Map Semiotics: The Wizarding World of Harry Potter

Transcript of Map Semiotics: The Wizarding World of Harry Potter

EUROPEAN HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY

Bachelor program of information and communication ВА Media and communication

Spec. Visual culture and creative industries: audiovisual media (television and cinema)

NASTASSIA YEREMENKO3-year student, group 9

ASSIGNMENT

Map Semiotics

(“THE WIZARDING WORLD OF HARRY POTTER”)

WRITTEN PAPER

ON SUBJECT “SEMIOTICS”

Revised by:

Almira Ousmanova

Vilnius, 2014

CONTENTSIntroduction to cartographic semiotic analysis.................3

Semiotic Analysis of Universal Orlando “THE WIZARDING WORLD OF

HARRY POTTER” theme park map ..................................7

Informational level...........................................7

Symbolic Level................................................8

Units.......................................................9

Relations..................................................10

Combinatorics..............................................10

Ideology...................................................11

Conclusion....................................................13

Literature....................................................14

Annex.........................................................15

2

INTRODUCTION TO CARTOGRAPHIC SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS

When google-ing in search for a map, the results are

overwhelming: they come in all forms, shapes, colours and even

dates which they date back to. This sets on a critical thought

and attitude towards the task we are given – to come up with a

scheme or strategy of semiotic analysis of a map. On the one

hand, this filed is barely researched, on the other – the texts

that have been written on this topic seem thorough enough for me

to be able to add something else.

Yet, we all can agree that a map is a visual representation of

any type of territory, and not simply representation, but a

symbolic one, hence the person who aims for analysis is

contemned to work with signs of different levels. Clearly, the

types of maps created over the years are numerous – such a

variety does not make it easier in any way to give a well-put

description to them. But as any notion does not stand for the

thing it denotes, a map stands for an idea of the land or

territory it corresponds to.

Surely there has to be a certain link between the territory

and a map that portrays it, so that a viewer could recognize the

fact of the visual material to be a map. Consequently, I am

prone to thinking that there are some basic qualities that

define the notion of a map: it consists of shapes and forms

completed independently and existing in relation to one another,

based on the anticipated recognize-ability which lies in historic memory

of a viewer. In simpler words, a map is a combination of

differently organized spaces (in shapes, forms, lines, signs).

These spaces contain meanings of different levels: a triangle (a3

sign) can denote “an iron mine”, a separate line – a river, and

a line between two shapes can stand for “a border between two

countries” [see ANNEX 1]. So the meaning of the same sign (a

line), can change in accordance to its position in relation to

surrounding spaces. Another important component to the

definition of a map – is its intention to be recognized by a

viewer. That can be achieved by a number of ways:

Mimic depiction of the principle objects (pictorial

manner);

Literal commentary (marginal notes);

Shared symbolic system.

But in my view, especially from a contemporary perspective, I

believe the recognition becomes possible due to historic memory

of a human being. It may happen because of our premature

exposure to shapes since the moment we are born, as well as

strengthened by our constant encounter with organizations of

these shapes represented in culture.

Since the kindergarten children are introduced to the image of

the worlds, since the first grade they are familiar with the

shape of their country, and since the primary school everyone

has the idea of the map of the world [see ANNEX 2]. I can assume

that we learn about the world in map perspective, to make it

clearer in advance, even when learning alphabet through on-wall

hangers, children are exposed to the “minimal sign” when

memorizing letters in their correspondence to a fruit presented

beside [see ANNEX 3]. That is why I believe that a modern human

being is unconsciously ready for interpreting a map, especially

if this encounter happens to a school graduate. In case of a

4

child with no access to education the situation may differ, but

I assume from my - a school graduate’s - point of view.

Nevertheless, I do not refrain from supposition a relatively

same possibility in the case of ancient tribes, cave paintings

of whom may also be compared to cartographic representation [see

ANNEX 4]. Hence I believe that a person is likely to recognize a

person, a mountain, or even a lake (if painted blue), if they

are brought to life in mimic perspective.

The analysis of a map can be divided in the following steps,

or categories:

Map symbolism;

Ideology (context).

Strongly believing in dual nature of everything, and seeing

the first category as a form and the second as content, I at the

same time do not exclude the possibility of the third meaning.

On the contrary, I am convinced that stating the fact of the

occurrence of the open meaning in map semiotics can lead to its

more thorough analysis.

I cannot deny the excellence of Hansgeorg Schlichtmann’s list

of schemes of the semiotics of maps, and I hardly dare not to

refer to his points when empirically analyzing, but I would

develop his achievements by combining them with crucial

cartographic characteristics mentioned by Rudolf Arnheim,

especially those influencing the map perception. And in that case I

will start with pointing out the importance of the view’s

position in relation to a map, which is anticipatorily

established by the map’s creator.

5

The thing is, a map and the way it presents itself to a viewer,

defines its rendition,

as well as its

character. It can be

either open/inviting, or

closed/excluding (the terms

are provisional). Let

us say, that the map is

directed to North and is rendered in salient manner.

Such a portrayal of territory opens itself, presents itself as

if a landing stripe was presenting itself to a landing plane

full of tourists leaning against illuminators, already absorbed

by a city they were dyeing to go to. It is like when you look at

such a map you can picture yourself walking down those streets.

Such portrayals are good solutions for tourist maps, and in

Belarus are called prospect/panorama maps [see ANNEX 5]. Usually

they also contain numbers above tourist attraction with a legend

nearby with literary information (name of the attraction).

Google maps work that way when enlarged to yield; but they also

skillfully exclude the viewer when the latter zooms out/lessens

the scale [see ANNEX 6].

The closed/exclusive type of

map, on the other hand,

somehow separates a map and

its viewer. Any map rendered

from almost satellite

perspective can be seen as a

closed one as it presents

6

territory from a hardly achievable point of view. I would say

that the reading of this kind of map implies a great deal of

imagination and an absolutely “unnatural” way of thinking. But

even this “unnaturality” is being trained to be recognized

through social practices: education, media, daily life (using

electronic gadgets, public transport schemes, emergency exit

plans, etc).

Nevertheless there is a hypothetic

possibility of a viewer’s invitation to a

presupposedely closed map by implementing

“human” prints, signs onto its surface.

Whether it’s by implying the signifiers of

danger (skulls), or by placing foot traces

from one point to another, the level of

communication is achieved through them.

It’s another confirmation of my

supposition that it is the matter of

communication when reading any map. There has to be a contact

established between both sides, and it also implies the

necessity of the mutual language, or at least the shared sign

system with corresponding system of meanings. There is certainly

a message in a map, but this message can only become a part of

speech if decoded by the viewer. In a word, it takes two for a map to

function.

But it is another confirmation of the fact that map is a

result of global social progress, because its basic principles

are almost universal, and even those treasure maps, primarily

7

aimed at such marginal groups as pirates, for instance, can

easily be recognized by modern children1.

Speaking of universally shared concept of map culture, I feel

it rational to adress the principal components of cartographic

semiotics. I will address the points suggested by Hansgeorg

Schlichtmann as I see them the most theoretically covered.

As I have stated above, we can divide map provision into two

groups: Map symbolism and its ideology/context. Map symbolism

includes such components as signs and everything that implies to

them (concept, form, perceptional characteristics, their

organization in space, usage of space). Ideology, or context,

corresponds to any kind of information visible on a map that

implies the author, the message, the historic background, the

target audience, and other factors that might be

principal/influential for a map to become its final self.

The third or the open meaning is something that just happens.

It might be visible, but it most probably will go unnoticed, or

will not be paid any attention due to its superficial character.

This may be clearer when seen from Barthes’s triple scheme of

meaning, where:

1. an informational level would cover the shapes, colours,

relations between the objects, everything a viewer can

potentially recognize in the picture;

2. a symbolic level would cover any reference of

informational level objects to their signified (a level of

signification);

1 Yet I have never seen an actual treasure map, so my opinion is extremely subjective.

8

3. the third/open/existing level would cover anything of

signifiance.

Both ways, Schlichtmann and Barthes’s, appear to be applicable

to empirical semiotic analysis of a map. I think they both cover

the principle components of it, but from slightly different

perspectives.

I would like to make my map analysis from Barthes’s

perspective but applying Schlichtmann’s notions, as his

descriptive elements seem to come of hand when analyzing the map

symbolism. That means that I will follow the structure of

meaning suggested by Barthes, but will address both Arnheim and

Schlichtmann when explaining the content of those meaning

levels. But in a way, the position of those three authors

interrelate, as all of them, and we (students) included, are

entering the sign system where meaning is a vertical core of a

map language.

9

SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF UNIVERSAL ORLANDO “THE WIZARDINGWORLD OF HARRY POTTER” THEME PARK MAP [SEE ANNEX 7]

Informational level

The map is directed to North and can be seen as an

open/inviting type as we can see the principal objects in the

perspective form and dimension. Nevertheless we see that

perspective is relative because the buildings, for example the

castle of Hogwarts, open themselves for the viewer like a

children’ book with models. We can guess that they are 3-

dimentional, but in the picture they seem 2-dimensional because

of the limits of the map itself.

The map can be divided into three parts: Hogsmeade, Hogwarts

express and Diagon alley. I am making such a division based on

the fact of three boards overlaying the actual portrayal of the

territory with the corresponding names. They can be seen as

marginal notes, according to Schlichtmann. They are placed in

the third dimension of the map, the one closer to the viewer,

the one corresponding to the represented land, but at the same

time not belonging to the land – the board does not hang in the

city, on the castle, or any object/territory represented on the

map. The first and the third boards are hanging from above and

literally indicate the territory. The second board is placed at

the very bottom in the middle of the map. The shape of its curls

somehow direct the viewer towards the map above, indicates the

corresponding territory.

Another literal component of the map is the name flags.

Throughout the map the flags are rising from the principal

10

objects: three broomsticks, Honeydukes, Hogsmeade Station,

Hogwarts, Flight of the Hippogriff, Hagrid’s Hut, Dragon

Challenge, King’s Cross Station, Leaky Cauldron, Knockturn

Alley, Weasleys’, Olivander’s, Gringotts, London. There are

also three flags that represent territory and not the place they

rise from. They are “Harry Potter and the forbidden Journey”,

“Wizard Wheezes” and “Harry potter and the Escape from

Gringotts”. The three along with land correspondence, play

symbolic role, but I will talk about it in the second part of

the analysis.

Yet other literal components of the map are “The Lake” and the

tracks of letters, primarily placed in Hogsmeade territory, but

also significant in London part. The former states the type of

land surface literally represented under it, the former plays a

symbolic role.

The geographic surface of the land is performed in a dashing

manner, which once again reminds the viewer of the picture. The

painter’s decision of placing shadows on the right hand-side of

the mountains in the middle of the map can be seen on the sides

as well: trees do cast shadows along with the roofs of building

being faded to black in the South-East.

The on-land objects can be divided into three types:

1. The actual objects (houses, trees, hills, etc.) Those

objects are portrayed in a mimetic manner and remind the viewer

of a picture.

2. The symbolic objects which are drawn on the map but do not

exist on the actual territory (the hippogriff, the dragon – both

pictured engaged into the surrounding environment). 11

3. The ideological objects. In this case ideology applies to

the representation, because in fact all the objects could be

considered ideological because they form a fictional land. But

in ideological representation sense, there is one example of

such an object – the Evil Tree. It exists on the land, but is

pictured as a combination of word lines. The same word lines can

be seen on the wizarding part of land, and its function was

briefly described above. This method can be linked to the nature

of the object portrayed – exceptionally magic, and unobtainable

to a muggle2 eye/mind. But at the same time those word lines are

also organized in a mimetic manner, so the final shape reminds

the viewer of a tree, especially this one who is acquainted with

the ideology of the map. This group also includes flags waving

from the buildings tops and footprints.

The map is done in old style: yellow paper, perspective

drawings of mountains, towns and other objects, and according to

Salischtchen it could be read without difficulties. The only

knot on that lineal statement is the fictional ideology of the

map I have chosen, that is why I will proceed with the deeper

analysis of symbols and ideology.

Symbolic Level

Analyzing sign complexity, from the above described formal

analysis, is visible, that its complexity is majorly comprised

by pictures which are “artifacts, created primarily as

instruments of signification and communication”. The problem of

2 A muggle is a person who is born into a non-magical family and is incapable of performing magic. The definition taken from: http://harrypotter.wikia.com/wiki/Muggle

12

picture-artifact dichotomy can be relatively omitted in this

analysis as we speak about a fictional map.

All map components of the chosen map can be considered plan-

related, as apart from literal guided in the form of flags and

boards, all the object stand in relation to each other, hence I

do not see it possible to concentrate on separate objects aside

from their surroundings – the principle feature of the map is

interrelations of the objects comprising the represented

territory.

The territorial signs in space perspective can be divided into

three categories: scaleless (single objects), lineal (lineal paths,

railway road) and widescale (valley, parks, lake, trees, fields,

etc.). Lineal signs in Latin represent the magical paths in

apposition to muggle ones. They occur and are visible to wizards

only. Supposedly they can be seen as paths only by those who can

read magic. But the last pont is purely ideological, which will

be the issue of further analysis.

So that to be able to characterize the signs of the map

without ideology, I will refer to mostly mentioned above formal-

perceptual features. And one of the signs that I have missed and

the one that will suit the formal- perceptual

characteristic is The Lake. The surface of the water is

performed in a pictorial manner which extraordinarily represents

water, astrologically if to be certain. Such a combination of

astrologic sign Aquarius3 and the surface of lake does not occur

3 Aquarius symbol. Available from the Internet: http://www.compatible-astrology.com/aquarius-symbol.html

13

instantly, that is why the literal layer has been used – “The

Lake”. Even though the words are placed overlaying the lake

itself, but the calligraphic component of it once again

correspond to “water”. It does interrelate with ideology of the

map, but it does not exclude the natural symbolism either.

Further on symbolism, I will refer to Schlichtmann’s

analytical system of cartographic symbols: units, relations and

combinatorics.

UnitsThe map includes several topemes – places shown as single

items. They are Hogwarts castle and Hagrid’s Hut in Hogsmeade

and somehow a double-decker in London. They exist relatively

independently and separately. The only visible relation they are

having is their belonging to the territory represented by the

map.

There are much more topeme complexes which are comprised by

several topemes related to one another:

Hogsmeade a town comprised by Three Broomsticks, Honey

Dukes, Hogsmeade Station and a railway going to the tunnel;

The Lake comprised by a ship, the name and the bridge;

Dragon Challenge venue including the tent for the

competitors, the dragon and the the venue itself;

The Travel between King’s cross Station in London and

Hogsmeade combining a couple of resembling one another mountains

and hills, as well as some trees and meadows;

London is a big topeme complex of separate topemes but

inevitable relating to one another. Altogether, there are

Knockturn Alley, Diagon Alley, Leaky Cauldron, Weasleys’, 14

Olivander’s, Gringotts, King’s Cross Station and the outskirts

of the city. At first seems possible to regard them separately,

but the road system and the waving flags create an all-combined

complex which has to be viewed as one. Still, there is a degree

of separation, but this one if of ideological nature which will

be covered further.

And there are also two4 minimal signs present on the map – the

hippogriff with the flag “Flight of the Hippogriff” and

Gringotts with the flag “Harry Potter and the Escape from

Gringotts”. Even though there is no legend beside the map, the

same relation can be seen between the object presented and the

name rising in the form of flag from this object. Together they

comprise a topeme which could not be possible without both – an

object and a flag with the name. “These are signs the

expressions of which cannot be broken down into units which are

themselves expressions, i.e., which convey meanings”.

In the case of the hippogriff we see not simply the creature

but the event of the flight, the event which took place in Harry

Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban in the lecture lead by Hagrid

for the first time in the position of a professor. The

hippogriff is a connotation of the flight that took place in the

third book/movie. And for the view to get this meaning there is

a flag.

In the case of Gringotts we do not simply see the building of

the bank, but we see the wings of a hidden dragon from Harry

Potter and the Deathly Hollows where the famous trio was getting

4 There can be three minimal signs if to include the Dragon near the Dragon Challenge topeme. It is a connotation to the first competition in the tournament in Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire.

15

the cup from the bank dungeons. The Gringotts with a fiery

dragon is a connotation to the epic escape of the trio from

Gringotts in the 7th book/film. And for the view to get this

meaning there is a flag.

Both these minimal signs operate within the specifics of local

syntax which will be described further in combinatorics.

RelationsSign relations have partially been covered in the description

of the tree boards presented on the map which stand as a third

dimension and also correspond to the territories under and above

them. Also the relational aspect has been covered in description

of The Lake and the waving flags rising from represented

objects. Much more interesting situation is taking place with

combinatorics.

CombinatoricsThe combinations of local units or any objects on a map can be

seen from two perspectives: local syntax and supralocal syntax. The

former is vivid in two examples of minimal signs as they become

topemes specifically thanks to such a combinatorics. The latter

refers to “the arrangement of topemes and their integration into

larger configurations, and the underlying combination patterns

ultimately reflect factual arrangement of objects in earth

space”. And according to the author, this works for internal

structures of the objects. This kind of syntax must not be

confused with ideology of a map, even though it irrevocably is

influenced by it. To put an example, terraced houses of London

are organized along the streets and sometimes the rows of trees.

At the same time objects are separate and do not overlay one

another. Combinatorics is directly related to the pictorial 16

mimetic style of the map that is why the objects are combined in

accordance to their space arrangement.

The linking point between symbolic combinatorics and ideology

lies in the following example. When we look at the map we

clearly see that it consists of the above mentioned three parts.

The combinatorics issue becomes of prior interest when we look

at their internal organization with the help of formal signs.

There is no smooth transition between the three. But there is a

line, varied ideologically, but still linking the three – the

railway. Taking its beginning from Hogsmeade station in the form

of the rails it enters the tunnel and then leaves it in the form

of letter line. This method cannot be explained apart from

ideology which is separation of the magic world from the muggle

one. As soon as the track reached the mountain level it changed

into rails once again. Such a method explains the possible

transition from one world to another, but it is an ideological

thing that can be easily recognized primarily by insiders.

IdeologyIdeology can stand for a combination of authors and their

beliefs in the world they capture on the map. In my

understanding ideology in map analysis is the idea that

penetrates all above mentioned levels of meaning and finds its

way to the surface through physical features, which also

reflects “the socio-cultural background or context of the

cartographic product”. Some of them were already mentioned, but

I will make a notice of those that remain uncovered.

Most of the ideological decisions are references to the

original idea of the Marauder’s Map by Moony, Wormtail, Padfoot

17

and Prongs [ANNEX 8]. This map was created by students of

Hogwarts more than twenty years ago. The map was supposed to

come being very handy to its creators, that is why the colour of

it is old-yellow and the structure of the surface is pretty

shabby. The same reference applies to the lineally organized

letters. In the original these were presented in Latin and

mostly meant spells that made up the whole idea of the Hogwarts

castle. In the chosen map the words are not in Latin, they read

“THE WIZARDING WORLD OF HARRY POTTER” all through the map. The

same phrase can be found around the frame of the map, it refers

to the producer of the map, the organization of Universal

Orlando theme park. It might be a trade mark engraved in the map

on different levels. Such a decision may also be seen as a

manifestation of the third meaning suggested by Barthes, or

peripheral signification, according to Schlichtmann.

In my opinion, another interesting display of the third

meaning can be seen in the area of the ship on the Lake. The

blast of water created by a moving ship does not match the

structure of still waters around. It is obvious that the ship

was placed there. And inside-people would also state that the

ship itself has been drawn in a different manner compared to

that it was visualized in the film Harry Potter and the goblet

of Fire. The same scent of buffoonery can be observed in

perspective of some of the object. The bridge, for instance,

does not go with the surrounding objects as far as its

perspective depiction is concerned. These are meaningful flubs

that are principal for the analysis, but can hardly fall into

any other level of interpretation.

18

Another ideological feature of the map is the position of

footprints. The same component can found in the original

version, but in that case the footprints are always linked to

the name of their owner in the form of literal representation.

In the case of the chosen map the footprints can be found at

random places in Hogsmeade and London. But they can only be

found along with lineal words which might mean that the steps

could belong to wizards only, because as I have stated before,

the lineal words correspond exclusively to the wizarding world.

At the same time, taking into consideration the fact that we

deal with a relatively fictional land, I see it reasonable

taking easy on the issue: the whole map is ideological, because

it all represents the idea that was brought to life, firstly,

through Joanne Rowling in Harry Potter Series, secondly,

visualized in 8 harry Potter films by Warner Bros. company and

then brought to “muggles” in Universal Orlando in a form of the

theme park. With this map, which is another piece of franchise

merchandise the author, or I would rather say creators intended

to create the atmosphere, the image of the land, so that to

orient the view in their shared fantasy.

19

CONCLUSION

Semiotics claims to be an independent research field, but yet

is a shaky ground in the internal structure of its own. In my

research I have tried to semiotically analyze a map through

Barthes’s perspective. Yet, I cannot but state that the

antecedent authors such as Charles Sanders Peirce and Ferdinand

de Saussure also gave functional semiotic structures that seem

potential for analysis implementation. I am prone to thinking

that those ideas tend to interrelate as semiotics as a

discipline deals with sign system or a language in any form

possible. Hence no matter which approach one chooses for

semiotic investigation, they will inevitable meet sign demands:

perception and interpretation.

Even though the nature of sign can be seen as dual or ternary,

in the end anyone dealing with semiotics will encounter the

necessity to articulate the sign functions, be in the form of

dual dichotomy of denotation-connotation or signifier-signified;

or ternary scheme of icon-image-symbol or information-symbolism-

the third meaning. Personally, I would love to try all the

schemes when analyzing one case, but that was not the point of

the assignment. But I am sure that if tried out, I would come up

to the conclusion that any material of sign nature is an

individual case for semiotic analysis no matter through which

domain-conceptual apparatus I will precede my investigation.

In case of cartographic semiotics, probably, Peirce’s ternary

concept would work even better taken the fact of the specific

sign language used in this visual form – it’s full of icons,

images and symbols. But I have chosen Barthes due to the fact 20

that my analytical target was extremely ideological as it deals

with fictional territory. In the end, we see that map represents

a text written in a specific language which must have a

recognizable structure, but is open to artistic and author’s

ideology to be implemented. And as any other text it is meant to

be read and interpreted, as only in communication its initial

function is fulfilled.

21

LITERATURE

1. BARTHES, R. The third meaning [cited on 9 December 2014;

15:39]. Available from the Internet:

http://perf.tamu.edu/musc402/files/2012/02/Barthes-The-

Third-Meaning.pdf

2. SCHLICHTMANN, H. Overview of the Semiotics of Map [cited on

9 December 2014; 16:17]. Available from the Internet:

http://icaci.org/files/documents/ICC_proceedings/ICC2009/ht

ml/refer/30_1.pdf

3. SCHLICHTMANN, H. Peripheral meaning in maps: The example of

ideology [cited on 9 December 2014; 15:54]. Available from

the Internet:

http://meta-carto-semiotics.org/uploads/mcs_vol1_2008/mcs_2

008_1_schlichtmann.pdf

4. АРНХЕЙМ, Р. Восприятие карт [просмотрено 9 декабря 2014

года; 10:46]. Доступ через Интернет:

http://www.gumer.info/bibliotek_Buks/Psihol/arnh/05.php

5. САЛИЩЕН, К. Картоведение [просмотрено 9 декабря 2014 года;

13:32]. Доступ через Интернет:

geoman.ru/books/item/f00/s00/z0000060/st018.shtml

22

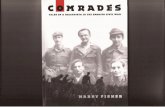

ANNEX 76

ANNEX 8

6 Larger version available here http://www.insidethemagic.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/diagon-alley-map.jpg

26

![5. Harry Potter dan Orde Phoenix [EbookGratis.Web.id].pdf](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/6324a72fe491bcb36c09edf6/5-harry-potter-dan-orde-phoenix-ebookgratiswebidpdf.jpg)