Marsilio Ficino's 'Si Deus Fiat Homo' and Augustine's 'Non Ibi Legi': The Incarnation and Plato's...

Transcript of Marsilio Ficino's 'Si Deus Fiat Homo' and Augustine's 'Non Ibi Legi': The Incarnation and Plato's...

* I am grateful for having discussed various aspectsof this paper with M. J. B. Allen, C. Celenza, G.Giglioni, J. Kraye, F. Pagani, P. Podolak, as well as to the audience at the Director’s Work-in-ProgressSeminar at the Warburg Institute, where I presentedsome of this material in !"#!, this Journal’s anonymousreviewers for their generous comments on a previousdraft of this study, and its editors for their helpfulsuggestions.

All translations are mine unless otherwise indi-cated.

#. See J. Pépin, ‘Ex Platonicorum persona’. Étudessur les lectures de saint Augustin, Amsterdam #$%%.Prosopopoeia was also an exegetical technique used

by patristic commentators to the Gospels and espe-cially to the Psalms, where the exegete was concernedto identify who was speaking to whom about whom,identifying the moments when the Psalms werepronounced in persona Christi. See C. Andresen, ‘ZurEntstehung und Geschichte des trinitarischen Person-begri&es’, Zeitschrift für die Neutestamentliche Wissen-schaft und die Kunde der alteren Kirche, '((, #$)#, pp.#–*$; and M.-J. Rondeau, Les commentaires patristiquesdu Psautier (IIIe-Ve siècles), ((, Exégèse prosopologique etthéologique (Orientalia Christiana Analecta, ++,,),Rome #$-..

!. A small sample of the vast literature on thetopic: P.-H. Hadot, Porphyre et Victorinus, ! vols, Paris

-%

JOURNAL OF THE WARBURG AND COURTAULD INSTITUTES, LXXVII, !"#/

MARSILIO FICINO’S ‘SI DEUS FIAT HOMO’ AND AUGUSTINE’S ‘NON IBI LEGI’: THE INCARNATION

AND PLATO’S PERSONA IN THE SCHOLIA TO THE LAWS*

Denis J.-J. Robichaud

… sed quia verbum caro factum est et habitavit in nobis, non ibi legi. (Augustine, Confessions, 0((.$.#/)

121 (3( '45(

Book 0((.$ of Augustine’s Confessions contains a well-known comparison betweenthe Gospel of John and the ‘books of the Platonists’. Situated in the middle of

the Confessions, the passage functions as a central pivot in Augustine’s conversion,indicating the Platonic turn away from his past life towards a new Christian one.Yet Augustine’s message in chapter $ is that although the Platonicorum libri serveas an initial protreptic reorientation, they do not enable us to reach the intendedfatherland. Quoting not the Platonists themselves but John’s ‘in principio eratverbum’, Augustine tells us that in these works he read (‘ibi legi’) the reasons foundin the opening of John’s Gospel. His prosopopoeic rhetorical device, in e&ect, estab-lishes the comparison between the Johannine and the Platonic logos by express ingthe Scriptures ex Platonicorum persona.# Nevertheless, the similarities end with theIncarnation. Its absence is noted in the rhetorical comparison by Augustine’s reduplicative use of ‘non ibi legi’ (0((.$.#*, #/), the similar ‘non habent illi libri’ and ‘non est ibi’, as well as the statement that the Platonists lack humility sincethey are deaf (‘non audiunt’, 0((.$.#/) to Christ’s teachings—all of which stronglyemphasise the essential doctrinal di&erence that the Platonicorum libri do notmention the Incarnation.

Confessions 0((.$ has long been studied and debated by eminent scholars seekingto measure the debt of Augustine’s theology to Neoplatonism, to study the placeof his Platonic readings in his conversion and to identify the exact books includedamong the Platonicorum libri.!The Platonic preoccupations inherited by modern

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 87

scholars and theologians from the Church Fathers are also crucial for MarsilioFicino, the fifteenth-century humanist and philosopher whose scholarly laboursproduced the first full Latin translation (along with commentaries) of Plato, Plotinusand numerous Neoplatonists. Ficino addresses the question of Augustine’s Plato-nicorum libri directly in a letter of #/$/ to Jacopo Rondono, Bishop of Rimini, inwhich he expresses the opinion that many Platonists who lived after Christ adoptedTrinitarian formulations from the Gospel of John: ‘For this reason, AureliusAugustine, formerly a Platonist and now deliberating about his profession of theChristian faith, says that when he encountered our books of the Platonists andidentified Christian dogmas sanctioned by them through imitation, he gave thanksto God and was at once restored, better disposed to accept Christian dogmas.’* Heclarifies his statement with care, di&erentiating the books of the Platonists fromPlato’s corpus of dialogues: ‘I therefore assert beyond dispute that the secret of theChristian Trinity is never in the books of Plato himself, but a few things are indeedsomehow similar in words, though not in sense.’/ Discussing the books of Platoand the Platonists, and Augustine’s reading of them, Ficino tells his correspon-dent that the Platonists imitate Christian ideas and that while a few of Plato’sTrinitarian expressions resemble Christianity, they are not identical. If, however,Ficino’s dogmatic orthodoxy remains safely protected in this explanation to BishopRondono, one finds that matters are not always so clear.

Edgar Wind and Michael J. B. Allen have noted how Ficino astutely observesthe similarity between certain Neoplatonic doctrines and Arian formulations of theTrinity; and Allen makes a convincing case that Ficino often used Augustine as aguide for an un-Augustinian programme to ‘accommodate the Neoplatonists andabove all the sublime Plotinus to Christianity’.. In this article I propose to study

-- FICINO, PLATO’S PERSONA AND THE INCARNATION

#$)-; Pépin (as in n. #); P. Courcelle, Recherches sur les ‘Confessions’ de Saint Augustin, Paris #$."; idem,‘Litiges sur la lecture des ‘Libri Platonicorum’ parsaint Augustin’, Augustiniana, (0, #$./, pp. !!.–*$; G. Madec, ‘Le néoplatonisme dans la conversiond’Augustin: État d’une question centenaire (depuisHarnack et Boissier, #$--)’, in Internationales Sympo-sium über den Stand der Augustinus-Forschung, ed. C.Mayer and K. H. Chelius, Würzburg #$-$; idem, SaintAugustin et la philosophie, notes critiques, Paris #$$);idem, Saint Augustin et la Philosophie, notes critiques,Paris #$$); A. Solignac, ‘Doxographies et manuelsdans la formation philosophique de saint Augustin’,Recherches augustiniennes, (, #$.-, pp. ##*–/-; idem,‘Introduction’ and ‘Notes complémentaires’, in StAugustine, Les Confessions, Paris #$)!, esp. pp. ..–##*, #/.–.!, #)#–)*, !.)–.%, )%$–%"*; O. du Roy, L’intelligence de la foi en la Trinité selon saint Augustin,Paris #$)), pp. )-–%"; P. F. Beatrice, ‘Quosdam Plato -nicorum libros. The Platonic Readings of Augustine in Milan’, Vigiliae christianae, ,'(((, #$-$, !."–.!; P.Henry, Plotin et l’Occident, Louvain #$*/.

*. Marsilio Ficino, Opera omnia, ! vols, Basel #.%)(facs. repr. with introduction by S. Toussaint, Paris!""") [hereafter: Ficino, Opera], (, p. $.): ‘Quamobrem

Aurelius Augustinus quondam Platonicus et iam deChristiana professione deliberans, cum in nos Plato-nicorum libros incidisset, cognovissetque Christianaper imitationem ab his probata, Deo gratias egit, red -ditusque iam est ad Christiana recipienda propensior.’On this letter see also M. J. B. Allen, Synoptic Art,Florence #$$-, p. %/; idem, ‘Marsilio Ficino on Plato,the Neoplatonists and the Christian Doctrine of theTrinity, Renaissance Quarterly, ,,,0((, #$-/, pp. ...–-/ (the full letter is on pp. ...–.)), now in idem,Plato’s Third Eye: Studies in Marsilio Ficino’s Meta-physics and its Sources, Aldershot #$$.; A. della Torre,Storia dell’Acca demia Platonica di Firenze, Florence#$"!, p. .$!.

/. Ficino, Opera, (, p. $.): ‘Ego igitur extra contro- versiam assero trinitatis Christianae secretum in ipsisPlatonis libris nunquam esse, sed nonnulla verbisquidem quamvis non sensu quoquomodo similia.’

.. E. Wind, Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance,London #$)-, pp. !/#–..; Allen, ‘Ficino on Plato’ (asin n. *); idem, Synoptic Art (as in n. *), p. $". Moregenerally on Ficino and Augustine see Allen, Synop-tic Art, the first two chapters; and P. O. Kristeller,‘Augustine and the Early Renaissance’, in his Studiesin Renaissance Thought and Letters, (, Rome #$-/, pp.

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 88

DENIS J.-J. ROBICHAUD -$

how Ficino, in translating Plato’s Laws, wrestles with the philological and exegeticalpossibilities of unearthing ‘a few things … somehow similar in words’ to the mostprofound of all Christian doctrines, the Incarnation, from Plato’s speech in hisown persona. Manuscript and textual evidence show that Ficino’s discovery of the Incarnation in the Greek variants of the scholia to the Platonic corpus is farfrom conjectural guesswork; indeed, it remains one of his strongest attempts at arapprochement between Christianity and Platonism.) If Augustine’s Platonicorumlibri —works by philosophers who lived after the advent of Christ—do not containthe Incarnation, then its discovery in Plato’s works, Ficino judges, transforms thePlatonic corpus into a sacred text of sorts.

(1 6478219 6'9:21(8

For Ficino, the identification of the dogma of the Incarnation—the via of Christ—in the Platonic corpus is closely tied to his search for a way out of the aporeticimpasse of Platonic exegesis. In order for Ficino to locate Christian dogmas inPlato’s teachings, he must first explain how and when (if at all) Plato o&ers his ownexplicit doctrines in the dialogues. In so doing, he is responding to the perennialPlatonic question: among all the interlocutors in the dialogues, behind which maskdoes Plato’s face peer out?

How one answers the Platonic question may determine whether one interpretsthe Platonic corpus as aporetic or dogmatic. Plato mentions his name only twicein the dialogues and never as the voice of the author nor as a speaking character.%

The problem is underscored by Socrates’s ironic refusal to put forward his ownpositive doctrines but his willingness to convey those of others (for instance, negatively as Protagoras in the Theaetetus, and positively as Diotima in the Sym-posium). Alcibiades at the end of the Symposium gives a lifelike representation ofSocratic irony when he compares Socrates to Silenus, whose outer hybrid grotesque

*)-–%#; M. Heitzman, ‘L’agostinismo avicennizzantee il punto di partenza della filosofia di Marsilio Ficino’,Giornale critico della filosofia italiana, ,0(, #$*., pp.!$.–*!!; /)"–-"; E. Garin, ‘S. Agostino e MarsilioFicino’, Bollettino storico agostiniano, ,0(, #$/", pp. /#–/%; A. Tarabochia Canavero, ‘Agostino e Tommaso nelcommento di Marsilio Ficino all’Epistola ai Romani’,Rivista di filosofia neo-scolastica, ',0, #$%*, pp. -#.–!/; eadem, ‘S. Agostino nella ‘Teologia Platonica’ diMarsilio Ficino, Rivista di filosofia neo-scolastica, ',,,#$%-, pp. )!)–/).

). More generally, Ficino’s use of Platonic scholiahas been all but ignored. An exception is M. J. B. Allen,Icastes Marsilio Ficino’s Interpretation of Plato’s Sophist,Berkeley #$-$, pp. $"–$.. Many of the scholia fromthe Laws dealing with historical and lexical questionsare completely ignored by Ficino in his Epitomes,though they are at times taken into account in histranslations. Indeed, beyond the examples discussedin the present article, in his Epitomes Ficino only drawson the scholia explicitly on one more occasion, for

material about Diana and hermae at Laws $#/b; seeOpera, ((, p. #.!!. He states explicitly, however, thathis argumenta are not commentaries, which wouldpresumably include more of the historical and lexicalmaterial found in the scholia; ibid. p. #/$".

%. For the topic see Who Speaks for Plato? Studiesin Platonic Anonymity, ed. G. Press, New York !""";P. Merlan, ‘Form and Content in Plato’s Philosophy’,Journal of the History of Ideas, 0(((, #$/%, pp. /")–*"; L. Edelstein, ‘Platonic Anonymity’, American Journalof Philology, ',,,(((, #$)!, pp. #–!!; P. Plass, ‘PlatonicAnonymity and Irony in the Platonic Dialogues’, ibid., ',,,0, #$)/, pp. !./–%-; idem, ‘Play and Philo-sophical Detachment in Plato’, Transactions of theAmerican Philo logical Association, ,+0(((, #$)%, pp. */*–)/; L. A. Kosman, ‘Silence and Imitation in thePlatonic Dialogues’, in Methods of Interpreting Platoand His Dialogues, ed. J. C. Klagge and N. D. Smith,Oxford #$$!; E. N. Tigerstedt, Interpreting Plato,Stockholm #$%%, pp. $!–$/.

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 89

$" FICINO, PLATO’S PERSONA AND THE INCARNATION

face or mask (!"#$%!&') hides both an inner divinity and complex philosophicalproblems.- Socrates stands out since it is often taken for granted that he is Plato’smouthpiece; yet not all attentive readers of the dialogues have thought this soobvious. For instance, there are two dialogues, the Laws and the Epinomis (if thelatter is accepted as a genuine work of Plato), where Socrates is not even an inter-locutor.

The third-century biographer and doxographer Diogenes Laertius records inhis Life of Plato that the ancients were aware of these exegetical di;culties:

But since there is much debate, with some asserting that Plato dogmatised and othersasserting that he did not, we now ought to make a distinction about this matter … Therefore,concerning that on which he has firm conviction, Plato reveals his position and refutes falsehoods; but concerning unclear matters he suspends his judgement. And concerning hisown opinions he reveals his position through four characters (!"#$%!(): Socrates, Timaeus,the Athenian Stranger and the Eleatic Stranger. These Strangers are not, as some assumed,Plato and Parmenides, but are anonymous figures (!)*$µ(+* ,$+-' .'/'0µ(). And whenSocrates and Timaeus speak, Plato is dogmatising. But when he refutes falsehoods, he introduces characters such as Thrasymachus, Callicles, Polos, Gorgias and Protagoras, aswell as Hippias, Euthydemus and others of this type.$

Diogenes Laertius here distinguishes between an aporetic and dogmatic interpre -tation of Plato. His solution to the polemical interpretive discord is to allow forboth, by way of prosopopoeia, that is, by introducing dramatic characters or masks.Only through the interlocutors of Socrates, Timaeus, the Athenian Stranger andthe Eleatic Stranger does Plato give positive doctrines. Likewise, through othercharacters, Plato gives negative doctrines and falsehoods. The reader is left tosuppose that all other arguments voiced by unnamed characters engage with probability, possibility and verisimilitude. Socrates, as noted above, is an obviouschoice as Plato’s mouthpiece. It is also not surprising to find Timaeus included inDiogenes Laertius’s list, since he is not so much an interlocutor in the dialoguewhich bears his name as a lecturer who delivers a long, uninterrupted monologuewhile his listeners sit in Pythagorean silence. Timaeus’s speech could, in fact, beconsidered as a suspension of the dialogue form, which is intrinsic to the aporeticinterpretation of Plato. It is also very likely that Diogenes Laertius includes Timaeusand the Eleatic Stranger in his list of Plato’s dramatic spokespersons because theyrepresent two of the major philosophies studied by Plato: Timaeus stands in forthe Pythagoreans and the Eleatic Stranger, unsurprisingly, for the Eleatic school.

-. See, e.g., P. Hadot, ‘La figure de Socrate’, inhis Exercices spirituels et philosophie antique, Paris !""!,pp. #"#–/#. 1"#$%!&', meaning face or mask, is a richword and concept which is also used in Greek manu-scripts to designate characters in plays and interlocu-tors in dialogues.

$. Diogenes Laertius, Vitae philosophorum, ed. M.Marcovich, (, Stuttgart and Leipzig #$$$, (((..#–.!:2!34 56 !&))7 $+*$-8 ,$+4 9(4 &: µ;' <($-' (=+>'5&?µ(+@A3-', &: 5’&B, <;"3 9(4 !3"4 +&C+&0 5-()*D%µ3'…E +&@'0' 1)*+%' !3"4 µ6' F' 9(+3@)G<3' .!&<(@'3+(-,

+H 56 I305J 5-3);?K3-, !3"4 56 +L' .5M)%' ,!;K3-. N(4!3"4 µ6' +L' (=+O 5&9&C'+%' .!&<(@'3+(- 5-H +3++*"%'!"&$/!%', P%9"*+&08, Q-µ(@&0, +&R STG'(@&0 U;'&0,+&R 2)3*+&0 U;'&0· 3V$4 5’&: U;'&- &=K, W8 +-'38 X!;)(D&',1)*+%' 9(4 1("µ3'@5G8, .))H !)*$µ(+* ,$+-' .'/'0µ(·,!34 9(4 +H P%9"*+&08 9(4 +H Q-µ(@&0 );?%' 1)*+%'5&?µ(+@A3-. 13"4 56 +L' I305L' ,)3?K&µ;'&08 3V$*?3-&Y&' Z"($Cµ(K&' 9(4 N())-9);( 9(4 1L)&' [&"?@(' +39(4 1"%+(?#"(', \+’ +’ ]!!@(' 9(4 ^=TC5Gµ&' 9(4 57 9(4+&_8 `µ&@&08.

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 90

The Athenian Stranger from the Laws, however, establishes the parameters forthe aporetic understanding of the dramatic personae of the dialogues. If Socratescan be considered one pole of the Platonic question, the Athenian Stranger can be seen as the other, since Diogenes Laertius tells us that some commentatorserroneously equate the anonymous Stranger with Plato himself. Who, then, is theanonymous Stranger? Identified only as U;'&8, he is without a name and, beingoutside of his polis in Crete, without a law. Unlike Homeric guests who eventuallyreveal their identity to their hosts, the anonymous Stranger never divulges himself.

Quintilian confirms the use among both Greeks and Latins of prosopopoeiato understand the dialogue form and the Platonic question. In explicating theconcept in his Institutio oratoria, he associates the figure of thought with inventio:

There are some authorities who restrict the term !"&$%!&!&-@( to cases where both personsand words are fictitious, and prefer to call the imaginary conversations between men by theGreek name 5-*)&?&-, which some translate by the Latin sermocinatio. For my own part, I haveincluded both under the same generally accepted term, since we cannot imagine a speechunless we also imagine a person to utter it.#"

If all speeches must belong to specific persons, as Quintilian says, and if all speecheshave fathers, as Plato says at the end of the Phaedrus, then to which character mask(persona or !"#$%!&') do the speeches of the anonymous Athenian Stranger in theLaws belong? Ficino’s answer is deceptively simple: Plato himself. Yet the identi-fication of Plato’s !"#$%!&', Ficino reasons, will reveal Plato’s docrines. On whatgrounds does he make this identification?

Ficino certainly read Diogenes Laertius both in Greek and in the Latin translation by Ambrogio Traversari, yet in his own Life of Plato, he dissents fromDiogenes’s judgement in identifying the anonymous Stranger as Plato. Follow-ing Quintilian’s categorisation of Plato’s dialogues as either elenctic (an aporeticdialogue which refutes sophists and/or encourages youths) or dogmatic (a dialoguewhich primarily instructs adults), Ficino writes:

What Plato said in his own voice in the Letters, Laws and Epinomis, he desires to be held asabsolutely certain; but what he argues in the other books in the mouth (os) of Socrates,Timaeus, Parmenides and Zeno, he wants to be held as having the appearance of the truth(verisimilia).##

Ficino here shows his awareness of the dialogic and prosopopoeic nature of Plato’sworks by acknowledging that Plato puts arguments in various mouths. He uses the

#". Quintilian, Institutio oratoria, ed. and tr. H. E.Butler, / vols, New York #$!!, (((, pp. *$"–$* ((,.!.*#–*!): ‘Ac sunt quidam, qui has demum !"&$%!&!&-a(8dicant, in quibus et corpora et verba fingimus;sermones hominum adsimulatos dicere 5-()#?&08malunt, quod Latinorum quidam dixerunt sermoci-nationem. Ego iam recepto more utrumque eodemmodo appelavi: nam certe sermo fingi non potest utnon personae sermo fingatur.’ I have slightly modifiedthe translation. Among Greek rhetorical works a not -able source on prosopopoeia is (Pseudo-)Demetrius

of Phalerum, On Style, ed. W. Roberts, Cambridge#$"!, p. #--.##. Ficino, Opera, (, p. %)): ‘Quae in epistolis vel

in libris de legibus et Epinomide Plato ipse suo dixitore certissima vult haberi, quae vero in caeteris librisSocratis, Timaei, Parmenidis, Zenonis ore disputat,verisimilia.’ On the division of the dialogues into theelenctic and dogmatic see Quintilian, ((.#..!). OnFicino’s Life of Plato see D. J.-J. Robichaud, ‘MarsilioFicino’s De vita platonis’, Accademia, 0(((, !""), pp.!*–.$, and the literature cited there.

DENIS J.-J. ROBICHAUD $#

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 91

Latin os (mouth / face / speech) in a manner more or less equivalent to the Greek!"#$%!&' (mask / face), recalling the old (and likely erroneous) Latin auditoryetymology for persona as something through which a voice resounds (personare).#!

Ficino, like Diogenes Laertius, also distinguishes the Socratic from the Timaeanand the Eleatic schools of philosophy (the latter two being, for him, essentiallyPythagorean). All are cast aside as presenting arguments based on verisimilitudeand not on truth itself. In this regard, Ficino is following Augustine, who, in hisContra Academicos, argues against the scepticism of the New Academy, via Cicero’sAcademica, and draws a sharp division between truth and verisimilitude: between,on the one hand, a hidden esoteric doctrinal and dogmatic Plato concerned withtruth, and on the other, a false exoteric sceptical and aporetic Platonism concernedwith verisimilitude and probability. Although his interpretation of Plato is oftenesoteric, Ficino is going beyond Augustinian demarcations by looking for explicitdoctrines and dogmas.#*

He lists three works where Plato speaks in his own voice: the Letters, which, as such, are not supposed to have been written in a dramatic manner; the Laws;and the Epinomis, a companion to the Laws.#/The Laws, divided into twelve lengthybooks, has long been considered Plato’s final composition. Its dramatic setting isthe island of Crete, where three old men, Clinias the Cretan, Megillus the Spartanand the Athenian Stranger converse during their walk from the city of Cnosus toZeus’s temple and grotto on Mount Ida, where they are headed in order to consultthe god about establishing laws for a new Cretan colony. The dialogic and dramatic

$! FICINO, PLATO’S PERSONA AND THE INCARNATION

#!. See also the example cited below, n. -*; andAulus Gellius, Noctes Atticae, 0.%; Boethius, De duabusnaturis et una persona Jesu Christi, contra Eutychen etNestorium, ed. J. P. Migne, Patrologia latina, ',(0, Paris#-/%, cols #*/*–//.#*. It should be noted that in other works, e.g., De

civitate dei, Augustine is more forthcoming in recognis -ing explicit Platonic doctrines. On the history of theesoteric interpretation of Plato see E. N. Tigerstedt,The Decline and Fall of the Neoplatonic Interpretation of Plato, Helsinki #$%/. I would add two minor reser-vations to this important work and to Tigerstedt, Interpreting Plato (as in n. %). Firstly, Tigerstedt perhapsmakes Neoplatonism as a whole too systematicallyconsistent. Secondly, he praises Luigi Stefanini for hisattempt to solve the sceptico-aporetic and dogmaticdichotomy in the interpretation of Plato by proposingthe concept of verisimilitude as opposed to the prob-abilism of the New Academy. Although Tigerstedt hasdoubts about Stefanini’s Christian interpretation ofPlato, he does not seem to acknowledge directly thatthe very concept of verisimilitude is used by Augustinein his interpretation of Platonism and in other writingsof his such as the Soliloquies. As we see in the previouslyquoted passage from Ficino, the concept of verisimili-tude for the interpretation of Plato also had a historybeyond Stefanini and Augustine.#/. On Ficino and the Epinomis see M. J. B. Allen,

‘Ratio omnium divinissima: Plato’s Epinomis, Prophecy,

and Marsilio Ficino’, in Epinomide. Studi sull’opera e lasua ricezione, ed. F. Alesse, F. Ferrari and M. C. Dalfino,Naples !"#!, pp. /)$–$". On Ficino and Plato’s Letterssee idem, ‘Sending Archedemus: Ficino, Plato’s SecondLetter, and its Four Epistolary Myster ies’, in Sol etHomo: Mensch und Natur in der Renaissance. Festschriftzum !". Geburtstag für Eckhard Kessler, ed. S. Ebbers -meyer, H. Pirner-Pareschi and T. Ricklin, Munich!""-, pp. /".–!"; and Wind (as in n. .), pp. !–*, *%–/#, !/*–//. This account of Ficino’s exegesis of Plato’sLaws is also confirmed in book ,0(( of his PlatonicTheology, where he claims that it is in the Laws where‘ipsa Platonis persona loquitur’; Ficino, PlatonicTheology, ed. J. Hankins, tr. M. J. B. Allen, ) vols,Cambridge, MA !""#–"), 0(, pp. .", .! (,0((./.. and)). The most thorough study of book ,0(( and the sixacademies is Allen, Synoptic Art (as in n. *), pp. .#–$!;see also C. S. Celenza, ‘Pythagoras in the Renaissance:The Case of Marsilio Ficino’, Renaissance Quarterly,'((, #$$$, pp. )-.–$#. On Ficino and Plato’s Laws seealso A. Neschke-Hentschke, ‘Hierusalem caelestis proviribus in terris expressa. Die Auslegung der platonis-chen Staatsentwürfe durch Marsilius Ficinus und ihre“hermeneutischen” Grundlagen’, Würzburger Jahr -bücher für die Altertumswissenschaft, ,,(((, #$$$, pp.!!*–/*; eadem, ‘Marsile Ficin lecteur des lois’, Revuephilosophique de la France et de l’Étranger, +,+, no. #[=Les Lois de Platon], !""", pp. -*–#"!.

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 92

elements of the work are somewhat limited when compared to other Platonicdialogues, and the lion’s share of the discourse is given to the Athenian Stranger,who expatiates in quasi-monologues on various philosophical topics as well asactual laws. Ficino gives a privileged position to the Laws by placing it last (withthe Epinomis and the Letters) in his ordering of the dialogues—a position which isalso attested in Thrasyllus’s tetralogies, but whose organisational schema Ficinodoes not otherwise follow.#.

Again following Augustine, Ficino begins his commentary or Epitome on Plato’sLaws by dividing philosophy into the contemplative approach of the Pythagoreans,the moral and active philosophy of Socrates, and the combination of both, whichis the philosophy of Plato:

To what end is all this? So that we remember that since the arrangement of the present Lawsis told to us by Plato himself—neither through a Pythagorean persona nor through Socrates,as is often the case with other matters, but, on the contrary, through the very persona of Platohimself—we justifiably obtain a middle way (via) between divine and human things, so thatwe are neither dragged through certain hidden or impassable ways (invia), nor still pulleddown to the realms below to more remote things. On account of this, the ten books of theRepublic are judged to be more Pythagorean and Socratic, whereas the present Laws aremore Platonic.#)

As Allen rightly points out, Ficino is also following Apuleius’s account, in De Platoneet eius dogmate, of Plato’s education in two disciplinary branches of philosophy: thenatural philosophy of the Pythagoreans and the dialectical method (both rationaland moral) of Socrates.#% It is only appropriate that Ficino draws on Apuleius’s

#.. Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana MSPlut. -.."$, a Greek manuscript of Plato used byFicino in which the dialogues are in the Thrasyllanorder. The Clitophon and Letter XIII, however, areathetised by Ficino as spurious. Of the other dialoguesindicated as spurious by Diogenes Laertius—theDemodocus, the Sisyphus, Eryxias, Axiochus, Alcyon, Deiusto and De virtute—Ficino translated only Axiochus,but attributed it to Xenocrates (probably on the auth -ority of Diogenes Laertius). On Ficino’s ordering ofthe Platonic corpus see also J. Hankins, Plato in theItalian Renaissance, ! vols, Leiden #$$", (, pp. *")–##. On MS Plut. -.."$ see A. M. Bandini, Cataloguscodicum Graecorum Bibliothecae Laurentianae, (((,Florence #%%", cols !.%–)); L. A. Post, The VaticanPlato and Its Relations, Middletown, CT #$*/, p. )); N.G. Wilson, ‘A List of Plato Manuscripts’, Scriptorium,,0(, #$)!, pp. *-)–$. (no. *.); R. S. Brumbaugh andR. Wells, The Plato Manuscripts. A New Index, NewHaven, CT #$)-, p. /"; A. Diller, ‘Notes on the Historyof Some Manuscripts of Plato’, in his Studies in GreekManuscript Tradition, Amsterdam #$-*, pp. !.#–.-(!.%); G. Boter, The Textual Traditon of Plato’s Republic,Leiden #$-$, pp. *)–*%; Supplementum Ficinianum, ed.P. O. Kristeller, ! vols, Florence #$*%, (, p. CXLVII;idem, ‘Marsilio Ficino as a Beginning Student ofPlato’, Scriptorium, ,,, #$)), pp. /#–./; R. Marcel,

Marsile Ficin, Paris #$.-, p. !./; M. Sicherl, ‘Neuen-deckte Handschriften von Marsilio Ficino undJohannes Reuchlin’, Scriptorium, ,0(, #$)!, pp. ."–)#;S. Gentile, ‘Note sui manoscritti greci di Platoneutilizati da Marsilio Ficino’, in Scritti in onore di EugenioGarin, Pisa #$-%, pp. .#–-/ (..); idem, with S. Niccoliand P. Viti, Marsilio Ficino e il ritorno di Platone,Florence #$-/, pp. !-–*# (no. !!). For the relationshipof this manuscript to the so-called Vatican Plato seealso below, n. ./.#). Ficino Opera, ((, p. #/--: ‘Quorsum haec?

Ut meminerimus praesentem legum dispositionem,quoniam ab ipso Platone, non per Pythagoricampersonam, vel Socratem, ut solent caetera, immo veroper propriam Platonis ipsius personam nobis traditur,non iniuria viam [Opera: vitam] quandam inter divinaet humana mediam obtinere, neque nos per abdita, et invia quaedam trahere, neque tamen ad interiora[=inferiora?] deducere. Quamobrem decem illi deRep[ublica] libri Pythagorici magis sint atqueSocratici: praesentes vero leges magis Platonicae iudi-centur.’ See Augustine, Contra Academicos, (((.#%.*%;idem, De civitate Dei, 0(((./.#%. M. J. B. Allen, ‘Marsilio Ficino on Plato’s

Pythagorean Eye’, Modern Language Notes, ,+0((, #$-!,pp. #%*–%., now also in idem, Plato’s Third Eye (as inn. *); see Apuleius, De Platone et eius dogmate, (.*.

DENIS J.-J. ROBICHAUD $*

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 93

work when commenting on the Laws, the dialogue which he believes holds Plato’sown doctrines.#- Christopher S. Celenza, who looks briefly at this passage too,makes an adroit observation: one of the principal reasons why Ficino judges theRepublic to be more Pythagorean than Platonic is that its arguments on communalproperty are in agreement with the Pythagorean akousma, or precept, that ‘amongfriends all things are held in common’—which is the closing phrase of the Phaedrus,whereas, as Ficino believes, in the Laws the opinion is repudiated. This is broadlyin agreement with Ficino’s strategy of protecting Plato by attributing certaindangerous opinions to a Pythagorean voice or !"#$%!&' in a dialogue—as when,significantly, he attributes the doctrine of metempsychosis to Pythagoras, especiallywhen dealing with the thorny issue of souls which are reborn into the bodies ofbeasts.#$

To these comments it should be added that Ficino is also in line with Numeniusof Apamea and with Proclus, in presenting his readers with a middle way betweenthe dogmatic Pythagorean and aporetic Socratic approaches towards philosophy;Platonic serio ludere is thus situated between serious dogmas and Socratic play.!"

It is not only Socratic philosophy which conveys verisimilitude for Ficino, but alsothe Pythagoreans, in that their exoteric works do not fully express their esotericdoctrines. Moreover, in saying that Plato presents a middle way between the two,Ficino uses a philosophical etymology, since the fundamental meaning of aporia(.!&"@() is an impassable way or invia, as Ficino says: that is, the absence of a via, or !#"&8. Indeed, arguing that he is going to avoid impassable and hiddenways, Ficino seeks a hermeneutically clear path into the Platonic corpus. In thisinterpretive middle way, he identifies the Athenian Stranger as Plato’s own personaand thus argues that one can find explicit dogmas in Plato’s dialogues.

No Neoplatonist explicitly identifies the Athenian Stranger as Plato. Thereare passages in which Neoplatonic commentators quote the ‘Athenian Stranger’;and there are other moments when they say something like ‘as Plato says …’ andthen quote a passage from the Athenian Stranger. In the latter instances, however,they are never addressing the Platonic question or the prosopopoeic nature of the

$/ FICINO, PLATO’S PERSONA AND THE INCARNATION

#-. Besides Apuleius’s De Platone et eius dogmate,Ficino could have drawn on two other importantsources to find dogmas in Plato’s Laws: Alcinous’sDidaskalikos and, perhaps most significantly, Euse-bius’s Praeparatio evangelica (see below, pp. #"-–#"). Itshould be noted, however, that none of these worksidentify the Athenian Stranger as Plato himself. Onthe Laws in Eusebius and its later tradition see É. desPlaces, ‘La tradition indirecte de Platon’, in his Étudesplatoniciennes #$%$–#$!$, Leiden #$-#, pp. #$$–!)$. OnEusebius and Platonism see idem, Eusèbe de Césaréecommentateur. Platonisme et Écriture Sainte, Paris #$-!.#$. Celenza (as in n. #/), pp. )-%–-$, esp. n. %#.

The Anonymous Prolegomena to Platonic Philosophy, ed.and tr. L. G. Westerink, Amsterdam #$)!, pp. /" and/., distinguishes between three Platonic states corre-sponding to the Letters, Laws and Republic. See also J.

Dillon, ‘The Neoplatonic Reception of Plato’s Laws’,in Plato’s Laws and Its Historical Significance, ed. F. L.Lisi, Sankt Augustin !""#, p. !//. On the tripartitedivision see also Alcinous, Didaskalikos, ch. */; for atranslation see Alcinous, The Handbook of Platonism,tr. J. Dillon, Oxford #$$*, pp. /)–/%; and Proclus, Inrempublicam, (.#.$–#", #%.!". On the division of Platonic philosophy into

serious Pythagorean dogmas and Socratic play seeNumenius, Fragments, ed. É. des Places, Paris #$%*,fr. !/; and Proclus, In Timaeum, #.%.#-–#.-./. OnPlatonic serio ludere in the Renaissance see M. J. B.Allen, ‘The Second Ficino-Pico Controversy: Par -menidean Poetry, Eristic, and the One’, in MarsilioFicino e il ritorno di Platone, studi e documenti, ed. G. C.Garfagnini, ! vols, Florence #$-), ((, pp. /#%–..; andWind (as in n. .), p. !*).

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 94

dialogues, but merely quoting a passage from the work.!#The Laws, left out of thecanon of dialogues to be studied as set down by Iamblichus, does not apparentlyfigure prominently in the Neoplatonic educational curriculum. The AnonymousProlegomena to Platonic Philosophy (unknown to Ficino) relates that Proclus alsocasts out the Laws (along with the Republic) from the educational canon. Proclus’sjudgement on the Epinomis is even more severe since he considered it to bespurious.!! In his commentary on the Republic (first known to Ficino only in #/$!),he describes the skopos or aim of the Laws in relation to the Republic in the followingmanner:

Therefore, through all this it is clear that the aim of the Republic is nothing other than guidance on the best polity, just as the aim of the Laws is guidance on the laws.!*

This is not to say that the Neoplatonists ignore the Laws and other works ofpolitical philosophy; the work of Dominic O’Meara has punctured that scholarlyassumption.!/ Moreover, Ficino and other readers of Proclus’s Platonic Theologyknow that he focuses on the Laws in order to understand how Plato expresses thefundamental theological dogma ‘that there are gods, that they have providenceover everything, that they do everything according to justice and that none of theirinferiors turn them away from this’. As Proclus continues: ‘It is quite clear toeveryone that, among all the dogmas in theology, these are the most primary principles.’!.

Nevertheless, the identification of the Athenian Stranger is a persistent problemin Platonic interpretation, which has vexed ancient as well as modern interpreters.!)

!#. I argue this point in relation to Proclus belowat n. *!.!!. For Proclus’s judgement on the Laws see

Anonymous Prolegomena (as in n. #$), !).$; and Dillon,‘Neoplatonic Reception’ (as in n. #$), p. !/*. On theEpinomis see Proclus, In rempublicam (((.#*/..–%; idem,De providentia, '.##–/; Anonymous Prolegomena, !..#–#". Other doubts about the authenticity of the Epinomisand speculations that it was composed by Philip ofOpus, Plato’s amanuensis, can be found in DiogenesLaertius, (((.*%; and Suidae Lexicon, ed. A. Alder,Leipzig #$!-–*$, s.v. ‘Philosophos’. See also, L. Tarán,Academica: Plato, Philip of Opus, and the Pseudo-PlatonicEpinomis, Philadelphia #$%.; J. Dillon, ‘Philip of Opusand the Theology of Plato’s Laws’, in Plato’s Laws: fromTheory into Practice, Proceedings of the VI SymposiumPlatonicum, ed. S. Scolnicov and L. Brisson, SanktAugustin !""*, pp. *"/–##. D. J. O’Meara, Plato-nopolis: Platonic Political Philosophy in Late Antiquity,Oxford !""*, debunks the myth that the Neoplatonistshad no interest in the Laws and politics.!*. Proclus, In Rempublicam, ed. W. Kroll, Amster -

dam #$)., (.#.##: W$+3 5-H !*'+%' 3b'(- 5J)&' +>' +J81&)-+3@(8 3b'(- $9&!>' µ7 c))&' d +7' +J8 ."@$+G8 !&)-+3@(8 X<M?G$-', e8 +L' f#µ%' +7' +L' '#µ%'.!/. O’Meara (as in n. !!).

!.. Proclus, Platonic Theology, ed. H. D. Sa&rey andL. G. Westerink, Paris #$)-, (.#*.#%–!!: +> 3b'(- +&_8T3&C8, +> !"&'&3g' !*'+%', +> 9(+H 5@9G' +H !*'+( c?3-'9(4 µG53µ@(' ,9 +L' K3-"#'%' 3V$5;K3$T(- !("(+"&!M'.Q(R+’&h' i+- µ6' j!*'+%' ,$+4 +L' ,' T3&)&?@k 5&?µ*+%'."K&3-5;$+3"(, !('+4 9(+(<(';8.!). The authenticity of the Laws (along with the

Epinomis) was often discounted in the #$th centuryuntil Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Möllendor& accepted itas a genuine work by Plato. The identification of theanonymous Stranger, however, has been varied, asshown by the following notable examples. F. Ast,Platon’s Leben und Schriften, Leipzig #-#), pp. *--–-$pointed out di;culties with the Athenian Stranger:‘Dazu gesellt sich endlich noch das Unplatonische der äusseren Form. Die Personen des Gesprächs sind ohne Zweifel erdichtete Namen, nehmlich derLake dämonier Megillos, der Kreter Kleinias und derathenäische Fremdling; dagegen Platon in seinenGesprächen immer, wenigstens seinen Zeitgenossen,bekannte Personen einführt. Auch das Dramatischeund die Charakterschilderung sind ganz vernach-lässigt.’ G. Grote, Plato and the Other Companions ofSokrates, / vols, London #--.–--, (0, p. !%* n. #, o&eredthe following comments on the relationship of theidentification of the Athenian Stranger to the dramaticsetting and the dogmatic tone of the dialogue: ‘It is

DENIS J.-J. ROBICHAUD $.

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 95

Plato’s first interpreter, Aristotle, mentions that the Stranger is Socrates.!% Cicerotakes the identification with Plato for granted, commenting briefly, without groundsor arguments, that Plato spoke with Clinias and Megillus (the two other interlocu -tors of the Laws). As in the case of the Neoplatonists, however, neither Aristotle norCicero addresses the dialogic problem of interpreting Plato.!- Diogenes Laertius,as we have seen, says that previous interpreters equated the Athenian Strangerwith Plato; but the interpreters themselves remain anonymous since he neitherquotes nor names them. What information we have on the interpretation and identification of the Anonymous Stranger in antiquity—from Cicero, Plutarch,Diogenes Laertius and Stobaeus—is sparse, fragmentary and seldom explicit.!$

There are two other noteworthy cases, however, where the identities of theinterlocutors in the Laws is discussed. The first is Basil of Caesarea who, in hisletter #*., uses prosopopoeia to interpret the Platonic dialogues and mentions ofits application to the Laws. He tells us:

But where he [Plato] introduces uncertain characters (!"#$%!() into the dialogues, they aregiven the conversational role of settling matters; but he does not develop anything else fromthe characters (!"#$%!() in his thinking—as, for example, he writes in the Laws.*"

Basil explains that Plato forgoes rhetorical adornments and introduces uncertainor indefinite interlocutors (.#"-$+( !"#$%!() when getting to the heart of thematter. His reference to the Laws presumably points to the Athenian Stranger, wholacks character traits beyond his country of origin. Although Basil’s exegetical

$) FICINO, PLATO’S PERSONA AND THE INCARNATION

remarkable that Aristotle, in canvassing the opinionsdelivered by the lTG'(g&8 U;'&8 in the Laws, cites themas the opinions of Sokrates (Politics. ii. #!)., b. II), who,however, does not appear at all in the dialogue. Eitherthis is a lapse of memory on the part of Aristotle; orelse (which I think very possible) the Laws were orig-inally composed with Sokrates as the expositor intro-duced, the change of name being subsequently madefrom a feeling of impropriety in transporting Sokratesto Krete, and from the dogmatising anti-dialectic tonewhich pervades the lectures ascribed to him. SomePlatonic expositors regarded the Athenian Stranger in Leges as Plato himself (Diogen. L. iii. .!; Schol. adLeg. I). Diogenes himself calls him a !)*$µ( .'/'0µ&'.’P. Friedländer, Platon, * vols, Berlin and Leipzig #$)/,(, pp. #*/–*., #/#, and (((, p. *)", argues that Platomakes the Athenian Stranger anonymous so as todistance his person from what Socrates represents toPlato, and sees more of Solon in him than Socrates. G.Morrow, Plato’s Cretan City: A Historical Interpretationof the Laws, Princeton #$)", p. %/, says: ‘In no otherdialogue do we feel less of a dramatic screen betweenourselves and Plato. The anonymity of the Athenianmeans that there is no independent character to besustained, as is true of the Socratic dialogues, even the Republic; and Plato is free as nowhere else to putforward his own doctrines.’ H.-G. Gadamer, ‘Platoand the Poets’, in his Dialogue and Dialectic, tr. R. C.Smith, New Haven, CT #$-", p. %#, says that it is ‘the

Athenian in whom more than anyone Plato has mostobviously hidden himself ’. Describing the AthenianStranger as representing Socrates if he had fled toCrete instead of accepting his fate from Athenianjustice, L. Strauss, The Argument and the Action of Plato’sLaws, Chicago #$%., passim, esp. pp. #–!, presents thedialogue’s setting as a type of counter-factual history.T. Szlezak, Reading Plato, London #$$*, pp. !, !#–!!,claims that the Athenian Stranger remains anonymousin order better to reflect his city’s culture, but thatPlato did not wish to hide anonymously behind hischaracters. More recently, both C. Zuckert, Plato’sPhilosophers, Chicago !""$, pp. ##–#!, *#–**, -!–#/),and C. H. Zuckert, ‘Plato’s Laws: Postlude or Preludeto Socratic Political Philosophy?, Journal of Politics,',0(, !""/, pp. *%/–$., have argued that the dramaticdate of the Laws is a period between the Persian and Peloponnesian wars, thus turning the AthenianStranger into a figure for pre-Socratic philosophy. !%. Aristotle, Politics, #!).a.!-. Cicero, De legibus, (./.#..!$. H. Tarrant, Plato’s First Interpreters, London

!""".*". St Basil, Lettres, ed. Y. Courtonne, ((, Paris

#$)#, CXXXV: m!&0 56 .#"-$+( !"#$%!( ,!3-$*?3-+&g8 5-()#?&-8, +J8 µ6' 3=9"-'3@(8 n'393' +L' !"(?µ*+%'9;K"G+(- +&g8 !"&$5-()3?&µ;'&-8, &=56' 56 n+3"&' ,9 +L'!"&$/!%' ,!3-$909)3g +(g8 X!&T;$3$-'· i!3" ,!&@G$3',' +&g8 f#µ&-8.

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 96

strategy attributes clear and explicit argumentative positions to the Laws, he doesnot explicitly identify the Athenian Stranger with the persona of Plato. The safestand most satisfactory way of interpreting this passage is to read it as followingBasil’s description of Plato’s ability to write in various stylistic registers, and hischaracterisation of the lack of rhetorical figures and character development in theLaws as examples of simplicity, brevity and clarity in speech and argumentation—stylistic traits which, as he also tells us in the letter, are appropriate to Christians.The second case is Oxyrhynchus Papyrus no. *!#$, where the Athenian Strangeris briefly named as Plato.*# It is obvious, however, that Ficino does not known thepapyrus fragment; and it seems unlikely that he is making use of the passage fromBasil.

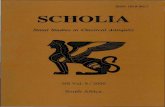

Nevertheless, Ficino’s explicit identification of the Athenian Stranger as Platoin his Epitome on the Laws is not merely his own speculation. He is drawing on ananonymous introductory X!#T3$-8 or scholion to Plato’s Laws included in his Greekmanuscript of Plato’s dialogues (Fig. #).*!The scholion makes the identificationbased on the claim that the Athenian Stranger discusses two republics whichsupposedly correspond to two dialogues: the Laws and the Republic.**The evidenceof Ficino’s use of the scholion is apparent and obvious. As can be seen in hisEpitome, however, Ficino is not translating from it verbatim, but rather ad sensum,at times paraphrasing, at times removing or adding material (Table #).

What, then, are the explicit dogmas proposed by the Athenian Stranger, orPlato, in the Laws?

<=9> <=(0(8 ?2>2 / 8( <=(8 ?2>2

His letter of #/-% to Braccio Martelli, entitled ‘Concordia Mosis et Platonis’, underscores Ficino’s prosopopoeic understanding of Plato’s corpus.*/ In it hesuperimposes onto the image of Plato’s Academy the ancient metaphor of exegesisas progressing into a temple’s inner sanctum. Ficino and his humanist contem-poraries inherited from the ancients the practice of presenting levels of exegesisaccording to the architectural metaphor of progressing through stages of a pagantemple. This metaphor, found as early as Varro among the Latins),*. is usuallypresented as variations on a theme containing the following stages: popular

*#. On Oxyrhynchus Papyrus no. *!#$ see H.Tarrant, ‘Where Plato Speaks: Reflections on anAncient Debate’, in Who Speaks for Plato? (as in n. %),pp. )%–-" ()$–%#).*!. Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana MS

Plut. -.."$, fol. !-$v. For a transcription see ScholiaPlatonica, ed. W. C. Greene, Haverford #$*-, p. !$).See above, n. #., for scholarship on this manuscript. T.Mettauer, De Platonis scholiorum fontibus, Zurich #--",pp. !%–*!, argued that Proclus was the source for thescholion, based in part on a claim that Proclus alsoidentified the Athenian Stranger as ‘Plato ipse’ in hiscommentary on Republic (.#-).*"–#-%.!*. Yet Proclusdoes not seem to be addressing any kind of Platonicquestion here; he is simply quoting Plato.

**. Ficino also seems to find confirmation ofPlato’s identity as the Athenian Stranger through theaccounts of his travels; see his De vita Platonis, inFicino, Opera, (, p. %).. */. See Supplementum Ficinianum (as in n. #.), (,

pp. CII–III. *.. On the use of this metaphor in Varro, Proclus

and Poliziano see D. J.-J. Robichaud, ‘Angelo Poli-ziano’s Lamia: Neoplatonic Commentaries and thePlotinian Dichotomy between the Philologist and the Philosopher’, in Angelo Poliziano, Lamia: Text,Translation, and Introductory Studies, ed. C. Celenza,Leiden !"#", pp. #*#–-$. Among Latin authors seethe works cited by P. Courcelle, ‘Le personnage dephilosophie dans la littérature latine’, Le Journal desSavants, (0, #$%", pp. !"$–.! (!/# n. #).).

DENIS J.-J. ROBICHAUD $%

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 97

interpretation (outside the temple); grammatical readings of verba or );U3-8 (thethreshold of the vestibule of the temple); the interpretation of philosophicalcontent (advancing through the pronaos into the temple itself); and finally turningto the anagogical or theological meaning of a text (penetrating into the temple’sinner sanctum, the adyton). Already in Plotinus one finds important uses of theimage of the adyton to explain henosis and, among Iamblichus, Proclus and otherNeoplatonists, it is deployed to explain the exegetical approach to the Platoniccorpus and the cursus of studies in the Neoplatonic scale of disciplines. Proclusmakes this clear, for example, in his commentary on the First Alcibiades, which hebelieves, following Iamblichus, to be the first work of the Platonic corpus and apropaedeutic introduction leading towards the final theological dialogues. Thefigurative advance through the textual temple therefore maps onto Proclus’s triadof ,!-$+"&<M–!"#&5&8–µ&'M and is understood as the purgative conversion (,!-$+ -"&<M) through which the soul becomes initiated by means of the rites of minor andgreater Platonic mysteries in order to remain with the One (µ&'M).*) Augustineemploys the image in Contra Academicos in order to describe Antiochus of Ascalon’ssacrilegious introduction of certain evil Stoic ashes into the adyta, the inner sanc-tums, of Plato’s Academy.*%This long tradition has its roots in the very languageof mysteries which Plato himself employs*-—a point not lost on Ficino, whodeploys the mystagogic image of an accessus into the adyta of Platonic mysteriesin his numerous prologues and in his writings on the Platonic corpus and on Neo -platonic texts, as well as on philosophical, theological and poetic works.*$

The playful dramatic setting to the letter on the ‘Concordia Mosis et Platonis’is Martelli’s arrival at Plato’s Academy, where he is greeted not only by theAthenian Stranger but also by all of Plato’s dramatis personae, that is, by Parmenides,Protagoras, Laches, Phaedrus, Philebus and others, as well as by characters ofPlatonic myth such as Er and Diotima, and by later Platonists like Plotinus, Philo,Iamblichus, Proclus and even Augustine, all of whom guide the reader into thePlatonic mysteries. In the letter to Martelli, Ficino makes each Platonic !"#$%!&'voice specific opinions or dogmas. He concisely distils his interpretive findings inthe Laws when he presents the Athenian Stranger to Martelli as follows:

You will hear a certain old Athenian asserting that the world is arranged by the Word of God and that God is the measure of all things, especially if God become man (si Deus fiathomo). Just as you will hear him striking down the proud with lightning bolts as rebelliousagainst God, and approving the humble as most beloved of God. Finally, you will hear himpredicting that whether they descend into hell or ascend to heaven, they will discover divinejudgement everywhere./"

$- FICINO, PLATO’S PERSONA AND THE INCARNATION

*). Plotinus, Enneads, 0(.$.##; Proclus, Commentaryon Alcibiades, (...#–#/; Marinus, Vita Procli, #*; seeRobichaud, ‘Poliziano’s Lamia’ (as in n. *.).*%. Augustine, Contra Academicos, (((.#-./#. *-. See, e.g., É. des Places, ‘Platon et la langue des

mystères’, Annales de la Faculté des Lettres d’Aix, ,,,0(((,#$)/, pp. $–!*, now in idem, Études Platoniciennes (asin n. #-), pp. -*–#"!.

*$. See, e.g., Ficino, Opera, (, pp. ))%, $/%–/-, and((, pp. ##!-–!$, ##*)–*%, #.*%–*-, #./-, #-*); PlatonicTheology (as in n. #/), ,(. The impact on Ficino of theAsclepius, which depicts a theological dialogue perhapsin the adyton itself, cannot be neglected./". Ficino, Opera, (, p. -)): ‘Audies senem quendam

Atheniensem, verbo Dei mundum esse dispositumasserentem, Deumque rerum omnium esse mensuram,

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 98

The Stranger, here described as Atheniensis Senex,/# presents the following dogmas:God created and arranged the world by means of the Logos; he is the measure ofall things, was incarnated into man, has no tolerance for the prideful who rebelagainst God, favours the humble and meek, and confirms the existence of divinejudgement in the afterlife. Concerning the criticism of those who rebel against God,it seems that Ficino is interpreting the strict laws against atheism proposed by theAthenian Stranger in the dialogue./! That the humble are the most beloved ofGod is Ficino’s interpretation of the laws which, in the dialogue, protect strangers,foreigners, guests and pilgrims (U;'&-) because they are under the guardianship ofZeus. He relates these laws to a Homeric custom of U3'@(, or hospitality, which inturn is related to the belief that any stranger could be a god travelling among menin disguise or costume—a belief criticised in the Republic./*

As for the remaining dogmas, Ficino finds the doctrines concerning creation,the Logos and divine judgement in his interpretation of Laws (0.%#.E: ‘O men,that God who, as old tradition tells, holdeth the beginning, the end, and the centreof all things that exist, completeth his circuit by nature’s ordinance in straight,unswerving course. With him followeth Justice always, as avenger of them that fallshort of the divine law.’// Scholars have remarked that in this passage Plato revealsa fragment of an ancient Orphic hymn, with which Ficino was clearly familiarsince he quotes it as early as #/.% in his De divino furore./. As demonstrated bySebastiano Gentile, he worked with the hymn through Niccolò Siculo’s Latintranslation of the pseudo-Aristotelian De mundo./) At this stage Ficino was prob-ably not making use of the Greek sources for the hymn, yet by the time he quotesit in his Philebus commentary, his Platonic Theology, his Disputatio contra iudiciumastrologorum, his commentary on Plotinus and his Epitome on the Laws, he is

maxime vero si Deus fiat homo, superbos tamquam aDeo rebelles e&ulminantem, humiles vero probantemtamquam Deo charissimos, denique omnibus praedi-centem sive descenderint in infernum, sive in coelumascenderint, eos ubique divinum iudicem reperturos.’ /#. Both Celenza and Wesseling believe that, in

calling him Atheniensis Senex, Poliziano is playing onthe fact that it sounds similar to the Greek lTG'(g&8U;'&8: Celenza, in his edition of the Lamia (as in n. *.),p. !"% n. #); and Angelo Poliziano, Lamia: Praelectio in priora Aristotelis analytica, ed. A. Wesseling, Leiden#$-), p. /). I would add that it seems appropriate that,for Ficino, the Athenian Stranger should be calledAtheniensis Senex if he is Plato communicating dogmas,since Plutarch tells us (Iside et Osiride, /-.*%") thatPlato expressed his doctrines more explicitly in his oldage./!. On Ficino and atheism see J. Hankins,

‘Monstrous Melancholy: Ficino and the PhysiologicalCauses of Atheism’, in Laus Platonici Philosophici, ed.S. Clucas et al., Leiden !"##, pp. !.–//; and D. J.-J.Robichaud, ‘Renaissance and Reformation’, in TheOxford Handbook of Atheism, ed. S. Bullivant and M.Ruse, Oxford !"#*, pp. #%$–$/./*. Plato, Republic, *-#C-D.

//. Plato, Laws, ed. G. P. Goold and tr. R. G. Bury,Cambridge, MA #$-/, %#.E: o'5"38 +&@'0' <Lµ3'!">8 (=+&C8, ` µ6' 57 T3#8, W$!3" 9(4 ` !()(->8 )#?&8,."KM' +3 9(4 +3)30+7' 9(4 µ;$( +L' p'+%' j!*'+%'\K%', 3=T3@k !3"(@'3- 9(+H <C$-' !3"-!&"30#µ3'&8· +O5’.6- U0';!3+(- q@9G +L' .!&)3-!&µ;'%' +&R T3@&0 '#µ&0+-µ%"#8 …/.. The Orphic fragment can be found in Orphi -

corum fragmenta, ed. O. Kern, Dublin #$%! (fr. !#).Kern categorises the hymn among the Fragmenta veteriora, pp. $"–$*. See also M. L. West, The OrphicPoems, Oxford #$-*, pp. -$–$". W. Burkert, ‘DasProömium des Parmenides und die Katabasis desPythagoras’, Phronesis, ,(0, #$)$, pp. #–*" (## n. !.),suggests that Plato may also be drawing on Orphicfragment #.- in describing q@9G as following Zeus./). S. Gentile, ‘In margine all’epistola “De divino

furore” di Marsilio Ficino’, Rinascimento, ,,(((, #$-*,pp. **–%%; idem, ‘Nello “scriptorium” ficiniano: LucaFabiani, Ficino Ficini, e un inedito’, in Marsilio Ficino:fonti, testi, fortuna, ed. S. Toussaint, Rome !""), pp.#.$–)#; Marsilio Ficino, Lettere, ed. S. Gentile, ! vols,Florence #$$" and !"#", (, pp. CCXLVI–VII, and ((,pp. XL–XLII.

DENIS J.-J. ROBICHAUD $$

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 99

#"" FICINO, PLATO’S PERSONA AND THE INCARNATION

/%. Proclus, Platonic Theology, 0(.-, and In Par -menidem, 0(.###*–#). Dillon, ‘Neoplatonic Reception’(as in n. #$), pp. !/*–./, discusses Neoplatonic readings of this passage as well as other parts of theLaws./-. Plato, Laws (as in n. /*), %#)C: ` 57 T3>8 rµg'

!*'+%' K"Gµ*+%' µ;+"&' s' 3tG µ*)-$+(, 9(4 !&)_µu))&' v !&C +-8, W8 <($-', c'T"%!&8./$. Ficino, Opera, ((, p. #."": ‘Ambiguus vero hic

legitur textus. Alibi enim legitur ut traduxi. Quibusverbis Plato videtur Protagoram confutare, dicentemrerum mensuram hominem esse. Cuius error in libroDe scientia subtiliter confutatur. Alibi vero legitur, non“quam quivis homo”, sed “si quis homo”, hunc inmodum: “Deus omnium nobis est mensura, multoque

magis, si quis, ut ferunt, homo est.” Tu hanc parti-culam, “si quis, ut ferunt, homo est”, exponere potes,“si quis homo mensura est, multo magis Deus estmensura, non enim nobis, sed Deo, per quem vivimus,debemus vivere.” Posses forsan exponere, “si Deusaliquis homo est”, id est, “si quando fiat homo”, “utferunt”, id est, “oracula Prophetarum”, quae quidemexpositio utinam, quam pia est apud multos, tamaccepta foret apud Platonicos.’ See C. Trinkaus, ‘Pro t-agoras in the Renaissance’, Philosophy and Humanism:Renaissance Essays in Honor of Paul Oskar Kristeller, ed.E. Mahoney, Leiden #$%), p. !"). Trinkaus mentionsthe passage about Protagoras but does not discussFicino’s interpretation of the variant.

drawing directly on the Greek sources. In fact, in these works he quotes the hymnalong with book (0 of the Laws and interprets it with the help of a scholion to Laws%#.E on his Greek manuscript of Plato, neither of which occurs explicitly withthe hymn in De mundo or in De divino furore (see Fig. ! and Table !).

The scholiast proposes the reading of Jove as God and as the e;cient andfinal cause of everything. He also indicates that the old saying mentioned by theAthenian Stranger is, in fact, an Orphic hymn about Jove. In order to confirm thatthe golden dogma of Moses is found in the Laws, Ficino follows the advice fromthe scholion in his Epitome and o&ers his own reading which draws on the writingsof Hermes Trismegistus and the hymn of Nemesis. De mundo speaks of Nemesisin the same breath as the Orphic hymn, so his allusion to Nemesis is further evidencethat the work is one of Ficino’s sources. The hymn was on occasion discussedamong Neoplatonists, most notably by Proclus, who partially quotes the fragmentin his Platonic Theology and also discusses it in his Parmenides commentary;/% butsince Proclus does not o&er a causal reading of the hymn, it is clear that Ficino, inexplaining God as both the e;cient and final cause, is following the scholiast.

As for the final dogma, the Incarnation, Ficino finds it shortly after the previously mentioned segment, in Laws %#)C: ‘In our eyes God will be “the measureof all things” in the highest degree—a degree much higher than is any “man” theytalk of.’/- About this Ficino writes in the Epitome on the Laws:

But the text reads as doubtful here. For in one place it reads as I translated it [i.e., quam quivishomo]. With these words it seems that Plato is confuting Protagoras, who says that man is the measure of things. His error is carefully confuted in the book On Knowledge [i.e., theTheaetetus]. But elsewhere it does not read ‘than any man’ (quam quivis homo), but ‘if a certainman’ (si quis homo), in this way: ‘God is for us the measure of all things: and much more so,if, as they say, he is a certain man.’ You could interpret this small section ‘si quis, ut ferunt,homo est’ [3t !&0 +@8, W8 <($-', c'T"%!&8 ] as ‘if a certain man is the measure, much more isGod the measure, for we ought not to live for ourselves but for God, through whom we live.’ You could perhaps also interpret ‘if God is a certain man’ as ‘if he were ever to becomeman’ (si quando fiat homo) and ‘as they say’ (ut ferunt [W8 <($-']) as ‘the prophecies of theProphets’, if only this interpretation were accepted among Platonists as pious, as it is amongmany others./$

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 100

.". See Plato, Theaetetus, #.*D, where the goldenstring of Zeus is presented as an absolute measure toargue against the relativism of Protagoras’s theory ofman as the measure of all things, and #)#C, whereSocrates mocks the theory by comparing it to the ideaof pigs or baboons as the measure of all things..#. See D. J.-J. Robichaud, ‘Working with Plotinus:

A Study of Marsilio Ficino’s Textual and DivinatoryPhilology’, in From Florence to Europe: Teachers, Students,and Scholars of Greek in the Renaissance, ed. F. Cicco -lella and L. Silvano (forthcoming, Leiden !"#/ or!"#.)..!. For this manuscript see above, n. #...*. The origin of the variation was perhaps an

iotacism of the comparative v and the conditionalconjunction 3t: modern philologists also change encliticaccents on the upsilon and iota of !&C +-8../. The two variants found in Ficino’s manuscript,

Florence, Laurenziana MS Plut. -.."$ (c), occur inthe so-called Vatican Plato, Vatican City, BAV MS Vat. gr. # (O), and in Florence, Laurenziana MS Plut. .$."# (a). This is to be expected since (c) is anapograph of (a) and, as demonstrated by Post (as in

n. #.), pp. *)–*$, the text of the Laws in (a) is a veryaccu rate copy of (O). The reading v !&C +-8 occurs asthe principal one in another important Plato manu -script: Paris, BnF MS gr. #-"% (A). Post, ibid., pp. $–#/, and idem, ‘The Vatican Plato’, Classical Quarterly,,,((, #$!-, pp. ##–#., has demonstrated that (O) isindepen dent of (A) until Laws v.%/)C, but that never-theless, numerous readings of the text of Laws, books(–0 in (A) are found as variants in the margins of (O).The variant reading v !&C +-8 in (O) is written in a handreferred to by Greene in his Scholia Platonica as (O/).Thus Greene (as in n. *!), p. *#%, lists the scholion as: ‘%#)c v !&C +-8 (A: 3t !&0 +@8 O). +&R !(+"-*"K&0 +> D-D)@&'· v !&C +-8 (O/)’. There is an ongoing argu-ment in the literature on these manuscripts as towhether the scholia in (O) refer to a certain ‘book ofthe patriarch’; see, most recently and with furtherreferences, M. J. Luzzatto, ‘Emendare Platone nell’ antichità. Il Caso del Vaticanus Gr. #’, Quaderni distoria, ',0(((, !""-, pp. !$–-%.... See above, n. /$..). See above, n. /".j#")

DENIS J.-J. ROBICHAUD #"#

In the Athenian Stranger’s statement that God is the measure of all things, Ficinonot only reads a critique of Protagoras’s saying (notably in the Theaetetus) thatman is the measure of all things, but goes so far as to find a prophecy for the Incar-nation.." His Christological exegesis is, in fact, divinatory philology (emendatio opeingenii) and is based on his deliberations over the two textual variants found inGreek manuscripts of the Laws (emendatio ope codicum), indicated by ‘alibi verolegitur’..# We find a confirmation of the divinatory reading in Ficino’s letter toBraccio Martelli, ‘Concordia Mosis et Platonis’, where he renders the passagefrom Laws %#)C not as ‘quam quivis homo’ (‘than any man’), as we have it in hisPlato translation, but as ‘si Deus fiat homo’ (‘if a certain man’). Both readings weresuggested to him by his manuscript of the dialogue, now Florence, LaurenzianaMS Plut. -.."$..! The text given in the main body of the manuscript is 3t !&0 +@8(! ‘si quis homo’), above which a scholion indicates the variant reading v !&C +-8(! ‘quam quivis homo’) (Fig. *)..*The same two variants are, in fact, found inother Plato manuscripts../ Ficino’s philological moves to interpret the passage asprophetic are as follows:

! For his Plato translation he chooses the reading v !&C +-8! ‘quam quivis homo’.

! In his Epitome on the Laws, he focuses on the other reading: 3t !&0 +@8! ‘si quishomo’ ! ‘si quis, ut ferunt, homo est’ ! ‘si Deus aliquis homo est’ ! ‘si quandofiat homo’ ! ‘si Deus fiat homo’; and in his discussion of this passage, he considersthe interpretation of W8 <($-'’ ! ‘ut ferunt’ ! ‘ut oracula Prophetarum ferunt’...

! Then, finally, in his Latin translation of Laws %#)C in ‘Concordia Mosis etPlatonis’, his Commentary on Pseudo-Dionysius and Commentary on St Paul, he hasdistilled these thoughts and settles on the prophetic reading: ‘si Deus fiat homo’..)

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 101

#"! FICINO, PLATO’S PERSONA AND THE INCARNATION

#. Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana MS Plut. -.."$, fol. !-$v, the beginning of the Laws in Ficino’s Greek manuscript of Plato’s dialogues. The opening scholion is examined in Table #

SU CONCESSIONE DEL MIBACT – E’ VIETATA OGNI ULTERIORE RIPRODUZIONE CON QUALSIASI MEZZO

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 102

DENIS J.-J. ROBICHAUD #"*

Marsilio Ficino, In dialogum primum De legibus, quoted from his Opera omnia, ! vols, Basel #.%) (facs. repr. with introduction by S. Toussaint, Paris !""").

Quod autem personam hic Platonis subipso Atheniensis hospitis nomine, et idquidem modestiae gratia lateat, legentideinceps ex multis perspicue apparabit, exeo praecipue, quod a;rmabit se geminastractavisse respublicas. (Opera, II, p. #/--)

Atheniensis hospes, id est, Plato profectusin Cretam prope Cnosum o&enditMegillum Lacedaemonium, et CliniamCretensem, quem una cum novem aliisCnosii accersiverant, ut coloniam indededucerent, urbem conderent, eique legesdarent. Hi ergo duo ad sacrum Iovisantrum consulturi de hoc accedebant: his factus obvius Atheniensis hospes,quidnam acturi irent interrogavit. Illi leges excogitaturos esse se responderunt.Verum cum multa de legibus interrogati ab hospite, quaestionem haud satis absolverent, et hospes illis ad leges aptissimus videretur, obsecraverunt eum,ut ad civitatem legibus instituendam unacum ipsis adiutor accederet.

(Ibid., p. #/-$)

Hic ergo non coget homines, si noluerint[voluerint sic. cod.] inter se facere cunctacommunia, permittet ut fieri solet, propriasingulos possidere. Neque tamen cautis-simus auriga noster omnino laxabithabenas. Nam praeter summam aliarumdiligentiam legum, prudentissime sanciet,ne cui liceat ultra certum, et illum quidemmediocrem terminum census amplificare,ne aliis quidem copia, nimia, aliis obsitinopia, neque cogantur, id quod miserabileesse putat, multi inter patriae suae ulnasesse mendici. (Ibid., p. #/--)

Anonymous scholion in Florence,Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana MSPlut. -.."$, fol. !-$v (Fig. #), quotedfrom Scholia Platonica, ed. W. C. Greene,Haverford #$*-.

` lTG'(g&8 &w+&8 U;'&8 !3!&@G+(- ,'+(RT( 3V8+7' N"M+G' .!-/', \$+- 56 1)*+%', e8 ,9 +&R53 <('3"#'. (=+>8 ?H" ` lTG'(g&8U;'&8 ,' +O.. +L' f#µ%' );?3- i+- v5G (=+O5C& !&)-+3g( !"&G'C$TG$('· …&h' &=5’

5C& !&)-+3g( !"&G'C$TG $… d &h' &=5’,93g'(- 1)*+%'&8, d 3V µ7 +&R+&, ` (=+>8 s' 3tG +O lTG'(@x U;'x. &w+&8 &h' 3V8N"M+G' .<-9#µ3'&8 9(4 !3"-+0?K*'%' \U%!"> +J8 N'%$$&R N)3-'@k +3 +O N"G+4 9(4y3?@))x +O z(935(-µ&'@x, ,!-+3+"(µµ;'&-8µ6' X!> +L' +7' N'%$$>' &V9&C'+%' .!&-9@('!&-M$($T(- ,93gT3' 9(4 9(+($+M$($T(- !#)-''#µ&08 +6 !"&$M9&'+(8 +&g8 !&)@+(-8 5-(T3g'(-,!"&$3KL8 5’e"µGµ;'&-8 ,!4 +> +&R q->8c'+"&', :3">' +&R+& ?3'#µ3'&' j?-/+(+&', ,' { +H $3!+#+(+( 9(4 .""G+# +(+( +L'µ0$+G"@%' ,!3+3)3g+&· !3"-+0K|' 5’&h' (=+&g8` U;'&8, 9(4 +(R+( !("’(=+L' ÷ !0T#µ3'&8,[*]

v"3+& ,!4 +&C+&-8 +@'38 s' 3b3' &: '#µ&-· +L'56 µ7 50'GT;'+%' +3)3@(' .!&5&R'(- +7' +L' '#µ%' 5-*T3$-', `"/'+%' 56 +>' U;'&' 3h !("3$930($µ;'&' !3"4 '#µ%' T;$-', 9(4!("(9()&C'+%' $0))M!+&"( (=+>' ?3';$T(-+J8 !&)-+3@(8, c"K3+(- ` lTG'(g&8 U;'&8 +J8+L' '#µ%' 5-(T;$3%8· …5-(T;$3%8· &Y8 57

U;'&8 +J8 +L' '#µ%' … ,' &Y8 57 &=9;+-,W$!3" ,' +&g8 +J8 µ3?*)G8 1&)-+3@(8, 9&-'H!*'+( !"&$+*++3-, .))’ }9*$+x .?">'.!&';µ3- 9(4 !">8 +&C+x &V9@(', \+- µ;'+&- 9(4 ?0'(g9( V5@(' 9(4 !(g5(8 &=9;+- 9&-'&C8,!)7' i+- &=56 +(R+( .#"-$+( .<J93', .))H +&_8 9)M"&08 3V8 e"-$µ;'&' ."-Tµ>'!3"-;)(D3'. +3$$( "*9&'+( ?H" 9(4 !;'+3 +&_8!*'+( 9)M"&08 5-(';µ3-' !("(93)3C3+(-· +7'5’(V+@(' +&R +&$&C+&0 ."-Tµ&R ?'%$#µ3T(,i+(' (=+>8 ,!-µ'G$T~ …

[*] �!#T3$-8] ÷ rasura habet A: continuat O (=+L'!0T#µ3'&8.

(Scholia Platonica, p. !$))

Table #. Comparison of the scholion to the beginning of the Laws in Ficino’s manuscript ofthe Platonic dialogues, and three passages from his Epitome of Plato’s Laws

Anonymous scholion in Florence,Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana MSPlut. -.."$, fol. !-$v (Fig. #), quotedfrom Scholia Platonica, ed. W. C. Greene,Haverford #$*-.

Marsilio Ficino, In dialogum primum De legibus, quoted from his Opera omnia, ! vols, Basel #.%) (facs. repr. with introduction by S. Toussaint, Paris !""").

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 103

!. Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana MS Plut. -.."$, fol. *")r, showing Laws %#.D–%#-B in Ficino’s Greek manuscript of Plato’s dialogues. The scholion to Laws %#.E is examined in Table ! and shown enlarged in Fig. *

SU CONCESSIONE DEL MIBACT – E’ VIETATA OGNI ULTERIORE RIPRODUZIONE CON QUALSIASI MEZZO

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 104

Table !. Comparison of the scholion to Laws %#.E in Ficino’s manuscript of the Platonicdialogues, and two passages from his Epitome to Plato’s Laws

Marsilio Ficino, In dialogum primum De legibus, quoted from his Opera omnia, ! vols, Basel #.%) (facs. repr. with introduction by S. Toussaint, Paris !""").

Item ubi ait Deum rerum principia, etfines, et media continere, intellige Deumesse causam rerum e;cientem, atquefinalem, servare omnia, omnibusque adesse.

(Opera, II, p. #/$$)

Tu vero angelica haec aureaque praeceptaservabis, alta mente reposita. Quod autemmysteria haec antiquo ait sermone constare,Mosaico possumus intelligere. Possumusquoque et Mercuriali quodam, et Orphico,apud quos eiusmodi multa perlegimus, etilla quidem evidentissima, quae recenseregrandius iam prohibet argumentum. At siOrphicos de Iove, de lege, de iudicio, etiustitia, et Nemesi hymnos legeris, haec adverbum invenies omnia.

(Ibid.)

Anonymous scholion in Florence,Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana MSPlut. -.."$, fol. *")r (Fig. !), quotedfrom Scholia Platonica, ed. W. C. Greene,Haverford #$*-.

Z3>' µ6' +>' 5Gµ-&0"?>' $(<L8, !()(->' 56 )#?&' );?3- +>' ’�"<-9#', i8 ,$+-' &w+&8 -

�3_8 ."KM, �3_8 µ;$$(, q->8 5’,9 !*'+( +;+09+(-·

�3_8 !CTµG' ?(@G8 +3 9(4 &="('&R .$+3"&;'+&8.

9(4 ."K7 µ6' &w+&8 e8 !&-G+-9>' (t+-&',+3)30+7 56 e8 +3)-9#', µ;$( 56 e8 ,U t$&0!u$- !("/', 9s' !*'+( 5-(<#"%8 (=+&Rµ3+;K�. 3=T3@k 56 +> 9(+H 5@9G' $Gµ(@'3- 9(4.U@(', 9(4 .!("3?9)@+%8, 9(4 &:&'34 9('#'-}'@. +> 56 !3"-!&"30#µ3'&8 +> (V%'@%8, +> .34e8 (�+%8 9(4 9(+H +H (=+*· r ?H" !3"-<&"H+&R+& \K3- e8 ,' (V$TG+&g8.

(Scholia Platonica, p. *#%)

Anonymous scholion in Florence,Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana MSPlut. -.."$, fol. *")r (Fig. !), quotedfrom Scholia Platonica, ed. W. C. Greene,Haverford #$*-.

Marsilio Ficino, In dialogum primum De legibus, quoted from his Opera omnia, ! vols, Basel #.%) (facs. repr. with introduction by S. Toussaint, Paris !""").

*. Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana MS Plut. -.."$, fol. *")r, enlarged detail showing the scholia at Laws %#.E and %#)C

SU CONCESSIONE DEL MIBACT – E’ VIETATA OGNI ULTERIORE RIPRODUZIONE CON QUALSIASI MEZZO

DENIS J.-J. ROBICHAUD #".

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 105

When, at the end of the passage from the Epitome to the Laws quoted above,Ficino speaks of the ‘many others’ who accept such a reading as pious, he is referring to the interpretations of George of Trebizond and Cardinal Bessarion. In #/."–.#, George translated Plato’s Laws, the critique of which is found in thefifth book of Bessarion’s In calumniatorem Platonis of #/)$. Ficino’s general use ofGeorge and Bessarion’s works while translating Plato has been well established..%

The following example, however, shows Ficino not just using previous translationsbut also having doubts about manuscript variants and debating their possible readings in a commentary. Concerning Laws %#)C, Bessarion criticises George’s translation:

Plato also rejects the opinion of Protagoras, who said that man is either the measure, themeasurement or the limit of all things; he also refutes the opinion in the dialogue Theaetetus,where it is written with more reasons and the best ones. ` 57 T3>8 rµg' <($- !*'+%' K"Gµ*+%'µ;+"&' s' 3tG µ*)-$+(, 9(4 !&)_ µu))&' d !&0 +@8, W8 <($-', c'T"%!&8. ‘Let God’, he says, ‘befor us the measure of all things, especially all the more than man, as some prefer.’ Translator[i.e., George of Trebizond]: ‘God therefore is the greatest measure of things and much more,if he is a certain man, as is said.’ Therefore, it is said that in the view of Plato, God is a man,if the translator is to be believed. And because he is a man, he is the measure of all things,which Plato judges that it is impious to attribute to human nature. This is the way he [i.e.,the translator, George of Trebizond] knows the opinions of the philosophers. And this is the way he understands Plato, whom he reproaches..-

One can see from this quotation that Ficino quotes George verbatim in his Epitomewhen considering the correct reading of the passage. Bessarion rejects the variant3t !&0 +@8 and chooses d !&0 +@8. He therefore finds fault with George for acceptingthe reading 3t !&0 +@8 in his translation;.$ and criticises him for expressing theIncarnation in Plato’s thought, while nonetheless daring to reproach Plato as aphilosopher.

What is most important to retain from Ficino’s reading of the Greek variantsto Laws %#)C in both the manuscript scholion and in George and Bessarion’sdisagreement is that although in his Epitome to the Laws and in his translation ofPlato Ficino sides with Bessarion in adopting the variant v !&C +-8! ‘quam quivishomo’, elsewhere he adopts the second witness, 3t !&0 +@8 ! ‘si quis homo’ ! ‘si

#") FICINO, PLATO’S PERSONA AND THE INCARNATION

.%. Hankins, Plato in the Italian Renaissance (as inn. #.), ((, pp. /%"–%#; Gentile, ‘Note sui manoscrittigreci’ (as in n. #.); F. Pagani, ‘Platonis Leges GeorgioTrapezuntio interprete. Introduzione, edizione criticae appendici’, Tesi di perfezionamento, Pisa, ScuolaNormale Superiore !"##. .-. Bessarion, In calumniatorem Platonis, Venice

#."*, fol. $!v: ‘Item Plato sententiam reiicit Prota -gorae, qui hominem esse dicebat modum sivemensuram aut metam rerum omnium, quam sententiam in sermone quoque, qui Theaetetusinscribitur pluribus atque optimis rationibus confutat.` 57 T3>8 rµg' <($- !*'+%' K"Gµ*+%' µ;+"&' s' 3tGµ*)-$+(, 9(4 !&)_ µu))&' d !&0 +@8, W8 <($-', c'T"%!&8.“Deus”, inquit, “sit nobis meta omnium rerum in

primis, longeque magis, quam homo, ut aliquivolunt.” Interpres: “Deus igitur omnium mensuramaxime rerum est, multoque magis, siquis, ut fertur,homo est.” Ergo Deum hominem esse fertur Platonissententia, si credendum est interpreti. Et quoniamhomo est, meta est omnium rerum quod Platonaturae humanae tribui nefas arbitratur. Ita hic opiniones novit philosophorum. Ita Platonem, quemreprehendit, intelligit.’ .$. See, e.g., a manuscript copy of George of

Trebizond’s translation: Munich, Bayerische Staats-bibliothek, Clm *"/, fol. /-v: ‘Deus igitur omniummensura maxime rerum est, multoque magis siquis ut fertur homo est.’ It is possible that George was notaware of the dogmatic implications of his translation.

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 106

Deus fiat homo’, in order to conclude that Plato prophesised the Incarnation.Ficino thus chooses a more conservative reading of the variants in his philologicalcollation of the text when he translates it, but permits himself to push the bound-aries of orthodoxy in his exegesis of the passage’s dogmatic meaning.)"

I have already o&ered a first instance of Ficino adopting the second divinatoryreading in his letter to Braccio Martelli, ‘Concordia Mosis et Platonis’. He confirmsthis in two other, later works. In the third chapter of his incomplete commentaryon St Paul’s epistles, on which he worked late in life, he addresses the reasons whythe Logos came to mankind:

The large epistle, too, testifies that the Word, the divine light and the life of God itselfdescended to human senses—ears, eyes, hands—so that men through the Son would beunited happily with the heavenly Father [ John #.#–.]. Certain ancient prophets seem to havedivined something similar, where they introduce some of the gods in human form, saving andhelping men. Why, however, God, having made his Son a man, wished him to be sacrificedfor mankind, we will reveal as follows with Paul. It seems also that our Plato touched in theLaws on something which pertains to the human nature assumed by God, where he says:‘Man is not the measure of all things, but God is, indeed especially if God becomes man (siDeus fiat homo).’)#

Ficino here quotes verbatim the divinatory reading of the Greek variant of %#)Cto support a Pauline interpretation of the Incarnation in Plato. Likewise, in hiscommentary on Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite’s On the Divine Names, com pletedaround #/-$–$!,)! he makes use of precisely the same variant to demonstrate thatthe second person of the Trinity is proclaimed in Plato’s Laws:

After this, Dionysius says that the eternal Son of God with wonderful benevolence assumedfor himself human nature and at the same time did not change in any way. The PlatonistAmelius venerated this mystery while recalling the Gospel of John; Plato, moreover, arguingagainst Protagoras, said that ‘man is not the measure of all things, but God is, indeed especially if God becomes man (si Deus fiat homo)’. We have also discussed the reasonsbehind this mystery in our book De Christiana religione.)*

)". See Gentile’s discussion of Ficino’s use of twovariants in the Orphic hymn in his ‘In margine’ and‘Nello “scriptorium” ficiniano’ (as in n. /)).)#. Ficino, Opera, (, p. /*#: ‘In epistola quoque

magna, verbum lumenque divinum et ipsam Deivitam ad sensus humanos, aures, oculos, manus,descendisse testatur, ut homines per filium cum patre coelesti feliciter iungerentur. Simile quiddamantiqui vates augurati videntur, ubi Deorum aliquemintroducunt sub humana figura homines salutantematque iuvantem. Cur autem Deus filium factum tamhominem, pro hominibus sacrificari voluerit, insequentibus cum Paulo declarabimus. Videtur etiamPlato noster nonnihil ad humanitatem a Deo assump -tam pertinens, in legibus attigisse, ubi ait: “Mensurarerum omnium non homo, sed Deus est, maxime verosi Deus fiat homo.” ’)!. On Ficino and Pseudo-Dionysius see S.

Toussaint, ‘L’influence de Ficin à Paris et le Pseudo-

Denys des humanistes: Traversari, Cusain, Lefèvred’Étaples. Suivi d’un passage inédit de Marsile Ficin’,Bruniana et Campanelliana, 0, #$$$, pp. *-#–/#/; C.Vasoli, ‘L’Un-Bien dans le commentaire de Ficin à laMystica Theologia du Pseudo-Denys, in Marsile Ficin etles Platonismes à la Renaissance, ed. P. Magnard, Paris!""#, pp. #-#–$*; M. Cristiani, ‘Dionigi dionisiaco:Marsilio Ficino e il Corpus Dionysianum’, in Il Neo -platonismo nel Rinascimento, ed. P. Prini, Rome #$$*,pp. #-.–!"*; P. M. Watts, ‘Pseudo-Dionysius theAreopagite and Three Renaissance Neoplatonists:Cusanus, Ficino, and Pico on Mind and Cosmos’, inSupplementum Festivum, ed. J. Hankins, J. Monfasaniand F. Purnell Jr., Binghamton #$-%, pp. !%$–$-.)*. Ficino, Opera, ((, p. #"!$. This passage is also

now available in Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, De mystica theologia, De divinis nominibus, tr. MarsilioFicino, ed. P. Podolak, Naples !"##, p. *- (De divinisnominibus, #...$–%"): ‘Post hec Dionysius eternum

DENIS J.-J. ROBICHAUD #"%

04-Robichaud.qxp_JWCI 29/12/2014 13:46 Page 107

In the exegesis from these two later theological commentaries, then, Ficino sanctions reading the Incarnation into Plato’s dogmas through his divinatoryphilology of Laws %#)C.