Ferguson - The green economy agenda: business as usual or transformative discourse?

Transcript of Ferguson - The green economy agenda: business as usual or transformative discourse?

This article was downloaded by: [The University Of Melbourne Libraries]On: 19 May 2014, At: 15:07Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH,UK

Environmental PoliticsPublication details, including instructions for authorsand subscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fenp20

The green economyagenda: business as usual ortransformational discourse?Peter Fergusona

a School of Social and Political Sciences, University ofMelbourne, Victoria, AustraliaPublished online: 15 May 2014.

To cite this article: Peter Ferguson (2014): The green economy agenda:business as usual or transformational discourse?, Environmental Politics, DOI:10.1080/09644016.2014.919748

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2014.919748

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all theinformation (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform.However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make norepresentations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, orsuitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressedin this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not theviews of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content shouldnot be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions,claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilitieswhatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connectionwith, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes.Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly

forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

The green economy agenda: business as usual ortransformational discourse?

Peter Ferguson*

School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

This analysis of the emergence since 2008 of the green economy agenda andthe related idea of ‘green growth’ focusses upon the articulation of thesediscourses within key international economic and environmental institutionsand evaluates whether this implies the beginning of an institutional transfor-mation towards an ecologically sustainable world economy. The greeneconomy may have the capacity to help animate a transition away fromcurrent socially and ecologically unsustainable patterns of economic growthonly if notions of green growth can be discursively separated from greeneconomy, strong articulations of green economy become dominant, andalternative measures of progress to gross domestic product are widelyadopted. The concept of ‘rearticulation’, found in post-structural discoursetheory, is proposed to guide this transition. This offers a framework toreconstruct notions of prosperity, progress, and security whilst avoidingdirect and disempowering discursive conflict with currently hegemonicpro-growth discourses.

Keywords: green economy; green growth; economic and environmentalsecurity; limits to growth; post-growth society; discursive rearticulation

Introduction

Whilst the concept of a ‘green economy’ has been part of environmentaldiscourse for more than two decades (Pearce et al. 1989, Jacobs 1991, Ekins2000), it has generally been subsumed within the meta-discourse of sustainabledevelopment. However, in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis and theincapacity of sustainable development to reconcile conflicting global economic,development, and ecological imperatives (Rist 1997, Banerjee 2003), the greeneconomy and the related notion of ‘green growth’ have been drawn into theforeground of environmental and economic discourse.

Beginning from the premise that current patterns of economic growth aresocially and ecologically unsustainable (Easterlin 1974, Daly 1977, Hirsch 1977,Max-Neef 1995, Inglehart 1996, Meadows et al. 2004, 1972, Victor 2008,Jackson 2009, Bardi 2011, Heinberg 2011), I explore whether the recent

*Email: [email protected]

Environmental Politics, 2014http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2014.919748

© 2014 Taylor & Francis

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

emergence of the green economy discourse implies the beginning of a morefundamental transformation towards a ‘post-growth society’. In this society, theeconomy will not breach sustainable biophysical thresholds; the social andecological costs of economic activity will not exceed its benefits, and thecommitment of governments to economic growth will be replaced by objectivessuch as societal well-being and environmental protection. This is not to say thatall growth should be discouraged. Indeed, many countries require some forms ofgrowth, such as growth in renewable energy production, education, and healthservices to help ameliorate numerous environmental and social problems.However, sharp reductions in other forms of growth, primarily in the fossil-fuel sector, must offset this socially beneficial growth (Daly 2007, van den Berghand Kallis 2012).

I begin by delineating the main green economy discourses and the practicesthrough which these are enacted and reified (Adler and Pouliot 2011). These aregarnered from recent reports and statements on the green economy released byinternational economic and environmental institutions. This analysis aims not toprovide a comprehensive review of this literature, but to develop a general senseof how influential actors understand the green economy agenda, and to identifysome of the key tensions and ambiguities within these understandings. I arguethat the green economy discourse may have the capacity to help animate atransition away from conventional forms of growth to a post-growth futureonly if alternative measures of social and economic progress to gross domesticproduct (GDP) are widely adopted, established concepts of economic and envir-onmental security are reformulated, and notions of green growth are discursivelyseparated from notions of green economy. There is some evidence that the firsttwo of these conditions are now partly being met, whilst the third remainsaspirational. The final part of my discussion furthers this discursive transforma-tion using the tools of post-structural discourse analysis. This discursive turnseeks to promote a strong form of green economy that is cognisant of the socialand ecological costs of, and limits to, economic growth.

The green economy agenda

A major criticism of sustainable development is that it is vague and impreciseabout what is to be sustained, how this is to occur, and for whom it is to besustained. For example, whilst environmentalists envisage sustaining ecosystemsand biodiversity, business is generally more interested in sustaining profits(Dobson 2007). Sustainable development, therefore, lacks policy precisionbecause both the terms ‘sustainable’ and ‘development’ largely remain floatingsignifiers (Sachs 1992, McManus 1996, Vos 1997). The green economy agenda,in contrast, is much more focused, rendering it a potentially more effectivediscourse for promoting strong environmental policies (Jacobs 2012). This pre-cision stems from two key elements: the concept of green growth and thepromotion of new national accounting techniques.

2 P. Ferguson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

Green growth

Jacobs (2012, p. 4) argues that the core meaning of green growth is straightfor-ward. Simply, it is ‘economic growth … which also achieves significantenvironmental protection’. However, what counts as ‘significant environmentalprotection’ is highly contested. For example, Huberty et al. (2011) identify sixdifferent and sometimes contradictory articulations of the signifier ‘green’ in thegreen growth literature:

● climate-change mitigation via significant reductions in greenhouse-gasemissions;

● emissions reductions, plus ecosystem protection and the protection ofhuman health in the service of human welfare;

● all of the above as goods in and of themselves rather than only in theservice of human welfare;

● all of the above plus the mitigation of all human impacts on the naturalworld;

● a general concept of environmental carrying capacity that seeks toreconcile economic growth with an assumption of the limited ability ofthe environment to support human economic activity; and

● a notion of the dynamic ability of the environment to respond togrowth-induced shocks.

Green growth has also been articulated within a range of economic theoreticalframes (Bowen and Fankhauser 2011, Geels 2012, Jacobs 2012). One of these isgreen Keynesianism (see Bowen et al. 2009, Houser et al. 2009, Zenghelis 2012,Harris 2013), which was most prominent in the aftermath of the 2008 globaleconomic crash when many governments included significant funding forenvironmental programmes in their fiscal stimulus packages. Another approachis green growth theory (see Ekins and Speck 2011, Hallegatte et al. 2011, WorldBank 2012), which seeks to rectify the undervaluing of natural capital byremoving distorting subsidies to polluting industries and introducing emissionstaxes and tradable permits to create incentives for cleaner production andconsumption. A third approach argues that low carbon energy systems andother environmental technologies are on the brink of creating a green industrialrevolution (see Jänicke and Jacob 2009, Stern and Rydge 2012), which offersinnovative countries and corporations significant first-mover advantages in thegreen technology race.

Alternative measures of progress

The green economy agenda is also more precise than sustainable developmentabout social and environmental objectives. This is demonstrated by the promo-tion of alternative national accounting techniques to GDP, which comprise a

Environmental Politics 3

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

range of social, environmental, and economic indicators. These metrics comparethe benefits and costs of economic activity by deducting lost leisure time, incomeinequality, resource depletion, and defensive expenditures such as pollutionabatement, traffic accidents, and remedial health care from total private con-sumption expenditure. Additions are then made for public goods includingpreventative health care, public services, and domestic and volunteer work(Lawn 2006).

Whilst alternatives to GDP have long featured in the ecological economicsliterature, they are now moving into mainstream economic discourse. Forinstance, a number of economists have recently developed metrics to incorporateecosystem services and natural capital depreciation into the national accounts(see Dasgupta 2009, Bateman et al. 2011, Hamilton and Ruta 2009). These havebeen promoted by the UN Statistics Division (2012), which has launched a newSystem of Environmental and Economic Accounting to assist the development ofecosystem valuation at the national and sub-national levels. Recent World Bankand European Commission reports have also challenged established practices ofmeasuring social and economic progress, and exalted governments to produce aset of natural capital accounts to complement the standard national accounts(European Commission 2009, Patil 2012).

One of the first world leaders to respond to this challenge was the formerFrench President Nicholas Sarkozy. In 2009, he established an expert panel to‘identify the limits of GDP as an indicator of economic performance and socialprogress…; to consider what additional information might be required for theproduction of more relevant indicators…; [and] to assess the feasibility ofalternative measurement tools’ (Stiglitz et al. 2009, p. 7.) The following year,UK Prime Minister David Cameron admitted that ‘there’s more to life thanmoney and it’s time we focused not just on GDP but on GWB – general well-being’ (quoted in Stratton 2010). He also announced that the UK nationalstatistician would begin collecting data on well-being and sustainability withthe view to using this rather than GDP to measure national progress. Meanwhile,in the United States, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010)requires Congress to fund and oversee the creation of a new system of keywell-being indicators (Gertner 2010).

If these alternative measures of progress are widely adopted, it shouldbecome clear that conventional economic growth often creates more costs thanbenefits. This will certainly be the case if the results from existing holisticmetrics such as the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW), theGenuine Progress Indicator (GPI), and the Sustainable Net Benefit Index(SNBI) are replicated. While there has been some variation across these mea-sures over the last few decades, all have decreased in relation to GDP indeveloped countries. For instance, the ISEW declined significantly between1975 and 1990 in the United States and the UK at the same time as GDPincreased. The story is similar in other rich countries. For instance, Australia,Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden have all either stagnated or

4 P. Ferguson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

declined on this measure over the same period (Daly 1999, Lawn and Sanders1999, Offer 2006).

Related to these alternative measures of progress is the factoring of long-termenvironmental costs into cost–benefit policy analysis. Stern (2007) and Garnaut(2008) compared the costs and benefits of adopting greenhouse-gas mitigationmeasures earlier rather than later, and found that the case for the former iscompelling. This conclusion was reached by adopting a discount rate (therelative weighting of current costs and benefits vis-à-vis future costs) that reflectsthe scientific evaluation of climate-change risks (Dietz 2008). Meanwhile, theUnited Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2011) has modelled a futuregreen growth trajectory in which 2% of global GDP is allocated to environmentalinvestments between 2010 and 2050. Under this scenario, total annual globalGDP is lower than business as usual (where no significant shift of investment tothe green sector occurs) until 2017, when the costs of environmental degradationbegin to constrain growth. The real growth rate, meanwhile, is predicted tosurpass that expected in the absence of the 2% environmental investment by2020. By 2050, the gap between the business as usual and green growthtrajectories is projected to be at least 0.5% per annum.

These new cost–benefit metrics also have the potential to undermine the casefor conventional economic growth. This is because when the long-term implica-tions of policies are properly factored into cost–benefit analyses radical and rapidchanges in policy direction can often be realised. The success of tobacco controlin many jurisdictions, which can be partly attributed to the recognition that thelong-term public-health benefits of reducing smoking rates far outweigh theshort-term costs of regulating and attenuating the tobacco industry, illustratesthis potential (Jha and Chaloupka 1999, Hurley and Matthews 2008).

Tensions in the green economy agenda

The main criticism of the green economy agenda is that green growth isnecessarily dependent to some extent upon the ‘decoupling’ of economic growthfrom environmental degradation and resource consumption. There is someevidence of relative decoupling, in which the biophysical throughput of theeconomy (volume of natural resources exhausted per unit of production) isreduced so that resource use declines relative to GDP. For example, the amountof energy required to produce each unit of global economic output has fallengradually over the last 50 years, so that worldwide energy intensity is now 33times lower than it was in 1970. The problem is, however, that total energy usehas increased exponentially as the economy has grown, thus increasing biophy-sical throughput, albeit at a slower rate than overall GDP (Jackson 2009).

What is needed, therefore, is absolute decoupling to reduce total biophysicalthroughput irrespective of the growth rate. However, evidence of this form ofdecoupling is rather scant. In a small number of countries, there has been astabilisation of resource throughput since the late 1980s, although this appears to

Environmental Politics 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

have been achieved by moving production offshore, thus effectively outsourcingenvironmental externalities to the developing world (Andersson and Lindroth2001, Rice 2007, Jackson 2009). Of course, as Hepburn and Bowen (2013) pointout, the current absence of absolute decoupling does not provide irrefutable proofof the impossibility of any future structural shift in this direction. Indeed, thedevelopment of many technologies, such as the microchip and the photovoltaiccell, has seen exponential increases in efficiency accompanied by dramaticreductions in costs. Nonetheless, in a growing economy, absolute decoupling islikely to remain elusive because gains in resource efficiency are almost alwaysabsorbed by increases in resource consumption (Herring 2006). Saunders (2010)suggests that this ‘rebound effect’ can negate as much as 60–100% of energysavings. For example, the efficiency of electricity usage in the United Statesincreased by 57.3% during the twentieth century at the same time that totalannual electricity consumption increased by 630% (Victor 2008). Hepburn andBowen (2013) suggest that the rebound effect can be negated without necessarilyimpeding growth by properly pricing environmental externalities. However, anumber of analysts have found that the more environmentally effective instru-ments such as pollution taxes are, the more they actually reduce economicefficiencies (Goulder 1995, Parry and Bento 2000, de Mooij 2002), thus under-mining the prospects for green growth generated by increased eco-efficiency.

The decoupling issue needs to be taken seriously. However, it does notnecessarily mean that the green economy agenda has no transitionary potential.Moving to greener forms of growth, even if they merely constitute relativedecoupling, appears to be the only feasible first step towards a post-growtheconomy. This is because most existing economic–environmental discoursesare either too vague to animate this transition and/or they are politically unpala-table. Sustainable development exemplifies the former, whilst degrowth, steady-state economics and ecosocialism are examples of the latter. This is not to saythat degrowth, steady-state economics, and/or ecosocialism do not articulatethe necessary socio-economic and macroeconomic trajectories towards a post-growth future. Rather, these discourses are unlikely to have sufficient politicalpurchase to effect this transformation. This is because, by directly opposinggrowth, they are prone to marginalisation. It is in the context of this ‘politicalreality’, therefore, that the green economy agenda must be evaluated. This is bothfor its potential to circumvent discursive conflict between the growth and post-growth perspectives, and to act as a catalyst for the far-reaching normative andpolicy changes required to move eventually to a post-growth society.

Institutional transformations

The green economy agenda, and in particular the green growth discourse,have been primarily articulated by international institutions. These include theOrganisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD),International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, World Trade Organization

6 P. Ferguson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

(WTO), and UNEP. This may seem surprising given that, with the exception ofUNEP, the raison d’être of these entities has hitherto been the promotion ofglobal economic growth. However, whilst existing institutions might at one levelconstitute a barrier to implementing strong environmental policies, their role andeven underlying purpose is more amenable to change than is commonly believed(Stein 2008). This even extends to basic economic, social, and environmentalgoals, as a number of recent discursive developments suggest.

For example, in its report Towards Green Growth, the OECD (2011, p. 9)defined green growth as ‘fostering economic growth and development whileensuring that natural assets continue to provide the resources and environmentalservices on which our well-being relies’. This requires ‘framework conditionsthat mutually reinforce economic growth and the conservation of natural capital’,and ‘policies targeted at incentivising [sic] efficient use of natural resources andmaking pollution more expensive’ (OECD 2011, p. 11–12). The report alsorecognised the existence of ‘planetary boundaries’, two of which (biologicaldiversity and the nitrogen cycle) the OECD acknowledges have already beenbreached.

The IMF has also recently backed the concept of a ‘green economy’ (Lagarde2012), whilst the World Bank, as noted above, has become a proponent ofalternative national accounting techniques. The World Bank (2012, p. 2) nowalso acknowledges that ‘for the past 250 years, growth has come largely at theexpense of the environment … [a]nd environmental damages are reaching a scaleat which they are beginning to threaten both growth prospects and the progressachieved in social indicators’. What is needed, it is argued, is ‘inclusive greengrowth’ defined as ‘growth that is efficient in its use of natural resources, clean inthat it minimises pollution and environmental impacts, and resilient in that itaccounts for natural hazards and the role of environmental management andnatural capital in preventing physical disasters’ (World Bank 2012, p. 2). TheBank also recognises that this growth is needed more in the South than the North,middle-class consumption patterns are unsustainable, and what matters ultimatelyis welfare, not total economic output. However, any major global redistribution ofresources to correct North–South inequality is not countenanced.

The World Bank and the WTO have also recently rejected the EnvironmentalKuznets Curve (EKC) (Tamiotti et al. 2009, World Bank 2012). This is theunsubstantiated hypothesis that environmental degradation increases in the initialstages of economic growth, but once a certain aggregate level of growth isreached, the rate of degradation declines (de Bruyn 2000, Brekke and Howarth2002, Jackson 2009). The WTO has also utilised the green economy discourse inan attempt to reinvigorate the stalled Doha Round of trade talks (WTO 2012).

However, despite problematising conventional economic growth, the WorldBank’s green growth vision still relies upon unproven absolute decoupling. TheBank also continues to invest heavily in projects that are either large producers orconsumers of fossil fuels (Newell and Paterson 2010), although there have beensome recent indications that this may be beginning to change (World Bank

Environmental Politics 7

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

2013). Similarly, despite its recent green growth posture, the IMF continues topublish its annual Going for Growth report, which compares the growth rates ofmember states and outlines reform priorities to help these economies grow faster(OECD 2013).

The most promising institutional articulation of the green economy discourseis UNEP’s Towards a Green Economy report. This document states unequivo-cally that ‘at a fundamental level’, the world’s mounting environmental problemsand intractable poverty are a consequence of ‘the gross misallocation of capital’(UNEP 2011, p. 14). This, UNEP claims, has generated excessive investment inproperty, fossil fuels, and speculative financial instruments at the expense ofrenewable energy, energy efficiency, public transport, sustainable agriculture,land and water conservation, and ecosystem and biodiversity protection. Thereport argues that ‘[m]ost economic development and growth strategies encou-rage rapid accumulation of physical, financial and human capital … at theexpense of excessive depletion and degradation of natural capital’. Moreover,‘[b]y depleting the world’s stock of natural wealth – often irreversibly – thispattern of development and growth has had detrimental impacts on the wellbeingof current generations and presents tremendous risks and challenges for thefuture’ (UNEP 2011, p. 14). This recognition leads UNEP to propose compre-hensive long-term economic development models that take into account thedepletion of natural resources and the reduction of long-term annual globalrates of growth from their current level of approximately 3% to below 2%.

The institutional embrace of the green economy agenda clearly indicates amove to some extent away from conventional growth. However, it does not asyet presage a more fundamental shift towards a post-growth economy. Indeed,even putting these relatively prosaic green economic visions into practice hasproved beyond most governments, as the 2012 Rio + 20 Conference demon-strated. The reports discussed above were intended to frame debate at thismeeting, leading to the agreement of a new and ambitious framework forsustainable development. However, the final conference declaration did littlemore than reaffirm, and in some respects water down, the principles enshrinedin the 1992 Rio Declaration (United Nations 2012, Watts and Ford 2012).

From green growth to green economy

Whether the green economy agenda animates a substantial shift towards anecologically sustainable economy depends upon the extent to which states,international institutions, and other key actors transcend their commitment togrowth. One dimension of this transformation will obviously involve the conceptof green growth. However, given its reliance upon as yet unproven absolutedecoupling rather than overall reductions in aggregate growth, this can only takeus so far. The broader green economy discourse, in contrast, has greater trans-formative potential because it is more agnostic about growth. Thus, the green

8 P. Ferguson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

growth and green economy discourses must be clearly disaggregated, with mostemphasis placed on the latter.

This distinction can be articulated in terms of the ecological modernisationspectrum. Christoff (1996, p. 490) argues that the different articulations ofecological modernisation (the idea that increasing resource efficiency andwaste minimisation can have mutually reinforcing environmental and economicbenefits and that solving environmental problems in the present is more cost-effective than addressing them in the future) can be arrayed along a continuumfrom weak to strong, ‘according to their likely efficacy in promoting enduringecologically sustainable transformations and outcomes’. At the weaker end of thespectrum, ecological modernisation is economistic, technological, instrumental,narrowly technocratic, corporatist, nationally bounded, and requires no funda-mental transformation of the state or economy. In its stronger incarnations, it isecologically mindful, institutionally systemic, communicative, deliberative,democratic, international, and diversifying (Christoff 1996).

The transformative potential of strong ecological modernisation stems fromits ‘reflexivity’ (Paterson et al. 2006): it encourages continual reflection upon theconsequences and purposes of the modernisation process and the means and endsof social, political, and economic action. The basic argument is that whenmodernisation reaches a certain stage, it radicalises itself and begins to transformnot only key institutions but also the underlying norms of industrial society. Beck(1992) asserts that this allows reflexively modern societies to renegotiate theirrelationship with nature radically, as the social practices that have traditionallyshaped industrialisation have become much more fluid and amenable to change.This, he argues, is the logical consequence of politics in Western societiesbecoming increasingly dominated by the production, selection, distribution,and amelioration of risks, so that questions of distribution now concern notonly ‘who gets what?’ but also ‘who is exposed to what risks?’ and ‘who definesrisks?’

These ‘new risks’ stem primarily from industrial society’s externalities, suchas climate change, genetically modified organisms, food insecurity, nuclearaccidents, and pollution. They are also the consequence of neo-liberal reformsthat have increased social and economic insecurities (ILO 2004b). The advent ofthe risk society forces an important modification to the traditional strictures ofclass politics so that social conflict is now about the distribution of both ‘goods’and ‘bads’. This implies that state legitimacy depends just as much uponprotecting society from ecological risks as it does upon facilitating economicgrowth. However, to the extent that growth exacerbates environmental degrada-tion, this is contradictory. Dryzek et al. (2003) argue that strong and reflexiveecological modernisation provides one way to overcome this problem byredefining notions of societal progress and risk, thus realigning state prioritieswith strong environmental protection more than with sustained economic growth.These new risks can also be managed by reconceiving notions of security,necessitating a shift in the focus of security from the state to people,

Environmental Politics 9

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

communities, and ecosystems (UNDP 1994, Barnett 2001, Dalby 2009). Twonew security discourses are relevant in this context.

One is economic security, which the International Labour Organization (ILO)(2004a, unpaginated) defines as ‘limiting the impact of uncertainties and riskspeople face while providing a social environment in which people can belong toa range of communities, have a fair opportunity to pursue a chosen occupationand develop their capacities via … decent work’. Recent studies have found onlya very weak correlation between economic growth and economic security overthe long term and virtually no relationship between per capita income and totallevels of economic security, because some relatively poor countries exhibithigher levels of economic security than some relatively rich nations (ILO2004b). To the extent that economic security and per capita income are positivelycorrelated, this relationship becomes progressively weaker above a relatively lowaverage income threshold. This is not to suggest that higher incomes provide nobenefits; merely that increases above a relatively low level bring only diminish-ing marginal benefits (Easterlin 1995, Inglehart 1996, Argyle 1999, Frey andStutzer 2002, Layard et al. 2008). What it does indicate, however, is thateconomic growth beyond a low threshold is not a necessary precondition foreconomic security.

The other new security discourse is environmental security. Generally, this isarticulated in terms of a new security imperative for states. For example, the USDepartment of Defense (2010) is now concerned that climate change will accel-erate instability and conflict around the world whilst reducing the viability ofmany defence installations and undermining energy security for defence opera-tions (see also CNA 2007). Environmental security can also be thought of moresystemically as ‘the process of peacefully reducing human vulnerability tohuman-induced environmental degradation by addressing the root causes ofenvironmental degradation and human insecurity’ (Barnett 2001, p. 129). Thisrequires reorientating human activity to secure the conditions that make civilisa-tion possible and protecting the resources that are a precondition for all otherhuman activities (Rogers 1997, Dalby 2009, Cudworth and Hobden 2011). Tothe extent that economic growth drives and is driven by the processes ofindustrialisation that generate environmental insecurities, this entails limitingconventional growth.

So how might the move towards a green economy built upon strong ecolo-gical modernisation and economic and environmental security be instigated? Thefirst step is to recognise that the green economy remains a disaggregated andcontested discourse, especially with respect to the degree to which the costs ofand limits to growth are acknowledged. Bär et al. (2011) argue that the literaturedeals with this issue in three distinct ways (see also Urhammer and Røpke 2013,Tienhaara 2014).

The first, conventional pro-growth perspective, assumes that growth is anecessary precondition for societal well-being and that a green economy simplyinvolves making existing patterns of growth more resource efficient. This is the

10 P. Ferguson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

most common articulation of the green growth discourse, which sees little needto modify conventional GDP calculations. The OECD and World Bank reportslargely fall into this category, although their promotion of alternative measures ofprogress is more transformational. A second, selective growth position, seessome correlation between growth and societal well-being in the medium term,but calls for the expansion of the ‘green’ vis-à-vis the ‘brown’ sectors of theeconomy. It also holds that GDP figures should be adjusted to account fornegative social and ecological externalities and for changes in natural capitalstocks, whilst acknowledging the necessity of eventually finding solutions topolicy problems that do not rely upon growth. In this sense, it is generallyagnostic about whether growth should be a policy objective. What is importantis whether growth promotes or impedes more fundamental social and environ-mental objectives (van den Bergh and Kallis 2012). The UNEP and ILO reportsare emblematic of this perspective. The third, limits to growth articulation, is theleast well-developed theme in the green economy discourse. It is found largely inthe academic literature (see, e.g., Cato 2009, Jackson and Victor 2011), ratherthan the institutional reports discussed above. From this perspective, growthcannot be decoupled from its environmental impacts, and holistic measurementsof welfare must replace conventional forms of national accounting.

There is also a significant cleavage between those green economy discoursesthat consider Western levels of consumption sustainable and those that do not.The former hold that current consumption patterns can simply be ‘greened’,whilst the latter recognises the need for more systemic institutional changes(Bär et al. 2011). Differences also exist between security discourses that focuson state security and those with a broader remit addressing economic andenvironmental risks.

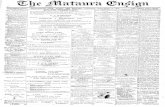

These findings highlight three forms of green economy discourse: weakgreen economy, transformational green economy, and strong green economy(see Table 1).

Each of these discourses can be mapped onto the ecological modernisationcontinuum so that transformative articulations of green economy provide thebasis for a shift from the currently dominant weak green economy to a futurestrong green economy. Reconstructing the ecological modernisation spectrum inthis way has the potential to give ecological modernisation greater discursivetraction because it is largely a descriptive and normative discourse used by policyanalysts rather than an animating discourse of politics or policymaking. Incontrast, as the reports cited above demonstrate, the ‘green economy’ hasbecome increasingly prominent in mainstream policymaking discourse.

Of course, current articulations of the green economy do not imply a futurepost-growth society. Nevertheless, concepts such as green/selective/A-growth,modified GDP, and economic and environmental security might assist intransforming the green economy discourse in this direction. Some level ofconventional economic growth will still be required initially, but there is areasonable prospect for this to be slower, and thus less environmentally

Environmental Politics 11

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

degrading. This is crucial because, in the absence of unprecedented energyefficiency improvements, there is no prospect that technological innovationwill ever compensate for the ecological effects of 3% growth per annum.However, at a lower growth rate, efficiency improvements may be better ableto keep pace (Ekins 1994).

Simultaneously, the ‘degrowing’ of the economic sectors that cause the mostserious environmental damage could be offset by growth in more environmentallyfriendly areas. This would need to be supported by other structural economicreforms, such as prioritising resource productivity over labour productivity, shift-ing the tax base from labour to natural resources, rescinding fossil-fuel subsidies,and reversing the concentration of wealth that has occurred during the neo-liberalera (Jänicke 2012, Ferguson 2013). Once these policies gain traction, the greeneconomy agenda may be separated from the commitment to growth, green orotherwise, and then progressively rearticulated in a post-growth direction.

Post-growth rearticulatory strategies

In discourse theory, (re)articulation is the process of (re)shaping and (re)linkingdiscourses, or elements within these (Laclau and Mouffe 2001). All ‘elements

Table 1. Typology of green economy discourses.

Weak green economyTransformational green

economyStrong greeneconomy

Macroeconomictrajectory

Green growth Selective growth/A-growth

Limits to growth/post growth

Economic,social &environmentalindicators

Unmodified GDP Modified GDP Encompassingmeasures ofwelfare

Western levelsofconsumptionsustainable orunsustainable

Western consumptionsustainable/greenconsumerism

Green consumerism/institutional changesneeded

Westernconsumptionunsustainable/more systemicinstitutionalchanges needed

Focus ofsecuritydiscourse

State security Limited economic andenvironmentalsecurity

Extensive economicand environmentalsecurity

Key institutionalliterature

World Bank 2012,Lagarde 2012, WTO2012, OECD 2011,US Department ofDefense 2010,Tamiotti et al. 2009,CNA 2007

United NationsStatistical Division2012, Patil 2012,UNEP 2011EuropeanCommission 2009,Stiglitz et al. 2009

Academic literatureonly e.g. Jacksonand Victor 2011,Cato 2009

12 P. Ferguson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

pre-exist articulation as floating signifiers, the act of linking in a particulardiscourse modifies their character such that they can be understood as beingspoken anew’ (DeLuca 1999, p. 335). This linking of elements into a temporaryunity, however, is not preordained, but the result of fluid political and historicalstruggles for discursive hegemony. For a discourse to become hegemonic, twoconditions must be met. First, using it is the only credible way for actors tointervene in a particular issue or policy area. Second, basic premises of thediscourse are translated into competent state, institutional, and policy practices(Hajer 1995) within particular ‘communities of practice’, defined as ‘like-mindedgroups of practioners who are formally as well as contextually bound by a sharedinterest in learning and applying a common practice’ (Adler 2008, p. 196).

The green economy discourse is a productive place to begin rearticulating thecommitment to growth. This is because it avoids expressing an explicit ‘anti-growth’ or ‘limits to growth’ position (Glasson 2013), which as Barry (2012)argues, has long been the Achilles heel of environmental politics. Importantly,this does not mean denying the costs of and limits to growth, but merelyavoiding a negative and disempowering pro-growth/anti-growth binary. Thechallenge is to make links between the progressively more transformationalelements of the green economy, thus moving from the current commitment togrowth to a post-growth future, whilst avoiding direct conflict with the existinghegemonic growth discourse (Glasson 2013). This is why discourses such assteady-state economics, degrowth, and ecosocialism are of little strategic value.The green economy and economic and environmental security, in contrast, areclearly distinct from conventional growth, but do not exist in simple oppositionto it. Rather, their transformative potential resides in the ability to rearticulateexisting growth discourses subversively. Glasson (2013, p. 12) depicts thissubversion of seemingly entrenched binary opposites as the forging of ‘a seriesof articulations that describe an arc first away from the binary and then,cumulatively, change course such that we arrive at the prohibited term withouthaving to “cross the bar” of the binary directly’.

Subversive rearticulation requires the identification of signs that can act aspivot terms or pivot discourses to shift discursive conflict away from incompa-tible binary opposites (Glasson 2013). Pivot discourses must in no way favourone or other pole of the binary, because this risks invoking the binary logic, thusundermining any attempt to subvert these antinomies. For this reason, a pivotdiscourse must initially appear neutral or agnostic about the discursive antagon-ism it seeks to subvert. This allows the binary opposites to continue holding theirincompatible positions. However, in some instances, the pivot discourse canbecome dominant, thus collapsing the existing binary and making subversiverearticulation possible. Pivot discourses must also be consistent with existingmaster signifiers such as ‘modernisation’, and especially ‘the economy’. Indeed,the latter is routinely used as a synonym for ‘capitalism’ and ‘the market’, and asGlasson (2013, p. 11) puts it, ‘is not an object per se but the condition ofintelligibility of all objects’. This means that to be credible, any transformative

Environmental Politics 13

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

post-growth discourse must display considerable deference to the economymaster signifier, whilst disarticulating itself from conventional economic growth.

Notions of green economy and economic security are obvious candidates forthis role, because, whilst both discourses are consistent with the master signifier‘economy’, they are also distinct from conventional growth (Barry 2012, Glasson2013). For example, green economy can be articulated in binary opposition tobrown or dirty economy. This works to delegitimise conventional growthbecause this is clearly comparatively deficient vis-à-vis green growth/economy.Meanwhile, economic security can be articulated in diametric opposition toeconomic insecurity, which clearly delineates the former as the desirable poleof the binary. The key rearticulatory move is to attach notions of well-being toeconomic security rather than to economic growth. In this way, rather thansimply rejecting economic growth, which is currently politically unfeasible, thegreen economy and economic security discourses provide an indirect form ofopposition by shifting the dominant articulations of ‘economy’ away fromgrowth. This allows those seeking a post-growth society to be pro-economy,but in a way that disarticulates growth from economy and rearticulates it towardsmore sustainable social and ecological objectives. In other words, growth can besubverted by being pro-economy whilst working to redefine the concept of theeconomy (Barry 2007, Glasson 2013).

This subversive rearticulatory strategy is summarised as follows. The firstmove away from conventional growth involves the articulation of a weak greeneconomy discourse framed in terms of green growth. From here, it is a small butsignificant semantic step from weak green economy to transformational greeneconomy, where the latter is often agnostic about growth. This pivot discoursethen facilitates the shift from a largely ‘growth positive’ to an increasingly‘growth negative’ discursive framing. The next move is towards strong greeneconomy which articulates a limits to growth discourse. This in turn allows thefinal rearticulatory move to a post-growth society. In this way, the hithertohegemonic commitment to growth can be subverted without any direct confron-tation between pro-growth and anti-growth discourses. This process is illustratedin Figure 1.

Figure 1 also shows a social rearticulatory arc from conventional growth to apost-growth society. The first step in this subversion is to shift the discourse from‘economic growth’ to ‘well-being’ (Barry 2012, Glasson 2013). This is notnecessarily a radical move, because growth is often used as a synonym forsocietal well-being and/or a means to this end. From well-being, it is only ashort step to economic security, because this is fundamental to societal well-being. Economic security in turn allows the switch from a primarily growth-positive to growth-negative framing, because it is generally agnostic about thecommitment to economic growth (Barry 2012, Glasson 2013). It also facilitatesthe move to greater equality, which is a necessary precondition for a post-growthsociety because growth is routinely used as a substitute for income redistribution(Bell 1976, Daly 1977). Economic equality is also by definition a post-growth

14 P. Ferguson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

discourse because growth often exacerbates inequality (Woodard and Simms2006, ILO 2004b, Galbraith 1958). This provides the final link in a possiblesocial subversive rearticulatory arc from conventional economic growth to apost-growth society.

Conclusion

Much of the above analysis is highly speculative, as the present weak articula-tions of the green economy agenda do not necessarily imply a future transforma-tion to a post-growth society (Bina and La Camera 2011). However, the greeneconomy agenda does provide some basic discursive building blocks to beginthis shift. I have here provided an overview of this discursive terrain and

Conventional

economic

growth

Post-growth

Society

Transform-

ational green

Economy

(A-growth)

Economic

Security

(A-growth)

Wellbeing Weak green

economy

(Green growth)

Greater Equality

Strong green

economy

(Limits to

growth)

Growth Positive

Growth Negative

Social Rearticulation Ecological Rearticulation

Figure 1. Subversive rearticulation of the commitment to economic growth. (Partlyadapted from Glasson 2013.)

Environmental Politics 15

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

proposed a strategy for rearticulating the green economy agenda in a post-growthdirection. At this stage, it appears that the green economy, together with therelated discourse of economic security and alternative measures of progress andsocietal well-being, have the potential to achieve what sustainable developmenthas been unable to do, and to grapple with the fundamental problem of the costsof and limits to conventional economic growth. Whilst presently the greeneconomy largely constitutes business as usual, it retains the latent potentialto transform itself from a weak to a strong articulation, and thus towards apost-growth society.

However, this will only be possible if a ‘green economy community ofpractice’ emerges. Such a community would recognise that conventionaleconomic growth and mass consumption are not the most efficacious means toachieve societal well-being and progress, that growth often undermines environ-mental and economic security, and that growth and consumption face biophysicallimits. Given widespread disillusionment with the growth-based neoliberal sys-tem in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and the increasing prominence ofclimate change in mainstream political discourse in many countries, the time maybe right for such a bloc to materialise. This may be especially the case in thosesocieties that have been most impacted by the economic downturn and/or thosethat face the greatest risks from economic and environmental insecurities.

AcknowledgementsThe author thanks Robyn Eckersley, Melanie Lowe, Jim Ferguson, Ben Glasson, and theanonymous reviewers for their considered and useful suggestions on drafts of this article.

ReferencesAdler, E., 2008. The spread of security communities: communities of practice, self-

restraint, and NATO’s post-cold war transformation. European Journal ofInternational Relations, 14 (2), 195–230. doi:10.1177/1354066108089241

Adler, E. and Pouliot, V., 2011. International practices. International Theory, 3 (1), 1–36.doi:10.1017/S175297191000031X

Andersson, J.O. and Lindroth, M., 2001. Ecologically unsustainable trade. EcologicalEconomics, 37 (1), 113–122. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00272-X

Argyle, M., 1999. Causes and correlates of happiness. In: D. Kahneman, E. Diener and N.Schwarz, eds. Well-being: the foundations of hedonic psychology. New York, NY:Russel Sage Foundation, 353–373.

Banerjee, S., 2003. Who sustains whose development? Sustainable development andthe reinvention of nature. Organization Studies, 24 (1), 143–180. doi:10.1177/0170840603024001341

Bär, H., Jacob, K., and Werland, S., 2011. Green economy discourses in the run-up to Rio2012. Berlin: Freie Universitat Berlin, Environmental Policy Research Centre.

Bardi, U., 2011. The limits to growth revisited. New York, NY: Springer.Barnett, J., 2001. The meaning of environmental security: ecological politics and policy in

the new security era. London: Zed Books.

16 P. Ferguson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

Barry, J., 2007. Towards a model of green political economy: from ecological modernisa-tion to economic security. International Journal of Green Economics, 1 (3/4),446–464. doi:10.1504/IJGE.2007.013071

Barry, J., 2012. The politics of actually existing unsustainability: human flourishing in aclimate-changed, carbon-constrained world. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Bateman, I., et al., 2011. Economic analysis for ecosystem service assessments.Environmental and Resource Economics, 48 (2), 177–218. doi:10.1007/s10640-010-9418-x

Beck, U., 1992. Risk society: towards a new modernity. London: Sage.Bell, D., 1976. The cultural contradictions of capitalism. London: Heinemann.Bina, O. and La Camera, F., 2011. Promise and shortcomings of a green turn in recent

policy responses to the ‘double crisis’. Ecological Economics, 70 (12), 2308–2316.doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.06.021

Bowen, A., et al., 2009. An outline of the case for ‘green’ stimulus. London: Centre forClimate Change Economics and Policy/Grantham Reasearch Institute on ClimateChange and the Environment Working Group.

Bowen, A. and Fankhauser, S., 2011. The green growth narrative: paradigm shift or just spin?Global Environmental Change, 21 (4), 1157–1159. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.07.007

Brekke, K.A. and Howarth, R., 2002. Status, growth and the environment: goods assymbols in applied welfare economics. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Cato, M.S., 2009. Green economics. London: Earthscan.Christoff, P., 1996. Ecological modernisation, ecological modernities. Environmental

Politics, 5 (3), 476–500. doi:10.1080/09644019608414283CNA, 2007. National security and the threat of climate change. Virginia: Alexandria.Cudworth, E. and Hobden, S., 2011. Beyond environmental security: complex systems,

multiple inequalities and environmental risks. Environmental Politics, 20 (1), 42–59.doi:10.1080/09644016.2011.538165

Dalby, S., 2009. Security and environmental change. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.Daly, H., 1977. Steady-state economics: the economics of biophysical equilibrium and

moral growth. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman.Daly, H., 1999. Uneconomic growth: in theory, in fact, in history, and in relation to

globalisation. In: H. Daly, ed. Ecological economics and the ecology of economics:essays in criticism. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 8–24.

Daly, H., 2007. Ecological economics and sustainable development. Cheltenham: EdwardElgar.

Dasgupta, P., 2009. The welfare economic theory of green national accounts. Environmentaland Resource Economics, 42 (1), 3–38. doi:10.1007/s10640-008-9223-y

de Bruyn, S., 2000. Economic growth and the environment: an empirical analysis.Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

de Mooij, R.A., 2002. The double dividend of an environmental tax reform. In: J.C.J.M.van den Bergh, ed. Handbook of environmental and resource economics. Cheltenham:Edward Elgar, 293–306.

Deluca, K., 1999. Articulation theory: a discursive grounding for rhetorical practice.Philosphy and Rhetoric, 32 (4), 334–348.

Dietz, S., 2008. A long-run target for climate policy: the Stern Review and its critics.London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment/Department of Geography and Environment, London School of Economics andPolitical Science.

Dobson, A., 2007. Green political thought. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Routledge.Dryzek, J., et al., 2003. Green states and social movements: environmentalism in the

United States, United Kingdom, Germany and Norway. Oxford, UK: OxfordUniversity Press.

Environmental Politics 17

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

Easterlin, R., 1974. Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empiricalevidence. In: P. David and M. Reder, eds. Nations and households in economicgrowth: essays in honour of Moses Abramovitz. New York, NY: Academic Press,89–125.

Easterlin, R., 1995. Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journalof Economic Behavior and Organization, 27 (1), 35–47. doi:10.1016/0167-2681(95)00003-B

Ekins, P., 1994. Sustainable development and the economic growth debate. In:B. Burgenmeier, ed. Economy, environment, and technology: a socio-economicapproach. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 121–137.

Ekins, P., 2000. Economic growth and environmental sustainability: the prospects forgreen growth. London: Routledge.

Ekins, P. and Speck, S., eds., 2011. Environmental tax reform: a policy for green growth.Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

European Commission, 2009. GDP and beyond: measuring progress in a changing world.Brussels: European Commission.

Ferguson, P., 2013. Post-growth policy instruments. International Journal of GreenEconomics, 7 (4), 405–421. doi:10.1504/IJGE.2013.058560

Frey, B. and Stutzer, A., 2002. Happiness and economics: how the economy and institu-tions affect human well-being. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Galbraith, J.K., 1958. The affluent society. London: Penguin.Garnaut, R., 2008. The Garnaut climate change review: final report. Port Melbourne,

Victoria: Cambridge University Press.Geels, F., 2013. The impact of the financial-economic crisis on sustainability transitions:

financial investment, governance and public discourse. Environmental Innovation andSocietal Transitions, 6, 67–95. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2012.11.004

Gertner, J., 2010. The rise and fall of the GDP. New York Times, 10 May.Glasson, B., 2013. What are the limits to reform environmentalism? Rearticulating

ecological modernisation towards ecologism. Paper presented at the WesternPolitical Science Association Meeting, Hollywood, California.

Goulder, L., 1995. Environmental taxation and the double dividend: a reader’s guide.International Tax and Public Affairs, 2 (2), 157–183.

Hajer, M., 1995. The politics of environmental discourse: ecological modernization andthe policy process. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Hallegatte, S., et al., 2011. From growth to green growth: a framework. Washington, DC:World Bank.

Hamilton, K. and Ruta, G., 2009. Wealth accounting, exhaustible resources and socialwelfare. Environmental and Resource Economics, 42, 53–64. doi:10.1007/s10640-008-9235-7

Harris, J., 2013. Green keynesianism: beyond standard growth paradigms. MeldfordMassachusettes: Global Development and Environment Institute/Tufts University.

Heinberg, R., 2011. The end of growth. Gabriola Island, British Columbia: New SocietyPublishers.

Hepburn, C. and Bowen, A., 2013. Prosperity with growth: economic growth, climatechange and environmental limits. In: R. Fouquet, ed. Handbook on energy andclimate change. Cheltenham: Edgar Elgar, 617–638.

Herring, H., 2006. Energy efficiency – a critical view. Energy, 31 (1), 10–20. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2004.04.055

Hirsch, F., 1977. Social limits to growth. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.Houser, T., Mohan, S., and Hellmayr, R., 2009. A green global recovery? Assessing US

economic stimulus and the prospects for international coordination. Washington, DC:Peterson Institute for International Economics/World Resources Institute.

18 P. Ferguson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

Huberty, M., et al., 2011. Shaping the green growth economy: a review of the publicdebate and the prospects for green growth. Copenhagen: Green Growth Leaders.

Hurley, S.F. and Matthews, J.P., 2008. Cost-effectiveness of the Australian nationaltobacco campaign. Tobacco Control, 17 (6), 379–384. doi:10.1136/tc.2008.025213

Inglehart, R., 1996. The diminishing utility of economic growth: from maximizingsecurity toward maximizing subjective well‐being. Critical Review, 10 (4), 509–531.doi:10.1080/08913819608443436

International Labour Organization (ILO), 2004a. Definitions: what we mean when we say‘economic security.’ International Labour Organization. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/public/english/protection/ses/download/docs/definition.pdf [Accessed 10 September2012].

International Labour Organization (ILO), 2004b. Economic security for a better world.Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Jackson, T., 2009. Prosperity without growth: economics for a finite planet. London:Earthscan.

Jackson, T. and Victor, P., 2011. Productivity and work in the ‘green economy’: sometheoretical reflections and empirical tests. Environmental Innovation and SocietalTransitions, 1 (1), 101–108. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2011.04.005

Jacobs, M., 1991. The green economy: environment, sustainable development and thepolitics of the future. London: Pluto Press.

Jacobs, M. 2012. Green growth: economic theory and political discourse. London:Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy Working Paper No. 108/Grantham Reasearch Institute on Climate Change and the Environment WorkingPaper No. 92.

Jänicke, M., 2012. Green Growth: from a growing eco-industry to economic sustainabil-ity. Energy Policy, 48, 13–21. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2012.04.045

Jänicke, M. and Jacob, K., 2009. A third industrial revolution: solutions to the crisis ofresource intensive growth. Berlin: Freie Universitat Berlin, Environmental PolicyResearch Centre.

Jha, P. and Chaloupka, F., 1999. Curbing the epidemic: governments and the economics oftobacco control. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Laclau, E. and Mouffe, C., 2001. Hegemony and socialist strategy: towards a radicaldemocratic politics. 2nd ed. London: Verso.

Lagarde, C., 2012. Remarks of the managing director of the International Monetary Fund:back to Rio - the road to a sustainable economic future. Washington, DC:International Monetary Fund.

Lawn, P., 2006. An assessment of alternative measures of sustainable economic welfare.In: P. Lawn, ed. Sustainable development indicators in ecological economics.Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 139–165.

Lawn, P. and Sanders, R., 1999. Has Australia surpassed its optimal macroeconomicscale? Finding out with the aid of ‘benefit’ and ‘cost’ accounts and a sustainable netbenefit index. Ecological Economics, 28 (2), 213–229. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(98)00049-4

Layard, R., Mayraz, G., and Nickell, S., 2008. The marginal utility of income. Journal ofPublic Economics, 92 (8–9), 1846–1857. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.01.007

Max-Neef, M., 1995. Economic growth and quality of life: a threshold hypothesis.Ecological Economics, 15, 115–118. doi:10.1016/0921-8009(95)00064-X

McManus, P., 1996. Contested terrains: politics, stories and discourses of sustainability.Environmental Politics, 5 (1), 48–73. doi:10.1080/09644019608414247

Meadows, D., et al., 1972. The limits to growth. New York, NY: Universe Books.Meadows, D., Randers, J., and Meadows, D., 2004. Limits to growth: the thirty year

update. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing Company.

Environmental Politics 19

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

Newell, P. and Paterson, M., 2010. Climate capitalism: global warming and the transfor-mation of the global economy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Offer, A., 2006. The challenge of affluence: self-control and wellbeing in the UnitedStates and Britain since 1950. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2013. Economicpolicy reforms 2013: going for growth. Paris: Organisation for EconomicCooperation and Development.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2011. Towards greengrowth. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Parry, I. and Bento, A., 2000. Tax deductions, environmental policy, and the ‘doubledividend hypothesis. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 39 (1),67–96. doi:10.1006/jeem.1999.1093

Paterson, M., Doran, P., and Barry, J., 2006. Green Theory. In: C. Hay, M. Lister, and D.Marsh, eds. The state: theories and issues. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan,135–154.

Patil, P., 2012. Moving beyond GDP: how to factor natural capital into economic decisionmaking. New York, NY: World Bank.

Pearce, D., Markandya, A., and Barbier, E., 1989. Blueprint for a green economy.London: Earthscan.

Rice, J., 2007. Ecological unequal exchange: international trade and uneven utilization ofenvironmental space in the world system. Social Forces, 85 (3), 1369–1392.doi:10.1353/sof.2007.0054

Rist, G., 1997. The history of development: from western origins to global faith. London:Zed Books.

Rogers, K., 1997. Ecological security and multinational corporations. In: P.J. Simmmons,ed. Environmental change and security project report. Washington D.C.: WoodrowWilson Center, 29–36.

Sachs, W., ed., 1992. The development dictionary: a guide to knowledge as power.London: Zed Books.

Saunders, H., 2010. Historical evidence for energy consumption rebound in 30 US sectorsand a toolkit for rebound analysis. Oakland, CA: Breakthrough Institute.

Stein, A., 2008. Neoliberal institutionalism. In: C. Reus-Smit and D. Snidal, eds. TheOxford handbook of international relations. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press,201–221.

Stern, N., 2007. The economics of climate change: the Stern review. Cambridge, UK:Cambridge University Press.

Stern, N. and Rydge, J., 2012. The new energy-industrial revolution and internationalagreement on climate change. Economics of Energy and Environmental Policy, 1 (1),1–19. doi:10.5547/2160-5890.1.1.9

Stiglitz, J., Sen, A., and Fitoussi, J.P., 2009. Report by the commission on the measure-ment of economic performance and social progress. Paris: Commission on theMeasurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress.

Stratton, A., 2010. David Cameron aims to make happiness the new GDP. The Guardian,14 November.

Tamiotti, L., et al., 2009. Trade and climate change. Geneva: World TradeOrganization.

Tienhaara, K., 2014. Varieties of green capitalism: economy and environment in the wakeof the global financial crisis. Environmental Politics, 23 (2), 187–204. doi:10.1080/09644016.2013.821828

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 1994. Human development report.New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

20 P. Ferguson

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 2011. Towards a green economy:pathways to sustainable development and poverty eradication. Nairobi, Kenya:United Nations Environment Programme.

United Nations Statistics Division, 2012. Measurement framework in support of sustain-able development and green economy policy: briefing note on the system of environ-mental-economic accounts. New York, NY: United Nations Statistics Division.

United Nations, 2012. The future we want: declaration of the Rio + 20: United Nationsconference on sustainable development. Rio de Janeiro: United Nations.

United States Department of Defense, 2010. Quadrennial defense review report.Washington, DC: United States Department of Defense.

Urhammer, E. and Røpke, I., 2013. Macroeconomic narratives in a world of crises: ananalysis of stories about solving the system crisis. Ecological Economics, 96, 62–70.doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.10.002

van den Bergh, J.C.J.M. and Kallis, G., 2012. Growth, a-growth or degrowth to staywithin planetary boundaries? Journal of Economic Issues, 46 (4), 909–920.doi:10.2753/JEI0021-3624460404

Victor, P., 2008. Managing without growth: slower by design not disaster. Cheltenham:Edgar Elgar.

Vos, R., 1997. Competing approaches to sustainability: dimensions of the controversy. In:S. Kamieniecki and G. Gonzalez, eds. Flashpoints in environmental policymaking.Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Watts, J. and Ford, L., 2012. Rio + 20 Earth summit: campaigners decry final document.The Guardian, 23 June.

Woodard, D. and Simms, A., 2006. Growth isn’t working. London: New EconomicsFoundation.

World Bank, 2012. Inclusive green growth: the pathway to sustianable development.Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank, 2013. Towards a sustainable energy future for all: directions for the worldbank group’s eneregy sector. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Trade Organization (WTO), 2012. Harnessing trade for sustainable developmentand a green economy. Geneva: World Trade Organization.

Zenghelis, D., 2012. A strategy for restoring confidence and economic growth throughgreen investment and innovation. London: Centre for Climate Change Economics andPolicy/Grantham Reasearch Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

Environmental Politics 21

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

The

Uni

vers

ity O

f M

elbo

urne

Lib

rari

es]

at 1

5:07

19

May

201

4