Places – and faces – that foster student success - ERIC

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Places – and faces – that foster student success - ERIC

Summer transition programs

If you build it, will they come?

Reinventing the gateway class

The computer as a retention tool

Exploring the ‘Cheers’ effect

The power of community

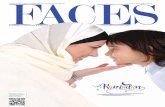

On the cover: A service-learning program aided Lynell Westbrook at Indiana University Bloomington.

Page 614 Page

Page 2228 Page

36 PagePage 32

Lessons: on the inside

Five years ago Lumina Foundation for Education issued achallenge. Envisioning Indiana as a laboratory, we invited sixof the largest universities in our home state to experiment withnew strategies to improve the persistence rates among theirunderserved freshman and sophomore populations. Two yearslater we expanded the list of these President’s Fund grants toinclude nine regional campuses.

Our grant awards were intentionally modest – no morethan $100,000 per school – to encourage creativity and sus-tainability. We certainly didn’t expect to solve the complexproblem of retention with a $1.5 million grant initiative; wemerely hoped to discover and document several promisingprogram components that we might share with other educa-tors, funders and policymakers interested in boosting studentsuccess. The goal of our grants was to give college adminis-trators the funds to push their retention efforts to the next level.We wanted them to put into practice ideas that frequentlysurfaced during brainstorming ses-sions when participants prefaced theirthoughts with the words: “What if…?”

We limited our “test sites” to Indi-ana for two reasons. First, proximitymeant that we could easily gatherteams from participating schools foroccasional conferences where theycould swap ideas and offer advice.Second, we recognized that the mixof Indiana schools mirrors severaltypes of institutions found in almostevery state of the union. Among ourgrantees were commuter and residential schools; a privatenational university and several public state universities; cam-puses with student bodies as small as 2,500 and as large as39,000; schools with enrollment policies that ranged fromopen to highly selective. We even included a program basedat a state correctional facility. We believe the lessons learnedand the successes experienced in such diverse environmentsare likely to have application in other settings.

The results of this experiment make up the content of thispublication. We offer it in the hope that retention-mindedinstitutions outside our “laboratory” will sift through thefindings and identify program components that might ex-pand the comprehensive plans that they already have inplace. Some outcomes surprised us; others confirmed whatwe already suspected; a few invite further study. Withoutexception, all added to our growing knowledge about thevital issue of enhancing college access and success.

Martha D. LamkinPresident and CEOLumina Foundation for Education

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

What if…?Supporting a laboratory for change

We hope you enjoy this first issue of LuminaFoundation Lessons, an occasional publication inwhich we will share the results of our grantees’work. By thoughtfully evaluating the programs wefund and then sharing what we learn, we hope tobroaden the impact of our grant making, while alsoboosting the effectiveness of the organizations andindividuals who do the vital work of increasingstudents’ access to and success in college.

Ball State University in Muncie is aresidential campus with an undergrad-uate enrollment of about 16,000.Through a program called FreshmanConnections the school has improvedits retention of first-year students from67.5 percent in 1996 to 76.9 percent ineight years. It has raised retentionamong second-year students from 67.5percent to 76.6 percent in the same period. (www.bsu.edu)

Indiana University Bloomington typi-cally enrolls about 30,000 studentseach fall. The persistence rate from thefirst year to the second year for beginning,full-time students averages 88 percent.About 49 percent graduate within fouryears; about 70 percent graduate withinsix years. (www.iub.edu) The service-learning program that was expandedwith Lumina funds has its own Web siteat www.indiana.edu/~copsl/.

Indiana University East in Richmond isthe newest and smallest of IU’s eightcampuses and has an undergraduate en-rollment of just under 2,400. The per-sistence rate from the first year to thesecond year for beginning, full-timestudents averages about 57 percent.The average six-year graduation rate isabout 20 percent.(www.iue.indiana.edu)

Indiana University Kokomo enrollsabout 2,800 students, 80 percent ofwhom work either full time or parttime. The campus has an average first-to-second-year persistence rate ofabout 58 percent for full-time, begin-ning students. The five-year averagegraduation rate is about 21 percent;however, IUK’s new strategic plan setsa target graduation rate of 30 percent.(www.iuk.edu)

Indiana University South Bend enrollsabout 6,500 students. The five-year av-erage fall-to-fall persistence rate forfull-time, beginning students is 66 per-cent. The five-year average graduationrate is 25 percent. About 60 percent ofthe student body attends school fulltime. (www.iusb.edu)

Indiana University Southeast, locatedin New Albany, enrolls about 5,700 stu-dents. The five-year average persist-ence rate for full-time, beginningstudents is 66 percent; the five-year average graduation rate is about 28 per-cent. Because of the school’s location,13 percent of the students are Ken-tucky residents. (www.ius.edu)

The University of Notre Dame, lo-cated near South Bend, is an independentCatholic university with about 8,000

undergraduate students. Highly selec-tive, the school receives more than fiveapplicants for each freshman class posi-tion and has a retention rate of 96 per-cent. In place since 1986 is theBalfour-Hesburgh Scholars Program(www.balfourscholars.nd.edu), a four-week summer experience that workswith incoming freshmen from histori-cally underrepresented minoritygroups. (www.nd.edu)

Purdue University in West Lafayettehas an enrollment of slightly morethan 38,000 students on its main cam-pus. Overall, 84 percent to 87 percentof first-year students return for theirsophomore year, and about 68 percentgraduate within six years. The univer-sity started offering learning commu-nities in 1997 and currently offers 26different options – including the fourmulticultural learning communitiesstarted with Lumina funds – for studentson the main campus. (www.purdue.edu)

Indiana University Purdue UniversityIndianapolis typically enrolls about29,000 students – a majority of themcommuter students – on its campus indowntown Indianapolis. Just 865 of thestudents are African-American males.In 2003 when the university started achapter of the nationwide mentoring

4 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

Fifteen university campuses in Indiana accepted

Lumina Foundation’s challenge to create or

enhance programs to improve student success

in the first and second years. Here is a snapshot

of each of the President’s Fund institutions.

organization,Student AfricanAmericanBrother-hood,

only 12 percent ofIUPUI’s African-Ameri-

can male students gradu-ated in six years. Overall,

about 25 percent of all of theuniversity’s students graduate in

six years, although the statistics donot capture students who transfer to

other campuses to complete their stud-ies. The school was created in 1969 as apartnership between Indiana Universityand Purdue University with IU as themanaging partner. (www.iupui.edu)

Indiana University Purdue UniversityFort Wayne enrolls about 12,000 stu-dents, and most work off campus an av-erage of more than 20 hours per week.Many students are the first in their fam-ilies to attend college, and many fresh-men test into at least one developmentalcourse in reading, English or math.Only 20 percent of students graduatewithin six years. The campus, which ismanaged by Purdue University, openedin 1964 when Indiana University andPurdue University decided to offerclasses in one location. (www.ipfw.edu)

Purdue University North Central is acommuter campus located in Westville.Nearly 3,500 students attend classes there,and the college runs two programs at near-by prisons – the Westville CorrectionalFacility and the Indiana State Prison-Outside (ISO), a minimum-security unit atMichigan City. Since 1985 the universityhas awarded 449 certificates, 406 associ-ate’s degrees and 76 bachelor’s degrees toprisoners at Westville. In 2000 the univer-sity began offering classes at ISO andsince then has awarded 20 certificatesand 11 associate’s degrees. (www.pnc.edu)

Purdue University Calumet in Ham-mond has a student population of about9,300. Nearly 80 percent come fromthe surrounding area in northwest Indi-ana, and three-fourths are the first intheir families to attend college. Minor-ity students make up 31 percent of thestudent body, and the campus has moreHispanic students than any other uni-versity or college in the state. Overall,64 percent of freshmen return for theirsophomore year, and 23 percent of students graduate within six years.(www.calumet.purdue.edu)

Indiana University Northwest in Garyenrolls nearly 5,000 students – 99 per-cent of them from northwest Indiana.African-American and Hispanic students

make up 35 percent of the student pop-ulation. About 57 percent of freshmenreturn for their sophomore year, andabout 25 percent of students graduatein six years. (www.iun.edu)

Indiana State University in Terre Hauteis a residential campus. About 10,500students are enrolled on campus and inthe university’s corrections-education anddistance-learning programs. About 40percent of students come from homeswhere neither parent has attended col-lege. At the time of the President’s Fundgrant, about 70 percent of beginningfreshmen returned for the second yearof classes. The retention rate now is 68percent. (www.indstate.edu)

University of Southern Indiana inEvansville started as a regional campusof Indiana State University and in 1985became a separate state university. About10,000 students are enrolled, and about40 percent come from homes whereneither parent has attended college. In 2003 it used its Lumina Foundationgrant to start a series of e-mail “lessons”to students and parents to help studentssucceed. Freshman-to-sophomore re-tention jumped by more than 10 per-centage points when both students andparents participated in the “lessons.”(www.usi.edu)

5 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

When Carla DeLong graduated from high school in

1987, she told her dad: “If I were to go to college now,

I would waste your money.” Not until she was 34 years old and

wandered into a college fair did she seriously consider return-

ing to the classroom and pursuing a degree. But was it too late?

“I talked with an admissions counselor from Indiana University

Southeast (IUS) and told her my brain was turning to mush,”

recalls DeLong. “I didn’t think I was smart enough for college

because school is so different now… much more ‘high tech.’”

Summer transition programs

Jump-starting the freshman year

7 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

Her timing was excellent. IUS wasabout to launch a program called Ac-cess to Success, supported by a LuminaFoundation President’s Fund grant. “Itook a leap of faith and quit my job,”says DeLong. “I didn’t know the collegelingo, I had no direction, and I neededhelp. The people at IUS took me bymy hand and walked me through myfirst two years.” Now a junior with agrade point average of 3.3, she jugglessingle parenthood, a demanding aca-demic load, part-time work and an in-ternship. She also takes time to mentoryounger students, often inviting themto her house for study sessions. “Theycall me ‘Mama,’” she jokes.

DeLong credits her success in part toIUS’s Collegiate Summer Institute, acomponent of the school’s Access toSuccess program. IUS is one of threeregional campuses within the IndianaUniversity system that used their Presi-dent’s Fund grants either to launch orenhance summer programs intended tojump-start the freshman experience. Although each school – IU SouthBend, IU Kokomo and IU Southeast –experimented with different ap-proaches, all faced similar challenges.

Because IU’s regional campuses are notresidential, students come and go at various times and divide their attentionamong home, school and work. Build-ing a sense of community is difficult.The target populations of the summerprograms were at-risk students who often are “fragile,” according to Stu-art Green, vice chancellor at IU Kokomo (IUK). “They’re easily bruised,” he explains. “When they have negative experiences, they’re more likely to turn and walk away.”Among these at-risk populations were Twenty-first Century Scholars, low-income students who sign a pledge in the eighth grade in return for the state’s guarantee of public col-lege tuition. The students agree to complete high school with at least a C average, remain drug-free and crime-free, apply for financial aid, and enroll at an Indiana college within two years of high school. They often are first-generation collegestudents with marginal SAT scores.

Well acquainted with these chal-lenges, the three regional schoolsnonetheless created summer programsthat had ambitious goals. By the end ofthe grant period, not every componentof each plan had met expectations, andsome aspects of some programs had un-dergone major adjustments. Regardlessof eventual outcomes (graduation statis-tics may take years to compile becausecommuting students frequently drop inand out of school), each program con-tributed findings to existing research onhow to serve underrepresented collegefreshmen on nonresidential campuses.

IU South Bend: High energy,record results

Three characteristics set IU SouthBend’s Leadership Academy apart fromthe summer initiatives at IU Kokomoand IU Southeast. First, the programwasn’t limited to incoming collegefreshmen but also included rising highschool seniors. Second, the target pop-ulations were specifically minorityyouth with solid grades. Third, theAcademy wasn’t a new program; it hadbeen in place since 2002 and alreadyhad proven effective in preparing par-ticipants for the transition from highschool to college.

The infusion of Lumina funds al-lowed IUSB to expand the summerLeadership Academy as part of a com-

prehensive plan to increase the minor-ity presence on campus. Goals for theplan were to increase the recruitment ofminority students at IUSB by 20 per-cent and boost the first-to-second yearminority retention rate by 2 percenteach academic year of the grant period.“When we submitted our proposal toLumina, we wanted to enlarge theAcademy so we could work with morestudents,” explains Karen White, asso-ciate vice chancellor for student serv-ices. “Identifying, recruiting andretaining Hispanic students became acritical component.”

Recent census data for South Bend hadunderscored the need to reach out tostudents of color. The African-Americanand Hispanic populations in the cityrepresented 11.5 percent and 7.2 per-cent, respectively, of the general popu-lation. The South Bend CommunitySchool Corporation reported that mi-nority students constituted 48.6 per-cent of its total enrollment. Yet for2001-2002, IUSB had enrolled only 22 Hispanic students and 48 AfricanAmericans. One of the first priorities ofthe Lumina-funded program was to hirea bilingual recruiter/adviser to make in-roads with Hispanic families. Whitefound the perfect candidate in CynthiaMurphy Wardlow.

“I make at least two visits to each ofthe four high schools in our area eachyear,” explains Murphy Wardlow. “Iwork closely with the guidance coun-selors who know the kind of studentswe hope to recruit into the LeadershipAcademy.” The counselors frequentlytake Murphy Wardlow into their cafe-terias at lunchtime and introduce her togroups of minority students. “Then Ijust plop down and talk with them inSpanish,” says Murphy Wardlow.

Her strategy works. Karen White de-scribes Murphy-Wardlow’s influence as“huge” in attracting Hispanic studentsto the Leadership Academy and eventu-ally to IUSB as freshmen. “Cynthiatakes a case-management approach, sowhen students and their families comein, she meets all their needs. She walksthem through the admissions and finan-cial aid process, and she does it ineither English or Spanish.”

The staff of the Leadership Academy

8 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

“I didn’t know the college

lingo, I had no direction, and I needed help. The people at IUS took me by my hand.”

Carla DeLong

Carla DeLong – a junior and a peer mentor at Indiana UniversitySoutheast in New Albany – takes a break from her own homework towork with her daughter, Breonna Jenkins, on language drills.

also works hard to reduce language andcultural barriers. Students are assignedto mentors who attend classes, takenotes and lead small-group “debriefing”sessions at the end of the day. Severalof the mentors are bilingual upperclass-men and serve as role models, as well asfriends, far beyond the eight-week sum-mer Academy.

The curriculum is designed to buildconfidence and instill ethnic pride.English class helps develop speakingand writing skills; history class focuseson the civil rights movement in theAfrican-American and the Hispaniccommunities. The professors who teachthe courses are selected for their cre-dentials and for their animated presen-tation styles. “We definitely don’t waterdown the class content,” says ProfessorHayley Froysland, an expert on theChicano movement who integrates filmclips and music into her lectures.

Overseeing the Academy is RobertBedford, director of Multicultural En-hancement, who greets students byname when he leads a 10-minute“warm-up” session before classesbegin. “When I was hired two yearsago, someone warned me that the kidsin the Leadership Academy sort ofwander in at different times in themorning,” he says. “I created a graceperiod when we gather in the lobby ofthe academic building to sing and doicebreaker activities. By 9 o’clockthey’re ready to settle down and headfor class.”

The chemistry that exists among theAcademy’s administrators, mentors andteachers is palpable and probablyhelped the program meet most of itsgoals. In fall 2005, the final year of thegrant, campus minority enrollment atIUSB was at 11.7 percent, an all-timehigh. The number of Hispanic studentsincreased from 192 to 221, anotherrecord. The campus succeeded in in-creasing minority recruitment by 20percent but fell short of improving itsretention statistics by 4 percent. His-panic first-to-second-year retentionnumbers exceeded the grant targets,but African-American retention num-bers slipped between 2003 and 2004.Most impressive: 100 percent of theLeadership Academy high school

graduates enrolled at IUSB immedi-ately after Academy participation.

Recognizing the value of having a Hispanic enhancement recruiter/adviser on campus, the university insti-tutionalized the position at the end ofthe grant period. As Vice ChancellorKaren White notes, “It pays for itself.”White hopes to add a similar full-timestaff member to reach out to African-American students.

IU Kokomo: Low enrollmentthwarts bridge program

Months before the launch of theSummer Transition Program at IUK,coordinator Carol Garber visited 12area high schools, sent letters to poten-tial participants, followed up with per-sonal phone calls and distributeddozens of application forms.

“About 50 students went through theentire process of filling out the paper-

1 0 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

work,” she recalls. The goal, establishedin the Lumina grant proposal, was toserve 25 to 30 incoming Twenty-firstCentury Scholars each summer for twoyears beginning in 2004. Faced withthe possibility of enrolling twice theanticipated number the first year, Gar-ber says she panicked. “I rememberthinking, What am I going to do with allthese students?” She needn’t have worried.“We ended up with 13. The desire to

participate in the program was there,but the means were not.”

In designing the six-week Lumina-supported program, IUK officials im-proved on what Vice Chancellor StuartGreen estimated were “about 10 years’worth of models.” Earlier versions hadconvinced Green and his colleagues thatsummer program participants were morelikely to persist if they built a connec-tion to the campus, earned college

credits that counted toward graduation,and moved directly from a summer pro-gram in August to a year-long learningcommunity in the fall. Green likenslearning communities to “scaffolding”that provides support while studentsdevelop their academic and social skills.

“It’s not about intelligence; it’s aboutexperience,” explains Green. “Mentor-ing students in a pre-matriculation pro-gram in the summer and then followingthrough with guidance and counselingseems useful.” Voluntary learning com-munities already had a five-year historyat IUK and had proven their value. Thefall-to-fall retention rate for studentswho participated in learning communi-ties was 71 percent; the fall-to-fall per-sistence rate for students who did notparticipate in learning communities was44 percent. A key to the learning com-munities’ success was that each commu-nity stayed intact for both semesters ofthe freshman year.

“The same students take 12 hours ofclasses (two courses each semester)from the same three faculty members,”explains Susan Sciame-Gieskcke, deanof the School of Arts and Sciences andoverseer of IUK’s learning communi-ties. “There’s social interaction withinthe community during class and onfield trips. We have a tutoring center,and we encourage students to use it.Our goal is to get them to the sopho-more year.”

The expectation in 2004 was thatthe Lumina-supported summer pro-gram, which included two for-creditcourses, would help achieve this goal.Program planners knew that their tar-geted population would find the sum-mer courses challenging. Typically,Twenty-first Century Scholars who en-roll at IUK have graduated from highschool in the 50th to 60th percentile andhave average SAT scores of 880 to 940.Their persistence rate is 10 percentagepoints below the rate of other enteringfreshmen. An additional obstacle tostudent success is employment. Of the13 participants in the first summer pro-gram, four worked 40 or more hours aweek. All but three of the 13 partici-pants in the 2005 cohort held downpart-time or full-time jobs. “Our stu-dents come from a radius of 50-plus

Robert Bedford, director ofMulticultural Enhancementat Indiana University SouthBend, leads a pre-class"warm-up" discussion withstudents Adele Burnett(left) and Priscila Rodriguez.

1 1 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

miles,” explains Sciame-Giesecke.“Some young people have to work 25or 30 hours a week because that’s whatit costs to pay for gasoline.”

Disappointed by the low level of par-ticipation in the first year of implemen-tation, IUK administrators madeadjustments prior to the second year’sprogram. They set aside a portion ofthe Lumina funds to add a fall learningcommunity course aimed at the tar-geted students; they made an effort toeducate parents on the rigors of collegeacademics; and they eased enrollmentrequirements for the 2005 summer pro-gram and opened it to at-risk studentswho were not Twenty-first CenturyScholars. Eighteen responded to theopportunity, but five dropped out forreasons that ranged from childcareproblems to job obligations.

In spite of the lackluster turnout, stu-dents in both summer sessions gavehigh marks to several aspects of theprogram. In filling out an evaluationquestionnaire, they responded thatthey appreciated the opportunity toearn six hours of credit in an abbrevi-ated timeframe and enjoyed “getting toknow people before fall classes start.”The students also unanimously an-swered “yes” to two key questions:

Are you comfortable on the IUK campus?Do you feel more confident in your ability as a student?At the conclusion of the grant pe-

riod, the university decided not to con-tinue the summer transition programbut agreed to underwrite the expandedlearning community class that Luminafunds had made possible. Staff mem-bers concurred with the decision andoffered suggestions on ways tostrengthen future retention efforts. Stu-art Green believes that freshmen shouldhave the opportunity to apply for on-campus jobs that often are reserved forupperclassmen. Such an arrangementwould alleviate the financial burdens onmany incoming students, eliminatetravel time between school and work,and help students become familiar withthe campus. Garber would like Twenty-first Century Scholars to have the optionof attending part time at the beginningof their college careers, and she would

like more retention programs availableto part-time students, as well as tothose freshmen who enroll full time.

Although her on-campus duties havenow changed, Garber keeps in touchwith many summer school participantsand is proud when they credit the sum-mer program with launching them ontocareer paths. One of these students,John Kelderhouse, a participant in the2004 program, maintains a 3.9 GPA. “In

fall 2006, I will start my third year ofstudy at IUK in the business programwhile focusing on accounting,” hewrote in an e-mail to Garber. “I’m ontrack to graduate in May 2008.”

Other success stories may go undoc-umented. “Commuter campuses have avery high stop-out rate,” admits Green.“Once students stop out, they’re listedas attrition statistics.” The good news isthat many of them find their way backto campus several months or years later.“Some go on to other institutions, somego into the military,” says Green. “Butthe reality is that they come back and,after several tries, they make it.”

IU Southeast: Paraprofessionals are key

Unlike the IUK program thatbrought students to campus Mondaythrough Thursday, 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. forsix weeks, the Collegiate Summer Insti-tute at IU Southeast met only on fourconsecutive Fridays for an intense ori-entation program. In their Luminagrant proposal, IUS staff membersspecified that 30 new students wouldparticipate in the program the firstyear, and that number would doublethe second year. Three targeted popu-lations – Twenty-first Century Schol-ars, minority students and adultlearners – would have equal representa-tion. For this select group of 90 stu-dents, the summer institute (aptlycalled CSI) would replace IUS’s regularorientation program that was a singlehalf-day session and was very fast-paced.

“We found that students in the targetedcategories wanted more hands-on train-ing,” explains Greg Roberts, an academicadviser who developed and coordinatedthe expanded summer program. Amongthe goals was to acquaint incomingfreshmen with campus resources, registerthem for fall classes, and launch thelong-term peer-to-peer mentoring rela-tionship that was the key to the Lumina-funded Access to Success program.

“Student-to-student contact is a pow-erful tool,” says June Huggins, director ofthe Center for Mentoring and StudentOutreach. “I have very high expecta-tions for our peer mentors. I tell them tostep out of their student roles becauseas mentors they are paraprofessionals.The worst thing is to have a mentorwho fails you in some way; but when arapport develops between a student anda mentor…that is a beautiful thing.”

Each peer mentor received an annualstipend of $1,000 and underwentmandatory training. Huggins matchedmentors and students according to age,major, interests and gender. During thefirst five weeks of the fall semester, thepeer mentors met weekly one-on-onewith their protégés to build bonds andprovide support and guidance.

Throughout the remainder of the falland spring semesters, the mentors andtheir charges met at least every two

“I have very high expectations

for our peer mentors. I tellthem to step out of their

student roles because as

mentors they areparaprofessionals.”

June Huggins

1 2 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

weeks. In addition, the duos attendedtwo large-group gatherings together.The one-on-one relationship continuedthe second year, but without a pre-scribed number of meetings.

“We don’t want to hover; we justwatch and guide the students,” explainsAtta Okyere, a student from Ghanawho mentors Dilu Nicholas, a studentfrom Sri Lanka. “If Dilu were to startmissing classes, I would call him andmake an appointment to talk.”

Each mentoring relationship is differ-ent, depending on the persons involved.Carla DeLong views her mentor as abig sister. “We’re total opposites, butshe’s wonderful,” says DeLong, now amentor herself. “Once my car brokedown and I had no way to get toschool. She loaned me her car for aweek while mine was being fixed. It’slike having a built-in best friend.”

The Access to Success program andits CSI component came close to meet-ing all goals set forth in the Luminagrant proposal. The first year’s goal wasto enroll 30 new students in the program.Final tally: 29 enrolled in 2004, and 26remained in the program during springsemester for a 93 percent retention rate.The second year’s goal was to enroll 60.Final tally: 51 enrolled in 2005; ofthose, 44 continued their participationduring the spring semester for an 86percent retention rate. Both summer in-stitutes were successful, drawing 19 stu-dents the first year and 28 the secondyear. Of the 28 mentors hired for 2005,six were “alumni” of the 2004 Access toSuccess program for a rate of 21 per-cent (the goal was 25 percent).

Huggins believes much credit for theprogram’s success goes to the peer men-tors, an opinion shared by campus ad-

ministrators who agreed to fund 30peer mentors beyond the Lumina grantperiod. If any aspect of the program hassurprised Huggins, it’s been the successof the adult participants. “Once theybecame comfortable, they thrived,” shenotes. “We have several adult peer men-tors, and they are incredibly solid.”

One of those “incredibly solid” adultmentors is Carla DeLong. Now wrap-ping up her degree in criminal justiceand psychology, DeLong often sharesher story with incoming freshmen in thehope they will learn from it. “I tell themthat I wish I had gone to college when Iwas 18,” she says. “I made mistakes, butthank goodness, they weren’t criticalmistakes. I don’t regret what I’ve doneor the path I’ve taken. Now I see life asa classroom, and I learn something newevery day. Education has made me theperson I am today, and I like who I am.”

Cynthia Murphy Wardlow, a bilingual adviser at IUSB, meets with students at John Adams High School to discussthe steps they need to take to attend college. In part because she is fluent in Spanish, co-workers say her influencewith Hispanic students is “huge.”

1 3 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

The barriers to completing a college educationseem particularly steep for students attending

regional campuses of Indiana and Purdue universitiesin northwest Indiana.

Many are first-generation students working 20 to30 hours a week to pay the bills while going tocollege. Some have families to raise.

If you build it, will they come?

Support programs work,but attracting students remains a challenge

1 5 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

Other students entered college afterattending high schools where they hadto share books. Because each classroomhad only one set of books, studentscouldn’t take them home to study.

Some students dropped out of highschool, got in trouble with the law, andnow are returning to education as theirway out of prison – but it’s a long roadback when it’s been years since highschool algebra.

For these students, supplemental sup-port programs can be the differencebetween success and failure. Peer men-toring, tutoring, supplemental instruc-tion – all of these opportunities can tipthe scales in students’ favor. On aver-age, according to school statistics, 35percent to 40 percent won’t make it tothe sophomore year of college, and 75percent won’t graduate in six years.

“When you provide student support, itworks,” says Joe Pellicciotti, associate vicechancellor for enrollment managementand professor of public and environmentalaffairs at IU Northwest in Gary. “Thedifficulty is getting the students there.These are commuter students – they havefinancial, family and work issues. It’samazing they can do what they do. It’snot that they don’t recognize the impor-tance or don’t want to attend – they can’t.And it must be very frustrating to them.”

The orientation of learningAt IU Northwest, Psychology 101 is re-quired for most freshmen. Two-thirdsof first-semester freshmen enroll. Ifthey fail the first exam, they most likelywill fail the class. And 80 percent ofstudents who fail the class eventuallydrop out of school.

Professor Mark Hoyert, chairman ofthe psychology department, set out tochange those grim statistics. Motiva-tional differences separate students whosucceed from those who fail, Hoyertexplains. Some students are motivatedbecause they want to learn; others aremotivated by performance or grades. Injust about any class that Hoyert hasstudied, students are split – half possesslearning-oriented goals, and half gravi-tate to performance-oriented goals.

Through years of research, Hoyertdiscovered that learning-oriented stu-

dents increase their grades by as muchas 15 percent after failing the psychol-ogy course’s first exam; performance-oriented students show a decline afterfailing the first exam.

“We wanted performance-orientedstudents to adopt more learning-ori-ented goals to try to keep those stu-dents from abandoning their studies,”he says. He developed a tutorial aboutgoal orientation to do just that. The tu-torial includes exercises designed tohelp students adopt learning-orientedgoals and provides real-life examples ofsuccessful people.

Initially he and peer mentors workeddirectly with students to review the ma-

terial. But sometimes it was difficult toget students to attend the additionalsessions. With different people leadingsessions, the message wasn’t always consistent.

With a portion of the Lumina grant,Hoyert put the course content on a CDand called it GoFar Tutorial. He andother instructors started offering the CDto students who failed the first exam inPsychology 101.

The CD worked. About half of thestudents who failed the first exam vol-untarily agreed to complete the tuto-rial. Most of them – 85 percent – wereretained to the next semester. Only 53

percent of the students who failed thefirst exam and did not complete the tutorial returned for the next semester.

“It cuts the failure rate in half. That’sthe consistent finding no matter howmany students are involved,” he says.Hoyert says test failure is an importantcomponent of the tutorial’s success.The tutorial seems to have no effect onstudents earning a “C” or better on thefirst exam. “Because of the pressurefrom failure, students are willing to payattention.”

Hoyert asks students who completethe CD to write about their experience.One student wrote: “I will admit I ammore grade oriented. I always try to getgood grades and never really learn thematerial. I have a really bad habit ofcramming the night before [a test], andI know that’s really bad. But afterwatching the CD, I learned some newways to study and to not cram thenight before.”

The campus is now experimentingwith using the tutorial for other classes,including math, chemistry, anatomyand physiology.

Mentoring at-risk students indifferent waysPeer mentors can help ease the transi-tion from high school or work to col-lege for many students. These mentorsgenerally are successful students whohave had experience on campus and whohave received special training so theyknow the best ways to help new students.

“Students have a lot of barriers toovercome,” says Patricia Hicks-Hosch,director of student support services atIU Northwest. “These are first-genera-tion students. There are a lot of thingsthey don’t know. They are apprehen-sive and many times don’t know whatto expect. Having peer mentors helpsthem make the transition from life ex-perience to becoming a student.”

The peer mentor program thatHicks-Hosch oversees is one of twosuch programs on the campus fundedinitially through the Lumina grant. Ofthe 49 students who participated in theprogram during the 2005-2006 aca-demic year, 79 percent returned toschool for the fall 2006 semester.

1 6 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

GoFar TutorialFifty percent of the students who had failed the first exam in Psychology 101 at Indiana University Northwest voluntarily agreed to complete the tutorial.

Results: 60 percent of the students who completed the tutorial passed the class. 85 percent of students who completed the tutorial persisted to the next semester. Only 53 percent of students who failed the exam but did not complete the tutorial persisted to the next semester.

Source: IUN final report to Lumina Foundation.

Michael Jenkins, asenior history majorat Indiana UniversityPurdue UniversityIndianapolis, says hisinvolvement in SAABhelped him raise hisGPA from 1.8 to 3.0.

1 8 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

The program pairs mentors withgroups of six to 10 students, and stu-dents meet separately and in groupswith the mentors. Any student can re-quest a mentor, and many who do soare older students returning to school.Students also can take advantage oftwice-monthly meetings that focus on avariety of topics including job opportu-nities on campus, scholarship programsavailable to students, midterm and fi-nals prep sessions, cultural activitiessuch as trips to nearby Chicago muse-ums and theaters and much more.

Rachel Torres, a first-generationnursing student from Illinois who nowlives in Crown Point, Ind., joined thepeer mentor program two years ago.“As a freshman, I didn’t know a lotabout school activities or know aboutstudent insurance or the withdrawalsystem. I missed out on a lot of bene-fits,” she says.

IU Northwest also used Luminafunds to start a mentoring programaimed specifically at freshmen throughthe Special Retention Programs depart-

ment. The peer network pairs a mentorwith two to three freshmen.

“We want to give new students asense of connection and community,”says Cathy Hall, coordinator of SpecialRetention Programs. “We don’t wantthem to see this as a place where theystop by, take a class and go home.”

Initially, the program recruited stu-

dents to work with mentors by usingreferrals from faculty, staff and otherstudents participating in the supple-mental instruction program. Hall saysthis approach was not effective becausesome of the “recruits” saw the programas punishment. “They had a negativereaction coming in that way,” she says.The next semester the peer networkchanged its recruitment efforts to focuson freshman orientation and was able toincrease participation from four to 11students for the fall 2006 semester.

Peer mentor Jaclyn Hac says shewishes the peer network had beenavailable when she was a freshman.Hac, now a senior anthropology andsociology major, says she enjoys work-ing with students she mentors and en-joys watching them grow. “I think it helpsboth students really feel like a part ofthe school, and, if you feel that way,you’re bound to try harder and succeed.”

Connecting students to campus is abig part of what the Student AfricanAmerican Brotherhood (SAAB) does. A national organization started 16 years

IUPUI students Derrick Carpenter (left) and Michael Jenkins talk with SAAB chapter director Terrence Littlefieldabout the commitment and accountability expected of them as members of the organization.

“I think it helpsboth students reallyfeel like a part ofthe school, and, ifyou feel that way,you’re bound to try

harder and succeed.”

Jaclyn Hac

ago on a small college campus in Geor-gia, the group now boasts 126 chaptersand 2,000 members across the country.As part of its efforts to improve reten-tion, Indiana University Purdue Univer-sity Indianapolis (IUPUI) used part of itsLumina grant to start a SAAB chapter.

On a national level, SAAB hasproved effective at helping boost reten-tion and graduation rates for African-American males. In the last decade,SAAB has helped 80 percent of its par-ticipants persist from freshman to soph-omore year and 86 percent to graduatefrom college. These numbers comparewith a national freshman-to-sophomoreretention rate for African-Americanmales of just 42 percent and a five-yeargraduation rate for African-Americanmales of 55 percent.

At IUPUI, an urban, commuter cam-pus of about 29,000 students, only 865students are African-American males.“Our overall goal is to make sure theminority students – especially theAfrican-American males – are retainedand graduated,” says Terrence Littlefield,director of IUPUI’s SAAB chapter. Theodds are daunting: Before SAAB started in2003, just 39 percent of African-Americanfreshman males returned for a secondyear of school, and currently only 12percent of IUPUI’s African-Americanmales graduate in six years.

The organization holds weekly meet-ings on campus and provides mentoringservices to students, as well as informa-tion about services on campus. It alsoplans and carries out activities rangingfrom a campus talent show to careerworkshops to study sessions to lunch-eons with motivational speakers.

“We connect with students where wecan find them,” Littlefield says. “Re-search has shown that the more con-nected students are on campus, themore it helps with the academicprocess,” he says.

The numbers support Littlefield.During the three years of the grant, re-tention of SAAB members ranged from62.5 percent to 90 percent. In 2005,when SAAB had 20 members, the fourfreshman members earned a 2.75 grade-point average – nearly a full percentagepoint higher than the 1.85 GPA averagefor all African-American males on campus.

“Being involved with SAAB has reallyhelped my grades,” says Michael Jenk-ins, a senior history major at IUPUI.Jenkins, a first-generation student, sayshe has raised his GPA from 1.8 when hejoined SAAB to a 3.0. The camaraderieand study sessions helped, Jenkins says,as well as the accountability stressed inSAAB. “It’s also nice to be with otherswho know what it’s like to be the onlyblack student in the room,” he says,“and it’s easier to achieve when you seeothers like you who are achieving.”

His friend and fellow history major,Lewis Jones, concurs. “When I connectwith my brothers in SAAB, they say,‘That’s Lewis. He’s intelligent.’ I needthat time with people who respect mefor who I am.” Lewis returned to col-lege a few years ago after dropping outin 1980s. “If there had been SAAB 20years ago, I would have finished my de-gree then,” he says.

Preparing high school studentsto succeed in college

At Purdue Calumet, officials used Lu-mina funds to address factors that canhelp set the stage for college successbefore students ever arrive on campus.By cooperating with area high schools,they began an effort to enhance cur-riculum development and implementSupplemental Instruction (SI) at thehigh school level. Addressing academicdeficiencies they noticed in freshmen,they hoped to improve students’ prepa-ration for college-level work.

About 80 percent of the university’sfreshmen come from the area surround-ing the campus, located in Hammond,Ind., just outside Chicago. About 75percent of students are the first in theirfamilies to pursue a college degree, andabout 40 percent of enrolled studentslack the adequate high school prepara-tion for the rigors of college.

“The school systems told us theyweren’t aware of the gaps,” says Jacque-line Reason, assistant director of sup-plemental instruction and tutoring atPurdue Calumet. “It took a while toconvince them we genuinely wanted towork with their students.”

Over a two-year period, the univer-sity worked with three high schools –

East Chicago Central High, Clark Mid-dle and High School and Morton HighSchool in Hammond – to introduce theconcept of cadet teachers in math andEnglish classes. The university based theprogram on its own SI program, whichimproves student retention by an aver-age of 14 percent for students who at-tend at least one SI session, Reason says.

“This is the first time the university ismaking it our business to go to the highschools,” says Nabil Ibrahim, vice chan-cellor of academic affairs. “We arereaching out to the high schools, saying:These are the problems we’re facing – let’s worktogether to solve them.”

1 9 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

Student African American BrotherhoodNationally, SAAB has 126 chapters with a total of more than 2,000 members.

The organization has made signifi-cant strides in helping its members succeed in postsecondary education. For example, in the last decade: Eighty percent of SAAB members have persisted to their sopho- more year. (This compares to a national average of 42 percent for African-American males.) Also, 86 percent of SAAB members have graduated from college in five years or fewer. (This compares to a national five-year graduation rate for African-American males of 55 percent.)

Source: SAAB Web site www.2cusaab.org

Persisted tosophomore year

SAAB

80%

42%

Avg.

Graduated in five years

SAAB

86%

55%

Avg.

At the high school level, senior stu-dents who were identified by theschools and trained by Purdue, sat inon classes and offered small-group as-sistance during part of the classroomperiod, and some even taught part ofthe class. “Students who participated ascadet teachers became much strongerstudents,” says Ron Kovach, assistantvice chancellor for academic affairs.

In two years 46 students participatedas cadet teachers, and nearly all ratedthe program highly. Of the 33 partici-pants surveyed last year, 73 percentsaid the experience improved theirknowledge of the subject; 79 percentsaid the experience improved theircommunication skills, and 76 percentsaid being a cadet teacher was benefi-cial to them as students. Of the 11cadet teachers who participated in theprogram in the spring 2005, eight en-rolled at Purdue Calumet.

While the concept appears promis-ing, it faces limiting factors. The uni-versity was able to work with theschools to introduce the cadet teacherconcept, but the high school teachersdid not have the time to work with uni-versity officials to revamp course offer-ings. Likewise, summer internshipswere made available to students, butthey could not take full advantage ofthem because they had to work fulltime in the summer to earn money.

Nonetheless, both Kovach and Rea-son say the program has forged rela-tionships that will continue to benefitstudents in the future. “We thought weknew what they needed,” Reason saysof the high schools. “Through thisprocess we learned students don’t havetextbooks they can take home. Wewere shocked that there was one set ofbooks per classroom. It sounds like ‘Lit-tle House on the Prairie;’ yet this is EastChicago, 2006!

“It’s a much deeper problem thananyone thought,” she says.

The importance of tutoringThe men who find themselves incar-

cerated at the Westville CorrectionalFacility and the Indiana State Prison’sminimum-security unit at MichiganCity (ISO) can reduce their sentences

by achieving certain academic goals. Ifthey complete a vocational computerclass, they reduce the incarceration bythree months. An associate’s degreegets them a one-year cut, and a bache-lor’s degree results in a two-year sen-tence reduction.

For years, Purdue University NorthCentral at Westville has offered educa-tional programs – an associate’s degreein organizational leadership and super-

vision and a bachelor’s degree in liberalstudies – at the Westville facility. In2000, it began offering an associate’sdegree in general business at ISO. Toenroll in the Purdue program, the menmust pass a four-part exam, which in-cludes writing a two-page essay, com-pleting 40 math questions, answering80 vocabulary questions and respond-ing to comprehension questions onseven reading passages. Only one in 10

Purdue’s Diane Borawski, coordinator ofPostsecondary Correctional Education atPurdue University North Central, talksabout classes with inmates Mark Chinn(left) and John Trueblood while AnthonyHarris studies in the background.

2 0 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

applicants qualify – most of thembarely passing the exam, says DavidCrum, director of the Purdue programfor the Westville facility.

“The overwhelming majority of stu-dents end up in remedial math beforethey can take the required college-levelalgebra and trigonometry,” he says, not-ing that, if the prisoners can answer 15of the 40 questions, they qualify for re-medial math. In 2004, the university

used the Lumina Foundation grant topay for tutors to offer weekly or twice-weekly math sessions at both facilities.

The tutoring services have an uncer-tain effect on student retention becausemany factors influence an inmate’s com-pletion of a course or degree program,says Diane Borawski, Purdue coordina-tor for the ISO program. The Depart-ment of Correction can release ortransfer inmates at any time. During the

period tutoring services were available,the DOC changed the ISO to a mini-mum-security facility, which changedthe inmate population, and moved aspecific set of Westville’s prison popula-tion to another facility. Even so, anoverall student-retention rate of 59 per-cent occurred during the six semesterstutoring services were offered.

Statistics aside, the men who re-ceived tutoring say the sessions madeall the difference.

“I was lost at certain points and des-perate and discouraged,” says JohnTrueblood, a 43-year-old ISO inmateserving time for drug-related offenses.“The tutoring really helped. In the envi-ronment I grew up in, I wasn’t aware thata college education was within my grasp.”

Mark Chinn, another inmate at ISO,says he used the tutoring services everyweek. “I never had algebra – I’ve beenout of school 30 years,” he says. Al-though the tutoring services ended in2006, Chinn tries to use his knowledgeto help others who need it. “I enjoydoing it, and it’s pretty fulfilling to helpsomeone who doesn’t understand some-thing. There are so many guys here outof school for a while, and they want todo college, but they need the mathhelp,” he says.

Matt Diehl, an inmate at Westville,says the tutoring services helped himget through a statistics course. “It’s been12 years since high school. I barely re-membered fractions,” he says. Diehl, whois serving time until 2008 for drug-relatedcrimes, says the opportunity to takecollege courses has changed him. “I usedto be close-minded about a lot of things.College makes me more open-minded.”

Several other inmates echoed Diehl’ssentiments. Anthony Harris, who’sscheduled to be released from ISO inJune 2007, says the college experiencehas helped him learn about himself. “Itboosts your self-confidence. If youleave here without self-confidence, yougo back to the same ways,” he says.

“College helps you feel more confi-dent,” says Donald Shaw, who droppedout of high school at age 14. “I havemore knowledge about stuff that reallymatters. Instead of talking about drugsand stealing, I’m having conversationsabout economics.”

2 1 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

University of Notre Dame biology ProfessorHarvey Bender disputes the idea that class

size has little bearing on student success. “There’s amyth that says enrollment doesn’t matter once youget above a certain threshold level,” he says. “That’swrong. It’s more challenging to teach 50 studentsthan 25; it’s much more challenging to teach 100students than 50; and all sorts of problems can arisewhen you get into the 150- or 200-student range.”

Reinventing the gateway class

Teaching ensemble replaces ‘sage on stage’

2 3 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

Among the potential problems: fresh-men feel lost in introductory classesthat meet in large, impersonal settings.Struggling students go unnoticed untilthey are “outed” by midterm test scores.Faculty rely on lecture formats that castthem in the role of an intimidating“sage on stage.” Students must wait

their turns in long e-mail queues tocommunicate with instructors. Benderestimates that his human geneticscourse (BIOS 101), which enrolls 250freshmen each semester at NotreDame, generates as many as 40 e-mailmessages a day. In such oversized gate-way classes, students view professors

as obstacles, says Bender. “They ask,‘How can I get through, over or aroundyour gates?’”

Although Notre Dame’s retentionstatistics are enviable – 94 percent ofstudents graduate – the required twosemesters of science often challengestudents whom Bender describes as

2 4 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

Harvey Bender, a biology professor and director of Notre Dame's Human Genetics Program, leads a discussion groupthat includes students Erin Clemens (left) and Nick Manieri. The group meets weekly to supplement Bender's lecturesin an undergraduate class focusing on genetics research.

“science shy.” With support from aPresident’s Fund grant, he decon-structed his gateway course and re-placed the traditional sage-on-stagemodel with what he calls a “guide fromthe side” configuration. Friday discus-sion groups now supplement Bender’stwice-weekly lectures, and all sessionsare interactive to some degree. He cre-ated a three-level teaching ensemblethat includes himself, 10 undergraduateteaching assistants (UTAs), and a post-

doctoral mentor who acts as an inter-face between him and the UTAs. Ben-der personally oversees the recruitmentand training of his teaching team andmeets with them on Tuesday eveningsthroughout the semester to monitorprogress.

A key to the new course’s success iscommunication. UTAs, all of whomhave taken the genetics course or arescience majors, fully understand therigors of their commitment. They at-tend Bender’s lecture classes, and eachfacilitates a Friday morning discussiongroup of 25 freshmen. The UTAs keepjournals and read and react to the jour-nals of their discussion-group partici-pants. In return for all this work, theyreceive one hour of academic credit, a“benefit” that many say has little to dowith their motivation for applying forthe positions.

“I loved the experience,” says NicolePretet, who served as a UTA for two se-mesters. “I might want to go into teach-ing someday, and I thought this wouldbe a great way to explore whether Iwould enjoy that career down the road.”

“The program allowed me to workwith freshmen,” says Wen Liao, also atwo-semester UTA veteran. “When Iwas a freshman, I was lost. I didn’tknow where to go for academic guid-ance. Now I work with students whomight have the same trouble as I did.”

The role of the post-doctoral mentoris to act as a buffer, troubleshooter andfacilitator. “If a UTA has a problem andhesitates to approach Dr. Bender withit, I can provide insights from my per-spective as a teacher,” says DominicChaloner, an ecologist who found hismentoring role so satisfying that hestayed on for three semesters. In addi-tion to a modest salary, each mentorhas the opportunity to work alongsideBender, a Carnegie scholar. “I teach asmaller course in environmental scienceand have about 100 students,” explainsChaloner. “I’m using the model that Dr.Bender developed because I’ve seenhow it encourages class members todiscuss course material.”

Bender imposes strict quality-controlstandards on his course. He personallyled one of the weekly discussion groupsto gauge its effectiveness during the

pilot semester of the redesigned course.In subsequent semesters he admits to“prowling the halls” on Fridays in casehe is needed. He reviews the journalsof his UTAs and randomly samplessome of the journals that class memberskeep. He posts all of his lecture notesand PowerPoint presentations on aWeb site devoted to BIOS 101 and sayshe “destroys class notes at the end ofevery semester” to ensure that his mate-rial is fresh and timely.

After fine-tuning the course duringthe Lumina grant period, Bender be-lieves the design could have applicationon other campuses and in other aca-demic disciplines. Out-of-state col-leagues already are using the geneticsliteracy survey that he developed to as-sess students’ knowledge at the begin-ning and end of each semester. Thissurvey is one way that he has evaluatedthe success of the revamped geneticscourse. Some of the outcomes have sur-prised him. “I didn’t expect to havesuch a profound effect on those stu-dents who profiled with the weakestscience background,” he says.

If there is a factor in the success ofBender’s redesigned class that cannot bemeasured, it’s Bender himself. He’s acharismatic teacher who, as a workingclinical geneticist, has always used ex-amples from his active practice to addrelevance to his classroom lectures.During the grant period, he stepped upefforts to make lectures engaging bybringing in guest speakers and usingelectronic “clickers” that allow studentsto weigh in on controversial issues –cloning, stem-cell research, evolution –by “voting” with remote hand-held de-vices. “It takes about three minutes topoll a class,” he says. “It’s a little time-consuming, but you can get some inter-esting data that engender goodconversation.”

To further break down barriers withstudents who fear science, Bender initi-ated a Summer Start workshop as partof Notre Dame’s Balfour-HesburghScholars Program, a voluntary enrich-ment experience aimed at incoming mi-nority freshmen. Bender’s workshopculminates with “the Great Balfour De-bate” that has students discussing anemotionally charged topic. One such

2 5 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

debate centered on intellectual differ-ences between men and women, a dis-cussion that one student described inher journal as “the most interestingclass I have ever attended. I couldn’tbelieve the amount of participation!”

Among the positive outcomes of theredesigned gateway class and SummerStart workshop were:

Students with lower SAT scores showed dramatic and sustained im-provement in science literacy. On average, 248 of the 250 enrolled students completed BIOS 101 each semester.Fourteen non-science majors declaredtheir majors either as biology or pre-professional studies.The small discussion groups earned student evaluations in the top quartilefor entry-level science courses.All participating post-doctoral men-tors obtained teaching positions and indicated plans to develop course sequences modeled after the redesignedgenetics course.More than half of the participants in three Summer Start science workshopssuccessfully enrolled in BIOS 101;two have become UTAs after com-pleting the course. Enrollment in Bender’s classes, an in-

dicator of popularity among students,did not change as a result of the newdesign. He has always attracted capac-ity enrollment and continues to do so.Before he agreed to teach freshman-level genetics 10 years ago, typical en-rollment was about 30 students. Nowhe caps the number at 250 because thelecture hall has 250 seats. At best, theLumina grant prompted him to be moreintentional about several practices thathe has always followed in a casual way.This includes his recognition of thevalue of small-group discussions. Foryears he has made himself available tostudents during off-duty hours.

“Our students can requisition me,” hesays of his ongoing willingness to meetclass members on their turf. Then headds a caveat: The students first mustagree on a specific topic for discussionbefore they invite him for an informalget-together. “I’m not going to visit thedorm the night before an exam just toreview old test questions.”

As longtime director of Ball State University’s FreshmanConnections – a learning community experience aimed at first-year students – Paul Ranieri was well aware of the program’smissing piece. He also saw the irony of the omission. Ball State,nationally known for preparing students for teaching careers,did not provide for faculty to hone their teaching skills as partof its freshman-retention program.

“Many faculty members haven’t seriously studied pedagogy,”says Ranieri, a professor of English. “They’ve been in the class-room a number of years, are experts in their fields, but theydon’t have a lot of back-ground in teaching 18-and 19-year-old stu-dents.” To help meet theuniversity’s goal of in-creasing its 76 percentfreshman-to-sophomoreretention rate to 80 per-cent, Ranieri proposedusing Lumina funds toimplement an intensivesummer workshop pro-gram that, if successful,would improve teachingtechniques in severalcore curriculum courses.

Participation in thethree-year program waslimited to 12 facultymembers – an average offour professors each sum-mer – who represent a range of disciplines and collectivelyteach from one-third to one-half of the university’s freshmanclass every fall. Ranieri served as facilitator, assigning readingsand leading discussions about teaching techniques and learningstyles. To gain admission to the workshop, each faculty membersubmitted a description of a specific classroom problem and so-licited the group’s guidance in solving it. Through conversationand research, the participants then redesigned their classes toaddress the challenges they had identified. They field-testedtheir new designs in the fall and shared results with their col-leagues at meetings throughout the year. As an example:

Teaching the teachers

Faculty development was at the heart Indiana University Purdue University achieving a similar goal: to transform

”During the [Lumina] experiment’s first twoyears, the failure rate

has decreased to 8 percent, and the ‘A’s have tripled to 38 percent. We’ve

seen the most positiveeffect in the most at-risk students.”

Bill Magrath

2 7 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

“From 1999 through 2002, nearly 25 percent of first-semesterfreshmen were failing a core curriculum course, ‘World Mythol-ogy,’ and only 13 percent were achieving an ‘A,’” reports BillMagrath of the modern languages and classics department and aparticipant in the summer workshop. “We selected a set of in-struments for early detection of student performance levels;subsequently, students were assigned to specialized group work.During the [Lumina] experiment’s first two years, the failure ratehas decreased to 8 percent, and the ‘A’s have tripled to 38 percent.We’ve seen the most positive effect in the most at-risk students.”

Ranieri and his team are committed to comparing successrates of students in courses taught by project and non-projectfaculty, as well as tracking the graduation rates of project andnon-project students. The program already has earned highmarks from participating faculty who say they have benefitedfrom working alongside colleagues from disciplines other thantheir own. “The strength of this program is stepping out of ourfields and gaining different perspectives,” says Dave Concep-ción, assistant professor of philosophy, who is pleased with stu-dents’ progress in his redesigned introductory course. “Thispedagogy is beginning to show results,” he says. “My studentsare outperforming their peers.”

Concepción and his colleagues credit the professional devel-opment program with breaking down barriers within Ball State’ssprawling academic community with its more than 900 facultymembers housed in more than 50 buildings. “We need more ofthis multidisciplinary engagement,” says German Cruz, a mem-ber of the landscape architecture faculty. “My ‘cave’ is Room 229in the architectural building. That’s where I do the Plato thingby myself. But now I know that other people in other depart-ments are trying to do some of the same things that I’m tryingto do. My world is larger; I feel I’m connected.”

Exploring diversity across the curriculumAt Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis

(IUPUI), faculty members teaching freshman learning-communitycourses took a more tightly focused approach than their peersat Ball State. They used a portion of the grant funds to create afaculty learning community to explore ways to provide multi-cultural content in the curriculum. “If you have faculty thinkinghard about inclusive teaching, students feel more welcome,”says Anastasia Morrone, the project leader and now executive

director of the Center for Teaching and Learning.Faculty in classes ranging from introductory economics to

nursing education discussed classroom diversity issues andworked with facilitators and each other to broaden the curricu-lum and incorporate new teaching methods.

Although the number of minority students affected duringthe grant period was small, anecdotal evidence suggests thecourse transformations made a difference. Minority studentswere retained at a rate exceeding 80 percent. In the last year ofthe project, 2004-2005, students completed a questionnaire,and 35 of the 44 participants said the transformed courses had apositive impact on their perspectives of diversity. A sampling ofstudent comments includes:

“We must learn how to accept differences of all kinds, no matter what, and still supply everyone with the same humane care they deserve.”“This course really opened my eyes to diversity being more than just race and economic status.”“By showing diversity you begin to introduce the different ideas that will be present in the global market and how we (as engineers) must accept this as normal.”The revised curriculum also elicited positive comments from

faculty who said the experience broadened their perspective ondiversity, brought attention to diverse learning styles and in-structional methods, influenced their views on teaching diversepopulations and provided insights into how to use content andinstructional methods related to diversity.

“I realized that, while I started out teaching English, I evolvedinto teaching students,” says Terrence Daley, an English depart-ment lecturer and faculty learning-community participant.

Janet Meyer, freshman engineering adviser and Daley’s col-league in the faculty learning community, emphasizes the im-portance of listening to students. “You cannot begin a dialogue,much less communicate, if you are doing all the talking,” she says.

IUPUI extended its reach to other faculty on campus by de-veloping a Web site focused on multicultural education:www.opd.iupui.edu/diversity. The site contains materials such as amulticultural classroom resource guide; a multicultural teachingand learning module; an explanation of multicultural teachingtechniques; and a collection of faculty essays, including submis-sions by faculty who participated in the Lumina-sponsored fac-ulty learning communities.

of the Lumina-funded programs at Ball State University andIndianapolis (IUPUI). Each school chose a different approach to introductory courses to raise student success rates.

When the University of Southern Indiana (USI)set out to improve freshman-to-sophomore

retention rates, it focused on a tool most studentsconsider as vital as their cell phone: their computer.

School officials also beckoned another unlikelypartner: students’ parents.

The computer as a retention tool

Personalizing the collegeexperience one keystrokeat a time

2 9 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

With the help of a Lumina Founda-tion grant, teams of faculty and staffmembers worked with an outside firm –GoalQuest – to develop lessons thatwould help students make the transitionfrom high school to college. The lessonswere loaded into templates and sent tostudents’ e-mail addresses, and the stu-dents completed the work online.

The Evansville-based school also of-fered parents a separate set of lessonson how they could help their childrensucceed in college. Parents and studentshad access to links in each lesson to askquestions and get specific informationfrom university departments. Universityofficials pledged to respond to all com-ments and queries within 24 hours. Andstudents and parents alike had the oppor-tunity to complete “e-polls” at the end ofeach lesson and to make comments onhow things were going for the student.

“Early intervention is an important com-ponent to solving student problems asquickly as possible,” says Robert Parrent,USI’s vice president for student affairs.

Although all 2,000-plus freshmen re-ceived the e-mails, they could choosewhether to complete the suggested les-son. One-third to one-half of the stu-dents registered and participated in theprogram. Students who completed thelessons returned for their sophomoreyear in greater numbers than those whodidn’t – about 67 percent compared to65 percent in 2003 and 59 percent in2004. When their parents participatedwith them in the project, the retentionrates jumped significantly – to 78 per-cent in 2003 and 71 percent in 2004.

“When parents are involved, studentsdo better in class, have higher test scoresand higher graduation rates,” Parrentsays. “This program informs interestedparents and lets them be partners with-out getting in the way of their students.”

About 40 percent of USI’s 10,000students are the first in their family toattend college, so the information con-tained in the e-mails is key to helpingtheir parents understand their child’scollege experience. “There’s a high levelof intimidation – some of these parentsmight not even understand what amidterm exam is,” Parrent says.

Parents – and students – were grate-ful for access to information. One USI

parent wrote: “I was on the verge ofpulling my son out of school. Making iteasy for me to get in touch with theright person who could help me helpmy son was instrumental in keeping himin school. I can’t thank you enough.”

Lisa Johnson, mom of Jaclyn andJamie Johnson, says the informationcovered a broad range of relevant top-ics. "We were able to find answers to alot of general questions, and the sitealso addressed many of the freshmanfears," she says. Jaclyn, a freshman ele-mentary education major, and Jamie, asophomore pre-med major, are follow-ing in their mother's footsteps: LisaJohnson also graduated from USI witha nursing degree.

High-tech program creates“high-touch” experienceOne of the reasons for the project’s suc-cess: It was designed to enhance com-munication with students and parents –not substitute for personal communica-tion. GoalQuest, a company specializ-ing in Web-based tools that helpcolleges interact with students and par-ents, monitored participation in the les-sons and prepared index and trendreports for the university. It also gath-ered information through its e-polls.University officials received alerts aboutstudents who were homesick or havingother difficulties adjusting to college

life, and the officials would call thestudents to talk or invite them to lunch.

“We make contact with these stu-dents and say, ‘Congratulations –you’ve been selected to have lunch witha vice president today.’ And we’d justhave a conversation with the student tofind out how it’s going,” says Parrent.

The first year USI used the program,called Project e-AGLE (Electronic Ad-vice for a Great Learning Experience),John Deem, associate vice president of Student Affairs, worked withGoalQuest and an “editorial board” offaculty and staff members to developthe lessons. Topics included time man-agement, working with faculty, gettingto know the community, developinggood study skills, and choosing a major.“We wanted to introduce students touniversity life and help them with thetransition,” Deem says.

Lessons for parents included topicssuch as campus safety, student privacy,first-semester dynamics and freshmanfinancial issues. The editorial board up-dates the lessons each year, and Deemensures that the people on campus re-ceiving e-mail queries understand thatfollow-up must occur within 24 hours.

Students and parents first used theprogram in 2003. That year they beganreceiving e-mail lessons about twoweeks after the first semester began.The next year, and each year thereafter,USI started sending the lessons two tothree weeks before the fall semesterbegan and sent a new lesson every fiveto 10 days. In addition, the school peri-odically sent “live alerts” to parents. Forexample, an alert might tell them whenmidterm exams are scheduled (and sug-gest that they send cookies).

For the 2006-07 academic year, USIis once again experimenting to see if itcan further enhance student success.Project e-AGLE is continuing for allfreshmen, but for a small subset of thefreshman class (about 200-250 stu-dents), the lessons are required as partof their coursework in certain classes.Faculty who teach English, math, chem-istry and other freshman classes workwith GoalQuest to embed the lessonsinto the course curriculum. “We want tosee if these students can be retained atan even higher level,” Parrent says.

3 0 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

“When parents are involved,

students do betterin class, have

higher test scoresand higher gradu-

ation rates.”

Robert Parrent

Web-based portfolios prove tobe an ineffective retention tool

Indiana State University also experi-mented with using computers to helpimprove retention by using a LuminaFoundation grant to develop and testthe usefulness of Web-based portfolios.

The first year, 192 students took partin the program using a Microsoft Front-Page template developed in-house. Thetemplate offered students the opportu-nity to establish their learning goals,create resumes and post other reflec-tions. Many of the participants werealso in freshman learning communities,and the faculty members teaching thoseclasses gave students different assign-ments related to the portfolio. For in-stance, one assignment asked studentsto take a picture of their typical studyplace and write an essay about the po-tential distractions. The goal was to getthe student to think about the bestplace to study.

“Our expectation was that a more re-flective student would be a better stu-dent,” says Robert Guell, coordinator ofFirst Year Programs at Indiana StateUniversity. Based in Terre Haute, ISUhas a total student enrollment of about10,500. Nearly all of the 8,000 studentswho attend classes on campus are rightout of high school, and about 40 per-cent come from families where neitherparent has attended college. When ISUtested the portfolio program in 2002and 2003, about 70 percent of freshmenreturned for their sophomore year, andISU wanted to see if the portfolio expe-rience would increase that success rate.

The first year was plagued with soft-ware issues. Students and faculty alikehad difficulty learning FrontPage, andclass time was taken up with teachingthe software rather than teachingcourse content. “The faculty soured onthe idea fairly quickly,” Guell says.

The second year, the university usedan outside source, Nuventive, for aportfolio program called iWebfolio.However, this program proved restrictiveor difficult for users, Guell says. About 400students used this version of the portfolio,but results were no better. In fact,Guell says, in the College of Business,students so disliked working with theportfolio that they stopped attending

class at rates higher than the schoolhad ever seen before. In addition, theportfolios did not have a positive im-pact on retention or first-semestergrades, Guell says.

After two years of testing the portfo-lios as a way to improve student suc-cess, Guell says he’s changed his viewon the usefulness of reflection in 18-and 19-year-old students. “Reflection islike broccoli to the 5-year-old. No mat-ter how much cheese sauce you put onit, it’s still broccoli,” he says, noting thatstudents simply didn’t want to do theportfolio work.

“Good intentions are not enough,” he says. “Even when you have the bestpeople working very hard on a badidea, it’s still a bad idea.”

The redeeming factor of this grant,however, was that it clearly revealed, in a well-documented empirical study,that student portfolios did not improveretention. That find, while disappoint-ing to some, is instructive to the univer-sity and to funders of student retentionprograms. The conclusion of this exper-iment can lead to a more productivedeployment of retention resources inthe future.

3 1 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

Lisa Johnson used the Web-based initiative Project e-AGLE to stay informedas her daughters, Jaclyn (left) and Jamie, made the transition to college atthe University of Southern Indiana.

Indiana University Bloomington (IUB) has offered

classes with service-learning components for years,

but not until 2002 did it test the hunch that community

involvement can boost persistence among underrepre-

sented students. IUB used its Lumina grant to expand the

number of service-learning classes, recruit at-risk stu-

dents to fill middle-management positions within the

program, and create incentives for faculty to build com-

munity-service requirements into courses that typically

enroll high numbers of the targeted population.

Exploring the ‘Cheers’ effect

Linking service learningand persistence

3 3 L U M I N A F O U N D A T I O N L E S S O N S S P R I N G 2 0 0 7

Early results confirm the accuracy ofthe hunch. Minority and low-incomeparticipants in IUB’s Community Out-reach and Partnerships in Service-Learningprogram (COPSL) were 10 percent to15 percent more likely to persist to-ward graduation than minority andlow-income peers who did not partici-pate. “Across the board, these studentswere retained at rates greater than non-COPSL students,” says Todd Schmitz,executive director of university report-ing and research. “Targeted groups areclearly benefiting from the courses.”