"Shamanism, Tourism, and Secrecy: Revelation and Concealment in Siberut, Western Indonesia." Special...

Transcript of "Shamanism, Tourism, and Secrecy: Revelation and Concealment in Siberut, Western Indonesia." Special...

This article was downloaded by: [24.8.140.189]On: 24 September 2014, At: 04:32Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T3JH, UK

Ethnos: Journal ofAnthropologyPublication details, including instructions forauthors and subscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/retn20

Shamanism, Tourism, andSecrecy: Revelation andConcealment in Siberut,Western IndonesiaChristian S. Hammonsa

a University of Southern California, USAPublished online: 20 Aug 2014.

To cite this article: Christian S. Hammons (2014): Shamanism, Tourism, and Secrecy:Revelation and Concealment in Siberut, Western Indonesia, Ethnos: Journal ofAnthropology, DOI: 10.1080/00141844.2014.938673

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2014.938673

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of allthe information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on ourplatform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensorsmake no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy,completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views ofthe authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis.The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should beindependently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor andFrancis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings,demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever

or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, inrelation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private studypurposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution,reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any formto anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use canbe found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

Shamanism, Tourism, and Secrecy:Revelation and Concealment in Siberut,Western Indonesia

Christian S. HammonsUniversity of Southern California, USA

abstract This essay attempts to explain why international backpacker touristsin Indonesia are so interested in indigenous religion and especially in shamanism.It articulates the indigenous mode of analysis or reverse anthropology of the peoplewhom the tourists visit: in this case, the Sakaliou clan on the island of Siberut, thelargest of the Mentawai Islands off the west coast of Sumatra. According to Sakaliou,tourists seem to be looking for something they have lost, a kind of secret knowledgethat is possessed by the shaman. Unlike other people, who keep their secrets inisolation, the shaman must skilfully reveal some of his secret knowledge as part of apublic performance. It is this secret knowledge, indicated by the skilled revelation ofskilled concealment, for which tourists seem to be searching among the members ofthe Sakaliou clan and their shamans.

keywords Shamanism, tourism, secrecy, authenticity, Indonesia

Why do tourists visit people they think of as primitive, and how doprimitivist tours almost always end up confirming what they arethinking? These questions, central to the ethnography of primitivist

tourism, are difficult to answer precisely because of the ephemerality of thetourist encounter. A solution to the problem lies in taking seriously the expertiseof the people whom tourists visit. For them, while each encounter remains justas ephemeral, patterns emerge over the course of their long experience. The pat-terns may result in stereotypy, as Bashkow (2006) and Causey (2003) describe,but they may also result in what Kirsch calls ‘an indigenous mode of analysis’ or

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20), http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2014.938673

# 2014 Taylor & Francis

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

‘reverse anthropology’ (2006).1 An indigenous analysis of the tourist encounterboth arises out of and informs the encounter and may also be extended to othersocial contexts. By taking this indigenous analysis seriously – as seriously as theethnographer’s analysis – answers to the questions of why tourists visit peoplethey think of as primitive and how primitivist tours almost always end up con-firming what they are thinking may prove to be less elusive.

On the island of Siberut off the west coast of Sumatra, Indonesia, whereinternational backpacker tourists visit forest-dwelling people, the indigenousmode of analysis focuses on the tourists’ unusual interest in the indigenousreligion and shamanism.2 More specifically, the analysis holds that touristsseem to be looking for something they have lost, a kind of secret knowledgethat indigenous people possess (even if the indigenous people themselves arenot exactly sure what this knowledge is). Tourists, they say, believe that thissecret knowledge is possessed by the shaman, called a kerei in Siberut, whosesecrets are different from other kinds of secrets. Unlike a sorcerer, forexample, a kerei possesses a secret, but never performs in secret. He always per-forms in front of others, exposing himself to the sceptical eye of observers and tocharges of fraud. He sometimes performs tricks, but this does not diminish hispower. On the contrary, as Taussig (1998) argues, the skilled revelation of skilledconcealment, usually involving bodies and objects, only intensifies the sensethat he possesses a secret knowledge that ordinary people do not. It is thissecret knowledge for which tourists seem to be searching in Siberut. Tourism– or at least primitivist, international backpacker tourism – is thus not only asearch for authenticity, as MacCannell (1990) says, but also an effort to obtaina secret knowledge that is simultaneously revealed and concealed in thebodies and objects of the shaman.

Everyday Life, with and Without TouristsOf the several dozen clans in the Rereiket region of South Siberut, the Saka-

liou clan has had the most experience with tourists.3 The clan consists of about100 people, including the women (but not their children) who have married intoother clans according to the rule of clan exogamy. Descent is patrilineal, andresidence is patrilocal. Most of the men in the clan, along with their wivesand children, live on Sakaliou’s ancestral land, and most of the rest live inone of three villages nearby built by the government as part of a modernizationcampaign in the 1970s. Sakaliou’s ancestral land is fortuitously located. It is closeenough to the government-built village of Madobag that clan members couldcontinue living on it even as the government forced more distant clans to

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

2 christian s. hammons

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

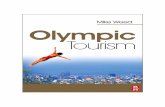

relocate. At the same time, it is close enough to the coast for tourists to reachwithout having to travel for days on end, but far enough upriver to give thema sense that they are travelling deep into the jungle. The clan is divided intofour factions, each with its own longhouse (uma). Although clan membersclaim that they are the only authentic (asli) clan, this division is a departurefrom tradition.4 In the past, each clan had one longhouse on its ancestral landand many smaller houses (sapo) away from the longhouse for each familywithin the clan. As I discuss below, with the resources from tourism, eachfaction within Sakaliou has enlarged one of its smaller houses to the size andstatus of a longhouse. However, Sakaliou also continues to act as a singleclan. The factions adhere to the obligations of reciprocity, hold bridewealthnegotiations and ceremonies together, and in general, despite some tensions,consider themselves to be members of the same clan. This is not to say thatthere is no competition between individuals, factions, or clans. As I haveargued elsewhere (Hammons 2010), conventions of reciprocity insure thatpeople ultimately compete not over resources but over the social prestigeinto which those resources can be converted. With regard to the tourism indus-try, the little money that Sakaliou makes is almost always invested in things thatconfer prestige, like larger houses, larger ceremonies, and larger exchanges. Inthis sense, Sakaliou is authentic, and it may be the only authentic clan (Figure 1).

Sakaliou has been hosting tourists since the 1970s, so clan members have hada couple of generations to make sense of tourists, and they have learned how tohandle them and the guides who bring them to Siberut. The guides areoccasionally from the same country as the tourists, but they are more often

Figure 1. Three membersof the Sakaliou clan returnhome through the denseforest to one of the clan’slonghouses in preparationfor a puliaijat ceremony thattourists will attend. Photoby the author.

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

Shamanism, Tourism, and Secrecy 3

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

from elsewhere in Sumatra or Indonesia. The vast majority are Minangkabaufrom West Sumatra. If Sakaliou is, more or less, happy to host the tourists,clan members are not always happy to host the guides, on whom theydepend for getting the tourists there and by whom, without doubt, they areexploited. They put up with the guides for now because the guides bring tour-ists, and tourists bring some benefits. Tourists provide a diversion from theroutine of daily life, a modest amount of cash, and more than a modestamount of prestige. Another important benefit of hosting tourists is that theirpresence makes Sakaliou’s refusal to participate in the Indonesian government’smodernization programmes more tenable. Tourists first arrived during theheight of the government’s campaign to modernize the upriver clans byforce, an event I describe below. More than three decades later, although thegovernment’s policies have been relaxed, Sakaliou continues to host touristsin part because of the memory of these events. Tourists are a kind of firewallagainst a potentially resurgent state.5

If members of Sakaliou are able to articulate their own motivations forhosting tourists, they are, as I have suggested, puzzled about the motivationsof tourists for visiting them. In general, they say that tourists come from cold,crowded cities, where no one knows anyone else, and that it is probablyinteresting for them to see something so different. For the few people whohave travelled to Padang, Jakarta, or even Tokyo, the opinion is partly basedon personal experience, but for those who have not travelled off of Siberut,the opinion is mostly based on the responses of tourists to their questions.They often ask tourists why they have come, and indeed, most of the responsesare puzzling. In the absence of tourists (i.e. in conversations between me andSakaliou), they say that tourists seem to be looking for something they havelost, the secret knowledge that is ultimately located in the bodies and objectsof the shaman. Tourists, they say, are interested in their way of life in general– in the longhouse, in the skulls of animals and carvings that adorn it, in thetattoos that adorn people, in sago and the other foods they eat, and in theirsocial relations and history. But tourists are said to be especially interested inSakaliou’s religious ceremonies, and beyond all else, they are interested in theclan’s shamans, whom they believe to possess a secret knowledge. On theone hand, Sakaliou understand this. Ordinary people turn to the shaman intimes of illness precisely because they are thought to know something thatordinary people do not. On the other hand, there are many people in Siberutwith secret knowledge. From ordinary people to sorcerers, everyone hassecrets, but tourists seem to be most interested in the secrets of the shaman.

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

4 christian s. hammons

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

What is it about the shaman’s secret knowledge that sets it apart? Whilemembers of the Sakaliou clan claim that they are all authentic, they alsoacknowledge that shamans are the most authentic among them. Bound bytaboos that do not apply to ordinary people, shamans continue to wear aloincloth, to grow their hair long, to be tattooed, as well as avoid certainfoods and other practices that are not prohibited for other people. More impor-tantly, they do possess a secret knowledge that is revealed to them over thecourse of their training and initiation. This knowledge enables them to seespirits all of the time, and the spirits, as well as other shamans, provide themwith the magic formulas of medicines and other ritual practices that enablethem to heal people. The shaman’s knowledge is not entirely secret,however. Much – but not all – of what he knows and does is also known byordinary people, and some ordinary people know secrets that the shamandoes not. For example, during the most important religious ceremony, calledthe puliaijat, the head of the household in which the ceremony is held addressesthe ancestral altar in the clan’s longhouse with a magic formula that is keptsecret from other clans. Sorcerers, who may or may not be shamans, alsoknow magic formulas, and even ordinary people usually know a few.However, unlike the master of ceremonies, the sorcerer, and the ordinaryperson, who act alone, the shaman performs in front of others, exposinghimself to the sceptical eye of observers and to charges of fraud. Even if theshaman works alone (and in Siberut, he does not), he must also work withothers, if no one else, a patient. It is this simple fact that makes the shaman’ssecrets different from the secrets of others: he must run the risk of exposingthe secret. And it is this simple fact that makes tourists want to see him: asmuch as they hope that he is the real thing, they cannot deny that he maynot be.

The relation between secrecy and exposure has been productively exploredby Taussig.6 In an article titled ‘Viscerality, Faith, and Skepticism: AnotherTheory of Magic’ (1998), Taussig argues not only that faith depends on scepti-cism, and that revelation of a secret creates the scepticism on which faithdepends, but also that that revelation of the secret often involves ‘ . . . somephysical substance or object that exists in relation to the insides of the humanbody’ (1998: 221). Ritual is a stage for the revelation of the secret that underliesfaith, centring on such a concealed object. As Taussig writes,

The real skill of the practitioner lies not in skilled concealment but in the skilledrevelation of skilled concealment. Magic is efficacious not despite the trick but on

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

Shamanism, Tourism, and Secrecy 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

account of its exposure. The mystery is heightened, not dissipated, by unmasking, andin various ways, direct and oblique, ritual serves as a stage for so many unmaskings.Hence power flows not from masking but from an unmasking which masks morethan masking does. (1998: 222)

In his book Defacement: Public Secrecy and the Labor of the Negative (1999), Taussigdistinguishes between the secret and the public secret. He defines a public secretas ‘ . . . that which is generally known, but cannot be articulated . . . ’ (1999: 5). Asecret can be revealed or exposed, but a public secret cannot. The revelation of apublic secret always remains only a ‘tensed possibility’. The revelation of asecret is what creates the public secret. In other words, just as faith dependson scepticism, the public secret, which cannot be revealed, depends not onlyon the secret, but on the secret exposed. And if the exposure of the secretusually involves an object that has been concealed inside the human body,then what underlies the public secret is not the exposure of just any secret,but the revelation of the concealed object.

The fact that shamans perform in front of others is thus much more thanwhat it seems. Their secret knowledge depends on revealing that knowledgeitself – or at least something of it, and this something usually involves bodiesand objects. With the skilled revelation of skilled concealment, the shamanscreate a public secret, of which there are many in Siberut. The most obviousone is that the shamans exist at all. They were officially banned by the Indone-sian government in 1954.

A Brief History of ShamanismTo understand Sakaliou’s theory of tourism, it is first necessary to understand

the particular history of shamanism in Siberut.7 From ‘first contact’ with Eur-opeans to the present, the shaman has been seen by most nonindigenouspeople not only as a fraud, but as the closest thing to a leader in a leaderlesssociety. If nothing else, the shaman is a leader of the indigenous religion.In one of the earliest accounts of the Mentawai people, from 1799, Crisp writes,

The religion of this people, if it can be said that they have any, may truly be called thereligion of nature. A belief in the existence of some powers more than human cannotfail to be excited among the most uncultivated of mankind, from the observations ofvarious striking natural phenomena, such as the diurnal revolution of the sun andmoon; thunder and lightning; earthquakes, &c. &c. [sic] nor will there ever bewanting among them, some of superior talents and cunning who will acquire an influ-ence over weak minds, by assuming themselves an interest with, or a power of con-

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

6 christian s. hammons

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

trouling [sic] these superhuman agents; and such notions constitute the religion of theinhabitants of the Poggys. (1799: 86)

Here is the first mention of the shaman, and it is not a flattering one. He is ofsuperior talents, but he is also cunning. He uses his talents to influence weakminds, which associate powers more than human with striking naturalphenomena. Such is probably to be expected from the late eighteenthcentury and throughout the colonial period, which began in Siberut in 1904.Although the Dutch maintained a laissez-faire policy on the island, the mission-aries they supported were adamant about eradicating the indigenous religion,and shamans in particular were blamed for the ‘primitive, backward, and ignor-ant condition’ of the Mentawai people (Persoon 2004: 146). Moreover, asPersoon argues, ‘The government officials of the Indonesian nation-state havebasically kept the same attitude’ (2004: 146). After Indonesian independence,in 1954, the indigenous religion was officially banned by the government,forcing the indigenous people of Siberut to convert to one of Indonesia’s officialreligions. People who refused were intimidated or imprisoned, and anythingassociated with the indigenous religion, such as ancestral altars, drums, andthe shaman’s paraphernalia, was destroyed. In the 1970s, a new campaign bythe government specifically targeted the shaman. Local officials escorted bypolice marched into the forest, imprisoned important shamans, and intimidatedmany more by disrobing them, cutting their hair, and destroying their parapher-nalia, especially a box that a shaman makes as part of his training and initiationand guards closely for the rest of his life.

It is around this time that tourists suddenly showed up with a slightly differ-ent opinion of indigenous religion and shamanism, and they clearly had a chil-ling effect on the government’s efforts to modernize by force. I cannot detailhere the entire history of the tourism industry in Siberut (see Bakker 1996)and its role in the indigenous people’s relations with the state (see Hammons2010), nor can I offer an ethnographically informed explanation of tourists’motivations for coming to visit Sakaliou. Reeves (2001) has analysed the pro-motional materials, and Persoon (2003) has analysed the visual representations.The discourse is not surprising. Reeves argues that it represents the MentawaiIslands as

. . . an idyllic Past, in which the people live according to Tradition, a tradition thatendured over eons, unchanged, in Stasis. They are, hence, Primitive, Unsullied bythe corrupt ways of so-called Civilization, uninterested in Material things and the

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

Shamanism, Tourism, and Secrecy 7

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

tyranny of Technology. They therefore live in Harmony, both with each other andthe environment, a Sacred way of life in a Paradise on earth. (2001: 4)

MacCannell (1990), of course, has argued that tourism in general is a search forthe authentic experience that is lacking in modernity, and that cultural tourismin particular is a search for the kind of authenticity that Reeves describes. Tour-ists are almost certainly motivated by this discourse. But as members of theSakaliou clan understand it, when the tourists are there, they are most interestednot only in the indigenous religion, and not only in the shaman, but in thebodies and objects of the shaman and the skilled revelation of skilled conceal-ment. In other words, the discourse may get them there, but the tourists’ experi-ence of authenticity only arises in the context of the trek itself, and the trek ischaracterized by secrecy and exposure. As secrets are revealed, public secretsare created, and all of these public secrets are underwritten by the shaman’sskill.8

The TrekThe tourism industry in Siberut began informally in the 1970s and, despite

efforts by the government to formalize it, tourism in the interior of Siberuthas remained informal.9 Typically, a small group of Western tourists (5– 15

people) is recruited by Minangkabau guides in Bukittinggi, a node on thetourist circuit in Sumatra. Siberut is advertised as a mystical jungle paradise,with Stone Age people living in harmony with their environment andshamans maintaining the delicate balance between humans, spirits, andnature. (Increasingly, the advertisements also portray this paradise as threatenedand vanishing; the trek may be the last chance for tourists to see it or anythinglike it.) At a cost of about $200 for a 10-day trek, 3 days are spent in transitbetween Bukittinggi and the interior, beginning with a 3-hour drive byminivan from Bukittinggi to Padang, an overnight ferry ride to Muara Siberut,a brief break on the coast, followed by a 3-hour ride in a motorboat upriverand into the forest. The second night of the trek – the first on the island – isspent in a longhouse. For the next five days, the group walks from longhouseto longhouse, sometimes staying in one place for two or three nights. Duringthe days, if the tourists are not walking through the forest, they stay in ornear the longhouse or go on day hikes to a waterfall or to watch some activity,such as sago-making or fishing. At night, they may observe a ceremony, if one isalready planned; if not, the occupants of the house may stage one. At the end ofthe trek, before boarding the motorboat to go back downriver, the tourists dress

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

8 christian s. hammons

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

up in traditional clothing and pose for pictures. They may trade for or buy sou-venirs or get a tattoo. Exhausted and usually ready to leave, they go back down-river to Muara Siberut, back on the ferry for the overnight trip to Padang, andback by minivan to Bukittinggi.

The treks are not limited to Sakaliou. There are other places, like Buttui andAttabai, that tourists visit, but Sakaliou’s land lies just beyond a split in theRereiket River, between the government-built villages of Rogdog and Ugai,and it is usually the first place that the tourists stop. Each guide has a set oflonghouses and clans with whom he likes to work, which sometimes overlapswith the sets of other guides. When two or more treks are in the interior at thesame time, the guides may coordinate with each other so that they do notoverlap. They may also take advantage of the tourists’ disorientation in thejungle and circle for hours on the same land to create the illusion of travellinga great distance between two longhouses which are in reality very close. Clanmembers are usually complicit in creating this illusion. If they were not, theguides would take the trek somewhere else, as they indeed did at one time inthe past. Madobag and the other government-built villages are usuallyavoided in the same way – by walking around them – although some guidesinclude them as a kind of contrast to the authentic lifestyle of the peoplewho live in longhouses on their ancestral land. Again, clan members are com-plicit in this. In fact, one reason that a trek can remain solely on their ancestralland is that they have several different longhouses – or what look like differentlonghouses. Traditionally, there was one longhouse for each clan on its ances-tral land. Families within the clan built smaller, temporary dwellings at variousdistances away from the longhouse, near gardens, trees, or other resources,where they kept their own chickens and pigs and lived for various periods oftime. All families were expected to return to the longhouse for communalceremonies and other clan events. With the resources from tourism, Sakaliouenlarged several of their smaller houses to the size of a longhouse and decoratedthem appropriately.10 Tourists are thus under the impression that they arevisiting a clan with several different longhouses on a large piece of land thatis, in fact, no larger than most others.

The itinerary of the trek is thus a kind of illusion, an illusion that themembers of Sakaliou are complicit in creating. But then an interesting thinghappens: the secret is slowly revealed. An astute tourist almost always noticesthat the group is walking in circles, and if one does not, a porter or cookhelps them to realize it. The expressed aim in doing this is to circumvent thepower of the guide, who has almost always agreed to pay the porter or cook

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

Shamanism, Tourism, and Secrecy 9

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

less than what he wanted. They hope that the tourists might be sympatheticand offer them additional cash or even stay in the longhouse (and pay) afterthe other members of the group have gone back to Bukittinggi. At the sametime, they cannot suggest that the entire trek is an illusion; they must insistthat they are authentic, that the longhouses are authentic, and that everythingbut the itinerary is authentic. To do otherwise would end the industry. Thepoint here is that secrecy – and the skilled revelation of it – does not conflictwith the authentic. In fact, clan members are well aware that the revelation ofthe guide’s deception (and their own complicity up to the point of its revelation)only works to heighten the sense among tourists, if not among clan members,that they, and not the guides, possess the secret that their guests have come sofar to find.

In the late afternoon or evening, after a long day of slogging through the forest,the tourists arrive at a longhouse, exhausted, red-faced, and covered with mos-quito bites, much to the bemusement of the house’s occupants, if they arethere, and they usually are – word travels fast on Siberut. This is especiallytrue on the first day, but the scene is usually repeated with each new longhouse.If the occupants know that tourists are coming, they may clean up the longhouse,which is to say that they tidy it up, as well as remove and burn discarded plasticwrappers and, occasionally, hide things that would shatter the illusion of authen-ticity. They may hide, for example, a radio, a wristwatch or Swiss Army knifefrom a previous tourist, or a chainsaw. Although I have not personally witnessedit, they may also change clothes, putting on a loincloth instead of shorts. Tra-ditionally, the house is divided into three large rooms, a back room with twofire pits, where women cook and sleep, a middle room with a ceremonial firepit, where men sleep and ceremonies are held, and a front room, a kind ofcommon area where people spend most of the day working and socializing.The tourists are confined to the front room. Cigarettes and tobacco are distribu-ted – guests arrive – and after a period of uneasy silence, the tourists and theoccupants begin to engage in conversation, usually mediated by the guidebecause of the language barrier.

When the occupants do not speak English, the guide can control the conver-sation and other interaction. When they do speak English, the guide asks themto refrain, but invariably, they engage in conversation with the tourists directly.This is especially true of members of the Sakaliou clan, whose English is oftenbetter than the guide’s. What is surprising to the tourists is not just that theoccupants speak English, but as with the itinerary, that the guide has askedthem to refrain from speaking English. Again, the secret is revealed, the decep-

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

10 christian s. hammons

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

tion exposed – only to be replaced by another one. The hosts speak in brokenEnglish even though they are more fluent than that, and they ask questions towhich they already know the answer. One favourite of the Sakaliou clan is toask Americans about the moon. Clan members have heard that Americanshave visited the moon, and they ask American tourists if they have been andwhat it is like. They know from many previous tourists that most Americanshave not visited the moon, but they ask the question anyway. This is notentirely inconsistent with indigenous modes of conversation and storytelling.They often tell and listen to the same stories over and over again. However,in the context of conversation with tourists, it is clearly a deception thatlends to the illusion of authenticity. They could just as easily engage in conver-sation about Jackie Chan or the World Cup, but they refrain. The point is tocircumvent the guide, reveal the secret, and create another one that may berevealed later.

A final example of revelation and concealment during the trek occurs withthe one thing other than the shaman that most tourists really want to see,the puliaijat ceremony, staged or otherwise. Tourists are allowed to attend analready-planned ceremony if they are staying in the longhouse in which itwill occur. But they have to pay for the privilege, whether they know it ornot. The guide may make an additional payment to the head of the householdout of the money he has already collected from the tourists, cutting into his ownprofit, but more often, he approaches the tourists, explains to them that therewill be a ceremony, and that a token payment must be made for the addedexpense. More chickens and pigs will be killed because the tourists are there.A staged ceremony usually follows the same logic, but the guide approachesthe head of the household first and negotiates a price before he approachesthe tourists and asks for the token payment. In other words, he pretends thatthe ceremony was already planned. If the token payment cannot be made,either because the head of the household asks for too much or because theguide and tourists do not want to pay anything at all, the guide has nochoice but to leave and move on to the next longhouse. A nonstaged ceremonynormally lasts for weeks and involves weeks of preparation beforehand, thestrict observance of taboos, the sacrifice of dozens of chickens and pigs, commu-nion with the ancestor spirits, and critically, a concluding hunt. In the staged,condensed version, the taboos are observed and a few chickens and pigs arekilled, but the normal business of contacting the ancestor spirits and goingon the hunt is either minimized or omitted completely. Sakaliou uses theIndonesian word pesta (feast, party) to refer to the staged version. It is a commu-

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

Shamanism, Tourism, and Secrecy 11

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

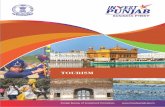

nal meal with singing and dancing, rather than a puliaijat ceremony, which isdefined in part by the presence of the ancestor spirits. Again, as with the itiner-ary and speaking English, the tourists usually find out whether the ceremony isstaged or not. Curiously, if the token payment can be negotiated, they areusually still eager to see the staged version. The deception is revealed – thisceremony is not real – but the tourists are convinced that the real showexists, and this is as close as they will come to it (Figure 2).

The conflicts between hosts and guests that arise over the token payment fora ceremony raise another important issue, and that is the issue of minta. TheIndonesian word minta means to ask for or to request. It can also mean tobeg. Bakker (1996) reports that Sakaliou was often referred to by clans thatdid not host tourists and by some guides as ‘the Minta-wai people’, implyingthat clan members were beggars. Although they do often ask for things,especially cigarettes, I have argued elsewhere (Hammons 2010) that this is asmuch a result of reciprocity as it is a result of trying to get something fornothing from tourists (cf. MacCannell 1990). Nevertheless, unlike the problemof negotiating the token payment for a ceremony, the problem of minta canplague the entire trek because the tourists, despite being warned by theirguides, are simply unable to cope with it. They interpret it as trying to get some-thing for nothing. Taking photographs is especially problematic because eachhouse has different rules about when and how much a person should be com-pensated for allowing their picture to be taken. Tourists can get frustrated,making the problem worse, such that by the end of the trek, they are ready

Figure 2. Three touristsare decorated by a memberof the Sakaliou clan inpreparation for a puliaijatceremony. In this case, theceremony was not staged;the tourists happened toarrive just as it wasbeginning. They were asked,however, to make a tokenpayment for the addedexpense that would beincurred by their presence.Photo by the author.

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

12 christian s. hammons

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

to go home not only because it is hot and muddy and mosquito-ridden, but alsobecause they are annoyed by their hosts’ frequent requests. For many, mintaundermines the illusion of authenticity, which has been created by the carefulexposure of secrets. Minta threatens to explode the public secret that touristsand clan members share: that authenticity is always deferred.11

Because of the repeated deferral of authenticity during the trek, the shaman isessential to the tourist experience. My argument is that with the shaman, there isa final deferral of authenticity that is, in short, satisfying to the tourist. It is satis-fying because unlike everyone else, the shaman is supposed to have secrets, andhe is skilled in revelation and concealment, which is to say that unlike everyoneelse, he knows how to reveal in such a way that the exposure of the secret bringsauthenticity as close as possible. It is not difficult for tourists to see a shaman inSiberut. They are relatively numerous – about 1 out of every 10 men is a shaman– and they are easy to identify. They wear a red or red and white loincloth.Their hair is long. They usually have tattoos, and they are usually adornedwith certain headbands, necklaces, and bracelets. Seeing them perform is adifferent matter. As with the puliaijat ceremony, if the tourists happen to bestaying in a house where a healing ceremony is being held, they will beallowed to attend if they make an additional payment. The payment is nego-tiated between the guide, the head of the household, and the shaman in attend-ance. Unlike the puliaijat ceremony, to the best of my knowledge, there is nostaged healing ceremony. The business of the shaman is just too serious.

The Shaman’s TrickToday, Sakaliou says, shamans do not have the power to die and return to

life, but in the past, they did. Pageta Sabbou, the common ancestor ofWestern, Indonesian, and Mentawai people, knew the secret knowledge thatshamans know today, but he did not teach it to people until after Siberut andthe rest of the Mentawai Islands had been settled. According to anothermyth, an orphan boy named Maligai was rescued from death by a man andhis wife. At the time, there were too many people, not enough food, and toomuch illness and death. In a series of dreams, Maligai’s ‘father’, PagetaSabbou, taught him the proper way to live so that hunger and illness couldbe avoided and death could be deferred until old age. He taught him how tobuild a longhouse, how to raise chickens and pigs, and how to cure peoplewith medicinal plants, ritual, and ceremony. In other words, he taught himthe indigenous religion and shamanism. Envied because of his knowledge,Maligai was killed, but it soon became apparent that what he had learned

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

Shamanism, Tourism, and Secrecy 13

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

from Pageta Sabbou was the proper way to live, that the indigenous religionenabled people to avoid hunger and illness and defer death until old age.Most of Maligai’s knowledge spread until it was known by all of the Mentawaipeople. Only shamans, however, know how to cure. Secrecy was the penalty forMaligai’s death.

Today, shamans hold Pageta Sabbou, not Maligai, as a kind of patron saint.There has been a diminution of power since Maligai’s death, so shamans cannotdie and return to life, and because of this, they must guard his secret knowledge,revealing it only to other initiated shamans. They can, however, communicatewith the ancestor spirits, entering the world of the dead and returning to theworld of the living, or the world of humans and the world of spirits more gen-erally, although these two worlds are more coexistent or overlapping than sep-arate. In fact, what separates the shaman from the ordinary man is, by virtue ofhis apprenticeship and initiation, he sees spirits all of the time. He does not entertrance in order to see them. He sees them all of the time. In the initiation, he failsto see them, turns his back, then looks in a mirror and sees them behind him.Because they are behind him, they are harmless. He turns around, but theyremain harmless, and he remains able to see them. All of the other tricks ofthe trade – the medicines, and the songs and dances – the shaman learnsfrom other shamans. In an article written by Loeb in 1929, a master shamansays to his newly initiated apprentice,

Boy, I am satisfied with you, for you have questioned the altar, for you have spokenwith our fathers the wood spirits. There yet remain small things [the tricks and legerde-main of the profession] which you do not know. If you sing as I do to the altar, then youwill do it correctly. As for the other matters, you have but to listen to the advice of theother seers, and presently you will know everything. (1929: 73; emphasis added).

Being able to see the spirits is essential. But the small things, the tricks and leger-demain, are everything.

What sorts of tricks do shamans use? There are many, and there is no sensein worrying about revealing them because although shamans themselves cannotadmit they use them, ordinary people often point them out. In one of the mostimpressive demonstrations, an illness-causing substance called bajou is removedfrom the body of a patient. In general, a cure is effected by purifying the body ofthe patient, retrieving his or her soul, and placing it on the crown of the head.A cure requires constant consultation with the patient, his or her family, andvarious spirits, as well as the application of medicines and the sacrifice of

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

14 christian s. hammons

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

chickens and pigs. As part of purifying the body to make it attractive to thesoul, the material manifestation of illness, bajou, is removed. (The cause of theillness is actually the encounter between the human soul and a spirit; theencounter is manifest in the body as bajou.) With at least two shamansdancing around the patient, one falls to the floor in trance, a sign that thespirits are there, and another holds a plate that mysteriously fills up withwhat looks like dark blood.12 The bajou extracted, it is discarded in the river,and the more important business of keeping the patient’s soul close to his orher body can commence. The soul never stays put for long, however. Theshamans chase it. Medicines have the dual purpose of purifying the body andmaking it attractive to the soul. Only when a sacrifice reveals in the entrailsof a chicken or the heart of a pig a sign that the soul will remain close doesthe ceremony come to an end.

This brief and somewhat superficial description includes no less than threemoments of revelation and concealment, betraying, as Taussig says, theshaman’s trick. Notice that the illness itself is the manifestation inside thebody of an encounter outside the body between a human soul and a spirit.The shaman consults with the patient and his or her family, as well as withspirits, whom the patient and other people cannot see (or hear), except in theshaman’s performance. The dance leading up to the removal of the bajou issimilar in the sense that it is the presence of the spirits that causes the firstshaman to fall into trance. This presence, which other people cannot see, mani-fests itself in the body of the shaman, which they can see. Simultaneously, thesecond shaman removes from the body of the patient the material manifestationof the illness caused by the encounter with another spirit somewhere else.The plate fills with blood, which is then discarded, and the shamans sing anddance and chase the soul of the patient. Medicines are applied to the body,not because they have medicinal properties (although they might), butbecause they have magical properties, which is to say that spirits can interveneon behalf of the patient’s soul. The same is true of the sacrifices. The spirit of thechicken or pig contacts other spirits and then conceals a message in its ownentrails as it dies. The entrails are removed and read. To rephrase, the illnessitself reveals that there was an encounter; the shaman’s performance revealsthe presence of spirits; things unknown are made known in the body; andthe most important things are extracted – bajou and the message. There is nodoubt that the patient is sick and no doubt that he or she is sick because ofthe encounter and soul loss. There is some doubt about the removal of thebajou. But how could the shaman fake the message in the entrails (Figure 3)?13

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

Shamanism, Tourism, and Secrecy 15

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

Conclusion: On Revelation and ConcealmentTourists want to learn about the indigenous religion. The religion is not

limited to shamans, but shamans are essential to it and possess knowledge ofit that others do not. Thus, tourists do not just want to know about the indigen-ous religion, they especially want to know about shamans. The question I havetried to address is not so much why tourists think they are interested in the indi-genous religion and shamanism as why Sakaliou thinks tourists are interested inthe indigenous religion and shamanism. And the answer is that the indigenousreligion is a lost knowledge, a secret knowledge, and nothing (except revelation)inspires a secret so much as another one. Secrecy magnifies reality.

There are several public secrets at work here. Each is shared by different groupsof people, although Sakaliou is always one of the groups. There is the public secretshared by members of Sakaliou only that shamans do not see spirits all of the time.Then there is the public secret shared by Sakaliou and the state that shamans exist inthe first place. Then there is the public secret shared by members of Sakaliou andtourists that the trek is – or is a re-enactment of – first contact. If this is revealed (i.e.cannot be sustained), it is replaced by the public secret that even though they havebeen contacted, they have remained authentic. The trick for clan members is tomaintain this public secret by revealing other secrets that suggest it. Theyblame the guides and the state: despite the guides, despite the state, we are auth-entic. And if our lives are not proof enough, here is the shaman. But then there isthe public secret shared by members of Sakaliou, the state, and tourists that shamansmight be a fraud. Among clan members, the balance between faith and scepticism

Figure 3. One of theSakaliou clan’s shamansreads the entrails of a pig.Photo by the author.

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

16 christian s. hammons

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

is titled towards faith. For the state, it is tilted towards scepticism. Among tourists,it is more balanced. Nevertheless, it is not only the shaman, but the shaman’s trick-ery, that underwrites all of these public secrets. It underwrites clan members’ beliefthat the shaman does not see spirits all of the time; Sakaliou and the state’s beliefthat the shaman does not exist; clan members’ and tourists’ belief that Sakaliou isauthentic; and clan members’, the state’s, and tourists’ belief that the shaman is afraud. So, when I say that Sakaliou thinks that tourists are looking for a secretknowledge that the shaman has, this is what they mean: they are looking for auth-enticity, as MacCannell says, that is produced through trickery, through the rev-elation of concealment, which as far as I know, is not what MacCannell says.Authenticity may be ‘ . . . that beyond that is permanently beyond the horizonof being’ (Taussig 1998: 247), but the shamans of Siberut bring it awfully close.

AcknowledgementsI would like to thank Rupert Stasch for organizing the panel at the AmericanAnthropological Association 2011 Annual Meeting, at which this essay was originallypresented, for his insightful comments from then until now, and for patiently perse-vering until the papers on the panel were published. I would also like to thank theother panel members Magnus Fiskesjo, Michelle MacCarthy, George Paul Meiu,and Anke Tonnaer, as well as the discussants Janet Hoskins and FrancescaMerlan. Most of all – and for reasons that should be obvious – I would like tothank the Sakaliou clan Moili moili.

Notes1. The recent attention to indigenous stereotypy complements the now-extensive

literature on Western stereotypes of the primitive other (see, for example,Znamenski 2007).

2. The indigenous religion is sometimes referred to in the local language as aratsabulungan. For a more detailed description of it, see Hammons (2010). Not all ofthe indigenous people in Siberut continue to practice the indigenous religion;most people, in fact, have converted to a denomination of Christianity.

3. My account of the indigenous analysis of the tourist encounter emerged out ofmore than two years of ethnographic research among the Sakaliou clan, withwhom I lived continuously from January 2003 to December 2004. Shorter termfieldwork was conducted in the summers of 2004, 2007, and 2008.

4. The term asli is from Bahasa Indonesia, not the local language. It is most oftentranslated as ‘original’, but in various contexts, it can mean ‘authentic’. In thecontext of the tourist encounter in Siberut, the term is generally used to distinguishbetween ‘traditional’ forest-dwelling people and ‘modern’ village-dwelling people.That authenticity is a reference point for both indigenous people and tourists isonly one of many convergences of seemingly incommensurable worlds apparentin the organization of tourism in Siberut.

5. An interesting contrast to Sakaliou’s use of tourism as a firewall against the state isthe situation among the Wa described by Fiskesjo (2014). In the case of the Wa,

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

Shamanism, Tourism, and Secrecy 17

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

tourism is clearly a technique of state control. A critical difference may be the pres-ence of international tourists.

6. Taussig, of course, is not only the one to have noticed the relation between secrecyand authenticity. See, for example, de Certeau (1984). More generally, many othershave noted the relation between secrecy, exposure, and power (Simmel 1906; Barth1975; Bellman 1984; Canetti 1984).

7. The shaman has always figured in the Western imagination (Znamenski 2007), butrecent work has focused specifically on the allure of the shaman to Western tourists,especially in the mythical homeland of the shaman, Siberia, and Central Asia(Bernstein 2008), and among Native Americans (Bunten 2008) and the indigenouspeople of Central and South America (Feinberg 2006; Davidov 2010). For shaman-ism in Southeast Asia, see Laderman (1991) and Sather (2001).

8. Fletcher (2010) has identified something similar for adventure tourism.9. Because of the money involved, surfing tourism in the Mentawai Islands to the

south of Siberut has been formalized to a much greater extent.10. Unlike the transformation of moran warriors among the Samburu, as described by

Meiu (2014), tourism among Sakaliou has generally resulted in a kind of culturalinvolution.

11. The ambivalence about monetized transactions in the context of the tourist encoun-ter is clearly a two-way street. As MacCarthy (2014) and Causey (2003) demonstrate,both sides are concerned about the ‘corrupting’ influence of money, although forvery different reasons. This is yet another example of how seemingly incommensur-able worlds can converge.

12. The blood is concealed in a bamboo tube.13. The message is said to be made by the soul of the chicken at the moment of its

death. The shaman and most other people learn to read the patterns in the entrails.If the message is bad, they will simply sacrifice another chicken.

ReferencesBakker, Laurens. 1996. Tiele! Turis! The social and Ethnic Impact of Tourism in Siberut

(Mentawai) (Thesis). Leiden University, Leiden.Barth, Fredrik. 1975. Ritual and Knowledge among the Baktaman of New Guinea. New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press.Bashkow, Ira. 2006. The Meaning of Whitemen: Race and Modernity in the Orokaiva Cultural

World. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.Bellman, Beryl L. 1984. The Language of Secrecy: Symbols and Metaphors in Poro Ritual. New

Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.Bernstein, Anya. 2008. Remapping Sacred Landscapes: Shamanic Tourism and Cultural

Production on the Olkhon Island. Sibirica: Journal of Siberian Studies, 7(2):23–46.Bunten, Alexis Celeste. 2008. Sharing Culture or Selling Out? Developing the Commo-

dified Persona in the Heritage Industry. American Ethnologist, 35(3):380–395.Canetti, Elias. 1984. Crowds and Power. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.Causey, Andrew. 2003. Hard Bargaining in Sumatra: Western Travelers and Toba Bataks in

the Marketplace of Souvenirs. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.de Certeau, Michel. 1984. What We Do When We Believe. In On Signs, edited by

Marshall Blonsky pp. 192–202. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

18 christian s. hammons

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

Crisp, John. 1799. An Account of the Inhabitants of the Poggy or Nassau Islands. AsiatickResearches, 6:77–91.

Davidov, Veronica M. 2010. Shamans and Shams: The Discursive Effects of Ethnotour-ism in Ecuador. Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology, 15(2):387–410.

Feinberg, Ben. 2006. ‘I was There’: Competing Indigenous Imaginaries of the Past andthe Future in Oaxaca’s Sierra Mazateca. Journal of Latin American and CaribbeanAnthropology, 11(1):109– 137.

Fiskesjo, Magnus. 2014. Wa Grotesque: Headhunting Theme Parks and the ChineseNostalgia for Primitive Contemporaries. Ethnos. doi: 10.1080/00141844.2014.939100

Fletcher, Robert. 2010. The Emperor’s New Adventure: Public Secrecy and the Paradoxof Adventure Tourism. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 39(1):6–33.

Hammons, Christian S. 2010. Sakaliou: Reciprocity, Mimesis, and the Cultural Economyof Tradition in Siberut, Mentawai Islands, Indonesia. Dissertation. University ofSouthern California.

Hoskins, Janet. 2002. Predatory Voyeurs: Tourists and ‘Tribal Violence’ in RemoteIndonesia. American Ethnologist, 29(4):797–828.

Kirsch, Stuart. 2006. Reverse Anthropology: Indigenous Analysis of Social and EnvironmentalRelations in New Guinea. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Laderman, Carol. 1991. Taming the Wind of Desire: Psychology, Medicine, and Aesthetics inMalay Shamanistic Performance. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Loeb, Edwin. 1929. Shaman and Seer. American Anthropologist, 31:60–84.MacCannell, Dean. 1990. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. Los Angeles:

University of California Press.MacCarthy, Michelle. 2014. ‘Like Playing a Game Where You Don’t Know the Rules’:

Investing Meaning in Intercultural Cash Transactions between Tourists andTrobriand Islanders. Ethnos. doi: 10.1080/00141844.2014.939099

Meiu, George Paul. 2014. ‘Beach-boy Elders’ and ‘Young Big-men’: Subverting theTemporalities of Aging in Kenya’s Ethno-erotic Economies. Ethnos. doi: 10.1080/00141844.2014.938674

Persoon, Gerard A. 2003. The Fascination with Siberut: Visual Image of an Island People.In Framing Indonesian Realities: Essays in Symbolic Anthropology in Honour of ReimarSchefold, edited by Peter J. M. Nas, Gerard A. Persoon and Rivke Jaffe. pp. 315–331.Leiden: KITLV Press.

———. 2004. Religion and Ethnic Identity of Mentawaians on Siberut (West Sumatra). InHinduism in Modern Indonesia: A Minority Religion Between Local, National, and GlobalInterests, edited by Martin Ramstedt. pp. 144– 159. New York, NY: RoutledgeCurzon.

Reeves, Glen. 2001. Local Places; Non-Local Imaginings: Culture, Politics, and Imagination inthe ‘Mentawais’. mentawai.org.

Sather, Clifford. 2001. Seeds of Play, Words of Power: An Ethnographic Study of Iban Shama-nic Chants. Kuching: Tun Jugah Foundation.

Simmel, Georg. 1906. The Sociology of Secrecy and of Secret Societies. American Journalof Sociology, 11:441–498.

Taussig, Michael. 1993. Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses. New York,NY: Routledge.

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

Shamanism, Tourism, and Secrecy 19

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014

———. 1998. Viscerality, Faith, and Skepticism: Another Theory of Magic. In In NearRuins: Cultural Theory at the End of the Century, edited by Nicholas B. Dirks,pp. 257–294. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

———. 1999. Defacement: Public Secrecy and the Labor of the Negative. Stanford: Stanford Uni-versity Press.

Znamenski, Andrei A. 2007. The Beauty of the Primitive: Shamanism and Western Imagin-ation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

ethnos, 2014 (pp. 1–20)

20 christian s. hammons

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

24.8

.140

.189

] at

04:

32 2

4 Se

ptem

ber

2014