reconciling religious freedom with gay rights - LSE Theses ...

RECONCILING PEDESTRIAN-VEHICLE RELATIONSHIP

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of RECONCILING PEDESTRIAN-VEHICLE RELATIONSHIP

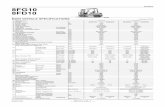

IJAUS VOLUME: 2, NUMBER: 2

29

TOWARDS AN APPROACH TO HUMANIZE THE STREET ENVIRONMENT: RECONCILING PEDESTRIAN-VEHICLE RELATIONSHIP

NORA OSAMA AHMED AssistantLecturer,HousingandBuildingNationalResearchCenter(HBRC),Giza,Egypt Abstract Thisstudyfocusesattentiononnewapproachesthathademergedseekingtocreateanequitablebalanceofstreetspace,andit isnotpossiblewithoutaneedtocompromisebetweenthestreetmovementfunctionaswellitsplacefunction,thetypeofcompromisevarieswidelythroughoutdifferentcities;approachesas20mphzones, 30 km/h zones, traffic signal priority, complete streets and transit friendly streets focus on streettechniques, whereas ‘woonerf’, ‘home zones’, and ‘shared space’ focus on street environment. The studystandsinthebeliefthatitismatterofhowthestreetphysicalenvironmentaffectsthewaypeopleuseitthanwhatit lookslikeandindoingso,itreviewspreviousexperiencesthatmadetargetedeffortstogetthemostoutoftheirstreets,bothastransportationlinksforallmodesofcommutersandasvitalplacesforpeopletoenjoy,inadditiontoitaddresseshowtomakestreetsworkwithallitscomponents,howtogetuseoftherightofwaytryingtoachievedifferentusers’needswithhavinglimitedconstraints;ensuringthateveryonecangetfromAtoBeasilybesidesenjoyingusingthestreetandconcludeswithidentifyinghowthechangeinthestreetphysical environmentaffect thewaypeopleuseandperceive the street andendsupwith specifyingdesignguidelinesthattranslatetherelationbetweenthephysicalattributesofparticularpublicrealm(streetdesign)and the range of behaviors that this street environment affords (users’ behavior) and its integration as anincentiveforthepromotionandintegrationofnon-motorizedmodes;specifyingastreetdesignapproachthatreconcilepeople,placeandtraffic,andcontributeincreatingsafe,attractiveandenjoyablestreets.1. Introduction Nowadays, restoring the functional manifold of the street becomes a trend, basing on the belief that thestreet’sfunctioncan’tbelimitedjustforthemovementofvehiclesandparkingspaces.The urban street of the 21st century will be a street for all users accommodating pedestrians, cyclists, andtransit ridersalike,balancingbetween theneed formobilityand theneed forqualitypublic space.Differentapproaches had appeared that call formoving away from segregating vehicles frompublic space andmovetowards sharing streets that take into consideration the movement and place street functions alike.Consequently, urbandesign and traffic planning face a complex challenge in achieving an equitable balancebetweentheinteractionbetweendifferentformsoftrafficandthesociallifeofthecity,sostrengtheningtheprofessionalbackground for theselectionof solutionshasbecomeaneedespecially thedesignofmeasuresnecessaryindifferenttrafficsituations.2. Humanizing the street environment Streets play an important, if not theprimary, role in shaping thequality and character of urban living, theycontributetothesociabilityandsenseofplaceandmakethecitysodistinctive,howeverthisstreetseniorityasaplacehadbeenlostandthefunctionofthestreethaschangeddramaticallywiththeintroductionofcars,andtheprevalenceofplanningidealsofmodernismtothepresentdaysinceWorldWarIIwhenLeCorbusier,oneofthemodernistmovement'sfounders,renouncedthestreetasaninadequatetransportationarterybysaying:“Our streets no longer work Streets are an obsolete notion. There ought not to be such a thing as a street; we have to create something that will replace them”.This simplifiedmono-functional viewof the streethadbeencriticizedby Lillebye (2007) saying that itwasa"limited"conceptionof thenotion"street",asLeCorbusierregarded itpurelyasatechnologicaldevicewiththe solepurposeof carryingpeople fromthevarious residentialandcommercialplaces that constituted thefunctionalistic town.Accordingly,only twotypesofstreetsprevailed, trafficstreetsandpedestrianstreets,astreetwaseitherdesignedfortraffic(ex.Themotorway),oritisdesignedforsocialactivities,andthedesignofstreetbecamedominatedbytwomainideas:1. The firstwas designing streets primarily for trafficmovement, rather than as places; inwhich theirmostimportantrolewastofacilitatevehiclejourneys.

IJAUS VOLUME: 2, NUMBER: 2

30

2. Thesecondwasmanynewbuilt-upareas,roadsystemswereestablishedinaccordancewiththeideaofsegregationcartrafficandpedestrian/bicycletrafficintocompletelyseparatetrafficsystems,Figure1.

The combination of these two ideas led to thewidespread introduction of ring roads that cut through thehistoric street patterns in our towns; pedestrian underpasses; pedestrianized streets in town centers; andmetalbarriersalongtheedgesofpavementstopreventpeoplecrossingroadswhenandwheretheywantto,Figure 2. Besides, designing streets primarily for traffic movement has reduced the richness and variety ofpublicspaceanditsuses,JanGehl(2010)hadcommentedonthisdegradationinthequalityofthecitysaying:“What was very important has been pushed to the side for long periods of time by the introduction of the automobile. People are starting to stand up and recognize that we have lost something which was always very important, and now we have time to recover from the first wave of automobile pressure, and can start to rethink a better balance where important things are not lost.”

As the shortcomingsof thisapproachhavebecomeapparentanewmovement to lookat streetswithin thebroader context of a community have appeared seek to extend the social zone and limit the traffic zoneimpact.Twoideashadgovernthenewmovementthatare:1. DesigningStreetsforpeople:inwhichtoshiftourstreetsawayfromanauto-centricapproachtoonethattreatsstreetsaspublicplaces,andprioritizesthemforwalking,bikingandtransit.2. Abalanced,multiple traffic useof street space, particularly in small cities andurban areas,moving“fromseparationtointegration”.Thismovementwasledbymanyarchitectsandsociologistswhocalledfordecisiveshiftinthewaycitieswerebuiltandtooktheefforttorehabilitatethestreetasatruesocialarena,amongthecontributorsJaneJacobs,GordonCullen,KevinLynchandDonaldAppleyard,inadditiontoJanGehlandWilliamWhyterepresentedvitalcontributors through focusing attention on the relationship between human activities and the built urbanenvironmentandtheabilityforhumanstonavigatewithinsuchenvironments.Thosefrontrunnershadcreateda transformation for the design and construction of public streets into places, they had adopted a sociallybasedapproachindealingwiththestreet;focusingonwhathasbeenreferredtoasthe‘socialusage’ofspace,those authors had dealt with practical realities concerning the patterns of human activity, in which theyillustratedtheinterplaybetweensociallifeandphysicalsettings;andthatwhatthestudycallithumanizingthestreetenvironment.The studyhighlights streetasaphysicalandsocialpartof the livingenvironment;asaplace simultaneouslyusedforvehicularmovement,socialcontactsandcivicactivities,thathaslongbeenarguedbymanyauthors,whomintheirdefinitionforstreethadtakenintheiraccountstreetasaplaceratherthanatrafficroute,andtreatingthemasqualityplacesinthemselves,andthishadbeenindicatedclearlybyMoughtin(1991),whenhesaid “The Street, in addition to being a physical element in the city, is also a social fact.” In his studies,Moughtinhasshownthestreetsocialuseas:1. Itcanbeanalyzed intermsofwhoowns,usesandcontrols it; thepurposesforwhich itwasbuiltand it’schangingsocialandeconomicfunction.

Figure 1: Show the Idea of Traffic System Segregation, according to (Hamilton-Baillie, 2000)

Figure 2: Illustrate the Concept of Segregation, according to (the Buchanan Report, 1963)

IJAUS VOLUME: 2, NUMBER: 2

31

2.Italsohasathree-dimensionalphysicalform(length,proportions,andsenseofenclosure)thatmakeupthemajorpublicopen space in thecitywhich,while itmaynotdetermine social structures,does inhibit certainactivitiesandmakeotherspossible.3.Itprovidesalinkbetweenbuildingsbothwithinthestreetandtothecityatlarge,itfacilitatesthemovementofpeopleaspedestriansorwithinvehiclesandalsothemovementofgoods.4. Ithasthe lesstangiblefunction in facilitatingcommunicationand interactionbetweenpeopleandgroups,thusservingtobindtogetherthelocalurbancommunity.5.Itsexpressivefunctionalsoincludesitsuseasasiteforcasualinteraction,includingrecreation,conversation,andentertainment,aswellasitsuseasasiteforritualobservances.Consequently,forthepurposeofthisstudy,streetisdefinedas:Anenclosedthree-dimensionalspacebetweentwolinesofadjacentbuildings,inwhichallformsofmovementcoexist,and interactwitheachother; it isaplacetostay,not justaplacetopassthrough.Thesidewalkandstreet furniture in the pedestrian domain and the roadway with the vehicular domain together form astreetscape;itisatermusedtodescribesomethingmorethanapublicinfrastructureusedformovement.3. Street environment challenges Themostapparentcharacteristicofthestreetisitsmanifoldoffunctions.Sincethemodernistperiod,theroleof theurban streethasbeen reduced to thatof a road; a conduit throughwhichvehicles andpeoplemove(Anderson,1980;Lozano,1990;Moughtin,1991).Thissimplifiedmono-functionalviewofthestreetischangingveryslowlyamongplannersanddesignerscomparedtotheeffortsdonetoillustrateitsmultifunctionalrolebysomeresearchers:thestreetasteacher(Clay,1991),thestreetasplaygroundforchildren(Gehl,2011;Moore,1991),thestreetasworkplaceforvendors(Habe,1988),thestreetasaplaceforsocialinteraction,recreationandpubliclife(Jacobs,1961).Streetswhether considered from thepointof viewofmobility, the stateof theeconomy,ourhealth, socialinteraction,orhowthecitylooks;theycancontributetobettercommunitiesbychangingthewaythatstreetsarethoughtaboutanddesigned,however,theconflictingrelationshipbetweenpedestrianandvehicleimpedethestreetfromachievingthesebenefits.Thereisaneedtosetthebalancebetweentheuseofstreetspaceforthroughusers(whocoulduseotherlinkstogetfromAtoB)andforlocaleusers(whoareseekingtomakeuseof thatparticular sectionof thestreet).Themore thestreetcanovercomethisconflict, themore thestreetachieveitsmultifunctionalrole.3.1. Pedestrian- vehicle conflicting relationship “It’s no big mystery. The best streets are comfortable to walk along with leisure and safety. They are streets for both pedestrians and drivers. They have a definition, a sense of enclosure with their buildings; distinct ends and beginnings, usually with trees… The key point again, is great streets are where pedestrians and drivers get along together.” AllanJacobs Jacobsinhispreviouswordsadvocatedpedestrian-vehicularinteractioninthepublicrealm,dependingonfieldresearchandobservationhefoundoutthatsafetyandcommunityvitalityweredecreasedonthesegregationofcarsandpedestrians,onthecontrary,multi-modalstreetsthatarecharacterizedbytheinteractionbetweendifferent modes work best and help in creating livable community by acting as attractive, welcoming, andexcitingplaces.ThestudypreparedbyJacobshadbeenassertedbyMoughtin(2003)whoillustratedthatthefunctionofthestreetgovernsthedegreeofinteractionbetweenpedestrianandvehicles;givingconcerntotheplacefunctionofthestreetcharacterizedbyalivelyandactivestreetthatwillincreasetheinteractionbetweenpedestrian–vehicularlikemanypedestrianizedtowncentersinBritainandincontinentalEuropeareextremelysuccessful,whileingivingconcernforgoodaccesstobothprivateandpublictransportwilldecreasesthisinteractionandmay be separation of high-speed traffic movement from pedestrian traffic will be necessary like ParisBoulevard,whichhaswidepedestrianpavementsseparatedfromtheroadwithtreesandinsomecaseslanesforparkedorslow-movingvehicles.TherelationbetweenpeopleandtraffichadbeenillustratedbyJanGehl(2010),hepointedoutthattherearefourbasicpatternsgoverningtherelationshipbetweentrafficandmorevulnerableroadusers,Figure3.Gehlshowed that the firstpattern is cars share spacewithothers inwhich the cardominates (eg. LosAngeles) -Vehicle roads,ora secondpatternwherecarsarekeptdistinct fromothers; separationbetween roadusers(eg.Radburn),orcarssharespacewithtrafficbutthepedestriansandcyclistsdominate,andthisthirdpatternprovides the principle within which the first “woonerven” were introduced in Delft. The fourth and finalpatternofVenicerepresentedinpedestrianstreets;wherecarsareentirelyexcludedisrareonanylargescale.

IJAUS VOLUME: 2, NUMBER: 2

32

ThethirdtypeillustratedbyJanGehl,showedthattraffic integratesonthetermsofslow-movingtraffic,andgiving priority to pedestrian and cyclists, require two main actions simultaneously, achieving somedisplacementoftrafficandatthesametimecreatinganappropriatebalancebetweendifferentusergroupsbyredesigningareliefstreettofacilitatethat;whereavarietyofusersandactivitieswouldbewelcome,asHansMonderman said: “Through the syntheses between traffic and public interaction we could build wonderful places that can tell the story of our past, the heritage and the cultural identity of place”.

Figure 3: Show the Four Traffic Planning Principles; illustrating the four types of relation between People and Traffic, according to Jan Gehl, and represented by (the researcher) 4. Approaches to reconcile pedestrian – vehicle relationship Manyprincipleshavebeen introduced foraviable streetdesignoptions thatbalance,multiple trafficuseofstreetspace;likethewoonerfidea,sojourn-playareas,shoppingErfs,trafficcalmneighborhoods,homezones,sharedspace,completeandtransit-friendlystreetsetc.Thispartofthestudydiscussestheseapproachesandstudiesthecommonpracticesthatreshapenotionsofhowcars,people,andpublictransitcouldcoexist.1.1. Complete Streets Itisanotionthatseekstocreatehealthystreetsthatbalancebetweenpedestriansandvehiclesmovementsinanattempttorejuvenatecommunitiesthatare invitingandcomfortableforeveryonewhousesthem.Manypioneers of the Complete Streets movement are working on establishing practices and models about thisnotion; spreading the world researching and producingmaterials trying to reach an accurate definition forCompleteStreetsapproach.TheNationalcompletestreetscoalitiondefined“completestreets”as:“Streets that are designed and operated to enable safe access for all users. Pedestrians, bicyclists, motorists, and public transportation users of all ages and abilities are able to safely move along and across a complete street; they are streets that work for all users, not just those using a car” (Completestreets.org.)Whereas,thedefinitionmadebyMinnesotaDepartmentofTransportation(MnDOT)definedCompleteStreetsmoreasapolicyratherthanstreets;inwhichitsaid: “It is the planning, scoping, design, implementation, operation, and maintenance of roads in order to reasonably address the safety and accessibility needs of users of all ages and abilities. Complete streets consider the needs of motorists, pedestrians, transit users and vehicles, bicyclists, and commercial and emergency vehicles moving along and across roads, intersections, and crossings in a manner that is sensitive to the local context and recognizes that the needs vary in urban, suburban, and rural settings” Itwasillustratedby(BarbaraMcCann,2005)thatthemainpolicyofcompletestreetsistoguaranteethattheentire right of way is designed to qualify safe access for all users, regardless of age, ability, or anytransportationmodewhichreturnwithagreatbenefit to thecommunity,andaccordingly that there isnoasingledescriptionforacompletestreetoraspecificsize,itisvariedintypes,Table3astheNationalCompleteStreetCoalitionsaid:

IJAUS VOLUME: 2, NUMBER: 2

33

“There is no one designs prescription for complete streets. Ingredients that may be found on a complete street include sidewalks, bike lanes (or wide paved shoulders), special bus lanes, comfortable and accessible public transportation stops, frequent crossing opportunities, median islands, accessible pedestrian signals, curb extensions, and more. A complete street in a rural area will look quite different from a complete street in a highly urban area. But both are designed to balance safety and convenience for everyone using the road.” 1. RuralrouteAcompletestreetinruralareasinstallsawidepaved shoulder in order to help pedestriansandbicyclists.

@Walkable&LivableCommunitiesInstitute

2. ArterialA complete Arterial streets install a bike laneand a protected sidewalk with grassy medianand street trees. The median also acts as atraffic calming for making riding a bike saferandmorecomfortable.

@ completestreet.org.2010

3. MainStreetA main complete street is characterized by largestreet trees in planting strips, good sidewalks andwell-markedcrossings tohelppedestrians travel totheir destinations along the street, and streetparking to givemotorist easy access,while coloredpavement to calm traffic by narrowing the travellane,keepingspeedsatanappropriatelevel.

@Walkable&LivableCommunitiesInstitute

4. ResidentialA complete residential street is characterizedbyslow-movingtrafficandsidewalks,whileforcyclists they can share the travel lane withmotorists as speeds are slowand traffic levelsare low, or they can easily share the one sidesidewalkwithneighborhoodpedestrians.

@Walkable&LivableCommunitiesInstitute

5. One-waystreetIn urban areas a narrow complete one-waystreetvariesinitstreatmentseithercompriseabike lane, on-street parking, and short, well-markedcrosswalks.

@completestreet.org.2010

Table 3: Types of complete street, according to the National Complete Street CoalitionItisagreeduponthattherearenospecialrequirementsfortheimplementationofcompletestreets,however,thecompletestreetcoalition identifiedkeytechniquesforurbanarterials in implementingacompletestreetusing a combination of physicalmeasures; traffic calming tools as chokers, bulb-outs, cobble paving, speedhumps,orroundaboutsinordertoreducethenegativeeffectsofmotorvehicleuse,alterdriverbehaviorandimproveconditionsfornon-motorizedstreetusersreducingspeedtobemorecompatiblewithpedestriansandbicyclists.Thecombinationoftechniques,included:• Mayuseroaddiettreatmentwherethenumberoflanesisreduced,andthefreespaceconvertedtoparking,bike lanes, landscaping,walkways,ormedians toenhance the streetenvironment forbicyclists andpedestrians.

IJAUS VOLUME: 2, NUMBER: 2

34

• Universal design features are installed, including audible signals, curb ramps, and a path on thesidewalk.• Corner treatments are installed and may include curb extensions, right-turn slip lanes, or tighterturningradii,allofwhichslowrightturnsandprovidegreatervisibilityforpedestrians.• Transitaccommodationsareimprovedinavarietyofwaysasthebusshelter.• Sidewalks, ifmissing,areinstalledandpedestriancrossingsareenhancedwithladder-styleorzebra-stylecrosswalkmarkingsandsignalmodificationssuchasacountdowntimer,inadditiontoDrivewaysmaybeconsolidated to reduce walkway interruptions by moving vehicles and raised medians are installed, whichimprovessafetyforcrossingpedestrians.CompleteStreetsproponentsseektotransformthelook,feel,andfunctionofthestreetsbychangingthewayofthinkinginplanninganddesigningstreets,callingtoalwaysdesignwithallusersinmindinordertomakeallusers feelwithasenseofplaceandcreateakindofsocial interactionbetweenallusers inadditiontootherbenefitsas:1. Economic Revitalization: a balanced transportation system provides accessible and efficientconnectionsbetweenresidences,schools,parks,publictransportation,offices,andretaildestinationsthathelpincreatingeconomicvitality.2. Improvesafety: byreducingcrashes;usingtrafficcalmingasinstallingraisedmediansandredesigningintersectionsandsidewalkswhichreducepedestrian’srisk,emphasizesafetyandconvenienceofbicyclists.3. Encouragemorewalkingandbicycling: installing facilities forpedestriansandcyclistsprovidesafetyandcreateawelcomingenvironmentforthem.4. Increased TransportationAlternatives: streets that keep all users inmindprovide travel choices forpeopleandgivethemalternativemodestoavoidtrafficjamswhichencouragestreetconnectivityandcreateacomprehensive,integrated,connectednetworkforallmodes.5. Createchild-friendlyenvironment:givingprivilegetowalkingandcycling,regeneratestheuseofthepublicspacewithbetterenvironmentalconditionsespeciallyforchildrenthathelpthemgetphysicalactivitybyencouragingthemtoeitherwalktoschoolusingsafesidewalksorcycleusingcomfortablebicyclingroutes.6. Enhance livablecommunities: Integratingsidewalks,bike lanes, transitamenities,andsafecrossingsintothecompletestreetdesignprovidesafeandaffordableaccessforeveryone,whethertravelingtoschool,work, the doctor, or any recreational place as restaurant that in turnmeet community’s goals in creating asuitableenvironmenttolive,workandplaythatimprovethequalityoflife.1.2. Transit-friendly streets TheProjectforPublicSpacesdefinedTransit-friendlystreetsas:“Places that “balance” street uses over having any single mode of transportation dominate. In many cases, this means altering a street to make transit use more efficient and convenient, and less so for automobiles – while still accommodating them. When these alterations are done right, a kind of equilibrium is achieved among transit, cars, bicycles, and pedestrians”. Transit friendlystreetsseek toachieveakindofequilibriumamongalluserswhether transit rider,motorist,cyclist,andpedestrian,soitworksonaddressingtheneedofthedifferentmodesoftransportation;fortransitrider it establishes a clear transit priority and a convenient, accessible transit stops and creates a strongpedestrian orientation by providing appropriate circulation space with clear crossing streets, adequateamenities and wide sidewalk that enable people to socialize; talk, meet friends, or watch other people, inaddition to reducing conflict between different modes, including reduction of vehicle speeds, all of whichcontributetocomfortandconvenience.It follows what PPS said “Understanding the nature of the problems on a street is the first step toward developing effective solutions to those problems” so it understands the need for flexibility in balancing userneeds, however the PPS (1998) identified five strategies for the design and traffic management of transitfriendlystreets andcanbetakenasgeneralstrategiesdependingoneachdifferentsituation,asTable4shows.

− Strategy1:ProvideAdequatelySizedSidewalksTransit friendly streets work on developing a strong pedestrianorientation in a street by first Widening Sidewalk toaccommodatepedestrianmovementaswellasseating,trees,busshelters, lighting and other appropriate amenities that supportsocial activities and secondly by using a traffic-calming physicaldesign technique that seek to widening sidewalks at congestedlocationsorintersectionssuchas“Nubs”or“Neckdowns”.

Sidewalk “Nubs” or “Neck

IJAUS VOLUME: 2, NUMBER: 2

35

downs”,@(PPS.org)− Strategy2:ProvideAmenitiesforPedestriansandTransitRidersTransit friendly streets provide amenities either throughsegregation by installing bus and light-rail stops along a street,concentrating passenger amenities in one location as subwaystations,thissegregationdecreasefromstreetqualityratherthanthe other approach to provide amenities through integratingtransit amenities into the street, treating bus shelter as streetamenities like benches, planter ledges, trees, telephones, lightfixtures, and information kiosks; clocks, sculpture, drinkingfountains,banners, and flags. This integration stimulatesactivityonthestreetandmakesastreetmorepleasantandcomfortable.

Provide Amenities forPedestrians and TransitRiders,@(PPS.org)

− Strategy3:CreatePriorityLanesforTransitVehiclesIn a commercial street, it is common to use a transit-priority ortransit-onlylaneinordertocreateatransitfriendlystreetsuchasa transit mall. However due to the difficulty of keeping privatevehiclesfromusingreservedbuslanescitiesuseda“contra-flow”system thatprovides a single laneonedirection forbuseswhileproviding for cars the other street lanes but in the oppositedirection.Despitethe importanceofthisstrategy is in improvingthebusesefficiency,butitdoesn’timprovethequalityofplace.

Create Priority Lanes forTransitVehicles@(PPS.org)

− Strategy 4. Initiate Traffic-Calming Measures forAutomobilesTransit friendly streets use certain techniques of traffic calmingthatcausenoor littledelayandallowasmoothandcontinuousmovementofbuses.Theyusemethodsthatdon’tchangeontheelevationofthestreetandonlyallowmethodsthatcreate“pinchpoints” as road narrowing by roadmarkings;mini-roundabouts;busberthsornubs;andchangedmaterialsofroadsurfacessuchaspaversinsteadofchangesinstreetelevation.

Narrowing a road to one lane using ‘pinch point” @ (PPS.org)

− Strategy 5. Redesign Intersections and ModifySignalizationTransit friendly streets design its intersections in a way thatincreasetransitefficiencybyusingsignalizationchangesassignalpreemption thatallowbusesnot to stop,orusingprioritygreensignalsthatgiveagreenlighttobusesbeforeautomobilesdo.Inaddition to using different traffic calming design features atintersections as bus nubs that shorten pedestrian crossings andprovide safewaiting places,while in heavy volumes roadways a“queuejump”methodisusedthatnarrowstreetattransitstoptoprevent automobiles from passing buses and to reduce thedangertopedestrianscrossingthestreettothebusstop.

Signal preemption work @ (images .google.com.eg n.d.)

Table 4: Strategies for the design and traffic management of transit friendly streets, according to (PPS, 1998) 1.3. Shared Street Concept This concept is considered to be the revisiting of street integration that had been lost since the sixties, asaccordingto(Southworth&Ben-Joseph,2004)theunderlyingconceptofthesharedstreetsystemisbasedonthe integration between all users’ street, where pedestrians, children at play, bicyclists, parked cars, andmovingcarsallsharethesamestreetspace,withanemphasisonthecommunityandindoingsotheconcepthadpassedbymanystagestryingtoimprovethestreetqualityandtorestorethesocialfunctionwhichislost

IJAUS VOLUME: 2, NUMBER: 2

36

inthestreetonthebaseofsegregation;ineachstageithaduseddifferentmeasuresas:“Environmentalareas”or“Urbanrooms”;Inthelate1950sandearly1960s:Buchanan'stheoreticalconcepts,“Trafficintegration”and“Trafficcalming”;In1960s:sharedstreetgrassrootsmovement,“Woonerf”translatedasresidential,orlivingyardFigure4;In1969:NiekDeBoerovercomingthecontradictioninBuchanan'sconcept,Designedfor“30km/h”or“20mph”;Inthelate1970s:thedevelopmentofEuropeanslowstreets,“HomeZones”Figure5;Inthe late 1990s: UK equivalent term for “woonerf”, “Shared Space” Figure 6; During the nineties as analternativeapproachtotrafficcalming,besidessimilarsolutionslike20mphspeedlimitzone,pedestrianzonesandcul-de-sacrealizedindifferentcountries,withorwithouttheoriginaltrafficsign.

Figure 4: Dutch Woonerf, according to (Schepel, 2005)

Figure 5: Methley Home Zone, the UK, according to (methleys.org.uk)

Figure 6: Shared Space Scheme, according to (vector1media.com)

ItcanbeconcludedfromthepreviousthattheideasofsharedstreethadpassedthroughmanystagesFigure7,butall thesestagesstrives forall thesameobjectivesas the ideologistsof the“woonerf”and“HomeZone”pioneers illustrated (i.e. streets where children and the elderly can cross safely, diversity andmixed trafficflows)howeverthe“woonerf”and“HomeZone”consideredbeingthemostadvancedformoftrafficcalmingwhichimposesevenmorerestrictions,requiringcarstotravelatwalkingspeed,while“sharedspace”extendsthis way of thinking and the way of working by depending on the psychological traffic calming instead oftraditional traffic calming measures; replacing traffic rules, typical traffic engineering elements by informalsocialrules;sothesestreetshavebeenstrippedofthesignsandmarkings;andvariouslyreferredtoas“legiblestreets”oreven“nakedstreets”.

There is general consensus on the characteristics of shared street according to (Duany et al., 2000; Ewing,1996; Jacobs,1961); it isastreet thatseek toenhancethepedestriancharacterof thestreetbyprovidingacontinuoussidewalknetworkand incorporatingdesignfeaturesthatminimizethenegative impactsofmotorvehicleuseonpedestrians,ofparticularimportanceistheroleplayedbyroadsidefeaturessuchasstreettreesandon-streetparking,whichservetobufferthepedestrianrealmfrompotentiallyhazardousoncomingtraffic,and to provide spatial definition to the public right-of-way. However, there isn’t a set formula or list ofprerequisitesthatguaranteeasharedstreet,itisrelativelyplannedforvariety,choice,andsatisfaction;sousesomekeyfeaturesthatserveavarietyofusesandusers,andinmanywaysas:• Makeuseofvariousinstallationssuchasstreetfurniture,bollardsorplanterstoguideusers.• Clearsignstoreinforcethemessagetodriversthattheyareenteringadifferentkindofstreet• “Sharedsurfaces”featurethatmakecardriversrealizetheyareguestsinanareawherechildrenmayplayonthestreet.

Figure 7: Illustrate the Emergence of “shared Street” Concept, according to (the Literature Review and represented by The Researcher)

IJAUS VOLUME: 2, NUMBER: 2

37

• The priority inwoonerf andHome Zones is for the other users rather than vehicles, depending on“Prioritybynegotiation”totacklebetweenallroadusers,unlikesharedspacewhereallusersareequal.• It shares the point of view of influencing driver’s behavior to reduce speed “psychological trafficcalming”; they embody the design principles of safety through uncertainty, whereby an absence of priorityalong with short driver sight-lines, social activity and a lack of clarity regarding vehicle routes, significantlyreducevehiclespeeds.• Low-speedenvironmentnotexceedingmorethan30km/h(20mph).• Thedesignofthespacemakesitclearthatitcanbeusedthisway“self-explainingstreet”,ratherthanextensivesignage,butSharedSpaceexploitsthisfurtherwithnakedstreets.5. The dilemma of sharing or separating Newapproacheshademerged seeking to improve thequalityof streets. Thesenewapproachesbasedonacareful andmulti-disciplinary approach thatmeetpeople’sneeds in streets asplaces for living,workingandmovingaroundinthroughthetrade-offthestreetspace.Attheheartofthesenewapproachesliesreconcilethrough traffic flowwith other urban activities; emphasizing on the balance betweenmovement and place;peopleandvehiclesbyfocusingattentiononmixedpedestrianandvehicularstreetsthroughintegration.Theattempts to reconcile the relationbetweenpeople, place and traffic varies, but it canbe classified into twomain approaches, the first adopted the notion of separation as complete streets, transit-friendly streets,“Traffic signal priority” streets and 30 Zone or 20mph zone, in which complete and transit-friendly streetsdidn’tmean allmodes on all roads but rather support the idea of flexibility in design tomeet the land-useneedsandpossibleusers.The concepts use expressions as develop “a balanced transportation system” and achieve “a kind ofequilibrium” to assert on the idea of taking into consideration the needs of allmodes but on a segregatedstreetsurface;dealingwitheachuserindividually,thesamewith“Trafficsignalpriority”streetsand30Zoneor20mphzonebut it focusesmoreonusingcertaindesigntechniquestoreducespeedtobemorecompatiblewithpedestriansandbicyclists.Thesecondapproachadoptedthenotionofintegrationassharedstreetsthataimtodesignstreetasasocialspaceforallusers;wherethestreetspaceissharedbetweendriversofmotorvehiclesandotherstreetusersinalow-speedenvironment,withthewiderneedsofallusers-drivers,transitvehicles,bicyclists,andpedestriansof all kinds (disabled, elderly, children, and lingerers); regardless of age, abilities or disabilities beingaccommodated,and indoingsothestreet isopentoall formsof transportbutpedestrianshavepriority;astheycanmovewithcompletefreedomacrosstheentirewidthofthestreet,sothestreetbecomesasharedsurface.Inreviewingdifferentapproachestoreconcilepedestrian-vehiclerelationship,itcanbeassumedthatthereisa scale for the relationship between people and traffic starts with the traditional street where there issegregation between themgiving priority to traffic and at the other end of the scale is pedestrianized areagiving priority to pedestrians and between them lies complete streets, transit friendly streets, traffic signalprioritystreetsandatempo30zone(30km/hzone)or20mphzonesandalsosharedStreets(i.e.pedestrianpriorityzone),howevertheformeraremorerelatedtotraditionalstreetsregulationswhilethelatterisrelatedtopedestrianizedarearegulations,Figure8. It isaspectrumofhumanizingthestreetenvironmentandeachportionofthisspectrumisconsideredtobeaformofthenewformsofurbanstreetsthathaveemergedtohumanize the street including; “pedestrianized” street, auto-restricted zones, malls, traffic-managedneighborhoodstreets,“shareusestreets”asHomeZonesintheUKandWoonerfintheNetherlandsand,morerecently,“privatized”indoorcommercialstreets.

IJAUS VOLUME: 2, NUMBER: 2

38

The design guidelines that humanize the street environment Humanizingthestreetenvironmentrepresentedtheanswerforhowtosolvetheconflictingrelationbetweendifferentuserswherepedestrians,bicyclistsandtransitpassengersofallagesandabilities,aswellastrucks,buses,andmotorists,cancomfortablycoexistwitheachother,howtosatisfythedesireofmovementfortrafficandpedestrianaswell as satisfy the desire for on-street activities as walking, jogging, playing, skating, talking, watching, sitting,selling,partying,waiting,andsoonintheavailablelimitedamountofstreetspace.Theapproachhasbeeninnovativelyappliedtoavarietyofstreetconditionswithdifferentcharacters,sothereisnorecipe for reconcilingpedestrian– vehicle relationship.However, according to (Bongardt et al., 2010), generaldesign guidelines can be deduced based on “Push and Pull Approach”. The design guidelines include a set ofmeasuressimultaneouslyconcerningthethreemainaspectsofthestreetthatare:Traffic,Place,andPeopleTraffic : Applyguidelinesconcernedwiththemovementofthedriverofthemotorvehiclewhereit isallowedtoenter the street but its accessibility was limited by using physical features for controlling vehicle speeds andcreatingabalancebetweendifferentmodesof transport throughadoptingactivities thatpushcarusersoutoftheircars,minimizingthenegativeimpactsofautomobileuseonpedestrianssoastocreateengagingpublicspacesthatdrawpeoplein;so,itimposedrestrictionsonthedriver;theaccessibilityofmotorizedtransportwaslimitedinordertomakethepedestrianaccessibilityeasier;wheremotorizedvehiclesmayonlystopandparkindesignatedareas,andthespeedofmotorizedvehiclesarecontrolledusingtrafficcalmingtechniquesandatsomezoneitmaylimitto30km/h,besidesusingsharedsurfacethat,givespedestriansandmotorvehiclesequalrightstothestreetspacebyeliminatingcurbboundarybetweenasidewalkandvehicleright-of-way,Figure9.

Figure9:GuidelinesconcernedwithTrafficmovementPlace : Applyguidelinesconcernedwithpedestrians,cyclists,public transportusers theneedsofall thepeoplewhousethemasfatherspushingstrollers,grandmothers,children,walkingtoschool,peopledrivingtowork,bicycle messengers, people using wheelchairs, and people taking the bus by using physical features forimprovingthequalityofstreetenvironmentandcreatingasenseofplacethroughadoptingtwomainactivities:Figure10− First:Activities that supportpublic transport; trying topull cardriversoutof their cars toenvironmentallyfriendlymodesoftransportthroughtheprovisionofbettertransitdesignfeaturesandtransferpossibilities;toturntheusageofpublictransitandcyclingintomoreappealingmodes

− Second:Activitiesthatacttoservenon-motorists;anddesignmulti-modalstreetsastheredistributionof roadwayspace tocreateabalancebetweendifferentmodesof transportbyprovidingbetter facilities forwalkingandcycling;andsupportingthestreetasplacefunctionusingfunctionallandscapedesignfeatureswith

Figure 8: Show the relation between People and Traffic, according to (the research analysis)

Usingphysicalfeaturesforcontrollingvehiclespeedsandcreatingabalancebetweendifferentmodesoftransportthroughapplying“PushEffects”strategies

IJAUS VOLUME: 2, NUMBER: 2

39

highqualitythatgivenewvaluetostreetspace,besidescreatingastreetlifebycreatingawelcomingstreetspacewherepeople liketowalk,bikeandstaythatwillbring inreturnmorelifetothestreetsandagreaterwealthofexperience,andthelastdesignfeatureisactivefrontagethatemphasizesthesenseofplaceinthestreet through streets linkagewith landuse that creates good scenery and viewsand creates activity in thestreet;thattranslatedintomakingthefrontagealongstreetactive.

Figure10:Guidelinesconcernedwithemphasizingtheplacefunctionofthestreet People : Achievingwhatthepeopleneedinanyparticularstreetdoesn’tmeanthatit’sasharedone,itismoretodowiththewaypeopleuseitthanwhatitlookslikesothemoreusersareengagedinthestreetthemore the street becomemore human. Some approaches apply guidelines that address a driver’sinternal ability to notice and avoid a potential conflict with other road users; bymanaging driverbehaviortominimizetherisktootherstreetusersthroughPsychologicalcuesasuncertainty,intrigueandriskcompensationandself-explainingstreet.Figure11

Figure11:Guidelinesconcernedwithusersofthestreet Intracingthesedesignguidelinesitisrecognizedthatthemoretheyarecorrelatedtoeachother,andworkinparallel;themorethestreetenvironmentisbeinghumanized;designingthestreetinawaythatsendsapsychologicalcuetotheuserinthestreetandguidehimhowtobehave;accordinglyengagedriverswiththesurroundingenvironment,causingthemtodrivemoreslowly,attentively,andcourteously;creatingaccordingto(Monderman&Hamilton-Baillie,2006)whattheexpertsso-called"psychologicaltrafficcalming";inwhichaspeoplereachthestreet,theymoveslowlyenoughtomakeeyecontactwitheachotherandconsiderhowtheyrelatetoother“users”(pedestrians,bicyclists,driversoftransitvehicles,etc.)ofthespace;achievingabetterstreetsafetythattheDutchcallitaccordingto(Aviewfromthecyclepath,2010)‘Sustainablesafety’

Usingphysicalfeaturesforimprovingthequalityofstreetenvironment&creatingasenseofplacethroughapplying“Pull-effect”strategiesand“Pull&Pusheffect”strategies

ManagedriverbehaviortominimizetherisktootherstreetusersthroughPsychologicalcues(Uncertainty,etc.)

IJAUS VOLUME: 2, NUMBER: 2

40

Figure12byinformingeachuserinthestreethowtobehave;usingspeedreductionsastrafficcalmingmeasuresorreducingtrafficsignsandroadmarkingcreateriskcompensationanduncertaintyenvironmentthatmakethedrivertoactually feelunsafeatspeedsapproachingandabove20mph(32km/h)sotheyslowdownandall roaduserskeepsharplyawareofwhatishappeningaroundthem;makinguseoftheireyecontact,andthatassertMonderman’squotewhenhesaid“When a situation feels unsafe, people are more alert and there are fewer accidents”Anotheraspectliesinthe design for place guidelines; as not only did these guidelines contribute in enhancing the street environment forpedestrianandtransituserstryingtogetthemoutoftheircarsusingpulland/orpusheffects,butalsoitencouragemoreattentiontotheenvironmentbygivingdrivers,andothers,interestingfeaturestolookatinterestingInstallations,suchasgardens, art, or benches and at the same time intriguing drivers, signaling to them that they should expect theunexpectedandtravelslowlyandwithcaution(i.e.uncertainty);as whensomething’sworthseeing,afterall,peopleslowdown.Inadditionto,theactivefrontageandstreetlifedesignedthestreetascommunityspace;leavingalastingremindertodriversthattheyareguestsinthatcommunityspace;forcinghimtodriveslowly.Figure12:Themainthreepillarsofthedesignguidelinestohumanizethestreetenvironmentasdeducedbytheresearcher 6. Conclusion This study highlighted attempts to tame traffic in cities around the world, and this process of trying tohumanizeenvironments,againsttheconstantgrowthinlevelsoftrafficincities,stillcontinuestoday.Thetypesofprotectionvarybetweenstreet separationascomplete, transit friendly streets,and20mphand30km/hzones,orstreetsharingassharedstreetswiththeirdifferentpatternsasawoonerf,homezones,andsharedspace.Thesetypesofprotectionshadfocusedattentiononfacingthedeteriorationinenvironmentandstreetsafety,howeverthestudyshowedthatsharedstreetsfocusedonstreetenvironment;thesocialpartaswellasthephysicalpartof the street,on thecontraryof thecomplete, transit friendly streets,and20mphand30km/h zones that focused on street techniques rather than street environment; as limiting the traffic speed,easingtrafficandreducingaccidentsregardlessofstreetenvironment,studyingeachandeveryneedandtrytosolvetheconflictthatwillarouseaccordingtotheirvariety,neglectingfactorsthatmakepeopleuseanddonotusethestreet.Sharedstreetconceptwasacombinationofelementsthatworktolimitthevolumeorspeedoftrafficwhileatthesametimecreatinggreatersenseofcomfortinhopethatpeoplewillusethestreetspace,itdepends on the behavioral change of all street users which HansMonderman name it psychological trafficcalmingratherthanlimitingcartrafficanditsspeedsbythetraditionaltrafficcalmingmeasureswhichmeansthe traffic code should be replaced by a social code and in investigating the difference between theseapproaches it is indicated that humanizing the street environment not only depend on ‘vehicle’ (includingbicycles) and ‘street’ (design) but also it incorporates ‘human’ (behavior) in setting its design guidelines; soadopting streets and vehicles to the human capabilities; reducing the frequency of conflict between streetusersandachieve‘sustainablesafety’byinformingeachuserinthestreethowtobehave.Thus,theconceptofsharedstreetisconsideredtobeanefficientattempttoreconcilepeople,place,andtraffichowever,thereisnoblueprint for humanizing the street environment, it depends on the context, if a shared street is an appropriatesolutionforaparticularsituation,changingthesituationmaycall fordifferentsolutions; itmayneedtoanoverlapbetweendifferentapproaches.Thus,theattempttohumanizethestreetenviornmentshouldbetreatedasanexperiment until the correct “fit” for the context is found. There should be a study which aspects of thedifferentapproachesworkwelltogether,aseverycaseneedstobeexaminedindividuallywithtrafficcalmedandtransitsolutionsappliedaccordingtotheparticularcircumstances.

Using physical features to create environmental context that sends Psychological cues

‘Achieve Sustainable Safety’

Influence users’ behavior, informing each user in the street how to behave

IJAUS VOLUME: 2, NUMBER: 2

41

7. References Anderson,J.,(1980),OnStreets,Cambridge,Mass:MITPress.Anderson-Watters,C.(2009).Transit-FriendlyDesignGuidelines.FredrickCounty,Maryland.A view from the cycle path (2010). Sustainable safety. Retrieved from a view from the cycle path website URL:http://www.aviewfromthecyclepath.com/2010/01/sustainable-safety.html(AccessedMarch26th,2015)Bongardt,D.,Breithaupt,M.andCreutzig,F.(2010),BeyondtheFossilCity:TowardslowCarbonTransportandGreenGrowth,Eschborn,Germany,GTZ.Clay,G.(1991),TheStreetasateacher,PublicStreetsforPublicUse.NewYork:ColumbiaUniversityPress.Complete Streets (2010).” Complete Streets Bill Passes in Minnesota “Retrieved from National CompleteStreets Coalition website URL: http://www.completestreets.org/policy/complete-streets-bill-passes-in-minnesota/(AccessedJune9th,2014)CompleteStreets (2010).”PolicyElements“Retrievedfrom NationalCompleteStreetsCoalitionwebsiteURL:http://www.completestreets.org/changing-policy/policyelements/#vision(AccessedApril23rd,2014)Duany,A.,Plater-Zyberk,E.andSpeck, J. (2000),SuburbanNation: theRiseofSprawlandtheDeclineof theAmericanDream,NewYork:NorthPointP.Engwicht, D. (1999) Street Reclaiming: Creating Livable Streets and Vibrant Communities. Philadelphia, PA:NewSocietyPublishers.ProjectforPublicSpaces,Inc.(1998).TCRPReport33:Transit-FriendlyStreets:DesignandTrafficManagementStrategiestoSupportLivableCommunities,TRB,NationalResearchCouncil,Washington,DC.Gehl,J.(2010),CitiesforPeople,IslandPr.Gehl,J.(2011),LifebetweenBuildings:UsingPublicSpace,6thEd.,IslandPress.Habe, R. (1988). Sharing the urban space of third world city: Street hawking in Nairobi. EDRA 19: People'sNeeds/PlanetManagement.Hamilton-Baillie,B.(2000),HomeZones-ReconcilingPeople,PlacesandTransport,WinstonChurchillMemorialTrustHamilton-Baillie,B.(2008)."Sharedspace:reconcilingpeople,places,andtraffic."journalofBuiltenvironment34(2):161-181.Hass-Klau,C.,G.Crampton,etal. (1999)."Streetsas livingspacehelpingpublicplacesplaytheirproperrole;goodpracticeguidancewithexamplesfromatowncenterstudyofEuropeanpedestrianbehavior."Jacobs,J.(1961),TheDeathandLifeofGreatAmericanCities,NewYork:VintageBooks.Lillebye,E.(2007).TheStreetasanExtendedRoadNotion,NorwegianUniversityofScienceandTechnology.Laplante,J.andB.McCann(2008)."CompleteStreets:WeCanGetTherefromHere."ITEJOURNAL-InstituteofTransportationEngineers,78(5):24.Litman,T.(1999)."TrafficCalmingBenefits,CostsandEquityImpacts."VictoriaTransportPolicyInstitute.Lozano,E.(1990),CommunityDesignandtheCultureofCities,Cambridge.MA:CambridgeUniversityPress.McCann,B.(2005)."CompletetheStreets."(APA)AmericanPlanningAssociation.Monderman,H.,Hamilton-Baillie,B.,etal.(2006),SharedSpace-:thealternativeapproachtocalmingtraffic,Trafficengineering&controljournalvol.47,no8. Moughtin,C.(1991).TheEuropeancitystreet.Part1:PathsandPlaces,TownPlanningReview62(1),51-77.Moughtin,C.(2003).Urbandesign:StreetandSquare,ArchitecturalPress,Oxford.Moore,R.C.(1991).Streetsasplaygrounds,PublicStreetsforPublicUse,NewYork:ColumbiaUni.Press.PPS (2010). “A Guide to Transit-Friendly Streets” Retrieved from Project of Public Spaces website URL:http://www.pps.org/transitfriendlysts/(AccessedJune19th,2015) PPS (2009). “TheBenefits of Reinventing Streets as Places” Retrieved fromProject of Public SpaceswebsiteURL: http://www.pps.org/thebenefitsofcommunitybuildingthroughtransportation/ (Accessed December 6th,2015) Reinventingurban transport (2010). “Can"sharedspace"streetdesign reassurevulnerableusersandstillbeshared space?” Retrieved from URL: http://www.reinventingtransport.org/2010_10_01_archive.html(AccessedOctober24th,2015)RUDI (2009). Streets for Living-Ben Plowden. Retrieved from the Resource for Urban Design InformationwebsiteURL:http://www.rudi.net/books/10245(AccessedJune5th,2015)Southworth,M.,andBen-Joseph,E. (2004)."Streets forPeopleToo."ArchitectureWeek journal :PageB1.1-B1.2.