Nature, nationalism and revolutionary regionalism: constructing Soviet Karelia, 1920–1923

-

Upload

nottingham -

Category

Documents

-

view

5 -

download

0

Transcript of Nature, nationalism and revolutionary regionalism: constructing Soviet Karelia, 1920–1923

Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595www.elsevier.com/locate/jhg

Nature, nationalism and revolutionary regionalism:constructing Soviet Karelia, 1920e1923

Nick Baron

School of History, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK

Abstract

Russian Karelia was for the first time in its history united into a single administrative unit on 7 June1920. The lack of precise directives as to the new region’s purpose, administrative status and territorywas a measure of the contradictions, conflicting aspirations and countervailing tensions of ideology andexigency inherent in Soviet state-building. On the basis of extensive archival research, this paper considersthe ideas and motivations which resulted in the establishment of Soviet Karelia and the subsequent strug-gles to delineate its regional borders. It aims to elucidate how different actors at the centre and in thelocality envisioned the construction of regional space. Underlying the political conflicts surrounding thedrawing of Karelia’s borders, and giving shape to the diverse prescriptions for regional territorial structure,were differing assumptions and beliefs about post-revolutionary spatial transformation, dissonant concep-tions of ‘nature’ and ‘nation’, and divergent understandings of the role and locus of social agency inhistorical change. By addressing these themes, the paper seeks to contribute to a better understanding ofearly Soviet history and geography, and to the comparative and theoretical study of nationalism, region-alism and the spatial dimensions of political ideology and practice.� 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Soviet Union; Karelia; Regionalism; Nationalism; Space; Borders

Introduction

For the first time in its history, Russian Karelia was constituted as a unified territorial unit on 7June 1920. The following day, Vladimir Lenin’s Soviet government, the All-Russian Central

E-mail address: [email protected]

0305-7488/$ - see front matter � 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2006.10.021

566 N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

Executive Committee (VTsIK), issued a resolution stating that ‘to fight for the social emancipa-tion of the Karelian workers’ a ‘regional unit’ (oblastnoe ob’edinenie) to be named the KarelianLabour Commune (Karel’skaia Trudovaia Kommuna, KTK) should be formed in the areas of Olo-nets and Arkhangel’sk provinces ( gubernii) populated by Karelians.1 This proclamation’s lack ofprecise directives concerning the new region’s administrative status, political purpose, economicrole and territorial boundaries was a measure of the contradictions, conflicting aspirations andcountervailing tensions of ideology and exigency inherent in early Soviet state-building.

This paper examines in detail the origins of Soviet Karelia’s territorial formation, and the sub-sequent struggle to define its regional borders. In so doing, it aims to elucidate how central impro-visation of policy, responding selectively to the plans and appeals of peripheral and grass-rootsinterests, shaped Soviet Russia’s reconstruction of regional space. Underlying and giving shapeto these diverse prescriptions for Karelia’s territorial structure were differing visions, in both cen-tre and periphery, of post-revolutionary spatial organisation, dissonant conceptions of ‘nature’and ‘nation’, and divergent understandings of the role and locus of social agency in historicalchange. The first section of the paper seeks to explicate and contextualise these conceptual issues.I then consider how nationalist, revolutionary, diplomatic and strategic motives intersected toproduce the Karelian ‘regional unit’. The third section examines the bitter conflicts which its cre-ation generated among opposed regional interests, manifested most forcefully in the process ofregional boundary-drawing. These debates on the principles and practices of post-imperial,post-revolutionary spatial transformation give the historian insight into some of the ambiguitiesand tensions within the Bolshevik project, and, more generally, elucidate the spatial dimensions ofstate-construction, region-formation and nation-building. At a theoretical level, this paper alsooffers a reflection on both the spatial attributes of political agency and the ideological co-ordi-nates of space, and explores the theoretical premise which constitutes the foundation and motiva-tion of this study: that of the ‘region’ as an ‘historically contingent’ actualisation of discoursesarbitrated by power.2

The nature of revolutionary space

In the conception of its leaders, the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 was to inaugurate not merelya transition from one political system to another but a fundamental transformation of the condi-tions and structures of social life. As Marxists, they understood revolution as an emancipatoryproject which aimed to overcome the alienation of the individual from nature generated by privateproperty, wage servitude and modern industrial processes. Revolution was the first step towardsresolving the dialectical conflict between social relations of production and forces of production,

1 Resolution published in Sobranie uzakonenii i rasporiazhenii rabochego i krest’ianskogo pravitel’stva RSFSR 53(1920), Art. 232.

2 A. Pred, Place as historically contingent process: structuration and the time-geography of becoming places, Annalsof the Association of American Geographers 74 (1984) 279e297. See also A. Paasi, The institutionalization of regions:a theoretical framework for understanding the emergence of regions and the constitution of regional identity, Fennia

164 (1986) 105e146; A. Paasi, Deconstructing regions: notes on the scales of spatial life, Environment and PlanningA 23 (1991) 239e256; R.J. Johnston, A Question of Place: Explaining the Practice of Human Geography, Oxford, 1991.

567N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

including those relations and forces embodied in human nature and embedded in the natural en-vironment, that had hitherto driven historical progress.3 Whereas capitalism had been a ‘factoryof fragmentation’, communism would reintegrate society in a new, creative relationship with thephysical world, bringing about a reconciliation between humanity’s ‘internal’ and ‘external’nature.4

Although neither Marx nor Lenin had explicitly theorized the status or role of space in histor-ical evolution, their thinking was nevertheless profoundly spatial. Each successive mode of pro-duction in social development was characterised by a particular configuration of space and setof spatial relations, wherein space was both a dimension of the physical environment and sociallyconstructed e the dynamic actualisation of both material forces and imagined structures. Space,in this account, both mediated and articulated the evolving relationship between nature and soci-ety. Spatial emancipation was therefore an inseparable part of the Bolshevik project in a twofoldsense: freeing the innate productive energies of space from the suffocating feudal superstructure ofthe old regime, and freeing the productive forces of society from bondage to these obsolete spatialstructures. As post-revolutionary society progressively attuned itself to a ‘humanised’ nature, sospace itself would be ‘naturalised’.5 Communism ultimately would dissolve ‘historical’ time into‘natural’ space. What remained indeterminate in Bolshevik thinking, however, was how to reach,and then to recognise, this moment. Implicit in early Soviet debates about regionalisation andboundary-drawing, as we shall discuss below, were different ontologies and epistemologies of‘naturalised’ space.

Spatial emancipation was both a local and a global project, though ultimately it was to tran-scend and subsume scale.6 In the Marxist account, capitalist development had already set inmotion a dynamic of territorial dissolution: ‘In place of the old local and national seclusionand self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal inter-dependence of na-tions’.7 Capitalism’s impulse towards spatial unification and homogenisation, however, co-existedwith a countervailing urge to repartition and diversify space, to create, commodify, centralise andcontrol new territorial units. Its relationship with the nation-state was a function of this dialectic.On the one hand, Lenin wrote in 1913, capitalism tended towards ‘consolidating nationalismwithin a certain ‘‘justly’’ delimited sphere, ‘‘constitutionalising’’ nationalism, and securing the sep-aration of all nations from one another by means of a special state institution’. On the other, itmanifested a ‘tendency to break down national barriers, obliterate national distinctions, and to

3 For analyses of Marxist and early Soviet thinking on the relationship between social development and the natural

environment, especially in relation to questions of environmental determinism, see I.M. Matley, The Marxist approachto the geographical environment, Annals of the American Association of Geographers 56 (1966) 97e102; M. Bassin, Geo-graphical determinism in Fin-de-Siecle Marxism: Georgii Plekhanov and the environmental basis of Russian history,

Annals of the American Association of Geographers 82 (1992) 3e22.4 I take the evocative phrase ‘factory of fragmentation’ from D. Harvey, Spaces of Capital: Towards a Critical

Geography, London, 2001, 121e127.5 The phrase ‘humanisation of nature’ is from P. Dickens, Reconstructing Nature. Alienation, Emancipation and the

Division of Labour, London, 1996, 19.6 E.R. Goodman, The Soviet Design for a World State, New York, 1960.7 K. Marx and F. Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party, trans. Samuel Moore, Peking, 1970, 35. See also

M. Berman, All That Is Solid Melts into Air. The Experience of Modernity, Harmondsworth, repr. 1988.

568 N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

assimilate nations’. This latter dynamic, he asserted, was ‘one of the greatest driving forces trans-forming capitalism into socialism’ and hence should not be resisted.8 Of course, the capitalist ‘as-similation’ of nations was grounded in ‘force and privilege’, while proletarian internationalismentailed the democratic reconstitution of political space e the re-alignment of state borders in ac-cordance with the natural interests and orientations of their populations. Proletarian internation-alism meant, therefore, that non-Russian nationalities of the tsarist empire should enjoy the rightto self-determination, even to secede from the post-revolutionary state.9 Secession and nation-for-mation would, anyway, only be transitional. Ultimately, the international proletariat’s conscious-ness of its common class interests would prevail over and supersede nationalist considerations,culminating in ‘the future socialist unity of the whole world.’10

While waiting for the withering away of international borders, the Bolsheviks envisaged thattheir post-revolutionary state would undertake a fundamental reconfiguration of its internal spa-tial organisation. In their view, Russia’s pre-revolutionary territorial-administrative system ofprovinces ( gubernii), counties (uezdy) and districts (volosti), introduced by Catherine the Greatin the late eighteenth century, was an obsolete vestige of pre-modern spatial organisation, servingonly to thwart development and progress: the dead hand of its centre-periphery infrastructure sti-fled the productive energies which capitalism needed to feed upon, to reproduce itself and therebygenerate its own demise. ‘The preservation of the medieval, feudal, official administrative divi-sions’, Lenin had written in 1914, ‘means the ‘‘break up’’ and mutilation of the conditions of mod-ern capitalism’.11 For one thing, the old territorial system too rigidly reinforced the spatialdivisions of labour between urban centres and their rural hinterlands and between the EuropeanRussian core of the empire and its remote border regions.12 It was designed for bureaucratic or mil-itary purposes, rather than the promotion of economic intercourse and development. In 1921, theSoviet Russian Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs V.I. Vladimirov declared that Catherine’s ter-ritorial reforms had been introduced with the aim of strengthening provincial garrison centres fol-lowing the Pugachev serf rebellion of 1774e1775, and that her construction of road systemsradiating from these reinforced centres e which formed the internal structure of these territorialunits e had been planned only to facilitate military access to the outlying areas of each province.13

The pre-revolutionary settlement, a Soviet geographer wrote some years later, was a ‘police divi-sion of the land [.] based solely on the necessity of administering the collecting of taxes and

8 V.I. Lenin, Critical remarks on the national question (1913), in: Collected Works, Vol. 20, Moscow, 1964, 35, 28.Italics in original.

9 Lenin, Theses on the national question (1913), in: Collected Works, Vol. 19, Moscow, 1963, 243e251; and Lenin,

The right of nations to self-determination (1914), in: Collected Works, Vol. 20, Moscow, 1964, 393e454. For discussionof Lenin’s thinking on nationalities in relation to early Soviet state-building and territorial organisation, see R. Pipes,The Formation of the Soviet Union. Communism and Nationalism, 1917e1923, Cambridge, MA, 1997, 21e49; R.J. Kai-

ser, The Geography of Nationalism in Russia and the USSR, Princeton, NJ, 1994, 96e107; Y. Slezkine, The USSR asa communal apartment, or how a socialist state promoted ethnic particularism, Slavic Review 53 (1994) 415e452.10 Lenin, Critical remarks (note 8), 46.11 Lenin, Critical remarks (note 8), 49.12 See Lenin, The development of capitalism in Russia (1899), in: Collected Works, Vol. 3, Moscow, 1961, esp.

557e596, for an extended discussion of Russia’s nascent dynamics of spatial differentiation under capitalism.13 Speech to All-Russian Central Executive Committee (VTsIK), March 1921, in: G.M. Krzhizhanovskii (Ed.),

Voprosy ekonomicheskogo raionirovaniia SSSR. Sbornik materialov i statei (1917e1929 gg.), Moscow, 1957, 58.

569N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

the recruiting of soldiers’.14 This rigid, inert centre-periphery infrastructure also paid no heed to theaspirations of non-Russian minorities for self-determination or for social, cultural and economicgrowth: the tsarist empire was, in Lenin’s famous phrase, ‘a prison-house of nations’.15 In strivingto hold back History, the tsarist regime was resisting the momentum of Nature itself.

The Bolshevik revolution was to sweep away this bureaucratic, ‘anti-natural’ infrastructurewhich inhibited the population from engaging in the dynamic, vital, creative interaction withits physical environment which socialism was to initiate. ‘Social-Democrats demand the abolitionof the old administrative divisions of Russia . ’, Lenin had written in 1913, ‘and their replace-ment by divisions based on the requirements of present-day economic life and in accordance,as far as possible, with the national composition of the population’.16 This apparently straightfor-ward prescription disguised some difficult questions of both theory and practice. How shouldknowledge of ‘present-day economic life’ be formulated and its ‘requirements’ determined as basesfor spatial practice? What would happen when economic imperatives conflicted with national con-siderations? What form might these new territorial ‘divisions’ take if they were to mirror, and pro-mote, the organic spatial structures and dynamics of ‘life’?

The Bolsheviks were not hostile to the centre-periphery model of spatial organisation. On thecontrary, they understood this to be the essential spatial medium and articulation of capitalistdevelopment, serving to sweep away the feudal detritus (in Lenin’s words, ‘old, medieval, caste,parochial, petty-national, religious and other barriers’) and prepare the path for socialism.17

However, they drew a contrast between the lifeless, alienating, exploitative and oppressive char-acter of the centre-periphery structure under the old regime, and the dynamic, democratic, sym-metrical and reciprocally beneficial nature of the relationship to obtain under socialism. Inparticular, as we shall see later, they insistently invoked the ‘gravitational model’ of spatial struc-turation, not merely as metaphor, but as an objective, observable, embedded, active e andmutable e process.

Nor were the Bolsheviks antagonistic to large centralised states. On the contrary, Lenin wrotein 1914: ‘the class-conscious proletariat will always [.] fight against medieval particularism, andwill always welcome the closest possible economic amalgamation of large territories in which theproletariat’s struggle against the bourgeoisie can develop on a broad basis.’18 Following the rev-olution, the proletarian state would persist in striving for both expansion and centralisation ealbeit, of course, as preconditions of its own ultimate dissolution. However, this dynamic socialiststate-form would centralise its territory not by ‘force and privilege’, but according to the principleof ‘democratic centralism’. Paradoxically perhaps, this meant devolving local issues to the leveland type of territorial unit most competent to solve them: ‘Far from precluding local self-govern-ment’, Lenin asserted, ‘with autonomy for regions having special economic and social conditions, a

14 N.N. Mikhailov, Soviet Geography. The New Industrial and Economic Distributions of the USSR, foreword byH.J. Mackinder, London, 1935, 9.15 Lenin, The revolutionary proletariat and the rights of nations to self-determination (1915), in: Collected Works,

Vol. 21, Moscow, 1964, 413e414.16 Lenin, Theses on the national question (note 9), 245e246. My italics.17 Lenin, Critical remarks (note 8), 45.18 Lenin, Critical remarks (note 8).

570 N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

distinct national composition of the population, and so forth, democratic centralism necessarilydemands both.’19

In areas with mixed national populations, Lenin stressed that the ‘national composition of thepopulation is placed on the same level as the other conditions (economic first, then social, etc.) whichmust serve as a basis for determining the new boundaries’.20 In other words, national and economicforms and forces were regarded as objectively real and equally ‘natural’. Faced by such cases, thecentral state would have to seek a careful balance of different factors and interests:

The national composition of the population [.] is one of the very important economicfactors, but not the sole and not the most important factor. Towns, for example, play anextremely important economic role under capitalism, and everywhere [.] the towns aremarked by mixed populations. To cut the towns off from the villages and areas that econom-ically gravitate towards them, for the sake of the ‘national’ factor, would be absurd andimpossible. That is why Marxists must not take their stand entirely and exclusively on the‘national-territorial’ principle.21

The role of the centre-peripherymodel in structuring Lenin’s spatial thinking is evident in this pas-sage, as is his evaluation of its role in structuring the urbanerural relationship. The solution whichLenin advocated to balancing national interests and economic considerations, which was ratifiedas Bolshevik policy in 1913, was that ‘the boundaries of the self-governing and autonomous regionsmust be determined by the local inhabitants themselves on the basis of their economic and social con-ditions, national make-up of the population, etc.’.22 New territorial units democratically formed onthe basis of their populations’ knowledge of local spatial relationswould not only be in harmonywithexistingdistributions andflowsofpeople, commodities and resources, butwould channel andamplifythese energies for the good of socialist construction. In the Bolshevik geographical mind, post-revo-lutionary socialist boundary-drawing was to generate a new integration of social and natural land-scapes and processes, a more organic ‘human ecology’ of the regions.23 The question remainedhow to formulate knowledge of these processes, and how to translate knowledge into practice.

Although MarxismeLeninism was an ideology of History, I have argued that it manifested alsoan obsession with geography. Following the October 1917 Bolshevik take-over of power, the newgovernment immediately decreed the spatial emancipation of former imperial subjects. On 15 No-vember, Lenin and Josef Stalin (in his role as People’sCommissar forNationalities) signed into forcethe ‘Declaration on the Rights of the Peoples of Russia’. This document re-affirmed the Bolsheviks’commitment both to the ‘right of the peoples ofRussia to dispose of their own fate even to separationand the establishment of an independent state’ and to the ‘free development of national minorities

19 Lenin, Critical remarks (note 8), 46. Italics in original.20 Lenin, Critical remarks (note 8), 51. Italics in original.21 Lenin, Critical remarks (note 8), 50. Italics in original.22 Lenin, Resolutions of the summer, 1913, Joint Conference of the Central Committee of the R.S.D.L.P. and Party

Officials, in: Collected Works, Vol. 19, Moscow, 1963, 427e428. My italics. This policy was re-affirmed by Stalin inApril 1917, see below.23 For the concept of ‘human ecology’ as applied to regional studies in the early twentieth century, see A. Buttimer,

Edgar Kant and Balto-Skandia, Heimakunde and regional identity, in: D. Hooson (Ed.), Geography and National Iden-tity, Oxford, 1994, 165e167.

571N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

and ethnographic groups inhabiting Russian territory’.24 In subsequent months, many of the estab-lished nationalities onRussia’s western borders (including the Poles,Ukrainians andBalts) declaredsovereign independence. This did not unduly concern the Soviet leadership: in some cases, these ter-ritories were under German occupation or running their own affairs already; in most cases, the Bol-sheviks believed that independence would only be a transitional phase. Thus when Lenin on 31December 1917 acceded to the Finnish government’s appeal to exercise its right to national seces-sion, he did so in the conviction that the Finnish proletariat would soon seek to reunify with thenew Soviet republic. ‘The important thing for us is not where the state border runs’, Lenin had de-clared in early December, ‘but whether or not the people of all nations remain allied in the struggleagainst the bourgeoisie, irrespective of nationality’.25

By March 1918, however, Lenin’s hopes for Finland had been dashed. Not only had the Finnishbourgeois government suppressed a popular uprising during the winter, but now, with the help ofGerman forces, they were commencing incursions into the Russian region of Karelia in north-west European Russia.26 Assailed by the Finns from the west and Bolshevik Russians from theeast (and given false hopes of protection by the Allied expeditionary force which landed in late1918 in northern Russia), representatives of the indigenousKarelian population of this area formedtheir own provisional government in the town of Uhtua, about one hundred kilometres inland fromtheWhite Sea coast inKem’ county,Arkhangel’sk province (seeFig. 1). TheUhtua government con-vened a constituent assembly and demanded that Karelians too should be allowed to exercise theright of self-determination.27 The Soviet government would not, however, tolerate such radical as-pirations on the part of this small population group, the ‘national’ status of which it chose not toaccept. In early 1920, Russian Red Guards broke up the Karelian government and assembly atUhtua, and arrested its members. The question of who determined which population categoriesconstituteddistinct ‘nations’ or ‘nationalminorities’, andbywhich criteria,will be consideredbelow.

Meanwhile, the Soviet government had also promulgated measures for the spatial liberation ofits Russian population. The ‘Decree on Borders’ of January 1918 stated that each locality had theright to secede from any territorial unit into which it had been ‘forcibly incorporated’ during tsa-rist rule, and ‘to group itself around those natural centres towards which they feel gravitation’.This formulation vividly expressed the revolutionaries’ vision of a territorial arrangement basedon the population’s intuitive relationship with space, structured by ‘gravitational’ force-fields em-bedded in and dynamically reconstituting the centripetal order of the natural environment.28 The

24 J. Bunyan and H.H. Fisher (Eds), The Bolshevik Revolution 1917e1918: Documents and Materials, Stanford, CA,1965, 282e283.25 Lenin, Speech at the 1st All-Russian Congress of the navy (5 December 1917), in: Collected Works, Vol. 26, Mos-

cow, 1972, 341e346.26 On the Finnish Civil War, see A.F. Upton, The Finnish Revolution, 1917e1918, Minneapolis, 1980; and on subse-

quent FinnisheGerman assaults on Russian Karelia, see M. Jaaskelainen, Die Ostkarelische Frage. Die Entstehungeines Nationalen Expansionsprogramms und die Versuche zu seiner Verwirklichung in der Aussenpolitik Finnlands inden Jahren 1918e1920, Helsinki, 1965.27 S.Churchill, TheEastKarelianAutonomyQuestion inFinnisheSovietRelations, 1917e1922, unpublishedPh.D. disser-

tation, University of London, 1967; E.Iu. Dubrovskaia, Iz istorii podgotovki Ukhtinskogo s’ezda predstavitelei Karel’skikhvolostei, in: A.I. Afanas’eva and M.A. Mishenev (Eds), Voprosy istorii Evropeiskogo Severa, Petrozavodsk, 1998, 63e72.28 Explanatory circular on Decree ‘On Changing of Borders’ of 27 January 1918, dated 11 May 1918, State Archive of

the Russian Federation (GARF) 5677/2/2/20.

572 N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

actual processes unleashed, or retroactively sanctioned, by this decree were much more disor-dered. As civil conflict spread and administration collapsed, popular aspirations surged and largenumbers of Russian village and parish councils embarked on redrawing their own local bound-aries. As in Karelia, several larger outlying areas (such as the Don, Kuban and even Siberia) de-clared their own ‘national councils’ and ‘regional governments’. This was not what the Bolshevikshad envisaged. In Stalin’s striking image, the radial spread of the ‘revolutionary tide’ from the

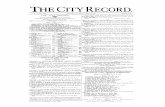

Fig. 1. North-West European Russia before the establishment of the Karelian Labour Commune, showing pre-revolutionary provin-

cial ( guberniia) and county (uezd ) borders and centres.

573N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

victorious centre into the ‘border regions’ encountered a ‘dam’ in the shape of these self-declaredautonomous territories.29

The Soviet central government was now forced to confront the ambiguities inherent in its ownideology of spatial reconstruction. Firstly, to what extent should spatial transformation be permit-ted to take the form of a spontaneous re-alignment between ‘natural’ and ‘social’ space, and towhat degree should it be an engineered and regulated process? Secondly, space could be ‘natural-ised’ along national lines or in accordance with economic criteria. In principle, they were bothequally ‘natural’ criteria, though seemingly incommensurable. In practice, which should take pre-cedence? Thirdly, how could optimal ‘natural’ structures and forces be identified (optimal in thesense of being the closest approximation to ‘nature’ during the transition to ultimate socio-spatialequilibrium)? In practice, these ambiguities translated into a complex of inter-related questionsconcerning: (1) post-revolutionary political organisation and the scope of central control; (2)the administrative structures of the new state and the parameters of local decision-making; (3)defining of which ethnic groups constituted nations or nationalities eligible to make territorialclaims; (4) the regional framework of economic planning; and (5) the role of the social and naturalsciences, and of expert knowledge, in policy-making.

Bolshevism was always an amalgam of ideology and pragmatism e its ideological dialecti-cism, indeed, permitted it to elevate pragmatism to a matter of principle. This frequently man-ifested itself as paradox and contradiction. During the Civil War, the new government’sstruggle for existence at the epicentre of revolution was the primary determinant of principle.Survival was a matter of power, and power entailed reconstructing the state. This expedient re-sort to state-building was not contrary to Leninist doctrine: as we have seen, the Bolshevikleader exalted the large centralised state as well as presaging its demise. The statist dimensionof doctrine dictated its own spatial perspectives. ‘We stand for the necessity of the state’, Leninhad asserted on his return to Russia in April 1917, ‘and a state presupposes borders’.30 Withregard to the larger border nationalities, this implied first of all curtailing their right to free se-cession. There was programmatic precedent for this, too. At the same 1917 April conferenceStalin had argued that ‘the question of secession must be determined in each particular caseindependently, in accordance with the existing situation, and, for this reason, recognizing theright of secession must not be confused with the expediency of secession in any given circum-stances’. In practice, larger nationalities whose secession was not deemed ‘expedient’ would begranted ‘regional autonomy’, the boundaries of which, in affirmation of Lenin’s ambiguous line,must ‘be determined by the populations themselves with due regard for economic conditions,customs, etc.’31

Post-revolutionary expediency meant that most population groups would simply not be recog-nised as discrete nationalities with any territorial rights. In January 1918, Stalin declared that con-flicts between border regions and the centre,

29 J.V. Stalin, The October revolution and the national question (1918), in: Works, Vol. 4, Moscow, 1953, 163.30 Lenin, Speech to the 7th All-Russian Conference of the RSDRP(b) (April 1917), in: Lenin, Polnoe Sobranie Sochi-

nenii, Vol. 31, Moscow, 1969, 435.31 Stalin, Report on the national question to the 7th All-Russian Conference of the RSDRP(b) (29 April 1917), in:

Works, Vol. 3, Moscow, 1953, 55.

574 N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

. were rooted in the question of power. And if the bourgeois elements of this or that regionsought to lend a national colouring to these conflicts, it was only because it was advanta-geous to them to do so, since it was convenient for them to conceal behind a national cloakthe fight against the power of the labouring masses within their region.32

Thus the Bolsheviks could reject Siberian or Karelian claims to national status as mere ‘hyp-ocritical cover’ for their hostile class politics.33 It is evident that Stalin’s allegation of dissimu-lation on the part of ‘bourgeois elements’ was based on the assumption that they had appealedto nationalism to lend their cause greater authenticity, in other words to make it appear natural.In fact, Stalin revealed to his audience, the real e that is to say, false e nature of bourgeoisnationalism resided in its class origin. Spatially, these areas of resistance were artificial, sociallyproduced ‘regions’ not national territories legitimised by nature. As well as starkly anticipatingStalinist rhetoric of ‘concealment’ and ‘masking’ in later decades (with its implication that sub-jects had a core ‘nature’ which they could hide but not change), this demonstrates how Marx-ismeLeninism’s intrinsic ambiguities (here regarding the ‘naturalism’ of national identity, whichwe discuss in more detail below) gave the Soviet leadership from the start wide scope for im-provised, pragmatic policy-making grounded nevertheless in authoritative statements ofprinciple.

This is also apparent in the Soviet government’s rapid rejection after the revolution of communalformsof local self-government in favourof establishing a centralised ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’.As we have seen, Lenin (as well asMarx) had written both for and against a strong post-revolution-ary state. Although self-administration by local committees and communes was established inMos-cow, Petrograd and elsewhere in the immediate aftermath of October 1917, the principle of publicinitiative and participation rapidly gave way to that of the centralised mobilisation of society by‘a powerful core, permeated by a single will and a single aspiration’.34 This ordering centre was nec-essary to direct the spontaneous energies of the periphery, with which it was supposedly now in har-mony. This philosophy is strikingly expressed in an article on popular festivals published in a Soviettheatre journal in 1920 by the People’s Commissar for Education Anatoly Lunacharsky.Writing ofmass demonstrations (which, he says, presuppose the ‘movement of themasses from the outskirts toone centre’), he rejects the claim that ‘collective creativity means a spontaneous, independent man-ifestation of the will of the masses’. Indeed, ‘until social life teaches the masses some kind of instinc-tive compliance with a higher order and rhythm, one cannot expect the throng to be able by itself tocreate anything but a lively noise and the colourful coming and going of festively dressed people’.35

Aswell as drawing attention to the aesthetic dimension of spatial practice, this statement emphasisesthe Bolsheviks’ perception of the transitional and imperfect character of contemporary ‘life’ (which,

32 Stalin, Report on the national question to the 3rd Congress of Soviets (15 January, 1918), in: Works, Vol. 4,Moscow, 1953, 32.33 Stalin, Report on the national question (note 32), 37.34 Bolshevik Party Central Committee circular, May 1918, cited in Richard Sakwa, The Commune State in Moscow in

1918, Slavic Review 46 (1987) 447.35 Cited in V. Tolstoy, I. Bibkova and C. Cooke (Eds), Street Art of the Revolution. Festivals and Celebrations in

Russia, 1918e33, London, 1990, 124. My italics.

575N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

we recall, Lenin invoked as the basis of socialist regional policy), their ultimate vision of society’s‘instinctive compliance’ with nature, and the imperative of interim interventions on the part of ex-perts and leaders to order a still disorderly human nature.

With regard to the political domain, Bolshevik leader Leon Trotsky wrote in 1920 that in ‘alldistricts of the country where the regime of ‘‘democracy’’ lived too long, it inevitably ended in anopen coup d’etat of the counter-revolution’. He pointed to Ukraine, Siberia and the EuropeanNorth, where regional governments had been defeated, and to the ‘small Border States’ e Fin-land, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Georgia and Armenia ewhere still, ‘under the formalbanner of ‘‘democracy,’’ there is being consolidated the supremacy of the landlords, the capital-ists, and the foreign militarists’.36 There could be no starker assertion of the new regime’s aversionto permitting formal participatory politics (‘democracy’ in inverted commas), devolving authorityto autonomous regional governments, or sanctioning spontaneous spatial practice by populationswhose ‘natural’ interests and territorial visions it believed diverged from its own.

In mid-1919, the Soviet government issued a decree stipulating that the Russian People’s Com-missariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) had to authorise all regional and district border changes.37

In early 1920, the VTsIK’s Administrative Commission (now responsible for regional policy)noted that, despite this earlier measure, it had been unable to keep track of changes in local bor-ders and place-names. The Commission ordered a spatial audit of the regions, and soon thereaf-ter, on Lenin’s direct orders, the Russian NKVD began to compile cartographic materials on thestate’s constituent territorial units.38 Henceforth, the Bolshevik state regarded the formulationand implementation of spatial policy as one of its central concerns. The subsequent narrativeof Soviet state-building is an account of the progressive consolidation of the regime’s controlover all forms of spatial knowledge, representation and practice.39

The nationalist origins of Soviet Karelia

The idea to form a Soviet Karelian autonomous region originated with Edvard Gylling, a Finn-ish Social Democrat and former Professor of Economics at Helsinki University, while he was liv-ing in exile in Stockholm after the failed revolution in his homeland. In early 1920, Gylling wrotea letter describing his vision to Yrjo Sirola, a Finnish comrade who had escaped to Petrograd inearly April 1918 and had founded the Finnish Communist Party (KPF) in Moscow later thatyear.40 In Gylling’s scheme, Soviet Karelia would embrace all lands between the Finnish border

36 L. Trotsky, Terrorism and Communism. A Reply to Karl Kautsky, London, 1975.37 Sovnarkom Decree, 15 July 1919, GARF 5677/2/2/23.38 See VTsIK circular, 30 April 1920, GARF 5677/2/2/l/27. For Lenin’s cartographic initiative, see V.F. Krempol’skii,

Istoriia razvitiia kartografii v Rossii i v SSSR, Moscow, 1959, 1e20.39 Communications, electricity grid and transport construction were other important elements of Soviet spatial plan-

ning, but will not be considered in this paper. See, for example, R. Argenbright, The Soviet agitational vehicle: state

power on the social frontier, Political Geography 17 (1998) 253e272; E. Widdis, Visions of a New Land. Soviet Filmfrom the Revolution to the Second World War, New Haven, London, 2003.40 Letter, undated (early 1920), in Finnish with Russian translation, in Foreign Policy Archive of the Russian Feder-

ation (AVP RF) 135/4/6-24/20-20ob. All documents cited in this paper have been translated from Russian by the authorunless otherwise stated.

576 N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

in the west and Lake Onega and the White Sea in the east, and stretch as far north as the ArcticOcean. It would be established, he proposed, on the same principles as the Petrograd commune,with extensive rights of self-administration in its internal affairs, economy and education. Further-more, it would be a place where

. a part of the Finnish population could earn a living developing the region’s economicproductive potential, could also receive military training in the defence of the border, andat the same time, without needing to involve Soviet Russia, could carry out revolutionaryagitation and, by establishing a model society on very border of Finland, could ideologicallyprepare the ground for the Finnish revolution.

To ensure that Karelia fulfilled its role in his ‘genuine revolutionary strategy’ for northernEurope, and to preclude the influence of bourgeois ‘petty separatism’ on the part of the indige-nous Karelians, Gylling recommended that the region’s leadership be placed in the hands of‘Red’ Finnish emigres. He eagerly volunteered his own services to direct this venture.

In another letter sent to Finnish colleagues in Moscow, Gylling developed his vision further.Karelian autonomy, he asserted, would be a valuable asset not only for Soviet Russia and forrevolution in northern Europe, but for the ‘World Revolution’. Soviet Karelia would form thebasis of a future Scandinavian Soviet Republic, which could ‘dictate its will to capitalist westernEurope’ by monopolising the timber supply.41 ‘It is the intention’, he stated in a later memoran-dum, ‘by means of the free collaboration in Karelia of all Scandinavian parties to create in thisregion a Scandinavian revolutionary centre’. In order that Soviet Karelia could plan its owndevelopment with a view to future amalgamation into an integrated North European Republic,Gylling also demanded that Scandinavian workers and experts should have complete freedomto cross the Soviet state border and to settle in the region.42 Soviet Karelia would thus be botha ‘centre’ in its own right and a ‘dual periphery’ oriented both eastwards and westwards.

The FinnisheRussian state border was central in Gylling’s vision of a new socialist Scandinaviagerminating from the Karelian revolutionary kernel. This border held various meanings for him,both spatial and temporal: it was to be a strategic line of defence and generator of political dif-ference, but also a porous zone of transition and catalyst of social and spatial transformation.For Gylling as Marxist, the border was a bourgeois construction, which like other attributes ofthe capitalist state system was destined with the victory of socialism inevitably to wither away.However, Gylling was also a nationalist, whose geographical imagination and political actionwere shaped by deeply-held assumptions about the place of Karelia in Finland’s ‘natural’ space.It was Gylling as nationalist who during the Finnish Civil War in the winter of 1918 had pro-nounced the disappearance of ‘the border between both kindred peoples’ to be not only desirablebut historically inevitable.43 It is necessary to deconstruct Gylling’s spatial vision to understand

41 From letter ‘Werte Genosse’, translation from German, undated (early 1920?), AVP RF 135/4/6-24/24-6.42 ‘Note on Karelian autonomy’, no author specified but style and content characteristic of Gylling, 3 February 1921,

translated from German, AVP RF 135/5/9-24/7.43 Gylling, March 1918, representing the short-lived Finnish socialist government during negotiations with Soviet

Russia on peace and a territorial settlement, cited in: V.M. Kholodkovskii, Finliandiia i Sovetskaia Rossiia,1918e1920, Moscow, 1975, 15. This Soviet author strongly plays down the Red Finns’ nationalist motivations.

577N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

whether, in principle or practice, these apparently distinctive socialist and nationalist teleologiescould be reconciled.

Gylling’s conception of FinnisheKarelian unity, the artificial nature of the existing state borderand the cultural ‘centrality’ of this extra-territorial periphery in Finland’s national geography, aswell as his opposition to the indigenous Karelians’ own ‘petty’ strivings for self-determination,were unashamedly grounded in nineteenth-century Romantic notions of national identity, nation-hood and ‘natural’ territory. At the heart of this philosophy lay the idea that ‘a people is as mucha plant of nature as a family’.44 Indeed, as Eric Hobsbawm has written, in this account the nationwas ‘so ‘‘natural’’ as to require no definition other than self-assertion’.45 This organic conceptionof the nation implied that as each plant had its habitat, and each family its own hearth, so eachnational culture had its ‘natural’ homeland.46 Throughout nineteenth-century Europe, national-ists decried the fact that existing configurations of political power and territory did not coincidewith the assumed ‘natural’ borders of their national cultures. Whether integration of the nation-state was to be achieved by separatism or unification, nationalist activists set out to demolishimperial territorial frameworks by promoting the belief that only ‘cultures [were] the naturalrepositories of political legitimacy . [and that] polities then will to extend their boundaries tothe limits of their cultures, and to protect and impose their culture within the boundaries of theirpower’.47 This understanding of historical change as the continuous striving of cultural organismsto ‘fill’ their natural environments, while transforming, excluding or eliminating alien elementswithin this space, had profound implications for projects of post-imperial state-construction,territorial settlement and population politics. In Eastern Europe after the First World War,this was equally true for ‘nationalizing’ and ‘revolutionizing’ states.48

For Finnish nationalists such as Gylling, such assumptions shaped their conception of the eth-nic constitution of the Finnish nation-state, its rootedness in a specific northern landscape and theextent of its ‘natural’ boundaries.49 Karelia in this account was an inalienable part of Finnish

44 Johann Gottfried von Herder, cited critically by the late nineteenth-century Austrian Marxist theorist of national-ism Otto Bauer, who sought to dissociate ‘nation’ from territory (an idea which, as we have seen, was explicitly rejected

by Lenin and Stalin). See Bauer, The nation, in: G. Balakrishnan (Ed.), Mapping the Nation, London, 1996, 75e76.45 E. Hobsbawm, Introduction: inventing traditions, in: E. Hobsbawm and T. Ranger (Eds), The Invention of Tradi-

tion, Cambridge, 1983, 13.46 On the nationalist significance of ‘homeland’, see H. Kohn, The Idea of Nationalism. A Study in Its Origins and

Background, New York, 1946, 329e341; A.D. Smith, The Ethnic Origins of Nations, Oxford, 1986, esp. Chapter 8;Smith, Nation and ethnoscape, Oxford International Review 8 (1997) 8e16.47 E. Gellner, Nations and Nationalism, Oxford, 1983, 49. I take the terms ‘unification nationalism’ and ‘separatist na-

tionalism’ from J. Breuilly, Nationalism and the State, Manchester, 1993.48 See N. Baron and P. Gatrell, Population displacement, state-building and social identity in the lands of the former

Russian empire, 1917e1923, Kritika. Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 4 (2003) 51e100. The notion of the

‘nationalizing’ state is borrowed from R. Brubaker, Nationalism Reframed: Nationhood and the National Question in theNew Europe, Cambridge, 1996.49 On spatial dimensions of Finnish nationalism, see A. Paasi, The construction of socio-spatial consciousness. Geo-

graphical perspectives on the history and contexts of Finnish nationalism, Nordisk Samhallsgeografisk Tidskrift 15(1992) 79e100; Paasi, Territories, Boundaries and Consciousness. The Changing Geographies of the FinnisheRussian Bor-der, Chichester, 1996, esp. 87e97. See also M. Hayrynen, The kaleidoscopic view: the Finnish national landscape im-

agery, National Identities 2 (2000) 5e19; K. Kosonen, Kartta ja kansakunta. Suomalainen lehdistokartografiasortovuosien protesteista Suur-Suomen kuvin, 1899e1942, Helsinki, 2000, with English summary.

578 N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

‘nature’, both internal and external. The Karelian landscape was the fount and repository of Fin-land’s national lore and recently-codified national language, and its people the Finnish ur-eth-nos.50 ‘Geographically, physically and ethnographically’, concluded a contemporary Finnishscientific survey of Karelia, ‘this country forms with Finland one natural and continuous whole’.51

The current FinnisheRussian border was therefore artificial and destined to be dissolved as theFinnish national state expanded to consolidate its ‘natural’ territory. Karelia’s ‘alienation’ underRussian imperial rule and the cause of national ‘unification’ became a rallying cry for a Finnish‘homeland nationalism’ which appealed to domestic sentiment across the political spectrum.52

This is a powerful example of the ‘naturalisation’ of the nation and of national space, operatingdiscursively both as a mechanism of social integration and a project of exclusion. In the words ofJan Penrose:

by conceiving of nations as ‘natural’ and by promoting them as such, processes of construc-tion, of human intervention, are obscured and the motivations behind such constructions areremoved from the realm of discussion. In this way, people whose motives have been fulfilledby a particular national construction are protected and people who have been disadvantagedare denied recourse.53

The Finnish romantic discourse of ‘Karelianism’, and Finnish nationalists’ geopolitical vision ofFinland’s natural Lebensraum in the east, thus bracketed out the indigenous Karelians’ own claimsto a discrete national identity and territory. Gylling’s own spatial vision of a ‘Greater Red Finland’similarly elided Karelia’s historical, cultural and ethnographic complexity and diversity.54

Gylling made no effort to disguise his nationalist convictions. Nor did he have any problemreconciling them with his equally sincere commitment to the socialist cause. In Leninist terms,Gylling’s vision for Karelia was nationalist in territorial form, but socialist in political content.In July 1921, Gylling declared to the Fourth KPF Congress in Moscow: ‘To claim that my pro-posal [to install a Finnish leadership in Karelia] is nationalist is true. But if we stimulate national-ism this will be good for the revolution . As long as it is revolutionary nationalism we shouldsupport it.’55 For Gylling, this formulation posed no paradox: by raising the indigenous Kareliansthrough education and economic development to a higher level of national consciousness e whichmeant, in his view, their accelerated evolution into modern Finns e he believed that he could alsoharness them to the Soviet cause. Their Finnish and Scandinavian brethren across the border,

50 On the Kalevala legends, see Michael Branch’s introduction to W.F. Kirby (trans.), Kalevala, London, 1985.51 T. Homen (Ed.), East Carelia and Kola Lapmark, Described by Finnish Scientists and Philologists, London, 1921,

254. On the scientific construction of Fenno-Skandia, see Buttimer, Edgar Kant and Balto-Skandia (note 23), 167e174.52 The term ‘homeland nationalism’ is from Brubaker, Nationalism Reframed (note 48), esp. 107e147.53 J. Penrose, Reification in the name of change: the impact of nationalism on social constructions of nation, people

and place in Scotland and the United Kingdom, in: P. Jackson and J. Penrose (Eds), Constructions of Race, Place andNation, London, 1993, 28.54 On Gylling’s concept of a ‘Greater Red Finland’, see M. Kangaspuro, Nationalities policy and power in Soviet Kar-

elia in the 1920s and 1930s, in: T. Saarela and K. Rentola (Eds), Communism National and International, Helsinki, 1998,128.55 Translated from Finnish, see Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (RGASPI) 516/2/1921/17/208. My

italics.

579N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

witnessing the Karelians’ eager, successful participation in socialist construction and new sense ofshared nationhood, would be convinced that revolution was both feasible and desirable in theirown countries not merely for the sake of socialism but also for the integration of national territory.

This national factor would also play a key role in establishing a union (smychka) between thenumerically weak Finnish proletariat and the peasantry, which had previously demonstratedambivalence or antagonism towards socialism. ‘For some nationalistic small peasant circles [inFinland]’, Gylling wrote to the Soviet People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs G.V. Chicherinin early 1920, ‘a revolution which brought all Finnish peoples together would acquire some attrac-tiveness.’56 While contradicting the tenets of orthodox Marxism, Gylling’s ‘revolutionary nation-alism’ was shared by many other Finnish socialists.57 More importantly, it was quite compatiblewith Lenin’s doctrinal and tactical thinking on the nationalities question.

For one thing, the Bolshevik conception of the ‘nation’ was inseparably bound up with both cul-ture and territoriality. In Stalin’s famous definition, the nation was ‘a historically evolved, stablecommunity of language, territory, economic life and psychological make-up manifested in a com-munity of culture.’58 As the indigenous Karelians had (as yet) no territory of their own, they couldbe denied the status of a discrete nationality. As Red Finnish nationalists claimed Karelia as part ofFinland’s national territory, the Soviet Russian leadership could conveniently e if other factorsmade this expedient e accede to their claims to submerge the Karelians within the Finnish nationalcategory. And by constructing Karelian territorial autonomy on Finnish nationalist terms, theyconfirmed the Finnish account of Karelian identity and denial of the indigenous population’sown national claims.

Of course, this approach assumed the that nations were somehow both ‘constructed’ and ‘nat-ural’. As Francine Hirsch has recently argued, the Bolsheviks reconciled this apparent contradic-tion by asserting that small ‘primordial’ ethnographic groups (such as the Karelians) formed‘building blocks’ for the ‘construction’ of nations (such as the Finns), which on the ‘Marxisttime-line’ were historical precursors of the universal socialist community. Soviet ‘state-sponsoredevolutionism’ was designed to accelerate this process.59 From this perspective, Lenin’s creationand promotion of territorialised national autonomies in the 1920s was not ‘affirmative action’as an end in itself but an instrumental policy of ‘double assimilation’, which aimed, by meansof constructing modern nationalities in the present, to generate the Soviet identity of the future.60

56 AVP RF 135/4/6-24/24-6 (note 41).57 In August 1918, for example, Sirola declared that when world revolution arrived, ‘once again Karelia and Finland

will unite in the brotherhood of the workers’, cited in Churchill, The East Karelian Autonomy Question (note 27), 311.

For other Red Finnish attitudes to Karelia, see A.A. Levkoev, Finliandskaia kommunisticheskaia emigratsia i obrazo-vanie Karel’skoi avtonomii v sostave RSFSR (1918e1923 gg.), in: L.I. Valulinksaia et al. (Eds), Obshchestvenno-politicheskaia istoriia Karelii ‘XX’ veka: ocherki i stat’i, Petrozavodsk, 1995, 24e49.58 As cited in Kaiser, The Geography of Nationalism (note 9), 102e103.59 F. Hirsch, Empire of Nations. Ethnographic Knowledge and the Making of the Soviet Union, Ithaca, 2005, esp. 4e10.

She argues against Terry Martin’s thesis that the transition from Leninism to Stalinism was reflected in a shift from

‘constructivism’ to ‘primordialism’, see Martin, Modernization or neo-traditionalism? Ascribed nationality and Sovietprimordialism, in: S. Fitzpatrick (Ed.), Stalinism. New Directions, London, 2000, 348e367.60 For ‘double assimilation’, see Hirsch, Empire of Nations (note 59), 14. The reference to ‘affirmative action’ is to

T. Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire. Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923e1939, Cambridge,MA, 2001.

580 N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

Thus a Soviet ethnographic expert could write in 1919 that ‘We are going to help you developyour Buriat, Votiak etc. language and culture, because in this way you will join the universal cul-ture, revolution and communism sooner’.61 Thus Gylling was able in 1921 to declare to theFourth KPF Congress that his aspiration to achieve Finnish national unification was itselfa ‘weapon in the class struggle’.62

The crucial point is that because the Bolsheviks believed History itself to be governed by naturallaws (of dialectical materialism), constructivist interventions which recognised and respected theseprocesses could themselves be construed as conforming to ‘nature’ and, indeed, enhancing ‘nature’both physical and human (as Marx had said, ‘by changing nature, man changes himself’). For na-tionalists, ‘nature’ articulated itself spatially in ‘imagined’ landscapes and distributions of ethnocul-turally constituted populations e and ethnographers drew their maps accordingly. As we shalldiscuss below, other interests based their conceptions of ‘natural’ space on ‘observed’ economicforms, flows and forces e and economists plotted these alternative contours and capacities. Expertsthus generated these ‘naturalising’ discourses of space: politicians arbitrated their realisation.

Gylling’s seemingly contradictory attitude to the FinnisheSoviet border was also compatiblewith Bolshevik principle and practice. That it should be a line of defence conformed to Lenin’sbelief in the centralised state which ‘presupposes borders’. That it was nevertheless artificialand transitional aligned with the Bolsheviks’ persisting ambitions for ‘world revolution’. As theSoviet government during 1919 found itself gaining advantage in the Civil War, the fluidity of mil-itary conflict seemed to present a renewed opportunity to stimulate or export revolution beyondRussia’s borders, prompting a resurgence of revolutionary ‘internationalism’. In March 1919, thefounding congress of the Communist International (Comintern), of which the Red Finn OttoKuusinen was one of the most prominent leaders, issued a call for the international proletariatto ‘wipe out the boundaries between states’.63 Gylling, though sharing little of his compatriot’sbelligerence, was doubtless aware of Bolshevik dreams of socialist expansion when he communi-cated to his vision for Soviet Karelia.

Finally, Gylling’s plan for a Karelian ‘revolutionary centre’ which, by opening its borders toco-ethnic immigration, territorially consolidating populations and promoting their economicand cultural development, would both generate and destabilise national difference, had alreadybeen anticipated in Lenin’s writings:

. it is beyond doubt that in order to eliminate all national oppression it is very important tocreate autonomous areas, however small, with entirely homogeneous populations, towardswhich members of the respective nationalities scattered all over the country, or even allover the world, could gravitate, and with which they could enter into relations and freeassociations of every kind.64

In early 1920, Lenin learned of Gylling’s project and summoned him to Moscow in May toreport on the feasibility of this venture. Sirola, who also attended the meeting, expressed his

61 Cited in Slezkine, The USSR as a communal apartment (note 9), 315.62 RGASPI 516/2/1921/17/208 (note 55).63 Platform of the Comintern, quoted in Goodman, The Soviet Design for a World State (note 6), 31.64 Lenin, Critical remarks (note 8).

581N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

scepticism: there were few proletarian workers in Karelia, he pointed out, and those who did existwere not Karelian but Russian immigrants to the region. Gylling, however, took a more sanguineperspective and confidently assured Lenin that autonomy itself would act as a powerful stimulusto the region’s development and encourage the national population to strive for ‘culture and thereinforcement of Soviet power’.65

Lenin was persuaded.66 As well as being in agreement with the ideological underpinnings of thisproject, he had specific strategic considerations in mind. By the end of the previous year, SovietRussia had fought off British intervention in northern Russia, and defended itself against incur-sions by ‘White’ Finnish irregulars into Karelia. Finland, however, still occupied two districtswithin the Russian border. In the spring of 1920, Soviet Russia urgently needed to conclude peaceand a definitive territorial settlement with Finland so that it could concentrate its forces furthersouth, where the Poles were gathering for an assault on the western borderlands. Finnish negoti-ators had already abandoned talks several times since Russia had first proposed a military cease-fire in August 1919. On 10 May (four days after Polish forces occupied Kiev), Chicherin wrote toLenin of the ‘extreme importance at the moment of avoiding a Finnish attack’, and told thePolitburo that Russia should propose diplomatic talks on a peace treaty to ‘bridle’ Finnishchauvinism.67 By declaring the establishment of Karelian autonomy on 7 June, Lenin offeredthe Finnish government a sop to nationalist sensitivities, without having to cede any territorysouth of the Arctic circle. A few days later, SovieteFinnish talks recommenced in Dorpat (Tartu),Estonia. On 17 June, the chief Soviet negotiator Ia.A. Berzin reported to Lenin that the Finnswould now ‘probably reconcile themselves fairly easily to the fate of Karelia.’68

Indeed, although the Finnish government suspected that the KTK’s creation was at best nomore than an empty promise, and at worst a cynical diplomatic ruse, after two years of uncer-tainty it too wished to reach a settlement and therefore agreed e to the dismay of a large partof its domestic public opinion e to the Soviet offer, on condition that the Russians made a formaldeclaration on the rights of autonomous Karelia and its indigenous ‘Karelo-Finnish’ population.The Treaty of Dorpat, with an ‘attached’ but separate Soviet Declaration on Karelia (partly basedon a draft drawn up by Gylling), was signed on 14 October 1920.69 By appealing to SovietRussia’s interests, in terms both of short-term pragmatism, and longer-term idealism, Gyllinghad realized his vision of Karelian autonomy. Crucially, however, it remained for him to secureits spatial form.

65 By ‘culture’, Gylling naturally meant Finnish culture. Account of meeting in Y. Sirola, Vospominaniia o Lenine, in:

S Leninym Vmeste. Vospominaniia. Dokumenty, Petrozavodsk, 1977, 62e63.66 On 18 May 1920, the Politburo agreed in principle to establish the KTK, convening a committee under M.F. Vla-

dimirskii to consider the project, see Politburo Protocol No. 11, in RGASPI 17/3/79/3. On 1 June Vladimirskii was

instructed to compile a decree for ratification by VTsIK on creating the KTK, and Stalin’s Organizational Bureau (Org-buro) was charged with deciding on the membership of the Karelian committee, see Protocol 17, in RGASPI 17/3/85/1and for earlier drafts of this decision, see RGASPI 17/163/71/3.67 Chicherin was particularly anxious about the possibility of English intervention in the Baltic, see Politburo Proto-

col, 11 May 1920, RGASPI 17/163/64/7.68 Letter to Lenin, Chicherin and Chief of the Red Army L.D. Trotskii, 17 June 1920, in AVP RF 0135/3/103-1/7-9.69 For the full text of the Treaty and attached Declarations, see A.G. Mazour, Finland Between East and West,

Westport, CT, 1956, 209e226.

582 N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

Defining the space of Karelian autonomy

We have already discussed how the Bolshevik regime, while proclaiming the revolutionary pri-macy of society’s ‘vital forces’ and legitimising their own authority with reference to the popular‘will’, remained sceptical and suspicious of the population’s level of culture and consciousness.Only power could cultivate society’s ‘internal’ nature so that it manifested ‘instinctive compliance’with the ‘higher order and rhythm’ of ‘external’ nature, before ‘life’ could be permitted, sponta-neously and autonomously, to exercise historical agency.

Bolshevism was an incarnation of ‘‘high modernist governmentality’’. This mode of rule strove,in the words of James Scott, to establish a ‘rational design of social order commensurate with thescientific understanding of natural laws’ and to transform both society and nature so that theywere ‘legible’ from the same discursive ‘grid’ of knowledge.70 Power was intimately, but often in-visibly, involved in these transformations, whereby social and scientific discourses, with the ‘ratio-nal’ practices they entailed, were ‘normalised’ to the extent that they constituted a ‘second nature’for subjects and citizens.71 To the high modernist project of ‘naturalising humanity’ and ‘human-ising nature’, the Bolsheviks brought a particularly pragmatic interpretation of socialist teleologyand a particularly brutal enactment of revolutionary voluntarism.

Space was a crucial dimension of high modernist discourse and practice. As both an objectivedimension of physical nature and a construction of human creativity, it was produced and repro-duced, both discursively and materially, according to scientific prescriptions politically arbitrated.We have already seen how Bolshevik ethnographers reconciled ‘naturalising’ and ‘social construc-tivist’ discourses of the nation in the doctrine and policy of ‘state-sponsored evolutionism’. Howdid Soviet economists understand the ‘natural laws’ by which economic phenomena and forcesstructured space, and operationalise these in regional planning?

For the most part, early Soviet social scientists derived their conceptions of economic spacefrom nineteenth-century ‘social physics’, especially from gravitational models of spatial interac-tion and variations of location theory.72 A report published in 1922 by the Soviet State PlanningAgency (Gosplan) described three approaches to regional planning, each of which illustrates thesignificance of ‘centrality’ in the social scientific understanding of space and spatial planning.73

Gosplan officials termed their first method ‘statistical regionalisation’. By this, they had inmind the delineation of territories that were economically homogenous, but they agreed thatthe method could also be applied to construct ethnographically pure regions. The planners con-ceded, however, that this method was principally an intellectual exercise, unrealisable in practice:either economic and ethnic distributions were so irregular or diffuse that their statistical centres

70 J. Scott, Seeing Like a State. How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed, New Haven,

London, 1998, 4.71 I take the idea of a socially-produced ‘second nature’ from Henri Lefebvre as cited in N. Brenner, Between fixity

and motion: accumulation, territorial organization and the historical geography of spatial scales, Environment and

Planning D: Society and Space 16 (1998) 459e481.72 On the history of the ‘gravity model’, see T.R. Tocalis, Changing theoretical foundations for the gravity concept of

human interaction, in: B.J.L. Berry (Ed.), The Nature of Change in Geographical Ideas, De Kalb, IL, 1978, 66e124.73 See Ekonomicheskoe raionirovanie Rossii. Doklad Gosplana III sessii VTsIK, in: Krzhizhanovskii, Voprosy eko-

nomicheskogo raionirovanie SSSR (note 13), 112e118.

583N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

and boundaries were no more than cartographic fictions that offered no basis for viable region-alisation, or they were concentrated in ‘central places’ that had no communication to similarthough statistically weaker ‘peripheral’ districts.

Gosplan’s second approach to regionalisation involved identifying where such centre-peripherylinks did already exist in practice, and then formalising these relationships. This was described as‘regionalisation according to centres, taking into account economic gravitation’. According to theauthors of the report, Alfred Weber’s work exemplified this method.74 They also drew attention tothe contemporary Russian scholar G.I. Baskin, whose research into land-use patterns in Samara,using the von Thunen concentric ring model, had demonstrated that ‘the evolution of economicforms is determined not only by temporal factors but also by spatial factors, in particular distancefrom market centres’.75 Not directly cited by the report, but implicit in its conceptualisation of‘centrality’ was E.E. Sviatlovskii’s ‘centrographic’ method. Drawing on statistical techniques de-veloped by United States geographers and demographers in the late nineteenth century, and onideas popularised in Russia at the turn of the twentieth century by the eminent chemist D.I. Men-deleev, Sviatlovskii’s ‘centrography’ aspired to provide a ‘scientific basis for regionalisation’ thatwould permit planners to identify the multiple centres (areal, demographic, economic, etc.) of ter-ritorial units at different scales and locate their optimal ‘centre of centres’ as the focus of spatialconstruction.76

Social scientists formulated their knowledge of contemporary economic ‘life’ on the basis ofobservation and statistical data-collection. This was supplemented by consultations with localpopulations. The questionnaires distributed, which requested information on existing and optimalspatial forms and forces in the locality e its central points, ‘economic gravitation’, communica-tion routes and natural barriers e embodied, and for local populations presumably served to con-struct, a set of normative principles by which contemporaries could ‘read’ spatial relationships inlandscape and envision their ‘rational’ reconfiguration.77

A 1924 VTsIK report on regionalisation proposed two significant modifications to this ap-proach. Firstly, it proposed that each region should be organised around an industrial proletariancentre, in order to effect the cultural and political transformation of its rural periphery. Secondly,it stated that in drawing regional boundaries, locating new industry and developing regionaltransport networks, the decisive factor should not be existing population concentrations and‘gravitational flows’ but potential capacities. In other words, the regime should site factories for

74 Alfred Weber’s work was first translated into Russian in 1926, but had been well known since its first German pub-

lication in 1909. See Alfred Weber, Teoriia razmeshcheniia promyslennosti, foreword by Nikolai Baranskii, Leningrad,Moscow, 1926.75 On the von Thunen model, see, e.g., J.D. Henshall, Models of agricultural activity, in: R.J. Chorley and P. Haggett

(Eds), Socio-Economic Models in Geography, London, 1968, 443e446. I.G. Baskin’s ideas were elaborated in his Raio-nirovanie territorii kak neobkhodimaia osnova ekonomicheskogo stroitel’stva, Moscow, 1921.76 See Sviatlovskii’s lecture on Mendeleev’s ‘centrographical method’ to the Statistical Division of the Russian Geo-

graphical Society, subsequently circulated among regional statistical bureaux, in GARF 5677/3/394/24-30. On Sviatlov-skii and Soviet ‘centrography’, see N. Baron, Soviet Karelia, 1920e1937. A Study of Space and Power in StalinistRussia, unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Birmingham, 2001, 57e58, 146e151.77 See, for example, ‘Questionnaire on administrative-economic information on Nadvoitskii district with regard to its

unification with the KTK,’ undated (mid-1921), GARF 5677/2/260/6.

584 N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

optimal access to their raw materials, and the workforce would then naturally ‘gravitate’ towardsand populate these empty centres.78 This ‘teleological’ approach to regional planning markeda radical departure from the ‘genetic’ empiricism of both Weberian industrial location theoryand Sviatlovskii’s ‘centrography’, and had dire consequences for later Soviet development. By en-couraging planners to place new industry in remote, exiguously populated but resource-rich areasto which no inducements could attract sufficient free labour, this mode of spatial planning lay thefoundations of the Stalinist Gulag system of coerced population displacement and forced la-bour.79 It envisioned not society’s reconciliation with nature, but humanity’s subjugation of thephysical environment: the price of the failure of this hubristic project was both human and envi-ronmental catastrophe.

The third approach described in the 1922 Gosplan report was ‘regionalisation according tocommunications links’. This, the report claimed, was the most widely applied method. Itwarned, however, that regional planners should not apply such a method in isolation, since(a) transport systems could easily be reconstructed (which would then necessitate the dissolu-tion and reconstitution of the spatial unit formed on their basis), and (b) the development ofcommunications should aim to unite regions, not to differentiate or divide them. The truth ofthese statements could already be read from the map of Russia’s north-western space. TheMurmansk railway, completed in 1916, had created a longitudinal ‘spine’ unifying the south-ern and northern Karelian areas, linking this newly integrated Karelian region with bothPetrograd to the south and Murmansk to the north, and rendering obsolete the latitudinalorientation of both Olonets and Arkhangel’sk provinces (see Figs. 1 and 2).80 Soviet Karelia’sautonomy was to a large extent predicated on this new transport link. (The Russian author-ities, of course, had built no railways in Karelia on an eastewest axis, but Finland had con-structed westeeast railways up to the state border, articulating and undergirding theirgeopolitical orientation and ambition.)

The 1922 Gosplan report concluded that regionalisation should eclectically operationalise allthree methods, as well as ensuring that regions should be self-sufficient in energy resources.Gosplan’s 1921 plan to divide Russia into twenty-one economic macro-regions represented oneattempt to restructure space according to economic principles.81 These approaches to regionalisa-tion, however, paid no attention to the peculiarities of the former Russian empire’s ethnographicmap. Nationalist desire for territorial autonomy conflicted with the ‘abstract geometries’ of theeconomic planners. The final section of the paper considers how Gylling deployed both economicand national arguments to carve out the shape of Soviet Karelia and defend the integrity of its

78 VTsIK Commission on Regionalisation report, undated (c. 1924), in GARF 6984/1/257/12-13.79 See N. Baron, Conflict and complicity: the expansion of the Karelian Gulag, 1923e1933, Cahiers du Monde russe 42

(2001) 615e648.80 The Arkhangel’sk-Vologda railway effected the same transformation east of lake Onega, reorienting the eastern dis-

tricts of Olonets province towards the Northern Region (the successor to Arkhangel’sk province). Olonets province was

thus divided between two ‘communications regions’. For a discussion of these spatial transformations in the context ofKarelian regionalisation, see Statisticheskii Obzor 1923e1924, Petrozavodsk, 1925, 1e6. Ia.E. Rudzutak described therailway as the ‘spine’ of the North-Western Region, cited in G.F. Chirkin, Sovetskaia Kanada (Karelo-Murmanskii

krai), Leningrad, 1929, 10.81 See P.M. Alampiev, Ekonomicheskoe raionirovanie SSSR, Moscow, 1959, 92e108.

585N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

regional borders, citing economic imperatives to quell opposition from within the region and eth-nographic principles to preclude encroachments from without.

As the Civil War drew to a close, Soviet ethnographers set about cataloguing ethnicities as thebasis for territorializing nationality, and economists embarked on tracing the rational landscapesof economic regionalisation. Though incommensurable in principle, each discourse penetrated theother. Most of these specialists understood that the final regional structure, where it concernedareas with national minorities, would be a hybrid product, not least because ‘nature’ itself wasa complex system which could not be reduced to pure abstraction (though there were maximalistson each side who strove for pure national territories or perfectly rational landscapes). Also, asHirsch has pointed out, the ethnographers were keen to avoid accusations that they ignoredmaterialist considerations, while the economists understood that the establishment of a unifiedeconomic space with an enforced territorial division of labour had undesirable imperialist conno-tations.82 Fortunately, pragmatic practice could be grounded in doctrinal principle. After all,Lenin, as we have seen, had already asserted that in drawing boundaries neither the national fac-tor nor economic ‘life’ should exclude the other: why should national areas, he had asked rhetor-ically, ‘not be able to unite in the most diverse ways with neighbouring areas of differentdimensions into a single autonomous ‘‘territory’’ if that is convenient or necessary for economicintercourse?’83 What was also obvious to most astute ethnographers and economists was that the‘institutionalisation’ of regions ultimately depended not on their scientific claims, but on a politicaldecision-making process which arbitrarily validated ‘knowledge’ according to perceived configu-rations of local power at the time and locality under consideration. How, then, did Karelianpower struggles in 1920e1923 draw on and operationalise the ethnographic and economic ac-counts of ‘naturalised’ space that we have surveyed?

As mentioned in the introduction, the 7 June 1920 decree on the KTK had defined neither theregion’s territory nor its administrative centre. It had, however, established under Gylling’s lead-ership a Karelian Revolutionary Committee (Revkom) to direct regional administration. Thisbody immediately raised the question of borders: on 14 July it despatched a letter to the Sovietcentral government warning that it could ‘only work if the borders of the KTK are precisely de-termined and the districts over which the Revkom will have undisputed authority are defined’.84 Itmight be assumed that Gylling, the Finnish nationalist, would stand unambiguously for drawingregional boundaries on national criteria. However, Gylling was also an economics professor anda pragmatist, and since his arrival in Moscow in early 1920 had consistently emphasized, in hiswritten and oral communications with Lenin, Chicherin, Stalin and others, that although thenew region should have a majority of Karelians, it should also dispose of sufficient productive re-sources, in terms of both raw materials and labour, to make its self-administration viable.85 Forthis reason, Gylling demanded that the KTK’s regional territory should be defined according to

82 Hirsch, Empire of Nations (note 59), 82e92. I also make this point in Baron, Soviet Karelia (note 76), 53 andpassim.83 Lenin, Critical remarks (note 8), 49. My italics.84 Letter of the Karelian Revolutionary Committee (Revkom) to the VTsIK Presidium, 14 July 1920, GARF

5677/1/268/82-83.85 See GARF 5677/1/268/82-83 (note 84); and his statement to the Commission for Determining the Borders of

Olonets province and KTK, June 1920, in National Archive of the Republic of Karelia (NA RK) 28/1/38-320/13-17.

586 N. Baron / Journal of Historical Geography 33 (2007) 565e595

a hybrid principle of boundary-drawing: ‘The KTK’, he declared bluntly in July 1920, ‘can onlyexist as an economic unit within the borders of a national-economic variant’.86 This approachmeant, on the one hand, including in Karelia a Russian population of about 60,000 (concentratedmainly in the town of Petrozavodsk and its immediate hinterland, which Gylling demanded inview of its status as the region’s ‘economic centre’), and, on the other, excluding approximately20,000 Karelians and ethnically related Veps (predominantly in villages districts south of theRiver Svir and east of Lake Onega), because of their weak communications links to Petrozavodsk(see Fig. 2).87