ROSOL, Marit / SCHWEIZER, Paul (2012): Ortoloco Zurich – Urban Agriculture as an Economy of...

Transcript of ROSOL, Marit / SCHWEIZER, Paul (2012): Ortoloco Zurich – Urban Agriculture as an Economy of...

ortoloco ZurichUrban agriculture as an economy ofsolidarity

Marit Rosol and Paul Schweizer

This paper asks to what extent urban agriculture projects based on principles of SolidarityEconomics are in a position to develop new economic forms based on solidarity—ratherthan competition—thereby posing an alternative model to neo-liberal capitalism. It seeksto understand how solidarity economies function concretely, what motivations, interestsand goals move people to establish and participate in such initiatives, and what utopiasthey associate with such projects. It focuses on the Swiss gardening cooperative ortoloco,which can be defined as a peri-urban organic farm organised on principles that gobeyond the supply of food to embrace explicit political aims and to realise an alternativeeconomic model. For two years of existence, ortoloco has successfully applied these principleson its economic practice, but also constantly questioned them and developed them further.Extending the diversity of products and activities, and intensifying practical and theoreticalcooperation with similar projects, the activists hope to apply the tested models on an ever-broader range of economic activities and spheres of living together in general. Whilstneo-liberal policies are presented almost worldwide as natural and without alternative,these projects are living proof that other ways of thinking and acting are possible.

Key words: community gardening, cooperatives, solidarity economy, urban agriculture, Zurich

Introduction

In the vicinity of Zurich, Switzerland’smetropolis, the ortoloco cooperative(‘Genossenschaft’) has been developing

a community garden since 2010. Around170 members of the cooperative, togetherwith a professional gardener, are workingan area of land rented from an organicfarmer. In this way, they provide them-selves with fresh organic seasonal veg-etables. Besides the supply of food, afurther explicitly political motive plays acentral role for the commitment of themembers of the cooperative: the specific

goal of the cooperative is the realisation ofan alternative means of economic organis-ation ‘based on productive cooperationinstead of counterproductive competition’(ortoloco, 2010, p. 1). The ortoloco commu-nity garden is thus oriented to the prin-ciples of the ‘Solidarity Economy’.

Projects based on the principles of the Soli-darity Economy are to be found worldwideand in the most varied situations. Oftenthese arise out of desperation and assist theactivists at least in part to relieve their finan-cial burden through self-provisioning.Associated with this economic dimension,there is usually a further dimension: the

ISSN 1360-4813 print/ISSN 1470-3629 online/12/060713–12 # 2012 Taylor & Francishttp://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2012.709370

CITY, VOL. 16, NO. 6, DECEMBER 2012

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Sim

on F

rase

r U

nive

rsity

] at

02:

45 1

4 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

The definite version is available at http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13604813.2012.709370

projects organise themselves on principlesthat strive to distinguish themselves, or expli-citly distance themselves, from the capitalisticway of organising the economy. The activi-ties of these projects can thus be understoodas critique, resistance and the search foralternatives. In times where everywhereincreasingly assertive searches for alternativesare being mounted, it is useful to take a closerlook at such initiatives.

This text should thus be understood as acontribution to the overarching question asto the extent to which projects in SolidarityEconomics, and specifically urban agricultureprojects, are in a position to develop neweconomic forms based on solidarity—ratherthan competition—thereby posing analternative model to neo-liberal capitalism.We focus here on the gardening cooperativeortoloco in order to understand how solidar-ity economies function concretely, whatmotivations, interests and goals movepeople to establish and participate in suchinitiatives and what utopias they associatewith such projects. ortoloco is suited to thisinquiry because the explicit aim of the initiat-ive is to attempt to realise an alternative econ-omic model. This was precisely the point ofdeparture of the initiative, founded as a reac-tion to the financial crisis of 2008. ortoloco isthe result of discussions at the time, seekingalternative forms of economic organisation.The idea of a community garden arose even-tually as an appropriate initiative. In realisingtheir aims, ortoloco follows in no way a pre-ordained rigid model but attempts, rather,to develop the principles as it advances—theory and praxis fertilise one another asthey progress. ortoloco, as an example, isintended to indicate how the implementationof such a solidarity economic garden projectmight look like, what potentials it unfolds,what edge conditions it comes up against,and what problems and contradictions canarise.

We first introduce very briefly the litera-ture of the solidarity economy and urbancommunity gardens before focusing on themodus operandi, goals and principles, and

present more specifically the future plansand initiatives of the project. We end byplacing the initiative in the general debateabout urban community gardens and givesome conclusions that again summarise theirpotential and limits.

Solidarity economies and urbancommunity gardens—a brief introduction

Solidarity economies in neo-liberal times

In the wake of neo-liberal globalisation andthe related global, national and local policies,social disparities have grown in recent yearsboth inside particular societies as well astransnationally and internationally (Altvaterand Mahnkopf, 2007, pp. 221–230, 523;OECD, 2008; ILO, 2008). In the GlobalSouth, under the pressure of national debts,most radical policies implemented in the fra-mework of structural adjustment pro-grammes have often resulted in widespreadpoverty and social polarisation. Also in theNorth, the consequences of privatisation,deregulation and the dismantling of statewelfare programmes are also increasinglynoticeable (see, e.g. Brenner and Theodore,2002, 2005; Harvey, 2005). Especially sincethe onset of the world economic crisis of2008, neo-liberal policies have been increas-ingly challenged, resulting in a debate on acrisis of neo-liberalism and on post-neoliber-alism (Altvater, 2009; Brenner et al., 2010;Craig and Cotterell, 2007; Keil, 2009;Larner and Craig, 2005; Peck et al., 2010).

Whilst it is difficult to set down precise cri-teria to define the concept of SolidarityEconomics, there are nevertheless certaincharacteristics that are often referred to byactors as those which define it:

. it is a form of organisation that is funda-mentally democratic in that it invites par-ticipation on the basis of free and equalcooperation;

. it entails the organisation of activities tosatisfy human needs in the framework of

714 CITY VOL. 16, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Sim

on F

rase

r U

nive

rsity

] at

02:

45 1

4 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

environmentally sustainable use ofresources (see, e.g. Bernardi, 2009;Muller-Plantenberg, 2007; orangotango,2010 as well as diverse websites).1

These characteristics stand in clear and con-scious contradiction to the central principlesof the dominant capitalistic world economicsystem—such as profit maximisation, exploi-tation, hierarchy and competition. It contra-dicts the well-known neo-liberal tenets likethe assumption that the distribution ofresources is most efficient when effectuatedthrough the price-determined rationalcalculus of market-actors as well as freecompetition as the best of all solutions.Neo-liberal globalisation should not,however, be conceived of as a purely econ-omic project. It is, more importantly, asocial process concerned with developingnew social power relations. In practice, weare therefore not dealing with pure theorybut rather with the neo-liberal programmethat aims to reconstitute the social process.

As these principles are no longer to befound in the economic system only but, inthe meantime, have become hegemonic alsoin the social system (see the discussion onthe ‘economisation of the social’ by interalia Brockling et al., 2000), the expressed cri-tique is levelled not only at the economicsystem in the narrow sense but also at thesocial system that has been built up aroundthese principles. Roger Keil suggests thatneo-liberalism be investigated as a social for-mation in that, in contrast to earlier phases inthe application of neo-liberal policies, todaywe can speak of ‘. . . the predominance ofneo-liberal ideology in all areas of sociallife’ (2009, p. 232). Neo-liberal policies areno longer implemented by individual ‘exter-nal’ actors, are not only relevant to particularthemes and are no more limited to the pre-vious dominant social formation of Keyne-sian Fordism. Most problematic is thatpolitical and economic actors in the contextof neo-liberal governance have internalisedit as the basis of their transactions, as beingwithout an alternative. In the self-realisation

of the socialised neo-liberal subject, the prin-ciple of competition takes on a hegemonicrole that is hardly ever questioned (Keil,2009). This rather daunting picture of thepresent makes the existence of projects likeortoloco even more important in our view.

Competition and solidarity

Richter writes of ‘homo concurrens’ astoday’s ruling human self-image that is nota description, but rather ‘as determinant ofactions which truly influences the decisionsof people and hence becomes their reality’(2010, p. 17). At the end of the 19thcentury, the Russian geographer and anar-chist Pjotr Kropotkin criticised the assump-tion that was increasingly spreadingthroughout the sciences and society, of thenotion that the struggle for survival and com-petition between species is a Law of Natureand an essential prerequisite for progressand development (Kropotkin and Landauer,1904, p. O). In contrast to this, in his bookMutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, heposed the principle of solidarity that he heldto be a central foundation for the develop-ment of human and animal life. If we followKropotkin’s suggestion to confront the‘Natural Law’ of competition with the prin-ciple of solidarity, one arrives at socialutopias in which competition as the dominantmedium of organisation is dissolved throughsolidarity (Elsen, 1998, p. 85). Thus, solidar-ity could become the ‘basis of new, righteoussolutions and new institutions’ (p. 98) andusher in a new form of social organisation.

In so far as they attempt to live this socialutopia in a particular framework today, pro-jects of solidarity economy are testing newprinciples in practice, developing thesefurther and are living proof that humancooperation, integration and production onthe basis of other principles than those propa-gated by neo-liberal ideology are possible.Projects of Solidarity Economics existthroughout the world in different forms.Most of these have specialised in particular

ROSOL AND SCHWEIZER: ORTOLOCO ZURICH 715

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Sim

on F

rase

r U

nive

rsity

] at

02:

45 1

4 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

economic niches and operate locally. In thispaper, we are concerned in some detail withthe subject of ‘solidarity urban agriculture’.As the supply of food is one of the mostimportant areas of human existence and pro-duction (see, e.g. Heynen, 2008), it seems tous that the application of solidarity economicprinciples is particularly relevant here.

Urban agriculture and urban communitygardens

City and countryside are often understood ascontradictory, mutually exclusive spheres. Inpractice, urban agriculture is a ‘global, epoch-spanning phenomenon’ (Halder, 2009, p. 58).Whether in the floating gardens of the Azteccapital of Tenochtitlan (today Mexico City),the hanging gardens of Babylon or the allot-ments of modern European cities, agriculturehas always been a part of the urban, evenwhere the division of labour, industrialis-ation, surface sealing, densification andrising land prices have in most cities led tothe forcing out of agricultural uses fromurban areas (pp. 59–60). Particularly for theprovisioning for the urban poor, this,however, remains in many places an impor-tant contribution.

In recent discourse around urban agricul-ture, there is a growing focus on its impor-tance in terms of political action as‘guerrilla-gardening’ (Muller, 2009a; Rey-nolds, 2008), the squatting of public spaces(see, e.g. Rosol, 2010a, 2010b), as anexample of the public/private divide inland-use conflicts and on relations with thelocal state (Knigge, 2009; Rosol, 2012; Smithand DeFilippis, 1999; Smith and Kurtz,2003; Staeheli et al., 2002), and on intercul-tural gardens (Muller, 2002, 2009b). Both insouthern as well as northern countries,initiatives in urban agriculture are no longersimply understood as producers of cheap,organic food but also as political projectsand experimental fields for forms of econ-omic organisation that are alternatives,founded on values fundamentally at odds

with capitalistic, neo-liberal principles. Thisalso characterises ortoloco as described below.

ortoloco—the regional garden cooperative

Since the onset of the financial crisis, the capi-talist mode of economic organisation and theneo-liberal policies which were responsiblefor this are being increasingly criticisedby a wider public. This discussion findsexpression, for instance, in protest camps,occupations of city squares and demon-strations worldwide. Next to loud protestsand silent refusals, in addition many attemptsare being made to develop practical alterna-tives. The garden project ortoloco is also tobe understood as such an attempt. Accordingto their own statement of purpose, ortoloco isestablished against ‘requirements of themarket that are distant from reality’, ‘profit-motivated and growth oriented’, ‘anonymouscompetition’, loss of connection betweenconsumers and the production process,unfair requirements in agriculture and an‘agricultural production scarcely correspond-ing to the actual needs of many consumers’that ‘exploits people and resources’ (ortgolo-co.ch, ‘das ist ortoloco’).2 But how does orto-loco actually function?

Modus operandi of ortoloco

ortoloco is a solidarity economic contractagricultural project3 cultivating a garden inDietikon near Zurich. The administration isin the Albulastrasse in Zurich. ortoloco isregistered as a cooperative. Cooperatives ofmutualism (German: ‘Genossenschaft’) thatwere in the early times of industrial capital-ism the answer to poverty and unemploy-ment have been formative for our currentunderstanding of solidarity economies.Their goal is to ‘recapture autonomouswork and economy’ (Singer, 2001, cited inMuller-Plantenberg, 2007, p. 55). In addition,ortoloco harks back to the ‘old’ instrument ofcooperatives. Membership is open to anyone

716 CITY VOL. 16, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Sim

on F

rase

r U

nive

rsity

] at

02:

45 1

4 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

who feels herself or himself connected to theaims of the cooperative and signs an entrydeclaration and acquires at least one sharecertificate of 250 Swiss francs (CHF), whichwill be paid back when resigning from thecooperative. All the important questions aredecided upon by the general assembly thatis comprised of all cooperative members.The management group, which is responsiblefor the administration and the control group,which oversees the management group, areelected by the general assembly.

ortoloco originated out of the Montags-werkstatt Zurich, founded following the2008 financial crisis to discuss alternativeforms of economic organisation. After beingat length preoccupied with the issue of foodsovereignty and local self-provisioning,there arose the idea to initiate a gardenproject in the course of a gaming exercise(Ursina Eichenberger, founding member of

ortoloco, in Dyttrich, 2011, p. 82). Thereexist some 25 community garden projects inSwitzerland. The role model for ortolocowas primarily Cocagne, a communitygarden project in Geneva existing since1978,4 with which experiences are exchanged.The members of ortoloco found one anotherin the first instance through posters andfliers and through personal contacts. Mostof the members of the association live inZurich, however, via contact with thefarmer, householders from Dietikon alsojoined.

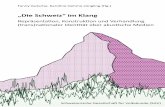

Since March 2010, the project has beenrenting 60 acres (60 × 100 m2) of land fromFondlihof, an organic farm in Dietikon inthe valley of the Limmat river (Figure 1).The approximately 170 members (up from66 founding members) operate this, togetherwith a professional gardener, who looksafter the garden applying her professional

Figure 1 ortoloco garden, administration and vegetable depots in the Zurich area

ROSOL AND SCHWEIZER: ORTOLOCO ZURICH 717

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Sim

on F

rase

r U

nive

rsity

] at

02:

45 1

4 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

know-how. The gardener is paid out of theannual contributions of the recipients of thevegetables produced. Only organic seeds areused. About 40 indigenous plant varietiesare grown that do not require energy-inten-sive production methods. Planting and har-vesting follow the annual cycle and steps aretaken to avoid over-production. The har-vested vegetables are put in bags weekly—small for two persons, larger for four andfive persons—and delivered to depots placedin various neighbourhoods of Zurich, so theend-users can pick them up. In winter, bagsmay not be full or may fail altogether, neces-sitating consumers to look elsewhere for theirprovisions. As there is a lack of storage space,potatoes, for example, are bought in from aneighbouring organic farmer.

To accomplish the necessary work in thegarden, washing and packing the harvest,transporting it into the city, administrativetasks, etc., the work is distributed amongstthe members of the association. In additionto the annual contribution (1100 CHF for asmall vegetable subscription, 2200 CHF fora large) a minimum engagement of four halfdays per year is required of all memberswho receive produce. Further work may becontributed voluntarily. The obligatory timeof members is not sufficient to accomplishall the important work. However, as manyassociation members are willing to put theirfree time into ortoloco, there has so far beenno problem accomplishing all the necessarywork.

Nevertheless, there have been situations inwhich the distribution of work was noteasy. Therefore, starting in 2012 associationmembers must take responsibility for atleast two areas of work, which they maychoose. Of course, they may also involvethemselves in other areas of work. Throughthis change, responsibility for particularareas is clarified and thus communication issimplified. In addition, the members areengaged in ‘action days’, festivals, work andproject groups, in undertaking special tasksand new initiatives to extend the project.Thus, any member can at any time initiate

new ideas and activities to help develop orto-loco. Recent extension projects include thecreation of new berry stands and the cultur-ing of mushrooms. In this way, the diversityof the weekly vegetable bags can be increased(ortoloco, 2011). The project group brotolocothat is extending the activity to the pro-duction and supply of bread has, since 2012,been constituted as a separate association(brotoloco.ch).5

Principles and aims

The expressed aim of ortoloco is an environ-ment-friendly resource-sparing not-for-profit-oriented agriculture project thatsupplies produce to consumers according toneeds and that places members in directrelationship with the products and their pro-duction. Through fair conditions andvoluntary engagement, it is intended todemonstrate an alternative model to thedominant anonymous competitive economy.In the statutes of the association, these prin-ciples are set out in three guiding principlesas follows:

‘We will treat nature and the environmentwith respect and sustainably. The earth, plantsand animals are not machines that may berevved up with impunity. In this sense we arean alternative to industrialised agriculturewith its faceless expansive gigantic operations.

Agriculture for us is an activity ofstewardship not a business. We produceaccording to the seasons and force nouniformity of output. That is to say that weharvest what appears, not what is financiallyprofitable. We recover an important area oflife from the spheres of speculation and profitand through this work against the dominanteconomic logic with its growth urge. Wecreate an alternative form of economicorganisation based on productive cooperationinstead of counterproductive competition. Inthis way agricultural smallholdings may bepreserved.

Today’s distanced relationship betweenproducers and consumers will be brokendown. Sustenance should happen where food

718 CITY VOL. 16, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Sim

on F

rase

r U

nive

rsity

] at

02:

45 1

4 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

is produced with only minimal importation.The function of middleman will be abolished.Through this direct, personal exchangebetween producers and consumers, theproject presents a sustainable model for thefuture. The consumers are motivated andinterested to appraise themselves concerningthe creation and characteristics of theirsustenance. They wish to learn and regularlyspend interesting and joyful days in the openin the fields. Through this they will improvetheir quality of life.’ (ortoloco, 2010, p. 1,translation and emphases by the authors)

These values are clearly discernible in theorganisation and activities of ortoloco. In dis-cussion with the association members, itbecame clear that an intensive and constantengagement with the values of the solidarityeconomy are realised through the project.The central motivation to participate in suchprojects is not simply access to high-qualityvegetables and love of gardening but alsothe will, based on new economic forms, totest and create other values.

Future plans

Interest in the ortoloco project and its veg-etable subscriptions is very high. In order tonot have more subscriptions than the gardencan supply, new association membership hasto be regulated via a waiting list. An extensionof the area being farmed is planned in order toextend the number of members with access toproduce. In order to work the additionalland, a second professional gardener hasbeen employed since March 2012. However,the activists contend that a maximum sizeshould not be exceeded in order to preservethe familiar character of the initiative. Asone of the founders of ortoloco worries thatwith a larger group in which everyone nolonger knows everyone else could result in alarger administrative burden and a loss ofthe quality of democratic decision-making.With the relatively small group in whichpeople know one another, relations with theproject are direct and in addition are more

fun (Tex, personal communication, 2 February2012).

The idea to include agriculture explicitlyinto urban planning and through this toensure in the longer term a regional supplyof vegetables for whole neighbourhoods isalso being discussed. In his book NeustartSchweiz (A New Start for Switzerland), theZurich author P.M. propagates the reorganis-ation of society into neighbourhood unitsthat supply themselves with vegetablesthrough contracts with neighbouring farmersand eventually the participation of residents.The book, which shows connections to the‘Transition Towns’ movement’,6 was dis-cussed in the context of an event on foodsovereignty of a local self-provisioning organ-ised by the Montagswerkstatt Zurich (Dyt-trich, 2011, p. 82) and is declared on theortoloco website to be an ‘inspiring socialvision’ (ortoloco.ch, ‘Links’). In this sense,ortoloco is planning for the future a focus onthe target group ‘community housing andsettlement’. Besides the small and large veg-etable subscriptions for small and large house-holds, house and neighbourhood subscriptionswith offers of vegetable boxes for 10, 20 oreven 50 houses will be made. Whether therewill be a demand for these and if this ideacan be implemented in practice is yet to beseen. Tex sees it as important to make theoffer first in order to see what the chancesare of them being recognised (personal com-munication, 30 November 2011).

Furthermore, the initiative wishes toextend the application of solidarityeconomy principles where possible to allimportant sectors of the economy. Thus, theproject groups that extend the range of pro-duction offer association members the possi-bility of satisfying an ever-greater proportionof their needs. Tasks for the future could be,for instance, a cheese dairy, pasta productionand a kindergarten (Tex, visit at ortoloco, 23July 2011). It would also be desirable, accord-ing to Tex, to develop cooperation with otherassociations independent of ortoloco that areactive in other economic areas but are organ-ised on similar principles. He is thinking, for

ROSOL AND SCHWEIZER: ORTOLOCO ZURICH 719

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Sim

on F

rase

r U

nive

rsity

] at

02:

45 1

4 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

instance, of textile or energy-productionassociations. A step in this direction alreadytaken is the establishment of the already men-tioned brotoloco out of the existing ortolocoproject group.

The place of ortoloco in the debate abouturban community gardens

Much of the academic work on urban com-munity gardens is concerned with gardensin poor neighbourhoods in large Latin Amer-ican and African cities (see, e.g. Haidle andArndt, 2007; Halder, 2009; Mougeot, 2005)or informal uses of land in connection withstructural adjustment, targeted speculationor economically encouraged vacant land inmajor North American and European cities(see, e.g. Meyer-Renschhausen, 2004; Rosol,2005; Schmelzkopf, 2002).

ortoloco shows in the context of its historyof creation and the specific situation ofZurich certain differences but also common-alities with these other projects. ortoloco isnot a project created out of financial distress.Financial aspects play only a minor role in thedecision to participate in the project. It isneither created or uses land informally. Theproject decided on an appropriate legal formof a cooperative that has a long and wide-spread tradition in Switzerland and the landis officially leased from a farmer. Further-more, we find ortoloco outside Zurich in theso far hardly urbanised Limmat valley. Thisis a consequence of constantly rising landprices in Zurich where hardly any vacantland or land at low rental prices exists thatmight come into question to accommodatecommunity gardens. Nevertheless, theproject can still be considered as urban agri-culture because it originated in projectslocated in Zurich, is supported by residentsof Zurich and networked with Zurich-basedinstitutions and projects whose structureutilises, for instance, communicationsand distribution of vegetable bags andexplicitly serves the urban population withminimal transport (the distance to the

city centre is just 10 kilometres as thecrow flies).

ortoloco possesses commonalities with‘community-supported agriculture’ (CSA)(Brown and Miller, 2008; Schnell, 2007).Like those, ortoloco is supported by depend-able takers of the produce produced near thecity centre, who pay a fixed amount at thestart of the year and who thus share in theenterprise risks—for instance, in the case ofpoor harvests (see the above note on contrac-tual agriculture). This format makes possibleproduction close to the city of high-qualityorganic produce by small farmers who other-wise would hardly be able to face the steepcompetition. In contrast to the usual formsof CSA, however, in the case of ortoloco therecipients of the produce are also the produ-cers and really only pay the productioncosts of the vegetables produced. Further-more, they reduce the price through theirown activity. Thus—it is hoped—vegetables,in comparison with the CSA model, willbecome affordable to broader levels of thepopulation.

In sum, ortoloco can be defined as aperi-urban organic farm organised on thebasis of Solidarity Economics that extendsbeyond the supply of food to embrace expli-cit political aims.

Conclusions and outlook

In the course of our visit to ortoloco in July2011 we were impressed by the high spiritsin the garden and, indeed, on the whole Fon-dlihof. A couple of association members wereworking in the fields, others were having abreak and chatting over a cup of own-pro-duced apple juice, children playing in thefarmyard, a large dog allowed itself to bestroked; also the owner of the Fondlihofpassed by. At the same time, we were observ-ing a project, which has proved its successover two years, supplying 300 consumerswith vegetables. The considerable amount ofwork required has always been undertakennot on the basis of force but because of

720 CITY VOL. 16, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Sim

on F

rase

r U

nive

rsity

] at

02:

45 1

4 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

the pleasure in the matter or at least thewill to continue the project. In this sense,ortoloco is living proof that economiesbased on free cooperation and solidarity arepossible.

The implementation of the project surelyworks because of the ongoing collectivereflection on their values and their realisationin practice. This occurs both in the internalparticipatory processes of the organisationand the exchange with befriended projectsand activities. Beyond the theoreticalexchange, there is also the shared use of infra-structure (such as vegetable depots and adver-tising) or mutual exchange of complementaryproducts (housing associations, befriendedorganic farmers, brotoloco). In this way, thenotion of cooperation is applied wellbeyond the boundaries of ortoloco.

Through resource-conserving productionin direct proximity to the users, urban agri-culture can have positive ecological effects.Participatory projects such as ortolocoraise at the same time the quality of lifeof the participants by connecting workand leisure and making available high-quality, healthy organic and tasty productswhich, beyond their use value, represent akind of ideal. In this way, the project pro-motes ‘the good life’ beyond mass con-sumption that is no longer based onmaterial wealth.

In that projects such as ortoloco applyalternative principles to economic life,develop these further, discard things thatdon’t work and adopt others that do, in theprocess, they continually stretch the bordersof the possible. Whilst neo-liberal policiesare presented almost worldwide as naturaland without alternative, these projects areliving proof that other ways of thinking andacting are possible. Cooperation with similarprojects and attempts to apply the testedmodels on an ever-broader range of economicactivities and spheres of living together ingeneral, encourage one to believe in the poss-ible major changes carried out by the accumu-lation of many small, locally operatinginitiatives (Sassen, 2000, p. 26).

On the other hand, it would be naive tobelieve that the ortoloco model might begreatly expanded. And of course, it is notpossible for ortoloco to carry out its activitiesentirely outside the complexities of the globaleconomy or the capitalistic pressures thatdistort its activities. It should furthermorebe remembered that also neo-liberal thinkerslike the German ordo-liberals propagated theindividual allotment gardens and voluntarymutual assistance as preventing ‘proletariani-sation’ and state-dependency (Ropke, 2002[1942]). Substitution of income through allot-ment gardening has also been identified byEngels, in his famous critique of Proudhonconcerning the housing question, as a possi-bility for capitalists to reduce wages further(Engels, 1974 [1872]). Thus, self-provisioningof city dwellers through farming is not freefrom contradictions.

Furthermore and more practical, thereremains the unsolved problem that member-ship of ortoloco and access to vegetable sub-scriptions are dependent on the payment ofan annual fee. These fees are equally highfor all members independent of their financialsituation. It is to be feared that some peoplewill not be able to afford the ‘luxury’ of mem-bership of the project. According to Tex (visitto ortoloco on 23 February 2011), it is there-fore under consideration to make the size ofthe fee dependent on level of income. More-over, the association members of ortolococannot feed themselves entirely from whatthey produce but are dependent on incomesfrom other activities with which to buyother products. And finally, only a certainrange of vegetables are produced and inwinter produce has to be purchasedelsewhere.

The question thus arises as to the useful-ness of such a project if, in fact, it cannotexist entirely outside the capitalistic systemand guarantee the entire provisions of itsmembers of the association, all year round?Here we can only answer that the greatpotential of projects like ortoloco lies intheir characteristics as experiments in neweconomic practices and should be seen as

ROSOL AND SCHWEIZER: ORTOLOCO ZURICH 721

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Sim

on F

rase

r U

nive

rsity

] at

02:

45 1

4 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

small steps in a desired direction. It is perhapsa useful insight that certain plants do notgrow or grow only in certain seasons inCentral Europe and that it is still possible tobe happy with what does grow, that we canlearn from projects such as ortoloco. Fromthis we can deduce that whilst such projectscannot extract themselves entirely from thecapitalist world and the complexities of theglobal economy, we can nevertheless be opti-mistic. To see that people are prepared tocommit themselves voluntarily and withstrong political beliefs and that such aproject is economically feasible as well asproviding ecological benefits through region-ally, seasonally and organically grownproduce demonstrates that ‘another worldcould be grown’.7

Acknowledgements

We thank the activists of ortoloco for sharingtheir experiences with us. We are very grate-ful to Adrian Atkinson for his constructivecomments on earlier versions of this paperand for his generous help with translationissues. Furthermore, we thank Elke Albanfor her cartographic contribution to thispaper.

Notes

1 For instance, www.solidarische-oekonomie.de,www.vivirbien.mediavirus.org (last accessed 13March 2012).

2 In the framework of a field trip of the Department ofHuman Geography of the University of Frankfurt, inthe summer of 2011, we had the opportunity to visitthe garden in Dietikon near Zurich together withsome of the members of the association. We wereable since then, via the contact established with Tex,one of the founder members and member also of themanagement group, to follow developments and theplanning process of ortoloco.

3 So-called ‘contract farming’ (‘Vertragswirtschaft’)consists of a contractually regulated relationshipbetween farmers and recipients or, on the ortolococase, lessees. In this way, fairer conditions are madepossible in farming (ortoloco.ch, ‘Portrait’). Above

all, in the west of Switzerland the regional contractagriculture (agriculture contractuelle de proximite) isvery widespread (Dyttrich, 2011, pp. 79–80) (seealso the section on CSA).

4 http://www.cocagne.ch/page-daccueil/ (lastaccessed 24 November 2011).

5 brotoloco refers to bread-baking (bread in German:‘Brot’). See also http://www.brotoloco.ch/ (lastaccessed 2 February 2012).

6 See http://www.transitionnetwork.org/ and http://transitions-initiativen.de/ (last accessed 9 February2012).

7 Thus the title of the web page of Ella von der Haide.See http://eine-andere-welt-ist–pflanzbar.net/ (lastaccessed 2 February 2012).

References

Altvater, E. (2009) ‘Postneoliberalism or postcapitalism?The failure of neoliberalism in the financial marketcrisis’, Development Dialogue 51, pp. 73–86.

Altvater, E. and Mahnkopf, B. (2007) Grenzen der Glo-balisierung. Munster: Westfalisches Dampfboot.

Bernardi, J. (2009) Solidarische Okonomie. Selbstver-waltung und Demokratie in Brasilien und Deutsch-land. Kassel: Kassel University Press.

Brenner, N. and Theodore, N. (2002) ‘Cities and thegeographies of “actually existing neoliberalism”’,Antipode 34(3), pp. 349–379.

Brenner, N. and Theodore, N. (2005) ‘Neoliberalism andthe urban condition’, City 9(1), pp. 101–107.

Brenner, N., Peck, J. and Theodore, N. (2010) ‘Afterneoliberalization?’, Globalizations 7(3),pp. 327–345.

Brockling, U., Krasmann, S. and Lemke, T. eds (2000)Gouvernementalitat der Gegenwart. Studien zurOkonomisierung des Sozialen. Frankfurt/M:Suhrkamp.

Brown, C. and Miller, S. (2008) ‘The impacts of localmarkets: a review of research on farmers markets andcommunity supported agriculture (CSA)’, AmericanJournal of Agricultural Economics 90(5),pp. 1298–1302.

Craig, D. and Cotterell, G. (2007) ‘Periodisingneoliberalism?’, Policy & Politics 35(3),pp. 497–514.

Dyttrich, B. (2011) ‘Neue Garten gegen den Kapitalismus’,in Denknetz (ed.) Jahrbuch 2011: GesellschaftlicheProduktion jenseits der Warenform—Analysen undImpulse zur Politik. Zurich, Edition 8.

Elsen, S. (1998) Gemeinwesenokonomie—Eine Antwortauf Arbeitslosigkeit, Armut und soziale Ausgren-zung? Soziale Arbeit, Gemeinwesenarbeit undGemeinwesenokonomie im Zeitalter der Globalisier-ung. Neuwied: Luchterhand.

722 CITY VOL. 16, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Sim

on F

rase

r U

nive

rsity

] at

02:

45 1

4 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

Engels., F. (1974 [1872]) Zur Wohnungsfrage. Frankfurt/M: Verlag Marxistische Blatter.

Haidle, I. and Arndt, C. (2007) Urbane Garten in BuenosAires, ISR Diskussionsbeitrage Heft 59. Berlin: Tech-nische Universitat Berlin.

Halder, S. (2009) ‘Garten der Gerechtigkeit? Die politischeOkologie der Favelagarten von Rio de Janeiro’,Unpublished Diplomarbeit, Eberhard-Karls-Universi-tat Tubingen.

Harvey, D. (2005) A Brief History of Neoliberalism.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heynen, N. (2008) ‘Justice of eating in the city: the politicalecology of urban hunger’, in N. Heynen, M. Kaikaand E. Swyngedouw (eds) In the Nature of Cities.Urban Political Ecology and the Politics of UrbanMetabolism. London: Routledge.

ILO (2008) Income Inequalities in the Age of FinancialGlobalization, World of Work Report 2008 (Inter-national Labour Organization). Geneva: Inter-national Institute for Labour Studies.

Keil, R. (2009) ‘The urban politics of roll-with-it neoliber-alization’, City 13(2), pp. 230–245.

Knigge, L. (2009) ‘Intersections between public and pri-vate: community gardens, community service andgeographies of care in the US city of Buffalo, NY’,Geographica Helvetica 64(1), pp. 45–52.

Kropotkin, P. and Landauer, G. (1904) Gegenseitige Hilfein der Entwicklung. Leipzig: Thomas.

Larner, W. and Craig, D. (2005) ‘After neoliberalism?Community activism and local partnerships inAotearoa New Zealand’, Antipode 37(3), pp. 402–424.

Meyer-Renschhausen, E. (2004) Unter dem Mull derAcker. Community Gardens in New York City.Konigstein/Taunus: Ulrike Helmer Verlag.

Mougeot, L., ed. (2005) Agropolis. The Social, Political,and Environmental Dimension of Urban Agriculture.Ottawa: International Development Research Centre.

Muller, C. (2002) Wurzeln schlagen in der Fremde—DieInternationalen Garten und ihre Bedeutung fur Inte-grationsprozesse. Munchen: okom Verlag.

Muller, C. (2009a) ‘Die neuen Garten in der Stadt’, in T.Kaestle (ed.) Mind the Park. Planungsraume. Nutzer-sichten. Kunstvorfalle (Oldenburg: Fruehwerk Verlag.

Muller, C. (2009b) ‘Zur Bedeutung von InterkulturellenGarten fur eine nachhaltige Stadtentwicklung’, in D.Gstach, H. Hubenthal and M. Spitthover (eds) Gartenals Alltagskultur im internationalen Vergleich(Arbeitsberichte des Fachbereichs Architektur Stadt-planung Landschaftsplanung, 169).

Muller-Plantenberg, C. (2007) ‘Solidarische Okonomieund regionale Entwicklung’, in C. Muller-Plantenberg(ed.) Solidarische Okonomie in Europa. Betriebe undregionale Entwicklung. Internationale Sommerschulein Imshausen. Kassel: Kassel University Press.

OECD (2008) Growing Unequal? Income Distribution andPoverty in OECD Countries. Paris: Organisation forEconomic Cooperation and Development.

orangotango, k., ed. (2010) Solidarische Raume & koo-perative Perspektiven. Praxis und Theorie in Lateina-merika und Europa. Neu-Ulm: AG-SPAK-Bucher.

ortoloco (2010) ‘Statuten der Genossenschaft ortoloco.Die regionale Gartenkooperative’, http://www.ortoloco.ch/docs/Statuten_7.3.2010.pdf (accessed21 March 2012).

ortoloco (2011) ‘Projektfonds. Infoblatt’, http://www.ortoloco.ch/docs/Infoblatt_Projektfonds_2011.pdf(accessed 21 March 2012).

Peck, J., Theodore, N. and Brenner, N. (2010) ‘Postneoli-beralism and its malcontents’, Antipode 41(s1),pp. 94–116.

Reynolds, R. (2008) On Guerrilla Gardening: A Hand-book for Gardening without Boundaries. London:Bloomsbury.

Richter, T. (2010) ‘Die Prinzipien Konkurrenz und Koo-peration’, in k. orangotango (ed.) SolidarischeRaume & kooperative Perspektiven. Praxis und The-orie in Lateinamerika und Europa. Neu-Ulm: AG-SPAK-Bucher.

Ropke, W. 2002 (1942.) Die Gesellschaftskrise derGegenwart [translated as: The Social Crisis of OurTime]. Dusseldorf: Verlag Wirtschaft und Finanzen.

Rosol, M. (2005) ‘Community gardens—a potential forstagnating and shrinking cities? Examples from Ber-lin’, Die Erde 132(2), pp. 23–36.

Rosol, M. (2010a) ‘Gemeinschaftsgarten—PolitischeKonflikte um die Nutzung innerstadtischer Raume’, inB. Reimers (ed.) Garten und Politik. Munchen:Oekom.

Rosol, M. (2010b) ‘Public participation in post-Fordisturban green space governance: the case of commu-nity gardens in Berlin’, International Journal of Urbanand Regional Research 34(3), pp. 548–563.

Rosol, M. (2012) ‘Community volunteering as neoliberalstrategy? Green space production in Berlin’, Antipode44(1), pp. 239–257.

Sassen, S. (2000) ‘Ausgrabungen in der “Global City”’, inA. Scharenberg (ed.) Berlin: Global City oder Kon-kursmasse?. Berlin: Dietz.

Schmelzkopf, K. (2002) ‘Incommensurability, land use,and the right to space: community gardens inNew York City’, Urban Geography 23(4), pp. 323–343.

Schnell, S.M. (2007) ‘Food with a farmer’s face: commu-nity-supported agriculture in the United States’,Geographical Review 97(4), pp. 550–564.

Singer, P. (2001) ‘Solidarische Okonomie in Brasilienheute: eine vorlaufige Bilanz’, in K. Gabbert et al.(eds) Jahrbuch Lateinamerika 25. Munster.

Smith, C. and Kurtz, H. (2003) ‘Community gardens andpolitics of scale in New York City’, GeographicalReview 93(2), pp. 193–212.

Smith, N. and DeFilippis, J. (1999) ‘The reassertion ofeconomics: 1990s gentrification in the Lower EastSide’, International Journal of Urban and RegionalResearch 23(4), pp. 638–653.

ROSOL AND SCHWEIZER: ORTOLOCO ZURICH 723

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Sim

on F

rase

r U

nive

rsity

] at

02:

45 1

4 Ja

nuar

y 20

13

Staeheli, L., Mitchell, D. and Gibson, K. (2002) ‘Conflict-ing rights to the city in New York’s community gar-dens’, GeoJournal 58(2–3), pp. 197–205.

Marit Rosol works as lecturer and researcherat the Department of Human Geography atGoethe-Universitat Frankfurt am Main. Shehas been working on the topic of communitygardening for almost 10 years now. She fin-ished her PhD on community gardens in

Berlin in 2006. Email: [email protected]

Paul Schweizer studies geography at theDepartment of Human Geography atGoethe-Universitat Frankfurt am Main andbecame interested in urban agriculturethrough his personal passion for gardening.Email: [email protected]

724 CITY VOL. 16, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Sim

on F

rase

r U

nive

rsity

] at

02:

45 1

4 Ja

nuar

y 20

13