Experiences of Complaints about Counselling, Psychotherapy ...

Looking at the Psychotherapy Process as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making: A Case Study...

Transcript of Looking at the Psychotherapy Process as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making: A Case Study...

Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 23: 195–230, 2010Copyright C⃝ Taylor & Francis Group, LLCISSN: 1072-0537 print / 1521-0650 onlineDOI: 10.1080/10720531003765981

LOOKING AT THE PSYCHOTHERAPY PROCESS AS ANINTERSUBJECTIVE DYNAMIC OF MEANING-MAKING:

A CASE STUDY WITH DISCOURSE FLOW ANALYSIS

SERGIO SALVATOREUniversity of Salento, Lecce, Italy

OMAR GELOUniversity of Salento, Lecce, Italy, and Sigmund Freud University,

Vienna, Austria

ALESSANDRO GENNARO, STEFANO MANZO, and AHMED AL RADAIDEHUniversity of Salento, Lecce, Italy

This work presents a dialogic model of psychotherapy (the Two-Stage SemioticModel, TSSM) with discourse flow analysis (DFA) and a low-inferential methodof analysis based on it. TSSM claims that in good-outcome psychotherapy, thepatient’s system of meanings follows a U-shaped trend: First, it decreases, andthen the dialog promotes new meanings. DFA represents a session’s dialog asa “discourse network” made by the associations for temporal adjacency betweencontents; then it studies the network’s dynamic properties. DFA has been appliedto the textual corpus obtained from the verbatim transcript of a 15-session psy-chotherapy course. Findings are consistent with the hypotheses.

Introduction

Research on the psychotherapeutic process has increased greatlyover the last three decades. Several methods and procedures havebeen developed, differing in regard to focus of evaluation, unit ofanalysis, source of data, and other issues (Hill & Lambert, 2004).Above all, due to the difficulty of developing a shared and compre-hensive model of the psychotherapy process, almost every methodentails a peculiar way of looking at psychotherapy and at how itworks.

Received 12 July 2009; accepted 3 December 2009.Address correspondence to Sergio Salvatore, University of Salento, Department of

Educational, Psychological, and Teaching Sciences, Palazzo Parlangeli, Via Stampacchia47, 73100, Lecce, Italy. E-mail: [email protected]

195

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

196 S. Salvatore et al.

However, within these different approaches, one way of see-ing the psychotherapy process is to look at it as an intersubjectivedynamics of co-construction of meaning producing semiotic novelty(Salvatore, Tebaldi, & Potı, 2009). This dialogic and semioticapproach is widely shared within the clinical field, crossing overinto different theories of technique: psychodynamic (Gill, 1994;Salvatore & Venuleo, 2008), cognitive (Dimaggio & Semerari,2004), humanistic (Hermans & Hermans-Jansen, 1995), narrative(Angus & McLeod, 2004; Santos et al., 2009; Spence, 1982), andcouples therapy (McNamee & Gergen, 1992). According to thisperspective, clinical exchange is a co-construction of meanings(i.e., intersubjective meaning-making) aimed at changing thepatient’s affective and cognitive modality of interpreting his orher experience (Gennaro et al., in press; Neimeyer & Mahoney,1995; Rosen & Kuehlwein, 1996). Psychotherapy can be thereforeseen as a “transformative dialog” (Gergen, 1994, p. 250), whereinnew meanings are elaborated, new categories are developed,and one’s presuppositions (Chambers & Bickhard, 2007) aretransformed within an intersubjective context.

However, researchers sharing these assumptions have not yetelaborated methods dealing with the co-construction of meaningas a process that needs to be mapped as a whole; rather, theyhave focused on specific aspects of it (e.g., illocutionary strategiesstudied with the Verbal Response Mode [Stiles, 1986]) and its ef-fects at the level of individual variables (e.g., patient’s narratives[Handtke & Angus, 2004] or patient’s meta-cognitive function-ing [Semerari, Carcione, Dimaggio, Falcone, Nicolo, Procacci, &Alleva, 2003; Semerari, Carcione, Dimaggio, Falcone, Nicolo, Pro-cacci, Alleva, & Mergenthaler, 2003; Semerari, Dimaggio, Nicolo,Procacci, & Carcione, 2007]).

This gap between theory and methodology has preventedthe intersubjective dynamics of meaning co-construction from be-ing considered a general dimension, underlying a comprehensivemodel of psychotherapeutic change. On the other hand, this gapcan be easily understood: depicting the clinical exchange as a co-construction of meaning requires models and methods of analysiscapable of actually taking the dynamic and systemic nature of thepsychotherapy process into account (Greenberg, 1994). And weknow that even if some pioneering attempts have been made inthis direction (Kowalik et al., 1997; Schiepek et al., 1997; Stiles,

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

Psychotherapy as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making 197

2006; Tschacher, Schiepek, & Brunner, 1992; Tschacher, Baur, &Grawe, 2000), current methods—based on the idea of recompos-ing the process in terms of the linear addition of single time-discrete events—are not satisfactory (Elliott & Anderson, 1994;Stiles, 2006). Moreover, analyzing meaning entails reference tothe hermeneutic relationship between text and its context (Den-zin & Lincoln, 1994; Gadamer 1960), which makes it hard to de-fine low-inferential, replicable interpretative procedures that candepict the meaning-making that unfolds within the clinical ex-change.

This article presents the application of discourse flow anal-ysis (DFA; Gennaro et al., in press) to a case of psychotherapy.DFA is a method of textual analysis of the psychotherapy process,aimed at mapping psychotherapy as an intersubjective dynamicof co-construction of meaning. In accordance with this aim, DFAanalyzes patient–therapist dialog in formal terms (i.e., by depict-ing the structural global qualities of their communicational ex-change) rather than merely in terms of the semantic contents ex-changed within their dialog. In so doing, DFA enables the twomethodological issues recalled above to be overcome: (1) It al-lows a dynamic analysis of meaning-making, focusing on temporalpatterns of meanings, rather than on the survey of discrete con-tents; and (2) it adopts an automated low-inferential procedureof content analysis, yet at the same time is capable of taking thecontextuality of meaning into account to some extent.

In this study we focus on DFA’s construct validity, by testing itscapability of mapping patient–therapist talk in terms of structuralglobal qualities, consistent with the model of meaning-makingtaken as its theoretical basis.

The Dynamic and Systemic Nature of Meaning-Making

Most methods developed to analyze the psychotherapeutic pro-cess at a verbal level focus on the semantic content of the clini-cal exchange (i.e., Benjamin & Grawe-Gerber, 1989; Luborsky &Crits-Cristoph, 1990; Semerari et al., 2007), according to a moregeneral methodological point of view widely shared in psycholog-ical science (Greenberg, 1991, 1994; Salvatore & Pagano, 2005).Analyzing semantic content is important but not sufficient in or-der to understand the clinical exchange. There are three main

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

198 S. Salvatore et al.

reasons for this. First, a methodological limitation must be takeninto account: because of the indexicality of linguistic signs (i.e.,the fact that the semantic content of a sign needs the context tobe understood; see Nightingale & Cromby, 1999), analysis of se-mantic content requires a high level of inference. We do not havean automatic procedure for doing this, and we need intensive la-bor operations, having to cope with major problems of reliability.To avoid this methodological limitation, several methods have fo-cused on the lexical dimension of the language; that is, on somequalities of words other than the content. For example, Bucci andFreedman (1981) focused on the use of the first person singu-lar as a marker of psychological distress; Holzer and colleagues(1996) noted that the amount of shared vocabulary between ther-apist and patient, being a reflection of the therapist’s ability tobe accommodating, is related to the efficacy of psychotherapy;and Reyes and colleagues (2008) directed their attention to thecombination between the first person and the present tense, as amarker of psychological change.

Second, semantic content is contingent to the social context.Producing a sign is not a mere linguistic operation, but a speechact (Austin, 1962), a communicative act that is an integral partof and is carried out by an intersubjective system of activity. Con-sequently, the sign’s psychological meaning is not given by its se-mantic content; rather, it is given by the communicative function itperforms in the discursive activity. And it is evident that this com-municative function is not immanent to the sign, but depends onthe way it is used in relation to the other signs within the inter-subjective circumstances of the discourse (Harre & Gillett, 1994;Wittgenstein, 1953; as far as psychotherapy research is concerned,see Greenberg & Pinsof, 1986). This means that meaning-makinggoes beyond content, being dependent on the way contents arerelated to each other.

Third, from the previous considerations one must concludethat the relations between contents basically arise from—or at anyrate, entail—associations for temporal adjacency. That is, meaning-making strongly—even if obviously not exclusively—depends onthe way contents are combined throughout the flow of thediscourse, one after the other. One can imagine other kinds ofrelations between contents, apart from adjacency. For example,metaphor is a form of meaning-making based on similarity (Gelo,

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

Psychotherapy as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making 199

2008; Gentner et al., 2001). Nevertheless, contiguity is the basicway of carrying out meaning-making, especially the affectiveand daily dimension of meaning-making: in spoken dialog,metaphoric meaning-making generally entails a relation ofcontiguity between the parts of the rhetorical figure, too. The psy-choanalytic principle of free association—as well as the rhetoricalfigure of metonymy—is based on the criterion of contiguity.

In sum, it is possible to see meaning-making as a dynamic pro-cess, that is, a phenomenon that unfolds over time. What is rele-vant is not content per se, but the sequential combinations overtime. To exemplify this statement, let us consider the followingsequences of thematic contents as characterizing the talk of twopatients:

• Patient 1’s sequence: experience of frustration → anger → pain→ desire to be helped by therapist.

• Patient 2’s sequence: pain → desire to be helped by therapist→ experience of frustration → anger.

As one can see, the thematic contents are the same in the twoflows; what changes is the sequence, and with the sequence theglobal meaning generated by the sequences. The first sequenceexpresses the patient’s demand to be supported by the therapist incoping with the emotive reaction to a negated desire. The seconddepicts a patient with negative feelings associated with his or herdesire to be helped by the therapist.

Moreover, the statements suggest that we should lookat meaning-making from a systemic standpoint. Highlight-ing the sequential structure of meaning-making means thatmeaning-making mainly depends on global—and thereforesystemic—modifications of the structure of relations between con-tents. In other words, meaning-making is a matter of change in therelations between contents (pattern modification), rather than ofcumulative changes of single independent contents.

In sum, two claims concerning meaning-making within the(therapeutic) verbal exchange can be made. First, meaning-making is a phenomenon that unfolds over time with a specifictime-dependent structure. Second, the unfolding over time of themeaning-making process must be traced/considered in terms ofpattern modification, that is, in terms of change in the relationsbetween different contents. This conceptualization is coherent

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

200 S. Salvatore et al.

with modern dynamic systems approaches to language and verbalcommunication both in general (Elman, 1995; Fagen & Colombo,1990) and in psychotherapeutic (Goolishian & Anderson, 1987;Perna, 1997) contexts.

The Two-Stage Semiotic Model of Psychotherapy Process

Considering the conceptual issues described above, we havedefined the Two-Stage Semiotic Model (TSSM; Nitti et al., inpress; Gennaro et al., in press): a model of a clinically effica-cious psychotherapeutic process, upon which DFA is based. Ac-cording to TSSM, the psychotherapy process can be depictedthrough the formal analysis of the structural global qualities ofthe patient–therapist’s verbal exchange. TSSM is based on the fol-lowing two assumptions.

Assumption 1: Two-Stage Articulation

Human beings are meaning-generating systems. Psychotherapycan thus be considered as an emerging context that promotes thecontinuous revision and elaboration of new meanings (meaning-making) over time. The psychotherapeutic process is seen asthe “development of co-evolving languages of coordinated ex-changes” between patient and therapist (Goolishian & Anderson,1987, p. 533; see also Gelo et al., 2008).

The motivation leading a patient to seek therapy and theclinical goal of such human activity make the clinical exchangea peculiar form of intersubjective meaning-making. Clinical ex-change is not only a co-construction of meaning, like every otherform of intersubjective meaning-making. Rather, it represents adialogical dynamic aimed at changing the patient’s affective andcognitive modality of interpreting his or her experience. In otherwords, the clinical exchange is not only a negotiation between thepatient’s and the therapist’s systems of interpreting the world, buta negotiation by means of which the patient’s system is expectedto change.

From both a constructivist (Mahoney, 1991; Rosen &Kuehlwein, 1996) and a dynamic systems perspective (see Haken,1992, 2006), psychotherapeutic change can be seen as a dialogicalprocess involving the deconstruction of old meanings and the

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

Psychotherapy as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making 201

creation of new ones (Hayes & Strauss, 1998; Mahoney & Marquis,2002; Mahoney & Moes, 1997; Tschacher et al., 1992) The patientarrives at psychotherapy with a predefined, more or less rigid sys-tem of declarative and procedural assumptions (e.g., concepts ofself and others, affective schemata, meta-cognitive modalities, re-lational and attachment strategies, and unconscious plans) whichare taken for granted and work as super-ordered meanings regu-lating the interpretation of experience (see Teasdale & Barnard,1993).This system of assumptions is therefore the source of thepatient’s psychological problems: symptoms, at the intrapsychicas well as at the relational level, can be understood as sustainedby or the consequence of such super-ordered meanings. One ofthe main therapeutic activities, therefore, consists of triggeringthe reorganization of the patient’s super-ordered meanings.

It is thus possible to claim that the change process in thecommunicational system made up of the patient–therapist in-teraction has two stages. In the first stage the patient–therapistexchange works fundamentally as an external source of limitationon the patient’s system of assumptions. The first stage is thereforefundamentally a deconstructive process (Hayes & Strauss, 1998;Kossmann & Bullrich, 1997; Mahoney & Marquis, 2002), withtherapeutic dialog aimed at placing constraints on the regulativeactivity of the patient’s problematic super-ordered meanings(Salvatore & Valsiner, 2006). The weakening of the patient’scritical super-ordered meaning (Samoilov & Goldfried, 2000)opens the way for the emergence of new super-ordered ones.

This is what happens in the second, constructive stage,when the patient–therapist dialog implements new super-orderedmeanings, replacing the previous ones in regulating the meaning-making experience. In sum, in the second stage, patient–therapistdialog works in support of the patient’s activity so that new as-sumptions can emerge. Obviously, the two stages are not totallydistinct and mutually exclusive. Both are present throughout psy-chotherapy, within every session, although to different extents.However, the two-stage assumption asserts that, at the macro-analytical level, it is possible to discriminate, in a clinically ef-ficacious psychotherapy process, between a first stage (whereindeconstructive meaning-making is dominant) and a second one(wherein the dynamics of meaning-making acquires a construc-tive function).

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

202 S. Salvatore et al.

Following this postulate, we expect that the incidence of theregulative assumptions around which the therapeutic dialog is or-ganized (i.e., super-ordered nodes; see “Methods”) in the pro-cess of meaning-making will decrease in the first (deconstructive)stage and then increase in the second (constructive) stage.

Assumption 2: Nonlinearity of the Psychotherapy Process

Assumption 1 suggests that the clinical exchange performs dif-ferent functions in the two stages—respectively, a deconstructiveand a constructive one. If this assumption is true, it follows thatthe system comprised by the patient–therapist verbal exchangemust present a peculiar and different functional organization ormode of working in each stage. Consequently, meaning-makingdoes not follow a linear way of functioning over the course of thepsychotherapy; instead, at a certain point, it has to deal with a re-organization of its activity.

Following this assumption, we expect that the deconstructiveand constructive stages will be characterized by different patternsof relationships among those features of the therapeutic dialogthat contribute to meaning-making (i.e., the DFA indexes; see“Methods”).

Methods

Data

The study is applied to the whole textual corpus obtained fromthe verbatim transcript (both therapist and patient talk) of a15-session, good outcome course of psychotherapy from theYork Psychotherapy Depression Project. The patient (pseudonymLisa) was a young, married woman in her late 20s who receivedan emotion-focused therapy for depression (see Greenberg &Watson, 1998; Goldman, Greenberg, & Angus, 2006). The YorkPsychotherapy Depression Project envisaged the recruitment ofparticipants by advertisement, an initial session of assessmentbased on the use of the full multiaxial version of the SCID III-R,and a set of outcome measures applied before treatment, at mid-treatment (Session 8), at posttreatment, and at 6- and 18-monthfollow-ups: the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., 1961),

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

Psychotherapy as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making 203

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965), Inventory forInterpersonal Problems (Horowitz et al., 1988), and SymptomChecklist-90-Revised (Derogatis, Rickels, & Roch, 1976). Lisamade significant gains on all measures, maintaining and evenimproving, particularly in terms of self-esteem at the follow-upassessments (for details, see Angus, Goldman, & Mergenthaler,2008). Lisa also completed a process measure, the WorkingAlliance Inventory, Short Form (Horvath & Greenberg, 1989),after Sessions 4, 7, and 15. The case has been analyzed accordingto different theories and methodologies (see Angus et al., 2008).

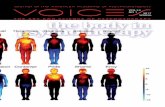

Measures and Procedures

The transcript was analyzed by means of DFA. DFA maps theverbatim transcript of psychotherapy dialog in terms of theassociations for adjacency between semantic contents occurringwithin the clinical exchange. Therefore, DFA focuses on aspecific—not exhaustive1 but highly significant—dimension ofmeaning-making, namely, the one implemented by sequentialcombinations of meanings (i.e., associations for adjacency) overtime (Gennaro et al., 2009). In order to operate this way, DFArefers to the concept of “discourse network.” A discourse networkis made up of semantic nodes, each of which represents one ofthe units of semantic contents active in the communicationalexchange between patient and therapist. (The choice of notdistinguishing patient and therapist contents reflects the DFAdialogical model; DFA can, however, be applied to patient or totherapist contents, as well, in order to deepen the observationsrelating to each participant). The directional linkage betweentwo given semantic nodes shows the association for adjacencybetween the corresponding contents. Figure 1 shows a selectedpart of the discourse network extracted from Lisa’s first session.

DFA works in three steps (Gennaro et al., in press). In thefirst step, computer-assisted content analysis is carried out usingsoftware for textual analysis (T-LAB Version 5.3.02; Lancia, 2007;see Lancia, 2002), able to identify the semantic contents activein the text and to categorize it through them. This procedureis grounded in the assumption that the semantic content of atext can be depicted in terms of how the words tend to associatewith each other. According to this assumption, the meaning of a

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

204 S. Salvatore et al.

0.125

0.125

0.25

0.18

N1 N5

0.25

1.0

1.0

0.11

N3

N2

N6

N7

N4

0.25

FIGURE 1 A selected area of the discourse network of the Lisa psychotherapy’sfirst session. Note. Each node Ni represents a thematic content active in the dis-course network (N1: “feeling/expression of impotence”; N2: “feeling/fear ofbeing abandoned”; N3: “desire to indulge own selfishness”; N4: “temporal andspatial constraints”; N5: “autonomy-dependence”; N6: “self-appreciation”; N7:“schedules in life and in therapy”). The directional linkage between two givennodes shows the association for adjacency between the corresponding contents.The thickness of the line is proportional to the strength of the association (mea-sured in terms of probability, expressed by the coefficient close to each line).This discourse network indicates that the thematic content N1 (correspondingto Cluster 4 of the output) is followed by the thematic content N2 (Cluster 20)in the 11% (p = 0.11) of the cases. In turn, this last thematic content always (p =1.0) precedes N3 (Cluster 22). N4 (Cluster 23) is followed by N5 (Cluster 15) andN6 (Cluster 16) and itself in equal proportion (25% of cases) and by N7 (Cluster2) in 12.5% of cases, and so on. (Note that the probability of the connectionsoutgoing from the singular node does not get systematically get 1.00 because thefigure shows just a partial area of the discourse network. The whole discoursenetwork of the first session encompasses 19 nodes).

word consists of the associations it has with the other words inthe text. According to the same assumption, a semantic contentactive in the text corresponds to a pattern of co-occurrences ofwords (i.e., a set of words that tend to be present together acrossthe text). Various psychological and linguistic models (Andersen,

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

Psychotherapy as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making 205

2001; Carli & Paniccia, 2002; Landauer & Dumais, 1997; see alsoLancia, 2002) adopt a version of this assumption. As in the case ofDFA, these models inform computational procedures of textualanalysis that have proved to be capable of obtaining meaningfulsemantic representation of texts.2

The DFA procedure of content analysis is accomplished bytransforming the lexical corpus into a numeric matrix to be sub-jected to a multidimensional procedure of analysis. In order tocarry out this task, the following substeps are followed.

1. T-LAB segments the transcript into units of analysis called ele-mentary context units (ECU), each of them corresponding toone or more utterances of which the text is composed.

2. T-LAB singles out all the word forms present in the text and cat-egorizes them according to the lemma to which they belong. Alemma is the citation form (headword) used in a language dic-tionary to refer to a lexeme, that is, a set of word forms havingthe same meaning. For example, word forms like “go,” “goes,”“going,” and “went” have “go” as their lemma; “child” and “chil-dren” have “child” as their lemma. The output of this substepis the list of lemmas present in the transcript.

3. The results of Substeps 1 and 2 are summarized in a matrix,with the rows representing the ECU and the columns the lem-mas of the whole text. Each cell of the matrix can assume onemode of a binary code: 1 for presence, 0 for absence. Thus,the matrix represents the distribution of presence or absenceof the lemmas in the ECUs composing the text.

4. A cluster analysis is then applied to the matrix. The clusteranalysis groups the ECUs using the lemmas as criterion of sim-ilarity: The higher the number of lemmas shared by two ECUs,the higher the probability that these two ECUs are groupedin the same cluster. Therefore, each cluster obtained is a setof utterances (i.e., ECUs) that share many lemmas. Accord-ing to this criterion of similarity, the DFA considers a clusterthe marker of thematic content active in the text. Table 1 re-ports the three most representative ECUs grouped in Cluster1 (the cluster globally encompasses 94 ECUs, correspondingto 5.25% of the classified ECUs in the text; see Table 2) enu-cleated by the cluster analysis applied to Lisa’s case. As one

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

206 S. Salvatore et al.

TABLE 1 The Most Representative ECUs of Cluster 1, Produced by the ClusterAnalysis Applied to the Transcripts of Lisa’s Case

ECU 1 (Occurred in Session 9; Score: 185.32)T: how would you do that?L: uh just I either stay in the house or do house cleaning or whatever needs to

be done um.T: how would you do that right now if you were to just sort of like put her

aside, put her, what do you do, put her in a box almost?L: um.T: trap her. try to do that now, to trap her and put her awayL: okay, um, just, just stay home

ECU 2 (Occurred in Session 12; Score: 172.70)T: tell her she scares you and you feel small, tell her about what it like,

speak from it’s almost like saying ‘I’m small and I feel’ finish it off.L: I’m ah: I’m small and I feel ah, ah, just helpless um.T: mm-hm.L: just giving out myselfT: mm-hm, a little lost?L: yeah, I feel um lostT: tell her.L: insecure

ECU 3 (Occurred in Session 9; Score 160.59)T: so you you sort of keep her, shield her from the people from the world in

a sense.L: yeah.T: okay, be the shield, be shield and speak from that and tell her what you

feel.L: um, I don’t want you to desert me or just just stay with me and and we’ll

make it through together.T: mm-hm. tell her how you protect her.

Note. The score is a chi-square parameter depicting the association between the ECU(token) and the cluster (type). The higher the index the higher the representativeness ofthe ECU respect to the cluster. T = Therapist; L = Lisa. Underlined words are word formsbelonging to the characteristic lemmas of the identified cluster.

can see, the three ECUs share a common thematic area con-cerning the recognition of needs and desires in relations withothers.3

5. Finally, each ECU is indexed according to the cluster it be-longs to. Therefore, the output of DFA’s first step (Substeps1–4) is the transformation of the transcript into a sequence ofthematic contents. For example, the sequence characterizing

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

Psychotherapy as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making 207

TABLE 2 Elementary Context Unit (ECU) in Each Cluster

Cluster Number of ECUs % of classified ECUs

1 94 5.252 96 5.373 76 4.254 86 4.815 90 5.036 87 4.867 86 4.818 72 4.029 65 3.63

10 61 3.4111 64 3.5812 45 2.5213 42 2.3514 45 2.5215 98 5.4816 32 1.7917 106 5.9318 104 5.8119 99 5.5320 101 5.6521 90 5.0322 71 3.9723 79 4.42

Total 1789 100

the initial moments of Lisa’s first session is the following: “feel-ing/expression of impotence” (Cluster 4) → “feeling/fear ofbeing abandoned” (Cluster 20) → “desire to indulge own self-ishness” (Cluster 22) → “temporal and spatial constraints”(Cluster 23) → “temporal and spatial constraints” (Cluster23) → “autonomy-dependence” (Cluster 15) → “temporal andspatial constraints” (Cluster 23) → “temporal and spatial con-straints” (Cluster 23) → “self-appreciation” (Cluster 16) →“schedules in life and therapy” (Cluster 2).

The DFA’s second step uses the output of the previous step tomodel the clinical exchange in terms of discourse network —eachthematic content is considered to be a node of the discoursenetwork (henceforth: semantic node). To do this, a Markovian

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

208 S. Salvatore et al.

TABLE 3 DFA Descriptive and Interpretative Indexes

Label Definition

Descriptive Indexes

Connectivity The density of connections between the discoursenetwork’s semantic nodes

Heterogeneity The distribution of connections between thediscourse network’s semantic nodes

Generative Power Discourse network’s capability of increasing itsmeaning variability (i.e., the spectrum ofassociations for adjacency among the semanticnodes)

Absorbing Power Discourse network’s capability of decreasing itsmeaning variability (i.e., the spectrum ofassociations for adjacency among the semanticnodes)

Interpretative Indexes

Activity The global orientation of the discourse network’scapability of enlarging its meaning variability

Super-Order Nodes Incidence of semantic nodes carrying out afunction of super-ordered meaning regulatingthe meaning-making process

sequence analysis (Bakeman & Gottman, 1997) is applied tothe sequence of the previously identified semantic nodes (seeSubstep 5 of the first step) in order to calculate the probabilityassociated with the linkage for adjacency between each pair ofsemantic nodes. In other words, for each thematic content, DFAcalculates its probability of coming straight after every otherthematic content (see Figure 1 for an example of discoursenetwork extracted from the first session of Lisa’s case).

The third step is aimed at analyzing the structural and dy-namic characteristics of the discourse network, insofar as they areconsidered indicative of relevant aspects and qualities of themeaning-making process. It is carried out by means of descriptive(Connectivity, Heterogeneity, Generative, and Absorbing Power)and interpretative (Activity and Super-Ordered Nodes) indexes,also summarized in Table 3.

Connectivity: This measures the network’s density of associations,that is, the relative amount of connections among the semantic

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

Psychotherapy as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making 209

nodes. It is calculated as the ratio between the active connec-tions present in the network (as identified through the Marko-vian analysis) and the network’s maximum theoretical amountof possible connections. This maximum is n2, where n is thenumber of semantic nodes present in the discourse network.This is so because, theoretically, each node can be connectedwith every other node, including itself. Therefore, every nodecan theoretically have n connections. and the whole network n× n connections. For instance, the discourse network depictedin Figure 1 has a connectivity of 0.142 (number of connections:8; maximum theoretical amount of possible connections: 49 [asa result of the fact that there are seven semantic nodes]; Con-nectivity: 8/49). This figure can be interpreted as follows: thediscourse network of Figure 1 has 16.3% of the possible con-nections among its nodes active.

Heterogeneity: This index depicts how the connections are dis-tributed among the nodes. It is calculated as the standard devi-ation of the distribution of the amount of connections startingfrom and arriving at every semantic node. The higher the levelof this index, the higher the variability of the connection distri-bution among nodes (i.e., some nodes have many connectionsand others very few). With reference to Figure 1, the discoursenetwork depicted has a Heterogeneity of 1.069. This value rep-resents the standard deviation of the distribution of the num-ber of the ongoing (o) and incoming (i) connections of theseven nodes (N1: o = 1, i = 0; N2: o = 1, i = 1; N3: o = 1, i =1; N4: o = 4, i = 3; N5: o = 1, i = 1; N6: o = 1, i = 1; N7: o = 0,i = 2).

Activity: This is a global parameter depicting the network’s capa-bility of enlarging meaning variability (previously defined asthe spectrum of associations for adjacency among the seman-tic nodes) through time. Therefore, a high Activity level indi-cates that the discourse, as it evolves, progressively tends to in-crease the variability of the connection between meanings, thatis, the number of other nodes that adjacently follow each node.In metaphorical terms, a high Activity level depicts a discoursedynamics capable of enlarging the paths of meaning-making,by enriching the possibilities of combination among the mean-ings making up these paths. Activity is calculated as the ratiobetween the network’s Generative Power and Absorbing Power.

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

210 S. Salvatore et al.

These two parameters depict the capability of the discoursenetwork of respectively increasing and decreasing the mean-ing variability (i.e., the spectrum of associations for adjacencyamong the nodes) through time. The estimate of GenerativePower and Absorbing Power is based on the measure of eachsingle node’s contribution to the variability of discourse mean-ing (henceforth: Contribution). The Contribution of each sin-gle node is calculated as the product of the difference betweenthe amount of outgoing (o) and incoming (i) connections ofthe considered node, and the ratio of the frequency of con-nections (o + i) from/to that node to the number of its the-oretically possible connections (n, where n is the number ofsemantic nodes present in the discourse network). Calculatingit in this way allows the absolute difference between incomingand outgoing connections not only to be taken into accountbut also to be weighted according to the importance of thenode (i.e., the amount of linkages between the node consid-ered and the others). For instance, in the discourse networkdepicted in Figure 1, the contribution of N4 is 1.00 ([o = 4; i =3; n = 7; [4−3]∗[4 + 3]/7]) and of N7 −0.574 ([o = 0; i = 2;n = 7; [0−2]∗[0 + 2]/7]). According to such a parameter, anode can be classified as a “generative,” “relay,” or “absorbing”node. A node is generative when it has more outgoing thanincoming connections; relay when it has the same number ofincoming and outgoing connections; absorbing when the in-coming connections exceed the outgoing ones. Referring toFigure 1, we can see that node N4 is a generative one, becauseit has more outgoing (4) than incoming connections (3); N5 isa relay node, because it has the same number of connectionsboth entering and going out (1); and N7 is an absorbing node,because it has fewer outgoing (0) than incoming connections(2). According to this operational definition, a generative nodehelps to increase the meaning variability of the discourse, be-cause it activates more semantic nodes than it is activated by. Anabsorbing node reduces the discourse meaning variability, be-cause the outgoing spectrum of thematic contents is narrowerthan the incoming one. A relay knot reproduces the variabil-ity. The network’s Generative Power and Absorbing Power arefinally calculated as the average contribution of the generativenodes and of the absorbing nodes, respectively.

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

Psychotherapy as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making 211

Super-Ordered Nodes: A Super-Ordered Node is a node carrying outa function of super-ordered meaning regulating the meaning-making process. In other words, a Super-Ordered Node repre-sents thematic content activating further meanings, accordingto the terminology used by Valsiner (2006), a promoting sign.DFA assumes the high frequency of occurrence (i.e., the tokensize) of a node and its strong associability with the other nodesas the markers of this super-ordered regulative function. Ac-cordingly, the index is calculated as the percentage of nodesof the network having both high frequency and high associa-bility. DFA defines a highly frequent node as one having a fre-quency higher than a 1.5 ratio between token (occurrences of agiven thematic content) and type (kinds of thematic content).A node is moreover defined as having high associability if it hasoutgoing and/or incoming connections with more than 33% ofthe nodes in the network. For instance, consider the discoursenetwork depicted in Figure 1. It was obtained from a text withthe following occurrences (token) for each kind of thematiccontent (type): N1 = 10 (that is, the thematic content N1 oc-curs 10 times in the text), N2: 28, N3: 20, N4: 50, N5: 43, N6: 44,and N7: 5. This means it is a text with 200 tokens correspond-ing to seven types, therefore, 28.57 as token/type ratio. Conse-quently, the threshold for defining a node as highly frequent inthis discourse network is 42.85 (i.e., 1.5 ∗ 28.57). Regarding as-sociability, node N4 is the one with associability higher than thethreshold (i.e., linkage with more than 33% of the nodes of thenetwork, as there are seven nodes and the threshold is 2.31).Therefore, N4 is the only node that has both high frequencyand high associability, thus fulfilling the criteria for being de-fined a Super-Ordered Node.

It is worth noting that DFA also provides a qualitative levelof analysis of the discourse network, grounded in the clinical in-terpretation of the meaning of the nodes. To this end, a groupof trained judges analyzes the output of T-LAB cluster analysis inorder to interpret the semantic nodes. We have some evidenceof good interrater reliability associated with this task (Salvatore,Gennaro et al., 2009). However, this level of analysis is not carriedout in this study, which is only focused on the formal, quantitativelevel of analysis.

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

212 S. Salvatore et al.

Meaning of the Indexes

In considering DFA indexes, a distinction must be made betweendescriptive and interpretative ones (see Table 3). Descriptive in-dexes (Connectivity, Heterogeneity, Generative, and AbsorbingPower) do not have a univocal relation with given major character-istics of the psychotherapy meaning-making process. This meansthat taken singly, the evolution of each of these indexes does notgive information on the psychotherapy process. Therefore, theseindexes must be taken into account together, in their interplay,having the function of describing the internal dynamics of thediscourse network, without any specific reference to the clinicalsignificance of these dynamics.

In contrast, DFA interpretative indexes (Activity and Super-Ordered Nodes) depict important clinical features of the thera-peutic process under analysis. Yet, DFA hypothesizes a nonlinearrelationship between each of these indexes and between themand the clinical quality of the process. Therefore, we do not ex-pect that, for example, an increase in Super-Ordered Nodes willalways bring an improvement in the clinical quality of the psy-chotherapy process. This tenet is a consequence of the systemicstandpoint from which DFA was developed. From this standpoint,also in the case of the interpretative indexes, what is relevant is notso much the trend of the indexes taken singly but the synchronicand diachronic patterns of their combination, characterizing theorganization of the discourse network as a whole.

Unit of Analysis

DFA was applied to the single session as the unit of analysis (i.e.,using the session as a window). In order to accomplish this task,first a computer-assisted content analysis (Step 1) was carried outon the textual corpus as a whole (see Tables 2 and 4 for descrip-tive statistics of the textual corpus under analysis of the outputof the cluster analysis; Point 4, Step 1 of the procedure); then theMarkovian sequence analysis (Step 2) and the analysis of the struc-tural and dynamic characteristics (Step 3) of the discourse wereconducted for each session. In this way, we obtained 15 discoursenetworks depicted by means of the DFA indexes.

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

Psychotherapy as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making 213

TABLE 4 Descriptive Statistics of the Textual Corpus Under Analysis

Descriptive Parameters Amount

Sessions 15Number of Elementary Context Units (ECU) 1790Average number of Elementary Context Units

(ECU) per session119.33

Number of occurrences in the text (Token) 113488Number of lemmas in the text (Type) 2541Token/Type ratio 44.66Number of lemmas in analysis 494Frequency threshold for selecting the lemma for

analysis8

Number of lemmas over the threshold butomitted because lacking semantic value

36

Number of clusters produced by cluster analysis(Substep 1.3)

23

Number of ECUs classified by the cluster analysis 1789Between cluster variance/total variance 0.361

Data Analysis

With the aim of describing patient–therapist meaning-makingand testing DFA construct validity, we carried out the followingprocedures of data analysis.

1. In order to deal with TSSM Assumption 1 (two-stage artic-ulation), we analyzed the relative frequency trend of Super-Ordered Nodes, testing the probability that the observedtrend fits a quadratic curve over the sessions (chi-squaredtest). To this end, we calculated the proportion of sessionsconsistent with a quadratic curve (U-slope) by using least-squared methodology in order to estimate the parameters ofthe quadratic curve (see Figure 2 for the model obtained).We also calculated the fitted curve’s confidence interval (90%,95%, and 99%), in order to see if the average absolute value ofthe residuals lies within it (Graybill & Iyer, 1994; see Appendixfor summary details concerning the Super-Ordered Nodevalues).

2. In order to deal with TSSM Assumption 2 (nonlinearity of thepsychotherapy process), we split the psychotherapy by using

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

214 S. Salvatore et al.

FIGURE 2 Fitted quadratic curve (FIT) of Super-Ordered Nodes (SON) overthe sessions with correspondent Confidence Intervals (CI).

the session presenting the lowest percentage of Super-OrderedNodes and still fitting the U-slope as cut-off point. In doing so,we identify Session 10 as the cut-off point. For each of the twoblocks of sessions thus created, we calculated the correlationbetween the DFA indexes Connectivity, Heterogeneity, Activity,and Super-Ordered Nodes as a way of mapping the patternsshaping the discourse network. Given the low number of cases,we used the Spearman rho test; for the same reason, we alsotook high coefficients (r >.700) of Stage 2 into account, evenif they were not statistically significant.

Hypotheses

A specific hypothesis was made for each procedure of data analysisdescribed above, in order to verify the TSSM of psychotherapyprocess through the DFA of psychotherapy sessions.

Hypothesis 1 (concerning point a of data analysis): Super-OrderedNodes will present a U-trend. More specifically, we expect to

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

Psychotherapy as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making 215

find that a statistically significant proportion of sessions fit aquadratic curve. Moreover, we expect to find that the averageabsolute value of the residuals lies within the fitted curve’s con-fidence interval. This trend would allow us to observe a de-constructive (descending trend) and a constructive (ascendingtrend) stage of intersubjective meaning-making throughout thetherapeutic process, in accordance with TSSM Assumption 1.

Hypothesis 2 (concerning point b of data analysis): In accordancewith the Super-Ordered Nodes’ two-stage articulation, the cor-relations among DFA indexes will present different values inthe first (deconstructive) and second (constructive) stages. Thiswould allow us to speak of the two stages of psychotherapy ascharacterized by different patterns of functioning of meaning-making, in accordance with TSSM Assumption 2.

Results

Super-Ordered Node Trend (Hypothesis 1)

The Super-Ordered Node trend presents a course significantlyclose to a U-shape (see Figure 2), with 11 out 15 sessions (Sessions1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 14, and 15) having a position consistentwith a U-trend (chi-square highly significant: p > 0.01). Sessions3, 10, and 14 are the minimal peaks, and Sessions 1, 12, and 15 themaximum peaks. This observation is confirmed by the analysis ofthe confidence interval limit. The mean of the absolute residualvalue is 0.036, and the confidence interval length is 0.026, 0.032,and 0.044 for significant level α = 10%, α = 5%, and α = 1%,respectively. Therefore, the Super-Ordered Node values present acourse significantly close to a U-shape at a significance level be-tween α = 5% and α = 1%.

Correlation Among DFA Indexes in the Two Stages (Hypothesis 2)

In order to more exactly split Lisa’s psychotherapy into the twoassumed stages, we first identified the minimal peak of the Super-Ordered Node trend. The percentage of Super-Ordered Nodesis equally low in Sessions 3, 10, and 14; nevertheless, Session 10is the only one among the three to be consistent with the U-slope. Therefore, we chose the latter as the cut-off point to split

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

216 S. Salvatore et al.

the 15-session psychotherapy course into two stages. Followingthese results, the deconstructive stage goes from Sessions 1 to 10,and the constructive stage from Sessions 11 to 15. Table 5 showsthe correlation coefficients (Spearman’s rho) among the DFA in-dexes (Activity, Connectivity, Heterogeneity, and Super-OrderedNodes), calculated for each of the two stages (Sessions 1–10 vs.Sessions 11–15). One can observe that three out of six correla-tions change between the two stages. Passing from the first to thesecond stage, the correlation between Super-Ordered Nodes andActivity decreases substantially (first stage: r = .638; second stage:r = .400), whereas the correlations between Super-OrderedNodes and Heterogeneity (first stage: r = .423; second stage:r = .800) as well as between Heterogeneity and Connectivity(first stage: r = .268; second stage: r = 1.000) become consid-erably higher. The correlation between Connectivity and Second-Ordered Nodes is the only one that is significant or at least highin both the stages (respectively r = .707 and r = .800).

Discussion

The results seem consistent with the hypotheses and thereforewith TSSM.

Super-Ordered Node Trend (Hypothesis 1)

First, we found that the trend of Super-Ordered Nodes fundamen-tally fits a U-shape, as we hypothesized in accordance with TSSMAssumption 1 (two-stage articulation). The proportion of sessionsfitting the quadratic curve described by the super-ordered nodesis significantly different by chance; moreover, the observed trendis consistent with the quadratic fitted curve, within a confidenceinterval between 95% and 99%.

On the basis of these results, one can describe thepatient–therapist verbal exchange as divided into two stages—afirst (deconstructive) stage, wherein the Super-Ordered Nodes de-crease (Sessions 1–10), and a second (constructive) one, whereinthey increase (Sessions 11–15). These results suggest that the sys-tem of assumptions (operationally marked by the Super-OrderedNodes) regulating the therapeutic dialog enters first a “destabi-lization” process, where the existing assumptions are weakened

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

TA

BL

E5

Cor

rela

tions

(Spe

arm

an’s

rho)

Bet

wee

nD

FAIn

dexe

sin

the

Firs

tand

Seco

ndSt

ages

ofL

isa’

sPsy

chot

hera

py

Stag

e1

(Ses

sion

s1–1

0)St

age

2(S

essi

on11

–15)

Con

nect

ivity

Het

erog

enei

tySu

per-O

rder

edN

odes

Con

nect

ivity

Het

erog

enei

tySu

per-O

rder

edN

odes

Act

ivity

.439

.176

.638

∗−

.100

−0.

100

.400

Con

nect

ivity

—.2

68.7

07∗∗

—1.

000∗∗

.800

◦

Het

erog

enet

y—

—.4

23—

—.8

00◦

Not

e.∗ C

orre

latio

nis

sign

ifica

ntat

the

0.05

leve

l(tw

o-ta

iled)

.∗∗ C

orre

latio

nis

sign

ifica

ntat

the

0.01

leve

l(tw

o-ta

iled)

.◦N

onsi

gnifi

cant

corr

elat

ion

how

ever

high

erth

an.7

00.

217

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

218 S. Salvatore et al.

(Sessions 1–10). This may be seen as creating the conditions fortriggering a change process, which leads to—and at the same timeis composed of—the emergence of new assumptions (Sessions11–15).

In sum, according to our interpretation, the therapeuticdialog between Lisa and her therapist worked as a source ofconstraint on Lisa’s clinically problematic system of assumptions(operationally marked by the Super-Ordered Nodes). The reduc-tion of the incidence of Lisa’s assumptions in the deconstructivestage (Sessions 1–10) may have created the emotional andcognitive room for a subsequent elaboration of new meanings. Asa consequence, in the constructive stage that followed (Sessions11–15), therapist–patient meaning-making has become a processcapable of producing new regulative meanings whose develop-ment is associated with the psychotherapy’s positive outcome.4

This interpretation is consistent with a dynamic systemsapproach to the psychotherapeutic process (Goolishian &Anderson, 1987; Mahoney & Marquis, 2002; Mahoney & Moes,1997; Perna, 1997; Ramseyer & Tschacher, 2008; Reynolds et al.,1996; Tschacher et al., 1992; see also Gelo et al., 2008, concerningthe same case).

Moreover, our interpretation is consistent with the results oftwo other empirical studies that recently investigated the samecase reported here (Lisa) using different methods. Nicolo andcolleagues (2008) investigated the change over the course of treat-ment in Lisa’s states of mind (i.e., discreet, recognizable, and gen-erally recurring mental patterns organizing life themes, emotions,and somatic states characterizing patients’ subjective experience[Horowitz, 1987]). They observed significant changes in the statesof mind of the patient in correspondence to Sessions 9–12. Dur-ing these sessions, “Lisa’s subjective experience becomes richer,and a wider variety of constructs can be seen than at the begin-ning of her treatment” (Nicolo et al., 2008, p. 654). Moreover,they observed a reduction in the intensity of Lisa’s negative con-structs, which is consistent with the positive outcome of her treat-ment. Carcione and colleagues (2008) investigated the course ofLisa’s metacognitive functioning (i.e., the ability to form cogni-tions about cognition and affects both in the self and in the otherperson to whom a subject relates) over the course of the ther-apy. They reported that, as expected, a widespread impairment

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

Psychotherapy as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making 219

of mastery skills (i.e., the ability to correctly define the terms ofone’s psychological problems and adopt an active problem-solvingattitude) compared to self-reflection (i.e., the ability to identifyone’s own mental states) and understanding of others’ mind (i.e.,the ability to form and articulate representations of others andwhat they feel and think). Interestingly, Carcione and colleagues(2008) observed that from Session 10 (the cut-off session identi-fied by our analysis) onward, mastery failures decrease, and theydisappear at the end of the therapy.

Correlation Among DFA Indexes (Hypothesis 2)

The comparison of the correlations among the DFA indexes be-tween the two stages does not lead us to invalidate Hypothesis2, drawn from TSSM Assumption 2 (nonlinearity). It was actuallypossible to identify a shift from the deconstructive stage (Sessions1–10) to the constructive one (Sessions 11–15) in the relation-ships between the variables we used to depict the verbal exchangethrough DFA. The fact that the two sets of correlations among theDFA indexes show differences that reach 50% (three out of sixcases) allows us to conclude that a major change in the dynamicsunderlying the therapeutic discourse (as depicted through DFA)occurs from the first to the second stage.

These results are consistent with the view that psychotherapyhas to be conceived in terms of interacting patterns of reciprocalmodifications, rather than as an additive and cumulative collec-tion of independent single effects (Grawe, 1992). According tothis view, change in psychotherapy is a matter of pattern modifi-cation (Greenberg, 1991; Shoham-Salomon, 1990), which is hardto grasp in terms of modification of isolated variables.

Considering the two sets of correlations enables us to makesome statements about the interpretation of the change under-gone by the discourse dynamics. For this purpose, we focus on thefinding concerning the two significant correlations involving Het-erogeneity that occur only in the second block (Heterogeneity,Connectivity and Heterogeneity, Super-Ordered Nodes). Thesetwo second block-specific correlations highlight a change in themodality of functioning of the discourse network. In the firststage, the change in the overall connection density of the network(Connectivity) is distributed throughout the nodes—regardless

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

220 S. Salvatore et al.

of whether they are super-ordered or not—as shown by thefact that neither Connectivity nor Super-Ordered Nodes are cor-related with the variability of the distribution of connectionsper node (that is, the Heterogeneity). In contrast, in the sec-ond stage the change in connection density concerns only somemeanings—mainly the regulating ones—as shown by the fact thatboth Connectivity and Super-Ordered Nodes are associated withthe variability of the distribution of connections per node.5

In sum, taking this data as a whole, and together with theother data previously discussed, we see two different ways in whichthe Lisa–therapist discourse functions, each of them characteriz-ing one stage of the psychotherapy. In the first stage, the discoursedynamics works in terms of a decrease in the incidence of thesuper-ordered regulative meanings, which runs alongside a broadreduction of the connections among all the network’s meanings.In other words, in the first stage the constraints on regulativemeaning are the result of a more global tendency of meaning-making between Lisa and her therapist to place constraints on allthe connections active in the discourse exchange. In contrast, inthe second stage the increase in super-ordered regulative mean-ings seems to depend on the creation of connections concerningmore specifically the regulative meaning itself. It could be saidthat, whereas the first, deconstructive stage works, from a linguis-tic perspective, in a generalized way over the whole spectrum of as-sociations of the entire discursive exchange, the constructive stageoperates in a specialized way, focusing on the regulative meanings.

Conclusion

We have reported the results of a single case application of anew method of psychotherapy process analysis—DFA—which isgrounded in a semiotic and dialogical model of the psychother-apy process: TSSM. By following it, the psychotherapeutic processcan be depicted through the analysis of patient–therapist verbalinteraction in terms of a process of intersubjective coconstructionof meaning (i.e., meaning-making).

The map of Lisa’s psychotherapy provided by DFA provesconsistent with the operative hypothesis drawn from the twoTSSM assumptions (the two-stage articulation and the non-linearity of the psychotherapy process). Needless to say, this

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

Psychotherapy as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making 221

evidence is heartening but, obviously, neither exhaustive nordefinitive.

First, we have carried out only a formal and quantitativeanalysis of the case, leaving aside all reference to the qualita-tive/clinical content of the psychotherapeutic dialog. Thus, noinformation has been provided concerning what Lisa and hertherapist talk about, or concerning the therapist’s strategies. Therelative frequency of the Super-Ordered Nodes concerns theregulative function of the basic assumptions active in the ther-apeutic discourse (namely, their incidence in the therapeuticmeaning-making process), but it does not give information onthe quality of the content of these meanings. For this reason,we can only suppose that the increase of Super-Ordered Nodesoccurring in the second, constructive stage of Lisa’s psychother-apy reflects the creation of different, new, and possibly clinicallyrelevant meanings. Nevertheless, it seems that this supposition isjustified by the change we observed in the patterns of correlationsbetween the first and the second stages of the treatment, whichis coherent with the idea that the regulative meanings in thesecond stage played a different role in the discourse dynamics ofthe treatment analyzed.

We recognize that this compositional choice makes our anal-ysis quite abstract and remote from clinical experience. Never-theless, we believe that going beyond reference to clinical con-tent is one of the ways for developing psychotherapy processresearch. DFA tries to pursue this aim by enlarging the focuson the formal and structural aspects of discourse. With refer-ence to Goncalves, Korman, and Angus (2000), it could be saidthat our approach focuses on something that is similar to nar-rative structure (i.e., the level of coherence and connectednessbetween different elements in a narrative) and in part to nar-rative process (i.e., the way the quality, variety, and complexityof the stylistic production of narrative reveals the subject’s de-gree of openness to experience) as compared to narrative con-tent (i.e., the diversity and multiplicity of contents expressed bynarratives).

Obviously, this does not mean refraining from referring toclinical data; we are aware that a formal/structural analysis ofthe psychotherapy process is not sufficient. Yet, in our opinion, astructural and formal map of the psychotherapy process, even if

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

222 S. Salvatore et al.

it is not exhaustive, can in itself provide informative and mean-ingful results, without the need to anchor them to phenomeniccontents. Various previous studies have investigated the thera-peutic process following this line of thought. From a linguisticperspective, for example, Mergenthaler (1996) analyzed thepatterns of the therapeutic dyad’s emotional–cognitive regulationwith reference to the relative frequency of language that isrespectively emotional and abstract. Following a similar formallinguistic approach, Bucci (1997) investigated the therapeuticcourse of referential activity (i.e., the degree to which languagereflects connections to nonverbal, bodily, and emotional expe-rience) with reference to the degree of concreteness, specificity,clarity, and imagery shown by therapeutic discourse. From amore general perspective—which explicitly refers to a dynamicsystems approach—Schiepek and colleagues (Kowalik et al., 1997;Schiepek et al., 1997) observed the existence of deterministicchaos (Schuster, 1989) within sequences of therapist–clientinteractional plans. Tschacher and colleagues investigated thecourse of synchrony between patient’s and therapist’s respectivesubjective rating of the therapy sessions (Tschacher, Scheier, &Grawe, 1998), speech (Gelo et al., 2008), and nonverbal behavior(Ramseyer & Tschacher, 2008). In all of these cases, no qualitativeinformation at the content level was given, but the results helpedin building a formal model of the psychotherapeutic process thatcan help in describing how therapy works.

Another aspect to be considered regarding the fact that weanalyzed the meaning-making process within the whole therapeu-tic dialogue, without distinguishing between patient and therapistspeech: This choice was made in order to show that the meaning-making process is an emergent property of the verbal exchangebetween patient and therapist and that, in accordance withthis, it can be considered as an intersubjective co-constructionof meaning (for similar approaches that do not distinguishbetween patient and therapist contribution, see Gelo et al., 2008;Mergenthaler, 1996; Ramseyer & Tschacher, 2008; Tschacheret al., 1998). Further studies could be conducted analyzingpatient’s and therapist’s speech separately, in order to verify ifthe results we obtained in the present study hold also for thepatient—as we firmly expect.

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

Psychotherapy as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making 223

Our findings are not conclusive for another series of reasons.DFA convergent validity has to be analyzed by comparing it withother process analysis measures and models; we have already ob-tained promising results in this direction (Salvatore et al., 2007).Moreover, we have planned to systematically replicate our findingson further cases with a variety of types of psychotherapies—withdifferent kinds of technical orientations, settings, therapists, pa-tient diagnoses, progress, and outcomes—in order to test the cri-terion validity of DFA and to identify the aspects of intersubjectivemeaning-making that are a stable characteristic of the psychother-apy process with respect to the elements that reflect a clinicallyefficacious process, the elements associated with one or the othertype of psychotherapy, as well as the elements reflecting the con-tingent aspects of the case (for example, Lisa’s depressive symp-tomatology or the length of her treatment).

However, regardless of the specific contents of its results, thestudy reported here highlights two methodological issues. First,we need procedures of data analysis that enable us to deal withthe systemic and nonlinear behavior of the psychotherapy pro-cess, as clinical exchange needs to be described in terms of pat-terns of functioning rather than of linear trends of single param-eters concerning specific aspects occurring within the process. Inother words, we need to move from studying what happens in theprocess to studying the process itself. Second, we need solutionsenabling us to implement procedures of textual data analysis thatare automatic yet capable of not reducing the meaning to its se-mantic content, regardless of the hermeneutic context.

Notes

1. Needless to say, DFA cannot grasp the dynamics of meaning-making in itswholeness. Intersubjectivity is a hyperdimensional process sustained by infi-nite sources of elements. DFA is based on the analysis of verbatim transcript,and therefore does not consider other relevant types of signs (e.g., the par-alinguistic and extralinguistic signs, as well as the subjective feelings of the par-ticipants experienced through and in association with the communicationalexchange). On the other hand, no method claims to be exhaustive. Rather,every method focuses on a given dimension of the phenomenon assumed tobe relevant.

2. Concerning the validity of the DFA content analysis procedure, it has beenshown that the semantic representation produced by DFA is consistent

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

224 S. Salvatore et al.

with the qualitative analysis performed by judges (Salvatore et al., inpreparation).

3. A systematic interpretation of the clusters produced by the DFA content anal-ysis procedure would require a systematic analysis of the ECUs between andamong the clusters, a task that goes beyond the aim and possibilities of thisstudy (for more details, see Salvatore, Gennaro et al., 2009). We provide inTable 1 a limited selection of ECUs only as an illustration.

4. However, one comment needs to be added. The Super-Ordered Node indexconcerns the regulative function of the super-ordered meanings active in thediscourse, but it does not give information on the quality of the content ofthese meanings. For this reason, we can only suppose that the decrease and in-crease of Super-Ordered Nodes occurring respectively in the first and secondstages of Lisa’s psychotherapy reflect the deconstruction of clinically negativemeanings in the first stage and the creation of new, clinically positive mean-ings in the second one. Nevertheless, it seems this supposition is justified bythe good outcome of the case.

5. In the second stage the Connectivity–Heterogeneity correlation is statisticallysignificant; the Super-Ordered Nodes–Heterogeneity does not reach statisti-cal significance. Nevertheless it is high (.800).

References

Andersen, S. (2001). The emergence of meaning: Generating symbols from ran-dom sounds: A factor analytic model. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics, 8,101–136.

Angus, L. E., & McLeod, J. (Eds.). (2004). The handbook of narrative and psychother-apy: Practice, theory, and research. London: Sage.

Angus, L., Goldman, R., & Mergenthaler, E. (2008). Introduction. One case, mul-tiple measures: An intensive case-analytic approach to understanding clientchange processes in evidence-based, emotion-focused therapy of depression.Psychotherapy Research, 18, 629–633.

Austin, J. (1962). How to do things with words. Oxford, UK: Oxford UniversityPress.

Bakeman, R., & Gottman J. M. (1997). Observing interaction: An introduction tosequential analysis (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). Aninventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 561–571.

Benjamin, L. S., & Grawe-Gerber, M. (1989). Structural analysis of social behavior:Coding manual for psychotherapy research. Berne, Switzerland: Universitat BernFachbereich Psychologie.

Bucci, W. (1997). Psychoanalysis and cognitive science. New York: Guilford.Bucci, W., & Freedman, N. (1981). The language of depression. Bulletin of the

Menninger Clinic, 45, 334–358.Chambers, J., & Bickhard, M. (2007). Culture, self, and identity: Interactivist

contributions to a metatheory for cultural psychology. Culture & Psychology,13, 259–295.

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

Psychotherapy as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making 225

Carcione, A., Dimaggio, G., Fiore, D., Nicolo, G., Procacci, M., Semerari A., &Pedone, R. (2008). An intensive case analysis of client metacognition in agood-outcome psychotherapy: Lisa’s case. Psychotherapy Research, 18, 667–676.

Carli, R., & Paniccia, R. M. (2002). L’analisi emozionale del testo. Uno strumentopsicologico per leggere testi e discorsi [Emotional textual analysis. A psychological toolfor understanding texts and discourses]. Milano, Italy: Franco Angeli

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (1994). Handbook of qualitative research.Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Derogatis, L. R., Rickels, K., & Roch, A. F. (1976). The SCL-90 and the MMPI:A step in the validation of a new self-report scale. British Journal of Psychiatry,128, 280–289.

Dimaggio, G., & Semerari, A. (2004). Disorganized narratives: The psychologicalcondition and its treatment. In L. Angus & J. McLeod (Eds.), The handbook ofnarrative and psychotherapy: Practice, theory, and research (pp. 263–282). Thou-sand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Elliott, R., & Anderson, C. (1994). Simplicity and complexity in psychotherapyresearch. In R. L. Russell (Ed.), Reassessing psychotherapy research (pp. 65–113).New York: Guilford.

Elman, J. L. (1995) Language as a dynamical system. In T. Van Gelder & R. F. Port(Eds.), Mind as motion: Explorations in the dynamics of cognition. (pp. 195–225).Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Fagen, J. W., & Colombo, J. (1990). Individual differences in infancy: Reliability,stability, prediction. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Gadamer, H. G. (1960). Wahrheit und methode [Truth and method]. Tubingen, Ger-many: Morh.

Gelo, O. (2008). Metaphor and emotional-cognitive regulation in psychotherapy: A singlecase study. Ulm, Germany: Ulmer Textbank.

Gelo, O., Ramseyer, F., Mergenthaler, E., & Tschacher, T. (2008). Verbal coordi-nation between patient and therapist speech: Hints for psychotherapy processresearch. In Society for Psychotherapy Research (Eds.), Book of abstracts of the39th annual meeting (p. 90). Ulm, Germany: Ulmer Textbank.

Gennaro, A., Al-Radaideh, A., Gelo, O., Manzo, S., Auletta, A., Aloia, N., et al.(in press). The psychotherapy process as a meaning-making dynamics: Theo-retical framework and methodology of analysis. In S. Salvatore, J. Valsiner, &J. Clegg (Eds.), YIS: Yearbook of idiographic science 2009 (Vol. 2). Roma: Firera.

Gentner, D., Bowdle, B., Wolff, P., & Boronat, C. (2001). Metaphor is like anal-ogy. In D. Gentner, K. J. Holyoak, & B. N. Kokinov (Eds.), The analogical mind:Perspectives from cognitive science (pp. 199–253). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gergen, K. J. (1994). Realities and relationships. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univer-sity Press.

Gill, M. (1994). Psychoanalysis in transition. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.Grawe, K. (1992). Psychotherapieforschung zu Beginn der neunziger Jahre [Psy-

chotherapy research at the beginning of the 1990s]. Psychologische Rundschau,43, 132–162.

Graybill, F. A., & Iyer, H. K. (1994). Regression analysis: Concept and applications.London: Wadsworth.

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

226 S. Salvatore et al.

Goldman, R., Greenberg, L., & Angus L. (2006). The effects of adding emotion-focused interventions to the client-centered relationship conditions in thetreatment of depression. Psychotherapy Research, 16, 537–549.

Goncalves, O. F., Korman, Y., & Angus, L. (2000). Constructing psychopathol-ogy from a cognitive narrative perspective. In R. A. Neimeyer & J. D. Raskin(Eds.), Constructions of disorder: Meaning making frameworks for psychotherapy (pp.265–284). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Goolishian, H. A., & Anderson, H. (1987). Language systems and therapy: Anevolving idea. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 24, 529–538.

Greenberg, L. E. (1991). Research on the process of change. Psychotherapy Re-search, 1, 3–16.

Greenberg, L. E. (1994). The investigation of change: Its measurement andexplanation. In R. L. Russel (Ed.), Reassessing psychotherapy research (pp.114–143). New York: Guilford.

Greenberg, L. S., & Pinsof, W. M. (Eds.). (1986). The psychotherapeutic process: Aresearch handbook. New York: Guilford.

Greenberg, L. S., & Watson, J. (1998). Experiential therapy of depression: Dif-ferential effects of client-centered relationship conditions and process expe-riential interventions. Psychotherapy Research, 8, 210–224.

Haken, H. (1992). Synergetics in psychology. In W. Tschacher, G. Schiepek, & E.J. Brummer (Eds.), Self-organization and clinical psychology: Empirical approachesto synergetics in psychology (pp. 32–54). Berlin: Springer.

Haken, H. (2006). Information and self-organisation: A macroscopic approach to com-plex systems. New York: Springer.

Handtke, K. K., & Angus, L. E. (2004). The narrative assessment interview: Assess-ing self-change in psychotherapy. In L. Angus & J. McLeod (Eds.), The hand-book of narrative and psychotherapy: Practice, theory, and research (pp. 247–262).London: Sage.

Harre, R., & Gillett, G. (1994). The discursive mind. London: Sage.Hayes, A. M., & Strauss, J. (1998). Dynamic systems theory as a paradigm for

the study of change in psychotherapy: An application to cognitive therapy fordepression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 939–947.

Hermans, H. J. M., & Hermans-Jansen, E. (1995). Self-narratives: The constructionof meaning in psychotherapy. New York: Guilford.

Hill, C. E., & Lambert, M. J. (2004). Methodological issues in studying psy-chotherapy: Process and outcome. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’shandbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (5th ed., pp. 84–135). New York:Wiley.

Holzer, M., Mergenthaler, E., Pokorny, D., Kachele, H., & Luborsky, L. (1996).Vocabulary measures for the evaluation of therapy outcome: Re-studying tran-scripts from the Penn Psychotherapy Project. Psychotherapy Research, 6, 95–108.

Horowitz, M. J. (1987). States of mind: Configurational analysis of individual psychol-ogy (2nd ed). New York: Plenum.

Horowitz, L. M., Rosenberg, S. E., Baer, B. A., Ureno, G., & Villasenor, V. S.(1988). Inventory of Interpersonal Problems: Psychometric properties andclinical application. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 885–892.

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

Psychotherapy as an Intersubjective Dynamic of Meaning-Making 227

Horvath, A., & Greenberg, L. S. (1989). Development and validation ofthe Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36, 223–233.

Kowalik, Z. J., Schiepek, G., Kumpf, K., Roberts, L., & Elbert, T. (1997). Psy-chotherapy as a chaotic process II: The application of nonlinear analysismethods on quasi time series of the client-therapist interaction: A non-stationary approach. Psychotherapy Research, 7, 197–218.

Kossmann, M. R., & Bullrich, S. (1997). Systematic chaos: Self-organizing sys-tems and the process of change. In F. Masterpasqua & P. A. Perna (Eds.),The psychological meaning of chaos: Translating theory into practice. (pp. 199–224). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Lancia, F. (2002). The logic of a textscope. Retrieved August 18, 2007, fromhttp://www.tlab.it/en/bibliography.php.

Lancia, F. (2007). T-LAB: Tools for Text Analysis (Version 5.3.02) [Computer soft-ware]. Roccasecca, Italy: T-LAB di Franco Lancia.

Landauer, T. K., & Dumais, S. (1997). A solution to Plato’s problem: The la-tent semantic analysis theory of acquisition, induction, and representation ofknowledge. Psychological Review, 104, 211–240.

Laura-Grotto, R. P., Salvatore, S., Gennaro, A., & Gelo O. (2009). The unbear-able dynamicity of psychological processes: Highlights of the psychodynamictheories. In J. Valsiner, P. Molenaar, M. Lyra, & N. Chaudhary (Eds.), Dynamicsprocess methodology in the social and developmental sciences (pp. 1–30). New York:Springer.

Lepper, G., & Mergenthaler E. (2008), Observing therapeutic interaction in the“Lisa” case. Psychotherapy Research, 18, 634–644.

Luborsky, L., & Crits-Cristoph, P. (1990). Understanding transference: The CCRTmethod. New York: Basic Books.

Mahoney, M. J. (1991). Human change processes: The scientific foundations of psy-chotherapy. New York: Basic Books.

Mahoney, M. J., & Marquis, A. (2002). Integral constructivism and dy-namic systems in psychotherapy processes. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 22, 794–813.

Mahoney, M. J., & Moes, A. J. (1997). Complexity and psychotherapy: Promisingdialogs and practical issues. In F. Masterpasqua & P. A. Perna (Eds.), The psy-chological meaning of chaos: Translating theory into practice. (pp. 177–198). Wash-ington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Marseden, P. V., (2005). Recent developments in network measurement. In P. J.Carrington, J. Scott, & S. Wassernab (Eds.), Models and methods in social networkanalysis (pp. 8–30). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

McNamee, S., & Gergen, K. J. (Eds.) (1992). Therapy as social construction. Lon-don: Sage.

Mergenthaler, E. (1996). Emotion abstraction patterns in verbatim protocols: Anew way of describing therapeutic processes. Journal of Consulting and ClinicalPsychology, 64, 1306–1315.

Neimeyer, R. A., & Mahoney, M. J. (Eds.). (1995). Constructivism in psychotherapy.Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Downloaded By: [Salvatore, Sergio] At: 08:48 27 May 2010

228 S. Salvatore et al.

Nicolo, G., Dimaggio, G., Procacci, M., Semerari, A., Carcione, A., & Pedone, R.(2008). How states of mind change in psychotherapy: An intensive case anal-ysis of Lisa’s case using the Grid of Problematic States. Psychotherapy Research,18, 645–656

Nightingale, D. J., & Cromby, J. (Eds.). (1999). Social constructionist psychology: Acritical analysis of theory and practice. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Nitti, M., Ciavolino, E., Salvatore, S., & Gennaro, A. (in press). Analyzing psy-chotherapy process as intersubjective sensemaking: An approach based ondiscourse analysis and neural networks. Psychotherapy Research.

Perna, P. A. (1997). Reflections on the therapeutic system as seen from the sci-ence of chaos and complexity: Implications for research and treatment. In F.Masterpasqua & P. A. Perna (Eds.), The psychological meaning of chaos: Translat-ing theory into practice. (pp. 253–272). Washington, DC: American Psychologi-cal Association.

Ramseyer, F., & Tschacher, W. (2008). Synchrony in dyadic psychotherapy ses-sions. In S. Vrobel, O. E. Roessler, & T. Marks-Tarlow (Eds.), Simultaneity: Tem-poral structures and observer perspectives (pp. 329–347). Singapore: World Scien-tific.

Reyes, L., Aristegui, R., Krause, M., Strasser, K., Tomicic, A., Valdes, N., et al.(2008). Language and therapeutic change: A speech acts analysis. Psychother-apy Research, 18, 355–362.

Reynolds, S., Stiles, W. B., Barkham, M., Shapiro, D. A., Hardy, G. E., & Rees,A. (1996). Acceleration of changes in session impact during contrastingtime-limited psychotherapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64,577–586.