LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

LETTERS TOTHE EDITOR

Right ipsilateral hypersensation in acase of anosognosia for hemiplegia andpersonal neglect with the patient’ssubjective experience

Recently, there have been some reportsregarding hyperkinetic motor behaviourscontralateral to hemiplegia in acute stroke.1 2

These behaviours are probably the reflectionof early plastic changes of brain maps andcircuits after an acute lesion and an activeprocess induced by disinhibition to establishnew compensatory pathways.1 I encountereda peculiar case of a patient with right ipsilat-eral “hypersensation” after a right hemi-spheric infarction in the acute period whoalso presented severe left sensorimotor dis-turbance, hyperkinetic motor behaviours inthe right upper limb, anosognosia for hemi-plegia, and personal neglect. It was possibleto record the patient’s subjective experience

of the acute phase, which was helpful forunderstanding the mechanism of anosogno-sia.

A 76 year old right handed woman wasadmitted to hospital soon after the onset ofleft hemiparesis and hemisensory distur-bance. She had undergone implantation of acardiac pacemaker because of sick sinus syn-drome. On neurological examination, shewas awake and oriented to time and place,but showed inattention and motor impersist-ence. There was no aphasia or apraxia, butmild left hemispatial neglect was detected.Left hemiparesis was noticed (upper limb0/5; lower limb 2/5, and face 3/5). Sensoryloss was complete in all modalities in theupper limb and severe in the face and lowerlimb, being slightly preserved for pain andcoldness. She denied the existence of lefthemiparesis and had completely lost the sen-sation of ownership of her left hemibody.When I asked her the owner of her left handand leg while showing them to her, sheremarked that these belonged to her grand-mother. Brain CT (figure) showed a freshinfarction in the right precentral and post-central gyrus, extensively extending to theright medial aspect of the frontal lobe(supplementary motor area).

From the second hospital day she com-plained that she felt very cold in the right half

of her body and even sometimes felt painbecause the wind from the air conditionerwas too strong. I told her that the airconditioning system worked but it was not setat a low temperature because it was winter.She understood my explanation but she con-tinued to complain of spontaneous, abnormalsensation in her right hemibody. The sensa-tion was most severe in the upper limbfollowed by the face and lower limb, whereasit was not triggered or worsened by any sen-sory stimulation, and objective sensory defi-cits were not present in the right hemibody.She usually wrapped herself tightly in a blan-ket to avoid coldness. She did not complain ofany other delusional or illusional feelings.There were also hyperkinetic motor behav-iours in the right upper limb such as pattingthe head with the right arm, manipulations ofsheets and blanket, and rhythmic fingermovements. The result of a mini mental stateexamination performed on the fourth hospi-tal day was 25/30.

The abnormal sensation persisted foralmost 1 month and gradually subsided,whereas the left hemiparesis and sensory dis-turbance improved. Touch, pain, and tem-perature were intact in the face and lowerlimb, pain and temperature were intact in theupper limb, but there was no improvement inposition and vibration in the entire left hemi-body. In the meantime, she began torecognise the left hemiparesis and regainedthe sensation of ownership of her lefthemibody. The following are her recollectionsfrom the time of onset on the 60th hospitalday.

“One morning, I woke up and found thatthere was a strange hand and foot close to theleft side of my body, as though my deadgrandmother lay aside me. I tried to throwthem oV but they were too heavy to move. Iglanced at them and felt that they lookedflabby and all wrinkled, so I was convincedthat they belonged to my grandmother. I hadno idea that the left side of my body was disa-bled or even ill.

After hospitalisation, I felt very cold in theright half of my body and sometimes felt painbecause of the powerful wind from the airconditioner. I understood that the hospitaldid not use cold air conditioning in winter,but that powerful, cold wind could not havecome from anything other than an air condi-tioner. Anyway, this unpleasant feeling gradu-ally subsided, and at the same time, I realisedthat the disabled left side of my bodybelonged to me and that I had suVered abrain disorder.”

Ghika et al1 described 20 patients withhyperkinetic motor behaviours contralateralto hemiplegia in acute stroke who were foundonly with large infarcts in the territory of theinternal carotid artery, middle cerebral ar-tery, or the anterior cerebral artery and whichcorrelated significantly with the severity ofmotor deficit and the presence of aphasia,neglect, or sensory loss. These characteristicsare similar to those in the present patient.However, “hypersensation” as found in thiscase was not described. Regarding the mech-anism of these behaviours, Ghika et al specu-lated that they represent the clinical expres-sion of early plastic changes of brain mapsand circuits after an acute lesion andprobably an active process induced by disin-hibition to establish new compensatorypathways.1 Such ipsilateral symptoms mightoccur not only in the motor system, but in thesensory system as well.3 In the presentpatient, the degree of right hypersensation

Brain CT showing an infarction in the right precentral and postcentral gyrus extensively extending tothe medial aspect of the frontal lobe.

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;69:274–283274

www.jnnp.com

on July 9, 2022 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.274 on 1 August 2000. D

ownloaded from

was parallel with the degree of the distur-bance of sensory deficits of the homologousleft side, and hypersensation subsided as thesensory disturbance of the left side improved.This suggests that the disinhibition or hyper-excitability to facilitate functional reorganisa-tion may have been the main cause of hyper-sensation in this case.

Lesional extent must also be considered.Studies in animals and patients with strokewith sensorimotor cortical lesion providedseveral insights into the basis for recovery. Inthe cortical region, there are three areaswhere increased activation has been sug-gested: the sensorimotor cortex of the unaf-fected hemisphere, the supplementary motorarea (probably bilateral, ipsilateral muchgreater than contralateral to the lesion), andperi-infarct lesion of aVected hemisphere.4–6

In the present case, the right supplementarymotor area belonged to the lesion and theright sensorimotor cortex was extensivelyinvolved. Acute onset of severe motorand sensory disturbance caused rapiddisinhibition and increased activation whichhad to depend exclusively on the left(unaVected) sensorimotor cortex as theright supplementary motor area and rightperi-infarct area could not be involved inthe reorganisation process. I speculate thatthis provoked hyperkinetic motor behaviouras well as hypersensation in the righthemibody.

In the case of patients who recovered,there have been few reports of subjectiveperceptions in the acute stage of stroke.7

Grotta et al7 reported the subjective experi-ences of 24 patients with nonlacunar ischae-mic stroke who dramatically recovered. Theyfound that most patients did not recollect theseverity of their problem and did notremember important events during the first24 hours regardless of the side of the lesion.However, as most patients (19 of 24) couldclearly recall the exact circumstances involv-ing the onset of their stroke, they speculatedthat their unawareness of deficit was a formof anosognosia rather than a deficit ofmemory or global neurological function.The subjective experience of the patient inthis study corresponds well with thesefindings.

HIDEAKI TEIDepartment of Neurology, Toda Central General

Hospital, 1–19–3 Hon-cho, Toda City 335–0023,Saitama, Japan

Correspondence to: Dr Hideaki [email protected]

1 Ghika J, Bogousslavsky J, van Melle G, et al.Hyperkinetic motor behaviors contralateral tohemiplegia in acute stroke. Eur Neurol1995;35:27–32.

2 Chang GY, Spokoyny E. Hyperkinetic motorbehavior in bihemispheric stroke. Eur Neurol1996;36:247.

3 Kim JS. Delayed-onset ipsilateral sensory symp-toms in patients with central poststorke pain.Eur Neurol 1998;40:201–6.

4 Cramer SC, Nelles G, Benson RR, et al. A func-tional MRI study of subjects recovered fromhemiparetic stroke. Stroke 1997;28:2518–27.

5 Pantano P, Formisano R, Ricci M, et al. Motorrecovery after stroke. morphological and func-tional brain alterations. Brain 1996;119:1849–57.

6 Buchkremer-Ratzmann I, August M, Hage-mann G, et al. Electrophysiological transcorti-cal diaschisis after cortical photothrombosis inrat brain. Stroke 1996;27:1105–11.

7 Grotta J, Bratina P. Subjective experiences of 24patients dramatically recovering from stroke.Stroke 1995;26:1285–8.

Phantom limb sensations after completethoracic transverse myelitis

Phantom phenomena are common complica-tions of limb amputations and may occasion-ally follow traumatic paraplegia and severeinjuries of peripheral nerves. However, theyhave not been previously reported in patientswith non-traumatic paraplegia. The followingcase history describes a patient with trans-verse myelitis resulting in complete paraple-gia who experienced persistent movementsand abnormal positions of her paralysedlower limbs. These findings suggest thatdisruption of the anatomical and functionalintegrity of the spinal cord may be the mostimportant factor in the pathogenesis of phan-tom sensations.

A 61 year old woman presented with severeweakness of both legs, skin sensory loss andparaesthesia of the lower limbs, and boweland bladder symptoms. She was well until 3months earlier when she started to develop atingling sensation and numbness over theouter side of her left leg. These symptomsgradually progressed and by the time she wasadmitted to hospital she had paraesthesia andsensory impairment of the whole of the leftleg and in the distal half of the right leg. Amonth before admission she had becomeunsteady on her feet and developed urinaryfrequency, urgency of micturition, and con-stipation. There was also a rapidly progressiveweakness of both legs, but no other symp-toms.

Four years earlier the patient had had par-aesthesia in both feet. This was thought to bedue to peripheral neuropathy, but the diagno-sis was not confirmed with neurophysiologi-cal tests. The symptoms resolved in a fewweeks. The patient had a partial thyroidec-tomy for a nodular goitre 15 years ago. Therewas no other medical or family history ofnote. She was not taking any medication.

Physical examination confirmed the pres-ence of complete flaccid paraplegia with skinsensory loss of all sensory modalities to thewaist. The knee and ankle jerks were absentand both plantar responses were extensor.She had retention of urine and symptoms,signs, and radiological features of a paralyticileus. The rest of the neurological and generalphysical examination was unremarkable. Afull blood count, urea and electrolytes, andliver and thyroid function tests were withinnormal limits. An MRI of the cervical spineconfirmed the presence of mild degenerativechanges in the cervical spine at the level ofC5-C7. There was no radiological evidenceof an intrinsic or extrinsic cord compressionor demyelination. However, the five distalsegments of the thoracic cord appeared swol-len and there was loss of the normal CSF rimventral and dorsal to the cord on T1 weightedimages. The T2 signal was prolonged andthere was no contrast enhancement of thelesion. The appearances were consideredconsistent with oedema of the thoracic spinalcord. Brain MRI was normal. Visual evokedresponses and brain stem auditory evokedpotentials were within the normal limits.Somatosensory evoked potentials of the pos-terior tibial nerve could not be obtainedbecause the patient developed severe myo-clonic jerks of the entire leg at very lowstimulus intensities. Her CFS protein con-centration was 0.88 g/dl. No oligoclonalbands were detected on CSF protein electro-phoresis. There were 2 lymphocytes/mm3 andfour polymorphs/mm3. There was no bacte-rial growth on CFS culture.

Shortly after admission the patient startedto experience phantom sensations in herlower limbs. At times she thought that herlegs were crossed and on other occasions shefelt that that she was standing on tiptoes.These symptoms were persistent and ap-peared to be spontaneous. Careful question-ing did not disclose any specific stimuli. Theirintensity remained unchanged until thepatient was started on 200 mg carbamazepinethree times a day. With this treatment thephantom sensations became less frequent andthe images were less intense but they did notresolve completely. The paralytic ileus re-solved with conservative treatment. However,the patient’s neurological impairments re-mained unchanged until she was dischargedfrom hospital 6 months later.

Non-painful phantom phenomena are con-tinuous or intermittent sensations emanatingfrom an amputated or deaVerented part ofthe body. The missing or denervated partmay be perceived in its premorbid shape, size,and other physical characteristics1 or in a dis-torted form.2 Patients often report normalfunctions associated with the absent organ—for example, penile erection, ejaculation, andorgasm after removal of the genitalia3 or vol-untary or involuntary movements of anamputated limb. Often, sensations such astouch, pressure, and cold are experienced inthe phantom organ. Phantom sensationsoften occur after limb amputations1 and havealso been reported in about 15% of patientsafter a mastectomy.4 Sometimes they may fol-low spinal cord injury.5 However, their occur-rence after transverse myelitis has not beenpreviously reported.

Understanding the pathogenesis of phan-tom sensations is important for developingthe appropriate treatment strategies. How-ever, the mechanisms that underlie thesephenomena are not fully understood atpresent. It has been suggested that they maybe a manifestation of a psychological disorderor due to organic neurophysiological abnor-malities.

Psychological factors such as denial or grieffor the lost body part have been suggested asthe cause of the postamputation phantomphenomena. However, this explanation is notsupported by the currently available evi-dence. For example, the occurrence of phan-tom phenomena does not correlate with poorpsychological adjustment or with the inci-dence of depressive symptoms in thesepatients.6 Another hypothesis is that damagedperipheral somatosensory receptors firespontaneously and give rise to the painful orabnormal experiences.7 However, phantomsensations have been reported by patientsafter spinal anaesthesia in the absence ofdamage to the peripheral nervous system.1 Atpresent the neuromatrix theory8 oVers themost plausible explanation for phantom sen-sations and pain.

According to this theory the symptomsassociated with the phantom phenomenaoriginate from genetically predeterminedsensory images (or sensory engrams) that arestored in the cerebral cortex. It was postu-lated that the sensory images are triggeredwhen neural impulses from the periphery areblocked. The patient reported here had com-plete “functional” transection of the spinalcord. The occurrence of phantom sensationsin this patient was therefore independent ofthe neural input from the peripheral nervoussystem. This case provides further evidencethat phantom phenomena are due to a centralneurophysiological mechanism, probably

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;69:274–283 275

www.jnnp.com

on July 9, 2022 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.274 on 1 August 2000. D

ownloaded from

triggered by impulses arising spontaneouslyfrom damaged spinal cord neurons. This is inaccord with a previous report of structuraland functional changes in the spinal cord inthe acute stage after deaVerentation.9

Ramachandran and Hirstein10 reviewed thestudies of the topographical reorganisation ofthe cerebral cortex after limb amputationsand concluded that the mechanism ofphantom experiences is “remapping” of spe-cific brain areas. The present study did notconsider this question. However, the diversityof the illusionary experiences of movementreported by our patient suggests a morediVuse cortical reorganisation. This is morein keeping with the neuromatrix theory,9 andthe presence of “diVuse neural matrix”.

The occurrence of phantom limb phenom-ena in patients with non-traumatic CNSlesions had also been previously described ina few patients with stroke. Halligan et al11 car-ried out a detailed study of a 65 year old manwith severe left sided weakness, sensory loss,and hemianopia who, for several weeks, con-sistently reported a phantom (or supernu-merary) third limb. Like our patient, he hadgood insight into his neurological deficits andhis behaviour was completely rational, sug-gesting that the phantom experience was nota delusional belief but a direct result oforganic brain damage.

A M O BAKHEITBeauchamp Centre, Mount Gould Hospital,

Plymouth Pl4 7QD, UK

1 Ribbers G, Mulder T, Rijken R. The phantomphenomenon: a critical review. InternationalJournal of Rehabilitation Research 1989;12:175–86.

2 Jensen TA, Krebs B, Nielsen J, et al. Non-painful phantom limb phenomena inamputees: incidence, clinical characteristicsand temporal course. Acta Neurol Scand 1984;70:407–14.

3 Heusner AP. Phantom genitalia. Transactions ofthe American Neurological Association 1950;75:128–31.

4 Kroner K, Knudsen UB, Lundby L, et al. Long-term phantom breast syndrome after mastec-tomy. Clin J Pain 1992;8:346–50.

5 Burke DC, Woodward JM. Phantom movementand phantom feeling in complete paraplegicpatients. Handbook of Clinical Neurology 1976;26:489–99.

6 Sherman RA, Sherman CJ, Bruno GM. Psycho-logical factors influencing chronic phantomlimb pain: an analysis of the literature. Pain1987;28:285–95.

7 Calvin WH, Devor M, Howe J. Can neuralgiasarise from minor demyelinization? spontaneousfiring, mechanosensitivity and after-dischargefrom conducting axons. Exp Neurol 1982;75:755–63.

8 Melzack R. The gait control theory 25 yearslater: new perspectives on phantom limb pain.In: Bond MR, Charlton JE, Woolf CJ, et al, eds.Proceedings of the VI th World Congress on Pain.Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1991:9–21.

9 Wall PD. On the origin of pain associated withamputation. In: Siegfried J, Zimmermann M,eds. Phantom and stump pain. Berlin: Springer,1981.

10 Ramachandran VS, Hirstein W. The perceptionof phantom limbs. The DO Hebb Lecture.Brain 1988;121:1603–30.

11 Halligan PW, Marshall JC, Wade DT. Threearms: a case study of supernumerary phantomlimb after right hemisphere stroke. J NeurolNeurosurg Psychiatry 1993;55:159–66.

Vestibular evoked myogenic potentialsin multiple sclerosis

Myogenic potentials generated by a clickevoked vestibulospinal reflex can be easilyrecorded from the tonically contractingipsilateral sternocleidomastoid muscle(SCM). These “vestibular evoked myogenicpotentials” (VEMPs) are abolished by selec-tive vestibular nerve section1 as well as by cer-

tain peripheral vestibular diseases.2–4 Clicksensitive primary vestibular neurons arisefrom the saccular macula in the guinea pig5

and electrical stimulation of these neurons inthe cat evokes inhibitary postsynaptic poten-tials in ipsilateral SCM motor neurons whichare abolished by transection of the medialvestibulospinal tract.6 These clinical and neu-rophysiological data suggest that VEMPs aremediated by a pathway consisting of the sac-cular macula, its primary neurons, vestibulos-pinal neurons from the lateral vestibularnucleus, the medial vestibulospinal tract, andfinally motor neurons of the ipsilateral SCM.Therefore a lesion anywhere in this pathwaycould result in abnormal VEMPs. We studiedVEMPs in three patients with definite multi-ple sclerosis7 to search for lesions in the vesti-bulospinal pathways.

Patient 1, a woman aged 30, and patient 2,a man aged 32, both showed dysarthria, cer-ebellar ataxia, bilateral internuclear ophthal-moplegia, and a spastic tetraparesis. Patient3, a woman aged 36, showed cerebellar ataxiaand a spastic tetraparesis only. Apart fromVEMPs, all patients underwent auditoryevoked potential (AEP) testing as well asMRI.

Our recording methods have been de-scribed previously.2 3 Briefly, surface EMGactivity was recorded in the supine patientfrom symmetric sites over the upper half ofeach SCM with a reference electrode on the

lateral end of the upper sternum. During therecording, the patients were instructed torotate their heads to the opposite side to thestimulated ear to activate the SCM. Rarefac-tion clicks (0.1 ms, 95 dB normal hearinglevel) were presented through a headphone.The responses to 100 stimuli were averagedtwice. Our normal control values have beenreported previously.2 3 Briefly, all normal sub-jects show a biphasic response (p13-n23)from the ipsilateral SCM. The mean (SD) ofthe positive peak (p13)=11.4 (0.8) ms; themean (SD) of the negative peak (n23)=20.8(2.3) ms. We defined the mean+2 SD as theupper limit of the normal range—that is,p13=13 ms and n23=25.4 ms.

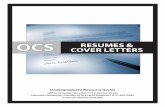

All of the six sides in three patients showedbiphasic responses (p13-n23) with signifi-cantly prolonged latencies. Patient 1 showedprolonged p13 and n23 on both sides (rightp13=16.7, n23=26.9 ms; left p13=19.8,n23=29.2 ms, figure A). Patients 2 and 3showed bilaterally prolonged p13 (rightp13=15.3, left p13=16.5 ms (patient 2), andright p13=15.0, left p13=18.5 ms (patient 3).In patient 1 the latency of the left p13 (19.8ms) was longer than that of the right p13(16.7ms); in this patient the interpeak latencybetween waves I and V of the AEP wassignificantly prolonged only on the right(right=5.14 ms, left=4.30 ms, figure B).

T2 weighted MRI of patient 1 showed highintensity areas in the tegmentum of the pons

Time (ms)

C

A B

p13

50 µV

n23

p13

n23

R

L

0 40302010

Time (ms)

50 µV

V

VI

I III

R

L

0 8642

(A) VEMPs, (B) AEPs, and (C) MRI from patient 1. VEMPs are significantly bilaterally,asymmetrically prolonged on both sides. On the left: p13=19.8 ms, n23=29.2 ms; on the right:p13=16.7 ms, n23=26.9 ms. L=responses from the left SCM to the left ear stimulation; R=responsesfrom the right SCM to the right ear stimulation. AEPs on the left were normal, while on the rightwave V was delayed to 6.5 msec (normal < 5.9 ms) and the I-V interpeak latency was prolonged to5.1 ms (normal <4.4 ms). T2 weighted MRI shows high intensity lesions in the pontine tegmentuminvolving the vestibular nuclei and vestibulospinal tracts bilaterally.

276 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;69:274–283

www.jnnp.com

on July 9, 2022 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.274 on 1 August 2000. D

ownloaded from

on both sides involving the vestibulospinaltracts bilaterally (figure C). Patients 2 and 3also had high intensity areas in the sameareas. Apart from lesions in this area, allshowed high signal intensity areas in the cer-ebral white matter.

This preliminary study shows that latenciesof a vestibulospinal reflex can be prolonged inmultiple sclerosis. As in these three patientsthe VEMPs were remarkably delayed ratherthan simply abolished as occurs in patientswith peripheral vestibular lesions,2–4 theVEMP delay could be attributed to demyeli-nation either of primary aVerent axons at theroot entry zone or secondary vestibulospinaltract axons rather than to lesions involvingvestibular nucleus neurons. The MRI find-ings in these patients were not inconsistentwith this proposition. Measurement ofVEMPs could be a useful clinical test toevaluate function of the vestibulospinal path-way and for detecting subclinical vestibulos-pinal lesions in suspected multiple sclerosis.

This study was supported by a Research Grant fromthe Intractable Diseases Fund (Vestibular Disor-ders) of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Japan(1999).

KEN SHIMIZUTOSHIHISA MUROFUSHI

Neuro-otology Clinic, Department of Otolaryngology,Faculty of Medicine, University of Tokyo,

7–3–1 Hongo, Tokyo 113–8655, Japan

MASAKI SAKURAIDepartment of Physiology, Teikyo University School of

Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

MICHAEL HALMAGYINeurology Department, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital,

Sydney, Australia

Correspondence to: Dr Toshihisa [email protected]

1 Colebatch JG, Halmagyi GM, Skuse NF.Myogenic potentials generated by a click-evoked vestibulocollic reflex. J Neurol NeurosurgPsychiatry 1994;57:190–7.

2 Murofushi T, Matsuzaki M, Mizuno M. Ves-tibular evoked myogenic potentials in patientswith acoustic neuromas. Arch Otolaryngol HeadNeck Surg 1998;124:509–12.

3 Murofushi T, Halmagyi GM, Yavor RA, et al.Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in ves-tibular neurolabyrinthitis; an indicator of infe-rior vestibular nerve involvement? ArchOtolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;122:845–8.

4 Heide G, Freitag S, Wollenberg I, et al. Clickevoked myogenic potentials in the diVerentialdiagnosis of acute vertigo. J Neurol NeurosurgPsychiatry 1999;66:787–790.

5 Murofushi T, Curthoys IS. Physiological andanatomical study of click-sensitive primary ves-tibular aVerents in the guinea pig. ActaOtolaryngol (Stockh) 1997;117:66–72.

6 Kushiro K, Zakir M, Ogawa Y, et al. Saccularand utricular inputs to sternocleidomastoidmotoneurons of decerebrate cat. Exp Brain Res1999;126:410–16.

7 Poser CM, Paty DW, Scheinberg L, et al. Newdiagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guide-lines for research protocols. Ann Neurol 1983;13:227–31.

Sensory ataxia as the initial clinicalsymptom in X-linked recessivebulbospinal neuronopathy

X-Linked recessive bulbospinal neuronopa-thy (X-BSNP) has previously been describedas a disease in which the first clinicalsymptoms which occur concern the motorsystem. A weakness of the shoulder and pelvicgirdle muscles as well as cramps and musclepain in the proximal limbs are normallyfound in the early stages.1–3 The onset ofX-BSNP generally ranges between the ages of25 and 50 years; the disorder then shows aslow but continuous progression of

symptoms.1 3 An involvement of facial andbulbar musculature with fasciculations andatrophy of these muscles and, therefore, oftendysarthria and dysphagia, are common symp-toms of an advanced stage.1 3 Nevertheless,life expectancy does not seem to be consider-ably reduced.1 Sensory impairment wasreported to be minimal or non-existent.1–3

Pathoanatomical studies showed that adegeneration of both the lower motor andprimary sensory neurons represent the un-derlying pathological process for the clinicalsymptoms.4 The pathogenetic link betweenthe abnormally expanded CAG trinucleotiderepeat in the first exon of the androgenreceptor gene which is found in aVectedpatients and the depletion of the anteriorhorn cells and the primary sensory neuronswith consecutive axonal degeneration of thedorsal root fibres has not been establishedyet.4 5 Although central and peripheral sen-sory conduction has been shown to be highlyabnormal with absent or markedly prolongedsensory action potentials, most of the timethe clinical findings of only a little sensoryimpairment do not correspond well to thiselectrophysiological constellation.1 3 We re-port sensory ataxia as the initial clinicalsymptom in a patient with X-BSNP.

A 63 year old retired journalist felt like“walking on pillows” for the first time whenhe was 45 years old. During the subsequentyears the distally accentuated and symmetricloss of sensibility for touch, temperature,pain, position, and vibration was progressivein the legs—and later—also in the arms. Atthe age of 48 he noticed fasciculations of thefacial muscles and a slow development of apainless, bilateral weakness of the proximalmuscles of the lower and upper limbs. Norelated disease was found in his father’s fam-ily; nothing is known about the maternal sideof his family history.

The clinical examination of the patientshowed a severe sensory gait ataxia as well as adyspraxia of his hands. Other symptoms were atremor of the hands and occasional spasms ofthe oral and pharyngeal musculature. Thefunctions of other cranial nerves were normal.Spontaneous fasciculations of the buccal mus-cles and less often of the proximal and distallimb musculature were seen. Deep tendonreflexes could generally not be detected andthere were no pathological reflexes. A proxi-mally accentuated weakness and amyotrophyof the legs and arms as well as a distally accen-tuated hypaesthesia for all qualities was found.There were no cognitive deficits, cerebellarataxia, or gynaecomastia.

Laboratory results were not abnormal(including plasma testosterone, follicle stimu-lating hormone, luteinising hormone, andglucose tolerance) except for a raised creatinekinase (354 U/l). The CSF examination alsoshowed no abnormalities. Motor nerve con-duction velocities were only slightly reducedwhereas sensory action potentials were ab-sent. Electromyography showed the typicalfeatures of chronic denervation in the proxi-mal muscles of the lower and upper limbs aswell as in the tongue. Motor evoked poten-tials showed normal central conduction timesbut partially prolonged latencies with stimu-lation of the cervical and lumbal roots. Withtibial and median nerve stimulation no soma-tosensory evoked potentials were foundneither at the cervical or lumbal nor at thecortical recording sites. Brain MRI wasnormal. The genetic analysis showed 42 CAGtrinucleotide repeats within the androgenreceptor gene (normal length 11–34 repeats),

which is a valuable criterion in the diagnosisof X-BSNP.5

The example of our patient shows that theelectrophysiological findings of the sensorysystem may correspond well to the clinicalsyndrome in X-BSNP. It is not clear whypatients with X-BSNP in most cases do notshow significant sensory impairment al-though substantial loss of the primarysensory neuron has been proved. We hopethat findings as in this case report may be anincentive for us to work for a betterunderstanding of the problem as to why aspecific neuronal degeneration can lead to aless specific pattern of clinical symptoms.

ANSGAR BUECKINGROBERT PFISTER

Department of Neurology, Zentralklinikum Augsburg,Stenglinstrasse 2, D-86156 Augsburg, Germany

Correspondence to: Dr Robert Pfister

1 Harding AE, Thomas PK, Baraitser M, et al.X-linked recessive bulbospinal neuronopathy: areport of 10 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry1982;45:1012–19.

2 Kennedy WR, Alter M, Sung JH. Progressiveproximal spinal and bulbar muscular atrophyof late onset. A sex-linked recessive trait.Neurology (Minneapolis) 1968;18:671–80.

3 Wilde J, Moss T, Thrush D. X-linked bulbo-spinal neuronopathy: a family study of threepatients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1987;50:279–84.

4 Sobue G, Hashizume Y, Mukai E, et al. X-linkedrecessive bulbospinal neuronopathy. A clinico-pathological study. Brain 1989;112:209–32.

5 La Spada AR, Paulson HL, Fischbeck KH. Tri-nucleotide repeat expansion in neurologicaldisease. Ann Neurol 1994;36:814–22.

Neuroleptic malignant syndromewithout fever: a report of three cases

Although fever is considered to be a cardinalfeature of neuroleptic malignant syndrome,we report on three patients who were afebrilebut had all the other features of the neurolep-tic malignant syndrome. This paper high-lights the need to suspect neuroleptic malig-nant syndrome and immediately initiateinvestigation and appropriate management inany patient who develops rigidity and cloud-ing of consciousness while receiving antipsy-chotic medication, thus averting potentiallylethal sequelae such as death.

The neuroleptic malignant syndrome(NMS) is an uncommon but potentially fatalidiosyncratic reaction characterised by thedevelopment of altered consciousness, hyper-thermia, autonomic dysfunction, and muscu-lar rigidity on exposure to neuroleptic (andprobably other psychotrophic) medications.1 2

According to the DSM IV criteria,3 promi-nence has been given to signs of increase intemperature (>39o C) and muscular rigidity.These must be accompanied by two or moreof: diaphoresis, dysphagia, tremor, inconti-nence, altered consciousness, tachycardia,blood pressure changes, leucocytosis andraised creatine kinase concentrations. Someresearchers have also advocated that a pyrexiain excess of 380C or 390C is necessary for thediagnosis of NMS.4–5 However, on reviewingthe literature since 1965, we found three pre-vious case reports highly suggestive of NMSoccurring without fever.6–8 We report threepatients who had all the major features ofNMS but were afebrile during the entirecourse of their illness. These cases were seenwithin a 1 year period from July 1998 to July1999.

A 52 year old man who was on treatmentfor postpsychotic depression presented afteran act of deliberate self poisoning with a

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;69:274–283 277

www.jnnp.com

on July 9, 2022 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.274 on 1 August 2000. D

ownloaded from

rodenticide. As he became acutely disturbedand violent in the ward he was given severalinjections of intramuscular haloperidol, andhe received no further antipsychotic medi-cation. On the next day he developed severerigidity associated with profuse sweating andmarked autonomic instability. His heart ratewas 120 beats per minute and was irregular.His blood pressure showed wide fluctuationsand there was urinary incontinence. He thenbecame confused and went into a state ofsemiconsciousness. There was no increase inbody temperature. The creatine phosphoki-nase concentration was 1575 IU on the 2ndday and 6771 IU on the 4th day of his illness,and the white cell count was 17 000/mm3

(neutrophils 60%, leucocytes 30%, eosi-nophils 6%, macrophages 4%). As the patientdid not have any increase in body tempera-ture there was doubt as to the diagnosis. Instandard medical texts fever was recorded asa necessary finding in NMS. However, amedline search contained reports of threepatients with NMS in the absence of fever.The patient was immediately startedon bromocriptine at a dose of 2.5 mg threetimes a day. By the 5th day of treatment hiscondition improved with the autonomicdisturbances disappearing and the rigiditysubsiding. His creatine phosphokinase con-centration became normal after 5 days oftreatment.

A 20 year old man was started on 10 mgtrifluperazine twice a day for schizophreniawith catatonic features and discharged afterbeing given a depot injection of 40 mgflupenthixol intramuscularly. Five days laterhe was readmitted due to progressivelyincreasing stiVness of his body, diYculty inswallowing, drowsiness, and incontinence ofurine. On examination he was very rigid andsemiconscious, but opened his eyes to deeppain, and had severe diaphoresis whichdrenched the bed clothes. However, he hadno rise in body temperature. His heart ratewas 130 beats per minute, respiratory rate 28per minute, and his blood pressure showedmarked fluctuations. The creatine phos-phokinase assay done on the 2nd day gave2109 IU/l and the white blood cell countwas 12 400/mm3 (neutrophils 93%). Otherinvestigations including analysis of hisCSF was normal. We made a tentative diag-nosis of NMS, even though the patient didnot have fever, as we had treated a patientwith NMS presenting without fever previ-ously. The neuroleptic medication wasstopped and he was started on 2.5 mgbromocriptine three times a day. As theresponse was poor the dose was graduallyincreased to 10 mg three times a day. Hemade a relatively slow recovery and came outof the comatose state after 1 week oftreatment and autonomic disturbances andrigidity disappeared after 10 days of treat-ment. On discharge from hospital on the14th day after starting bromocriptine hiscreatine phosphokinase was 230 IU/l.

An 18 year old boy with schizophreniawas on long term antipsychotic drugs.He was admitted with increasing stiVness ofthe body, drowsiness, and urinary inconti-nence. On examination he was rigid, had atachycardia (pulse rate 130 beats perminute) alternating with a bradycardia(pulse rate 50 beats per minute) and hisblood pressure showed wide fluctuations.There was no increase in body temperatureat admission or during the course of hisillness. The creatine phosphokinase concen-tration was 1450 IU/l on the 2nd day of his

illness and the white cell count was 15000/mm3 (neutrophils 85%). Antipsychoticmedication was stopped and he was startedon 2.5 mg bromocriptine three times a day.He made a complete recovery, with the auto-nomic disturbances and rigidity subsidingwithin 5 days of treatment. One week laterhis creatine phosphokinase was 100 IU/l.

The neuroleptic malignant syndrome usu-ally occurs with the use of therapeutic dosesof neuroleptic drugs and commonly developsduring the initial phases of treatment, whenthe drug dose is being stepped up, or when asecond drug is introduced. However, it canoccur at any time during long term neurolep-tic treatment with factors such as exhaustion,agitation, and dehydration acting as triggers.1

The above point is noteworthy especiallygiven the possibility of the occurrence of avariant and uncommon clinical picture suchas that described in our paper. There are nospecific laboratory findings, but neutrophilleucocytosis and raised creatine phosphoki-nase concentrations lend weight to thediagnosis.9

These three cases illustrate the point thatNMS can occur without fever. Our patientshad all the features of NMS apart from feverand the response to bromocriptine can betaken as strong evidence that the diagnosiswas accurate. Being familiar with this fact andother diVerent ways in which this syndromecan present plus a high degree of suspicionare important in making an early andaccurate diagnosis of NMS. In fact, theappearance of muscle rigidity and clouding ofconsciousness in any patient receiving antip-sychotic medication should prompt cliniciansto suspect NMS and immediately initiateappropriate investigation and management. Afailure to do so may lead to delay or failure towithdraw neuroleptic medication, and thuslead to potentially irreversible sequelae andeven death. The first case also illustrates thatat times of doubt about the diagnosis of anuncommon presentation of a well describedillness, reference to the literature including animmediate Medline search could help inmaking decisions about appropriate patientmanagement.

D T S PEIRISK A L A KURUPPUARACHCHI

L P WEERASENADepartment of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine,

University of Kelaniya, PO Box 6, Tallagolla Road,Ragama, Sri Lanka

S L SENEVIRATNEY T TILAKARATNA

H J DE SILVADepartment of Medicine

B WIJESIRIWARDENAColombo North Teaching Hospital, Ragama, Sri

Lanka

Correspondence to: Dr D T S [email protected]

1 Bristow MF, Kohen D. Neuroleoptic malignantsyndrome. Br J Hosp Med 1996;55:517–20.

2 Haddad PM. Neuroleptic malignant syndromemay be caused by other drugs. BMJ 1994;308:200–1.

3 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnosticand statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed.Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Associ-ation, 1994.

4 CaroV SN, Mann SC. Neuroleptic malignantsyndrome. Med Clin North Am 1993;77:185–202.

5 Adityanjee, Singh S, Singh G, et al. Spectrumconcept of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. BrJ Psychiatry 1988;153:107–11.

6 Sullivan CF. A possible variant of the neurolep-tic malignant syndrome. Br J Psychiatry 1987;151:689–90.

7 Dalkin T, Lee AS. Carbamazepine and formefruste neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Br JPsychiatry 1990;157:437–8.

8 Hynes AF, Vickar EL. Case study: neurolepticmalignant syndrome without pyrexia. J AmAcad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996;35:959–62.

9 Schrader GD. The neuroleptic malignant syn-drome. Med J Aust 1991;154:301–2.

Acute psychosis and EEG normalisationafter vagus nerve stimulation

The acute appearance of psychosis onachievement of seizure control and normali-sation of a previously abnormal EEG has longbeen recognised as a clinical entity termed“forced normalisation”.1 Focal and general-ised epilepsies are both implicated.1 Most ofthe old and new antiepileptic drugs have beenimplicated in the emergence of psychosis withEEG normalisation.1 2

Chronic vagus nerve stimulation has beenproposed as an eVective and safe treatment ofmedically intractable epilepsy, although themechanism of action and the specific indica-tions of this treatment remain unknown. SideeVects are limited and no serious or lifethreatening damage has been reported.3

The case of a patient with medicallyintractable epilepsy who developed aschizophrenia-like psychosis when control ofseizures and scalp EEG normalisation wereachieved through vagus nerve stimulation ispresented.

A 35 year old man had had intractable leftfrontotemporal epileptic seizures since theage of 10 years. He is right handed and leftlanguage dominant. Up to the age of 25 yearshe was almost free of seizures under treat-ment with carbamazepine and phenobarbital.After that the number of seizures graduallyincreased and secondary generalised seizuresappeared. Phenyntoin, carbamazepine, valp-roic acid, phenobarbital, vigabatrin, lamot-rigine, and clonazepam were used in diVerentcombinations without an acceptable seizurecontrol. Repeated EEG recordings during thepast few years were abnormal with prominentslow activity, long intervals of voltage attenu-ation, and common bursts of high voltagespike wave complexes recorded mainly at theleft frontotemporal area. A high resolutionMRI was normal.

In October 1997, a vagus nerve stimulatorwas implanted because of poor seizurecontrol. During a 12 week baseline precedingthe implantation, more than 40 complex par-tial and one to two secondary generalised sei-zures every 4 weeks were noted. The patientalso experienced bursts of uncounted shortlasting complex partial seizures on a few daysevery month. At the time of implantationmedical treatment consisted of 500 mgtopiramate and 475 mg lamotrigine daily.The patient had been on this daily dose for 6months before implantation.

The stimulator output was progressivelyincreased over 1 month from implantation.The final parameters were: pulse rate 30 Hz,5 minutes oV, 30 seconds on, 1.5 mA inten-sity, and 500 ms pulse width. During thesubsequent 2 months, seizure frequency dra-matically reduced even though medicationremained unchanged. For the last 2 weeks ofthe second month he had noted only oneshort lasting complex partial seizure; at thesame time the family had noted a change inthe patient’s behaviour. Psychiatric evalua-tion disclosed a schizophrenia-like syndromewith auditory hallucinations, delusions ofpersecution, thought broadcasting, psycho-motor agitation, and complete lack of insight.

278 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;69:274–283

www.jnnp.com

on July 9, 2022 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.274 on 1 August 2000. D

ownloaded from

An EEG recording showed a low voltage nor-mal background activity coexisting with lowvoltage fast rhythms without any paroxysmalactivity.

The patient was admitted to hospital andantipsychotic medication with 15 mg/dayhaloperidol was added to his antiepilepticdrug treatment. Biperiden (4 mg/day) wasadded to reduce extrapyramidal side eVects.

After 4 weeks of treatment the patient’ssymptomatology was reduced to a degree of50% from the initiation of the treatment andthe patient left the hospital. In the follow up,the haloperidol dose was reduced graduallywithin 4 months to a dose of 5 mg/day(maintenance therapy).

The psychotic reaction in our patient wasnot an ictal symptom because it occurred in astate of clear consciousness with a normalEEG in a period that was seizure free.

Regarding the involvement of drugs as acausative factor for psychosis, all establishedantiepileptic drugs have been shown toprecipitate psychiatric symptoms. Treatmentof the patient consisted of lamotrigine andtopiramate, drugs that have been implicatedin the provocation of psychotic symptoms4

but as he had been already under the samemedication for the past 10 months before thevagus nerve stimulator was implanted, theprecipitation of psychosis does not seem to bepharmaceutical. Further support to the abovehypothesis is provided by the fact that thepsychotic symptoms appeared just whenseizure control was achieved by vagus nervestimulation.

The comorbidity of psychosis and epilepsyin our patient could not be excluded.However, the absence of a history of psycho-sis as well as the lack of a positive family his-tory for any major psychiatric disorder doesnot render support to the above possibility.

The reduction of seizure frequency andEEG normalisation as a cause of psychotic-like reactions in epileptic patients have beenproposed by many authors.1 In our patientseizure cessation had a temporal sequencewith development of psychosis and EEG nor-malisation.

The term “forced or paradoxical normali-sation” is more or less a theoretical conceptwith an unknown biochemical mechanism.Neurotransmitter hypotheses, kindling theeVect of recurrent seizures on the limbic sys-tem that facilitate the psychosis have beenproposed as the possible underlyingmechanism.1

Our case may diVerentiate the proposalsfor the underling mechanism of psychosisand EEG normalisation in epileptic patients.We suggest that seizure cessation inan epileptic brain seems to play a majorpart in the development of psychotic symp-toms, independent of antiepileptic medica-tions.

As far as we know, this is the first report ofa psychotic reaction with a forced normalisa-tion induced by vagus nerve stimulation.Recent studies shows that c-fos expression isincreased during vagus nerve action in theposterior cortical amygdala, cingulate retros-plenial cortex, and other areas.5 Extensivebrain areas seems to be involved and therebya possible influence on behavioural mecha-nisms could not be excluded.

S D GATZONISE STAMBOULIS

A SIAFAKASDepartment of Neurology, Eginition Hospital,

Athens Medical School, 72 vas Sofias Avenue,Athens 11528, Greece

E ANGELOPOULOSDepartment of Psychiatry

N GEORGACULIASE SIGOUNAS

Neurosurgery Clinic, Evangelismos Hospital, Greece

A JEKINSDepartment of Neurosurgery,

Newcastle General Hospital, UK

Correspondence to: Dr Stylianos D [email protected]

1 Pakalnis A, Drake ME, Kuruvilla J, et al. Forcednormalization. Ann Neurol 1988;44:289–92.

2 Sander JWAS, Hart YM, Trimble MR, et al.Vigabatrin and psychosis. J Neurol NeurosurPsychiatry 1991;54:435–9.

3 Fisher RS, Krauss GL, Ramsay E, et al. Assess-ment of vagus nerve stimulation for epilepsy.Neurology 1997;49:293–7.

4 Crawford P. An audit of topiramate use in ageneral neurologic clinic. Seizure 1998;7:207–11.

5 Naritoku DK, Torry WJ, Helfert RH. Regionalinduction of fos immunoreactivity in the brainby anticonvulsant stimulation of the vagusnerve. Epilepsy Res 1995;22:53–62.

A randomised double blind trial versusplacebo does not confirm the benefit ofá-interferon in polyneuropathyassociated with monoclonal IgM

The peripheral neuropathy associated with amonoclonal anti-MAG IgM is considered asa specific entity.1–3 The clinical features arediVerent from those seen with monoclonalIgG or IgA, with sensory loss and ataxia moreoften found. A causal link between themonoclonal IgM and the development ofneuropathy is suggested by the antibodyactivity of the IgM to nerve polypeptides orglycolipids,3–7 the detection of IgM depositson the myelin sheaths of patients’ nervebiopsies,2 8 9 and the induction of the neu-ropathological process through the transfer ofthe anti-MAG IgM in animal models.10 11 Thelow rate (30%) of clinical improvement withchlorambucil (CLB) or plasma exchange insuch patients justifies the search for newtherapeutic strategies.12 13

In a previous phase II open clinical trialrandomly comparing intravenous immu-noglobulins (IVIg) and á-interferon (á-IFN), we concluded that IVIg was ineYcientbut that á-IFN produced a significantclinical improvement in eight out of 10patients at 6 months and in seven of themat 12 months.14 The mechanism of actionof á-IFN was unclear as the concentrationof the monoclonal IgM as well as the titreof anti-MAG antibody were unchanged. Asthe improvement with á-IFN was mainlyrelated to an improvement of sensory symp-toms, most of them being subjective, wedesigned a multicentre, prospective, ran-domised double blind study of á-IFN versusplacebo.

Patients included in this study had to fulfillall the following criteria: (1) have had stableor progressive neuropathy for at least 3months; (2) show the presence of a serummonoclonal IgM with anti-MAG antibodyactivity as detected by immunoblotting ondelipidated human myelin6; (3) have a clinicalneuropathy disability score (CNDS) above10 (see below); (4) have no other causes ofperipheral neuropathy, especially diabetes,alcohol, cryoglobulinaemia, and amyloidosis;(5) not have had treatment in the past 3months.

The study was designed to be a multicen-tre, prospective, randomised, double blindclinical trial comparing á-IFN and placebo.

The protocol was approved by the HôpitalPitiè-Salpétriëre ethics committee. After pro-viding written informed consent, patientsunderwent stratified randomisation accord-ing to the existence of a previous treatment,through a blind telephone assignment proce-dure. The patients were randomly allocatedto receive either á-IFN or placebo.á-Interferon (Roferon, Roche) was given at4.5 MU three times a week for 6 months.Placebo consisted of sodium chloride, benzylalcohol, polysorbate 80, and glacial aceticacid diluted in sterile water. The reconsti-tuted vials of á-IFN or placebo were deliveredby the pharmacy of each centre and appearedidentical.

The clinical neuropathy disability score(CNDS) was the same as that used in ourpreliminary study.14 The score in a normalsubject was 0. It could range from 0 to 93,summing 0 to 28 points for the motorcomponent, 0 to 12 for the reflexes compo-nent, and 0 to 53 points for the sensory com-ponent. In addition, the patient was asked toappreciate the change in five symptoms: par-aesthesia, dysaesthesia, ground perception,striction, and walking in major improvement(−2), slight improvement (−1), stability (0),slight worsening (+1), major worsening (+2).This score termed “subjective assessment”ranged from −10 to +10 and was added to theprevious one except for the initial examina-tion. Follow up examinations were performedby the same physician for each patient every 3months.

The main end point was defined by theabsolute diVerence in the CNDS frombaseline to the 6th month (or to the time ofwithdrawal of treatment if the treatment wasstopped before the 6th month). The numberof patients in each group who experienced animprovement of the CNDS of more than20% defined a secondary end point.

Estimation of sample size was based on themain criterion, using a two sample t test. Wewere expecting a diVerence of CNDS be-tween treatment groups of 10 with SD 10,using the estimates derived from a previoustrial.14 Specifying a type I error of 0.05, apower of 0.90, a two sided test required 22patients per group. Given the low incidenceof this disease, the protocol planned oneinterim analysis to minimise the sample size,using repeated significance tests with a nomi-nal significance level of 0.029.

Statistical analysis was made on an inten-tion to treat basis. Comparisons used aKruskal and Wallis test for continuousvariables, Fisher’s exact test for binaryvariables. Relations between continuous vari-ables were studied by the Spearman coef-ficient. All tests were two sided. The SAS(SAS Institute, Cary, NC) software packagewas used.

After the inclusion of 24 patients, Rochelaboratory decided not to provide placeboany more because of trade diYculties. Thepromotor of the study (AP-HP) decided tocarry out the interim analysis which led tostopping the accrual of patients because ofthe absence of benefit of á-IFN versusplacebo.

Twenty four patients were enrolled fromfive hospitals, 12 being assigned to á-IFN and12 to placebo. Eleven patients (five in theá-IFN group, six in the placebo group) hadbeen previously treated with CLB withoutimprovement of the neuropathy. In 10 ofthem, plasma exchanges had also beenunsucessful. The mean duration (SD) of theperipheral neuropathy was 3.6 (3.9) years.

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;69:274–283 279

www.jnnp.com

on July 9, 2022 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.274 on 1 August 2000. D

ownloaded from

The randomisation procedure resulted inbalanced treatment groups for patient char-acteristics and neurological abnormalities(table).

Three patients in the á-IFN groupwithdrew from treatment, two because ofside eVects (one at day 30 for diarrhoea andone at day 60 for influenza symptoms) andone at day 60 because of worsening ofthe neuropathy. No patients had to stoptreatment because of haematological toxic-ity.

The mean CNDS did not change signifi-cantly in either group: in the á-IFN group, itmoved from 31.4 at baseline to 28.5 at 6months, in the placebo group from 30.3 atbaseline to 27.8 at 6 months. The absolutediVerences were close in the two randomisedgroups—namely, 1.8 in the á-IFN group and−2.5 in the placebo group (p=0.84) and therelative diVerences were also close (−6%v−6.5% respectively, p=0.79). In bothgroups, three out of 12 patients (25%) hadimprovement in CNDS of more than 20%(p=1.00). Electrophysiological data wereavailable in nine patients treated with á-IFNand in 11 patients treated with placebo anddid not detect significant improvement (datanot shown).

In this double blind study of á-IFN versusplacebo, we did not confirm the eYcacy ofá-IFN in peripheral neuropathy associatedwith a monoclonal anti-MAG IgM assuggested in a preliminary phase II openstudy.14 This discrepancy is not easy toexplain. The mean baseline neurologicalscores, the number of patients previouslytreated, and the disease duration were thesame in the two studies. However, both stud-ies dealt with small cohorts. We think thatthe eVect found in our preliminary studycould have been amplified by the enthusiasmof physicians and patients in favour of inter-feron, a new therapeutic strategy at that timein neurological diseases, given that the trialwas not blind. Both physicians and patientsknew that it was not a placebo group. Inter-estingly, in our preliminary study, thedecrease of the CNDS was mainly due toimprovement in sensory symptoms (most ofthem subjective) and to subjective assess-ment by the patient. Moreover, we could notelucidate the potential mechanism of actionof á-IFN as neither the level if monoclonalIgM, nor the anti-MAG antibody activitywas modified.

In conclusion, these disapointing results ofá-IFN in monoclonal IgM associated neu-ropathy point out to the need of double blindrandomised studies versus placebo in neuro-logical diseases where sensory symptoms arepredominant. In monoclonal IgM associatedneuropathy, new strategies leading to eradica-tion of the B cell clone secreting monoclonalIgM, such as the use of fludarabine15 or anti-Bcell monoclonal antibodies,16 should be testedin further studies.

This work was supported by a grant from TheDèlègation de la Recherche Clinique (AssistancePublique-Hôpitaux de Paris).

XAVIER MARIETTEJEAN-CLAUDE BROUET

Service d’Immuno-Hèmatologie, Hôpital Saint-Louis,1 Avenue Claude Vellefaux, 75475 Paris cedex 10,

France

SYLVIE CHEVRETDèpartement de Biostatistique et InformatiqueMèdicale, Hôpital Saint-Louis, Paris, France

JEAN-MARC LEGERService de Neurologie, Hôpital Pitiè-Salpétriëre, Paris,

France

PIERRE CLAVELOUService de Neurologie, Hôpital Fontmaure,

Chamaliëres, France

JEAN POUGETService de Neurologie, Hôpital de la Timone,

Marseille, France

JEAN-MARC VALLATService de Neurologie, Hôpital Dupuytren, Limoges,

France

CHRISTOPHE VIALService de Neurologie, Hôpital Wertheimer, Lyon,

France

Correspondence to: Professor Jean-Claude [email protected]

1 Latov N, Sherman WH, Nemni R, et al. Plasma-cell dyscrasia and peripheral neuropathy with amonoclonal antibody to peripheral-nerve my-elin. N Engl J Med 1980;303:618–21.

2 Smith IS, Kahn SN, Lacey BW, et al. Chronicdemyelinating neuropathy associated with be-nign IgM paraproteinemia. Brain 1983;106:169–95.

3 Dellagi K, Dupouey P, Brouet JC et al. Walden-strom’s macroglobulinemia and peripheralneuropathy: a clinical and immunologic studyof 25 patients. Blood 1983;62:280–5.

4 Braun PE, Frail DE, Latov N. Myelin-associated glycoprotein is the antigen for amonoclonal IgM in polyneuropathy. J Neuro-chem 1982;39:1261–5.

5 Chou DKH, Ilyas AA, Evans JE, et al. Structureof a glycolipid reacting with monoclonal IgMin neuropathy and with HNK1. BiochemBiophys Res Commun 1985;128:283.

6 Hauttecœur B, Schmitt C, Dubois C, et al.Reactivity of human monoclonal IgM withnerve glycosphingolipids. Clin Exp Immunol1990;80:181–5.

7 Bollensen E, Steck A, Schachner M. Reactivityof the peripheral myelin glycoprotein PO inserum from patients with monoclonal IgMgammapathy and polyneuropathy. Neurology1988;38:1266–70.

8 Mendell JR, Sahenk Z, Whitaker JN, et al.Polyneuropathy and IgM monoclonalgammopathy: studies on the pathogenic role ofanti-myelin-associated glycoprotein antibody.Ann Neurol 1985;17:243–54.

9 Monaco S, Bonetti B, Ferrari S, et al.Complement-mediated demyelination in pa-tients with IgM monoclonal gammopathy andpolyneuropathy. N Engl J Med 1990;322:649–52.

10 Tatum AH. Experimental paraprotein neu-ropathy, demyelination by passive transfer ofhuman IgM anti-myelin-associated glycopro-tein. Ann Neurol 1993;33:502–6.

11 Dancea S, Dellagi K, Renaud F, et al. EVect ofpassive transfer of human anti-myelin-associated glycoprotein IgM in marmoset.Autoimmunity 1989;3:29–37.

12 Nobile-Orazio E, Baldini L, Barbieri S, et al.Treatment of patients with neuropathy andanti-MAG IgM M-proteins. Ann Neurol 1988;24:93–7.

13 Oksenhendler E, Chevret S, Léger JM, et al.Plasma exchange and chlorambucil in polyneu-ropathy associated with monoclonal IgM gam-mopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1995;59:243–7.

14 Mariette X, Chastang C, Clavelou P, et al. Arandomized clinical trial comparing á inter-feron and intravenous immunoglobulin inpolyneuropathy associated with monoclonalIgM. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997;63:28–34.

15 Wilson HC, Lunn MP, Schey S, et al. Successfultreatment of IgM paraproteinaemic neu-ropathy with fludarabine. J Neurol NeurosurgPsychiatry 1999;66:575–80.

16 Levine TD, Pestronk A. IgM antibody-relatedpolyneuropathies: B-cell depletion chemo-therapy using Rituximab. Neurology 1999;52:1701–4.

Reversible posteriorleukencephalopathy syndrome inducedby granulocyte stimulating factorfilgrastim

Posterior leukencephalopathy syndrome ischaracterised by visual disturbances, alteredmental status, drowsiness, seizures, head-ache, and occasionally focal neurologicalsigns. It is usually associated with severehypertension and has most often been seen inpatients treated with immunsuppressivedrugs such as cyclosporin A, tacrolimus, andinterferon-á.1 2

The granulocyte and granulocyte macro-phage stimulating factor filgrastim (Neupo-gen®) is used in chemotherapy induced bonemarrow suppression. By contrast with mol-gramostim (Leukomax®) filgrastim is sup-posed to have fewer CNS side eVects. Intrac-ranial hypertension and convulsions havebeen reported after molgrastim therapy. Onlyone case of recurring encephalopathy andfocal status epilepticus due to filgrastim ispublished.3 In that case the contrast en-hanced CT was normal.

We report a case of reversible posteriorleukencephalopathy syndrome with transientbilateral changes in the occipital and parietalregions involving the white matter onMRI induced by filgrastim. This is to ourknowledge the first with reversible changeson MRI to be reported after filgrastimtherapy.

A 45 year old previously healthy womenwas diagnosed with centrocytic centroblasticnon-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with intermediateto high malignancy in August 1999. The firstcycle of chemotherapy with vincristin,ifosfamide, and etoposid was well tolerated.Two days after termination of chemotherapyshe received subcutaneously 300 µg filgras-tim (Neupogen) daily because of bone mar-row suppression with leukopenia for 9 days.After 3 days the dose was increased to600 µg/day. One day after termination offilgrastim and almost 2 weeks afterchemotherapy, she developed acute corticalblindness within 30 minutes. On the nextday simple partial and complex partialseizures, non-convulsive status, agitation,and desorientation followed. Brain MRIobtained 1 day later showed bilateral hyper-intensities in the parietal and occipitalregions involving white matter with someinvolvement of the overlaying grey matter onproton density images (figure). Non-convulsive status with somnolence anddisorientation were documented by EEG,which showed a bilateral parieto-occipitalfocus with continuous rhythmic delta

Patients’ characteristics according to treatment group

á-IFN (n=12) Placebo (n=12)

Age (y) 67.5 (61.5–74.5) 67.5 (66–73.5)Male sex 6 (50) 10 (83)Patients never previously treated 7 (58) 6 (50)Duration of neuropathy (y) 3 (2–10) 3.5 (1–9.5)Patients with bone marrow lymphoid infiltrate 2 (17) 1 (8)Clinical score:

M0 34 (25.5–35.5) 30 (25.5–36.5)M3 28 (21–35) 28 (21.5–33)M6 31 (27.5–35) 28 (24–31)

Values are median (25th–75th percentiles) or n (%).

280 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;69:274–283

www.jnnp.com

on July 9, 2022 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.274 on 1 August 2000. D

ownloaded from

activity, sharp waves, and spike wave com-plexes; status could be terminated with 1 mgintravenous clonazepam.

Lumbar puncture and ultrasonography ofthe vertebral and basilar arteries did not showany abnormalities. Transoesophageal echo-cardiography showed normal left ventricularfunction. Routine biochemistry includingelectrolytes, creatinine, and blood urea nitro-gen were normal throughout except in-creased C reactive protein (due to tumour).Haematological values showed pancytopenia.There was no evidence for viral and bacterialinfection. A pleural eVusion on the left sidehad developed before chemotherapy. A chestradiograph was now normal. Blood pressurewas normal throughout.

As no other diagnosis could be ascertained,a causal relation with filgrastim, her sole newmedication, was discussed. The patient wastreated with a diuretic (furosemid), a neu-roleptic (haloperidol), and anticonvulsants(phenytoin and clonazpam intravenously).The syndrome gradually remitted after 1week without residue. The patient was wellthereafter. Control MRI 7 days after the onsetof symptoms showed hyperintensities in theparietal and occipital regions involving whitematter in marked resolution on protondensity images (figure).

This case demonstrates that the granulo-cyte stimulating factor filgrastim can havemarked neurotoxic side eVects in the form ofa typical posterior leukencephalopathy syn-drome in the absence of severe hypertension.The pathogenesis of posterior leukencepha-lopathy syndrome has remained illusive. It

probably reflects the increased vulnerabilityof posterior regions of the brain to diVerentvascular, toxic, or metabolic disturbances. Ithas been suggested that the predelection forthe posterior circulation is a consequence ofpoorer control of local cerebral autoregula-tion due to the relatively poorer sympatheticinnervation. It cannot be stated whether inthis case filgastrim neurotoxicity was due todirect toxic or transient vascular damage, byanalogy with CNS toxicity reported afterinterleukine-2 therapy.4 5 Both mechanismsseem possible.

T LENIGERO KASTRUPHC DIENER

Department of Neurology, University of Essen,Hufelandstrasse 55, 45122 Essen, Germany

Correspondence to: Dr Tobias [email protected]

1 Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, et al. Areversible posterior leukencephalopathy syn-drome. N Engl J Med 1996;334:494–500.

2 Ay H, Buonanno FS, Schaefer PW, et al. Poste-rior leukencephalopathy without severe hyper-tension. Utility of diVusion-weighted MRI.Neurology 1998;51:1369–76.

3 Kastrup O, Diener HC. Granulocyte-stimulating factor filgrastim and molgrastiminduced recurring enecephalopathy and focalstatus. J Neurol 1997;244:274–5.

4 Formann AD. Neurological complications ofcytokine therapy. Oncology 1994;8:105–10.

5 Illowsky Karp B, Jang JC, et al. Multiple cerebrallesions complicating therapy withinterleukin-2. Neurology 1996;47:417–24.

Acute adverse reaction to fentanyl in a55 year old man

We report an acute drug induced adversereaction to fentanyl that was not immediatelyrecognised as such. A 55 year old policeoYcer was given a small dose of diazepam (5mg) and fentanyl (0.05 mg) for the treatmentof left chest pain. Immediately after receivingthe medication, the patient developed acuteconfusion, intermittent somnolence, andstupor, and fluctuating tetraparesis. Beforethe onset of symptoms, no relevant hypoxiaor hypoglycaemia were found. Pre-existingmedication consisted of 20 mg amitryptilineand 1000 mg metformin a day. On initialexamination, the most obvious symptomsincluded profuse sweating, bilateral miosis(pinpoint pupils), and severe generalisedmyoclonus predominantly aVecting the face.Babinski‘s sign was negative on both sides.The patient showed severe fluctuating tetra-paresis. Investigation of the cranial nervesshowed no abnormalities. On admission inour institution, the patient immediatelyunderwent intubation and artificial ventila-tion for suspected pulmonary aspiration.Thiamin was started at 100 mg thrice daily.Myocardial infarction and dissection of theaorta were ruled out. The previously givendosage of fentanyl and diazepam did notseem to explain the current neurologicalcondition of the patient. The symptoms ofdisturbance of conciousness, hemiparesis,generalised myoclonus, and pinpoint pupilspointed to brainstem injury. To rule outbasilar artery thrombosis, CT angiographywas performed. There were no pathologicalfindings in the brainstem or the basilarartery.

Transcranial Doppler ultrasound and sen-sory evoked potentials were normal. TheEEG under sedation with midazolam andfentanyl showed intermittent bilateral syn-chronised frontal delta rhythms. Systolicblood pressure was slightly increased, be-tween 140 and 180 mm Hg. Due to thepatient‘s development of pneumonia, artifi-cial ventilation was continued, and furthersedation was given with fentanyl/midazolam.Sedation was continued for 72 hours, with aninfusion of fentanyl (0.157 mg/h) and mida-zolam (3.3 mg/h) for ventilation therapy.After sedation was stopped, the distinctiveneurological symptoms abruptly improved.Within a few hours the patient was extu-bated. He then seemed normal, except forslight disorientation and agitation. Twelvehours after cessation of sedation, the patientwas normal. To clarify and confirm the diag-nosis of an adverse reaction to fentanyl, wecarried out a provocation test after obtainingfull informed consent. A dose of 0.1 mg fen-tanyl intravenously was enough to induceagitation, generalised myoclonus, and parox-ysmal dystonic movements and rigor thatparticularly aVected the legs. No cognitivedisturbances were apparent. The fentanyldose was then increased to a total of 0.2 mg.At this point, a 6 mg dose of diazepam wasgiven but did not improve the agitation of thepatient. In fact the patient reported in-creased agitation. Administration of a mor-phine antagonist, naloxone (0.8 mg intrave-nously) dramatically improved his condition,completely normalising the myoclonus,rigor, and paroxysmal movements. No fur-ther improvement occurred on administra-tion of the benzodiazepine antagonist fluma-zenil (0.25 mg intravenously). As the eVectof the naloxone wore oV, there was a

Left: bilateral PD hyperintensities in the parietal and occipital regions at the onset of symptoms. Right:bilateral PD hyperintensities in marked resolution 7 days later.

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;69:274–283 281

www.jnnp.com

on July 9, 2022 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.274 on 1 August 2000. D

ownloaded from

reappearance of the dystonic movements.Under these conditions, the patient pre-sented with distinct bilateral miosis, but noother disturbances.

Through this provocation test, the diagno-sis was confirmed. As a result of an adversereaction to fentanyl, the patient experiencedan acute and unusual neurological syndrome.The clinical symptoms were agitation, gener-alised myoclonus, intermittent disturbancesof consciousness, fluctuating bilateral hemi-paresis, and pinpoint pupils. The diagnosisremained obscure for 72 hours due to thecontinuing ventilation, sedation, and analge-sic treatment with fentanyl; indeed, it was thecontinuing administration of fentanyl thatwas maintaining the symptoms. Both theimprovement after cessation of fentanyl, andthe controlled provocation test confirmed thediagnosis.

In recent years, various central side eVectsof opioids have been described. Theseinclude generalised myoclonus, hyperalgesia,grand mal seizures, and agitation.1–4 Althoughsome reports have shown unexpected cer-ebral side eVects after low doses of fentanyl,5

in most cases this type of eVect developed inpatients receiving high doses of opiates forprolonged periods.1–3

Opiate induced myoclonus is often gener-alised and is either periodic or associated withrigidity, often occurs in the context of under-lying medical conditions, and usually re-sponds to either naloxone or benzodi-azepines.4 The mechanisms responsible forthese adverse eVects are not exactly known,but opiatergic, serotonergic, dopaminergic,and other mechanisms are considered.4 Theinteresting feature of this particular case wasthe possibility of confusion of an acute fenta-nyl induced adverse syndrome with basilarartery thrombosis.

HANS JOERG STUERENBURGJAN CLAASSEN

CHRISTIAN EGGERSHANS CHRISTIAN HANSEN

Neurological Department, University HospitalHamburg-Eppendorf, Martinistrasse 52, 20246

Hamburg, Germany

Correspondence to: Dr HJ [email protected]

1 Sjogren P, Erikson J. Opioid toxicity. Curr OpinAnesthesiol 1994;7:465–9.

2 De Stoutz ND, Bruera E, Suarez-Almazor M.Opioid rotation (OR) for toxicity reduction interminal cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Man-age 1995;10:378–84.

3 Bruera E, Pereira J. Acute neuropsychiatricfindings in a patient receiving fentanyl for can-cer pain. Pain 1977;69:199–201.

4 Lauterbach EC. Hiccup and apparent myo-clonus after hydrocodone: review of the opiate-related hiccup and myoclonus literature. ClinNeuropharmacol 1999;22:8–92.

5 Henderson GL. Fentanyl-related deaths: demo-graphics, circumstances and toxicology of 112patients. J Forensic Sci 1991;36:422–33.

Relapsing alternating ptosis in twosiblings

In this Journal, Peatfield described the recur-rence of cluster headaches presenting with avirtually painless Horner’s syndrome in a 56year old man.1 This publication causedcontroversy on the dissociation betweenautonomic dysfunction and pain during clus-ter headache.2 We add to this discussion ourreport on relapsing alternating ptosis in twosiblings:

A 46 year old woman had intermittent epi-sodes of alternating ptosis for more than 8years. Her 47 year old sister was aVected

similarly. As shown in figure 1, attacksoccurred more often than once a month witha mean duration of the episodes of 8 days(range 3–14 days). Intrinsic oculomotormuscles and the bulbar muscles were spared(fig 2). She never complained about doublevision. Elevating and maintaining the ptoticeyelid in a fixed position during sustainedupward gaze did not result in a drop of theopposite eyelid.3 Signs of autonomic dysfunc-tion and miosis were absent. The ptosis wasnever accompanied by miosis. There was nohistory of migraine or cluster headache.However, during the episodes they experi-enced some mild aching at the frontal regionof the aVected side. On the serotonin antago-nist pizotifen, the younger sister felt improveddue to slightly prolonged symptom free inter-vals. However, 60 mg prednisone every dayfor 6 weeks did not change the occurrence ofptosis.

On repeated neurological examination,there was no abnormality apart from thefluctuating ptosis. Magnetic resonance imag-ing of the brain, the orbital region, and thecervicothoracic spinal cord segments werenormal. Laboratory studies showed no ab-normality. Westergren sedimentation rate andserum creatine kinase activity were normal.Repeated tests for antiacetylcholine receptorantibodies were negative. Low rate repetitivenerve stimulation did not result in pathologi-cal decremental responses. Thyroid hor-mones and antibodies were in the normalrange and absent, respectively. In the symp-tom free interval, pupillary responses to vari-ous pharmacological agents did not indicate asympathetic dysfunction.

Relapsing alternating ptosis in two sisters isunique. In some aspects, our observationresembles Bielschowsky’s relapsing alternat-ing ophthalmoplegia.4 Distinctive clinicalfeatures of this rare syndrome are theintermittent evolution of external ophthal-moplegias, the alternate involvement of oneeye after the other, the constant sparing of theintrinsic oculomotor muscles, and the ab-sence of pain.

We think that our finding of relapsingalternating ptosis is related to intermittentsympathetic dysfunction. Interestingly, in asubgroup of patients with cluster headache a“partial” Horner’s syndrome may developduring each attack and disappear as theattack subsides. The term “partial” Horner’ssyndrome indicates that in patients with clus-ter headache one or two components of the

typical Horner’s syndrome are present—thatis, miosis or ptosis, whereas a third character-istic, anhidrosis, is lacking or even replaced byhyperhidrosis.5 Some of the patients withcluster headache even show a permanentHorner-like syndrome on the symptomaticside.6 Several studies on the pupil responsive-ness in patients with cluster headache

Figure 1 Occurrence of ptosis over a period of 21 months (protocol of the 46 year old patient). Oneeye after the other was aVected intermittently (filled bars=presence of ptosis.

400 500

DaysR

igh

t si

ded

pto

sis

Left

sid

ed p

tosi

s

3002000 100 600

Figure 2 Alternating ptosis: representativefindings between November 1998 (11/98) andDecember 1999 (12/99). Note the absence ofmiosis. The ptosis resolved completely each time.

282 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;69:274–283

www.jnnp.com

on July 9, 2022 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://jnnp.bmj.com

/J N

eurol Neurosurg P

sychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.274 on 1 August 2000. D

ownloaded from

indicate that dysfunction of the sympatheticnervous system, whether peripheral orcentral, is involved in the pathophysiologyof the cluster headache.6 Additionally,alternating Horner’s syndrome has beenreported in patients with lesions of the lowercervical und upper thoracic spinal cordsegments.7 In those cases, Horner’s syn-drome may alternate sides at intervals rang-ing from 2 hours to 2 weeks. Horner’ssyndrome alternating on a daily basis canoccur rarely in multisystem atrophy withdysautonomia.7 Unfortunately, we cannotoVer any proof for a sympathetic dysfunctionin our patients.

J P SIEBA HARTMANN

Department of Neurology, University Hospital, Bonn,D-53105, Germany

Correspondence to: Dr JP [email protected]

1 Peatfield RC. Recurrence of cluster headachespresenting with virtually painless Horner’s syn-drome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry1995;59:196–7.

2 Gupta VK. Painless Horner’s syndrome in clus-ter headache. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry1996;60:462–3.

3 Gorelick PB, Rosenberg M, Pagano RJ. En-hanced ptosis in myasthenia. Arch Neurol 1981;38:531.

4 Bielschowsky A. Beitrag zur Kenntnis derrezidivierenden und alternierenden Ophthal-moplegia exterior. Albrecht Von Graefes ArchOphthalmol 1915;40:433–45.

5 Sjöqvist F. Cluster headache. In: Vinken PJ,Bruyn GW, Klawans HL, et al, eds. Handbook ofclinical neurology: headache. Amsterdam: Else-vier, 1986: 217–46.

6 Havelius U, Heuck M, Milos P, Hindfeldt B.Ciliospinal reflex response in cluster headache.Headache 1996;36:568–73.

7 Hopf HC. Intermittent Horner’s syndrome onalternate sides: a hint for locating spinallesions. J Neurol 1980;224:155–7.

CORRESPONDENCE

Snapshot view of emergencyneurolosurgical head injury care

Crimmins and Palmer1 highlight the varia-tions in clinical practice in the use of hyper-ventilation, anti-oedema agents, anticonvul-sant drugs, and prophylactic antibiotics inpatients with head injury. Although some ofthis may be due to variations in the standardof clinical care, at least some of the variationmay be attributable to lack of really reliable