Tools for making good data visualizations: the art of charting

Landscapes and Charting in the Nineteenth Century Neapolitan-Austrian and English Cooperation in the...

-

Upload

accademiagalileiana -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

0

Transcript of Landscapes and Charting in the Nineteenth Century Neapolitan-Austrian and English Cooperation in the...

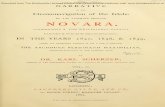

OFFPRINT

MAPPlE ANTIQUlE

Liber Amicorum Gunter Schilder

Vriendenboek ter gelegenheid van zijn 65ste verjaardag

Essays on the occasion of his 65th birthday

Festschrift zur Vollendung seines 65. Lebensjahres

Melanges offerts pour son 65ieme anniversaire

Edited by Pauia van Gestel-van het Schip and Peter van der Krogt

with the collaboration of

Marco van Egmond, Peter H. Meurer, Paul van den Brink and Edward H. Dahl

HES & DE GRAAF Publishers BY

Landscapes and Charting in the Nineteenth Century

Neapolitan-Austrian and English Cooperation in the Adriatic Sea

Vladimiro Valerio

Introduction

On a personal note ...

I first met Giinter in Italy in 1981, on the occasion of the International Conference on the History of Cartography. After that we met again at the following Conferences, which are well known for being an ideal place for meeting people. I knew of his work, always meticulously accurate and well documented and of his wide interests, but I really got to know Giinter during my study tour in Holland in February 2001, while I was carrying out research on cartography and city views of Naples during the Seventeenth Century. In the course of a pleasant week in Utrecht, not only was I able to appreciate again his kindness and readiness to share his intellectual resources, but I also discovered other delightfol traits of personality: behind his natural reserve emerged an energetic, fun-loving person with a ready smile. From that meeting grew the idea for a collaboration for the study of the contribution of the Dutch publishing industry to Seventeeenth Century depictions of the city of Naples, spurred on by Giinter and Peter van der Krogt, which remains, for me, one of the happiest and most successful experiments of scientific collaboration within my personal academic experience: a Neapolitan, Austrian and Dutch collaboration which immediately recalls to mind the mapping of the Adriatic carried out by Neapolitans, Austrians and Englishmen, outlined in the following paper.

The study of nautical cartography enjoys a well established historical tradition of long standing and, in many ways, the interest awakened by medieval nautical-cartographical monuments, and the pertinent pioneering studies, has led to a growth in research into the whole field of ancient and modern geo-cartography. The fundamental role played by research in and studies of nautical cartography within other fields of research such as, for example, history of exploration, of geographical knowledge and of linguistic and toponomastic variations, has been demonstrated over and over again in the course of the last century. Apart from the historical studies and analysis early developed within the 'nautical map' phenomenon, for reasons which were on occasion purely coincidental; it should be noticed that this extraordinary means of orientation and depiction of geographical space appeared somewhat earlier than the terrestrial equivalent. This peculiarity has led academics to investigate in particular, and with good reason, the golden age of such documents, which ran from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries. Preference was accorded to the manuscript artifacts associated with the study of 'cartographical monuments' , which were the subject of analysis by our early experts from the end of the nineteenth century to the second post war period. 2 Even though the study of 'terrestrial' cartography also concentrated on the discovery and the analysis of the earliest 'monuments' , later studies gradually shifted to the most recent outputs. Thus once and for all the concept of the geographical map being a prominent piece of art and science fell off, and maps were assigned the humbler, but certainly more incisive role of a 'document'-useful, along with many others, for understanding political and institutional evolution and consequently spatial modification of environment. It is unquestionable that nautical cartography, just like the geographical ones, are open to the latest historical analysis, such as those concerning, for example, changes to the environment and landscape; suffice it to think of the interpretation of coastlines, soundings, quite often accompanied by the quality of

Vladimiro Valerio Professor at the Insituto Universitario Architettura, University, Venice.

I

One recalls, for instance the pioneering study of A. E. Nordenskiold, Perip/us, (1897), which arose from his personal interest in travel and navigation.

2

For a bibliography of the studies carried out on the history of nautical charting, see Camp bell 1987; and the recent work by Corradino Astengo (2000).

I 465

MAPPJE ANTIQUJE

On this subject I would refer to my recent work entitled: Cartography, art and

mimesis: The imitation of nature in land

surveying in the eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries (Valerio 2005). The first account on this theme were published in 1987, see Valerio (I987).

4 Concerning Ptolemy and perspective, see Edgerton 1975, and, for a different apptoach, Valerio 1998.

5 See Valerio 2003.

6

Numerous studies have been published recently on topics relating to the history of cartography and there is a considerable bibliography. For a general overview of the subjects covered, I would refer to the delightful essay of Matthew H. Edney, The Origins and Development of]. B.

Harleys Cartographic Theories (2005).

7 See Harley 1975, pp. 3 et seq.and p. 49; Seymour 1980; Owen and Pilbeam 1992, p.45.

466 \

the soil, and maritime crossings, straits and all the geo-political features which have focused in the past, and focus today, the interest on one place rather than another, and likewise can help understand the reasons for their development and decline. Here I may just mention the opening of the Suez Canal and the consequent reduction in traffic along the Atlantic coast of Africa, with the opening of certain ports and the closure of others. This brief note intends to examine some of the questions facing who wants to investigate the nautical cartography of the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century, and also to analyse the relationship, if any, between the ways in which the representation of land and the representation of the coastline and the sea are conceived. In other words, I mean to discover whether the same mental process is behind the different representations of the physical world. I will also present an example of international cooperation for the production of a hydrographic map of the Adriatic, which well fits the concept of 'cartography as imitation of nature')

A dream of completeness I should like to begin by pointing out some convergent aims in the production of land maps and nautical charts between the end of eighteenth and the beginning of nineteenth centuries. This was the period of the great technological and scientific revolution of the late Enlightenment years; suffice it to mention the studies on the shape of the earth, the length measurements of a Meridian arc, the introduction of the meter as a unit of universal uniry of measure, the construction of a machine to divide the circular scales by Ramsden, the Borda multiplier circles, the refinement of calculus methods, etc. This was as crucial a period for cartographic representation as that of the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries, which witnessed the birth and development of the nautical chart, or the fifteenth century, with the innovations produced by the discovery and circulation of the geographical work of Ptolemy and the invention of the linear perspective.4 Nevertheless, the revolution that happend in cartography in the examined period was not merely technological, or, to express it in other terms, the technological revolution expressed on maps was revealed not so much in its 'quantitative' aspects (metrical exactness, geographical grid, accurate computation for projections) as in its 'qualitative' ones (symbols, colours, slopes and valleys, field and meadows, landscape in one word). It was not so much the notion of metrical precision which pervaded mapping as a more all-encompassing and subtle notion. The elusive dream which emerged from the time of the Napoleonic wars and continued to develop up to the middle of the nineteenth century was the idea of being able to produce a 'perfect' map. It is clear that the concept of perfection to which I refer does not concern metrical precision but relates to a semantic properry of the map whereby map-makers aspired to represent the territory 'just the way it was' in its totaliry and technology seemed to provide the tools for realising that dream.5 I should like to emphasise here, that one cartographic representation may be regarded as being better than another, not because it is more precise or metrically more exact, but because it carries a larger amount of information. In it the information is expressed with greater clariry and with greater awareness of the function and meaning of the mapping process itself. Superioriry, where it exists, is a qualitative rather than a quantitative matter, and in this sense cartography might be likened to a linguistic model. 6 During that crucial period of history, there was a steady belief that a map was capable of representing the territory in its entirery to the extent of virtually replacing it. Symbology, colouring, the refined techniques of the map-making process, the adoption of increasingly large scales all contributed to the reinforcement of such an illusion. In England during the first half of the nineteenth century a lively debate was raging, subsequently known as 'the battle of the scales', which led in 1858 to the adoption of the scale 1:500 for urban areas and 1 :2,500 for agriculturalland.7 It was only in 1893 that the decision was taken to put an end to that experiment, abandoning for good the extensive output of maps on such high scales: production times and the costs curbed expectations. Even now, in the new millennium, we still have not equalled those achievements because, although we have the means, that myth has waned. That dream was produced by the illusion of ever unending human progress, which had produced a climate of growing euphoria in other disciplines and in Western culture as a whole. The limits of this excitement, which dramatically crashed in the First World War, were expressed in a narrative form by J oseph Conrad and, in a completely different form, by Lewis Carroll. In An outpost of progress (1897) and in H eart of darkness (1899), Conrad tells - and we must not forget that this are 'only' stories - of the abyss into which the human being can fall as an exporter of his civilisation and he stigmatised (as we perceive it now) the opulent European sociery and its colonial culture: 'Nobody knows what suffering or sacrifice mean - except perhaps the victims of the mysterious purpose of these illusions' , while Lewis Carroll, satirically, crushed the cartographic illusion, that is the 'grasping' attitude behind a map on a large or extremely large scale. Here is what he wrote in that same formerly mentioned year 1893:

'M 'TE'MORIAL '-, ..

TOPQGRAPHIQUE ET MILITAIRE~ .

REDIGE ·

AU DEPOT GENERAL DE LA GQERRE, I ' .

'" . " . P A: R 0' R D RED (J M I NI S T It E.

, N.o . 5' TOPO'GRAPHIE~

III.e Trimestre de I'an XI.

A PARIS~ , , L'IMPRIMERIE DE LA REPUBLIQUE.

Fructidor an XI.

fig. 1 Title page of the Memorial Topographique et Militaire, published in Paris in 1803 (Private collection).

'That's another thing we've learned from your Nation,' said Mein Herr, 'map-making. But we've carried it much further than you. What do you consider the largest map that would be really useful?' 'Abour six inches to the mile.' 'Only six inches! ' exclaimed Mein Here. 'We very soon got to six yards to the mile. Then we tried a hundred yards to the mile. And then came the grandest idea of all! We actually made a map of the country, on the scale of a mile to the mile!' 'Have you used it much?' I enquired. 'It has never been spread out, yet,' said Mein Herr: 'the farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country, and shut out the sunlight! So we now use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well!'.

This amusing dialogue was drawn on with greater critical acclaim by lorge Luis Borges and later by Umberto Ec08 who ignored however not only the author of the aphorism but also the historical reason and the meaning (or at least one of the meanings) of this dialogue.

A turning point A shift towards an all encompassing concept of cartography took place at the beginning of the nineteenth century with the publication of Memorial topographique et militaire in Paris in 1803 (fig. 1). Even though the Commission producing the text was merely requested 'de simplifier et de rendre uniformes les signes et les conventions en usage dans les Cartes, les Plans et les Dessins Topographiques',9 the resulting text was in some ways revolutionary. For the first time reference was made to the decimal, or natural, scale and the maps were classified on the basis of the scale: 'Topographie de detail', scales

V L ADI M IR O VA LERIO

8

Borges & Casares 1973; Eco 1983.

9 Memorial Topographique et Militaire, n. 5 Topographie, Paris, an XI [1803], p. 1.

1 467

MAPPJE ANTlQUJE

--~ .. .. L

.PIOTlche 4 .

Signe1l pour l'Hytfro~l'aphie .

... A .. :.JIltrnri .. J'ala;, ... ... '" ... , ..... .. ...... ~ · . B . .. .l{ucher.r "'liP 1e.r.QUnh, ,le h£· ,;ye/,. . . . . . . . . • . . • . . . " . .,.... . · .. C .. . .lJTHI&J' . ' .. ~ ... D . .. £(rt~-.re, {le hml!? .Ner ... • .. . . . ......•. . , .... ' .... ..... ___ ..... _

· .. E ' , . £ai.r,,'e {le /JI'I.r.re, .Ner ..

· .. . F .. , .l'fcher;e.r . ..

.. G .. . Kadra!1l£e .,'. . . ... . . " . .. . .. . (;~..tz;;> . "<C>

. . _ .. H .. . .lJonc. tk J,;ble lo,!jOllr.r tk;"ollverc . . . . . . . '. . . .. . ~ . . ..,. ..:;: .... +-•• ~r ..... ,

....... I . ' .. .lJOTlC de, .Fable· {lli colLvre pt de.'colwre .. . " . • . . . . ... ' .'~''t.t.~~

J ./J . .7 ".H . J ' ', ' ' r-----" · . .. ... tZllC «e" unul" yzn. lIe, £r"CUlIV,J'CV J07ll1rt.r . .. '. ' . . . . . .. . f ~

1 . - t-.....-------.'J

· . K ... .lloch e.r 'Auj/ollrd' d'P'clm:ue/·je.r. . . ....•.•...... ~

· . . M .. flurhe.r ~U7; n e Eie;WtlUrellb j07IlQ'L:r .... • . . . . . . '. . • . . . . t ·

... N .. . fle'ctJii' -et' .lJri.rlUIJ' . . , ..... ...... • . .. • . : .. . ... . "~;::'::'

'" .0 ... Bmal . . , .. ..... . . ' . . . . . ' . . •.. : ........ . ... : ... F . P ... Toup - .F&nal .... ' , ' " . ........ .. . : .... . .. ..... i

. . . . . Q ... .lJalz~·e.r.. ............ . • . . .. ' •. . • .. ,.: . .. .. .... 1 1

-... .R .. . .lJollee vILrulln"' . . . .. . . . ' ....... • ...... . ...... _ .... 0

I • . j S ., ~Jle/~" Ulb..dm.o ... J' .••••• , ••••• • • . . ...... ... .. ~

0 . .... T ... Pore ... ............... . . .. .. .... ....... ~

;t; ......... . u .. . .Homlla!1e ,{ar FmJJ"efllU" ,k £&ne . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .t.

• .j, ...... . ... v .. . .IorcLllo,;'e rl~ /""Iib Ikdimnl'.r " ..... ... .... ; • . . . . . . . . ""

11 · · ... . .. .. x .. . (o?,J'-morl' . .... , ..• . ' .• ........... ' . ....... .. 11 f D,m.r Iv GIrIN ~J'Anw d .. .,/'ot« ,-• K_~_n7I. i£cmtow.1" <k /

XOfu) h',rtfnn.kr ,.n. "if.lmfm" EN { .. """,;~ . .1jur", 10",";1""''''

. \ Dtme"~arrhvD~'yn·.u«tll/illb8ltJrJN'~ t:k~ri"'i"~o{~ . .

.J#Ij.,.$",$

. ·4·'7.J ·4 -I.i "9

. . Y .: . J'QllIleJ' .. . . : . ' ... ... .

~ ...... .7: .. . .D(rec/ron de.r COlO'flLhJ' . .• •. ••

..Mt' ~i;-.LS . . . .... . ....... .. . ~.~.J

-9 .,.~ "9-

. .. . . .. . . . . ... ............-

fig. 2 Figure number 4 attached to the Memorial Topographique (1803), related to the hydrographical symbols (Private collection).

IQ

Memorial Topographique . .. , p. 112. 1I

The same expression was used some decades later by Aristide Michel Perrot, in his famous Modeles de Topographie, Paris 1819: 'Il faut que le dessin nous transport sur le terrain' (Introduction, p. I).

468 I

:'S'IGNES CONVENTIO.NNELS PD1IF la-Cfiorographie et l'l!vdrographie.

,;'l'XrhUe ,k ,z.K;lkmptnv p t",./, LOOO L';"'t:.r'olr s"-i;;J,,.

1 :2,000 and 1 :5,000; 'Topographie Generale', scales 1: 1 0,000, 1 :20,000, 1 :50,000 and 1: 100,000; 'Chorographie', scales 1 :200,000, 1 :500,000 and 1: 1 ,000,000, and finally 'Geographie' with the scale 1 :2,000,000. IQ

Additional symbols and systems of representation are adopted depending on the theme of the map and on its scale; reference is made to symbols 'pour la Topographie', 'pour l'Hydrographie', 'pour la Mineralogie', for military campaign maps (fig. 2). The provisions laid down by the Commission, which had been set up in 1802, go far beyond the bare standardisation of the conventional symbols, an operation which would appear to be extremely cold and mechanical; through notations of a purely technical character the Commission enters into the merits of the purpose and uses of the maps, discusses their contents, furnishes indications of its construction procedures and broaches with the institutions and the educational background of the men tasked with the topographical operations. The map must above all be a faithful representation of the terrain: 'il faut que la carte no us transporte sur le terrain' ,H according to the experts of the French Commission. Mind, this is not a generic recommendation: the use of this and other phrases indicates that the map is intended to be a perfect imitation of nature, that is, 'la nature

,.'

""",-_rma di.-Lac C 0

'lOplt~llo ':.0 . o

elle meme revetue de ses formes et de ses couleurs, mais reduite aux dimensions de l' echelle' P The large scale map is a depiction of nature and thus the more it imitates nature the more perfect it is, both in form and in colour: a farm, a garden, a mountain, every detail must attract the attention of the observer, who should be enabled . to move about on the map as though he were walking over the territory itself. It is not accidental that in the Memorial, even though it was accepted that contour lines provided a more faithful metrical representation of the territory, their use was discouraged both on account of survey difficulties (tachymetry was still a thing of the future) and of the not very natural effect they produced: 'les lignes de plus gran de pente, ou de la chute des eaux, offrent, sur les courbes de niveau, I'avantage de representer un effet naturel dont I'oeil est temoin a chaque instant, et qui rappelle la cause generale, sinon la formation, au moins de la figure et des accidens des montagnes. Cet effet est un moyen d' evaluation et de verification' .13 Again in 1836, the Director of the Geodetic Section of the Reale Officio Topografico di Napoli (Topographic Office of Naples), Fedele Arnante (1794-1851), discouraged the use of contour lines, observing that 'illungo ed importante lavoro della carta topografica di un Regno nori puo avere questo solo oggetto (cioe rivolgersi ai militari e ai tecnici), e deve anzi considerarsi come di ragion pubblica, onde e necessario che parli chiaramente anche agli occhi di coloro che poco 0 nulla conoscono di Topografia' [the lengthy and vital work of constructing the topographical maps of a Kingdom cannot be confined to that one objective (that is, the military and technical use), and should therefore be viewed as public property in the public domain, wherby it is necessary for it to be clearly understood also by those with little or no knowledge of topography].14

VLAD IMIRO VALER IO

..

fig. 3 Detail from the sheet number 10 of the Carta Topografica ed idrografica dei dinrorni di Napoli, surveyed in the years 1817-1819 and engraved in 1821, in the Officio Topografico of Naples. Due to its hig quality both in content and in beauty of the engravings, the chart received a Medal in the occasion of the Exposition Universel of London in 1862 (Private collection).

12

Memorial Topographique . .. , p. 41.

13 Memorial Topographique . . . , p. 36.

Fedele Amante, Osservazione suI metodo di configurare il terreno a curve orizzontali, . Naples 1835, p. 6. O n Fedele Amante see Valerio 1993, pp. 438-440.

1 469

MAPP IE AN TIQ UIE

15 Dubbini 1994, 5.

Concerning the Court painter Alessando D'Anna and his mapping work, see Valerio 2002, 59-65.

17 Memorial Topographique . .. , p. 33, 34.

18 Correspondance astronomique, geographique, hydrographique et statistique du baron de Zach, Genoa 1818-1826, vol. I

(1818), p. 276.

470 \

New concepts in charting Nautical charting too passed from being a partial reconnaissance, a simple theme map, to a perception of the entire world even though sub specie hydrographica. At times, the topographical map coincided with the hydrographic chart, as in the case of the famous Carta Topografica ed idrografica dei dintorni di Napoli (fig. 3), constructed in the years 1817-1819, in the Topographic Office of Naples on a scale of 1 :25,000. In other instances, such as the Carta di Cabottaggio del mare Adriatico, published by the Military Geographical Institute in Milan in 1824, hydrography got the upper hand. Nevertheless, even though the survey does not extend more than a few nautical miles from and into the coast, those strips of land and of sea water are described with the most painstaking care and attention in the minutest details. The aim is to enable the mariner to move about as though he himself were on that sea -like the soldier or naturalist on land - scanning those horizons, showing him even things which were out of his sight: soundings, the quality of the sea bed, the urban structure of the coastal towns, and obviously landing places, sheltered spots, elements appearing on terra firma that will help him recognise the coast and mooning places. Everything is defined in a highly punctilious manner, with the result that coastal charting, an operation of venerable origin, and reproduced on nautical charts as early as the sixteenth century, were brought to the highest level of identification and imitation. It is not by chance that place recognition is one of the basic themes of modern cartography and charting. Britain, a great maritime nation, was somewhat ahead of its time in applying artistic techniques to coastal reading and the hydrographer John Seller used the services of a highly talented artist, Wenceslaus Hollar, in the belief that 'una superiore qualita dell'immagine possa favorire l'informazione, potenziando l'intelligibilita dei luoghi' [a superior quality of image might favour information, by furthering the understanding of places].15 In later years, training of specialised graphic artists was one of the priorities of the Admiralty for constructing hydrographic charts and this led to the appointment of Alexander Cozens as master of the Royal Mathematical School at Christ's Hospital. In Naples, some decades later, the court painter Alessandro D'Anna (1743-1810) joined the team of mapmakers working for the Commissione della Gran carta del Regno [Commission for the Great Map of the Kingdom of Naples] with the specific task of drawing the mountains: who better than a painter could depict mountains, one of the dominant and most variable fearures on the landscape of Southern Italy?16 In the Memorial once again due account is taken of the significance of hydrographic surveying with respect to coastal identification, and the combination is accepted of horizontal and vertical projections on the plane of cartographic representation: 'La Commission' - as we read in the chapter on orography -'remarque que les marins n'ont pas seulement besoin de connaitre avec precision la forme, mais aussi les situations horizon tales des objets qui determinent les directions des vaisseaux: elle pense donc. .. de laisser ces objects en projection horizon tale, sur le plan des cotes, et de joindre en marge, sur de petit plans separes, les projections ou les vues de ce points de remarque' after which it is asserted that 'il est donc necessaire, du moins pour quelques temps encore, de conserver, dans les cartes hydrographiques, l'usage de quelques projections verticales sur le plan des cotes'.I7 The camera lucida was used for coastal views and the resulting panoramas did not lag far behind the landscape paintings en plein-air of those years, when painters left their studios and went to depict nature. It was not merely the Neapolitans who distinguished themselves in this way, but also the French, the Germans, the Austrians, the Spanish, the British, in fact, the entire hydrographic culture of the Western World.

The Carta di Cabottaggio of the Adriatic Sea Beside the Carta Topografica ed idrografica dei dintorni di Napoli, another topo-hydrographic achievement of those years captures the eye on account of the cartographic 'quality' which I referred to above, that is the Carta di Cabottaggio del mare Adriatico resulting from the Neapolitan, Austrian and British collaboration in the years 1817-1819 (figs. 4-6). At the beginning of the nineteenth century the Adriatic could still be regarded as a relatively unexplored sea and its charts were judged doubtful and unreliable. Little was known of the extension of the Otranto Canal, of the distance between Ancona and the Dalmatian coast, the positions of its innumerable islands, or of the soundings, currents and tides. In 1820, Captain William Henry Smyth, of the British Admiralty, was able to draw up a list of hitherto undiscovered islands along the Ionic coast of Greece, near the mouth of the Adriatic Sea. Baron von Zach, to whom the scientific correspondence of Smyth on Adriatic charting was mostly addressed, rightly remarked that 'il est vraiment etonnant qu'une mer aussi frequentee, aussi dangereuse, par ses cotes, ses iles, ses ecueils, comme la mer Adriatique, ait ete si long-temps mal connue'.I8 Charting, entrusted to Ferdinando Visconti (1772-1847), started in 1808 at the War Office of the

l( J'

<\> (I

........ -'~'.~\,

\, .

,

\.

~

\

A D It I A T 1 C" i1';:-

~tc\lG "l\~ tryl ~~\'\1\ . ~3.Jl\-;"~~ .,' ,)

7

~";~: . /

G

~

G

~

I .~

I \

"

ES!tN1817

:,

\t " ::

- <"

..t'_o ..

,..--.'

/ .# -.~ --

1\>--<'1. P L

fig. 4 Title of Chart of the Adriatic Sea Sicily and Jonian Islands with the track of His Majesty's Sloop Aid from 1817 to 1820, by Lieut. Skyring. The chart shows the rou

tes of the Aid, under the command of

William Henry Smyth just during his period of charting in the Adriatic Sea, 771 x 551 cm, manuscript in black ink

(Taunton, Hydrographic Office, C 94).

VLADIMIRO VALER IO

fig· 5 Detail of the Chart of the Adriatic Sea by Skyring, showing the track in the lower part of the Adriatic Sea for the charting during

the period of the Neapolitan, Austrian and English Cooperation. The script in bold are

mine addition but are only enlarged figures

following the original text (Taunton,

Hydrographic Office, C 94).

~,f,~6'1"~c7/~ -+

.. / ..

~~~,' ~: 1818

l / If;:

:.,'

I A

,.'

1471

MAPPJE ANT 1QUJE

PORTa BI ANCONA ,a . ...:l'B. .£ .. 1',#-, .. ",,; .1"'" my"" .,1',,,,., Il';~ ,,11, 1',;;, h~" " .. ,,.;,, ... , "''''_

"uh€"I,.~ ,; , ,,;../," I""-&~;"' · ("~ ,~/ .. _ u", 11''''''''''" ",,,,1': , 1'0111" 9 . ]., ... »4. ~o.

.37ff(

>3. 3$.

3 • . '0.

!lo.

Xc 10'\"i,,~~,o1;'" ~.\ ,\,wt.L. Cll'" tOW1\» JmwC.u '"t\.tt~ ,}-'d'l.k ~'I tc..'l.U ,wtf.u,",,", le);, .

.6.

~.9' '''

r. .. _ p,.",.fo".1ih'. lut".", C D" ",,'Il"'; <I'Odb!tio.;"h:. c.n",..

~':!7 ' ":ff. ~ .• oM/'" "rot"'" "r",uJ.'.!!";.h."'.ll·aruw,,u!~6 . "

.h,t. s "Hotn 'W/UN> , -If- all' ,,; pw'!." ,. .. /IP {uvJO/Jo.f:I"n i,

,.on fi. l'"h,6u.,u,,,". fi"d.dh., ~ h"'U(.~i I'nllU! '1''': .rl · " .. de-.

• e- 9u~lli- .rOf/'(J pu7U:e,?UUi C~.~ .¥.~ ~f '}c..

fig. 6 Detail of the harbour of Ancona .from the sheet nr. VI of the Carta di Cabottaggio del

Mare Adriatico, surveyed during the years 1817-1820 and engraved in Mium in the years 1822-1824. A great attention is paid to several topographical details in order to enrich the image with any kind of geo-morphological information (Private collection).

19 Details of the first Milanese work on

charting the Adriatic can be found in Ferdinando Visconti, Sulla posizione geografica e sulla larghezza della bocca del

mare Adriatico, Atti delUz Reale Accademia delle Scienze, Napoli, vol. II (1825), pp. 51-122; and in Smyth 1854, 360 et

seq. 20

F. Visconti, SulUz posizione geografica . . p.57.

·21 Smyth 1854, 363.

472 I

Kingdom of Italy in Milan and was fundamental in getting to know that sea.19 From those surveys, which were interrupted in 1814 because ofVisconti being moved to Naples and the Kingdom ofItaly coming to an end, derived the map of the Adriatic drawn up by the Austrian and Neapolitan staff officers in co-operation with the British Admiralty.

The latter was called to take part in the hydrographic surveying only at a later stage, when Visconti realised that in order to complete the charting 'rimaneva ancora a ben determinarsi la posizione e configurazione di tutta la costa dell' Impero Ottomano bagnata dall'Adriatico stesso e dallo Jonio, da Budua fino a Parga, la quale finora e stata un tratto di paese veramente incognito, sebbene in Europa' [he still needed to determine the position and configuration of the whole coast of the Ottoman Empire along the Adriatic itself and from Jonio and Budua to Parga, which has so far been virtually unknown territory, even though it is in Europe].20 It was necessary, therefore, to work along the Albanian and Greek coasts, which at the time were under Ottoman rule. In particular, the stretch of territory to 'explore' run from Budua, where the Austrian trilateration was interrupted, to Parga in Epirus. Smyth clearly recalls the time and the reason for his being called to participate in the survey campaign: 'I was formally applied to for the purpose of giving their [Austrian-Neapolitan] operations a maritime completion, as well as to carry a continuation of the survey along the Turkish shores as far as Parga, where respect could then be commanded only by the British flag'. 21 It was for reasons of political expediency that the governments of Naples and Austria were induced to ask for British help. But in addition to this there also was a personal acquaintanceship and even friendship between Colonel Visconti, Director of the Topographic Office of Naples, and Captain William Henry Smyth, a friendship which endured over the

years and which is evident in the exchange of letters with Ferdinando Visconti. 22 'I repaired to Naples early in 1818, - continues Smyth in his Mediterranean Memoir- and there entered into a convention with Marshal Koller,23 Count Nugent,24 Colonel Visconti and Baron Poiter' .25 The convention was signed in Malta in June 1818,26 and Smyth immediately embarked on the operations of surveying and sounding the Albanian coastline and the Ionian Islands. The hydro graphic project was coordinated by Major Antonio Carnpana (1772-1841), Director of the Military Geographic Institute in Milan, and by Visconti and Smyth, Captain of the sloop Aid, 'vaisseau, lequel, pour ainsi dire, est un observatoir flottant', according to the definition given by Baron Potier des Echelles of the Austrian staff, who had been appointed to carry out the hydrographic survey. 27 In the Malta Convention it was agreed that Smyth would accommodate on board four Austrian officers: the Barons Potier, Granzenstein and Jetzer and First Lieutenant Lapie, together with two Neapolitan geographical engineers, Captain Soldan28 and First Lieutenant Giordano. 29 To this squadron were added 'an Austrian sloop-of-war, the Velox, of20 guns, commanded by Captain Poltl'30 and 'two more officers of the Neapolitan staff, Captain Chiandi31 and Lieutenant Bardet'.32

This was an interesting and, perhaps, one of the first cases of scientific cooperation at international level, derived from the converging interests of the two great European powers, victorious in the conflict against Napoleonic France, and of the Kingdom of Naples, a third of its coasts being on the Adriatic sea. Austria felt the need to acquire in-depth knowledge of its sea outlets; Britain, which had for some years been carrying out surveys of the entire Mediterranean Basin, seized the opportunity to acquire intelligence on this internal sea, which hitherto had been visited only by French hydrographers; and the Bourbon Court of Naples felt the need to review and update the old maritime chart of the Kingdom which had been compiled under the supervision of Giovanni Antonio Rizzi Zannoni between 1782 and 1792.33

Outputs The Neapolitan, Austrian and British expedition completed its own work at the end of 1819, after about two years of intense and fruitful cooperation, in the course of which, Smyth records, 'those gentlemen and ourselves had always been on the best of terms'.34 The cooperation between the various parties involved, mainly took the form of exchanges of information, which was at the basis of the Malta Convention. In actual fact the Neapolitans are to be credited with the entire survey of the Adriatic coast from the River Tronto, which marked the northern border of the Kingdom of Naples, to Cape S. Maria di Leuca. Also, with the control over the entire geodetic network resulting both from the work carried out by Ferdinando Visconti during his command at the War Office in Milan, and from the observations carried out during the brief period following the conquest of the Marches in 1814, shortly before the downfall of Gioacchino Murat. In those few months the Neapolitan engineers were able to join the triangulation of Northern Italy with that of Southern Italy, in the vicinity of Ancona.35 The British were working on the Ottoman coast between Budua and Saseno and, as Smyth records, 'with the excellent means then at my disposal, a chronometric chain was run over the whole sea, and extended into details by copious triangulations'.36 The British were also tasked with ~'particular plans of the harbours we resorted to', and all the material produced (observations, drawings, soundings, etc) was 'promptly sent both to Milan and Naples' .37 Traces of the exchange of information between Naples and London are to be found in the archives of the Hydrographic Office in Taunton (UKHO), in the form of some maps of the Adriatic coast compiled in Naples and some coastal landscapes drawn by the Austrian officers all bearing the inscription From the Neapolitan, Austrian and English Co-operations (fig. 7).38

22

Valerio 1995. When Visconti sent in 1846, a few copies of the Map of the Mediterranean Sea in three sheets to the Hydtographical Office, engraved in the Topographic Office of Naples, he specifically asked Sir Francis Beauforr to 'volerne passare una al mio ottimo arnico Sig. Capitano W H. Smyth ora presidente della Sociera reale Astronomica' [pass one copy to my dearest friend Mr Captain W H. Smyth, president of the Royal Astronomical Society]' p. 204.

23 Franz Friedrich von Koller (1767-1826) Austrian general and diplomat, Commander of the occupying forces in the Kingdom of Naples in 1821, a close friend ofVisconti.

24 Count Laval of Nu gent-Westmeath (1777-1862), Commander in Chief of the

Bourbon army.

25 Rudolf Baron Potier des Echelles of the Austrian staff, brother-in-law of General Koller.

26 Details of the Maltese Convention between the Neapolitans and the British can be found in the State Archives in Naples, Segreteria Antica di Guerra e Marina, IS. 724, with some items of correspondence between Smyth and Visconti.

VLADIMIRO VALERIO

27 Letter adressed to the Astronomer Franz Xavier von Zach, headed Naples, 25 Ocrober 1818, published in Correspondence ... , lvo!. (1818), p. 458. The vessel Aid a 'sloop-of-war', specifically fitted out for hydrographic expeditions, reached Malta on 7th of May 1817 and was made available to Smyth for his own observations in the Mediterranean.

28 Pietro Soldan, an officer in the Engineering Corps of the Milan Geographical Engineers, who was on active service in Naples from 1815 to 1821, see V. Valerio, Societa Uomini . .. , p. 632.

29 Fridolino Giordano (1786-1872), an officer in the Engineering Corps, a Neapolitan geographic engineer and Director of the Topography Office in Naples from 1849 to 1860, see Valerio 1993,406-408.

30

Smyth 1854, 363.

31

Giovarnbattista Chiandi (1785- on active service until 1821) an officer in the Milan Engineering Corps and active in Naples from 18'15 to 1821, see Valerio 1993,476-

478.

32

Federico Bardet di Villanova (1796-1868) an officer in the Engineering Corps, a Neapolitan geographic engineer, see Valerio 1993,446-447.

33 Regarding this work, see Valerio 1993, 130-155.

34 Smyth 1854,365.

35 Concerning this work, see Valerio 1993, 226-227.

36 Smyth 1854, 364.

37 Smyth 1854, 364.

38 My thanks go to Anne Browne and Guy Hannaford of the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office for their kind assistance before, during and after my period of study in Taunton in April 2005.

1 473

MAPPJE ANTlQUJE

fig. 8 Key index of the Rilievo e idrografia del Promontorio del Gargano in three sheets in scale 1:20,000 (Taunton, Hydrographic Office, G 11). Other sheets: number two (shelfmark G 15), and number three (shelfmark G 10).

fig· 9 Detail ofViesti in the Promontory of Gargano from the Rilievo e idrografia del

Promontorio del Gargano, sheet number one (Taunton, Hydrographic Office, G 11).

474 \

q,:;} I

(Ii S~tjOI·f"ll:;()

fig. 7 Title of the Rilievo e idrografia del Promon

torio del Gargano alIa scala di 1 :20.000 del terreno, surveyed by Neapolitan geographical engineers for the charting of the Adriatic sea during the period of the Neapolitan, Austrian and English Cooperation, 601 x 949 cm, manuscript in black and carminium inks. The chart was copied in the Topographical Office of Naples and sent to the Admiralty in

1820, as it appears in a handwriting at the bottom of the map: Certificato conforme

all'Originale esistente in quest'Officio

Napoli li 29 1uglio 1820 Il Colonnello

Direttore, signed Ferdinando Visconti. In rhe bottom right corner: From the

Neapolitan, Austrian, and English Co-operations (Taunton, Hydrographic Office, G 11).

... .f~

..

J"lo'tcv s:" ~;"" ,Cl?<", .""i,(, ~ ·';, ri .fW'''.C/''';'''''''' ·I.~f, """.,1,;'\10 JrI'f'~f",'f'" "'~ J.i,'I""":b.«J J.i: 'l",ntc/" ''''0e;",. ~''ffCL f-(i(,l,J..t~Th·~i"'VI(l -ft., .... 't-'''':T,l'.At.f-O ~1 ' \,~ ,J~I',-L. ,'U''''n 9, .... ..tff.fl..o-',')(l./(,,t-;.(!.........- .... J

,";,~.,",~':;:;i!:_~ ~ ,"~~ ~~ .. ;'~'~PF~~'~" ~~ ~.~. ~ ~"9 •• .,. ~ • ~ .. ;jJ. '>C. "" f .... _... ';..

~, '" • • .. h,~

,

\

, ,"': '~

1c///

VLADIMIRO V ALE RIO

fig. 10 View of Ca po Rodone, levata il giorno 29 agosro 18 18 (taken the 29th August 1818) with the camera lucida looking towards

NE and positioned at 5 miles from the Punta del Capo (Taunton, Hydrographic

Office, Mediterranean Pilot voL 2, p. 44).

fig. 11 Detail of the view ofDrino taken by Baron

Grdnzenstein on the 27th August 1818 and transmitted from the Istituto

Geografico Militare in Milan to the Admiralty on the 3rd June 1820, as it

appear in a handwriting at the bottom of

the map (Taunton, Hydrographic Office, Mediterranean Pilot voL 2, p. 43).

fig. 12 View of the city of Corfo, taken by Baron

Grdnzenstein (Taunton, Hydrographic

Office, Mediterranean Pilot vo!. 2, p . 53).

1 475

MAPPJE ANTlQUJE

39 'Idrografia generale I delle I Coste del

Regno delle D ue Siciliel Bagnate

dall'Adriatico. I eseguita dagli Ufficiali ed

Ingegneri dello Staro Maggiore

dell'Eserciro I e costrutta secondo la

Projezione di Cassin i de T hury I nell 'Officio Topografico di Napoli

11 820' , com p rising two m anuscript foli os

(numbered I and II) , on a scale of

1:200,000, measuring respectively 714 x

1290 and 600 x 900 mm (UKHO, G

l Ob e G IOa) , each of which bears the fol

lowing inscrip tio n: Certificato con forme all'originale esistente in questo Officio di Napoli li 20 Agosto 1820. 11 colonnello direttore Ferdinando Visconti.

40 Rilievo e idrografia del Promontorio del Gargano alla scala di 1/20,000 del Terreno, three manuscript fo lios: fo lio I, 60 I x

949 mm, watermarked J Whatman 1811 (UKH O , G 11); fo lio 11, 601 x 949 mm,

same watermark (UKHO, G IS) ; foli o

Ill, 60 1 x 949 mm, sam e watermark

(UKH O, G 10) .

41 'Mer Adriatique' in : Corresponclance astronomique, geographique, hydrographique et statistique du baron de Zach, Genoa, vol.

8 (1823). pag. 489.

42 T he landscapes are preserved in

'Mediterranean Pilot' vol. 2 , in particular

I would draw attention to the pages m en

tioned in the box text.

43 Many of the landscapes signed by

Granzenstein which are held in the

UKHO were sent by Antonio Campana,

Director of the M ilan Geographic

Institute, to the Admi ralry in June 1820. T hese landscapes are kept in

Mediterranean Pilot , vol 3, pages 23, 24, 26, 36, 39-58 . A few landscape drawings

by Granzenstein are also kept in the

Archives of the Istituto Geografico

Militare in Florence: see Catalogo ragionato delle carte esistenti nella cartoteca dell1stituto Geografico Miltiare, Firenze

1934.

44 Concerning the use of the camera lucicla fo r scien tific purposes and ro give a new

outlook on the study of natural phenom

ena, see Fiorentini 2005.

45 Piano / Del Porto di S. Giorgio / nell1sola di Lissa / eseguito clal/ Capitano Wm Hy Smyth. /1819, handwritten in black ink,

617 x 930 cm, watermarked J Whatman 1811, Certificato con forme all'Originale esistente in quest'Officio / Napoli 19 luglio 1820 / 11 Colonnello Direttore / Ferdinando Visconti (UKHO. G 14).

46 Concerni ng this period in history, see

Valerio 1993, 246-250.

47 See Smyth 1854, 37 l.

48

See Valerio 1993, 230-23 1

476 \

The Neapolitan maps are of particular interest in the history of Adriatic cartography, because the originals, formerly held in the Topographic Office in Naples, have either been lost or were destroyed during the last quarter of the nineteenth century and the therefore 'copies' safely kept in the UKHO in Taunton are, as far as is known, the only surviving examples. In one of those bundles on a scale of 1 :200,000 there are also drawings of the great triangles which joined the two coasts of the Adriatic Sea and which constitute the framework of the survey: one of the sides, Tremiti Islands - S. Andrea in Pelago, measures a good 103 km in length at the limit of the geodetic visibility.39 Of outstanding significance too, for the study of territorial history and landscape history, is the Rilievo e idrografia del promontorio del Gargano in three sheets on a scale of 1 :20,000, as it is 'certified as being a true copy of the original held in this Office' (the one in Naples) and signed: 'William Henry Smith Captain', underneath the inscription 'From the Neapolitan, Austrian, and English Co-operations'40 (fig. 8 and 9). Instead, of Austrian make there are, at the UKHO, only a number of coastal views. Of particular interest in the history of art and of cartographic reproduction is the wide use that was made for the first time in topography of an optical device invented as recently as 1804 by the English physicist William Hyde Wollaston (1766-1828): the camera lucida. We know this from Baron von Zach's invaluable Correspondance Astronomique: 'Pour la levee des vues, on a presque toujours fait usage de la chambre optique'41 (fig. 11) . Soundings and coastal views with the mooring and landing places in the Kingdom of Naples had all been carried out by the end of 1817, just before the British first became involved,42

whereas those done along the Albanian coast are dated 1818 and 1819, and were all the work of Baron Granzenstein,43 who was working aboard Smyth's Aid Each drawing notes the day of resuming work, the azimuth direction of the camera lucida and the distance in nautical miles from the coast, a sort of ante litteram photographic record44 (fig. 12). In addition, copies of some observations by Smyth, but preserved in the Naples Office were sent to the Hydrographical Office, among them Piano Del Porto di S. Giorgio nell1sola di Lissa, based on a drawing by the English officer and copied and sent by Visconti on 19 July 1820.45 This copy was to be the last one to be done by Ferdinando Visconti and to sent by him to the British Admiralty. On 6 July 1820, following a military insurrection, King Ferdinando I of Naples delegated the regency to his son Francesco Duke of Calabria, and on 12 July there was a meeting of the provisional Council which was supporting the regency in the new constitutional government. Ferdinando Visconti was elected to the new Parliament and his involvement with the Constitutional government cost him, in July 1821, his rank of Colonel and the position of Director of the Topographic Office.46

In this stormy political atmosphere, which saw Europe once again on the brink of revolution, the Imperial Military Geographical Institute of Milan decided to publish a 24 sheet atlas of the Adriatic Sea on a scale of 1: 175,000, illustrated with coastal views. The map was engraved and published in the years 1822-1824 and, unfortunately, Austrian gave no acknowledgement either in the title or in the notes attached to the individual maps, of the lengthy work of cooperation with the British and the Neapolitans, a circumstance which gave rise to remonstrances: 'the want of a more liberal unanimity was, however, injurious to the Austrian publication'47 (fig. 14 and 15). The publication of the atlas of the Adriatic sea by Austrians, without any acknowedgement of the work carried out by the Neapolitans and the British, provoked reactions both from Smyth and Visconti, but the incident is too well known48 to warrant further mention here (fig. 13).

Landscapes preserved in 'Mediterranean Pilot' vol. 2: (note 42) - p. 16: Western shore of the Adriatic: five landscapes, to three of which have been added handwritten inscriptions in Italian recording the

dates: levata if 3 9bre 1817, levata il9 9bre 1817, levata il5 9bre 18 11, all relating to Cape S. M aria di Leuca;

- p. 17: Western shore of the Adriatic: five landscapes of which two carry the following handwritten inscriptions recording the dates: levata il 10 9bre 1817, levata il19bre 1817, Porto Vadisco e Castro. The landscape ofPorto Vadisco corresponds to the one marked (Porto Badisco)

which compares with the last picture;

- p. 19: Western shore of the Adriatic: five landscapes, only ~ne of which bears a handwritten inscription and records the date: levata il 12 9bre 1817, Costa clal Caste/lo di Castro sino al Capo d'Otranto, 63 x 678 cm, the same print as that appearing as a second (Veduta della costa compresa tra Castro ed Otranto, at paragraph D , folio XVIII);

- p. 20: W estern shore of the Adriatic: sei vedute tutte manoscritte, quattro su Brindisi e due su Otranto, levata il16 9bre 1817, levata il269bre 1817, levata il 25 9bre 1817, levata il13 9bre 1811 (the last two relate to O tranto);

- p. 21: Western shore of the Adriatic: four landscapes, one of which bears a handwritten inscription, relating to Vedute del Porto di Brindisi e del suo castello di Mare, which are, in fact, two landscapes from a single long folio (104 x 855 cm), each of which is marked: levata il11 9bre 1817. On the left hand one appears the inscription: From the Neapolitan, Austrian and English Cooperations and it is signed by W H.

Sm yth; on the right hand one, apart from a stamp and the ink stamp of the Milicary Geographic Institute, is wrirten: Vidi Meiland am 3ten Juin 1820 Campana and in another hand, Barone Grenzenstein 1 0 Tenente de' Corazzieri rileviJ;

- p. 22: Western shore of the Adriatic: five landscapes, three of which bear the handwri tren inscriptions: Costa cla Gallipoli al Capo, levata il 39bre 1817; Costa verso Carovigno ed Ostuni, Levata il giorno 25 novembre 1817, Costa verso la citta di Barletta, Levata il g.no 28 9bre 1817

. FOGLIO D' INSIlEME

. '. ... . ' ·' ,y"8"l1i c~~rCl!j~oAAh,· , . " . . . . p«-o:r~T-v 'r""'~. ~ ', r.c,g;;~ei, O",~~:.

~ca.p.,.e....,.~o ()i" PROVlNCIA .(1'1'0k90 3~ IJISIR.8IT()

C"1' otwr':l 0 3v ClllCoNDAI\IO

omune unietJ . Villa(gf .. '. T~fte .. a.tdlo e }'orte .-. Tek&;-n.£o

• C«rofu.o~o air 'I\OVDI'CIA..

• e"l'.b3, bv Di.""", • &p,t...~. ~" c.:,,,,~u. o Cl'~ • (,,,#At • r.,,., . . '" Ci .... ftrtific.t. \ ~1!1.,u.r.

1If Cufdt" "F"rU-

:.. ~t~~W pt.i.t ~~l~~ot.t\. 3v "t.~lI "" (l,K«J~,i4 ft.\.. ~cw~ ai,..2~ t~o ' ------~--------~~-

E.e,.urt. nel Reole Offie.i~ Topolrafie,. N .. poii 1334.

~--,~ ~"

(Cc~~. ' ;:~i~~L~ ~ -_/C~'" SH;":'~ VC ) "---

fig. 14

C.J1PS !fT.J1JrIQ,A";'f"@ %'0 J'J@K(J)jp>(J)~I "---------------

",Jfi'tJUt ,1taUlln iilOClllltClli».

a-u"":'Jl"ito -- --:;;"I-aai-rii'iff/ld "s CAPT. W.H:SJlfYI.E~.R.N KSP

"-._-----_._.--TWE SOUNOINOS ARE I N FATHOMS

fig. 15

.Jl.Iaro ";

(I,1i1'(" lV"CcdJ U 1r4 (" J'ba:o l~rr~' ;;

14. Title of the fifth and last sheet of the

South East Coast of Italy, published in

1828 after Italian documents' (Private

collection).

Detail of the Terra d'Otranto Coast ftom

the sheet number five of the South East Coast of Italy, where Italian documents,

i. e. Neapolitan charts, were firstly used by

the English in tracing the coastline of the

Adriatic Sea (Private collection).

VLADIMIRO VALERIO

fig. 13

Title of the Carta di Cabotaggio della Costa del Regno delle Due Sicilie, publi

shed in Naples in 1834, in 13 sheets in

scale 1: 100,000 (Private collection).

/477

MAP PJE ANTIQUJE

478 I

Conclusions However, the charting of the Adriatic remains a task which is in some ways a paradigm of the modern hydrography of the nineteenth century: marine space was receiving fresh attention of a different kind, both in relation to its more abstract or less perceptible aspects, and to the location coordinates calculated astronomically or geodetically, and measured also by an intensive use of chronometers, as we know from Captain Smyth's memoirs, in map projection, producing a Mercator map centred on the central parallel, or the soundings of the sea bed such as enabled its quality to be known, so as to enable safe anchoring. In this way the informative quality of the map is important in topography, as is indicated by the adoption of the high scale of 1: 175,000 (on the central parallel in a Mercator projection) for linking the urban details represented on a scale varying from 1: 1 0,000 to 1 :40,000. These figurative models, or rather, the new perceptions and the new requirements for depicting territory and maritime landscapes formed the basis for the entire European hydrographic output of the whole century.

Bibliography Astengo, Corradino. 2000. La cartografia nautica mediterranea dei secoli 16 e 17 Genova: Erga Edizioni. Borges, Jorge Luis, and Adolfo Bioy Casares. 1973. Racconti brevi e straordinari. Parma; Milano. Camp bell, Tony. 1987. Portolan Charts from the Late Thirteenth Century to 1500. In History of

Cartography, vol I: Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean, edited by J. B. Harleyand D. Woodward, 371-463. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1987.

Dubbini, Renzo. 1994. Geografie dello sguardo: Visione e paesaggio in eta moderna. Torino: Einaudi. English edition translated by Lydia G. Cochrane: Geography of the Gaze: Urban and Rural Vision in early Modern Europe, 2002.

Eco, Umberto. 1983. Dell'impossibilira. di costruire la mappa dell'impero 1 a 1. In Hic sunt Leones: Geografia fantastica e viaggi straordinari, a cura di Omar Calabrese, [et al.]., 84-86. Milano: Electa.

Edgerton, Jr., Samuel Y. 1975. The Renaissance Rediscovery of Linear Perspective. New York: Basic books. Edney, Matthew H. 2005. The Origins and Development of! B. Harley's Cartographic Theories,

Cartographica; vol. 40, no. 112 = monograph 54. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Fiorentini, Erna. 2005. Practices of Refined Observation the Conciliation of Experience and Judgement

in John Herschel's Discourse and his Drawings. In The Osmotic Dynamics of Romanticism: Observing Nature - Representing Experience 1800-1850, ed. Erna Fiorentini, 15-37. Preprint; Nr. 304. Berlin: Max-Planck-Institut fur Wissenschaftsgeschichte.

Harley, J. B. 1975. Ordnance Survey Maps: A Descriptive Manual Southampton: Ordnance Survey. Nordenskiold, A.E. 1897. Periplus: An essay on the early history of charts and sailing-directions. Stockholm:

Norstedt (Reprint: New York: Burt Franklin, 1967]. Owen, Tim, and Elain Pilbeam. 1992. Ordnance Survey: Map Makers to Britain since 1791, Southampton:

Ordnance Survey. Seymour, W A. (ed.) 1980. A History of the Ordnance Survey. Folkestone: Dawson. Smyth, William Henry. 1854. The Mediterranean: A Memoir Physical Historical and Nautical London:

Parker. Valerio, Vladimiro. 1987. Dalla cartografia di corte alIa cartografia dei militari: aspetti culturali, tecnici e

istituzionali. In Cartografia e istituzioni in eta moderna: Atti del Convegno : Genova, Imperia, Albenga, Savona, La Spezia, 3-8 novembre 1986, 59-78. Roma: [so n.] (Pontedecimo, Genova: BrigatiCarucci).

Valerio, Vladimiro. 1993. Societa Uomini e Istituzioni cartografiche nel Mezzogiorno dltalia. Firenze: Istituto geografico militare.

Valerio, Vladimiro (ed). 1995. Ferdinando Visconti, Carteggio 1818-1847 Firenze: Olschki. Valerio, Vladimiro. 1998. Cognizioni proiettive e prospettiva lineare nell' opera di Tolomeo e nella cultura

tardo-ellenistica. Nuncius: Annali di storia della scienza 13, 1: 265-298. Valerio, Vladimiro. 2002. Costruttori di immagini: Disegnatori, incisori e litografi nell'Officio Topografico di

Napoli (1781-1879). Napoli: Paparo. Valerio, Vladimiro. 2003. Locchio mutevole: militari e mappe tra rivoluzione e restaurazione. In La carto

grafia europea tra primo Rinascimento e fine dell'illuminismo: Atti del Convegno internazionale The making of European cartography, Firenze, BNCF-EUL 13-15 dicembre 2001, a cura di Diogo Ramada Curto, [et al.], 229-244. Firenze: Olschki.

Valerio, Vladimiro. 2005. Cartography, Art and Mimesis. The Imitation of Nature in Land Surveying in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. In The Osmotic Dynamics of Romanticism: Observing Nature - Representing Experience 1800-1850, ed. Erna Fiorentini, 55-78. Preprint; Nr. 304. Berlin: MaxPlanck-Institut fur Wissenschaftsgeschichte.