Shaping a song for the stage: How the early revue cultivated hits

Transcript of Shaping a song for the stage: How the early revue cultivated hits

153

SMT 6 (2) pp. 153–171 Intellect Limited 2012

Studies in Musical Theatre Volume 6 Number 2

© 2012 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/smt.6.2.153_1

Keywords

Omar KhayyamThe Passing Show of

1914revueorchestrationSigmund Rombergsongs

Jonas westoverUniversity of St. Thomas

shaping a song for the

stage: How the early revue

cultivated hits

abstract

While working on The Passing Show of 1914, J. J. Shubert hired the young composer Sigmund Romberg to write his first full-length revue. Romberg worked closely with lyricist Harold Atteridge, and the two of them put together the song ‘Omar Khayyam’. The reviews for the show declared it a hit, and it was. This arti-cle explores the development and deployment of a musical hit in the making. Many sources are used to examine the ways in which the number was treated, including the song’s place in the show and the musical languages within the number. This article presents a ‘biography’ of a song from an early show through the lens of the full score. Not only can we see a song – specifically a revue song – being built up to be a hit, but we eventually see the number suffer from events that prevented oppor-tunities for long-term success.

While working on his new production, The Passing Show of 1914, J. J. Shubert (c. 1879–1963) hired the young Sigmund Romberg (1887–1951) to compose his first full-length revue.1 Shubert was confident that Romberg would be able to write several engaging songs for the show, including at least one number that could be sold in great quantities through sheet music. Romberg worked closely with lyricist and librettist Harold Atteridge (1886–1938), and the two of

1. See Westover (2010, 2011), for more on the Passing Show of 1914 and Everett (2007) for more on Romberg. Materials for The Passing Show of 1914 are located in the Shubert Theater Archive. The hand-written orchestrations, piano/vocal versions of songs, a conductor’s short score, orchestral

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 153 8/30/12 8:59:49 PM

Jonas Westover

154

parts and sheet music are available for study. The full script and a wide array of other materials related to the show are also extant.

2. In my estimation, a ‘hit’ from a show is one that begins as a part of a production and then finds its way into a larger sphere of entertainment. It may be that many songs were popular within musical theatre that were never launched into other media, including discs, sheet music or non-Broadway performances. However, this topic is far too expansive to consider here.

3. The most recent look at the revue as a genre can be found in Davis (2000). See also Bordman (1985) for an earlier survey.

4. The New York Public Library, the Library of Congress and the Shubert Archive – among many other locations – have the materials available on a wide range of shows from many eras, all of which might make for fascinating editions.

them created the song ‘Omar Khayyam’. It was placed in four different spots in the show – and therefore heard more than any other song – and it was also performed by two of the musical’s stars, Bernard Granville and Marilyn Miller. The reviews for the show declared it a hit, and it was, for a time.2

This article explores the development and deployment of a song hit in the making. A wide range of sources is used to examine the ways in which the number was constructed, including the song’s place in the revue and the musical languages within the number. The full orchestral version, the original piano–vocal version and the ‘intermezzo’ version and even the orchestrations will be considered alongside the relationships with the stars who sang the tune, placing the song within a historical context that demonstrates the joys and pitfalls associated with the attempt to foist a hit song onto audiences of the Broadway stage in the 1910s.

It is important to begin with a brief overview of the revue itself and what it delivered to audiences. The Passing Show of 1914 was the third revue of the series produced by the Shubert Brothers in competition with their rival, Florenz Ziegfeld Jr, and his Follies, which opened in 1907. The Winter Garden Theater became a home for the revue beginning in 1911, when the Shuberts began presenting shows in the fall, spring, and summer; The Passing Show was their annual summer musical extravaganza. The revue genre flourished during the first half of the twentieth century, from approximately 1907 until 1950, and spotlighted some very talented performers and composers.3 The Passing Show series alone featured such newcomers as George Gershwin, Fred and Adele Astaire, Joan Crawford, and Marilyn Miller, and starred such celebrities as Ed Wynn, The Howard Brothers (Eugene and Willie), George Jessel and George W. Monroe.

The story of the early revue has only recently begun to be told in depth. Probably the most illuminating work on a single revue series is The Ziegfeld Touch, written by two family members of the producer himself. The book includes detailed information which, although sometimes not entirely accurate, is easily the best source for the shows, spotlighting everything from costumes to chorus girls (Ziegfeld and Ziegfeld 1993). Ann Ommen van der Merwe’s book on the songs in Ziegfeld’s productions, The Ziegfeld Follies: A History in Songs (2009) and my dissertation on The Passing Show series (Westover 2010) are two of the first to take the songs from these shows seriously and give them the consideration they deserve. Ommen does an excellent job of demonstrat-ing the details of how songs migrated in and out of shows, providing a fantas-tic discography and catalogue of tunes.

Where my work differs from others is that – for the first time – I have had access to the complete score for the show, including not only the full orches-trations for the songs, but also the ‘webbing’ of the revue. ‘Webbing’ is a term I use to refer to scene change music, musical character introductions, and in general any instrumental music that serves to hold the production together and provide transitions throughout the show. Looking at this material allows access to a wide range of new topics, especially in the realm of orchestration, which I have written about elsewhere (Westover 2011). But not only does this provide a window into the sound world of these shows and their songs, it also allows us to see what music is used, for the ‘webbing’ often contains strains of melodies from elsewhere in the show. This full orchestral score is an excit-ing beginning to what will hopefully be a renewed interest in scores from this period, many of which are available at archives throughout the United States and awaiting scholarly editorial reconstructions.4 Due to the availability

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 154 8/30/12 8:59:49 PM

Shaping a song for the stage

155

5. George Bronson-Howard co-wrote The Passing Show of 1912, but Atteridge wrote the rest of the series on his own.

6. Transformation scenes were common in theatre from the nineteenth century, when a set would magically ‘transform’ into something else via elaborate stage machinery.

of the score, I have tended to veer away from using piano–vocal reductions in this article and have chosen to allow the strains of orchestral colour to shine through. What I wish to accomplish here is a ‘biography’ of a song from one of these early shows as seen through the lens of the full score. Not only can we see the song being built up to be a hit, but we can see how post-show events can affect a song’s longevity.

Crafted from the start by Harold Atteridge, The Passing Show series began in 1912, and ran regularly into the mid-1920s.5 One of the issues in my work has been the existence of scripts (and plots) for these early revues. Looking at a variety of scripts for the 1914 edition alone, I have demonstrated that Atteridge did not simply throw numbers together, but instead worked dili-gently on dialogue and on the placement and flow of scenes (Westover 2010: Chapter 3). This notion of a ‘plot’ – however thin – has been resisted by scholars, but the fact is that these scripts were written and performed during early revues. As more research comes forth about predecessors to the revue, I predict we will develop a more fluid notion of genre, especially in pre-1940s musical theatre (a category in which I believe the revue should be included).

Atteridge described the creation of a revue as one of the greatest chal-lenges for a theatre professional: ‘It must be remembered that there are more principals for whom parts and songs numbers must be arranged, and that, due to the nature of travesties indulged in, constant revisions are necessary up until the very week before the premiere’ (New York Times 1914b: X8). According to him, placing a revue song into a show involved more careful thought than might have been necessary for a ‘book’ show. This might have been because the flow of events could work in almost any way, and only by slow and precise measurement was a revue structured. I do not suggest that book shows are more simplistic in overall form – certainly a topic for future study – but that Atteridge himself must have felt that a straightforward narra-tive allowed for a more formulaic organization. Atteridge was the earliest person involved with these shows and was keenly aware of what elements were necessary for the creation of a good production, so he would have been constantly tinkering with the details up until – as he says – just before opening day. Working closely with J. J. Shubert, Atteridge and director J. C. Huffman (c. 1886–1935) spent weeks constructing these revues before deciding on a composer, but with the significant financial support of the producers, they had several choices.

The Shuberts had in their employ a variety of composers who were musical theatre professionals, from experts such as Louis Hirsch, who wrote most of the music for The Passing Show of 1912, to newcomers like Sigmund Romberg. Romberg was originally hired by the brothers to write a small number of songs for The Whirl of the World, another revue. Romberg was given his first oppor-tunity to become the primary composer of a musical with The Passing Show of 1914, though Harry Carroll (1892–1962), also hired regularly by the Shuberts, contributed four songs. The result thrilled audiences both in New York, where the show ran for 133 performances, and throughout the rest of America, where it toured extensively into the spring of 1915. The musical starred José Collins, Bernard Granville, female impersonator George W. Monroe, and Harry Fisher, and introduced the talented Marilyn Miller. The featured song was ‘Omar Khayyam’, although many other tunes, such as ‘The Sloping Path’, ‘We’re Working in the Picture Game’ and ‘California’ received praise. The show featured a script that included transformation scenes (the burning of San Francisco and an airship floating across the stage),6 many eccentric

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 155 8/30/12 8:59:50 PM

Jonas Westover

156

7. Miller dropped the second ‘n’ from her first name later in life, but at this point in her life, she went by ‘Marilynn’, and so I will use that spelling of her name for this article.

8. Several scenarios remain extant for this show at the Shubert Archive. Scenario 4, as labeled in Westover (2010), includes the first mention of the song. This suggested title might be a reference to ‘Oh, oh, Delphine’, the title song from a show of the same name (1912, music by Ivan Caryll and lyrics by C. M. S. McLellan).

dances, and a long ballet divertissement. The plot concerns Little Buttercup, the Queen of the Movies (Monroe) and her movie studio, where Kitty MacKay (Collins) and Jerrold McGee (Granville) fall in love. A shifty Baron (Fisher) tries to woo MacKay, but is defeated in the end. Theodore Roosevelt, The Misleading Nut, Lady Windermere and Panthea all make appearances, adding to the ‘nonsense’ of the revue. This particular show remains important for several reasons: it was Romberg’s first complete score, as mentioned above; it had orchestrations by Frank Saddler (1864–1921); it directly dealt with thea-tre’s competition with the new medium of the movies; and it was the debut of future theatre mega-star Marilyn(n) Miller (1898–1936).7

‘omar KHayyam’: tHe song’s genesis and construction

Romberg and his creative colleagues hoped to create a hit with ‘Omar Khayyam’, which was heard as a fully fledged song near the end of the first act. Even though its original name, from an early sketch of the scene, was ‘Oh, oh, Omar’, the final title was still about the same character: Omar Khayyam, a poet who likes ‘women, wine, and song’.8 The history (and legend) of Omar

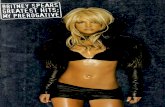

Figure 1: Omar Khayyam by Nathan Haskell Dole (1902 edition). Author’s collection.

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 156 8/30/12 8:59:52 PM

Shaping a song for the stage

157

9. ‘TheTentmaker’wascutfortheeditionshowninFigure1;thereseemtobeawiderangeofvariationsonthetitleandvariousreprintingsofthebook.

Khayyam is extensive and beyond the scope of this article, but the contempo-rary version of the story of Omar and the Rubiyat was popularized through the novel Omar Khayyam the Tentmaker, by Nathan Haskell Dole (1902).9 This novel, in turn, inspired a straight play entitled Omar the Tentmaker, which was well known and well received during the 1913–1914 theatre season. Figure 1 illustrates the cover of the novel.

Due in part to the remarkable popularity of the play during the previ-ous season, Atteridge chose to parody parts of the story in The Passing Show of 1914. As is clear from the script’s development, Omar was a focus for Atteridge early enough that he probably made it clear when hiring Romberg that he wanted a song about the poet/philosopher. Romberg (and probably the whole creative team) anticipated that the hit song of the revue was going to be ‘Omar Khayyam’, and there are several clues as to this hope both in the tune and in the story surrounding it, even in its failure to live up to its crea-tors’ expectations.

The song’s primary focus, in terms of harmony, melody and text, is on exoticism. This particular type of Arab-influenced number is not really meant to connect the listener to any ‘authentic’ Middle Eastern music or lyrics, but rather deals in stereotypes and aural cues that make the song seem exotic. The ‘Other’ in ‘Omar Khayyam’, however, is not necessarily about his geographical- based or racial difference, but more about the character himself. The lyrics by Atteridge, shown below, give a sense of who Omar is rather than where he comes from; his Otherness is derived from his attitude and his characteristic alcoholism rather than from his origin. Omar was a ‘poet man’ who did not take life seriously, eschewing ‘work’ and ‘scheming’ to get out of his responsibilities. Omar Khayyam, according to the song, appeared to be a lovable drinker.

Verse 1 (indicating rhyme scheme)

A Back in hist’ry lived a man who loved his wine,B He praised it loud and long;A He just worshipped ev’ry grape upon the vine,B And told his love in song.C He loved liquor, loved it with his very soul.C He liked the flowing bowl,D Most every day, he wrote this lay: -A ‘A little drink any time is just fine’.

Chorus

E Omar Khayyam, just longed for-E Omar Khayyam was strong for-B ‘Women, wine, and song’.F Give him a drink with bubbles,F Then he’d forget his troubles,B He fooled all day long.G Omar Khayyam, the dreamer,G He never worked, the schemer,H ‘Twas not in his plan,A For under a bough with a jug of wine,A He told the world ‘It’s the life for mine’.H Oh, oh, Omar Khayyam, the poet man.

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 157 9/4/12 12:19:44 PM

Jonas Westover

158

10. See Westover (2010), for the full score.

Verse 2

I Omar wrote about a hundred drinking songs,J That seemed to be his styleI Anytime that he felt blue or had some wrongs,J He’d take a little smile.K He drank highballs and a lot of Persian beer,K For twelve months in the year.L He just would think in terms of drinkK Around the jug you would find him so near.

The Otherness of Omar comes into play musically rather than lyrically. In the opening bars, Romberg uses both pseudo-pentatonic scales and modal mixture to give a sense of an ‘other’ place – a location far from the European diatonicism expressed elsewhere in the score. The string parts for this opening are shown in Figure 2.

The music for Scene Six of Act One, in which Omar and Shireen fall in love and the hero is killed, is written with these tinges of exoticism, with even the underscoring exhibiting these traits.10 Romberg wisely chose to mix the two types of music for this song; the introduction and the verse are written with pentatonic tinges, while the chorus is an un-exotic melody in a major key. Contrasting the two musical languages produced a song that feels both familiar and slightly foreign, just enough to make the number seem different from others in the show, and even separate from tunes in other productions. Using these two harmonic languages within the same piece, Romberg and Saddler hoped to have a hit on their hands.

Figure 2: ‘Omar Khayyam’ opening, showing Romberg’s Othering of Omar in the strings.

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 158 8/30/12 8:59:55 PM

Shaping a song for the stage

159

This dual-language approach was not new to Broadway. One song in particular stands out as a probable model for the young Romberg: ‘Bagdad’ by Victor Herbert (music) and James O’Dea (lyrics) from the musical The Lady of the Slipper (published in 1912 by Witmark and Sons.). In one of the transi-tional spaces in the verse, Herbert makes use of one of the most stereotypical pseudo-Oriental turns in the history of music (see Figure 3, beginning with the music in the soprano part of the third bar).

When the chorus begins, Herbert uses a different musical language – one related to popular songs of New York rather than a non-western tune (see Figure 4). A prominent major key breaks through, shining the light of Tin Pan Alley on this harem number.

Whether or not Romberg knew this song, the musical ideas he used stemmed from a milieu where any good musical idea was copied repeatedly if the formula worked.

Figure 3: ‘Bagdad’ verse, by Victor Herbert, showing stereotypical pseudo-Oriental motif.

Figure 4: ‘Bagdad’ chorus, showing a far more western modality.

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 159 8/30/12 8:59:56 PM

Jonas Westover

160

11. See Westover (2010) for a more extensive discussion of musical form during the early 1910s. See also Tawa (1990).

The emphasis on melody was a feature of ‘Omar Khayyam’, especially evident when you consider the number’s overarching form. The song was written in such a way that the main tune was to be repeated, immediately heard again, and then recalled one more time; this repetition happens in both the verse and the chorus, ensuring that both melodies will be memorable. The sixteen-bar verse is structured A A1 A B, while the chorus is a normative 32-bar section that unfolds in an unusual A A1 A2 B pattern. It seems that Romberg was trying to shape a song that would contain enough inner repeti-tion to make it memorable.11

Undoubtedly, one of the most interesting aspects of the number is its treatment at the hand of Saddler. Romberg’s composition was not poor, but a brief analysis of the song demonstrates that the orchestrated version of the song introduces several musical moments that were not present in the piano–vocal version. In the introduction, Saddler uses effects in the full orchestra to enhance the modal mixture in the melody, first in the winds, harp, and upper strings through the scales, and also with the brass creating the drone under-neath. The strings begin using pizzicato in bar five (Figure 2), accompanying the flute’s soaring melody in the uppermost register (Figure 5), which adds colour and enhances the ‘exotic’ sound.

The music of the verse is generally in a homophonic texture to allow for a clear delivery of the lyrics from the singer. There are musical flourishes during the pauses after the singer’s lines, which are to be expected, and these moments are where Saddler adds to the musical texture. For exam-ple, the ascending semi-quaver arpeggios in the first violin and harp in bar twelve do not derive from Romberg’s piano part, but rather from the orches-tration (see Figure 6).

Saddler thus propels the music through the vocal pause and into its next iteration. However, even underneath the vocal line, Saddler contributes new material that significantly enriches the overall sound. The brief but effec-tive chromatic semi-quaver passage in the cellos and bassoons in bars 10–11 and 14–15, seen in Figure 7, contrasts nicely with the dotted semi-quavers in upper registers and voice, while at the same time it acts as a driving force (not to mention the leading tone) towards the repeated E in the following bar.

Figure 5: ‘Omar Khayyam’ bars 5–8, showing the exoticizing contribution of the flute.

Figure 6: ‘Omar Khayyam’ bars 12–16, showing orchestral flourishes in the first violin part.

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 160 8/30/12 8:59:59 PM

Shaping a song for the stage

161

Figure 7: Bars 10–15 of bassoon and cello parts from ‘Omar Khayyam’.

This might seem like a small contribution by Saddler, but in fact, it signifi-cantly adds to the quality of the song, augmenting the original vocal line while at the same time affixing another layer of musical energy to the tune.

The place where Saddler’s work becomes most noticeable, however, is at the outset of the chorus. The musical motif that can be heard and remem-bered is the tune that accompanies the words ‘Om-ar Khay-yam’ at the outset of the chorus, in bar 25. This passage, seen in Figure 8, exemplifies Saddler’s use of the woodwinds, which represents music that is not present (beyond the melody in the oboe) in the piano–vocal part (Figure 9).

Saddler creates a panoply of echoes throughout the other wind instru-ments with this melody, reinforcing Omar’s name over and over. The first echo is heard on the second beat in the bassoon part, actually overlapping the

Figure 8: ‘Omar Khayyam’ chorus, bars 25–28, showing Saddler’s woodwind orchestration.

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 161 8/30/12 9:00:04 PM

Jonas Westover

162

melody itself. The bassoon’s part is also a repetition of the main melodic line over the held minim G in the oboe. Directly following this is another echo, this time in two parts (the flute and the first clarinet), which is then heard again in the first beat of the next bar, this time in the first clarinet and the bassoon. If those echoes were not enough, Saddler adds two musical gestures that are similar in rhythm, if not voice leading, in the midst of the tune. At the very first beat, in fact, the flute has a quaver gesture that descends, and that is taken up by the second clarinet in the next beat. All of this musical interaction is the creation of Saddler, not Romberg, and it produces a musical impres-sion that the melody alone never could. The reinforcement of the melodic line and the motif itself causes the listener to remember the pattern more vividly than they would have if there was no musical strengthening of the quaver pattern after the initial melody. Not only does this treatment help to create a more memorable tune, but it makes the song musically engaging in a new way, and reshapes the melodic content; all in all, Saddler’s orchestration helps in turning the song into the success that the producers were hoping it would be.

tHe stars wHo sang ‘omar KHayyam’: marilynn miller and bernard granville

‘Omar Khayyam’ was sung by two of the most important players in The Passing Show of 1914, and this is one of the ways that the producers tried to ensure that they had a hit. Bernard Granville was the better known of the two stars at the time, and Marilynn Miller was just emerging as an enter-tainer. Today, Miller is only known by a small number of devotees, but in her day, she was one of the most important stars of stage and screen. After her debut in the 1914 installment of The Passing Show, Miller would continue to appear in shows at the Winter Garden, including the 1915 and 1917 versions of the annual revue as well as The Show of Wonders (1916). Eventually, Miller would join forces with Ziegfeld and become one of the most famous performers of her generation, known for her singing, dancing and acting – a true ‘triple threat’. Star turns in shows such as Sally (1920), Sunny (1925), Rosalie (1928) and As Thousands Cheer (1933) brought Miller extraordinary popularity. Miller also found a home in Hollywood, repris-ing her roles in Sally and Sunny in movies (1929 and 1930, respectively). Her early death due to an infection from a botched nasal surgery (as well

Figure 9: ‘Omar Khayyam’ chorus, bars 25–28, showing the piano–vocal without Saddler’s flourishes.

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 162 8/30/12 9:00:06 PM

Shaping a song for the stage

163

12. In his book The Other Marilyn, Warren Harris compares several facts that tie together Marilynn Miller and Marilyn Monroe:

Not until Marilyn Monroe died, sixteen years after she assumed her new name, could the eerie parallels between the two Marilyns be noticed. Marilyn Monroe also had three unsuccessful marriages – including one in which her name actually became Marilyn Miller – and her last years were a similar study in decline. At her passing, Marilyn Monroe was thirty-six, a year younger than Marilyn Miller when she died.

(1985: 15)

13. ‘Miss Jerry’ was a reference to the play Jerry by Catherine Chisholm Cushing (1914), which opened in March of 1914. The role of ‘Jerry’ was played by Billie Burke (see New York Dramatic Mirror 1914: 12).

as her growing alcoholism) cut her career short (see Harris 1985).12 It was in London while performing with her family’s troupe that she was seen by Lee Shubert and eventually recruited to become part of the cast for The Passing Show of 1914.

Miller’s roles in this revue made use of all of her talents. First of all, Miller was hired to be the prima ballerina for the ballet section of the revue, which was labelled ‘Divertissement’ in the programme. During the second act, she danced in a number called ‘Good Old Levee Days’ while wearing a ‘Mardi Gras’ outfit. Miller’s lines during the production were few – she only actually spoke a few words in the second act as she was invited to appear onstage for her solo performance (see Figure 10).

Her ‘specialty’ was an ‘Imitations’ number where she did impersona-tions of different celebrities as ‘Miss Jerry’.13 Here, Miller had to sing, act and dance, all for the sake of embodying the personalities of the people she was imitating. She did all of this on her own, performing for an audi-ence onstage made up of the other characters, as well as the audience of the Winter Garden; Miller impersonated Olga Petrova while singing ‘Omar Khayyam’, Ethel Levey while singing ‘My Tango Maid’, Julian Eltinge while singing ‘When Martha Was a Girl’, and Gaby Deslys while singing ‘The Tango Dip’.

Elliot Arnold, in his Deep in My Heart, a quasi-biography of the composer, describes Miller’s encounter with Sigmund Romberg via J. J. Shubert. This passage describes Romberg’s first connection with Miller and, specifically, his

Figure 10: Marilynn Miller. Author’s Collection.

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 163 8/30/12 9:00:08 PM

Jonas Westover

164

14. It is surprising that Harris does not include Arnold’s book in his bibliography and that he also does not change the wording in his own book. Since he declines to use citations, however, it is unclear how frequently Harris plagiarizes other sources. For Harris’s use of Arnold’s prose, see Harris (1985: 39–41).

hopes for the song ‘Omar Khayyam’. The schmaltz drips from Arnold’s pen as he portrays the first meeting.

‘I predict a great career for this girl’, J. J. said. ‘Let’s see what you can do to get her started, Romy’.

The girl twinkled another smile and then the producer led her off to meet others in the cast. Romberg followed her with his eyes. … It would be fine if the girl and a Romberg hit could be presented to the public for the first time together.

Several days later he handed her a sheet of music. ‘Look this over, Marilyn’, he said. ‘Bernard Granville will sing it in the first act and you will repeat it in the second. It’s called “Omar Khayyam”’. ‘“A loaf of bread, a jug of wine …” and a song by Romberg’ [she said]. ‘Sung by Miller. See how you like it’ [he replied].

She winked and then set to work with the music. Her voice was clear and sweet and pure, and as she learned the melody and lyrics Romberg was more and more certain this would be his chance […]

The show opened on schedule and Marilyn Miller was a smashing success. She sang ‘Omar Khayyam’ to an enchanted audience and for the first time Sigmund felt a real pride in his work. Marilyn came off the stage. She rushed up to Sigmund and threw her arms around him and kissed him, and he turned her back to the stage and pushed her on again. ‘Go out there and take another bow’, he said. ‘This is the very greatest moment in your life’.14

(Arnold 1949: 221–23)

Arnold’s mythology, then, tries to tie Romberg’s first ‘hit’ with Miller’s debut, and there is no doubt from this point on, both would rise to greater fame. But do we need to turn to Arnold for this knowledge? I include this source as an interesting challenge to scholarship, both in dealing with a somewhat fiction-alized, or at least dramatized, account of a composer’s life and in handling materials that are often rejected out of hand. What Arnold provides are stories about Romberg that, in some cases, help us better understand the composer and, in others, hinder our desire for the type of excellent scholarly explication provided by William Everett in his biography of the composer. As Everett deli-cately demonstrates, it takes a careful hand to unwind what John C. Tibbetts (2005) calls Arnold’s ‘shameless romanticizing’ of Romberg’s life. But there is so much information in the work: are we being irresponsible if we do not place the document under close scrutiny rather than throwing it out entirely? Everett (2007) calls Deep In My Heart a novel, but, as I explore further in this article, enough kernels of truth remain in Arnold’s book that I maintain we can learn something even from this type of fictional approach. As the excerpt above suggests, Miller and Romberg met and connected in some way during The Passing Show of 1914, even if the event did not happen as described. In this case, Romberg probably did not write the song for this petite star, but for the leading man of the revue.

In truth, Romberg probably was more concerned about what Bernard Granville (1886–1936) thought of the song. Granville was one of the show’s romantic leads, playing Jerrold McGee opposite Collins’ Kitty MacKay, as well as the subject of Romberg’s tune – Omar Khayyam himself. Granville, like the

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 164 8/30/12 9:00:09 PM

Shaping a song for the stage

165

15. ItisstrangethatDavismentionsthatZiegfeld‘stoleBernardGranville[…]fromtheWinterGarden’in1912,becausehedidnotmakehisfirstappearancethereuntil1914inThe Passing Show.

other performers, was a mainstay both in vaudeville and on Broadway, and he moved in between the two circuits without difficulty. In fact, Granville’s earliest appearance was with Al G. Field’s Minstrels, where he started at the bottom of the talent pool and worked his way up the ladder: ‘Bernard Granville began his career with this show, in the bugle corps and as a song book seller, graduating into one of the brightest end men and neatest danc-ers in the country’ (Dumont 1915: 6). By 1912, Granville’s act had caught the eye of Flo Ziegfeld, and he was recruited to sing and dance in his Follies of 1912, where a reviewer for Variety notes that the entertainer’s ‘dancing was a riot, but the management [made] him sing too often’ (Ommen 2007: 125). According to Davis, however, Granville was onstage mainly for his voice, with Davis referring to him as a ‘golden voiced tenor’ who was ‘to sing the songs that introduced the girls’ (2000: 107).15 Granville’s greatest strengths were varied, and he seemed to be another true ‘triple threat’, whose acting, danc-ing and singing were all seen with favour. He was an acrobatic dancer and a singer whose career continued through the 1910s into the 1920s; he was also rather handsome, as can be seen in Figure 11. Early in Granville’s career, there was a certain rivalry with Al Jolson, who had only recently emerged from vaudeville himself for La Belle Paree (1911).

In The Passing Show of 1914, Granville performed in several different capac-ities, demonstrating the flexibility he was known for in the articles mentioned above (see Figure 3).

His most important role was that of Jerrold McGee, the romantic lead role in the show opposite Collins’s Kitty MacKay. This character was seen throughout the entirety of the show, contributing to the slight continuity that held the show together as a unit. Granville’s lead role continued when the setting changed to ‘A Thousand Years Ago’, and he became Omar Khayyam,

Figure 11: Bernard Granville. Author’s collection.

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 165 9/11/12 11:19:01 AM

Jonas Westover

166

16. The question of whether ‘book’ songs from this time are placed in a similar manner – which I suspect – can only be answered when full scores of musical comedies from the period become available. It would certainly be a question worth posing in the future.

17. ‘My Sumurun Girl’ (Louis Hirsch/Al Jolson) was a huge hit for Al Jolson from the revue, The Whirl of Society (1912), also produced by the Shuberts.

a ‘travelling player’ who was pillaged from ‘Omar the Tentmaker’. Granville was, without question, the leading man in The Passing Show of 1914, and his version of Romberg’s ‘Omar Khayyam’ was one of the most important parts of the first act. Not only did it open the burlesque sequence, but it was Granville’s only solo song in the revue. Backed by an ‘oriental chorus’, he would have charmed audiences with the song on the first hearing, and they would not have had to wait too long until they heard the song again. Repetition was an essential part of making this tune stand out from the others in the show.

a Hit or miss?

The placement of ‘Omar Khayyam’ in the revue reinforces the notion that the song was intended – even expected – to be a hit. Although the number does not appear until later in the show, the first time the audience actually hears ‘Omar’ is during the Overture, where the song is the third of seven melodies that are played. The piece is heard next when the number is introduced by Omar himself (Granville) at the beginning of Scene Six in Act One. Normally, this would be the only time the tune is sung during the show, since there are no reprises in the revue. However, as the anecdote with Miller demonstrates, the song was used again in Act Two as a part of Miller’s ‘Imitations’ act. Though four different pieces made up the medley, the final tune was ‘Omar Khayyam’, ensuring that the audience had a second opportunity to experience the song in its full form. Finally, the tune is the first of three melodies heard in the Finale, reminding the patrons just one more time that ‘Omar Khayyam’ was not to be forgotten. Through careful placement in the ‘webbing’ of the show as well as in the repeated use of the song, this revue number was aimed right at the listeners’ ears and should have been a piece of sheet music they could not wait to purchase.16

The full score is not mentioned in great depth in contemporary reviews, and usually the authors state that it is either ‘fine’ or ‘adequate’. Romberg and Carroll’s music did not seem to attract much attention, but reviewers occasionally point out songs that stand out, and the results almost always included the featured number. Theatre Magazine, like many others, specifically mentions the bright future for ‘Omar Khayyam’: ‘The songs are particularly bright and tuneful, especially “Omar Khayyam”, which is destined to become very popular’ (Theatre Magazine 1914: 37). Channing Pollock states: ‘There is a genuine song-hit, of the type of “Sumurun” in “Omar Khayyam”, and most effective groupings and business have been arranged for “Way Down East”, “The Girl of To-Day”, “In ‘Frisco Town”, and “Eagle Rock”’ (1914: 325).17 Sime Silverman mentions the music, too:

Of the numbers and music, ‘Omar Khayyam’, sung by Mr. Granville, caught on the best at first hearing, but there are two or three other melodies that will be well liked when more often heard. These are mostly used in connection with the dancing. ‘Good Old Levee Days’ is one. ‘Bohemian Rag’ does well and it should since someone ragged ‘La Boheme’ for it.

(1914: 15)

Kelcey Allen, in the Clipper, also saw some of these songs as future hits: ‘The songs that stood out most prominently were: “Omar Khayyam”, a most

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 166 8/30/12 9:00:10 PM

Shaping a song for the stage

167

18. The Victor Light Opera Company recording has been reissued on CD as Broadway Through the Gramophone: Volume II (1909–1914), Pearl Gems 0083.

tuneful air; “Dreams From out of the Past”, a ballad with a soul; and “Good Old Levee Days”, which has a delightful swing to it. These songs are sure to achieve popularity’ (Allen 1914: 20).

The Times agreed with the others on the true hit of the show:

There is one song, ‘Omar Khayyam’, which comes early in the action of the entertainment and then keeps recurring all during the evening. After the show is over the audience goes out whistling it. It is the pretti-est piece in the show, which has a large collection of delightful songs.

(New York Times 1914a: 11)

The most negative comment is seen in the Tribune, but is not, in essence, very damning when the unnamed author says that ‘the songs are not particularly remarkable’ (New York Tribune 1914: 7). The commentary concerning ‘Omar Khayyam’ is again probably what the producers had hoped for in their crea-tion of the revue – a song that caught the fancy of the listener, so much so that it was even sung while leaving the theatre. Even though the reviewer was probably a seasoned theatregoer himself, if he had catalogued the number of times audiences heard the melody (four times, as mentioned above), he would not have been surprised that they left singing the tune, especially given that the song was the opening music for the instrumental Finale of the show.

So what happened to the song? There were never any recordings made, and it was not even included in the Gems medley recorded by Victor Light Opera Company (Victor 35394); the songs that made it onto gramophone disk were a full version of ‘Eagle Rock’ (Victor 17610) while the Victor medley included ‘Out in Frisco Town’, ‘You’re Just a Little Bit Better’, ‘Kitty MacKay’, ‘Eagle Rock’ and ‘Levee Days’.18 The story of Omar Khayyam is more compli-cated than the other songs from the revue specifically because of Romberg’s relationship with his previous music publisher, Stern and Co. Arnold includes a portion of this story in Deep In My Heart:

Sigmund sat down heavily. ‘Well, the contract is dissolved all right, but it’s too damned late. The song is killed’.

‘How can it be killed? It’s such a success in the show’ [asked Romberg’s brother, Hugo].

‘But how can it become a hit with the people without words? Oh, damn it to hell, why did all this have to happen just now!’

He lit a cigarette and slumped in his chair. He had just returned from a courtroom where his contract with Stern, the music publisher, had been dissolved as being without equity. That was a good thing, but the squabbling with Stern had proven an effective blanket on the success of ‘Omar Khayyam’.

Before the contract was legally declared void, however, Stern had already published ‘Omar Khayyam’ without lyrics. The song thus had only the limited appeal of a semi-classical number. No one could learn the words.

‘I’m afraid we’ll just have to write this one off’, he said to his brother. ‘At least one thing: I know I can write hits’.

‘Did you have any doubts?’ Hugo asked.

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 167 8/30/12 9:00:11 PM

Jonas Westover

168

19. The Starmer in question is either William, A. (born 1872) or Frederick, S. (born 1879), two brothers who ‘were responsible for nearly a quarter of all signed covers in large format from the late 1890s to around 1919, and continued producing cover art into the mid 1940s’. See http://www.cartage.org.lb/en/themes/arts/drawings/Graphicdesign/Coversheetmusic/CoverArtHistory2/CoverArtHistory2.htm. See also http://www.hulapages.com/starmer.htm. Starmer also illustrated the cover of ‘That Bohemian Rag’ for The Passing Show of 1914, published by Remick in 1914.

‘Well, not to have doubts is one thing. But to write the hit is another’. He shook his head. ‘This song could have swept the country if people could only have got hold of the words to hang the music on. And how [Miller] sings it! Like an angel’. He sighed.

(Arnold 1949: 223–24)

In the case of ‘Omar Khayyam’, Arnold may have actually tapped into Romberg’s recollection with a keener accuracy than in other places. For, as we consider the evidence, the proof is in the sheet music itself. Stern really did publish a version of the song, and they did so without the lyrics, calling it an ‘intermezzo’. The cover for the sheet music is shown in Figure 12. From the outset, it is very clear that the artist, Starmer, modelled the cover on the artwork shown in Figure 1, the illustration on the cover of the novel, maintain-ing the layout of the page and depicting a very similar version of ‘Omar’.19

Figure 12: Cover for Stern’s ‘Omar Khayyam’. Author’s collection.

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 168 8/30/12 9:00:14 PM

Shaping a song for the stage

169

20. A few documents regarding Romberg, Atteridge and Stern do remain in the archive, but these seem to all be from 1913. The first letters are to and from Stern regarding using some of Romberg’s music in Shubert productions wherein the rights to all of the composer’s songs remain with Stern (1913a). A memo from the Shuberts to Stern provides a date for the beginning of the Romberg and Atteridge collaboration: 16 September, 1913 (1913b).

21. There is a Rythmodick piano roll of the song (A12702, played by Mabel Wayne), but it remains unclear which version of the song this is. Considering the events surrounding the song, however, it is my guess that this is the ‘intermezzo’.

The inside of the sheet attests to the veracity of Arnold’s prose, too, because the music does not exactly match the song itself, meaning that the ‘intermezzo’ is not simply a version of the song sans lyrics. Instead, it begins with music that resembles the verse, eventually moving into the chorus simi-lar to the one used in the show.

After a four-bar introduction, the verse, seen in Figure 13, takes a new turn in the second bar. The new music uses the quaver figure from the chorus, but in a slightly different manner: the rhythm is the same, but instead of a descending figure followed by a leap that again drops down, the leap here is upwards, apparently preparing for the chorus that is to come. Thus, the inter-mezzo is not the same music that was heard in the show, perhaps a response to a request by Stern or Shubert to keep one job separate from the next.

Whatever the reason for the new material, the sheet music coincides with Romberg’s complaints (via Arnold’s novelesque expansion) about the published number, and the truth is that the composer was probably exactly right about the chances for success given the lack of Atteridge’s lyrics in the publication. The relationship between the Shuberts and Stern is unclear, but, as mentioned earlier, many of the songs (but not all) from The Passing Show series were published by Shapiro, Bernstein, and Co.20 Although the full details of the relationship between the publishers, producer, composer and lyricist are unclear, it does seem apparent that the song was not released in a way that one would expect to produce a triumph. The tune was never put on record, which suggests there were too many problems with the perform-ance rights to the song to even produce a disk.21 The song was killed due to copyright issues and the threat of infringement, thereby stripping The Passing Show of 1914 of the hit that might have been.

As this article demonstrates, a song for a Broadway revue must be considered in all its forms, from the first mention of a tune all the way to the piano–vocal part, from the orchestrated version to the published sheet music. Production history is fascinating and analysis can be illuminating (and useful), but in order to fully understand what a song might mean for a show, one must take in to account the performers and the way the tune unfolded within a musical. Searching throughout a show for every mention of a number – examining the very structure of the performance, including the ‘webbing’ – is important for

Figure 13: ‘Omar Khayyam’ intermezzo verse.

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 169 8/30/12 9:00:15 PM

Jonas Westover

170

22. I want to thank Paul Charosh for contributing his thoughts on this article and for suggesting some alternative sources of information.

considering how that song relates to the revue itself. Beyond this, the recording history of a show and the reviews for the production are all vital to creating the most complete picture of how the musical functioned. ‘Omar Khayyam’ was crafted to be the hit of this show, but it was never given the chance to soar off the stage and into the audience’s living rooms, where it could have flourished and become a more prominent part of the history of the early revue.22

references

Allen, K. (1914), ‘The New York City theatres’, The New York Clipper, 20 June, p. 20.

Arnold, E. (1949), Deep In My Heart, New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pierce.Bordman, G. (1985), American Musical Revue: From the Passing Show to Sugar

Babies, New York: Oxford University Press.Davis, L. (2000), Scandals and Follies: The Rise and Fall of the Great Broadway

Revue, New York: Limelight Editions. Dole, N. H. (1902), Omar Khayyam the Tentmaker, Boston: L.C. Page and Co.Dumont, F. (1915), ‘The younger generation in minstrelsy and reminiscences

of the past’, New York Clipper, 27 March, p. 6.Everett, W. A. (2007), Sigmund Romberg, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.Harris, W. G. (1985), The Other Marilyn, New York: Arbor House.New York Dramatic Mirror (1914), ‘The First Nighter’, New York Dramatic

Mirror, 1 April, p. 12.New York Times (1914a), ‘Fun and glitter in “Passing Show”’, New York Times,

11 June, p. 11. —— (1914b), ‘Harold Atteridge, A rapid-fire librettist’, New York Times,

14 June, p. X8.New York Tribune (1914), ‘The Passing Show of 1914’, New York Tribune,

11 June, p. 7.Ommen, A. (2007), ‘Songs of The Ziegfeld Follies’, dissertation, Ohio State

University, Columbus, OH.Ommen van der Merwe, A. (2009), The Ziegfeld Follies: A History in Song,

Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.Pollock, C. (1914), ‘When lovely women stoop to follies’, Green Book Magazine,

August, pp. 325–26. Silverman, S. (1914), ‘Passing Show of 1914’, Variety, 35: 3, 19 June, p. 15.Stern, J. W. (1913a), ‘Correspondence’ (letters between Schubert brothers and

Joseph W. Stern), Box 1494, Schubert Archive, New York, 15 August. —— (1913b), ‘Correspondence’ (untitled memo, Schubert brothers to Joseph

W. Stern), Box 513, Schubert Archive, New York, 16 September.Tawa, N. E. (1990), The Way To Tin Pan Alley: American Popular Song,

1866–1910, New York: Schirmer Books. Theatre Magazine (1914), ‘At the theatres’, Theatre Magazine, 20: 161, July, p. 37. Tibbetts, J. C. (2005), Composers in the Movies: Studies in Musical Biography,

New Haven: Yale.Westover, J. (2010), ‘A study and reconstruction of The Passing Show of 1914:

The American musical revue and its development in the early twentieth century’, dissertation, Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

—— (2011), ‘Orchestrations for The Passing Show of 1914: An analysis of the techniques of Frank Saddler and Sol Levy’, in J. Koegel (ed.), Music, American Made: Essays in Honor of John Graziano, Sterling Heights, MI: Harmonie Park Press, pp. 439–60.

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 170 8/30/12 9:00:15 PM

Shaping a song for the stage

171

Ziegfeld, P. and Ziegfeld, R. (1993), The Ziegfeld Touch: The Life and Times of Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr., New York: Harry N. Abrams.

suggested citation

Westover, J. (2012), ‘Shaping a song for the stage: How the early revue culti-vated hits’, Studies in Musical Theatre 6: 2, pp. 153–171, doi: 10.1386/smt.6.2.153_1

contributor details

Jonas Westover is a recent graduate from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, where he received his Ph.D. in musicology. His research topics cover musical theatre, film musicals, film music and videogame music, but also include Lawrence Welk and the Backstreet Boys. He contrib-uted over 400 entries to the New Grove Dictionary of American Music (second edition). Recent book chapters include ‘Beethoven and Beer: Orchestral music in German beer gardens in nineteenth century New York City’ in The Nineteenth-Century American Orchestra (University of Chicago Press, 2012, with John Koegel) and ‘“Be A Clown” and “Make ‘Em Laugh”: Comic timing, rhythm, and Donald O’Connor’s face’ in Sounding Funny: Music, Sound, and Comedy Cinema (Equinox, forthcoming).

Jonas Westover has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work in the format that was submitted to Intellect Ltd.

SMT_6.2_Westover_153-171.indd 171 8/30/12 9:00:15 PM