Myanmar - International University of Japan

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Myanmar - International University of Japan

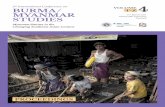

COUNTRY REPORT

Myanmar

4th quarter 1996

The Economist Intelligence Unit15 Regent Street, London SW1Y 4LRUnited Kingdom

The Economist Intelligence Unit

The Economist Intelligence Unit is a specialist publisher serving companies establishing and managingoperations across national borders. For over 40 years it has been a source of information on businessdevelopments, economic and political trends, government regulations and corporate practice worldwide.

The EIU delivers its information in four ways: through subscription products ranging from newslettersto annual reference works; through specific research reports, whether for general release or for particularclients; through electronic publishing; and by organising conferences and roundtables. The firm is amember of The Economist Group.

London New York Hong KongThe Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit15 Regent Street The Economist Building 25/F, Dah Sing Financial CentreLondon 111 West 57th Street 108 Gloucester RoadSW1Y 4LR New York Wanchai United Kingdom NY 10019, USA Hong KongTel: (44.171) 830 1000 Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 Tel: (852) 2802 7288Fax: (44.171) 499 9767 Fax: (1.212) 586 1181/2 Fax: (852) 2802 7638

Electronic deliveryEIU Electronic Publishing New York: Lou Celi or Lisa Hennessey Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 Fax: (1.212) 586 0248London: Moya Veitch Tel: (44.171) 830 1007 Fax: (44.171) 830 1023

This publication is available on the following electronic and other media:

Online databases CD-ROM Microfilm

FT Profile (UK) Knight-Ridder Information World Microfilms Publications (UK)Tel: (44.171) 825 8000 Inc (USA) Tel: (44.171) 266 2202

DIALOG (USA) SilverPlatter (USA)Tel: (1.415) 254 7000

LEXIS-NEXIS (USA)Tel: (1.800) 227 4908

M.A.I.D/Profound (UK)Tel: (44.171) 930 6900

Copyright© 1996 The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited. All rights reserved. Neither this publication nor any part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by anymeans, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited.

All information in this report is verified to the best of the author’s and the publisher’s ability. However,the EIU does not accept responsibility for any loss arising from reliance on it.

Symbols for tables“n/a” means not available; “–” means not applicable

Printed and distributed by Redhouse Press Ltd, Unit 151, Dartford Trade Park, Dartford, Kent DA1 1QB, UK

ISSN 1361-1445

Contents

3 Summary

4 Political structure

5 Economic structure

6 Outlook for 1997/98

9 Review9 The political scene

24 The economy and economic policy27 Tourism and transport29 Construction31 Energy and mining33 Foreign trade and payments

36 Quarterly indicators and trade data

List of tables8 Forecast summary

24 GDP growth by sector25 Paddy production25 Investment growth26 Prices of selected items30 State construction and renovation work33 Trade balance34 The current account34 Exports of main commodities35 Imports by category35 Imports of main commodities35 International liquidity36 Quarterly indicators of economic activity36 Trade with certain major trading partners

List of figures8 Gross domestic product8 Kyat real exchange rate

33 Merchandise trade balance35 Reserves

Myanmar 1

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

November 7, 1996 Summary

4th quarter 1996

Outlook for 1997-98: There is no clear end to the political impasse in sight.The slowdown in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors will constraingrowth. The success of Visit Myanmar Year is far from assured. Slower growthwill cool demand for imports. Inflationary pressures will remain, while the kyatmay come under further downwards pressure.

The political scene: The NLD’s attempt to call another congress promptedthe SLORC to step up its repression, including by stopping the weekend forumsoutside Aung San Suu Kyi’s house. The SLORC has accused the NLD of cons-piring with the US government to destabilise the country. A rare outbreak ofstudent protest was blamed on the NLD. The SLORC has been cultivating theBuddhist Sangha. The SLORC has issued a new law to control computer use.More members of ethnic minority groups have been fleeing to Thailand andBangladesh. There may be further delays in the process of drawing up a newconstitution. There have been divisions within ASEAN over how soonMyanmar should become a full member. The US sanctions bill has become law.The ILO has again charged Myanmar with breaching its conventions.

Economic policy and the economy: Weak agricultural and investmentgrowth may put this year’s GDP growth targets out of reach. Singapore nowheads the list of approved foreign investment projects. Inflationary pressuresremain strong. A petrol shortage has boosted prices, while concerns over theSLORC’s finances have prompted a run on the kyat.

Sectoral trends: The number of tourist arrivals has been increasing sharply,but Visit Myanmar Year has become a political battlefield. A port expansion isgetting under way. The SLORC marked the eighth anniversary of its seizure ofpower by inaugurating many construction projects. Commercial constructionis still booming. The statistics distort state infrastructure investment priorities.The oil companies involved in the Yadana pipeline are being sued in the USAbut work is about to get under way. Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprises hasdiscovered gas onshore and has signed five production-sharing contracts. Earn-ings from the latest gems sales were below target.

Foreign trade and payments: The trade deficit has widened sharply as aresult of both a collapse in export earnings and a surge in imports of bothcapital and consumer goods. Reserves have fallen sharply, due largely to thewidening trade deficit.

Editor:All queries:

Lucy ElkinTel: (44.171) 830 1007 Fax: (44.171) 830 1023

Myanmar 3

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

Political structure

Official name Union of Myanmar

Form of state Military council

The executive Since the military coup of September 1988, the State Law and Order RestorationCouncil (SLORC; last major reshuffle September 1992) has held all executive power

Head of state Chairman of the SLORC, Senior General Than Shwe

National legislature The Pyithu Hluttaw (People’s Assembly) was abolished after the military coup in 1988;an election was held for a new People’s Assembly in May 1990, resulting in anoverwhelming victory for the opposition National League for Democracy. The SLORCrefused to allow this assembly to meet

National elections May 27, 1990; next election date unknown

National government The SLORC controls all the organs of state power

Main political organisations Since the military coup political parties have been permitted to operate provided theyare officially registered. A number of organisations, mostly ethnically based, were inarmed conflict with the government for many years. In the past two years, most havereached an accommodation with the government

Main political parties National League for Democracy (NLD); Union Solidarity Development Association(USDA); National Unity Party (NUP); Democracy Party (DP); United NationalsDevelopment Party

Main members of the State Law and Order Restoration CouncilChairman & minister of defence Senior General Than ShweSecretary-1 Lieutenant-General Khin NyuntSecretary-2 Lieutenant-General Tin U

Deputy prime ministers Vice-Admiral Maung Maung KhinLieutenant-General Tin Tun

Key ministers Agriculture Lieutenant-General Myint AungBorder areas & minorities Lieutenant-General Maung ThintConstruction Major-General U Saw TunEducation Colonel Pe TheinEnergy U Khin Maung TheinFinance & revenue Brigadier-General Win TinForeign affairs U Ohn GyawHealth U Saw TunHeavy industry U Than ShweHome affairs Lieutenant-General Mya ThinnHotels & tourism Lieutenant-General Kyaw BaInformation Major-General Aye KyawLight industry Major-General Kyaw ThanNational planning & economic development Brigadier-General David Oliver AbelReligious affairs Lieutenant-General Myo NyuntTrade Lieutenant-General Tun KyiTransport Lieutenant-General Thein Win

Central Bank governor U Kyi Aye

4 Myanmar

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

Economic structure

Latest available figures

Economic indicators 1991 1992 1993 1994a 1995a

GDP at current pricesb Kt bn 186.8 249.4 360.3 473.1 613.2

Real GDP growthb % –0.6 9.7 6.0 7.5 9.8

Consumer price inflation % 32.3 21.9 31.8 24.1 25.2c

Population m 42.7 43.7 44.6 45.4 46.2

Exports fobb $ m 430.6 590.7 696.0 810 963.0

Imports fobb $ m 842.3 1,010.2 1,302.0 1,597.0 2,166.0

Current accountb $ m –344 –275 –292 –339 –630

Reserves excl goldd $ m 258.4 280.1 302.9 422.0 561.1c

Total external debtd $ m 4,853 5,327 5,730 6,502 n/a

Debt-service ratioe % 50.9 40.8 34.3 31.8 n/a

Exchange rate (av) Kt:$ 6.28 6.10 6.16 5.97 5.67

November 1, 1996 Kt5.98:$1

Origins of gross domestic product 1995c % of total Components of gross domestic product 1995c % of total

Agriculture 55.3 Total consumption 88.3

Livestock, fishing & forestry 6.8 Total investment 11.5

Manufacturing & mining 6.2 Increase in stocks 0.8

Transport & communications 2.8 Exports of goods & services 1.1

Construction & utilities 1.8 Imports of goods & services –1.8

Banking & finance 0.2 GDP at producer prices 100.0

Wholesale & retail trade 21.4

Other services 4.0

GDP 100.0

Principal exports 1994c $ m Principal imports 1993c $ m

Rice & rice products 197.1 Raw materials 297.5

Pulses & beans 133.3 Transport equipment 223.3

Teak 123.5 Foodstuffs 137.7

Rubber 20.5 Machinery & equipment 134.9

Total incl othersf 878.8 Construction materials 83.1

Total incl othersg 1,297.1

Main destinations of exports 1994c % of total Main origins of imports 1994c % of total

Singapore 16.3 Japan 23.6

India 12.9 Singapore 14.6

Thailand 10.0 China 12.2

North America 5.3 Thailand 10.0

China 5.1 Malaysia 9.4

Hong Kong 5.0 South Korea 4.7

Japan 4.8 EU 4.0

a EIU and official estimates. b Fiscal years beginning April 1. c Actual. d End-calendar years. e Based on debt-service payments due. f Fob customsdata. g Cif figures customs data.

Myanmar 5

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

Outlook for 1997-98

No end to the politicalimpasse is in sight

The continual stand-offs between the military junta, the State Law and OrderRestoration Council (SLORC), and the pro-democracy National League forDemocracy (NLD), cannot persist indefinitely. However, it is difficult to see howthe impasse can be broken. The SLORC refuses the NLD’s invitations to open adialogue, accusing the party of being in league with foreign powers. The NLD isboycotting the National Convention, the body charged with drawing up aconstitution, and which the SLORC has designated the only forum in whichdialogue may take place. The draft constitution heavily favours the military.

The SLORC is committed to holding another election once the constitution iscomplete. The last election, held in 1990, resulted in an overwhelming victoryfor the NLD, a result which the SLORC refused to recognise. The SLORC wishesto avoid a repeat of 1990. To do so, it must either crush the NLD or indefinitelyprolong the work of the National Convention. The SLORC has so far drawnback from the former. Since May, there has been an intermittent crackdown onthe NLD, but the SLORC has (so far at least) continually moderated the level ofrepression used. Since late September the SLORC’s brinkmanship has beensymbolised by the constant raising and lowering of barricades outside AungSan Suu Kyi’s house.

Either option—crushing the NLD or dragging out the National Convention—would undermine efforts to win the international acceptance Myanmar is nowseeking as part of its strategy for emulating the high-growth Asian economies.This more outward looking strategy has depended heavily on the support ofthe Association of South-east Asian Nations (ASEAN). However, Myanmar’sapplication to join ASEAN in 1997 now looks unlikely to be accepted. Thecountries opposing Myanmar’s speedy entry into the association includeThailand and Singapore. Myanmar’s immediate prospects of resolving its crisisof political legitimacy through ASEAN’s policy of constructive engagementnow look remote.

One scenario for breaking the present deadlock envisages the destruction of thesupposedly fragile unity of the military. This could come about through theremoval of the chairman of the SLORC, Senior General Than Shwe, who isrumoured to be in ill-health, or through the death of the former strongman, NeWin, who, some maintain, is still the real power in the land. Under thisscenario either event would set the two main factions in the military—ledrespectively by the intelligence chief, Lieutenant-General Khin Nyunt, and thearmy commander, General Maung Aye—against each other. However, there islittle evidence that any of the premises of this scenario are true. Divisionswithin the military may indeed intensify, but it is not clear that they willaccelerate the process of finding a political solution.

The economy will slowover the next two years—

During 1992/93-1995/96 GDP grew at an average annual rate of 8.2%. Weexpect the economy to slow over the next two years. The EIU uses official data;because of distortions in the data our forecasts should be taken as indicative ofgeneral trends. (A US Embassy report published in July showed that the officialGDP and trade data are distorted in a number of ways, even if the large extralegal

6 Myanmar

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

economy is excluded. The report estimated that adjusting for dual exchange ratesreduced average GDP growth in 1993/94-1994/95 from the official 6.8% to 4.6%.)

Myanmar’s recent rapid GDP growth does not look sustainable for a number ofreasons. For much of the 1990s Myanmar has been recovering from the eco-nomic collapse of the late 1980s (according to the World Bank, real GDP in1994/95 was just 10% above its 1985/86 level; while the population had grownby nearly 20%). Some reforms were introduced during the early 1990s, partic-ularly in the trade and agricultural sectors. However, the pace of liberalisationhas since slowed. Major reforms still need to be carried out in sectors such asthe rice export trade and the financial sector. Liberalisation efforts have back-tracked in some areas such as rice cultivation, while some pledges, such as toprivatisation, have not been followed through. However, the reforms will con-tinue to stimulate growth by attracting more funds out of the extensive extra-legal economy.

Overall growth has been driven by agriculture, the dominant sector in theeconomy, which recorded an exceptionally high annual average growth rate of8.8% in 1992/93-1995/96. This growth was achieved chiefly by increasing thearea devoted to rice cultivation, in particular by requiring farmers to plant asecond crop. The returns to this expansion may now be diminishing, while theintroduction of multicropping not supported by the appropriate technologymay be creating new problems, such as pest attacks. Early reports suggest thatthis year’s main rice crop may be lower than last year’s, which could make evenour forecast of agricultural growth of 4% in 1996/97 look overoptimistic.

While industry accounts for less than 10% of GDP, it is targeted to achieve ratesof growth of more than 13% per year over the next five years. This depends onrapid expansion of all components of the sector (manufacturing, mining, powerand construction). However, we expect industrial growth to decelerate in1996/97-1997/98. All of the industrial subsectors are heavily dependent on sus-tained inflows of foreign capital in the form of both foreign direct investment(FDI) and overseas development assistance. While FDI projects continue to beapproved, particularly in oil and gas, mining and property development, thelatest data suggest that realised investment in oil and gas and hotels has beenslowing. Pending hotel projects look vulnerable to cancellation, particularly ifVisit Myanmar Year (VMY), which begins on November 18, is not a success.Infrastructure constraints remain a problem; only China provides internationalassistance for infrastructure construction. Manufacturing growth will be damp-ened by the difficulty of securing import finance, while subcontracted garmentmanufacturing has been badly affected by the boycott movement in the USA.

Services growth has been boosted in recent years by growth in the financialsector and tourism. However, tourist arrivals during VMY are likely to be hithard by the boycott movement. The financial sector will lose much of itsdynamism in the absence of efforts to tackle problems such as negative realinterest rates and the general lack of confidence in the banking system(illustrated by the run on Myanma Mayflower Bank in July). The uneven dis-tribution of the fruits of growth has limited overall growth in domestic con-sumption, leading to a relatively weak performance of the domestic tradesector. However, imports of consumer goods are soaring.

Myanmar 7

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

—which will help bringthe trade deficit under

control

Although the external sector is still tiny, exports, particularly Myanmar’sresumption of rice exports, have played a positive role in boosting growth.However, exports remain dominated by primary commodities; with teak exportsno longer officially encouraged, and the nascent export-oriented garments ind-ustry hit by the decisions of US companies to cease sourcing in Myanmar,dependence on rice and pulses to generate foreign exchange is likely to grow.The sharp decline in foreign exchange reserves since May this year reflects thevulnerability of the trade account. However, we expect some improvement inthe trade balance next year on the assumption of higher rice prices, while theslower rate of industrial growth should subdue growth in imports.

Inflation will remain aproblem

Inflation will continue to be stoked by the large fiscal deficit, which is unlikelyto come under control even if the budgeted sharp fall in public investmenttakes place. Revenue has been falling as a percentage of GDP, and is likely tofall again in 1996/97 due to sluggish foreign trade (the main source of revenue).Inflationary expectations will continue to eat away at the free-market value ofthe kyat, hitherto supported by large inflows of foreign capital. The kyat isprobably still overvalued despite the runs on the local currency that have takenplace periodically this year.

Forecast summary(% changes year on year unless otherwise indicated)

1994/95a 1995/96b 1996/97c 1997/98c

GDP growth 7.5 9.8 5.5 4.8 of which: agricultured 5.9 10.5 4.0 3.5 industrye 10.6 15.0 9.0 8.0 servicesf 8.3 6.9 6.0 5.0

Consumer pricesg 24.1 25.2 29.0 27.5

Exports fob ($ m) 810 963 944 991

Imports fob ($ m) 1,547 2,166 2,425 2,546

Current-account balance ($ m) –339 –630 –950 –760

Average exchange rate (Kt:$)f 5.97 5.67 5.89 6.01

a Provisional actual. b Provisional. c EIU forecasts. d Includes agriculture, livestock, fisheries andforestry. e Includes mining, manufacturing, power and construction. f Includes trade and otherservices. g Calendar years (1994/95=1994).

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

1991/92 92/93 93/94 94/95 95/96(a)

Gross domestic product % change, year on year

(a) Estimate. (b) Nominal exchange rates adjusted forchanges in relative consumer prices.Sources: EIU; IMF, International Financial Statistics.

100

150

200

250

300

1990 91 92 93 94 95(a)

Kyat real exchange rate (b)1990=100

Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$Kt:$

Kt:¥

Kt:$

Kt:¥Kt:¥

Kt:DMKt:DMKt:DM

Kt:$

Kt:¥

Kt:$

Kt:¥Kt:¥

Kt:DMKt:DMKt:DM

Kt:$

Kt:¥

Kt:$

Kt:¥

Kt:$

Kt:¥

Kt:$

Kt:¥

Kt:$

Kt:¥

Kt:$

Kt:¥

Kt:$

Kt:¥

Kt:$

Kt:¥

Kt:$

Kt:¥

Kt:$

Kt:¥

Kt:DM

8 Myanmar

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

Review

The political scene

The SLORC steps up itscampaign to isolate the

NLD

Since late September the ruling junta, the State Law and Order RestorationCouncil (SLORC), has taken further steps to crush the National League forDemocracy (NLD) as an effective political force. The NLD won the 1990 elec-tions overwhelmingly, taking more than 80% of the seats, only to have theresults quashed by the SLORC. In May this year the NLD decided to hold aconference, the first since the release of the NLD leader, Aung San Suu Kyi,from house arrest in July 1995. Despite the arrest of some 200 of the NLD’ssurviving MPs, the May conference went ahead. However, since May theSLORC has mounted a more or less continuous campaign to cow the NLD andisolate its leadership from its support base (3rd quarter 1996, pages 5-6).

The most recent round of arrests of NLD members was sparked by two flash-points; first, the decision by the NLD to try to hold another All Burma PartyCongress on September 27-29, to coincide with the eighth anniversary of itsfounding (September 30), and second, student protests on October 21-23against the arrest and alleged police mistreatment of three of their colleagues.However, the scale of the crackdown has been constrained by the need to limitinternational criticism at a time when Yangon is hoping to gain admission tothe Association of South-east Asian Nations (ASEAN). Hence the SLORC haslargely relied on intimidation rather than more severe forms of repression.

NLD plans to hold acongress are thwarted—

The NLD’s decision to hold a second congress on September 27-29 to mark itseighth anniversary prompted a new wave of arrests of NLD MPs and others.During the night of September 26 the SLORC set up armed barricades to preventdelegates to the congress from gaining access to Aung San Suu Kyi’s house, and hertelephone was cut off. Attempts to hold the congress at the NLD party head-quarters were also thwarted, and in the end the congress could not go ahead.

Troops prevented foreign reporters from approaching Aung San Suu Kyi’shouse or taking photographs. At the beginning of August the SLORC hadbegun to hold regular monthly briefings for the foreign press in an attempt toearn some good will (3rd quarter 1996, page 10). However, on September 28the police detained several foreign photographers and television journalists intheir hotels and demanded that they hand over film of the checkpoints nearAung San Suu Kyi’s house.

—and the SLORC also putsa stop to the NLD’s

weekend forums

At the same time the junta took a step that it had hitherto avoided. By raising thebarricades outside Aung San Suu Kyi’s house it effectively banned the weekendforums at which Aung Sun Suu Kyi and other NLD leaders addressed audiences(numbering at their peak around 10,000) from over the fence of her Yangon home.Tapes of the speeches circulated throughout the country, and the forums hadbecome the NLD leadership’s strongest bond with its support base. The move tohalt the gatherings was not unexpected; the issue of Law No 5/96 in June, whichprovided a legal basis for banning the forums, suggested that the SLORC was onlywaiting for the opportune moment to step in (2nd quarter 1996, pages 6-7).

Myanmar 9

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

A month in Myanmar politics

September 26: The opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) prepares to holda party congress on September 27-29 at the house of Aung San Suu Kyi on UniversityAvenue. Troops set up armed barricades on the street outside to prevent delegatesattending. Around the same time Aung San Suu Kyi’s telephone is again cut off.September 27: About 300 people gather at an alternative venue, the NLD offices, tobe told that the offices have been closed because the lease has expired. Arrests ofdelegates and others “in the interests of stability” begin.October 1: The SLORC Information Committee holds its monthly press briefing atwhich it presents its reasons for the latest crackdown.October 2: Aung San Suu Kyi holds a press conference with foreign journalists. Sheclaims that around 800 of her supporters have been arrested since September 27.October 8: The barricades outside Aung San Suu Kyi’s house are removed. Aung SanSuu Kyi announces that the NLD’s weekend forums outside her house will resume,while a meeting of NLD officials will also be held there to discuss the recent crackdown.October 11: The barricades are re-erected to prevent access to Aung San Suu Kyi’shouse as the weekend approaches.October 12: The police arrest people gathering in University Avenue for the weekendforum.October 20: An altercation in a restaurant in Insein Township leads to the arrest andalleged mistreatment of three students from Yangon Institute of Technology. Thebarricades outside Aung San Suu Kyi’s house come down again. October 21: Students hold a short demonstration in Insein Township demanding anapology from the police. In the absence of an apology a large group of studentsmarches to the main Yangon University campus in central Yangon. The barricadesoutside Aung San Suu Kyi’s house are put up again. October 22-23: Two student leaders meet the NLD deputy chairman, U Kyi Maung.Around 500 students stage a sit-in.October 23: A three-hour demonstration in central Yangon involving up to 1,000students disperses peacefully. U Kyi Maung is arrested. Aung San Suu Kyi is preventedfrom leaving her home. October 28: U Kyi Maung is released. The barricades are lifted again.

The SLORC blames thecrackdown on a foreign

plot—

In a move portrayed in the official media as marking a new openness, theSLORC Information Committee has been holding regular briefings for foreigncorrespondents since August (3rd quarter 1996, page 10). The crackdown of lateSeptember was the main topic at the SLORC’s monthly press conference inOctober. The head of strategic studies at the Ministry of Defence, Colonel KyawThein, gave some details about the crackdown.

The SLORC accused the NLD of intending to adopt resolutions aimed at“undermining the stability of the state”, maintaining that it had evidence thatthe NLD had called its congress as part of a foreign-inspired plot to destabilisethe country. To back this up, the SLORC cited the timing of the plannedmeeting, which coincided with significant events abroad; specifically, approvalby the US president, Bill Clinton, of the bill imposing limited sanctions onMyanmar, the annual meeting of the UN General Assembly and ASEAN’s con-sideration of Myanmar’s recently submitted application for membership.

10 Myanmar

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

The colonel told the press that a total of 159 NLD delegates—136 from Yangon,23 from the districts—had been picked up for questioning and “accommodatedin guest houses”, a standard SLORC euphemism for detention (it has beenconfirmed that several of those held were in fact taken to Insein Prison, anda higher figure was later given for the number detained). The closure onSeptember 28 of the NLD offices on Shwegondaing Road was due to the fact thatthe lease had expired and the owner had decided to repossess it.

According to Colonel Kyaw Thein, holding the congress “was clearly plannedto put the government in a tight spot domestically and internationally”. Thecolonel claimed international organisations were funding the NLD. Organis-ations named were the Soros Foundation, the International Republican Insti-tute, the Burmese Border Consortium and the Albert Einstein Institute. Theneed for opposition parties was rejected, but at the same time the colonel saidthat it would be misleading to suggest, as the NLD did, that the SLORC doesnot desire democracy. The SLORC was described as a transitional government,“supervising a political transition directed towards multi-party democracy”.

—masterminded by theUSA—

The USA’s support of the NLD has come in for particular criticism. The director-general of the political department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, KhinMaung Win, recounted that the US chargé d’affaires, Marilyn Meyers, hadcome to see him on September 24 and had said that if any action was takenagainst the NLD or the meeting it would have “negative implications”. ColonelKyaw Thein claimed that diplomats had visited Aung San Suu Kyi “about 137times” since her release from house arrest.

Efforts were made to disseminate details of the alleged plot. A TV Myanmarbroadcast on September 27 itemised 14 meetings between Aung San Suu Kyi andMs Meyers between early August and September 26 and concluded: “It is quiteobvious that the NLD has coordinated this movement in collaboration with someforeign countries”. A senior official quoted by Reuters charged the US embassywith coordinating with the NLD to organise the meeting to coincide with discus-sions of the Cohen amendment in Congress. (The Cohen-Feinstein amendmentgives guidelines for the imposition of US sanctions on Myanmar.) TV Myanmarreported on September 29 that during August Aung San Suu Kyi met with reporterson 52 occasions, during which she allegedly “made false news reports”.

—and incitement by theNLD

The SLORC also charged the NLD with breaking the law in trying to hold theSeptember congress. It cited regulations issued in August 1989 requiring polit-ical parties wishing to organise public assemblies and to use loudspeakers toseek permission from the township administrative authorities and the police. Itclaimed that before Aung San Suu Kyi’s release the NLD had followed theserules. There were also accusations of incitement, against Aung San Suu Kyi inparticular. According to a state radio report on the ban on the weekend forums,“lately Aung San Suu Kyi has increased her instigations by telling the peopleattending the roadside talk shows to be courageous, not to be afraid of thegovernment and to oppose the government”. The arrest on October 23 of theNLD deputy chairman, U Kyi Maung (see below), the first of the top three NLDto be rearrested since their release in 1995, was justified on the grounds that hehad incited the student demonstration held that day.

Myanmar 11

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

The SLORC seeks to drive awedge between the NLD

leadership

By highlighting the supposed contrast between the NLD’s stance before andafter Aung San Suu Kyi’s release, the SLORC seemed once again to be trying toexploit putative divisions within the party (2nd quarter 1996, page 9). OneSLORC statement issued after the latest round of arrests explicitly made this point,contrasting the “gentle” approach of the NLD chairman, U Aung Shwe, with the“desire always to oppose” of the trio comprising party secretary-general, Aung SanSuu Kyi, and the two deputy chairmen, U Tin Oo and U Kyi Maung.

Aung San Suu Kyi isdetermined to hold a

congress

Aung San Suu Kyi slipped through the barricades on October 2 to hold her ownpress conference with foreign reporters. She claimed that up to 800 people hadbeen detained, in contrast to the much lower figure cited by the SLORC. Shetold the foreign press that the SLORC’s “stupid behaviour” had, by alienatingdomestic and international opinion, been “a great help”. Aung San Suu Kyialso stated she was still determined to hold a congress, indicating that the NLDleadership reserved the right to do so without permission from the authorities.

The crackdown has takenits toll on the NLD

Aung San Suu Kyi has denied that the SLORC’s campaign of intimidationagainst her supporters is working. Not surprisingly, however, the new wave ofarrests (followed by lengthy jail sentences in some cases) has had a chillingeffect. Before they were stopped entirely on the weekend of September 28-29,attendance at the weekend forums had been dwindling, falling to around1,500-2,000; at their height the gatherings had numbered some 10,000 sup-porters. Those attending the forums have been targeted in the recent crack-down. For example, on September 22 the state-owned New Light of Myanmarconfirmed the arrest of nine youths for distributing pamphlets at the weekendrallies. Among those arrested were also some of Aung San Suu Kyi’s importantaides, including her personal assistant, Win Htein (whose sentence has re-cently been doubled to 14 years, according to the NLD). In addition, the ranksof NLD MPs have been depleted by resignations, following the trend that beganin the aftermath of the crackdown after the May congress (3rd quarter 1996,page 7). The junta has claimed that ordinary NLD members in the provinceshave been resigning en masse.

The SLORC moderates thelevel of repression—

The level of repression used by the SLORC in the current crackdown has beenrelatively constrained (3rd quarter 1996, page 5). Most of those detained werereleased after just a few days. On October 2 it was announced on TV Myanmarthat 88 of the 159 NLD members “temporarily housed at guest houses” hadbeen released. It was also announced that another 414 people had been ar-rested on September 28-29 “in the interests of stability and the rule of law”, ofwhom 75 had been released. By October 7 the SLORC was announcing thatonly 63 remained in detention and that they too would be released soon.

—but steps up the threatsagainst the NLD leadership

However, the SLORC has stepped up its threats against the NLD leadership. Theofficial press recently went beyond the highly personal denunciations of AungSan Suu Kyi and the ritualistic threats to “annihilate” her. A commentary in theNew Light of Myanmar on September 25, two days before the NLD congress wasdue to begin, predicted that Aung San Suu Kyi would be charged as a “politicalcriminal” in the “not too distant future”. The following day the New Light ofMyanmar mentioned the NLD’s plans to hold an anniversary congress and

12 Myanmar

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

accused the party of “heading towards a one-party democracy dictatorialsystem”, speaking of “power-crazy internal traitors under the influence of out-side powers”.

Following the student demonstrations of October 21-23, U Kyi Maung wasdetained and Aung San Suu Kyi placed under de facto house arrest, althoughonly for five days. In the interim between the events of September 26-28 andOctober 20-23 the SLORC played a cat and mouse game, removing and thenre-erecting the barricades outside Aung San Suu Kyi’s home in order to preventher going ahead with the weekly forums. During this period Aung San Suu Kyiwas able to come and go to meet party leaders, although subject to heavysurveillance. By October 31 the SLORC again seemed to be making more con-ciliatory moves. Aung San Suu Kyi met with her former liaison officer, Lieuten-ant-Colonel Than Tun, for the first time in almost one year. It was suggestedthat this modest effort at contact was a reward to Aung San Suu Kyi for agreeingto stay off the streets during the student protests. However, it was not clear thatthe move was the start of a more meaningful dialogue.

A rare outbreak ofstudent protest—

The immediate spark that set off the student protests of October 21-23 was ascuffle between three students of the Yangon Institute of Technology (YIT) andthe owners of a restaurant in Insein township (some 13 km from centralYangon). Local police arrested the three, who claimed that they were beatenwhile in custody. Over the following three days progressively larger studentdemonstrations took place in Insein and then in central Yangon near the mainYangon University, about 2 km from Aung San Suu Kyi’s house.

—alarms the SLORC— These events will have seemed ominous to the SLORC. The spark that led to thecountrywide uprising in 1988 and its brutal suppression was also an altercationinvolving students and a teashop owner. The SLORC must have feared thatafter a long period of quiescence the students were once again about to set offwider protests. In early October, in a typical expression of official fears, theintelligence chief and so-called secretary-1 of the SLORC, Lieutenant-GeneralKhin Nyunt, told a group of teachers that “destructive elements” were usingstudents as “scapegoats” in destroying the stability of the country. He urgedteachers to organise youngsters under the leadership of the government’s polit-ical vehicle, the Union Solidarity Development Association (USDA).

Unlike in 1988 the government response to the October student protest wascautious. The junta appointed the deputy minister of education and the railminister to talk with the students, preferring to criticise the NLD rather thanrisk a wider confrontation with the students. Nonetheless, after the demonstr-ations had died down, troops were deployed around the city’s colleges. OnOctober 25 Yangon Institute of Technology students from the provinces weresent home, high-school pupils in Yangon were reported to have been senthome early and schools in Mandalay were closed.

—and is blamed on theNLD—

On October 22 the government accused the NLD, and specifically, U KyiMaung, of colluding with the students. (U Kyi Maung was imprisoned in 1990and sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment. He and his fellow deputy chairman,U Tin Oo, were released in 1995.) Aung San Suu Kyi was prevented from leaving

Myanmar 13

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

her home for a number of days from the morning of October 23, around thesame time as Kyi Maung was arrested. On October 28 U Kyi Maung was releasedafter five days in detention, and the barricades blocking access to Aung San SuuKyi’s house were again lifted. However, several members of the NLD youthwing have reportedly remained in detention in connection with the demon-strations.

—despite denials from thestudents and the party

The SLORC insisted that the incident at the restaurant had been “forged anddiverted to political ends”—an accusation vigorously denied by both the stu-dents and the NLD. The students insisted that their demonstrations had beenaimed simply at protesting both the brutality with which the police had treatedtheir colleagues and also the inaccuracy of the official reports of the incident.The NLD, too, was quick to disassociate itself from the student actions, stress-ing that its first concern was to maintain “peace and tranquillity”. U Tin Ootold the US-based newspaper Christian Science Monitor that “violence and dis-turbances won’t solve our problems”.

While it is not clear exactly what happened at the restaurant, versions of theevent soon spread which suggested that the scuffle may have had a politicalaspect. According to one student account, the three students were beaten bymembers of the auxiliary police, whose actions in the first instance were di-rected against the restaurant owner. Another version had it that the restaurantwhere the scuffle took place is owned by the Military Intelligence.

The SLORC is wary of themonkhood—

The SLORC is also haunted by fears of an alliance between Buddhist monks andthe NLD. Since the 1970s the obedience of the Sangha (the Buddhist monk-hood) to the state has been ensured by a mixture of repression and cooption.The 1974 constitution drawn up by General Ne Win’s military regime retainedthe highly contentious 1961 amendment to the constitution which had madeBuddhism the state religion. Hence the state has taken on the role of guardianand patron of the faith, much as the Burmese kings had traditionally donethrough their religious councils.

However, the SLORC remains wary of the Sangha. In late September GeneralMyo Nyunt, the minister of religious affairs, called a conference in Yangon ofmembers of the Yangon Township Monks Committees, the Yangon Districtand Divisional Monks Committee and the Central Monks Committee. Thevice-chairman of the Central Monks Committee told the conference thatmonks should stay away from politics. He added that the state was now stable,and the government was making large donations to religious institutions.General Myo Nyunt said that the principles laid down by the NationalConvention upheld the separation of religion and politics enunciated by thehero of independence (and Aung San Suu Kyi’s father), Aung San.

—and warns of NLDinfiltration

At the same time the general accused the NLD of trying to infiltrate the monk-hood. He said that laws had been passed to prevent the ordination of NLDmembers. The SLORC clearly continues to regard Myanmar’s 300,000 Buddhistmonks as a potential catalyst for wider unrest in the same way that it is worriedby any sign of student opposition. This fear has some basis in reality. InSeptember 1990, as it became clear that the SLORC would not honour the

14 Myanmar

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

results of the July election, Buddhist monks took to the streets in Mandalay andother northern towns and refused to perform religious rites for members of themilitary and their families. As the protests spread, the military cracked down. Areported 350 monasteries were raided, hundreds of monks were detained andthe Sangha leadership was purged. Around 200 monks are believed to be stillserving sentences in Insein prison. As recently as May a monk was sentenced toseven years imprisonment for putting up posters calling for dialogue betweenthe junta and its opponents.

The new constitution maybe further delayed

After a brief spurt of activity earlier this year the National Convention, thebody that has been engaged in drawing up a constitution since January 1993,has again gone quiet. The convention did not resume in October as planned(3rd quarter 1996, page 9). The chapters drafted to date heavily favour themilitary, which is guaranteed roles in the executive, the legislature and thejudiciary. In contrast, Aung San Suu Kyi is barred from heading a governmentby clauses relating to her marriage to a foreigner and her long absence from thecountry.

The SLORC is not keen to see the constitution completed, presumably becausecompletion should be followed by elections. However, this reluctance posessomething of a dilemma for the SLORC. The promise of a democratic consti-tution is their sop to international opinion, while the SLORC has also por-trayed the National Convention as the only proper forum for the “dialogue”that both the junta and the opposition claim to want.

The NLD walked out of the National Convention one year ago, saying that therewas no possibility of dialogue in a convention run by the SLORC. Despite this,the SLORC has blamed the NLD for delays in drafting the new constitution. Inhis speech to the Union Solidarity and Development Association (USDA) annualmeeting on September 12, the SLORC’s chairman, Senior General Than Shwe,said that attempts to delay the passage of the constitution would only “prolongthe status quo”. The same sentiment was expressed by the SLORC’s vice chair-man, General Maung Aye, who is also commander-in-chief of the army, in aspeech to newly graduated army officers on September 23. The general warnedthat if “certain stooges” continued to obstruct the work of the National Conven-tion, “the present form of administration could be prolonged and stay on”.

The USDA celebratesanother anniversary

The founding of the NLD is not the only anniversary to have been markedrecently. September 18, the eighth anniversary of the SLORC’s coming topower, was celebrated mainly through the inauguration of a variety ofconstruction projects (see Construction). The junta’s political vehicle, theUnion Solidarity and Development Association (USDA) celebrated its thirdanniversary on September 15. At the USDA annual meeting held three daysearlier, delegates recounted the association’s success in organising mass ralliesacross the country in support of the National Convention, condemning “ene-mies of the country”. The USDA claims a membership of 4.6 million, compris-ing mainly students, government employees and youths belonging to theMyanmar Red Cross and auxiliary fire brigades.

The USDA has regularly been accused of disrupting opposition activities(2nd quarter 1996, page 10). Aung San Suu Kyi described how she saw a crowd

Myanmar 15

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

of USDA members gathered in the public garden at the top of the street, on themorning of September 27, ahead of the aborted NLD congress. Similar state-ments have been made before. On Burmese New Year’s Day in April, when theNLD leadership had planned to make an offering at the Shwedagon Pagoda(2nd quarter 1996, page 8), Aung San Suu Kyi’s street was emptied except forsecurity personnel and members of the USDA. Thanks to the SLORC, the USDAhas also been acquiring economic muscle, including the control of some re-gional bus companies.

The SLORC is striving tocontrol information flows

On September 20 the SLORC passed the Computer Science Development Law,regulating computer equipment and its use. Internal modems, fax modems andcomputers with networking capability are the main targets of the new law.Licences will be required from the Ministry of Communications, Posts andTelegraphs for certain types of equipment (as yet unspecified). Under the guid-ance of a Myanmar Computer Science Development Council (to be estab-lished) the Ministry of Communications, Posts and Telegraphs will decidewhich types of equipment are to be restricted.

Those found in unauthorised possession of restricted equipment will be liableto prison terms of 7 to 15 years. Similar penalties face persons obtaining orsending by computer information on state security, the economy or nationalculture. Persons importing or exporting computer software banned by thecouncil are liable to sentences of 5 to 10 years. To prevent unauthorised use,computer users (termed “enthusiasts”), scientists and traders are to be organ-ised into associations. Members of an unauthorised computer association mayreceive a three-year sentence. The law stipulates that computers used only asaids in teaching, office work or business will not need to be licensed. Thedistinction may not be that easy to make in practice; in June the businessmanand honorary consul, Leander Nichols, died in prison after being sentenced oncharges of unauthorised use of a fax machine (3rd quarter 1996, page 6).

Refugees flee relocationpolicies and continued

fighting

There have continued to be reports of hardship resulting from the relocationpolicy in the ethnic minority areas of eastern Myanmar. These policies appearto have been employed against the Shan, the Karen, the Karennis and theMons among others. Since March more than 80,000 villagers have been forcedto relocate in central and southern Shan state. The objective of the relocationsis to prevent villagers from helping Shan rebel groups still fighting after thesurrender in January this year of their one-time leader Khun Sa and the bulk ofhis Mong Tai Army (MTA) (2nd quarter 1996, pages 12-13).

Foreign diplomats and journalists have been refused permission to visit areas ofShan State where the relocations are taking place, but reports based on inter-views in Thailand indicate that people who are relocated receive minimal foodand shelter. At least 20,000 Shan are believed to have fled to Thailand sinceMarch. The pattern in Kayah State is very similar. Local inhabitants have beenforcibly relocated, and sporadic fighting between the rebels of the KarenniNational Progress Party (KNPP) and the Myanmar military has been reporteddespite the ceasefire agreed in June 1995.

This situation has seen increasing numbers of refugees stream over the borderinto Thailand. There are now estimated to be some 95,000 ethnic minority

16 Myanmar

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

refugees (mainly Shan, Karen, Karenni and Mon) living on the Thai side of theThai-Myanmar border. The situation seems to be getting worse. Two years ago,before the most recent round of ceasefires, the number of refugees was esti-mated at around 70,000. The UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) canplay only a limited role in Thailand because the Thais have not signed theinternational conventions on refugees.

Another Rohingya exodusgets under way

The UNHCR does operate in Bangladesh, where it has been involved in theresettlement and repatriation of the estimated 250,000 Rohingyas (the Muslimminority of Myanmar) who fled Arakan State in 1991-92. The UNHCR hasoverseen the repatriation of all but about 50,000 of these Rohingya refugees.However, this year has seen a new influx of Rohingyas into Bangladesh. Ac-cording to UNHCR estimates, between March and June 5,500 Rohingyas fledArakan. Other relief agencies put the figure as high as 10,000.

According to the Rohingyas, this new exodus was also caused by a desire toescape forced labour in Myanmar. However, both the UNHCR and theBangladeshi authorities argue that the immigrants are fleeing poverty, notpersecution. A cyclone in Arakan last November cut rice output by 20%, andYangon refused to modify its rice procurement policies to ease the plight offarmers. The UNHCR acknowledges that there is forced labour in Arakan butargues that the practice does not in itself amount to persecution since it isprevalent throughout Myanmar.

The SLORC is to holdfurther talks with Karen

rebels

Karen refugees in Thailand continue to be harassed by members of theDemocratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA), a pro-SLORC group that broke awayfrom the main Karen rebel group, the Karen National Union (KNU), in 1994.The KNU is the only one of the main ethnic insurgent groups not to havesigned a ceasefire with the SLORC. In mid-November the KNU is due to haveits fourth round of ceasefire talks with the military. However, from mid-Octo-ber, with the dry season approaching, there were reports of sporadic clashes,and of a build-up of government troops in Karen areas near the Thai border.More Karens were reported to be fleeing over the border into Thailand.

The ABSDF holds a unitycongress

The main student guerrilla group, the All Burma Students Democratic Front(ABSDF), held a congress in September which apparently managed to reconcilethe two factions into which the front split five years ago. Composed of studentswho fled into the jungle after the killing of thousands on the streets of Yangonin August 1988, the front’s membership has fallen from around 10,000 then toa claimed 2,200 now. The students met at Teakaplaw, the headquarters of theleader of the rebel Karen National Union (KNU), General Bo Mya. The ABSDFand the KNU have collaborated closely since the late 1980s.

ASEAN divides overadmitting Myanmar

The question of Myanmar’s admittance to the Association of South-east AsianNations (ASEAN) has severely strained the group’s much-prized “spirit of con-sensus.” The recent developments in Myanmar have caused some withinASEAN to question its longstanding policy of constructive engagement withthe SLORC. (ASEAN has seven members—Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines,Singapore, Thailand, Brunei and Vietnam—and three candidate members withobserver status—Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar.)

Myanmar 17

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

The main area of contention is how soon Myanmar should be admitted as amember. Yangon submitted its application for full membership in August.During his visit to Malaysia in August Senior General Than Shwe was assuredby the Malaysian prime minister, Dr Mahathir Mohamad, that Myanmar couldexpect to become a full member in 1997. An informal summit of ASEAN leadersis scheduled for late November in Jakarta, at which the final decision will betaken. (Yangon will itself attend the meeting as an observer.)

ASEAN diplomacy

September 27: ASEAN foreign ministers meet in New York. Statements issued bymember governments after the meeting are unclear on whether the association hasdecided to defer Myanmar’s admission to full membership beyond 1997.October 3: The president of the Philippines, Fidel Ramos, says it might be necessaryto review the ASEAN policy of constructive engagement, including the policy of notdirectly challenging Myanmar on its human rights record.October 3-4: At a meeting of the ASEAN Standing Committee the Philippines for-mally raises the possibility of seeking a review of the policy of constructive engagementOctober 4: The Philippine foreign secretary, Domingo Siazon, says that the proposedpace of Myanmar’s integration into ASEAN is too fast. A Thai foreign ministry officialsays that in making a decision on membership, his government cannot overlook thesituation in Myanmar.October 5: Dr Mahathir, prime minister of Malaysia (which is ASEAN’s chairman in1997), says that he believes that it is unnecessary to review the policy of constructiveengagement for which he claims a number of successes. October 6-7: President Suharto of Indonesia visits Malaysia. Both countries reasserttheir commitment to constructive engagement. At the same time statements fromboth countries’ foreign ministers suggest they may be preparing for the postponementof Myanmar’s admission to membership.October 8: Thailand’s caretaker prime minister, Banharn Silpa-archa, tells hisNorwegian counterpart, Gro Harlem Brundtland, that he thinks Laos and Cambodiashould become members of ASEAN before Myanmar.October 9: An editorial in the Singapore Straits Times warns that unless the SLORCshows progress in its “constitutional manoeuvres”, ASEAN will “feel under increasingpressure” to reassess its policy.October 17: Mr Ramos says that as a closed economy under a military regimeMyanmar is precluded from ASEAN membership.October 18: Senior ASEAN officials meet in Kuala Lumpur. The Philippines andThailand seem more circumspect about pressing for delayed admission. Malaysia sup-ports as soon as possible.October 20: The Malaysian foreign minister, Abdullah Badawi, on a visit to Yangon,says that ASEAN membership would help Myanmar’s economy grow and thus speeddemocratisation.October 24: On the day after the arrest of the NLD’s U Kyi Maung, the Thai foreignminister, Kasem Kasemsri, says that Myanmar is not ready for membership.October 26: The prime minister of Singapore, Goh Chok Tong, says that Myanmar isnot yet ready to meet the obligations of ASEAN membership.

Thai and Philippineobjections—

The unusually public airing of differences within ASEAN started at an informalmeeting of ASEAN foreign ministers in New York on September 27. There wasconfusion over whether the association had decided to delay Myanmar’s

18 Myanmar

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

admission (as Thai sources claimed), or had decided to delay its decision on thematter (Singapore) or had not changed course at all (Indonesia). Soon afterboth Malaysia and Indonesia, Myanmar’s staunchest supporters, began to talkof the possibility of technical obstacles to Yangon’s early admission.

The strongest objections, however, came from the Philippines and Thailand. Anumber of Philippine officials, including the president, Fidel Ramos, have madea series of statements arguing for a delay on explicitly political grounds. TheThais also began to show signs of disillusionment with constructive engagementafter two high-level visits (by the prime minister and the foreign minister) toYangon earlier this year had produced meagre results (2nd quarter 1996,page 12; 3rd quarter 1996, pages 15-16). No longer protected by the buffer ofethnic insurgent armies, Thailand is finding the SLORC an awkward neighbour.The upcoming visit to Bangkok by Mr Clinton in November, which will involvehard talks on US-Thai trade relations, will also have influenced Thai thinking.

—find an echo inSingapore—

More muted, but also more surprising, was Singapore’s opposition to earlyentry. Singapore is Myanmar’s leading investor and most important destina-tion for (legal) exports, and has been one of the SLORC’s leading apologists (1stquarter 1996, pages 16-17; 3rd quarter 1996, page 13). An editorial in theSingapore Straits Times on October 9 was the clearest indication that a changeof heart might be coming. The editorial, in a newspaper generally assumed toreflect government policy, warned of a possible reassessment of the policy ofconstructive engagement “to say nothing of deferring membership for Myan-mar”. It said that the SLORC would, among other things, have to bring theNLD back into the constitutional process.

Official confirmation emerged more slowly. At the meeting of senior ASEANofficials in Kuala Lumpur on October 18, Singapore said only that it would goalong with the consensus view. However, in an interview with MTV3 Finlandin late October, Singapore’s prime minister, Goh Chok Tong, said that he didnot think that Myanmar was “quite ready in the near future” to adopt all theobligations of membership. He added that of the three candidates for member-ship (which include Laos and Cambodia), Myanmar might be last to join.

—marking an importantshift

It is not clear what prompted this important change of direction. U Kyi Maungsuggested economic reasons. He claimed that Singapore was motivated by anxi-ety that Visit Myanmar Year (which begins on November 1) will be a flop,leaving the high-class new hotels, in which Singapore has invested heavily, nearempty (see Tourism). There have been other indications that Singaporean busi-ness people have been becoming disillusioned with Myanmar’s investment cli-mate, as their projects become mired in red tape, corruption and massive costoverruns (see Tourism). A more important factor may have been Singapore’sconcern that its pivotal role in fostering the development of the two supra-regional groupings, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum andthe Asia-Europe Meetings (ASEM), might be undermined by differences overMyanmar. Such differences could also sour the next meeting of the World TradeOrganization (WTO), which Singapore is due to host in December.

Myanmar 19

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

Postponement ofMyanmar’s entry into

ASEAN is now likely

The Philippines and Thailand clearly have some reservations about Myanmar’sspeedy entry into ASEAN. However, the association seems willing to allowYangon the pretext of “technical difficulties” for delaying its membership. It istrue that Myanmar’s rapid transition from observer status this year to plannedfull membership in 1997 would have been unprecedented. The two other coun-tries which are expected to join the association next year—Laos and Cambo-dia—have been observers since 1992 and 1995 respectively. However, it is notclear what other technical obstacles might impede Myanmar’s membership.Unlike the most recently admitted ASEAN member, Vietnam, Myanmar has theadvantage of having a large corps of English-speaking civil servants, while as amember of the WTO it is already legally bound to liberalise its trade regime.

The other technical criteria for membership are that the country in questionhas observer status, accedes to the basic agreements and declarations of theassociation, meets various financial obligations, has an embassy in the capitalsof every other member country, and establishes a national ASEAN secretariatoffice and a unit to oversee ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) obligations.

These requirements should not pose undue problems to Myanmar. Myanmargained observer status in July, and has embassies in all the member countriesexcept Brunei, where one is being established. Myanmar is reported to bepreparing to open a national ASEAN secretariat in November. The governmentrecently approved the opening of an ASEAN division in the political depart-ment of the foreign ministry.

Thailand’s position couldhinge on elections

The Thai stance on Myanmar could be altered by the outcome of parliamentaryelections scheduled for November 17. One of the two key contenders forpower, the leader of the National Aspiration Party (NAP), General ChavalitYongchaiyudh, has been heavily involved in negotiations with the SLORC andmay favour continued constructive engagement. The recently appointed Thaiarmy commander, General Chetta Thanajaro, is a protégé of GeneralChavalit’s. During the talks last year that led to the first visit to Yangon by aThai prime minister for 16 years, General Chetta reportedly formed close tieswith Myanmar’s top military commanders (2nd quarter 1996, pages 10-11).General Chetta is also reported to be planning an unofficial goodwill visit toMyanmar in November in the hope of achieving progress on the reopening offurther border checkpoints. On the other hand, the other main contender tolead Thailand’s next coalition government, the opposition Democrat Party,forms part of ASEAN’s emerging “pro-democracy” axis. They are thus likely tojoin with the Philippines in urging caution on Myanmar’s entry.

The Thai military may be losing patience with the SLORC. The increasinginflux of refugees is one area of concern. In addition, Thai efforts to normaliserelations along the common border have been largely frustrated. A checkpointat Ban Wang Lao in Chiang Saen district did open in July, but this develop-ment was regarded as a mixed blessing by the local Thai military. The main aimof reopening the crossing was to enable the resumption of construction of aThai-owned casino on the Myanmar side of the border. The Thai military andlocal people have criticised the casino as a likely magnet for various forms ofillegal activity such as smuggling, drug-trafficking and money-laundering. A

20 Myanmar

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

second casino, to be located nearby in Tachilek and owned by the third son ofopium warlord Khun Sa, is due to open next year.

The US-modified sanctionsbill becomes law

On September 30 Mr Clinton signed into law the Foreign Operations Appro-priations Bill, incorporating the Cohen-Feinstein amendment on Myanmar.This amendment requires a ban on US investment in Myanmar if the SLORC“has physically harmed, rearrested for political acts or exiled Aung San Suu Kyi,or commits large-scale repression of the democratic opposition”. In October adebate was reported to be going on in the Clinton administration aboutwhether the latest crackdown amounted to such “large-scale repression”. Someofficials argued against immediate action in the hope of developing a coordi-nated approach with Japan, the EU and ASEAN.

Myanmar officials arebanned from entry to

the USA

On October 3 a proclamation banned Myanmar government officials and theirimmediate families from entering the USA, a move described by a State Depart-ment spokesman as consistent with the Cohen-Feinstein amendment. TheSLORC retaliated in kind, also barring visiting US government officials andtheir immediate families from entering Myanmar.

Another US firm hassecond thoughts about

Myanmar

The “selective purchasing” laws passed by several US cities and the state ofMassachusetts are proving to have some bite. The computer maker, Apple, hasdecided to cease doing business in Myanmar in response to the Massachusettsstate law passed in June barring companies engaged in Myanmar from receiv-ing state contracts. The first casualties of the law could be the Dutch banks,ABN-Amro and ING, which had separately been considering making bids forBankBoston, the largest bank in Massachusetts. Both Dutch banks have repre-sentative offices in Yangon. Because in the event of a takeover by either,BankBoston would not be eligible for state business, a successful Dutch bidnow looks unlikely. Apple joins a lengthening list of US companies, mainlysub-contracting garments manufacturers, which have ceased operations inMyanmar (3rd quarter 1996, page 20).

The USA has sought todiscourage investment

According to the Washington-based Investor Responsibility Research Centre,there were 20 US and 130 foreign companies with employees or direct invest-ments in Myanmar, as of August. However, the US administration gives littleencouragement to US companies investing in Myanmar. The US Embassy’sForeign Economic Trends Report, published in July (3rd quarter 1996, page 19),sketches out the USA’s extremely limited relationship with Myanmar. The USAhas not had an ambassador in Yangon since 1990. The only US governmentagency active in Myanmar is the US Information Agency (USIA), whose chiefactivity is the “Voice of America” broadcasts to Myanmar (which have beenjammed intermittently since last year).

As the SLORC has not been certified as cooperating in efforts to stamp out thedrugs trade in Myanmar, by law the USA is required to veto assistance from theIMF, the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (ADB). Humanitarianassistance from the multilaterals and Paris Club debt relief are also barredbecause of US concern about the SLORC’s high level of military expenditure,lack of macroeconomic transparency and violations of human rights. Althoughas a member of the WTO Myanmar enjoys Most Favoured Nation (MFN) status

Myanmar 21

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

with the USA, it does not have Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) privi-leges or textiles quotas, and US exporters to and investors in Myanmar do notbenefit from Export-Import Bank or Overseas Private Investment Corporation(OPIC) financing or services.

The EU stops short ofsuspending visas

On October 28 the EU foreign ministers followed the example of the USA andforbade the entry of senior SLORC officials into their countries. On October 22the European Parliament unanimously adopted a resolution calling inter aliaon the Council to “respond to Aung San Suu Kyi’s request that the EU imple-ment economic sanctions against the SLORC by ending all links between theEU and Burma [Myanmar] based on trade, tourism and investment.” Despitethis, stronger measures are unlikely to follow this year.

A decision by the EU on withdrawing GSP privileges because of the use offorced labour in Myanmar is now expected in January. Meeting in Luxembourgjust before the late September crackdown in Yangon, the European Council ofMinisters decided to postpone its decision until after the WTO meeting inSingapore in December, where the WTO’s position on its social clauses is to beclarified. During the September discussions there was reported to be a splitbetween the Scandinavian countries, led by Norway and Denmark, and Franceand Germany, which were reluctant to alienate ASEAN. The UK has argued thatharsher sanctions would more appropriately be taken within a UN framework.

Tokyo keeps a low profile Japan has been rather less outspoken. However, on September 30, after theSLORC had succeeded in aborting the NLD conference, a Japanese governmentspokesman said that: “The freedom of political parties to conduct their activitiesmust be recognised.” The statement seems not to have impressed Aung San SuuKyi. In an interview with Mainichi Daily News published on October 5, she said:“I am watching and waiting for Japan to issue a statement with firm resolution.”

Officials claim success fordrug-eradication

programmes

The USA is required to veto multilateral lending to Myanmar under restrictionsrelating to countries that produce and traffic drugs, and which fail, in theopinion of the USA, to comply with efforts to control the drugs trade. Thisstatus is assessed each year. Evidence suggests that the surrender of warlordKhun Sa and his Mong Tai Army (MTA) disrupted the opium trade only briefly,if at all (3rd quarter 1996, page 18). However, the SLORC claims to have thedrug-cultivators and drug-traffickers on the run. It cites the rising price ofheroin on the Myanmar-Thai border as proof of the success of its anti-narcoticsefforts. The price rose seven-fold over the period April to September accordingto a September report in the state-owned magazine Gawthaw.

On October 1 the chief of the police anti-narcotics department, Colonel NgweSoe Tun, said that there were three main anti-narcotics strategies being em-ployed at present.

• Reduction of opium production combined with development of the borderareas.

• Reduction in drug use through registration and treatment of addicts andpreventive measures primarily involving education.

• Cooperation with regional and international bodies.

22 Myanmar

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

The ILO charges Myanmarwith breaching its

conventions—

In June Myanmar was requested to appear before the Committee on the Appli-cation of Conventions and Recommendations (CACR) of the InternationalLabour Organisation (ILO), to face charges of violating conventions it hadratified. It was asked to explain for the second year in a row (and the third timesince 1992) why it had failed to respect Convention No 29 on forced labourand (for the ninth time) why there were no trade unions in Myanmar inviolation of Convention No 87 on freedom of association. Last year theSLORC’s arguments on these counts had been so unconvincing that the com-mittee took the unusual step of including “special paragraphs” in its finalreport stressing that Myanmar must uphold the two conventions.

This year the SLORC changed its defence, arguing not that people had beencarrying out voluntary labour in accordance with cultural tradition, but thatafter the ceasefires with the ethnic insurgent groups the government had tofind something for its troops to do and had set them to work on infrastructureprojects. The committee was unconvinced and once again cited the SLORC in“special paragraphs” in its report. In addition, worker members of the ILO’sGoverning Body from 25 countries used a procedure resorted to only in themost blatant cases of abuse, filing a complaint against the SLORC for violationof Convention 29. The outcome of such a complaint is that a Mission ofInquiry must be set up to investigate the allegations. The mission is expectedto be set up in November and the investigation is expected to take 1-2 years.Companies doing business in Myanmar “under conditions where the provi-sions of the convention are clearly ignored” may be cited in complaints.

—and the SLORC responselooks unconvincing

The SLORC has already taken some steps to deflect such criticisms, althoughapparently with limited affect. It has set up a body to review the Village Act of 1908and Towns Act of 1907, which provide for the forcible recruitment of labour(1st quarter 1996, page 13). In addition, SLORC Directive No 125 was issued inJune 1995 “prohibiting unpaid labour contributions in National DevelopmentProjects”. This was sent to State and Division Law and Order Restoration Councilsand copied to the Ministries of Agriculture, Railways and Construction. The direc-tive noted that it had become common practice for people to “contribute labourwithout compensation” to “national development projects”. The directive wasappended to the report submitted by the then rapporteur to the UNCHR, ProfessorYozo Yokota, in February 1996. However, reports indicate that the directive didnot put a stop to forced labour.

The military chiefs visitChina

A top-level military delegation, including the commanders of all the threearmed services, left for a ten-day visit to China on October 22. They werereturning the visit made in April by a 16-member Chinese group. The Myanmardelegation was led by the army commander-in-chief, General Maung Aye, andincluded the navy commander, Rear-Admiral Tin Aye, and the air force chief,Lieutenant-General Tin Ngwe. The Chinese news agency, Xinhua, reported thedelegation’s departure but gave no clue as to its business. Since 1992 China hassupplied Myanmar with a variety of weaponry, including artillery, aircraft andpatrol boats, with an estimated value of $1.2bn. China’s growing military andeconomic involvement in Myanmar has been cited, particularly by the ASEANcountries, as a reason for other nations to engage with the SLORC.

Myanmar 23

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

The SLORC and the RedCross fail to reach

agreement

The SLORC has been trying to persuade the International Committee of theRed Cross (ICRC) to reopen its office in Yangon. This was closed in July 1995after the SLORC refused to agree to a memorandum of understanding thatwould have allowed the ICRC free access to prisoners. (Myanmar ratified the1949 Geneva Convention and other humanitarian laws in 1992, and the ICRChad incorporated the principles contained in those laws in its memorandum ofunderstanding.) As the SLORC has refused to budge on the issue of free access,the ICRC office remains closed.

The economy and economic policy

GDP growth targets maynot be attainable—

The government set a GDP growth target for 1996/97 of 6.1%, below theaverage rate achieved during the Four-Year Short-Term Plan (1992/93-1995/96). However, even this may be slipping out of reach. The agriculturalsector remains the key to the outlook for growth, accounting for nearly 40% ofGDP in constant price terms, and over half of all output in current price terms.(By contrast manufacturing, which is expected to expand by nearly 14% thisyear, will still account for less than 10% of constant price GDP.)

—because of weakagricultural growth—

The officially projected GDP growth rate for 1996/97 depends on an assumedagricultural growth rate of 5.4% year on year. This is a fairly modest risecompared with the average annual rate of 8.8% seen during the four-year planperiod (1992/93-1995/96). However, even this may be difficult to achieve, dueto poor rice output. Rice, the key agricultural commodity, was forecast to riseby 6.8% in 1996/97. At the time the targets for 1996/97 were drawn up, therewere already doubts about this year’s main (monsoon) harvest. Because of pestattacks (3rd quarter 1996, page 22), the targeted 3.9% increase in output fromthe monsoon crop may not be met. Moreover, to achieve its rice output targetsthe government is relying heavily on a further sizeable 27% increase in outputfrom the second (summer) crop. This too looks doubtful in view of the difficul-ties that growing a second rice crop imposes on many farmers (1st quarter1996, pages 19-20).

Gross domestic product growth by sector(%; constant 1985/86 prices)

1992/93- 1996/97- 1995/96a 1995/96b 1996/97c % of totald 2000/01e % of totalf

Agriculture 11.8 8.8 5.4 38.1 5.4 37.2

Livestock & fisheries 6.8 5.6 4.5 6.8 n/a n/a

Forestry –4.5 –5.4 2.6 1.1 n/a n/a

Mining 21.1 16.6 13.8 1.4 18.5 2.3

Processing & manufacturing 11.7 10.2 13.8 9.8 7.4 10.1

Power 4.3 16.5 10.3 1.0 n/a n/a

Construction 25.2 15.7 4.5 3.7 n/a n/a

Services 4.8 7.1 6.6 16.8 6.8 17.3

GDP 9.8 8.2 6.1 100.0 6.0 100.0

a Provisional. b Four-Year Short-Term Plan period. c Plan target. d As projected for 1996/97. e Planned figures. f By 2000/01.

Source: Ministry of National Planning and Economic Development, Review of the Financial, Economic and Social Conditions for 1995/96.

24 Myanmar

EIU Country Report 4th quarter 1996 © The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 1996

Paddy production

1992/93 1993/94 1994/95 1995/96a 1996/97b

Output (’000 tons) 14,837 16,760 18,195 19,568 20,900c

of which: monsoon paddy (’000 tons) 13,901 13,875 14,391 14,865 14,923c

summer paddy (’000 tons) 936 2,885 3,804 4,703 5,977c

Sown acreage (’000 acres) 12,684 14,021 14,643 15,309 16,000 of which: monsoon paddy (’000 acres) 11,863 11,871 11,981 12,149 12,000 summer paddy (’000 acres) 821 2,150 2,662 3,160 4,000

Yield per acre (basketsc) 56.91 59.24 61.45 61.77 62.50 of which: monsoon paddy (baskets) 56.99 57.67 59.48 59.26 59.50 summer paddy (baskets) 55.78 68.21 70.26 71.33 71.50

Procurement (’000 tons) 790.4 923.1 990.8 1,000 1,000

a Provisional. b Plan target. c Calculated on the basis of 46 lb baskets per metric ton. d 46 lb basket.

Source: Ministry of National Planning and Economic Development, Review of the Financial, Economic and Social Conditions for 1995/96.

—and sluggish investment In addition to the disappointing outlook for the agricultural sector, the govern-ment is expecting a very modest real increase in investment in 1996/97 of just2.5%. No explanation of this low figure has been given, which is out of keepingwith the official claims that growth will be investment-led in the coming fiveyears (2nd quarter 1996, page 16). However, data published in the governmentReview of the Financial, Economic and Social Conditions for 1995/96 suggest that itmay be the result of a sharp contraction (of nearly 27% in current-price terms)in public investment.

Singapore headsinvestment approvals list

Between October 1988 and the end of September this year a total of $4.4mworth of foreign investment was approved. The main investors are: Singapore($1.1m), the UK ($1m), France ($499m) and Malaysia ($436m). Since August,therefore, Singapore has overtaken the UK as the country with the highestvalue of approved investments (3rd quarter 1996, page 20).

Investment growth

1991/92 1995/96 % changea 1996/97b % changec

Value (Kt m at constant 1985/86 prices) 9,188 16,096 15.0 16,497 2.5

% of GDP (at current prices) 14.7 11.7 n/a 11.3 n/a

% of GDP (at current prices)d 21.1 18.2e n/a n/a n/a

a Annual average increase 1991/92-1995/96. b Plan target. c 1996/97 compared with 1995/96. d Based on legal exchange rate adjusted GDPcontained in US Embassy Foreign Economic Trends Report. e 1994/95.