Moving forward: Balancing the financial and emotional costs of business failure

Transcript of Moving forward: Balancing the financial and emotional costs of business failure

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2009) 134–148

Moving forward: Balancing the financial and emotionalcosts of business failure☆

Dean A. Shepherd a,⁎, Johan Wiklund b,1, J. Michael Haynie c,2

a Kelley School of Business, Indiana University, 1309 East Tenth Street, Bloomington, IN 47405-1701, United Statesb Jönköping International Business School, P.O. Box 1026, SE-551 11 Jönköping, Sweden

c Department of Entrepreneurship and Emerging Enterprises, Whitman School of Management, Syracuse University, 721 University Avenue,Syracuse, New York, United States

Received 6 March 2007; received in revised form 14 September 2007; accepted 27 October 2007

Abstract

Why do owner-managers delay business failure when it is financially costly to do so? In this paper we acknowledge thatdelaying business failure can be financially costly to the owner-manager and the more costly the delay, the more difficult therecovery. But we complement this financial perspective by introducing the notion of anticipatory grief as a mechanism for reducingthe level of grief triggered by the failure event, which reduces the emotional costs of business failure. We propose that under somecircumstances delaying business failure can help balance the financial and emotional costs of business failure to enhance an owner-manager's overall recovery — some persistence may be beneficial to recovery and promote subsequent entrepreneurial action.Published by Elsevier Inc.

Keywords: Failure; Entrepreneur; Learning; Negative emotions; Commitment; Passion; Recovery

1. Executive summary

A puzzling question has been that of why owner-managers delay business failure when it is financially costly to doso? Business failure occurs when a decline in revenues and/or increase in expenses are of such magnitude that the firmbecomes insolvent, and is unable to attract new debt or equity funding. Consequently, the business cannot continue tooperate under the current ownership and management. Delaying business failure likely diminishes the owner-manager's salvageable personal equity, and may also require additional personal financial investments to delayinsolvency. A dominant explanation for this persistence with a failing business is that these owner-managers' decisionmaking is biased. In other words, these entrepreneurs are wrong. In this paper we offer a possible alternative

☆ The authors would like to thank Ethel Brundin, Venkat, and two anonymous reviewers for providing valuable comments on an earlier version ofthe paper.⁎ Corresponding author. Tel.: +812 856 5220.E-mail addresses: [email protected] (D.A. Shepherd), [email protected] (J. Wiklund), [email protected] (J.M. Haynie).

1 Tel.: +46 36 15 77 00; fax: +46 36 16 10 69.2 Tel.: +315 443 3392.

0883-9026/$ - see front matter. Published by Elsevier Inc.doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2007.10.002

135D.A. Shepherd et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2009) 134–148

explanation, suggesting that some of these owner-managers are operating in their own best interests by delayingbusiness failure.

Specifically, we focus on the owner-managers' recovery from business failure to once again own and manage abusiness. We acknowledge that delaying business failure can be financially costly to the owner-manager and that thegreater these cost, the more difficult the recovery. We complement this financial perspective by introducing the notionof anticipatory grief as a mechanism for reducing the level of grief triggered by the failure event. We suggest that aperiod of anticipatory grief reduces the emotional costs of business failure, and thus may enhance the emotionaldimension of an owner-manager's recovery. By conceiving recovery as negatively related to both the financial andemotional costs of business failure, we propose that under some circumstances delaying business failure can helpbalance the financial and emotional costs of failure to enhance an owner-manager's overall recovery. That is, somepersistence may be beneficial to recovery and promote subsequent entrepreneurial action.

We believe that our anticipatory grief perspective to delaying business failure has a number of important implications.First, research on persistence has focused on the negative financial consequences of delaying the decision to exit from alosing course of action. We complement this research by acknowledging that there are emotional as well as financialconsequences from business failure, that the ability to engage in subsequent entrepreneurial actions depends on emotionalas well as financial recovery, and that the decision to delay business failure may help “balance” financial and emotionalcosts to optimize this recovery. Second, the procrastination and escalation of commitment literatures have focused on theemotional causes but primarily negative financial consequences from persistence. We explore the emotional causes andboth the emotional and financial outcomes from delaying business failure. Third, a recent research has highlighted griefover business failure as an obstacle to learning.We develop the notion of an owner-manager's anticipatory grief that occursbefore business failure and its relationship with the grief that is generated after the business failure event.

2. Introduction

There are few things more dreadful than dealing with a man who knows he is going under, in his own eyes, and inthe eyes of others. Nothing can help that man. What is left of that man flees from what is left of human attention.

–James Baldwin

Only those who dare to fail greatly can ever achieve greatly.

–Robert KennedyBusiness failure occurs when a fall in revenues and/or rise in expenses are of such magnitude that the firmbecomes insolvent and is unable to attract new debt or equity funding; consequently, it cannot continue to operateunder the current ownership and management (Shepherd et al., 2000). Business failure can be delayed by owner-managers, but doing so likely diminishes the owner-manager's salvageable personal equity and may also requireadditional personal financial investments to delay insolvency. For example, as losses mount the owner-managermay need to sell some of the business assets to provide cash (including selling accounts receivable at a lesser value[factoring]) to keep the business solvent. Because bank loans and equity investments are difficult to obtain asbusinesses approach insolvency (Beaulieu 1994, 1996; Sinkey 1992), the owner-manager likely needs to investfurther personal financial resources to delay business failure. Such investments can be characterized as throwinggood money after bad. Yet, despite negative financial outcomes associated with delaying failure, research suggeststhat owner-managers delay the decision to close a poorly performing business such that many underperformingfirms persist over an extended period of time (Gimeno et al., 1997; Karakaya, 2000; McGrath, 1999). To date, thecentral focus of research on persistence has been on owner-managers' decision biases and their resulting negativefinancial consequences (McGrath and Cardon, 1997; Meyer and Zucker, 1989; Van Witteloostuijn, 1998). But areall owner-managers' decisions to delay business failure biased and causing themselves harm, or are there benefitsthat can be generated through this form of persistence?

Owner-managers can be separated from their businesses, such that they may experience a business failure, yetrecover from that failure to be an owner-manager of a subsequent, successful business. Indeed, it is believed that welearn more from our failures than our successes (McGrath, 1999; Sitkin, 1992), and after a business failure, owner-managers have an opportunity to learn from the experience (Shepherd, 2003) to improve the odds of success forsubsequent entrepreneurial actions (Minniti and Bygrave, 2001). Entrepreneurs' subsequent business start-up, so called

136 D.A. Shepherd et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2009) 134–148

serial entrepreneurship, appears to be a common phenomenon (e.g., Ucbasaran et al., 2006) and an importantconsideration for the understanding of entrepreneurship in general (MacMillan, 1986). Some of those who enter intoserial entrepreneurship have experienced failure in their previous entrepreneurial endeavors. When we considerentrepreneurship as more than a one-business-shot for an individual, then the ability of entrepreneurs to recover from abusiness failure provides valuable insights into the likelihood of serial entrepreneurship. This recovery from businessfailure involves the owner-manager's financial resources, which are needed to fund necessary entrepreneurial activities(e.g., starting-up or acquiring a business), and involves grief recovery (Shepherd, 2003), which “frees up” informationprocessing capacity (Mogg et al., 1990; Wells and Matthews, 1994), enhances learning from the experience (Bower,1992), and restores the motivation to try again (Cuisner et al., 1996; Shuchter, 1986).

By acknowledging that entrepreneurship may involve repeated attempts at venture creation, we develop the notionof an owner-manager's anticipatory grief to gain a deeper understanding of the recovery necessary for subsequententrepreneurial action. This opens up the possibility that some delay of business failure may be beneficial; persistencecan help to balance the financial and emotional outcomes of business failure to maximize the recovery of resources(financial and emotional) necessary for subsequent entrepreneurial actions, such as founding another business.

Our framework provides four primary contributions. First, research on persistence has focused on the negativefinancial consequences of delaying the decision to exit from a losing course of action (e.g., Keil et al., 2000; Ross andStaw, 1986, 1993). By recognizing that owner-managers are not limited to one business, we complement these“persistence” studies by acknowledging that there are emotional as well as financial consequences from businessfailure, that the ability to engage in subsequent entrepreneurial actions such as founding another business depends onemotional as well as financial recovery, and that the decision to delay business failure may help “balance” financial andemotional costs to optimize this recovery. That is, some persistence may be beneficial to recovery.

Second, and related to the previous point, the procrastination and escalation of commitment literatures have focusedon the emotional causes and the negative financial effects of persistence. We offer a counter-weight to theseperspectives by investigating emotional causes, emotional outcomes, and the balance of financial and emotional costsin optimizing recovery from business failure.

Third, previous studies have acknowledged heterogeneity in the level of grief generated by the loss of somethingimportant (Bonanno and Keltner, 1997; Prigerson et al., 1996; Wortman and Silver, 1989, 1992) including businessfailure (Shepherd, 2003). In this paper, we develop the notion of an owner-manager's anticipatory grief that occursbefore business failure and its relationship with the grief that is generated after the failure event — the period ofanticipatory grieving offers an explanation, in part, for owner-managers' levels of grief triggered by the business failureevent. Finally, we develop a model of business failure delay that can help explain why individuals are more or lesslikely to make the transition from failure to subsequently owning and managing a business. This is an importantcontribution to the growing literature on serial entrepreneurship.

In the next section, we provide a selective review of the dominant frameworks applied to the decision to persistin the face of a losing course of action. We focus on two theoretical frames (escalation of commitment andprocrastination) that highlight the role of emotions in “biasing” individuals towards persistence and the negativefinancial consequences of that bias. We then introduce the notion of anticipatory grief as a lens through which toconsider why it may be beneficial that some owner-managers persist by delaying business failure. Finally, we offer aconcluding discussion.

3. Delaying business failure: reasons for persistence

3.1. Traditional economic model of persistence

Economic theories applied as descriptive models of firm behavior suggest that the decision of the firms'managers and owners to persist or exit the market is based upon firm performance (Alchian, 1950; Friedman, 1953;Williamson, 1991). For example, Ansic and Pugh (1999) build upon the econometric modeling technique ofKrugman (1989), and employ an expected present value approach to propose that the firm will persist only until thepoint that current losses exceed the present value of expected profits, because the top decision makers aremotivated by financial considerations. Drawn from this perspective are a number of key assumptions relevant to ourdiscussion. First, it is important to note that such theories assume that owner-managers are immediately aware ofthe point in time when the firm becomes failing. Objectively, this assumption is supported by numerous bankruptcy

137D.A. Shepherd et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2009) 134–148

prediction models that provide performance thresholds that once breached, suggest that the business has passed thepoint of no return and business failure is inevitable, or at least highly probable (Altman, 1968; Ohlson, 1980;Zmijewski, 1984). Second, this traditional economic perspective assumes that once owner-managers realize theirbusinesses will fail, they should immediately take action to terminate the business. Immediately terminating afailing business allows the owner-manager to salvage as much personal equity remaining in the business aspossible. Third, this perspective assumes that owner-managers are only motivated by financial considerations. Thisleads to the following, rather obvious, proposition:

Proposition 1. The longer owner-managers persist by delaying business failure, the greater their financial costsarising from its failure.

The resources of owner-managers are closely intertwined with those of their businesses. First, for many owner-managers much of their personal resources are invested in their businesses and therefore much of their personalwealth is tied to the value of that business (Brophy and Shulman, 1992). Second, although in theory a companyrepresents a separate legal entity providing limited liability for owner-managers, in practice banks and other lendinginstitutions often require personal guarantees from owner-managers before providing smaller and/or newerbusinesses debt capital. In such a case personal collateral is equivalent to the entrepreneur investing their ownequity in the business because they are placing their personal funds at risk (Thorne 1989), and also being exposed topersonal losses if the business fails. Third, equity investors are highly influenced by the knowledge of the owner-manager and often turn to an entrepreneur's track record for information to make such determinations (MacMillanet al., 1985) as well as the entrepreneur's level of “personal” equity in the business (Prasad et al., 2000; Yoshikawaet al., 2004). The owner-manager's level of personal equity in the business is believed to signal the quality of thebusiness to investors (especially if this personal equity represents a substantial portion of the owner-manager'spersonal wealth) (Prasad et al., 2000) and reassure investors that the owner-manager will exert maximal effort toachieve business success.

Business failure, as defined here, typically means that the residual value of the business is low or negative. Givenowner-managers personal wealth is closely intertwined with the value of the business, business failure indicatesdiminished personal wealth. This is all the more likely for those who made personal guarantees for the business' bankloans and when their business is in a negative net asset position. Although it is reported that some venture capitalistsview business failure as a badge of honor (Landier, 2004), most investors view it as a blight on a entrepreneur's trackrecord making it more difficult and/or more costly to acquire equity and debt capital (Lee et al., 2007). During andimmediately after business failure, many of these owner-managers will have a substantially reduced income (perhapsrelying solely on unemployment benefits). Over time, entrepreneurs can re-build their personal wealth, re-establishlegitimacy with equity investors, and re-build collateral for bank loans, such that they can once again found or acquire abusiness. Although there is likely heterogeneity in an owner-manager's financial costs from business failure (an issuewe address below leading to Proposition 5), we propose the following:

Proposition 2. The higher owner-managers' financial costs after business failure, the longer the time interval betweenthe failed business and action to own and manage a subsequent business.

Given these assumptions— necessary and appropriate given the notion of rationality central to economics— evenprominent economists acknowledge their limitations when applied to practice. For example, Krugman himself (1989:55–57) stated that “such calculations are…no substitute for real evidence on what firms actually do…”.3 Empiricalevidence does suggest that at least some owner-managers decide to persist despite poor performance by delayingbusiness failure (e.g., Gimeno et al., 1997). In the next section we briefly review the escalation of commitment andprocrastination literatures as possible explanations for persistence. We then develop the notion of anticipatory grief tooffer an alternate explanation— one where some persistence can enhance an owner-manager's recovery from businessfailure.

3 Deviations from strict rationality in organizational decision making are well established in the literature (e.g., Cyert and March, 1963). Wesuggest that the theories that we cover represent the dominant frameworks specifically applied to the decision to persist in the face of a losing courseof action.

138 D.A. Shepherd et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2009) 134–148

4. Explanations for why owner-managers delay business failure

4.1. Escalation of commitment and persistence

The escalation of commitment framework offers a possible explanation for why owner-managers may delay businessfailure and persist with an underperforming business. Escalation of commitment refers to an increasing commitment tothe same course of action in a sequence of decisions resulting in negative outcomes (Karlsson et al., 2005a, b: 835;Staw et al., 1997). Our review of the escalation of commitment literature (see also Karlsson et al., 2005a, b) generallysuggests three explanations for this behavior.

First, individuals persist with a losing course of action to satisfy a need to justify previous decisions to self andothers (cf. Brockner, 1992). Owner-managers are often confident that their businesses will be successful (Cooper et al.,1988) and this confidence likely influences their strategic decisions and their relationship with others includingresource providers (Hayward et al., 2006). Business failure may repudiate these decisions and indicate hubris, soowner-managers may escalate commitment to justify (to oneself and/or to others) that their initial decisions and actionswere accurate.

Second, escalation of commitment might occur as a result of an overgeneralization of a “don't waste” decision rule(cf. Arkes and Blumer, 1985). That is, individuals continue an endeavor once they have made an investment of money,time and/or energy because to terminate that course of action would appear wasteful and people have a desire not toappear wasteful (Arkes and Blumer, 1985). This influence of sunk costs on future investments is well documented (Keilet al., 2000). Owner-managers who found new businesses typically invest considerable personal resources, time andenergy into the business and therefore, it is not be surprising that owner-managers appear to be reluctant to terminatetheir businesses under concerns that they might be perceived as having wasted these initial resources (Caves and Porter,1976; Dean et al., 1997; Rosenbaum and Lamort, 1992).

Third, individuals may frame the persistence decision in terms of a sure loss (terminating the course of action now)or as an uncertain loss (delaying the decision to terminate the course of action) preferring the uncertain loss despite theknowledge that the uncertain loss is likely to be substantially higher than the certain loss (Garland and Newport, 1991).This explanation of escalation of commitment is consistent with Prospect Theory's (Tversky and Kahneman, 1981)notion that in loss situations people are risk seeking and in gain situations they are risk averse. Therefore, using thispossible explanation, owner-managers facing a certain loss (as associated with immediate business closure) are morelikely to choose to delay business failure by investing further personal resources into the business despite the likelihoodthat the total financial losses will be greater.

There has been some debate as to whether escalation is restricted to situations when there is uncertainty surroundingthe outcomes of the continued course of action, or if escalation also occurs when it is possible to estimate the futurereturns to investments (Garland et al., 1990; Heath, 1995; Karlsson et al., 2005a, b). For example, recently, Karlssonet al., (2005a, b) found empirically that although there may be no uncertainty in terms of future outcomes— and peopleknow that they will be economically worse off by continuing to invest — they continue to do so. In another studyfocused on new product development, Schmidt and Calantone (2002) demonstrate that managers responsible forinitiating a given project feel a stronger ownership to the project than managers who take over the project at somelater date; those founding the project were more committed to the project, likely to accelerate its development, andcontinue to fund the project than non-founding managers (Schmidt and Calantone, 2002). This suggests that for owner-managers, despite knowing that their businesses will fail and that delaying business failure through further personalinvestments in the business will result in greater financial losses, they may still persist with the business. A review ofthese empirical findings led Karlsson et al., (2005a, b: 67) to conclude that: “a more comprehensive understanding ofescalation requires disentangling people's non-economic reasons for escalation”. Procrastination offers an emotion-based explanation for delaying business failure, to which we now turn.

4.2. Procrastination and persistence

Procrastination refers to the postponement of a behavior that is experienced as emotionally unattractive, butcognitively important because it will lead to positive outcomes in the future (cf. Van Eerde, 2000). Procrastinationoccurs when this emotional threat is dealt with by an avoidance response, which results in postponement of the action(Lazarus and Folkman, 1984); the anticipation of the threat elicits negative emotions such as anxiety, and by escaping

139D.A. Shepherd et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2009) 134–148

from the situation this anxiety is reduced, which represents a negative reinforcement that helps sustain the pattern ofbehavior (Anderson, 2003; Milgram et al., 1998: 299). Procrastination appears to be particularly relevant in theentrepreneurial context. Owner-managers may procrastinate because it postpones the decision and actions of declaringthe business insolvent and forgoing ownership or management in the business. While an emotionally dauntingundertaking, it is a cognitively important task because the financial costs of business failure will be lower if additionalpersonal investments are not made by the owner-manager to delay business failure. Further, the literature suggests thatthe greater the anticipated negative emotions of a task, the greater the likelihood of procrastination (Anderson, 2003).Several factors influence the anticipation of negative emotions, and thus the chances of procrastination. First,irreversible decisions generate more negative emotions (Anderson, 2003). Although it is possible for owner-managersto start additional businesses, the decision to close a specific business is irreversible. Second, decision makers are alsolikely to anticipate more negative feelings when they perceive themselves as being personally responsible for theoutcome. Owner-managers often view their business as an extension of themselves and their personalities (Bruno et al.,1992; Cova and Svanfeldt, 1993) and are therefore likely to also consider themselves as personally responsible for theoutcome of the business. Finally, greater negative emotions are generated when one's own decisions “cause” the onsetof the negative outcome rather than when others make that decision. This could influence owner-managers to delaybusiness failure. Taken together, there are several characteristics of the decision and actions of declaring the businessinsolvent that are likely to elicit procrastination.

In sum, theories of escalation of commitment and procrastination selectively reviewed above provide valuableinsights into the cognitive (primarily escalation of commitment) and emotional (primarily procrastination) biases thatencourage persistence. While the negative financial consequences from persistence are clear (Garland et al., 1990; Rossand Staw 1986, 1993), the emotional consequences of persistence remain relatively under-explored. For example, in areview of the literature, Anderson (2003: 142) concluded that: “it is interesting to note that the vast majority of[procrastination] studies support the conclusion that emotional goals influence decision avoidance but that post-decisional emotions are infrequently measured … It is reasonable to assume that people make choices that reducenegative emotions”. It is this emotional consequence — in the context of the owner-manager's decision to persist bydelaying business failure — that we now consider. Specifically, we turn to the anticipatory grief literature to establishan emotional link between the period before the business failure event and the period after the business failure event, tosuggest possible benefits to owner-managers from delaying business failure.

5. Anticipatory grieving and emotional recovery: an additional explanation for why owner-managers delaybusiness failure

Psychological research on bereavement has demonstrated that the level of grief over the death of a loved onedepends on the period of emotional processing in anticipation of the upcoming death.4 That is, the extent to whichindividuals experience anticipatory grief (before the loss event) will influence the level of grief (after the loss actuallyoccurs), and importantly its corresponding emotional and psychological outcomes (Lindemann, 1944; Parkes andWeiss, 1983; Rando, 1986). This concept of anticipatory grief has been extended beyond the loss of a loved one toinclude a range of losses such as those associated with cardiac surgery (Christopherson, 1976), amputation (Wilson,1977), and divorce (Roach and Kitson, 1989). We develop this notion of anticipatory grief to offer an alternateexplanation for the decision to delay business failure and persist with a failing business.

The notion of an owner-manager's anticipatory grief describes a phenomenon encompassing the process ofmourning, coping, interaction, planning, and psycho-social reorganization that are stimulated and begun in part inresponse to the awareness of the impending failure of a business and the recognition of associated losses in the past,present, and future (adapted from Rando, 1986). Research suggests that a period of anticipation leading up to animpending loss is valuable because it allows the individual to emotionally prepare for the loss (Parkes and Weiss,1983), by gradually withdrawing emotional energy from the object (loved one or business) being lost. This processserves as an emotional safeguard when the loss actually occurs (Lindemann, 1944), allowing the individual to makesense of the loss because it will be seen as part of a predicted process (Parkes and Weiss, 1983). In the end, anticipatorygrieving likely facilitates an owner-manager's process of emotionally coping with business failure, by better preparingthe owner-manager to learn from the experience and reinvest their emotions elsewhere.

4 Grief refers to the negative emotional reaction to the loss of something important (Archer, 1999).

140 D.A. Shepherd et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2009) 134–148

This benefit, however, may come at a cost. While anticipatory grief may ease the transition from owner and managerof a business to no longer having these roles, the process leading up to business failure may be arduous and emotionallydraining. Research suggests that given anticipatory grieving, there appears to be mutually conflicting demands ofsimultaneously holding onto, letting go of, and drawing closer to the object being lost (dying loved one or failingbusiness) (Rando, 1986). For example, following the realization that a loved one's illness is terminal, individuals beginto emotionally distance themselves in order to prepare for the imminent death. But they will also become moreinvolved with the terminally ill loved one to maintain communication and interaction, to finish unfinished business,and resolve past conflicts and to say goodbye (for a review see Rothaupt and Becker, 2007). Similarly, on the one hand,owner-managers may begin to emotionally distance themselves from the business in order to prepare for businessfailure, e.g., begin to separate their individual identities from those of their businesses by emphasizing membership inother groups (Major and Schmader, 1998; Major et al., 1998). But on the other hand, the owner-manager becomes moreinvolved with the failing business attempting to resolve remaining issues and “put out the many fires” that ignite as abusiness approaches insolvency. “A critically important task in anticipatory grief is to balance these incompatibledemands and cope with the stress their incongruence generates … It is no wonder that many grievers feel somewhatimmobilized. They are subject to such conflicting pulls all occurring at once, that they can get stuck in the middle justlike anyone else who is being pulled in contradictory directions” (Rando, 1986).

In terms of this balance, Rando (1983) and Sanders (1982) found that there was an optimal period of time ofanticipatory grieving which minimized the subsequent grief triggered by the loss event and maximized adjustment.Periods of anticipatory grieving that were particularly short or particularly long were more likely to result in higherlevels of grief than for periods of anticipatory grieving of moderate length. For example, among parents whose childrenhad died of cancer, those having children experiencing a medium period of illness (6 to 18 months) were betterprepared for the death and adjusted better than parents whose children's illness was shorter than 6 months or longerthan 18 months (Rando, 1986). It appears that while long periods of illness allow for greater emotional preparation(Parkes and Weiss, 1983), the emotional reserves (ability to cope with grief triggered by the death) are diminished.Although the actual number of days or months that represent an optimal period for anticipatory grieving is an empiricalquestion that likely varies across parents of children dying of cancer and owner-managers whose businesses are failing,this notion of an optimal period of anticipatory grieving may provide important insights into the emotional antecedentsand outcomes of persisting by delaying business failure.

Owner-managers are often aware that their business will fail before the event actually takes place.5 Indeed,insolvency prediction models offer performance thresholds that when breached indicate that the business has passed thepoint of no return and business failure is inevitable (or highly probable) (Altman, 1968; Ohlson, 1980; Zmijewski,1984). These are similar to the models used by banks and other lending institutions to determine whether or not toprovide a business debt capital. Awareness that the business will fail also involves the realization that there will be no“white knight” to rescue the company with a cash infusion. We suggest that this awareness can cause anticipatory grief(cf., Lindemann, 1944; Rando, 1986), and is stimulated by losses that have already occurred, those that are currentlyoccurring, as well as those that are to come (Rando, 1986). For example, in managing the company during this troubledtime, the owner-manager may grieve over the vibrant and healthy organization slipping into decline in the face of a“hostile” environment. He or she grieves for the changes in lifestyle that are imminent, and for the dreams of a business'future that will never be realized. This is a grief over what is being lost right now. He or she is also likely to grieve overthe absence of the business in the future.

Rando (1986) suggested that although the true reality of the absence cannot completely be realized until the deathhas occurred, it is possible to obtain a small, but important indication of what this will be like through extrapolation ofpresent experiences that foreshadow the permanent absence in the future. In the case of entrepreneurship, persistingwith a failing business provides an opportunity for the owner-manager to witness, and thus come to grips with, theprogressive debilitation of the business over which he or she is likely to have little control; this period of delay providestime for the owner-manager to prepare for the business' inevitable failure.

We are suggesting that to persist in the face of an impending business failure is not necessarily a function of theextent to which the owner-manager believes that “I can fix this” and recover the business. Despite a grim outlook, some

5 This may not always be the case. A natural or man-made disaster may terminate a business with no prior warning for the entrepreneur. In such acase the period of anticipatory grieving is very small or non-existent.

141D.A. Shepherd et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2009) 134–148

owner-managers may be able to turn their businesses around, just as some individuals recover from seeminglyincurable cancer. Instead, we are suggesting that among owner-managers that eventually do fail, those who engage in agrieving process anticipating the business failure will be emotionally better prepared for it. Being forewarned of theupcoming loss is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for anticipatory grief. For example, an accountant mightpoint out to the owner-manager that the business is rapidly heading towards insolvency and that all potential sources ofcash infusion have been exhausted. However, the owner-manager may be in a state of denial or simply avoids thinkingabout the inevitable event (Kübler-Ross, 1969).6 Anticipatory grief requires some “grief work” to emotionally preparefor business failure. The notion of “grief work” refers to working through and processing some aspect of the lossexperience (Bonanno and Keltner, 1997; Prigerson et al., 1996; Wortman and Silver, 1989, 1992). This does not meanthat the owner-manager must continuously focus on his or her anticipatory grief and forthcoming loss. Indeed, itappears that processing a loss is enhanced when periods of grief work are interspersed with periods of avoidingthinking about the business and proactively addressing secondary causes of stress triggered by the firm's poorperformance (Shepherd, 2003). However, an extended period of anticipatory grieving can be emotionally exhaustingexacerbating grief over business failure when the failure event eventually occurs.

Therefore, we would expect that with a quick failure process (a short period from failure awareness to the failureevent), the emotional preparation gained though anticipatory grieving would be insufficient for the owner-manager,which could lead to higher levels of grief after the business failure event. For example, if a large and powerfulcompetitor appears without warning and puts an abrupt end to a business, the owner-manager is likely to have a veryshort period of anticipatory grieving, providing little time for emotional preparation and therefore the owner-manager islikely to experience substantial grief over the business' failure. If the failure process is substantially extended, as maybe the case in the face of changing consumer preferences that slowly reduce a firm's market share, this extended periodof anticipatory grieving could lead the owner-manager to become emotionally drained, which increases the level ofgrief once the failure event occurs.

Therefore, we suggest that as long as the owner-manager anticipates that his or her business will fail, then they willlikely experience, and begin to process, anticipatory grief. Some will experience greater anticipatory grief, and somewill be more effective at processing it; but over and above these individual differences, the period of anticipatory griefappears to have a curvilinear relationship with emotional recovery from business failure. Thus,

Proposition 3. There is a curvilinear relationship between the period of anticipatory grieving and the owner-manager's grief triggered by the business failure event; the owner-manager's level of grief triggered by the failure eventdecreases with persistence to a critical point but beyond this critical point further persistence increases the level ofgrief triggered by business failure.

Research shows that some owner-managers are able to move on from a business failure and develop strongintentions to start subsequent businesses (Schutjens and Stam, 2006) and that many owner-managers (47%) indeed starta new business after going bankrupt (Small Business Administration, 1994). Business failure provides owner-managersan opportunity to learn from the experience. Furthermore, it appears that entrepreneurial learning is mainly experientialin nature (Corbett, 2005; Politis, 2005) providing serial owner-managers enhanced expertise in running a business(Wright et al., 1997) and providing benchmarks for judging the relevance of information (Cooper et al., 1995). Thislearning can lead to an understanding of the “real” value of new entrepreneurial opportunities, speed up the businesscreation process, and enhance performance (Davidsson and Honig, 2003).

Further, the experience of failure itself may lead to the possibility of gaining unique knowledge that can not belearned from successful entrepreneurship only (McGrath, 1999; Rerup, 2005). First, there is likely a direct relationshipbetween the opportunities that lead to failure and the possibility for owner-managers to learn. All else equal,opportunities that deviate more from what already exists (exploiting a new technology vs. starting a new McDonald'soutlet) are riskier and have higher chances of failure, but these risky opportunities are also those that are more closelyrelated to learning (March, 1991). Second, the experience of business failure likely makes owner-managers morethoughtful (Rerup, 2005). It leads them to start thinking along new patterns and search more openly for new ideas and

6 Again there are parallels here with the death of a loved one. The doctors may point out that death is approaching and that they have doneeverything that is possible. Some individuals will acknowledge this information and begin anticipatory grieving, while others may enter a state ofdenial and hold out the possibility of a “miracle”. This is a particularly salient decision for those faced with the decision of whether or not to removea loved one from a life-support system (see Werth, 2005; Wiegand, 2006).

142 D.A. Shepherd et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2009) 134–148

opportunities. Given this unique knowledge and expertise gained through previous entrepreneurial experience andfailure, owner-managers who have learned from business failure are in a unique position to start a successful newbusiness.

Although negative emotions such as those that constitute grief can highlight the importance of an event for furtherscanning (Luce et al., 1997; Pieters and van Raaij, 1988; Schwarz and Clore, 1988), negative emotions can alsoconsume information processing capacity making it difficult to learn from the experience (Mogg et al., 1990; Wells andMatthews, 1994) and difficult to make subsequent emotional investments (Cuisner et al., 1996; Shuchter, 1986). Weuse the term emotional costs of business failure to refer to the negative role of grief on an owner-manager's ability tolearn from the experience and move on to other entrepreneurial actions, such as founding or acquiring another business.Similarly, symptoms of grief, such as despair, disorganization and anger (Hogan et al., 2001) likely make it difficult forowner-managers to focus energy and emotion on a new business. Thus,

Proposition 4. The greater the emotional costs of a business failure, the longer it will take for the owner-manager toemotionally recover from business failure to own and manage a subsequent business.

6. Delaying business failure to balance the financial and emotional costs of failure

Our anticipatory grief explanation for delaying business failure to persist with a business introduces the need to“balance” the owner-manager's financial and emotional costs to optimize his or her recovery. This “balance” likelyvaries across individuals and across business failures within individuals. Earlier we made the case that owner-managers' personal wealth is likely substantially diminished by the failure of their businesses. However, some owner-managers may have much of their personal wealth insulated from business failure. For example, they may have adiversified personal investment portfolio, have not offered personal guarantees for business loans, and/or businessfailure is a badge of honor by venture capitalists in this particular industry. This lowers the financial cost of businessfailure if it were to occur without any delay. However, regardless of the initial (without delay) financial cost of businessfailure there is likely heterogeneity in the rate at which financial costs are accumulated with increasing delay ofbusiness failure. That is, the financial cost of delay is likely greater for some owner-managers and their businesses thanothers. For example, for those businesses that have a higher burn rate, greater financial investments are required todelay business failure and in some industries assets depreciate at a faster rate meaning that the owner-manager'sresidual claim on the business is decreasing at a faster rate.

We have also made the case that grief interferes with recovery and that owner-managers feel grief after businessfailure. However there is likely heterogeneity in owner-managers' level of grief over business failure. First, grief isgreater over the loss of objects for which the individual has made sustained emotional “investments” (Jacobs et al.,2000; Robinson et al., 1999). Therefore, consistent with the endowment effect (Loewenstein and Issacharoff, 1994;Van Dijk and van Knippenberg, 1996), owner-managers' grief is likely greater over the failure of businesses that havebeen owned and managed longer. Second, recent, multiple losses can result in an accumulation of grief (Nord, 1996).As such, a business failure that occurs after a series of business failures will likely lead to higher levels of grief. Third,the more importance attached by an individual to the object lost, the greater the level of grief (Archer, 1999). Forexample, when the business forms a central role in the formation of the owner-manager's identity, then its failure is

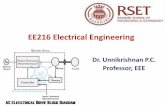

Fig. 1. Balancing the financial and emotional costs of business failure to optimize recovery.

143D.A. Shepherd et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2009) 134–148

likely to generate high levels of grief (Belk, 1988). Therefore, some owner-managers may experience substantial griefwhile others little grief over business failure.

Although we have proposed above that some delay in business failure can decrease the level of grief triggered bybusiness failure, there is likely variance in the extent to which owner-managers use this period of delay for anticipatorygrieving and also variability in the effectiveness of their anticipatory grieving. Some owner-managers may delaybusiness failure for reasons explained by the escalation of commitment or procrastination literatures and are in denialover the impending business failure — there is little to no anticipatory grieving. Some may use the delay foranticipatory grieving but are not good at it. For example, Shepherd (2003) proposed that grief recovery over businessfailure is enhanced when the individual oscillates between a loss — confronting the loss, revisiting the events beforeand at the time of the death, and “working through” some aspect of the loss experience (Shepherd, 2003; Stroebe andSchut, 1999). — and a restoration orientation — distracting oneself from thoughts related to the loss and focusing onaddressing secondary causes of stress (Archer, 1999; Shepherd, 2003; Stroebe and Schut, 1999). There is likelyvariability in the extent to which individuals oscillate between these two orientations while dealing with anticipatorygrief. Thus,

Proposition 5. Some persistence can enhance an owner-manager's overall recovery from business failure when thereis a strong relationship between persistence and emotional costs relative to the relationship between persistence andfinancial costs.

Our model with its five propositions is depicted in Fig. 1. The model suggests that longer persistence increasesfinancial costs (P1), and that financial cost has a negative effect on overall recovery (P2). The relationship betweenpersistence and emotional cost has a U-shape so that emotional cost is minimized with a period of medium persistence(P3) and that emotional cost has a negative impact on overall recovery (P4). Finally, if emotional cost dominates overfinancial cost, the relationship between persistence and overall recovery will be U-shaped (P5).

7. Discussion

Why owner-managers delay business failure when it is financially costly to do so? The dominant explanation inthe literature is simply that the decision to delay business failure is biased — these entrepreneurs are wrong. Weoffer a different explanation, or at least offer the possibility that some of these owner-managers are operating intheir own best interests. Specifically, we focused on the owner-managers' recovery from business failure to onceagain own and manage a business, thus engaging in serial entrepreneurship. We acknowledged that business failureis likely to be financially costly to the owner-manager, and the greater the financial costs the more difficult thefinancial recovery. However, we complemented this financial perspective by highlighting the role of negativeemotions surrounding business failure and the importance of emotional recovery. Owner-managers are likely toexperience grief over business failure, which retards recovery. Developing the notion of anticipatory grief, weproposed that some period of anticipatory grief provided by delaying business failure could minimize the level ofgrief triggered by the failure event. Considering recovery as a (negative) function of both financial and emotionalcosts born by business failure, our anticipatory grief model provides a possible explanation for delaying businessfailure — an explanation based on balancing the financial and emotional costs of business failure to optimizerecovery. We believe that our anticipatory grief perspective to delaying business failure has a number ofimplications for scholars.

First, our model offers a counter-weight to the economic and escalation literatures that explain persistence in termsof biases and decision errors. We suggest that in some cases (for some owner-managers and/or for some businessfailures) some persistence before business failure can be beneficial to the owner-manager. This potentially opens upnew ground for research on escalation of commitment. For example, it suggests the possibility of extending the scopeof these studies beyond the boundaries of a single project. Perhaps what appears to be a bias for one project might bebeneficial to the decision maker across a series or portfolio of projects. Moving beyond a single project highlights theneed to consider dependent variables other than simply the financial costs of persistence. Here we have highlighted theimportance of the emotional costs of business failure and subsequent emotional investments.

Second, while the procrastination literature acknowledges emotion as a possible cause of persistence, by definitionthis persistence is to the long-run detriment of the individual. We offer the possibility that by acknowledging the role ofemotion and its processing (anticipatory grief and grief) persistence may provide some long-run benefit (rather than

144 D.A. Shepherd et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2009) 134–148

detriment) to the individual. Therefore, while some owner-managers' persistence might be accurately described asprocrastination in other cases this might be an inappropriate classification and more appropriately explained by ouranticipatory grief perspective. That is, delaying business failure might better balance the financial and emotional costsof business failure to optimize recovery. To distinguish between procrastination and anticipatory grief as an appropriateexplanation for persistence requires the consideration of emotional outcomes as well as emotional inputs. By doing soin this paper, we have taken a small step towards addressing Anderson (2003) observation that there is a dearth ofresearch on the role of people's desire to reduce negative emotions.

Third, it is not surprising that business scholars have focused on the financial aspects of delaying business failure, orthat scholars of bereavement and grief have focused on the emotional aspects of the delayed death of a terminally illloved one. We have stressed the importance of considering both the financial and the emotional in understandingrecovery from business failure. Although anticipatory grief and grief have been extended to important losses other thanof a loved one (Christopherson, 1976; Roach and Kitson, 1989; Wilson, 1977), the focus has still been on emotionaloutcomes. With great caution we take some small steps to suggest that perhaps there is a financial component to someof these situations. For example, how do people make their decision to delay divorce? Does such a decision impact theirfinancial and emotional recovery from divorce? It appears that some people grieve in anticipation of a divorce (Roachand Kitson, 1989). Perhaps there are some benefits to persisting for a period in a “bad” marriage before divorcing toallow for emotional preparation for the event. There is much work to be done in exploring the financial and emotionalcosts of losing something important.

Fourth, our model complements existing work on grief over business failure. Shepherd (2003) model begins withthe business failure event and the subsequent triggering of a negative emotional reaction. We introduce the notion ofgrief that occurs in anticipation of business failure and how this anticipatory grief influences the level of grief triggeredby the business failure event. Furthermore, Shepherd (2003) focused on enhancing the grief recovery process so thatentrepreneurs could maximize their learning from the experience. We focus on the period of anticipatory grieving thatbalances the financial and emotional costs of failure to optimize a more general form of recovery.

Finally, in recent years there has been increased interest in the emotional bonds between entrepreneurs and theirbusinesses. There is research to suggest that entrepreneurs make sustained emotional “investments” in their businesses(Cardon et al., 2005) and that their businesses form central roles in the formation of entrepreneurs' identities (Downing,2005). The work of Cardon and her co-authors (2005), for example, appear to reflect (or have stimulated) a resurgentinterest in entrepreneurial passion. In our research, we examine the flip-side of passion, i.e., grief. We hope that futureresearch attempts to explore multiple emotions— particularly negative (such as a grief) and positive (such as passion)—throughout the entrepreneurial process including start-up, failure and re-start.

There is considerable scope for future theoretical and empirical research, and this research could extend our currentboundary conditions and challenge current implicit assumptions. For example, we assume an additive (main effect)relationship between the financial and emotional costs of business failure in determining total costs and in contributingto recovery. But perhaps the relationship between business failure and emotional costs (and eventually total costs)depends on the level of financial costs from business failure. It could be that more financially costly business failuresexacerbate the level of grief from the event, magnify or diminish the “weight” given to emotional costs in determiningtotal costs, and/or slow the grief recovery process (controlling for the initial level of grief). There are a lot of interestingpossibilities in exploring the relationship between the financial and emotional costs of business failure in optimizingrecovery. We believe that proposing an additive (main effect) relationship is an appropriate first step — one thataccommodates a positive correlation between financial and emotional costs but leaves open the possibility of amultiplicative relationship.

Future research can also investigate which people are likely to best utilize the period before business failure to grievein anticipation of the event to reduce the emotional costs of business failure. Explanations for these individualdifferences might include coping self efficacy (Benight and Bandura, 2003; Benight et al., 2001), prior experienceswith business failure and/or other important losses, and emotional intelligence (Goleman, 1995; Huy, 1999; Ramoset al., 2007; Salovey and Mayer, 1990). For example, it is likely that emotionally intelligent owner-managers recognizetheir negative emotions arising from the failing business as anticipatory grief, are better able to regulate these emotions,and perhaps more effectively process anticipatory grief such that they require a shorter delay of business failureto optimize recovery. Investigations of individual differences in anticipatory grief and grief, such as emotionalintelligence and other learned abilities, will likely make important contributions to our understanding of owner-managers' recovery from business failure.

145D.A. Shepherd et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2009) 134–148

Central to empirical research is being able to measure anticipatory grief, the period of business failure delay, grief,and recovery. There are existing measures of anticipatory grief (Butler et al., 2005; Mystakidou et al., 2005) and grief(Hogan et al., 2001; Prigerson et al., 1997) primarily from the “death of a loved one” literature that could be adapted tothe business failure context. The period of business failure delay could be measured as the number of days after thebusiness reaches a threshold specified by bankruptcy prediction models. Financial recovery can be measured in termsof money, assets, and access to capital (relative to some benchmark such as the level before the business startedperforming poorly or at the time of first becoming an owner-manager), emotional recovery in terms of the absence ofgrief (using the grief measure), and overall recovery in terms of whether the individual again becomes an owner-manager. Not to indicate that these are easy tasks, but the greatest challenge likely lies in the design to collect data. Forexample, it might be difficult to find owner-managers of failing businesses, to secure their involvement in the study,and maintain their involvement over an extended period during a difficult time in their life and asking them to disclosevery personal information. An alternative to a field study is an experiment, although it also has its challenges. Forexample, it might be difficult to generate the emotions of a real-life business situation— the emotional investment, theanticipatory grief, the grief and the engagement of a grief recovery process. The flip-side of these difficulties is the veryreal opportunity of making an important contribution to the literature and perhaps to entrepreneurs attempting torecover from business failure.

8. Conclusion

In this paper we proposed that emotions are more than simply a factor that bias owner-managers such that they delaybusiness failure to their own peril. Emotions occur before and after the failure event and impact the emotional recoveryof an owner-manager. That is, a period of grieving that anticipates business failure can decrease the level of grieftriggered by the failure event and thus enhance emotional recovery. Recovery is a function (negative) of both thefinancial and emotional costs of business failure. Therefore, we propose that in some situations persistence by delayingbusiness failure can balance the financial and emotional costs of business failure to optimize recovery.

References

Alchian, A., 1950. Uncertainty, evolution and economic theory. Journal of Political Economy 58 (3), 211–221.Altman, E., 1968. Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. Journal of Finance 589–609.Anderson, M.C., 2003. Rethinking interference theory: executive control and the mechanisms of forgetting. Journal of Memory and Language 49,

415–445.Ansic, D., Pugh, G., 1999. An experimental test of trade hysteresis: market exit and entry decisions in the presence of sunk losses and exchange rate

uncertainty. Applied Economics 31, 427–436.Archer, J., 1999. The Nature of Grief: The Evolution and Psychology of Reactions to Loss. Routledge, London and New York.Arkes, H.R., Blumer, C., 1985. The psychology of sunk loss. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 35, 124–140.Beaulieu, P.R., 1994. Commercial lenders' use of accounting information in interaction with source credibility. Contemporary Accounting Research

10, 557–585.Beaulieu, P.R., 1996. A note on the role of memory in commercial loan officers' use of accounting and character information. Accounting.

Organizations and Society 21 (6), 515–528.Belk, R.W., 1988. Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research 15, 139–168.Benight, C.C., Bandura, A., 2003. Social cognitive theory of traumatic recovery: the role of perceived self-efficacy. Behaviour Research and Therapy

42, 1129–1148.Benight, C., Flores, J., Tashiro, T., 2001. Bereavement coping self-efficacy in cancer widows. Death Studies 25 (2), 97–125.Bonanno, G.A., Keltner, D., 1997. Facial expression of emotion and the course of conjugal bereavement. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 106, 126–137.Bower, G.H., 1992. How might emotions affect learning? In: Christianson, S. (Ed.), The Handbook of Emotion and Memory: Research and Theory.

Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, England, pp. 3–31.Brockner, J., 1992. The escalation of commitment to a failing course of action: toward theoretical progress. Academy of Management Review 17 (1),

39–61.Brophy, D.J., Shulman, J.M., 1992. A finance perspective on entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 16, 61–71.Bruno, A.V., McQuarrie, E.F., Torgrimson, C.G., 1992. The evolution of new technology ventures over 20 years: patterns of failure, merger, and

survival. Journal of Business Venturing 7, 291–302.Butler, L.D., Field, N.P., Busch, A.L., Seplaki, J.E., Hastings, T.A., Spiegel, D., 2005. Anticipating loss and other temporal stressors predict traumatic

stress symptoms among partners of metastatic/recurrent breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 14 (6), 492–502.Cardon, M.S., Zietsma, C., Saparito, P., Matherne, B.P., Davis, C., 2005. A tale of passion: new insights into entrepreneurship from a parenthood

metaphor. Journal of Business Venturing 20 (1), 23–45.

146 D.A. Shepherd et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2009) 134–148

Caves, R., Porter, M., 1976. Barriers to exit. In: Qualls, D., Masson, R. (Eds.), Essays on Industrial Organisation in Honour of Joe S. Cambridge,Bain, Ballinger.

Christopherson, L.K., 1976. Cardiac transplant: preparation for dying or for living. Health and Social Work 1 (1), 58–72.Corbett, A.C., 2005. Experiential learning within the process of opportunity identification and exploitation. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice

29, 473–491.Cooper, A.C., Folta, T.B., Woo, C.Y., 1995. Owner-managerial information search. Journal of Business Venturing 10, 107–120.Cooper, A.C., Woo, C.A., Dunkelberg, W., 1988. Entrepreneurs perceived chances for success. J. Business Venturing 3, 97–108.Cova, B., Svanfeldt, C., 1993. Societal innovations and the postmodern aestheticization of everyday life. International Journal of Research in

Marketing 10, 297–310.Cuisner, M., Janssen, H., Graauw, C., Bakker, S., Hoogduin, C., 1996. Pregnancy following miscarriage: curse of grief and some determining factors.

Journal of Psychometric Obstetrics and Gynecology 17, 168–174.Cyert, R.M., March, J.G., 1963. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. Prentice–Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.Davidsson, P., Honig, B., 2003. The role of social and human capital among nascent owner-managers. Journal of Business Venturing 18 (3),

301–332.Dean, T.J., Turner, C.A., Bamford, C.E., 1997. Impediments to imitation and rates of new firm failure. Academy of Management Best Paper

Proceedings.Downing, S., 2005. The social construction of entrepreneurship: narrative and dramatic processes in the coproduction of organizations and identities.

Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 29 (2), 185–204.Friedman, M., 1953. Essays in Positive Economics. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.Garland, H., Newport, S., 1991. Effect of absolute and relative sunk costs on the decision to persist with a course of action. Organizational Behavior

and Human Decision Processes 48, 55–69.Garland, H., Sandefur, C., Rogers, A., 1990. Do-escalation of commitment in oil exploration: when sunk losses and negative feedback coincide.

Journal of Applied Psychology 75, 721–727.Gimeno, J., Folta, T., Cooper, A., Woo, C., 1997. Survival of the fittest? Owner-managerial human capital and the persistence of underperforming

firms. Administrative Science Quarterly 750–783.Goleman, D., 1995. Emotional Intelligence. Bantam Books, New York.Hayward, M.L.A., Shepherd, D.A., Griffin, D., 2006. A hubris theory of entrepreneurship. Management Science 52, 160–172.Heath, C., 1995. Escalation and de-escalation of commitment in response to sunk losses: the role of budgeting in mental accounting. Organizational

Behavior and Human, Decision Processes 62, 38–54.Hogan, N.S., Greenfield, D.B., Schmidt, L.A., 2001. Development and validation of the Hogan Grief Reaction Checklist. Death Studies 25, 1–32.Huy, Q.N., 1999. Emotional capability, emotional intelligence, and radical change. Academy of Management Review 24, 325–345.Jacobs, S., Mazure, C., Prigerson, H., 2000. Diagnostic criteria for traumatic grief. Death Studies 24 (3), 185–199.Karakaya, F., 2000. Market exit and barriers to exit: theory and practice. Psychology and Marketing 17 (8), 651–668.Karlsson, N., Juliusson, E.A., Gärling, T., 2005a. A conceptualization of task dimensions affecting escalation of commitment. European Journal of

Cognitive Psychology 17, 835–858.Karlsson, N., Gärling, T., Bonini, N., 2005b. Escalation of commitment with transparent future outcomes. Experimental Psychology 52, 67–73.Keil, M., Mann, J., Rai, A., 2000. Why software projects escalate: an empirical analysis and test of four theoretical models. MIS Quarterly 24 (4),

631–664.Krugman, P., 1989. Differences in income elasticities and trends in real exchange rates. European Economic Review 33, 1031–1049.Kübler-Ross, E., 1969. On Death and Dying. Spinger, New York.Landier, A., 2004. Entrepreneurship and the stigma of failure. Working paper. University of Chicago.Lazarus, R.S., Folkman, S., 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer, New York.Lee, S.-H., Peng, M.W., Barney, J.B., 2007. Bankruptcy law and entrepreneurship development: a real options perspective. Academy of Management

Review 32 (1), 257–272.Lindemann, E., 1944. Symptomatology and management of acute grief. American Journal of Psychiatry 101, 141–148.Loewenstein, G., Issacharoff, S., 1994. Source dependence in the valuation of objects. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 7, 157–168.Luce, M.F., Bettman, J.R., Payne, J.W., 1997. Choice processing in emotionally difficult decisions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning,

Memory, and Cognition 23 (2), 384–405.MacMillan, I.C., 1986. To really learn about entrepreneurship, let's study habitual entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing 1, 241–243.MacMillan, I.C., Seigel, R., Subba Narasimha, P.N., 1985. Criteria used by venture capitalist to evaluate new venture proposals. Journal of Business

Venturing 1, 119–128.Major, B., Schmader, T., 1998. Coping with stigma through psychological disengagement. In: Swim, J.K., Stangor, C. (Eds.), Prejudice: The Target's

Perspective. Academic, San Diego, CA, pp. 219–241.Major, B., Spencer, S., Schmader, T., Wolfe, C., Crocker, J., 1998. Coping with negative stereotypes about intellectual performance: the role of

psychological disengagement. Personality Social Psychological Bulletin 24, 34–50.March, J.G., 1991. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science 2 (1), 71–87.McGrath, R.G., 1999. Falling forward: real options reasoning and owner-managerial failure. Academy of Management Review 24, 13–30.McGrath, R., Cardon, M., 1997. Entrepreneurship and the functionality of failure. Paper presented at the seventh Annual Global Entrepreneurship

Research Conference. Montreal, Canada.Meyer, M., Zucker, L., 1989. Permanently Failing Organizations. Sage Publications, Newbury Park.Milgram, N.A., Sroloff, B., Rosenbaum, M., 1988. The procrastination of everyday life. Journal of Research in Personality 22, 197–212.Minniti, M., Bygrave, W., 2001. A dynamic model of entrepreneurial learning. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 25, 5–16.

147D.A. Shepherd et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2009) 134–148

Mogg, K., Mathews, A., Bird, C., MacGregor–Morris, R., 1990. Effects of stress and anxiety on the processing of threat stimuli. Journal ofPersonality and Social Psychology 59, 1230–1237.

Mystakidou, K., Tsilika, E., Parpa, E., Katsouda, E., Sakkas, P., Galanos, A., Vlahos, L., 2005. Demographic and Clinical Predictors of PreparatoryGrief in a Sample of Advanced Cancer Patients.

Nord, D., 1996. Issues and implications in the counseling of survivors of multiple AIDS-related loss. Death Studies 20, 389–413.Ohlson, J.A., 1980. Financial ratios and the probabilistic prediction of bankruptcy. Journal of Accounting Research (Spring) 109–131.Parkes, C., Weiss, R., 1983. Recovery from bereavement. Basic Books, New York.Pieters, R.G.M., van Raaij, W.F., 1988. The role of affect in economic behavior. In: van Raaij, W.F., van Veldhoven, G.M., Warneryd, K.E. (Eds.),

The Handbook of Economic Psychology. Kluwer Academic Publishers, London, pp. 108–144.Politis, D., 2005. The process of entrepreneurial learning: a conceptual framework. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 29, 399–424.Prasad, D., Bruton, G.D., Vozikis, G., 2000. Signaling value to business angels: the proportion of the entrepreneur's net worth invested in a new

venture as a decision signal. Venture Capital 2, 167–182.Prigerson, H.G., Shear, M.K., Newson, J.T., Frank, E., Reynolds, C.F., Maciejewski, P.K., Houck, P.R., Bierhals, A.J., Kupfer, D.J., 1996. Anxiety

among widowed elders: is it distinct from depression and grief? Anxiety 2, 1–12.Prigerson, H.G., Bierhals, A.J., Kasl, S.V., Reynolds, C.F., Shear, M.K., Day, N., Beery, L.C., Newsom, J.T., Jacobs, S., 1997. Traumatic grief as a

risk factor for mental and physical morbidity. American Journal of Psychiatry 154, 616–623.Ramos, N.S., Fernandez-Berrocal, P., Extremera, N., 2007. Perceived emotional intelligence facilitates cognitive-emotional processes of adaptation to

an acute stressor. Cognition and Emotion 21, 758–772.Rando, T.A., 1983. An investigation of grief and adaptation in parents whose children have died from cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 8, 3–20.Rando, T.A., 1986. Parental loss of a child. Research Press, Illinois.Rerup, C., 2005. Learning from past experience: Footnotes on mindfulness and habitual entrepreneurship. Scandinavian Journal of Management 21,

451–472.Roach, M., Kitson, G., 1989. Impact of forewarning on adjustment to widowhood and divorce. In: Lund, D.A. (Ed.), Older Bereaved Spouses:

Research With Practical Applications. Hemisphere Publishing Corporation, New York, pp. 185–200.Robinson, M., Baker, L., Nackerud, L., 1999. The relationship of attachment theory and perinatal loss. Death Studies 23 (3), 257–270.Rosenbaum, D.I., Lamort, F., 1992. Entry, barriers, exit, and sunk costs: an analysis. Applied Economics 24 (3), 297–304..Ross, J., Staw, B.M., 1986. Expo 86: an escalation prototype. Administrative Science Quarterly 31 (2), 274–297.Ross, J., Staw, B.M., 1993. Organizational escalation and exit: lessons from the Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant. Academy of Management Journal

36 (4), 701–732.Rothaupt, J.W., Becker, K., 2007. Literature review of western bereavement theory: from decathecting to continuing bonds. The Family Journal

15 (1), 6–15.Salovey, P., Mayer, J.D., 1990. Emotional intelligence. Imagination. Cognition and Personality 9, 185–211.Sanders, C. 1982–1983. Effects of sudden vs. chronic illness death on bereavement outcome. Omega, 13(3): 227–241.Schmidt, J., Calantone, R., 2002. Escalation of commitment during new product development. Academy of Marketing Science Journal 30 (2),

103–129.Schutjens, V., Stam, E., 2006. Starting anew: entrepreneurial intentions and realizations subsequent to business closure. Papers on Entrepreneurship,

Growth and Public Policy #10-2006. Max Planck Institute of Economics, Jena.Schwarz, N., Clore, G.L., 1988. How do I feel about it? The informative function of affective states. In: Fiedler, J.P., Forgas (Eds.), Affect, Cognition,

and Social Behaviors. Hogrefe, Gottigen, Germany, pp. 44–62.Shuchter, S.R., 1986. Dimensions of Grief: Adjusting to the Death of a Spouse. Jossey–Bass, New York.Shepherd, D.A., 2003. Learning from business failure: propositions of grief recovery for the self-employed. Academy of Management Review 28,

318–328.Shepherd, D.A., Douglas, E.J., Shanley, M., 2000. New venture survival: ignorance, external shocks, and risk reduction strategies. Journal of

Business Venturing 15, 393–410.Sinkey Jr., J.F., 1992. Commercial Bank Financial Management–In the Financial Services Industry. MacMillan Publishing Company, New York.Sitkin, S.B., 1992. Learning through failure: the strategy of small losses. In: Staw, B.M., Cummings, L.L. (Eds.), Research in Organizational

Behavior, 14. JAI Press, Greenwich, CT.Staw, B., Barsade, S., Koput, K., 1997. Escalation at the credit window: a longitudinal study of bank executives' recognition and write-off of problem

loans. Journal of Applied Psychology 82 (1), 130–142.Stroebe, M.S., Schut, H., 1999. The dual process of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Studies 23, 197–224.Thorne, J.R., 1989. Alternative financing for entrepreneurial ventures. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice Spring 7–9.Tversky, A., Kahneman, D., 1981. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 211, 453–458.Ucbasaran, D., Westhead, P., Wright, M., 2006. Habitual Entrepreneurs. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.Van Dijk, E., van Knippenberg, E., 1996. Buying and selling exchange goods: loss aversion and the endowment effect. Journal of Economic

Psychology 17, 517–524.Van Eerde, W., 2000. Procrastination: self-regulation in initiating aversive goals. Applied Psychology: An International Review 49, 372–389.Van Witteloostuijn, A., 1998. Bridging behavioral and economic theories of decline: organizational inertia, strategic competition and chronic failure.

Management Science 44 (4), 502–519.Wells, A., Matthews, G., 1994. Attention and Emotion: A Clinical Perspective. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Ltd., Hove, UK.Werth, J.L., 2005. Becky's legacy: Personal and professional reflections on loss and hope. Death Studies 29 (8), 687–736.Wiegand, D.L., 2006. Withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy after sudden, unexpected life-threatening illness or injury: interactions between patients'

families, healthcare providers, and the healthcare system. American Journal of Critical Care 5 (2), 178–187.

148 D.A. Shepherd et al. / Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2009) 134–148

Williamson, O.E., 1991. Comparative economic organization: the analysis of discrete structural alternatives. Administrative Science Quarterly 36,269–296.

Wilson, J.L., 1977. Anticipatory grief in response to threatened amputation. Maternal-Child Nursing Journal 6 (3), 177–186.Wortman, C.B., Silver, R.C., 1989. The myths of coping with loss. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 57, 349–357.Wortman, C.B., Silver, R.C., 1992. Reconsidering assumptions about coping with loss: an overview of current research. In: Montada, L., Filipp, S.H.,

Lerner, M.S. (Eds.), Life crises and experiences of loss in adulthood. Erlbaum, Hillsdale NJ, pp. 341–365.Wright, M., Robbie, K., Ennew, C., 1997. Venture capitalists and serial entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing 12 (3), 227–249.Yoshikawa, T., Phan, P.H., Linton, J., 2004. The relationship between governance structure and risk management approaches in Japanese venture

capital firms. Journal of Business Venturing 19, 831–849.Zmijewski, M.E., 1984. Methodological issues related to the estimation of financial distress prediction models. Journal of Accounting Research 24,

59–82 (Supplement).