Rock around the Grave. Jim Morrison's Grave at Père-Lachaise

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Rock around the Grave. Jim Morrison's Grave at Père-Lachaise

Rock around the Grave. Jim Morrison’s Grave at Père-LachaiseMichelangelo GiampaoliIn Ethnologie française Volume 42, Issue 3, 2012, pages 519 to 529Translated from the French by Cadenza Academic Translations

ISSN 0046-2616ISBN 9782130593522DOI 10.3917/ethn.123.0519

Available online at:--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------https://www.cairn-int.info/journal-ethnologie-francaise-2012-3-page-519.htm--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------How to cite this article:

Michelangelo Giampaoli, «Rock around the Grave. Jim Morrison’s Grave at Père-Lachaise», Ethnologie française 2012/3 (Vol. 42) ,

p. 519-529

Electronic distribution by Cairn on behalf of P.U.F..

© P.U.F.. All rights reserved for all countries.

Reproducing this article (including by photocopying) is only authorized in accordance with the general terms and conditions of use forthe website, or with the general terms and conditions of the license held by your institution, where applicable. Any other reproduction,in full or in part, or storage in a database, in any form and by any means whatsoever is strictly prohibited without the prior written

consent of the publisher, except where permitted under French law.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

© P

.U.F

. | D

ownl

oade

d on

06/

07/2

022

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

(IP

: 65.

21.2

29.8

4)©

P.U

.F. | D

ownloaded on 06/07/2022 from

ww

w.cairn-int.info (IP

: 65.21.229.84)

Ethnologie française, XLII, 2012, 3

Rock Around the Grave.Jim Morrison’s Grave at Père-Lachaise

Michelangelo GiampaoliDipartimento Uomo & Territorio, Università degli Studi di Perugia

ABSTRACT

Forty years on from the death of Jim Morrison, his grave at the cemetery of Père-Lachaise in Paris continues to be visited by thousands of people every day, many of whom practice unusual and characteristic acts of devotion. A place of worship for his fans, a destination for tourists from all over the world, an area where alcohol and drugs are used, the presence of the tomb has just as profound an effect on the daily life of Père-Lachaise as it does on the collective imaginary.Keywords: cemetery, tourism, pilgrimage, rock and roll, Paris

Michelangelo GiampaoliDipartimento Uomo & Territorio, Università degli Studi di PerugiaVia Guido Pompili, 2106122 [email protected]

Today, for countless people scattered across the globe, the Père-Lachaise cemetery is considered the “Jim Morrison cemetery.” In other words, the place that has been his “home” since July 1971. Indeed, although Jim Morrison in fact only spent the last six months of his life living in Paris, he has, nevertheless, become perhaps the most famous of its adopted children - having a profound effect on the image and daily life of Père-Lachaise and the surrounding area.

However, the necropolis—opened in May 1804 on orders from Napoleon—houses a rich historical and artistic heritage of nineteenth-century chapels, stained glass windows, busts, and sculptures made from stone and bronze. It is Paris’s largest public green space with hundreds of species of flora and fauna, making it a valu-able reserve of urban biodiversity. Last, but by no means least, it is home to a number of illustrious individuals ranging from Molière and La Fontaine to Oscar Wilde, Frédéric Chopin, Honoré de Balzac, Jacques-Louis David, André Masséna, Édith Piaf, Amedeo Modigliani, and many more. Père-Lachaise has probably the highest concentration of famous names per square meter of any cemetery in the world. Jim Morrison is thus by no means the only celebrity whose mortal remains reside

within its walls. Like him, they form part of the site’s charm and appeal. However, according to estimates from security officers, conservation office employees, regulars, and cemetery guides, approximately 80% of the cemetery’s estimated two million annual visitors are primarily drawn to the cemetery by Jim Morrison’s grave.

In this article, I am aiming to demonstrate why a cemetery which has spent more than two centuries welcoming hundreds of well-known figures who have shaped the history of humanity (from history to music, and from art to philosophy, etc.) is now known and visited primarily as a result of the presence of the grave of Jim Morrison, poet and lead singer of the band The Doors, between 1965 and 1971. I will attempt to highlight various specific, sometimes unique activ-ities that take place within Père-Lachaise and define those involved in such activities. These forms of devo-tion originate from the cultural and media dynamics which has transformed Jim into an international and trans-generational star over the last forty years and thus made the cemetery where he rests one of Paris’s most popular attractions. By their visibility, these forms of devotion help to communicate the reputation of both

© P

.U.F

. | D

ownl

oade

d on

06/

07/2

022

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

(IP

: 65.

21.2

29.8

4)©

P.U

.F. | D

ownloaded on 06/07/2022 from

ww

w.cairn-int.info (IP

: 65.21.229.84)

Michelangelo GiampaoliII

Ethnologie française, XLII, 2012, 3

Jim Morrison himself, and indirectly, that of Père-Lachaise.

A true icon, Jim Morrison’s grave has become a form of outdoor sanctuary where fans can pay tribute, in front of thousands of people. The great necropolis of eastern Paris has become a stage where they contribute to the process of Jim’s “deification,” a process which began during his lifetime and has been continuously maintained by the media. Père-Lachaise thus remains a favorite destination for funeral tourism, which often takes on the characteristics of a modern pilgrimage to the rhythm of rock and roll.

The Stuff of Heroes

Born in Florida in 1943 and found dead in the bath of his apartment on rue Beautreillis in Paris’s 4th arron-dissement on July 3, 1971, Jim Morrison was in 1965 a co-founder of the band The Doors, whose music and magnificent lyrics were a major part of the American rock and roll scene of the time. However, Jim Morrison was more than just a rocker in the 1960s and 1970s, even if this is the main image that he left behind. He was a true poet who only achieved recognition at a late stage and who did not receive the acclaim he really deserved, overwhelmed by the oppressive and captivating icon of the rocker par excellence. Fascinated by the spiritual world of the native peoples of North America, he also considered himself to be a form of shaman; in a manner of speaking, The Doors concerts were almost ceremonies.

Provocative and transgressive, using the influence of alcohol and narcotics to “open the doors of per-ception,” Morrison encouraged his fans to undertake increasingly excessive behavior and rebel against social constraints. Everyone would burst into frenzied dances led by “The Lizard King,” as Jim liked to be known. Audiences at shows often felt as though they were par-ticipating in a true “shamanic rock ritual” (Hopkins and Sugerman 1980, 133). Ultimately, his interest in the poètes maudits and his desire to devote himself to his literary interests prompted Jim Morrison to travel to Paris in March 1971. He explored the places that had always fascinated him: the Hôtel de Lauzun on Île Saint-Louis, the great halls of the Louvre, the Marais, and even Père-Lachaise. Oblivious of how inextricably linked he would soon be with this great necropolis, he

was very drawn to this huge park where he could lose himself among the graves and the trees…

On July 7, 1971, four days after his death at barely 27 years of age, under circumstances which are still the subject of much debate and conjecture, James Douglas Morrison was buried in Division 6 of the cemetery. Only five people were present at the burial, including his girlfriend Pamela Courson and her friend Agnès Varda, the filmmaker. Jim’s death transformed and boosted the evocative power of both his image and his position in the collective imagination. During this historic and cultural period that developed in America following the war and which reached its peak during the late 1960s and 1970s, the images of modern gods were born. The legends, narratives, and protagonists of these years remain present and prominent to this day, as can also be seen in the phenomena of popular devotion at the graves of Jim and other well-known figures.

Rock has thus taken on the form of a religion, which over time has found its own gods to be hon-ored. To quote Gabriel Segré, the author of a work analyzing the worship of Elvis Presley, it is not unu-sual to find people who “ascribe rock and roll with the status of a polytheistic religion where Elvis [and similarly Morrison—ed.] represents one of the major deities” (Segré 2003, 56).

Exactly twenty years before Segré’s analysis, Marie-Christine Pouchelle (1983) had already analyzed the shift in some forms of worship of music and enter-tainment stars towards the sphere of the religious, also highlighting the importance of not underestimating their emotional and social value. “Can we really speak of religious phenomena in terms of fans’ worship of their idols? While the twinkling world of show busi-ness may seem more profane than any other, its expres-sions are often spontaneously described by journalists using religious vocabulary. Is this simply the hyperbole of hacks with sensationalist tendencies? Listening to what is said by the ‘worshippers’ themselves, we are led to question whether we should not pay more serious attention than has previously been the case to these metaphorical references to religion” (Pouchelle 1983, 277–288).

In view of this, locations that have played an impor-tant role in the lives of these “divinities” or that have been particularly marked by their presence often become reference points for the various communities of worshippers. Père-Lachaise can therefore be viewed as one of the most significant “sacred sites” of rock and

© P

.U.F

. | D

ownl

oade

d on

06/

07/2

022

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

(IP

: 65.

21.2

29.8

4)©

P.U

.F. | D

ownloaded on 06/07/2022 from

ww

w.cairn-int.info (IP

: 65.21.229.84)

IIIRock Around the Grave. Jim Morrison’s Grave at Père-Lachaise

Ethnologie française, XLII, 2012, 3

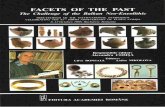

Jim’s grave in Division 6 of Père-Lachaise (photo by Hugo, 2003).

© P

.U.F

. | D

ownl

oade

d on

06/

07/2

022

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

(IP

: 65.

21.2

29.8

4)©

P.U

.F. | D

ownloaded on 06/07/2022 from

ww

w.cairn-int.info (IP

: 65.21.229.84)

Michelangelo GiampaoliIV

Ethnologie française, XLII, 2012, 3

roll, alongside Abbey Road in the UK or Graceland in the United States. When we say Père-Lachaise here, it should be understood to mean more specifically Jim’s grave.

The State of a Tomb

However, visitors to Morrison’s grave—hidden by the far more impressive chapels surrounding it—are struck by the inverse relationship between the size, scale, and shape of the burial place and the quantity of flowers and objects covering it. The monument con-sists of a simple stone border about twenty centim-eters high and thirty centimeters thick, serving as a frame (approximately 1.3 m by 2 m) for the central area of bare ground. Next to one of the short sides of the rectangle stands the grave marker, an almost cubic block of stone approximately 70 cm high, which takes up around one third of the burial area. At the center of the grave marker a metal plaque, faded with time, bears the name of the poet and singer (James Douglas Morrison), the years of his birth and death, and the famous ancient Greek inscription kata ton daimona eautou (which can be translated as “true to his own spirit” or “true to his own demon,” thus leaving it open to multiple interpretations).

The grave as it appears today is different from its original form, having undergone various changes over the years. At the time of the death of the lead singer of The Doors, the area was not demarcated by a stone section. Instead, a long row of shells surrounded the area of ground beneath which the coffin now lays, with a vase of flowers and a small ground plaque bearing the singer’s name and surname. The shells gradually disap-peared, together with other parts of the grave, stolen by fans who wanted to return home with a piece of their idol’s burial place to keep as a relic. From 1981 onwards, the grave marker was topped with a bust cre-ated by Croatian artist Mladen Mikulin. In 1988 this sculpture was also stolen, despite being damaged and covered in graffiti. The grave that can be seen today was rebuilt by the singer’s family at the end of 1990, and has a sober appearance.

Contrasting with the simplicity of the grave, hun-dreds of tributes are left every day by the constant stream of visitors. Some leave simple signs of their presence, others true ex-votos brought long distances to be placed on the site: the grave is covered with

objects of all shapes and sizes, often entirely buried with gifts and piled up around the edges. Plants and flowers (with red roses the most prominent), together with candles and small nightlights are accompanied by much more bizarre items, in complete contrast to the other graves in the cemetery: lighters and matchboxes, bottles of wine, beer, or whisky, glasses, cans of drink, or ceramic tankards. Incense sticks, cigarettes, cigarette papers, and even hashish or marijuana joints also can also be found. Dozens of pieces of paper bearing dedi-cations, thoughts, or extracts from The Doors songs or Morrison’s poetry mingle with photographs, drawings, or declarations of love. This plethora of offerings gives an idea of the considerable number of people who, alongside tourists and Père-Lachaise regulars, come every day solely to honor Jim’s memory in their own way.

Fans in Search of the Legend

Colette Pétonnet, the first ethnologist to have made this cemetery the focus of research, highlights this “exceptional” power to encourage encounters and exchange between the living (Pétonnet 1982). “There are places which possess a permanent and indestructible ability to mediate… On Charonne hill, Père-Lachaise cemetery—opened in 1804 within the former Jesuit park—is frequented by a throng of vis-itors drawn by the many famous tombs buried in the greenery. Although burials continue to take place, it is used as a public garden by local Parisians who enjoy guiding tourists along its pathways” (Pétonnet 1987, 256). With thousands of people passing through it every day, Père-Lachaise is an extremely lively necrop-olis. The relationship between visitors to Jim’s grave (particularly the youngest) and the others who use the cemetery for their daily walks is sometimes extremely strained.

While visits to Père-Lachaise by foreign tourists often prove to be a unique and exceptional expe-rience, visits from fans of Jim Morrison—given their number—have an impact on cemetery life. This latter group is viewed by staff, regulars, and the rest of the cemetery public as a noisy, ill-bred, and above all uncontrollable community. Those wanting to “defend” Père-Lachaise cemetery and its image as a haven of peace or an open-air museum can only note with some concern the wild and inappropriate

© P

.U.F

. | D

ownl

oade

d on

06/

07/2

022

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

(IP

: 65.

21.2

29.8

4)©

P.U

.F. | D

ownloaded on 06/07/2022 from

ww

w.cairn-int.info (IP

: 65.21.229.84)

VRock Around the Grave. Jim Morrison’s Grave at Père-Lachaise

Ethnologie française, XLII, 2012, 3

invasion by Jim Morrison’s admirers, who, for the last forty years have “infested” this location that was, above all, designed to be a place of rest for the departed. In 1976, Michel Dansel noted that “this division has become a hub for hippies from all over the world, who come to ‘smoke’ and indulge in all kinds of antics on the grave of their guru James Douglas ‘Jim’ Morrison, the famous lead singer of The Doors, a rival band to ‘The Rolling Stones.’ He lies directly on the ground, enclosed by a simple cement border. When I visited Jim’s tomb, photos of young girls, drawings, locks of hair, cigarettes, empty bot-tles, and notes in a variety of languages had recently been deposited by disciples wanting to mark their passage. The utterly undemocratic and disrespectful fanaticism which drives Jim’s admirers prompts them to write inscriptions and graffiti all over the neighboring gravestones” (Dansel 1976, 227–228) and even on the plane tree next to the grave. This account demonstrates how, only five years after Jim Morrison’s death, the many people drawn to Père-Lachaise by his grave were already having a profound effect on the cemetery’s image. Furthermore, the word “hippies” used by Michel Dansel to describe the fans visiting Jim, a term which perhaps seems rather a caricature today, does not reveal the plurality of visitors differentiated by their age, origin, appear-ance, and behavior in the cemetery.

Since Jim Morrison died at the age of 27, his music and in particular his image—immortalized in thou-sands of posters, t-shirts, purses, and so on—seems to speak particularly to the youngest generation. Sooner or later, a number of these young people make their way to Morrison’s grave. Once in a lifetime, or perhaps more often, they feel the need to confront the most concrete representation of Jim on this earth, the place where his earthly life came to an end, and at the same time the moment (and monument) where his mythol-ogization—a process that had already begun during his lifetime—and his ascension to the rock firmament was definitively consecrated: his small grave in Père-Lachaise cemetery.

Young people aged between 14 and 35, alone or more often in small groups, form the majority of all visitors to the grave. “The curious thing is exactly the fact that there are many young people now, along with the oldest, since Jim Morrison is now someone for the”old dogs,” people of my age, in their sixties… So it is strange that this still continues today with young people: the fact is that this is something that has

endured, that has survived… So, whether that is linked purely to the legend or to the reality of Jim Morrison as a musician and band, I don’t know; in truth, I am not qualified to comment” (interview with Hugo, Père-Lachaise regular, April 2008). It is not uncommon to come across older couples of the idol’s generation, who would be the same age as Jim Morrison if he were still alive. For this latter group, The Doors and their lead singer embody memories of their youth and form part of their cultural education.

As well as these two most representative catego-ries of visitors to the grave, it is important to mention school groups, walkers on guided tours that take in Jim’s grave as part of a route exploring the celebri-ties of the cemetery, curious visitors (individuals or families) drawn by the constant comings and goings prompted by the presence of the grave, and improvised cemetery guides. These cemetery guides gather at the popular location to await visitors and offer them a tour of Père-Lachaise for a small tip. While some visitors are persuaded into taking a discovery tour of the ceme-tery, quite a few are interested solely in Jim Morrison’s grave: the only route that they will take within the walls of Père-Lachaise is a path leading from one of the entrances to this little corner of Division 6.

On their first visit in particular, they discover that Jim Morrison’s grave is rather hard to find: the 44 hectares of Père-Lachaise covered with vegetation and thousands of other grave monuments, the lack of any tourist signage along the avenues, and the modest

For want of a guestbook, fans make use of a tree next to the grave (photo by author, 2011).

© P

.U.F

. | D

ownl

oade

d on

06/

07/2

022

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

(IP

: 65.

21.2

29.8

4)©

P.U

.F. | D

ownloaded on 06/07/2022 from

ww

w.cairn-int.info (IP

: 65.21.229.84)

Michelangelo GiampaoliVI

Ethnologie française, XLII, 2012, 3

dimensions of the singer’s burial place which leave it invisible until only a few meters away. These are the obstacles that every “pilgrim” must overcome at least once. This tortuous and complicated path sooner or later results in one of the following: asking for direc-tions from another visitor to the cemetery, with the risk of taking the wrong path and ending up even further astray; hunting for a map of the cemetery and trying to find your bearings in spite of the often rather impre-cise scale of distance; or waiting for another group of more experienced-looking Jim fans to go past and fol-lowing them to your destination.

In reality, the most observant and daring visitors can still find Jim Morrison’s grave without needing to ask for help. Others can make use of one of the maps available at the conservation office entrance or sold alongside the kiosks and florists at the entrances to the cemetery. In fact, altruistic fans of “The Lizard King” have spared them many a “pilgrim” from the complete frustration of heading into a division, fol-lowing a path, and wandering aimlessly through the cemetery, because sooner or later you will inevi-tably come across one of hundreds of arrows—drawn in pen, stained, etched into walls or on the gates of numerous tombs and chapels—accompanied by three simple letters: JIM. Anyone attentive enough to follow the direction indicated by one of the arrows and its subsequent counterparts will eventually reach Division 6 and then Morrison’s grave without much difficulty. A “Morrison signpost” which can prove helpful for new young visitors: “Jim Morrison’s name was sign-posted from afar, sometimes even very far away, natu-rally using the walls of other monuments as signposts” (Dansel 1999, 150). Of course, this practice has not been met with approval by the majority of other reg-ular visitors to the cemetery.

Having spent several years observing the origins of the individuals and groups that visit Morrison’s grave every day, I realized that they were primarily for-eigners. However, it is worth noting that this charac-teristic applies not only to fans of Jim Morrison, but also more widely to all tourists visiting Père-Lachaise, with the number of foreigners exceeding the number of Parisians. The majority are English-speaking, pri-marily Americans and Canadians; considering the pull which this city, the world’s leading tourism destination, exerts for North American tourism, the reasons for this prevalence are easily understood. Many are also British and Scandinavian, from Sweden and Norway, countries where English is widely spoken. The percentage of

Scandinavians among visitors met near Jim Morrison’s grave is remarkable given these countries’ low popu-lation figures.

However, according to information from the cem-etery’s security officers and local regulars, the last ten years have seen a considerable increase in the number of visitors from Italy, Greece, Spain, and, recently, the former Soviet Union. In addition to these statements from the cemetery’s staff and regulars, these new waves of visitors are also borne out by an increase in inscrip-tions and graffiti near the grave in Italian, Spanish, or using the Cyrillic or Greek alphabets.

From Gift to Vandalism

The symbolism used by these worshippers making their pilgrimage to the grave involves common fea-tures that allow us to identify a ritual look whose most representative elements transcend geographic or gen-erational boundaries. In general, fans of Jim Morrison feel compelled to have his image (often just his face) on their person in some way, enabling them to gaze intimately at it or share it by showing it to others, whether fans of Jim or just people they meet on their way. Appearing on t-shirts, hats, bandanas, or pieces of fabric, displaying Jim’s image is a visual rallying sign. This is a key step in the approach that leads fans to the little “sanctuary” that the grave represents. Sometimes, it may be replaced or accompanied by other images

Anything can be used to show the way to Jim… (photo by author, 2008).

© P

.U.F

. | D

ownl

oade

d on

06/

07/2

022

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

(IP

: 65.

21.2

29.8

4)©

P.U

.F. | D

ownloaded on 06/07/2022 from

ww

w.cairn-int.info (IP

: 65.21.229.84)

VIIRock Around the Grave. Jim Morrison’s Grave at Père-Lachaise

Ethnologie française, XLII, 2012, 3

of great value to the community of fans, such as the inscription “The Doors” or the image of a lizard, Jim’s favorite animal. Less often, we find other symbols linked to the figure of Jim Morrison and the historical and cultural period on which he helped to make such an indelible mark: these may be peace or anarchy sym-bols, or even a marijuana leaf.

This look appears to be another sign that helps individuals to get closer to their icon: long, curly hair, sunglasses, a cigarette between their lips, a shirt, black leather pants, and boots. Although such individuals make up a small (but not insignificant) percentage, they are cultivating an appearance inspired by that of Jim Morrison. They are undoubtedly less striking than the Elvis Presley look-alikes who crop up more than once in life or on television, but they are still interesting to see and much appreciated by other tourists, who often ask to take a photo of them next to Jim’s grave…

The relationship with the spirit of Jim Morrison and what he still embodies does not end with a visit to the site of his grave dressed in a The Doors t-shirt, leaving an offering, a short moment of remembrance, and a photo taken next to the monument. Over the forty years that now separate us from July 7, 1971, the date of his burial, the phenomenon of popular devo-tion at Jim’s grave has developed some unique and unexpected forms and practices. Many of these have now helped to create the ritual journey enabling what is considered the most appropriate way to honor Jim’s memory and the “teachings” he left through his actions and words. This journey is neither codified nor gov-erned by structure or doctrine, but is instead the result of a process of observation and mimetic repetition of some of the behavior observed among those who have previously completed the journey. While such prac-tices would in the past have been passed on by word of mouth and through the traces left behind in the cem-etery by fans (graffiti, inscriptions), it can now draw on new means of dissemination, in particular the Internet.

Of the rituals that “must” be completed in order to claim a direct and privileged relationship with Jim Morrison’s grave and his spirit hovering nearby, the most famous consists of lighting and smoking a ciga-rette—better still, a joint—near the grave. Visitors can also balance this joint inside the stone border beneath which Jim lies, as if making an offering to the singer. Packets of cigarettes also feature among the items reg-ularly left on the grave. A heavy smoker, Jim Morrison was also a drinker, often consuming exceptional quan-tities of alcohol. From my own observations, I have

noted the frequency with which bottles of wine or liqueur, cans of beer, and glasses of champagne can be found on his grave. Although sometimes unopened, the majority of the bottles are left on the grave once they have been emptied, as drinking a bottle or pro-posing a toast to Jim’s health on his grave is one of the most famous acts undertaken by fans, deservedly due to the inextricable link (both in reality and in the con-struction of his legend) formed between the singer and alcohol, especially since the consumption of alcohol (and, of course, drugs) is forbidden within the ceme-tery walls; this simply increases the transgressive value of these actions for those undertaking them.

I remember once seeing a security officer severely reprimanding two American couples in their fif-ties who, with little concern for the security officer’s presence, had got out a bottle of champagne and four glasses and were drinking a toast to the artist’s memory. Even after the security officer had explained to them in perfect English that they were in a cemetery and not a café, the two couples did not move far away, instead continuing to stroll through the area around the grave with the bottle and glasses still in hand. The security officer, having spotted me, told me in French: “They know that I will finish my round, and they’re waiting for me to leave before my colleague arrives… But I’m staying here until he arrives, even if I have to wait for half an hour” (June 2009).

Criticized by other cemetery regulars, some fans may make use of their walk to the grave to take flowers, plants, and other gifts from other burial places, which

Bottles of whisky and skulls on the grave (photo by author, 2009).

© P

.U.F

. | D

ownl

oade

d on

06/

07/2

022

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

(IP

: 65.

21.2

29.8

4)©

P.U

.F. | D

ownloaded on 06/07/2022 from

ww

w.cairn-int.info (IP

: 65.21.229.84)

Michelangelo GiampaoliVIII

Ethnologie française, XLII, 2012, 3

they then place on the singer’s tomb. And while it is true that many visitors leave tributes of all shapes and sizes, an equally large number have also taken items away over the years: this was the case for the bust and shells that once decorated the tomb and that have now disappeared. The practice of stealing or appro-priating parts of the tomb, tributes, or objects left by previous pilgrims, as well as any other tangible items with a close connection to this famous figure who has become an object of devotion, is very widespread and well documented, both in the past and present. The parallel with saintly relics and their age-old worship within Catholic and orthodox religions is a striking one, as is the parallel with the “devotion market” for places where saints and martyrs lived and died and that are now places of pilgrimage.

Over these pages, I have demonstrated that rock culture also has its own places of pilgrimage, with Jim Morrison’s grave being one of the most famous examples in the world. However, the lack of a struc-tured organization (such as the Catholic Church for Saint Francis of Assisi or the estate that manages Elvis Presley’s legacy, organizing access to the grave, offer-ings, the sale of knick-knacks, and the provision of books where visitors can record their feelings) means that worshippers here are acting alone, with the effects easy to imagine: “Equipped with a marker designed for the purpose, they scribble a few lines tinged with fervor and admiration, sometimes betraying great emo-tion, and displaying the date and their name. These are not vandalistic or blasphemous acts; the transformation of the wall into a repository for written prayers (and more generally of the building’s facing into a writing board) is the sign of a relaxed relationship with the sacred place” (Segré 2002, 150).

Over time, the common view of Jim’s connection with the consumption of substances that could alter his state of consciousness and perception has had a not insignificant effect on the emergence of illicit prac-tices on the site. Outside of the minor theft of “sou-venirs,” the authorities responsible for looking after the area around the grave have been faced with other, more serious, forms of deviance. Up until the end of the 1990s, this small area of Père-Lachaise was best known as one of the areas of Paris where drugs could be bought and consumed on the spot. Accounts from the cemetery’s oldest employees and regulars talk of dealers (sometimes themselves passionate about the music of The Doors) mingling with Jim’s fans and selling hashish, marijuana, and synthetic drugs in an

atmosphere which was more like that of a rave party than a necropolis. “Junkies from all over the world con-verge on Père-Lachaise and, under the false pretense of being admirers of Jim Morrison, indulge in highly deplorable debasement of the area surrounding his grave” (Dansel 1999, 149). This is Michel Dansel’s stark summary of his state of mind as a regular visitor to the cemetery confronted with the spectacle that awaited him almost every day when he approached Morrison’s grave. And as is the case for any self-respecting celebra-tion, music was—and still is—one of the key elements of popular devotion at Jim’s grave, even more so if we recall his status as a rock star. Of course, this is nearly always music by The Doors, offered to (you could say imposed upon) other visitors, users, and employees of Père-Lachaise via stereo systems, guitars, bongos, or chorused songs. In the context described above, it is clear that other visitors to Père-Lachaise often con-sider the attitudes displayed within the cemetery by Jim Morrison fans to be desecrating and out of place.

These observers ignore the fact that the behavior they are condemning and finding intolerable is, to those displaying it, a decisive step towards a total merging with the object of their admiration, towards the highest form of devotion to Jim and the example he left behind in his life and actions. Jim Morrison, the symbol of a rebellious youth, can only be vener-ated through acts of transgression undertaken in his name and honor. I have lost count of the number of young people who told me, in a variety of languages, “I am sure that Jim would approve of the way we are marking his memory.”

These different perceptions of the cemetery bring us back to the issue of the multiple ways in which thousands of different people view and experience a place that remains, first and foremost, a necropolis. The conservation office protects the cemetery using the means at its disposal, with a view to preserving it as far as resources allow. The lack of enforcement and surveillance suited to the needs of a cemetery that attracts thousands of visitors a day has resulted in Père-Lachaise ultimately becoming a place allowing behavior that would be unacceptable elsewhere. A favorite spot for dissenting political and ideological expression (Tartakowsky 1990); male homosexual cruising (Teboul 1989); the theft of busts, stained glass windows, and general metal; and the filming of amateur films with often dubious inspirations, Père-Lachaise has thus become a hotspot of transgression

© P

.U.F

. | D

ownl

oade

d on

06/

07/2

022

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

(IP

: 65.

21.2

29.8

4)©

P.U

.F. | D

ownloaded on 06/07/2022 from

ww

w.cairn-int.info (IP

: 65.21.229.84)

IXRock Around the Grave. Jim Morrison’s Grave at Père-Lachaise

Ethnologie française, XLII, 2012, 3

in Paris within the collective imagination (Giampaoli 2010).

Jim Morrison’s grave is the primary stage where such illicit acts take place. Here, more than in any other location, the conservation office has implemented sur-veillance strategies for the monument and surround-ings designed to combat fans’ excesses. For several years there has been a camera hidden inside a small street light positioned next to the grave, monitoring the surrounding area which has become a market for drugs. The fact that this is the only street light in the entire cemetery (which also closes before sunset) quickly revealed its true function to more astute vis-itors. The constant presence of at least one security officer near the grave has therefore taken over the task of attempting to prevent the most dangerous forms of behavior. This prevention effort was also one of the causes of the removal of a second bust that was placed on the grave: the administration recognized and feared the power its presence (like that of the first bust) could have to stimulate and generate disorder among the singer’s many admirers (both male and in particular female). “The cleaning service removes everything apart from flowers. Anything that could be put to use to create disorder is removed. We remove all objects, all symbols that could serve as an attraction… Even the bust disappeared!” (interview with Guy, a former Père-Lachaise security officer, October 2008).

The Père-Lachaise conservation service has attempted to reduce some of these forms of behavior, with a certain level of success, through the almost constant presence of an on-site security office. At the beginning of the 2000s the cemetery service finally installed iron fencing around the grave and sur-rounding area, at a perimeter of around 30 meters, in order to prevent those wanting to go up to it from also damaging the surrounding graves and chapels. The authorities’ efforts have indeed resulted in a decrease in the most controversial episodes near Jim Morrison’s burial place and within the cemetery in general, par-ticularly over the last ten years. Despite this, the grave remains the most sensitive, most difficult to manage, and least “presentable” in the entire cemetery; and it remains just as popular, also helping to boost this

majestic Parisian cemetery’s global fame. The hundreds of people who invaded the cemetery on July 3, 2011, the fortieth anniversary of the singer’s death, and spent hours settled around the grave singing the majority of The Doors’ repertoire at the top of their voices, simply confirmed once again both the pull still exerted by this place and its transgressive power.

Jim Morrison’s early death is one of the elements that most helped to set (and mythologize) his image as a hard-line rock star and sex symbol, with his grave at Père-Lachaise quickly becoming the perfect backdrop for following his transgressive example: it would seem that the only possible way to pay tribute to Jim is to reproduce in this small corner of Division 6 what the singer did during his short life, in other words exceeding limits, dedicating oneself to excess, and behaving in a manner that is both free and provocative. Supplying and consuming drugs (in particular joints) and alcohol at the location; improvised rave parties to the sound of guitars and radios blaring at full volume; inscriptions and graffiti on dozens of chapel walls; cans of beer, bottles of champagne, cigarettes, and bras deposited as modern ex-votos… All such practices and forms of expression have helped to make his grave marker a form of “holy place of rock” at the heart of Paris. The flow of people to and from the grave is continuous, cosmopolitan, multilingual, and noisy, and seems to have turned Père-Lachaise (the most visited cemetery in the world) into a kind of small-scale reproduction of Paris (the most visited city in the world) extending just beyond its walls. This is a city for which Jim’s face is one of the most representative images to millions of people from Canada to Australia.

As regards Père-Lachaise, despite its historic links to the Paris Commune and the great social battles of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, its role as a memo-rial of the horrors of the Second World War through the monuments built there in remembrance of Nazi concentration camps, and its being home to the final resting places of figures who have shaped the history of humanity over the last few centuries, the majority of visitors still know it as “Jim Morrison’s cemetery.” The American star has thus played a role in building Paris reputation. ■

© P

.U.F

. | D

ownl

oade

d on

06/

07/2

022

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

(IP

: 65.

21.2

29.8

4)©

P.U

.F. | D

ownloaded on 06/07/2022 from

ww

w.cairn-int.info (IP

: 65.21.229.84)

Michelangelo GiampaoliX

Ethnologie française, XLII, 2012, 3

Bibliography

Charuty, Giordana. 1995. “Logiques sociales, savoirs tech-niques, logiques rituelles.” Terrain 24: 5–14.

Dansel, Michel. 1976. Au Père-Lachaise—Son histoire, ses secrets, ses promenades. Paris: Fayard.

Dansel, Michel. 1999. Les Lieux de culte au Père-Lachaise. Paris: Guy Trédaniel.

Delaporte, Yves. 1988. “Les Chats du Père-Lachaise. Contribution à l’ethnozoologie urbaine.” Terrain 10: 37–50.

eaDe, John, and Michael J. sallnow. 2000. Contesting the Sacred: The Anthropology of Pilgrimage. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Giampaoli, Michelangelo. 2010. Il cimitero di Jim Morrison. Trasgressione e vita quotidiana tra le tombe ribelli del Père-Lachaise di Parigi. Viterbo, Italy: Stampa Alternativa.

Gobin, Emma. 2005. “Le Triomphe des croyances. Catholiques et spirites autour de la tombe d’Allan Kardec.” Terrain 45: 139–152.

hopkins, Jerry, and Daniel suGerman. 1980. No One Here Gets Out Alive. New York: Warner Books.

laplantine, Gérard. 1993. “Inscriptions lapidaires et traces de passage: formation de langages et de rites.” In Ethnologie des faits religieux en Europe, edited by Nicole Belmont and Françoise Lautman, 137–160. Paris: Éditions du cths.

pétonnet, Colette. 1982. “L’Observation flottante. L’exemple d’un cimetière parisien.” L’Homme 22, 4: 37–47.

pétonnet, Colette. 1987. “L’Anonymat ou la pellicule protec-trice.” Le Temps de la Réflexion 8: 247–261.

pouChelle, Marie-Christine. 1983. “Sentiment religieux et show-business: Claude François objet de dévotion populaire.” In Les Saints et les stars. Le texte hagiographique dans la culture populaire, edited by Jean-Claude Schmitt, 277–300. Paris: Beauchesne.

seGré, Gabriel. 2002. “Le Rite de la Candlelight.” Ethnologie française 32, 1: 149–158.

seGré, Gabriel. 2003. Le Culte Presley. Paris: Presses universi-taires de France.

tartakowsky, Danielle. 1990. Nous irons chanter sur vos tombes—Le Père-Lachaise, xixe-xxe siècle. Paris: Aubier.

teboul, Roger. 1989. “Les Anges du Père-Lachaise ont de drôles de sourires—Approche ethnologique d’un lieu de drague homosexuelle à Paris.” Master’s thesis, University of Paris X—Nanterre.

© P

.U.F

. | D

ownl

oade

d on

06/

07/2

022

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

(IP

: 65.

21.2

29.8

4)©

P.U

.F. | D

ownloaded on 06/07/2022 from

ww

w.cairn-int.info (IP

: 65.21.229.84)