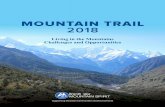

Land Scrip as Neoliberal Aboriginal Governance: The Métis 'Trail of Tears'

Transcript of Land Scrip as Neoliberal Aboriginal Governance: The Métis 'Trail of Tears'

Mac Cassia 2015/03/20

Land Scrip as Neoliberal Aboriginal Governance: The Métis 'Trail of Tears'

(Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of BA.Soc.Sci, University of the Fraser Valley)

~Advisor: James Hutchinson, Ph.D.~

“The history of scrip speculation and devaluation is a sorry chapter in our nation’s history.” -Supreme Court of Canada, R. v. Blais [2003]

-dedicated to the relatives I have never met-

The case of Canada's Métis is a unique one in many regards. Historically, it stands to date as

one of the few instances of armed resistance to colonial praxis by the descendants of those settlers sent

to enact a colonization of territory, representing one of the earliest instances of 'mutiny' from within

what empire had previously considered its own ranks¹. Sociopolitically, the resistance of the Métis

people marked forcefully the distinction between settler and colonizer, challenging on a fundamental

basis the doctrines and ideologies of romantic nationalism upon which both the French and British

empires were founded, and confounding the basis of ascribed racialization by which their social

institutions operated. Accordingly, the Métis have alternately been vilified as traitors, dismissed as

social malcontents, and romanticized to one externally-imposed tune or another throughout much of

Canadian historiography, in retrospect presenting a particularly perplexing and intricate case study of

social exclusion. Furthermore, it is said that desperate times call for desperate measures, and it is the

contention of this researcher that through the extreme and unique case presented by Métis resistance,

the colonial Canadian state was (of desperation) forced to take extreme and unique measures; measures

which in retrospect hold many lessons for those who struggle against the colonial state today.

While many Canadian historiographies, and certainly general public perception, conceive of the

Métis having originated as a nation in the area of Manitoba's Red River Valley through the

establishment of provisional government under Riel, this assertion (implicit or otherwise) reflects

merely the emphasis which colonial academe places on the exercise of military force, rather than any

historic reality. The 'civilization' of the Métis (i.e. the undertaking of assimilative endeavours against

¹ My advisor has requested clarification of this assertion, which I am happy to provide: while there are those among the pure laine of Québécois society who would deny entirely the descent of the Métis from their stock, this bois brûlé cannot bring himself to accept such a disingenuous assertion, nor does the evidence support it. My own family were among the first to marry filles du roi on this continent, yet fought valiantly nonetheless against the colonial state (to which the 'pure laine' lent their support in the occupation of our lands).

them, and beginning of their community's collective negotiation of institutionalized nationhood in

response) began 51 years prior to the establishment of Riel's provisional government, with the arrival in

their territory of M. Sévère Dumoulin, one of the first three missionaries sent by Bishop Joseph-Octave

Plessis of Quebec's Notre Dame Cathedral to aid in the establishment of a colony at Red River. The

colony in question was that of the now-infamous 'Lord Selkirk' (Thomas Douglas, the 5th Earl of

Selkirk), and the so-called “apostolic canoe” (Voisine, 1985, para. 4) containing M. Dumoulin and his

compatriots (Abbé Joseph-Norbert Provencher, and seminarist William Edge) was sent at the petition

of its residents (indigent Scottish farmers whom Douglas had imported as serfs). Officially established

in 1811 through the issuance of the 'Selkirk Concession' to Douglas by the Hudson's Bay Company (a

land grant of eminently dubious legal status, given that HBC at no point held any legal title to the lands

negotiated in this document, and that Douglas was in fact a partial owner of HBC at the time of this

issuance), the Selkirk Colony was soon to become ground zero of the struggle between the colonizer

and colonized of Canadian history.

Despite the presumption of King Charles II in granting charter (essentially a colonial guarantee

of trading monopoly) to the HBC in 1670 over the territory of 'Rupert's Land' (an area defined by the

drainage basin of Hudson Bay), this territory remained largely unceded by its residents, a mix of

Nêhiyawak (Plains Cree), Métis (or O-tee-paym-soo-wuk as the Cree later named them), Siksikaitsitapi

(Blackfoot), Nahkawininiwak (Saulteaux), Nakota (Assiniboine), Dakota (Sioux), Denesuline

(Dene/Chipewyan), and Tsuu T'ina (formerly 'Sarcee') Peoples who traded freely with both the HBC

and their rivals, the North West Company, as independent nations. Prior to the issuance of the Selkirk

Concession, little if any attention was paid to legal fictions imposed from across the sea (such as the

HBC's Charter monopoly) by these Peoples in the conduct of their economies, yet the conflict between

their major trading partners (the HBC and NWC respectively) soon made this an impossibility. There is

little doubt that a great deal of the motivation behind Douglas' location of the Selkirk Colony was

strategic, as it was situated square astride the trade routes of both the NWC, as well as the emerging

entrepreneurial class of Métis coureurs des bois (or 'runners of the woods', who acted as unlicensed fur

traders in their own right), both of whose activity challenged the Charter monopoly of the HBC and

therefore endangered the dividends of Douglas' own investment in this firm. Additionally, the

introduction of agricultural development in the area of the proposed Selkirk Colony held significant

potential to disrupt the Red River buffalo hunt; the primary food source of this region's Indigenous and

Métis inhabitants (as well as the primary source of pemmican, a trade staple of the Métis People

without which the remote trading posts of the NWC could not function). Essentially, while clothed in

the language of a charitable, or 'civilizing', venture, the establishment of the Selkirk Colony amounted

to nothing more or less than a military (and in this researcher's opinion illegal) act of expropriation and

occupation, and one that initiated nearly a decade of armed resistance from the Indigenous and Métis

inhabitants of this region.

On August 30th of 1812 (Matheson Henderson, para. 9), the first coloni (to borrow a turn of

phrase from the aristocratic Latin of the time) of the Selkirk Colony arrived, escorted by Miles

MacDonell (a career military officer who had been enlisted by Douglas and the HBC to serve as

Governor of their proposed installation). Shortly afterwards, on June 18th of 1812, the United States

declared war on Canada, and the Anglo-American War of 1812 erupted in earnest with the invasion of

Sandwich, Ontario (now a suburb of Windsor) by the American forces of William Hull (as recounted by

Rauch, 2012, p.1, para. 1). As the land on which they lived was invaded (the Great Lakes region, in

which the majority of key battles in this conflict were fought, and where the Métis existed in great

number), it is clear that the Métis participated in its defence. Indeed, several historic militias of this

conflict, such as the Corps of Canadian Voyageurs, the Mississippi Volunteers, and the Michigan

Fencibles, were comprised primarily of Métis warriors, and it is said that “most (although not all) Métis

fought on the Canadian side during the war”, fighting “in most battles [...] as part of militia units or

beside First Nations” (Métis Nation of Ontario, 2014, para. 4). It is equally clear, however, that the

British theft of land embodied in the establishment of the Selkirk Colony was met with no less

resistance than was its attempted theft by U.S. invasion. It is well-documented that following the Treaty

of Ghent (signed on December 24th, 1814, which effectively ended the War of 1812), the Métis

commenced guerilla tactics against this installation, on numerous occasions forcing its occupants to

flee for Jack River in the north (an HBC stronghold near which the town of Norway House was later

constructed), and for the community of Pambian in the south (at which Fort Daer was constructed

specifically for their refuge by the HBC, near the site of what has now become Pembina, North Dakota)

in retaliation for the issuance on January 8th, 1814 (Amos, 1820, para. 2) of the 'Pemmican

Proclamation' (banning the export of foodstuffs from the Red River territory) by Miles MacDonell, and

subsequent assumption of policing jurisdiction by colony officials over Métis communities (including

the seizure of foodstuffs as well as other property, and imprisonment of community members).

Emboldened by their rout of the U.S. invasion, and now schooled in the doctrine of military exclusion

practised by their colonizers, the Métis responded to the militancy of MacDonell's proclamation in

kind, and (as John Pritchard, one of the Selkirk Colonists wrote) “immediately began to burn our

houses in the day time and fire upon us during the night, saying the country was theirs, [...] if we did

not immediately quit the settlement they would plunder us of our property and burn the houses over our

heads” (CBC, 2001, A people's history: Battle at Seven Oaks, para. 11).

After two years of conflict between the Métis and the Selkirk Colony, matters came to a head on

June 19th, 1816, at the Battle of Seven Oaks. 25 armed colonists under the command of Robert Semple,

the Governor of the HBC at this time, confronted a group of 61 “Métis and Indians” (ibid., para. 12).

21 were slain--including Semple himself--and the remaining colonists fled the Selkirk Colony the

following day (a victory commemorated in La Chanson de la Grenouillère by Métis poet Pierre Falcon,

which has now served as an unofficial anthem of the Métis for more than three generations). It was to

this contested territory, two years after the Battle of Seven Oaks, that M. Dumoulin and his compatriots

first arrived, establishing the St. Boniface Cathedral on a tract of land provided by Douglas opposite the

mouth of the Assiniboine River, where Provencher was to remain, preaching from this base. Notably,

both Douglas and MacDonell (as noted by Grace Lee Nute, and quoted by Duval, 2001, p. 3, para. 1)

believed that “previous attempts to establish a permanent colony at Red River” had “been subverted by

the Métis inhabitants of this area”, attributing perhaps in no small part of the decision of a Scottish

Protestant such as Douglas to facilitate the missionary work of French Catholics such as Provencher

and Dumoulin in the area (likely at the behest of MacDonell, whose background from a distinguished

Catholic military family—as reported by Mays, 2003, para. 2—would have schooled him in the finer

points of religion and colonization, who would doubtless have realized the potential of its application

given the context, and whose background similarly afforded him the social capital to make such a

request of the Catholic Church). Dumoulin however, in contrast to the praxis of both Plessis and

Provencher, was of the belief that the conversion of Indigenous Peoples would be more readily

achieved “if one could manage to gather them into villages” (Voisine, 1985, para. 4), and departed two

months before the inauguration of the St. Boniface Cathedral for the southern community of Pambian

(as reported by Lemieux, 2003, para. 9).

Whereas the methodology of Provencher mirrored closely that of the colony in which he had

been stationed, issuing dictates and coordinating patrols from a central stronghold, that of Dumoulin

was demonstrably more dialogic in its emphasis upon the institutionalization of community. In

Pambian (so named in Michif, the Métis creole dialect, for the high-bush cranberries which they

harvested there annually, and dried for the making of pemmican), Dumoulin encountered what

acclaimed historian Joseph Kinsey Howard has termed (in his swan song opus, Strange Empire) “the

first capital of [...] the Métis [...] in so far as a people who have always shunned settlements could be

said to have had a capital” (1952, p. 28, para. 4), and there, through dialogue with its inhabitants,

the first recorded history of the Métis in which they had a voice (albeit at times one distorted and/or

marginalized in translation) began through Dumoulin's establishment of the first Métis church, “whose

diocesan boundaries (ignoring such political fictions as the forty-ninth parallel) were officially the

Great Lakes, the North Pole, and the Pacific” (ibid.).

Volume 11 of the Catholic Encyclopedia states that “the establishment of Catholic missions in

North Dakota cannot be reliably traced to an earlier date than 1818” (Herbermann, Pace, Pallen,

Shahan & Wynne, 1911, p. 135, para. 4), clearly indicating that Métis culture predates the introduction

of Catholicism to their territory by this venture, and the diocesan boundaries established by Dumoulin

in dialogue with the Métis community clearly indicate a claim of land use by this culture which

conflicts with the colonial record. Indeed, while the Métis culture as it exists today is said to have

developed through the intermarriage of Indigenous Peoples and European settlers in the course of the

fur trade, reasonable doubt persists that the first Métis (that is peoples of mixed indigenous and settler

ancestry) may in fact predate European contact entirely, on the grounds that the now-infamous

Kensington stone (purporting to tell the tale of a Norse survivor whose expedition had been slain by

Indigenous Peoples in 1362) as well as most of “more than a dozen other [Norse] relics such as swords,

axes and mooring stones for boats [...] have been found in the Red River Valley” (Kinsey Howard,

1952, p. 29, para. 4)--evidence supported in some degree by the existence of Canada's L'anse Aux

Meadows archaeological site (the remains of a Norse village located in the Labrador Peninsula,

conclusively demonstrating pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact by nearly half a millennium)--and it

is (in any case) undeniable that the Métis culture and people predate the 1670 issuance of HBC charter

by the British Crown over 'Rupert's Land', as it is well-documented that by the time of this

proclamation that the forests of the pays d'en haut (or 'upper country' as the French termed the territory

West of Montreal, within which 'Rupert's Land' fell) were “filled with illegal coureurs des bois” (Jung,

1997, para. 11) of both French and Métis ancestry.

At this juncture, before proceeding from the community of Pambian in the historiography of

Métis nationhood, it is appropriate to contextualize the process and product of social exclusion from

whence this nationhood was born. As 'halfbreed' peoples, while possessed of ancestry linked to both

the French Empire and Canada's First Nations (primarily the Nêhiyawak and Siksikaitsitapi initially, by

most accounts), they have historically been privileged to the acceptance of neither. Viewed with

suspicion by the predominantly patrilineal societies of their mothers, whose marriage outside of this

kinship structure (for a variety of reasons, as postulated by Jung, 1997, para.s 14-40) had technically

disowned their offspring, and with equal suspicion by the colonial society of their fathers, whose

marriages after la façon du pays (or the 'custom of the country') frequently rendered their offspring

illegitimate in the eyes of its ruling theocrats (as detailed by Jung, ibid., para. 34), the Métis (who

would in any case have been viewed with suspicion by the French Empire on the basis of their descent

from a 'subject race') were effectively displaced at birth. While it is known that Métis warriors

frequently fought alongside the Indigenous Peoples of Canada in conflicts, and that (at least among the

tribes of the Great Lakes) “the biracial children from French-Indian unions were not treated any

differently than full-blooded Indian children” (ibid., para. 38), indicating harmonious and cooperative

relations between the Métis and their indigenous ancestors, the displaced status of the Métis within the

kinship models of these societies did not entitle them to any inheritance of stewardship over hunting

territory; doubtless a contributing factor to the establishment of the Great Lakes as the Eastern

boundary of the territory encompassed by the claim which Dumoulin first documented. Similarly, while

it is known that the Métis traded extensively with the NWC, by which many of their fathers were

employed--no small contributing factor to the Battle of Seven Oaks, which by many accounts was

partially incited by NWC agent Duncan Cameron's admonition that “if they [the Selkirk Colony] are

not drove away, the consequence will be that they will prevent you from hunting [...] will starve your

families, and [...] will put their feet in the neck of those that attempt to resist them” (as reported by

CBC, 2001, para. 9)--they were neither welcome in the settlements of New France, nor accorded any

form of citizenship by the French.

Grace-Edward Galabuzzi, one of Canada's leading scholars on the subject of social

exclusion,summarizes its key aspects as “denial of civic engagement through legal sanction and other

institutional mechanisms”, “denial of access to social goods [such as] health care, education [and]

housing”, “denial of opportunity to participate actively in society”, and “economic exclusion” (2007, p.

4). From this definition, it is clear that such a state of affairs may be said to characterize the

historiography of the Métis in relation to the development of the Canadian state. While socially

accepted by the societies of their indigenous progenitors (barring strained relations such as those which

occurred between the Dakota and Métis over hunting rights during the 1840s), the Métis (as

matrilineate relatives to predominantly patrilineal societies) could not rightly be considered citizens of

these nations; as such denied the privileges of citizenship in terms of civic engagement and economic

privilege (while remaining entitled to access social goods). On the settler side of their ancestry this

situation was largely mirrored, although the issue of access to social goods became considerably more

complex. As evidenced by Jung's characterization of the coureurs des bois as “illegal”, and by the

specifics of the 'Pemmican Proclamation' discussed earlier herein, it should further be noted that the

economic exclusion which the Métis experienced at the hands of the British far outstripped in

magnitude any which they had been subjected to at this point, verging upon attempted enslavement.

While the Métis were fortunate in that many of their fathers possessed at least partial education in the

ways of the colonizers, allowing for instances of private literacy education in the home, formal

education remained a privilege in their communities accessible to a select few, primarily the sons of

settlers with sufficient capital as to have their children educated abroad, or later those who were

selected for induction to the priesthood by Catholic missionaries. Cuthbert Grant, who led the Métis at

the Battle of Seven Oaks, constitutes one early example of the former, born to an NWC partner and

sent abroad during his formative education. Louis Riel, while not possessed of such fortunate lineage,

constitutes an example of the latter, selected at age 13 by the Suffragan Bishop of St. Boniface

Cathedral for instruction (under the direction and patronage of the Sulpician Order) at the Petit

Séminaire of the Collège de Montréal.

While examples of the former sort predate the 'civilizing' efforts of M. Dumoulin at Pambian,

and subsequent assumption by the Catholic Church of a role as “the self-appointed 'official' voice of the

Métis” (Duval, 2001, p. 2, para. 2), the seminomadic nature of Métis culture rendered the

institutionalization of education (as it is recognized in the European tradition) largely an impossibility

within its communities. Pambian, while a place of annual gathering for large numbers of Métis and

integral territory to the seasonal round of their traditional lifestyle, did not constitute a permanent

settlement such as would be required to support schools of the European tradition. It was through the

efforts of M. Dumoulin's unconventional praxis, and through the adaptive capacity of Métis culture,

that the first agricultural settlement of the Métis was established there, and the first school of the Métis

people opened. Coincidentally, the efforts of M. Dumoulin were also to form a blueprint of assimilation

which has recurred throughout colonial Canadian history, rendering the Métis in a very real sense a

precursor of those assimilative endeavours later enacted against Canada's Indigenous Peoples, and a

canary in the metaphorical gold mine of colonialism.

Despite the efforts of M. Dumoulin, however--which marked the only appreciable success of the

Catholics in the conversion of the Métis prior to the 1830s, indelibly affecting the course of this

nation's sociopolitic evolution—his mission had been compromised from the start by precisely those

“political fictions” which both his parishioners, and his diocesan boundaries, soon stood in conflict

with. The 'Convention respecting fisheries, boundary and the restoration of slaves', signed in London

on October 20th of 1818 (U.S. Department of State, 2007, para. 12) between the U.S. and Britain

effectively bisected the territory of the Métis, appropriating the crucial region of Pambian in its

establishment of the 49th parallel as an international boundary. This appropriation went unrecognized

by the Métis at the time, who appear to have gone about their daily business unfazed by (if indeed

aware of) its occurrence during Dumoulin's tenure, but was to constitute an early example of 'divide

and conquer' with profound ramifications in retrospect. By the 1820s, the continued warfare of the

Métis against the Selkirk Colony had left it virtually abandoned, and following the death of Douglas

(its driving patron) in 1820, a merger was forced between the NWC and HBC in 1821, marking the

cessation of hostilities between the two, and commencement of hostilities by the monolithic entity of

capital against Canada's indigenous population in earnest. In 1823, Dumoulin was recalled by

Provencher from Pambian (at the behest of John Halkett, administrator of Douglas' estate), and left the

northwest entirely in 1823 (as reported by Voisine, 1985, para. 6) rather than returning to the Selkirk

Colony. For their part, the Métis were now effectively entrapped. Their capital city, including all the

infrastructure of their fledgling society, had now been ceded against their consent and without their

prior knowledge, to the U.S., erecting a barricade of military resistance to their access thereof, and their

coureurs des bois--the backbone of their participation within the Canadian economy—were now

persecuted by all European fur traders, stripped of what little protection their alliance with the NWC

against the HBC had afforded them.

While the merger meant that the Métis, who had previously been associated with the NWC in

the minds of the HBC, were now eligible to seek employment within its organization, the experiences

of noted Métis such as Alexander Kennedy Isbister (the first Métis to have received a law degree)

illustrate a pattern of discrimination against those Métis who did so (as reported by Van Kirk, 1982,

para. 3), which the monopolistic reality of the HBC/NWC merger left them little recourse to. Similarly,

while the Métis were accorded representation on the Council of Assiniboia (formed in the wake of the

HBC/NWC merger as the governing administrative body of 'Rupert's Land')--primarily through the

personages of Pascal Breland and James McKay--this representation was marginal at best, and the

Council was dominated by men such as John Sutherland (who later fought against the Métis in the Red

River Rebellion, and whose son Hugh was in fact to become the first casualty of this conflict). After 48

years of this enforced subjugation, matters again came to a head between the Métis and their

colonizers, following the sale of their entire territory (or perhaps more accurately the relinquishment

of the HBC's charter in this region to the British crown in exchange for a sum of £300,000) from

beneath their feet, again against their consent and without their prior knowledge, including every man,

woman and child on it, after the manner of furniture (as indeed Thomas King characterizes the

dominant paradigm of relations between between the colonizer and colonized of this period on p. 82,

para. 3 of his 2012 work, The Inconvenient Indian). The Council of Assiniboia, on which the Métis had

been afforded at least marginal representation was effectively dissolved, and anglophone autocrat

William McDougal was installed by the British in its place, touching off more than a decade of armed

resistance. The incidents of October 11th, 1869, on which Riel, backed by more than a dozen Métis,

repelled the surveyors of McDougal whilst standing atop their survey chain (at the farm of his cousin,

André Nault, as reported by CBC, 2001, A people's history: The capture of Fort Garry, para. 7) have

become common knowledge among Canadians, as has the execution of Thomas Scott by Riel's

provisional government—the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia, formed in replacement of the

Council of Assiniboia (the dissolution of which many Métis considered a betrayal)--yet the events

leading to Scott's eventual execution are far less well-known.

On February 15th, 1870, following the establishment of the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia,

and the repulsion of McDougal's surveyors, the first blood of the Red River Resistance was spilled. A

young Métis named Norbert Parisien--described by his contemporaries as “simple-minded” (Bowsfield,

1976, para. 1) and employed at Upper Fort Garry chopping firewood—was set upon by members of the

Canadian party, led by Scott (as reported by the University of Manitoba, 1998, para. 2), severely

beaten, and imprisoned. In fear for his life Norbert Parisien escaped, seizing a weapon from his

captors in the process and fatally wounding Hugh Sutherland (who had sought to bar his path).

Enraged, Scott's men succeeded in recapturing Parisien, who they summarily lynched (albeit

unsuccessfully) with his own sash (or l'assomption as it came to be known among the Métis, a primary

signifier of their culture) by dragging publicly behind Scott's horse (as acknowledged by both sides

of the conflict, ibid., para.s 4, 6). Two days later, on February 17th, Fort Garry was seized and 50

members of the Canadian party, including Scott, were taken prisoner by the Métis in retaliation. On

March 4th, Parisien died of his wounds (as reported by the Manitoba Historical Society, 2014, para. 1)

and Scott was executed, not (as many colonial historiographies have implied) for his beliefs (nor for the

charge of 'interfering with the provisional government' on which he stood trial along with John Boulton

and William Gaddy--both pardoned), but rather for his role in the torture and murder of an innocent

man with the intellect of a child.

Following Scott's execution--and ignoring wholesale the murder of Parisien--the Canadian state

seized upon this opportunity to deploy the Wolseley Expedition (a military force of some 1200 men)

against the Métis, driving them from Fort Garry (the structures of which the Métis abandoned on

August 24th, 1870 upon their advance) and leaving behind an occupying force of approximately 800

to “garrison the community” (as reported by Beal, 2013, para. 3) in a move of classical gunboat

diplomacy designed to police (i.e. subjugate) the Métis population of this region (which outnumbered

European settlers by more than six to one, as indicated by the 1870 census of the North-West Territories

and Manitoba which Anderson, 2006, cites in para. 4). Following this occupation, the social exclusion

of the Métis continued unabated, and they were subjected to systemic and systematic “militia

harassment” at the hands of the Canadian state apparatus, including “assaults” resulting in “at least one

death” (Beal, 2013, para. 3). As an occupied nation, the Métis were left little choice but to accept the

terms of the Canadian state, which had been delivered by Alexandre-Antonin Taché, Joseph-Noël

Ritchot and John Black (as reported by Augustus, 2008, para. 8) prior to the surrender of Fort Garry,

and would now constitute the basis of the Manitoba Act, and which this researcher contends to have

been the first historic instance of a colonial tactic which political scientist Fiona MacDonald has most

recently identified as “neoliberal aboriginal governance” (2009, para. 1).

While the terms of the Manitoba Act (owing primarily to the influence of Ritchot, who had

accompanied Black and Taché so as to represent the Métis, and had in fact initially been arrested for

complicity in the death of Scott upon his arrival as recounted by Mailhot, 1994, para.s 4-5) appear

honourable in theory, recognizing under section 31 a Métis entitlement of 1.4 million acres of land in

addition to guaranteeing (under section 32.4) “peaceable possession” to all settlers, of Métis or

European ancestry, of the “tracts of land” which they had occupied “at the time of the transfer to

Canada [stipulated within as March 8th, 1869]” (Solon Law Archive, 2000), its application was to

prove another matter entirely. The “peaceable possession” of section 32 was guaranteed only “on such

terms and conditions as may be determined by the Governor in Council” (ibid.), rendering it little more

than farcical lip service in the wake of military occupation (as evidenced by the systemic harassment

and assaults previously noted to have accompanied the arrival of the Wolseley Expedition), and the

scrip process by which the Canadian state proposed to distribute the Métis entitlement of land (its

primary mechanism of enforcing neoliberal aboriginal governance in this region), while ratified in

1870, did not commence until 1876 (as reported by Augustus, 2008, para. 10), leaving the Métis

essentially without legal rights and at the mercy of their occupiers for a period of six years following

the recapture of Fort Garry. As the buffalo of the great plains dwindled, the Métis remained subject to

the enforced economic exclusion which had characterized their earlier relations with the British (which

has been documented herein, and if anything intensified following the hostilities of 1870), and the

agricultural techniques learned from M. Dumoulin (as well as land requisite to make use of these

techniques) became increasingly necessary to supplement their livelihoods. Additionally, it should be

noted that the Métis were no more immune to the germ warfare of the colonizer than were their

indigenous relatives, and that the smallpox epidemic of 1869-1870 (corresponding to the occurrence of

the Red River Resistance) “killed at least a third of all First Nations and Métis people it infected”

(Binnema, 2006, p. 128, para. 3), including “more than a third of the population of the Métis settlement

at St. Albert” (as reported by the University of Alberta, 2009, para. 2). 59 years of colonization had

taken their toll, and the uprising at Red River had been the act of a people already forced to desperation

by its manoeuvres. Six years of starvation, disease, and outright military occupation, without any

guarantee of a future beyond the assurances of their occupiers, proved too much for for many Métis to

stomach, and the years following 1870 saw a mass exodus of their people from the Red River Valley.

This was the beginning of the Métis' trail of tears, and many families fled west, settling along

the Southern branch of the Saskatchewan River in the already-established 'Southbranch Settlements' of

Tourond's Coulee, Batoche, St. Laurent, St. Louis, and Duck Lake, as well as in the smaller

communities of Ile-à-la-Crosse, La Loche, Lac-de-Boeufs, Lac-Vert, Beauval and Lac-des-Prairies

(trading posts around which the first Métis communities of Saskatchewan had formed), Chimney

Coulee, Lac-Pelletier, Vallée-Ste-Claire, Montagne-de-Bois, and La Prairie Ronde (Anderson, 2006,

para.s 4-5, 7). Some travelled as far as British Columbia, while still others dispersed further to the

North and South, settling in areas of what are now the North West Territories, North Dakota, and

Montana, as well as in the 'Half Breed Tracts' which had previously been negotiated South of the 49th

parallel alongside the Sac Fox, Osage, Chipewyan, Dakota, Otoe, and Delaware Peoples of Iowa,

Missouri, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Nebraska and Kansas (as reported by Barkwell, 2014, para.s 6-10,

12). Sadly, those Métis to flee their British oppressors were slowly legislated out of existence by the

American state which claimed these lands, a precedent set by by the 'Ten Cent Treaty' (or 'McCumber

Agreement') of 1892, which bears striking resemblance to the terms of the imposed terms of the

Manitoba Act. Negotiated jointly between the Red Lake Chipewyan, Pembina/Turtle Mountain Métis,

and U.S. government—and so named for its coerced purchase of 10 million acres of land in exchange

for 1 million dollars—this treaty was ratified in 1904, and was negotiated on the behalf of “1,739

mixed-blood and 283 full bloods”, excluding another “1,476 mixed-bloods, many of whom were

considered to be Canadian Métis” (ibid., para. 20) so as to guarantee each private allotments of 160

acres (an identical sum to that offered the Métis under the terms of the Manitoba Act), thereby legally

extinguishing their collective aboriginal title (as the Manitoba Act explicitly states to be its purpose

under section 31) in exchange for conditional private title (as is congruent with the methodology of

neoliberal aboriginal governance). Similarly to the Manitoba Act, this treaty was also deeply flawed in

implementation. Only a few of the allotments (which fell within the pre-existing boundaries of the

Turtle Mountain Reservation as reported by Barkwell) were delivered upon the treaty's ratification, and

the remainder were withheld until 1943, when the American state's hand was forced by “a huge

scandal” pursuant to “numerous deaths of band members through starvation” (ibid.), and the band of

Chief Little Shell (who had retreated to the Montana territories following this betrayal in the pursuit of

their traditional lifestyle) were excluded entirely again (existing landless there to this day).

The methodology and aftermath of the 'Ten Cent Treaty' are instructive, insofar as they illustrate

in microcosm a reflection of the methodology and aftermath of the imposition by the Canadian State of

the Manitoba Act upon this region's Métis. Scholars Dorion & Préfontaine frame the situation thusly:

“The end result of the Red River Resistance of 1869-70 was that the federal government was forced to extinguish the Aboriginal resident’s Indigenous title to the land before settler society [read: European colonization] could develop. This meant going back to the principles of the 1763 Royal Proclamation, which maintained that before settlement of lands in North America inhabited by Indigenous peoples could occur by British subjects, the original occupants had to have the title to the land extinguished by the Crown. For the First Nations, this meant that various treaties, the so-called 'Numbered' Treaties, were entered into with the various First Nations and the Crown, as represented by the federal government from 1873 to 1909. For the Métis and the Country Born [a term denoting those Métis born of Scottish ancestry], this meant having their Indigenous title extinguished through the Scrip System from 1870-1921” (2003, pp. 1-2).

While it should be noted that the Métis were included to some small extent in these 'Numbered' Treaties

through the “Half-Breed Adhesion to Treaty No. 3”, which “set aside two reserves for the Metis and

entitled them to annuity payments, cattle and farm implements” (negotiated by Nicholas Chatelain in

1875, on behalf of the Rainy Lake/Rainy River Métis as reported by Barkwell, 2014, para. 26), the

rights guaranteed the Métis in this treaty were not honoured for nearly 10 years following its

ratification, and then only partially in response to the second great Métis uprising, the Northwest

Resistance of 1885. Indeed, so reluctant was the Crown to acknowledge collective Métis title of lands

that upon its initial appeal “the matter was referred to Indian Affairs, who declared that they would only

recognize the Métis if they agreed to join the Ojibway band living nearby” (ibid.), indicating clearly (at

least to this researcher) a strong prurient interest by this entity in maintaining the neoliberal model of

governance which it had succeeded in enforcing upon the Métis. Historians such as Douglas Sprague

have in fact argued that “the Métis were victims of a deliberate conspiracy in which John A. Macdonald

and the Canadian government successfully kept them from obtaining title to the land they were to

receive under terms of the Manitoba Act of 1870” (as reported by Milne, 1995, para. 2), and while this

researcher would stop short of asserting “deliberate conspiracy”, he does so on the grounds that

collusion of interest to deprive marginalized peoples of their resources--so as to accumulate capital

from the difference between the value and sale prices once in possession of said resources--is not in

fact a 'conspiracy': it is the fundamental model of capitalist economics, particularly when applied on a

transnational scale (such as during the height of colonialism, or within the emerging 'global economy'

that we find ourselves faced by today).

Through the manoeuvres of the colonial state, the Métis had been effectively ensnared within

this model (via the privatized system of land ownership forced upon them in the Manitoba Act), and no

'conspiracy' was necessary in order for the inherent exploitation of this model to take its toll. According

to the statistical evidence of Mailhot & Sprague (1985)--and despite the guarantees of “peaceable

possession” contained in section 32.4 of the Manitoba Act--”550 of 938 Métis families in the 1870

census were overlooked by land surveyors between 1871 and 1873”, of which total “ 501 did not

receive patents” (as reported by Milne, 1995, para. 17), with the result that more than half of the Red

River Métis were denied rights to their own homesteads within the first years of their territory's

occupation. The scrip process (when finally implemented in 1876), was both enormously problematic

in terms of consent--given that no accommodation was made in terms of either literacy or language for

applicants (who, as a predominantly illiterate and francophone population, were thereby deprived of

their right to informed consent)--and pervasively fraudulent. The research of Emile Pelletier (as cited

by Milne) found that amongst a sample of “6267 allotments of 240 acres made under section 31” (the

larger of the two scrips issued under this treaty) “529 land grants covering 126,960 acres were sold

illegally, [...] 580 sales involving 139,200 acres were ambiguous cases”, and “590 land grants covering

141,600 acres consigned to Métis children were obtained by land speculators for resale who earned

profits for themselves of 100 percent to 2000 percent” (ibid., para. 6). In sum, these cases alone (while

representing only a sampled subsection of the total scrip issued) indicate a staggering misappropriation

of 410,760 acres of Métis land, constituting more than 40% of their treaty entitlement, and the

Manitoba Métis Federation has estimated that “as many as three quarters of [the Red River Métis] lost

their scrip through [...] fraudulent practices or through outright coercion by land speculators and

departmental officials” (as recorded by Library and Archives Canada, 2012, para. 9). Additionally--and

in contravention of section 6 of the 1871 British North America Act, which states that “it shall not be

competent for the Parliament of Canada to alter the provisions of the last mentioned Act of the said

Parliament in so far as it relates to the Province of Manitoba” (i.e. the terms of the Manitoba Act, as per

the records of the Solon Law Archive, 1995, para. 9)--the Canadian state passed amendments to this

treaty in 1873 which “reduced the number of people eligible for allotments under section 31 from ten

thousand to less than six thousand”, as well as barring “approximately 1,200 families” who had (in

accordance with the traditional seasonal round of their culture) “established a shelter on one of the

rivers of Manitoba in the winter, planted a garden in the spring, spent the summers in pursuit of plains

provisions, and returned in the fall to harvest the unattended garden” from “all chance of obtaining

patents” through amendments to section 32 (principally via 38 V. Chap. 52, as noted by Milne, 1995,

para.s 10-11), more than halving again the treaty entitlement of the Métis (which had, as previously

noted, already been more than halved by this point through the disingenuous conduct of the Crown's

surveyors) to less than approximately one quarter of that stipulated in the original terms of the treaty.

While some families (including my own) were stubborn enough to have endured six years of

military occupation combined with retroactive renegotiation in bad faith, and fortunate enough to have

remained among the conservatively estimated 25%+/- of the Red River Métis left eligible by these

retroactive renegotiations--let alone have actually received their scrip following its implementation in

1876, without being divested of it through fraud or coercion--they remained by far a minority of the

community, and an exception to the rule which the evidence presents. Even those whose persistence

and good fortune had afforded them the privilege of title found themselves cast adrift at the whim of

the market by the neoliberal governance enforced upon them, and the work of Nicole St. Onge (in her

1983 case study of the Pointe a Grouette Métis settlement) has “discovered a strong correlation

between the socio-economic status of Métis families prior to 1870 and the number of years [...]

managed to retain property after Manitoba’s entry into Confederation” (as noted by Milne, ibid., para.

27). The implementation of 38 V. Chap. 52 essentially deleted the guarantees contained in section 32.4

of 'peaceable possession', and replaced them with the legal terminology of 'occupancy'--which “was

used to bar anyone who had not made sufficient ‘improvements’ of the land” (ibid., para. 11)--and,

conveniently enough for the colonial state, now placed the burden of proof upon the Métis to prove said

'occupancy' through 'improvements' (enabling the wholesale theft of all Métis hunting lands, and

disbarring from title any Métis who dared to practice their traditional lifestyle, or indeed seek any form

of economic participation--beyond engagement in the peripheral subsistence agriculture which the

Crown required in order to support industrialization--in one fell swoop). In effect, the treaty entitlement

negotiated by the Métis (albeit under duress) became--retroactively and without consent--conditional

upon their serfdom to the British Crown.

As this methodology spread West, pursuing those Métis who had fled its onslaught, matters

again came to a head on March 24th of 1884, and after meeting to discuss the grievances of their

communities 30 delegates of the Southbranch Métis settlements voted to seek the diplomatic council of

Louis Riel (who had fled the country following the deployment of the Wolseley Expedition, and was at

this time employed in relative obscurity as a schoolteacher at St. Peter's Mission in the Montana

territories, as reported by the University of Saskatchewan, n.d., para.s 6, 9). Gabriel Dumont--who had

by this time served for a decade as the elected president of the provisional paramilitary administration

by which Métis self-governance had been conducted in the Southbranch settlements, and who is

remembered as “the last and in some ways the greatest of the traditional Métis chiefs whose status was

based upon prowess as hunters and fighters and extensive kinship networks” (Macleod, 1994, para.s 10,

2)--headed the expedition to seek Riel's council, and returned having successfully smuggled Riel's

personage across the border into Canada on July 5 th of this year, laying the groundwork of what was

to become the Métis' last stand. The speech of Dumont to his fellow chiefs on March 24th, in which

he “recounted his failed attempts to move the government and suggested that Riel was the only one

who could organize the kind of pressure necessary” (ibid., para. 15), as well as his actions following--in

that “through the summer and fall of 1884” he “appears to have left matters entirely in Riel’s hands

although he kept in touch with his activities” (ibid., para. 17)--suggest that Dumont, having failed as

peacetime chief to secure redress and anticipating conflict on the horizon, had abdicated this position to

Riel, assuming the default position (in which he had historically achieved greater success) of war chief.

This latter assertion on my part is borne out in part by the prevalent descriptions of Dumont as a

military 'leader' or 'advisor' of the Métis which abound throughout Canadian historiography, and

which--while containing a kernel of truth as is so often the case in instances of ethnocentric

misconstruance--remain tainted by the lens through which they have been viewed. The roles of war

chief and peacetime chief within Métis culture cannot accurately be understood as subordinate to one

another (as is traditional within the hierarchic European model), but should rather be considered

interdependent, contextually-defined counterparts, appointed through mutual consent after the manner

of the Métis' Nêhiyawak and Siksikaitsitapi progenitors and more closely resembling the 'bottom-liners'

of today's platformist/especifista anarchist praxis than those colonial counterparts to which they have

historically been compared.

On March 18th, 1885, Dumont was informed by Lawrence Clarke--the Chief Factor of the

District of Saskatchewan for the HBC, who has in retrospect been charged an “agent provocateur of the

1885 Resistance” by the Manitoba Métis Federation (2003, para. 1)--that “their petitions for redress

would be answered by police bullets and that 500 policemen were coming to capture them” (Charland,

2007, p. 10, para. 4). Regardless as to the veracity of Lawrence' threat, it proved a spark to the

powder-keg which the tensions of the Métis' continuing marginalization had created, and in retaliation

the Métis (under Dumont, as this threat had been interpreted an act of war based on the precedent set by

the Wolseley Expedition at Red River) “seized two stores”--expropriating “the arms and ammunition

they contained”--(Macleod, 1994, para. 18), in addition to attacking the infrastructure of the Canadian

Pacific Railway (CPR) telegraph at Clarke's Crossing and holding two of their agents hostage (as

indicated by internal correspondence archived by the Glenbow Museum, 2014, pp. 1-2). The following

day, Riel--who had been suffering Messianic delusions for some time at this point (and had in fact been

committed briefly to an asylum during his exile, ostensibly unbeknownst to those who had sought his

diplomatic council)--“proclaimed [...] provisional government” (Macleod, 1994, para. 18), replacing

the structure of traditional self-governance (under which the Southbranch Métis had conducted their

affairs for more than a decade) with his own grandiose (and suspiciously-named) exovedate scheme

(translating to 'chosen of the flock' in Latin), of which he appointed himself the supreme arbiter. On this

day, all hope of victory for the Northwest Resistance was doomed. Already scattered by their

dispossession and disadvantaged technologically by the military resources of the crown, not all Métis

supported Riel and many were wary of provoking further repression. Additionally, the status of Dumont

as war chief was only recognized by mutual consent within his own faction (the Southbranch Métis),

and his tactical decisions--in blatant contradiction of Métis custom during time of war--were now

subject to the approval of Riel, the peacetime chief, further weakening his authority and crippling his

effectiveness during a critical period. The theatre of conflict which ensued, while claiming notable

victories under the command of Dumont at Duck Lake, Tourond's Coulee and Cut Knife, played out

largely as a war of attrition (culminating in the defeat of the Métis at Batoche on May 15th of 1885): a

state of affairs which may well be said to characterize relations between the Métis and the Canadian

state well into the 21st century.

The reproduction of indigenous culture requires two base units: land, and a successive

generation. Having taken the land as best they could--in the case of the Métis dooming them to a

perpetual war of attrition against the monolithic entity of capital, the continuation of which into the 20th

century is made evident by cases such as that of the Ste. Madeleine Métis, whose “houses were burned

to the ground” and whose “community was destroyed” in 1935 (without compensation of any kind), on

the grounds that their “tax payments on the land” were not “up to date” (as recounted by King, 2012, p.

57, para. 1)--the colonial state now turned its attention against the successive generation. Between 1828

and 1996 more than “150,000 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children” were forcibly interned by the

Canadian state in residential schools (as reported by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of

Canada, n.d, para. 2), many of whom were subjected to physical and/or sexual torture, as well as

forbidden to speak their native language or practice their cultural customs in these institutions. After

being forcibly separated from their families and communities under Richard H. Pratt's now-infamous

precept that “all the Indian there is in the race should be dead” (as reported by Bear, 2008, para. 11) and

that the state must “kill the Indian'” to “save the man” (ibid.), these children were effectively held

hostage by the colonial state against the communities from which they had been removed, in many

cases under conditions tantamount to those of a P.O.W. camp. There is evidence to suggest that Native

nations were specifically targeted on the grounds of most their political opposition to colonization, and

professor Tsianina Lomawaima, head of the American Indian Studies program at the University of

Arizona has stated that "there was a very conscious effort to recruit the children of leaders [...],

essentially to hold those children hostage”, as “it would be much easier to keep those communities

pacified with their children held in a school somewhere far away" (as reported by Bear, 2008, para. 19).

Needless to say, the quality of 'education' delivered in these residential schools was suspect at best, and

former Canadian deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs Duncan Campbell Scott

has been quoted as cautioning that residential schools must avoid producing students “made too smart

for the Indian villages” (as quoted by Hutchings, n.d., para. 23). One 1907 report conducted by the

chief medical officer of the Canadian Department of Indian Affairs, P. H. Bryce, found an average

death toll of approximately 24% among the students interned in these institutions, ranging as high as

42% when including those students who died at home after being discharged from the residential

schools, once they fell too ill to perform the forced labour which these institutions required of them on

a daily basis (as reported by Spear, 2010, para. 9). Today, any number of these children remain

unaccounted for, and more than 28 mass graves have been reported at the sites of former residential

schools, as well as evidence that some institutions (such as the Saddle Lake Blue Quills, and Hobbema

Ermineskin Catholic Schools of Alberta) simply resorted to incinerating students' remains in their

furnace (as reported by Rheault, 2011, p.4, para. 8, 9).

During the 1960s, as the blatant mass internment of indigenous children fell out of fashion with

the liberal aesthetic of this decade, residential schools (while remaining operational, albeit more

quietly) were augmented by the Canadian state with a tactic which became known as the “sixties

scoop”--a term coined by Patrick Johnston in 1983 to describe “the mass removal of Aboriginal

children from their families into the child welfare system, in most cases without the consent of their

families or bands” (as reported by the University of British Columbia, 2009, para. 2)--to which the

Métis were no more immune than had they been to smallpox or residential schools. To give some idea

of the scope to which this tactic was employed, celebrated Métis author Maria Campbell has stated

that“of the 15 families” in the settlement which she was raised, “only two had kept their children”

during this period (as reported by Orth, 2002, para. 7). For context, while precious little data has been

compiled as yet regarding the dispossession of the 20th century (to which my own family have since

fallen victim), the Métis had by this time become derogatively known as 'road allowance people',

reduced in many cases to squatting temporarily on tracts of land (or 'road allowances') reserved

by the Crown for future development, waiting to be evicted once their existence again became

inconvenient to the state. Accordingly, “because many Métis did not own property, and therefore did

not pay property taxes, they could not send their children to school”, and “as a result, three generations

of Métis were unable to receive a basic education” (as reported by the Gabriel Dumont Institute, 2005,

para. 4), illustrating the profundity of the social exclusion enacted by their colonization.

In response to the destitution, and continued pressure for redress, of the Métis, only two

ameliorative initiatives of any scope were enacted during the former half of the 20th century, both of

which were modelled after the (admittedly problematic) system of 'reservations' enforced upon other

Indigenous Peoples, but which remain instructive nonetheless in their specifics. The Ewing

Commission of 1936, which found that “80% of the half-breed children of the Province of Alberta

receive no education whatever”, confirming statements made by Malcolm Norris (a chief among the

Alberta Métis at this time) “our people have been discriminated against, and to such an extent, that

even though they may pay taxes, no steps are taken by the authorities to see that their children are sent

to school” (as reported by Chartrand, Logan & Daniels, 2006, p. 127, para.s 2, 6), provided the impetus

for the first: the 'Métis Population Betterment Act' of 1938, which ceded to the Alberta Métis (in a

historic legislative victory badly needed for their population, which had absorbed the bulk of those

Métis whose dispossession had forced their westward migration) 1.25 million acres of land--in the form

of collective title this time--to lands located at Buffalo Lake, East Prairie, Elizabeth, Fishing Lake, Gift

Lake, Kikino, Paddle Prairie, Peavine, Touchwood, Marlboro, Cold Lake, and Wolf Lake, where

settlements were then established. In the from of collective title, this cession was largely

unaccompanied by the systemic fraud which had characterized the implementation of the Manitoba

Act, and while the only settlements to fall South of Edmonton (Touchwood, Marlboro, Cold Lake, and

Wolf Lake, representing 1867.7 acres of Métis land) were “later rescinded [read: reappropriated] by

order of the Alberta government” (as reported by the Gadacz, 2014, para. 3), the Buffalo Lake, East

Prairie, Elizabeth, Fishing Lake, Gift Lake, Kikino, Paddle Prairie, and Peavine Métis settlements have

persisted to the present day, standing currently as the only land-based governance structure of the Métis

within Canada's borders.

The second of these initiatives, the “development of Métis colonies in Southern Saskatchewan”

(as Barron, 1990 has termed it) under the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF)

administration of Tommy Douglas, was designed (along the lines of the Manitoba Act) to facilitate the

assimilation of the Métis into Canadian society through agricultural serfdom, and failed spectacularly.

Beginning in 1945 with this administration's purchase of land from the Catholic Church (on which a

small community of Métis had in fact already been engaged in agricultural activity, effectively

transferring them--along with the deed to the land--to the state as furnishings), from the beginning no

accommodation was made within these institutions for the Métis culture, or for its self-determination.

As Préfontaine (2006) notes, “the Métis had no input into the farms’ governance, and officials, through

the Department of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation (or, for Green Lake, the Department of Municipal

Affairs) were often unhelpful or racist” (para. 1), one blatant example of which was “clearly illustrated

in 1952 when the Green Lake Co-operative Association was advised by the resident Director of the

Saskatchewan Marketing Services not to include the word 'Métis' in the name of their organization”

(Barron, 1990, p. 262, para. 1) on the grounds that since he was “looking forward to the day when all

citizens of Saskatchewan are of equal status, regardless of race, colour and creed”, they ought “not to

brand themselves with any name indicating special race or colour” (ibid.). Many Métis fled to the

cities, pursuing wage labour in search of an alternative to the “blatant paternalism” (as termed by

Préfontaine, 2006, para. 1) of these 'rehabilitation farms', while those who remained (including elders

and the disabled) “often subsisted on government relief” (ibid.) until the closing of these institutions,

and the sale of the lands on which they had been located.

This was to mark the last appreciable initiative of redress for nearly half a century, and the

lesson to be gleaned from contrast of these examples is clear: without accommodation for meaningful

collective self-governance, Indigenous Peoples become stripped of their right to collective bargaining

through individuation; stripped of the right to collective bargaining, individuated peoples become

deprived of the defence against assimilation inherent in community, and are easily scattered before the

wind (as would be seeds unable to take root in any alien climate). This is the core of cultural genocide,

and it is precisely the methodology enacted against the Métis historically by the Canadian state.

Furthermore, this is precisely the methodology by which many of our indigenous relations find

themselves faced today, in the form of “models of autonomy [...] crafted by the state” (as MacDonald,

2009, characterizes the paradigm of the current neoliberal Indigenous-state dynamic, p. 1, para. 1, and

as this researcher would in turn characterize the scrip system forced upon the Métis in 1870).

Today, the Métis of Canada remain dispersed throughout the continent. My own family,

dispossessed in the early 20th century, relocated to the interior of British Columbia seeking employment

in the logging camps, and I now stand before you the second generation to have issued from the sod

shack which my grandfather first constructed there after the manner of les hivernants. Despite having

now likely indebted myself for the remainder of my life so as to have attained the privilege of an

education in the ways of the colony, I still cannot speak the tongue of my people with any fluency, nor

have I ever been afforded the chance to learn this skill. Our family are spread across the whole of the

province, seeking wage labour where it presents itself, and many (despite meeting the strictest legal

requirements of Métis identity) no longer retain status of any kind, not having kept up with the

ever-changing terrain of the legal obstacle course to its attainment. In sum, for lack of alternatives we

have joined the ranks of Canada's exploding 'urban Aboriginal' population, and now live separated from

one another--as well as from the land around which our culture revolves--along with more than 50%

of the Indigenous Peoples surveyed by the Canadian Census in 2006, who earned on average 10-23%

less than their “Non-Aboriginal” counterparts, and suffered on average 56-64% more instances of low

income among families (as reported by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, 2010,

para. 2, and calculated using the data reported by this source in table 1). This is the endgame of

colonization, and the “final solution” of the colonial state (to borrow a turn of phrase first coined by

British Columbian Indian Agent General-Major D. MacKay, and quoted by Spear, 2010, para. 11).

Everything old is new again, and the models of conditional, individuated title crafted by the neoliberal

state are nothing more than the new trading beads. Only now have the Métis begun to find their way

home, accorded for the first time constitutional rights in 2013 following 143 years of struggle, and 13

of legal battles (as reported by the Canadian Press, 2013, para. 1).

To my indigenous relations, I can only offer the history of my people as a cautionary example to

your own: self-determination is an absolute concept, and autonomy cannot be negotiated. Freedom

conditional to the terms of the state is no longer in fact freedom; it is the negotiation of ones' terms of

servitude. As we find our way home, let us not stray from this truth, and may the trail upon which we

meet be beaten circular by the steps which we take today.

Works Cited:

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. (2010). Fact sheet: Urban Aboriginal population in Canada. Retrieved from www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100014298/1100100014302

Amos, A. (1820). Report of trials in the courts of Canada, relative to the destruction of the Earl of Selkirk's settlement on the Red River: With observations. Retrieved from peel.library.ualberta.ca/bibliography/113/93.html

Anderson, A. (2006). French and Métis settlements. In University of Regina (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Retrieved from esask.uregina.ca/entry/french_and_metis_settlements.html

Augustus, C. (2008). Métis scrip. In Saskatchewan Council for Archives & Archivists (Ed.), Our Legacy. Retrieved from scaa.sk.ca/ourlegacy/exhibit_scrip

Barkwell, L. (2014). Métis firsts in North America. Retrieved from www.mmf.mb.ca/metis_firsts_in_north_america.php

Barron, F. L. (1990). The CCF and the development of Métis colonies in Southern Saskatchewan during the premiership of T. C. Douglas, 1944-1961. Canadian Journal of Native Studies 10(2), 243-270. Retrieved from www3.brandonu.ca/library/cjns/10.2/barron.pdf

Beal, B. (2013). Red River Expedition. In Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/red-river-expedition/

Bear, C. (2008, May 12). American Indian boarding schools haunt many. NPR. Retrieved from www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=16516865

Bowsfield, H. (1976). PARISIEN, NORBERT (Vol. 9). In University of Toronto/Université Laval (Eds.), Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved from www.biographi.ca/en/bio.php? id_nbr=4641

Binnema, T. (2006). “With tears, shrieks, and howlings of despair”: The smallpox epidemic of 1781-1782. In Cavanagh, C. A., Payne, M., & Wetherell, D.G. (Eds.), Alberta formed, Alberta transformed: Vol. 1 (pp. 111-132). Edmonton, Calgary AB: Universities of Edmonton, Calgary.

Canadian Press. (2013, Jan. 9). Federal Court grants rights to Métis, non-status Indians. CBC News. Retrieved from www.cbc.ca/news/politics/federal-court-grants-rights-to-m %C3%A9tis-non-status-indians-1.1319951

CBC. (2001). A people's history: Battle at Seven Oaks. Retrieved from www.cbc.ca/history/EPCONTENTSE1EP6CH5PA3LE.html

CBC. 2001. A people's history: The capture of Fort Garry. Retrieved from www.cbc.ca/history/EPCONTENTSE1EP9CH2PA2LE.html

Charland, M. (2007). Newsworld, Riel, and the Métis: Recognition and the limits to reconciliation. Canadian Journal of Communication 32(1), 9-28. Retrieved from www.cjc-online.ca/index.php/journal/article/download/1779/1904

Chartrand, L. N., Logan, T. E. & Daniels, J. D. (2006). Métis History and Experience and Residential Schools in Canada. Retrieved from www.ahf.ca/downloads/metiseweb.pdf

Dorion, L. & Préfontaine, D. R. (2003). Métis land rights and self-government. Retrieved from www.metismuseum.ca/media/db/00725

Duval, J. (2001). The Catholic church and the formation of Métis identity. Past Imperfect 9(1), 65-87. Retrieved from https://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/pi/article/viewFile/1432/972

Gabriel Dumont Institute. (2005). Life after 1885. In Back to Batoche. Retrieved from www.virtualmuseum.ca/sgc-cms/expositions-exhibitions/batoche/html/resources/proof_life_after_1885.php

Gadacz, R. R. (2014). Métis Settlements. In Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/metis-settlements/

Galabuzzi, G-E. (2007). Social exclusion, race and immigration as social determinants of health. Retrieved from McGill University, Institute of Social and Health Policy website: www.mcgill.ca/files/ihsp/%E2%80%8BGalabuzziPresentation.pdf

Glenbow Museum. (2014). Riel Rebellion Telegrams fonds (1-49). In Collections and Research. Retrieved from www.glenbow.org/collections/search/findingAids/archhtm/extras/ telegrams/telegrams1-49.pdf

Herbermann, C. G., Pace, E. A., Pallen, C. B., Shahan, T. J. & Wynne, J. J. (1911). Catholic Encyclopedia (Vol. 11). Retrieved from ia801707.us.archive.org/16/items/07470918.11.emory.edu/07470918_11.pdf

Hutchings, C. (n.d.). Canada’s First Nations: A legacy of institutional racism. Retrieved from www.tolerance.cz/courses/papers/hutchin.htm

Jung, P. J. (1997). French-Indian intermarriage and the creation of Métis society. Retrieved from University of Wisconsin Green Bay website: www.uwgb.edu/wisfrench/library/articles/metis.htm

King, T. (2012). The inconvenient Indian. Toronto, ON: Anchor Canada.

Kinsey Howard, J. (1952). Strange empire: A narrative of the northwest. New York, NY: William Morrow and company.

Lemieux, L. (2003) “PROVENCHER, JOSEPH-NORBERT (Vol. 8). In University of Toronto/Université Laval (Eds.), Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved from www.biographi.ca/en/bio/provencher_joseph_norbert_8E.html

Library and Archives Canada. (2012). Métis scrip: The foundation for a new beginning. Retrieved fromwww.collectionscanada.gc.ca/metis-scrip/005005-2000-e.html

Macleod, R. C. (1994). DUMONT, GABRIEL (Vol. 13). In University of Toronto/Université Laval (Eds.), Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved from www.biographi.ca/en/bio.php?BioId=40814

MacDonald, F. (2009). Indigenous Peoples and neoliberal ‘privatization’ in Canada: Opportunities, cautions and constraints. Retrieved from www.cpsa-acsp.ca/papers-2009/macdonald.pdf

Mailhot, P. R. (1994). RITCHOT, NOËL-JOSEPH (Vol. 13). In University of Toronto/Université Laval (Eds.), Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved from www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ritchot_noel_joseph_13E.html

Manitoba Historical Society. (2014). Norbert Parisien. In Memorable Manitobans. Retrieved from www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/people/parisien_n.shtml

Manitoba Métis Federation. (2003). Riel, Louis, and Clarke, Lawrence. In Illustrations From "Gabriel Dumont: Métis Legend". Retrieved from www.metismuseum.ca/resource.php/00107

Matheson Henderson, A. (1967). The Lord Selkirk Settlement at Red River, part 1. Manitoba Pageant 13(1). Retrieved from www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/pageant/13/selkirksettlement1.shtml

Mays, H. J. (2003). MACDONELL, MILES (Vol. 8). In University of Toronto/Université Laval (Eds.), Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved from www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonell_miles_6E.html

Métis Nation of Ontario. (2014). The Métis & the War of 1812. Retrieved from www.metisnation.org /culture--heritage/the-metis-and-the-war-of-1812/the-metis--the-war-of-18 12-

Milne, B. (1995). The Historiography of Métis Land Dispersal, 1870-1890. Manitoba History 30(1). Retrieved from www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/mb_history/30/metislanddispersal.shtml

Orth, K. (2002). Road Allowance People's history shared in Toronto. Birchbark Writer 12(1). Retrievedfrom www.ammsa.com/publications/ontario-birchbark/road-allowance- peoples-history-shared-toronto

Préfontaine, D. (2006). Métis farms. In Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Retrieved from esask.uregina.ca/entry/metis_farms.html

Rauch, S. J. (2012). A Stain upon the nation? A review of the Detroit Campaign of 1812 in United States military history. Michigan Historical Review, 38(1), 129–153. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/discover/10.5342/michhistrevi.38.1.0129?uid=3739400&uid=2129&ui d=2&uid=70&uid=3737720&uid=4&sid=21104944896757

Rheault, D. (2011). Solving the “Indian problem”: Assimilation laws, practices & Indian residential schools. Omfrc.org. Retrieved from www.omfrc.org/newsletter/specialedition8.pdf

Solon Law Archive. (1995). Constitution Act 1871 (the British North America Act 1871). Retrieved from www.solon.org/Constitutions/Canada/English/ca_1871.html

Solon Law Archive. (2000). Manitoba Act, 1870. Retrieved from www.solon.org/Constitutions/Canada/English/ma_1870.html

Spear, W. K. (2010, Mar. 10). Canada's Indian residential school system. A Life Sentence. Retrieved from waynekspear.com/2010/03/10/canada%E2%80%99s-indian-residential-school-system/

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (n.d.). Residential schools. Retrieved from www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/index.php?p=4

University of Alberta. (2009). Hospitals, healthcare & social welfare. Retrieved from Library of the University of Alberta, Oblates in the West Project website: oblatesinthewest.library.ualberta.ca/eng/impact/healthcare.html

University of British Columbia. (2009). Sixties scoop. Retrieved from University of British Columbia, First Nations Studies Program website: indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/ home/government-policy/sixties-scoop.html

University of Manitoba. (1998). Deaths of Sutherland and Parisien. Retrieved from University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections website: www.umanitoba.ca/canadian_wartime/ grade6/teachers/module5/deaths_sutherland_parisien.shtml

University of Saskatchewan. (n.d.). The Northwest Resistance: Chronology of events. Retrieved from University of Saskatchewan, Library website: library.usask.ca/northwest/background/chronol.htm

U.S. Department of State. (2007). Section 1: Bilateral treaties. In Treaties in force: A list of treaties andother international agreements of the United States in force on November 1, 2007. Retrieved from www.state.gov/documents/organization/83046.pdf

Van Kirk, S. M. (1982). ISBISTER, ALEXANDER KENNEDY (Vol. 11). In University of Toronto/Université Laval (Eds.), Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved from www.biographi.ca/en/bio/isbister_alexander_kennedy_11E.html

Voisine, N. (1985). DUMOULIN, SÉVÈRE (1793-1853) (Vol. 8). In University of Toronto/Université Laval (Eds.), Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved from www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dumoulin_severe_1793_1853_8E.html