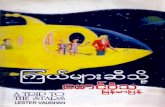

Prospect Analysis for Myanmar

Transcript of Prospect Analysis for Myanmar

Myanmar: From Pariah state toimmense potential

Written by:Souvik Aswad

Ayesha Sabrina

Muntasir Tahmeed

Zeba Samiha

1 | P a g e

Contents1 Background.....................................................31.1 An overview of transition....................................41.1.1 Pre-colonial and Colonial era.............................41.1.2 The era of chaos..........................................41.1.3 Economic liberalization (2011-present)....................5

2 The Opportunity Landscape:.....................................63 Analyzing the Growth Launchpad.................................73.1 Comparison with Asia.........................................73.2 Strategic Location Advantage................................103.3 ASEAN’s Integration.........................................113.4 Shift Towards Non-Agrarian economy..........................12

4 Key Propellers behind Growth Opportunity......................134.1 The GREENFIELD ADVANTAGE....................................134.2 Committed support of development partners...................134.3 Global Catch Up Effect......................................14

5 Sustainable Growth Sectors....................................155.1 Diversification: The Growth Mantra..........................15

6 Potential opportunity areas...................................186.1 Tourism.....................................................186.2 Aviation....................................................196.3 Low cost manufacturing hub..................................206.4 The next energy hub.........................................216.5 Precious stone export.......................................226.6 Business hub for MNCs.......................................23

7 Critical success factors......................................247.1 Sector wise investment mapping..............................247.1.1 Agriculture..............................................247.1.2 Energy and mining........................................247.1.3 Manufacturing............................................24

2 | P a g e

7.1.4 Infrastructure...........................................247.2 Reforms.....................................................257.2.1 Legal environment of business............................257.2.2 Exchange rate review.....................................267.2.3 Investment-Savings ratio.................................277.2.4 Banking system...........................................27

7.3 Strategic policies..........................................287.3.1 Alliance with neighbors..................................287.3.2 Balanced trade diversification...........................307.3.3 Special economic zone....................................30

8 Conclusion....................................................319 References....................................................319.1 List of articles............................................319.2 List of research papers.....................................32

1 BackgroundMyanmar, also known as Burma, was long considered a pariah state,isolated from the rest of the world with an appalling humanrights record. A predominantly Buddhist nation of 60 million, ithas been undergoing unprecedented political transformation aftera half-century of harsh military rule which formally ended in2011. For most of its independent years from the British, thecountry’s myriad ethnic groups have been involved in one of the

3 | P a g e

world’s longest-running unresolved civil wars. The dissolution ofthe military junta following a 2010 general election, has takensteps toward relinquishing control of the government, improvingforeign relation leading to the easing of trade and othereconomic sanctions that had been previously imposed by EU and theUSA.

1.1 An overview of transition

1.1.1 Pre-colonial and Colonial era

Pre-colonial economy in Burma was essentially a subsistenceeconomy, with the majority of the population involved in riceproduction and other forms of agriculture. Land was technicallyowned by the Burmese monarch. Moreover, exports, along with oilwells, gem mining and teak production were controlled by themonarch. Burma was vitally involved in the IndianOcean trade. Logged teak was a prized export that was used inEuropean shipbuilding, because of its durability, and became thefocal point of the Burmese export trade from the 1700s to the1800s. During British occupation, Burma was the second wealthiestcountry in Southeast Asia after the Philippines. It was also oncethe world's largest exporter of rice. During Britishadministration, Burma supplied oil through the Burmah OilCompany. Burma also had a wealth of natural and labor resources.It produced 75% of the world's teak and had a highly literatepopulation. The country was believed to be on the fast track todevelopment.

1.1.2 The era of chaos

The exit of the British should have had opened up an opportunityfor the country, like it did for India. But the prospects endedrudely when the Second World War broke out and the Japaneseunleashed their characteristic aggression. After a parliamentarygovernment was formed in 1948, Prime Minister U Nu attempted to

4 | P a g e

make Burma a welfare state and adopted central planning. Riceexports fell by two thirds and mineral exports by over 96%. Planswere partly financed by printing money, which led to inflation.From 1962 to 2011, the country was ruled by a military junta thatsuppressed almost all dissent and wielded absolute power in theface of international condemnation and sanctions. The generalswho ran the country stood accused of gross human rights abuses,including the forcible relocation of civilians and the widespreaduse of forced labour, including children. Though it gotindependence from colonial rule about a year after India, thecountry descended into chaos following a military coup in 1962.Thereafter, it went into isolation, abetted no doubt by the factthat subsequently brutal economic sanctions were put in place.Consequently, it was as though time froze on Myanmar. The 1962coup d'état was followed by an economic scheme called the BurmeseWay to Socialism, a plan to nationalize all industries, with theexception of agriculture. The catastrophic program turned Burmainto one of the world's most impoverished countries. Burma'sadmittance to Least Developed Country status by the UnitedNations in 1987 highlighted its economic bankruptcy. After 1988, the regime retreated from totalitarian socialism. Itpermitted modest expansion of the private sector, allowed someforeign investment, and received much needed foreignexchange. The economy is rated in 2009 as the least free inAsia (tied with North Korea). The market rate of its currency wasaround two hundred times below the government-set rate in2006.Inflation averaged 30.1% between 2005 and 2007. Inflation isa serious problem for the economy. In April 2007, the NationalLeague for Democracy organized a two-day workshop on the economy.The workshop concluded that skyrocketing inflation was impedingeconomic growth. "Basic commodity prices have increased from 30%to 60% since the military regime promoted a salary increase forgovernment workers in April 2006," said Soe Win, the moderator ofthe workshop. Following these devastating policies and violation

5 | P a g e

of basic rights, many nations, including the United States andCanada, and the European Union, imposed investment and tradesanctions on Burma.

1.1.3 Economic liberalization (2011-present)

Since 2011, the country has drawn massive international interestfor its dramatic political and economic reforms. The firstgeneral election in 20 years was held in 2010. This was hailed bythe junta as an important step in the transition from militaryrule to a civilian democracy The government of President TheinSein has released hordes of political prisoners, relaxed mediacensorship and opened the economy to foreign investment. Theholding of the ASEAN gavel thus symbolises Myanmar's re-entry tothe global community. At the same time, it gives Myanmar anotheropportunity to demonstrate that it is committed to democracy andwider integration with the world outside. US Secretary of StateHillary Clinton made a landmark visit in December 2011 - thefirst by a senior US official in 50 years - during which she metboth President Thein Sein and Aung San Suu Kyi. The newly re-elected President Obama followed suit in November 2012, andhosted President Thein Sein in Washington in May 2013, signallingthe country's return to the world stage. The EU followed the USlead, lifting all non-military sanctions in April 2012 andoffering Myanmar more than $100m in development aid later thatyear

In March 2012, a draft foreign investment law emerged, the firstin more than 2 decades. This law would oversee unprecedentedliberalization of the economy. Foreigners will no longer requirea local partner to start a business in the country, and will beable to legally lease land. The draft law also stipulates thatBurmese citizens must constitute at least 25% of the firm'sskilled workforce, and with subsequent training, up to 50-75%. The draft includes a proposal to transform the Myanmar

6 | P a g e

Investment Commission from a government-appointed body into anindependent board. This could bring greater transparency to theprocess of issuing investment licenses, according to the proposedreforms drafted by experts and senior officials.

With sanctions no longer in place, life has become a lot lesscomplicated for international companies and countries to pursuetheir interest. The Japanese (encouraged on by the US), whoserivalry with China is now acquiring a new form, are taking a leadrole. Plans are afoot to provide connectivity across the countryeven as efforts are on to put in place the requisiteinfrastructure. As the McKinsey report rightly points out, thelate bloomer factor may be to Myanmar’s advantage, especially asit is the first country to really look at such a fundamentaltransformation by exploiting the power of the digital economy.

2 The Opportunity Landscape:Myanmar1 is at a pivotal moment. The government has ushered in aseries of political and economic reforms after decades ofauthoritarianism, a revived peace process is under way to addresson-going ethnic conflicts and communal violence, and thefoundations of an open market economy are being laid after yearsof isolation. There is everything to play for—but also a majorrisk of disappointment. Today, Myanmar is enjoying a groundswellof goodwill from an international community that is keen tosupport the country in its process of change and opening.Investors are understandably interested in this highly unusualand potentially promising market prospect. Myanmar is at theheart of the world’s fastest-growing region and begins itstransformation in the digital age. Severe under-development,

1 The ruling military junta changed the name of the country from Burma to Myanmar in 1989, and this remains the official name today. For this reason, despite the fact that many parties inside and outside the country do not recognize the nomenclature, wehave opted to use Myanmar from this segment of the report

7 | P a g e

after nearly a century of economic stagnation, poses fundamentalchallenges for an economy that now only contributes 0.2 percentof Asia’s GDP. But it also gives Myanmar an opportunity to useits greenfield situation to leapfrog over intermediate stages ofeconomic development and to create sufficient jobs to meet thehigh expectations of its people.

By developing a diversified set of sectors, Myanmar has thepotential to more than quadruple the size of its economy to over$200 billion by 2030. But if it fails to build a compellinggrowth plan and implement it effectively, today’s goodwill andcautious optimism could evaporate all too rapidly.

Much uncertainty remains. Investors are actively consideringMyanmar, but many want reassurance that the government canresolve ethnic and communal violence, maintain its momentumtowards political and economic reform, and ease constraints ondoing business. Those political and economic choices willdetermine the sustainability of change and the level of interestfrom investors and supporters—and therefore the success ofMyanmar’s economic transformation. As it modernizes andliberates its economy, Myanmar offers opportunities for

8 | P a g e

investors, both foreign and domestic, in virtually all sectors.The services sector, in particular, economy. Telecommunications,including mobile telephony, is in urgent need of investment.Similarly, the travel and tourism sector possesses huge potentialgiven the country’s natural and cultural features and sites,coupled with the pent-up interest of travelers after decades ofMyanmar’s relative isolation. A tourism boom can generateinvestment in transport, hotels, restaurants, arts and culture,and travel. Agriculture offers considerable potential in basicproduction and agro-processing, including for export.Complementary areas of marketing, storage, transport, logistics,and the provision of inputs such as machinery and fertilizers arealso ripe for investment.

3 Analyzing the Growth Launchpad

3.1 Comparison with Asia Between 1900 and 1990, the global economy achieved average GDPgrowth of 3 percent a year. But Myanmar’s growth was strikinglylow, estimated at only 1.6 percent a year. During this period,global per capita GDP quadrupled; Myanmar’s was virtuallystagnant.

9 | P a g e

Since 1990, Myanmar’s growth has picked up, but it is still muchweaker than the growth rates common across Asia. From 1990 to2010, we estimate that Myanmar’s GDP grew at an average of 4.7percent a year, which was slower than the average annual growthof nearly 6 percent posted by its Asian neighbors.

When it comes to GDP, Myanmar’s per capita GDP grew at a compoundannual growth rate of 2.7 percent, compared with the Asianaverage of 4.2 percent. Myanmar’s low per capita GDP is largelydue to the fact that it has missed out on Asia’s remarkableimprovement in labour productivity. On average, a worker inMyanmar adds only $1,500 of economic value in a year of work,around 70 percent less than the average of seven other Asianeconomies. The modest acceleration in Myanmar’s GDP growth overthe past 20 years has been due largely to an expanding

10 | P a g e

population, rather than productivity growth. It is weakproductivity that underlies Myanmar’s low per capita GDP.

This productivity gap exists across all sectors but alsoreflects the fact that Myanmar’s economy continues to rely veryheavily on agriculture, a low-productivity sector in mostcountries. Indeed, in Myanmar, agriculture’s share of GDPactually rose from 35 percent in 1965 to 44 percent in 2010—whilethat share was dropping sharply in other Asian economies as theydeveloped their manufacturing and service sectors. In the rest of

11 | P a g e

Asia, the average share of agriculture in overall GDP in 20102was 12 percent.

Myanmar’s economy has not yet made the usual structural shiftfrom agriculture to manufacturing and services that economiesundergo, and has remained largely dependent on agriculture. In2010, agriculture in Myanmar generated 44 percent of GDP. Theeconomic structure of other Asian economies has shifted in theopposite direction with the contribution of agriculture to GDPfalling to or below 15 percent in Thailand, the Philippines,Indonesia, and Malaysia as then contribution of manufacturing andservices grew strongly

The rest of the world has seen economic growth partially drivenby a ballooning consumer class—people with incomes of more than$10 a day at purchasing power parity (PPP) who can spend money ondiscretionary goods and services as well as basic necessities—butbecause of its long history of weak growth, Myanmar remains avery poor country. Today, 35 percent of the world’s population

2 1990 Geary-Khamis (PPP) US dollar. See Angus Maddison, Historical statistics of the world economy: 1–2008 AD, 2008

12 | P a g e

belongs to the global consuming class, and of the 2.5 billionpeople in the global consuming class, 40 percent, or one billion,live in Asia. Myanmar’s population falls into this category.

3.2 Strategic Location AdvantageMyanmar has long been cut off from political, economic, andtrading relationships and has not been able to participate inregional integration and capitalize on its ideal position in theworld’s fastest-growing regional economy. Now that Myanmar’seconomy is opening up, there is potential to become a majorexporter, especially of agriculture and food products, to many ofits regional neighbors that are experiencing strong demand andrapid growth. Consider the fact that Myanmar borders Bangladesh,China, India, Laos, and Thailand—home to 40 percent of theworld’s population. Bangladesh alone has a population of 150million, and Thailand and Laos have a combined population of 75million people. China’s Yunnan province to the north-east ofMyanmar is home to an additional 46 million people. The Indianprovinces bordering Myanmar as well as those across the AndamanSea have 240 million more people.

13 | P a g e

For instance, transporting a ton of freight by ship from Chennaito Shanghai is ten times cheaper than shipping it to Myanmar andthen trucking it overland to China’s eastern seaboard

3.3 ASEAN’s IntegrationMyanmar can also take advantage of powerful external trends.ASEAN integration has entered an active phase, and there isalready intense interest in Myanmar’s prospects among investors,companies, and foreign governments and intergovernmentalorganizations. Many countries are setting up embassies in thecountry after numerous years of absence. Myanmar will be in theinternational spotlight as host of the World Economic Forum in

14 | P a g e

Myanmar is closeto a market of morethan half a billionpeople and, by2025, will bewithin a five-hourplane ride of 2.5billion members ofthe consumingclass. In additionto this exportpotential,observers haveoften suggestedthat Myanmar couldbecome a trade hubon the crossroadsof Asia. However,it remainsquestionable

June 2013, host of the 20133 Southeast Asian Games in December,and chair of ASEAN in 2014. Myanmar’s new openness is well timedto take advantage of the establishment of the ASEAN EconomicCommunity (AEC) free trade zone at the end of 2015. Plans forenhancing regional connectivity and requirements for theliberalization of services and investment ahead of the 2015deadline should help to entrench and speed up Myanmar’s reform.In the medium term, Myanmar can benefit from strengthening tradeand investment ties and financial cooperation through suchinitiatives as the ASEAN+3 Asian Bond Markets Initiative and theCredit Guarantee and Investment Facility, which could mobilizesavings throughout Asia and help to source funds for Myanmar’sinvestment needs. ASEAN is not the only useful regional forum.Myanmar is a long-standing member of the Greater MekongSubregion, a forum for economic cooperation that aims tofacilitate high-priority sub-regional projects in transport,energy, telecommunications, the environment, the development ofhuman resources, tourism, trade, private-sector investment, andagriculture.

3.4 Shift Towards Non-Agrarian economyMyanmar’s labor force is continuing to make a contribution to GDPgrowth but at a decelerating rate in the period to 2030. Between1990 and 2010, employment grew by 3.2 percent a year, drivenmainly by the growth in the working-age population. However,growth in that population is expected to weaken between 2010 and2030 to a compound average rate of only 1 percent. It istherefore vital that Myanmar acts decisively to boost growth inlabor productivity. In this case a shift towards other sectorsexcept agriculture might bring about positive changes. Usually ashift from agriculture to manufacturing and services, and thecorresponding shift from a rural to an urban economy, is one of

3 Shaohua Chen and Martin Ravallion, An update to the World Bank’s estimates of consumption poverty in the developing world, briefing note, Development Research Group, World Bank, January 2012.

15 | P a g e

the most critical drivers of growth in most countries. Roughly,each 15 percent increase in the manufacturing and services shareof GDP is associated with a doubling of per capita GDP.31 In thecase of Vietnam, a movement of workers from agriculture intoother sectors accounted for about one-third of Vietnam’s growthbetween 2005 and 2010. From 2000 to 2010, the share ofagriculture in Vietnam’s employment dropped by 13 percentagepoints, while the share of workers employed in industry rose by9.6 points and in services by 3.4 points. In the same period,Vietnam’s per capita GDP (PPP) more than doubled. Average labourproductivity in Vietnam’s industry today is almost six times ashigh as in agriculture, and services productivity is four timesas high. As the share of these high-productivity sectorsincreased, agriculture’s contribution to Vietnam’s GDP fell byhalf, from 40 percent in 1995 to 20 percent in 2010.32 In thesesame years, Vietnam’s real GDP grew by 7 percent a year from $38billion to $106 billion.

16 | P a g e

4 Key Propellers behind Growth Opportunity

4.1 The GREENFIELD ADVANTAGE

Myanmar’s current state of development is undoubtedly aconsiderable challenge but could also prove to be a powerfuladvantage by allowing Myanmar to leapfrog over intermediatestages of development and accelerate growth. The fact thatMyanmar is beginning its transformation decades after some of itsAsian neighbours means that it can learn from their experience—good and bad. Moreover, Myanmar is starting its development in apost-Internet world, potentially allowing for a different, andhigher-productivity, approach to delivering public and commercialservices using digital technology. Making the right decisions nowcould lead to high-productivity and energy-efficient systems andinfrastructure for decades to come. Despite the up-frontinvestment, higher productivity and efficiency will save on-goingoperating costs and potentially prevent financial, social, andenvironmental strains emerging. Technology that connects peopleeven in the most remote areas to health care, education, banking,shopping, and other services can be a powerful force for socialand economic inclusivity—a central component of Myanmar’s“people-centred” development.

4.2 Committed support of development partners

The fact that diplomatic relations with many countries around theworld have normalised and that development partners are onceagain fully engaged in Myanmar will boost the country’s potentialto make rapid progress. At the time of writing this report, theinternational community was united in its support of Myanmar’stransition. Donors from across the world have committed tocoordinating their activities through a programme of sustaineddevelopment partnership detailed in the Nay Pyi Taw Accord forEffective Development Cooperation signed in January 2013.

17 | P a g e

The Asian Development Bank and the World Bank settled the issueof Myanmar’s outstanding arrears, and this left the way open forthe Paris Club, Japan, and Norway to grant additional relief.This resulted in a total of $6 billion of debt relief given toMyanmar in January 2013. The government of Myanmar said that ithad met with the Paris Club on January 25 and that agreement wasreached for the cancellation of half of the arrears in twostages, with the rest rescheduled over 15 years with a seven-yeargrace period. In January 2013, the Asian Development Bankannounced a $512 million loan for Myanmar and the World Bankdeclared $440 million in loans. In the same month, theInternational Finance Corporation (IFC), part of the World BankGroup, announced that it was investing $2 million in ACLEDA BankPLC to help set up a new microfinance institution with the aim ofproviding loans to more than 200,000 people by 2020. Myanmar isin discussions to become a member of the Multilateral InvestmentGuarantee Agency, which provides risk guarantees to investors.

4.3 Global Catch Up Effect

The experience of other countries suggests that a high pace ofeconomic development is possible when countries are in “catch-up”mode. Incomes in developing economies are rising faster thanever. Globally, the average time it takes to double per capitaGDP at PPP from $1,300—the level in Myanmar today—to $2,600 hasdropped dramatically from 47 years before 1960 to 17 years in thefirst decade of the new millennium. Asian economies have beatenthis global average by some margin. Many of them further doubledper capita GDP from $2,600 to $5,200 in only 13.5 years onaverage, compared with the global average of 36 years.

In a global comparative study, the Commission on Growth andDevelopment identified 13 countries whose GDP has grown at anaverage of 7 percent a year—the equivalent of a doubling of the

18 | P a g e

economy every decade—for 25 years or longer.4 Many of thesecountries were starting from similar income levels and per capitaGDP as those found in Myanmar today. Many of the 13 economieswere also driven by resources—oil in the case of Oman anddiamonds in the case of Botswana. Several, including China andVietnam, also began their transition as largely closed economies.Indonesia was governed under restrictive policies from 1967 to1988. Like Myanmar, all of these 13 economies stood to benefitfrom the contribution to GDP of a young, growing population.

Based on their experience, Myanmar could aspire to achieve annualGDP growth of 8 percent. We describe this 8 percent rate as“aspirational” reflecting the distance Myanmar would have totravel even from today’s growth rates to achieve it. If GDP wereto grow by 8 percent a year, Myanmar’s GDP would more than

4 Angus Maddison, The world economy: A millennial perspective, Development Centre Studies, Organisationfor Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2001.

19 | P a g e

quadruple from $45 billion in 2010 to over $200 billion in 20305.Myanmar’s per capita GDP, in real terms, would increase 3.5 timesfrom an estimated $760 to $2,950.62 We estimate that this couldlift approximately 18 million people living on less than 1.25 perday in Myanmar out of poverty.

5 Sustainable Growth Sectors

5.1 Diversification: The Growth MantraGrowth cannot come from one sector alone. Myanmar may be able touse its natural resources to its advantage but growth must alsocome from other sectors of the economy. Our analysis suggeststhat four sectors in particular—agriculture, energy and mining,manufacturing, and infrastructure—could be important for drivinggrowth because together they account for almost 85 percent of thetotal growth opportunity in the seven sectors analysed. In termsof employment potential, manufacturing, infrastructure, andtourism are likely to be the most important sectors and couldaccount for 92 percent of the employment potential in the sevensectors.

Overall, the seven sectors could together potentially contributemore than $200 billion to GDP by 2030 and create over ten millionadditional non-agricultural jobs The opportunity in these sevensectors suggests that an 8 percent annual growth rate in theperiod to 2030 is challenging but realistic. We now discuss eachof the seven sectors in turn.

5 Thant Myint-U, Where China meets India: Burma and the new crossroads of Asia, Farrar, Straus and Giroux,2011

20 | P a g e

As the diagram above suggests, export in 2010 was more diversified and hence

comparatively more profitable for Myanmar economy.

22 | P a g e

Export Sectors in 2000

Diversification in 2010

6 Potential opportunity areas

6.1 TourismThe most obvious sector for growth in Myanmar is intourism. Across the region, the tourism and travel sectordirectly provides jobs for more than 9 million people andgenerates 5% of ASEAN’s GDP. In the midst of an economicmetamorphosis, the tourism sector is playing an importantrole in boosting Myanmar’s urban and rural economies. “Lastyear Myanmar received 1.06 million visitors. This year, wehave beenreceivingvisitors witha growth of40%, but wewant to getmore,” notedHtay Aung,UnionMinister ofHotels andTourism ofMyanmar. 6Mostinternationalvisitors arefrom Thailand, followed by China. Forecasters expect thisfigure to rise to 7.5 million by 2020, providing up to 1.4million jobs. The country’s tourism authorities haveunveiled a £320 million plan to take advantage of its newgained image. The initiative hopes to make tourism a“pillar” of Myanmar economy and includes 38 developmentprojects.

6 East Asia joins forces to tap deep regional tourism potential,Global Travel Industry News, June 07, 2013

23 | P a g e

The trend will only continue as more international airlinesopen or increase their routes to Myanmar’s three largestairports in Yangon, Mandalay and Nay Pyi Taw. Myanmar hasmany diverse attractions for tourists, ranging frompristine beaches to snow-capped mountains with ancienttemples scattered all throughout the country. The sector isset to benefit ina big way over thecoming years.Greater regionalintegration, asingle visa, andacross-the-boardstandards in thetourism sector areexpected to boosttrade in ASEAN by10%-20%. Myanmarhas also expressedits commitment toboosting intra-regional trade with a common visa for ASEAN nationals to bemade available in 2014 in the ASEAN smart tourism treatysigned in 2013.

6.2 AviationMyanmar’s aviation market is poised to enter a major periodof growth. Several Asian carriers and airport operatorshave identified near-term opportunities in Myanmar. Theopportunities for all types of carriers – local andforeign, domestic and international, low-cost and fullservice – face no limitations in the medium term as theMyanmar market is now the most underserved market in ASEANand perhaps all of Asia. Myanmar’s two existinginternational airports, at Rangoon and Mandalay, are to bepartially privatised while a recently opened new airport atthe new capital of Naypyitaw will soon start to handle

24 | P a g e

international flights. There are also plans for upgradingseveral domestic airports, many of which lack basicinfrastructure.Major international airport operators are eager toparticipate in expected tenders for the management andexpansion of the airports at Yangon, Mandalay andNaypyitaw. International airport operators also expectMyanmar will eventually seek a foreign company to helpoperate the country’s approximately 30 domestic airports,some of which could be upgraded to internationalfacilities. The old capital Yangon has by far the largestairport in Myanmar. Last year Yangon accommodated 2.5million passengers, including almost exactly 1 milliondomestic passengers and almost 1.5 million internationalpassengers, according to Myanmar Department of CivilAviation data. Myanmar’s second international airport atthe popular tourist destination of Mandalay last yearaccommodated just under 500,000 passengers, including onlyabout 50,000 international passengers. Mandalay currentlyonly has one scheduled international service, to Kunming inChina, but several new international destinations areexpected to be added in the coming months, starting withBangkok. Myanmar’s domestic and international markets have bothshown rapid growth since 2008 with international passengernumbers nearly doubling at the main gateway Yangon over thelast three years. But the rate of growth is expected toaccelerate significantly, starting this year as severalcarriers have unveiled plans to add capacity at Yangon andto a lesser extent Mandalay and Naypyitaw.

6.3 Low cost manufacturing hub

25 | P a g e

When looking at Myanmar’s outsourcing potential today, weshould firstly note prior to sanctions put in place by theUS, the country had a solid manufacturing base with astrong apparel industry.Up until 2004 its garment manufacturing sector reliedheavily on exports to the US. Around 85% of its totalexports wereapparel andtextiles, ofwhich anestimated 25%went to the US.Leading tosanctions, theUS importedapproximatelyUSD $356.4 million and USD $275.7 million from Myanmar in2002 and 2003 respectively.It’s industry continued to deteriorate in 2005 followingChina joining the World Trade Organization. With itsmassive workforce pool and superior supply chain, garmentmanufactures moved production to China. Although this had anegative impact on most Southeast Asian countries, Myanmarwas hit the worst with export values compared to such asthat of Cambodia dropping by 60%. As of 28th July 2012 theUS lifted Myanmar’s general import ban with amendments onthe 7th August restricting the import of ruby, jade andjewelry containing such. Reopening trade has injected a newlease of life into Myanmar’s manufacturing industry.

A reverse swing in low cost labor is also refuelingmanufacturing potential in Myanmar.7 Wage increases inASEAN countries have rose modestly compared to China’saverage annual increases of 10-15%. Although a new minimum7 Can Manufacturing Succeed In Myanmar?, Forbes, October 18, 2012

26 | P a g e

wage bill was approved in March this year, to dateMyanmar’s daily minimum wage rates have not been enacted.Daily rates currently vary anywhere between USD $0.50(National Wages and Productivity Commission) and USD $2.3for certain labour sectors (ASEAN Briefing).Minimum monthly salaries for labour in the developingThilawa SEZ were temporarily increased to around USD $65.Even with a generous national rate coming into effect,Myanmar looks set to offer an attractive lower cost laboursolution to foreign manufacturers compared to China’s dailyminimum wage range of USD $4.7-8.11. With 13 million peoplebetween the ages of 15-28, a minimum wage of just $1.25 perday (plus allowances), and the government’s statedobjective of creating 1 million new jobs by 2015, Myanmarlooks set to command a share of the region’s manufacturingmarket. It’s not just the cheaper and more abundant labor,but the investment and tax incentives the Myanmargovernment is offering for those manufacturers establishedin special economic zones which is attracting interest. Incentives include a 5 year holiday on tax, custom dutyexemptions on imported machinery and equipment as well asthe value of the machinery being considered part of thecapital investment requirement. The Hong Kong Apparel Society and the Hong Kong TradeDevelopment Council recently continued talks forestablishing a special Hong Kong Industrial Zone that willallow 50-80 manufacturers to set up within the next 2years. Key export markets will be Japan and South Koreawhich turnover approximately USD $348 million and USD $232million each year respectively. Also, latest signs ofacceptance over Myanmar’s manufacturing potential come fromthe EU. Earlier this July, Myanmar was reinstatement in theEU’s Generalized System of Preferences (EU GSP) withretrospective effect from 13th June 2012. All productsoriginating in Myanmar, except ammunition and arms willbenefit from full duty-free and quota-free access to EUmarkets.

27 | P a g e

6.4 The next energy hub Naturally blessed, Myanmar has 7.8 tcf of proven natural gas reserves according to BP Plc data, and is worth about $75 billion at benchmark prices for gas futures traded in the U.K. The U.S. Energy Information Administration estimates 10 tcf of proven reserves. Myanmar, as per official statistics, is also estimated to have 3.2 billion barrels of recoverable crude oil reserve. It has three mainlarge offshore oil and gas fields and 19 onshore ones whichproduced 421 billion cubic feet (bcf) of hydrocarbon in 2011. Gas now accounts for more than 90% of Myanmar’s hydrocarbon production (of which over 80 percent is exported to Thailand) and is expected to exceed 2.1 bcf by 2015. In 2011, the Myanmar Ministry of Energy (MOE) offered18 onshore blocks for bidding and has awarded eight of these to foreign firms. In January 2013, the MOE put up a further 18 onshore blocks for tender, and another 30 offshore blocks in April 2013. The rounds have attracted significant interest, with over 75 letters of interest submitted for the onshore blocks. Myanmar’s first offshore licensing round in more than 20 years is expected in the second half of 2013, having been delayed from late 2012. The foreign investment in Myanmar's oil and gas sector had reached $14.372 billion at the end of February 2013, accounting for 34.14 percent of the country's foreign investment. The foreign investment will increase in the future as Myanmar prepares to bid out more of its offshore and onshore blocks for exploration to oil majors.

One of the most significant achievements in its energyexport scenario has been the gas pipeline project withChina. The Myanmar-China natural gas pipeline (Myanmarsection) commenced delivery of natural gas to the PeoplesRepublic of China (PRC) after it was inaugurated by MyanmarVice President U Nyan Tun at Mandalay on July 28, 2013.The pipeline is part of the Myanmar-China Oil and Gas

28 | P a g e

Pipeline project, which also includes a crude oil pipeline.The $2.5 billion pipeline project (Myanmar and Chinasections) will cover a total distance of 2,500 km,including 793 km in Myanmar and 1,727 km in PRC. The gaspipeline has been designed for an annual throughput of 12billion cubic meters. The transmission capacity of thecrude oil pipeline on the Myanmar side is designed at 22million tons per year. The gas pipeline has beenconstructed as part of an agreement signed betweenPetroChina and the Myanmar government for the supply of 6.5trillion cubic feet (tcf) of natural gas to the PRC over a30 year period. The natural gas is being exported from theShwe gas project in the Rakhine Basin, which could have apeak production capacity of 500 million cubic feet per day.India, Thailand are also attempting to take advantage ofmyanmar’s huge energy reserve which might translate into aregional battle for energy security in the next decade. Ifchosen wisely Myanmar can only benefit from these deals asthe next energy hub of south east Asia while injecting thegains in its internal development.

6.5 Precious stone export

Myanmar is particularly famous for its ruby, jade, andsapphire stones that fetch record-breaking prices atinternational auctions. However, many mines in the countryare controlled by the military or close associates,including some people who are targeted by US sanctionsestablished years ago to punish the country's harshmilitary regime. (Many of those rules have been loosenedover the past two years, in response to political reforms,but some restrictions on new Myanmar stones remain.) Stonescan also come from fortune seekers whose identities arelargely unknown outside of their home bases. Still, whileit's hard to track the industry's growth, experts say theprices have increased significantly in recent years,largely because supply is erratic. Robert Genis, an

29 | P a g e

Arizona-based gem hunter and dealer who got his start inthe 1970s, says high-grade Myanmar rubies have quadrupledin retail value to more than $US40,000 a carat since themid-1990s.8 Colombian emeralds have roughly doubled since alow in the early 2000s. Hughes, who has trekked across 30or more countries for stones and now lives in Bangkok, saysjade prices have shot up tenfold over the past five years,due largely to surging demand in China, though prices haveeased recently. More good news await the country when itcomes to prospects of exporting its precious stones.Gemfields, a London based gem company already produces 20per cent of the world's emeralds, from a large mine it co-owns in Zambia. The company says it has as much as 40 percent of the global amethyst supply, and it is starting toproduce rubies from a major deposit in Mozambique.Gemfields is keen to expand elsewhere - including inMyanmar, if the government there continues its reforms andthe human-rights situation improves.

6.6 Business hub for MNCs

Foreign businesses are ramping up interest in the long-isolated but potentially lucrative market of Myanmar, assigns of a thaw between its government and Western leadersraise hopes of a possible end to Western sanctions. Fornow, the push is confined mainly to Asian companies thataren't covered by tough sanctions imposed by the U.S. andEurope since the late 1990s to punish Myanmar for its poorhuman-rights record. Some investors held back because ofconcerns about risks to their reputations, while othersdoubted the opportunities were worth pursuing and now arechanging their minds.

8 Romancing the stones in Myanmar, The Australian, August 16, 2013

30 | P a g e

Meanwhile, Western companies are looking for ways to getback in, though few are willing to discuss plans in publicor in depth because of a possible backlash from customerswho remain skeptical about recent reforms in the country.Among the Western brands making early inroads: consumerproducts giant Unilever, which quietly began to sell goodsthrough a distributor in Myanmar late 2011. The company'sproducts were being smuggled in by third parties anyway,according to a spokesman, who said the company sells "soupand soap" in Myanmar via its Thailand operation and doesn'tmaintain an office in Myanmar. Another Western company withbusiness in Myanmar is U.S.-based Caterpillar Inc.According to the state newspaper New Light of Myanmar,government officials met in August with businessmenaffiliated with Caterpillar to discuss sales of engines andother heavy machinery. A company spokesman didn't confirmthe report but said, "Caterpillar and some foreignsubsidiaries may, under some circumstances, sell productsto independent dealers that resell to users in thiscountry. From 2012, Global conglomerate Coca Cola has setup shops in the country with the hopes of further expansionas reforms continue. This is only thre beginning of theimmense potential for the country to become a supply chainstoppage for leading MNCs.

7 Critical success factors

7.1 Sector wise investment mapping

7.1.1 Agriculture Myanmar has a total of 12.25 million hectares of arableland and permanent crops, the 25th-largest endowment in the

31 | P a g e

world despite the fact that Myanmar is only the 38th-largest country by total area. Although the country’sendowment of water and fertile land is abundant,productivity in Myanmar’s agriculture sector is low withoutput per worker of only around $1,300 a year, comparedwith around $2,500 per worker in Thailand and Indonesia.The sector’s low productivity and the low level of inputssuch as seeds, fertilizers, water, and machinery suggestthat there is significant room to grow. Here is also largescope to increase the share of fruits, vegetables, coffee,oil palm, rubber, and other high-value crops as well as theproduction of fisheries. Given that agriculture currentlyaccounts for 52 percent of workforce employment, capturingthe full growth potential of agriculture is critical toensuring that the economy’s growth is shared widely. (HeangChhor, 2013)

7.1.2 Energy and mining Myanmar has large endowments of oil, gas—its most importantexport—and precious minerals such as rubies, sapphires, andjade. For example, Myanmar currently ranks 46th in theworld in terms of proven gas reserves, and estimates ofundiscovered gas reserves indicate that the amount ofreserves is likely to be much higher. Myanmar produces 90percent of the world’s jade, which is valued highly inAsia. Many of these natural resource reserves are largelyunexplored today—with new technologies, the potential couldbe much higher than current estimates.

7.1.3 Manufacturing Myanmar’s labor costs today are comparatively low, givingthe country an opportunity to boost output in labor-intensive manufacturing sectors such as textiles, apparel,leather, furniture, and toys at a time when some of thismanufacturing is leaving China. However, labor productivityin the sector is also weak. Output per worker is only 70percent of that in Vietnam in 2010, 20 percent of that inChina and Thailand, and less than 15 percent of that inMalaysia. To compete in the region, Myanmar will need to

32 | P a g e

improve labor productivity. On the back of that higherproductivity, there is scope over time to make thetransition to more value-added sectors, following theexample of Thailand, Malaysia, and other Asian economies.

7.1.4 Infrastructure Myanmar’s infrastructure is not sufficient today to supportthe higher growth and future demand driven by developingindustrial sectors and an urbanizing population. Between2010 and 2030, our analysis suggests that Myanmar will needto invest $320 billion in its infrastructure if the economyis to achieve growth of 8 percent a year. The majority ofinfrastructure investment—60 percent—will need to be inresidential and commercial real estate, but there is also ahuge need for power plants, water-treatment plants, androad and rail networks.

7.2 ReformsMyanmar has moved with amazing speed to change itspolitical climate and configuration. Although the currentgovernment came to power in flawed elections, it hassurprised many observers with rapid moves to open updiscussion, make it possible for a real opposition toemerge, suspend work on a problematic dam project, andpursue peace with ethnic groups. The new parliament is alsoplaying an active role. However, these substantial changesin the political sphere have not yet been matched bycorresponding economic reforms. In part this is becauseevents have moved quickly and sanctions make it difficultto argue for more open policies when so much is prohibitedby richer nations. While the government has not been inpower very long, it is fair to wonder if the tentativeglasnost9 will be matched by perestroika.6 In the Russiancase, from which these two terms come, the tentative nature

9 Glasnost refers to the Russian experience under Gorbachev in which free discussion was allowed after years of repression. Perestroika, or restructuring, refers to the following economic reforms, which in Russia were tentative and then failed.

33 | P a g e

and ultimate failure of economic restructuring in the wakeof political opening saw resources handed over to cronycapitalists and then largely reacquired by the statesecurity apparatus. It has led to a political and economicorder in which democratic government and even honestelections are under threat.

7.2.1 Legal environment of business

Despite the passage of a new land law by the parliament,people in Myanmar are still being unfairly displaced bylarge business and agricultural projects without adequatecompensation or means of providing a livelihood. This islargely a legal matter, in which the law itself stillallows sizeable tracts of land to be seized. The lack ofaccess to a fair justice system leaves people with no meansof redress for displacement. In addition to legal remedies,new models must be found for ensuring that local residentsgain a fair share in large development projects and thatthey have stable land rights that cannot be arbitrarilyremoved by entrepreneurs who have special ties to thegovernment.

7.2.2 Exchange rate review

34 | P a g e

The Myanmar exchange rate has been the subject of extensivediscussion, and deservedly so. The nominal exchange ratemoved from about 1300 kyat to the dollar in 2007 to 800kyat to the dollar in 2011. During this period theinflation rate in Myanmar (over 10% a year) raised thecosts of production faster than in Myanmar’s neighbors andcustomers. As a result, the profitability of farming,fishing, and many industrial activities declined sharply.Income from these activities fell, leading to reportedmigration abroad. Normally, a country with a higherinflation ratethan itstradingpartners alsohas a currencythatdepreciates tokeep itsproductioncompetitive.Because ofrising naturalresourceexports,capitalinflows,remittances,and other factors, a flood of dollars and other foreigncurrencies has come into Myanmar, while import licensingand other taxes and restrictions have impeded imports. Theresult has been a nominal appreciation (increase in thevalue) of the Myanmar kyat of nearly 40% and a realappreciation (after adjusting for inflation differences) ofabout 50%. This movement in the exchange rate encouragesthe production of non-traded services, such asconstruction, and of goods with a high price to cost ratio,such as gems, jade, and natural gas. It depresses output of

35 | P a g e

rice, fish, pulses, and labor-intensive manufactured goods– goods from the sectors that employ an overwhelming shareof the population. Rice output per capita in 2011-12 islower than in 2009/10 or even in 2000/01 according to USDepartment of Agriculture estimates. Pulse and inland fishprices have fallen in kyat terms, destroying profitabilityin those sectors. If this exchange rate situationcontinues, the country’s dominant economic sectors willcontinue to contract or stagnate. Job growth and incomegeneration will be limited. This policy also hurts thepeace process, as peace agreements cannot endure unlessdemobilized soldiers find reasonable work. If there is one“quick win” for the government, it is adjusting theexchange rate so that farming and manufacturing regaintheir profitability.

7.2.3 Investment-Savings ratioMyanmar has historically invested 10% to 15% of GDP eachyear, although since 2007 this ratio has grown and it wasestimated at 22.7% of GDP in 2010. If depreciation is 10%of GDP (assuming that capital stock is double GDP and usinga depreciation rate of 5%, as in Indonesia), a 10%investment rate would just keep the total net capital stocklevel. A 12% investment to GDP rate would keep the percapita net capital stock level. Investment would have torise to 25% to 30% of GDP to make up for pastunderinvestment and to permit for rapid expansion ofeconomic activity.

The savings rate in Myanmar has been greater than theinvestment rate, since there has usually been a surplus ofexports over imports. However, some important detailscomplicate the picture. One is that unrecorded trade mayskew these results, though we would normally expect exportsand imports in informal trade to roughly cancel out.Second, the form of savings is important. The ratio of banksavings and checking deposits to GDP is only about 10% inMyanmar (one of the lowest ratios in Asia), meaning that a

36 | P a g e

high volume of savings may be in foreign currency, gold, orreal estate. Savings in these assets do not directly helppromote growth, since they are not easily mobilized fornon-property domestic investment. A third consideration isthat much of the investment comes either from FDI in thenatural resource sector and thus with limited linkages andemployment effects for the overall economy, or is directedby the government. Nonmarket investment, such as theconstruction of a new capital, will not have the samegrowth impact as investment aimed at production or directedat market-oriented infrastructure needed for production. Taking all of these considerations together, we welcome theincrease in investment and estimate that it could approachneeded levels if it continued to grow. However, unless thequality and composition of investment improves, simplyreaching a high level of investment may not have thedesired impact.

7.2.4 Banking systemMyanmar has four state and 19 private banks. Due tonationalization of the banking system during the socialistera from to 1962 to 1988, and the bank liquidity crisis,the CBM tightly regulated the sector. Private banks inparticular were limited in what they were permitted toengage in.It was only in November 2011 that the CBM beganliberalizing and awarded 11 private banks Authorized DealerLicenses that allowed them to engage in basic internationalbanking.Today, no foreign banks are allowed to operate inthe country, except to open a representative office.However, there are indications from the government that theexpected rules and regulations may provide foreign bankswith opportunities to participate through joint ventureformation with local banks before eventually being allowedto operate as subsidiaries, and then full branches.The opinion of many domestic bankers is that Myanmar banksand their staff need more time to improve before competing

37 | P a g e

with the foreign banks. They need to improve theirinfrastructure, increase their capital and undergo moretraining in international banking practices before beingcapable of competing with large international banks.Myanmar should follow the example of the other ASEANcountries that have restricted banking competition in orderfor local banks to develop and effectively compete.Myanmaris still very much a cash-based society. Only 20 percent ofthe estimated bankable population of 60 million has enteredthe formal banking system. The key for the future of thebanking sector is to bring these people into the bankingsystem. Development of the local banks is crucial for thegrowth of the banking sector in Myanmar.

7.3 Strategic policies

7.3.1 Alliance with neighborsIn the four months between March and July 2010, about $16billion of FDI were committed to Myanmar. This is as muchas the total FDI committed during the previous 22 years.This figure does not include the recently confirmed Daweideep-sea port project, which is estimated at $13 billion.Recent investments are mainly in oil and gas, electricityproduction and the mining sectors. China accounts for morethan 65pc of recent investments. Thailand ranks a distantsecond at 18pc. On the other hand, relations improve with India. In April2008, India and Myanmar signed the Double TaxationAvoidanceAgreementwhichenables thenations toprevent taxevasion and also ensure that business profits are taxedonly in the country where the company has a permanentestablishment. This was done to attract greater foreigndirect investment (FDI) between the countries. Out of

38 | P a g e

Myanmar's total trade of over $18 billion, India accountedfor only about 7.5 per cent in 2011-12 - falling short ofChina, Singapore, Thailand and Japan in terms of export toMyanmar. India-Myanmar bilateral trade expandedsignificantly from $12.4 million in 1980-81 to $1,070.88million in 2010-11. India's exports stand at $334.4million, while it imports goods worth over $1 billion fromMyanmar. The mainexports to Myanmar arepharma products, ironand steel, andelectrical machineryand equipment. Indiaimports large amountsof vegetables and woodfrom Myanmar. Thestrategically-locatedMyanmar, which sharesits boundary with China, Thailand, Laos, and Bangladesh,could well become India's gateway to the Association ofSoutheast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Having woken up to thisrealization, several Indian companies are lining up toenter the country and make their presence felt in everysegment of its economy.10 India's investment in Myanmarcurrently stands at around $273.5 million. It is expectedto soar to $2.6 billion over the next few years. Indiancompanies which now have presence in Myanmar include ONGCVidesh Limited (OVL), Jubilant Oil and Gas andCenturyPly.11

Bangladesh’s trade with Myanmar amounts to only US$6m whichis just 0.2% ofMyanmar’s total border trade with its

10 Looking east, companies finally spy Myanmar, Business Standard, August 03, 2013.

11 Indian companies, banks plan to invest in Myanmar, Economic Times, June 06, 2013

39 | P a g e

neighbors. Myanmar’s opening up to foreign directinvestment is both a huge challenge and an opportunity forBangladesh. As a competitor for FDI, Myanmar’s naturalresources give it an advantage, which can be seen forinstance, by Malaysian investors announcing a $500m deal tomanufacture Nissan cars there and Hong Kong and South Koreainjecting funds into its garment industry. Bangladesh alsoshares land border with the country. But illegal migrationof Rohinga people have had tensed the ties between the twocountries. There have been initiatives to connect the twowith a gas pipeline but bureaucratic discrepancies havestalled that prospect as well.

From this analysis of its relations with the neighbors, itbecomes increasingly clear that while some countries hangon to their sanctions, others have opted for an acceleratedeconomic engagement. This has the potential of being goodnews for the people of Myanmar, not only because prosperityis an important factor for social stability, but alsobecause people’s main aspiration remains an improvement oftheir everyday material life. Continuous political reformwhile also strengthening diplomatic ties with its neighborsshould be given highest priority at the moment.

7.3.2 Balanced trade diversification

40 | P a g e

Although the country has been enjoying a surplus for yearsnow, the export basket is too narrow to increase risks.While the import basket remains more diversified, theexport potential of the country in different sectors shouldbe thoroughly analyzed and taken advantage of. Otherwise,at the face of competition, this already poorlyinfrastructure country will not survive.

7.3.3 Special economic zoneOver the previous two years 6 SEZs have been proposed byvarious countries and investment corporations. Currentlyonly SEZs in Dawei, Thilawa, and Kyuakpyu are underdevelopment and each with unclear lead times to completion.It seems major stakeholders funding these SEZs look set tofirstly secure what they’re after before honoringdevelopments in full. Take Kyuakpyu SEZ for example.Predominantly funded through China National PetroleumCorporation, both oil and gas terminals along withpipelines back to China are nearly complete, yetinfrastructure for logistics and services industries neededfor Myanmar to begin processing natural resources moreindependently have fallen behind. China has long been theleading supporter for Myanmar’s development, but have theysimply been playing the global resources game and realizedahead of other securing such nowadays comes at a price?

41 | P a g e

More recently other potential players sitting on the sidelines have now picked up the tempo. Following Japan’swaiver of Myanmar’s 3.7 billion yen debt in April 2012,they have upped the ante with an additional $3.2 billion innew lending.The injection will support development of the 2,400 hectareThilawa SEZ and deep-sea port of Dawei SEZ. Plans aim tomature southern Myanmar as Southeast Asia’s largestindustrial complex, with Thilawa SEZ being host to textileand manufacturing industries. With the investments it hasbeen receiving, a reformed Myanmar should learn from itspast and bargain hard to ensure maturity of its SEZs. Onlythen an infrastructurally developed Myanmar would become apossibility and the economy will be able to fully utilizeits low wage benefit.

8 ConclusionOn the face of realistic analysis, the outlook remainstenuous. The lack of infrastructure, an inexperienced andincreasingly restless labor force, coupled with politicalwrangling may rattle what UN chief Ban Ki-moon called a“risky and fragile” reform process, thereby derailing thecountry’s attempts to return from economic exile. That mayor may not happen. But for the time being, at least,everyone sees the possibilities that could come from one ofthe greatest recent political transformations in South-EastAsia.

42 | P a g e

9 References

9.1 List of articles 1. http://www.cassindia.com/inner_page.php?

id=34&&task=diplomacy

2. http://www.business-standard.com/article/news-

ians/from-pariah-to-prime-time-myanmar-takes-up-

asean-chair-comment-special-to-ians-

113123100421_1.html

3. http://bigstory.ap.org/article/myanmar-once-pariah-

state-now-regional-leader

4. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-

12990563

5. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_Burma

6. http://www.livemint.com/Opinion/

NXpeyZDQzQAmaRVQcassRK/Myanmar-the-new-

centreoftheworld.html

9.2 List of research papers1. Kan Zaw (2008), ‘Challenges, Prospects and Strategies

for CLMV Development: The Case of Myanmar’, in

43 | P a g e

Sotharith, C. (ed.), Development Strategy for CLMV in the Age of Economic Integration, ERIA Research Project Report 2007-4, Chiba: IDE-JETRO, pp.443-496

2. Ferrarini (2013), ‘Myanmar’s trade and its potential’,ADB working paper series, No. 325

3. Dapice (2012), ‘Appraising the Post-Sanctions Prospects for Myanmar’s Economy: Choosing the Right Path’, Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University

4. International Monetary Fund, “Myanmar: Staff Report for the 2011 Article IV Consultation,” March 2, 2012, pg. 15

5. Michael F. Martin, “Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Sanctions,” Congressional Research Service, May 14, 2013, pg.9

44 | P a g e