Out and About: Photography, Topography and Historical Imagination

Transcript of Out and About: Photography, Topography and Historical Imagination

8

Out and About: Photography, Topography, and Historical Imagination

Elizabeth EdwardsDe Montfort University, Leicester

Setting the SceneHistory begins with bodies and artefacts, living brains, fossils, texts and buildings . . . The bigger the material mass, the more easily it entraps us . . . [they] bring history closer while they make us feel small. A castle, a fort, D�EDWWOH¿HOG��D�FKXUFK��DOO�WKHVH�WKLQJV�ELJJHU�than we that infuse with the reality the past lives, seem to speak with an immensity of which we know little except that we are part of it. Too solid to be unmarked, too conspicuous to be candid they embody the ambiguities of history.

—Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History

0LFKHO�5ROSK�7URXLOORW¶V�GHVFULSWLRQ�RI�WKH�DPELJXRXV�PDVV�RI�KLVWRUL-cal experience—a network of bodies, brains, and things over time and space—provides us with a useful entrée to this discussion of the affec-tive nature of photographic encounters with the material topographies of the past. In this chapter, I am going to consider ways in which late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century amateur photographers, who keenly engaged with the perceived subjective and objective modes of

177

178 Double Exposure

visualizing history, experienced spaces of local histories. In particular, I am going to consider the embodied mnemonic practices entangled in the photographic excursion or photographic ramble, which were orga-nized by photographic clubs and societies across the country. These summer meetings were mainstays of photographic sociability and con-stituted a key site for the transmission of values around both photogra-phy and a sense of the past for amateur photographers.

From this grounded ethnographic account, I hope we can extrapolate ways in which to think about embodiment, historical imagination, and visualization as a mnemonic practice. It is a process in which memory or, more precisely, perhaps the making of intentional and unintentional histori-cal statements reveals the processual nature of photographs and memory making through the experience of photographic practices themselves. Central to my argument is that historical imagination and its photographic translation emerged from a profoundly embodied experience of place, marked by movement through time and space. This cannot be reduced to the abstract space of an objectifying and appropriative gaze of landscape. I shall argue that space is rendered not as a mere container of action, but is instead the medium for a deeply humanized experience (Tilley 1984, 8, 10). My phenomenologically inclined approach therefore attempts more broadly to rescue landscape and historical topography from structures of objective/subjective dichotomies and link it instead to emotion and activity in a way that connects bodies, movement, ideas of locality, and historical imagination as a “lived material experience” (Tilley 2004, 24).1

There is substantial literature on the relationship between historical WRSRJUDSK\��PHPRU\��DQG�LGHQWLW\��ZKLFK�,�FDQ�RQO\�VXPPDUL]H�EULHÀ\�here. Particularly pertinent is the process through which landscapes become potent mediums of socialization and the production of knowledge. They are constituted through a socially produced space that combines the cognitive, physical, and emotional into something that can be reproduced culturally and, in this case, photographically (Tilley 1984, 10). Historical landscape as a mnemonic form is thus, as Tilley puts it,

experienced through life-activity, a sacred, symbolic and mythic space replete with social meanings wrapped around buildings, objects and features of local topography, providing reference points and planes of emotional orientation for human attachment and involvement. Places in existential space are foci for the production of meaning, LQWHQWLRQ�DQG�SXUSRVH�RI�VRFLHWDO�VLJQL¿FDQFH���7LOOH\���������±���

Similarly, Bender has argued that landscapes are cultural objects through which time is materialized, marked by a sense of time passing,

Out and About 179

both historical and mythical. As such, landscapes are profoundly imbri-cated with social and political relations, but ones that must at the same time be understood as “recognis[ing] the untidiness and contradictori-ness of human encounters with time and landscape” (Bender 2002, 103–4, 106).

There is also sizable literature on the embodiment of vision and visual technologies of the body, notably the work of Jonathan Crary, who DUJXHV��VLJQL¿FDQWO\�KHUH��IRU�WKH�HPHUJHQFH�RI�WKH�SURGXFWLYH�ERG\�LQ�WKH�nineteenth century (Crary 1990). While drawing on the general shape of these arguments, my approach owes more, in particular, to the work of Ingold and Tilley and to anthropological approaches to body, place, and H[SHULHQFH��7KLV�ZRUN�KDV�FRPELQHG�%RXUGLHX¶V�QRWLRQ�RI�habitus as a cultural disposition, with the philosophy of Merleau-Ponty and Husserl in particular, and its contemporary applications to ideas of space and place such as the work of Edward Casey. These arguments position the experi-ential world in which memory is inscribed and incorporated into habitual action, as centered on and sedimented in the body and to be “generative principle of social practice in interaction with the world” (Low and Hsu 2007, 59; Connerton 1989, 102).2

Another methodological concern, which is key here, is the way in which photography has been understood almost exclusively as a visual system, rather than as a complex and embodied cultural process of ZKLFK�WKH�SKRWRJUDSKV�WKHPVHOYHV�DUH�RQO\�WKH�¿QDO�RXWFRPH��$V�3LQ-ney has discussed, the “decarnalization” of the analysis of objects has resulted from the privileging of their visual and linguistic translation, rather than the materiality of the thing itself (Pinney 2003, 82). This implied disembodiment of the photographic process and photographs themselves is part, of course, of a wider cultural tradition of the dis-embodiment of knowledge itself (Shapin and Lawrence 1998, 1–2). While work of scholars such as Bal, Mitchell, and myself (elsewhere) have pointed to the “impurity” of the visual, its sensorially “braided” qualities and its materiality, there has been a tendency to overlook the multisensory qualities of image production (Bal 2003; Mitchell 2005; Edwards 2008a). As a result, analysis has considered only the visual image itself, placed in historical and ideological contexts, rather than looking at the generative act of photography itself, the social and cultural processes and actions, the result of which is a photograph. It is necessary, therefore, in relation to photography and photographs, to challenge the strange disjunction or disembodiment, which has occurred between the corporeal process of making a photograph and

180 Double Exposure

the intellectual product; that is, a photograph saturated with discursive, semiotic, and instrumental character with which we are so familiar from photographic theory.3

$�¿QDO� SUHOLPLQDU\��0\� DUJXPHQW� SRVLWLRQV� KLVWRULFDO� LPDJLQDWLRQ�as an integral and constituent strand of memory practices. So while my study might be said to fall within the overall rubric of the latter, I prefer to use the term “historical imagination” because, as will become clear, the uses of photography that engage us here are not only a naturalized ambience of a sense of the past, but self-conscious and imaginative acts of inscription in response to the corporeally experienced material traces of the past. It is a practice in which memorializing desire constitutes a strong subtext to the organizing of historical, archaeological, and eth-nographic knowledge. This is to the extent that such knowledge forms a set of clearly articulated mechanisms through which people situated themselves in time and space and negotiated the translation of this situated sense into photographs. I suggest that this sense of a connec-tion to the past through photographic activity, as makers and viewers, FRQVWLWXWHV�D�VLJQL¿FDQW�HOHPHQW�LQ�ODUJHU�PHPRU\�SUDFWLFHV�DW�WKLV�GDWH�(Edwards 2013).

I came to this way of thinking with photographs from the images them-selves, not as individual images but as sequences, narratives, and series, which intersected with the recurrent accounts of photographic excursions LQ�WKH�SKRWRJUDSKLF�SUHVV��:RUNLQJ�RQ�WKH�VXUYH\�SKRWRJUDSKHUV¶�DUFKLYHV��scattered across England, what I found remarkable was the enormous sense of the presence of the photographer as spatially embodied. They were photographs in which the body of the photographer had become a residue in the image, in which “the image is affected as much by the body behind the camera as those before it” (MacDougall 2006, 26–7). Thinking VHULDOO\�ZLWK�WKHVH�SKRWRJUDSKV��WKURXJK�DUFKLYDO�RUGHUV�DQG�QHJDWLYHV¶�numbers, revealed the walking experiences and historical imaginings from which the photographs had emerged. Making photographs was, for these amateur photographers, a way of inhabiting landscape and historical topography and providing “particular settings for involvement and the creation of meanings” (Tilley 1984, 11).4

Imagining Local Topographies

Moving in or through a given place the body imprints its own emplaced past into its present experience, its local history is literally a history of locales. This very importa-WLRQ�RI�SDVW�SODFHV�RFFXUV�VLPXOWDQHRXVO\�ZLWK�WKH�ERG\¶V�RQJRLQJ�HVWDEOLVKPHQW�RI�directionality, level and distance. (Casey, quoted in Feld 1996, 93)

Out and About 181

I am particularly interested in the act of photography because the existence of the photographs implies a complex set of bodily relations with the camera, of course, but also with the environment. “The lived body allows us to know what space, place and landscape are because it is the author of them all” (Tilley 2004, 3). I am arguing that these group outings RI�DPDWHXU�SKRWRJUDSKHUV�ZRUNLQJ�LQ�D�KLVWRULFDOO\�LQÀHFWHG�ODQGVFDSH�constitute just such a process. I am going to explore these excursions in particular in relation to movement, for the movement, as Casey has argued, not merely travels across space and time but “engage[s] us ineluctably in place.” Indeed unlike the photographic insistence, there is not completely static space, only place produced through movement (Casey 1993, 289). Consequently, the detailing modes of transport through the landscape

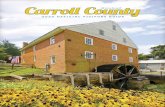

Figure 8.1. “Mr Fowler and Mr Godfrey” on an excursion of the Warwickshire Photographic Survey, 1894. (Lantern Slide. Birmingham Library and Archive Services.)

182 Double Exposure

utilized trains, horse-drawn wagons, bicycles, and especially feet takes RQ�SDUWLFXODU�VLJQL¿FDQFH�DV�PRGHV�RI�PRYHPHQW�DQG�DSSUHKHQVLRQ�

Group excursions, as I have suggested, were common summer activities for photographic clubs and societies and for the photographic sections of historical and antiquarian societies.

Their duration varied depending on distance to be traveled and the range of opportunities for members. The Birmingham Photographic Society, for example, alternated whole-day and half-day excursions at fortnightly intervals over the summer months.5 The form of excursions, DQG�LQGHHG�WKHLU�ODQJXDJH��LV�SDUW�RI�D�ZLGHU�¿HOG�WUDGLWLRQ�LQ�DPDWHXU�natural history and archaeological studies. These activities were premised on the demonstration and learning of technical and observational skills and also on a profound sense of sociability, as people came together, at OHDVW�LQ�WKH�FRQWH[WV�RI�SKRWRJUDSK\��WR�IXUWKHU�WKHLU�VFLHQWL¿F�DQG�DHVWKHWLF�endeavors and to enjoy the social company of those with similar interests.

Considerable effort was expended in the organization of excursions, the larger photographic societies such as Birmingham having special

Figure 8.2. After tea. An excursion of the Gloucestershire Antiquarian Society and SKRWRJUDSKHUV�WR�.LQJ¶V�/RGJH�/RQJ�0DUVWRQ��3KRWRJUDSKHG�E\�)��)��7XFNHWW�F��������(Gloucester Archives SR44/36297/13.)

Out and About 183

subcommittees for the purpose. A destination was advertised in advance, and an itinerary laid out, which represented a combination of photographic �DFWLYLW\�� SLFWXUHVTXH� DQG� VFLHQWL¿F� LQWHUHVW�� DQG� VRFLDELOLW\��5DLOZD\�timetables were consulted, ponies and traps hired, permission for access negotiated with landowners where necessary, and arrangements made with local inns for refreshments. Indeed, an enormous amount of energy and time went into the catering arrangements and the consumption of food, and they are unfailingly noted in local reports of these events.

Sometimes excursions were held jointly with neighboring societies, expanding and consolidating the networks of amateur photographers, but RYHUDOO�WKH�DPELWLRQV�DQG�VFRSH�RI�H[FXUVLRQV�UHÀHFWHG��DQG�ZDV�UHVSRQ-sive to, the particular demographics of each society.

These events were referred to by several names. This range of lan-guage—excursions, expeditions, outings, outdoor meetings, rambles, and MDXQWV²SRLQWV�WR�WKH�ÀXLG�UHODWLRQV�EHWZHHQ�WKH�VHULRXV�DQG�WKH�OXGLF�DQG�the objective and subjective strategies, which characterized the experi-ence for photographers. The photographic press supported such activities in a number of ways. Not only did it cater for these broad historical and mnemonic interests by running a constant stream of general-interest articles on history, landscape, and bygones, it also suggested foci for photographic activity and gave practical information. For instance, in the early 1900s Amateur Photograph magazine carried a regular col-umn, illustrated with half-tone pictures, entitled: “Peripatetics: Practical Information for Photographic Rambles in Town and Country,” which presented an amalgam of historical information, cheap places to stay, and local darkroom facilities.

The “Reports from Societies” and “Society Meetings” sections in the photographic press and local newspapers are full of notices and accounts of such excursions and rambles across the country in the summer months; for instance, in one week alone in 1895, Amateur Photographer listed forthcoming excursions to Oxted (Croydon Camera Club), Birkenhead 3ULRU\��/LYHUSRRO�&DPHUD�&OXE���0LOOHU¶V�'DOH��2OGKDP�3KRWRJUDSKLF�Society), Richmond Park (Putney Photographic Society), Salford Priors (Birmingham Photographic Society), and Burnley (Darwen Photographic Society).6 In the winter, the local exhibition spaces of camera clubs ZHUH�¿OOHG�ZLWK�WKH�UHVXOWV�RI�WKHVH�HQGHDYRXUV��,QGHHG�H[KLELWLRQ�SUL]HV�were often offered for photographs taken on a particular excursion. For example, in 1886 the Birmingham Photographic Society offered a prize of ten shillings and sixpence for the best set of three photographs taken on an excursion to the beauty-spot of Dovedale in Derbyshire; in 1895 the

184 Double Exposure

%ULJKWRQ�&DPHUD�&OXE�RIIHUHG�³��FHUWL¿FDWHV�������IRU�WKH�EHVW�WZR�SULQWV�from an excursion to Bramber,” and Aston Photographic Society held a FRPSHWLWLRQ�IRU�SKRWRJUDSKV�WDNHQ�RQ�DQ�H[FXUVLRQ�WR�/LFK¿HOG�&DWKHGUDO�7

Reports of these events variously noted what was photographed, who was there, where they walked, where they ate, and the state of the weather. What is common to all, beneath the focus on photographic activity, is a SURIRXQG�VHQVH�RI�WKH�KLVWRULFDO�DQG�WKH�DHVWKHWLF�LQÀHFWHG�WKURXJK�WKH�spatial and the visceral. For instance, a photographic excursion of the Plymouth Photographic Society to Berry Pomeroy in Devon in June 1903, embedded itself in the historical object itself, “the party settled down to tea within the precincts of the castle itself, the site being, it was understood, that of the old chapel.”8

The destination for excursions almost invariably included topographies rich in the historical and affective. Thus excursions were linked to par-ticular aesthetic practices in the creation of subjective artistic practices of photographers and the ambitions of record-making photographers allied to the photographic survey movement, to whom I shall return. It could therefore be argued that such photographic activity constituted a “selec-tive tradition,” in that it legitimated certain forms of historical knowledge DQG�SUHVHUYHG�VSHFL¿F�DVSHFWV�RI�FXOWXUDO�KHULWDJH��:LOOLDPV������������+RZHYHU��LW�LV�VLJQL¿FDQW�WKDW�WKH�LGHD�RI�UDPEOLQJ��WDNLQJ�SOHDVXUH�LQ�WKH�landscape and its historical and mnemonic possibilities, became increas-ingly popular and open to an increasingly wide section of the public, aided by increasing mobility offered by the railway and then by bicycles.

The more elaborate photographic excursions, such as those offered as part of the annual Photographic Convention,9 were of course only avail-able to those who could afford them, thus patterning the attribution of KLVWRULFDO�VLJQL¿FDQFH�WR�VSHFL¿F�YLHZV�DQG�REMHFWV��7D\ORU��������%XW�excursions and rambles were not exclusively so. As photography as a hobby moved down the social scale and leisure time expanded, the idea of the excursion is found throughout a wide range of different group-ings. There are strong links between, for instance, photographic clubs and rambling. Hence the term “photographic ramble” emerges from and addresses an increasing cultural sense of the potential of mobility and the enlarged range of experience thus implied.

The character of the foci for excursions and rambles has resulted in much of the analysis to date, such as it is, explaining these activities through macro-models of national identity and collective memory on the one hand and picturesque aesthetics and nostalgia on the other, brought together in the concept of “patriotic picturesque” to provide a visual

Out and About 185

YRFDEXODU\� IRU� DQ� LGHRORJLFDOO\� VLJQL¿FDQW�PQHPRQLF� SUDFWLFH�10 But these practices also functioned as a palimpsest of structures of mnemonic feeling in the production of historical topographies. Many excursions ZHUH� IRFXVHG�QRW�RQO\�RQ�KLVWRULFDO� WRSRJUDSKLHV�EXW�DOVR�VSHFL¿FDOO\�on questions of local history and local landscape and were led by local historians and antiquarians. These excursions consequently constituted mnemonic practices, which were also concerned with a sense of intense localisms translated not through a disembodied gaze of the photographer, but through a profoundly experienced locality. In this, local knowledges about and experience of the past were continually privileged in ways in which, as David Matless has pointed out, the local, locality, and local knowledge are not merely a concern with ontological content (here the content of photographs alone), but constitute a discursive form the trace of which runs through my argument (Matless 1992, 464).11

The historical value, their choice of subjects and their photographic WUHDWPHQW��ZDV�RIWHQ� LQÀHFWHG�ZLWK�ZKDW�5LHJO�KDV�GHVFULEHG�DV�³DJH�value.” This “manifests itself . . . through visual perception and appeals directly to our emotions” (Reigl 1982, 33). A feeling of the local as senti-ment, attachment, and observation came together in the embodied experi-ence of the photographers, moving through the historical landscape and translating it into photographs. While this was replete with the sentimental and nostalgic, it was felt, embodied by the photographer.

This is well demonstrated by a contemplation framed by historical imagination published in the pages of the British Journal of Photography in 1900:

. . . across the mott that bounds our village, the proud towers of Windsor (never so proud as now!) soar above the tree tops, and in the immediate foreground the eye falls on the old house which includes some parts of the original mansion in which King -RKQ�VOHSW�WKH�QLJKW�EHIRUH�KH�VLJQHG�0DJQD�&KDUWD��$OPRVW�ZLWKLQ�VWRQH¶V�WKURZ�RI�this house lies a quiet mead on which he met the grim company of Barons who were to wring from an unwilling monarch some of the most cherished liberties of our race . . . these dates and scenes waft you back in imagination, it needs some very powerful agency—such as the prosaic-looking camera at your side—to recall you.12

Likewise a Birmingham Photographic Society excursion to Compton Wynyates in Warwickshire in 1891 is noted through a sense of historical density, with all the markers of a patriotic picturesque:

The house is romantically situated in a hollow to the south of Edge Hill, and is con-sidered one of the most interesting old houses in England. It is picturesque in the extreme, and the hall, which rises to the full height of the house with an open timbered

186 Double Exposure

roof, contains an immense slab cut from a single oak, now resting on trestles, which forms a dining table. . . . Many must have been the hair-breadth escapes which this old house, so full of hiding places, must have witnessed during the civil ways, when it was occupied alternately by Royalists and Parliamentarians.13

As is well-recognized, the processual nature of mnemonic prac-tices requires the concrete markers, which create patterns of connection (Tilley 2004, 217). Thus the photographic efforts of amateur photogra-SKHUV�PDSSHG�RXW�VSDFHV�RI�VLJQL¿FDQFH��FUHDWLQJ�SDWWHUQV�RI�FRQQHFWLRQ��as the examples quoted above suggest. For them, the historical topography created what Stoler has described as “an ecology of remains,” saturated with markers of the past, which could be objectively marked and recorded and subjectively felt (Stoler 2008, 203).

Out and About

I want to move on now to the mnemonic processes constituted through the embodied experience of photographers engaged in excursions and rambles. I want to look particularly at how ideas of historical topogra-phy, imagination, and their photographic translation were experienced and expressed through the movement of photographers in the histori-cally apprehended landscape and how their mundane procedures of unremarkable photographic acts gave shape to their photographs and the traces of that landscape. These are inevitably entangled with individual intentions and desires within the wider tropes of historical imagination that I have noted. However, they also constitute a collective statement of mnemonic practice, as these haptic engagements with the ecology of WKH�SDVW�DUH�DUWLFXODWHG�WKURXJK�VSHFL¿F�FRQ¿JXUDWLRQV�RI�SKRWRJUDSKLF�practice and style. Within this, discourses of history and locality were actually performed through the body of the photographer, as Tilley put it: “Movement between places involves their sequential experience, in their description of the production of a narrative, linking the body to place and events in place” (Tilley 2004, 26).7KH�PRVW�VLJQL¿FDQW�HQJDJHPHQW�ZLWK�KLVWRULFDO�WRSRJUDSK\�ZDV�WKDW�

of the photographer walking, carrying his or her camera equipment, mov-ing through the landscape, feet on the ground, legs moving, eyes seeing, and ears hearing. Such an excursion of the Birmingham Photographic 6RFLHW\�LQ�-XQH������SURPLVHG��³3OHDVDQW�ZDONV�DFURVV�WKH�¿HOGV��DORQJ�the banks of the River Avon—affording many opportunities for the use of WKH�FDPHUD´�ZKLOH�/LYHUSRRO�&DPHUD�&OXE¶V�RXWLQJ�WR�%XUWRQ��&KHVKLUH�involved, “A most enjoyable two-mile walk.”14 Comments such as these mark almost every account of a photographic excursion. Walking becomes

Out and About 187

the banal and unconsidered frame of photographic excursions, yet it is integral to the experience of them.

Walking can be understood as a form of style and use, a processing of V\PEROLF�YDOXHV��KHUH�VSHFL¿FDOO\�LQ�UHODWLRQ�WR�VXEMHFWLYH�FRQVWLWXWLRQ�of local historical imagination and mnemonic process expressed and experienced haptically. For the environment was felt, heard, smelt, and experienced cognitively and symbolically as men and women moved through the landscape, dealing with the technology of photography (Crary 2001; de Certeau 1984: 100; Lee and Ingold 2006, 78). This is made clear in an account of an excursion of the Woolwich Survey in May 1903, as LW�PRYHV�WKURXJK�SRLQWV�RI�KLVWRULFDO�VLJQL¿FDQFH�LQ�WKH�GDPS�DQG�PXG��a complex chronotopic moment of historical imagination and embodied experience, marked through walking in the rain:

Cameras were brought into action on entering Crown Wood, which was systemati-cally photographed as far as the Railway bridge, when rain which had been somewhat ¿WIXO�GXULQJ�WKH�HDUOLHU�SDUW�RI�WKH�DIWHUQRRQ��VHWWOHG�LQWR�D�SURQRXQFHG�GUL]]OH�DQG�out a stop to further photographic work. The party then retraced its steps through the thick clayey mud which the rain had caused, to Shooters Hill where they dispersed.15

This is not merely a visualization of the ÀkQHXU, moving disconnectedly through the spaces, gazing voyeuristically upon the fragmented spectacle and bricolage of modernity. Nor is it simply an opening up of the land-VFDSH�WR�WKH�YLHZHU¶V�JD]H��D�SRVLWLRQ�WKDW��DV�,�KDYH�VXJJHVWHG��HOLGHV�the experience of the photographer. Instead it has more in common with the way in which de Certeau separated out the experience of the voyeur from the experience of the walker. That latter experience is, he argued, the threshold where visibility begins (de Certeau 1984, 93). But unlike de &HUWHDX¶V�ZDONHU��WKDW�YLVLELOLW\�ZDV�VHOI�FRQVFLRXVO\�H[SUHVVHG�WKURXJK�experiencing, photographing, and above all feeling. This is suggested by Sir Benjamin Stone, instigator of the National Photographic Record Association (see Edwards and James 2006), who commented in a lantern lecture on Westminster Abbey to the East Worcestershire Camera Club in 1896, that the subject was “. . . of considerable interest to any freeborn Englishman and Englishwoman when they walked through the aisles of the abbey, pictured the different scenes that had occurred there at different times of our history” [added emphasis].16

Walking, it can be argued, therefore created “maximal presence” in the experience of landscape. As Eelco Runia has argued, “On the plane of the SUHVHQW�DUH�µFRPPRQ�SODFHV¶�LQ�WKH�VHQVH�WKDW�HYHU\RQH�FDQ�YLVLW�WKHP��that they lie open for examination, that they can be walked. But they are

188 Double Exposure

not empty but full, not shallow but deep, not dead but alive. They are the repositories of time—or perhaps even better, the places where history can get hold of you” (Runia quoting Vico 2006, 13). This visceral quality of walking was clearly related to historical imagination in the nineteenth century by the distinguished historian of that period, Mandell Creighton, in 1897: “It is possible for us, while taking our walks, to bring before ourselves a sympathetic picture of the life and efforts of our ancestors, who worked at the problems which we ourselves have to try and carry on a little further” (Creighton 1903, 297).

The corporeal experiences expressed in the accounts quoted above constitute an interweaving of weather forms and habitation as texturing a landscape, in the way that Ingold describes as a “tangle of life-lines that comprise the land” and “weaving the texture into the land” (Ingold 2007, s22, s33).17 As Naylor has argued, writing of late nineteenth-century antiquarians, such excursions were “not only a matter of study at the site of a monument but more general body culture that required movement through the landscape and all the rigours that that involved” (Naylor �����������7KLV�KDV�PXFK�LQ�FRPPRQ�ZLWK�0RUULV�%HUPDQ¶V�VXJJHVWLRQ�RI�“visceral or somatic history”—a history written by the body not the mind holding the pen. In this, not only is it the way in which “history is made and experienced in the body, but [it] requires the experiential engage-ment of the historian in the matter of history” (Berman 1989, 110–111; Csordas 1999, 184–185). Both these elements come together in the amateur excursion, for here places and landscapes were “created and experienced through mobility . . . and through the manner and sequence in which they are explored, sensed, approached and left . . . movement between places involves their sequential experience, in their description of the production of a narrative, linking the body to place and events in place.” Movement weaves places together (Tilley 2004, 26; de Certeau 1984, 97).

The mobility of the photographer is clear not only in rural contexts but also in the urban, and there were many excursions in urban spaces, especially around icons of national and local memory such as the great cathedrals. For an eye sensitized by the picturesque or historical discourse, the awareness of the potential for photographic inscription, and often engagement with the concepts of local civic pride, memory practice, and historical consciousness could bring to the streets of the greatest city an active historical imagination, which would recognize and record historical VLJQL¿FDQFH�ZKHUHYHU�LW�PLJKW�EH�IRXQG��.LUNVWDOO�$EEH\�LQ�/HHGV�LV�DQ�interesting example. Here ideas of historical topography, civic identity,

Out and About 189

community memory, and photography come together clearly. In 1888–89, the ruins of the great twelfth-century Cistercian abbey had been the focus RI�D�KLJK�SUR¿OH�FDPSDLJQ�E\�WKH�PXQLFLSDO�DXWKRULWLHV�WR�VDYH�LW�IRU�WKH�city (see Dellheim 1982, 102–110). The plight of Kirkstall stood for the importance of a sense of medieval continuity in the midst of the modern FLW\�RI�/HHGV��6LJQL¿FDQW�KHUH�LV�WKH�H[WHQW�WR�ZKLFK�LW�ZDV�UHSHDWHGO\�photographed by local photographers from the Leeds Camera Club.

The photographers moved through the spaces of the ruin in which the spatial exploration becomes a kind of claiming the space of history and thus a form of memory, as a claim to civic longevity and indeed local authority and legitimacy.

Another example is a series of photographs by T. K. Gordon, building surveyor of Nottingham Corporation, for the Nottinghamshire Survey. These photographs are arranged to create little narratives, interweaving of town space and people, the comings and goings of everyday urban life, in which there is a strong sense of Gordon himself as part of the space of the street.18�7KLV�LV�HVSHFLDOO\�FOHDU�LQ�*RUGRQ¶V�SHHSV�GRZQ�1RWWLQJKDP�alleyways.

There is a sense of a simultaneous opening out beyond the images, while the embodied photographer moves in a different trajectory. What LV�VLJQL¿FDQW��WRR��LV�*RUGRQ¶V�LQWHUHVW�LQ�WKH�ERXQGDU\�VSDFHV�RI�WKH�FLW\��Where does one set of historical possibilities end and another begin? In the nineteenth century, the edges of cities were spaces of continual UHGH¿QLWLRQ��OLPLQDO�VSDFHV�EHWZHHQ�ROG�DQG�QHZ�RUGHUV��RI�GLVDSSHDUDQFH�

Figures 8.3–8.4. Kirkstall Abbey, Leeds. Photographed by Godfrey Bingley.(NPRA Collection, Victoria and Albert Museum London.)

190 Double Exposure

Figure 8.5. Nottingham streets. Photographed by T. K. Gordon c. 1895.(Nottinghamshire Archives, DD/1915/1/716.)

Out and About 191

and survival. But they were also potent spaces between perhaps the daily experience of many of the photographers, and the rural spaces of SLFWXUHVTXH� DQG�SDVWRUDO� LPDJLQDWLRQ��ZKLFK� LQÀHFW� VR�PXFK� DPDWHXU�photography. These photographs exemplify the way in which place is actively constituted through walking. Making the photographs performed “a distinctive relationship with place, the interaction of the walker and the meaningful environment” (Ingold 2007, 88–89). That is the creation of an historical topography through experience and mobility, creating multiple SRLQWV�RI�VLJQL¿FDQW�REVHUYDWLRQ�IURP�ZKLFK�NQRZOHGJH�LV�DFFXPXODWHG�

Such photographs are the result of walking with cameras, an embodied sense of technology as the camera becomes, in effect, a prosthetic eye and the creator of prosthetic memory through the photograph. Different camera technologies, however, demanded different forms of movement. If Gordon was able to move around Nottingham with a small handheld camera, larger cameras inhabited movement. In this, we see the agency of the object, prescribing and constraining actions and relationships (Gell 1998). For instance, C. J. Fowler from Birmingham commented on the UHODWLYH�SDXFLW\�RI�XUEDQ�YLHZV�EHFDXVH�RI�WKH�GLI¿FXOW\�RI�KDQGOLQJ�D�whole plate technology, requiring a tripod, in the busy city streets (Fowler 1897). While one does not wish to collapse into a technologically deter-mined argument, it remains that the relations between people and things in a network of possible movement structure ambiences in which human/thing relationships are shaped and mediated. Things, cameras, for instance, impose behaviors, experienced corporeally back on to humans through a process of “prescription” (Akrich 1992, 36), which translates into the ³HEEV�DQG�ÀRZV�RI�ZHLJKWV��UK\WKPV�DQG�VXUJHV�WKDW�������DUH�LQKHUHQW�LQ�the body and its movements” (Yudell 1977, 60).6LJQL¿FDQW��WRR��LV�WKH�ZD\�LQ�ZKLFK�SKRWRJUDSKHUV�ZRUNHG�LQ�DOO�VRUWV�

RI�FRQ¿JXUDWLRQV�RU�SDWWHUQV�RI�VRFLDO�FRQQHFWLRQ��$V�KDV�EHHQ�DUJXHG��place cannot be adequately understood without “considering its relation-ship with others and experiencing its situation in the landscape at a human scale requiring moving and walking” (Yudell 1977, 221). Such relations marked the experience of the act of photography itself as photographers moved through historical topography, in pairs, in informal groups, for-mal groups, or alone. There is social quality of both photographic prac-tice and historical apprehension. An example occurred at Woolwich in �����ZKHQ��³,W�ZDV�DUUDQJHG�WKDW�PHPEHUV�PHHW�DW�6W�-RKQV¶�6FKRROV�DW� 2:30 pm and Prince Imperial Statue Woolwich Common at 2:45. The party numbered seven, and the weather glorious.”19 There is a sense of the collective experience of the past and thus the formulation of a shared

192 Double Exposure

historical imagination of sites seen and photographically inscribed by individuals in a group.

The organization and reporting of excursions and rambles always stress this sense of the collective and the social, as a note on the Bristol Photo-JUDSKLF�6RFLHW\�SXW�LW��³7KH�LVRODWHG�ZRUNHU�FDQQRW�EXW�EHQH¿W�E\�WDNLQJ�part in such outings as these, and so rubbing brains with others of similar tastes.”20 And this was related to walking; for instance, it was reported of a Plymouth Photographic Society excursion to Totnes in Devon, “As the party wended its way along the top of the hill . . . from Totnes, across the river, and its meadows, came the sound of the curfew bell, tolling as it has been tolling century after century.”21

Organized excursions in particular marked the “relationship between practices of walking, the experience of embodiment and forms of sociability” (Lee and Ingold 2006, 67). As noted, excursions comprised an itinerary through the historical landscape, marking spots of selec-WLYH�VLJQL¿FDQFH�DQG�PQHPRQLF�VDOLHQF\��6RPHWLPHV�VNHWFK�PDSV�ZHUH�provided to guide photographers through historical spaces, as was the FDVH�LQ�/HHGV�3KRWRJUDSKLF�6RFLHW\¶V�H[FXUVLRQ�WR�<RUN�LQ������22 This intersection of sociability, movement, history, and photography is also demonstrated in the description of a photographic excursion to Colchester, Essex in 1906. To quote:

The party ascended Balkerne Hill, Dr. Laver [a noted local antiquarian] explaining the various points of interest associated with the building of the old Roman Wall . . . the Balkan Gate. . . was viewed with special interest . . . [being one of] the only two Roman archways of the kind remaining in England. Having viewed the old Roman *XDUG�URRP��WKH�FRPSDQ\�SURFHHGHG�WR�6W�0DU\¶V�VWHSV��ZKHUH�WKH\�LQVSHFWHG�WKH�remains of one of the towers built in the wall for defensive purposes by the Romans. 23

Similarly at Woolwich again:

Eltham being reached, the party separated & systematically photographed the High St & the immediate vicinity. Permission having been previously obtained to photograph the Palace . . . a visit was next made by the whole party. . . . The old Banqueting Hall exterior and interior residences were photographed. Whilst the party were busy here, Mr G. Tapp approached the lady owning the property known as The Moat, who gra-ciously allowed four of the party to photograph the house and private grounds from the Moat level. This was much appreciated, and proved to be one of the best features of the outing. It now being 7:30 pm, cameras were packed away . . . the party strolled KRPHZDUGV�WKURXJK�WKH�¿HOGV�DQG�:HOO�+DOO�5RDG��7KH�HYHQLQJ�EHLQJ�FRRO�E\�FRQWUDVW��QR�KXUU\�ZDV�PDGH��KRPH�EHLQJ�UHDFKHG�E\�WHQ�R¶FORFN��24

Such excursions therefore allowed not only the display of local his-torical knowledge but a collective corporeal education, literally moving

Out and About 193

through, and feeling connected to, the spaces of history, where perhaps “not a yard of the road traversed [is] uninteresting.”25 It indicates the way in which photographers felt and perceived historical topography, activated in the present, and thus how it might translate into photographs.

But while historical place was expressed through movement, the pho-tographs themselves, of course, represent moments of stillness, not only because of the nature of the photograph itself, but also the moment of observation or aesthetic apprehension, was made from stationery positions through the moment of “the view” (Ingold and Lee Vergubst 2008, 4). But as acts of historical imagination and fantasy suggest, as in the case of the historical reverie at Runneymede that I quoted earlier, the stillness of the photographic act merged into a stillness of contemplation and recollec-tion. The photographs translated this movement into stasis focusing on the unmoving object, while the movement of the photographer remains through seriality. This is demonstrated by Leeds photographer Godfrey %LQJOH\¶V� VHULHV� RI� WZHOYH� SKRWRJUDSKV� RI�6WRQHKHQJH� WDNHQ� LQ�$SULO�1892. Through the photographs, there is a clear sequence of movement in and around the great stones. It stresses, visually, their monumentality and, importantly, their texture. Bingley was a keen amateur geologist and photographer.26 He understood the translation of the quality and affect of stone on the photographic plate through the play of light on mass. %LQJOH\¶V�PRYHPHQW�DURXQG�WKH�VWRQHV�UHYHDOV�D�VKLIWLQJ�VHULHV�RI�ERGLO\�relations with the stones, subtly shifting their meaning and apprehension within patterns of movement (Tilley 2004, 222).

Even minor traces of movement indicate the act of photography; for instance, a series of six views of exterior of Morton Valance church in Gloucestershire taken by George Embery in about 1896 or George 6FDPHOO¶V� SKRWRJUDSKV� RI� WKH� LQWHULRU� RI�1RUWK�:DOVKDP� FKXUFK� LQ� Norfolk.

His camera placed in front of the altar and communion rails, he turned, pivoting, from the Easter sepulchre on the north wall to the sedilia of the south. Architecture, of course, “functions as a potential stimulus for movement, real or imagined” (Yudell 1977, 59) imposing prescriptive agentic demands on photographers. Photographs such as these not only embody the act of photography but are responsive to space at the level of practice. In the discourse of making architectural records in particular, such responses constituted enhanced values and enhanced observational practice; that photographers were urged to make “not only single views, but some of them [buildings] taken from a dozen positions, that preserved all their beauty”27 just as George Embery did.

194 Double Exposure

Figures 8.6–8.7. Stonehenge, Wiltshire. Photographed by Godfrey Bingley, 1892.(NPRA Collection, Victoria and Albert Museum London.)

Figure 8.8. Morton Valance Church. Photographed by George Embrey, 1903.(Gloucestershire Archives, SR44.36297.150.)

Out and About 195

3KRWRJUDSKV�VXFK�DV�WKHVH�H[HPSOLI\�7LOOH\¶V�FODLP�WKDW�³SODFHV�DQG�landscapes are created and experienced through mobility as much as stasis through the manner and sequence in which they are explored, sensed, approached and left” (Tilley 2004, 26). But the spaces between the image WUDFHV�DUH�QRW�PHDQLQJOHVV�EXW�¿OOHG�E\�WKH�ERG\�RI�WKH�SKRWRJUDSKHU��D�crucial part of the apprehension of the object.28 Thus one can argue that the photographs emerge not only from questions of subjectivity and objectiv-ity, of the exercise of historical imagination and mechanical translation through the photograph, but through alternating rhythms of movement and stillness articulated through the body of the photographer.

Following Light

Moving bodies structure a sense of place and thus imply the negotia-tion of meaningful alternative directions available at each important juncture (Casey 1993, 45). However, the movement of photographers in the landscape as a mnemonic process was contained by a crucial com-ponent in the embodied experience of photographers that puts all this discussion into a photographic context: that of light (the raw material of photography) and sight. The technical actions of light are commonplace in photography, in addition to what Jay has described as the metaphys-ics and mysticism of light being integral to thinking about vision and photography (Jay 1993, 29–30). It is necessary to explore the ways in which light intersects with the embodied experience of photographers,

Figures 8.9–8.10. North Walsham Church, Norfolk. Photographed by George Scamell. The Easter Sepulchre and the Sedilia. (NPRA Collection, Victoria and Albert Museum London.)

196 Double Exposure

historical imagination, and memory practice. For light, “the experience of inhabiting the world of the visible” becomes a form of social orchestra-tion of the experiential processes that I have claimed for photographers, mediating “between bodily sensation and matter” (Ingold 2000, 265; Bille and Flohr Sorensen 2007, 264). What above all dictated the move-ment through the historical landscape was light, for “light . . . is the ground of being out of which things coalesce—or from which they stand forth—as objects of attention” (Ingold 2000, 265).

Light was understood as integral to the recording of the past in the present as metaphor and practice; indeed the motto of Leeds Camera Club was “Lux absolutus est.”29 For example, in 1885, Harrison, a leading exponent of amateur survey photography and public education, published a paper in the Photographic News entitled, “Light as an Instrument for 5HFRUGLQJ� WKH�3DVW�´� ,Q� WKLV��+DUULVRQ�DUJXHG�� OLJKW��DV� LW� UHÀHFWHG�RII�the earth into the universe might carry with it, in a quasi-photographic IDVKLRQ��D�UHFRUG�RI�WKH�SODQHW¶V�KLVWRU\�LQ�WKH�JUHDWHVW�GHWDLO��/LJKW�ZDV�thus the very foundation of visualized all-embracing historical knowledge and one that at the same time could only be an act of expansive historical imagination. It is worth quoting at length:

It is a wonderful thought, that every action which has ever occurred on this sun-lit Earth of ours—or indeed, for that matter, anywhere within the illuminated universe—is recorded by the action of light, and is at this moment visible somewhere in space, if any eye could be there placed to receive the waves of light . . . speeding away from our orb, which would now be visible only as a star, we should pass in review the lives of our parents and ancestors. History would unfold itself to us. We should only have to continue the journey long enough to see Waterloo and Trafalgar fought out before our eyes; we should learn the truth as to the vaunted beauty of Mary Queen of Scots; and the exact landing place of Julius Caesar on the shores of Britain would no longer be a mystery. If we had the curiosity to ascertain by ocular demonstration, the truth RI�'DUZLQLDQ�WKHRU\��D�VWLOO�PRUH�H[WHQGHG�ÀLJKW�ZRXOG�GLVFORVH�WKH�PLVVLQJ�OLQNV²LI�such existed—by which man passed from an arboreal fruit-eating ape-like creature to a reasoning omnivore. (Harrison 1885, 23)

But we can also link light to movement because in order to realize the act of photography, photographers had, literally, to follow the light and ensure that their bodies and their equipment were positioned advan-tageously in relation to it. The relation between movement and stasis that I noted above is one dictated by light. Thus the availability of light and its qualities, which are of course related to weather and atmospheric conditions—some of which such as cloud and frost had aesthetic import as well—dictated precisely the way that photographers moved about, the way they saw it, and thus translated the historical landscape into

Out and About 197

photographs. Light was fundamental to the revelation of “people, places DQG�WKLQJV�LQ�FXOWXUDOO\�VSHFL¿F�ZD\V´��%LOOH�DQG�)ORKU�6RUHQVHQ�������������1RW�RQO\�FRXOG�ZDONLQJ�DQG�REVHUYDWLRQ�LGHQWLI\�WKH�VLJQL¿FDQFH�and most advantageous views of a building, but they were linked to local knowledge “for the complete success of these outings [excursions] it is necessary to have a leader who knows the ground well, so that the various points of interest may be visited at a time when the light is suit-able for each” (Harrison 1885, 23). Excursions and rambles were often SODQQHG�VSHFL¿FDOO\�WR�DUULYH�DW�ORFDWLRQV�LQ�RSWLPXP�OLJKW�FRQGLWLRQV��)RU� LQVWDQFH��/HHGV�3KRWRJUDSKLF�6RFLHW\¶V� ����� H[FXUVLRQ� WR�6HOE\� LQFOXGHG�WKH�1RUPDQ�DEEH\�DQG�YLHZV�RI�WKH�ROG�PDUNHW�WRZQ�VSHFL¿FDOO\�planned around the availability of light.30 Not only were precise times given, but the movement between spatial points was also a movement between temporal points, both as objects of the past and in relation to the regular passage of light in the course of a day.

This sense of following the light is most clearly demonstrated in a series of articles that appeared in Amateur Photographer and Photographic News IURP������HQWLWOHG�WKH�³$UFKLWHFWXUDO�3KRWRJUDSKHU¶V�&ORFN�´�ZKLFK�VHHPV�to owe some of its character to the earlier “Peripatetics” column I noted above. Under a banner line-drawing showing a clock, the passing of time, the object of historical and mnemonic desire—the ancient building—and a sun energetically dispersing its rays, the column merged astronomical calculation, linear time, historical imagination, local topography, and DHVWKHWLFV��7KH�³$UFKLWHFWXUDO�3KRWRJUDSKHU¶V�&ORFN´�UHSURGXFHG�D�SODQ�RI�DQ�KLVWRULF�EXLOGLQJ�VXFK�DV�/LFK¿HOG�&DWKHGUDO�RU�+DXJKPRQG�$EEH\�in Shropshire.

Not only did the column provide a potted history and architectural explanation, it guided photographers through the countryside on foot, bicycle, or railway to reach the photographic subject. Its main purpose, however, was to direct the movement of their bodies through space and time around the building.$�VHULHV�RI�YDQWDJH�SRLQWV��QXPEHUHG�DQG�OLQNHG�WR�VSHFL¿F�WLPHV�LQ�WKH�

GD\�LQ�WHPSRUDO�RUGHU��ZDV�DUUDQJHG�DURXQG�WKH�ÀRRU�SODQ�RI�WKH�EXLOG-ing. It showed photographers when and where to place their cameras for the optimum photographs through which to demonstrate the character-istics of the building. For instance, the cloister was to be photographed around noon, with a high sun, when its enclosed space had shorter, less obtrusive shadows, ensuring maximum visibility and thus legibility, whereas interior shots required a softer, less contrasting light. Thus the body of the photographer, carrying his or her equipment, was arranged in

198 Double Exposure

Figure 8.11. The Architectural Photographer’s Clock.$PDWHXU�3KRWRJUDSKHU���$XWKRU¶V�FROOHFWLRQ��

Out and About 199

UHODWLRQVKLS� WR� OLJKW� DQG� REMHFWV� DW� ¿IWHHQ�PLQXWH� LQWHUYDOV�� OLWHUDOO\� moving with time and light.$V�ZH�VDZ�LQ�UHODWLRQ�WR�%LQJOH\¶V�SKRWRJUDSKV�RI�6WRQHKHQJH��WKLV�

raises the question of movement and the exact process through which historical topography was perceived. Movement stressed the ways in which not all surfaces can ever be seen at once, and that to comprehend the object demands moving through and around its space, constituting changing sets of relationships, embodied relationships, as from different directions, and different sequences of directions the things encountered assume different shapes, sizes, and textures. This is exactly what is hap-pening here, but above all the movement of the body around the building is dictated by light.

Grids of History

However, there was a group of photographers for whom the walking KDG� WR� EH� SXUSRVHIXOO\� FRQ¿JXUHG�� DQG� WKHVH�ZHUH� WKH� DPDWHXUV� SKR-tographers involved in the survey movement. I have touched on them throughout this essay, but it is necessary to explore and contextualize their particular modes of walking. Emerging in the late nineteenth cen-tury, the photographic survey movement was a loosely cohered group of projects of mnemonic intensity, which shared the objective of har-nessing the energies of amateur photographers to record the material traces of the past—parish churches, old cottages, manor houses, market crosses, stocks, ancient yew trees, folk customs, traditional industries, and other curiosities—before they disappeared. Their focus had much in common with the more general amateur practices I have described thus far; indeed there was a considerable overlap between objectives—aes-thetics and practitioners on the one hand, and models of historical and PHPRULDOL]LQJ�VLJQL¿FDQFH�RQ�WKH�RWKHU�

Organized as sections of local photographic and camera societies or through the photographic sections of amateur antiquarian, archaeo-logical and natural history societies, who also had excursions to look DW�DQG�SKRWRJUDSK�DQWLTXLWLHV��WKLV�VHOI�LGHQWL¿HG�JURXSLQJ�RI�µVXUYH\�PRYHPHQW¶�ZDV� SDUW� RI� D� EURDGHU� FXOWXUDO�PDWUL[� SUHVHUYDWLRQ�� WKH� negotiation of the past in the present and concerns about the kind of past and present being bequeathed to the future (Edwards 2012, 9–10). But it was also closely related to the photographic excursion, either as an organized activity or as a self-regulated encounter with the histori-FDO� ODQGVFDSH��+RZHYHU�� WKH�TXDVL�VFLHQWL¿F�DVSLUDWLRQV�DQG�PHWKRGV�of survey photographers demanded more than just rambles.31 To realize

200 Double Exposure

their objectives, there was a need to control the subjectivities of the body. As such, vision itself was constituted as an embodied practice, not simply in the physiological sense, argued by Crary (1990), but as one that had to be contained and controlled through the management of the body in space, through which attention could be directed appropriately to produce the desired objects of history.

In order to control the entropic threat of disordered looking and thus memorialization, survey photographers were encouraged to base their visual mapping on the Ordnance Survey (OS) maps of their local area, the six-inch edition of which became available for each county during the 1880s. They were “the map for the work of photo-survey” (Harrison ���������DV�RQH�FRQWHPSRUDU\�SXW�LW��ZLWK�WKHLU�SUHFLVH�GHOLQHDWLRQ�RI�¿HOGV��tracks, boundaries, and buildings, delivered a “systematic” rendering of space, through which places were made correct, clear, and “unfuzzy” (Frake 1996, 245), and which could be traversed with directed attention, which itself would translate into “objective” photographs.

The employment of the six-inch OS map was not only empirical but discursive. By the nineteenth century, maps had become rational, realis-tic devices representing how things actually appear through their basis in trigonometry, photogrammetry, and the mathematical translation of landscape into a perfect “panopticon of record” (Gilbert 2002, 11). While the map constituted an authorizing control of landscape, it also consti-tuted “the sites of cultural negotiations in which competing perceptions and experiences of the landscape and its social history are manipulated” (Smith 2003, 72). For it was part of the process by which local historical topographies of burial mounds, Roman roads, and parish churches became LQVFULEHG�DV�QDWLRQDO�KHULWDJH��OLQNLQJ�GLIIHUHQW��DQG�VRPHWLPHV�FRQÀLFW-ing, narratives of the local, regional, national, and, at this date, imperial WKURXJK�WKH�SODFLQJ�RI�VSHFL¿F�KLVWRULFDO�ORFDWLRQV�LQ�ZLGHU�IUDPHZRUNV�of geographical space and to larger historical topographies.

The use of maps was intended to impose the system of an aspired-to scienticity onto the ambiguities of historical space and thus avoid “the frequently aimless wanderings after the picturesque which form a good part of some photographic excursions.”32 Some, for instance the surveys undertaken for Warwickshire, the Wirral, Essex, Nottinghamshire, Dorset, and Surrey, attempted a systematic coverage of the historical landscape by organizing recording work through cutting the map into either quarter- sheet or six-inch sections, a “convenient size for carrying in the pocket or camera case” (Gower, Jast, and Topley 1916, 177). These were given to photographers who were then expected to cover all items of historical

Out and About 201

interest within that grid. At the same time, the map controlled and located the precise position of the photographer, and the pattern of their observa-tion, within space:

It might be well if every record photographer noted latitude and longitude as accu-rately as possible, and the aspect or orientation of the camera. It is not always easy to ¿QG�WKH�DVSHFW�DFFXUDWHO\��EXW�DQ�DSSUR[LPDWLRQ�LV�SRVVLEOH�E\�WKH�XVH�RI�D�PDJQHWLF�compass. The large scale ordnance map will often do better service than the magnetic compass in this respect.33

But revealed in the discourse of survey are different kinds of walking DQG�WHQVLRQV��ZKLFK�FRXOG�EH�UHODWHG�WR�WKH�YDOXHV�RI�REVHUYDWLRQ��HI¿-ciency, and procedural correctness. Harrison encouraged photographers LQWHQGLQJ�VXUYH\�ZRUN�WR�YLVLW�SODFHV�¿UVW�ZLWKRXW�WKHLU�FDPHUDV��+DUULVRQ�1889, 513) in order to experience the sense of place and history, which would be translated into photographs. Camera as Historian, a vade mecum for survey photographers published in 1916, was even more explicit. Pho-tographers were encouraged to “lay out the work rather than undisciplined meandering around the landscape” (Gower, Jast, and Topley 1916, 177). :DONLQJ�KHUH�ZDV�¿UPO\�OLQNHG�WR�V\VWHP�UDWKHU�WKDQ�SRHWLFV��7KH\�JDYH�an example of a marked-up OS map to show not only the photographs to be taken but also the controlled movement of the body through that space.

The book continues: “Thoroughness of work is best attained by walk-ing our ground unencumbered by photographic impedimenta and noting on the map the views to be taken . . . This done the photographic outing is directed without loss of time to actual work and the result will be found a better series of records that could be obtained by casual unpre-meditated, and therefore less promiscuous plate exposure” (Gower, Jast, and Topley 1916, 177–178). This might be understood as constituting what Hansen has described, in relation to mountaineering, as a perfor-mative modernity (2001, 186–187), in which the relations between the past and modernity are experienced performatively through embodied actions, gestures, and symbols of order and photography itself. But it also points to a form of walking, which aimed to counter the entropic dangers of wasted energy, wasted observational opportunities, and wasted photographic endeavor.

This controlled walking was in its turn related to light. The processes of planned movement, which I described earlier, were framed through the rational graticule of the map and existed in a recursive relationship ZLWK�OLJKW��)RU�WKH�GHWDLO�RI�WKH�VL[�LQFK�26�PDS�DOORZHG�³HYHU\�¿HOG�DQG�every tree, to be depicted. The orientation of buildings is clearly shown

202 Double Exposure

Figure 8.12. Photographic survey using the Ordnance Survey Map.&DPHUD�DV�+LVWRULDQ���$XWKRU¶V�FROOHFWLRQ��

Out and About 203

so that the photographer can see beforehand when the light will fall on any building, ruin, etc.” (Harrison 1889, 512, added emphasis), so that the photographer can account for the changing effects of light on the EXLOGLQJ¶V�VXUIDFH�34

The OS map not only controlled observation but the movement of the photographer through the landscape. At the same time, walking is linked to imagination, for the OS maps with their delineations of roads, tracks, and footpaths map enable the act of walking and engagement to be imagined and anticipated (Frake 1996, 244). Thus perhaps the map was inadequate control for meandering and thus subjectivity of the pho-tographers. The mathematized space represented through the OS maps creates a site of tension between objective renderings of space, which might form the prosthetic memory of the archive and the memorially LQÀHFWHG�H[SHULHQFH�RI�SODFH��7KLV�LV�H[HPSOL¿HG�E\�WKUHH�:DUZLFNVKLUH�Survey photographers—William Greatbatch, Bernard Moore, and Percy Deakin—who undertook a photographic excursion over the Easter week-end of 1896, cycling and walking through the landscape with a map. They left a small diary of this outing, which shows how their survey endeavours are repeatedly, almost overwhelmingly, punctuated by embodied experi-ence of that space and its relation to historical imagination, recollection, and the picturesque as they walked and cycled across the Warwickshire countryside carrying their maps. For instance at Edge Hill, they stood—a moment of stillness—and I quote, “We imagined the Royalists charging down the hill-side & rounding the little woods and copses.”35

Some Closing Thoughts

I confront the city with my body, my legs measure the length of the arcade and the width of the square; my gaze unconsciously projects my body on the façade of the cathedral, where it roams over the mouldings and contours, sensing the size of the recesses and projections. My body weight meets the mass of the cathedral door and my hand grips the door pull as I enter the dark void behind (Pallasmaa 2005, 40).

The manner in which objects are experienced depends of the structure of encounter, their perception, and their affective mnemonic nature. The mobile acts of photographic narrating, which I have described, open up the experience of the material traces of the past in multiple ways. Land-scapes have enormous ontological import as lived-in and mediated spaces, replete with meaning (Tilley 2004, 25). I have argued here that it was the embodied experience of photographers in the historical landscape, rather than simply disembodied gaze, that produced and performed a sense of

204 Double Exposure

the past, anchored also in concepts of place and locality, and the kinds of knowledge that might be drawn from them. It constitutes a thick descrip-tion of place and how one encounters, feels, sees, and senses that places are all informed by memory—an understanding that these are places that have been previously encountered and experienced, an affective engage-ment with “people who once occupied the space we do now” (Tilley 2004, 220; Zerubavel 2003, 42).

The act of photography, and thus the resulting photographs, were con-stituted through embodied sets of relations among places, people, and a structure of feeling, emotion, and dwelling, which constitutes a habitation of the environment and a habitation of historical imagination. Historical topographies, marks of the past, became a form of narrative experienced through that movement, in that moving within the landscape constitutes a form of mnemonic practice through the formulation of place (Ingold and Lee Vergunst 2008, 9). The reinstatement of the embodied photographer and the suggestion of the innate complexity of experience can mitigate to some extent, at least analytically, against the sense of fragmentation, reduc-tion, and separation on which photographs conventionally insist and which reinforces a sense of detachment and alienation (Pallasmaa 2005, 39). Photographs in their still traces, and tropes of content and aesthetic, con-struct a stability to the places of memory and thus a stability of meaning associated with it, as they translate physical space into something his-torically, socially, and thus mnemonically experienced (Tilley 1984, 18).

More broadly, it also raises questions about embodied knowledge and bodies of experience, the corporeal conditions of visual knowledge and thus mnemonic practice. What is the relation, in terms of historical knowledge and photography, between embodied lives and disembodied knowledge? Maybe this conundrum has something to do with academic KLVWRU\¶V�XQHDV\�UHODWLRQVKLS�ZLWK�SKRWRJUDSKV²WKDW�WKH\�DUH�WRR�UDZ��too visceral. As Didi-Hubermann has argued, we expect too much of them and too little. Ask the whole truth, and we will be disappointed, for they are inexact, inadequate to the task, or we ask too little, “imme-diately relegating them to the sphere of the simulacrum” (2008, 33). But that perhaps is because we focus on the image alone, the end product of a range of linked photographic practices, rather than on a whole range and sequence of embodied experiences, acts and processes, ranged over space and time, of which the photograph is merely the result. These are the processes through which historical imagination might be performed and with which the very act of photography is entangled.

Out and About 205

Acknowledgments

This essay emerged as a tangent from a larger project on the activities of the photographic survey movement. I should like to thank all the librar-ians, archivists, and curators who made that research possible; without them this essay would not have been possible. I should also like to thank Olga Shevchenko and the participants in the Visible Presence sympo-sium in 2010 for their incisive comments and Liz Hallam and Annabella Pollen for their as ever thoughtful and productive comments throughout.

Notes1. See also Casey 1993; Feld and Basso 1996; Olick 2003.��� 7KHUH�LV��LQ�DGGLWLRQ��D�KXJH�OLWHUDWXUH�EXLOGLQJ�RQ�0DXVV¶V�FRQFHSW�RI�WHFKQLTXHV�

of the body, on the cultural production of the body, which cannot be fully explored here.

��� 6LPLODU�DUJXPHQWV�KDYH�EHHQ�PDGH�LQ�¿OP�WKHRU\��IRU�LQVWDQFH��-HDQ�5RXFK¶V�FODLP�WKDW�³¿OPPDNLQJ�IRU�PH�LV�WR�ZULWH�ZLWK�RQH¶V�H\HV��RQH¶V�HDUV��RQH¶V�ERG\��LW�LV�WR�enter into something” (quoted in MacDougall 2006, 27). A similar argument has been made for archives; see Rose 2000 and Robinson 2010.

4. John Taylor discusses photographic engagement with the picturesque itself as a form of “time-travel.” (Taylor 1994, 76–77).

5. Birmingham Photographic Society Council Minutes March 4, 1886. (Birmingham Archives MS 2507/1/2/1)

6. AP, 21 June 1895, 399.7. Birmingham Photographic Society Council Minutes, July 2, 1886. (Birmingham

Archives MS 2507/1/2/1); AP, May 31, 1895; September 9, 1898, 713.��� ³3O\PRXWK�3KRWRJUDSKLF�6RFLHW\¶V�2XWLQJ�´�AP, June 18, 1903, 499.9. For instance, the 1895 meeting in Shrewsbury offered no less than eight excursions

RYHU�¿YH�GD\V�WR�QRWDEOH�KLVWRULFDO�DQG�SLFWXUHVTXH�VLWHV��AP, January 25, 1895, 50.10. For instance, Taylor, 1994; Pollock, 2009; Jäger, 2003, 123–131.11. See also Naylor 2003, 315–7.12. BJP, 23 March 1900, 181.13. Birmingham Photographic Society Monthly Programmes etc. 1887–1904. L. F25.69,

f23. (Birmingham City Archives).14. Birmingham Photographic Society Monthly Programmes etc. 1887–1904. L. F25.69,

f14. (Birmingham City Archives); AP, 31 May 1895, 352.15. Woolwich Photographic Society Ledger, National Media Museum, Bradford, C6/53.16. Lecture to East Worcestershire Camera Club Bromsgrove Messenger. December 3,

1896 (JBS Cuttings Vol. 4 Birmingham City Library).17. See also Strauss and Orlove 2003.18. NCRO DD 1915/1/701-27.19. Woolwich Photographic Society Ledger 1902–1904. National Media Museum,

Bradford, C6/53.20. AP, 5 July 1901, 3.���� 3O\PRXWK�3KRWRJUDSKLF�6RFLHW\¶V�2XWLQJ�WR�7RWQHV��AP June 18, 1903, 499.22. LPS Scrapbook (WYL20/64/7/2). West Yorkshire Archives Service, Leeds.23. Essex Field Club (1906), 20, 257, Dr. Laver was a noted local antiquarian.24. Woolwich Photographic Society Ledger 1902–1904. National Media Museum,

Bradford, C6/53

206 Double Exposure

25. Birmingham Photographic Society, Monthly Programmes 1887–1904. Birmingham City Archives. L. F25.69, f.23.

26. Bingley was a major contributor to the British Association for the Advancement of 6FLHQFH¶V�FROOHFWLRQ�RI�*HRORJLFDO�3KRWRJUDSKV�LQ�WKH�����V�

27. BJP, February 6, 1892, 89.���� ,QJROG�KDV�GHVFULEHG�WKLV�DV�WKH�FUHDWLRQ�RI�³GRWWHG�OLQHV´�RI�LQWHUUXSWHG�VLJQL¿FDQFHV�

(2007, 88–89).29. AP, June 7, 1895, 368.30. LPS Scrapbook (WYL20-61/7/1/). West Yorkshire Archive Service, Leeds.31. For an extended discussion of this point see Edwards 2008b; 2009: 3–17.���� +��(��0��6XWWRQ�6FLHQWL¿F�6RFLHW\��AP, May 10, 1889, 305.33. AP, March 24, 1908, 329.34. See also Blau 1989, 40.35. “Diary of A South Warwickshire Survey on Cycles with the Camera” Ms. Birmingham

City Libraries, n.n. ff6.

ArchivesBirmingham City Archives (Birmingham Photographic Society Papers; Warwickshire

Photographic Survey Papers and Photograph Files, Sir Benjamin Stone [JBS] Cuttings volumes and invitation books).

Gloucestershire Archives (Photograph Files SR44/36297)National Media Museum, Bradford (RPS Collection).Nottinghamshire County Archives. (Nottinghamshire Survey Photographs DD

1915/1/101–727). West Yorkshire Archive (Leeds). (Papers of the Leeds Photographic 6RFLHW\��0LQXWH�%RRNV�:</��������±���6HFUHWDU\¶V�&RS\�%RRNV�:</���������

Published SourcesAbbreviationsAP Amateur PhotographerBJP British Journal of PhotographyNote: Only authored pieces are listed here. References to the mass of anonymous notes

in the photographic press are given in the endnotes.

ReferencesAkrich, Madelaine. 1992. “The De-scription of Technical Objects,” in Shaping Technol-

ogy: Building Society, edited by W.E. Bijker and J. Law, 205–224. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press.

Bal, Meike. 2003. “Visual essentialism and the object of visual culture.” Journal of Visual Culture. 2 (1): 5–32.

Bender, Barbara. 2002. “Time and Landscape.” Current Anthropology 43 (supplement): 103–12.

Berman, Morris. 1989. Coming to our Senses: Body and Spirit in the Hidden History of the West. London: Unwin Paperbacks.

Bille, M. and T. Flohr Sorensen. 2007. “The Anthropology of Luminosity: The agency of light.” Journal of Material Culture. 12(3): 263–84.

Blau, E. 1989. “Patterns of Fact: Photography and the Transformation of the Early Indus-trial City,” in Architecture and Its Image: Four Centuries of Architectural Representa-tion, edited by E. Blau and E. Kaufman, 36–57. Montreal: CCA.

Casey, Edward. 1993. Getting Back into Place. Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press.

Out and About 207

Crary, Jonathan. 1990. The Techniques of the Observer: On vision and Modernity in the nineteenth century. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press.

——— 2001.Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modern Culture. (Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

&VRUGDV��7KRPDV��������³7KH�%RG\¶V�&DUHHU�LQ�$QWKURSRORJ\�´�LQ�Anthropological Theory Today, edited by H. Moore, 172–205. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Connerton, Paul. 1989. How Societies Remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Creighton, Mandall. 1903. “The Study of a Country.” Addressing Annual meeting of the London University Extension Students April 3, 1897. In Historical Lectures and Addresses edited by Louise Creighton. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

de Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Dellheim, Charles. 1982. The Face of the Past: The Preservation of the Medieval Inheri-tance in Victorian England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. 2008. Images in Spite of All: Four Photographs from Auschwitz, transl Shane. B. Lillis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Edwards, Elizabeth. 2008a. “Thinking Photography Beyond the Visual?” in Photography: Theoretical Snapshot, edited by Jonathan Long, Andrea Noble & Edward Welch, 31–48. London: Routledge.

———. 2008b. “Straightforward and Ordered: Amateur Photographic Surveys and Sci-HQWL¿F�$VSLUDWLRQ�����±�����´�Photography and Culture. 1(2): 185–210.

———. 2009. “Unblushing Realism and the Threat of the Pictorial.” History of Photog-raphy. 33(1): 3–17.

———. 2012. Camera as Historian: Amateur Photographers and Historical Imagination 1885–1918. Durham NC: Duke University Press.

———. 2013 [forthcoming]. “Between the Local, National and Transnational: Photographic Recording and Memorializing Desire,” in Transnational Memory: Beyond Methodologi-cal Nationalism edited by A. Rigney and C. de Cesare. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Edwards, Elizabeth and Peter James. 2006. A Record of England: Sir Benjamin Stine and the National Photographic Record Association. Manchester/London: Dewi Lewis/V&A Publications.

Feld, Steven and Keith H. Basso (eds). “Introduction”, in Senses of Place, 3–11. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

Feld, Steven. 1996. “Waterfalls of Song,” in Senses of Place, edited by S. Feld and K. Basso, 91–136. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

Fowler, C. J. 1897. “Photographic Survey.” BJP July 30, 1897: 488–490.Frake, Charles O. 1996. “Pleasant Places, Past Times and Sheltered Identity in Rural East

Anglia,” in Senses of Place edited by S. Feld and K. Basso, 229–257. Santa Fe NM: School of American Research Press.

Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

P. Gilbert (ed). 2002. “Introduction,” Imagined Londons. New York: SUNY Press.Gower, H.D., L. Stanley Jast and W.W. Topley. 1916. The Camera as Historian: A hand-

book to Photographic Record Work for those who use a Camera and for Survey or Record Societies. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Co.

Hansen, Peter. 2001. “Modern Mountains: The Performative Consciousness of Modernity in Britain 1870–1940,” in Meanings of Modernity: Britain from the Late-Victorian Period to World War II, edited by M. Daunton and B. Rieger, 185–202. Oxford: Berg.

Harrison, W.J. 1885. “Light as a Recording Agent of the Past.” Photographic News. 8 January (1885): 23.

208 Double Exposure

———. 1889. “Some Notes on a proposed Photographic Survey of Warwickshire,” Photographic Societies Reporter. 31 December (1889): 505–515.

———. 1892. Proposal for a National Photographic Record and Survey. London: Harrison and Co.

Ingold, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment. London: Routledge.———. 2007. “Earth, Sky, Wind, and Weather,” in Wind, life, health: and anthropologi-

cal and historical perspectives, edited by Chris Low and Elisabeth Hsu, JRAI Special Issue 2: S19–38.

———. 2007. Lines, A Brief History. London, Routledge.Ingold, Tim and Jo Lee Vergunst (eds). 2008.Ways of Walking: Ethnography and Practice

on Foot. Farnham: Ashgate.Jäger, Jens. 2003. “Picturing Nations: Landscape Photography and National Identity in

Britain and Germany in the Mid-nineteenth Century,” in Picturing Place: Photogra-phy and the Geographical Imagination, edited by J. Schwartz and J. Ryan, 117–140. London: I.B. Tauris.

Jay, Martin. 1993. Downcast Eyes: The Denigration of Vision in Twentieth Century Thought. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1993.

Lee Jo and Tim Ingold. 2006. “Fieldwork on Foot: Perceiving, Routing, Socializing,” in Locating the Field: Space. Place and Context in Anthropology, edited by Simon Coleman and Peter Collins, 67–85. Oxford: Berg.

Low, Chris and Elisabeth Hsu. 2007. “Introduction,” in Wind, Life, Health: Anthropologi-cal and Historical Perspectives. JRAI Special Issue 2: S1–S17.

MacDougall, David. 2006. The Corporeal Image: Film, Ethnography, and the Senses. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Matless, David. 1992. “Regional Surveys and Local Knowledges: The Geographical Imagination in Britain, 1918-39,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. N.S.17(4): 464–480.

Mitchell, W.J.T. 2005. “There Are No Visual Media,” Journal of Visual Culture. 4(2): 257–266.

Naylor, Simon. 2003. “Collecting Quoits: Field Cultures in the History of Cornish Anti-quarianism,” Cultural Geographies 10: 309–333.

Olick, Jeffrey. 2003. The States of Memory. Durham NC, Duke University Press.Riegl, Alois. 1982. “The modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin,” transl.

K. Forster and D. Ghirardo. Oppositions. 25 (Fall 1982 [1928]), 33: 21–51.Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2005. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. Chichester:

Wiley–Academic.Pinney, Christopher. 2003. “Visual Culture,” in The Material Culture Reader, edited by

V. Buchli. Oxford, Berg.Pollock, Verna Louise. 2009. “Dislocated Narratives and Sites of Memory: Amateur

Photographic Surveys in Britain 1889–1897,” Visual Culture in Britain. 10(1): 1–26.Robinson, Emily. 2010. “Touching the Void: Affective History and the Impossible,”

Rethinking History. 14(21): 503–520.Rose, Gillian. 2000. “ Practicing Photography: An Archive, a Study, Some Photographs

and a Researcher,” Journal of Historical Geography. 26(4): 555–571.Runia, Eelco. 2006. “Presence,” History and Theory. 45: 1–29.Shapin Steven and C. Lawrence (eds). 1998. “ Introduction: The Body of Knowledge,”

in Science Incarnate: Historical Embodiments of Natural Knowledge. Chicago: Uni-versity of Chicago Press, 1–20.

Smith, Angèle. 2003. “Landscape Representation: Place and Identity in Nineteenth Century Ordnance Survey Maps of Ireland,” in Landscape. Memory and History: Anthropological Perspectives, edited by Pamela J. Stewart and Andrew Strathern, 71–88. London: Pluto Press.

Out and About 209

Stewart, Pamela J. and Andrew Strathern (ed.). 2003. “Introduction,” in Landscape. Memory and History: Anthropological Perspectives, 1–15. London: Pluto Press.

6WROHU��$QQ�/DXUD��������³,PSHULDO�'HEULV��5HÀHFWLRQV�RQ�5XLQV�DQG�5XLQDWLRQ�´�Cultural Anthropology. 23 (2):191–219.

Strauss, Sarah and Ben Orlove (eds). 2003. Weather, Climate, Culture. Oxford: Berg.Taylor, John. 1994. A Dream of England, Manchester: Manchester University Press.Tilley, Chris. 1984. The Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths and Monuments.

Oxford: Berg.———. 2004. The Materiality of Stone. Oxford: Berg.Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1995. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History.

Boston: Beacon Press.Williams, Raymond. 1961. The Long Revolution. London: Chatto and Windus.Yudell, Robert. 1977. “Body Movement,” in Body Memory and Architecture, edited by

Kent C. Bloomer and Charles W. Moore. New Haven: Yale University Press.Zerubavel, Eviatar. 2003. Time Maps: Collective Memory and the Social Shape of the

Past. Chicago: Chicago University Press.