Qualitative evaluation of three ‘environmental management systems’ in the New Zealand wine...

-

Upload

lincoln-nz -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Qualitative evaluation of three ‘environmental management systems’ in the New Zealand wine...

Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (2005) 1175e1187

www.elsevier.com/locate/jclepro

Qualitative evaluation of three ‘environmental managementsystems’ in the New Zealand wine industry

Kenneth F.D. Hugheya,*, Susannah V. Taitb, Michael J. O’Connellc

aEnvironment, Society and Design Division, PO Box 84, Lincoln University, Canterbury, New ZealandbC/-53 Morven Ferry Road, RD1, Queenstown, New Zealand

cBRANZ Limited, Private Bag 50 908, Porirua City, New Zealand

Received 21 April 2003; accepted 13 July 2004

Abstract

The wine growing industry is increasingly important to the New Zealand economy and increasingly its marketing is associated

with the country’s ‘clean and green’ image. Over 60% of New Zealand’s wine companies have adopted at least one of three mainenvironmental management systems: Sustainable Winegrowing New Zealand, ISO 14001 and Bio-Gro. We undertook a qualitative,survey based, comparative evaluation of these systems within 15 wine companies. The key findings are that while each system

appears to have its own strengths, in general, no one environmental management system is better than the other. However,implementation of an industry specific system, for example SWNZ, in combination with a generic process-based system, for exampleISO 14001, aids in the development of a more sustainable wine industry.� 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Wine industry; New Zealand; Environmental management systems; Comparative evaluation; Triple Bottom Line

1. Introduction

The introduction of environmental managementsystems (‘ems’) is relatively recent in the New Zealandcontext yet there are three main ‘ems’ being imple-mented throughout the New Zealand wine industry.These are: Sustainable Winegrowing New Zealand, ISO14001, and Bio-Gro.

In this paper, we report on a comparative andqualitative evaluation of these three ‘ems’ with regard tothe New Zealand wine industry. This evaluation is basedaround an examination of questions associated withTriple Bottom Line (TBL) sustainability considerations

* Corresponding author. Tel.: C64 3 325 2811; fax: C64 3 325

3845.

E-mail address: [email protected] (K.F.D. Hughey).

0959-6526/04/$ - see front matter � 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved

doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2004.07.002

as well as issues of implementation, marketing andrelationships with broader aspects of environmentalmanagement in New Zealand.

The information gathered for this research wasobtained through a qualitative survey of vineyardsusing interview-based questions. The approach wasa pragmatic one based on a desire to carry out anevaluation that would provide the basis for immediatepolicy advice to those wanting to implement a newsystem.

This paper begins with background about theenvironmental context and ‘ems’ within the NewZealand wine industry including key issues in evaluatingsystem choice and performance. The research methodused is outlined and is followed by a presentation of theresults. Further discussion and policy implications areintroduced followed by a final concluding section.

.

1176 K.F.D. Hughey et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (2005) 1175e1187

2. Background

2.1. The environmental context of the New Zealandwine industry

The wine industry in New Zealand is increasinglytrading on the ‘clean green’ image of the country [1]. Butto what extent are companies responding to thechallenge of operationalising this clean green rhetoric?The distinctive features of the New Zealand wineindustry have been recognised as its relative youth, theprevalence of small-scale operations with relatively highunit costs, its distinctive ‘‘clean and green’’ image, anda focus on high quality wines [1]. However, these factorshave only been functions of the New Zealand wineindustry in the last two decades. During this time periodthe industry has experienced a boom e not only in theincreased number of plantings, but also in increaseddomestic and export sales [2]. For example, data fromMAF [3] indicate that between 1990 and 2000 thenumber of wineries increased from 131 to 358 (C173%),total production area grew from 4880 to 9752 ha(C100%) and the value of wine exports grew fromNZ$18.4m to NZ$168.6m (C816%).

The Wine Institute of New Zealand (WINZ) overseeslegal and marketing issues and aids the development ofoverseas markets. With the growing concern about theinternational decline of environmental quality, WINZhas been quick to capitalise on New Zealand’s perceivedclean green image [4] and promote New Zealand winesin environmentally conscious export markets with itscatch phrase ‘the riches of a clean green land’ [5].However, the clean green image may be more ‘apparent’than ‘distinctive’. The increasingly negative impact ofsome agricultural sectors on the environment in NewZealand [6] is threatening this image and the wineindustry must act to counter these impacts if it wishes tocompete successfully in an increasingly environmentallyconscious global market.

There is also evidence that the wine industry itself mayface serious future water shortages (unsustainable aquiferdraw-down) most notably in the Marlborough region,one of the main wine-producing areas in the country [7].There is also pressure coming from British and Europeanimporters for Australasian wines to be sourced fromactivities that are not harmful to the environment [8].

2.2. EMS development in the New Zealand wineindustry

Monitoring and modifying actions in the wineindustry are crucial to maintaining and protecting theenvironmental integrity of the wine industry in NewZealand. Implementation of voluntary environmentalmanagement systems, in combination with achievableindustry targets, should help pre-empt irreversible

damage to the natural environment and allow theindustry to operate sustainably.

The uptake of environmental management systems(‘ems’) is relatively recent in the New Zealand contextand key questions remain: e.g., how cost-effective arethese systems, and do they have the ability to achievesustainable production? A range of key voluntaryenvironmental (self) management systems used in NewZealand have been recently scrutinised [9] as a guide toassist businesses and policy makers in their decision-making. It is imperative therefore, that the wine industrygrasps the value of a well-implemented ‘ems’ and usesthis tool to define and maintain a harmonious relation-ship with the environment.

There are three main ‘ems’ being implementedthroughout the New Zealand wine industry: SustainableWinegrowing New Zealand (SWNZ e formerly NewZealand Integrated Wine Grape Production), ISO 14001and Bio-Gro New Zealand (Bio-Gro). Each systemdiffers in its aims, objectives and implementation pro-cesses and consequently its long-term goals. The SWNZscheme was introduced into New Zealand in 1998/1999and has been widely adopted by New Zealand vineyardsand wineries. The implementation of the ISO 14001system has been limited to a select number of vineyardsand wineries located in the Martinborough/Hawkes Bayregions. The Bio-Gro system is an organic certification,which has only been accredited to a small number ofvineyards and wineries in New Zealand adhering tostrict organic practices.

Although recently some authors [10,11] have extolledthe potential synergies and complementarities betweendifferent systems, little work has been undertaken toexamine comparative system performance. Certainly, noresearch has been undertaken to compare the perfor-mance of each of these systems against standardisedquestions in either the wine or other industries in NewZealand. In this paper, we report on a comparative andqualitative evaluation of these three ‘ems’ with regard tothe New Zealand wine industry. The evaluation is basedaround an examination of questions associated withTriple Bottom Line (TBL) sustainability considerationsas promoted by Elkington [12], i.e., the challenges ofachieving economic prosperity, environmental qualityand social justice, but also around aspects of imple-mentation, marketing and relationships with broaderaspects of environmental management in New Zealand.The three major systems used in the New Zealand wineindustry are now described.

2.3. Characteristics of EMS used in the NewZealand wine industry

2.3.1. SWNZSWNZ was launched in 1998/1999 under the di-

rection of Winegrowers of New Zealand after several

1177K.F.D. Hughey et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (2005) 1175e1187

years of trialling involving industry executives and wine-producing companies [13]. Development of the systemoccurred in response to two factors: international trendsthat were emerging in many New Zealand markets anda realisation that existing practices could not besustained [14]. In the 2001e2002 season, there were2601 vineyards voluntarily participating in the SWNZscheme, which collectively represented over 60% of thetotal area planted in vines [13]. The SWNZ scheme isa holistic approach to grape growing that aims forcontinued improvement toward sustainability [5]. It isbased on a scorecard/manual providing a series oftargets derived for various facets of vineyard operationsthat aim to help vineyard managers become aware ofimprovements that need to be made [15,13].

Basler and Boller, and Jordan [16,17] defined the keyaim of integrated production as the production ofsuperior grapes and wine using environmentally soundmethods, while observing the economic requirements ofa business, and seeking the overall reduction in the useof man-made inputs. The SWNZ scorecard identifiesseveral targets that are critical to integrated productionincluding soils and fertilisers; sward and irrigationmanagement; and pests and diseases [18]. It recognisesthat sustainability has several components includinga financial element [18].

SWNZ is based on the Swiss ‘Wadenswil IntegratedProduction Scheme’, which has been very successful andgained increased international attention. The Wadenswilscheme has four distinct advantages [17]:

� It is based on self-evaluation;� It provides market recognition that sustainablepractices have been achieved to differentiate theseproducts from those produced with non-sustainablepractices;

� The scheme is flexible with continued updating andintroduction of new technology; and

� It provides desired direction through the pointssystem so that growers are guided from conventionalto sustainable methods.

Perhaps a good measure of how well the SWNZscheme is performing is a comparison of currentpractices against these Wadenswil advantages. Firstly,SWNZ companies currently operate on a self-evaluationsystem, with an external audit performed on a three-yearbasis [13]. Secondly, anecdotal evidence from wineryrepresentatives indicates that accredited companies areyet to experience the full marketing effect of the systemand potential marketing opportunities are perhapsmissed due to the lack of eco-labelling that distinguishes

1 Membership had increased to 310 members by early 2003. The

percentage of NZ vineyards adopting SWNZ remains around 60%

(Tessa Renton, pers. comm., Sustainable Winegrowing New Zealand).

accredited companies from those companies lackingenvironmentally sound practices. Thirdly, the SWNZmanual is considered a ‘living document’ and as such isalways updated with new information and technology[19]. Finally, the scheme is based on a vineyardscorecard system that provides targets for companiesto work towards [15]. The vineyard scorecard is beingdeveloped so that sustainable winery practices can alsobe integrated into winemaking practices [15] thusoptimising SWNZ accredited wine companies’ movetowards sustainability. Manktelow et al. [13] also statedthat the SWNZ ‘ems’ ‘provides a path.to harvest ‘‘theriches of a clean green land’’ well into the future’.

2.3.2. ISO 14001The ISO 14000 series has been established as

a certification process for environmental managementsystems [20]. ISO 14001 is a voluntary standard [20] thataims to support environmental protection and preventpollution in balance with socio-economic needs.

The ISO 14001 system is designed around implemen-tation of an organisation’s environmental policy. Thepolicy should be directional and lead to the identifica-tion of environmental aspects which in turn are subjectto the development of objectives, targets and processesof implementation. It is these processes that are thenmonitored, audited and subjected to periodic review.Ultimately, this approach is anticipated to lead tocontinuous improvement in the environmental perfor-mance of an organisation.

New Zealand was the first country in the world toactively promote the adoption of ISO 14001 as part ofits environmental integrity strategy [21,22]. There arecurrently eight New Zealand wine companies involvedin the ISO 14001 system that have formed the LivingWine group as a means of sharing information withinthe group and dissipating the high costs of implementa-tion [23].

Hamner [24] has stated that ISO 14001 accreditedcompanies cannot be compared because, beyond thestructure and certification, they are all different. Inaddition, Gleckman and Krut [19] have critiqued ISO14001 and drew four conclusions regarding its short-comings. Arguably, of greatest importance is the factthat the environmental information prepared by an ISO14001 certified company is confidential and unavailableto bodies outside the organisation. This contrasts withother environmental initiatives, such as EMAS (Eco-Management and Audit Scheme), that are movingtowards greater disclosure of environmental informa-tion in an effort to ensure accountability for business’actions [20,25].

2.3.3. Bio-GroTheNewZealandBiological Producers andConsumers

Council Inc. (trading name Bio-Gro New Zealand) was

1178 K.F.D. Hughey et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (2005) 1175e1187

established in 1983 and their standards supportingsustainable land management have since become highlyrespected throughout the world [26].

There are five key principles governing organicfarming [26]:

� Encouraging and enhancing biological cycles;� Maintaining and improving long-term soil structureand fertility;

� The extensive and humane management of livestock;� Maintaining genetic diversity; and� The cycling of organic matter and nutrients withina production system avoiding all forms of pollution.

Vineyards and wineries are currently operating underthe organic orchards and tree crops standards and theprocessing standards, respectively, although Bio-Gro iscurrently developing specific standards for viticultureand winemaking. Full certification requires that com-panies comply with standards for a minimum of threeyears [26].

There exist some negative perceptions concerningorganic certification including high commercial risk;lack of flexibility and sustainability; inconsistent poli-cies; and high Bio-Gro levies for processed products[17]. However, those who choose to practice organics areoften willing to overlook such receptors due to theirdeep-rooted philosophical outlook concerning the pro-duction of consumer goods and their recognition ofa potentially prime market position.

2.4. Key issues in evaluating system choice andperformance

Two important points of reference are required whendeveloping an ‘ems’ that will help a company maintaina production regime that points the company in thedirection of sustainability.

Firstly, the economic, environmental and socialinnovations of a company are inextricably linked andcritical to a company’s overall performance. As thesethree factors are the basis of the Triple Bottom Line(TBL) concept, they are considered the underlyingnotion to achieving sustainability [12]. Thus a well-designed ‘ems’ will recognise these three factors.

Secondly, it is important that an ‘ems’ takes intoaccount the characteristics of the New Zealand wineindustry. In order to achieve the ultimate goal of an‘ems’ e long-term sustainability e a company, and ona larger scale an industry, must first identify existingunsustainable practices; and then, identify the shortterm goals the company/industry need to resolve inorder to achieve the long-term goal of sustainability.

In the early 1990s, the New Zealand wine industryidentified the unsustainable course in which the industry

was headed. Practices such as calendar-based spraying,use of pre-emergence herbicides, unmonitored irrigationand clean cultivation were no longer seen as sustainable[14]. In order to evaluate these systems, questionsencompassing the elements of TBL and the day-to-daychallenges of wine companies as identified above neededto be developed.

3. Methods

The information required for this research wasobtained through a qualitative survey of vineyards,using interview-based questions rather than via a long-term quantitative examination of biophysical indicatorsthat would enable an ‘objective’ inter-system evaluation.Our approach was based on the pragmatic desire toundertake an evaluation that would provide the basisfor immediate policy advice to those seeking toimplement a new system, and to policy makers seekingto provide advice on which system wine growers shouldimplement.

Fifteen selected vineyards/wineries (four Bio-Gro,five ISO 14001 and six SWNZ) were chosen for thestudy. Table 1 provides a listing of the ‘ems’ used by,and vineyard area of, the surveyed wine businesses.

Three of the ISO 14001 accredited companiesinterviewed had both ISO 14001 and SWNZ; however,the effects of both systems working together were notspecifically discussed. However, from the informationgiven during the surveys, the three companies tended toplace greater emphasis on the process-orientated ISO14001 system than on their goal-orientated SWNZsystem, therefore for the purposes of this research theyare considered primarily as ISO 14001 companies. Theselection of the vineyards/wineries was via a stratified

Table 1

The ‘ems’ type and vineyard size of businesses surveyed (hectares of

vines)

Vineyard Type of ‘ems’ Area of vines (ha)

1 SWNZ 2.1

2 SWNZ 21

3 SWNZ 50

4 SWNZ 33

5 SWNZ 1300

6 SWNZ 81

7 ISO 14001 50

8 ISO 14001 N/A

9 ISO 14001 and SWNZ 23

10 ISO 14001 and SWNZ 50

11 ISO 14001 and SWNZ 38

12 Bio-Gro 162

13 Bio-Gro 5

14 Bio-Gro 9

15 Bio-Gro 0.5

1179K.F.D. Hughey et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (2005) 1175e1187

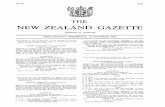

sample, firstly through the selection of each voluntarysystem and secondly through the region in which thevineyard/winery was located. A distribution of vine-yards/wineries throughout New Zealand was made toexamine whether any regional differences occur for eachsystem. Fig. 1 shows the regions in which the surveyedvineyards/wineries were located.

Each interview involved a series of ‘yes’ or ‘no’questions, which then provided the basis for ongoingand in-depth discussion. Where possible, interviews wereconducted face-to-face, otherwise telephone interviewswere held. A pilot study was held prior to thecommencement of formal interviewing to determinethe appropriateness of survey questions.

Based on the above considerations, a list of key(abridged) questions asked of winegrowers is listedbelow:

1. Are there any environmental/social/economic/otherbenefits due to the implementation of your ‘ems’?What are they specifically?

2. Are there any disadvantages due to ‘ems’ imple-mentation?

3. What does sustainable management mean to you?Do you run the business with sustainable manage-ment in mind? Does your sustainable management

Fig. 1. Regional distribution of wine companies surveyed. Companies

surveyed were located in region: 2 Auckland (2), 5 Hawkes Bay (3), 6

Wellington (3), 7 Nelson (1), 8 Marlborough (3), 9 Canterbury (1), 10

Central Otago (2), Total (15).

have an economic, social or environmental focus?Or a combination of the three factors?

4. Why did you choose your ‘ems’ over others?5. Do you believe that water, soil and spray issues are

serious environmental issues for vineyards andwineries in New Zealand?

6. Has the ‘ems’ improved the efficiency of thebusiness? For example, the operational and organ-isational efficiency or the economic efficiency of thebusiness.

7. Has the ‘ems’ had a marketing impact? Is it solelya marketing tool? Has it given your businessa competitive edge/product differentiation?

8. Do you believe that with the help of your ‘ems’ youare conforming or performing?

9. Do you believe New Zealand is really clean andgreen and do you take advantage of this catchphrase? Is the WINZ claim ‘the riches of a cleangreen land’ justifiable?

10. Do you think that New Zealand legislation isappropriate with regard to viticulture and theenvironment?

11. What was the driving force behind implementingyour ‘ems’ (e.g., stakeholders, legislation)?

12. Is the framework of your EMS easily personalisedto your business or is it relatively inflexible to yourpersonal needs?

4. Results

The results from the survey can be broadly dividedinto the following discussion areas, which togetherrepresent a logical reclassification of the questions askedin the survey:

� Comparative environmental (and social) effective-ness

� Business implications� System issues� Environmental sustainability and environmentalmanagement issues

4.1. Environmental (and social) effectiveness

4.1.1. Benefits and disadvantages of each systemThe businesses surveyed were first asked ‘Had they

experienced any environmental/social/economic benefitsfrom the implementation of their respective systems?’Secondly ‘Were there any other benefits of note?’ andlastly ‘Had any disadvantages ensued from the imple-mentation of the ‘ems’?’. The perceived environmental,social and ‘other’ benefits are illustrated in Table 2.

When collated, the perceived environmental benefits ofthe systems showed that SWNZ, ISO 14001 and SWNZ/

1180 K.F.D. Hughey et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (2005) 1175e1187

Table 2

Perceived benefits from the implementation of SWNZ, ISO 14001 and Bio-Gro

Environmental

management

system in use

Environmental Social Economic/business

Decrease

in spray

usage

Elimination

of sprays

Improved

sward

management

Improved

soil

management

Increased

staff knowledge

of environment

Content

neighbours

Increased

neighbour

awareness

Increased

business

structure

Improved

grape and

wine quality

1 SWNZ X X

2 SWNZ X X X X X

3 SWNZ X X

4 SWNZ X X X X X X X

5 SWNZ X X X X X

6 SWNZ X

7 ISO 14001 X

8 ISO 14001 X X

9 ISO 14001 and SWNZ

10 ISO 14001 and SWNZ X

11 ISO 14001 and SWNZ X X X

12 Bio-Gro X X X X

13 Bio-Gro

14 Bio-Gro X X

15 Bio-Gro X X X

ISO 14001 accredited companies decreased their usage ofsprays, whereas Bio-Gro companies generally eliminatedspray usage. The SWNZ and Bio-Gro companiessurveyed also commented on improved soil and swardmanagement, whereas the ISO 14001 and SWNZ/ISO14001 companies indicated no such improvement2.

Those experiencing improvements in sward manage-ment stated that it was largely due to extensive use of covercrops and inter-row mulching. In addition, companiesexperiencing improved soil management were able tocategorise these improvements as improved structure,activity, compaction, knowledge and monitoring.

It is not known whether those companies that haveadopted the ISO 14001 system have incorporatedspecific objectives for sward and soil management. Ifthey have, then auditors and stakeholders would expectto see improvements in these areas.

With regard to the perceived social aspects of thesystems, the SWNZ and ISO 14001 companies com-mented on the increase in their staff’s knowledgeconcerning the environment. These companies alsocommented that their neighbours were more contentdue to the changes that had occurred in the company.

In addition to the common benefits stated above, theSWNZ companies recognised that the implementationof their scheme had led to an overall healthierenvironment, improved canopy management, decreaseduse of water, improved vine balance, increased organicmatter in the soil, facilitation of monitoring and testing.

2 SWNZ/ISO 14001 companies (9, 10, and 11) will be discussed in

the text as solely ISO 14001 companies (survey results indicate these

companies to be process rather than target oriented).

The SWNZ benefits have also been evident in shiftingaway from conventional practices.

The ISO 14001 accredited companies surveyed notedthat in addition to shared benefits, they also experi-enced: decreased waste, particularly through recycling;decreased use of natural resources; continual improve-ment of business systems; peer support and informationsharing [27]. Apart from the comment regardingeventual savings, the majority of ISO 14001-companyspokespeople stated that they were yet to see anyeconomic benefits. Additional benefits noted by an ISO14001 company spokesperson were increased account-ability, the empowerment of staff, and the ability todrive constant improvement within the company.

The Living Wine Group expressed the benefits of theISO 14001 system as: environmental protection; exporttrading on adefensible image;measured savings in inputs/outputs usage; increased staff contribution to companyimprovement; and spin-offs from adopting a holisticapproach [23]. The survey indicates that ISO 14001accredited companies are still experiencing these benefits.

Additional benefits noted by the Bio-Gro companyspokespeople surveyed are increased staff safety, de-creased leaching of chemicals into aquifers, increasedbiological activity, externalities are internalised, aidinglocal employment, and an increase in consumer interestdue to organic branding.

Common disadvantages of the ‘ems’ included theexpense involved in accreditation and the amount ofpaperwork involved in each of the systems3. These

3 Costs: SWNZ (NZ$300 annually); Bio-Gro (c. NZ$2000 with a c.

NZ$1200 annual renewal fee); and ISO 14001 (NZ$5000e20,000).

1181K.F.D. Hughey et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (2005) 1175e1187

comments were reiterated throughout many of theinterviews and they were the only grounds for common-ality between the system disadvantages. Hamner [24]identified that developing an ISO 14001 ‘ems’ is a costlyexercise. This is particularly the case if a company ownsmore than one vineyard throughout New Zealand.However, the cost of certification is potentially a smallprice considering the returns on information and tech-nology that aid advancements in the industry.

The spokespeople for the Bio-Gro accredited com-panies identified further disadvantages of their system;these included potential spray drift from neighbours thatcould cause loss of certification and the increased labourcosts.

Further disadvantages identified by SWNZ ac-credited companies included lack of marketing, lack ofregional consistency and a slight risk increase ingrowing/quality of grapes. Hoksbergen [14] recognisesthat the SWNZ scheme is not without risk, although itgenerally provides a pragmatic balance between envi-ronmental concerns and productivity with an underlyingphilosophy focusing on continual improvement.

4.1.2. Reasons for choosing each systemThe reasons given for choosing each system were very

diverse and none of the comments concerning each ofthe systems corresponded.

The reasons given for companies choosing SWNZcertification included:

� the progressive and appropriate nature of the systemcompared to other options;

� the scheme best fitted with existing practices;� the system has industry support/recognition; theavailability of the system;

� SWNZ’s flexibility to evolve; more practicable andgoal orientated than ISO 14001;

� more flexible than Bio-Gro;� it leads to more sustainable outcomes than ISO14001 and Bio-Gro.

The SWNZ system is the most New Zealand-focusedsystem and allows the most appropriate options to beavailable to New Zealand grape growers. The limitednumber of audits conducted inhibits the supposedprogressive nature of the system. A potential drawbackwith SWNZ is that external audits are conducted ona three-year basis therefore if problems arise, it may takeseveral years to recognise and rectify a problem. Thereare no immediate plans to reduce the duration of theaudit period to one year or less [28].

The reasons ISO 14001 company spokespeople gavefor choosing their certification included: the system wasthe best of what was available; choice of certificationwas a collective decision (of The Living Wine group);the system enables a greater choice in company targets;

ISO 14001 is very accountable; and the system putsprocesses in place. The widespread recognition of theISO 14001 system means these companies should receivethe benefit of the system internationally.

Reasons for choosing Bio-Gro certification includedthe system’s compatibility with the winegrowing com-pany philosophy; the high standards required to gainaccreditation; the certification identified the company asorganic; the sustainability of the system itself; and thesystem’s IFOAM (International Federation of OrganicAgricultural Movements) accreditation. Recognition oforganic production is publicised through the Bio-Grologo, which is available only to accredited companies,after three years of compliance.

4.1.3. Driving forces behind implementing each systemBerry and Rondinelli [29] have identified four factors

driving proactive environmental management:

� Regulatory demands;� Cost factors;� Stakeholder forces; and� Competitive requirements.

It is important for society to recognise that theultimate reality of voluntary systems is that the systemwill, over time, be only as good or as sustainable asthe underlying business reasons behind its implemen-tation e which are most likely to be the private benefitsto the company that justify it to its stakeholders [20].

Methods for promoting sustainability may be due toany one of the driving forces listed above although itwas not stated by those surveyed to which driving forcethey would accredit this factor. Business philosophyitself is recognised as a stakeholder force as it is arguablythe stakeholders who ultimately determine the directionof the company. The use of the ‘ems’ as a potentialmarketing tool is becoming an increasingly importantcompetitive requirement in New Zealand, with theadvent of international consumers becoming more con-cerned with environmental issues [14].

Further driving forces recognised by SWNZ accred-ited companies include increased efficiency (competitiveforce), formalisation of existing practices (competitiveforce) and official recognition by the industry (stake-holder force). Though formalising existing practices thecompany is identifying the need for an ‘ems’ and theimportance that it may play in the future concerningrelationships with suppliers, customers, employees andenvironmental regulatory policies and agencies [20].Implementing an ‘ems’ that is recognised and endorsedby the New Zealand wine industry will aid internationaltrade and appease any issues that stakeholders may have.

ISO 14001 certified companies stated that additionaldriving forces included the influence of other winecompanies; the ‘ems’ enables accountability; the ‘ems’

1182 K.F.D. Hughey et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (2005) 1175e1187

provides increased quality; and an ‘ems’ may influencefuture non-tariff barriers. Therefore, environmental per-formance will become a powerful tool for bargainingduring international trade negotiations.

In addition to the driving factors recognised above,spokespeople for Bio-Gro companies also identifiedthat, as the only available New Zealand organic certifier,adopting Bio-Gro was the only way to endorse theorganic nature of their company.

4.2. Business implications

4.2.1. Implementation and business changes requiredImplementation of Bio-Gro and ISO 14001 appears

to have been difficult largely due to the time andpaperwork involved. The majority of SWNZ spokes-people stated that implementing the system was merelya formalisation of existing practices and thereforeimplementation was not difficult.

There were no other difficulties expressed by thespokespeople for Bio-Gro and SWNZ, although otherdifficulties experienced by the ISO 14001 includedovercoming staff resistance, ensuring integration of thesystem into the company and setting initial benchmarksto be reached.

There were no major changes made by the ISO 14001and SWNZ accredited companies, whereas the Bio-Groaccredited companies found that their largest changeoccurred through the employment of more staff to caterto a more labour intensive vineyard.

The ease of implementation was not considered thereason for the success of the ‘ems’ for the Bio-Gro andISO 14001 accredited companies, whereas the SWNZaccredited companies considered it important but notthe sole reason for their success in the business.

4.2.2. Improved business efficiency from implementingeach system

In general, each of the ‘ems’ was believed to improvethe efficiency of the business by providing structure andinformation and aiding documentation and understand-ing. Those SWNZ and Bio-Gro companies that believedtheir systems had not helped efficiency considered it wasbecause the business had become more labour intensive.Other SWNZ and Bio-Gro companies stated that thesystems were in place from the initial development of thebusiness and therefore there had been no change tobusiness function. Some ISO 14001 companies believedit was too early to tell if business efficiency had beenimproved by implementing their system.

4.2.3. Flexibility of each systemMost of the implementers of the various systems

believed that the systems were all easily personalised totheir individual businesses. There was one exception,which identified SWNZ as being inflexible between

regions. Under SWNZ standards, protection againstpests and diseases such as Botrytis (a fungus), whichthrives in humid conditions, is difficult to control andsubject to penalisation, however, innovative controlproducts are being developed for the industry that willassist in ameliorating this aspect [30].

4.2.4. Marketing aspects of each system, particularlythe export implications

The New Zealand wine industry has accepted itsposition as a global competitor and insists on buildingup its share of the world market on the basis ofsupplying premium quality wine to niche markets [1].This statement recognises the importance of nichemarketing, that is, the implementation of an ‘ems’ ispotentially a way to enter a niche market, stand outfrom the competition via product differentiation andpromote the clean green New Zealand image.

The majority of spokespeople believed that NewZealand is not really clean and green and winemakers donot take advantage of this catch phrase. Many of thosewho do take advantage of the catch phrase believed thatit is more of an innate happening, as New Zealandproducts are often immediately associated with a cleangreen image.

The marketing impact of each of the systems has beenvaried. While Bio-Gro accredited companies havenoticed that their certification has had a marketingimpact, SWNZ and ISO 14001 accredited companies areyet to notice any marketing benefits from the imple-mentation of their ‘ems’. All of the companies believedthat their respective ‘ems’ made them more attractive inthe market place though none of the companiessurveyed had implemented their systems solely asmarketing tools. While Bio-Gro and SWNZ spokespeo-ple believed that by implementing their ‘ems’ theirbusiness experienced a competitive edge/product differ-entiation, ISO 14001 accredited companies perhaps havean advantage as it is an internationally developed systemthat already enjoys business advantages [20].

Eco-labelling allows a company to market theenvironmental soundness of their operation, productor service. A major problem affecting the marketingimpact of SWNZ at the time of this study was the lackof eco-labelling, however, a brand logo was produced in2003 [28]. On the other hand, Bio-Gro and ISO 14001use eco-labels to differentiate their products.

4.3. System issues

4.3.1. Orientation of each systemThe orientation, goal or process, is a very important

element of an ‘ems’. It determines the outcomes of asystem and ultimately determines the sustainability ofa system. The majority of SWNZ and Bio-Gro companyspokespeople believed that their systems were goal

1183K.F.D. Hughey et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (2005) 1175e1187

orientated, while on the other hand, the majority of theISO 14001 accredited companies believed that their‘ems’ made them a process-orientated business. This isconsistent with the premise on which each ‘ems’ is based.

4.3.2. Integration of each system into the businessAll spokespeople believed that their systems were well

integrated into the company and acknowledged by allstaff. While it is important for an ‘ems’ to have topmanagement support [29], it is equally important thatstaff become involved and have a sense of ‘ownership’[31] as this aids the success of the ‘ems’ within thecompany. When implementing an ‘ems’, the organisa-tion needs to change or adapt to the ‘culture’ of ‘ems’ inorder to successfully integrate environmental issueawareness into their daily work practices [32]. TheLiving Wine group believes that due to its ‘bottom-up’approach, everyone in the company has a strong senseof ownership [27].

4.3.3. Performance/conformance issuesAll businesses surveyed believed they were ‘perform-

ing’ with respect to their ‘ems’, and consequently, withregard for the New Zealand environment. However, it isimportant to reiterate that the adoption of an ‘ems’ initself provides no clear or continuing evidence ofcommitment to improvements in environmental perfor-mance, let alone sustainability [20].

4.4. Environmental sustainability and managementissues

4.4.1. The issue of sustainable managementNew Zealand’s predominant piece of environmental

legislation is the Resource Management Act 1991(RMA) which emphasises sustainable ‘management’ asopposed to sustainable ‘development’. The RMA hasemployed the TBL focus to define sustainable manage-ment as ‘.managing the use, development and protectionof natural and physical resources in a way, or at a rate,which enables people and communities to provide for theirsocial, economic and cultural well-being and for theirhealth and safety while:

- Sustaining the potential of natural and physicalresources.to meet the reasonably foreseeable needsof future generations;

- Safeguarding the life-supporting capacity of air,water, soil and ecosystems; and

- Avoiding, remedying, or mitigating any adverseeffects on the environment.’

All spokespeople believed their businesses wereoperated with sustainable management in mind andthe definitions of sustainable management stated,although varied, appeared to reflect this. Although there

was a large variation in definitions, each spokespersonwas able to identify at least one TBL element of theRMA definition.

There was no clear division between the systems as towhether the fundamental focus of the business wasenvironmental, social or economic sustainability. Thiswas reflected by the majority of spokespeople, whobelieved their businesses had a combination of econom-ic, social and environmental elements.

4.4.2. Important environmental issues in New ZealandAs with other environmental issues in New Zealand

water, soil and spray drift issues are largely governed bythe RMA with the result that regional/district councilsundertake administration and enforcement.

With the exception of one spokesperson, all peoplesurveyed believed that water, soil and spray drift areserious environmental issues in New Zealand that arenot being well managed either collectively by a region orindividually by a business. This result is supported bya recent study on public perceptions of the New Zealandenvironment, that is, quantitative data indicate that thestate of some of New Zealand’s key natural resourcesand environment is often acceptable, however, publicperception of the same is often not in agreement with thedata [4]. The Australian wine industry identifies five coreenvironmental issues that have the potential to threatenand undermine their industry: water, waste, land-use,greenhouse (gases), and (impacts upon) community [33].

4.4.3. New Zealand environmental legislationand policy

The issue of environmental legislation and its effecton the New Zealand wine industry was raised in thesurvey with particular regard to whether or not NewZealand environmental legislation was appropriate withregard to viticulture and winemaking.

Given the growing importance of the wine industry toNew Zealand, the country lags somewhat behindAustralia in relation to policy development, where anenvironment specific wine industry strategy was pro-duced in 2002 [33]. The Australian industry’s targetfigure of annual wine sales is unlikely to be reachedunless natural resources are managed sustainably [33].Evidence of recent non-compliance by local winemakerswith regional rules and resource consents [15] indicatesthat New Zealand’s wine market could suffer econom-ically.

While voluntary adoption of environmental systemsis promising, it will never completely eliminate the needfor rigorous government oversight [34], because whendealing with environmental affairs the invisible hand ofthe market fails to align the interests of the individual orcompany with those of the society at large [35]. With theright balance of incentive based and legislation-based

1184 K.F.D. Hughey et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (2005) 1175e1187

control, governments could promote the uptake of ‘ems’and thus aid proactive sustainable management [36].

The purpose of the RMA is to promote the sustain-able management of natural and physical resources [37].Under the premise of this act’s basis of effects-basedplanning, a company can demonstrate a minimisation ofeffects while the activity itself is not sustainable [14].

Bio-Gro stakeholders actively oppose the introduc-tion of genetically modified crops and livestock toprotect them from GM contamination, thus ensuringNew Zealand organic products retain their integrity andcontinue to receive top premiums overseas [26]. Withconsumer trends towards ‘environmentally friendly’products, introduction of GM to New Zealand mayharm the clean green image, something the small NewZealand economy may not be able to buffer.

The Bio-Gro and ISO 14001 companies surveyed onthe whole appeared not to have major concerns incontrast to SWNZ companies who stated that the RMAwas unworkable, expensive and time consuming.

The common response regarding a tightening of NewZealand environmental legislation was that there wouldbe no effect on any of the businesses surveyed. Eachbusiness believed they were acting proactively to avoidany penalty if the legislation concerning the environ-ment were to become stricter.

4.4.4. New Zealand environmental practices comparedto other wine-producing countries

All of the respondents considered New Zealand’senvironmental practices to be ‘middle of the road’ orslightly better than other wine-producing countries. This‘middle of the road’ attitude is consistent with surveysconducted by Hughey et al. [38,39], who found that ingeneral New Zealanders believe that the quality of ourenvironment is very good to good and is being wellmanaged compared to other developed countries.

5. Discussion and policy implications

5.1. New Zealand wine and EMS

The results of this comparative study indicate that noone ‘ems’ is better than the other but any comparisondepends on how the systems have been measured andwhat criteria they have been measured against. Alimitation of this research was the lack of quantitativebiophysical indicator data against which to makea biophysically-based scientific comparison among thethree systems. Such data could have taken three years togather and would have consumed enormous financialand human resources. Lack of such data meansconclusions drawn from the study are tentative andthe policy implications need to be considered verycarefully. Conversely, an advantage of this research was

that financial and human resources were not stretchedand, moreover, that some policy insights could be drawnrelatively quickly based on the experiences of thoseimplementing the different systems.

The key factor affecting the performance of the threesystems examined appears to be whether the system isgoal or process orientated. The goals of Bio-Gro andSWNZ have been designed to apply to the current issuesaffecting the New Zealand wine industry. On the otherhand, those companies adopting ISO 14001 have no setgoals they must adhere to, although there is theflexibility to address broad ranging issues when operat-ing under this system.

Evaluation against key TBL criteria appears toindicate that SWNZ accredited companies are achievingthe most environmentally and socially system comparedto the other systems, however, for factors intrinsic toorganic production, Bio-Gro is the most successful. Noattempt was made to determine which system providesthe best economic returns. However, while Bio-Groappears to be having the biggest marketing impact, whatis surprising is the lack of attention paid by thecompanies to marketing the benefits that accrue fromthe individual systems they have implemented. Bio-Grois obviously the system of choice if a company wishes topractice organic winegrowing. With respect to ‘other’benefits experienced, SWNZ is showing the greatestrewards, and it is important that these ‘other’ benefitsare considered when choosing a system.

From all the other system and industry issuesexamined, there appears to be no clear-cut ‘whichsystem is best’ result and which system best fits intothe context of the New Zealand wine industry. Theseissues include legislation, marketing/export, resourceissues and promotion of the clean and green image.System cost and voluminous paperwork are disadvan-tages for ISO 14001 and Bio-Gro, however, withoutthese requirements, the systems would not be able toeffectively evolve for lack of research and information.

The initial idea to promote SWNZ and ISO 14001together is perhaps the most effective way to achievesustainability by a purely ‘ems’ approach and isconsistent with the sort of framework proposed byRobert et al. [10]. With the process oriented nature ofISO 14001 and the goal-oriented nature of SWNZa complementary relationship between the two systemscan be developed. With the help of the ISO 14001framework, a company can utilise the wine industryspecific goals of SWNZ and determine the best route ofreaching these. The use by some of the wineries surveyedwho used both the ISO 14001 and SWNZ systemsindicated there is clearly potential for setting ofperformance targets while simultaneously providinga conformance framework.

Complementing the management systems evaluatedhere by integrating TBL reporting potentially strengthen

1185K.F.D. Hughey et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (2005) 1175e1187

the process and appear to be the most effective way ofpromoting sustainability in the New Zealand wineindustry as a whole. However, the accountability ofISO 14001 is subject to debate as all environmentalinformation prepared by an ISO 14001 certifiedcompany is confidential and unavailable to governmentbodies, workers and the public [19]. Therefore, for anISO 14001 company to be truly accountable it mustreport its progress to its stakeholders, who includeworkers, shareholders, and community members. Tothis end, Palliser Wines (a Living Wine group member)is the first ISO 14001 accredited wine business in NewZealand to have produced both a TBL and an ‘ems’performance report [40].

In spite of the winegrowing industry’s generallyproactive environmental positioning, legislation ruledand enforced standards could be introduced. A recentrecord of significant and persistent non-compliance withconsent conditions in the industry has ramifications suchas a more regulatory approach being adopted by localcouncils, a situation the industry would wish to avoid[41,15]. Also, legislation such as the RMA could beamended to require winegrowers to adopt an ‘ems’ fromthe outset, thus making sustainability and the environ-ment important considerations in the minds of companystakeholders. The survey respondents did not opposefurther legislative requirements from being imple-mented.

New Zealand wine is promoted by WINZ as ‘theriches of a clean green land’ [5]. As a positioningstatement supporting international marketing strategies,this slogan is not intended to be an absolute or definitiveclaim about the environment in which New Zealandgrapes and wines are produced; rather it is based on theconcept or image of the New Zealand environment [17].Goldberg [36] argues, however, that if a slogan is to beused in such a manner, then the wine industry will needto substantiate its claims. The results from this studyindicate a high level of commitment to the ‘ems’ beingimplemented, and the high level of industry participa-tion gives some confidence that in the medium termthese claims might be able to be supported.

5.2. The broader Australasian policy context

The future development and growth of the NewZealand wine industry is highly dependent upon thegrowth in exports [42], therefore it is important for theindustry to monitor international trends and cater tothese accordingly. The New Zealand wine industry isgetting ‘‘ticks in the boxes’’, measured by a burgeoninginternational reputation for its wines and the industryembracing sustainable, largely voluntary, environmentalmanagement practices. New Zealand’s ParliamentaryCommissioner for the Environment [43] recently com-mented on a changing emphasis from unsustainable

growth to sustainable development. His words are aptfor the positive developments being made in the NZwine industry: ‘‘.emphasis should be shifted to de-velopment that improves.produces less waste, addsmore value to goods and services, and manages ina sustainable way.’’.

For example, integrated environmental management(IEM) can be used as an approach to coordinate,proactively or preventively, measures that maintain theenvironment for long-term sustainable use [44]. TheAustralian wine industry has recognised that a morecoordinated approach is necessary for environmentalmanagement in order to formulate policy and addresspriority environmental issues [33]. In order to counteractenvironmental threats (such as bio-security and climatechange) to New Zealand’s economy and ecosystems, itwould seem prudent for local wine industry stakeholders(such as producers, consumers, support industries andgovernment) to adopt an IEM approach to ensurefuture sustainability of the wine industry.

The core objectives contained in the Australian WineIndustry’s Environment Strategy [33] could equally beapplied to the New Zealand context given the close linksbetween the countries’ wine industries. In spite of thedifferences between the ‘ems’ chosen and philosophicaldifferences between winery groupings, there are positiveindications that the New Zealand wine industry isheading down a sustainable pathway and reinforcingthe country’s clean green image. A growing number oforganisations worldwide are addressing sustainable de-velopment as a key strategic business issue [45]. NewZealand has arguably made limited progress towardsembracing the international developments of sustain-ability [46,43], however, these concerns are beginning tobe addressed in industry in general in New Zealandmeasured by the increase in ‘sustainable development’reporting [47]. Given the close economic links betweenNew Zealand and Australia, and the recent adoption ofan environmental wine strategy by the Australian wineindustry [33], the New Zealand wine industry couldconsider formally adopting a similar concept to ensuresustainability of the industry and to maintain, or better,their share of the Australasian wine export market. Suchan approach, allied to Triple Bottom Line reporting,would complement the already widespread adoption ofa diversity of environmental management systems withinthe New Zealand wine industry.

6. Conclusions

A key question must be posed about this study e isqualitative research appropriate for a comparativeevaluation of different environmental managementsystems operating in a particular industry? If up-to-dateand easily collectable perception data that might be of

1186 K.F.D. Hughey et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (2005) 1175e1187

use to policy makers and industry advisors is requiredthen this approach works. The downside of thisapproach is a lack of quantitative biophysical scientificsupport for some of the findings which would only beavailable after a detailed, multi-year study. Despite thisdownside, the approach has clearly provided insightsinto comparative ‘ems’ performance.

The findings from this study of ‘ems’ in the NewZealand wine industry are somewhat equivocal. Avariety of systems is being implemented for a variety ofreasons. Sometimes, for example, for Bio-Gro accreditedcompanies, the focus is clearly on wide ranging principlesof environmental sustainability, whereas for SWNZ it isto better manage pre-identified key environmentalpriorities. ISO 14001 companies have wider interestsand see marketing advantages. When evaluated againstTBL criteria all three systems have a range of benefits.So, which system is best? The answer, as shown in Robertet al. [10] maybe that none of those evaluated in thisstudy, in that different systems have appropriatelydifferent purposes. If a notion of sustainability is to bepromoted therefore, a broader industry wide strategy,like that developed and promoted in Australia, isrequired and vineyards can choose the system or systemsthat best meets the aim of such a strategy.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms Tessa Renton, NationalCoordinator for Sustainable Winegrowing New Zealandfor her helpful suggestions and knowledge concerningwine industry details. We would also like to thank the 15winegrowers who participated in the original survey in2001.

References

[1] APEC. The impact of liberalisation: communicating with APEC

communities: wine industry in New Zealand. Singapore: APEC

Secretarial; 1998.

[2] Cooper M. The wines and vineyards of New Zealand. Auckland:

Hodder Moa Beckett Publishers Limited; 1996.

[3] Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Review of wine legislation:

MAF public discussion paper no. 22. Wellington, NZ: MAF;

2000.

[4] Hughey KFD, Cullen R, Kerr GN, Cook A. The pressure-state-

response model and perceptions reporting in New Zealand:

perceptions of the New Zealand environment. Journal of

Environmental Management 2004;70:85e93.

[5] Wine Institute of New Zealand. New Zealand winegrowers annual

report. Auckland: The Wine Institute of New Zealand; 2002.

[6] Parkyn S, Matheson F, Cooke J, Quinn J. Review of the

environmental effects of agriculture on freshwaters. NIWA report

FGC02206 to fish and game New Zealand, Hamilton: National

Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research; 2002.

[7] Hansford D. Are we reaching the bottom of the bucket? New

Zealand Environment 2003;24:10e2.

[8] Reedman P. Environmental component of consumer perceptions

in the UK market. In: Blair R, Williams P, Høj P, editors.

Proceedings of the Eleventh Australian Wine Industry Technical

Conference, Adelaide, 7e11 October 2001. Glen Osmond:

Australian Wine Industry Technical Conference Inc.; 2001.

[9] Hughey KFD, Luttrell K, Nichols L, Cullen R. An overview of

key voluntary environmental management systems available to

businesses in New Zealand. Unpublished report to Ministry for

the Environment. Environment, Society and Design Division:

Lincoln University; 2002.

[10] Robert K-H, Schmidt-Bleek B, Aloisi de Landerel J, Basile G,

Jansen JL, Kuehr R, et al. Strategic sustainable development eselection, design and synergies of applied tools. Journal of Cleaner

Production 2002;10:197e214.

[11] MacDonald JP. Strategic sustainable development using the ISO

14001 standard. Journal of Cleaner Production 2004 (online at

www.sciencedirect.com, accessed 22 June 2004).

[12] Elkington J. The Triple Bottom Line. Sustainability’s account-

ants. In: Elkington J, editor. Cannibals with forks e The Triple

Bottom Line of 21st century business. Canada: New Society

Publishers; 1998.

[13] Manktelow D, Renton T, Gurnsey S. Technical developments in

Sustainable Winegrowing New Zealand. Proceedings of Romeo

Bragato Conference, Christchurch, 12e14 September 2002.

[14] Hoksbergen T. IWP e benefits both home and abroad. New

Zealand Winegrower Spring 2000;27e30.

[15] Renton T, Manktelow D, Kingston C. Sustainable winegrowing:

New Zealand’s place in the world. Proceedings of Romeo Bragato

Conference, Christchurch, 12e14 September 2002.

[16] Basler P, Boller E. Guidelines for integrated production in

viticulture. Wadenswil, Switzerland: Fachgruppe integrierte Pro-

duction des Schweiz Weinbauvereins (FIPW); 1991.

[17] Jordan D. Sustainable viticulture schemes. Report for Wine-

growers of New Zealand. Vine to Wine, Wellington; 1995.

[18] Wine Institute of New Zealand. Sustainable wine New Zealand

manual. 4th ed. Auckland: The Wine Institute of New Zealand;

2002.

[19] Gleckman H, Krut R. Neither international nor standard: the

limits of ISO 14001 as an instrument of global corporate

environmental management. In: Sheldon C, editor. ISO 14001

and beyond: environmental management systems in the real

world. Sheffield: Greenleaf; 1997.

[20] Darnall N, Rigling Gallagher D, Andrews RNL, Amaral D.

Environmental management systems: opportunities for improved

environmental and business strategy. Environmental quality

management: Wiley Publishers; 2000. (retrieved December 2000

from the World Wide Web: http://www.eli.org/pdf/eqm.pdf).

[21] Christie R. Foreword. In: Roberts Lin, editor. ISO 14001: envi-

ronmental management system manual. Wellington: TradeNZ;

1996.

[22] Roberts L. ISO 14001: environmental management system

manual. Wellington: TradeNZ; 1996.

[23] Riddiford R. Market perception of environmental issues: what are

the market drivers? Proceedings of Romeo Bragato Conference,

Christchurch, 12e14 September 2002.

[24] Hamner B. Waste reduction: the cost effective approach to

ISO 14001 compliance. In: Tibor T, Feldman I, editors. Imple-

menting ISO 14000: a practical, comprehensive guide to the ISO

14000 environmental management standards. Chicago: Irwin;

1997.

[25] Clausen J, Keil M, Jungwirth M. The state of EMAS in the EU:

eco-management as a tool for sustainable development: literature

study. Berlin: Institute for Ecological Economy Research and

Ecologic Institute for International and European Environmental

Policy; 2002.

[26] BIO-GRONew Zealand. Organic Orchards & Tree Crops: a guide

for New Zealand growers considering conversion to organic

1187K.F.D. Hughey et al. / Journal of Cleaner Production 13 (2005) 1175e1187

production of fruit and tree crops. Wellington, NZ: BIO-GRO

Technical Advisory Division; 2000.

[27] Riddiford R. ISO 14001 and the Living Wine Group. In: Blair R,

Williams P, Høj P, editors. Proceedings of the Eleventh

Australian Wine Industry Technical Conference, Adelaide, 7e11October 2001. Glen Osmond: Australian Wine Industry Technical

Conference Inc; 2001.

[28] Renton T. National Coordinator, Sustainable Wine New

Zealand. Personal comment. February 2003.

[29] Berry MA, Rondinelli DA. Proactive corporate environmental

management: a new industrial revolution. Academy of Manage-

ment Executive 1998;12(2):38e50.[30] Botry Zen Limited. New Zealand stock exchange listing profile.

Dunedin, NZ: Botry Zen; 2002.

[31] Burns S. A compass for environmental management systems. In:

Nattrass B, Altomare M, editors. The natural step for business:

wealth, ecology and evolutionary corporation. Canada: New

Society Publishers; 1999.

[32] Emilsson S, Hjelm O. Implementation of standardised environ-

mental management systems in Swedish local authorities: reasons,

expectations and some outcomes. Environmental Science and

Policy 2002;5:443e8.

[33] Jones K. Sustaining success: the Australian wine industry’s

environment strategy. Adelaide: South Australian Wine and

Brandy Industry Association; 2002.

[34] Davis GA, Wilt CA, Barkenbus JN. Extended product re-

sponsibility: a tool for a sustainable economy. Environment

1997;39(7):10e15, 16e38.

[35] Cairncross F. Where governments fail. In: Cairncross F, editor.

Costing the earth: the challenge for governments, the opportuni-

ties for business. Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press;

1992.

[36] Goldberg E. Profit, people, planet. Policy issues and options

around triple bottom line reporting. Wellington: Ministry for the

Environment; 2001.

[37] Ministry for the Environment. CompanyEnvironmental PolicieseGuidelines for development and Implementation. Prepared by

Works Environmental Management. Ministry for the Environ-

ment: Wellington, 1993.

[38] Hughey KFD, Kerr GN, Cullen R, Cook A. Perceptions of the

state of New Zealand’s environment e findings from the first

biennial survey undertaken in 2000. Canterbury: Lincoln Univer-

sity; 2001.

[39] Hughey KFD, Kerr GN, Cullen R. Perceptions of the state of the

environment: the 2002 survey of public preferences & perceptions

of the New Zealand environment. Lincoln: Education Solutions;

2002.

[40] Palliser Estate Wines of Martinborough Ltd. Annual report for

the year ended 30th June 2002. Martinborough, NZ: Palliser

Estate Wines; 2002.

[41] Andrew R. Clean, green and sustainable. The Australian and New

Zealand Grape grower and Winemaker 109e111, November

2002.

[42] Young-Cooper AF. Discussion paper on the wine industry and

a resource management strategy for New Zealand. Auckland: The

Wine Institute of New Zealand; 1994.

[43] Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. Creating our

future: sustainable development for New Zealand. Wellington:

PCE; 2002.

[44] Cairns Jr J. The need for integrated environmental systems man-

agement. In: Cairns Jr J, Crawford TV, editors. Integrated envi-

ronmental management. Chelsea, MI: Lewis; 1991. Chapter 2.

[45] Holliday Jr CO, Schmidheiny S, Watts P. Walking the talk: the

business case for sustainable development. Sheffield: Greenleaf

and Berret-Koehler; 2002.

[46] Chapman R. Ideas percolate slowly into New Zealand. Future

Times 4, 3e5. Wellington, NZ: New Zealand Futures Trust, 2002.

[47] Ministry for the Environment. Triple bottom line reporting in the

public sector: summary of pilot group findings. Wellington:

Ministry for the Environment; 2002.