On the efficiency of environmental service payments: A forest conservation assessment in the Osa...

Transcript of On the efficiency of environmental service payments: A forest conservation assessment in the Osa...

E C O L O G I C A L E C O N O M I C S 5 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 1 3 1 1 4 1

ava i l ab l e a t wwwsc i enced i rec t com

wwwe l sev i e r com l oca te eco l econ

ANALYSIS

On the efficiency of environmental service payments A forestconservation assessment in the Osa Peninsula Costa Rica

Rodrigo Sierra Eric RussmanDepartment of Geography and the Environment Mail Code A3100 University of Texas at Austin Austin TX 78712 USA

A R T I C L E I N F O

Corresponding authorE mail addr ess rsierrama ilutexasedu (R

0921 8009$ see front matter copy 2005 Elsevidoi101016 jecolecon2005 10010

A B S T R A C T

Article historyReceived 27 April 2005Received in revised form20 September 2005Accepted 17 October 2005Available online 7 December 2005

This study examined the efficiency of programs supporting the conservation of forestresources and services through direct payments to land owners or payments forenvironmental services (PES) The analysis is based on a sample of farms receiving andnot receiving PES in the Osa Peninsula Costa Rica Results indicate that payments havelimited immediate effects on forest conservation in the region Conservation impacts areindirect and realized with considerable lag because they are mostly achieved through landuse decisions affecting non forest land cover PES seem to accelerate the abandonment ofagricultural land and through this process forest regrowth and gains in services Thiswould be a double gain (current plus future forest services) except that our results alsosuggest that in the absence of payments forest cover would probably be similar in PES andnon PES farms and that forest regrowth would also take place albeit at a slower rate Thesefindings have important policy implications Specifically they suggest that locallypayments could be more effective if they are used for restoration purposes In theircurrent form PES landholders have no long term obligation to let abandoned lands revert toforest Payments for restoration would remove this uncertainty Because of the lag inconservation outcomes they may also be insufficient at larger geographic scales if there areother forest areas where the immediate risk of habitat and service loss is higher In the shortrun resources would be better used if invested in these higher risk areas At a more generallevel this study lends support to the growing expectation that project administratorsimprove their capacity to target payments where they are most needed and not simplywhere they are most wanted

copy 2005 Elsevier BV All rights reserved

KeywordsEnvironmental paymentsForest conservationBiodiversityEcological servicesCosta Rica

1 Introduction

This study aims to contribute to the understanding of howpayments for environmental services (PES) work to protectand restore ecological services generated by and the biodiversity found in privately owned natural habitats Widespreadconcern over biodiversity extinction dominated the conserva

Sierra)

er BV All rights reserved

tion agenda for several decades More recently the role ofbiodiversity in general and of natural ecosystems in particular to maintain vital ecological processes has also beenrecognized (Hoekstra et al 2005 Ives et al 2005) It is alsobecoming increasingly clear that conservation policy shouldrespond to site specific ecological and socio economic conditions to protect and restore natural habitats where the need is

132 E C O L O G I C A L E C O N O M I C S 5 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 1 3 1 1 4 1

greatest This concern is motivated in large part by thedecline in international funding for conservation during thepast decade but also by a greater awareness that certainhabitats face greater risk than others (Sierra et al 2002 Sierra2005) It is no longer acceptable to expend resources in anopportunistic manner as has typically been the case Theexpectation is that available resources are used to protectcritical ecosystems first

A growing body of research also suggests that maintainingecological services demands strict large scale protection ofentire ecosystems beyond the boundaries of protected areas(Meffe and Carroll 1997 Simberloff et al 1999 Souleacute andTerborgh 1999) Today most remaining natural habitats areon private hands either individually or communally and it isunlikely that sufficient amounts of these lands will ever beincluded under protected management domains due topolitical economic and cultural factors Unfortunately command and control conservation mechanisms (ie laws andregulations) have proven ineffective in these areas especiallyin the developing world (Sierra 2001 Faith and Walker 2002)The most common alternative has been the implementationof programs designed to redirect labor and capital away fromactivities that degrade ecosystems and cause biodiversity lossThis approach often called integrated conservation anddevelopment programs has been labeled ldquoindirectrdquo by scholars of market based conservation Billions of dollars wereinvested in such endeavors in the 1980s and 1990s (Ferraroand Simpson 2002 Landell Mills 2002) However by the mid1990s the initial optimism had cooled to cautious interestThough some projects were having noticeable effects (Schelhas 1995) observers concluded that most interventions hadfailed or were failing Rice (2004) labeled this approachldquoconservation by distractionrdquo Studies showed that the barriers to change were much too complex (Ferraro and Kiss2002) Even when conservation projects were able to changelocal resource use strategies in the short term interventionsrarely altered the incentives that prompted local resourceusers to degrade habitats in the first place Because marketsoffer no compensation for protecting natural habitats landowners have no incentives to conserve them favoring theirtransformation to agriculture or intensive resource extraction(eg logging) This results in the loss of the services and goodsof great social but relatively small private value that theyprovide In this tragedy of the private lands including thosecontrolled as community territories land owners bear thewhole cost of conservationwhilemanymore share its benefitswithout compensating them

Recognizing these shortcomings some analysts and conservation practitioners are recommending to compensateland owners directly for the economic losses associated withhabitat conservation with payments that correspond to thegain in services kept (Alix et al 2003 Pagiola 2002) In theideal system the provision of services would be negotiated byusers and producers (ie owners of the habitats where theprocesses take place) through market transactions Howeverthis transition requires that markets be created where noneexisted before not an easy task given the nature of theservices involved Many experiments with this conservationmodel are now being conducted on the supply side of theequation in the form of PES By the 1990s there were close to

300 related initiatives planned or in the early stages ofimplementation (Landell Mills and Porras 2002) many indeveloping countries For example Mexico is implementing anationwide PES scheme to address their perceived deforestation problem (Alix et al 2003) Organizations such asConservation International which just a few years ago hadno experience in direct market transactions now havemillions of dollars tied up in contracts protecting importantecosystems

There are however important gaps in our understandingof the way PES work and their relative and absolute contribution to conservation A key unknown is how much additionalconservation is obtained through PES a concept often referredto as additionality Additionality simply means that theoutcomes of a policy or project are in addition to what mighthave occurred due to other direct and indirect factors(Shrestha and Timilsnia 2002) or in this case in the absenceof payments A second question relates to the multi scalenature of conservation priorities and the potential for in farmand off farm leakages Land use decisions are complex andsimultaneous It is not well known how payments are used byrecipients and how these decisions indirectly contribute to orsubtract from the overall impacts of PES Farmers may usepayments for example to transfer farming activities to otherforest areas not covered by PES in the same region or even inthe same farm They may even be used to increase thepressure on more critical ecosystems or for intensifyingexisting productive activities with relatively greater environmental impacts

Unfortunately until now there has been limited empiricalresearch linking land use decisions and ecosystem protectionand restoration to PES programs Project reports show the sizeand location of lands set aside for PES contracts but it is oftenunclear if the new conservation area is additional to whatmight have been conserved in the absence of conservationpayments A recent study of the Countryside StewardshipScheme in England determined for example that between36 and 38 of agreements showed some level of additionality and concluded that the program is likely to provide abenefit to society (Carey et al 2003) However this analysiswas based on the farmers perception of the impact of a signedagreement and not on land cover outcomes Similarly anattitudinal study in Costa Rica showed that PES farmersoverwhelmingly believed that this countrys program wascontributing to the protection and restoration of tropicalforests (Ortiz 2004) Forty three percent of landholders saidthey had abandoned agriculture and pasture fields whenoffered the PES option On the other hand recent nationwideland cover studies demonstrate that secondary forestincreased at a rate of 13000 ha per year from 1987 to 1997due in part to a series of environmental and economic factorsthat affected the value of cattle and agricultural production(World Bank 2000) Hence it remains unclear if landmanagerswithout payments were also abandoning agriculture in thesame way as a result of other relevant forces

Within this context this study examines the PES programin theOsa Peninsula Costa Rica Costa Rica is often cited in theliterature as a pioneer in market based conservation initiatives (Chomitz et al 1999 Pagiola 2002) Nearly all sectors ofsociety have embraced the PES concept and are actively

133E C O L O G I C A L E C O N O M I C S 5 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 1 3 1 1 4 1

lobbying for increased funding to make it available to morelandholders (Barrantes et al 1999 Brockett and Gottfired2002 Sanchez et al 2002a) Costa Rica therefore providesfertile ground to research how PES programs work to protectand restore ecological services in private lands Specificallyour analysis responds to three questions 1) Are land usedecisions of landholders of PES and non PES farms different2) If different what role PES relative to other factors play inexplaining this variation And 3)What are the in farm and offfarm conservation implications of PES in the Osa PeninsulaOur analysis assumes that land use decisions are reflected inland cover characteristics and that these in turn manifesthow payments work for conservation This approach has theadvantage that land cover is relatively easy to be quantifiedand subsequently associated with key factors that areexpected to play a determining role in land use decisions

2 Conserving biodiversity and ecosystemservices in privately owned lands

There is a long history of programs designed to pay landowners directly to encourage particular land managementpractices to promote the conservation of specific physicalresources or in some important cases to maintain commodity prices For example charging water users to compensateupstream land owners has been used successfully in Japan forover 100 years (Richards 2000) In developed countriesgovernment agencies have provided for decades financialincentives to farmers to keep agricultural land out of production or shift it to alternative uses In Europe 14 countries spentan estimated $11 billion between 1993 and 1997 to divert over20million ha into long term forestry contracts (OECD 1997) Inthe 1990s the United States Conservation Reserve Programspent about $15 billion annually on contracts for 12 15millionha (Clark and Downes 1999) an area twice the size of CostaRica

Land owners participating in PES programs also agree toapply specific conservation schemes in their lands for a givenperiod of time in exchange for a payment However the mainobjective of PES programs is to promote the conservation ofecological processes Although subtle this difference issignificant Resources such as water and soils can be storedand their use by third parties restricted These are usuallyconceived as local assets not connected to other areas orregions In contrast ecological processes are a fund serviceproperty of biodiversity They cannot be stored and are nonexclusionary (Daley and Farley 2004) Owners of the habitatswhere these take place who do not capture their value nowincur in a permanent loss Furthermore they cannot impedethat other users locally or globally benefit from themwithoutcompensation Indeed their value is often based on the rolethey play in determining natural economic and socialconditions in places that are often far removed from wherethey take place PES programs are an attempt to link thisspatially disjunct value system through the creation of quasimarkets for environmental services based on subsidiesprovided by conservation agencies multilateral organizationsand governments PES programs are expected to be anintermediary stage in the formation of true markets for

environmental services in which beneficiaries of the servicesand goods provided by specific habitats would pay landowners for their conservation

To facilitate the development of markets and the interaction of providers and buyers researchers have been trying toqualify and quantify the value of ecosystem services This isproving difficult because we still know so little about thespecific services ecosystems provide In fact different economic valuation techniques often generate quite distinctresults (Nasi et al 2002) Consequently researchers arefinding that valuation efforts can contribute most by determining how much one would have to pay different groups toget them to maintain land under natural cover (ie theirwillingness to accept) rather than the value of the serviceHowever this proxy approach has important drawbacksbecause of the complexity and simultaneity of land usedecisions Specifically it is difficult to disentangle decisionsabout natural habitat (eg forest) use from decisions aboutagricultural investment It should be expected that given a setof initial conditions land labor capital and technologylandholders simultaneously allocate multiple resources tomaximize production andminimize risk For a landholder theopportunity cost of a habitat fragment in his or her land maybe positive but if a payment is sufficiently high farmers maybe willing to accept it to dump other activities with lower orequal value even before they consider natural habitats Infact the opportunity cost of a habitat may be so low thatlandholders may leave a habitat untouched even without apayment incentive As long as a payment is equal or greater toany land use alternative landholders are likely to accept itfreeing the resources that are tied into that activity (eg labor)and allocating them to the next best alternative In this casePES may be subsidizing the productive activities of landholders and not hisher conservation activities This issue isespecially problematic because currently most PES programsincluding in Costa Rica select landholders on a first comefirst served basis as well as on the lobbying power ofinterested NGOs and landowners (Barton et al 2004) Thisapproach may lead to an over subscription to the program orthe unintended inclusion of owners seeking to dump otheractivities with a value lower than the payment and theexclusion of critical habitats

There is also the difficulty of adapting payments to thespatial variability of both the value of the service and the riskof service loss Some habitats are more valuable than othersbecause the benefit that users obtain from the services theygenerate is greater and some are more valuable because therisk of losing them locally regionally or globally is higher orboth This variability of the value of the conservation ofhabitats at regional and global scales points to the need toframe the analysis of PES efficiency as a multi scale issue Todetermine additionality researchers must first establishbaseline scenarios and understand how other factors affecthabitat cover change in an area and its relation to the overall(eg regional) conservation priorities These scenariosbroadly described are the collective set of economic financialregulatory and political circumstances within which land usedecisions operate (Moura Costa et al 2000) and the relativeglobal and regional risk of biodiversity and ecological serviceloss A PES program may be successful at a local scale but

134 E C O L O G I C A L E C O N O M I C S 5 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 1 3 1 1 4 1

inefficient at a regional or even global scale (but it cannot beregionally efficient if it is not locally successful) This wouldoccur if local conservation takes place at the expense of theconservation of more critical habitats and their services inother areas This of course does not take into account theexistence and evolutionary value of biodiversity Currentexperiments do not address these issues yet Ultimately theefficiency of PES rests on the additional contribution toconservation they provide (Shrestha and Timilsnia 2002)

3 PES in Costa Rica

The addition of conservation payments to the conservationarsenal has been warmly received in Costa Rica as evidencedby the fact that the countrys PES program has attracted fivetimes more applicants than it can pay for (Pagiola 2002)Government and civil society also see them as a way to meetthe countrys objective of protecting biodiversity Costa Ricasfirst effort to use economic instruments dates back to 1979when the first Forestry Law established tax based incentivesThese had limited effect since few landholders had land titlesand thus paid property taxes Subsequent laws were intendedto increase accessibility of small rural landholders In 1986 theCertificados de Abonos Forestales (CAF) provided tax exemptionsduring the first five years of reforestation up to the amount ofthe total costs However CAF did little to prevent logging ofprimary forest or as effective stimulants for reforestation(Ortiz 2004) This program also created distortions thatfavored plantation forests over natural forest which usuallyprovide greater service value andwas finally cancelled in 1995(World Bank 2000 Rojas and Aylward 2003)

In 1996 Forestry Law 7575 introduced the current PESsystem By this time Costa Rica already had in place anelaborate system of payments for reforestation and forestmanagement and the institutions to manage it (Rojas andAylward 2003) The law provides the legal and regulatory basisto contract with land owners for the environmental servicesprovided by their lands empowers the National ForestryFinancing Fund (FONAFIFO) to issue such contracts andestablishes a financing mechanism for this purpose Thefour environmental services recognized by the new forest lawinclude 1) mitigation of green house gas emissions 2)hydrological services including provision of water forhuman consumption irrigation and energy production 3)biodiversity conservation and 4) provision of scenic beauty forrecreation and ecotourism PES are expected to provide theseservices by protecting primary forest allowing secondaryforest to flourish and expanding forest cover though plantations These goals are met through site specific contracts withindividual small and medium sized farmers In all casesparticipants must present a sustainable forest managementplan certified by a licensed forester as well as carry outconservation or sustainable forest management activitiesDifferent compensation amounts and contract durations areprovided for 1) forest protection (5 year duration and $210 perhectare dispersed over 5 years) 2) sustainable forest management (15 year duration and $327 per hectare dispersed overfive years) and 3) reforestation activities (15 to 20 yearduration and $537 per hectare dispersed over five years)

Differences reflect the relative cost associated with eachactivity Forest protection receives the lowest paymentbecause there is relatively little overhead Sustainable forestmanagement receives more to cover the cost of designing andimplementing a sustainable harvest Reforestation receivesthe highest compensation in order to cover the high cost ofplanting and maintaining tree plantations The $42ha peryear paid for forest protection reflects the loss of revenue thatlandholders would earn if their forest were converted topastures or other land uses (Ortiz et al 2003) Between 1997and 2003 more than 375000 ha had been included in almost5500 PES contracts with a total cost of $962 million Almost87 of this area was under forest protection contracts (Ortiz2004)

One of the main initial concerns was how to fund CostaRicas PES program In 1997 the Kyoto Protocols concept ofJoint Implementation (JI) offered an opportunity to overcomethis barrier JI is a mechanism whereby a donor countrycontributes to the implementation of pollution abatementmeasures in a host country in return for credits to meet itsown pollution abatement obligations While it was initiallyseverely criticized by nearly all developing countries (Grubb1999) Costa Rica supported it and immediately set up theCosta Rican Office on Joint Implementation (Oficina Costarricense de Implementacioacuten Conjunta or OCIC) to attract funding(Rojas and Aylward 2003) Expectations that Costa Ricasexperiment with PES would attract large amounts of outsidefinancial support were high from the start The Costa Ricanlegislature authorized the Ministry of the Environment to findinternational partners for the PES program so that the cost ofproducing environmental services like CO2 reduction could beshared with the international community By 2003 theprogram was primarily financed by fuel taxes (Ortiz et al2003) However a World Bank loan and a GEF grant wereneeded to meet expected PES shortfalls until the year 2005(Rojas and Aylward 2003) Fortunately for advocates of PESprograms opportunities for international cooperation appearto be increasing

4 Data

Farm level payment and land cover data for this study waspooled from four sources 1) a list of PES beneficiaries from theFondo Nacional de Financiamiento Forestal (FONAFIFO) 2)archival research in the offices of the Ministry of theEnvironment and Energy in Puerto Jimenez 3) a recent landtenure land use study by Centro de Derecho Ambiental y deRecursos Naturales (CEDARENA) and 4) personal interviewsconducted by the second author on the Osa Peninsula duringJuly and August 2003 Additional information for modelimplementation was obtained from official cartographic datafor farms infrastructure rivers and terrain

The initial database included 61 farms receiving PES forforest protection and 585 non PES farms Other type of PEScontracts were not included in this analysis Both PES andNon PES farms were georeferenced and digitized by CEDARENA and FONAFIFO All the farms below 30 and above 350 hawere eliminated from both samples The lower threshold isthe minimum size that was considered consistent with the

135E C O L O G I C A L E C O N O M I C S 5 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 1 3 1 1 4 1

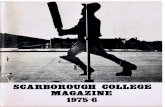

level of cartographic detail used in this study to generatespatial data for model implementation The upper thresholdcorresponds roughly to the largest area that could be placedunder PES contract in any given farm1 Thirty PES farms metthis criteria This is equivalent to approximately 1 of every 6PES farms in the Osa Peninsula2 Thirty non PES farms wereselected randomly from the non PES set that met the samecriteria for comparison (Fig 1)

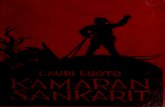

Farm level land cover characteristics measured aspercent of a farms area were extracted from field surveysfor the following classes 1) agriculture 2) charral 3)intervened forest and 4) primary forest (Fig 2) Each classrepresents distinctive land use conditions recognized bylocal forest engineers and landholders The agriculture classincludes pasture agricultural fields fruit orchards andAfrican palm plantations Charral corresponds to abandonedor fallow agricultural areas for 2 7 years that are in theprocess of early secondary succession Charral areas havedense undergrowth and occasional emergent trees but arestill lacking substantial qualities to be considered secondaryforest Intervened forests have observable signs of humanintervention These were usually managed for timberextraction in the past one to two decades or are the resultof late secondary succession where pastures and agriculturalfields have been abandoned for over a decade Primaryforests are closed canopy forest with relatively little humanintervention

5 Group comparison and model specification

Land use decisions of landholders of PES and non PES farmswere assessed based on the land cover characteristics of eachfarm for each of the four land cover types described aboveTheir land cover characteristics were compared using analysisof variance (ANOVA) for the total sample and subsets of PESfarms based on the length of time that the contracts had beenin place

The role of PES relative to other factors was examinedthrough an set of OLS regression models that explainvariations in land cover as a function of PES incentives andproxy measures for regional and local costs of agriculturalproduction The general model is specified as

LndCov athorn a1TransportCostthorn a2ConvertCostthorn a3PES eth1THORN

where LndCov is the land cover characteristic for each farmLndCov is measured as the percent of each farm under eachland cover class plus total forest (intervened plus primaryforest) and total agriculture (charral plus agriculture) TransportCost is an estimate of the relative transportation costs

1 Contracts for areas greater than 300 ha are possible whenmade with groups of farmers or with indigenous communitiesOnly 34 of the total area under PES were under these contracttypes in 2001 (Ortiz et al 2003)2 There were approximately 180 farms in the Osa Peninsula in

2003 The last precise count is from 2001 when 170 farms hadreceived PES (Ortiz et al 2003) Based on the trends of theprevious years we expect that no more than 10 new farms wereadded to the group between 2002 and 2003

from each farm to the main regional transportation hub It isused here as a proxy measure of the attractiveness oftransforming a forest area into other land uses ConverCostis a relative measure of each farms terrain characteristics Itused here as a proxy measure of the attractiveness oftransforming a forest area into other land uses based on thecost of converting forest cover to agricultural land covers PESis a dummy variable for the presence of payments in a farm

Relative regional transportation costs were calculated foreach farm from its centroid to the point where the peninsulasmain road joins the mainland highway A travel time mapwas created using a weighted or cost distance proceduretaking into consideration the type of roads and slope in theOsa Peninsula Each road type and the area outside roads wasassigned a relative time cost index based on an expectedaverage travel speed In addition travel outside of roads waspenalized based on the slope of terrain The log of the rawtravel time value from each farm was used in the modelLower weighted distances such as those of farms close to thehub or to roads result in lower transportation costs andgreater incentives for agricultural land uses This approach isconsistent with multiple studies showing that transportationconstraints are among the most significant and reliablefactors related to forest conversion to agricultural land (egSader and Joyce 1998 Angelsen and Kaimowitz 1999 Pfaff1999) Conversion costs are a relative measure of on siteproduction costs in each farm ie the accessibility to forestresources for logging or the costs and expected benefits oftransforming forest areas to agriculture independent of afarms distance to roads and markets These were estimatedas the average slope of each farm (in percentages) Slope wasderived from a 50 m digital contour data from the GEF INBioEcomap project (Kappelle et al 2003)

6 The land cover outcomes of PES in the OsaPeninsula Costa Rica

Table 1 shows the land cover characteristics of each studygroup the length and proportional coverage of PES in farmsreceiving payments and the results of the ANOVA analysisThe typical (ie Non PES) landholder in the Osa Peninsulaleaves a large fraction of the land under forest cover (75)Approximately two thirds of this area is primary forest Theremaining third are intervened forests The typical farmer alsoallocates almost 10 times more land to active agriculture thanto temporary or permanent fallow or charral

The overall expectation of the way PES work for conservation in a typical farm is illustrated in Fig 3 The initial pressureon forest resources in the region is expected to result inchanges in forest cover in a typical farm equal to vector ab at arate equal to its slope which is equal to the sum of the rate ofdeforestation plus the rate of logging in the region Accordingto Sanchez et al (2002b) forest area in the Osa Peninsuladeclined from977 to 896 km2 between 1977 and 1997 when thePES program began This is equivalent to an annual deforestation rate of 04 With PES forest area in some farms shouldstabilize as in vector bc but is expected to continue to declinein farms without payments shown by vector bd with thedifference in forest cover conditions increasing with time

Fig 1 ndashStudy area map Location and relative size of PES and Non-PES farms is shown

136 E C O L O G I C A L E C O N O M I C S 5 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 1 3 1 1 4 1

Indeed the underlying rational of and the justification for PESis that a payment is needed to avoid bd This is achieved bycompensating landowners for the loss of income resultingfrom forest conservation In the long run the expected resultof PES would be a gain of forest cover equivalent to n This isthe additional impact of PES In theory landowners shouldaccept payments that are equivalent to the marginal return ofthe forest being put under contract The fact that not all forestsare placed under contract suggest that some forest areas mayhave a greater marginal return that the payment option

The comparison between forest cover conditions in PESand Non PES farms however highlights important inconsistencies with this model Forest cover conditions in the twogroups are statistically similar whether the comparison ismade for primary intervened or total forests (Table 1) Indeedwhile under the initial set of assumptions it cannot beexpected that or tested if forest cover increased in PESfarms in the maximum of six years the contracts had been ineffect it should be expected that a noticeable area of forestshould have been cleared or logged in Non PES farms in thatperiod Using the deforestation rates reported by Sanchez et al(2002a) in six years forest cover in non PES farms should havedeclined by an average of 25 This assumptionwas tested bycomparing forest cover conditions in farms where conservation contracts have been active for the longest time (5 years ormore N 12) with farms without contracts (Table 1) Thestatistical similarity in forest cover conditions between thesetwo groups leads to the preliminary conclusion that there wasno difference in the way land owners decided to allocate landto forest and non forest cover types at the time the contractsbegan This assumption is supported by two land cover studiesin the Osa Peninsula Rosero et al (2002) show that between

1980 and 1995 before the implementation of the PES programpasture and agricultural lands were already being abandonedand were returning to forest cover Sanchez et al (2003) foundthat no deforestation occurred between 1986 and 1997 inbuffer areas of two protected areas in the same area

There is however an alternative scenario that wouldexplain these similarities If the initial marginal value ofconverting one additional hectare of forests to agriculturalland cover in current PES farms was higher than in Non PESfarms the pressure to convert them to agriculture or log themwould also be higher and their forest cover proportionallylower than in Non PES farms at the beginning of contractsThis is illustrated by the steeper vector ae for PES farmsrelative to the vector ab for Non PES farms before contractAfter contract forest cover in PES farms stabilizes (ie vectored) while forest cover in farms without conservation incentives continue to drop (ie vector bd) approximating forestcover conditions in PES farms in this case at the time of ourobservations This assumption was tested by comparingforest cover conditions in farms where conservation contractshave been active for a short time (2 years N 12) with farmswithout contracts In these farms the difference in forestcover would be expected to be the greatest (differencem in Fig3) Table 1 shows the results of the ANOVA analysis for thesetwo groups of farms The statistical similarity also supportsthe preliminary conclusion that there was no difference in thepressure to convert forest in these two groups beforecontracts

In contrast Non PES farmers allocate significantly moreland to active agriculture than PES farmers a proportion ofalmost 3 to 1 and even less land to charral a proportion ofmore than 1 to 4 This suggest that in Non PES farms

Fig 2 ndash Illustration of land cover types used in this study

137E C O L O G I C A L E C O N O M I C S 5 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 1 3 1 1 4 1

agriculture is significantly more attractive than in PES farmsThis distinction is statistically significant whether the comparison is made with the proportional area dedicated to eachagricultural land use or with the proportion of active toinactive agricultural land or charral In fact the greatmajority(25 out of 30) of Non PES farms have very small or no charralcover a condition that probably reflects pre contract trends incurrent PES farms This assumption is supported by thedissimilarity of charral cover in PES farms with recent

contracts (2 years) and Non PES farms However the relativevalue of agricultural land changes with the availability ofcapital from conservation payments Payments allow landholders to accelerate their exit of agriculture as suggested bythe significantly lower proportion of agricultural land in olderPES farms relative to Non PES farms Indeed as illustrated inFig 4 the time a farm has been under a conservation contractseems to play an important role in defining how much land isdedicated to agriculture The longer the payments have been

Table 1 ndash Land cover characteristics of PES and Non-PES farms and results of group comparison (ANOVA)

Land cover Typical (Non PES) farms PES farms ANOVA significance

N Min Max Mean SD N Min Max Mean SD Totalsample

PESyears 2

PESyears N5

Size (ha) 30 440 2820 1170 773 30 390 3390 1273 714Years under PSA 30 00 00 00 00 30 20 60 39 16 na na na of farm under PSA 30 00 00 00 00 30 460 1000 841 02 na na na under primary forest 30 00 1000 560 319 30 00 1000 512 353 under intervened forest 30 00 1000 191 304 30 00 1000 298 309 under forest (Int+Pri) 30 167 1000 751 224 30 286 1000 810 181 under agriculture 30 00 833 226 223 30 00 536 78 127 under charral 30 00 222 25 53 30 00 714 112 159 transformed (Ag+Ch) 30 00 833 251 227 30 00 714 190 180Ratio primary to intervened

forest30 00 1000 105 294 30 00 1000 187 349

Ratio total forest to total agricultural 30 02 1000 211 366 30 04 1000 224 362Ratio agricultural to charral 30 04 843 181 227 30 00 546 44 113

Key significance na=not applicable =not significant =01 =005 =001

138 E C O L O G I C A L E C O N O M I C S 5 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 1 3 1 1 4 1

in effect the less agriculture a farm has By the fifth yearalmost all farmers receiving PES have abandoned agriculturealtogether The fact that the variability in the degree ofabandonment is greater early into the contract suggest thatthis ldquopush to exit agriculturerdquo is an ongoing process happening whether farmers were actively working in agriculture ormarginally dedicated to agriculture Payments facilitate andmaybe are critical for bolstering the abandonment process Onthe other hand we cannot say that PES is preselected by thosewith lower agricultural share In fact our analysis of variancesuggest that there is no difference between these groups interms of agricultural area when the begin PES (See Table 1)Furthermore by pulling both the charral and agriculturalconditions together it is possible to propose the possibility thatPES farms were more agricultural than Non PES farms beforePES began Thiswouldmean that these farms are farther alongin the abandonment process since they have more ldquocharralrdquo(fallow) and the same amount of agricultural land

These findings in turn suggest that there are otherfactors that should explain the variation of forest andagricultural cover in both groups These relationships areexplored by Model 1 (Table 2) As expected from the previous

Fig 3 ndashModel schematic of the impact of PES on forest landcover

discussion models 1a and 1b show that PES do not affectlandholders decisions about how much primary or intervened forest cover is left in a farm These models also showthat local conversion costs or regional transportation costsdo not affect the decision to leave a forest area intact or tolog it for the individual types of forest but do affect totalforest area There are other factors not included in themodel which explain the variation in the decision to log ornot to log a forest This condition and the significance ofthese factors as explanatory variables for the decision aboutallocation of land to agricultural uses (model 1f) suggeststhat landholders make land use decisions based primarily onthe marginal value of agriculture which is strongly butinversely affected by both types of costs Farmers withgreater transportation costs have less incentives to clearforest for agriculture but they may or may not extracttimber form the remaining forest Other studies supportthese propositions In the study area for example Rosero et

Fig 4 ndashEffect of the length (in years) of PES contracts onagricultural land cover

Table 2 ndash Results of Model 1

Model 1 A B C D E F

Primary forest Intervenedforest

Total forest(Pri+Int)

Charral Agriculture Totaltransformed(Ag+Ch)

Factors B t Sig B t Sig B t Sig B t Sig B t Sig B t Sig(Constant) 142 016 064 053 137 018 056 058 362 000 278 001Conversion costs

(ConverCosts)028 194 006 007 047 064 035 257 001 017 118 024 025 198 005 028 218 003

Transportation costs(TransportCosts)

023 168 010 006 043 067 028 218 003 010 068 050 036 302 000 034 250 002

PES 025 188 007 022 155 013 008 061 055 039 288 001 018 153 013 007 055 058

139E C O L O G I C A L E C O N O M I C S 5 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 1 3 1 1 4 1

al (2002) show the role of transportation costs in thedecision to clear a forest plot They demonstrated that theprobability of forest clearing decreases from 30 for forestslocated less than 1 km from a road to 9 for land locatedbetween 5 9 km Empirical work by Kinnaird et al (2003) inSumatra illustrate the local interactions They showed thatforests on flat slopes disappeared 16 times faster than foreston steep slopes Timber harvest in areas with steep slopescan be especially problematic due to the legal hurdles addedtime and heavier equipment needed to cut and extract treesmaking it an expensive proposition and relatively lessprofitable endeavor

As expected the role of PES relative to other factors on landcover characteristics is more evident in the area under charral(Model 1d) This supports the conclusion of the importance ofthe payments for farmers seeking to abandon agriculture toengage in more desirable productive activities In our conversations with land owners nearly all of them said to bedeveloping alternative income generating activities that couldsustain them even beyond the term of their contracts In somecases these were said to be financed by the PES but ourfindings suggest that it is a common process A morecommonly stated objective was to move to the regionstowns and engage in ldquourbanrdquo work such as driving taxisretailing or in tourism A few landowners said that they usedthe payments to expand or improve agricultural activities (egbuy cattle) but since our analysis suggests that agriculture isabandoned in PES farms it could be assumed thatmuch of thisinvestment takes place in other possibly Non PES farmsIndeed some landholders in this study reported moving theircattle to better drained more fertile soils in the flatter regionsof the peninsula

7 Final comments conservation and policyimplications

Despite the small sample size this study strongly points to acritical land use mechanism arising from the application ofPES in the Osa Peninsula and offers important insights forpolicy design PES are a potentially efficient mechanism toachieve the conservation of forest habitats and the servicesthey provide as they do affect land use decisions agriculturalland is abandoned by landholders who use the payments ascapital to engage in other (often urban) productive activitiesand forest cover is maintained or let increase However

because the existing forest area would not have changedwithout the payments any additional gain would be from thenew forest growing in previous agricultural and charral areas

These findings suggest that there are three conditions thatdetermine the level efficiency of PES

1) whether forest cover would be lower without thepayments

2) whether any additional gain in forest cover is temporary orpermanent and

3) whether the protection of some forest habitats in a farmcreates pressure in other habitats maybe biologically andeconomically more important in the same farm orelsewhere

Our findings suggest that PES in the Osa Peninsula may beinefficient on the account of factors 1 and 2 but possibly noton 3 The fact that there seems to be generalized tendency toabandon agriculture in the Osa Peninsula suggests that asimilar land cover outcome could probably be achieved in themedium to long run without payments Farms farther awayfrom markets and with higher costs due to local conditionswould show the greatest gains Furthermore because conservation contracts do not apply to forest cover gained there isno long term guarantee that it would be permanent Becausethe costs of recovering an agricultural area that has beenabandoned increases with time there is pressure on the part ofthe farmer to keep fallows as short as possible For exampleonce the trunks of emergent trees in a secondary forest areareach 10 cm in diameter it is not onlymore expensive to be cutbut it is also protected by law A recent report (SINAC 2002)revealed that landholders regularly cut back fallow areas inorder to maintain them as pasture

Even if the new forest cover was permanent the marginalgain of every hectare of forest created by PES would have to becompared with the value in services that could be potentiallyobtained if invested in another critical area both in the sameregion or elsewhere This is particularly important in thosecases in which the local benefits will be accrued with asignificant lag In this case the gain may be less than themarginal loss of not protecting existing habitats somewhereelse because the restoration of tropical humid forests maytake several decades

Notwithstanding this long term concern this study pointsto the potential value of committing conservation resources todegraded areas and the apparent capability of PES to affect

140 E C O L O G I C A L E C O N O M I C S 5 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 1 3 1 1 4 1

these results Currently most PES programs cannot be appliedto non forest lands Standards set by a recent GEF grant andWorld Bank loan to Costa Rica for example require that thesefunds exclusively target areas that are already under secondary or primary forest but not agricultural or pasture fieldsThis policy shift is attributable to the general understandingamong foresters that forest regeneration is not important toforest management objectives and the recognition thatpriorities should be set However while this approach mayensure that available funding targets forested areas moreefficient opportunities for forest re conversion may be missedin areas where forest cover is relatively stable but insufficientThe restoration of forest ecosystems could play a critical rolein planning and programs of government agencies and nongovernmental organizations This would also help to counteract the declining opportunities for conservation of naturalareas (Meffe and Carroll 1997) Indeed outside of the PESdebate restoration is slowly but surely making its way intomainstream conservation discourse

Finally the implication of the third condition stated aboveis that in the short term effectiveness of PES is directly relatedto the targeting of high risk habitats This speaks to thefinancial and environmental cost efficiency of PES programsand the importance of using spatial prioritization mechanisms based on land cover change risk assessments Anopportunistic approach in PES contracts does not distinguishbetween landholderswhowant payments and those that needthem In the specific case of forest habitats in the OsaPeninsula the regional targeting system which FONAFIFOcurrently uses enables PES managers to select farms that areimportant to regional conservation objectives However byawarding PES to protect forest based on a ldquofirst come firstserverdquo the current selection does not counter the immediatethreats that are driven by underlying land use changeprocesses Indeed anecdotal information collected duringthis study suggests that the farmers who came first to requestPES coverage were those who were more familiar with theforest engineers in charge of promoting the program and withforestry related subsidies and other options Techniquescurrently used to prioritize conservation decisions could easilybe assembled to assist PES administrators with the task ofsetting socially acceptable and privately optimal pricesaccording to spatial and land feature characteristics Studiesin Costa Rica Peru and Ecuador show the effectiveness ofthese approaches to measure the relative conservation risk ofvarious habitats and regions (eg Barton et al 2004 Rodriguezand Young 2000 Sierra et al 2002 respectively) Programsshould focus on habitats that are at greatest risk In the case ofCosta Rica the fact that demand (farmers seeking PEScompensation) far outweighs supply (FONAFIFO funding tocompensate landholders) suggests that many landholdersreceiving payments would still conserve their forest even iflower compensation amounts were offered Rojas and Aylward (2003) suggest considering auctions for PES By auctioning to the lowest bidder a higher area could be conservedHowever if farms were selected based on the lowest bid thenthey may still not target priority areas based on risk wherehigher pricesmight be required to lure land holders away fromforest conversion and extraction activities The main point oftheir argument however is not lost The system could allow

for a variable price or possibly the unbundling of compensation payments to more accurately reflect an equilibriumbetween the value of protecting the pubic good and thereward necessary to compensate land users for lost revenueVariable pricingmechanisms could bemademore plausible byemploying spatial modeling economic indicators and ecological priorization to optimize the prices of PES contractofferings The optimal price for PES should just meet theoptimal expectation of the buyers and sellers of environmental services but should also reflect the environmental orconservation risk of a given habitat

R E F E R E N C E S

Alix J A de Janvry and E Sadoulet 2003 Payments forenvironmental services to whom where and how muchPaper presented at Workshop on Payment for EnvironmentalServices Guadalajar Mexico INECONAFORWorld Bank

Angelsen A Kaimowitz D 2003 Rethinking the causes ofdeforestation lessons from economic models TheWorld BankResearch Observer 14 (1) 73 98

Barrantes B Jimenez Q Lobo J Quesada M Quesada R 1999Manejo Forestal y Realidad Nacional en la Peninsula de OsaSan Jose The Cecropia Foundation Costa Rica

Barton D Faith D Rusch G Ove Gjershaug J Castro MVega E 2004 Spatial prioritisation of environmental servicepayments for biodiversity protection Costa Rica NorwegianInstitute for Nature Research (NIVA) Instituto Nacional eBiodiversidad (INBio)

Brockett C Gottfired R 2002 State policies and the preservationof forest cover lessons from contrasting public policy regimesin Costa Rica Latin American Research Review 37 (1) 7 40

Carey P Short C Morris C Hunt J Davis M Finch CCurry N Little W Winter M Parkin A Firbank L 2003 Themulti disciplinary evaluation of a national agri environmentscheme Journal of Environmental Management 69 71 91

Chomitz K Brenes E Constantino L 1999 Financing environmental services the Costa Rican experience and its implications The Science of the Total Environment 240 157 169

Clark D Downes D 1999 What price biodiversity Economicincentives and biodiversity conservation in the United StatesCenter for International Environmental Law Washington DC

Daley H Farley J 2004 Ecological Economics Principles andApplications Island Press Washington DC

Faith P Walker P 2002 The role of trade offs in biodiversityconservation planning linking local management regionalplanning and global conservation efforts Journal of Biosciences 27 393 407

Ferraro P Kiss A 2002 Direct payments to conserve biodiversityScience 298 1718 1719

Ferraro P Simpson D 2002 The cost effectiveness of conservation payments Land Economics 78 (3) 339 353

Grubb M 1999 The Kyoto Protocol a Guide and AssessmentRoyal Institute of International Affairs London

Hoekstra M Boucher T Ricketts T Roberts C 2005Confronting a biome crisis global disparities of habitat lossand protection Ecology Letters 8 (1) 23 29

Ives A Cardinale B Snyder W 2005 A synthesis of subdisciplines predator prey interactions and biodiversity and ecosystem functioning Ecology Letters 8 (1) 102 116

Kappelle M Castro M Acevedo H Gonzalez L Monge H2003 Ecosystems of the Osa conservation area SantoDomngo de Heredia Costa Rica Instituto Nacional deBiodiversidad INBio

Kinnaird M Sanderson E OBrien T Wibisono H Woolmer G2003 Deforestation trends in a tropical landscape and

141E C O L O G I C A L E C O N O M I C S 5 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 1 3 1 ndash 1 4 1

implications for endangered large mammals ConservationBiology 17 (1) 1523ndash1739

Landell-Mills N 2002 Marketing forest services Who benefitsLondon International Institute for Environment and Develop-ment Gatekeeper Series 104

Landell-Mills N Porras I 2002 Silver bullet or fools gold Aglobal review of markets for forest environmental services andtheir impact on the poor Instruments for Sustainable PrivateSector Forestry Series International Institute for Environmentand Development London

Meffe G Carroll C 1997 Principles of Conservation Biology 2nded Mass Sinauer Sunderland

Moura Costa P Stuart M Pinard M Phillips G 2000 Elementsof a certification for forestry-based carbon offset projectsMitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 539ndash50

Nasi R Wunder S Campos J 2002 Forest ecosystem servicescan they pay our way out of deforestation Forestry Round-table Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) UNFFI Costa Rica

OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation andDevelopment) 1997 The Environmental effects of AgricultureLand Diversion Schemes OECD Paris

Ortiz E 2004 Efectividad del Programa de Pago de ServiciosAmbientales por Proteccioacuten del Bosque (PSA-Proteccioacuten)como instrumento para mejorar la calidad de vida de losproprietarios de bosques en las zonas rurales Kuru RevistaForestal 1(2) (Available at wwwitcraccrescuelasforestalhtmrevistaKuruindexhtm)

Ortiz E Sage L Carvajal B 2003 Impacto Del Programa de Pagode Servicios Ambientales en Costa Rica como medio deReduccion de la Pobreza en los Medios Rurales San Jose CostaRica Unidad Regional de Asistencia Tecnica (RUTA)

Pagiola S 2002 Paying for water services in Central America InPagiola S Bishop J Landell-Mills N (Eds) Selling ForestEnvironmental Services Market-Based Mechanisms for Con-servation and Development VA Earthscan PublicationsLondon Sterling

Pfaff A 1999 What drives deforestation in the Brazilian AmazonEvidence from satellite and socioeconomic data Journal ofEnvironmental Economics and Management 37 26ndash37

Rice R 2004 Conservation incentive agreements an opportunityand a challenge for biodiversity conservation in the tropicsPaper presented at the Fifth Annual Ecological IntegrationSymposium demonstrating ecological value promoting con-servation and sustainability Texas A and M University

Richards M 2000 Can sustainable tropical forestry be madeprofitable The potential and limitations of innovative incen-tive mechanisms World Development 28 (6) 1001ndash1016

Rodriguez L Young K 2000 Biological diversity of Perudetermining conservation areas for conservation Ambio 29 (6)329ndash337

Rojas M Aylward B 2003 What are we learning from marketsfor environmental services A review and critique of theliterature CREED Working Paper IIED London

Rosero L Maldonado-Ulloa T Bonilla-Carrio R 2002 Bosque yPoblacion en la Peninsula de Osa Costa Rica Revista BiologiaTropical 50 (2) 585ndash598

Sader S Joyce A 1998 Deforestation rates and trends in CostaRica 1940ndash1983 Biotropica 20 11ndash19

Sanchez A Harriss R Storrier L de Camino-Beck T 2002aWater resources and region land cover change in Costa Ricaimpacts and economics Water Resources Development 18 (3)409ndash424

Sanchez G Rivard B Calvo J Moorthy I 2002b Dynamics oftropical deforestation around national parks remote sensingof forest change on the Osa Peninsula of Costa Rica MountainResearch and Development 22 (4) 352ndash358

Sanchez A Daily G Pfaff A Busch C 2003 Integrity andisolation of Costa Ricas national parks and biological reservesexamining the dynamics of land-cover change BiologicalConservation 109 123ndash135

Schelhas John 1995 Partnership between rural people andprotected areas understanding land use and natural resourcedecisions In McNeely J (Ed) Expanding Partnerships inConservation International Union for Conservation of Natureand Natural Resources Island Press Washington DC

Shrestha R Timilsnia G 2002 The additionality criterion foridentifying clean development mechanism projects under theKyoto Protocol Energy Policy 30 73ndash79

Sierra R 2001 The role of domestic timber markets in tropicaldeforestation and forest degradation in Ecuador Implicationsfor conservation planning and policy Ecological Economics 36(2) 327ndash340

Sierra R 2005 From national to global planning for biodiversityconservation Examining the regional efficiency of nationalprotected area networks in the tropical Andes In Zimmerer K(Ed) Geographies of Environmental Management and Globa-lization Expanding Dimensions and Dilemmas University ofChicago Press Chicago

Sierra R Campos F Chamberlin J 2002 Assessing biodiversityconservation priorities ecosystem risk and representativenessin continental Ecuador Landscape and Urban Planning 5995ndash110

Simberloff D Doak D Groom M Trombulak S Dobson AGatewood S Soule M Gilpin M Martinez del Rio C Mills L1999 Regional and continental restoration In Souleacute MTerborgh J (Eds) Continental Conservation Scientific Foun-dations of Regional Reserve Networks Island Press Washing-ton DC

SINAC (Sistema Nacional de Areas de Conservacion) 2002 Mitos yRealidad de la Deforestacioacuten en Costa Rica MINAE San JoseCosta Rica

Souleacute M Terborgh J 1999 Continental Conservation ScientificFoundations of Regional Reserve Networks Island PressWashington DC

World Bank 2000 Project appraisal document on a proposed IBRDloan of $32 Million and a grant from the Global EnvironmentFacility Trust Fund of SDR 61million ($8million equivalent) tothe government of Costa Rica for the EcoMarkets Project20434-CR Latin America and the Caribbean Regional Office

132 E C O L O G I C A L E C O N O M I C S 5 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 1 3 1 1 4 1

greatest This concern is motivated in large part by thedecline in international funding for conservation during thepast decade but also by a greater awareness that certainhabitats face greater risk than others (Sierra et al 2002 Sierra2005) It is no longer acceptable to expend resources in anopportunistic manner as has typically been the case Theexpectation is that available resources are used to protectcritical ecosystems first

A growing body of research also suggests that maintainingecological services demands strict large scale protection ofentire ecosystems beyond the boundaries of protected areas(Meffe and Carroll 1997 Simberloff et al 1999 Souleacute andTerborgh 1999) Today most remaining natural habitats areon private hands either individually or communally and it isunlikely that sufficient amounts of these lands will ever beincluded under protected management domains due topolitical economic and cultural factors Unfortunately command and control conservation mechanisms (ie laws andregulations) have proven ineffective in these areas especiallyin the developing world (Sierra 2001 Faith and Walker 2002)The most common alternative has been the implementationof programs designed to redirect labor and capital away fromactivities that degrade ecosystems and cause biodiversity lossThis approach often called integrated conservation anddevelopment programs has been labeled ldquoindirectrdquo by scholars of market based conservation Billions of dollars wereinvested in such endeavors in the 1980s and 1990s (Ferraroand Simpson 2002 Landell Mills 2002) However by the mid1990s the initial optimism had cooled to cautious interestThough some projects were having noticeable effects (Schelhas 1995) observers concluded that most interventions hadfailed or were failing Rice (2004) labeled this approachldquoconservation by distractionrdquo Studies showed that the barriers to change were much too complex (Ferraro and Kiss2002) Even when conservation projects were able to changelocal resource use strategies in the short term interventionsrarely altered the incentives that prompted local resourceusers to degrade habitats in the first place Because marketsoffer no compensation for protecting natural habitats landowners have no incentives to conserve them favoring theirtransformation to agriculture or intensive resource extraction(eg logging) This results in the loss of the services and goodsof great social but relatively small private value that theyprovide In this tragedy of the private lands including thosecontrolled as community territories land owners bear thewhole cost of conservationwhilemanymore share its benefitswithout compensating them

Recognizing these shortcomings some analysts and conservation practitioners are recommending to compensateland owners directly for the economic losses associated withhabitat conservation with payments that correspond to thegain in services kept (Alix et al 2003 Pagiola 2002) In theideal system the provision of services would be negotiated byusers and producers (ie owners of the habitats where theprocesses take place) through market transactions Howeverthis transition requires that markets be created where noneexisted before not an easy task given the nature of theservices involved Many experiments with this conservationmodel are now being conducted on the supply side of theequation in the form of PES By the 1990s there were close to

300 related initiatives planned or in the early stages ofimplementation (Landell Mills and Porras 2002) many indeveloping countries For example Mexico is implementing anationwide PES scheme to address their perceived deforestation problem (Alix et al 2003) Organizations such asConservation International which just a few years ago hadno experience in direct market transactions now havemillions of dollars tied up in contracts protecting importantecosystems

There are however important gaps in our understandingof the way PES work and their relative and absolute contribution to conservation A key unknown is how much additionalconservation is obtained through PES a concept often referredto as additionality Additionality simply means that theoutcomes of a policy or project are in addition to what mighthave occurred due to other direct and indirect factors(Shrestha and Timilsnia 2002) or in this case in the absenceof payments A second question relates to the multi scalenature of conservation priorities and the potential for in farmand off farm leakages Land use decisions are complex andsimultaneous It is not well known how payments are used byrecipients and how these decisions indirectly contribute to orsubtract from the overall impacts of PES Farmers may usepayments for example to transfer farming activities to otherforest areas not covered by PES in the same region or even inthe same farm They may even be used to increase thepressure on more critical ecosystems or for intensifyingexisting productive activities with relatively greater environmental impacts

Unfortunately until now there has been limited empiricalresearch linking land use decisions and ecosystem protectionand restoration to PES programs Project reports show the sizeand location of lands set aside for PES contracts but it is oftenunclear if the new conservation area is additional to whatmight have been conserved in the absence of conservationpayments A recent study of the Countryside StewardshipScheme in England determined for example that between36 and 38 of agreements showed some level of additionality and concluded that the program is likely to provide abenefit to society (Carey et al 2003) However this analysiswas based on the farmers perception of the impact of a signedagreement and not on land cover outcomes Similarly anattitudinal study in Costa Rica showed that PES farmersoverwhelmingly believed that this countrys program wascontributing to the protection and restoration of tropicalforests (Ortiz 2004) Forty three percent of landholders saidthey had abandoned agriculture and pasture fields whenoffered the PES option On the other hand recent nationwideland cover studies demonstrate that secondary forestincreased at a rate of 13000 ha per year from 1987 to 1997due in part to a series of environmental and economic factorsthat affected the value of cattle and agricultural production(World Bank 2000) Hence it remains unclear if landmanagerswithout payments were also abandoning agriculture in thesame way as a result of other relevant forces

Within this context this study examines the PES programin theOsa Peninsula Costa Rica Costa Rica is often cited in theliterature as a pioneer in market based conservation initiatives (Chomitz et al 1999 Pagiola 2002) Nearly all sectors ofsociety have embraced the PES concept and are actively

133E C O L O G I C A L E C O N O M I C S 5 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 1 3 1 1 4 1

lobbying for increased funding to make it available to morelandholders (Barrantes et al 1999 Brockett and Gottfired2002 Sanchez et al 2002a) Costa Rica therefore providesfertile ground to research how PES programs work to protectand restore ecological services in private lands Specificallyour analysis responds to three questions 1) Are land usedecisions of landholders of PES and non PES farms different2) If different what role PES relative to other factors play inexplaining this variation And 3)What are the in farm and offfarm conservation implications of PES in the Osa PeninsulaOur analysis assumes that land use decisions are reflected inland cover characteristics and that these in turn manifesthow payments work for conservation This approach has theadvantage that land cover is relatively easy to be quantifiedand subsequently associated with key factors that areexpected to play a determining role in land use decisions

2 Conserving biodiversity and ecosystemservices in privately owned lands

There is a long history of programs designed to pay landowners directly to encourage particular land managementpractices to promote the conservation of specific physicalresources or in some important cases to maintain commodity prices For example charging water users to compensateupstream land owners has been used successfully in Japan forover 100 years (Richards 2000) In developed countriesgovernment agencies have provided for decades financialincentives to farmers to keep agricultural land out of production or shift it to alternative uses In Europe 14 countries spentan estimated $11 billion between 1993 and 1997 to divert over20million ha into long term forestry contracts (OECD 1997) Inthe 1990s the United States Conservation Reserve Programspent about $15 billion annually on contracts for 12 15millionha (Clark and Downes 1999) an area twice the size of CostaRica

Land owners participating in PES programs also agree toapply specific conservation schemes in their lands for a givenperiod of time in exchange for a payment However the mainobjective of PES programs is to promote the conservation ofecological processes Although subtle this difference issignificant Resources such as water and soils can be storedand their use by third parties restricted These are usuallyconceived as local assets not connected to other areas orregions In contrast ecological processes are a fund serviceproperty of biodiversity They cannot be stored and are nonexclusionary (Daley and Farley 2004) Owners of the habitatswhere these take place who do not capture their value nowincur in a permanent loss Furthermore they cannot impedethat other users locally or globally benefit from themwithoutcompensation Indeed their value is often based on the rolethey play in determining natural economic and socialconditions in places that are often far removed from wherethey take place PES programs are an attempt to link thisspatially disjunct value system through the creation of quasimarkets for environmental services based on subsidiesprovided by conservation agencies multilateral organizationsand governments PES programs are expected to be anintermediary stage in the formation of true markets for

environmental services in which beneficiaries of the servicesand goods provided by specific habitats would pay landowners for their conservation

To facilitate the development of markets and the interaction of providers and buyers researchers have been trying toqualify and quantify the value of ecosystem services This isproving difficult because we still know so little about thespecific services ecosystems provide In fact different economic valuation techniques often generate quite distinctresults (Nasi et al 2002) Consequently researchers arefinding that valuation efforts can contribute most by determining how much one would have to pay different groups toget them to maintain land under natural cover (ie theirwillingness to accept) rather than the value of the serviceHowever this proxy approach has important drawbacksbecause of the complexity and simultaneity of land usedecisions Specifically it is difficult to disentangle decisionsabout natural habitat (eg forest) use from decisions aboutagricultural investment It should be expected that given a setof initial conditions land labor capital and technologylandholders simultaneously allocate multiple resources tomaximize production andminimize risk For a landholder theopportunity cost of a habitat fragment in his or her land maybe positive but if a payment is sufficiently high farmers maybe willing to accept it to dump other activities with lower orequal value even before they consider natural habitats Infact the opportunity cost of a habitat may be so low thatlandholders may leave a habitat untouched even without apayment incentive As long as a payment is equal or greater toany land use alternative landholders are likely to accept itfreeing the resources that are tied into that activity (eg labor)and allocating them to the next best alternative In this casePES may be subsidizing the productive activities of landholders and not hisher conservation activities This issue isespecially problematic because currently most PES programsincluding in Costa Rica select landholders on a first comefirst served basis as well as on the lobbying power ofinterested NGOs and landowners (Barton et al 2004) Thisapproach may lead to an over subscription to the program orthe unintended inclusion of owners seeking to dump otheractivities with a value lower than the payment and theexclusion of critical habitats

There is also the difficulty of adapting payments to thespatial variability of both the value of the service and the riskof service loss Some habitats are more valuable than othersbecause the benefit that users obtain from the services theygenerate is greater and some are more valuable because therisk of losing them locally regionally or globally is higher orboth This variability of the value of the conservation ofhabitats at regional and global scales points to the need toframe the analysis of PES efficiency as a multi scale issue Todetermine additionality researchers must first establishbaseline scenarios and understand how other factors affecthabitat cover change in an area and its relation to the overall(eg regional) conservation priorities These scenariosbroadly described are the collective set of economic financialregulatory and political circumstances within which land usedecisions operate (Moura Costa et al 2000) and the relativeglobal and regional risk of biodiversity and ecological serviceloss A PES program may be successful at a local scale but

134 E C O L O G I C A L E C O N O M I C S 5 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 1 3 1 1 4 1

inefficient at a regional or even global scale (but it cannot beregionally efficient if it is not locally successful) This wouldoccur if local conservation takes place at the expense of theconservation of more critical habitats and their services inother areas This of course does not take into account theexistence and evolutionary value of biodiversity Currentexperiments do not address these issues yet Ultimately theefficiency of PES rests on the additional contribution toconservation they provide (Shrestha and Timilsnia 2002)

3 PES in Costa Rica

The addition of conservation payments to the conservationarsenal has been warmly received in Costa Rica as evidencedby the fact that the countrys PES program has attracted fivetimes more applicants than it can pay for (Pagiola 2002)Government and civil society also see them as a way to meetthe countrys objective of protecting biodiversity Costa Ricasfirst effort to use economic instruments dates back to 1979when the first Forestry Law established tax based incentivesThese had limited effect since few landholders had land titlesand thus paid property taxes Subsequent laws were intendedto increase accessibility of small rural landholders In 1986 theCertificados de Abonos Forestales (CAF) provided tax exemptionsduring the first five years of reforestation up to the amount ofthe total costs However CAF did little to prevent logging ofprimary forest or as effective stimulants for reforestation(Ortiz 2004) This program also created distortions thatfavored plantation forests over natural forest which usuallyprovide greater service value andwas finally cancelled in 1995(World Bank 2000 Rojas and Aylward 2003)

In 1996 Forestry Law 7575 introduced the current PESsystem By this time Costa Rica already had in place anelaborate system of payments for reforestation and forestmanagement and the institutions to manage it (Rojas andAylward 2003) The law provides the legal and regulatory basisto contract with land owners for the environmental servicesprovided by their lands empowers the National ForestryFinancing Fund (FONAFIFO) to issue such contracts andestablishes a financing mechanism for this purpose Thefour environmental services recognized by the new forest lawinclude 1) mitigation of green house gas emissions 2)hydrological services including provision of water forhuman consumption irrigation and energy production 3)biodiversity conservation and 4) provision of scenic beauty forrecreation and ecotourism PES are expected to provide theseservices by protecting primary forest allowing secondaryforest to flourish and expanding forest cover though plantations These goals are met through site specific contracts withindividual small and medium sized farmers In all casesparticipants must present a sustainable forest managementplan certified by a licensed forester as well as carry outconservation or sustainable forest management activitiesDifferent compensation amounts and contract durations areprovided for 1) forest protection (5 year duration and $210 perhectare dispersed over 5 years) 2) sustainable forest management (15 year duration and $327 per hectare dispersed overfive years) and 3) reforestation activities (15 to 20 yearduration and $537 per hectare dispersed over five years)

Differences reflect the relative cost associated with eachactivity Forest protection receives the lowest paymentbecause there is relatively little overhead Sustainable forestmanagement receives more to cover the cost of designing andimplementing a sustainable harvest Reforestation receivesthe highest compensation in order to cover the high cost ofplanting and maintaining tree plantations The $42ha peryear paid for forest protection reflects the loss of revenue thatlandholders would earn if their forest were converted topastures or other land uses (Ortiz et al 2003) Between 1997and 2003 more than 375000 ha had been included in almost5500 PES contracts with a total cost of $962 million Almost87 of this area was under forest protection contracts (Ortiz2004)

One of the main initial concerns was how to fund CostaRicas PES program In 1997 the Kyoto Protocols concept ofJoint Implementation (JI) offered an opportunity to overcomethis barrier JI is a mechanism whereby a donor countrycontributes to the implementation of pollution abatementmeasures in a host country in return for credits to meet itsown pollution abatement obligations While it was initiallyseverely criticized by nearly all developing countries (Grubb1999) Costa Rica supported it and immediately set up theCosta Rican Office on Joint Implementation (Oficina Costarricense de Implementacioacuten Conjunta or OCIC) to attract funding(Rojas and Aylward 2003) Expectations that Costa Ricasexperiment with PES would attract large amounts of outsidefinancial support were high from the start The Costa Ricanlegislature authorized the Ministry of the Environment to findinternational partners for the PES program so that the cost ofproducing environmental services like CO2 reduction could beshared with the international community By 2003 theprogram was primarily financed by fuel taxes (Ortiz et al2003) However a World Bank loan and a GEF grant wereneeded to meet expected PES shortfalls until the year 2005(Rojas and Aylward 2003) Fortunately for advocates of PESprograms opportunities for international cooperation appearto be increasing

4 Data

Farm level payment and land cover data for this study waspooled from four sources 1) a list of PES beneficiaries from theFondo Nacional de Financiamiento Forestal (FONAFIFO) 2)archival research in the offices of the Ministry of theEnvironment and Energy in Puerto Jimenez 3) a recent landtenure land use study by Centro de Derecho Ambiental y deRecursos Naturales (CEDARENA) and 4) personal interviewsconducted by the second author on the Osa Peninsula duringJuly and August 2003 Additional information for modelimplementation was obtained from official cartographic datafor farms infrastructure rivers and terrain

The initial database included 61 farms receiving PES forforest protection and 585 non PES farms Other type of PEScontracts were not included in this analysis Both PES andNon PES farms were georeferenced and digitized by CEDARENA and FONAFIFO All the farms below 30 and above 350 hawere eliminated from both samples The lower threshold isthe minimum size that was considered consistent with the

135E C O L O G I C A L E C O N O M I C S 5 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 1 3 1 1 4 1

level of cartographic detail used in this study to generatespatial data for model implementation The upper thresholdcorresponds roughly to the largest area that could be placedunder PES contract in any given farm1 Thirty PES farms metthis criteria This is equivalent to approximately 1 of every 6PES farms in the Osa Peninsula2 Thirty non PES farms wereselected randomly from the non PES set that met the samecriteria for comparison (Fig 1)

Farm level land cover characteristics measured aspercent of a farms area were extracted from field surveysfor the following classes 1) agriculture 2) charral 3)intervened forest and 4) primary forest (Fig 2) Each classrepresents distinctive land use conditions recognized bylocal forest engineers and landholders The agriculture classincludes pasture agricultural fields fruit orchards andAfrican palm plantations Charral corresponds to abandonedor fallow agricultural areas for 2 7 years that are in theprocess of early secondary succession Charral areas havedense undergrowth and occasional emergent trees but arestill lacking substantial qualities to be considered secondaryforest Intervened forests have observable signs of humanintervention These were usually managed for timberextraction in the past one to two decades or are the resultof late secondary succession where pastures and agriculturalfields have been abandoned for over a decade Primaryforests are closed canopy forest with relatively little humanintervention

5 Group comparison and model specification

Land use decisions of landholders of PES and non PES farmswere assessed based on the land cover characteristics of eachfarm for each of the four land cover types described aboveTheir land cover characteristics were compared using analysisof variance (ANOVA) for the total sample and subsets of PESfarms based on the length of time that the contracts had beenin place

The role of PES relative to other factors was examinedthrough an set of OLS regression models that explainvariations in land cover as a function of PES incentives andproxy measures for regional and local costs of agriculturalproduction The general model is specified as

LndCov athorn a1TransportCostthorn a2ConvertCostthorn a3PES eth1THORN