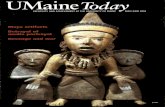

Maya: Creating power and identity trought art

-

Upload

uni-saarbruecken -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Maya: Creating power and identity trought art

Ancient Mesoamericahttp://journals.cambridge.org/ATM

Additional services for Ancient Mesoamerica:

Email alerts: Click hereSubscriptions: Click hereCommercial reprints: Click hereTerms of use : Click here

ANCIENT MAYA ROYAL STRATEGIES: Creating power and identity throughart

Julia L. J. Sanchez

Ancient Mesoamerica / Volume 16 / Issue 02 / July 2005, pp 261 - 275DOI: 10.1017/S0956536105050121, Published online: 28 March 2006

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0956536105050121

How to cite this article:Julia L. J. Sanchez (2005). ANCIENT MAYA ROYAL STRATEGIES: Creating power and identity through art. AncientMesoamerica, 16, pp 261-275 doi:10.1017/S0956536105050121

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/ATM, IP address: 134.96.198.162 on 22 Nov 2014

ANCIENT MAYA ROYAL STRATEGIES

Creating power and identity through art

Julia L. J. SanchezCotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1510, USA

Abstract

Ancient Maya monumental art was designed to enact the physical, social, and ritual hierarchy. Physically, sculpture createdbarriers and access patterns that altered movement through sites. Monumental architecture separated ritual participants in buildingsfrom audiences in the plazas below. Access to monuments and portrayals on monuments in part defined social and powerhierarchies. Motifs were altered to communicate various forms of power appropriate to each context and audience. Complexsupernatural themes and ritual roles demonstrated hierarchical differences among the ruler and other nobles, while more simplisticrepresentations of a powerful ruler demonstrated the separation of the ruler from commoners.

Ancient Maya monuments have been viewed as representations ofpower, ideological beliefs, and social systems. Monuments in-clude structures and large sculpture such as stelae that were carvedwith information about cosmologies and hierarchies of power. Thisstudy builds on previous research by taking the opposite and com-plementary view: where George Andrews (1975:24) discussed theinfluence of political, administrative, social, and economic life onthe arrangement of space, this study views physical space as anactive part of the creation of political, administrative, social, andeconomic life. The ancient Maya used space, architecture, and artnot as mere reflections of power, but to create and maintain power.Economic interaction and wealth are traditionally used by archae-ologists to identify hierarchies, yet monumental art was crucial inthe development of hierarchies, as well. Structures create varioussettings for imagery, dividing spaces and creating different levelsof access. In this sense, monumental art was active in society,determining how space, and therefore activity and interaction, weredivided. To the ancient Maya, art was a living part of society and,as such, was used to communicate and to create social relationships.

Previous studies have examined structures, site layouts, andart as clues to interpreting ideology and social organization (An-drews 1975, 1995; Ashmore 1989; Hendon 1992; Hohmann andVogrin 1982; Miller 1986:78–80; Proskouriakoff 1960). Zelia Nut-tall (1900:282–283) described Mesoamerican temples as represen-tations of mountains, an idea expanded later by Andrews (1975:12–13, 70), who claimed that temples allowed priests to ascendhigh above public spaces to come closer to the supernatural world,and by Linda Schele and David Freidel (1990), who includedrulers as well as priests. Other studies have used imagery andtexts, the content of the monuments, to interpret ideology (Miller1986a, 1986b; Schele and Freidel 1990; Schele and Miller 1986;Stuart 1987). Some have framed the discussion in terms of public

and private art, where public art is meant for large groups ofpeople and private art is meant for the few nobles allowed to enterstructures (Miller 1986:78–80; Schele and Miller 1986:34–35).

Building on previous interpretations, this study combined ap-proaches from several fields into a systematic, multidisciplinary ap-proach (for a full discussion of methods, see Sanchez 1997). Thegoal is to examine how monuments are used to create and maintainpower and social relationships. The relationship between contentand context of monuments provides the basis for interpretation, wherecontent is the information communicated through images, text, andother aspects of form and style, and context provides the setting forthe content and its intended audience. Stelae in plazas have a dif-ferent audience from that of lintels inside a temple. The content ofthe monuments provides a view of society (usually created by theruler who commissions the monuments; Marcus 1992:8–16; Scheleand Miller 1986:33), while the context influences who receives themessage. This paper examines how rulers use monuments to createdifferent contexts, then vary the content of monuments to createpower and define social roles.

For this study, five sites were chosen that had a large sample ofmonuments with contextual data: Copan, Palenque, Quirigua, Ti-kal, and Yaxchilan. The analysis is qualitative rather than quanti-tative. Even at large sites, the number of monuments (as few as 3to as many as 43) does not allow statistically significant compar-isons between sites, types of monuments, time periods, or themes.Each of the five sites has a substantial history of archaeologicalresearch and art-history interpretation to provide a foundation forfurther interpretation and comparison. To identify patterns in thecontent of monuments, methods from the ethnography of commu-nication were applied (Hymes 1986; for archaeological applica-tions, see Love 1983 and Whitley 1994). Context was examinedusing access analysis, which measures the relative degree of ac-cess to areas within a site by the ease with which one may movebetween areas (Fairclough 1992; Foster 1989; for an archaeolog-ical application, see Moore 1992).E-mail correspondence to: [email protected]

Ancient Mesoamerica, 16 (2005), 261–275Copyright © 2005 Cambridge University Press. Printed in the U.S.A.DOI: 10.1017/S0956536105050121

261

MONUMENTS AND ACCESS

Each of the five sites is arranged with open plaza areas and rela-tively more restricted areas labeled acropoleis or palaces (Fig-ures 1–5). Plazas were the location for public rituals, orientedtoward a broad audience. All five sites had multiple public plazaswith open access, although the plazas may be defined as separatespaces. Palenque’s Cross Group and the Twin Pyramid Groups atTikal may be exceptions, being plazas to which access was re-stricted. Their construction indicates public access, although per-haps not as extensive as in the main plazas at both sites.

Structures on the edges of plazas had restricted access. Rela-tively few could enter these structures, and those who ascendedthe steps of the structure were demonstrating their ability to inter-act with the monument. Structure 10L-26 at Copan, Structure 1A-3at Quirigua, Temples I and II at Tikal, the Temple of Inscriptionsat Palenque, and Structure 20 at Yaxchilan all face public plazaareas. The plaza is a setting for public ritual, but it is also a placefor an audience to witness those few who were allowed to enterthe structures above. The audience in the plaza below acknowl-edged the higher status of those ascending the steps. The interiorsof structures were the context for relatively private ritual, whilethe exteriors of structures were stages on which rituals were per-formed for the audience in the plaza below.

An acropolis is composed of groups of structures on raisedplatforms that served as locations for more restricted, private rit-ual. Platforms and some structures create physical barriers be-tween the surrounding plazas and the acropolis itself. Entrance toan acropolis may be relatively simple such as climbing the stepson the north side of Quirigua’s Acropolis, or complex such as atTikal’s labyrinthine Central Acropolis. Even a staircase restrictedaccess to the acropolis to a few who, by entering the acropolis,demonstrated their higher status. Once in the acropolis, furtherdivisions mimicked those on the main plazas, as some peoplewould be restricted to plazas or courtyards in the acropolis whileothers were allowed to enter the structures. At Copan, Structures10L-16 and 10L-22 and other structures were relatively more re-stricted than the East and West Courts below. Within an acropolis,society was further subdivided as some acted out their highersocial status and ability to enter structures, interacting with themonuments and the ruler more closely. Monumental art, whichwas created by the ruler, depicts the ruler as the top of the hierar-chy and as allowed unrestricted access to everything.

CREATING ROYAL POWER

In addition to physical access to monuments, variations in themonuments themselves created different contexts and communi-cated information about power and society. A modified dominantideology theory suggests that each class or group in society maybe unified by its own ideology (Abercrombie and Turner 1982;Abercrombie et al. 1982). The dominant or ruling ideology maynot be accepted by other groups in society. While not all aspects ofthis model fit the Classic Maya, the ruling ideology of the Mayawas not directed in the same way at each group in society. At all ofthe sites, images differed according to their context. Public mon-uments defined the ruler’s power, and architectural sculpture cre-ated a supernatural setting for ritual (Andrews 1975:12–13; Scheleand Freidel 1990). Sculpture located at lower elevations in rela-tively more public areas emphasized the image of the ruler. Otherimagery or people might be included, but the ruler’s image dom-

inates the scene by size or position. As the one who commissionedthe monuments, the ruler could use them to communicate his/herview of society. In the ruler’s view, the ruler was the dominantliving member of society, whose image was placed on stelae inplazas to communicate this identity to all of Maya society. In thecentral area of each site is a large public plaza with a gallery ofruler portraits (Figure 6). Plazas were used in a variety of ways: asthe setting for public ritual, for processions, and for markets andother daily activities (Andrews 1975:10–13, 37), so the images ofthe ruler in plazas were visible to the largest, broadest audience.People interacted with the portraits daily, walking past them, andcontinually acknowledging the ruler’s position.

An exception is Palenque, where ruler portraits are placed onthe piers of structures above the plaza rather than on stelae (Fig-ure 7). The portraits are similar in placement to those at other sitesbecause they are located below the supernatural architectural sculp-ture, which is on the facades and roof combs. The portraits differfrom those at other sites in that, although they are visible to ageneral audience, the audience is not allowed to interact directlywith them. Only those allowed to ascend the steps of the structureswere able to interact with the ruler. This placement appears todistinguish the rulers from the general audience at Palenque morethan at other sites.

Although the ruler’s image is dominant, other motifs on thestelae conveyed sources of the ruler’s power. Ideological powercame from the ability to commune with the supernatural, so publicmonuments showed the ruler with deities and ancestors to create aunique relationship (for complete discussions of ancient Mayaconnections to ancestors through art and architecture, see McAnany1995, 1998). At Copan, Quirigua, and Tikal, stelae portray theruler in ritual costume, with cosmological figures around (Fig-ures 8–9). Even with cosmological imagery, the ruler’s image dom-inates the scene. At Palenque and Yaxchilan, the images are moredynamic, showing the ruler performing rituals (Figures 7, 10).Stelae at Yaxchilan have deity masks below and ancestor car-touches and deities above, showing the ruler in the middle worldof the tripartite Maya universe. At Palenque, the ruler portraits areconflated with architectural imagery, showing the ruler perform-ing rituals on the piers, with supernatural imagery above, suggest-ing that the rituals were performed within a mythological context.

Images were altered to adapt to current sociopolitical situa-tions. K’ak’ Tiliw Chan Yoaat of Quirigua (also known as Butz’Tiliw or Cauac Sky) included warrior imagery and ritual imageryon his stelae (Figure 9). He achieved his status through the mili-tary defeat of Waxaklajuun Ub’aah K’awiil of Copan (also knownas 18 Rabbit), so he continually re-created his military power onan almost equal level with his ideological power. Tikal and Yax-chilan also erected portraits of rulers in military costume duringtimes of conflict (Figure 10). Yaxchilan devoted much of the im-agery facing the river, facing visitors entering the site, to the rul-er’s military achievements.

Unlike monuments in plazas, on architecture the supernaturalimagery dominates. The exteriors of structures were designed tobe visible from the plaza below, setting a stage for ritual. Whenparticipants ascended the steps of a structure, they entered a spacewhere they were physically dominated by cosmic imagery as theymetaphorically entered the supernatural world (Andrews 1975:10–13; Schele and Miller 1986:66). One moved from the terrestrialworld of the plaza with images of the ruler to the supernaturalworld with cosmological imagery. The images of deities or super-natural motifs such as water bands and sky bands separated the

262 Sanchez

Figure 1. Map of Copan (adapted by Anthony Graesch from Fash 1991:Figure 8).

Creating power and identity through art 263

participants in the plaza from those in the structure above by plac-ing them in different worlds. Stephen Houston (1998) describescosmological associations of architectural features in detail. Mov-ing up a stairway carved with dynastic histories, such as Copan’sStructure 10L-26, the Hieroglyphic Stairway, moves one fartherback along the ancestral line of rulers, into the dynastic past aswell as the supernatural realm (Houston 1998:356–357).

On some structures, the ruler was depicted with the super-natural imagery; at Yaxchilan, Palenque, Tikal, and perhaps partsof the Acropolis at Copan, figures were shown seated on throneson the roof combs (Figure 11). The thrones and costumes indicate

that the rulers were human rather than deities. The ruler was shownwithin a cosmic setting, demonstrating ideological power throughcommunion with the supernatural. Palenque’s structures are slightlydifferent, depicting the ruler on piers rather than on stelae, but asat all sites, ruler portraits were dominant below while mytholog-ical imagery was dominant above. The structure conflated thepublic images of rulers with the supernatural imagery but still keptthem separate.

Structure 33 at Yaxchilan is the dominant structure above theMain Plaza, but it is also the least visible. Because the structure isset back from the staircase that leads to it, only the roof comb andupper facade are visible from the plaza and from the river. Thevisible portion shows the ruler seated on a throne, surrounded bymythological imagery (Tate 1992:131). Although the rituals con-ducted within the structure were not visible, the structure itselfwas a constant reminder of the ruler’s place within the super-natural and unique ideological power.

The interiors of structures above the plazas were the setting forprivate rituals where the ruler interacted with deities and ances-tors, creating power through ritual. Inside structures, imagery con-tinued to emphasize the ruler’s place within the supernatural,creating a context for ritual. Relatively few elite entered struc-tures, and they did so when participating in private ritual. Theimagery created a supernatural context and conveyed specific mes-sages to the elite audience. The elite had power, and their power-ful position may have been threatening to the ruler, so the rulerwas distinguished from others through action, costume, and thesurrounding monuments. Inside structures, the ruler was por-trayed participating in ritual, communing with the supernatural,performing acts that the other members of the elite could not. AtCopan, the inner doorway of Structure 10L-22 is a representationof the cosmos (Fash 1991:Figure 77; Schele and Miller 1986:302). When the ruler stood in the doorway, he was shown as thecenter of the universe, a blatant message to those entering thestructure of his central position not only in ritual, but also for thepreservation of the cosmos. These images demonstrated the dis-tinct ideological power of the ruler from other ritual participants.By standing within and among such monuments, the elite audi-ence acknowledged and accepted the ruler’s position.

Ritual acts were depicted differently in public and private spaces,with private scenes including more details of the actions and ob-jects involved. Palenque’s exterior building piers had various sim-ple scenes, while the interiors of structures in the Cross Group hadmore elaborate images with more detailed depictions of ritual im-plements and sacred objects. Yaxchilan stelae depicted relativelysimple, graphic portraits of the ruler with blood dripping from hishands, while the more private lintels presented the bloodlettingritual itself, not just the result. On the lintels in Structures 21 and23, the ruler and others were shown in the process of auto-sacrifice with ritual implements such as bloodletters, associatedbowls, paper, and Vision Serpents (Figure 12; see also Grahamand von Euw 1977:39, 41, 43, 53, 55–56). The act of letting bloodand these ritual objects were shown in these private contexts, whilethey were never shown in the public contexts. It may have beeninappropriate for ritual implements or the ritual process to be dis-played outside the ritual context.

Other rituals are depicted in structures that may have been thesettings for the rituals. Tikal Temple III, Lintel 2, shows the rulerperforming a ceremony with two other individuals in which allthree hold staves and tri-bladed knives (Figure 13; Jones andSatterthwaite 1982:Figure 72). The ruler is clearly the dominant

Figure 2. Map of Quirigua (adapted by Anthony Graesch from Sharer1990:Figure 1).

264 Sanchez

figure, wearing an elaborate jaguar costume. The Cross Group ofPalenque shows K’inich Kan B’alam II (also known as ChanBahlum II) in various ritual acts associated with his heir designa-tion, accession, and the dedication of the temples, all crucial events(Schele and Freidel 1990:Figures 6:11– 6:13). The Cross Grouppanels demonstrated to others entering the structures that KanB’alam II was named as the successor of Pakal (also known asPacal); that he became ruler; and that he alone could dedicatestructures to the gods and commune with them. The objects heldby Kan B’alam II were held only by rulers and create an intimateconnection to the gods. At Yaxchilan, the ruler was depicted inbloodletting rituals, such as those described earlier, in solsticecelebrations and in numerous other ceremonies of which the de-tails are unknown.

DEFINING SOCIAL ROLES

Rulers also defined the social roles of others in Maya societythrough the images on monuments. The ruler chose to show otherparticipants in particular contexts. Such images provide informa-tion about some social interaction, such as which members ofsociety participated in various rituals. Since these images werecommissioned by the ruler, they depict what the ruler wanted toconvey. The monuments show individuals whose prestige and sup-port was important to the ruler. Monuments depict activities thatwere significant in creating social and power distinctions betweengroups. The strategy of each ruler, the participants and activitiesdepicted, provide information about the unique circumstances inthe sociopolitical environment. Examining the participants and

activities depicted and comparing them to their context and audi-ence reveals more about social roles and interaction than merenames and dates; the monuments reveal who participated in whatactivities and how they were important to the social and powerstructure.

Rulers as Dominant

Maya rulers are frequently the dominant human figure in scenesfrom monumental art. The rulers may be represented alone or withother individuals, but the size, posture, and placement of the rulerusually indicates that the ruler is the central figure. The ruler maybe slightly larger than other individuals in the scene, placed in thecenter of the composition, and may be standing above other fig-ures, or other individuals in the scene may be facing the ruler.

At Copan and Quirigua, the dominance of rulers is taken to theextreme of excluding other figures entirely. Copan and Quiriguahave fewer representations of non-rulers than other sites. At Qui-rigua, no living person other than the ruler was depicted on mon-uments. On stelae, the ruler was shown holding military or ritualobjects. On zoomorphs, the ruler was seated within the mouths ofsupernatural beings. Only the ruler was recorded performing rit-uals and taking captives, although the texts mentioned powerfulallies, parents, and captives. By excluding images of non-rulers,and by focusing on the actions of the ruler in texts, the monumentsof Quirigua emphasized the individual power of the ruler. Otherswere mentioned only to enhance that power, defining politicalrelationships, genealogical rights to rulership, and successful mil-itary endeavors.

Figure 3. Map of Tikal (adapted by Anthony Graesch from Coe 1967:20).

Creating power and identity through art 265

Figure 4. Map of Yaxchilan (adapted by Anthony Graesch from Graham and von Euw 1977:6–7). Scale in meters.

266Sanchez

In the early stages of political development at all sites, onlyrulers are mentioned on monuments. When first establishing aruling dynasty, rulers had to create individual power that was sep-arate from that of everyone else in society. Most rulers empha-sized ideological power and control of ritual. Quirigua, the smallestsite included in the study, had a relatively short history of rulersthat erected monuments. Monumental texts primarily refer to K’ak’Tiliw Chan Yoaat and his two successors (Looper 1995, 1999).

K’ak’ Tiliw Chan Yoaat was a provincial lord of the Copan politywho ruled Quirigua (Looper 1999:268). His power increased, andhis rule became independent after his extraordinary defeat of Wax-aklajuun Ub’aah K’awiil of Copan (Looper 1995:90–124, 1999:268–274; Marcus 1976:134–140; Proskouriakoff 1973:168). Afterhis victory, K’ak’ Tiliw Chan Yoaat had to establish an office ofrulership that differentiated him from other lineage heads. Powerwas usurped from Waxaklajuun Ub’aah K’awiil through monu-

Figure 5. Map of Palenque (adapted by Anthony Graesch from Schele and Freidel 1990:Figure 6:5).

Figure 6. Tikal, Great Plaza showing the gallery of ruler portraits on rows of stelae.

Creating power and identity through art 267

mental art; K’ak’ Tiliw Chan Yoaat copied and re-created Waxak-lajuun Ub’aah K’awiil’s monuments (Looper 1995) combiningideological and military themes.

At Copan, most monuments also excluded non-rulers. Stelaedepicted only contemporary rulers. Altar Q and the Structure 10L-11step depicted the ruler seated with all predecessors in the dynasty(Schele and Freidel 1990:Figure 8:3; Schele and Miller 1986:Plate 36). Architectural sculpture focused on supernatural imag-ery, with occasional portraits of the ruler, such as Yax Pasaj ChanYoaat (also known as Yax Pac), on the doorjambs of Structure10L-18 (Grube and Schele 1990:3). Non-rulers were not depicted,except on the Hieroglyphic Stairway. On the treads of seven steps,seen only by the few allowed to climb them, were captives. Thestairway was built after the defeat of Waxaklajuun Ub’aah K’awiiland was an attempt to reassert the military prowess of Copan’srulers. By stepping on the captives, the military victories of therulers were reenacted. Captive imagery was not seen previously atCopan because military power was less significant than ritual powerin ensuring rule.

Another aspect of artistic style at Copan and Quirigua was thelack of active scenes; only static portraits are present. When non-rulers were shown at other sites, they were participating activelywith the ruler. The ruler was depicted as dominant by his size,costume, and actions. Copan and Quirigua limited their monu-ments to portraits of the ruler. Although rituals and captures were

not represented in images at Copan and Quirigua, they are re-corded in texts. Similar events occurred, but had different mean-ings than at other sites. At Copan and Quirigua, military powerwas less influential than at sites such as Tikal and Yaxchilan;Copan and Quirigua only used captive and warfare imagery dur-ing and after their conflicts with each other. When Copan wasdefeated by Quirigua, Copan’s rulers used images of captives onStructure 10L-26, the Hieroglyphic Stairway, to regain authorityat Copan. Since Tikal and Yaxchilan were involved in frequentconflict, the military prowess of the ruler was more significant.

Sharing the Stage

Although rare at Copan and Quirigua, non-ruler participants areincluded in images at other sites. Depicting other individuals wasa deliberate effort to show interaction in a manner that was ben-eficial to the ruler. Ancestors created a link to the past and dem-onstrated the inheritance of power; captives show military strength;and other ritual participants add to active scenes and enhance theprestige of the participants as well as the rulers.

At all sites, genealogical information was presented in texts,and at all sites except Quirigua, genealogies were represented vi-sually with images of ancestral rulers and sometimes other par-ents. Because rulership and power were inherited, the ruler had tocreate a genealogical right to rule. At Copan and Tikal, parental

Figure 7. Palenque Palace, House A, Column B. The ruler por-traits at Palenque are placed on building piers, such as thisone, rather than on stelae.

268 Sanchez

portraits focused on ancestral rulers to create continuity in theruling dynasty. Ancestral rulers were apotheosized after death andthus were powerful supernatural allies. At several sites, rulersbuilt on places tied to ancestors. Copan’s Structures 10L-16 and10L-26 were traditionally associated with the founder and thesources of dynastic power, and subsequent rulers continued tobuild on those locations, often making references in iconographyand texts to the earlier rulers (Agurcia 1996; Fash 1991:22, 26, 74,78–81, 100, 135, 139–151, 168–170; Fash et al. 1992; Sharer,Fash, Sedat, Traxler, and Williamson 1999; Sharer, Traxler, Sedat,Bell, Canuto, and Powell 1999).

In Tikal’s North Acropolis, monuments depicted dynastic his-tories that showed apparently unbroken links in the inheritance ofpower. At Copan, Altar Q and the step of Structure 10L-11 re-corded portraits of the entire dynasty witnessing the accession ofa ruler (Schele and Freidel 1990:Figure 8:3; Schele and Miller1986:Plate 36). The Hieroglyphic Stairway at Copan seems tohave been more selective, focusing on more recent ancestors andmilitary exploits. At Palenque, the Cross Group panels and theTemple of Inscriptions linked the ruler to the dynasty and evenconnected the ruling dynasty to gods (Schele and Freidel 1990:Figures 6:14– 6:16). The connections to deities enhanced super-natural ties and ideological power. Tikal and Yaxchilan used imagerymore often than dynastic histories. A few stelae at Tikal includeportraits of the ruler’s father and predecessor on the sides, lendinghis support. Yaxchilan stelae often included ancestor cartouchesabove the ruler. At Yaxchilan, mothers were included in genealog-ical statements more often than at other sites. Yaxchilan may haveenhanced the status of its rulers by mentioning the powerful statusof their wives and mothers (Marcus 1976; Robin 2001).

Genealogical rights to rulership were mentioned more fre-quently or emphasized in times of crisis. Moon Jaguar of Copanwas the son of Waterlily Jaguar, but two others (possibly brothersof Moon Jaguar) ruled between this father and son (Fash 1991:96;Schele and Stuart 1986:3). Moon Jaguar had to re-create his ge-nealogical ties to his father, so he created spatial ties to his father’ssacred space by building additions onto Waterlily Jaguar’s struc-tures (Morales et al. 1990:1; Schele and Morales 1990:1). Pakal ofPalenque and Bird Jaguar IV of Yaxchilan both inherited the rightto rule through their mothers (Schele and Freidel 1990:221; Tate1992:123–125), and their genealogical statements were more prom-inent and included their mothers. On the Oval Palace Tablet, Pakalreceives a headdress from his mother on the date of his accession(Schele and Freidel 1990:227, Figure 6:7). She was a prominentpart of the ceremony, and the father was not pictured, because it isonly through the mother that Pakal inherited the right to rule. BirdJaguar IV dedicated Structure 21 and Stela 35 inside of it to hismother (Graham and von Euw 1977:Figures 39, 41, 43; Tate 1992:125, 129–130). The images of mothers at Palenque and Yaxchilanwere often in private contexts, where they would be seen by eliteparticipants in ritual. The role of the women was not unknown tothe general population, and women were presented in public con-texts, but the genealogical relationship was emphasized to an eliteaudience to create an inheritance of power.

Images also may have been a visual representation of genea-logical information to a less literate audience. Relatively few inMaya society attended schools and could read hieroglyphic writ-ing (Houston 1994). Although genealogical ties were more signif-icant to an elite audience, the ruler demonstrated lineage ties tolarge, broad audiences, as well. Tikal and Yaxchilan stelae in-cluded information about parents and inheritance. In the case of

Figure 8. Copan Stela A, east side, showing the ruler in costume holdinga serpent bar.

Creating power and identity through art 269

Palenque, no monuments were in the plaza to convey genealogicalinformation, so images on building piers presented the informa-tion where it could be seen from below.

In addition to genealogical representations, non-rulers werealso presented in dynamic images at Tikal, Palenque, and Yaxchi-lan depicting particular rituals: dances, bloodletting ceremonies,captures, and other rituals. At all three sites, the images occurredrelatively late in the monumental history of the site at times when

the rulers were struggling to maintain power. As populations grewand competition between nobles increased, the rulers had to main-tain support to remain in power. Rulers needed to share powerwith other nobles while maintaining a superior position, so theycreated scenes in which other nobles participated in ritual. Thenobles shown achieved a powerful position by sharing some ofthe ideological and military power of the ruler. Such images gavepower to nobles who supported the ruler and showed that the ruler

Figure 9. Quirigua Stela E, south side, showing the ruler in costume holding a shield.

270 Sanchez

was supported by influential people. Although other nobles par-ticipated in rituals, they did not have the supernatural power thatthe ruler had, allowing the ruler to maintain dominance by retain-ing some exclusive ritual rights and activities.

Lintel 2 of Temple III at Tikal showed the ruler and two meninvolved in a ritual (Figure 13). Lintel 2 was placed inside a struc-ture where it would be seen only by a limited elite audience. Itdemonstrated the support of other nobles yet still emphasized theruler’s dominance. Tikal Altar 5, inside the stela enclosure in Com-plex N, showed the ruler and another man standing over a pile ofbone (Jones and Satterthwaite 1982:125). Because the two figuresare shown on the top of the altar, one had to enter the enclosure tosee the image, a restricted context. On Tikal Temple II, Lintel 2, a

ruler’s wife was depicted by herself, giving her high enough statusto be shown alone on a monument (Jones and Satterthwaite 1982:100). The only non-rulers depicted on public monuments at Tikalshowed captives, demonstrating the ruler’s military power. Suchmonuments were created only in times of military conflict, whenthe ruler needed to emphasize military power in addition to ritualpower. Joyce Marcus (1974) suggested that such images wereattempts to create the appearance of military power when it maynot exist or be secure. On public monuments, captives created adominant position for their captor (Johnston 2001).

At Palenque and Yaxchilan, the ruler was often shown withparents, wives, and other people in public and private contexts. AtPalenque, the images depicted ritual activities, often dancing. ThePalace piers depicted the ruler dancing while ritual assistants sit tothe sides (Figure 7). The identities of these other figures are un-known. They may have been members of the ruling family orother nobles participating in the ceremony, ritual assistants of lowerstatus, or perhaps captives. Since there is little evidence to suggestthat the figures are captives, and assistants of lower status wouldnot be depicted so prominently, they are likely noble participantsin the ceremony. As discussed earlier, the presence of allies atsuch an occasion would have demonstrated their support to theruler. By displaying their presence and support, the ruler’s pres-tige was enhanced, and the prestige of the nobles likely was en-hanced, as well.

At Yaxchilan, participants were shown as captives, militaryallies, and ritual participants. The ruler was shown more oftenwith other figures than alone, and the other figures included wereparents, wives, and members of other lineages. Stelae at Yaxchi-lan show military images on the sides facing the plazas and scat-terings on the sides facing the structures. In military images, theruler was usually shown alone or with a captive cowering under-foot. The image conveyed the ruler’s military strength and successin battle. In ritual scenes on stelae, the ruler was shown as oftenwith ritual participants as alone. The participants include kneelingmen, who are assistants of lower status, and woman who standfacing the ruler. Some of the assistants may actually be captives;their poses are similar to those of kneeling captives in militaryscenes.

On private monuments at Yaxchilan, the non-ruling partici-pants have more prominent roles. In capture scenes, the ruler sub-dued captives in more dynamic poses than on stelae. Militaryallies were shown standing nearby (Lintel 12; Graham and vonEuw 1977:33) or actively taking captives of their own (Lintel 8;Graham 1979:27). Both images occurred late in the site’s history,about a.d. 750. The ruler, faced with competitive nobles, had toportray the military support of other nobles. Rituals were moreprominent contexts for elite interaction on monuments. On thelintels of Structures 21 and 23, women performed bloodlettingswith the ruler. On the lintels of Structures 1, 2, 13, 20, 33, and 42,the ruler was shown standing with a man or a woman who heldritual implements (Graham 1979:Figures 21, 23, 25, 27, 73, 75,91, 93, 95, 109; Graham and von Euw 1977:Figures 13, 15, 17,29, 33, 35, 37). In Structures 1, 2, and 33, the non-ruling malesheld objects similar to those held by the ruler, participating on alevel almost equal to the ruler. As it was at other sites, the supportof other noble lineages was critical to the ruler—and perhaps evenmore so at Yaxchilan than at other sites. Participation of othernobles in ritual appears to have been more common, with thenon-ruling participants taking on greater roles while the ruler gainedstrength through their support.

Figure 10. Yaxchilan Stela 20 showing the ruler in military costume stand-ing over a captive. Drawing by Carolyn E. Tate.

Creating power and identity through art 271

Figure 11. Palenque Temple of the Sun, roof comb. Drawing by Merle Greene Robertson (after Griffin 1978:Figure 19).

Figure 12. Yaxchilan Lintel 17 showing the ruler’s wife and the ruler performing a bloodletting ritual (from Graham and von Euw1977:Figure 43; reprinted with permission).

272 Sanchez

DECENTRALIZATION OF POWER

As each site declined, there was an increase in the imagery pro-duced by and depicting individuals other than the ruler. At Copan,sculpture in the elite residential area Las Sepulturas became moreabundant and more elaborate. At Tikal, sculpture found in othergroups also increased. Tikal Temple III, Lintel 2. included non-rulers participating in ritual. At Palenque, the Tablet of the Slavescommemorated the war exploits of a sahal, a noble under theauthority of the ruler (Fash 1991:136; Schele and Freidel 1990:469). At Yaxchilan, the Southeast Group monuments increased

and may have depicted figures who were not of the ruling family.These images represented both attempts by the ruler to maintainpower and the loss of control over the production of monuments.As populations increased, more people were competing for thesame amount of power. Nobles competed for positions of prestige.Rulers, wanting to maintain the support of the nobles, attemptedto divide power and create new positions. Nobles of high statuswho supported the ruler were depicted on monuments or allowedto erect their own. Nobles who participated in rituals on monu-ments were seen as higher in status, being physically and symbol-ically elevated above others. Another means of gaining support

Figure 13. Tikal Temple III, Lintel 2, showing the ruler in a jaguar costume flanked by two other participants (from Jones andSatterthwaite 1982:Figure 72; reprinted with permission).

Creating power and identity through art 273

was to allow nobles to erect their own monuments. The rulers mayactually have had little choice in the matter. Preventing the use ofmonuments may have led to open conflict with the nobles—exactly what the ruler wanted to avoid. Allowing the productionof monuments by other groups was the only choice.

CONCLUSIONS

Art communicated different messages in different contexts andfor different audiences. The way in which the content of monu-ments was altered according to audience provides information aboutthe relationship between social groups that can be compared withother archaeological and ethnohistoric data. The context of themonument determined the audience, and the goals for each mon-ument differed according to the audience. Rulers had to present

themselves as leaders to everyone, and specifically as ritual lead-ers to elite.

The activities conducted in each context also determined ap-propriate imagery. Relatively private rituals in structures requireda supernatural setting. The participants on the monuments alsoshow categories of social relationships. At Yaxchilan and Palen-que, support of other nobles was prominently displayed, and ge-nealogical relationships were represented visually. Copan, Quirigua,and Tikal used more static representations that focused on theprimary power of the ruler. The participants on monuments alsoshowed beliefs about gender roles. The participants displayed incertain activities showed different roles for men and women. Al-though this discussion is brief, these patterns show the benefits ofa systematic study of multiple variables compared between mon-uments and between sites that focus on art within a social context.

RESUMEN

El arte monumental maya precolombino está examinado como una parteactiva de su contexto social usando un acercamiento que combina métodosy teorías de la antropología, la historia del arte y la lingüística. El arte enla sociedad maya fue diseñado para representar la jerarquía física, social yritual. Más bien que imágenes estáticas, el arte era parte de la interaccióncotidiana, influyendo la manera en que la gente transitaba por sus sitios yla manera en que los grupos interactuaban. El acceso a ciertas áreas y, porlo tanto el arte que esas áreas contenían, estaba restringido. Cuando separaban encima de las plataformas, las élites mostraban físicamente lajerarquía social. Rango social y posición física estaban relacionados a lospapeles rituales. Los motivos iconográficos y jeroglíficos en los monu-mentos creaban distinciones en contextos para distintas ocasiones, permi-tiendo al gobernante comunicar varias formas de poder apropiadas a cadacontexto y a cada público. Las esculturas públicas que eran accesibles a

los grupos grandes de gente, enfatizaban al gobernante como un soberanopoderoso. Las esculturas arquitectónicas creaban un contexto metafóricosobrenatural en el cual se realizaban los rituales, mostrando el poderideológico único del gobernante a los demás participantes. Durante tiem-pos de crisis militar, el gobernante usaba atuendo de guerrero, armas ycautivos para ostentar su poder militar. En situaciones cuando se necesit-aba apoyo adicional, se representaba al gobernante participando en ritu-ales con otros nobles, estos como aliados poderosos. Las representacionesde actividades de la gente común mostraban sus relaciones a los gober-nantes y sus papeles en la sociedad. Por medio de una consideración delarte como fenómeno activo y una examinación de cómo fue cambiando envarios contextos sociales, se puede identificar el papel del arte en ladefinición de las relaciones sociales y de poder.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was guided and influenced by several people, including JeanneArnold, Wendy Ashmore, Jim Hill, Cecelia Klein, Paul Kroskrity, RichardLeventhal, Joyce Marcus, and Karl Taube. Wendy Ashmore, Virginia Fields,Rex Koontz, and two anonymous reviewers graciously provided com-

ments. The project was funded by the National Science Foundation, theFriends of Archaeology, and the University of California, Los Angeles. Ithank those who allowed the use of their maps and drawings. The ideaspresented and any possible errors are the responsibility of the author.

REFERENCES

Abercrombie, Nicholas, and Bryan S. Turner1982 The Dominant Ideology Thesis. In Classes, Power, and Con-

flict: Classical and Contemporary Debates, edited by Anthony Gid-dens and David Held, pp. 396– 416. University of California Press,Berkeley.

Abercrombie, Nicholas, Stephen Hill, and Bryan S. Turner1982 The Dominant Ideology Thesis. George Allen and Unwin, Boston.

Agurcia Fasquelle, Ricardo1996 Rosalila, el corazón de la Acrópolis: El Templo del Rey-Sol.

Yaxkin 14:5–18.Andrews, George F.

1975 Maya Cities: Placemaking and Urbanization. University of Okla-homa Press, Norman.

1995 Pyramids and Palaces, Monsters and Masks: The Golden Age ofMaya Architecture. Labyrithos, Lancaster, CA.

Ashmore, Wendy1989 Construction and Cosmology: Politics and Ideology in Lowland

Maya Settlement Patterns. In Word and Image in Maya Culture: Ex-plorations in Language, Writing, and Representation, edited by Wil-

liam F. Hanks and Don S. Rice, pp. 272–286. University of UtahPress, Salt Lake City.

Fairclough, Graham.1992 Meaningful Constructions—Spatial and Functional Analysis of

Medieval Buildings. Antiquity 66:348–366.Fash, William L.

1991 Scribes, Warriors and Kings: The City of Copán and the AncientMaya. Thames and Hudson, New York.

Fash, William L., Richard V. Williamson, Carlos Rudy Larios, and JoelPalka

1992 The Hieroglyphic Stairway and Its Ancestors: Investigations ofCopan Structure 10L-26. Ancient Mesoamerica 3:105–115.

Foster, Sally M.1989 Analysis of Spatial Patterns in Buildings (Access Analysis) as

an Insight into Social Structure: Examples from the Scottish AtlanticIron Age. Antiquity 63:40–50.

Graham, Ian1979 Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Vol. 3, Part 2, Yax-

chilan. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, HarvardUniversity, Cambridge, MA.

274 Sanchez

Graham, Ian, and Eric Von Euw1977 Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Vol. 3, Part 1, Yax-

chilan. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, HarvardUniversity, Cambridge, MA.

Griffin, Gillett G.1978 Cresterias of Palenque. In Tercera Mesa Redonda de Palenque,

edited by Merle Greene Robertson and Donnan Call Jeffers, pp. 139–146. Pre-Columbian Art Research, Monterey, CA.

Grube, Nikoai, and Linda Schele1990 A New Interpretation of the Temple 18 Jambs. Copán Mosaics

Project, Copán Note 85. Austin, TX.Hendon, Julia A.

1992 Architectural Symbols of the Maya Social Order: ResidentialConstruction and Decoration in the Copan Valley, Honduras. In An-cient Images, Ancient Thought: The Archaeology of Ideology, Pro-ceedings of the 23rd Annual Chacmool Conference, edited by A.Sean Goldsmith, Sandra Garvie, David Selin, and Jeannette Smith,pp. 481– 495. Chacmool, Archaeological Association of the Univer-sity of Calgary.

Hohmann, Hasso, and Annegrete Vogrin1982 Die Architektur von Copan (Honduras). Akademische Druck-

und Verlagsanstalt, Graz, Austria.Houston, Stephen D.

1994 Literacy among the Pre-Columbian Maya: A Comparative Per-spective. In Writing without Words: Alternative Literacies in Meso-america and the Andes, edited by Elizabeth Hill Boone and Walter D.Mignolo, pp. 27– 49. Duke University Press, Durham, NC.

1998 Classic Maya Depictions of the Built Environment. In Functionand Meaning in Classic Maya Architecture, edited by Stephen D.Houston, pp. 333–372. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, DC.

Hymes, Dell1986 Models of the Interaction of Language and Social Life. In Di-

rections in Sociolinguistics: The Ethnography of Communication, ed-ited by John J. Gumperz and Dell Hymes, pp. 35–71. Basil Blackwell,Oxford.

Johnston, Kevin J.2001 Broken Fingers: Classic Maya Scribe Capture and Polity Con-

solidation. Antiquity 75(288):373–381.Jones, Christopher, and Linton Satterthwaite

1982 The Monuments and Inscriptions of Tikal: The Carved Monu-ments. Tikal Report No. 33, Part A. University Museum, Universityof Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Looper, Matthew G.1995 The Sculpture Programs of Butz’-Tiliw, An Eighth Century Maya

King of Quiriguá, Guatemala. Ph.D. dissertation, Art History, Uni-versity of Texas, Austin.

1999 New Perspectives on the Late Classic Political History of Qui-rigua, Guatemala. Ancient Mesoamerica 10:263–280.

Love, Bruce1983 Mayan Epigraphy and the Ethnography of Writing. Unpublished

manuscript.Marcus, Joyce

1974 The Iconography of Power among the Classic Maya. World Ar-chaeology 6(1):83–94.

1976 Emblem and State in the Classic Maya Lowlands: An Epi-graphic Approach to Territorial Organization. Dumbarton Oaks, Wash-ington, DC.

1992 Mesoamerican Writing Systems: Propaganda, Myth, and His-tory in Four Ancient Civilizations. Princeton University Press, Prince-ton, NJ.

McAnany, Patricia A.1995 Living with the Ancestors: Kinship and Kingship in Ancient Maya

Society. University of Texas Press, Austin.1998 Ancestors and the Classic Maya Built Environment. In Function

and Meaning in Classic Maya Architecture, edited by Stephen D.Houston, pp. 271–298. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, DC.

Miller, Arthur G.1986 Maya Rulers of Time: A Study of Architectural Sculpture at Ti-

kal, Guatemala. University Museum, University of Pennsylvania,Philadelphia.

Miller, Mary Ellen1986a Copan, Honduras: Conference with a Perished City. In City-

States of the Maya: Art and Architecture, edited by Elizabeth P. Ben-son, pp. 72–109. Rocky Mountain Institute for Pre-Columbian Studies,Denver.

1986b The Murals of Bonampak. Princeton University Press, Prince-ton, NJ.

Moore, Jerry D.1992 Pattern and Meaning in Prehistoric Peruvian Architecture: The

Architecture of Social Control in the Chimu State. Latin AmericanAntiquity 3(2):95–113.

Morales, Alfonso, Julie Miller, and Linda Schele1990 The Dedication Stair of “Ante” Temple. Copán Mosaics Project,

Copán Note 76. Austin, Texas.Nuttall, Zelia

1900 The Fundamental Principles of Old and New World Civiliza-tions: A Comparative Research Based on a Study of the Ancient Mex-ican Religious, Sociological and Calendrical Systems. Papers of thePeabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Harvard Univer-sity, Cambridge, MA.

Proskouriakoff, Tatiana1960 Historical Implications of a Pattern of Dates at Piedras Negras,

Guatemala. American Antiquity 25(4):454– 475.1973 The Hand-Grasping Fish and Associated Glyphs on Classic Maya

Monuments. In Mesoamerican Writing Systems, edited by ElizabethP. Benson, pp. 165–178. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, DC.

Robin, Cynthia2001 Kin and Gender in Classic Maya Society: A Case Study from

Yaxchilán, Mexico. In New Directions in Anthropological Kinship,edited by Linda Stone, pp. 204–228. Rowman and Littlefield, NewYork.

Sanchez, Julia L.J.1997 Royal Strategies and Audience: An Analysis of Classic Maya

Monumental Art. Ph.D. dissertation, Anthropology, University of Cal-ifornia, Los Angeles.

Schele, Linda, and David A. Freidel1990 A Forest of Kings. Quill, New York.

Schele, Linda, and Mary Ellen Miller1986 The Blood of Kings. Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX.

Schele, Linda, and Alfonso Morales1990 Some Thoughts on Two Jade Pendants from the Termination

Cache of “Ante” Structure at Copán. Copán Mosaics Project, CopánNote 79. Austin, Texas.

Schele, Linda, and David Stuart1986 Moon-Jaguar, the 10th Successor of the Lineage of Yax-K’uk’-

Mo’ of Copán. Copán Mosaics Project, Copán Note 15. Austin, Texas.Sharer, Robert J., William L. Fash, David W. Sedat, Loa P. Traxler, andRichard Williamson

1999 Continuities and Contrasts in Early Classic Architecture of Cen-tral Copan. In Mesoamerican Architecture as a Cultural Symbol, ed-ited by Jeff Karl Kowalski, pp. 220–249. Oxford University Press,New York.

Sharer, Robert J., Loa P. Traxler, David W. Sedat, Ellen E. Bell, MarcelloA. Canuto, and Christopher Powell

1999 Early Classic Architecture beneath the Copan Acropolis. An-cient Mesoamerica 10:3–23.

Stuart, David1987 Ten Phonetic Syllables. Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writ-

ing 14. Center for Maya Research, Washington, DC.Tate, Carolyn

1992 Yaxchilan, the Design of a Maya Ceremonial City. University ofTexas Press, Austin.

Whitley, David S.1994 Ethnography and Rock Art in the Far West: Some Archaeologi-

cal Implications. In New Light on Old Art: Recent Advances in Hunter-Gatherer Rock Art Research, edited by David S. Whitley and LawrenceL. Loendorf, pp. 81–93. Institute of Archaeology, Monograph 36.University of California, Los Angeles.

Creating power and identity through art 275