Leaders’ Personal Wisdom and Leader-Member Exchange Quality: The Role of Individualized...

Transcript of Leaders’ Personal Wisdom and Leader-Member Exchange Quality: The Role of Individualized...

Leaders’ Personal Wisdom and Leader–Member ExchangeQuality: The Role of Individualized Consideration

Hannes Zacher • Liane K. Pearce • David Rooney •

Bernard McKenna

Received: 5 December 2012 / Accepted: 24 March 2013

� Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013

Abstract Business scholars have recently proposed that

the virtue of personal wisdom may predict leadership

behaviors and the quality of leader–follower relationships.

This study investigated relationships among leaders’ per-

sonal wisdom—defined as the integration of advanced

cognitive, reflective, and affective personality characteris-

tics (Ardelt, Hum Dev 47:257–285, 2004)—transforma-

tional leadership behaviors, and leader–member exchange

(LMX) quality. It was hypothesized that leaders’ personal

wisdom positively predicts LMX quality and that intel-

lectual stimulation and individualized consideration, two

dimensions of transformational leadership, mediate this

relationship. Data came from 75 religious leaders and 1–3

employees of each leader (N = 158). Results showed that

leaders’ personal wisdom had a positive indirect effect on

follower ratings of LMX quality through individualized

consideration, even after controlling for Big Five person-

ality traits, emotional intelligence, and narcissism. In

contrast, intellectual stimulation and the other two dimen-

sions of transformational leadership (idealized influence

and inspirational motivation) did not mediate the positive

relationship between leaders’ personal wisdom and LMX

quality. Implications for future research on personal wis-

dom and leadership are discussed, and some tentative

suggestions for leadership development are outlined.

Keywords Personal wisdom � Transformational

leadership � Leader–member exchange

Lifespan scholars have described wisdom as a factor con-

tributing to optimal human development (Baltes and Smith

2008), personality researchers consider wisdom a universal

value (Roe and Ester 1999; Ros et al. 1999), and positive

psychologists have portrayed wisdom as a desirable character

strength (Peterson and Seligman 2004; Schwartz and Sharpe

2006). Wisdom researchers agree that personal wisdom is a

uniquely human characteristic that involves superior, expe-

rience-driven cognitive and emotional development resulting

in a life that is beneficial for oneself and other people (Baltes

and Staudinger 2000; Jeste et al. 2010). Psychological wisdom

research is now considered a growing field of empirical

inquiry (Karelitz et al. 2010; Staudinger and Gluck 2011;

Trowbridge 2011). Consistent with this trend, wisdom con-

ceived as an individual virtue is receiving increased attention

in the field of business ethics (Bragues 2006; Jones 2005;

Moberg 2007, 2008; Roca 2008; Spiller et al. 2011). Several

business scholars have suggested in recent years that personal

wisdom may be an attribute of outstanding leaders who con-

tribute to the personal development and well-being of their

followers and who facilitate positive relationships at work

(Bierly et al. 2000; Biloslavo and McKenna 2013; Kessler and

Bailey 2007; McKenna et al. 2009; Mumford 2011; Nonaka

and Takeuchi 2011; Nonaka and Toyama 2007; Srivastva and

Cooperrider 1998; Yang 2011).

However, despite the increased interest in wisdom in the

business literature, so far little empirical research on

H. Zacher (&) � L. K. Pearce

School of Psychology, The University of Queensland, Brisbane,

QLD 4072, Australia

e-mail: [email protected]

L. K. Pearce

e-mail: [email protected]

D. Rooney � B. McKenna

UQ Business School, The University of Queensland, Brisbane,

QLD 4072, Australia

e-mail: [email protected]

B. McKenna

e-mail: [email protected]

123

J Bus Ethics

DOI 10.1007/s10551-013-1692-4

wisdom and leadership in organizational settings exists.

This is surprising, given that the virtue of personal wisdom

may contribute to a better understanding of leadership

processes and outcomes beyond established individual

difference predictors of leadership such as the Big Five

personality traits (Judge et al. 2002), emotional intelligence

(Barling et al. 2000; Wong and Law 2002), and narcissism

(Judge et al. 2006). Empirical research on personal wisdom

and leadership may also be practically important as studies

suggest that personal wisdom can be developed using

techniques that involve elements such as distancing oneself

from difficult events (Kross and Grossmann 2012).

Two recent exceptions to the general dearth of research

on wisdom and leadership are the studies by Yang (2011)

and Greaves et al. (2013). Yang (2011) investigated how

wisdom (conceptualized as a process encompassing cog-

nitive integration, embodiment, and positive effects; see

also Yang 2008a) is displayed in leadership contexts.

Specifically, Yang (2011) analyzed transcripts of semi-

structured interviews with 40 leaders nominated as wise.

The results of Yang’s (2011) study contribute to the liter-

ature by showing that leaders’ reports of wisdom often

involved leadership behaviors that have positive effects at

organizational and societal levels (e.g., solving problems,

implementing visions, and founding new ventures). As

Yang’s (2011) study focused exclusively on outstanding

leaders nominated as wise as well as relatively broad out-

comes, it was unable to determine whether individual dif-

ferences in personal wisdom can account for variation in

leadership behaviors and outcomes.

Greaves et al. (2013) investigated relationships between

five dimensions of general wisdom as conceptualized by

the Berlin wisdom paradigm (Baltes and Staudinger 2000)

and transformational leadership in a sample of high school

employees. These authors reported that two wisdom

dimensions had contradictory relationships with transfor-

mational leadership. Specifically, leaders’ relativism of

values and life priorities negatively predicted peer ratings

of transformational leadership, and leaders’ recognition

and management of uncertainty positively predicted peer

ratings of transformational leadership. The other three

wisdom dimensions of the Berlin wisdom paradigm, rich

factual knowledge about life, rich procedural knowledge

about life, and lifespan contextualism, were not signifi-

cantly related to transformational leadership. The mixed

findings of Greaves et al.’s (2013) study may be due to its

exclusive focus on general wisdom (i.e., insights into life

in general, from an observer’s perspective; Mickler and

Staudinger 2008). It may be possible that personal wisdom

(i.e., insights into one’s own life; Mickler and Staudinger

2008) is a more relevant construct with regard to the

interpersonal process of leadership. In addition, Greaves

et al. (2013) did not distinguish between different

dimensions of transformational leadership and did not

assess the quality of leader–follower relationships.

The goal of our current study is to contribute to the

literatures on wisdom and leadership, and to address the

limitations of previous empirical studies, by examining

relationships among leaders’ personal wisdom, leader–

member exchange (LMX) quality, and different dimen-

sions of transformational leadership. Specifically, we will

derive and test hypotheses on the mediating role of two

dimensions of transformational leadership in the relation-

ship between leaders’ personal wisdom and LMX quality.

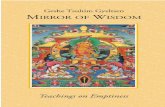

A conceptual model of our study is shown in Fig. 1. In a

nutshell, we expect that leaders’ personal wisdom is posi-

tively related to LMX quality, and that leaders’ intellectual

stimulation and individualized consideration behaviors

explain this relationship. In the following sections, we

define and explain the central constructs of personal wis-

dom, LMX quality, and transformational leadership; then

summarized relevant theories on wisdom and leadership

and develop our hypotheses; and finally, we describe and

discuss the methods and results of an empirical study

designed to test our hypotheses.

Personal Wisdom

We used Ardelt’s (1997, 2000, 2003, 2004) conceptuali-

zation of personal wisdom in this study, which is based on

the early psychological approaches to wisdom by Clayton

and Birren (1980; see also Birren and Fisher 1990). Con-

sistent with Clayton and Birren (1980), Ardelt (2004)

defined personal wisdom as a distinct personality charac-

teristic that integrates three components. Specifically, she

proposed that that the simultaneous presence of advanced

cognitive, reflective, and affective personality attributes is

necessary and sufficient for a person to be considered wise.

The cognitive component of personal wisdom involves

superior knowledge, understanding, and acceptance of life

and human nature, and a continuous desire to comprehend

the meaning of intra- and interpersonal events (Ardelt

2004). The reflective component refers to the abilities for

self-insight, self-examination, and to perceive events from

multiple perspectives (Ardelt 2004). Finally, the affective

component captures an individual’s consideration and

empathetic and compassionate love for others (Ardelt

2004). Over the past two decades, Ardelt’s research

showed that personal wisdom positively predicted life

satisfaction (Ardelt 1997; Bergsma and Ardelt 2012),

physical health and the quality of family relationships

(Ardelt 2000), mastery and psychological well-being

(Ardelt 2003), and forgiveness of self, others, and situa-

tions (Ardelt 2011). Critics of Ardelt’s approach to per-

sonal wisdom have questioned whether the construct is

H. Zacher et al.

123

sufficiently distinct from established personality charac-

teristics and emotional intelligence, and also raised con-

cerns about assessing wisdom with a self-report

questionnaire (Staudinger et al. 2005; Staudinger and

Gluck 2011; Zacher et al. 2013).

LMX Quality

According to LMX theory, leaders develop, maintain, and

end unique exchange relationships with each of their fol-

lowers over time (Graen and Uhl-Bien 1995; Liden et al.

1997). The development and maintenance of high-quality

LMX relationships are important for leadership success.

High-quality LMX relationships are characterized by

mutual liking, trust, respect, obligation, and reciprocal

influence between leaders and followers (Graen and Uhl-

Bien 1995). In these relationships, leaders support their

followers beyond what is generally expected, and followers

engage in more autonomous and responsible work activi-

ties. In contrast, in low-quality LMX relationships, leaders

provide their followers only with what they need to per-

form, and followers do only their prescribed job tasks.

Meta-analyses showed that high-quality LMX relationships

have positive effects on follower satisfaction, performance,

and organizational citizenship behavior (Gerstner and Day

1997; Ilies et al. 2007). Even though LMX is a widely

accepted construct in the leadership literature (Avolio et al.

2009), researchers have criticized that it is rarely concep-

tualized as a developmental process (Dienesch and Liden

1986), and that the agreement between leaders’ and fol-

lowers’ assessments of LMX quality tends to be low

(Gerstner and Day 1997).

Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership is one of the most widely

researched contemporary leadership styles (Avolio et al.

2009; Hiller et al. 2011). It has been defined as a leadership

approach that involves leaders influencing their followers

through four behavioral dimensions labeled idealized

influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation,

and individualized consideration (Bass 1985; Bass and

Avolio 1994). Idealized influence means that the leader

acts as and is perceived by followers as a role model, and

inspirational motivation involves communicating an

inspirational and motivating vision of the future (Bass and

Avolio 1994). The combination of idealized influence and

inspirational motivation has been referred to as charisma

(Avolio et al. 1999; Zacher et al. 2011). Intellectual stim-

ulation entails the leader encouraging independent and

creative thinking among followers, and individualized

consideration involves the leader being caring and nurtur-

ing as well as supporting each followers’ personal devel-

opment (Bass and Avolio 1994).

The business literature has described two sides of

transformational leadership. On the one hand, proponents

of transformational leadership have argued that it repre-

sents a value-based framework and involves a desirable

Personal Wisdom

Leader-Member Exchange Quality

Idealized Influence

Inspirational Motivation

Intellectual Stimulation

Individualized Consideration

.13ns .49**

.26ns

.27*

.24ns -.03ns

-.05ns

.33**

Indirect effect of personal wisdom on leader-member exchange quality (through individualized consideration): .09*

Direct effect of personal wisdom on leader-member exchange quality (before and after controlling for transformational leadership dimensions): .30* .16ns→

Fig. 1 Conceptual model and

summary of results. Solidarrows represent hypothesized

paths, dashed arrows represent

paths that were not

hypothesized. Standardized

regression coefficients (b) are

reported. *p \ 0.05;

**p \ 0.01; ns not significant

Leaders’ Personal Wisdom and Leader–Member Exchange Quality

123

leadership style that leads to beneficial follower and

organizational outcomes (Paarlberg and Lavigna 2010).

For example, Crawford (2005) argued that transformational

leadership involves a process in which ‘‘leaders and fol-

lowers raise one another to higher levels of morality and

motivation’’ (p. 8). This is supported by empirical research

showing positive relationships between moral reasoning

and ethical integrity on the one hand and transformational

leadership on the other (Parry and Proctor-Thomson 2002;

Turner et al. 2002). In addition, research has found that

transformational leadership is positively related to follower

satisfaction and motivation, LMX quality and, subse-

quently, follower performance, organizational citizenship

behavior, and organizational productivity (Bass et al. 2003;

Dvir et al. 2002; Geyer and Steyrer 1998; Judge and Pic-

colo 2004; Podsakoff et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2005).

On the other hand, critical management theorists have

questioned the tendency to characterize leaders as

extraordinary heroes who can easily charm followers

(Fairhurst 2007; Tourish 2008). They have also argued that

transformational leadership theory prioritizes corporate

cohesion and conformity over constructive dissent (Keeley

1995; Tourish and Pinnington 2002; Tourish and Vatcha

2005). However, independent thought and constructive

dissent are seen as important characteristics in modern

knowledge economies (Rooney et al. 2003; Rooney et al.

2013; Tourish and Vatcha 2005). Other researchers have

criticized transformational leadership theory because it

tends to neglect the institutional context and organizational

constraints (Currie and Lockett 2007). Finally, business

scholars have suggested that transformational leadership,

especially the charisma dimension, may also have a risky

‘‘dark side’’ that involves exaggeration, losing touch with

organizational realities, persistence in the face of negative

outcomes, dependency of followers, and manipulating

followers for personal gain (Alimo-Metcalfe and Alban-

Metcalfe 2005; Allix 2000; Conger 1990; Whetstone

2001). We account for the potentially two-sided nature of

transformational leadership in this study by examining

relationships between personal wisdom and the four sepa-

rate transformational leadership dimensions. In particular,

we expect that personal wisdom is positively related to

intellectual stimulation and individualized consideration,

whereas we do not expect positive relationships with ide-

alized influence and inspirational motivation.

Theory and Development of Hypotheses

A number of theoretical frameworks exist in the organi-

zational and leadership literatures that have attempted to

link the constructs of wisdom and leadership (Bigelow

1992; Jones 2005; McKenna et al. 2009; Nonaka and

Takeuchi 2011; Yang 2008a). In an early review on the

topic, Bigelow (1992) proposed that leaders may expand

their personal wisdom by moving to longer term strategies,

learning from experiences, expanding their practical and

meta-knowledge, and gaining a sense of what really is

important in life. Jones (2005) discussed the relationship

between wisdom and leadership based on the Innate to

Intent theory. According to this theory, wisdom is an

awareness of the true means and ends of human activity

that guides leaders to make better decisions based on an

improved knowledge of their values, priorities, and goals.

More recently, Yang (2008a, b, 2011) defined wisdom

as a process consisting of three components: cognitive

integration, embodiment of ideas through action, and

positive effects for self and others. Analyzing semi-struc-

tured interviews, Yang (2008b) found that wisdom mani-

fested itself through striving for the common good,

achieving and maintaining life satisfaction, personal

development, effective problem solving, and resilience

when facing adversity. In addition, Yang (2011) found that

reports of wisdom often involved leadership, which was

broadly operationalized as formal or informal transactional

events that occur between a leader and his or her followers.

Taking a sociological perspective, McKenna et al. (2009)

proposed an association between wisdom and leadership

based on a combination of Aristotle’s writings and psy-

chological wisdom research. They suggested that wise

leaders use reason and careful observation, take non-

rational and subjective elements into account when making

decisions, and value humane and virtuous outcomes. They

further proposed that wise leaders are practical, articulate,

and understand the esthetic aspect of their work. Finally,

Nonaka and Takeuchi (2011) postulated that wise leaders

make decisions after careful consideration of their benefi-

cial impact on an organization and society, understand the

fundamental nature of situations and problems, facilitate

interactions between employees and leaders, communicate

in inspiring ways, use political power to solve conflicts,

and foster other people’s wisdom. In sum, these theoretical

frameworks and Yang’s (2011) empirical work suggest that

leaders’ personal wisdom may be a predictor of LMX

quality and some of the dimensions of transformational

leadership.

Personal Wisdom and LMX Quality

We expect that leaders’ personal wisdom is positively

related to the LMX quality in their work group. Wisdom

researchers have argued that possessing high levels of

personal wisdom predisposes people to lead a meaningful

and virtuous life that is beneficial for themselves and others

(Ardelt 2004; Baltes and Staudinger 2000). LMX quality is

related to more relationship-oriented leadership behaviors

H. Zacher et al.

123

than other types of leadership (Mahsud et al. 2010; Yukl

et al. 2009). The quality of relationships between wise

leaders and their followers should thus be generally higher

than the quality of relationships between less wise leaders

and their followers. Wise people have a mature and inte-

grated personality, possess superior judgment skills with

regard to challenging life situations, and treat other people

in ways that demonstrate empathy and compassion (Ardelt

2004). Interacting with followers in the work context offers

wise leaders the possibility to translate their exceptional

interpersonal qualities into social practice, which is a cen-

tral element of social practice wisdom theory (McKenna

et al. 2009; Rooney and McKenna 2008; Rooney et al.

2010). This social practice of wisdom should help wise

leaders develop and maintain high-quality relationships

with their followers that are characterized by high loyalty,

respect, and trust.

Hypothesis 1 Leaders’ personal wisdom is positively

related to LMX quality.

Personal Wisdom and Transformational Leadership

Dimensions

We also expect that personal wisdom is positively related

to the intellectual stimulation and individualized consid-

eration dimensions of transformational leadership. Wise

leaders possess superior knowledge, understanding, and

acceptance of life and human nature, as well as a perma-

nent need to gain a better understanding of themselves,

their relationships with others, and their environment

(cognitive wisdom; Ardelt 2004). They also have great

capacities for self-insight, self-examination, and perspec-

tive taking (reflective wisdom; Ardelt 2004). These wis-

dom characteristics should enable and motivate wise

leaders to interact in intellectually stimulating ways with

their followers, including the encouragement of indepen-

dent and creative thinking (Sternberg 2001, 2008). Fur-

thermore, wise leaders have a genuine concern for others

which is fueled by empathetic and compassionate love

(affective wisdom; Ardelt 2004). This wisdom character-

istic should trigger behaviors among wise leaders that

demonstrate individualized care and consideration for their

followers, such as providing meaningful advice and

developmental opportunities at work. Due to their high

levels of understanding, reflection, and unconditional

sympathy for others, wise leaders should also be capable of

providing their followers with informational and emotional

support when they cope with changes and challenges in

their lives. Consistent with these arguments, Sternberg’s

(1998, 2003, 2007) balance theory of wisdom suggests that

wise leaders make use of their high levels of cognitive

complexity, reflection, creativity, and expertise to always

balance their own with their followers’ interests.

While we propose positive associations between per-

sonal wisdom on the one hand and intellectual stimulation

and individualized consideration on the other, we do not

expect that personal wisdom predicts the charismatic

transformational leadership dimensions of idealized influ-

ence and inspirational motivation. Due to their reflective,

modest, and other-oriented nature (Kunzmann and Baltes

2003), wise leaders are not likely to be motivated to enact

idealized influence on their followers and to perceive

themselves as incomparable role models for others. In fact,

they may even discourage uncritical admiration by fol-

lowers and actively avoid engaging in charismatic behav-

iors such as trying to convince others of their personal

values, beliefs, and visions. Indeed, the most basic Bud-

dhist teachings (Dharma) are clear that wise leaders should

encourage followers to be independent critical thinkers and

to place critical thinking above faith (The Dalai Lama

2005). On the other hand, it may be possible that followers

attribute charisma to wise leaders as was the case for his-

torical leaders such as Jesus, the Buddha, and Muhammad

(Ardelt 2004). As charisma is based on both actual leader

behaviors as well as follower attributions (Schyns et al.

2007; Shamir et al. 1993) and, therefore, should have

contradictory associations with leaders’ personal wisdom,

we do not expect links between leaders’ personal wisdom

and idealized influence and inspirational motivation.

Hypothesis 2a Leaders’ personal wisdom is positively

related to intellectual stimulation.

Hypothesis 2b Leaders’ personal wisdom is positively

related to individualized consideration.

Intellectual Stimulation and Individualized

Consideration as Mediators of the Relationship

Between Personal Wisdom and LMX Quality

Finally, we propose that intellectual stimulation and indi-

vidualized consideration mediate the positive relationship

between leaders’ personal wisdom and LMX quality. In other

words, wise leaders should have higher quality LMX rela-

tionships with their followers because their personal wisdom

enables and motivates their engagement in other-oriented,

compassionate behaviors such as encouraging followers to

think in independent and creative ways, and by being con-

siderate and supportive of followers’ personal development.

Intellectual stimulation and individualized consideration, in

turn, should positively predict LMX quality. The latter

assumption is consistent with previous research which has

hypothesized and found that transformational leadership

behaviors influence LMX quality (Wang et al. 2005).

Leaders’ Personal Wisdom and Leader–Member Exchange Quality

123

Hypothesis 3a Intellectual stimulation mediates the

relationship between leaders’ personal wisdom and LMX

quality.

Hypothesis 3b Individualized consideration mediates the

relationship between leaders’ personal wisdom and LMX

quality.

The Role of Big Five Personality Traits, Emotional

Intelligence, and Narcissism

When examining relationships among personal wisdom,

LMX quality, and transformational leadership dimensions,

it is important to control for additional individual differ-

ence characteristics that may explain potential associations

between these constructs. In this study, we control for the

Big Five personality characteristics, emotional intelligence,

and narcissism. First, research has shown that some of the

Big Five personality characteristics (extraversion, agree-

ableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to

experience; Digman 1990) predict leadership behaviors

(Bono and Judge 2004; Judge et al. 2002). Similarly, Ardelt

(2004) argued that personal wisdom should be related to

the Big Five personality characteristics agreeableness and

neuroticism. Empirical studies showed that wisdom was

related to openness to experience and extraversion (Mic-

kler and Staudinger 2008; Staudinger et al. 1998). Thus, we

controlled for the Big Five personality characteristics as

they might confound the relationships between personal

wisdom and leadership constructs.

Second, we controlled for emotional intelligence—the

ability to recognize and regulate emotions in oneself and

others (Law et al. 2004; Wong and Law 2002). Emotional

intelligence has been shown to be related to leadership

behavior (Barling et al. 2000; Greaves et al. 2013; Mandell

and Pherwani 2003). Research has also shown that personal

wisdom is positively related to emotional intelligence

(Zacher et al. 2013) and to characteristics similar to emo-

tional intelligence, such as affective modulation and com-

plexity as well as a preference for cooperative compared to

submissive, avoidant, and dominant conflict management

styles (Kunzmann and Baltes 2003). Thus, we control for

emotional intelligence as a potential third-variable expla-

nation for relationships between personal wisdom and

leadership constructs.

Finally, narcissism refers to an inflated sense of self-

importance which is usually not supported by actual talents

or accomplishments (American Psychiatric Association

2000). Wisdom researchers reported that wise people

focused more strongly on other-enhancing values than less

wise people (Kunzmann and Baltes 2003), whereas nar-

cissists are more concerned with themselves than with

others. In addition, leadership researchers have suggested

relationships between narcissism and transformational

leadership (Judge et al. 2006). On the one hand, narcissists

may be perceived as better leaders because they strive to

gain others’ admiration and, to this end, provide their fol-

lowers with short-term benefits (Robins and Beer 2001).

On the other hand, narcissistic leaders may be unpopular

with their followers because they lack empathy and dam-

age interpersonal relationships in the long run (Judge et al.

2006). Thus, we control for narcissism in this study to rule

out another potential third-variable explanation for rela-

tionships between personal wisdom and follower-oriented

forms of leadership.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Data for this study came from 75 religious leaders and 158

of these leaders’ employees in Australia. Sixty-four

(85.3 %) leaders were male and 11 (14.7 %) leaders were

female. This gender distribution is likely due to the pro-

fessional background of leaders in this study, with tradi-

tionally more men being trained to become religious

leaders than women. The age distribution ranged from 38

to 80 years, and the average age was 58.08 years

(SD = 9.86). In terms of highest level of education

achieved, most participants held a postgraduate degree

(45; 60.4 %) or undergraduate degree (20; 26.7 %). The

remaining participants held a technical college degree

(2; 2.7 %), a high school degree (6; 8 %), or a primary

school degree (1; 1.3 %), and one participant did not

indicate the highest level of education achieved. The vast

majority of participants (68; 90.67 %) were leaders of

Christian organizations (e.g., pastors, priests), and only

seven participants (9.33 %) came from other religious

backgrounds (e.g., Hinduism and Judaism). Non-paramet-

ric tests indicated no differences in personal wisdom and

leadership variables between these different religious

groups. In terms of work experience, leaders had on

average served their current communities for 7.43 years

(SD = 7.25), they had on average 23.31 years of previous

work experience in their lives (SD = 13.12), and they had

on average served 4.14 communities (SD = 3.04) in their

working lives before joining their current community.

Sixty-six (41.77 %) followers were male and 87

(55.06 %) followers were female (five followers [3.16 %]

did not indicate their gender). Followers’ age distribution

ranged from 27 to 86 years, and the average age was

53.65 years (SD = 13.78). In terms of highest level of

education achieved, most followers held a postgraduate

H. Zacher et al.

123

degree (59; 37.34 %), undergraduate degree (37; 23.42 %),

or high school degree (34; 21.52 %). The remaining par-

ticipants held a technical college degree (19; 12.03 %) or a

primary school degree (2; 1.27 %), and seven participants

(4.43 %) did not indicate the highest level of education

achieved. In terms of work experience, followers had on

average 30.63 years of previous work experience in their

lives (SD = 15.15), and had worked on average for

7.32 years (SD = 7.57) in their current jobs and for

4.99 years (SD = 4.97) with their current leader.

To start the study, 600 letters and questionnaire pack-

ages were mailed to religious organizations throughout

Australia, which were listed in publicly available online

databases. Religious leaders were asked to participate in a

study on leadership by completing a leader questionnaire

themselves and by distributing three questionnaires to three

of their employees who had the possibility to observe the

leaders’ behavior at work. Leaders were asked to write a

personal code on their own and their employees’ ques-

tionnaires to allow for anonymous matching of the

responses by the researchers. All questionnaires were

returned anonymously and separately to the authors. Forty-

eight letters were returned unopened because the organi-

zations had changed addresses. Eighty-nine leaders

returned their completed questionnaires for a response rate

of 16.12 %. For 75 of the 89 leaders who had returned

questionnaires, follower ratings (N = 158; an average of

2.11 follower ratings per leader) were returned. Three

follower ratings were available for 27 leaders (36.0 %),

two follower ratings were available for 29 leaders

(38.7 %), and only one follower rating was available for 19

leaders (25.3 %). Written responses by some of the leaders

indicated that having fewer than three employees in their

organizations was a common reason for not more than one

or two employees returning a questionnaire. One-way

analyses of variance indicated that there were no significant

differences among these three groups (i.e., one, two, or

three followers) in personal wisdom, LMX quality, and

transformational leadership dimensions.

Measures

Personal Wisdom

Personal wisdom was measured using leaders’ ratings on

Ardelt’s (2003) 39-item personal wisdom scale. The scale

assesses three fundamental components of personal wis-

dom. The 14 cognitive wisdom items (Cronbach’s

alpha = 0.71) assess people’s ability and motivation to

understand events thoroughly, their knowledge of the

positive and negative aspects of human nature, and their

awareness and management of uncertainty in life (example

items: ‘‘Ignorance is bliss,’’ ‘‘People are either good or

bad,’’ ‘‘I am hesitant about making important decisions

after thinking about them,’’ and ‘‘I prefer just to let things

happen rather than try to understand why they turned out

that way’’ [all items reverse coded]). The 12 reflective

wisdom items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78) measure the

ability and motivation to examine events from multiple

perspectives, and the absence of subjectivity and projec-

tions in judgments (e.g., ‘‘When I am confused by a

problem, one of the first things I do is survey the situation

and consider all the relevant pieces of information,’’

‘‘When I’m upset at someone, I usually try to ‘put myself

in his or her shoes’ for a while,’’ ‘‘I always try to look at all

sides of a problem,’’ and ‘‘I try to look at everybody’s side

of a disagreement before I make a decision’’). Finally, the

13 affective wisdom items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.63)

assess positive feelings and behaviors toward others, and

the absence of indifferent or negative emotions and

behaviors toward others (e.g., ‘‘I can be comfortable with

all kinds of people,’’ ‘‘Sometimes I feel real compassion for

everyone,’’ and ‘‘If I see people in need, I try to help them

one way or another’’). Leaders provided their ratings on

5-point scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5

(strongly agree) and from 1 (not true of myself) to 5 (very

true of myself). Consistent with her theory on personal

wisdom as the integration of advanced cognitive, reflective,

and affective characteristics, Ardelt (2003) suggested that

researchers should average the scores on the three wisdom

dimensions to compute an overall personal wisdom score.

Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.81.

To develop her personal wisdom scale, Ardelt (2003)

initially selected 132 potential wisdom items primarily

from existing scales that measure the cognitive, reflective,

and affective components of wisdom. She subsequently

administered these items to 180 participants to examine

the reliability and validity of the scale. Items were dis-

carded if their range was smaller than 4 on the 5-point

scales, had a high skewness or kurtosis ([2) or a small

variance (\0.50), were at least moderately correlated with

a social desirability scale (r [ 0.30), or had low or neg-

ative intercorrelations with the other items. Ardelt (2003)

demonstrated that her scale is a reliable and valid measure

of a latent, personality-based wisdom construct. For

example, in terms of predictive validity, the scale was

positively related to well-being, mastery, a sense of pur-

pose in life, and subjective health, and negatively related

to depressive symptoms, feelings of economic pressure,

death avoidance, and fear of death (Ardelt 2003). With

regard to convergent and discriminant validity, partici-

pants who scored highly on the wisdom scale were also

more likely to be nominated as wise by other participants,

and wisdom was unrelated to participants’ finances, mar-

ital and retirement status, gender, race, and social desir-

ability (Ardelt 2003).

Leaders’ Personal Wisdom and Leader–Member Exchange Quality

123

LMX Quality

LMX quality was measured using follower ratings on the

widely used 12-item LMX scale developed and validated

by Liden and Maslyn (1998). The scale assesses the four

LMX dimensions affect, loyalty, professional respect, and

contribution. Example items are ‘‘I like my supervisor very

much as a person,’’ ‘‘I respect my supervisor’s knowledge

of and competence on his/her job,’’ and ‘‘My supervisor

would come to my defense if I were ‘attacked’ by others.’’

The items were answered on 7-point scales ranging from 1

(strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). As suggested by

Liden and Maslyn (1998), we averaged the ratings across

the 12 items to derive a global measure of LMX. Cron-

bach’s alpha of the scale, as assessed by the first follower

of each leader, was 0.89.

Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership dimensions were assessed

using followers’ ratings on all of the 20 transformational

leadership items from the widely used multifactor leader-

ship questionnaire (MLQ Form 5X-Short, Avolio and Bass

1995).1 The four transformational leadership dimensions

are idealized influence (8 items; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89),

inspirational motivation (8 items; Cronbach’s alpha =

0.91), individualized consideration (4 items; Cronbach’s

alpha = 0.87), and intellectual stimulation (4 items,

Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76). The items were answered on

5-point scales ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (frequently, if

not always) (note that the MLQ in original uses a scale

from 0 to 4).

Control and Demographic Variables

The Big Five personality characteristics were self-rated by

leaders using all items from the widely used, reliable, and

well-validated 44-item Big Five Inventory (John et al.

1991). Answers were provided on 5-point scales ranging

from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Example

items and Cronbach’s alphas of the scales are ‘‘I see myself

as someone who…is talkative’’ (extraversion; a = 0.85),

‘‘… tends to find fault with others’’ (reverse coded;

agreeableness; a = 0.65), ‘‘…does a thorough job’’ (con-

scientiousness; a = 0.85), ‘‘…is depressed, blue’’ (neu-

roticism; a = 0.82), and ‘‘…is original, comes up with new

ideas’’ (openness to experience; a = 0.82).

Emotional intelligence was self-rated by leaders using

Wong and Law’s (2002; see also Law et al. 2004) 16-item

scale. This reliable and valid scale assesses the appraisal of

one’s own and others emotions as well as regulation of

emotion. Answers were provided on 7-point scales ranging

from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Example

items are ‘‘I have a good sense of why I have certain

feelings most of the time,’’ ‘‘I always know my friends

emotions from their behavior,’’ ‘‘I always set goals for

myself and then try my best to achieve them,’’ and ‘‘I am

able to control my temper and handle difficulties ratio-

nally.’’ Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.83.

Narcisissm was self-rated by leaders using a short,

reliable, and valid 16-item version of the Narcissistic

Personality Inventory (Ames et al. 2006). The measure has

a dichotomous answer format; participants are asked to

indicate their preference for a narcissistic response (coded

as 1) or a non-narcissistic response (coded as 0). Example

statements are ‘‘I know that I am good because everybody

keeps telling me so’’ (narcissistic response) versus ‘‘When

people compliment me I sometimes get embarrassed’’

(non-narcissistic response). Cronbach’s alpha of the mea-

sure was 0.73.

Finally, leaders and followers reported their age, gender,

highest level of education, work experience variables, and

religious affiliation. None of these demographic variables

were related to personal wisdom, LMX quality, and

transformational leadership dimensions, and, therefore, we

did not control for them in the analyses to preserve sta-

tistical power (Becker 2005).

Results

The descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations of the

variables are shown in Table 1. On a bivariate level, per-

sonal wisdom was significantly correlated with agreeable-

ness (r = 0.32, p \ 0.01), neuroticism (r = -0.27,

p \ 0.05), emotional intelligence (r = 0.51, p \ 0.01),

inspirational motivation (r = 0.26, p \ 0.05), intellectual

stimulation (r = 0.24, p \ 0.05), and LMX quality

(r = 0.31, p \ 0.01). LMX quality was significantly cor-

related with neuroticism (r = -0.27, p \ 0.05) and the

four transformational leadership dimensions (rs ranged

between 0.50 and 0.76, p \ 0.01).

According to Hypothesis 1, leaders’ personal wisdom is

positively related to LMX quality. Table 2 shows the

results of a multiple regression analysis used to test whe-

ther personal wisdom predicted LMX quality above and

beyond the Big Five personality traits, emotional intelli-

gence, and narcissism. The control variables explained a

significant share of the variance in LMX quality when

entered in the first step (R2 = 0.22, p \ 0.05). Personal

1 The Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire, Form 5X-Short (copy-

right 2004 by Bruce Avolio and Bernard Bass) is used with the

permission of Mind Garden, 855 Oak Grove Ave., Menlo Park, CA

94025. All rights reserved.

H. Zacher et al.

123

wisdom positively predicted LMX quality above and

beyond the control variables when entered in the second

step (b = 0.30, DR2 = 0.06, p \ 0.05), supporting

Hypothesis 1.

According to Hypotheses 2a and 2b, leaders’ personal

wisdom is positively related to intellectual stimulation and

individualized consideration, respectively. Table 3 shows

the results of four multiple regression analyses used to test

whether personal wisdom predicted the four transforma-

tional leadership dimensions above and beyond the Big

Five personality traits, emotional intelligence, and narcis-

sism. As shown in Table 3, personal wisdom did not sig-

nificantly predict intellectual stimulation above and beyond

the control variables (b = 0.26, DR2 = 0.05, not signifi-

cant [ns]). Therefore, Hypothesis 2a was not supported. In

support of Hypothesis 2b, personal wisdom positively and

significantly predicted individualized consideration above

and beyond the control variables (b = 0.27, DR2 = 0.05,

p \ 0.05). Personal wisdom did not significantly predict

idealized influence (b = 0.13, DR2 = 0.01, ns) and inspi-

rational motivation (b = 0.24, DR2 = 0.04, ns).

Finally, Hypotheses 3a and 3b state that intellectual

stimulation and individualized consideration, respectively,

mediate the relationship between leaders’ personal wisdom

and LMX quality. To test these hypotheses, we entered the

transformational leadership dimensions in a regressionTa

ble

1M

ean

s(M

),st

and

ard

dev

iati

on

s(S

D),

and

corr

elat

ion

so

fv

aria

ble

s

Var

iab

leM

SD

12

34

56

78

91

01

11

21

3

1.

Per

son

alw

isd

om

3.9

30

.31

(0.8

1)

2.

Ex

trav

ersi

on

3.2

10

.68

0.1

7(0

.85

)

3.

Ag

reea

ble

nes

s3

.97

0.4

00

.32

**

0.2

1(0

.65

)

4.

Co

nsc

ien

tio

usn

ess

3.8

60

.57

0.2

10

.30

**

0.4

6*

*(0

.85

)

5.

Neu

roti

cism

2.5

40

.60

-0

.27

*-

0.1

5-

0.4

7*

*-

0.3

3*

*(0

.82

)

6.

Op

enn

ess

toex

per

ien

ce3

.62

0.5

40

.15

0.1

4-

0.1

80

.05

-0

.00

(0.8

2)

7.

Em

oti

on

alin

tell

igen

ce5

.42

0.4

80

.51

**

0.3

8*

*0

.48

**

0.3

5*

*-

0.3

0*

*0

.16

(0.8

3)

8.

Nar

ciss

ism

0.1

80

.16

-0

.05

0.4

1*

*-

0.0

70

.05

0.1

00

.33

**

0.0

9(0

.73

)

9.

Idea

lize

din

flu

ence

4.3

70

.46

0.1

80

.11

0.2

20

.07

-0

.25

*-

0.1

30

.22

0.2

1(0

.89

)a

10

.In

spir

atio

nal

mo

tiv

atio

n4

.02

0.6

60

.26

*0

.24

*0

.09

0.1

3-

0.1

0-

0.0

80

.28

*0

.25

*0

.65

**

(0.9

1)a

11

.In

tell

ectu

alst

imu

lati

on

3.8

00

.72

0.2

4*

-0

.00

0.1

30

.02

-0

.25

*-

0.1

40

.14

0.0

70

.71

**

0.6

3*

*(0

.87

)a

12

.In

div

idu

aliz

edco

nsi

der

atio

n4

.19

0.5

50

.22

-0

.04

0.1

1-

0.1

4-

0.0

7-

0.1

50

.11

0.1

50

.74

**

0.5

3*

*0

.66

**

(0.7

6)a

13

.L

ead

er–

mem

ber

exch

ang

e6

.04

0.5

30

.31

**

0.0

30

.22

0.0

1-

0.2

7*

-0

.08

0.2

20

.20

0.7

6*

*0

.50

**

0.5

8*

*0

.72

**

(0.8

9)a

N=

75

.V

aria

ble

s1

–8

wer

era

ted

by

lead

ers

and

var

iab

les

9–

13

wer

era

ted

by

foll

ow

ers.

Rel

iab

ilit

yes

tim

ates

(a)

are

sho

wn

inp

aren

thes

esal

on

gth

ed

iag

on

al

*p

\0

.05

;*

*p\

0.0

1a

Rel

iab

ilit

yes

tim

ates

are

bas

edo

nra

tin

gs

of

the

firs

tfo

llo

wer

Table 2 Results of regression analysis predicting leader–member

exchange quality

Variable Leader–member exchange quality

Step 1 Step 2 Step 3

Step 1

Extraversion -0.19 -0.19 -0.10

Agreeableness 0.08 0.05 0.00

Conscientiousness -0.14 -0.14 -0.03

Neuroticism -0.28* -0.26* -0.13

Openness to experience -0.18 -0.23 -0.03

Emotional intelligence 0.22 0.09 0.01

Narcissism 0.36** 0.40** 0.13

Step 2

Personal wisdom 0.30* 0.16

Step 3

Idealized influence 0.49**

Inspirational motivation -0.03

Intellectual stimulation -0.05

Individualized consideration 0.33**

DR2 0.06* 0.40**

R2 0.22 0.29 0.68

F 2.76* 3.28** 10.96**

N = 75. Standardized regression coefficients (b) are reported

* p \ 0.05; ** p \ 0.01

Leaders’ Personal Wisdom and Leader–Member Exchange Quality

123

analysis predicting LMX quality, after the control variables

and personal wisdom were entered in the first two steps

(Table 2). As shown in Table 2, idealized influence

(b = 0.49, p \ 0.01) and individualized consideration

(b = 0.33, p \ 0.01) positively and significantly predicted

LMX quality above and beyond the control variables and

personal wisdom, whereas inspirational motivation (b =

-0.03, ns) and intellectual consideration (b = -0.05, ns)

did not have significant effects. The positive and significant

effect of personal wisdom on LMX quality became weaker

and non-significant when the transformational leadership

dimensions were entered in the regression equation

(Table 2, Step 3; b = 0.16, ns).

Hypothesis 3a was not supported because both the path

from personal wisdom to intellectual stimulation and the

path from intellectual consideration to LMX quality were

not significant. We used an SPSS macro provided by

Hayes (2012) to test the significance of the indirect

(mediated) effects using the recommended bootstrapping

approach (MacKinnon et al. 2007). The results of these

analyses are displayed in Table 4. The indirect effect of

leaders’ personal wisdom on LMX quality through indi-

vidualized consideration was significant as the boot-

strapped confidence interval (CI) did not include zero

(indirect effect = 0.09, SE = 0.06, lower 95 %

CI = 0.01, upper 95 % CI = 0.29). This result supports

Hypothesis 3b. In contrast, the indirect effects of personal

wisdom on LMX quality through idealized influence,

inspirational motivation, and intellectual stimulation were

not significant.

Additional Analyses

Ardelt (2004) recommended investigating personal wisdom

as an integrated, higher order characteristic. Similarly,

researchers have suggested that LMX quality can be investi-

gated as a single higher order factor (Liden and Maslyn 1998).

It may be interesting, however, to also examine and report the

relationships among the separate dimensions of personal

wisdom and LMX quality. The dimensions of personal wis-

dom were moderately intercorrelated (cognitive and reflective

wisdom, r = 0.28, p \ 0.05; cognitive and affective wisdom,

0.17, ns; reflective and affective wisdom, 0.53, p \ 0.01). The

cognitive wisdom dimensions were marginally significantly

correlated with LMX quality (r = 0.22, p = 0.064), whereas

Table 3 Results of regression analyses predicting transformational leadership dimensions

Variable Idealized influence Inspirational motivation Intellectual stimulation Individualized consideration

Step 1 Step 2 Step 1 Step 2 Step 1 Step 2 Step 1 Step 2

Step 1

Extraversion -0.09 -0.09 0.05 0.04 -0.13 -0.13 -0.17 -0.18

Agreeableness 0.05 0.04 -0.15 -0.17 -0.04 -0.07 0.10 0.08

Conscientiousness -0.08 -0.07 0.05 0.06 -0.07 -0.07 -0.24 -0.23

Neuroticism -0.25 -0.24 -0.09 -0.07 -0.29* -0.27* -0.10 -0.08

Openness to experience -0.25* -0.27* -0.25* -0.29* -0.22 -0.26* -0.22 -0.26*

Emotional intelligence 0.18 0.13 0.30* 0.20 -0.16 0.05 0.19 0.07

Narcissism 0.34** 0.36** 0.28* 0.31* 0.21 0.24 0.30* 0.34*

Step 2

Personal wisdom 0.13 0.24 0.26 0.27*

DR2 0.01 0.04 0.05 0.05*

R2 0.20 0.22 0.19 0.22 0.13 0.18 0.16 0.21

F 2.45* 2.27* 2.18* 2.38* 1.45 1.78 1.79 2.19*

N = 75. Standardized regression coefficients (b) are reported

* p \ 0.05; ** p \ 0.01

Table 4 Indirect effects of personal wisdom on leader–member

exchange quality through transformational leadership dimensions

Mediator Indirect

effect

Boot

SE

Boot LL

CI

Boot UL

CI

Idealized influence 0.06 0.07 -0.04 0.24

Inspirational

motivation

-0.01 0.03 -0.10 0.04

Intellectual

stimulation

-0.01 0.03 -0.11 0.03

Individualized

consideration

0.09 0.06 0.01 0.29

Number of bootstrap samples for bias corrected bootstrap inter-

val = 5,000. Level of confidence for all confidence intervals = 95 %

SE standard error, LL lower level, CI confidence interval, UL upper

level

H. Zacher et al.

123

the reflective and affective wisdom dimensions were signifi-

cantly related to LMX quality (r = 0.25 and 0.23, respec-

tively, ps \ 0.05). When the three wisdom dimensions were

entered simultaneously into a regression analysis predicting

LMX quality, they did not have significant effects beyond the

control variables.

Correlations between the LMX quality dimensions ran-

ged from r = 0.34 to 0.77 (ps \ 0.01). The personal wis-

dom composite was significantly correlated with the LMX

quality dimensions of affect (r = 0.27, p \ 0.05), loyalty

(r = 0.24, p \ 0.05), professional respect (r = 0.25,

p \ 0.05), and marginally significantly correlated with

contribution (r = 0.22, p = 0.055). Regression analyses

showed that personal wisdom had marginally significant

effects above and beyond the control variables on contri-

bution (b = 0.26, p \ 0.10) and professional respect

(b = 0.26, p \ 0.10) and no significant effects on affect

(b = 0.22, ns) and loyalty (b = 0.20, ns).

The relationship between personal wisdom and leader-

ship may also be curvilinear. For example, an intermediate

level of personal wisdom may be more beneficial for LMX

quality and the transformational leadership dimensions,

whereas low and high levels of personal wisdom may lead

to leaders being too removed from their followers and their

daily experiences. We checked for this possibility and

found no curvilinear effects of wisdom on LMX quality

and transformational leadership dimensions. Specifically,

the quadratic wisdom term did not significantly predict

follower ratings of LMX quality and transformational

leadership dimensions above and beyond the first-order

effects of wisdom.

Discussion

Lifespan and leadership researchers have recently called

for increased research on the relation between wisdom and

leadership (Mumford 2011; Staudinger and Gluck 2011).

The goal of this study was to contribute to this emerging

literature by examining relationships among personal wis-

dom, LMX quality, and dimensions of transformational

leadership. Consistent with expectations based on wisdom

theories (Ardelt 2004; Baltes and Staudinger 2000; Stern-

berg 1998) and theoretical accounts of the potential link

between wisdom and leadership in the business literature

(Bigelow 1992; Jones 2005; McKenna et al. 2009; Nonaka

and Takeuchi 2011; Yang 2008a), leaders’ personal wis-

dom was positively related to LMX quality (Hypothesis 1),

even after controlling for Big Five personality character-

istics, emotional intelligence, and narcissism. In addition,

leaders’ personal wisdom positively predicted the trans-

formational leadership dimension individualized consider-

ation (Hypothesis 2b), and individualized consideration

mediated the relationship between leaders’ personal wis-

dom and LMX quality (Hypothesis 3b). Thus, wise leaders

appear to engage in more supportive behaviors than less

wise leaders which, in turn, lead to a higher quality of the

leader–follower relationship. These findings extend recent

research by Yang (2011) and Greaves et al. (2013) by

investigating personal wisdom as an individual difference

characteristic of leaders and linking it to different dimen-

sions of transformational leadership and LMX quality. Our

results provide support for recent propositions by business

scholars that leaders’ personal wisdom constitutes a unique

factor that explains variation in leadership behaviors (Kil-

burg 2006; McKenna et al. 2009; Nonaka and Takeuchi

2011). In particular, personal wisdom appears to be mainly

relevant with regard to follower-centered behaviors (i.e.,

individualized consideration).

We did not find support for the hypothesized mediating

role of the transformational leadership dimension intel-

lectual stimulation in the relationship between leaders’

personal wisdom and LMX quality. While the effect of

personal wisdom on intellectual stimulation was in the

expected direction and approached conventional levels of

statistical significance, intellectual stimulation did not

predict LMX quality. Despite the finding that leaders’

intellectual stimulation is not an important predictor of

LMX quality, it is possible that intellectual stimulation

benefits followers in other ways. For example, intellectual

stimulation may encourage critical thinking among fol-

lowers, which could result in a desirable organizational

culture that allows for independence and constructive dis-

sent (Tourish and Pinnington 2002; Tourish and Vatcha

2005). Furthermore, consistent with expectations based on

wisdom theories, leaders’ personal wisdom did not signif-

icantly predict the two charismatic dimensions of trans-

formational leadership, idealized influence, and

inspirational motivation. These results are in line with

previous research showing that leader’s ethical preferences

are unrelated to charismatic leadership (Banerji and

Krishnan 2000) and they suggest that wise leaders do not

necessarily desire to be seen as charismatic heroes and

inspirational role models (Staudinger and Gluck 2011). In

addition, the followers of wise leaders may not inevitably

attribute an exceptional quality to their leaders or respond

uncritically to their influence. Overall, our findings of

differential relationships between leaders’ personal wisdom

and dimensions of transformational leadership are consis-

tent with a more critical and balanced perspective on

transformational leadership (Fairhurst 2007; Tourish 2008),

they extend previous empirical research in this area

(Greaves et al. 2013), and, for the first time, they address

wisdom researchers’ concerns regarding an expectation of

generally positive links between wisdom and transforma-

tional leadership (Staudinger and Gluck 2011).

Leaders’ Personal Wisdom and Leader–Member Exchange Quality

123

In the context of a discussion of differential effects of

personal wisdom, it is also important to note that personal

wisdom, despite its enthusiastic endorsement by the posi-

tive psychology movement (Peterson and Seligman 2004;

Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000), does not generally

imply only positive experiences and life outcomes. In

contrast, wise people usually have faced difficult decisions

and experienced many challenges in their lives (Biloslavo

and McKenna 2013; Webster 2007), and they are able to

integrate both positive and negative aspects of life and

human nature (Ardelt 2004). This balanced perspective on

personal wisdom is consistent with recent criticisms of

positive psychology as overly simplistic (Gable and Haidt

2005; Grant and Schwartz 2011; McNulty and Fincham

2012) as well as the empirical finding that wise people may

be better in dealing with negative experiences than

increasing their positive experiences and personal satis-

faction (Zacher et al. 2013). One must also keep in mind

that mindfulness, which has been adopted by positive

psychology, is an ancient aspect of Buddhism and a pri-

mary element of wisdom development in that tradition. In

Buddhism, mindfulness practices are applied by an indi-

vidual to overcome cognitive and affective distortions

linked to negative life experiences to create psychological

equanimity for wise judgment and behaviors (Karr 2007).

Additional results from our study are also consistent

with a critical approach to transformational leadership

(Amernic et al. 2007; Fairhurst 2007; Tourish 2008). First,

we found that the control variable narcissism positively

predicted not only the charismatic leadership dimensions,

idealized influence, and inspirational motivation but also

individualized consideration and LMX quality. While the

positive links between narcissism and charismatic leader-

ship behaviors may be explained by narcissistic leaders’

desire to enact idealized influence on their followers and to

transmit their personal vision to them, an explanation for

the latter findings is less straightforward. It may be possible

that followers in this study worked more independently

than followers in other organizational settings, and, there-

fore, were not exposed to the potentially harmful long-term

effects of leaders’ narcissism. Another potential explana-

tion is that religious followers may have some level of

reverence for religious leaders that differs from other lea-

der–follower constellations. Support for the possibility that

the positive relationship between leaders’ narcissism and

follower ratings of leadership may be due to the specific

nature of our sample of religious leaders comes from a

number of studies that have demonstrated negative rela-

tionships between narcissism and overall transformational

leadership in samples of leaders in business and education

(Greaves et al. 2013; Khoo and Burch 2008; Resick et al.

2009). It may also be possible that the followers in our

study benefited from narcissistic leaders’ tendency to

generate short-term positive affect (Robins and Beer 2001)

which, in turn, may have resulted in increased perceptions

of leaders’ individualized consideration and LMX quality.

However, followers’ naive sympathy and admiration for a

narcissistic leader may lead to problematic and even

disastrous consequences due to blind obedience, manipu-

lation, and dependency of followers (Allix 2000; Conger

1990). In fact, narcissistic charismatic leaders, despite their

initial appeal, in the long term may turn out to be what

Boddy, Hare and colleagues have called ‘‘corporate psy-

chopaths’’ (Babiak and Hare 2007; Boddy 2011; Boddy

et al. 2010).

Our findings suggest that leaders’ personal wisdom may

offset the potentially harmful effects of narcissistic trans-

formational leaders by increasing leaders’ individualized

consideration for their followers and high LMX quality.

Carlson and Perrewe (1995) proposed that transformational

leaders, if they possess a strong ethical orientation and

consider their followers’ individual needs, may even con-

tribute to the institutionalization of an ethical culture in

their organizations. Similarly, research on the difference

between transformational and servant leadership has sug-

gested that while transformational leaders are mainly

interested in the achievement of organizational goals, ser-

vant leaders focus on their followers’ goal achievement

(Stone et al. 2004). In this sense, our findings on the links

between leaders’ personal wisdom and the interpersonal

constructs of individualized consideration and LMX qual-

ity may be even more relevant to the literature on follower-

oriented servant leadership (Greenleaf 1977; Van Diere-

ndonck 2011; Whetstone 2001) than to the literature on the

effects of transformational leadership on organizational

goal achievement and productivity. Future research could

also investigate whether and why some wise leaders, in

particular circumstances, may not interact in considerate

and meaningful ways with their followers. For example, it

is possible to conceive of a wise leader who decides to

withdraw from a religious organization or a group of fol-

lowers in part or completely because of lifespan contextual

changes in his or her personal morals and worldview that

may not be consistent with the organization’s values.

Limitations and Future Research

This study has a number of limitations that may constrain

the internal and external validity of its findings. First, the

findings are based on a relatively small and specialized

sample of 75 leaders and 158 of their followers working in

religious organizations. This may be criticized because the

ratio between predictor variables in the regression analyses

and participants was relatively small. However, relation-

ships between personal wisdom and leadership variables

emerged both in the correlation and in the regression

H. Zacher et al.

123

analyses, and also when the control variables were exclu-

ded from the regression analyses. In addition, the response

rate was very low in this study and we were not able to

assess potential response biases. For example, leaders with

lower levels of personal wisdom and lower levels of LMX

quality and transformational leadership behaviors may

have decided against participation. Consistent with this

possibility, the mean values of these variables were rela-

tively high and the standard deviations were relatively low

in this study. Low response rates are common in studies

with organizational leaders (Baruch and Holtom 2008), and

this study additionally asked for both leader and follower

ratings in an unsolicited mail-out. Future research should

aim for larger sample sizes and for the inclusion of a

broader range of responses. Related to the small sample

size, the number of follower ratings for each leader was

also relatively small in this study, and followers were

chosen by the leaders themselves. It may be possible that

some followers decided against participation in this study

because they disagreed with their leaders about the inter-

pretation and usefulness of certain transformational lead-

ership behaviors. Future research should aim to sample

larger and more representative groups of followers to avoid

such biases and to assess inter-rater reliability. This

research could also examine whether personal wisdom is

more relevant for individual- versus group-focused forms

of leadership (Wang and Howell 2010). In this study, it was

assumed that leaders’ personal wisdom is positively related

to individual-focused forms of leadership such as individ-

ualized consideration and LMX quality.

Second, findings from a sample of religious leaders and

their followers may not generalize to other leader popula-

tions such as leaders in industry, education, or the military,

and we, therefore, caution to generalize our preliminary

findings beyond the setting of religious organizations.

Personal wisdom may be an important attribute of leaders

in religious organizations, as it emphasizes the human need

for spirituality, the importance of good judgment, and

compassion for other people. In other industries, for

example business or the military, relationships between

leaders’ personal wisdom and follower perceptions of

leadership may be attenuated by organizational constraints

and external factors such as the use of power in hierarchical

relationships, supportive team climates, and profit maxi-

mization goals (Limas and Hansson 2004; Staudinger and

Gluck 2011). In contrast, associations between leaders’

personal wisdom and other important forms of leadership,

for instance servant leadership (Greenleaf 1977; Van Di-

erendonck 2011) and spiritual leadership (Benefiel 2005;

Fry 2003; Fry and Cohen 2009; Fry and Slocum 2008;

Kriger and Seng 2005; Neal et al. 1999; Parameshwar

2005) may be even stronger in samples of religious leaders

and followers than the associations between personal

wisdom, individualized consideration, and LMX quality.

Overall, the role of the social and organizational contexts

for the association between leaders’ wisdom and follower

outcomes is an important area for future research. Simi-

larly, researchers could compare relationships between

personal wisdom and leadership in other cultural contexts.

For example, follower-centered leadership behaviors may

be a more common way to express personal wisdom in

Asian cultures, which place a higher value on collectivistic

goals and long-term outcomes.

Third, the cross-sectional design of this study does not

allow for causal inferences to be made. The findings of this

study indicate that personal wisdom and leadership con-

structs are related among religious leaders, but the direc-

tion of this relationship remains unknown. Future research

should examine longitudinal, including reciprocal, rela-

tionships between personal wisdom (Ardelt 2000) and

leadership constructs. For example, it may be possible that

interpersonally challenging experiences in the leadership

role predict leaders’ personal wisdom over time. Recent

research suggests that personal wisdom is malleable, and

may increase with experience over time (Grossmann et al.

2010; Kross and Grossmann 2012).

Fourth, this study used a self-report measure of personal

wisdom which may be problematic due to social desir-

ability and biased self-perceptions (Staudinger and Gluck

2011) as well as the potential confounding influence of

personality characteristics and emotional intelligence

(Zacher et al. 2013). For example, wise leaders’ ratings of

their own personal wisdom may be more accurate than the

ratings of less wise leaders, because wise people have

higher levels of self-insight and engage in more self-

examination. In addition, personal wisdom is a complex

and multifaceted construct that may be difficult to assess

using self-report questionnaire scales. A more objective

method of assessing personal wisdom has recently been

developed and validated (Mickler and Staudinger 2008).

This method uses participants’ recorded and transcribed

verbal responses to a difficult life problem, which are

evaluated by independent raters on different dimensions of

personal wisdom. It remains an important task for future

research to assess different measures of personal wisdom in

one study, and to determine their overlap.

Finally, we would like to acknowledge potential con-

cerns regarding our quantitative-empirical approach to

complex and contextually embedded concepts such as

wisdom and leadership, which may be an overly prescrip-

tive, technical, and reductive way to generate new knowl-

edge about these concepts.2 Indeed, our conceptual model

may be seen as overly formulaic and it may, together with

2 We thank an anonymous reviewer for thoughtful comments that

informed the issues raised in this paragraph.

Leaders’ Personal Wisdom and Leader–Member Exchange Quality

123

the survey methodology employed, restrict the contextually

embedded and ‘‘lived’’ understanding of wise people and

their interactions with other people in different context and

across time. Theoretical and qualitative-empirical approa-

ches to ‘‘social practice wisdom’’ may enrich our under-

standing of wisdom and wise people in everyday life

(Rooney and McKenna 2008; Rooney et al. 2010). In

addition, we would like to encourage researchers in this

area to routinely question the depiction of scientific prop-

ositions, including the assumptions of wisdom and lead-

ership theories that the current study’s hypotheses were

based on, as ‘‘factual’’ in nature (cf. Callon and Latour

1992; Latour and Woolgar 1986). Future research on per-

sonal wisdom and leadership should, therefore, also include

theory building designs such as grounded theory (Glaser

and Strauss 1967; Rooney and McKenna 2008).

Practical Implications and Conclusion

The preliminary nature of the current findings, the cross-

sectional design of the study, and the unique nature of the

sample mandate tentative recommendations for leadership

practice. Further research on personal wisdom and lead-

ership needs to accumulate beyond this initial study before

definite conclusions can be made. If positive effects of

personal wisdom on individualized consideration and LMX

quality truly existed, independent of other important per-

sonality characteristics, religious organizations could

incorporate elements of personal wisdom into leadership

development programs. Recent research by Kross and

Grossmann (2012) suggests that wise reasoning, attitudes,

and behavior can be increased by psychologically dis-

tancing oneself from difficult problems with meaningful

personal implications while thinking about these problems.

Training such wisdom qualities in leaders may benefit

LMX quality.

In conclusion, this study found that leaders’ personal

wisdom was positively related to individualized consider-

ation behavior and, in turn, to LMX quality in a sample of

religious leaders and their followers, even after controlling

for Big Five personality characteristics, emotional intelli-

gence, and narcissism. These findings extend recent theo-

retical work on wisdom and leadership in organizations

(McKenna et al. 2009; Nonaka and Takeuchi 2011) and

add to the growing body of empirical studies in this area

(Greaves et al. 2013; Limas and Hansson 2004; Yang

2011). They are also consistent with a growing interest in

wisdom in the field of psychology (Karelitz et al. 2010;

Staudinger and Gluck 2011). Further theoretical, qualita-

tive, quantitative, and mixed methods research is now

needed to further substantiate our understanding of how the

complex construct of personal wisdom, among other rele-

vant individual and contextual factors, could benefit

leadership processes and outcomes. The most promising

approach to this question, in our view, is to continue to

base hypotheses on different theories of wisdom and

leadership, to employ well-validated measures of personal

wisdom and leadership behaviors and outcomes, and to

control for potential alternative explanations in empirical

studies. This approach may also help integrate the various

theoretical approaches to wisdom and leadership that cur-

rently exist in the literature.

References

Alimo-Metcalfe, B., & Alban-Metcalfe, J. (2005). Leadership: Time