementapproach, both the reserve and local inhabitants will have much to gain. To promotethe interest of local people in conservation (understood not only as the protection ofthe reserve lands but also as the incorporation of a vision of sustainability in thepractices of local people and their institutions), the reserve should listen to the opi-nions of local inhabitants. Through participatory approaches, the reserve shouldidentify and acknowledge the interests, needs, and world visions of the different sta-keholders. Local people should start recognizing the presence of the reserve not as anunrelated entity, but as something connected to their daily lives. They could thenconsider new ideas and acquire useful information (particularly regarding the useof lands and the management of natural resources). At the core of including partici-pation as part of the reserve’s management would be constructing a common regio-nal project, maintaining life-sustaining processes, and improving local people’slivelihoods. True social participation in the conservation effort at the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve will use the valuable capital of local people to constructa regional experience that truly contributes to the maintenance of Mexican tropicaldry forests, and to the sustainable development of the human communities that arepart of it.

References

Adams, W., M. D. Brockington, J. Dyson, and B. Vira. 2003. Managing tragedies: Under-standing conflict over common pool resources. Science 302:1915–1916.

Arrieta, G. n.d. Situaci!oon legal y oportunidades de inversi!oon en las !aareas naturales protegidasde Mexico. Revista Cespedes 2(9). http://www.cce.org.mx/cespedes (accessed May 3,2005).

Batisse, M. 1982. The biosphere reserve: A tool for environmental conservation and manage-ment. Environ. Conserv. 9(2):101–111.

Bridgewater, P. B. 2002. Biosphere reserves: Special places for people and nature. Environ. Sci.Policy 5(1):9–12.

Castillo, A. 2001. Comunicaci!oon para el manejo de ecosistemas. T!oopi. Educ. Ambiental3:41–54

Social Participation in a Biosphere Reserve 69

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

Castillo, A., M. A. Maga~nna, A. Pujadas, L. Martınez, and C. Godınez. 2005a. Understandingrural people interaction with ecosystems: A case study in a tropical dry forest of Mexico.Ecosystems 8:630–643.

Castillo, A., A. Torres, G. Bocco, and A. Vel!aasquez. 2005b. The use of ecological science byrural producers: A case study in mexico. Ecol. Applications 15(2):745–756.

Ceballos, G. and A. Garcıa. 1995. Conservating neotropical biodiversity: The role of dry for-ests in western Mexico. Conserv. Biol. 9(6):1349–1356.

Ceballos, G., A. Szekely, A. Garcıa, P. Rodrıguez, and F. Noguera. 1999. Programa de manejode la Reserva de la Biosfera Chamela-Cuixmala. Mexico, DF, Mexico: Instituto Nacionalde Ecologıa, Secretarıa de Medio Ambiente, Recursos Naturales y Pesca.

Comisi!oon Nacional de Areas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP). 2005. ¿Que son las ANP?http://www.conanp.gob.mx/anp (accessed August 5, 2005).

Chambers, R. 1993. Reversals, institutions and change. In Farmer first. Farmer innovation andagricultural research, eds. R. Chambers, A. Pacey, and L. A. Thrupp, 181–195. London:Intermediate Technology Publications.

Denzin, N. K. and S. Lincoln, (Eds). 2000. Handbook of qualitative research, 2nd ed.Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Diario Oficial de la Federaci!oon, 1994. Decreto por el que se declara !aarea natural protegida concar!aacter de reserva de la biosfera, la regi!oon conocida como Chamela-Cuixmala, ubicadaen el municipio de La Huerta, Jal. Gac. Ecol. 6:56–64.

Diario Official de la Federaci!oon. 1996. Ley General de Equilibrio Ecol!oogico y Protecci!oon alAmbiente. Mexico, DF. http//kim.ineamer.conacyt.mx/Servicios/Leyes.html (accessedApril 19, 2002).

Diario Official de la Federaci!oon, 2000. Reglamento de la Ley de Equilibrio Ecol!oogico y laProtecci!oon al Ambiente en Materia de Areas Naturales Protegidas. Mexico, DF. http://sepultura.semarnat.gob.mx (accessed April 25, 2002).

Fortes, J. and L. Lomnitz. 1991. La formaci!oon del cientıfico en Mexico. Mexico, DF, Mexico:Siglo XXI Editores.

Freire, P. 1973. Extensi!oon o comunicaci!oon? Mexico, DF, Mexico: Siglo XXI Editores.Funtowicz, S. O. and J. R. Ravetz. 1991. A new scientific methodology for global environmen-

tal issues. In Ecological economics. The science and management of sustainability, ed. R.Costanza, 137–152. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ghimire, K. B. and M. P. Pimbert. 1997. Social change and conservation. Environmental pol-itics and impacts of national parks and protected areas. London: Earthscan.

G!oomez-Pompa, A. 1998. La conservaci!oon de la biodiversidad en Mexico: Mitos y realidades.Bol. Soc. Bot!aan. Mexico 63:33–41.

Guerra, C. 1997. La participaci!oon social y las polıticas publicas: Un juego de estrategias.In Las polıticas sociales de Mexico en los a~nnos noventa, 75–110. Mexico, DF, Mexico:Instituto de Investigaciones Dr. Jose Maria Luis Mora.

Haenn, N. 1999. The power of environmental knowledge: Ethnoecology and environmentalconflicts in Mexican conservation. Hum. Ecol. 27(3):477–491.

Halffter, G. 1984. Las reservas de la biosfera: Conservaci!oon de la naturaleza para el hombre.Acta Zool. Mexicana 5:4–48.

Halffter, G. 1995. Las reservas de la biosfera y la conservaci!oon de la biodiversidad en el SigloXXI. Ciencias 39:93–96.

Instituto de Biologıa. 2006. Estaci!oon de Biologıa Chamela. National Autonomous Universityof Mexico. http//www.ibiologia.unam.mx/ebchamela (accessed February 14, 2006).

Instituto Nacional de Ecologıa. 1995. Opciones de participaci!oon privada en la conservaci!oon delpatrimonio ecol!oogico de Mexico en !aareas naturales protegidas (ANP). http://www.ine.gob.mx (accessed September 19, 2002).

Instituto Nacional de Ecologıa. (INE). 1996. Convenio de concertaci!oon de la Reserva de la Bios-fera Chamela-Cuixmala. Mexico, DF, Mexico: Secretarıa de Medio Ambiente, RecursosNaturales y Pesca (unpublished document).

Instituto Nacional de Ecologıa. 2000. Chamela-Cuixmala, Reserva de la Biosfera. http://www.ine.gob.mx (accessed April 8, 2002).

Instituto Nacional de Ecologıa. 2001. Rese~nna del ordenamiento ecol!oogico de la regi!oondenominada Costa de Jalisco. http//www.ine.gob.mx/ord_ecol/jalisco (accessed June 6,2002).

70 A. Pujadas and A. Castillo

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

Instituto Nacional de Estadıstica, Geografıa e Inform!aatica. 2000. Anuario Estadıstico delEstado de Jalisco. Instituto Nacional de Estadıstica, Geografıa e Inform!aatica. Mexico,DF, Mexico: INEGI.

Instituto Nacional de Estadıstica, Geografıa e Inform!aatica. 2001. Principales Resultados porLocalidad, Estados Unidos Mexicanos. XII Censo de Poblaci!oon y Vivienda, 2000. Aguas-calientes, Mexico: INEGI.

Kaus, A. 1993. Environmental perceptions and social relations in the Mipimı Biospherereserve. Conserv. Biol. 7(2):398–405.

Kellert, S. R., J. N. Mehta, S. A. Ebbin, and L. L. Lichtenfeld. 2000. Community naturalresource management: Promise, rhetoric, and reality. Society Nat. Resources 13:705–715.

Langholz, J. and W. Krug. 2003. Areas protegidas privadas. Plan de acci!oon para !aareas naturalsprivadas. www.europarc.es.org (accessed January 12, 2006).

Maass, J. M. 1995. Conservation of tropical dry forest to pasture and agriculture. In Season-ally dry tropical forests, ed. S. H. Bullock, H. Mooney, and E. Medina, 399–422.Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Maass, J. M., V. Jaramillo, A. Martınez-Yrızar, F. Garcıa-Oliva, L. A. Perez-Jimenez, andJ. Sarukh!aan. 2002. Aspectos funcionales del ecosistema de selva baja caducifolia enChamela, Jalisco. In Historia Natural de Chamela, ed. F. A. Noguera, J. H. Vega, A.N. Garcıa-Aldrete, and M. Quesada, 525–542. Mexico, DF, Mexico: Instituto de Bio-logıa, Universidad Nacional Aut!oonoma de Mexico.

Noguera, F. A., J. H. Vega Rivera, and A. N. Garcıa Aldrete. 2002. Introducci!oon. In HistoriaNatural de Chamela, eds. F. A. Noguera, A. N. Vega, A. N. Garcıa Aldrete, and M. Ques-ada, xv–xxi. Mexico, DF, Mexico: Instituto de Biologıa, Universidad NacionalAut!oonoma de Mexico.

Nygren, A. 2004. Contested lands and incompatible images: The political ecology of struggleover resources in Nicaragua’s Indio-Maız Reserve. Society Nat. Resources 17(3):189–205.

Ortega, A. T. 1995. El desarrollo socioecon!oomico de Jalisco. Perspectivas de recursos natur-ales. Re. Univ. Guadalajara (April):41–48.

Paz, M. F. 2005. La participaci!oon en el manejo de !aareas naturales protegidas. Cuernavaca,Mexico: Centro Regional de Investigaciones Multidisciplinarias, Universidad NacionalAut!oonoma de Mexico.

Pe~nna, A. L. Durand, and C. Alvarez. 1998. Conservaci!oon. In La diversidad biol!oogica deMexico: Estudio de paıs 1998, ed. Comisi!oon Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso dela Biodiversidad (CONABIO), 184–210. Mexico, DF, Mexico: CONABIO.

Peters, J. 1999. Understanding conflicts between people and parks at Ranomafana, Madagas-car. Agric. Hum. Values 16:65–74.

Poder Ejecutivo Federal. 1996. Plan nacional de desarrollo 1995–2000. Mexico, DF, Mexico:Gobierno de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos.

Poder Ejecutivo Federal. 2001. Programa nacional de medio ambiente y recursos naturales2001–2006. Mexico, DF, Mexico: Gobierno de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos.

Pretty, J. L. and M. P. Pimbert. 1995. Beyond conservation ideology and the wilderness myth.Nat. Resources For. 19(1):5–14.

Price, M. F. 2002. The periodic review of biosphere reserves: A mechanism to foster sites ofexcellence for conservation and sustainable development. Environ. Sci. Policy 5(1):13–18.

Reyes, P. 1991. Las reservas de la biosfera en Mexico: Ensayo hist!oorico sobre su promoci!oon.Biotam 3(1):(Conferencias).

Reyes, J. 1997. Los lımites de la participaci!oon campesina en el desarrollo rural. In Contribu-ciones educativas para sociedades sustentables, ed. Centro de Estudios Sociales yEcol!oogicos (CESE), 115–130. P!aatzcuaro, Mexico: Centro de Estudios Sociales yEcol!oogicos (CESE).

Robson, C. 1993. Real world research. A resource for social scientists and practitioner research-ers. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Sarukh!aan, J., A. Estrada, and A. Perez. 1979. Plan de desarrollo de las estaciones de biologıa delinstituto de biologıa. Mexico, DF, Mexico: Instituto de Biologıa, Universidad NacionalAut!oonoma de Mexico (unpublished document).

Scientific Software Development Berlin. 1997. ATLAS.ti. The Knowledge Workbench. visualqualitative data analysis. Management and theory building. Version WIN 4.2 (Build058). http://www.atlasti.de (accessed January 23, 2003).

Social Participation in a Biosphere Reserve 71

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

Secretarıa de Medio Ambiente para el Desarrollo Sustentable. 1999. Ordenamiento Ecol!oogicode la Regi!oon Costa del Estado de Jalisco. Gobierno del Estado de Jalisco. http://semades.jalisco.gob.mx/site/moet/index.htm (accessed February 26, 2002).

Secretarıa de Medio Ambiente, Recursos Naturales y Pesca. 1996. Programa de !aareas naturalesprotegidas de Mexico 1995–2000. Mexico, DF, Mexico: Secretarıa de Medio Ambiente,Recursos Naturales y Pesca.

Sundberg, J. 1999. NGO landscapes in the Maya Biosphere Reserve, Guatemala. Geogr. Rev.88(3):388–412.

Swift, B., S. Bass, V. Sanjines, V. Theulen, M. Milano, M. L. Nunes, V. Maldonado, A.Cortes, C. M. Chac!oon, V. Arias, M. Tobar, M. Gutierrez, and P. Solano. 2003. Legaltools and incentives for private lands conservation in latin america: Building models for suc-cess. Washington, DC: Environmental Law Institute.

Taylor, S. J. and R. Bogdan. 1987. Introducci!oon a los metodos cualitativos de investigaci!oon.Barcelona, Espa~nna: Ediciones Paid!oos Iberica, SA and Editorial Paid!oos.

Trejo, I. and R. Dirzo. 2000. Deforestation of seasonally dry tropical forest: A national andlocal analysis in mexico. Biol. Conserv. 94:133–142.

United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2006. UNESCO’s Man andthe Biosphere Programme. http//www.unesco.org/mab (accessed April 13, 2006).

Warman, A. 2001. El campo mexicano en el siglo XX. Mexico DF, Mexico: Fondo de CulturaEcon!oomica.

Wells, M. P. and K. E. Brandon. 1993. The principles and practice of buffer zones and localparticipation in biodiversity conservation. Ambio 22:157–162.

Wilshusen, P. R., S. B. Brechin, C. L. Fortwangler, and P. C. West. 2002. Reinventing asquare wheel: Critique of a resurgent ‘‘rotection paradigm’’ in international biodiversityconservation. Society Nat. Resources 15:17–40.

72 A. Pujadas and A. Castillo

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of C

alga

ry] a

t 09:

47 1

5 Fe

brua

ry 2

015