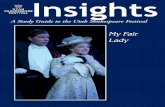

My Fair Lady Research Paper

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of My Fair Lady Research Paper

Juhasz

Aubri Juhasz

Professor Stacey McMath

New York Theater

23 October 2014My Fair Lady

In 1913, George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, a “shameless

potboiler,” was written to simply “oblige theater managers

or aspiring players,” (Weintraub 194). (Garbian 12). Today

the implications of Shaw’s Pygmalion amount to far more than

a few “obliged” managers and players. Over the past nine

decades, My Fair Lady has emerged and endured through

adaptations from page to stage to screen. A lasting standard

of excellence, in literature, drama, music and film, My Fair

Lady was once deemed by the New York Times as “the perfect

musical,” (Hogan 8) and to this day remains the ideal model

of the quintessential Broadway Musical.

My Fair Lady has many fathers beginning with the

chroniclers of classical Greek literature. Greek myth states

a sculptor, Pygmalion, enamored by his ivory creation of a

sculpted woman prays to Aphrodite to give it animation.

1

Juhasz

Pygmalion himself possesses a fierce hatred for women, whom

he regards as prostitutes and finds only his “sculpted

woman,” to be pure. The statue named Galatea, now a woman,

marries Pygmalion and the two have one son by the name of

Paphus. Some versions of the myth such as the 1767 retelling

of Goethe refer to Galatea by the name of Elise, suggesting

the etymology of the name “Eliza” in Shaw’s version, (McHugh

1). In addition to classical mythology, Shaw’s play and

ultimately the story of My Fair Lady, draw inspiration from

W.S. Gilbert’s Pygmalion and Galatea (1871). It is critical to

acknowledge according to historian Keith Garbian, “Shaw’s

characters, dialogue, and plot are marked by his own

distinctive wit and genius,” (Garbian 12). The play

emotionally draws heavily from Shaw’s personal life and his

relationships with Mrs. Pat Campbell, a stage actress, born

Beatrice Stella Tanner. Campbell served as Shaw’s muse for

Eliza in Pygmalion as well as the leading ladies in The Devil’s

Disciple, Heartbreak House and Back to Methuselah. Shaw’s infatuation

went unconsummated though the two felt strongly for one

another and his conflicting emotions of love and hate for

2

Juhasz

Campbell are mirrored in the relationship of Eliza and

Higgins.

Shaw’s comedy was self-described as “intensely and

deliberately didactic,” and its public and commercial

success only supporting his claim that “great art can never

be anything but didactic,” (Garbian 12). The story of

Pygmalion integrates “Faustian legend with Cinderella fairy-

tale, and puts an emphasis on themes of linguistic and class

distinction,” says Garbian, (Garbian 12). Shaw used his

skills as a dramatist to recreate Pygmalion myth in the

Edwardian sphere, spinning a tale of the godlike powers of

transformation. “Both Pygmalion and Higgins feel nothing

short of contempt for the opposite sex, and yet - or perhaps

as a result of this - they both lavish their special talents

on creating the ideal image of a woman,” (McHugh 1). In

classical myth, it is Aphrodite whose powers transform an

inanimate woman of ivory into flesh and blood. In My Fair

Lady, it is Dr. Henry Higgins who attempts to test his

powers of transformation when he makes a bet with his fellow

3

Juhasz

linguist Colonel Pickering that he can pass off a cockney

flower girl as a socialite.

The genesis of My Fair Lady begins with a man by the name

of Gabriel Pascal. A destitute filmmaker, the Hungarian had

struck a deal of sorts with Shaw in the early 1920’s when

swimming at Cap d’Antibes on the French Riviera, (Garbian

16). In conversation, Pascal revealed that he was “fighting

rather a hopeless fight in the métier of producing films.”

Shaw responded, “If one day you are finally driven to the

conclusion that you are utterly broke, and there is no doubt

that you will be, come and call on me. Maybe then I will let

you make one of my plays into a film,” (Garbian 16). In

1935, Shaw honored his gentleman’s agreement allowing the

penniless film maker who he deemed “the first honest film

producer” he had ever met, the right to produce and adapt

Pygmalion among several other of his plays for the silver

screen. Despite romanticizing the relationship of Higgins

and Eliza, the film remained true to Pygmalion. The film

broke box office records, garnered Shaw celebrity status and

4

Juhasz

earned an Oscar for Shaw’s screenplay and a Volpi Cup at the

1938 Venice Film Festival, (Garbian 22).

It seemed logical to Pascal to “exploit his success”

(Garbian 24), with Pygmalion. Shaw had refused to grant a

musical adaptation of his work for he feared the form and

texture would be distorted. Biographer Michael Holroyd

states, “Shaw made the same reply to all composers and

resisted every pressure to ‘degrade’ his play into a

musical. ‘I absolutely forbid any such outrage,’ he wrote in

his ninety second year. Pygmalion was good enough ‘with its

own verbal music,’” (Holroyd 8). Without Shaw’s blessing

Pascal schemed to produce an adaptation of Pygmalion for

musical theater. Intent on another success, Pascal sought

out the legendary duo of Lerner and Lowe, the men whom he

believed would take Pygmalion from the silver screen to the

Broadway stage.

On a quiet afternoon in the early spring of 1952,

Pascal ordered Lerner to join him for lunch in Tinseltown at

the restaurant Lucy’s, (Garbian 25). After a brief meeting

and three plates of pasta, Pascal proclaimed, “We will meet

5

Juhasz

again and you will bring man who writes music,” (Garbian

25). This signaled the beginning of a creative relationship

between the duo of Lerner and Lowe and the Hungarian

filmmaker Pascal.

Alan Jay Lerner, an American librettist and lyricist,

was born in New York City and attended The Choate School and

Harvard. Lerner grew to have only one passion, “to be

involved, someday, somehow, in the musical theater,” (Lees

20). His father, a chauvinist, cultivated a love in his son

for all things English. My Fair Lady would prove his most

personal and enjoyable project, the one he had waited his

entire career for. Frederick Lowe an Austrian-American

composer was a former concert pianist and struggling

composer when he met Lerner and the two entered into a

partnership that would last decades. Prior to My Fair Lady,

Lerner and Lowe had written two unmemorable musicals Life of

the Party (1942) and What’s Up (1943), an almost hit, The Day

Before Spring (1945), and two hits, Brigadoon (1947) and Paint

Your Wagon (1951), (Garbian 27). My Fair Lady would prove to be

their biggest success yet.

6

Juhasz

Pygmalion proved a challenge for the duo and the two

lost momentum and interest. Their fears were confirmed when

the great Hammerstein of the Rogers and Hammerstein duo

said, “It can’t be done, Dick (Rogers) and I worked on it

for over a year and gave up,” (Garbian 29). The project

remained abandoned until Pascal’s death in the summer of

1954, (Garbian 32). In the time since they had abandoned the

idea of a musical of Pygmalion, many of its original problems

had worked themselves out. Theater had changed and a story

of realism rather than idealism was more appealing among

Americans. It was a new age in American theater, an age just

right for My Fair Lady.

Writing of the script and score proceeded without

rights to Shaw’s story. Shaw had passed rights to Pascal for

a screenplay but rights to the characters and plot remained

a part of Shaw’s London estate. Thus for both men, full

rights to the story of Pygmalion that would soon become My

Fair Lady meant securing rights from both the Shaw and Pascal

estates. The Chase Manhattan Bank had been named the

executor of Pascal’s will. Metro Goldwyn-Mayer (M.G.M.) was

7

Juhasz

interested in producing another film version of the work and

had already given generously to the bank in hopes of

securing a favored position, (Garbian 30). The rights of the

production were uncertain but the duo was certain of one

thing. If they had fully written and composed a musical

version of Pygmalion prior to the settlement of the estates,

their chances at acquiring the rights would be greater; they

simply wouldn’t have just an idea but rather a tangible

product. “We will write the show without the rights,” said

Lerner. “When the time comes for them to decide who is to

get them, we will be so far ahead of everyone else that they

will be forced to give them to us,” (Lerner 47). Racing

against the clock, the duo assembled a creative team and set

to work.

The team of two L’s changed to three when on October

11, 1954; Herman Levin announced that he would serve as

producer for Lerner and Lowe’s musical version of Pygmalion.

Prior to this arrangement, negotiations had been considered

to allow for production of the musical version of Pygmalion

to be done by the Theatre Guild, but due to difficulties

8

Juhasz

over the royalty agreement they fell through. Lerner

claimed “that everybody else ‘held firm on their royalty and

only the author was asked to accept less than minimum. My

ego was not troubled, but my sense of fairness was

definitely jarred.’ He added triumphantly: ‘Suffice to say I

have improved my lot with Herman Levin,’” (McHugh 20).

Herman Levin was a producer of unique origin. Prior to

the age of 39, Levin possessing a law degree worked as a

bureaucrat under the administration of Mayor Fiorello H. La

Guardia achieving the rank of director of the Bureau of

Licenses in the Welfare Department. Levin, prior to My Fair

Lady had produced the successful shows of Call Me Mister (1946)

and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1949). Levin’s legal background

would prove to be vital during “tortuous negotiations” with

the estate of Shaw for the rights to Pygmalion. Levin had a

deep appreciation for the arts and admired the

quintessential musical. He believed in contemporary theater

and prior to his decision had been in agreement to produce

Lerner’s attempted musical Lil’Abner, based on Al Capp’s

comic strip. A devoted friend to Lerner, it was with good

9

Juhasz

faith that Levin agreed to make the jump from Lil’Abner, to My

Fair Lady.

With their production team assembled, Lerner, Lowe and

Levin set out to secure designers and cast. Oliver Smith

seemed the obvious choice for scenic designer. An old

friend of Levin, Smith had served as co-producer with him on

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1949) and Bless You All (1950), as well as

having worked with Lerner and Lowe on Brigadoon, (McHugh 21).

Levin believed Smith a good match for My Fair Lady as a result

of his “rare ability to achieve mood, perspective, and

beauty in his painting for the stage,” (Garbian 31). A

former designer for the ballet, Smith sought projects that

would exercise his “economy of space and provoke his powers

of fantasy and poetry,” (Garbian 31). My Fair Lady with its

beautiful scenes of paved side streets, grand Embassy Balls

and panning shots of the Covenant Gardens required just

that.

“Please write me about Pygmalion,” (McHugh 21) Smith

commanded to Levin. The work, still formally unnamed, had

absorbed all of his attentions. Smith’s success with scenic

10

Juhasz

design for musicals included Rosalinda (1942), Billion Dollar Baby

(1945), Brigadoon (1947), High Button Shoes (1947), Gentlemen Prefer

Blondes (1949), Guys and Dolls (1950), and Paint Your Wagon (1951),

(Garbian 33). “Are the rights cleared? I want to start soon

working on ideas. I have some wonderful research here which

will be absolutely terrific…send me a scenic outline so I

can begin to think about Pygmalion soon,” (McHugh 21).

Despite the lack of rights, Levin sent a scenic outline to

Smith and work began.

Lerner described Cecil Beaton as a man whom it was

difficult to discern “whether he designed the Edwardian era

or the Edwardian era designed him,” (Garbian 32). Beaton

proved the ideal choice for costume design due to his

expansive knowledge of history and detail, photography, and

high couture. Beaton possessed an extensive reserve of

celebrity and familial sources of inspiration. A

photographer, he had been afforded the right to meet many

celebrities of high society and concurrently high fashion in

both England and the United States. Beaton also drew great

inspiration for his design from his own childhood. In his

11

Juhasz

designs for Eliza’s many ensembles can be seen the stylistic

choices of his mother and aunt who frequented the Parisian

and English fashion circuits. For Beaton, My Fair Lady

provided the canvas to create the dressings of his preferred

design, (Garbian 33).

As the creative team was assembled, Lerner and Lowe

simultaneously sought out the original cast for their

premiere production. Lerner sold his family stocks in gold

mining for a profit of $150,000 providing him and Lowe with

a travel budget, allowing them to travel throughout England

in search of a star studded cast, (Garbian 37). Rex Harrison

already well renowned for his straight play-acting in such

works as Henry III and Bell Book and Candle was actively sought by

Lerner and Lowe after he was suggested by Nöel Coward, their

original choice for the role, (Sheridan 369). With his

reputation and notoriety, he was their billing star.

Harrison was initially unconvinced to take the role. A

great admirer of Pygmalion and of Shaw’s work, he feared it

would not be done properly. He also feared a role in a

musical. Harrison had never before sung on stage. My Fair

12

Juhasz

Lady would be a debut of sorts for the seasoned performer.

After a lengthy visit in England where Harrison was

performing in Bell Book and Candle, Lerner and Lowe finally

convinced Harrison to join their production. The role would

require no real singing, his parts would be written in speak

sing or the German term “sprechgesang.” If he could match

pitch and act the role he would succeed, Harrison agreed,

(Garbian 37-40).

Their Lady Liza was found in the young Julie Andrews.

Andrews, a professional singer since childhood, had become

Broadway’s newest star in The Boy Friend. “Both show and

ingénue lead were British imports and appealed to Lerner’s

Anglophilism,” (Garbian 35). A mere 19 years of age, she

possessed dazzling gifts, “a charming, crystal clear soprano

voice, immaculate diction, dancing grace, physical

attractiveness and stylish acting,” (Garbian 36). A true

Anglophile, the role of Eliza was a dream for Andrews and

she eagerly signed on. Additionally, Stanley Holloway

accepted the role of Alfred P. Doolittle, his excitement so

immense that he had a custom made set of English working

13

Juhasz

man’s clothes, complete with “sturdy boots,” to get him into

character, (Garbian 39). Robert Coote was selected as

Colonel Pickering, Cathleen Nesbitt as Mrs. Higgins and

Phillipa Bevans as Mrs. Pearce.

In June of 1955, Levin wrote to Laurence “Laurie”

Evans, Rex Harrison’s manager to inform him of the selection

of a director for the production. After seven months of

searching, Levin, Lerner and Lowe had selected Moss Hart as

director. Hart had already been successful as a book

writer, producer, theater owner and stager. Levin described

him as “my personal first choice all along,” and “the best

possible director we could get,” (McHugh 35).

The rest of the creative team included Robert Russell

and Phil Lang, musical arrangements, Trude Rittman, dance

arrangements, Franz Aller, musical director, Gino Smart,

choral arrangements, Hanya Holt, choreography, Abe Feder,

lighting design, Ernest Adler, hair design, Ira Senz, wig

design, Philip Adler, general manager, Harris Danziger,

conductor and Freda Miller, dance pianist.

14

Juhasz

In November of 1955, Chase Bank the now sole

proprietors of the rights of Shaw’s Pygmalion appointed the

most “celebrated literary agent of the time,” Harold

Freeman, to decide the fate of the Pascal estate rights,

(Garbian 37). Lerner and Lowe immediately secured Freedman

himself as their agent and with that secured the rights to

Pygmalion. The next step was financing. Lerner and Lowe

contacted “Robert Sarnoff, the president of NBC, and their

mutual friend, Goddard Lieberson, the president of Columbia

Records, a division of CBS,” (Garbian 41). Lieberson was in

connection with William Paley, the president of CBS,

presenting another potential connection of funding. No deals

were forthcoming though, the duo waited. An additional

peculiarity existed. While Freeman had granted Lerner and

Lowe the rights to Pygmalion, the conditions of the Shaw

estate restricted the rights of the play to be given to only

one person for a period for no longer than five years. This

condition made the enterprise of this musical unappealing

for traditional backers. CBS still remained a viable

investor as a five-year period still represented an

15

Juhasz

effective period of income for the television company. Even

if the show failed to produce income, the television company

would still be granted the rights to broadcast either the

musical or the play of Pygmalion on their network. Levin drew

a deal with CBS in early May of 1955 proposing that CBS

provide his production with $30,000 plus 20% of the overcall

totaling $60,000 in exchange for exclusive rights to

televise the show. Negotiations were made until July 18,

when a final agreement was made. CBS agreed to finance the

entirety of the production, budgeted at $400,000. In

addition to this, Columbia Records presented an offer to

produce the cast album. Neither party would regret their

investment, (Garbian 44).

With opening night of previews approaching, the

unsettled issue of naming the production demanded attention.

Lerner and Lowe had tested many titles but none had felt

right. Promenade, London Bride, Liza, Lady Liza, Fanfaroon and Come to the

Ball had all served as working titles. Eventually the

creative and production team ironically settled upon the

title they all initially liked least, My Fair Lady, (Lerner &

16

Juhasz

Lowe 1956). Lady Liza, despite being the favorite was deemed

an inappropriate representation of the show. The show was

equally about Higgins and the marquee reading “Rex Harrison

in Lady Liza,” would have confused audiences. As a result the

new title was taken from “the last line of ‘London Bridges

Falling Down’ and appears nowhere else in the musical,”

(Hogan 8).

My Fair Lady was given a pre-Broadway try-out at New

Haven’s Shubert Theatre. It premiered on January 4. This

1,600-seat theater located in New Haven, Connecticut

provided a trial run for the show. The theater possessed no

unique challenges for the producers and instead provided

them with a beautiful canvas that had once played host to

The King and I, South Pacific, and Carousel in their trial runs,

(McHugh 170). A full-scale production was mounted and cast

and crew familiarized themselves with the space. Despite

having almost to postpone opening night when Rex Harrison

blockaded himself in his dressing room for fear of musical

performance, the opening performance went off without a

hitch, (Garbian 62). A reporter from Variety attending the

17

Juhasz

performance proclaimed, “The show has so much to recommend

it that only a radical (and highly improbable) slipup in the

simonizing process can keep it out of the solid click

class,” (McHugh 171).

Variety’s review served as a positive omen and carried

them forward with tremendous momentum. Four weeks of

performances at the Erlanger Theatre in Philadelphia began

on February 15, 1956 and performed for sold-out houses each

night.

On March 15, 1956, My Fair Lady made its Broadway debut at

the Mark Hellinger Theater. The theater aesthetically

refined, sported dozens of murals in the style of Boucher

and Watteau, on the subject of the 18th-century French

aristocracy, (William 162-163). It was an ideal location for

the production. One of the largest theaters in the Theater

District, the Mark Hellinger has 1,506 seats and possesses

one of the largest and most well equipped stages in all of

New York. It was a producer, director and actor’s dream.

Home to The Pirates of Penzance, Plain and Fancy, and Ankles Aweigh, My

Fair Lady would become its most notable production.

18

Juhasz

“The reviews were confirmation of an extraordinary hit.

John Chapman proclaimed that ‘Everything about My Fair Lady is

distinctive and distinguished.’ Robert Coleman called it a

glittering musical, ‘as perfect an entertainment as the most

fastidious playgoer could demand.’ Walter Kerr urged: ‘Don’t

bother to finish reading this review now. You’d better sit

right down and send for those tickets to My Fair Lady,’” says

Garbian in his book The Making of My Fair Lady, (Garbian 88).

Irmgard Hutzler, now 81 saw My Fair Lady in its opening

weeks at the Mark Hellinger and recounts the experience as

“one I return to often in my mind.” Hustler, a New York

Native was a member of a union for female clerical workers

at the time and worked for New York Life Insurance Company.

Her group rented the theater for the night as part of their

annual benefit and each lady purchased a ticket to attend.

“If I could go back to one night in my life I would return

to that performance. My Fair Lady was an absolute dream.

Julie Andrews was a gem and Rex Harrison made all the ladies

swoon. The music, the costumes, the lights, it was

19

Juhasz

something I had never experienced before and something I

have never experienced since,” said Hutzler.

My Fair Lady “played to packed houses, with Standing Room

Only at every performance,” (Garbian 91). The theater

accommodated forty standees and for the next three years

ardent theatergoers and devoted fans waited throughout the

night outside the box-office to snag these coveted slots.

The Columbia recorded cast album received incredible

response, selling more than 1,000,000 copies in its first

year of release. Columbia cashed in well on its investment.

My Fair Lady went on to win the New York Drama Critics Circle

Award by unanimous vote and received the most Tony’s ever,

at the time, for a musical in 1957. These included Best

Actor, Best Director, Best Musical, Best Author, Best

Producer, Best Composer, Best Conductor/Musical Director,

Best Scenic Designer and Best Costume Designer, (Garbian

91).

My Fair Lady remained sold out through all performances

of its first two years. A successful American touring

production of the show also occurred during this time. The

20

Juhasz

show performed for a total of six years and nine months on

American soil. It closed on September 29, 1962 after 2,717

performances and set the record at the time for the longest

running musical surpassing Oklahoma’s 2,212 shows, (Garbian

93). The show was adapted into a film version staring Audrey

Hepburn in 1964 that swept the Oscars of all but Best

Actress, which was won by Julie Andrews in Mary Poppins,

(Hogan 8). The show has seen three Broadway revivals in

1976, 1981 and 1993, a successful production at London’s

West End Theater and two revivals at this venue in the years

1958, 1979 and 2001. In addition to this, My Fair Lady has been

performed on tour in the United States (1957 and 2007), the

United Kingdom (2005), as a Broadway Concert (2007) and at

the Châtelet Paris (2013). (My Fair Lady IBDB) A timeless

and enduring work, The Nederlander Organization in

partnership with Roger Berlind known for City of Angels and Kiss

Me Kate and record producer Clive Davis plan to mount a

revival of this classic within the next few years, (Bird, My

Fair Lady: Revival Starring Ralph Fiennes).

21

Juhasz

“I had, at long last written something that I truly

liked and, by glorious coincidence, so did the audience,”

confessed Lerner following My Fair Lady’s thunderous success,

(Garbian 75). Hailed “the perfect musical,” by the New York

Times (Hogan 8), My Fair Lady has enchanted audiences and

critics alike since its conception and has endured as a

classic work over the past nine decades and promises to

remain so for many more.

Works Cited

Alan Jay Lerner & Frederick Lowe. Playback: Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Lowe. Columbia Records, 1956. Web.

Garebian, Keith. The Making of My Fair Lady. Toronto: ECW Press, 1993. Print.

Hogan, Bill. "A Boomer's History of My Fair Lady." AARP Bulletin Oct. 2014: 8. Print.

Holroyd, Michael. Bernard Shaw: The One Volume Definitive Edition. NewYork: Random House, 1998. Print.

Lees, Gene. The Musical Worlds of Lerner and Lowe. London: Bison Books University of Nebraska Press, 1990. Print

McHugh, Dominic. Loverly, The Life and Times of My Fair Lady. New York:Oxford University Press, 2012. Print.

Morley, Sheridan. A Talent to Amuse: A Biography of Noël Coward, p. 369, Doubleday & Company, 1969

22

Juhasz

Morrison, William (1999). Broadway Theatres: History and Architecture (trade paperback). Dover Books on Architecture. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. pp. 162–163

"My Fair Lady: Revival Starring Ralph Fiennes ." New York Theatre Guild. Ed. Alan Bird. New York Theatre Guild, July 2013. Web. 18 Oct. 2014.

"My Fair Lady." IBDB Internet Broadway Database . The Broadway League, 2001. Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

Tomasson, Robert E. "Herman Levin, 83, Producer, Dies; His Hits Included 'My Fair Lady'." New York Times 28 Dec. 1990. Web. 21 Oct. 2014.

Bibliography

Andrews, Julie. Home. New York: Hyperion, 2008. Print.

Block, Geoffrey. Enchanted Evenings. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. Print.

Bordman, Gerald, and Thomas S. Hischak. "My Fair Lady." The Oxford Companion to American Theatre. : Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference. 2004. Date Accessed 22 Oct. 2014

23

Juhasz

Hanson, Laura. "Oliver Smith's SCENIC CHOREOGRAPHY FOR My Fair Lady." TD&T: Theatre Design & Technology 45.1 (2009): 36-45. International Bibliography of Theatre & Dance with Full Text. Fri. 10 Oct. 2014.

Mcnerney, John M. The Ambiguities of Pygmalion. Vol. 29. State College: Penn State University Press, 2009. Penn State University. Web. 22 Oct. 2014.

""MY FAIR LADY" DANCES TO RECORD -- BECOMES LONGEST-RUN BROADWAY MUSICAL." New York Times (1923-Current file): 1. Jul

09 1961. ProQuest. Web. 22 Oct. 2014 .

"My Fair Lady." Theatre Record 32.25/26 (2013): 1359-1361. International Bibliography of Theatre & Dance with Full Text. Fri. 10 Oct. 2014.

"My Fair Lady." . : , 2008-01-01. Oxford Reference. 2009-01-01. Date Accessed 22 Oct. 2014

"My Fair Lady (1956)." Oxford Companion To American Theatre (2004): 449-450. International Bibliography of Theatre & Dance with Full Text. Fri. 10 Oct. 2014.

Newman, Barbara. "Another Opening, Another Show: 'My Fair Lady'." Dancing Times 91.1089 (2001): 823-827. International Bibliography of Theatre & Dance with Full Text. Web. 22 Oct. 2014.

Rice, Charles D. "All the World Loves "My Fair Lady"." New York Herald Tribune (1926-1962): 3. Mar 08 1959. ProQuest. Web. 22 Oct. 2014 .

Semple, Larry. Showtime. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2010. 3348-356. Print.

Steyn, Mark. Broadway Babies Say Goodnight: Musicals Then and Now, Routledge (1999), p. 119

24