NATIONAL REGISTER BULLETIN - Texas Historical ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of NATIONAL REGISTER BULLETIN - Texas Historical ...

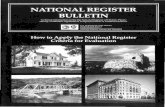

NATIONAL REGISTERBULLETIN

Technical information on the the National Register of Historic Places:survey, evaluation, registration, and preservation of cultural resources

U.S. Department of the InteriorNational Park ServiceCultural ResourcesNational Register, History and Education

DEFINING BOUNDARIES FORNATIONAL REGISTER PROPERTIES

The mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provideaccess to our Nation's natural and cultural heritage and honor our trustresponsibilities to tribes.

This material is partially based upon work conducted under a cooperativeagreement with the National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officersand the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Cover:

(Top Left) Detail of USGS map showing the National Register boundaries of theColumbia Historic District in Cedarburg, Wisconsin.

(Top Right) View of Architect Marcel Breuer's International Style home in Lincoln,Massachusetts. (Ruth Williams)

(Bottom Left) View of the Roxborough State Park Archeological District near Waterton,Colorado. (William Tate)

(Bottom Right) Detail of a 1987 land survey map defining the property boundaries ofGunston Hall in Buncombe County, North Carolina. (Blue Ridge Land Surveying, Inc.)

NATIONAL REGISTBULLETIN

DEFINING BOUNDARIES FORNATIONAL REGISTER PROPERTIES

BYDONNA J. SEIFERT

includingBarbara J. Little, Beth L. Savage, and John H. Sprinkle, Jr.

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIORNATIONAL PARK SERVICE

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES1995, REVISED 1997

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE ii

CREDITS AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii

I. DEFINING BOUNDARIES FOR NATIONAL REGISTER PROPERTIES 1

Why Boundaries are Important 1Getting Help 1Deciding What to Include 2Factors to Consider 2Selecting Boundaries 3Revising Boundaries 4

II. DOCUMENTING BOUNDARIES 5

Completing Section 10, Geographical Data 5The Verbal Boundary Description and Boundary Justification 5Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) References 6Global Positioning System (GPS) 6

III. CASE STUDIES 7

Boundaries for Buildings 7Buildings in Urban Settings 7Buildings in Rural Settings 10

Boundaries for Historic Districts 12Contiguous Districts in Urban Settings 13Discontiguous Districts in Urban Settings 16Contiguous Districts in Rural Settings 17Discontiguous Districts in Rural Settings 23Parks as Districts 23

Boundaries for Particular Property Types 27Traditional Cultural Properties 27Mining Properties 27

Boundaries for Archeological Sites and Districts 30Archeological Sites 31Contiguous Archeological Districts 33Discontiguous Archeological Districts 34Shipwreck Sites 35

Boundaries for Historic Sites 36

Boundaries for Objects 40

Boundaries for Structures 41

IV. REFERENCES 45

V. NATIONAL REGISTER CRITERIA FOR EVALUATION 46

VI. NATIONAL REGISTER BULLETINS 47

APPENDIX: Definition of National Register Boundaries for Archeological Properties(formerly National Register Bulletin 12: Definition of National Register Boundaries for Archeological Properties) 48

PREFACE

The National Register of HistoricPlaces is the official Federal list ofdistricts, sites, buildings, structures,and objects significant in Americanhistory, architecture, archeology,engineering, and culture. NationalRegister properties have significancein the prehistory or history of theircommunity, State, or the nation. TheNational Register is maintained by theNational Park Service on behalf of theSecretary of the Interior.

National Register Bulletins provideguidance on how to identify, evaluate,

document, and register significantproperties. This bulletin is designedto help preparers properly select,define, and document boundaries forNational Register listings and deter-minations of eligibility. It includesbasic guidelines for selecting bound-aries to assist the preparer in complet-ing the National Register RegistrationForm. Examples of a variety ofproperty types are presented. Theseexamples illustrate several ways toaddress boundary issues.

This bulletin was prepared byDonna J. Seifert, archeologist, under acooperative agreement between theNational Conference of State HistoricPreservation Officers and the Na-tional Park Service.

Carol D. ShullKeeper,National Register of Historic PlacesNational Park ServiceU. S. Department of the Interior

CREDITS ANDACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This bulletin addresses issuesoriginally presented in NationalRegister Bulletin: Definition of Bound-aries for Historic Units of the NationalPark System and National RegisterBulletin: How to Establish Boundariesfor National Register Properties. Bothwere prepared before National RegisterBulletin: How to Complete the NationalRegister Registration Form was revised.This revised bulletin complements theguidelines on boundaries in How toComplete the National Register Registra-tion Form and provides a variety ofcase studies to assist nominationpreparers.

This bulletin benefited from thesuggestions offered by the staffmembers of the National Register ofHistoric Places, who shared theiropinions and expertise. Criticalguidance was provided by Carol D.Shull, Antoinette J. Lee, and JanTownsend; Beth Savage provided animportant case study, which wasincluded in the bulletin. John Byrneof the National Register staff, pre-pared lists of properties to consider inthe selection of the case studies, andTanya M. Velt of the National Confer-ence of State Historic PreservationOfficers provided research assistance.

Comments and contributions fromthe following individuals wereparticularly valuable: Paul Alley,Western Regional Office, NationalPark Service; David Banks, Inter-agency Resources Division, NationalPark Service; Robin K. Bodo, Dela-ware Historic Preservation Office;Carol Burkhart, Alaska RegionalOffice, National Park Service; WilliamR. Chapman, Historic PreservationProgram, University of Hawai'i atManoa; Rebecca Conard, TallgrassHistorians L.C.; Dan G. Diebler,Pennsylvania Historical and MuseumCommission; Jim Draeger, WisconsinDivision of Historic Preservation;Audry L. Entorf, General ServicesAdministration; Betsy Friedberg,Massachusetts Historical Commis-sion; Bruce Fullem, New York StateOffice of Parks, Recreation andHistoric Preservation; Elsa Gilbertson,Vermont Division for Historic Preser-vation; Susan L. Henry, InteragencyResources Division, National ParkService; Gerri Hobdy, LouisianaOffice of Cultural Development;Thomas F. King, Silver Spring,Maryland; John Knoerl, InteragencyResources Division, National ParkService; Paul Lusignan, Interagency

Resources Division, National ParkService; Kirk F. Mohney, MaineHistoric Preservation Commission;David L. Morgan, Kentucky HeritageCouncil; Bruce Noble, InteragencyResources Division, National ParkService; William W. Schenk, MidwestRegional Office, National ParkService; and Robert E. Stipe, ChapelHill, North Carolina.

This publication has been preparedpursuant to the National HistoricPreservation Act of 1966, as amended,which directs the Secretary of theInterior to develop and make avail-able information concerning historicproperties. Defining Boundaries forNational Register Properties wasdeveloped under the generaleditorship of Carol D. Shull, Keeper,National Register of Historic Places.Antoinette J. Lee, historian, wasresponsible for publications coordina-tion, and Tanya M. Velt providededitorial and technical support.Comments on this publication may bedirected to Keeper of the NationalRegister of Historic Places, NationalPark Service, 1849 C Street, NW,Washington, D.C. 20240.

in

I. DEFINING BOUNDARIESFOR NATIONAL REGISTERPROPERTIES

The preparer of a National Registernomination collects, evaluates, andpresents the information required todocument the property and justify itshistorical significance. Among thedecisions the preparer must make isthe selection of the property's bound-aries: in addition to establishing thesignificance and integrity of a prop-erty, the physical location and extentof the property are defined as part ofthe documentation. Boundary infor-mation is recorded in Section 10,Geographical Data, on the NationalRegister Registration Form. Thisbulletin is designed to assist thepreparer in selecting, defining, anddocumenting boundaries for NationalRegister properties. The bulletinaddresses the factors to consider andincludes examples that illustrateproperly defined boundaries for avariety of property types.

WHY BOUNDARIESARE IMPORTANT

Carefully defined boundaries areimportant for several reasons. Theboundaries encompass the resourcesthat contribute to the property'ssignificance. Boundaries may alsohave legal and management implica-tions. For example, only the areawithin the boundaries may be consid-ered part of the property for thepurposes of Federal preservation taxincentives and charitable contribu-tions. State and local laws that requireconsideration of historic resourcesmay also refer to boundaries in theapplication of implementing regula-tions or design controls. NationalRegister boundaries, therefore, havelegal implications that can affect theproperty's future. Under Federal law,

however, these considerations applyonly to government actions affectingthe property; National Register listingdoes not limit the private owner's useof the property. Private propertyowners can do anything they wishwith their property, provided noFederal license, permit, or funding isinvolved. ,

Under Section 106 of the NationalHistoric Preservation Act of 1966, asamended, Federal agencies must takeinto account the effect of their actionson historic properties (defined asproperties in, or eligible for, theNational Register of Historic Places)and give the Advisory Council onHistoric Preservation the opportunityto comment. To be in compliancewith the act, Federal agencies mustidentify and evaluate NationalRegister eligibility of propertieswithin the area of potential effect andevaluate the effect of the undertakingon eligible properties. The area ofpotential effect is defined as the areain which eligible properties may beaffected by the undertaking, includingdirect effects (such as destruction ofthe property) and indirect effects(such as visual, audible, and atmo-spheric changes which affect thecharacter and setting of the property).

The area of potential effect mayinclude historic properties that arewell beyond the limits of the under-taking. For example, a Federalundertaking outside of the definedboundaries of a rural traditionalcultural property or an urban historicdistrict can have visual, economic,traffic, and social effects on thesetting, feeling, and association of theeligible resources.

Large properties present specialproblems. For example, an undertak-ing in a narrow corridor, such as apipeline, may affect part of a large

archeological site, traditional culturalproperty, or rural historic district.Such properties may extend farbeyond the area of potential effect oraccess may be denied in areas beyondthe undertaking. It is always best toconsider the entire eligible property,but it may not be possible or practicalto define the full extent of the prop-erty. In such cases, reasonable,predicted, estimated, or partialboundaries encompassing resourceswithin the area of potential effect maybe the only way to set the limits ofcontributing resources when theentire property cannot be observed orevaluated from historic maps or otherdocuments (as in the case of subsur-face archeological resources). Con-sider all available information andselect boundaries on the basis of thebest information available. Whendefining boundaries of large resourcesextending beyond the area of poten-tial effect, it is advisable to consult theState historic preservation office.

GETTING HELPIn addition to the guidance in this

bulletin, assistance is also availablefrom State Historic PreservationOfficers, Federal Preservation Offic-ers, and the staff of the NationalRegister of Historic Places. Theseprofessionals can help preparers withgeneral questions and special prob-lems. For assistance with specificquestions or for information on howto contact the appropriate StateHistoric Preservation Officer orFederal Preservation Officer, contactthe National Register of HistoricPlaces, National Register, History andEducation, National Park Service,1849 C Street, NW, Washington, D.C.20240.

1

Several other National Registerpublications are also available toassist preparers. National RegisterBulletin: How to Complete the NationalRegister Registration Form provides thebasic instructions for boundaryselection and documentation. Thefollowing instructions, which areconsistent with those in How toComplete the National Register Registra-tion Form, provide additional assis-tance for the preparer. The followingdiscussion addresses many propertytypes by considering the specialboundary problems associated witheach type and providing case studiesto assist the preparer in dealing withsuch issues. Bulletins that deal withspecific property types may also beuseful (see the list of National Regis-ter Bulletins at the end of this publica-tion).

DECIDING WHATTO INCLUDE

Selection of boundaries is a judg-ment based on the nature of theproperty's significance, integrity, andphysical setting. Begin to considerboundaries during the research anddata-collection portion of the nomina-tion process. By addressing boundaryissues during the field and archivalresearch, the preparer can take intoaccount all the factors that should beconsidered in selecting boundaries.When significance has been evalu-ated, reassess the boundaries toensure appropriate correspondencebetween the factors that contribute tothe property's significance and thephysical extent of the property.

Select boundaries that define thelimits of the eligible resources. Suchresources usually include the immedi-ate surroundings and encompass theappropriate setting. However,exclude additional, peripheral areasthat do not directly contribute to theproperty's significance as buffer or asopen space to separate the propertyfrom surrounding areas. Areas thathave lost integrity because of changesin cultural features or setting shouldbe excluded when they are at theperiphery of the eligible resources.When such areas are small andsurrounded by eligible resources, theymay n6{ be excluded, but are includedas noncontributing resources of theproperty. That is, do not selectboundaries which exclude a smallnoncontributing island surrounded by

GUIDELINES FOR SELECTING BOUNDARIES:ALL PROPERTIES

(summarized from How to Complete the National Register Registration Form,p. 56)

• Select boundaries to encompass but not exceed the extent of the signifi-cant resources and land areas comprising the property.

• Include all historic features of the property, but do not include bufferzones or acreage not directly contributing to the significance of theproperty.

• Exclude peripheral areas that no longer retain integrity due to alter-ations in physical conditions or setting caused by human forces, suchas development, or natural forces, such as erosion.

• Include small areas that are disturbed or lack significance when theyare completely surrounded by eligible resources. "Donut holes" arenot allowed.

• Define a discontiguous property when large areas lacking eligibleresources separate portions of the eligible resource.

contributing resources; simplyidentify the noncontributing resourcesand include them within the bound-aries of the property.

Districts may include noncontribut-ing resources, such as altered build-ings or buildings constructed beforeor after the period of significance. Insituations where historically associ-ated resources were geographicallyseparated from each other during theperiod of significance or are separatedby intervening development and arenow separated by large areas lackingeligible resources, a discontiguousdistrict may be defined. The bound-aries of the discontiguous districtdefine two or more geographicallyseparate areas that include associatedeligible resources.

FACTORS TOCONSIDER

There are several factors to con-sider in selecting and defining theboundaries of a National Registerproperty. Compare the historic extentof the property with the existingeligible resources and considerintegrity, setting and landscapefeatures, use, and research value.

• Integrity: The majority of theproperty must retain integrity oflocation, design, setting, feeling,and association to be eligible. Theessential qualities that contribute toan eligible property's significance

must be preserved. Activities thatoften compromise integrity includenew construction or alterations to theresource or its setting. Naturalprocesses that alter or destroyportions of the resource or its setting,such as fire, flooding, erosion, ordisintegration of the historic fabric,may compromise integrity. Forexample, an abandoned farmhousethat has been exposed to the ele-ments through years of neglect mayhave lost its integrity as a building;however, it may retain integrity asan archeological site.

Setting and Landscape Features:Consider the setting and historicallyimportant landscape features.Natural features of the landscapemay be included when they arelocated within the district or wereused for purposes related to thehistorical significance of the prop-erty. Areas at the margins of theeligible resources may be includedonly when such areas were histori-cally an integral part of the property.For example, a district composed offarmsteads along a creek mayinclude the creek if it runs throughthe district, if the creek was impor-tant in the original siting of thefarmsteads, or if the creek was asource of water power or naturalresources exploited by the farm-steads. Consult National RegisterBulletin: Guidelines for Evaluating andDocumenting Rural Historic Land-scapes for additional guidance inselecting boundaries for ruralhistoric landscapes.

• Use: Consider the historic use ofthe property when selecting theboundary. The eligible resourcemay include open spaces, naturalland forms, designed landscapes,or natural resources that wereintegral to the property's historicuse. Modern use may be different,and some modern uses alter thesetting or affect built resources.The effect of such uses must beassessed in identifying resourcesthat retain integrity. For example,a Hopewell mound archeologicalsite now used as a golf course mayretain integrity where the form ofthe prehistoric earthworks has beenpreserved, but construction of sandtraps or other landscaping thataltered landforms would compro-mise integrity. A marsh thatprovides plant materials fortraditional basketmakers mayretain integrity where it remains inits natural wetland condition, butmay have lost integrity where ithas been drained and cultivated.

• Research Potential: For propertieseligible under Criterion D, defineboundaries that include all of theresources with integrity that havethe potential to yield importantinformation about the past. Suchinformation is defined in terms ofresearch questions to which theinformation pertains, and theproperty should include the com-ponents, features, buildings, orstructures that include the informa-tion. For example, an eligibleprehistoric longhouse site shouldinclude longhouse features as wellas associated pit features, middens,and hearths. Geographicallyseparate but historically associatedactivity areas may also be includedin the property even when they arenot adjacent to the main concentra-tion of eligible resources. Forexample, lithic procurement andprocessing loci that were histori-cally associated with a village sitebut geographically separated fromit may be included in a discon-tiguous district. Remember thatmany properties eligible underother criteria include contributingarcheological resources that mayyield important information aboutthe property. Consider the extentof associated archeological re-sources when selecting boundaries.

SELECTINGBOUNDARIES

Identify appropriate natural orcultural features that bound theeligible resource. Consider historicaland cartographic documentation andsubsurface testing results (for archeo-logical resources) in addition toexisting conditions. Some boundariescan be directly observed by examin-ing the property; others must beidentified on the basis of research.Take into account the modern legalboundaries, historic boundaries(identified in tax maps, deeds, orplats), natural features, culturalfeatures, and the distribution ofresources as determined by surveyand testing for subsurface resources.

Owner objections may affect thelisting of the entire property, but notthe identification of the boundaries. Ifthe sole private owner of a propertyor the majority of the private owners(for properties with multiple owners)objects to listing, the property (withboundaries based on an objectiveassessment of the full extent of thesignificant resources) may be deter-mined eligible for the NationalRegister but not listed.

Boundaries should include sur-rounding land that contributes to thesignificance of the resources byfunctioning as the setting. Thissetting is an integral part of theeligible property and should beidentified when boundaries areselected. For example, do not limitthe property to the footprint of thebuilding, but include its yard orgrounds; consider the extent of allpositive subsurface test units as wellas the landform that includes thearcheological site; and include theportion of the reef on which the vesselfoundered as well as the shipwreckitself.

• Distribution of Resources: Use theextent of above-ground resourcesand surrounding setting to definethe boundaries of the property. Forarcheological resources, considerthe extent of above-ground re-sources as well as the distributionof subsurface remains identifiedthrough testing when defining theboundaries of the property.

• Current Legal Boundaries: Use thelegal boundaries of a property asrecorded in the current tax map orplat accompanying the deed when

these boundaries encompass theeligible resource and are consistentwith its historical significance andremaining integrity.

• Historic Boundaries: Use theboundaries shown on historic platsor land-ownership maps (such asfire insurance or real estate maps)when the limits of the eligibleresource do not correspond withcurrent legal parcels.

• Natural Features: Use a naturalfeature, such as a shoreline, terraceedge, treeline, or erosional scar,which corresponds with the limit ofthe eligible resource.

• Cultural Features: Use a culturalfeature, such a stone wall,hedgerow, roadway, or curb line,that is associated with the signifi-cance of the property, or use anarea of modern development ordisturbance that represents thelimit of the eligible resource.

Selecting boundaries for someproperties may be more complicated,however. Consider and use as manyfeatures or sources as necessary todefine the limits of the eligible re-source. In many cases, a combinationof features may be most appropriate.For example, the National Registerboundaries of a property could bedefined by a road on the south, afence line on the west, the limits ofsubsurface resources on the north,and an area of development distur-bance on the east. Consider mapfeatures or reasonable limits whenobvious boundaries are not appropri-ate.

• Cartographic Features: Use large-scale topographic features, contourlines, or section lines on UnitedStates Geographical Survey mapsto define the boundaries of largesites or districts.

• Reasonable Limits: Use reasonablelimits in areas undefined by naturalor cultural features. For example,define the boundary of a propertyas 15 feet or 5 meters from the edgeof the known resources, or define astraight line connecting two otherboundary features. If a surveyedtopographic map is available, selecta contour line that encompassesthe eligible resources. Reasonablelimits may also be appropriate fora rural property when there is noobvious house lot or natural orcultural feature to use. Be sure thatan appropriate setting is included

within arbitrary boundaries,however, and explain how thelimits were selected.

REVISINGBOUNDARIES

Boundaries for listed propertiesneed to be revised when there arechanges in the condition of theresources or the setting. If resourcesor setting lose integrity and no longercontribute to the significance of theproperty, it is appropriate to revisethe boundaries. Revisions may alsobe appropriate for nominationsprepared in the early years of theNational Register program, whennominations had limited or vagueboundary documentation. Follow theguidance presented in this bulletinwhen revising boundary documenta-tion.

II. DOCUMENTINGBOUNDARIES

COMPLETINGSECTION 10,GEOGRAPHICALDATA

Section 10 of the National RegisterRegistration Form is the portion of theform where boundaries of the nomi-nated property are documented. Thedocumentation requirements arediscussed in National Register Bulletin:How to Complete the National Register

Registration Form; the informationpresented here is consistent with thatdiscussion. The information require-ment in Section 10 of the registrationform includes acreage of the property,Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM)references, a verbal boundary descrip-tion, and a boundary justification. Inaddition, nomination preparers shouldsubmit a USGS map that shows thelocation of the property and plottedUTM coordinates and at least onedetailed map or sketch map for dis-tricts and for properties containing asubstantial number of sites, structures,or buildings.

THE VERBALBOUNDARYDESCRIPTIONAND BOUNDARYJUSTIFICATION

The verbal boundary descriptiondescribes the physical extent of thenominated property. A verbalboundary description or a scale mapprecisely defining the property

SECTION 10, GEOGRAPHICAL DATA

(summarized from How to Complete the National Register Registration Form, pp. 54-55)

Acreage: Calculate the acreage of the property to the nearest whole acre; calculate fractions of acres to thenearest one-tenth acre. For small properties, record "less than one acre." For large properties (over 100 acres), usea United States Geological Survey (USGS) acreage estimator or digitizer to calculate acreage.

UTM Reference: Use Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) grid references to identify the exact location of theproperty. For a small property, use a single UTM reference; for larger properties, use a series of UTM references(up to 26) to identify the boundaries. Even when natural or cultural features are used to define the boundaries, useUTM grid references to define a polygon which encloses the boundaries of the property and identifies the vicinityof the property.

Determine UTM references by using a UTM template and USGS quadrangle maps (see Appendix VIII inHow to Complete the National Register Registration Form and Using the UTM Grid System to Record Historic Sites forassistance in determining UTM references).

Verbal Boundary Description: Describe the boundaries verbally, using one of the following:

• a map may be substituted for a narritive verbal boundary description• legal parcel number• block and lot number• metes and bounds

• dimensions of a parcel of land, reckoning from a landmark, such as a natural or cultural featureBoundary Justification: Provide a concise explanation of the reasons for selecting the boundaries, based on the

property's historic significance and integrity. Discuss the methods used to determine the boundaries. Account forirregular boundaries and areas excluded because of loss of integrity. For archeological properties, discuss thetechniques used to identify the limits of the eligible resource, including survey procedures and the extent anddistribution of known sites.

boundaries must be given for allproperties regardless of their classifi-cation category or acreage. The verbalboundary description need not becomplicated or long, but it mustclearly describe (or show) the limits ofthe resources to ensure that a Federalagency, State historic preservationoffice, city planning office, planningagency, or property owner canidentify the limits of a NationalRegister property.

A map drawn to a scale of at least 1inch to 200 feet may be used in placeof a verbal description. When using amap in place of a verbal description,note under the verbal boundarydescription that the boundaries areindicated on the accompanying map.The map must be clear and accurate.Be sure the map clearly indicates theboundaries of the property in rela-tionship to standing structures orbuildings, natural features, or culturalfeatures. Include a drawn scale andnorth arrow on the map.

When the boundary is the same asa legally recorded boundary, refer tothat legal description of the propertyin the verbal boundary description.Citation of the legal description(beyond parcel number or block andlot number) and deed book referenceare optional. When natural or cul-tural features are used in definingboundaries, identify these features(such as street names, property lines,geographical features, or other lines ofconvenience) to designate the extentof the property. Begin at a fixedreference point and follow the perim-eter of the property, including dimen-sions and directions, in the verbalboundary description.

The verbal boundary descriptionmay refer to a large-scale map (such

as 1 inch to 200 feet) which shows theproperty boundaries. Large-scalemaps that show streets, rights-of-ways, property lines, and buildingfootprints are often available from thelocal planning agency or taxassessor's office. For large ruralproperties, a small-scale topographicmap, such as a USGS map, may beused. If such a map is not available,draw a sketch map to scale (prefer-ably 1 inch to 200 feet) and show thelocation of the resources relative tothe boundary and surroundingfeatures. Include a north arrow,drawn scale, and date on the map.

The verbal boundary description isfollowed by a justification of theselected boundaries. Explain how theboundaries were selected. Clarify anyissues that might raise questions, suchas excluding portions of the historicproperty because of lost integrity.

UNIVERSALTRANSVERSEMERCATOR (UTM)REFERENCES

Universal Transverse Mercator(UTM) references are required toindicate the location of the property.Generally, the UTM coordinates donot define the property boundaries,but provide precise locational infor-mation. Plot a single UTM referenceon a 7.5 minute series USGS map for asmall property; plot three or moreUTM references that define thevertices of a polygon encompassingthe area to be registered for propertiesover 10 acres. UTM references mayalso be used to define boundaries

(for example, large rural propertieslacking appropriate cultural ornatural features to define boundaries).When UTM references define bound-aries, the references must correspondexactly with the property's bound-aries. For additional guidance, seeNational Register Bulletin: How toComplete the National Register Registra-tion Form and National Register Bulle-tin: Using the UTM Grid System toRecord Historic Sites.

GLOBALPOSITIONINGSYSTEM (GPS)

The Global Positioning System(GPS) technology now can be used todefine boundaries for NationalRegister properties. GPS technologyrecords (digitizes) the location oflines, points, or polygons on theearth's surface using trilaterationfrom satellites orbiting the earth. Thelocational accuracy of the data variesbetween 2 and 5 meters (when usingdifferential correction). Thus, districtsand archeological sites can be digi-tized as polygons, and historic trainsor roads, as lines. The result is apotential National Register boundary.With GPS, the UTM references areautomatically calculated along withany other type of descriptive data,such as condition, materials, intru-sions, and integrity. Data from GPS isgenerally entered into a GeographicInformation System (GIS). Using GIS,boundary data can be combined withdata on cultural and natural features,such as roads, rivers, and land cover,to yield a composite map suitable forinclusion with the registration form.

III. CASE STUDIES

Many kinds of property types areeligible for inclusion in the NationalRegister, and different property typeshave different boundary issues to beconsidered. To illustrate a variety ofappropriate boundaries, examples aregiven for several property types. Foreach property type, the generalguidelines are presented. Appropri-ate examples are provided to illustratethe issues and solutions. The sum-mary information is abstracted fromregistration forms of properties listedin the National Register or documen-tation from properties determinedeligible for the National Register. Theverbal boundary descriptions andboundary justifications are quotationsof Section 10 of the registration forms.For some properties, such as archeo-logical sites, locational information isrestricted to protect the property.Examples drawn from such propertiesare edited to omit or alter locationalinformation.

BOUNDARIES FORBUILDINGS

Buildings are constructions createdprincipally to shelter any form ofhuman activity. The National Regis-ter use of the term "building" alsorefers to historically and functionallyrelated units, such as a courthouseand jail. Buildings include houses,barns, churches, schools, hotels,theaters, stores, factories, depots, andmills. Remember that many buildingshave associated contributing land-scape and archeological features.Consider these resources as well asthe architectural resources whenselecting boundaries and evaluatingsignificance of buildings.

The verbal boundary descriptionsand boundary justifications cited inthe following case studies provideexamples of boundaries for several

GUIDELINES FOR SELECTING BOUNDARIES: BUILDINGS

(summarized from How to Complete the National Register RegistrationForm, p. 56)

• Select boundaries that encompass the entire resource, including bothhistoric and modern additions. Include surrounding land histori-cally associated with the resource that retains integrity and contrib-utes to the property's historic significance.

• Use the legally recorded parcel number or lot lines for urban andsuburban properties that retain their historic boundaries andintegrity.

• For small rural properties, select boundaries that encompass signifi-cant resources, including outbuildings and the associated setting.

• For larger rural properties, select boundaries that include fields,forests, and open range land that is historically associated with theproperty and conveys the property's historic setting. The areasincluded must have integrity and contribute to the property'shistoric significance.

types of buildings in a variety ofsettings. In a few cases, the preparerhas elected to provide a large-scalemap (such as a tax map) that showsthe boundaries in lieu of a verbalboundary description.

Buildings in Urban Settings

La Casa Blanca, Coamo, PuertoRico, is a Spanish Creole vernacularhouse constructed in 1865. Character-istics of this style include a raised,wooden construction; main livingcore with rear service wing {martillo),forming an L-shaped plan with aninterior courtyard; full-length frontalbalcony or veranda; and hipped orside-gabled, usually high-pitched roofcovered with corrugated zinc. La

Casa Blanca includes these character-istics, except that the martillo opensinto the grounds at the southeastcorner of the lot and not into aninterior courtyard. The house islocated at 17 Jose I. Quinton Street,the corner of Quinton and Ruiz Belvisstreets. The boundaries of the Na-tional Register property follow thelegal lot boundaries. Verbal bound-ary description: The house isbounded in the north by Jose QuintonStreet; south, No. 18 FedericoSantiago Street; east, Ruiz BelvisStreet; and west, No. 19 Jose QuintonStreet. Boundary justification: Theboundary includes the entire city lotthat has been historically and iscurrently associated with the prop-erty.

United States Department of the InteriorNational Park Service

National Register of Historic PlacesContinuation Sheet

Section number Page _ Location Plan / Scale: 1:2000

Jr14

'fcrj .

lir

ftt.

inEP

La Casa Blanca, Coamo, Puerto Rico. City plan showing the National Registerboundaries (shaded lot).

J-ndian

I1>3>

r7

Dunbar SchoolFort Myers, Florida

Scale: 1 inch = 91 feet(approximate)

—i = boundary ofnominatedproperty

= photo # andcamera angle

Paul Lawrence Dunbar School,Fort Myers, Lee County, Florida, is atwo-story, T-shaped, Mission-stylebuilding built in 1927. The school wasbuilt as the first high school forAfrican American students in LeeCounty. The original building hasundergone few alterations and stillserves its original function as a publicschool. The present school complexincludes several buildings constructedin the 1950s, which are excluded fromthe nomination. The Paul LawrenceDunbar School is significant for itsassociation with African Americancommunity life and education in theFort Myers, Florida, area. Thisproperty illustrates boundariesincluding the historic core of a prop-erty but excluding peripheral, noncon-tributing buildings. Verbal boundarydescription: The boundary for theDunbar School is shown as the dottedline on the accompanying scale mapentitled "Site Plan, Dunbar School."Boundary justification: The bound-ary includes the building and immedi-ately adjacent grounds historicallyassociated with Dunbar School andexcludes that part of the original sitenow occupied by new construction.

Thomas I. Stoner House, DesMoines, Polk County, Iowa, is an early20th century Spanish Eclectic stylehouse. The Stoner house is significantas a rare example of its style, display-ing high artistic values and properlyexpressed design principles associatedwith the style, particularly the de-tailed stonework and balancedmassing with side wings. The houseis located on an irregular corner lot,overlooking Waveland Golf Course.The boundary for this property islimited to area that continues to beassociated with the house and ex-cludes areas historically separatedfrom the house. Verbal boundarydescription: The nominated propertyoccupies the eastern 31.4 feet of lot 53and all of lots 54, 55f and 56 inWaveland Hills in Des Moines and isroughly 168 x 181 feet in size. Bound-ary justification: The boundaryincludes the immediate grounds thathave historically been associated withthe property and that maintainhistoric integrity. At the time ofconstruction, the owner also ownedlots 52 and 57-60, property that waslater subdivided and therefore isexcluded from this nomination.

Paul Lawrence Dunbar School, Fort Myers, Florida. Plan showing the NationalRegister boundaries.

John D. Bush House, Exira,Audubon County, Iowa, is a two-story frame house built for John Bushby Danish immigrant carpenter JensUriah Hansen in the 1870s. When itwas built, the house was on theoutskirts of town and was part of alarger holding, which included Bush'sstock farm. The town expanded andnow encompasses the Bush propertywithin a residential area. Through theyears, the Bush holding has beensubdivided and the large lot on whichthe house is situated is all that re-mains intact of the original Bushholding. The property is significantas the best surviving example of theearly Danish immigrant dwellingsbuilt by Hansen, who was the firstDane to settle in Audubon Countyand was responsible for the construc-tion of several of the early buildings,homes, and outbuildings in the Exiraarea. The legal property boundarywas used to define the NationalRegister property boundary. Verbalboundary description: The nomi-nated property is bounded by thelegal description as recorded in theAudubon County Recorder's Office:Part of Lot 14, Subdivision of OriginalLot 9, Town of Exira, Section 4, T78N,R35W. Boundary justification: Theboundary of the nominated propertyis the remnant of the original parcelhistorically associated with theproperty.

Marshall Field Garden Apart-ments, Chicago, Cook County,Illinois, include ten buildings sur-rounding a spacious interior gardencourt, built in 1928-1929. The com-plex occupies two city blocks. Thebuildings are oriented towardSedgwick Street, the busiest of thestreets bordering the complex: twentystorefronts and offices face this street.The central interior courtyard runs thelength of the complex, with the smallinside courtyards of the eight H-shaped buildings opening on to thecentral courtyard. The two endbuildings extend the length of theblock. The complex is a notableexample of early privately funded,moderate-income housing in Chicago.The limits of the two city blocksoccupied by the apartments define theboundaries of the National Registerproperty. Verbal boundary descrip-tion: The area bounded by Sedgwick,Evergreen, Hudson, and Blackhawkstreets, starting at the northwestcorner of Blackhawk and Sedgwick,

1 6 8 . 6 RBtJl UJT LINE

\

KUGMMI

AVENUE

\

3 3 4 ' DRIVE STREET TOGMUCS ASCHM.T DRIVE

I

167.8' S6th SIHEET nORKE

Thomas I. Stoner House, Des Moines, Iowa. Plan showing the National Registerboundaries.

-H-

RESIDENCE OF STOCK. FARM

John D. Bush House, Exira, Iowa. Drawing of the house from the 1875 IllustratedHistorical Atlas of the State of Iowa: Eighth Congressional District (AndreaAtlas Company).

I -----,^L

ROAD CLASSIFICATION

Heavy-duty . „ _ _ . , „ Light-duty «™ =

Interstate Route '. U. S. Route State Route

CHICAGO LOOP, ILL.N4152.5—W8737 5/7.5

MARSHALL F(£LD GftRDCNJ I t.WTS

Marshall Field Garden Apartments, Chicago, Illinois. Detail of USGS quadranglemap showing the National Register boundaries.

extending south 938'9" to EvergreenStreet, extending west 263'9" toHudson Street, extending north 938' toBlackhawk Street and back east 263' tothe northwest corner of Blackhawkand Sedgwick. These dimensions aremeasured from the masonry edges ofthe buildings. Boundary justifica-tion: This acreage has historicallybeen associated with the MarshallField Garden Apartments.

Minto School, Minto, WalshCounty, North Dakota, was built in1895. The property includes theschool building with attached rearadditions and six noncontributingelements moved to the site in the past20 years and associated with theschool building's present use as theMinto Museum, operated by theWalsh County Historical Society. Themoved structures are arranged to thesouth and west (rear) of the schoolgrounds, where they do not affect theintegrity of the school's originalsetting. The National Register bound-aries include the 12 adjacent lotscomprising the north half of the cityblock occupied by the school and itsnewly associated buildings. Verbalboundary description: The north halfof block 11, Original Townsite, Minto,North Dakota, comprising lots 1-12.Boundary justification: The bound-ary includes the north half of block 11(lots 1-12), which has been historicallyand is currently associated with theproperty.

Buildings in Rural Settings

Theophilus Jones House,Newhaven County, Wallingford,Connecticut, is an 18th centuryfarmstead, which includes a house,barn, carriage house, carpentry shop,woodshed, pigeon house, icehouse,and well with washing terrace. Thehouse was constructed ca. 1740. Theproperty retains the character andfeeling of its period, because theproperty is bounded on the south byopen land and the arrangement of theoutbuildings blocks the view of morerecent residential construction to thenorth and east. The house faces JonesRoad, originally a farm road servingonly the house, which is now aresidential street. The immediateneighborhood is mostly residential,although there are farms and orchardsin the vicinity. The property issignificant for its association withWallingford's origins as an agricul-

10

tural community; its association withprominent 20th century resident andscholar of American decorative arts,Charles F. Montgomery; and itsembodiment of distinctive characteris-tics of Connecticut domestic architec-ture of the 1740s and 1750s. TheNational Register boundary corre-sponds to the legal block and lotdescription of the property. Verbalboundary description: The nomi-nated property includes the house,outbuildings, and associated lotknown as 40 Jones Road, shown asMap 085, Block 003, Lot 017 in theWallingford Assessor's records andrecorded in the land records inVolume 544, page 476. Boundaryjustification: The boundary includesthe farm house, outbuildings, andfarm yard that have historically beenpart of the Jones farm and thatmaintain historical integrity. Adjoin-ing parcels of the original farm havebeen excluded because they have beensubdivided and developed into aresidential neighborhood.

Chris Poldberg Farmstead, ShelbyCounty, Iowa, includes a house, barn,hog house, poultry house, machineshed, cob house, granary, and metalgrain bin. The farmstead was estab-lished in the early 20th century byDanish immigrants. The house issituated on the south side of thecluster of farmstead buildings andstructures, with the cob house situ-ated off the rear of the house withinthe yard. The west side of the clusterconsists of the poultry house, machineshed, and barn, with the grain bin,granary, and hog house forming thenorth side of the cluster. A dirt laneextends into the farmstead from thegravel road, bisecting the clusterbetween north and south halves.Historically, the entire area west,south, and east of the house had adense tree cover. The property'ssection, township, and range descrip-tion is used to locate the property;reasonable limits and cultural features(roads) are used to define the Na-tional Register boundaries. Verbalboundary description: The topo-graphic location of the nominatedproperty is as follows according to theUSGS quadrangle map, Prairie RoseLake, Iowa 1978: E 74, SE 74,SE 74, NE 74 of Section 27, T79N,R37W, Jackson Township, ShelbyCounty, Iowa. The specific propertyboundary is described as follows:Beginning at a point 10 feet north ofthe hog house and starting at the west

PlumbushHudson Highlands MRARoute 9D, PhilipstownPutnam County, New York

^ MAP 2 - Tax map showing property boundaries for Plumbush

U4AC /,) '"

2,94 AC. A \ \

Plumbush, Philipstown, New York. Tax map showing the National Registerboundaries.

edge of the gravel road proceed west300 feet, turn south for 300 feet, turneast for 300 feet to the west edge ofthe road, and turn north for 300 feet tothe point of beginning. Boundaryjustification: The boundary of thenominated property includes thatportion of the historic farm holdingsthat encompasses all of the buildingsand structures of the farmstead itself.

Plumbush, Putman County, NewYork, consists of two contributingbuildings, a mid-19th century farm-house and an associated wood house.The original carriage house has beenextensively remodeled for use as agarage and is, therefore, noncontrib-uting, as is a modern two-story house,which is separated from Plumbush bya wooded area. The surroundingneighborhood is rural, with fewresidences located nearby. Theproperty is bounded on the north,northeast, and south by the ColdSpring Cemetery; on the west byRoute 9D; on the south by Moffet

Road; and on the east by privateproperty. Much of the original 65-acre farm has been subdivided, andextensive infill has destroyed thehistorical integrity and setting of thelarger farm. The limits of the taxparcel that includes the eligibleresources define the boundaries of theNational Register property. Verbalboundary description: Plumbush islocated on the east side of Route 9Dbetween the intersections of Peekskilland Moffet roads. The nominatedproperty includes two adjacent taxparcels which comprise 9.3 acres asshown on accompanying tax map.Boundary justification: Historically,Plumbush was part of a 65-acre farmowned by Robert Parker Parrott.Over time, much of the property wassubdivided and sold off. Extensivemodern infill on the original farmacreage has destroyed the historicalintegrity and setting of the largerfarm. The 9.3-acre nominated prop-erty is all that remains of the originalfarm associated with the house.

11

_jkL-3i»

\:

The Church of Saint Dismas, The GoodThief, Dannemora, New York. Detail oftax map showing the National Registerboundaries.

Church of St. Dismas, The GoodThief, Dannemora, Clinton County,New York, is a large, stone chapel onthe grounds of the Clinton Correc-

tional Facility. The chapel, whichwas completed in 1941, was built onthe site of the abandoned prison farmbuilding along the north edge of theprison grounds within the walls; 1.07acres were set aside for the building,and the boundary of the nominatedproperty coincides with the lot linesdrawn around the 1.07 acres whenthe church was built. The boundaryencompasses three additional historicfeatures directly associated with thechapel: a greenhouse, a terracedstone wall, and a grotto. The remain-der of the Clinton CorrectionalFacility, established in 1845, had notbeen surveyed at the time the chapelnomination was prepared nor evalu-ated for National Register eligibility;therefore, only the chapel and itsgrounds are included in the nomi-nated property. Verbal boundarydescription: Heavy black outline onattached county tax map definesboundary of nominated property.Boundary justification: The bound-ary is drawn to coincide with the1.07-acre parcel which was delineatedwhen the prison farm was abandonedand the church was constructed.

BOUNDARIES FORHISTORICDISTRICTS

A historic district possesses asignificant concentration or continuityof sites, buildings, structures, orobjects united historically or aestheti-cally by plan or physical develop-ment. Districts may include severalcontributing resources that are nearlyequal in importance, as in a neighbor-hood, or a variety of contributingresources, as in a large farm, estate, orparkway. Noncontributing resourceslocated among contributing resourcesare included within the boundaries ofa district. When visual continuity isnot a factor of historic significance,when resources are geographicallyseparate, and when the interveningspace lacks significance, a historicdistrict may contain discontiguouselements. (See National RegisterBulletin: How to Complete the NationalRegister Registration Form for furtherdiscussion about defining a district.)

GUIDELINES FOR SELECTING BOUNDARIES:HISTORIC AND ARCHITECTURAL DISTRICTS

(summarized from How to Complete the National Register Registration Form, pp. 56-57)

Select boundaries that encompass the single area of land containing the significant concentration of buildings,sites, structures, or objects making up the district. The district's significance and historic integrity should helpdetermine the boundaries. Consider the following factors:

• Visual barriers that mark a change in the historic character of the area or that break the continuity of thedistrict, such as new construction, highways, or development of a different character.

• Visual changes in the character of the area due to different architectural styles, types or periods, or to adecline in the concentration of contributing resources.

• Boundaries at a specific time in history, such as the original city limits or the legally recorded boundaries ofa housing subdivision, estate, or ranch.

• Clearly differentiated patterns of historic development, such as commercial versus residential or industrial.

A historic district may contain discontiguous elements only under the following circumstances:

• When visual continuity is not a factor of historic significance, when resources are geographically separate,and when the intervening space lacks significance: for example, a cemetery located outside a rural village maybe part of a discontiguous district.

• When cultural resources are interconnected by natural features that are excluded from the NationalRegister listing: for example, the sections of a canal system separated by natural, navigable waterways.

• When a portion of a district has been separated by intervening development or highway construction andwhen the separated portion has sufficient significance and integrity to meet the National Register Criteria.

12

National Register properties classifiedas districts include college campuses,business districts, commercial areas,residential areas, villages, estates,plantations, transportation networks,and landscaped parks. Historicdistricts often include contributingarcheological resources that should beconsidered when evaluating signifi-cance and selecting boundaries.Examples of such properties areincluded in the discussions of districtsin rural settings. Examples of archeo-logical districts are presented in thediscussion of archeological sites.

Boundaries of historic districts areoften difficult to describe verbally.Consider using a scale map instead ofa narrative verbal boundary descrip-tion to define the boundaries.

Contiguous Districts in UrbanSettings

Taylorsville Historic District,Taylorsville, Spencer County, Ken-tucky, encompasses 34 contributingbuildings and 2 contributing sites inthe center of the town. The districtincludes the contiguous, intact,historic resources at the center of thecommunity, which comprise theresidential, commercial, governmen-tal, and religious resources thatdocument the development ofTaylorsville from its early daysthrough the 1930s. These buildings,along with the streets, alleys, and lotson which they are located, provide anexcellent picture of the developmentof Taylorsville from 1818, the date ofthe earliest extant house, to 1938, theconstruction date of the most recenthistoric building in the district. Thedistrict is eligible under Criterion Abecause it reflects the effects of anumber of key events in the town'shistory, including designation in 1824as the seat of newly formed SpencerCounty and the destruction andrebuilding of its commercial area andcourthouse after fires in 1898,1899,and 1913. The district also reflectsgradual trends, such as changingpatterns in siting and housing typesand styles and the development of thecommunity into a commercial andsupply center for the surroundingagricultural county- The district isalso significant for its representationof community planning and develop-ment: the streets, lots, and buildingsin the district document Taylorsville'sgrowth from a tiny, early 19th centurysettlement to an antebellum govern-ment center and into a small early

20th century county seat. Legal lotdescriptions and a reasonable limitwere used to define the boundaries ofthe National Register district. Verbalboundary description: The district isclearly delineated on the accompany-ing sketch map. With one exception,it follows the rear property lines ofthe properties included in the district.At the Enoch Holsclaw House onGarrard Street (#1), the western 50feet of the property where a 1980shouse is located have been excluded.Boundary justification: Excludedfrom the district are other areas ofhistoric Taylorsville where smallpockets of historic buildings andindividual buildings have beenisolated from the district bynonhistoric construction. The historicdevelopment along Main Cross Streetnorth of Main Street was consideredfor inclusion in the district but deter-mined ineligible. Although the areacontains a number of historic andcontributing buildings including theTaylorsville Public Library, All SaintsChurch, and some historic houses, thelarge percentage of nonhistoric andother noncontributing buildings alongthe street makes it a poor representa-tion of the historic character of thetown. Two other collections ofhistoric buildings have also beenconsidered for National Registerlisting but considered ineligible.Along Reasor Street and MapleAvenue, in an area developed begin-ning in 1899 as "Reasor's Addition/'is a collection of small, modest housesdating from about 1900 through the1940s. A large number of thesehouses have been seriously altered bythe addition of new siding, majorchanges to front porches, and lateraladditions that alter the form of thehouse. They no longer constitute anintact historic district. At the east endof Main Street, east of Railroad Street,is another collection of 12 historichouses. Although many of thesehouses retain a significant number oftheir identifying features, it wasdetermined that they were too dispar-ate a group, with no theme to unitethem, to justify a district. Ten historicbuildings in Taylorsville have beendetermined to be individually eligiblefor the National Register and will benominated as part of the currentproject. The district encompasses thecontiguous intact historic propertiesalong Main Street and Garrard Streetthat help to document the district'sarea of significance—community

planning and development. Thedistrict boundaries are determined byconcentrations of nonhistoric proper-ties that surround the district on allsides. To the east are nonhistoric andnoncontributing commercial build-ings. To the south is the 1948 floodwall. To the west, a few remaininghistoric houses are interspersed withseveral nonhistoric governmentalbuildings, including a post office andSpencer County School office and anumber of late 1940s infill houses.To the north along Washington Streetand Main Cross Street, a number ofhistoric houses at the north ends ofthe streets are separated from thedistrict by a 1950s church and single-family houses and apartments, alldating from the late 1940s through the1980s.

Taylorsville Historic District,Taylorsville, Kentucky. Detail of SpencerCounty Property Identification Map T-2showing contributing and non-contributing resources, photo views, andNational Register boundaries.

13

Bay Shore Historic District,Miami, Dade County, Florida, in-cludes 201 single-family residencesand 70 outbuildings. The district,which is located about 3 V2 milesnorth of downtown Miami, representsa wide variety of early 20th centuryarchitectural styles, including Medi-terranean Revival, Art Deco, ColonialRevival, Mission, and MasonryVernacular. The 90-acre district isroughly bounded by N.E. 55th Streeton the south, Biscayne Boulevard onthe west, N.E. 60th Street on thenorth, and Biscayne Bay on the east.The Bay Shore Historic District issignificant at the local level underCriterion A as one of Miami's mostintact historic neighborhoods and thecity's best extant example of aplanned, Boom-era suburb thatcontinued to develop in the yearsprior to World War II. The district isalso significant under Criterion C forits wealth of Mediterranean Revival,Art Deco, and Masonry Vernacularstyle houses that reflect the diversityand evolution of architectural designin South Florida during the 1920s and1930s. The National Register bound-aries, defined on a map, are based onassessments of historic boundariesand modern setting. Verbal bound-ary description: The boundary of theBay Shore Historic District is shownas the heavy line on the accompany-ing map entitled "Bay Shore HistoricDistrict." Boundary justification:The boundaries of the Bay ShoreHistoric District have been drawn togenerally follow those of the originalBay Shore subdivisions, plattedbetween 1922 and 1924, and the BayShore Plaza subdivision, platted in1936. Excluded from the district arethose portions of the Bay Shoresubdivisions located west of BiscayneBoulevard, which is now a majorcommercial area. The proposedboundaries encompass those portionsof the present Bay Shore neighbor-hood that contain a predominance ofbuildings constructed between 1922and 1942. The plan and period ofsignificance clearly set the Bay ShoreHistoric District apart from its sur-roundings. The boundaries of thedistrict are based on boundaries at aspecific time in history, visualchanges, and visual barriers. N.E.60th Street was selected as the north-ern boundary because it is the north-ern limit of the earliest Bay Shoresubdivision. Furthermore, the areanorth of this street contains few

53 ST.

NATIONAL REGISTERDISTRICT BOUNDARIES

CONTRIBUTING RESOURCE

IBUTING RESOURCE

Bay Shore Historic District, Miami, Florida. Detail of map showing a portion of thedistrict's National Register boundary.

historic buildings and is of a differentcharacter, containing a number ofmulti-family buildings. On the east,Biscayne Bay and Morningside Parkform natural physical boundaries, aswell as significant historic boundaries.The bayfront lots help to define thecharacter of the district, and theirpresence was a major factor in thedistrict's development. MorningsidePark is not included because it wasnot opened until 1951, although thenorthern portion was acquired by thecity in 1935. The rear property linesbetween N.E. 55th Street and N.E.53rd Street were chosen as the south-ern boundary because they delineatethe southern limit of the Bay ShorePlaza subdivision. In addition, themajority of houses south of this linewere constructed after 1942. Finally,Biscayne Boulevard was selected asthe rough western boundary becausea majority of the development onBiscayne Boulevard is of a differentcharacter. Since the mid-1960s,Biscayne Boulevard has developedinto a major thoroughfare with officezoning, and many of the newerbuildings are large-scale office orresidential structures. Several historicstructures do remain, however, andthese have been converted into officeuse. That portion of the original BayShore subdivision west of BiscayneBoulevard was excluded because it nolonger contains a concentration ofhistoric buildings.

Clifton Townsite Historic District,Clifton, Greenlee County, Arizona,clearly defines an intact grouping ofbuildings of various types datingfrom the early years of Clifton'sdevelopment, 1871-1920. Theseresources lie within the bottom of thecanyon formed by the San FranciscoRiver at its intersection with ChaseCreek. This low-lying location, whilegiving the town a visual boundary,has subjected it to periodic flooding.This has had the greatest impact alongPark Avenue where many buildingshave been washed away in the past.Many aspects of Clifton are repre-sented by the various buildings andstructures: residential, commercial,industrial, transportation, religious,and governmental buildings areincluded as well as character-definingengineering works such as bridgesand flood-control features. Remain-ing buildings represent a variety oflate 19th and early 20th century styles.The physical setting in the canyonalong the San Francisco River as wellas the relative proximity and visualcontinuity of the structures unifies thedistrict. The general architecturalintegrity of the district is good,although many properties are aban-doned and have fallen into disrepair:32 of the 86 resources are noncontrib-uting. The district is significant underCriterion A for its association with theearly copper mining and smeltingoperations in that region and with the

14

town that grew to support thoseoperations. The district is additionallysignificant under Criterion C for itsintact examples of architecture typicalof Arizona's mining towns. Two siteswithin the district, the smelter ruinsand a commercial building ruin, aresignificant under Criterion D asabove-ground remnants which revealimportant information about signifi-cant aspects of the district. Thedistrict's period of significance beginswith the construction of the earliestremaining structure in 1874 and endswhen the copper smelter moved toMorenci in 1937. The NationalRegister boundaries are defined on amap; natural and cultural featureswere used to define the property.Verbal boundary description: Theboundary of Clifton Townsite HistoricDistrict is shown as the dashed line onthe accompanying map entitled"Clifton Townsite Historic District."Boundary justification: The bound-ary includes the properties within anarea in central Clifton that retainintegrity and are associated with thefunctioning of Clifton as a majorcopper smelting center. The boundaryexcludes, where possible, propertiesthat have lost integrity and/or haveno significance. Beginning at thenorthwest boundary of the district, thecliffs form a natural and well-definedlimit encompassing the visible rem-nants of the smelter and associatedstructures. Proceeding clockwise, thenorthern limit of the district is markedby the transition from industrial usesto a residential area that containsmodern and historic houses of poorintegrity. At the point at which thefloodwalls appear at the east bank ofthe San Francisco River, the boundaryincludes the riverbed and floodwall.The northeast boundary may bedivided into two parts: at the northend, geographic limits of the cliff sidedefine the boundary, no furtherstructures being visible uphill; to thesouth, the slope becomes less steepand additional structures, eithermodern or of poor integrity, appearuphill from Park Avenue. Propertiesone-lot-width uphill from ParkAvenue are included within thedistrict, because all properties, evennoncontributors/are an importantpart of the Park Avenue Steetscape.At the southernmost end of ParkAvenue, no structures exist at thenortheast side of the street and theboundary is drawn to exclude thisopen land. The boundary continues

Clifton Townsite Historic District, Clifton, Greenlee County, Arizona. Map showingthe National Register boundaries.

south, excluding open land, butincluding the east floodwall south toits end. The southern boundary isdefined by a line connecting thesouthernmost ends of the formallyconstructed floodwalls at both sidesof the San Francisco River (slag-rubble walls continue to the souththrough much of the town). Thislocation coincides with a constructionin the width of the canyon, a bend inthe river, and a break in continuity ofdevelopment from the remainder ofthe town to the south. The boundarycontinues northwest along the west-ern floodwall, excluding the site of theformer freight depot (now demol-ished). The boundary then is drawnto include the passenger depot,following the geographic boundary ofthe cliffside, which firmly delineatesthe boundary at this location. At the

point where the canyon of ChaseCreek and the San Francisco Rivermeet, the boundary is drawn at theedge of U.S. Route 666 to exclude anarea of intruded properties that stepup the cliffside, which is not as steepat this point. At the south side of theChase Creek commercial area, theproperty line or street curbline andthe cliffside largely coincide to definethe edge of development in Clifton.The westernmost termination of thedistrict at Chase Creek is drawn at theend of the area of dense commercialcharacter of Chase Creek and at thewesternmost extant of the stoneretaining wall at the cliffs north ofChase Creek. This location coincideswith a restriction in the width of thecanyon and a corresponding pause inthe continuity of development sitesfrom development further west.

15

Elm Hill, Wheeling, Ohio County,West Virginia, is a mid-19th centuryGreek Revival mansion on a secludedesplanade. The area, which washistorically farmland, is now part ofsuburban Wheeling. The grounds arelandscaped lawn with shade trees,evergreens, and shrubs. The associ-ated brick springhouse/smokehouse,barn/garage, and cemetery arecontributing resources. The legalproperty description was used todefine the National Register bound-aries of the property. Verbal bound-ary description: The nominatedproperty is inclusive of the 19.33-acretract identified as parcel #7, sur-rounded by acreage of the WheelingCountry Club, on Ohio Countyassessor's Map RD-14, RichlandDistrict, February 1960, Wheeling,West Virginia. Boundary justifica-tion: The property is inclusive ofbroad lawns and open areas that forma significant setting between BethanyPike and the rear property lines.Within this green space stand thehouse, smokehouse/springhouse,barn, and cemetery.

Discontiguous Districts in UrbanSettings

Plemons—Mrs. M. D. Oliver-Eakle Additions Historic District,Amarillo, Potter County, Texas,includes about 40 blocks of residentialdevelopment originally platted as thePlemons Addition (1890) and the Mrs.M. D. Oliver-Eakle Addition (1903).The district is characterized by aneclectic mix of modestly scaleddwellings representing architecturalstyles of the early 20th century. Thehistoric landscaping reinforces theneighborhood's cohesiveness. De-spite the intrusion of a major arterialhighway (which separates the districtinto two discontiguous parts), thehistoric district retains a high level ofits historic integrity, with 357 of 535resources classified as contributingelements. The district is one ofAmarillo's most intact early 20thcentury residential neighborhoods.The design, scale, and materials of thebuilding stock reflect the cyclicaldevelopment of Amarillo's economyfrom the turn of the century to thebeginning of World War II. Thepredominant Prairie School andCraftsman-influenced bungalowstyles reflect Amarillo's growth fromthe 1910s through the 1930s as re-gional discoveries of oil and natural

SK RD-IT

Elm Hill, Wheeling, West Virginia. Tax map showing the National Registerboundaries.

Plemons—Mrs. M. D. Oliver-Eakle Additions Historic District, Amarillo, Texas.Detail of USGS map showing the National Register district boundaries and UTMreferences.

16

gas augmented agriculturally basedwealth. The district is nominated tothe National Register under Criteria Aand C. The National Register bound-aries of this discontiguous districtfollow existing roadways that encom-pass the eligible resources. Verbalboundary description: As indicatedby the solid black lines on the accom-panying USGS map, the historicdistrict is comprised of twodiscontiguous elements divided byInterstate Highway 40. The northernportion of the historic district encom-passes 86 acres bounded by thefollowing parameters: Beginning atthe center point of the intersection ofE. 16th Avenue and S. Taylor Street,proceed south along the center line ofSouth Taylor Street continuing to itsintersection with the center line of theNorth Access Road of InterstateHighway 40; thence southwest andwest along the center line of the NorthAccess Road of Interstate Highway 40to its intersection with the center lineof the alley west of S. Madison Street;thence north through the alley alongits center line to its intersection withthe center line of W. 16th Avenue;thence east along the center line of16th Avenue until reaching the pointof beginning. The southern portion ofthe historic district encompasses 94acres bounded by the followingparameters: Beginning at the centerpoint of the intersection of S. TaylorStreet and E. 26th Avenue, proceedwest along the center line of 26thAvenue continuing to the point of itsintersection with the alley west of S.Van Buren Street; thence norththrough the alley along the center lineto its point intersection with W. 24thAvenue; thence east along the centerline of W. 24th Avenue to its point ofintersection with S. Van Buren Street;thence north along the center line of S.Van Buren Street to its intersectionwith the center line of the SouthAccess Road of Interstate Highway 40;thence east and southeast along thecenter line of the South Access Roadof Interstate Highway 40 to the pointof its intersection with S. TaylorStreet; thence south along the centerline of S. Taylor Street until reachingthe point of beginning. Boundaryjustification: Consisting of twodiscontiguous elements currentlydivided by the incursion of InterstateHighway 40, the Plemons—Mrs. M.D. Oliver-Eakle Additions HistoricDistrict encompasses a cohesivecollection of residential properties

dating to the early 20th century.District boundaries coincide withconcentrations of historic propertieswithin the original limits of thePlemons Addition and the Mrs. M. D.Oliver-Eakle Addition to the City ofAmarillo. The boundaries encompassthose portions of the neighborhoodthat retain a significant degree ofintegrity of historic setting and feelingstrengthened by the continuityprovided by historic streetscapes.Areas beyond these boundariesgenerally consist of properties whosecharacter differs from those within thehistoric district, including residencesthat exhibit loss of historic integrity orwere built following the historicdevelopment period of the neighbor-hood. Properties outside the historicdistrict also include functionallydifferent resources, such asnonhistoric commercial propertiesand large-scale institutional proper-ties. Changes in the historic residen-tial character of the neighborhoodestablish the boundaries on all sides.The northern boundary along 16thAvenue demarcates the transitionbetween the commercial and institu-tional character of Amarillo's centralbusiness district and the residentialneighborhoods in the southernreaches of the city. The easternboundary along Taylor Street coin-cides with the dissolution of historicresidential character prompted by theincursion of Interstate Highway 27.Numerous noncontributing commer-cial and residential properties com-promise the integrity of the area eastof this boundary. The southernboundary along 26th Avenue occursat the point of transition betweenresidential properties developedduring the early 20th century andthose developed in the 1940s, 1950s,and 1960s. On the west, the districtboundary coincides with the limits ofresidential development with the Mrs.M. D. Oliver-Eakle Addition, as thecampus of Amarillo College hems inthe neighborhood along this bound-ary. Interstate Highway 40, whichobliterated portions of the historicneighborhood between 18th and 19thAvenues, is excluded from the historicdistrict and divides it into dis-contiguous components. North ofInterstate Highway 40, the westernboundary falls along the alley west ofMadison, which separated historicresidential development from non-contributing commercial developmentalong Washington Street.

Contiguous Districts in RuralSettings

Woodlawn Historic and Archaeo-logical District, King George County,Virginia, is a 899-acre historicriverfront plantation along the northbank of the Rappahannock River andthe west bank of Gingoteague Creek.Woodlawn is among the oldestplantations in the county and retainsessentially the same boundaries it hadwhen the land was first consolidatedin the late 18th century. The propertyincludes 21 buildings, sites, andstructures: the planation house,dating from ca. 1790, and its early tomid-19th century ancillary buildings,with major additions and renovationsto the plantation house ca. 1841,1934,and 1982. There are 6 contributingbuildings, including the plantationhouse and two antebellum outbuild-ings and slave quarters and an early20th century barn and implementshed. The 10 contributing archeologi-cal and landscape sites include 5prehistoric sites, a historic domesticsite, a ditch network, the field system,the farm road network, and aspringhouse foundation site. Thereare 3 noncontributing buildings, 1noncontributing site, and 1 noncon-tributing structure. Periods of signifi-cance are represented by contributingprehistoric Native American re-sources and the historic resources ofthe 17th century and of the late 18thcentury through 1937. WoodlawnHistoric and Archaeological District iseligible under Criteria A, C, and D atthe state and local levels. The well-preserved plantation house is one of anumber of important and interrelatedhouses built along the RappahannockRiver between 1760 and the 1850s. Inaddition to its architectural signifi-cance, the district also represents thehistorical influence of agriculture andtransportation on the settlement andeconomy of the Northern Neck ofVirginia. Woodlawn is also signifi-cant for its association with theTurner family, whose history inVirginia dates to the mid-17th centuryand whose occupation of Woodlawnlasted into the 1920s. The Turnerswere members of an extended familyof prominent landowners who left animportant architectural legacy in thearea. The social and cultural values ofthe antebellum planter class arereflected in the architectural traditionsof Woodlawn. The patterns ofresidential, agricultural, and wood lot

17

land use persist today. Field patterns,vegetation, and drainage ditchesdating from the period of significancesurvive. Natural and cultural featuresand reasonable limits were used todefine the National Register bound-aries of this large rural property.Verbal boundary description: Theboundary of Woodlawn Historic andArchaeological District begins at thenorthern bank of the RappahannockRiver at UTM 18 309780 4226640; andcontinues north/northeast until itintersects the drainage ditch (Archeo-logical Site 44KG94) at UTM 18309910 4227160; and continues north/northeast along the western edge ofthe ditch until it intersects a tributaryof Gingoteague Creek at UTM 18310380 4228360; and continues north/northeast until it intersects a dirt roadat UTM 18 310560 4228890; andfollows the western edge of the dirtroad until it intersects State Route 625to UTM 18 310645 4229165; andcontinues west along the northernedge of State Route 625 to UTM 18310645 4229240; and continues north/northeast to UTM 18 310600 4229520;and continues east until it intersectsthe northern edge of State Route 625at UTM 18 310730 4229430; andcrosses State Route 625 and followsthe southern edge of State Route 625to UTM 18 310830 4229380; andcontinues south/southwest to UTM18 310675 4228845; and continues eastto UTM 18 311220 4228820; andcontinues north/northeast to thesouthern edge of State Route 625 atUTM 18 311300 4229240; and contin-ues west along the southern edge ofState Route 625 to UTM 18 3112404229240; and continues northeast,crossing State Route 625, to UTM 18311490 4229495; and continuessoutheast to UTM 18 311520 4229430,east to UTM 18 311560 4229450,southeast to UTM 18 311610 4229325,east to UTM 18 322735 4229270, andsoutheast, crossing State Route 625, tothe southern edge of State Route 625at UTM 18 311760 4229220; andcontinues east along the southernedge of State Route 625 until itintersects the Gingoteague Creek atUTM 18 311830 4229230; and contin-ues south along the center of theGingoteague Creek until it intersectsthe Rappahannock River at UTM 18312045 422660; and continues eastalong the northern bank of theRappahannock River to UTM 18309780 4226640. Verbal boundaryjustification: The boundary chosen

\

Woodlawn Historic and Archaeological District, King George County, Virginia.Detail of USGS map showing contributing resources and the National Registerboundaries.

for the Woodlawn Historic andArchaeological District correspondsto traditional and current propertylines. Significant contributinghistoric and archeological resourcesare contained within these bound-aries.