reported case laws and/or previous litigation experience of ...

Prospective study of self-reported usual snacking and weight gain in a Mediterranean cohort: The SUN...

Transcript of Prospective study of self-reported usual snacking and weight gain in a Mediterranean cohort: The SUN...

lable at ScienceDirect

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Clinical Nutrition xxx (2009) 1–8

YCLNU1533_proof � 7 September 2009 � 1/8

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

Contents lists avai

Clinical Nutrition

journal homepage: ht tp: / /www.elsevier .com/locate/c lnu

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

OOF

Original Article

Prospective study of self-reported usual snacking and weight gainin a Mediterranean cohort: The SUN project

Maira Bes-Rastrollo a,*, Almudena Sanchez-Villegas a,b, Francisco J. Basterra-Gortari a,c,Jorge M. Nunez-Cordoba a, Estefanıa Toledo a,d, Manuel Serrano-Martinez a

a Dept. of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Medical School-Clinica Universitaria, University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spainb Dept. of Clinical Sciences, University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spainc Dept. of Endocrinology, Hospital of Navarra. Pamplona, Spaind Dept. of Preventive Medicine and Quality Management, Hospital Virgen del Camino, Pamplona, Spain

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:Received 12 January 2009Accepted 26 August 2009

Keywords:Eating frequencyDietObesitySnacksLongitudinalCohort

U

* Corresponding author. Dept. Preventive Medicineof Navarra, C/Irunlarrea 1, Ed. Investigacion, 31008Tel.: þ34 948425600x6602; fax: þ34 948425649.

E-mail address: [email protected] (M. Bes-Rastrollo).

0261-5614/$ – see front matter � 2009 Elsevier Ltd adoi:10.1016/j.clnu.2009.08.017

Please cite this article in press as: Bes-RastroClinical Nutrition (2009), doi:10.1016/j.clnu.

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

RECTEDPRs u m m a r yBackground & aims: It has been hypothesized that snacking could be a major factor in the development ofobesity. However, the relationship between snacking and the increment in body weight remainscontroversial. Moreover, longitudinal studies about this issue are scarce. Thus, our objective was toprospectively assess the relationship between snacking and weight gain and obesity in a middle-agedfree-living population.Methods: Longitudinal prospective Spanish dynamic cohort (10,162 university graduates; mean age:39 years) followed-up for an average of 4.6 years. Dietary habits were ascertained through a validated136-item food-frequency questionnaire. Usual snackers were defined as those participants whoanswered affirmatively when asked in the baseline assessment if they usually eat between meals.Validated self-reported weight and body mass index were collected at baseline and during follow-up.Results: After adjusting for potential confounders, self-reported between-meal snacking was significantlyassociated with a higher risk of substantial weight gain (�3 kg/year; p< 0.001;� 5 kg/year,p< 0.001;� 10% baseline weight, p< 0.001). Among participants with a baseline body mass index lowerthan 30 kg/m2 (n: 9709) we observed 258 new cases of obesity. Usual snackers presented an adjusted66% higher risk of becoming obese during follow-up (Hazard Ratio: 1.69; 95% confidence interval:1.30–2.20).Conclusion: Our results support the hypothesis that self-reported between-meal snacking can bea potential risk factor for obesity.

� 2009 Elsevier Ltd and European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism.

8990

91

R92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

NCO1. Introduction

Obesity has become an important Public Health problemworldwide. The number of obese people has increased over theyears. By 2025, according to the World Health Organization, it isexpected that 2.3 billion adults will be overweight and more than700 million will be obese around the world, with all the adversehealth and economic consequences associated with being over-weight and obese.1

and Public Health, UniversityPamplona (Navarra), Spain.

nd European Society for Clinical N

llo M, et al., Prospective study2009.08.017

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

Since the prevalence of obesity has increased more rapidly thanthe human genotype has changed, it is unlikely that the obesityepidemic could be explained entirely through genetic influencesEnvironmental conditions are probably the main factor responsiblefor the increased prevalence of obesity. Thus, it has been hypoth-esized that a major factor in the development of obesity2 could belifestyle pattern changes with increased snacking and decreasedstructured meals. This explanation can also be applicable even incountries undergoing the nutrition transition.3 The prevalence ofobesity has risen at the same time that snacking habits haveincreased. Snack food makes up a large proportion of the averagediet in developed countries. Adults in the USA consumed 17.7% oftheir daily total energy intake from snacks, which were approxi-mately equivalent to 350 kcal/day.4 Snacking has become increas-ingly popular even in countries in the Mediterranean area. In thelast 5 years, snack sales have gone up by 57% in Italy and 58% in

utrition and Metabolism.

of self-reported usual snacking and weight gain in a Mediterranean...,

109

110

E

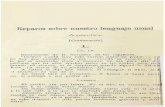

20,095

1,889 lost to follow-up(88% retention rate)

13,853

Extreme caloric intake (n=1,365)Following a special

diet (n=981)

Pregnant (n=1,069)Missing values in snacking (n=168)

Missing values in covariables (n=108)

10,162

15,742 elegible for longitudinalanalyses

Fig. 1. Flowchart on the study population.

M. Bes-Rastrollo et al. / Clinical Nutrition xxx (2009) 1–82

ARTICLE IN PRESS YCLNU1533_proof � 7 September 2009 � 2/8

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

UNCORRECT

Spain, while they increased by 18% in the UK.5 Portuguese youthaged 5–15 years consumed 1.5 snacks per day and the number ofsnacks increased across all age groups between 1995 and 1996 and1998–1999.6 Similarly, based on the food consumption trendsobserved in Catalonia, a region of Spain, between-meal snackingincreased from 9% to 36% during the periods between 1992 and1993 and 2002–2003.7

Snack foods tend to be energy dense and of little nutritionalvalue. In a recent study among Finnish adults, food items typicallyconsumed as snacks were reported to be high in energy densitysuch as sweet bakery goods, sweets, and chocolate.8 Similarly,popular snack choices among US children and adolescents includeenergy-dense items such as cakes, cookies and savoury snacks.9

Thus, the potential effect of between-meals snacking on obesitycould be driven by an extra energy intake. Current literature showsthat subjects do not compensate energy intake after snacking,especially for those snacks consumed on an irregular basis.10

The discouragement of unstructured eating episodes in thepromotion of healthy lifestyles could be a point to consider in thecontext of the public health strategies to tackle the obesityepidemic. However, the relationship between snacking and bodyweight remains controversial and the results are not consistentacross studies, as the majority are cross-sectional and mainly con-ducted among children and adolescents.11–20

To our best knowledge, the studies carried out so far in theMediterranean region have been cross-sectional15,16,20 orconducted among children.12 Furthermore, since almost allprevious longitudinal studies on this topic have been carried out inAnglo-Saxon countries, particularly in the US,11,14,17–19 and giventhe enormous differences in dietary patterns between regions, forinstance between the Mediterranean and those of Northern Europeor North America, the influence of snacking could vary betweenpopulations.

Consequently, the objective of this study was to assessprospectively the relationship between self-reported snacking andweight gain and obesity in a Spanish middle-aged free-livingpopulation of university graduates: the SUN project.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

The SUN project (Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra–University of Navarra Follow-up-) is a multi-purpose prospectivecohort study designed to establish associations between diet andthe occurrence of several diseases and chronic conditions includingobesity. Information is collected through self-administered ques-tionnaires sent by mail every 2 years. The objectives and methodsof this project have been detailed elsewhere.21

The recruitment of participants, all of them university gradu-ates, started in December 1999. It is permanently open because ofthe design. By June 2008 the dataset of the SUN Project included20,095 participants. Those participants who completed a baselineassessment (Q0) before September 2005 were eligible for longitu-dinal analyses (n¼ 15,742). Among them, 1889 did not answer anyof the follow-up questionnaires, and after 5 more bimonthlymailings, they were considered lost to follow-up. Therefore, weretained 13,853 participants (88%). Following the recommenda-tions for conducting analyses in nutritional epidemiology,22

participants who reported extreme (low or high) values for totalenergy intake (<800 kcal/day for men, <500 kcal/day for womenor >4000 kcal/day for men, >3500 kcal/day for women; n¼ 1365)were excluded. Those participants who followed a special diet (i.ehipocaloric diet, low-cholesterol diet, low-fat diet, low-salt diet)were also excluded (n¼ 981), as well as those female participants

Please cite this article in press as: Bes-Rastrollo M, et al., Prospective studyClinical Nutrition (2009), doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2009.08.017

DPROOF

who were pregnant at baseline or during follow-up (n¼ 1069).Thus, no pregnant women remained in the final sample. We alsoexcluded those without information on snacking (n¼ 168) andwith missing values in covariables of interest (n¼ 108). Finally, datafrom 10,162 participants were available for the analyses (Fig. 1).

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at theUniversity of Navarra. Informed consent was implied by thevoluntary completion of the baseline questionnaire.

2.2. Assessment of diet and definition of snacking

Dietary habits were ascertained through a baseline semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) that had beenpreviously validated in Spain.21

The questionnaire was based on typical portion sizes and hadnine options for the average frequency of consumption of 136 fooditems in the previous year (ranging from never/almost never to atleast six times per day).

We defined as usual snackers those participants who answeredaffirmatively to the following question: ‘‘Do you usually eat betweenmeals (snacking)?’’ With only two possible answers: Yes/No.

Nutrient intake scores were computed using an ad hoccomputer program (statistic program developed specifically for thispurpose based on the answered frequency of consumption,portions and food composition tables). A trained dietician updatedthe nutrient data bank using the most recently updated Spanishcomposition tables.23,24 Fast-food was defined as the sum (gramsper day) of hamburgers, sausages, and pizza consumption evalu-ated through the FFQ.

2.3. Assessment of non-dietary variables

The baseline assessment also included other questions (46 itemsfor men and 54 for women) to assess medical history, health habits,and lifestyle and sociodemographic variables. Participants wereclassified as non-smokers, former smokers, or current smokers.

of self-reported usual snacking and weight gain in a Mediterranean...,

E

M. Bes-Rastrollo et al. / Clinical Nutrition xxx (2009) 1–8 3

ARTICLE IN PRESS YCLNU1533_proof � 7 September 2009 � 3/8

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

RRECT

Physical activity was ascertained through a baseline question-naire. The metabolic equivalent (MET) index per week wascomputed using the time spent engaging in 17 activities multi-plying by the MET score specific for each activity. A MET score of anactivity is defined as the ratio of the metabolic rate associated withthis activity divided by the resting metabolic rate (sitting quietly).25

The MET-hours for all activities were combined to obtain a value oftotal weekly MET-hours, which adequately correlated with energyexpenditure measured by a triaxial accelerometer in a validationsubsample of the cohort.21

2.4. Assessment of the outcome

Participants’ weight was recorded at baseline and every twoyears during follow-up. The reliability and validity of self-reportedweight was previously assessed in a subsample of the cohort beinghighly correlated with directly measured weight (r¼ 0.99) andwith a mean relative error in self-reported weight of �1.45%.21

Body mass index (BMI), defined as weight (in kg) divided by thesquare of the height (in meters) was ascertained in the baselinequestionnaire and during follow-up carrying forward the heightvalue obtained in the baseline questionnaire.

The outcomes were 1) change in body weight per year asa continuous variable, 2) substantial weight gain defined as anincrement of at least 3 kg per year during follow-up, and 3) incidentobesity (participants who had a BMI value< 30 kg/m2 at baselineand achieved a BMI� 30 kg/m2 during follow-up).

2.5. Statistical analyses

Least-squares regression models were used to evaluate theassociation between snacking and weight change per year duringfollow-up. We used analyses of covariance to adjust the subsequentaverage weight change per year for potential confounders. Ina second analysis, non-conditional logistic regression models werefit to assess the relationship between snacking and an increment ofweight of at least 3 kg per year. We repeated the analyses using anincrement of at least 5 kg per year or an increment of 10% of baselineweight as the outcomes. Odds Ratios (OR) and their 95% confidenceintervals (CI) were calculated considering non-snacker participantsas the reference category. We also conducted the analyses stratifyingby baseline BMI categories (underweight<18.5 kg/m2, normal weight:18.5 –<25 kg/m2, overweight: 25–<30, and obese: �30 kg/m2).

We conducted multivariate Cox’s regression analyses to assessthe association between snacking and the risk of incident obesity(BMI� 30 kg/m2) after excluding obese participants at baseline

UNCO

Table 1Baseline descriptive characteristics of the SUN cohort study according to snacking.

Eligible population Final population

n 15742 10162Women (%) 59% 54%Age (years) 38 (0.09) 39 (0.11)Weight (kg) 69 (0.08) 69 (0.09)BMI (kg/m2) 23.8 (0.02) 23.8 (0.03)TV viewing (h/day) 5.4 (0.03) 5.4 (0.04)Sitting (h/day) 5.8 (0.02) 5.8 (0.02)Physical activity (METs-h/wk) 25.3

(0.18)24.6(0.21)

SmokingSmokers 24% 23%Ex-smokers 28% 29%

Continuous variables are expressed as means (standard error) adjusted for age and sex andcompared through a Ji-squared test.

Please cite this article in press as: Bes-Rastrollo M, et al., Prospective studyClinical Nutrition (2009), doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2009.08.017

DPROOF

(n¼ 453). Duration of follow-up was calculated as the intervalbetween the return of the baseline questionnaire and the diagnosisof obesity (date of completion of the followed-up questionnairewhen the participant was first measured to have a BMI� 30 kg/m2),death, or last answered questionnaire, whichever occurred first. Wealso converted hazard ratios to rate advancement period (RAP)proposed by Brenner et al.26

To test multicollinearity between variables we used the toler-ance and its reciprocal the variance inflation factor (FIV).

According to the current recommendations related to theselection of potential confounders in a multivariate model,27 wetook into account the previously published scientific literatureincluding our own results based on the cohort about risk factor forobesity, avoiding exclusively the statistic approach as the p value,the stepwise procedures or the changes in the point estimates afteradjusting for potential confounders. It has been demonstrated thatthese kinds of strategies may lead to invalid results. In addition, weadjusted for smoking habits, a variable strongly related to life styleto help to control confounding. In this context, all the analyses wereadjusted for age, sex, physical activity, smoking, TV viewing, sittinghours, baseline BMI, fast-food consumption, sugar-sweetened softdrinks consumption, alcohol, fiber and total energy intake. Inadditional multivariate models we also adjusted for changes duringfollow-up in physical activity, smoking habits, and in theconsumption of meats and fruit/vegetables.

We also conducted sensitivity analyses excluding those partic-ipants with chronic disease (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, andcancer) at baseline or during follow-up.

Analyses were performed with SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc,Chicago, IL). All p values presented are two-tailed; p< 0.05 wasconsidered statistically significant.

3. Results

The mean follow-up of participants was 4.6 years (median¼ 4.4years). The mean weight increment per year during follow-up was141 g (95% CI: 121–161) among 10,162 participants with a mean ageof 39 years (SD: 12) in the SUN cohort. Thirty-four percent ofparticipants in the cohort self-reported between-meal snacking atthe baseline assessment (38% in the eligible population).

Two hundred fifty-eight participants initially free of obesity metthe criteria for incident obesity (BMI� 30 kg/m2) during follow-up.The overall cumulative incidence of obesity in this population was2.7% during the follow-up period.

Table 1 shows the descriptive characteristics of the SUN cohortparticipants according to snacking and sample characteristics.

Non-snackers Usual Snackers p value fornon-snackers versususual snackers

6704 345850% 62% <0.00140 (0.14) 37 (0.20) <0.00168 (0.03) 71 (0.04) <0.00124 (0.04) 24 (0.05) <0.0015.4 (0.04) 5.2 (0.06) 0.0036 (0.02) 6 (0.03) 0.19125 (0.26) 24 (0.37) 0.111

<0.00123% 23%31% 26%

compared through ANCOVA. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and

of self-reported usual snacking and weight gain in a Mediterranean...,

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

EDPROOF

Table 2Baseline nutrients and food consumption according to snacking (n¼ 10,162).

Non-snackers(n¼ 6704)

Usual snackers(n¼ 3458)

p value

NUTRIENTSTotal energy intake (kcal/day) 2364 (7) 2455 (11) <0.001Carbohydrate intake (% of

Energy)43.7 (0.09) 43.1 (0.13) 0.001

Protein intake (% of energy) 17.9 (0.04) 17.7 (0.06) 0.001Fat intake (% of energy) 36.2 (0.08) 37.0 (0.11) <0.001

SFA (% of energy) 12.5 (0.04) 12.8 (0.05) <0.001MUFA (% of energy) 15.5 (0.05) 15.8 (0.06) <0.001PUFA (% of energy) 5.2 (0.02) 5.4 (0.03) <0.001

Glycemic load 182 (0.82) 185 (1.17) <0.001Alcohol intake (g/day) 7.4 (0.13) 7.4 (0.18) 0.933Fiber intake (g/day) 26.8 (0.14) 26.5 (0.20) 0.349

FOODFruits and vegetables (g/day) 826 (6) 807 (8) 0.053Nuts (g/day) 6.9 (0.1) 7.6 (0.2) 0.003Biscuits 19.3 (0.3) 20.3 (0.5) 0.127Pastries and bakery

(non-handmade) (g/day)14.4 (0.3) 16.6 (0.4) <0.001

Chocolates/cakes (g/day) 16.4 (0.2) 22.2 (0.4) <0.001Sugar-sweetened beverages

(g/day)56.4 (1.4) 69.2 (2.2) <0.001

Fruit juices (g/day) 88.5 (1.5) 86.8 (2.2) 0.545Alcoholic beverage (g/day)s 105.2 (1.9) 103.3 (2.7) 0.555Fast-food* (g/day) 20.3 (0.2) 21.8 (0.3) <0.001Processed meat (g/day) 42.5 (0.4) 47.3 (0.5) <0.001Chip potatoes (g/day) 27.9 (0.4) 29.1 (0.5) 0.081

Variables are expressed as means (standard error) adjusted for age, sex, and baselinebody weight and compared through ANCOVA.SFA: Saturated Fatty Acids, MUFA: Monounsaturated Fatty Acids, PUFA:Polyunsturated Fatty Acids.*Fast-food was the sum of hamburgers, sausages and pizza consumption.

Table 3Average (95% confidence interval) weight change (g/year) during follow-upaccording to snacking in the SUN Cohort Study (n¼ 10,162).

Non-snackers Usual Snackers p value

Crude weight change(g/year)

119 (95–142) 184 (147–222) 0.003

Age- and sex-adjustedweight change (g/year)

126 (101–151) 169 (133–204) 0.06

Multivariatea adjustedweight change (g/year)

131 (94–168) 188 (143–233) 0.01

Multivariateb adjustedweight change (g/year)

136 (62–208) 196 (121–271) 0.006

Results from all the variables included in the multivariatea model

Multivariatea adjusted ß (95% CI)regression coefficient (g/year)

p value

Usual snacking þ57 (þ13 to þ100) 0.011Age (years) �2 (�4 to þ1) 0.142Sex (women vs men) �44 (�96 to þ8) 0.098

Physical activity(METs-h/wk) �0.2 (�1 to þ1) 0.142TV viewing (h/day) þ3 (�3 to þ9) 0.306Sitting (h/day) �2 (�12 to þ8) 0.686Total energy intake

(kcal/day)þ4.4� 10� 3(�3.6� 10� 2 to 4.5� 10� 2)

0.831

Baseline BMITertile 1 0 (Ref.)Tertile 2 �59 (�112 to �6) 0.028Tertile 3 �210 (�270 to �149) <0.001

Fast-food*Tertile 1 0 (Ref.)Tertile 2 þ41 (�12 to þ95) 0.129Tertile 3 þ41 (�12 to þ96) 0.132

Sugar-sweetened beveragesTertile 1 0 (Ref.)Tertile 2 þ29 (�23 to þ81) 0.279Tertile 3 þ61 (þ3 to þ119) 0.039

Fiber intakeTertile 1 0 (Ref.)Tertile 2 þ17 (�36 to þ69) 0.534Tertile 3 �43 (�102 to þ17) 0.163

AlcoholTertile 1 0 (Ref.)Tertile 2 þ27 (�24 to þ77) 0.299Tertile 3 þ46 (�7 to þ99) 0.088

SmokingNon-smokers 0 (Ref.)Ex-smokers þ79 (þ26 to þ132) 0.004Smokers þ29 (�22 to þ80) 0.262Missing þ36 (�86 to þ158) 0.563

*Fast-food was the sum of hamburgers, sausages and pizza consumption.a Adjusted for age (years), sex, physical activity (METs-h/wk, continuous),

smoking (non-smokers, smokers, ex-smokers, missing), TV viewing (h/day,continuous), sitting (h/day, continuous), total energy intake (kcal/day, continuous),baseline body mass index (tertiles), fast-food consumption (tertiles), sugar-sweetened soft drinks consumption (tertiles), alcohol intake (tertiles), total fiberintake (tertiles).

b Adjusted for the variables of multivariate model 1þ changes in physical activity(no change, increase, decrease, not known), in smoking habits (non-smokers,ex-smokers, smokers, quitters, starters, missing), and in the consumption of meatand fruits/vegetables (no change, increase, decrease, not know) during follow-up.

M. Bes-Rastrollo et al. / Clinical Nutrition xxx (2009) 1–84

ARTICLE IN PRESS YCLNU1533_proof � 7 September 2009 � 4/8

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

463

464

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

473

474

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

488

489

490

491

492

493

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

UNCORRECTParticipants in the final sample were older and the percentage of

women was lower than in the eligible population. However, therewere no variables that changed more than 5% between samples. Inthe final sample, usual snackers were younger, less physicallyactive, had higher values for weight and BMI, they were more likelyto be female and less likely to be ex-smokers.

Regarding nutrient intake and food consumption, on average,usual snackers had higher total energy intake, total fat, saturatedfatty acid, monounsaturated fatty acid, and polyunsaturated fattyacid intake. Usual snackers also presented a higher glycemic loadand were more likely to consume nuts, non-handmade bakery,chocolates, sugar-sweetened beverages, fast-food and processedmeat (Table 2).

Usual snackers had a statistically significant (p¼ 0.01) highermean weight gain per year during follow-up in the multivariate-adjusted analysis (Table 3). Similarly, they were at higher risk (OR:1.66; 95% CI: 1.17–2.35) of gaining substantial weight (�3 kg peryear) during follow-up (Table 4). When we defined substantialweight gain either as� 5 kg per year or as an increment of� 10% ofbaseline weight, self-reported between-meal snacking was anindependent predictor for these outcomes. The adjusted oddsratios were 2.75 (95% CI: 1.17–6.50) and 1.29 (95% CI: 1.06–1.56),respectively. When we stratified the analyses by categories ofbaseline BMI all point estimates had a positive association betweensnacking and substantial weight gain (�3 kg/year) (p for interac-tion: 0.06). The only group where this association was statisticallysignificant was among normal weight participants. The habit ofself-reported between-meals snacking was significantly associatedwith a 66 percent higher risk of becoming obese during follow-upaccording to the multivariate Cox analyses (HR: 1.69; 95% CI:1.30–2.20). Those participants who usually snacked presented thesame risk of obesity as those participants who did not usually snackat a later age (Table 5).

Please cite this article in press as: Bes-Rastrollo M, et al., Prospective studyClinical Nutrition (2009), doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2009.08.017

After adjusting for changes in lifestyle during follow-up all theanalyses remained statistically significant.

When we conducted the analyses excluding those participantswith chronic disease (cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and cancer)(n¼ 1209) the results did not materially change but the magnitudeof the estimates were slightly stronger (adjusted OR for �3 kg/year): 1.75 (95% CI: 1.20–2.56), adjusted HR for incident obesity:1.71 (95% CI: 1.26–2.12).

of self-reported usual snacking and weight gain in a Mediterranean...,

UNCORRECTE

OOF

Table 4Odds Ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of substantial weight gain(�3kg/year) during follow-up according to snacking in the SUN Cohort Study(n¼ 10,162).

Non-snackers(n¼ 6704)

Usual snackers(n¼ 3458)

WEIGHT GAIN (�3 kg per year)Incident cases (%) 70 (1%) 70 (2%)Crude OR (95% CI) 1 (Ref.) 1.96 (1.40–2.73)Age- and sex-adjusted OR

(95% CI)1 (Ref.) 1.88 (1.34–2.65)

Multivariatea adjusted OR95% CI)

1 (Ref.) 1.66 (1.17–2.35)

Multivariateb adjusted OR(95% CI)

1 (Ref.) 1.50 (1.05–2.14)

STRATIFYING BY BASELINE BMIUnderweight (BMI< 18.5 kg/m2) (n¼ 347)

n 204 143Incident cases (%) 3 (1.5%) 3 (2.1%)Multivariatec adjusted OR(95% CI)

1 (Ref.) 3.25 (0.49–21.67)

Normal weight (18.5 kg/m2� BMI< 25 kg/m2) (n¼ 6676)n 4467 2209Incident cases (%) 34 (0.8%) 34 (1.5%)Multivariatec adjusted OR(95% CI)

1 (Ref.) 1.94 (1.18–3.18)

Overweight (25 kg/m2� BMI <30 kg/m2) (n¼ 2686)n 1795 891Incident cases (%) 27 (1.5%) 21 (2.4%)Multivariatec adjusted OR(95% CI)

1 (Ref.) 1.18 (0.64–2.19)

Obese (BMI� 30 kg/m2) (n¼ 453)n 238 215Incident cases (%) 6 (2.5%) 12 (5.6%)Multivariatec adjusted OR(95% CI)

1 (Ref.) 1.88 (0.63–5.58)

Results from all the variables included in the multivariatea model

Multivariatea OR(95% CI)

p value

Usual snacking 1.65 (1.17–2.34) 0.005Age (years) 0.98 (0.96–0.99) 0.013Sex (women vs men) 1.23 (0.81–1.86) 0.336

Physical activity(METs-h/wk) 0.99 (0.99–1.01) 0.675TV viewing (h/day) 0.98 (0.83–1.04) 0.557Sitting (h/day) 0.97 (0.89–1.06) 0.675Total energy intake

(kcal/day)1.00 (0.99–1.00) 0.264

Baseline BMITertile 1 1 (Ref.)Tertile 2 2.34 (1.39–3.92) 0.001Tertile 3 4.42 (2.59–7.52) <0.001

Fast-food*Tertile 1 1 (Ref.)Tertile 2 1.00 (0.62–1.63) 0.991Tertile 3 1.31 (0.83–2.07) 0.245

Sugar-sweetened beveragesTertile 1 1 (Ref.)Tertile 2 1.01 (0.63–1.62) 0.978Tertile 3 1.26 (0.77–2.06) 0.362

Fiber intakeTertile 1 1 (Ref.)Tertile 2 1.13 (0.75–1.72) 0.556Tertile 3 0.94 (0.56–1.56) 0.802

AlcoholTertile 1 1 (Ref.)Tertile 2 0.91 (0.60–1.38) 0.639Tertile 3 0.85 (0.54–1.32) 0.462

Table 4 (continued)

Non-snackers(n¼ 6704)

Usual snackers(n¼ 3458)

SmokingNon-smokers 1 (Ref.)Ex-smokers 1.15 (0.75–1.75) 0.523Smokers 1.05 (0.68–1.61) 0.828Missing 0.25 (0.03–1.81) 0.169

*Fast-food was the sum of hamburgers, sausages and pizza consumption.a Adjusted for age (years), sex, physical activity (METs-h/wk, continuous),

smoking (non-smokers, smokers, ex-smokers, missing), TV viewing (h/day,continuous), sitting (h/day, continuous), total energy intake (kcal/day, continuous),baseline body mass index (tertiles), fast-food consumption (tertiles), sugar-sweet-ened soft drinks consumption (tertiles), alcohol intake (tertiles), total fiber intake(tertiles).

b Adjusted for the variables of multivariate model 1þ changes in physical activity(no change, increase, decrease, not known), in smoking habits (non-smokers,ex-smokers, smokers, quitters, starters, missing), and in the consumption of meatand fruits/vegetables (no change, increase, decrease, not know) during follow-up.

c Adjusted for the variables of multivariate model 1 except for baseline body massindex.

M. Bes-Rastrollo et al. / Clinical Nutrition xxx (2009) 1–8 5

ARTICLE IN PRESS YCLNU1533_proof � 7 September 2009 � 5/8

Please cite this article in press as: Bes-Rastrollo M, et al., Prospective studyClinical Nutrition (2009), doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2009.08.017

501

502

503

504

505

506

507

508

509

510

511

512

513

514

515

516

517

518

519

520

521

522

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

531

532

533

534

535

536

537

538

539

540

541

542

543

544

545

546

547

548

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

571

572

573

574

575

576

577

578

579

580

581

582

583

584

585

586

587

588

589

590

591

PRNone of the covariates included in the multivariate model pre-sented problems of collinearity according to the tolerance value (orvariance inflation factor: VIF). The covariate with less tolerance (orhigh VIF) was for the highest tertile of fiber intake with a value of0.51 (or VIF: 1.97).

592

593

594

595

596

597

598

599

600

601

602

603

604

605

606

607

608

609

610

611

612

613

614

615

616

617

618

619

620

621

622

623

624

625

626

627

628

629

630

D4. Discussion

In this prospective study, self-reported between-meal snackingwas associated with a higher body weight gain and higher risk ofbecoming obese during an average of 4.6-year follow-up in healthymiddle-aged Spanish university graduates. To our best knowledge,it is the first time that a prospective study has found this positiveassociation among an adult free-living population in a Mediterra-nean country.

Our longitudinal results from a large prospective cohort of morethan 45,000 person-years support and extend in another pop-ulation previous findings on this topic. Francis et al.11 reported thatsnacking was a risk factor for the development of overweight ina longitudinal study of 173 non-Hispanic white girls from centralPennsylvania followed-up for 4 years. A lower frequency ofsnacking was one of the characteristics presented by the successfulgroup of 72 adolescents who maintained their weight loss ina follow-up study 1 and 2 years after the end of a weight-reductionprogram in a French medical center.12 A cross-sectional Swedishstudy found that obese people consumed snacks more frequentlythan their normal counterparts.13 Similarly, in anothercross-sectional study from the Continuing Survey of Food Intakesby Individuals in the USA, a higher eating frequency was associatedwith a higher BMI.14 Previous cross-sectional results from ourcohort showed that between-meal snacking increased the proba-bility of weight gain in the last 5 years before answering thebaseline questionnaire.15 Recently, Marin-Guerrero et al. found thatsnacking (eating smaller-sized meals per day) was associated withobesity among women based on a cross-sectional analysis ofa representative sample of Spanish population in 1999.16 Even incountries undergoing the nutrition transition, the adherence toa snacking pattern was positively associated with children beingoverweight.3

In contrast with these previous findings, however, there areother contradictory results in the literature: a 7-year follow-uplongitudinal study among 196 non-obese girls from Massachusettsdid not find any relationship between the consumption of energy-

of self-reported usual snacking and weight gain in a Mediterranean...,

CORRECTE

Table 5Hazard Ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of becoming obese duringfollow-up in 9709* participants according to snacking in the SUN Cohort study.

Non-snackers

Usualsnackers

RAPa

(years)

Person-years 30,197 15,009Incident cases (%) 145 (2.2%) 113 (3.5%)

Crude HR (95% CI) 1 (Ref.) 1.58 (1.23–2.02)Age- and sex-adjusted HR (95% CI) 1 (Ref.) 2.01 (1.56–2.58) þ5.67Multivariateb adjusted HR (95% CI) 1 (Ref.) 1.69 (1.30–2.20) þ12.83Multivariatec adjusted HR (95% CI) 1 (Ref.) 1.63 (1.26–2.12) þ13.29

Results from all the variables included in the multivariateb model

HR (95% CI) p value

Usual snacking 1.69 (1.30–2.20) <0.001Age (years) 1.04 (0.97–1.18) 0.250Sex (women vs men) 1.22 (0.90–1.66) 0.199Physical activity (METs-h/wk) 0.99 (0.99–1.00) 0.164TV viewing (h/day) 1.01 (0.97–1.04) 0.779Sitting (h/day) 1.05 (0.98–1.12) 0.186Total energy intake (kcal/day) 1.00 (1.00001–1.00002) 0.029

Fast-food**Tertile 1 1 (Ref.)Tertile 2 0.96 (0.68–1.35) 0.811Tertile 3 1.11 (0.80–1.55) 0.541

Sugar-sweetened beveragesTertile 1 1 (Ref.)Tertile 2 0.83 (0.60–1.14) 0.252Tertile 3 1.11 (0.78–1.56) 0.563

Fiber intakeTertile 1 1 (Ref.)Tertile 2 0.97 (0.72–1.32) 0.882Tertile 3 0.74 (0.50–1.09) 0.134

AlcoholTertile 1 1 (Ref.)Tertile 2 1.10 (0.78–1.55) 0.577Tertile 3 1.07 (0.76–1.50) 0.716

SmokingNon-smokers 1 (Ref.)Ex-smokers 1.38 (1.01–1.89) 0.043Smokers 1.10 (0.81–1.50) 0.545Missing 0.85 (0.39–1.83) 0.673

*After excluding 453 baseline obese participants (10,162� 453¼ 9709).**Fast-food was the sum of hamburgers, sausages and pizza consumption.

a RAP: Rate Advancement Period (26).b Adjusted for age (years), sex, physical activity (METs-h/wk, continuous),

smoking (non-smokers, smokers, ex-smokers, missing), TV viewing (h/day,continuous), sitting (h/day, continuous), total energy intake (kcal/day, continuous),baseline body mass index (tertiles), fast-food consumption (tertiles), sugar-sweetened soft drinks consumption (tertiles), alcohol intake (tertiles), total fiberintake (tertiles). A quadratic term for age to account for departure of linearity wasalso added.

c Adjusted for the variables of multivariate model 1þ changes in physical activity(no change, increase, decrease, not known), in smoking habits (non-smokers,ex-smokers, smokers, quitters, starters, missing), and in the consumption of meatand fruits/vegetables (no change, increase, decrease, not know) during follow-up.

M. Bes-Rastrollo et al. / Clinical Nutrition xxx (2009) 1–86

ARTICLE IN PRESS YCLNU1533_proof � 7 September 2009 � 6/8

631

632

633

634

635

636

637

638

639

640

641

642

643

644

645

646

647

648

649

650

651

652

653

654

655

656

657

658

659

660

661

662

663

664

665

666

667

668

669

670

671

672

673

674

675

676

677

678

679

680

681

682

683

684

685

686

687

688

689

690

691

692

693

694

695

696

697

698

699

700

701

702

703

704

705

706

707

708

709

710

711

712

713

714

715

716

717

718

719

720

721

722

723

724

725

726

727

728

729

730

731

732

733

734

735

736

737

738

739

740

741

742

743

744

745

746

747

748

749

750

751

752

753

754

755

756

757

758

759

760

UNdense snacks and weight gain.17 A prospective study of 8203 girls

and 6774 boys in the US suggested that although snack foods mayhave low nutritional value, they were not an important determi-nant of weight gain among children and adolescents.18 Similarly,Hampl et al19 did not find any association between snacking andBMI, despite observing a greater energy intake among thoseconsuming snacks. Yet their study did not take into account phys-ical activity.

Most research seems to indicate that snacking results in a higherenergy intake.10 However, other research concludes that dividingthe food intake over more than the regular three daily meals resultsin a readjustment of the number of calories eaten at meals times.28

Still, other research suggests a reduction of total energy intake with

Please cite this article in press as: Bes-Rastrollo M, et al., Prospective studyClinical Nutrition (2009), doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2009.08.017

DPROOF

an increased eating frequency.5 Probably, the key point is thedifferentiation between a small meal and a snack. The contradic-tory results may be a consequence of the complexity in the defi-nition of ‘‘snacking’’. A differentiation is needed between mainmeals or ‘‘structured meals’’ (breakfast, lunch and dinner) andsnacks (generally smaller and unstructured eating events betweenmeals).8 In Spain, the regular schedule in which meals are usuallyconsumed, with lunch between 2pm and 3pm and dinner between9pm and 10pm, contributes to the fact that there is a greatproportion of the population having midmorning and mid-afternoon snacks. Actually, the Spanish Society of CommunityNutrition (SENC)29 recommends eating five times a day, andconsiders the midmorning and midafternoon snacks as part of theregular daily intake. As a consequence of this, when we evaluatedthe meaning of the between-meal snacking question amonga subsample of the cohort (n¼ 53), 89% of them did not includea typical and scheduled midafternoon meal in their concept ofsnacking and 85% of them considered snacking as an unstructuredeating event. All of them defined snacking as small bites of choc-olates, candies, savoury snacks, bakery products, nuts, and pro-cessed meat (‘‘embutidos’’) eaten at any irregular time between themain meals.

Indeed, those SUN participants who snacked between meals inthe cohort had higher total energy intake, and higher consumptionof meat and processed meat products, chocolate, industrialbakery, and carbonated-sweetened-soft drinks than their coun-terparts (p< 0.001). Except for soft drinks, all of them are highenergy-dense food items. Therefore, the obtained results are notsurprising, given that a higher dietary energy density has beenassociated with higher risk of weight gain.30 In reference tosugar-sweetened soft drinks, as liquids do not have a high-energydensity by themselves, and because they are consumed instead ofwater, they contribute to the extra energy intake at the end of theday, and they are one of the known risk factors for obesity.31

Therefore, the promotion of structured eating habits may bea useful strategy to prevent weight gain in preventive health care.

Moreover, snack foods may be consumed in addition to, notinstead of, regular meals. Snack food may contribute to daily energyintake as much as 140–300 calories per item, thus the consumptionof several snacks per day would result in a nontrivial addition ofenergy. At the same time, researchers have reported that peoplewho snack do not compensate for the excess energy intake of thesnack with less energy intake in the main meals10 Marmonier et al.showed that snacks between meals do not generate extra signals ofsatiety.32 Finally, there are some data to suggest that the intake ofhigh-glycemic load foods, such as cookies and candies consumed assnacks, produce substantial increases in blood glucose and insulinlevels after ingestion. Within a few hours after their consumption,blood glucose levels begin to decline rapidly due to an exaggeratedincrease in insulin secretion and a state of hunger is created,leading to over consumption in the next meal. Thus, the continuedintake of high-glycemic load items is associated with an increasedrisk of obesity.33

We have to take into account that our study is not exempt ofpotential limitations. As we mentioned before, cultural differencesbetween countries with regards to the definition of what consti-tutes a usual snack compared with a main meal can contribute tothe results.

In our study, snacking is based on self-reported participants’answers. Therefore, it might be a differential under-reporting ofsnacking among obese compared with non-obese participants.34

Since overweight and obese participants are more prone to gainsubstantial body weight and overweight participants are morelikely to become obese, this differential report might bias theresults for incident substantial weight gain and obesity. Some

of self-reported usual snacking and weight gain in a Mediterranean...,

E

M. Bes-Rastrollo et al. / Clinical Nutrition xxx (2009) 1–8 7

ARTICLE IN PRESS YCLNU1533_proof � 7 September 2009 � 7/8

761

762

763

764

765

766

767

768

769

770

771

772

773

774

775

776

777

778

779

780

781

782

783

784

785

786

787

788

789

790

791

792

793

794

795

796

797

798

799

800

801

802

803

804

805

806

807

808

809

810

811

812

813

814

815

816

817

818

819

820

821

822

823

824

825

826

827

828

829

830

831

832

833

834

835

836

837

838

839

840

841

842

843

844

845

846

847

848

849

850

851

852

853

854

855

856

857

858

859

860

861

862

863

864

865

866

867

868

869

870

871

872

873

874

875

876

877

878

879

880

881

882

883

884

885

886

887

888

889

890

UNCORRECT

authors have suggested this point as the reason for the lack ofassociation observed in some previous studies.14 Despite thispotential limitation, we have found a statistically significant asso-ciation between self-reported snacking and obesity.

We should point out the differences in the number of participantsbetween the eligible population (n¼ 15,742) for longitudinal anal-yses and the final number of participants included in the analyses(n¼ 10,162), acknowledging the possible existence of a potentialselection bias. However, both populations were fairly homogeneousin terms of demographic characteristics and baseline exposure.

Unfortunately, since we measured ‘‘usual snack’’ once at base-line, we were not able to assess changes in snacking as a predictorfactor for weight gain and obesity. Moreover, the exposure wasevaluated dichotomously comparing between those self-reportedas usual snackers and those that self-reported occasionally/infre-quently snacking. This does not allow the possibility of evaluatinga dose-response relationship.

The methods used in nutritional epidemiology and theirinherent problems to ascertain a usual diet have been subjected tosome criticism35 and remain one of the major challenges in nutri-tional epidemiology. In any case, in our study a simple questionrelated to snacking had the ability to capture participants withhigher total energy intake, higher glycemic load and less fiberintake. Therefore, our results suggest that including a questionabout snacking might be a useful tool to assess healthy or unhealthyattitudes towards nutrition and a potential independent predictorof weight gain.

An important strength of our study is its prospective design withthe inclusion of a large number of participants followed-up fora median of 4.4 years, taking into account potential confounderssuch as TV viewing in the analyses. Changes in lifestyle factors canalso contribute to weight gain. For this reason, we have adjusted forchanges in lifestyle during follow-up and the associations remainedstatistically significant. Nonetheless, this is an observational study,and the possibility of residual confounding or collinearity amongvariables may limit the strength of causal inferences. However, theevidence derived from our results may clarify the role of snacking inthe obesity epidemic.

In conclusion, between-meal snacking has been associated witha subsequent higher body weight and with an increase in the risk ofbecoming obese in a free-living cohort of healthy middle-agedSpanish university graduates. Thus, this dietary trend of unstruc-tured eating episodes with food of low nutritional value isa potential risk factor to be discouraged in the promotion of healthylifestyles to tackle the obesity epidemic. At least, the promotion ofalternative nutritious snacks (eg. nuts, fresh fruit and vegetables)should be considered from a Public Health perspective.

Conflict of interestThe authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the SUN Study Group for adminis-trative, technical and material support, especially Dr. Miguel AngelMartinez-Gonzalez founding principal investigator of the SUNProject. We thank participants of the SUN Study for continuedcooperation and participation. The SUN Study has received fundingfrom the Spanish Ministry of Health (Grants PI030678, PI040233,PI070240, PI081943, RD06/0045), the Navarra Regional Govern-ment (projects 41/2005 and 36/2008) and the University ofNavarra.

MB-R and MS-M were responsible for study concept and design.MB-R and AS-V were responsible for acquisition and analysis of thedata. MB-R and FJB-G were responsible for drafting of the

Please cite this article in press as: Bes-Rastrollo M, et al., Prospective studyClinical Nutrition (2009), doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2009.08.017

DPROOF

manuscript. MB-R, AS-V, FJB-G, JMN-C, ET, MS-M were responsiblefor critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectualcontent. MS-M was responsible for obtaining funding. All authorsread and approved the final manuscript.

References

1. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. Fact sheet N�311, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/print.html; September 2006[accessed January 07.01.09].

2. Zizza C, Siega Riz AM, Popkin BM. Significant increase in young adults’ snackingbetween 1977–1978 and 1994–1996 represents a cause for concern! Prev Med2001;32:303–10.

3. McDonald CM, Baylin A, Arsenault JE, Mora-Plazas M, Villamor E. Overweight ismore prevalent than stunting and is associated with socioeconomic status,maternal obesity, and a snacking dietary pattern in school children fromBogota, Colombia. J Nutr 2008 [Epub ahead of print].

4. Nielsen SJ, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM. Trends in energy intake in U.S. between1977 and 1996: similar shifts seen across age groups. Obes Res 2002;10:370–8.

5. Astrup A, Bovy MW, Nackenhorst K, Popova AE. Food for thought or thought forfood?-A stakeholder dialogue around the role of the snacking industry inaddressing the obesity epidemic. Obes Rev 2006;7:303–12.

6. Maques-Vidal P, Ravasco P, Dias CM, Camilo ME. Trends of food intake inPortugal, 1987–1999: results from the National Health Surveys. Eur J Clin Nutr2006;60:1414–22.

7. Ribas-Barba L, Serra-Majem L, Salvador G, Castell C, Cabezas C, Salleras L, et al.Trends in dietary habits and food consumption in Catalonia, Spain (1992–2003).Public Health Nutr 2007;10:1340–53.

8. Ovaskainen ML, Reinivuo H, Tapanainen H, Hannila ML, Korhonen T, Pakkala H.Snacks as an element of energy intake and food consumption. Eur J Clin Nutr2006;60:494–501.

9. Cross AT, Babicz D, Cushman LF. Snacking patterns among 1800 adults andchildren. J Am Diet Assoc 1994;94:1398–403.

10. De Graaf C. Effects of snacks on energy intake: an evolutionary perspective.Appetite 2006;47:18–23.

11. Francis LA, Lee Y, Birch LL. Parental weight status and girls’ television viewing,snacking, and body mass indexes. Obes Res 2003;11:143–51.

12. Peneau s, Thibault H, Meless D, Soulie D, Carbonel P, Roinsol D, et al. Anthro-pometric and behavioural patterns associated with weight maintenance afterand obesity treatment in adolescents. J Pediatr 2008;152:678–84.

13. Berteus Forslund H, Torgerson JS, Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK. Snacking frequencyin relation to energy intake and food choices in obese men and womencompared to a reference population. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:711–9.

14. Howarth NC, Huang TT-K, Roberts SB, Lin BH, McCrory MA. Eating patterns anddietary composition in relation to BMI in younger and older adults. Int J Obes(Lond) 2007;31:675–84.

15. Sanchez-Villegas A, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Toledo E, de Irala J, Martinez JA.Influencia del sedentarismo y el habito de comer entre horas sobre la gananciade peso. [Relative role of physical inactivity and snacking between meals inweight gain]. Med Clin (Barc) 2002;119:46–52.

16. Marin-Guerrero AC, Gutierrez-Fisac Jl, Guallar-Castillon P, Banegas JR, Rodri-guez-Artalejo F. Eating behaviours and obesity in the adult population of Spain.Br J Nutr 2008;100:1142–8.

17. Phillips SM, Bandini LG, Naumova EN, Cyr H, Colclough S, Dietz WH, et al.Energy-dense snack food intake in adolescence: longitudinal relationship toweight and fatness. Obes Res 2004;12:461–72.

18. Field AE, Austin SB, Gillman MW, Rosner B, Rockett HR, Colditz GA. Snack foodintake does not predict weight change among children and adolescents. Int JObes Relat Metab Disord 2004;28:1210–6.

19. Hampl JS, Heaton CLB, Taylor CA. Snacking patterns influence energy andnutrient intakes but not body mass index. J Hum Nutr Diet 2003;16:3–11.

20. Lioret S, Touvier M, Lafay L, Volatier JL, Maire B. Dietary and physical activitypatterns in French children are related to overweight and socioeconomicstatus. J Nutr 2008;138:101–7.

21. Segui-Gomez M, de la Fuente C, Vaquez Z, de Irala J, Martinez-Gonzalez MA.Cohort profile: the ‘‘Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra’’ (SUN) study. Int JEpidemiol 2006;35:1417–22.

22. Willett WC. Issues in analysis and presentation of dietary data. In: Willett WC,editor. Nutritional epidemiology. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press;1998. p. 321–46. New.

23. Moreiras O, Carvajal A, Cabrera L. Tablas de composicion de alimentos. [Foodcomposition tables]. 9th ed. Madrid: Piramide; 2005.

24. Mataix Verdu J, Manas Almendros M. Tabla de composicion de alimentos. [Foodcomposition tables]. 4th ed. Granada: Universidad de Granada; 2003.

25. Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al.Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and METintensities. Med Sci Sports Excer 2000;32:S492–504.

26. Brenner H, Gefeller O, Greenland S. Risk and rate advancement periods asmeasures of exposure impact on the occurrence of chronic diseases. Epidemi-ology 1993;4:229–36.

27. Hernan MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Werler MM, Mitchell AA. Causal knowledge asa prerequisite for confounding evaluation. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:176–84.

28. Parks EJ, McCrory MA. When to eat and how often? Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:3–4.

of self-reported usual snacking and weight gain in a Mediterranean...,

M. Bes-Rastrollo et al. / Clinical Nutrition xxx (2009) 1–88

ARTICLE IN PRESS YCLNU1533_proof � 7 September 2009 � 8/8

891

892

893

894

895

896

897

898

899

900

901

902

903

904

905

906

29. Dapcich V, Salvador G, Ribas L, Perez Rodrigo C, Aranceta J, Serra-Majem L. Guıa dela alimentacion saludable. [Guide of the healthy diet]. Madrid: SENC-Everest; 2005.

30. Bes-Rastrollo M, van Dam RM, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Li TY, Sampson LL,Hu FB. Prospective study of dietary energy density and weight gain in women.Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88:769–77.

31. Bes-Rastrollo M, Sanchez-Villegas A, Gomez-Gracia E, Martinez JA, Pajares RM,Martinez-Gonzalez MA. Predictors of weight gain in a Mediterranean cohort:the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:362–70.

32. Marmonier C, Chapelot D, Fantino M, Louis-Sylvestre J. Snack consumed ina non-hungry state have poor satiating efficiency: influence of snack

UNCORRECTE

Please cite this article in press as: Bes-Rastrollo M, et al., Prospective studyClinical Nutrition (2009), doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2009.08.017

composition on substrate utilization and hunger. Am J Clin Nutr2002;76:518–28.

33. Thomas DE, Elliot EJ, Baur L. Low glycaemic index or low glycaemic loaddiets for overweight and obesity. CD005105. Cochrane Database Syst Rev2007;3.

34. Huang TT-K, Roberts SB, Howarth NC, McCrory MA. Effect of screening outimplausible energy intake reports on relationships between diet and BMI. ObesRes 2005;13:1205–17.

35. Kristal AR, Peters U, Potter JD. Is it time to abandon the food frequency ques-tionnaire? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:2826–8.

DPROOF

of self-reported usual snacking and weight gain in a Mediterranean...,