Local transformation of a state-initiated institutional innovation: The example of water users'...

Transcript of Local transformation of a state-initiated institutional innovation: The example of water users'...

For Peer Review

Local transformation of a state-initiated institutional innovation: the example of Water Users Associations in an

irrigation scheme in Morocco

Journal: Irrigation and Drainage

Manuscript ID: IRD-09-0034.R1

Wiley - Manuscript type: Review Article

Date Submitted by the Author:

18-Mar-2009

Complete List of Authors: KADIRI, Zakaria; ENA Meknes, Department of Development Engineering KUPER, Marcel; CIRAD Montpellier, Environnements et sociètés FAYSSE, Nicolas; CIRAD Montpellier, Environnements et sociètés ERRAHJ, Mostafa; ENA Meknes, Department of Development Engineering

Keywords: Water Users Associations, Participative Management, Appropriation, Irrigation, Morocco

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

For Peer Review

1

LOCAL TRANSFORMATION OF A STATE-INITIATED INSTITUTIONAL

INNOVATION: THE EXAMPLE OF WATER USERS ASSOCIATIONS IN AN

IRRIGATION SCHEME IN MOROCCOΨΨΨΨ

ZAKARIA KADIRI1∗

, MARCEL KUPER2, NICOLAS FAYSSE

3, MOSTAFA ERRAHJ

4

1Ecole Nationale d’Agriculture de Meknes (ENA), Department of Development Engineering, Meknes,

Morocco; UMR G-EAU, Montpellier, France

2 Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement (CIRAD),

UMR G-EAU, Montpellier, France; Hassan II Agronomy and Veterinary Medicine Institute, Rabat,

Morocco

3 Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement (CIRAD),

UMR G-EAU, Montpellier, France; Ecole Nationale d’Agriculture de Meknes (ENA), Meknes, Morocco

4 Ecole Nationale d’Agriculture de Meknes (ENA), Department of Development Engineering, Meknes,

Morocco

ABSTRACT

The international debate on participatory management and irrigation management transfer has

mainly focused on ex-ante/ex-post evaluations that rely on quantitative performance indicators

to measure the failure or success of management transfer and the functioning of Water Users

Associations (WUA). This article focuses on the appropriation by farmers of state-initiated

water users associations illustrated by the case of the Moyen Sebou irrigation scheme in

Morocco. This scheme, which was designed for agency-managed water distribution, was

implemented at the height of the debate on participatory management in the early 1990s, and

was transformed into a farmer-managed irrigation scheme. The results revealed the gradual

adoption of the water institutions (WUAs and the federations of WUAs) by farmers, who

continuously crafted and adapted rules for the management of water distribution, collection of

water fees, and governance of the irrigation scheme. In addition, there were a number of indirect

Ψ

Transformation locale d’une innovation institutionnelle: le cas des associations d’usagers de l’eau

agricole d’un périmètre irrigué au Maroc

∗ Correspondence to: Zakaria KADIRI Ecole Nationale d’Agriculture de Meknes (ENA), Department of

Development Engineering, BP S/40 Meknes, Morocco; UMR G-EAU, F-34398 Montpellier, France. E-

mail: [email protected]

Page 1 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

2

spin-offs generated by the collective learning process in terms of leadership, collective action,

local democracy and local development.

KEY WORDS: Water Users Associations, Irrigation, Participative Management, Appropriation,

Morocco

RESUME

Le débat international sur la gestion participative et le transfert de la gestion de l’eau

d’irrigation était dans le passé surtout centré sur des évaluations ex-ante/ex-post, mettant en

jeux principalement des indicateurs quantitatifs de performances pour mesurer l’échec ou la

réussite de ce transfert. Notre article analyse l’appropriation des associations d’usagers de l’eau

agricole, mises en place par l’Etat, par les agriculteurs. Nous illustrons cela pour le périmètre du

Moyen Sebou, qui est géré depuis sa mise en eau par des Associations des Usagers de l’Eau

Agricole mises en place par les pouvoirs publics. Nous verrons comment l’adoption et la

transformation des règles de fonctionnement créent une dynamique collective autour de

l’aménagement et parfois autour d’autres organisations collectives que celles de l’eau

d’irrigation.

MOTS CLES: Associations des Usagers de l’Eau Agricole, Irrigation, Gestion participative,

Appropriation, Maroc

INTRODUCTION

The international debate on participatory irrigation management (PIM) and irrigation

management transfer (IMT), launched by authors like Coward (1980), influenced the actors

concerned with irrigation water management (financial donors, public authorities, water users

and researchers). Certain countries were heavily indebted and unable to bear the costs of

operating and maintaining large-scale irrigation schemes. Governments were thus forced to

undertake major reforms of their irrigation management policies. These reforms were often

implemented under the influence of donors for financing new irrigation schemes or

rehabilitating old schemes. There was often little conviction on the part of the governments

concerned as regards the legitimacy of decentralizing its competence in irrigation

Page 2 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

3

(Bandarogada, 2006; Mollinga and Bolding, 2004). The international debate on PIM/IMT led to

the creation of Water Users Associations (WUA). This institutional innovation was often a top

down creation with no real participation by the future ‘beneficiaries’.

The experiences of various countries in IMT have been analyzed and evaluated during the

last two decades, using ex ante – ex post or with/without IMT analyses (Samad, 2002; Shah et

al., 2002; Merrey et al., 2002). These classical analyses were mainly based on quantitative

indicators, such as economic performance, the impact on cropping intensities and yields, the

return on investment and technical efficiency (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2007). Samad (2002;

2006) asserted that the indicators mostly focused on state expenses, the quality of the irrigation

service, the level of maintenance of the physical infrastructure, and cropping intensities and

yields. Naik and Kalro (2000) stated that the most widely criteria considered were the increase

in agricultural production, the equitable distribution of water, the sustainability of the system

and the reduction in the state’s expenses, and even protection of soils against salinity. While the

results of these analyses allowed some of the conditions for the success of IMT (political

commitment, financial capacity of WUAs, internal democracy etc.) to be highlighted, these

analyses did not capture the capacity for transformation of the initial institutional model. The

institutional innovation proposed by the governments was exposed to changes, resistance and

negotiation by the different parties involved, and thus transformed locally (Mollinga and

Bolding, 2004).

In this paper, we argue that evaluation of PIM/IMT based only on quantitative indicators

is insufficient. It does not allow understanding what farmers made out of the institutional

innovation. Farmers integrate the objectives of irrigation water management in a larger set of

objectives such as local development, modifying power relations, learning teamwork and

collective management, and acquiring new local skills. We therefore analyzed the farmers’

appropriation of the WUAs. Far from the failure or success of PIM as a model of participatory

management, which is generally the result of more classical analyses, our study of the

appropriation of WUAs enabled us to analyze the local transformation of this institutional

innovation. Our underlying hypothesis is that the appropriation of this innovation is an essential

step on the way to sustainability of the scheme. Appropriation not only concerns management of

irrigation water, but also agricultural development, the establishment of new rules, local

governance, collective learning, among others.

Our analysis concerns the 6,500 ha Moyen Sebou irrigation scheme in Morocco. Morocco

participated actively in the international debate on IMT, as evidenced by the 1995 Marrakech

PIM conference. The State created a considerable number of WUAs in a vast number of large

and small scale irrigation schemes. About 15 years later, the results are often considered

Page 3 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

4

disappointing (El Alaoui, 2004; Herzenni, 2002). At the same time, PIM is no longer presented

as a priority in recent political directives, and the PIM model is being replaced by public-private

partnerships (Houdret, 2008). The Moyen Sebou scheme is particularly interesting to study the

way farmers appropriated institutions for the management of the irrigation scheme. Firstly, like

in many other perimeters in the world, the farmers did not participate in the design of the

system; their participation in the management began only after the infrastructure had been

constructed and water delivery had started. During the technical design of the project, the

adequacy of the management institutions with regard to the social organization of the farmers

was not really questioned. Indeed, the feasibility study was undertaken in 1984, before the

debate on PIM began. It proposed a classical large-scale irrigation set-up with central state-

controlled management and heavy irrigation infrastructure (Fornage, 2006). However, the

scheme was implemented right in the middle of the national and international debate on PIM in

1994. The financial donor thus made the creation of WUAs a precondition for financing the

scheme. This meant that the project unit was forced to adapt the feasibility study to the new

participatory directive. Secondly, despite all these problems, the WUAs in this scheme are in

fact functional (Bekkari et al., 2007; Kadiri 2008), which enabled us to study the modalities of

appropriation of a ‘top-down’ institutional innovation and how the farmers transformed this

innovation.

METHODOLOGY

Analytical framework

At first sight, using the concept of appropriation in the context of a top-down state

imposed innovation like WUAs may appear to be a paradox. However, we believe that the

concept is particularly well suited to our analysis, if we consider the transformation of the

WUAs to fit local conditions to be a sign of appropriation. We followed the definition of

Serfaty-Garzon (2003), who states that appropriation means to make something one’s own; that

is, to adapt an object to oneself, and then to transform it into a support for self expression.

Appropriation is thus both about apprehending an object and, at the same time, about crafting

action dynamics out of the material and social context. On the basis of often contradictory

individual practices, a ‘cooperative attitude’ thus materializes that reorganizes and integrates

these practices, thereby developing a process of inter-structuring of individuals and institutions

(Lanneau, 1975).

Following Ostrom (1992), we consider the WUA as a visible organization that manages

Page 4 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

5

water, but also as a producer of ‘invisible’ institutions. The term ‘institution’ refers to a set of

rules truly put into practice by a set of individuals to organize repetitive activities that will affect

the individuals themselves, and possibly others. Ostrom adds that the challenge lies in the

definition of the rules that govern the distribution of water and the functioning of the network,

and in the organizational structure in charge of their implementation. Therefore, an irrigated

system requires organizations to set up these rules. We used the crafting and the adaptation of

rules of the WUAs as the main entry point to the analysis. We first analyzed current agricultural

development in the Moyen Sebou scheme in order to situate water management in the wider

context of local development. We then analyzed the financial situation of the WUAs, as we

believe that the survival of collective organizations, such as WUAs, depends to a large extent on

the adoption of a financial system that enables autonomous management. Changes in rules

concerning the payment of water fees reveal the efforts made by the farmers to meet this

objective. The last part of our analysis emphasizes another aspect of the transformation of the

innovation: the creation of new competencies, social learning, and investment in domains other

than irrigation management.

The present study was based on a survey of 60 farms in four WUAs belonging to the

Moyen Sebou scheme. In addition, semi-directive interviews were conducted with resource

persons, including board members of WUAs and irrigation federations, and technicians of

government agencies.

Site location

The Moyen Sebou irrigated perimeter is situated in the North of Morocco along the

Sebou River, about 60 km North-West of the city of Fes. This perimeter was the first national

experience of a modern farmer-managed irrigation scheme. The Ministry of Agriculture

implemented the first phase of the scheme (6,500 ha) between 1995 and 2001 (sectors II and

III). The project was designed to subsequently include other areas located both downstream and

upstream of the current scheme. It was financed jointly with the French Development Agency.

The aim of the project was to intensify farming systems and increase farmers’ incomes from

130 to 1,200 €/ha/year. The project should also create employment by increasing labor

requirements from 25 to 150 man days/ha/year. A further aim of this integrated project was to

improve living conditions of the local population through electrification and roads.

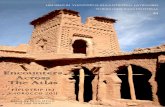

This project led to the creation of 12 WUAs, belonging to two irrigation federations, each

of which managed one irrigation sector (Figure 1). The initial institutional set-up foresaw the

distribution of tasks between WUAs and the federations. Both were to employ staff for

irrigation management. El Alaoui (2004) reported that the federation was to be responsible for

Page 5 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

6

the common hydraulic infrastructure (pumping stations, primary and secondary irrigation

network), while the WUAs were to be responsible for the distribution of water and the

maintenance of the tertiary network.

Figure 1 ABOUT HERE

The Moyen Sebou scheme covers a wide variety of situations. Sector II was completed

and started irrigation from 1998-1999 onwards. It is in a plain and includes four WUAs with a

single pumping station on the Sebou River and three smaller lifting units. Sector III was

completed two years later and includes eight WUAs. It extends for more than 20 km along the

Sebou River and has more hydraulic equipment than the first sector (three pumping units on the

Sebou River and six lifting units), and consequently has higher maintenance costs. The WUAs

also differ in terms of irrigation experience. In some WUAs, the majority of farmers had never

previously practised irrigation, while in others, farmers grew historically irrigated crops like

mint, watermelon and potatoes along the river using individual pumping units. Kadiri (2008)

identified three types of farms: i) smallholdings (69% of the farmers interviewed) with less than

3 ha located within the irrigation perimeter. These farmers often rented in land to compensate

for the small size of farms. They generally grew cereals on one or two plots located outside the

irrigated perimeter, associated with extensive sheep rearing, ii) medium-sized farms (3-10 ha

located within the perimeter). These farms diversified their farming systems after the

introduction of irrigation, in addition to cereals, they produced horticultural crops and forage for

milk production, and iii) large landholdings (more than 40 ha). The majority of the land

belonging to these big farms was located outside the perimeter, and was mainly under cereals.

Some of these farmers also had significant off-farm incomes.

RESULTS

Disappointing scheme performance based on standard quantitative criteria

One important aim of the project was to significantly improve agricultural development:

with an average intensification of 120%, the introduction of industrial crops with high added

value (horticultural crops, sugar beet, fruit orchards) and the development of dairy production.

However, almost 10 years after the implementation of sector II (and 5 years after

implementation of sector III), the actual cropping patterns are far from reaching these goals.

Farmers, most of whom had no previous experience in irrigation, had to adopt new agricultural

Page 6 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

7

and irrigation practices from one day to the next, while shifting from rain-fed to irrigated

agriculture. In addition, project management focused mostly on accompanying the WUAs in

managing the hydraulic infrastructure, without investing the same effort in accompanying the

farmers in their agricultural development.

Table I shows the cropping patterns and intensities of two WUAs in each irrigation

sector. Cropping intensities ranged between 83 to 101%. Farmers continued to grow cereals,

which occupied 60% of the cropped area. However, they intensified their agricultural practices

and obtained higher yields than with rain-fed cereals. Farmers located along the Sebou River

had cultivated crops such as watermelons and melons before the implementation of the scheme.

During the first few years of the scheme, farmers extended the cropped area under melons and

water melons. However, during the last three years, the irrigated area decreased sharply due to

emerging awareness of the pollution of the Sebou River. Farmers in Loudaya even complained

that the mint grown in the area, which historically had an excellent reputation in northern

Morocco, has become less attractive in the marketing networks.

Table I ABOUT HERE

However, in spite of the limited agricultural development at scheme level, there are some

encouraging signs. Firstly, farmers in sector II recently introduced new crops, such as sugar beet

and silage maize. In 2007/2008, this only concerned small areas, as farmers were still testing the

feasibility of the new crops (Table I). In 2008/2009, farmers extended experiments to 150 ha of

sugar beet and 100 ha of silage maize. The extension of silage maize was stimulated by the two

dairy cooperatives in sector II, each of which collects about 4,000 litres/day. Two more milk

cooperative started functioning in 2008 (one in each sector), showing the growing interest for

milk production. Secondly, farmers in both sectors extended citrus orchards. However, the

orchards are mainly located on the river banks, particularly in sector III. In order to limit the risk

of water shortage, farmers irrigated the orchards with water from both the irrigation scheme and

individual pumps. This had a direct impact on water sales, as sector III consumed at most 2

million cubic metres a year while sector II consumed 12 million cubic a year.

The progressive expansion of citrus orchards and forage crops linked to rapidly

increasing dairy production are currently the farmers’ two preferred development pathways.

However, it will take time for these pathways to be implemented on a large scale. For the time

being, low cropping intensities and the prevalence of low value-added crops mean that farmers’

revenues are not high enough (the net margin of 1 ha of cereals is around 600 €/ha, while for

potatoes it can reach 3,400 €/ha), and water sales are limited, which in turn affects the

Page 7 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

8

sustainability of the WUAs and irrigation federations.

Local transformation of the original model

An adaptive financial system with rules that fit each irrigation sector

The current tariff structure used in the Moyen Sebou irrigation scheme is based on a two-

part tariff: a fixed sum per hectare (27 €/ha/year for sector II and 9 €/ha/year for sector III) and

volumetric charges (0.023 €/m3 for sector II and 0.027 €/m

3 for sector III). These rates are quite

different from those originally proposed by the project. The project suggested that volumetric

charges would cover electricity charges, minor maintenance operations, and the cost of the staff

for water distribution, while fixed charges would pay for depreciation of the infrastructure and

for larger maintenance works. To this end, the project proposed initial fixed charges at a rate of

45 €/ha for the first year. These charges were to go up gradually to reach 145 €/ha by the end of

the 3rd

year. However, the farmers refused to pay this amount, for three main reasons. In the first

place, the actual cropping patterns did not enable them to pay a high price for water. It was

difficult for them to grow higher value crops due to the poor quality of the irrigation water.

Secondly, during the implementation phase of the scheme, the farmers did not cultivate their

land for which they were paid a small compensation (45 €/ha/year), an amount they considered

largely insufficient. Four years without agricultural revenues from the lands included in the

scheme led to decapitalization on many farms (sale of livestock, for instance). Thirdly, farmers

complained about the quality of the works related to land levelling and to the lay-out of the

open-channel network. ‘My land was not levelled; look at this plot, I never irrigated it’ said a

farmer in sector III. This meant that not only the fixed charges were lower than originally

intended, but for many years they were not even paid by farmers.

Figure 2 shows that the coverage rate of the volumetric part is about 83% in sector II. The

relatively high percentage obtained by the two institutions (federation and WUAs) was due to

coercive measures, such as cutting off water to non-payers and an aggressive commercial

policy: ‘the farmers should ask for more water and we should be able to obtain the water fees,

which is our only source of income’ said the president of one of the federations. Somewhat

along the same lines, to address the problem of non payment of water bills, the federation of

sector II gave its technical director the task of making sure that all farmers who asked for water

had paid all their water bills to the federation. This was to avoid any favouritism by the

presidents and members of the WUA boards.

Figure 2 ABOUT HERE

Page 8 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

9

Interestingly, the collection of water fees took different forms in the two sectors. While

sector II maintained quarterly payments throughout, sector III abandoned this system after two

years, when the board of the federation found itself confronted with many farmers who had not

paid their fees. In addition, the federation had to pay their own staff and their electricity bills on

a monthly basis. Accordingly, during the 3rd

year of functioning, the federation obliged lessees

to pay the total bill before irrigation, while regular farmers (members of the WUAs) had to pay

50% of the water bill before irrigation. ‘This allowed the federation to obtain an advance of 1

million DH during a single campaign’ reported a member of the board of the federation. At the

beginning of the 2005-2006 agricultural campaign, the federation extended the obligation of

paying the total water bill before irrigation started to all farmers.

The collection of the volumetric water fees thus revealed not only an encouraging

recovery rate, but also the continuous adaptation of the rules to fit the situation of each sector in

order to improve its recovery rate. This turned out to be much more difficult for fixed charges,

as farmers continued to be very reluctant to pay them. However, in 2007, nine years after the

implementation of the irrigation scheme in sector II, the board of this federation was confronted

with serious breakdowns of their main pumping station. It was now clear to them that

recovering fixed charges would be the best way to balance their accounts. Accordingly, at the

beginning of the 2007/2008 agricultural year, the federation obliged irrigators to pay the fixed

charges that were due for the four preceding years (under the threat of cutting off their water

supply), in four instalments. The first two instalments had to be paid directly after the harvest of

cereals and the other two with the volumetric quarterly bills. By the end of 2008, the federation

had recovered a little over 180,000 €, representing almost half the total amount owed to the

federation.

These adaptations -and even transformations- of the rules governing the collection of

water fees illustrate the vitality of the irrigation institutions, with good results obtained for the

volumetric water charges. The recovery of the fixed charges was much less successful, despite

the recent success of the federation of sector II. This achievement should not mask the fact that,

according to the calculations of the project team at the end of the 1990s, 145 €/ha/year would be

required to cover depreciation of the installations and major maintenance jobs, while actual fees

are only 45 €/ha/year. Along with the reasons put forward by farmers making it impossible for

them to pay fixed charges at the beginning of the project when they did not have sufficient farm

income, one can also question the choices made regarding the hydraulic infrastructure with

large technically advanced pumping stations. The pumps are difficult and costly to maintain,

and are not particularly suitable for farmer management.

Page 9 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

10

Farmers and employees in quest of technical competence

Conceived according to the logic of large-scale irrigation projects, the Moyen Sebou

irrigation scheme faces the same constraints as the other schemes in Morocco, such as

respecting the planned water turns, managing night irrigation, and the operation and

maintenance of pumping stations. The WUAs and irrigation federations hired personnel, such as

gate keepers, for the management of water turns, network chiefs to schedule the water turns of a

WUA, technicians for the operation and maintenance of pumping stations, and a technical

director responsible for scheduling and managing water turns of the federation. The farmers’

organizations organized competitive recruitment procedures, and hired mainly young graduates

from the region. This team of young people is playing an increasingly important role in the

management of the irrigation system. For example, during rush hours, gate keepers and network

chiefs encourage the farmers located along the river to use their individual motor-pumps, so that

farmers further away from the river can irrigate using the network. Such examples are frequent

and are signs not only of the possibilities of mutual aid between farmers, but also of a sense of

initiative and of the increasingly important role played by the technical team. The team also

handled the problem of night irrigation (the scheme is located in the Rif’s foothills,

characterized by cold winters), as farmers find it difficult to find laborers willing to work at

night. To avoid that the same farmers always irrigate at night, the technical team: 1) provides

big landowners with 24-hour water shifts, 2) alternates day and night irrigation for other farmers

on a first come, first served basis.

Through their autonomous management of the scheme, the farmers’ associations and their

employees put in place rigorous and straightforward procedures for water demands and

irrigation scheduling. They simplified administrative procedures while maintaining a sufficient

degree of freedom to adapt the rules in place. The day-to-day management is more and more in

the hands of the technicians, who have learned to deal with routine management practices, but

who react also quickly to emergencies (breakdowns of canals, pumps). This underlines the

importance of the creation of new competences by technicians and administrators as forms of

appropriation.

Irrigation institutions: changing collective dynamics and local governance

Analysis of the governance practised by the irrigation federations and the WUAs revealed

a long learning process, both for the irrigation communities and for the leaders. The WUAs

only organized annual general assemblies when irrigation started in 1999, despite the fact they

had been created by the project in 1995. These general assemblies are not only an opportunity to

Page 10 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

11

promote the collective dynamics of the WUAs, but represent at the same time a threat for the

management boards, as they risk being overthrown by opponents. Local democracy is often a

harsh school for irrigation leaders. The assemblies have evolved considerably over time, with

rich, lively debate concerning both internal problems (collection of water fees, water turns), and

the relationships with the irrigation federation. Serious issues were often confronted. In one

assembly, for example, an ex-president of a WUA was excluded because of financial

mismanagement. Voting for the board members of WUAs increasingly took place through

secret ballots instead of hand raising, sometimes to the considerable surprise of some of the

board members who were used to unopposed elections. There was even a case of two different

lists proposed for the election of the board of a WUA. This operation was perfectly in

accordance with the internal rules and regulations of the WUA, which requires a secret ballot,

even though they did not stipulate the possibility of voting by list. This revealed the capacity of

WUAs to continually interpret the regulations. However, there is also the example of a WUA

with unchanged leadership since the beginning, unwilling to organize general assemblies.

Collective learning and new leadership go hand in hand. The collective learning

described above was accompanied by individual learning by board members. In his analysis of

the current transformation of rural societies in the high plateaus of eastern Morocco, Tozy

(2002) distinguished three leader profiles: 1) those with close relationships with the Makhzen1,

2) entrepreneurs and 3) young leaders with formal education. This typology partially includes

the leaders of the federations and WUAs in the Moyen Sebou, who often display a mixture of

these characteristics. The elected representatives of federations and WUAs are generally present

in the board of other farmers’ organizations (dairy cooperatives, for instance), but also in

municipal councils. Generally, they have many contacts and networks, and their presence at the

head of the irrigation institutions underlines their local importance.

It is clear that having leaders who have multiple responsibilities could damage the health

of the WUA due to hidden logics. Ostrom (1992) called these logics ‘incitements’, which are

not only material and financial but can include 1) material advantages, 2) personal gratitude,

prestige, 3) smooth technical running of the network, 4) social services, religious feelings,

patriotism, 5) personal comfort in social relationships, reduction of conflicts between people, 6)

feelings of belonging to a community. However, the WUA model as it currently exists in the

Moyen Sebou scheme probably needs this type of leaders to overcome difficulties that could not

be handled by people who do not have the necessary contacts, experience, or skills. This is in

agreement with Shah (1996), who linked the success of collective action to the existence of an

active minority in which the leader in particular, plays a very important role as a catalyst in the

1 Word in Arabic designating the Moroccan governing elite

Page 11 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

12

implementation of collective action. However, the profiles of leaders are constantly changing.

The project director described the change in profile from that of leaders in place at the

beginning of the project (university lecturers and civil servants who still had family farms in the

area) to that of their replacements in one of the two federations: ‘the old board was made up of

intellectuals who really understood the future of the federation; when we discussed with them,

we had the impression we were talking to one of our own. Nowadays, the farmers do not

necessarily need such leaders, but rather people who are permanently present, who live with

them’. Shah (1996) reminds us that it is difficult to train leaders, as they are trained at the same

time as the farmers’ organization, and not independently.

We now take a step back for a broader look at community organizations. Using one of the

communities as an example, we identified four collective organizations. These were the WUA

and the dairy cooperative, both of which are directly connected with the irrigation scheme, but

also two other associations for local development, mainly promoted by the younger generation.

The two latter were both created in 2003, five years after the start of the irrigation project. These

two associations organize sporting events, participate in summer camps for youngsters in the

area, and plan revenue generating projects for the women of the community. The associations

reflect the recent dynamics of the Moroccan associative movement since 2000. However, we

believe that the irrigation project played an important role as a catalyst. Indeed, before the

project started, with the exception of a defunct cereals cooperative, no associations existed in

the area. Moreover, the young community members are presently board members of all four

organizations. Our hypothesis is that the irrigation federations and the WUAs were a school in

which these young people learned about associative life, collective action, and had contacts with

the administration and the authorities. The president of the Sebou federation told us that before

the project began, there was no real working contact between the three ethnic groups in the area,

whereas now they work together in a formal framework that enables them to get to know each

other. In our opinion, this landscape of collective dynamics deserves to be mentioned, but

without imagining it can be generalized given the wide range of situations found in the Moyen

Sebou scheme.

Perspectives shared between the different actors and adopted by the farmers

Water to finance milk. During the last general assembly, the irrigation board of federation

II proposed to adapt the regulations of the federation in order to be able to finance certain

activities of the milk cooperatives in the sector. They made this proposal because they were

conscious of the interest of milk production, which is based on forage crops that can survive

irrigation with badly polluted water. They were in a position to make this proposal as they

Page 12 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

13

presented financial accounts that were well balanced. The financing will take the form of

interest-free loans with repayment facilities. The federation’s underlying hypothesis is that

increased dairy production will lead to higher cropping intensities (forage crops) and increased

water demand. Rather than financing individual farmers, they believe that the financial support

should go to the two cooperatives. The measures include first the purchase of a silage cutter to

encourage farmers to practise maize ensilage, which is showing an upward trend in the scheme.

Second, the renewal of the animal feed machine, which was originally supplied by the project

but requires too much maintenance. In this way, the federation transformed its role from being

the manager of irrigation water into being a catalyst for regional agricultural development,

without betraying its core principle: increasing the collection of water fees to ensure the

sustainability of the irrigation scheme.

Questioning the technical design and appropriation of the hydraulic system. The

hydraulic equipment of the Moyen Sebou, like that of the other Moroccan large-scale irrigation

schemes, imposes heavy constraints both in terms of maintenance (breakdowns of pumping

stations) and in the management of the water turns, especially during peak demand periods and

when a pumping station serves more than a single WUA. Some WUAs are already thinking

about re-engineering their equipment, replacing their big pumps by smaller ones. The reason put

forward by some WUAs is that they wish to be independent of the other WUAs in managing

water turns. For other WUAs, replacement will decrease maintenance costs and facilitate water

management. In addition, some WUAs wish to include in the water turns land that is officially

located outside the borders of the project.

The (projected) changes in the hydraulic configuration of the project, adapting it to local

needs, and the inclusion of agricultural development in the mandate of the irrigation institutions,

are further illustrations of the appropriation process of the scheme by the farmers’

organizations.

DISCUSSION

The results of our analysis showed that the appropriation of the irrigation scheme by farmers’

organizations was linked to the need to come to grips with water management (adoption of the

innovation) on one hand, and to the capacity of farmers to relate to the other aspects of

agricultural development (transformation of this innovation) on the other hand. We also showed

the different ways in which this process took place in the different WUAs. Below we discuss the

implications of this appropriation process firstly for the debate on the irrigation management

Page 13 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

14

transfer model, and secondly for the formulation of public policies.

Local appropriation of an imported blue print

In our view, the adoption and transformation process of the imported blueprint model we

described above is a social construct, in agreement with Crozier and Friedberg (1977), who

asserted that collective action is a social construct. In the Moyen Sebou scheme, the process was

not spontaneous and certainly did not happen by chance. It was the result of cooperation

between interdependent actors who engaged in the construction of rules to manage water and to

develop regional agriculture. Due to local particularities, the results of this process are very

heterogeneous across WUAs. It is probably not appropriate to speak of the success or failure of

this process. While failure in some WUAs, which is often linked to local patterns of democracy,

may appear to be temporary, in others, success is still fragile. Indeed, appropriation occurs over

time, and the learning processes will need to be further developed before judging the success or

failure of the Moyen Sebou experiment. Ranvoisy (2000) claimed that farmers have to be

psychologically prepared and find a justification for investing a lot of energy in participatory

water management. This aspect should not be underestimated. It is very tempting for farmers to

let the state manage the scheme, i.e. revert to the traditional agency-managed scheme, while

criticizing the poor performance of the state agency. The farmers also need to acquire a range of

skills to manage the activities of WUAs. Without allowing for this period of learning, there is a

high risk of obtaining only partial and reluctant involvement of farmers in the association

(including the risk of massive desertion when the first difficulties appear in the life of the

association). It is consequently important to accept the need for a learning period and to be

prepared to harvest the fruits of participatory management only in the second generation of

farmers.

On the other hand, there is a real risk that in carrying out a classical ex-post evaluation of

the performance of the Moyen Sebou scheme, policy makers and administrations will not take

into account the elements that we propose here concerning the appropriation process or the local

dynamics. Indeed, in Morocco today, public discussion is more oriented towards another

blueprint model: public-private partnerships, which would mean ‘zapping’ from one blueprint

model to another. Based on our analysis of the Moyen Sebou experiment, we argue that the

problem is neither in the model nor whether it fits rural realities in Morocco, but rather in the

way society tends to look for miracle solutions to societal problems (Pascon, 1980). The

farmers’ organizations in the Moyen Sebou will doubtless continue to alternate good, pragmatic

management practices with periods of crises. However, whatever the management model

proposed to them, after all these years of hydraulic independence, they will certainly be capable

Page 14 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

15

of negotiating their position and of influencing decisions that concern them. This emancipation

is, arguably, the greatest fruit of ten years of participatory management in the Moyen Sebou.

It would be interesting to compare the Moyen Sebou experiences with experiences

elsewhere in Morocco, or in other North African countries. The WUAs in large-scale irrigation

schemes in Morocco remain generally non-existent, as the enabling conditions (political

commitment, financial capacity, internal democracy) were not in place (El Alaoui, 2004). In

medium and small-scale irrigation schemes, WUAs generally functioned only for a short while

in order to receive state subsidies for canal lining. However, Bekkari et al. (2007) showed

recently evidence of communities in the Middle Atlas mountains appropriating the WUA

platform in order to transform the traditional management model and improve water scheduling.

In Tunisia, WUAs also show some interesting features, for example related to maintenance

(Frija et al., 2008). An analysis focused on the appropriation by farmers of the WUAs as an

institutional innovation would probably produce interesting evidence on the learning processes

in these cases.

Will better appraisal of the dynamics created by the appropriation of WUAs lead to the

reformulation of public policies?

Certain local leaders mentioned that when the Moyen Sebou project started, farmers were

more interested in sharing the honourable positions on the boards, while the project leaders and

the state focused on the negotiation and the implementation of the formal agreements between

the state, the WUAs and the federations (the mandate of these organizations, their status, and

internal rules and regulations). These legal aspects are certainly of major importance for the

satisfactory functioning of the farmers’ organizations. However, by taking these aspects as the

major focus of discussions between stakeholders, rather than considering them as a means for

the management of the scheme and of agricultural development, these discussions probably

overshot their target. The focus on legislation and water did not leave sufficient leeway for the

WUAs and federations to include agricultural development in their mandate. It is only recently

that the WUAs and their federations have become major partners in agricultural development,

and have acquired a certain legitimacy to discuss development. This is in agreement with Shah

et al (2002), who suggested that, in the case of family-based agriculture, the WUAs with the

highest chance of succeeding are those that lead farmers to increase their productivity and

income. Interestingly, the WUAs and federations in the Moyen Sebou integrate activities related

to agricultural development, and subsequently pass them on to more specialized organizations.

This was the case with the introduction of sugar beet, which was first promoted by one of the

WUAs by cultivating 6 ha as a pilot experiment in 2006/2007. Once the area under sugar beet

Page 15 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

16

began to extend and the farmers’ interest was awakened, a sugar beet association was created to

coordinate and manage relations with the sugar industry. This confirms our view that it is

necessary to take a more global approach in the debate on participatory management and not to

only focus on water management.

In this changing context, there is no doubt that WUAs are gradually becoming partners in

discussions concerning local development policies. In a period of only a few years, farmers

have evolved from cultivators of rain-fed crops to administrators of an irrigation scheme

covering several thousand hectares. In fact, we are witnessing the transformation of the status of

a ‘peasant’ (fellah) to a more professional status of ‘farmer’, or even as Hammoudi (1997) put

it, the evolution from subjects to citizens. Similarly, certain WUAs show many of the same

signs of growing autonomy as those already observed in a number of pastoral cooperatives in

Morocco (Tozy, 2002). Amongst these signs, we cite the issue of representativeness, the

availability of resources and means, the possibility of making decisions, learning, and the

impact on the local environment. The rapid evolution of the associative sector in Morocco, with

more than 30,000 local associations registered (Abbadi, 2004) shows that the positive trend of

these agriculture-based organizations is not an isolated phenomenon.

CONCLUSION

The aim of this study was to analyze the process by which farmers appropriated state-created

WUAs in an irrigation scheme in Morocco, thereby contributing to the international debate on

participatory management. This institutional innovation or blueprint model, which was imposed

by authorities and the donor, was gradually adopted and transformed by farmers to fit their

objectives and capacities. We showed that classical quantitative analysis of the irrigation

performance is insufficient to understand the impact of an irrigation project, as it does not

reflect the dynamics created around water and around the irrigation institutions in the Moyen

Sebou. It is too early to confirm our hypothesis that the appropriation of this institutional

innovation is essential for the sustainability of the scheme. However, we showed that farmers’

organizations are on the road to autonomy and that the emancipation of farmers undoubtedly

represents an important building block in the development of the area.

REFERENCES

Page 16 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

17

Abbadi D. 2004. Gouvernance participative locale au Maroc. Ed. Fedala, Mohamedia, Morocco,

130pp.

Bandarogada DJ. 2006. Limits to donor-driven water sector reforms: insight and evidence from

Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Water Policy 8: 51–67.

Bandyopadhyay S, Shyamsundar P, Xie M. 2007. Yield impact of irrigation management

transfer: story from the Philippines. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4298.

Bekkari L., Kadiri Z., Faysse N. 2007. Appropriations du cadre de l’Association des Usagers

des Eaux Agricoles par les irrigants au Maroc : analyse comparative de cas au Moyen

Atlas et Moyen Sebou. In Kuper M., Zairi A. (eds.), Proceedings of the 3rd seminar on

Water Saving in North Africa. Nabeul, Tunisie, 2007. url: http://halshs.archives-

ouvertes.fr/SIRMA2007/fr/

Coward WE. 1980. Irrigation Development: Institutional and Organizational Issues. In Coward

W.E., Irrigation and Agricultural Development in Asia, Perspectives from the social

sciences. Ed Cornell University press, Ithaca, New York: 15-27

Crozier M, Friedberg E. 1977. L’acteur et le système. Ed. Seuil, Paris, France, 500 pp.

El Alaoui M. 2004. Les pratiques participatives des associations d’usagers de l’eau dans la

gestion de l’irrigation au Maroc : étude de cas en petite, moyenne et grande hydraulique.

In Hammani A., Kuper M., Debbarh A. (eds), Proceedings of the Seminar on the

Modernisation of Irrigated Agriculture, 19-23 April 2004, Rabat, Morocco.

Fornage N. 2006. Maroc, zone du Moyen Sebou : Des agriculteurs au croisement des

contraintes locales et des enjeux de la globalisation. Revue Afrique contemporaine 219

(3), pp 43-46.

Frija A, Speelman S, Chebil A, Buysse J, Van Huylenbroeck G. 2008. Assessing the efficiency

of Irrigation Water Users’ Associations and its Determinants: Evidence From Tunisia.

Irrigation and Drainage. DOI: 10.1002/ird.446

Hammoudi A. 1997. Master and Disciple: The Cultural Foundations of Moroccan

Authoritarianism. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, U.S., 195 pp.

Herzenni A. 2002. Les ORMVA, les AUEA et la gestion participative de l’irrigation. Terre et

vie 59/60, Août/Septembre 2002. url: www.terrevie.ovh.org/ORMVA.pdf

Houdret A. 2008. Privatisation of irrigation water services: conflict, mediation and new

partnerships in the ElGuerdane project, Morocco. Proceedings of the 13th IWRA World

Water Congress 2008. 1-4 September, Montpellier, France

Kadiri Z. 2008. Gestion de l’eau d’irrigation et action collective : cas du périmètre du Moyen

Sebou Inouen Aval. Publications thèse de Master of science du CIHEAM-IAMM 95.

Montpellier, France. 2008.

Page 17 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

18

Lanneau G. 1975. L’entraide et la coopération au village, in : D. Fabre et J. Lacroix (éds.),

Communautés du sud, Tome II, 10-18, Collection « Série 7 », U.G.E., p 435-499

Merrey DJ Shah T, Van Koppen B, De Lange M, Samad M. 2002. Can irrigation management

transfer revitalise African agriculture? A review of African and international experiences.

In Private irrigation en Afrique sub-saharienne Africa. Proceedings, 22-26 octobre 2001,

Accra. Ed IWMI.

Mollinga P, Bolding A. 2004 (Eds.). The Politics of Irrigation Reform: Contested Policy

Formulation and Implementation in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Ashgate, Hants, UK.

319 pp.

Naik G, Kalro A. H. 2000. A methodology for assessing impact of irrigation management

transfer from farmers’ perspective. Water Policy 2(6), pp 445-460.

Ostrom E. 1992. Crafting Institutions for self-governing irrigation systems. ICS Press, Institute

for Contemporary Studies. San Francisco, 111 pp.

Pascon P. 1980. Le Maroc souffre des modèles importés. In : P. Pascon. Etudes rurales : idées

et enquêtes sur la campagne marocaine. Société marocaine des éditeurs réunis, Rabat,

Morocco, 289 pp.

Ranvoisy M. 2000. Rôle des associations d’irrigants au Maghreb (Maroc et Tunisie) dans le

contexte de désengagement de l’Etat, ENGREF, Montpellier, OIEAU, Limoges, France,

38 pp. Url: www.oieau.fr

Samad M. 2002. Impact of irrigation management transfer on the performance of irrigation

systems: A review of selected experiences from Asia. In: Breman D., 2002. Water Policy

Reform: lessons from Asia and Australia. Proceedings of an International workshop held

in Bangkok, Thailand, 8-9 June 2001, pp 161-170

Samad M. 2006. Réformes de la gestion de l’irrigation: l’expérience en Asie et sa pertinence

pour l’Afrique. Séminaire sur le futur de l’irrigation en Méditerranée, Cahors, France, 6-

8 Novembre 2006.

Serfaty-Garzon P. 2003. L’appropriation. In: Dictionnaire critique de l’habitat et du logement.

Ed Armond Colin. Paris, France: pp 27-30

Shah T. 1996. Catalyzing cooperation: Design of self-governing organisations. Sage Ed. Delhi,

Inde, 315 pp.

Shah T, Van Koppen B, Merrey D, De Lange M, Samad M. 2002. Institutional Alternatives in

African Smallholder Irrigation: Lessons from International Experience with Irrigation

Management Transfer. Research Report 60, Water Management International Institute,

Colombo, Sri Lanka. url:

http://www.iwmi.cigar.org/Publications/IWMI_Research_Reports/PDF/pub060/Report60

Page 18 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

19

Tozy M. 2002. Des tribus aux coopératives ethno-lignagères. In Mahdi M. et al, Mutations

sociales et réorganisation des espaces steppiques. 1st edition, Konrad Adenauer

foundation, 19 pp.

Page 19 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960

For Peer Review

20

Table I. Cropping patterns in four WUAs in the Moyen Sebou irrigation scheme in 2007-2008

Sector II Sector III

Loudaya

(ha)

El Kheir

(ha)

El Fath

(ha)

H. Chrifa

(ha)

Cereals 460 633 150 460

Pulse crops 15 20 65 45

Forage crops 40 40 15 25

Watermelons and melons 15 30 38 90

Sugar beet 40 30 - -

Mint 130 3 - -

Orchards (citrus, olives) 25 120 35 320

Total cropped area 725 876 303 940

Total surface area 828 868 366 985

Cropping intensity (%) 88 101 83 95

Page 20 of 21

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/ird

Irrigation and Drainage

123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960