Makah acculturation, Northwest Coast

Transcript of Makah acculturation, Northwest Coast

Acculturation and Narcissism: A Study of Culture Contact among the Makah IndiansAuthor(s): Mark S. FleisherSource: Anthropos, Bd. 79, H. 4./6. (1984), pp. 409-431Published by: Anthropos InstituteStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40461865 .

Accessed: 08/11/2013 16:58

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Anthropos Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Anthropos.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Anthropos 79.1984: 409-431

Acculturation and Narcissism: A Study of Culture Contact Among the Makah Indians Mark S. Fleisher

Introduction

This study examines the psychological, social, and linguistic responses of the Makah Indians to acculturation. The Makah are a Nootkan people who live on Cape Flattery in the isolated commu- nity of Neah Bay, Washington (see maps). This study suggests that the Makah adapted and coped well with Euroamerican economic goals; how- ever, changes in domestic family organization, traditional ritualism, and language, engendered a loss of social and psychological cohesion in the Makah community. Acculturative changes in Makah ideology, and in the community's socio- political dynamics had two effects: they reinfor- ced the replacement of the Makah language by American English; and facilitated the expression of narcissistic behavior in a culturally uncontrol- led, social environment. A link is postulated between the psychosocial pressure of accultura- tion, and contemporary patterns of community mental health (e.g., alcoholism, domestic vio- lence).

Mark Stewart Fleisher, Ph. D. in Anthropology (1976, Washington State University), Associate Prof. - Main inter- ests: Cultural Anthropology y Anthropological Linguistics, Applied Educational Linguistics; Contemporary American Culture; Northwest Coast of North America. - Fieldwork: Mexico (Otomi), Guatemala (Highland Maya), Northwest Coast (Salishan and Nootkan), Eastern Indonesia. - Publica- tions include: Clallam: A Study in Coast Salish Ethnolin- guistic (Diss.); "Pronunciation Index and Clallam-English Vocabulary" (1975); "Aspeas of Clallam Phonology and Their Implications for Reconstruction" (1977); "The Ethno- botany of the Clallam Indians of Western Washington" (1980); "The Potlatch as a Public Art Form" (Anthropos 76. 1981); "The Educational Implications of American Indian English" (1982); "Hesquiat Kinship Terminology: Social Structure and Symbolic World View Categories" (Anthropos 79.1984).

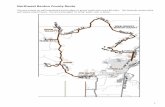

Map 1: Western Washington and Southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia

Makah acculturation is divided into three ethnohistoric periods: (1) Early Contact Period - 1788-1854; (2) Middle Contact Period - 1855-1919; (3) Late Contact Period- 1920-1983. Each Contact Period includes a sociolinguistic, sociocultural, and psychosocial stage, as outlined in table 1 .

This study is founded in Kohut's psychoana- lytic theory (Kohut 1966, 1971, 1972, 1977, 1978; Ornstein 1978, especially pp. 337-374; also see Goldberg 1980; Redfearn 1983; Westley 1983). In this study, the dynamic principal is that individu- als, and groups as collective expressions of indi- viduals, will attempt to restore and maintain

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

410 Mark S. Fleisher

Table 1

Stages of Makah Acculturation

Ethnohistoric Sociolinguistic Sociocultural Psychosocial Periods Stage Stage Stage

1. Early Contact: Cape Flattery: Nootkan Culture Nootkan Culture 1788-1855 Language & Society & Society & Personality

2. Middle Contact: Language Cultural Narcissism 1 855-1 920 Replacement Discontinuity

3. Late Contact: American Cultural Psychological 1920-1983 English Adjustment Adjustment

Map 2: Nootkan Local Groups on Cape Flattery and Cape Alava

Tatooeh Island

'^^^^^%A Bay

^Äi^Fla^t^y)^^ ^?adï Ißland

Tsyesji/Ï r '

Point j' A. r' R2X*4 of the Archet # X J ̂T^ ^^^N

OzetteT %' J' i; f s' r^C

Sand Pointf) ^£^¿2 Kr-/

0 2 4 Q miles

self-cohesion in response to changes in their sociocultural environment. In the case of the Makah acculturation, their attempts to restore and maintain self-cohesion followed an identifiable course.

The Makah People The Makah are culturally and linguistically

related to Nootkan groups living along the west coast of Vancouver Island, British Columbia. The aboriginal Makah and other Nootkan groups renowned for their whaling, fishing, and skill at hunting (Drucker 1951, 1965: 132-160; Sapir 1915). The Makah, unlike Northwest Coast Indi- an groups such as the Kwakiutl, Coast Salish, and Tlingit, are a relatively unstudied population.

Their geographic isolation on Cape Flattery has kept them out of the easy reach of anthropol- ogists, linguists, and archaeologists. In the late 1960s, however, Daugherty and Fryxell (1967) excavated a portion of the southern Makah village of Ozette at Cape Alava (15 miles south of Cape Flattery) which had been occupied by Nootkan people for centuries. Forced by United States Government to place their children in the Neah Bay school (Colson 1953: 78; Ruby and Brown 1981: 17), the Makah families at Ozette abando- ned this village and moved to Neah Bay in the early years of the 1900s.

Extensive excavations at Ozette have yielded a wealth of artifactual material, and have brought public and professional attention to the Makah

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Acculturation and Narcissism 411

(e.g., Clark 1971; Daugherty 1971; Daugherty and Kirk 1976; Kirk and Kirk 1980). However, Makah ethnography, ethnohistory, and linguis- tics are poorely represented in the published literature on native Northwest Coast peoples.1

The Makah were selected for this study for two reasons. First, I have ethnographic and linguistic fieldwork experience on the Olympic Peninsula, since 1974, with the Makah, at Neah Bay and Port Angeles, Washington, and with the (Salishan) Clallam, on the Lower Elwha and Little Boston reservations at Port Angeles and Port Gamble, Washington, respectively. These expe- riences provided me with observations of contem- porary life in Indian communities, and Indian- white relations in this region.

Second, Makah acculturation provides a com- parative situation as it sharply contrasts with my observations on acculturation from central Mexi- co, and Sulawesi, Indonesia.2 It is common, for

example, for Otomi men (State of Hidalgo, Mexico) to leave their desert homes in the Mesquital Valley of central Mexico and assume Mestizo identities, and social roles in nearby large towns or Mexico City. Their temporary assimila- tion is accomplished by changing into Mestizo clothes, and by not speaking Otomi. This tempo- rary identity allows them the freedom to move between ethnic groups and speech communities with relative ease. Yet they can return to their Otomi homes and resume their traditional lives. Their successful ability to shift residences and ethnic groups hinges on their ability to shift their languages.

In a similar fashion, Torajanese, Buginese, and Makassarese people in southern Sulawesi, Indonesia, move from their traditional, and often quite rural, homes to large, urban centers (e.g., Ujung Pandang, southern Sulawesi, or Jakarta, Java). In these urban centers, Bahasa Indonesia is the common language used in business and personal interactions outside of the home. The ease of a Bugis man in switching from his first native language, Buginese, to Indonesian permits his successful sociolinguistic entry into the urban, ethnically heterogeneous speech communities of Indonesia.

Though the Otomi and southern Sulawesi examples are presented in oversimplified form, the point is that linguistic competence, the knowl- edge of grammar and the social use of language, in more than a single language, provides potential access to contrasting sociocultural and sociolingu- istic situations. This movement is impossible when an individual is monolingual, either in the native language of his own community, or in the language of an alien, dominant group. The latter situation has prevailed for the Makah in the early 1900s and today; through culture contact with

1 Primary sources of data for this study are Swan's (1820) work, which is the first published ethnographic data on the Makah, Colson's original (1953) community study describing the Makah village of Neah Bay during her fieldwork in 1941-42, and Reports of the Commissioners of Indian Affairs, 1854-1947. Secondary sources for particular aspects of Makah culture (e.g., Spanish contact, games; music) include: Densmore 1939; Dorsey 1901; Ernst 1952; Gibbs 1877; Gormly 1977; Günther 1960, 1972; McReavy 1973; Meares 1967; Ruby and Brown 1981; Wagner 1933; Waterman 1920; Wickershan 1896. These sources are com- plemented by data for a number of Nootkan communities on Vancouver Island (e.g., Drucker 1951, 1965; Kenyon 1980; Koppert 1930), and sources that contribute either data or

perspective to Northwest Coast Indian acculturation (e.g., Lewis 1970; Stearns 1981; Suttles 1954). Additionally, a number of topics are discussed in a wide scope of published literature for the Nootkan family of language and cultures (e.g., Drucker 1951; Fleisher 1 9 83*; Jacobs 1964; Koppert 1930; Kenyon 1980; Lewis 1970; Miles 1967; Sapir 1911, 1913; Sapir and Swadesh 1939; Thompson 1976: 377-380). Makah ethnohistory, a summary of historic events recorded by missionaries, traders, explorers, and Indian agents, is described briefly in Colson (1953: 3-24), and Riley (1968: 57-95). These sources are historiographie summaries, and do not attempt a problem-oriented analysis of the acculturation

period. Further abbreviated discussions of Makah ethno-

history are Colson (1967: 212-218) and Günther (1960: 538-540). 2 The Otomi data were collected m June, July, and

August, 1971, under the watchful eye of Professor H. Russell Bernard. Sociolinguistic data from Indonesia were collected in southern Sulawesi, September-October 1983, in my role as

English language advisor for the Eastern Islands Agriculture

Education Project, Washington State University, an A.I.D.

project which is assisting the Association of Eastern Islands Universities in Eastern Indonesia. This example refers to Indonesian colleagues who are educators and administrators in the Eastern Islands Universities. These data establish a succinct, comparative base for the Makah analysis. The Otomi, Buginese, Makassarese, and Torajanese situations

express the common point that these indigenous languages, which are spoken in domestic social settings, were not

supplanted by languages of economically and politically dominant groups, as American English supplanted Makah.

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

412 Mark S. Fleisher

whites and subsequent loss of the Makah lan- guage, their access to the indigenous speech community as a reservoir of cultural information has been shut off to them.

Furthermore, the Makah do not possess a "dual identity" as do the Otomi, Buginese, Makassarese, or Torajanese. The Makah, today, do not have access to their traditional culture or language; these disappeared during their accultu- ration as the number of Makah speakers decreased precipitously, as changing Makah sociocultural attitudes reinforced their social assimilation. Today, the Makah are in the process of recreating and redeveloping a sense of traditional, collective identity from the remains of their past.

In summary, Third World ethnic groups, such as the Otomi and Torajanese, have maintai- ned their languages and avoided the Makah predicament. Fourth World people, such as the Makah, may experience a cultural trap: they find themselves between an irretrievable, traditional culture, and white society where they will not be accepted (see Erikson 1939).

1. Early Contact Period: 1778-1855

Trader John Meares contacted the Makah in late June, 1788. This contact with a British trader was the beginning of Makah acquaintance with non-natives. Russian, French, Spanish, and American traders and explorers roamed this region for decades in search of trade goods and sea otter pelts and other valuable commodities.

Whites did not settle among the Makah during this period except for a brief Spanish entourage at Neah Bay (Babia de Nunez Gaona) in 1792 (February-September). Although whites were occupying gradually more territory in this region of the Northwest Coast (e.g., Vancouver Island, Puget Sound), no attempt was made to settle in Neah Bay until Washington's governor Isaac Stevens signed the Treaty of Neah Bay in 1855 (see table 2).

Until the signing of the Treaty, the Makah Indians did not exist as a unified sociopolitical group. Prior to this, the Cape Flattery Nootkans were identified by their village affiliation: Ba'ada, Dia, Wyacht, Tsuess, and Cape Alava Ozette (Günther 1960: 540; Swan 1869: 2; see map 2).

Table 2 Makah Population, Cape Flattery, 1861-1942

Date Total Population Male/Female

1861 654 1863 663 1865 675 1868 600 1869 526 175/222 1870 558* 271/279 1871 550 1872 604 204/310 1874 422 1875 553 262/291 1876 538 258/280 1877 564 1878 713 1879 724 1880 728 1881 691 1882 701 1883 507 1885 523 1886 523 251/252 1887 533 1888 492** 1889 484 232/252 1890 454 213/241 1891 449 148/173 1893 433 1894 436 1901 413* 1903 740; 422*** 1905 399 1906 410 199/201 1908 408 1909 413 1910 432* 1912 421 103/126 1914 576 199/202 1920 413* 1921 617 217/200 1922 657 217/197 1923 661 1924 672 215/199 1925 617 222/207 1926 660 334/317 1929 654 335/319 1930 422 218/192 1931 413 220/193 1932 412 220/192 1939 411* 1942 357* (410***)

(Sources: Reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs 1854-1947; *Colson 1953:298; **Gunther 1960:540; ***544; according to Tribal records, there were approxima- tely 695 registered Makah in 1982.)

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Acculturation and Narcissism 413

Whether there were social, political, or ritual mechanisms of intervillage unification remains unknown (Günther 1960: 540).

a) Cape Flattery: Language and Society Analyses of the Makah language, or publica-

tion of Makah word lists, appear in a few publications (Densmore 1927; Jacobsen 1967, 1968; Swan 1820: 93-106). Fleisher (1982) and Fleisher and McGuigan (1980) discuss the socio- linguistic history of the Makah in the 19th century, and introduce the possibility that Makah English emerged through pidginization-creoliza- tion processes (for a discussion of Tsimshian English, see Mulder 1982 and Tarpent 1982).3

In the Early Contact (and pre-contact) Peri- od, it is reasonable to assume that members of Cape Flattery local groups spoke natively lan- guages in the Nootkan and Salishan language families. Socioeconomic factors, such as trade, and intergroup marriage, may have contributed to the formation and maintenance of speech net- works (Hymes 1974: 50) among Cape Flattery local groups, contiguous and neighboring Sal- ishan groups (see Günther 1 960 : 540), Nootkans on

Vancouver Island, British Columbia, and Salishan groups located to the east into the Strait of Juan de Fuca (e.g., Victoria, British Columbia; see map 1).

In addition to these languages, the Cape Flattery people spoke Chinook Jargon (Grant 1945; Ho way 1942; Hymes and Hymes 1972; Jacobs 1932; Kaufman 1971; Silverstein 1970). This pre- and early-contact trade pidgin was composed mainly of Chinook and Nootkan vocabulary, and with the arrival of Euroamericans Chinook Jargon incorporated French, Spanish, and English lexical items (Taylor 1981: 175-195).

The Cape Flattery local groups participated in a trading network that extended from the mouth of the Columbia River to Nootka Sound and east into the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Intergroup unity, rivalry, economy, and trading supported language variation on Cape Flattery. Chiefs who were active participants in trading and intergroup sociopolitical affairs may have had speech fields (Hymes 1974: 50) that included Nootkan and Salishan languages, and Chinook Jargon (see Colson 1953: 53).

In the Early Contact Period, speech networks and speech fields of Cape Flattery local group members were broad; in the Middle Contact Period, American English began to replace Chi- nook Jargon as the lingua franca in trading relationships. Cape Flattery local groups were a complex speech community (Hymes 1974: 51; also see Gumperz 1962) that began simplifying its diversity when speech networks reduced in scope during the latter decades of the 1800s.

This reduction in linguistic complexity may have been the accompaniment of the Makah's shift in attitudinal and value orientation from their traditional socioeconomic patterns to the socioeconomic and linguistic patterns of incom- ing whites. As this occurred, contacts among the Makah and regional groups probably began losing economic significance; the languages which were necessary for conducting these transactions gra- dually faded from the speech networks of those individuals who were active in Neah Bay eco- nomics.

b) Nootkan Culture and Society Observations of Makah culture and society

were derived from ethnographic literature (Swan

3 Fleisher (1982) and Fleisher and McGuigan (1980) suggest the pidginization and creolization of American

English by speakers of Makah in Neah Bay, during the decades that followed the signing of the Treaty of Neah Bay. Mintz (1968: 493-494) enumerates and discusses seven historic circumstances that led to creolization in the Carib- bean; six are applicable to this Makah situation (for discus- sions of pidginization and creolization processes see Bicker- ton 1981 ; Decamp 1971 ; Hall 1966; Hymes 1971 ; Weinreich 1953). This genre of language change provides us, today, with a clue as to the intensity of the Makah's emotional response to acculturative pressure. American English began its history on Cape Flattery as a pidgin, an auxiliary contact language that has no native speakers (Bickerton 1981: 2), and

developed into a creole; that is, ". . . any language which was once a pidgin and which subsequently became a native

language" (Bickerton 1981: 2). American English replaced Chinook Jargon as the trade language on Cape Flattery, and as English was pidginized and creolized, it replaced Makah as the native language in Neah Bay. It is necessary to stress that Chinook Jargon was not creolized by the Makah (i.e., it did not become a native language in Neah Bay); it was maintained as a trade pidgin, while American English had became a primary linguistic model for Makah children. The

sociolinguistic history of American English, Chinook Jar- gon, and Makah will provide a barometer of the Makah's

shifting social and psychological alliances (see Herman 1968: 492-511 for a discussion of language changes and preference for group association; also see Hymes 1961: 313-359).

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

414 Mark S. Fleisher

1820), and related literature for Nootkan groups on Vancouver Island (Boas 1891; Drucker 1951; Sapir 1921). In the latter case, it was assumed that patterns ascribed to Vancouver Island Nootkan societies were fundamental characteristics of Nootkan culture and society, and were valid patterns for the Makah. A compilation of these data provided patterns in Makah culture, such as economic, political, and social structure and organization, that were necessary to understand the cultural reactions of the Makah to accultura- tion.

(1) Economic Activity: traditional Makah economy was based primarily on sea mammal hunting (e.g., whaling, sealing) and fishing (e.g., salmon, halibut; see Huelsbeck 1983) and was continued, albeit changed by white influence, throughout the acculturation period.

(2) Class Structure: Makah society was con- stituted of three social classes - chief, commoners, and slaves. Chiefs were the focal point of sub- sistence, economic, political, ceremonial, and social activity of the household group and local group. Households were composed of individuals related through ambilateral descent and shifting residence patterns. Thus, while the central ele- ments of social structure, such as hierarchy of chief statuses, inheritance patterns, village and house location, and subsistence area ownership were permanent, group membership was not fixed. Household chiefs were ranked. The head chief served as the focal point for household members; he was the manager-controller of sub- sistence and ceremonial property possessed by the lineage; and he was the ritual link to the group's mythic history.

(3) Rivalry, competition and warfare occur- red between local groups. Prior to the Treaty of Neah Bay (1855), the Makah Indians did not exist as a unified sociopolitical entity. Four winter villages on Cape Flattery and one on Cape Alava were the principal residences of the people who became the Makah Indians after the signing of the Treaty. Although local groups were autonomous politically and ranked their chiefs internally, interlocal group chiefs were ranked after the unification of local groups.

(4) For members of the chief class, channels for personal expression in a collective, ceremonial setting were available. The potlatch, for example,

was a communal activity among relatives; the principals were the hosts (i.e., chiefs of highest rank) and the potlatch giver. Commonly, children were the honored parties at potlatches, and through the event they received their inheritance, succession to high status titles, rights, preroga- tives, and privileges. The potlatch was an enculturative mechanism, and the dynamic aspect of Makah society when wealth was displayed publically for the purpose of increasing pres- tige.

c) Nootkan Culture and Personality

Jacobs (1964) notes the lack of satisfactory literature concerning mental illness and personali- ty in the early decades of Euroamerican contact among Northwest Coast peoples. There are no specific data concerning Makah personality traits for any period in their history. Today, attempts to reconstruct aboriginal culture and personality patterns and mental illnesses, through the use of protective tests, should not provide reliable data because of extreme changes brought by accultura- tion in many Northwest Coast Indian popula- tions (Jacobs 1964: 49; cf. Spindler and Spindler 1961; also see Barnouw 1950).

A general outline of Northwest Coast personality notes these traits (Barnouw 1963: 337):

. . . despite indications of tension, the main impression is that of a strong ego, ... a suggestion of unsatisfied "oral" dependent needs and indications of masculine feelings of inadequacy, which the individual perhaps seeks to overcome through aggressive, assertive behav- ior. At the same time, there is anxiety about the expression of aggression, and there are strong efforts toward self-control, tending to a compulsive form of adjustment, with some paranoid features.

These traits receive support by Kardiner's (1939) analysis of Kwakiutl culture (Barnouw 1963: 337):

Frustration in Kwakiutl culture probably involves cravings for dependency. This may be significant of the anxiety in regard to being eaten up, and of the outburst of cannibalistic impulses in the possessed youth.

Tension, aggression, oral dependency, mas- culine inadequacy, strong self-control, paranoia are suggested as characteristic traits of Northwest Coast personality (see Dundes 1979; Jacobs 1964; Synder 1975; Whalens 1975, 1981, for further discussion of culture and personality in North-

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Acculturation and Narcissism 415

west Coast cultures). Among the Makah, for example, masculine inadequacy may have been defended against and compensated for, through the aggressive phallic quality of whaling on the open sea.

Drucker's (1951: 322) characterization of an "ideal" Nootkan personality supports several of these general traits:

The ideal personality to the Nootkans was characterized by mildness of temper, lightheartedness, and generosi- ty The truculent, shiftless or niggardly individual was looked down on. Such social disapproval was not expressed except in gossip; however, no attempt was made to force a mild nonconformist into line. People tried to get along with as little friction as possible. Of course, if he went too far, his fellows pointedly avoided him, refused to speak, and in general indicated that his company was not wanted.

Control, generosity, orality, and anxiety over expressing aggression are Northwest Coast personality traits reinforced by Drucker's assess- ment. Drucker's (1965: 155) glimpse into Noot- kan orality mirrors Kardiner's remarks about the Kwakiutl orality: "Despite the richness of natural resources, there was an apparent anxiety about food in Nootkan culture. It is difficult to account for such a pattern."

Unfulfilled needs of oral incorporation in a rich environment may suggest a tendency toward oral dependency and oral aggression. These traits may have been reinforced and exacerbated in the Middle Contact Period: through feelings of loss of attachment to mother when Makah children were forced to attend boarding school (oral dependen- cy); through the replacement of Makah by Amer- ican English (oral aggression); and through the potlatch (unfulfilled oral needs; inability of participants to satisfy the needs of wealth con- sumption and prestige enhancement).

The potlatch celebrated the narcissism of Makah (Nootkan) personality. Controlled ag- gression was the hallmark of the potlatch. Com- petition, rivalry, and generosity in gift distribu- tion meshed in the potlatch; this institution placed an individual, and the group he represented, upon a pedestal during a rite of intensification for local group members (see Jacobs [1964: 50] for a discussion of the Blue Jay myth and its relation- ship to competitiveness).

Direct expressions of traditional Makah cul- ture and personality were discernible in their

responses to white intrusion on Cape Flattery, and in their reactions to acculturative pressure. The Makah accepted readily the intrusion and domination of the whites. If there were Makah attempts to resist violently white control, they were unrecorded. This passivity may have been consequent upon Makah anxiety and reluctance to express aggression, as Swan (1820: 61) notes in this brief passage: ". . . [the Makah] are as wild and treacherous as ever; and, but for the fear of punishment and love of gain, would exterminate every settler that attempted to make his residence among them."

The Makah conformed to white demands. For example, they assimilated easily to dress as whites, accept white economic attitudes and pursuits, and send their children to American English-speaking, day and boarding schools. Col- son (1953: 17-18) notes the Makah's ingenuity at adapting native events to their new community situation; for example, they celebrated potlatches in the guise of birthdays. The Makah adapted well and rapidly to economic and political demands made by the whites.

As white men took greater control over Makah affairs, it was likely that white men began to occupy cognitive and affective positions in the political conceptions, and symbolic life of the Makah. The whites offered new arenas for com- petition, rivalry, and prestige acquisition both among the Makah, and between the whites and the Makah (cf. Colson 1953: 201). This was probably the situation for Makah men who were especially individualistic in their dealings with the white economy, and took advantage of the new situation to increase their prestige (see Linton 1940: 37 for an example of a similar situation among the Puget Sound Puyallup).

The psychological identification that may have existed initially between the Makah and whites critically rested upon the concordance in Makah culture and personality traits, and white demands. The competition and rivalry of eco- nomic activity was familiar to the Cape Flattery people; they had been active in the trading network that existed between the mouth of the Columbia River, Nootka Sound, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, and areas to the east along the Strait of Juan de Fuca (Swan 1869: 30).

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

416 Mark S. Fleisher

2. Middle Contact Period: 1855-1920

The Treaty of Neah Bay (1855) unified five Cape Flattery, Nootkan local groups. A Clallam interpreter present at the Treaty signing called this group, Makahy '"the people who live on a point of land projecting into the sea'" (Swan 1820: 1; also see Colson 1953: 76; Günther 1960: 540). The Makah town of Neah Bay developed from the local group at Dia after the Treaty was signed. The other local groups maintained populations for several decades, though Neah Bay had the highest population (Günther 1960: 540; see table 2).

Colson (1953: 8; emphasis added) identifies an assimilation attitude expressed in the United States Government's position toward Makah acculturation. She writes:

Within the reservation, the most important element affecting . . . [Makah] behaviour was the presence and the demands of the Indian agents. The government itself by its creation of the reservation and the institution of the agency ensured that the Makah would not be faced within their home area with any need to adjust to constant demands from other white groups. At the same time, the Makah, as individuals, lost all right to retain their own customs if these clashed with standards approved by the Indian Service.

Given this attitude of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Colson (1953: 14) reports acculturation patterns in accordance with this policy. For example,

Activities of a ceremonial or ritual nature were discour- aged or prohibited. Any occasion which drew crowds of people for some purpose other than that immediately obvious to and approved by the observer from another society seem to have fallen under suspicion. Potlatches, gambling games, the performance of Indian dances were usually forbidden. The ceremonies of the secret relig- ious and curing societies were first expurgated of features regarded as particularly obnoxious and then banned

Makah adults were permitted traditional liberties* if these did not violate white ideas concerning the proper conduct of the Makah. Changes in life style effected permanent modifications in Makah culture over a few decades.

Whites restructed and reorganized Makah society: they introduced concepts of property, labor, and jurisprudence; they disregarded the traditional Makah political hierarchy (see Druk- ker 1951, 1965); they ignored class and status differences, even of slaves; and they imposed

western, legal procedures such as courts, jail, and police.

Within a several decades of the enactment of the Treaty of Neah Bay in 1863, changes occurred throughout Makah culture (e.g., single family houses were used by the 1880s). Swan's (1820) descriptions provide an opportunity to gaze into areas of Makah lifestyle:

(1) Festivals occur seldomly and are confined to power (ta-ma'-na-was) ceremonies (p. 13);

(2) children play white children's games that were observed in Victoria, British Columbia, or elsewhere along the Strait of Juan de Fuca (p. H);

(3) nearly all the people have white-style clothing (p. 15), and young women dress in calico gowns (p. 16);

(4) whaling is no longer a successful sub- sistence pursuit (p. 22; see also Ruby and Brown 1981: 179);

(5) Makah diet relies heavily on white pro- ducts (e.g., flour, rice, sugar, molasses, pp. 23-24);

(6) traditional Makah culinary items have been replaced by white objects (e.g., pots, kettles, pans; p. 25);

(7) Makah ". . . readily learn the songs of the white men, particularly the popular negro melo- dies" (p. 49).

Acculturation was proceeding quickly by the 1860s, and was affecting elders and adults by banning rituals, by changing subsistence practi- ces, and by altering community economics.

Socioeconomic and political changes in Makah society were reinforced through the estab- lishment of a day school, in 1864, by Agent James Swan. Although a day school facilitated the formal education of Makah children, introduced them to an American way of life, and American English, an Indian agent at Neah Bay decided that Makah children were being influenced too strong- ly by older relatives during nonschool hours. As a means of completing the isolation of Makah children from their relatives, a boarding school was established in 1874.

The intense pressure to assimilate originated first with Neah Bay's Indian agents; but as the years progressed, the pressure to assimilate was probably generated by the Makah themselves, as an expression of their rivalrous and competitive

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Acculturation and Narcissism 417

temperaments set in a social environment trans- formed by acculturation.

a) Language Replacement

Indian agents reflected the policy of the Bureau of Indian Affairs which was the total assimilation of the Indian population into white society. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs knew the importance of teaching English to Indians, if his goal of total assimilation was to be fulfilled. In 1887 (Reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs: xxiii), he wrote that:

This [English] language ... is good enough for a white man and a black man, [and] ought to be good enough for the red man teaching an Indian youth in his own barbarous dialect is a positive detriment to him. The first step . . . toward civilization, ... is to teach them the English language.

Teaching English to the Makah was especially important in their westernization process; this is documented in a statement by Agent Huntington (Reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs 1874: 333):

... I shall make it my first endeavor to teach them to speak the English language ... by the usage of common parlance. The Indian tongue must be put to silence and nothing but English allowed in all social intercourse.

By the end of the 1 800s, Huntington^ goal of creating English-speaking, Makah Indians neared fruition; for example, in 1897, 59.2% Makah residing in Neah Bay spoke English (see table 3). This is significant as a barometer of the effective- ness of language replacement as a linguistic and psychological phenomenon (see Williams 1983: 353-396); the rapidity of English language learn- ing by the Makah, suggests that English had taken on social and economic importance, and may have become a channel of expressing a sense of identity with the whites.

Agent Huntington, founder of the boarding school, emphasized the role of English in Makah education; in 1878, Huntington reported that all school instruction was conducted in English. He emphasized the seriousness of formal education to Makah parents; for example, in 1877, he ordered the imprisonment of a Makah parent for not surrendering a child to the boarding school. By 1882, Agent Willoughby noted that parents were eager to send their children to school; however,

Table 3 Measures of Acculturation, Neah Bay, 1876-1897

Date Total Makah Dressed in Makah Who Population White Clothes Spoke English

1876 538 100 1877 564 100 1878 713 100 1879a 724 509 1882b 701 120 1885e 523 500 115 1887e 533 420 112 1888 492 135 1889 484 110 1890 454 147 1891e 449 419 130 1893f 433 417 135 18948 436 436 140 1897h 422 420 250

a Doctor began practicing in Neah Bay. b Agent began weekly "morals" lectures in Indian lodges; Washington Episcopal Society was providing teaching materials for religion. c Many Makah were living in frame houses, and used furniture and sewing machines (in 1875, there were 73 lodges and 5 houses). ** There were five female missionaries in Neah Bay; many people were picking hops in Olympia in summer; 11 people were employed in school; old people poked fun at children who finished school.

e There were 25 fishing boats in Neah Bay; whites controlled four/five schooners, Makah had three schoo- ners.

* By 1892, a steamer made two trips weekly from Tacoma to Neah Bay for fish; Makah owned two stores and a hotel; Makah owned seven schooners.

8 Makah owned eight schooners; alcohol consumption increased.

h 1905 - men, women, and children traveled frequently to Tacoma to pick hops; women were making baskets for sale; 1906 - most Ozette Indians lived in Neah Bay, and the children attended school; 1908 - gasoline engine used on fishing boats. (Source: Reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs 1854-1947.)

some Makah families resisted passively and fled to Ozette.

Even the distant Makah families living on the Ozette Reservation accepted the school decree by 1900, and moved to Neah Bay to comply with white demands. In the 1895, the boarding-school was closed (Colson 1953: 19; cf. Günther 1960: 540); Makah children attended the Neah Bay day school (see table 4), or traveled to a large boarding school which served different Indian groups.

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

418 Mark S. Fleisher

Table 4 Makah Enrollment and Literacy in Neah Bay Schools

Date School Age Student Student Children Enrollment Literacy

1865 78 1869 149 1871 16 1872 20 1875 22 11 1876 25 1877 50 20 1878 225 40 25 1879 225 34 33 1880 370 69 37 1881 251 70 66 1882 66 1883 58 1884 82 59 1855 136 105 1886 76 51 1887 83 75 1888 102 1889 76 72 1890 69 76 1891 60 58 90 1892 64 1893 106 1894 115 1906 90 1908 66 1911 58 1912 129 1914 175 60 1921 169 129 1922 169 106 1923 178 106 1924 181 56 1925 188 82 1926 273 90 1929 113 49 1930 45 1931 125 53 1932 121

(Source: Reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs 1854-1947.)

Traditional Indian education in a domestic setting, and white education in a community setting joined the entrepreneurial activities of Makah men; for example, by 1900, Makah em- ployed whites on sealing vessels (Ruby and Browh 1981: 179). Some Makah parents reinfor- ced the white education of their children when

they transformed education into a "cash crop" (Swan 1820: 33):

[The Makah] are so accustomed to trade with white people and to receive gifts, that they will neither perform labor, however trivial, nor part with the least article of property, without exacting payment. They carried this practice so far as to demand compensation for allowing their children to attend the reservation school.

The rapid loss of the Makah language is a key analytic variable in establishing the intensity of Indian-white relations in Neah Bay. Learning and using English was more than an accommodating behavioral gesture by the Makah; it was a means of avoiding open confrontation with whites, and symbolized the growing dominance of white cultural practices in the Makah conceptual system.

As Makah became proficient in English usage, they assumed active roles in their community's socioeconomic affairs; however, Makah who could not speak English, were unable to partici- pate in new economic opportunities (see table 4). The Makah's language learning achievement may have been motivated by their need to compete with whites, and their need to compensate for cultural and linguistic losses in their traditional culture. In learning to control English as a resource in their social environment, they may have been able to create a sense of self-control.

Establishing the relationship between com- munity values, social situations, and language choice, is the basis for understanding the social and psychological roles that language plays in a speech community (Fishman et al 1971 : 566-574). Language choice may vary as new social situations result from changes in community values. As American English became accessible to the Makah through classroom and economic situations, it reinforced the likelihood of Makah participation in the changing economy, especially for upper class and highly individualistic men.

The traditional Nootkan values of rivalry and competition that led to wealth and prestige enhancement were reinforcing motives to pursue English language learning. A contrast may have been established between the traditional values of Makah who remained in a "conservative" domes- tic setting, and values of "progressive" Makah who acted in socioeconomic activities that requi-

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Acculturation and Narcissism 419

red the use of American English. As rewards were gained for participating in the white economic system, American English became rooted in the community.

The acquisition of English provided opportu- nities in the acculturating Makah society. Eventu- ally, however, these advantages were counterba- lanced by the loss of traditional Makah symbols of group unity and self-cohesion, such as language and the spirit quest for men. By the 1920s, the impact of these losses was marked by the initia- tion of Makah Day, a public event commemor- ating the "old" culture.

b) Cultural Discontinuity Cultural discontinuity refers to the cross-

generational loss of traditional Makah values, attitudes, and language as a consequence of acculturation. The formation of schools with enforced student attendance, the obligatory use of American English, the banning of native religious activities, and modifications in political dynamics engendered cultural discontinuity among the Makah.

Cultural discontinuity was characterized by diminished fathers' and mothers' roles in the enculturation of their children. Makah fathers were enticed away from the domestic environ- ment by whaling schooners and trading opportu- nities which promised material rewards; conse- quently fathers played a less important role in the enculturation of their children.

Formal education disrupted the Makah's tra- ditional enculturation pattern; children's social and psychological needs were satisfied through nontraditional patterns.4 Makah mothers relin-

quished their children to the schools, and children were isolated from adults in Neah Bay (see Sunley 1955: 162 for a discussion of mid- 19th century schools and teachers, in the United States, func- tioning as parental surrogates). As the school teachers' role began to accept more of the burden for Makah enculturation, the mothers role may have lessened in importance as a role model.

Although separation from parents, particular- ly separation from mother has had lasting effects, children in the cultural discontinuity stage, partic- ularly in its later decades, were compensated for their 'mother loss' by exposure to alternate forms of psychological rewards. Their school gave them needed attention, rewards in material objects, surrogate mother-figures, and a group of peers with whom to identify; in this way, thwarted developmental needs were satisfied partially by teachers and friends in the school environment.

Cultural discontinuity effected by conflic- ting, enculturation, and linguistic models presen- ted a confused picture to Makah youth; their community was in cultural and linguistic flux, and their roles as Makah men and women were probably unclearly defined; ambivalence toward the "old" Makah culture, and ambiguity in their daily lives may have been characteristic of genera- tions of Makah youth who were caught between cultural systems.

The participation of Makah adults in the acculturating economy reinforced the quasi-white education of Makah children, especially for boys who recognized the material advantages brought through education. As language ability was sym- bolically equated with the accumulation of pro- perty, high status, and prestige, in the personal view of Makah school boys, learning American English became an essential educational re- source.

Makah school girls experienced a different social fate, as their roles in the acculturating Makah society were re-oriented toward Euro- american domestic patterns. Elderly Makah

4 Although no descriptions are available that might provide us insight into a Makah school child's view of white education, Ford (1968: 88-90; emphasis in original) provides a glimpse into the formal childhood educational experience of a Kwakiutl chief attended an Agency school at Alert Bay, British Columbia, in 1887: "When I came here to Alert Bay, when I was six or seven, to school, it was pretty hard on me While I was in school the first week, they tried to teach me how to write and spell, but I couldn't do anything for I didn't want to learn The Indian agent . . . came in to see the children in school, and took our measurements and ordered for the clothing. That made me feel better. The Indian agent says if I be a good boy in school he will buy me clothes every year Mr. Hall got all the children in a row and begin to make us spell the things that we have learned -

He says to spell yes and no and all those little words and then he gets to the other side where I was and asked them to spell said. None of the others could spell it, but I says I can and I spelled it out SAID. The Indian agent and my brother clapped their hands. Oh, I felt proud, and from that time, about two months after I came, I tried to do better than all the others."

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

420 Mark S. Fleisher

reported that missionaries, in the early 20th century, prevented Makah men from performing "women's tasks," such as clothes mending, and discouraged women from performing subsistence activities, such as shellfish gathering.

Acquiring skills in American English was less important to them, since these linguistic skills would not have brought to them benefits similar to those of Makah men. Thus in spite of enforced assimilation plans, Makah women maintained conservative attitudes and values; however, "pro- gressive" Makah women were able to acquire white property, such as household goods and personal attire, and thereby participate in the acquisition of property and prestige, though less elaborately than men.

Children born into Makah families were confronted with appositional enculturation mod- els; "conservative" attitudes and values were expressed from older people, "progressive" views from parental-age adults, and the "new" approach expressed by whites. As the years of the Middle Contact Period moved toward 1920, the trend was to adopt more "progressive" views.

This enculturative situation should have left a lasting impression. A contemporary (1940s- 1980s), cross-generational sample of Makah atti- tudes and opinions toward, for example, the loss of traditional Makah culture and language, should demonstrate that acculturation was experienced differently throughout the Middle Contact Peri- od. It is predicted that Makah who experienced formal boarding school education in the 1870s, and especially in the 1880s and 1890s, should be least affected, and continue to maintain tradition- al, conservative attitudes. The generation reared in the early 20th century should express a conservative view, though less traditional than their immediate predecessors. Subsequent genera- tions of Makah children, those born after 1910, should have experienced "progressive" attitudes and values in Neah Bay, and the common use of American English; they should express the least traditional point of view (see 3.b Cultural Adjust- ment).

Cultural discontinuity led to the disintegra- tion of traditional Makah social and ideological systems; this led to the failure of Makah people to develop a sense of self-love and self- worth. In an effort to restore the self, Makah have been

motivated to seek satisfaction of personal needs through material means, as in the grandiose accumulation of potlatch property. Although assimilation plans enacted through day and boar- ding schools were principal foci for cultural and psychological change, whites served the Makah psychologically by providing them with the objects they required to satisfy their changing identities; this was witnessed by the Makah's decathexis of Indian objects, and recathexis of white self-objects.

c) Narcissism

As the cultural discontinuity stage progres- sed, Makah children were being reared in conflic- ting and confusing environments. An inadequate development of the self may have resulted from the absence of both an idealized parent, and stable cultural institutions to mirror in appropriate developmental stages. Their confusion of personal and communal identity, and feelings of anomie and worthlessness, have remained in the group as a narcissistic legacy of Makah childhood experien- ces in the Middle Contact Period (see DeMause 1974, 1975, 1982; Erikson 1963; Freud 1961: 69; Kohut and Seitz 1978).

Narcissistic behavior, culturally uncontrolled expressions of self-aggrandizement and object idealization, occurred within an acculturated, sociopolitical structure and organization. Tradi- tional Nootkan local groups were leader-orien- ted: their chiefs provided economic, social, and ceremonial direction; and acting as the group's ego-ideal, they may have provided individuals with a means to identify with the group (Freud 1955). During the Middle Contact Period, whites imposed a quasi-egalitarian, sociopolitical organi- zation. They did not recognize the Makah's traditional, political hierarchy, social class struc- ture, and ideology; for example, they considered slaves as the social equals of commoners and chiefs. This effected the "leaderless group," which had negative psychological consequences for the Makah.

Initially, the "leaderless" Makah group, attempted to maintain group cohesion by identi- fying with whites who controlled the schools, influenced the economy, and permeated Makah ideology with their own attitudes and values. This defense kept the Makah from feeling the depriva-

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Acculturation and Narcissism 421

tion of losing their traditional symbols, such as religious rituals, mythology, and language; also, it strengthened their desire "to be like" whites through, for example, the decathexis of Indian objects. Additionally, the "leaderless" group al- lowed an expression of needs in the absence of a stratified, sociopolitical structure that was linked to an idealized leader and lineage (see Gehrie 1980: 376-382).

By the end of the cultural discontinuity stage, the Makah had lost fundamental elements of their culture and its psychological orientation. They had shifted from a domestic organization, with culturally-syntonic ritual settings for expressing one's narcissistic grandeur, to a community of individuals who were expressing narcissistic needs outside of traditional ritual settings.

The initiation of Makah Day, around 1920, was group compensation for this shift in cultural and psychosocial orientation. Makah Day permit- ted community regression to a period of cultural and psychosocial history when group cohesion and harmony mirrored the cohesion and harmony felt by individuals. Makah Day was, and still remains, an emotional, creative effort to restore self-cohesion and harmony (see Gehrie 1980: 371).

By 1920, the Makah persona was dependent, and lacked a strong sense of self-cohesion. These qualities were reinforced throughout the Late Contact Period by the following double bind (Bateson et al 1956: 251-264; also see Colson 1953: 3). White acculturative pressure had van- quished Makah cultural institutions; their sym- bols of cultural integration, social and cognitive systems, and affective patterns had been vanishing for decades; the assimilation goals established by Indian agents were being accomplished, yet whites were not able psychologically to accept the Makah as people unstigmatized in their commu- nities. The Makah were trapped by their inability to return to the conditions of their traditional culture and were unable also to enter into white American communities, as the whites had encour- aged and prepared them to do.

Acculturation has aggravated Makah narcis- sism, and has led them to a narcissistic dilemma: Makah narcissistic needs can not be met either through traditional channels of expression or through ego-syntonic and culturally-syntonic

mechanisms in their community today. The cul- turally uncontrolled expression of narcissists is evident: the traditional pattern of grandiose pro- perty accumulation continues; however, it occurs outside of the ritual context of the potlatch. For example, stereos, televisions, cars, and expensive vacations are "accumulated and displayed" as expressions of self-worth. The compensatory effect of these activities is apparent against the background of poverty in the community.

3. Late Contact Period: 1920-1982

a) American English The consequences of language acculturation

during the Middle Contact Period were discern- ible in this stage. Densmore (1939) and Ernst (1952) observed the common use of English in the 1920s and 1930s, respectively. By the beginning of the 1940s, almost all Makah spoke and understood American English. Only a few old people lacked a knowledge of American English; Makah who were 20-30 years of age distorted spoken Makah, and only elderly Makah could understand their speech. Makah who were over 40 years of age were ridiculed by the elders for speaking a simplified Makah (Colson 1953: 54, 1967; see Osborn 1970: 232-233 for a discussion of the significance of American English language assimi- lation among American Indians). By 1941-1942, American English was the dominant language in Neah Bay.

b) Cultural Adjustment Several post- 1920 events occurred that affec-

ted the Makah adjustment to their changing community.

(1) The opening of Route 112, in 1933, was the most significant event in this decade. The road facilitated the westernization process: it opened an avenue for continued white influences in Neah Bay; and permitted easier access for the Makah to the outside world. Neah Bay's isolation, before the opening of Route 112, obtained symbolic significance for the Makah; the "pre-road" era became a time of nostalgic remembrances for older Makahs (Colson 1953: 46-48).

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

422 Mark S. Fleisher

(2) The Neah Bay high school was built in 1932, and staffed with white high school teachers (see Fleisher 1982 for a discussion of the implica- tions of using American English as the principal medium of communication in American Indian education). Until the school opened, Makah students were sent to Chemawa, an Indian boar- ding school in Oregon (Günther 1960: 541). This school, and a white hospital for Indians, were treated symbolically by the Makah. Colson (1953: 134-135) notes that ". . . Cushman Hospital and the Indian boarding schools . . . [were referred to] as 'our Indian hospital' and 'our Indian schools'." This suggests a continuation of white object cathexis that began decades earlier.

(3) The United States Government granted citizenship to American Indians in 1924. The Indian Reorganization Act (1934) gave to Indians a voice in their own affairs: "The new policy of the Indian Service was to encourage Indians to improve their economic position and to learn new techniques and goals, but there was to be no further indiscriminate outlawing of customs sim- ply because they were different from those known to the whites. The Indians were also given a voice in their own affairs and were consulted on matters involving them" (Colson 1953: 22-23).

The Makah took advantage of this; they organized a tribal council and wrote a tribal constitution. The Commissioner's (1931: 6-7) report suggested that Indians be allowed to adapt without extensive losses in native culture; howev- er, by this time in Neah Bay, the native culture and language were beyond resuscitation.

Since 1855, the Makah have been losing their native language and traditional customs. The acculturation process seems to have affected all areas of their traditional lifestyle. The Makah's weakened self-concept and group unity are expressed in their effort to define themselves legally, through a selection of objective, political, rather than cultural, or affect-laden, qualities. Colson (1953: 61-62) notes:

The Makah conception of the common ties which bind them, a heterogeneous assemblage of people, into one common body is not based on culture, or on the strength of social interaction between individuals, or on heredity, or on residence on the reservation. The people regarded as Makah, by themselves and by those who are not of their group, are such by a political definition

framed to organize a group of people with political rights as members of the Makah Tribe.

In the 1940s, the Makah mechanism for establishing a sense of collective unity was devoid of native cultural and linguistic significance (Col- son 1953: 87); however, it is significant psychol- ogically that the Makah resorted to the objectivity of the white law, rather than the subjectivity of traditional, domestic-oriented culture to restore and maintain Makah group cohesion.

Colson (1967: 221-222) emphasizes that the Makah" . . . clung not only to their reservation but also to their status as wards of the Govern- ment While they resented the status in many ways, none would have shouted louder if any attempt had been made to change it." The dependency on the reservation provided them with a sense of belonging and became a visible locus for community activities. Establishing a sense of community by sharing a common terri- tory was a principle of traditional Nootkan culture (Drucker 1951), and remained vital, albeit covert, in the Makah's definition of community membership.

The reservation served the Makah as they exerted control in their power struggle with white society: the reservation was a place to hide from outside responsibilities, such as defaulting on credit payment (Colson 1967: 222); to seek refuge while being pursued by law enforcement officials (Fleisher 1983); the reservation may have aided Makah men to cope with feelings of male inade- quacy in an acculturated situation devoid of aboriginal, expressive mechanisms;5 and the sta- tus of 'reservation Indian' was used as a legal weapon by the Makah as they argued that the

5 American Indian convicts comment that the "outlaw trail" is their substitute for the "war path." Also, two Makah in the Washington State Penitentiary, Walla Walla, Washing- ton, are members of a Sweat House religious group, with whom I have been conducting research for the past eight months. The Sweat House religion is a revitalistic movement that has its origin in penitentiaries in the western United States (e.g., Oregon, Washington, Nevada). To my knowl- edge, there are no published studies of the effects of this movement on American Indians who reside on reservations. Sweat House participants leave prison, and establish, or join on-going, Sweat House movements. The Sweat House doctrine emphasis spirituality and brotherhood among In- dian peoples, and achieving a sense of inner harmony and peace.

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Acculturation and Narcissism 423

United States Government had". . . robbed them of their lands and possessions and had destroyed their old culture" (Colson 1967: 222).

These examples illustrate that the Makah's reaction to acculturative pressures was consistent with their traditional pattern of avoiding direct confrontation. Their security on the reservation, and acrimonious judgements against the whites belied a sense of insecurity, and dependency.

During the cultural adjustment stage, the group persona of the Makah was conflicting, confused, and disharmonious. Cross-generational attitudes among elders, adults, and young adults showed contrasting attitudes and values engen- dered by discontinuity in the Middle Contact Period. It was suggested in 2.b Cultural Discon- tinuity, that the first generations to experience the planned assimilation of the whites should have maintained conservative lifestyles. Makah who were born later should have expressed "progres- sive" views, introduced by formal education, American English, and changes in the Makah conceptual system. Narcissistic traits should be discernible in the Late Contact Period.

Colson's (1953) and Miller's (1952) data support the hypothesis that links formal educa- tion and the dominance of American English to cultural discontinuity and the exacerbation of narcissistic traits in the Makah character. Colson (1953: 128-129) reports that individuals expressed contrasting views toward Makah cultural and linguistic losses: there were Makah who felt a personal loss with the disappearance of traditional Makah culture; those who identified with whites because it symbolized parity in status and pres- tige; and young Makah who rebelled against traditional values and attitudes. In the latter case, a young woman". . . snapped out: cMy father still wants to boss me. That's because he always * listened to what his father said even when he was old. But they've got to get used to us modern young people'" (Colson 1953: 128, emphasis added; cf. p. 181).

Miller (1952: 267-272) divides the 1949 Makah population into four generations that expressed contrasting attitudes and values. Mil- ler's data are organized below in the framework of Makah acculturation proposed here.

(1) Middle Contact Period, Group I, 60+ years of age, born before 1889: many escaped

white education, and were closely tied to tradi- tional patterns; for example, men in this age grade were the last to practice traditional sealing and whale hunting, and the last to seek power, while women were the last to undergo life crisis rites; there were fewer than 12 alive.

(2) Middle Contact Period, Group II y 40-60 years of age, born between 1889-1909: these people attended the Ba'ada boarding school; they were influenced by their parents and whites; white influence was stronger than it was for their parents; women learned white cooking and housekeeping techniques; they were bilingual and conversed easily in Makah and English; religious syncretism emerged as native concepts (e.g., seeking power) merged with Christian ideology.

(3) Late Contact Period, Group III, 20-40 years of age, born between 1909-1929: this was the "lost generation"; they received little Makah culture and were pulled strongly toward white society.; as a group they sought identification with whites in values, language, and religion; they expressed antipathy toward "Indian ways"; they choose to speak only English except under extraordinary conditions; they tried to "america- nize" their parents; many drank excessively; some compensate for having lived as whites by rever- ting to traditional Makah patterns.

(4) Late Contact Period, Group IV, under 20 years of age, born 1929-1949: they sought security, more so than their parents, in nonwhite patterns; many efforts were overly aggressive responses toward whites; the bone game was common; in 1949 youths requested Tribal Coun- cil permission to use the community hall for classes in Makah culture and language; people sometimes emulate traditional patterns (e.g., boys bathing in cold sea or river water), though the meaning of their behavior is unclear; girls feel strong attraction to white culture, and they are escorted frequently by white military men.

Data for Group I are limited by few people. As I suggested, these people maintained a conser- vative world view throughout their lives, having been able to avoid formal education. Groups II, III, IV showed the effects of sociocultural, lingu- istic and psychological amalgamation with whites. Bilingualism and syncretism in Groups II and III, and the antipathy to "Indian ways" in Group III, showed the social and cultural effects of accultu-

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

424

ration, and the infusion of white hostility toward "anything Indian" into the Makah concept of self (see Sherwood 1980).

After 1920, Colson's (1953) and Miller's (1952) data show a lack of consistency in Makah attitudes toward being Indian. Old people were traditional and conservative as they knew no other way; young people in the 1940s, and young people in the 1970s and 1980s, were ambivalent toward their Indian heritage; cultural discontinu- ity in the Middle Contact Period had the psychol- ogical consequences of creating poor self-images, personal disharmony, and discontent in their ancestors, that had been transmitted, presumably, through the parent-child relationship (see DeMause 1974, 1975, 1982).

Poor self-images, personal disharmony, and discontent were qualities of Makah personality that became apparent in Group IV; they regressed to their conception of traditional cultural pat- terns, such as relearning Makah language and culture, ritual bathing, aloeit absent of traditional cultural and psychological meaning.

Patterns in cultural personae were expressed cross-generationally: a white cultural orientation in one generation was compensated by an Indian orientation in next generation. This was paralleled by personal, aesthetic preferences within an age grade to "become Indian." Today, Makah pursue the restoration of native linguistic and cultural traditions, while others engage in white activities with no interest in Indian heritage.

The cultural adjustment stage began with the introjection of white characteristics seen, for example, in the cathexis of white personal and household objects. This was followed by a com- pensating aversion to white society, and hyperca- thexis of Indian objects and activities, such as quasi-ritual bathing. A balance of both white and Indian objects, and attitudes was expressed in activities such as the Makah program for the revitalization of traditional culture and language, Makah Day, and community support of the tourist industry. c) Psychological Adjustment

Psychological disharmony shrouded the Makah's entrance into the Late Contact Period: Makah Day emerged as group compensation for cultural disintegration; individuals who felt disin-

Mark S. Fleisher

tegrated psychologically defended themselves by arguing that their loss of traditional lifestyle was a sign of being "civilized," a trait for which the Makah were now claiming prestige (Colson 1953: 127); Makah personal names were considered unimportant or were forgotten; gratuitous claims were made to upper-class, social group member- ship; and the individual-oriented potlatch (cf. Colson 1953: 215) emerged as an expression of self-aggrandizement.6

Makah Day compensated the group for cultural and linguistic losses. The comfort of returning to a less troublesome time was balanced by an existential crisis. Under the positive sanc- tion of the Indian Reorganization Act (1934), the Makah became autonomous and independent. Their ensuing separation from white society was anxiety provoking. The Makah coped with their autonomy by retreating behind the mask of "reservation Indian," and then proclaimed inde- pendence from white society.

This expression of independence belies their dependency on whites, which was established during the Middle Contact Period. When accultu- ration began, the Makah were an aboriginal group that was autonomous and independent. As whites served the Makah through formal education and economic channels, they became dependent on American politics, economy, and American Eng- lish (see Colson 1953: 154). The Makah became dependent on American culture for satisfying their material, social, and emotional needs, as in, for example, the incorporation of white goods in

6 Colson (1953: 215) argues that: "When the whites entered the area and opened new sources of wealth to the Makah, it became possible for men and women to obtain large supplies of goods by their own efforts. They began to hold potlatches, whether or not they had any large numbers of followers to help them, and to demand the right to use family ceremonial prerogatives. The old aristocrats were furious but helpless in this situation, and many people began to compete for status." The access to property, alone, does not explain the change in attitudes and values that necessarily preceded a salient shift in potlatch orientation, such as the one described by Colson. The expression of narcissistic behavior through the Makah's acculturated, sociopolitical system does explain the use of possessions in ways that would have been culturally-dystonic in traditional Makah culture. In this way, an individual's need for grandiosity gains expression in a sociocultural setting that is powerless to inhibit its emergence (Gehrie 1980: 370).

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Acculturation and Narcissism 425

the potlatch, and Euroamerican religious expres- sion.

The reservation relieved Makah anxiety and tension by giving them the autonomy to proclaim their freedom from white influences, although they remained dependent on Euroamerican poli- tical-economy. Ironically, the fault in the white assimilation plan for the Makah Indians rested on the double bind this situation created. White resistance to accepting Makah without stigmatiza- tion prevented Makah people from leaving the domestic structure of the Makah culture and entering into white society. In essence, the whites reared generations of Makah people as quasi- whites, and then failed to give them their autono- my and independence.

If the Makah psychosocial adjustment to the advance of white society was positive, they should have expressed a positive view of themselves, their community, and the outside world; however, this was not to be seen, today, in Neah Bay. The Makah economic adjustment was positive; however, damaging effects occurred to the Makah family, and self-concept: diffuse hostility, resent- ment, anger, and suspicion are expressions of maladjustment. Whites had control of economic, political, and enculturative mechanisms. The Makah tendency to control aggression and need to avoid open confrontation engendered them powerless to act in their own behalf.

The Makah adjusted to life on the margin of white society in an uneventful fashion, until the inception of the Ozette Archaeological Project, which was under the direction of Professor Richard D. Daughtery, Washington State Univer- sity. From 1970-1981, year-round excavations brought the attention of international scientific and public communities to Cape Alava, and Neah Bay.

The Makah have benefitted from the attention afforded them as they were transported symboli- cally from the margin of the white world to center stage; scientific publications, newspapers, and magazine articles brought television and radio coverage to this isolated area. Through these

public channels of communication, the Makah entered white society as holders of high status and were accorded prestige by white spectators. Fed- eral funding sources provided money for the construction of the Makah Cultural and Research

Center at Neah Bay, which houses magnificent displays of Ozette artifacts and vistas of the Cape Alava area.

The Ozette site and the Makah Museum have become the center of history for the descendants of Cape Flattery and Ozette local groups who were united by the Treaty of Neah Bay. Ozette archaeology legitimized Makah history. It provi- ded the "Cape People" (Swan 1820: 1) with a sense of social acceptance in the white world, and in this sense, the Ozette Archaeological Project partially released the Makah from their double bind. As a psychological construct, Ozette repre- sented a regression to, and white acceptance of, an aboriginal lifestyle; it is compensation for assimi- lation into white society; and it permitted the Makah to accumulate wealth, raise their status, and gain prestige in a quasi-traditional Northwest Coast cultural pattern.

Sociologically, Ozette provided work oppor- tunities for Makah youth, training in anthropol- ogy and archaeology, and functioned as a rite of intensification for the Makah community. Ozette filled a void in Makah psychosocial history as it compensated materially for cultural and linguistic losses which occurred since 1855. In the ethnohis- tory of the Cape Flattery and Cape Alava people, the Ozettes were the most distant local group affected by the Treaty of Neah Bay, and the final people to move into Neah Bay. As the last local group to succumb to acculturation, they function, today, as an appropriate symbol of community and self-cohesion.

The Makah have regained aspects of their sociocultural history, and are developing self- respect and identity by means of Ozette, a language and culture revitalization program, and their museum; however, they remain without cultural mechanisms for coping with personality problems and deviance. The loss of traditional cultural mechanisms for handling mental aberra- tion, and the absence of appropriate alternatives, is the damaging legacy of acculturation.

Community mental health is a sensitive* issue in Neah Bay. The Makah community must yet

[ respond by developing effective mechanisms to [ assist their members in struggles with alcoholism,

family abuse, uncontrolled violence and aggres- ; sion that has led Makah men into Washington i State's Correctional System (see Devereux 1980;

Anthropos 79.1984

This content downloaded from 129.22.79.194 on Fri, 8 Nov 2013 16:58:49 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

426 Mark S. Fleisher

also see Stein 1982: 355-377 for an analysis of alcoholism as social metaphor, which is analogous to the discussion of Makah dependency expressed through their reservation).

By eliminating native conceptual, expressive, and domestic systems for resolving personal distress and mental illness, acculturation aggrav- ated traditional culture and personality traits, personality abnormalities, and community mental health problems, which may have been frequent community problems in aboriginal times (Jacobs 1964). The Makah lack culturally-syntonic mechanisms for expressing mental aberration; for example, shamanic cures and spirit possession are not viable options. Yet, there have been no replacements for these psychocultural losses.

Traditional Nootkan culture and personality patterns for expressing distress and anger are indirect and covert. After white intrusion on Cape Flattery, the emotional difficulties experienced by Makah families may not have been acted out in the Middle Contact or Late Contact Period. It is plausible to link community mental health prob- lems, today, to the sociocultural discontinuity and linguistic assimilation of the Makah. Whites sanctioned negatively Makah expressive systems, such as the use of shamans, and religious ceremo- nies; this engendered the breakdown of native social structure. Native mythological systems have disappeared, thus not to assist in the resolu- tion of mental difficulties through protective channels (Jacobs 1964). Cultural systems for ameliorating distress, tension, and anxiety were removed from the Makah's traditional mecha- nisms for handling mental health problems, and were not replaced with adequate substitutes.

Mechanisms for coping with mental health problems have not emerged from the social and psychological interactions among Makah today. Contemporary Makah culture, society, and per- sonality is the amalgamation of aboriginal Noot- kan conceptual and personality systems, modified and reinforced by attitudes and values of Amer- ican culture, facilitated by American English.

Summary

Makah acculturation proceeded as a course of restoration and maintenance of self-cohesion. During the Middle Contact Period, self-cohesion

was maintained through a projective identifica- tion with the incoming whites and white culture (e.g., cathexis of white objects); self-cohesion was maintained by incorporating elements of white culture into the Makah culture. The incorporation of white attitudes, values, and American English contributed to the development of contrasting enculturative conceptual models, which were encountered by Makah children during the latter half of the 19th and, early decades of the 20th century.

Generations of Makah youth were reared in the environment of sociocultural and linguistic inconsistency; this resulted in feelings of anomie, anxiety, and disharmony. Moreover, white racist ideas concerning the baseness of Indian culture were incorporated into the Makah's enculturative conceptual system through the formal education of Makah children in schools operated by whites.