Kumar Hamer Attitudes and beliefs toward student diversity

-

Upload

michiganstate -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Kumar Hamer Attitudes and beliefs toward student diversity

Journal of Teacher Education64(2) 162 –177© 2012 American Association of Colleges for Teacher EducationReprints and permission: http://www. sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navDOI: 10.1177/0022487112466899http://jte.sagepub.com

The cultural landscape of United States is fast changing. Throughout the United States, culturally pluralistic schools and classrooms are replacing monocultural schools and classrooms. Demographers predict that by 2035, half the school-age population will be students of color (Villegas & Lucas, 2002). In contrast, the majority of the teachers will still be White, monolingual, middle-class women (National Center for Education Statistics, 2012; U.S. Department of Education). Many White teachers experience some ambiva-lence toward minority and immigrant students (Hollins & Torres-Guzman, 2005; Sleeter, 2001) and doubt their effi-cacy in teaching students whose cultural backgrounds differ from their own (Helfrich & Bean, 2011). Cho and DeCastro-Ambrosetti (2005), as well as Ladson-Billings (2000), argue that preservice teachers’ ill-preparedness to meet academic and psychosocial needs of minority and immigrant students and sometimes their lack of understanding of how cultural identities play out within the classroom context may be partly attributed to poor preparation by teacher preparation programs. One question that needs to be addressed in teacher education research and practice is the connection between teachers’ beliefs and attitudes about their students and their own efficacy, and the kinds of practices they use to meet students’ needs in the classroom.

Despite attempts to regulate teacher education programs to prepare preservice teachers to serve in culturally pluralis-tic classrooms, it is unclear how successful these programs

are (Sleeter, 2001), or how many substantively address the need (Zeichner, 2003). However, research does suggest that more multicultural education in preservice teacher education positively affects teachers’ attitudes and sense of efficacy toward helping culturally and linguistically diverse students (Bodur, 2012). The primary purpose of this study is to exam-ine the relationship between White preservice teachers’ beliefs and attitudes toward minority and less affluent stu-dents in relation to actual classroom practices they are likely to endorse. A second purpose is to examine whether increased exposure to preservice curricula intended to predispose them toward culturally pluralistic beliefs and practices shapes pre-service teachers’ beliefs, helping them become less cultur-ally encapsulated—particularly with regard to ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and “otherness.” In other words, do experiences in teacher-licensure programs help preservice teachers overcome, at least to some degree, prejudicial beliefs and expectations they may have of poor and minority students; decrease their degree of discomfort in interacting with students they perceive as different from them; and encourage them to adopt instructional strategies and classroom

466899 JTEXXX10.1177/0022487112466899Journal of Teacher EducationKumar and Hamer

1University of Toledo, OH, USA

Corresponding Author:Revathy Kumar, University of Toledo, Mail Stop # 921, 2801 West Bancroft St., Toledo, OH 43606-3390, USA Email: [email protected]

Preservice Teachers’ Attitudes and Beliefs Toward Student Diversity and Proposed Instructional Practices: A Sequential Design Study

Revathy Kumar1 and Lynne Hamer1

Abstract

This study draws on insights from achievement goal theory and multicultural education to examine the interrelated nature of preservice teachers’ biases and beliefs regarding culturally diverse students and the kind of instructional practices they are likely to pursue. Cluster analysis of cross-sectional data (n = 784) suggests that approximately 25% of preservice teachers explicitly endorsed some stereotypic beliefs about poor and minority students and expressed some discomfort with student diversity. Analyses of variance results provide evidence that preservice teachers were significantly less biased and prejudiced and more likely to endorse adaptive instructional practices by the time they were ready to graduate from the teacher education program than they were during their 1st year in the program. Paired t-test results based on longitudinal data (n = 79) suggest that some gains preservice teachers accrued midway through the program were lost when they were close to graduation. Implications of these findings are discussed.

Keywords

preservice teachers, student diversity, achievement goals, multicultural education

Kumar and Hamer 163

practices that are likely to promote learning and emotional well-being among all students?

Preservice Teachers’ Attitudes Toward Cultural DiversityPreservice teachers are members—either ascribed or by choice—to several cultural communities as well as affinity communities. While affinity communities, based on per-sonal or professional interests, influence individuals’ beliefs, values, and behaviors, membership in ascribed cultural com-munities defined, for example, by nationality, race, ethnic-ity, class, religion, and language is often taken for granted because of long years of socialization and thus have deep, often unrecognized effects. Membership within these ascribed communities defines to a large extent preservice teachers’ cultural identity and informs their values, behav-iors, and attitudes. Thus, choices they make, actions they take, and experiences they value as teachers, whether inside or outside the classroom, are likely to be informed by past experiences, knowledge base, and learned value beliefs—their socialized cultural identities. Preservice teachers who are White are much less likely to consciously reflect on their cultural identity as a majority privileged group. In a detailed review of 80 studies about the education of preservice teach-ers, Sleeter (2001) concludes that

It is difficult to say how much impact multicultural education courses have on White students. . . . Almost none of the studies . . . examined the impact of multi-cultural education coursework on how pre-service stu-dents actually teach children in the classroom. (p. 99)

Research demonstrates that preservice teachers have historically brought very little cross-cultural background, knowledge, or experience to their training (Hollins & Torres-Guzman, 2005; Ibarra, 1999). In fact, many researchers have shown that they tend to retain stereotypic beliefs about chil-dren from cultural, ethnic, or socioeconomic minority group (Barry & Lechner, 1995; Bell, Horn, & Roxas, 2007; Darling-Hammond, 2006; Gilbert, 1995; Hollins & Torres-Guzman, 2005; King, Hollins, & Hayman, 1997; Sleeter, 1985, 2001; Valli, 1995). Notwithstanding professional training, many preservice teachers continue into the profes-sion with a somewhat limited view of multicultural educa-tion and a lack of preparedness for teaching diverse classroom populations (Goodwin, 1994). Valli (1994) asserts that their negative attitudes toward cultural groups other than their own persist as they view student diversity as a problem to be dealt with, or a condition to be fixed, rather than as a resource. Furthermore, an array of evidence indicates that such student characteristics as socioeconomic status and ethnicity influ-enced teachers’ susceptibility to biased achievement and motivation expectations (DeCastro-Ambrosetti & Cho, 2011; Eccles & Wigfield, 1985; Jussim & Harber, 2005;

Magos, 2006; Rubie-Davis, Hattie, & Hamilton, 2006; Tennenbaum & Ruck, 2007; Weinstein, 2002). A recent examination of middle school White teachers’ (n = 241) implicit attitudes toward culturally diverse students (Kumar, Karabenick, & Burgoon, 2012) indicated that White teachers demonstrated a slight implicit preference for White over Arab/Arab American students and moderate implicit prefer-ence for White over African American students. Findings from this study reveal that teachers’ implicit preference for White over Arab/Arab American students and their implicit preference for White over African American students were significantly correlated suggesting an overall preference for White students relative to non-White students among White teachers. This study also demonstrated that teachers’ implicit evaluations of different groups affected their classroom behaviors. These findings highlight the need to examine how effectively teacher preparation programs empower preser-vice teachers to recognize their biases, overcome stereotype beliefs about less affluent and minority students, develop a sense of comfort in interacting with different others, and engage in classroom practices that reflect an openness to cul-turally diverse beliefs, values, and practices.

Theoretical PerspectivesFaced with the challenge of meeting the academic and psy-chosocial needs of students from multiple cultures, scholars and researchers from different disciplines—and sometimes disparate perspectives—have proposed reforms to the exist-ing educational system, including changes to teacher educa-tion programs. Among these scholars are multicultural educationists and achievement goal theorists.

Multicultural PerspectiveGrounded in sociological theory, multicultural education focuses on understanding how social and historical factors have influenced students’ academic success and their per-ceptions of the purposes of schooling. As Dewey argued, schools’ main institutional purpose is preparing students to participate in society. In line with this argument, multicul-tural education promotes the development of such demo-cratic and social justice values as equity, justice, respect, and equality (Nieto, 2000).

Several multicultural educationists (e.g., Fordham, 1996; Grant & Sleeter, 1996; Hollins, 1990) direct our attention to status quo school culture as both reflecting and teaching White, middle-class culture, which reinforces White, middle-class students—their knowledge, behaviors, and ways of interacting with teachers and peers—as the norm, valued, and “right.” This is also likely to contribute to the perception held by mainstream students and teachers that other students are culturally inferior in knowledge and behavior (Banks, 2008; Grant & Sleeter, 1996). Consequently, minority-group students often feel stigmatized, devalued, and excluded

164 Journal of Teacher Education 64(2)

when some mainstream teachers treat them as victims and/or as incapable academically and socially (Ladson-Billings, 1993, 2000; Steele, 1997; Steele & Aronson, 1995). In an effort to address this issue, scholars have identified many approaches to multicultural education and constructed numerous typologies (e.g., teaching exceptionally and cul-turally different students, human relations, single-group studies, multicultural, and multicultural and social justice; Sleeter & Grant, 2008). Overall, multicultural educationists call for changes and reforms in school policies and practices that would promote equity among students (Banks, 2004). Thus, policies or practices promoting inequality, among them tracking and ability grouping, must be replaced by pol-icies and practices such as equity pedagogy and culturally responsive teaching that empower students to acquire the requisite knowledge and skills to function effectively and thoughtfully in a democratic society (Banks, 2008; Campbell, 2010). Furthermore, they assert that features of the current education system—scheduling class time, physical environ-ment in the classroom, assessment techniques and test scores, and factors allowing teachers to maintain control of the classroom—should be restructured (Banks, 2004) and that pedagogy should be recast in a social-reconstructionist framework. Specifically, pedagogy should aim to solve social problems and promote equality; teachers should raise students’ consciousness about social problems and provide tools for critiquing and acting on them; and students’ should actively engage in understanding and tackling social prob-lems (Oakes & Lipton, 2006). Democratic, multicultural education fundamentally requires that teachers be disposed toward understanding and valuing cultural pluralism, genu-ine respect for how cultural diversity is expressed visibly and behaviorally, and rejection of prejudice and enactment of discrimination. It further requires that they hold equally high expectations for all students, while acknowledging and accepting that poverty and bureaucracy within diverse urban settings will make teaching and learning more difficult (Larkin, 1995). To realize the vision of multicultural educa-tion through equity pedagogy and culturally responsive teaching, it is essential, according to multiculturalists, to redefine school culture as one that students find empower-ing, validating, and inclusive (King et al., 1997).

Achievement Goal TheoryAchievement goal theory is a social cognitive theory of motivation. Achievement goal theorists, a group of research-ers with a less explicitly political agenda than that of multi-culturalists, have also proposed school reforms designed to make the culture and climate of schools more conducive to student learning and motivation (e.g., C. Ames, 1992; Maehr & Midgley, 1991, 1996; Midgley, 1993; Pintrich, 2000). Achievement goal theory emerged as an important theory in the 1980s and 1990s when several researchers (C. Ames, 1984; R. Ames & Ames, 1993; Dweck & Leggett, 1988;

Maehr & Midgley, 1991; Midgley, 1993; Nicholls, 1984; Pintrich & Garcia, 1991) attempted to understand students’ reasons for engaging in academic behavior and their percep-tions of what purposes for schooling were emphasized in schools and classrooms. Based on their research, achieve-ment goal theorists identified two distinct purposes or achievement goals: mastery goals and performance goals. These two approaches represent different conceptions of school success and very different reasons for engaging in academic activity. When students believe that the primary reason for schoolwork is to learn, improve, and be chal-lenged, they are mastery-focused. However, when students perceive that the primary purpose of schoolwork is to look smarter than their classmates, demonstrate their ability, and compare favorably with others in their class, they are perfor-mance-focused (Anderman & Maehr, 1994; Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Pintrich, 2000).

Goals stressed in the learning environment influence how students define their personal achievement goals, and many schools differ in the extent to which they emphasize mastery and performance goals (Anderman & Maehr, 1994; Kumar, 2006; Maehr & Midgley, 1991). For example, school poli-cies and practices can communicate to students that the pur-pose of being in school and doing schoolwork is learning, mastering knowledge and skills, and improving; alternately, they can communicate that the purpose is demonstrating ability and comparing performance with others in the class. Achievement goal theorists Maehr and Midgley (1991, 1996) specifically examine the nature of tasks in which stu-dents engage, how classroom time is conceptualized, how teachers and students interact, and how salient normative standards of grading and social comparisons are in the class-room. They observed that teachers create a mastery-focused environment when they engage students in tasks that are meaningful and challenging, require students to share responsibility for decisions made, adopt instructional strate-gies that embrace a range of needs and interests, recognize effort and avoid social comparison among students, promote heterogeneous ability grouping, and use criterion-referenced norms for evaluation. In contrast, they observed that teachers who focus on social comparison among students, endorse ability grouping, and use norm-referenced criteria for evalu-ation create a more performance-focused learning environment (C. Ames, 1992; Meece, Anderman, & Anderman, 2006).

Therefore, how teachers—and schools as a whole—define and perceive different aspects of the learning environment and what they practice in this context determines whether the school is predominantly mastery- or performance-focused. We argue that the attitude and mind-set associated with mastery-focused orientation is one of openness to differ-ences among students and of acceptance of diversity in stu-dents’ thoughts and actions. Such a mind-set, we believe, is aligned with the vision of multicultural education. To date, no research within the achievement goal theory perspective has examined the relationship among the extent of preservice

Kumar and Hamer 165

teachers’ exposure to teacher education curricula, their beliefs about diversity, and their proposed mastery- and performance-focused practices.

Attitudes Toward Diversity and Classroom Instructional Practices: Proposed Complementarity of Multicultural Perspective and Achievement Goal Theory

A central goal of this study, identified as critical for 21st-century education by Darling-Hammond (2006), is to determine coherence and integration in preservice teachers’ educational experiences as they progress through teacher education programs. The multicultural, social justice vision of creating a school culture necessary in a culturally pluralis-tic society emphasized in the required sociological-foundations course parallels the vision of schooling informed by achieve-ment goal theory and research. It also coheres with the trans-lation of achievement goal theory into school policies and practices emphasized in the required psychological-founda-tions course. It is unclear, however, to what extent faculty and students involved in teacher education programs recog-nize these parallels let alone capitalize on potential gains if the two are brought into coherence.

We draw on multiculturalist and achievement goal theory perspectives, the former within the sociological-foundations discipline and the latter in the realm of educational psychol-ogy, to investigate the relationship between these two usually-not-associated areas of study. We propose that mul-ticultural education and achievement goal theory are two sides of a coin. Multicultural educationists base school reforms on an understanding of education as antiracist, com-prehensive, pervasive, and rooted in social justice (Nieto, 2002). Goal theorists base school reforms on an understand-ing of education as a process of progressing, growing in understanding, and equipping children to become lifelong learners (Maehr & Midgley, 1996). Though the stated pur-poses differ, we propose that they are complementary and that they should be taught as such. If we want children to become “reflective and active citizens who contribute to and participate in making our nation more democratic” (Banks, 1997, p. 31), we need children to become lifelong learners. As Midgley (1993), a prominent achievement goal theorist, points out, we cannot do this if students are reminded every day that there are winners and losers and that getting good grades and doing well on standardized tests is the goal of education.

We posit that preservice teachers who wish to create a mastery-focused environment and develop a learning com-munity in which every student feels empowered and vali-dated are likely to reflect positive intercultural attitudes and be capable of critically examining personal prejudices and stereotypic beliefs. They need to possess a sense of comfort

in interacting with others whom they perceive as different in values, beliefs, or physical appearance. Belief in mastery-focused goals and the importance of mastery-focused learn-ing environments requires openness to different ways of thinking and being—an appreciation of diverse worldviews. Preservice teachers who do not question students’ capabili-ties and who endorse mastery-focused instructional practices are less likely to resort to normative social comparisons; rather, they are more likely to emphasize collaboration and mutual respect among students and to create a learning envi-ronment that does not perpetuate inequality in practice and pedagogy. In contrast, preservice teachers’ endorsement of performance-focused instructional practices incorporates a strong element of social comparison in the classroom. For example, performance-focused teachers and preservice teachers are more likely to define learning in terms of high and low grades and to distinguish “smart students” from “not-so-smart students.” As the onus of school success is placed squarely on students’ shoulders, performance-focused teachers are less likely to feel the need to adapt their instruc-tional strategies to meet the needs of culturally diverse stu-dents. These evaluative practices, we believe, are particularly detrimental for minority and less affluent students as they encourage labeling and categorizing students based on char-acteristics such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic, and immi-grant status. Consequently, preservice teachers who hold stereotypes about the ability of poor and minority students to succeed in school, and who value students depending on their social and cultural backgrounds are more likely to endorse performance-focused practices.

To summarize, the fourfold purposes of this study are to examine

1. the nature and strength of the relationship between White preservice teachers’ beliefs and attitudes (e.g., stereotypic beliefs toward minority and less affluent students, unwillingness to adapt instruction for culturally diverse students, beliefs related to students’ assimilation into mainstream culture, and feelings of psychological discomfort in interacting with students who are different from them) in rela-tion to actual classroom practices (e.g., mastery- vs. performance-focused) they are likely to endorse.

2. whether level in the licensure is related to preser-vice teachers’ attitudes and beliefs regarding stu-dent diversity, proposed classroom practices, and feelings of efficacy as prospective teachers.

3. whether the level in the licensure program moder-ates the relationship between preservice teachers’ attitudes and beliefs regarding student diversity, proposed classroom practices, and feelings of effi-cacy as prospective teachers.

4. whether the time spent in terms of moving from a lower to a higher level in a teacher-licensure pro-gram helps preservice teachers overcome, at least

166 Journal of Teacher Education 64(2)

to some degree, prejudicial beliefs and expecta-tions they may have of poor and minority students, encourages them to engage in more mastery- and less performance-focused instructional practices, and to promote respect and collaboration in the classroom, and enhances their feelings of efficacy as prospective teachers.

MethodSample and Data-Collection Procedures

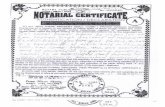

The sample of this study includes preservice teachers enrolled in coursework toward licensure in a Midwestern university of approximately 20,000 students in a northern, midsized city. The data collection was based on a sequential design, including both cross-sectional and longitudinal data (see Figure 1). Across the four data-collection waves in the fall and spring of two consecutive years, 83.1% of the par-ticipating preservice teachers were White, 5.2% were African American, and 4.4% belong to other ethnic groups. Across the four waves, 7.3% of the preservice teachers pres-ent on the day the surveys were administered in the class-room withdrew their participation. Despite assurances that the information they provided would remain confidential, they were unwilling to reveal the last six digits of their social security number that was requested for purposes of longitu-dinal data collection. The final sample for this study includes

only White preservice teachers (N = 868) as the number of African American and other ethnic group preservice teach-ers were too few to conduct meaningful comparative analyses.

Course Selections for Survey AdministrationThe surveys were administered by trained research assistants to preservice teachers enrolled in the Orientation Seminar (OS) in the 1st year of the licensure program (freshmen or sophomores); the Social Foundations course, “Schooling and Democratic Society” (SDS), approximately midway through the licensure program (juniors and sometimes seniors); and the Student Teaching Seminar (STS), in the final year of the licensure program (seniors or later). All the courses targeted for survey administration were core courses that students enrolled in the teacher-licensure program were required to take.

At the time of the study, at Level 1, the very first course that all preservice teachers entering the licensure program enrolled into was the OS. At the second level, the SDS course and the applied educational psychology course were core requirements for all prospective teachers. SDS was deemed more appropriate than educational psychology for survey administration because a major emphasis of SDS curriculum was a critical examination of disciplinary approaches to issues of cultural diversity (Tozer & Miretzky, 2000) grounded in multicultural social-reconstructionist praxis and the primary focus of the survey is preservice teachers’ attitude toward

OS

STS

SDS

OS

STS

SDS

OS

STS

SDS

OS

STS

SDS

Wave 1

(Year 1, fall)

Level in College

OS - Freshman & sophomore years

SDS - Junior & senior years

STS - Senior and fifth year

Cross-sectional data

Longitudinal data

Wave 2

(Year 1, spring)

Wave 4

(Year 2, spring)Wave 3

(Year 2, fall)

Figure 1. Sequential data-collection design

Kumar and Hamer 167

student diversity. The philosophical underpinning of the course, the coursework, and basic assignments required of preservice teachers was consistent across all sections of the SDS course. Furthermore, although the educational psychol-ogy curriculum incorporated educational implications and applications of several psychological theories, including motivational theories such as achievement goal theory, fac-ulty teaching the various sections of this course did not engage in a coordinated and consistent effort to link these theories to the education of culturally diverse students, including poor and minority students. The STS courses, which were the final subject-specific methods courses that preservice teachers were required to take, were selected for the survey administration at the third level as these courses coincided with their field experiences teaching in schools.

The survey administration timing was determined by the nature and purpose of the three courses. OS participants completed the surveys during the first 2 weeks of the semes-ter, before any substantial exposure to the licensure program. In the SDS courses, surveys were administered during the last 3 weeks of the semester. This timing ensured that, prior to completing the survey, preservice teachers received sub-stantial exposure to concepts and constructs in multicultural education, giving them the knowledge and tools to under-stand their biases and prejudices, as well as the implications these could have for their practices as teachers. Preservice teachers in the STS course also completed the survey in the latter half of the semester after they began to apply the theo-retical and practical knowledge accrued in the licensure program.

Sample Selection for Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Data AnalysisThe OS course was offered only in the fall semesters, whereas SDS and STS were offered in both fall and spring semesters. Therefore, the study includes two waves of data from the OS course and four waves from SDS and STS courses. Of the total sample, most preservice teachers (n

cross-sectional = 784, n

OS = 192, n

SDS = 341, and n

STS = 251)

participated only once during the four data-collection waves. In an effort to have two distinct samples, one for cross-sectional analysis and the other for longitudinal analysis, data from preservice teachers who participated at only one time point were included for cross-sectional data analysis. The reason for not including participants who had taken the survey more than once for cross-sectional data analysis was to control for any learning or item response change that may have occurred due to practice.

Eighty-four White preservice teachers participated in the study on at least two occasions. No preservice teachers within the 2-year, four-wave survey period contributed data at all three time points, probably because a 2- to 3-year gap exists between OS and SDS. Five preservice teachers com-pleted the survey in the OS during the fall of the 1st year and

in SDS the following year. As this was a very small sample, these participants were not included in the longitudinal data analyses. The remaining students (n

longitudinal = 79) completed

the same survey at two time points, first in SDS and subse-quently in STS. Data from these participants were utilized for longitudinal data analysis.

MeasuresItems measuring preservice teachers’ beliefs regarding minority, low-socioeconomic-status (LSES) students; their comfort in interacting with culturally diverse students; and their belief that cultural minority students should assimilate to mainstream culture were developed based on an extensive literature review (Byrnes & Kiger, 1994; Gibson & Dembo, 1984; Grady, 1971; Pohan & Aguilar, 2001) and piloted on a sample of preservice teachers. All measures of diversity were created using exploratory factor analysis, with the first wave of data followed by confirmatory factor analysis of the constructs with the second wave of data. Scales measuring the likelihood of adopting mastery- versus performance-focused learning environment, promoting respect and col-laboration in the classroom, and efficacy beliefs as a teacher were adapted from the teacher measures in Patterns of Adaptive Learning Survey (PALS; Midgley et al., 2000). All the measures are on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all true), to 3 (somewhat true), to 5 (very true). The reliability reported for each measure is the average Cronbach’s alpha across the four waves.

Preservice Teachers’ Beliefs and Attitudes Regarding Diversity

Beliefs about ethnic minority students. This five-item scale consists of statements indicative of commonly held stereo-typical beliefs about devalued minorities such as “In general, White/European American students place a higher value on education than do people of color.” The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale is .78.

Beliefs about LSES students. The four-item scale measuring preservice teachers’ beliefs about students from less affluent backgrounds is also based on some commonly held stereo-types and includes items such as “Generally, students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are not interested in school and schoolwork as students from middle and higher socioeconomic backgrounds.” The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale is .70.

Beliefs about minority assimilation into mainstream culture. Three items in this four-item scale are drawn from earlier research examining teachers’ and preservice teachers’ beliefs regarding the importance of assimilating into a school’s main-stream culture. They include (a) “The rapid learning of Eng-lish should be a priority for non-English-proficient or

168 Journal of Teacher Education 64(2)

limited-English-proficient students even if it means they lose the ability to speak their native language” (Byrnes & Kiger, 1994, p. 230); (b) “Minority groups wishing to be truly inte-grated into American society should subordinate their cultural origins and work more in adapting to the American way of life” (Grady, 1971, p. 150); and (c) “People of color are ade-quately represented in most textbooks today” (Pohan & Agui-lar, 2001, p. 179). The fourth item, “Students should not be allowed to speak a language other than English while in school” was developed for this study. The reliability of this scale is .65.

Discomfort in interacting with diverse students and faculty. Because no scale existed for use in empirical studies, we constructed a scale assessing preservice teachers’ discomfort in interacting with diverse students and faculty. This mea-sure examines preservice teachers’ overall feelings of psy-chological discomfort in interacting closely with students and instructors whom they perceive to be culturally differ-ent. This scale differs from existing measures of preservice teachers’ attitudes and beliefs; it does not focus on any spe-cific cultural group (e.g., specific ethnic minority groups, special education students, or language minority students). Rather, it measures preservice teachers’ discomfort in instructing and interacting with others whom they perceive as different from themselves. Such a measure is important because in their professional lives, teachers will encounter a broad spectrum of diversity in their classrooms and schools. This scale consists of five items. Some examples of items on this scale are “I prefer to work with students who share my culture” and “I feel uncomfortable interacting with students whose backgrounds are different from mine.” The Cron-bach’s alpha for this scale is .83.

Preservice Teachers’ Projected Instructional Strategies, Promoting Respect and Collaboration in the Classroom, and Efficacy Beliefs as Prospective Teachers

The scale measuring unwillingness to adapt instruction to the needs of diverse students was developed for this study. The scales assessing preservice teachers’ mastery- and performance-focused approaches to teaching, promoting respect and collaboration in the classroom, and feelings of efficacy as prospective teachers are adapted from the teacher measures in PALS developed by Midgley and colleagues (2000). The wording of the items in the present survey is directed toward preservice teachers’ projected approaches and strategies as opposed to wordings in the original items directed to approaches and strategies adopted by inservice teachers. These measures have well-established psychomet-ric properties (Anderman & Midgley, 2002).

Unwillingness to adapt instruction to meet the needs of diverse students. The six items on this scale tap into

preservice teachers’ willingness or lack thereof to adapt and accommodate their instructions and interactions to meet the needs of a culturally diverse student body. Items on this scale include “It is unfair to expect teachers to adapt their teaching for students with different cultural backgrounds.” The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale is .69.

Mastery- and performance-focused approaches to teaching. The eight-item scale assessing preservice teachers’ mastery-focused approaches to teaching examined the extent to which they reported that they would emphasize effort, understand-ing, improvement, and enjoyment of learning in their class-rooms (Cronbach’s α = .81). The scale includes items such as “I will stress the importance of understanding the work and not just memorizing it.”

The six-item scale assessing preservice teachers’ performance-focused approaches to teaching examined the extent to which teachers believed they would emphasize competition and social comparison in their classrooms (Cronbach’s α = .88). The scale includes such items as “I will help students understand how their performance compares to others.”

Promoting respect and collaboration in the classroom. Pro-moting respect in the classroom and promoting collaboration are both five-item scales with Cronbach’s alphas of .87 and .80, respectively. Promoting respect in the classroom includes such items as, “I will talk to students in my classes about supporting and caring for each other.” Items on the scale measuring preservice teachers’ intent to promote col-laboration include items such as “I will allow students to use class time to discuss their work with each other.”

Preservice teachers’ self-efficacy. This five-item scale assesses preservice teachers’ beliefs regarding their ability to have a positive impact on students’ learning and promote students’ achievement and academic progress (Cronbach’s α = .71). The scale includes items such as “If I try really hard, I will be able to get through to even the most difficult student in my class.”

Analyses and ResultsRelationship Between Preservice Teachers’ Attitudes and Beliefs Toward Diversity and Proposed Instructional Practices (Cross-Sectional Data)

Correlations among variables are presented in Table 1. Preservice teachers who held stereotypical beliefs about minority students were also significantly more likely to hold such beliefs about students from lower socioeconomic status (r = .68, p < .001). Discomfort with student diversity was significantly positively correlated with preservice teachers’ stereotypical beliefs regarding minority (r = .47, p < .001)

Kumar and Hamer 169

and LSES (r = .48, p < .001) students. Belief that minority students should assimilate into mainstream culture was significantly positively associated with prejudicial beliefs about minority (r = .32, p < .001) and LSES (r = .45, p < .001) students and significantly positively related to discom-fort with student diversity (r = .52, p < .001). Endorsement of mastery-focused instructional strategies was significantly negatively associated with stereotypic beliefs about minority (r = –.19, p < .001) and LSES (r = –.30, p < .001) students, and discomfort with student diversity (r = –.21, p < .001); endorsement of performance-focused strategies was posi-tively associated with stereotypic beliefs about minority (r = .23, p < .001) and LSES (r = .34, p < .001) students, and discomfort with student diversity (r = .26, p < .001). A dis-inclination to adapt instruction to the needs of individual students was significantly positively associated with professed

use of performance-focused strategies (r = .26, p < .001) and significantly negatively associated with proposed use of mastery-focused strategies (r = –.38, p < .001) promoting mutual respect (r = –.36, p < .001) and collaboration (r = –.25, p < .01) in the classroom.

Comparison of Attitudes, Beliefs, and Proposed Instructional Practices, and Teacher Efficacy Across Program Level Based on Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Data

Results of one-way ANOVA based on the cross-sectional data are presented in Table 2, and the results of paired-sample t tests based on longitudinal data are presented in Table 3.

Table 1. Correlation Among Variables (n = 784)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Stereotype (minority) 1 Stereotype (SES) 0.68 1 Discomfort with diversity 0.47 0.48 1 Assimilation 0.32 0.45 0.52 1 Mastery-focused practices −0.19 −0.30 −0.21 −0.43 1 Performance-focused practices 0.23 0.34 0.26 0.18 −0.36 1 Unwillingness to adapt instruction 0.32 0.28 0.35 0.32 −0.38 0.26 1 Promoting respect −0.26 −0.19 −0.28 −0.18 0.73 −0.38 −0.36 1 Promoting collaboration −0.22 −0.15 −0.17 −0.14 0.65 −0.24 −0.25 0.56 1.00Teaching efficacy −0.30 −0.35 −0.33 −0.24 0.58 −0.46 −0.46 0.50 0.37

Note: SES = socioeconomic status. All correlations were significant at p < .001 level.

Table 2. One-Way ANOVA Comparing Attitudes, Beliefs, Proposed Instructional Practices, and Teacher Efficacy Across Program Level Based on Cross-Sectional Data (n = 784)

M (SD)

OS (first year

in the program)SDS (midway through

the program)STS (final year

in the program) F value

Stereotype (minority) 2.33a (.78) 2.27 (.67) 2.16a (.64) 3.73*Stereotype (SES) 2.65a (.79) 2.56 (.67) 2.46a (.64) 3.98*Discomfort with diversity 2.40a (.54) 2.34 (.57) 2.14a (.52) 14.47***Assimilation 2.63a,b (.67) 2.49b,c (.64) 2.34a,c (.59) 11.10***Mastery-focused practices 4.02a,b (.55) 4.26b (.52) 4.18a (.51) 12.43***Performance-focused practices 2.44a,b (.66) 2.12b (.60) 2.08a (.52) 23.86***Unwillingness to adapt instruction 2.37a,b (.57) 2.12b (.53) 2.08a (.56) 17.70***Promoting respect 4.16a,b (.71) 4.43b (.61) 4.36a (.60) 10.99***Promoting collaboration 3.85a,b (.68) 4.12b (.66) 4.09a (.65) 11.09***Teaching efficacy 3.66a,b (.47) 3.82b (.49) 3.75a (.44) 6.99***

Note: OS = Orientation Seminar; SDS = Schooling and Democratic Society; STS = Student Teaching Seminar; SES = socioeconomic status.aSignificant differences between OS and STS preservice teachers.bSignificant differences between OS and SDS preservice teachers.cSignificant differences between SDS and STS preservice teachers.*p < .05.** p < .01.***p < .001.

170 Journal of Teacher Education 64(2)

One-Way ANOVA: Mean Differences in Beliefs and Proposed Instruction Practices Across Program Levels (Cross-Sectional Data)

One-way ANOVA yielded main effects for program level on preservice teachers’ stereotype beliefs regarding minority students, F(2, 781) = 3.73, p < .03; LSES students, F(2, 781) = 3.98, p < .02; discomfort with diversity, F(2, 781) = 14.47, p < .001; and the belief that minority students should assimilate into mainstream culture, F(2, 781) = 4.48, p < .001. One-way ANOVA also yielded main effects for program level on preservice teachers’ endorsement of mastery-focused practices, F(2, 781) = 12.43, p < .001; performance-focused practices, F(2, 781) = 23.86, p < .001; unwillingness to adapt instruction for culturally diverse students, F(2, 781) = 17.70, p < .001; promoting respect, F(2, 781) = 10.99, p < .001; and collaboration in the class-room, F(2, 781) = 11.09, p < .001; and feelings of efficacy as teachers, F(2, 781) = 6.99, p < .001.

Scheffe’s post hoc comparisons revealed significant mean differences between OS and STS preservice teachers across all variables (Table 2). On average, OS preservice teachers were significantly more likely to be biased toward minority and less affluent students and to endorse less adaptive class-room instructional practices compared with STS preservice teachers. OS preservice teachers were also significantly more likely to believe that minority students should com-pletely assimilate into mainstream culture and to endorse less adaptive classroom instructional practices compared with SDS preservice teachers. SDS and STS preservice teachers reported feeling significantly more efficacious in the teaching role than did OS teachers.

Paired t-Test Analysis: Change in Beliefs and Proposed Instruction Practices (Longitudinal Data)

The mean change over time in preservice teachers’ beliefs toward diversity, proposed mastery-focused practices, unwillingness to adapt instruction for culturally diverse stu-dents, promoting respect and collaboration in the classroom, and feelings of efficacy from SDS to STS (Table 3) follow a similar trend as the reported results based on cross-sectional data (Table 2). However, some of the nonsignificant mean differences obtained from the cross-sectional comparisons (Table 2) were significant when examining mean change over time as preservice teachers transitioned from SDS to STS (Table 3).

There was no significant mean change from SDS and STS in preservice teachers’ stereotypic beliefs toward minority students. However, transition to STS was associated, on average, with a significant decrease (t = 2.35, p < .01) in stereotypic beliefs toward LSES students. There was a sig-nificant decrease in preservice teachers’ preference for mastery-focused goals (t = 2.08, p < .01) and a significant increase in their preference for performance goals (t = –2.44, p < .01) as they moved into STS. On average, preservice teachers felt less efficacious (t = –4.95, p < .01) and were less likely to report that they would promote respect in their classrooms (t = 2.49, p < .01) when they moved from SDS into STS.

Cluster Analysis of Cross-Sectional DataCluster membership based on preservice teachers’ attitudes

and beliefs regarding student diversity. Cluster analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between preservice teachers’ attitudes and beliefs toward student diversity and their projected approaches to teaching and classroom inter-action and their feelings of efficacy as prospective teachers. To this end, an R-type cluster analysis was conducted using, as the clustering variables, stereotypical beliefs regarding minority and less affluent students, their beliefs regarding assimilation, and their discomfort in interacting with cultur-ally diverse students. The four measures were converted to standardized scores with standardized means and variances (M = 0, SD = 1; Hair & Black, 2000) to increase the stability of the cluster analysis.

A two-stage cluster analysis was performed that com-bined hierarchical clustering using Ward’s method, followed by cluster optimization by the k-means algorithm (Asendorph, Borkenau, Ostendorf, & van Aken, 2001). The groupings that result from cluster analyses are often unstable. Thus, the sample was randomly divided into half samples and separate hierarchical analyses (using both Ward’s method and nonhi-erarchical k-means algorithm) were conducted for both of these subsamples. Examination of the agglomeration tables, the dendograms, and the interpretability of the cluster

Table 3. Paired-Sample t test: Change in Attitudes, Beliefs, and Proposed Instructional Practices, and Teacher Efficacy Based on Longitudinal Data (n = 79)

M (SD)

SDS (Time 2) STS (Time 3) t test

Stereotype (minority) 2.25 (.59) 2.16 (.60) nsStereotype (SES) 2.53 (.55) 2.34 (.61) 2.35**Discomfort with

diversity2.29 (.54) 2.18 (.60) ns

Assimilation 2.39 (.56) 2.28 (.59) nsMastery-focused

practices4.39 (.42) 4.25 (.54) 2.08*

Performance-focused practices

2.08 (.52) 2.24 (.67) −2.44**

Unwillingness to adapt instruction

2.01 (.50) 1.99 (.59) ns

Promoting respect 4.57 (.50) 4.38 (.65) 2.49***Promoting

collaboration4.31 (.48) 4.18 (.57) ns

Teaching efficacy 3.94 (.43) 3.67 (.46) 4.95***

Note: SES = socioeconomic status.*p < .05.**p < .01.***p < .001.

Kumar and Hamer 171

Table 4. Means and Standard Deviations of Clustering Variables in the Three Clusters (Cross-Sectional Data)

Stereotypic beliefs about minority

students

Stereotypic beliefs about low-SES

studentsDiscomfort with

diversity Assimilation

M SD M SD M SD M SD

Cluster 1 (n = 214) 1.55 .40 1.84 .48 1.76 .42 2.01 .56Cluster 2 (n = 373) 2.24 .40 2.58 .44 2.33 .37 2.44 .48Cluster 3 (n = 197) 3.04 .52 3.25 .53 2.80 .47 3.04 .56

Note: SES = socioeconomic status.

1.00

1.50

2.00

2.50

3.00

3.50

4.00

4.50

5.00

Discomfort withdiversity

Stereotype beliefsabout minority

students

Stereotype beliefsabout low SES

students

Assimila�on

Cluster 1

Cluster 2

Cluster 3

Very true

Somewhattrue

Not atall true

Figure 2. Mean of clustering variables for the three clustersNote: SES = socioeconomic status.

solutions indicated that both half samples were best repre-sented by three clusters. The selected cluster solution was further cross-validated. Participants in each randomly selected half were cross-classified according to their similar-ity to clusters in the opposite half (based on squared Euclidean distances). Cohen’s kappa of .83 and .85 in the two cross-classified subsamples indicate a very good fit for the three-cluster solution (Asendorph et al., 2001).

The final clusters used in later analyses included the following:

1. A group that experienced the lowest levels of neg-ative stereotypical beliefs regarding minority and less affluent students, the lowest level of discom-fort in interacting with culturally diverse students, and much lower-than-average beliefs that minority students should assimilate into the mainstream cul-ture (Cluster 1: 29.30%).

2. A group that experienced average levels of stereo-typical beliefs regarding minority and less afflu-ent students, average belief that minority students should assimilate into the mainstream culture, and an average level of discomfort in interacting with culturally diverse students (Cluster 2: 45.57%).

3. The group that experienced highest levels of stereo-typical beliefs regarding minority and less affluent students, experienced highest level of discomfort in interacting with culturally diverse students, and more strongly endorsed the belief that minority stu-dents should assimilate into the mainstream culture (Cluster 3: 25.13%).

Means and standard deviations for the clustering vari-ables within each cluster are presented in Table 4. Figure 2 presents the profile for each of the three clusters.

Two-Way ANOVA: Examining the Main and Interactive Effects of Cluster Membership and Level in Program

A 2 × 2 (Cluster membership × Level in program) factorial ANOVA tested the effects of cluster membership and level in program on their projected mastery- and performance-focused

approaches to instruction, unwillingness to adapt instruction for culturally diverse students, promoting respect and col-laboration in the classroom, and feelings of efficacy as teachers. Results indicated a significant main effect for clus-ter membership. In Table 5, we present the means, standard deviations, and the F statistics for the dependent variables for the three cluster groups. The main effects of level in program parallel the results reported in Table 2. There was no significant interaction between cluster membership and level in program for any of the dependent variables.

Mastery-focused approaches to instruction. Results from univariate ANOVA point to significant mean differences among clusters, F(df = 2, 772) = 27.78, p < .001; η2 = 6.8%, and level in program, F(df = 2, 772) = 13.82, p < .001; η2 = 3.5%, in preservice teachers’ projected adoption of mastery-focused instructional and classroom practices. Pairwise comparisons indicated that preservice teachers in Cluster 1 were, on average, significantly more likely to report their preference for mastery-focused approaches to instruction compared with preservice teachers in Clusters 2 and 3. Pre-service teachers in Cluster 2 were, on average, significantly more likely to report their preference for mastery-focused approaches to instruction compared with preservice teachers in cluster 3.

172 Journal of Teacher Education 64(2)

Table 5. Means and Standard Deviations of Proposed Instructional Practices and Teacher Efficacy in the Three Clusters

Mastery-focused practices

Performance-focused practices

Unwillingness to adapt instruction

Promoting respect

Promoting collaboration

Teaching efficacy

M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD

Cluster 1 (n = 214) 4.40 .52 1.88 .59 1.84 .52 4.57 .59 4.24 .70 4.02 .47Cluster 2 (n = 373) 4.13 .51 2.22 .56 2.18 .48 4.34 .59 4.02 .63 3.71 .41Cluster 3 (n = 197) 4.00 .52 2.48 .56 2.51 .53 4.10 .70 3.87 .64 3.57 .46

Performance-focused approaches to instruction. Cluster membership, F(df = 2, 772) = 50.97, p < .001, and level in the program, F(df = 2, 329) = 18.39, p < .02, were both sig-nificantly predictive that preservice teachers would adopt performance-focused instruction. Cluster membership explained 11.8% (η2) of the variance and level in program explained 4.6%t (η2) of the variance in preservice teachers’ reported adoption of performance-focused goals for instruction.

Pairwise and post hoc comparisons revealed that on aver-age, preservice teachers in Cluster 1 reported that they would engage in significantly less performance-focused instruc-tional practices than both Clusters 2 and 3.

Unwillingness to adapt instruction to culturally diverse stu-dents. Results indicated significant differences among clus-ters, F(df = 2, 775) = 82.54, p < .001, η2 = 17.6%, and level in program, F(df = 2, 775) =12.00, p < .001, η2= 3.0%, in preservice teachers’ reported unwillingness to adapt their instruction to meet the needs of a diverse student body. Clus-ter 1 members reported the least unwillingness and Cluster 3 members reported the most unwillingness to adapt instruc-tion to the needs of culturally diverse students.

Promoting respect and collaboration in the classroom. Here again, cluster membership was significantly predicative of preservice teachers’ desire to promote respect, F(df = 2, 775) = 23.65, p < .001, η2 = 5.8%, and collabora-tion, F(df =2, 775) =11.46, p < .001, η2 = 2.9%, in the class-room. Preservice teachers in Cluster 1 were significantly more likely to promote respect and collaboration than the other two clusters, and preservice teachers in Cluster 2 were significantly more likely to do so than Cluster 3 members. Level in program also yielded significant main effects on pre-service teachers’ desire to promote respect, F(df = 2, 775) = 11.82, p < .001, η2 = 3.0%, and collaboration, F(df = 2, 775) = 11.80, p < .001, η2 = 3.0%, in the classroom.

Feelings of efficacy as prospective teachers. Univariate ANOVA results revealed significant mean differences among clusters, F(df = 2, 772) = 53.51, p < .001, η2 = 12.3%, and level in program, F(df = 2, 772) = 9.09, p < .001, η2 = 2.3%, in preservice teachers’ feelings of teaching efficacy. Cluster 1 preservice teachers experienced, on average, significantly higher feelings of efficacy compared with preservice teachers

in the other two clusters. Cluster 2 preservice teachers were significantly more likely to feel a sense of efficacy in their role as teachers compared with Cluster 3 preservice teachers.

Overall, these results indicate that preservice teachers who were less prejudiced in their beliefs about poor and minority students, did not believe culturally diverse students should completely assimilate into mainstream culture, and reported less discomfort in interacting with diverse students were, on average, more likely to endorse mastery-focused goals, promote respect and collaboration in class, and report feeling greater efficacy in prospective teaching roles. They were also less likely to endorse performance-focused goals and less likely to consider it problematic to adapt their instruction to culturally diverse students.

DiscussionThis study uses cross-sectional and longitudinal data to examine the interrelated nature of preservice teachers’ biases and beliefs regarding culturally diverse students—including minority and LSES students—and the kind of instructional practices and policies they are likely to pursue. This study, as a consequence of its sequential data-collection design, tests the effectiveness of teacher education programs in changing preservice teachers’ beliefs and attitudes regard-ing diversity and proposed classroom practices from the time they enter the teacher-licensure program to the time they complete the program and join the teaching profession.

The results of this study give us some reassurance and hope. Our findings support the hypothesis that the learning that occurs in a teacher-licensure program positively shapes preservice teachers’ attitudes toward culturally diverse stu-dents and encourages them to adopt adaptive classroom practices. ANOVA results based on cross-sectional data pro-vide evidence that preservice teachers were significantly less biased and prejudiced by the time they were ready to gradu-ate from the teacher education program than they were dur-ing their 1st year in the program. During their tenure in the teacher education program, preservice teachers recognized the importance of maintaining a respectful and collaborative environment in the classroom—one that is open to different ways of thinking— and became aware of the pitfalls of nor-mative social comparisons among students. In short, STS preservice teachers compared with OS preservice teachers

Kumar and Hamer 173

demonstrated increased recognition of the need to main-tain learning environments that validate and empower all students.

However, paired t-test results based on longitudinal data comparing students’ attitudes and proposed classroom prac-tices as they move from SDS to STS tell us a slightly differ-ent story. While the spirit of democracy, the importance of critical thinking and self-reflection introduced in the SDS course (Campbell, 2010) is reflected in preservice teachers’ increased desire to promote respect and collaboration in their classrooms and adapt instruction for a culturally diverse stu-dent body, and in their desire to encourage students to focus on critical thinking as a means to growing in knowledge and moving away from social comparisons with their peers, some of these gains seem to dissipate by the time students complete their STS. Thus, findings from cross-sectional data analysis indicate that overall experiences in the teacher edu-cation program do have a positive impact on preservice teachers’ attitudes and proposed classroom behaviors and practices. However, as seen from the results of longitudinal data analysis, when preservice teachers’ learning is put to the test, the stresses associated with first-time field experiences in schools diminish their capacity for critical thinking and self-reflection. This suggests that it is important for teacher education programs to explore the possible benefits of add-ing additional multicultural courses, with a similar focus, especially in the latter part of the teacher education program and perhaps even into the induction period.

Results of the study also indicate cause for concern. More than 25% of preservice teachers in this study explicitly endorse stereotypic beliefs about poor and minority students. At a time when schools are becoming increasingly diverse, a high percentage of prospective teachers reported feeling uncomfortable with student diversity. These findings sug-gest that preservice teachers require additional support to engage in self-reflection that will bring to consciousness their often-unconscious attitudes and belief systems and enable them to honestly understand and acknowledge per-sonal prejudices. This additional support may encourage development of a multicultural professional identity that will enable teachers to critically reflect on and rethink attitudes, beliefs, and actions and to become aware of how cultural identity influences their classroom behaviors and instruc-tional practices. Such critical reflection will also enhance their efficacy in meeting needs of all students.

This study provides empirical evidence—based on insights drawn from multicultural education and achieve-ment goal theory—that predicts the relationship between preservice teacher beliefs regarding student diversity and the instructional strategies they are likely to adopt as teach-ers. Preservice teachers who believed that all students can succeed regardless of background, and preservice teachers who stated that they looked forward to working with cultur-ally diverse students and were confident that they could establish a rapport with them, were more likely to endorse mastery-focused achievement goals. In contrast, preservice

teachers who held biased beliefs about poor and minority students felt a certain discomfort in working with students who did not share their culture, were convinced that it is hard for a teacher to establish rapport with students from diverse backgrounds, and were more likely to indicate that they would adopt performance-focused instructional goals in their classrooms.

The results of this study also provide evidence for some of the underlying reasons why teachers and preservice teach-ers endorse mastery- or performance-focused instructional strategies. Preservice teachers’ cluster membership based on the levels of stereotypical beliefs regarding minority and less affluent students, discomfort in interacting with culturally diverse students, and the belief that students should assimi-late into mainstream culture explained 6.8% and 11.8% of the variance in their endorsement of mastery- and performance-focused instructional practices, respectively. The reason for this shared variance between cluster membership and mastery-focused practices may be attributable to the extent to which preservice teachers’ possess the capacity for critical thinking and self-reflection. Preservice teachers who are capable of honest and critical self-reflection regarding their biases (Cluster 1) are likely to carryover these qualities to their classroom behaviors and to their interactions with stu-dents. They are less likely to have biased achievement and motivation expectations of their students (Jussim & Harber, 2005; Tennenbaum & Ruck, 2007). In addition, the results suggest that preservice teachers with a more open mind-set are more likely to engage in more reflective teaching prac-tices, encouraging their students to be thoughtful and critical consumers of knowledge—a hallmark of mastery-focused instructional practices.

By the same token, the shared variance between cluster membership and performance-focused instructional prac-tices may be attributable to a mind-set that is more inflexible and rigid. Endorsement of stereotypes is an indirect endorse-ment of ranking individuals as inferior or superior based on group membership. Such conviction in the accuracy of nega-tive stereotypes is likely to carryover into classroom prac-tices such as encouraging students to strive for superiority over others—a hallmark of performance-focused practices. The data suggest that teachers with this mind-set may feel justified in ranking students from best to worst based on pre-determined normative criteria where a student’s success is dependent on the success or failure of other students in the class.

Researchers in general, and achievement goal theorists in particular, have bemoaned the fact that U.S. schools encour-age social comparison in the classroom and do not recognize students for taking risks, engaging in challenging tasks, and focusing on learning and improvement. They encourage teachers to engage in mastery-focused practices by pointing out the beneficial and positive effects of mastery-focused environments and the negative effects of performance-focused environments on students’ psychological and academic out-comes (Kumar, Gheen, & Kaplan, 2002; Maehr & Midgley,

174 Journal of Teacher Education 64(2)

1996; Roeser, Midgley, & Urdan, 1996). As a consequence of viewing this phenomenon through the dual lens of multicul-tural education and achievement goal theory, this study sug-gests that teachers and preservice teachers are not likely to shift to classroom practices that are more mastery-focused and less performance-focused unless there is a fundamental shift in their mind-set and outlook from one of close-mindedness to one of openness toward all aspects of diversity—physical, social, cultural, and cognitive.

An outcome of using theoretical frameworks from both multicultural education and educational psychology, and making explicit how they relate to each other in framing actual classroom practice, is that it permits students and fac-ulty to see the relationship between coursework both in those disciplines, as well as the effect on practices developed in curriculum and instruction coursework culminating in student teaching (Kumar, 2003). Stereotypical beliefs are related to classroom practices and motivational techniques, as these findings suggest. Therefore, teacher education pro-grams must ensure that preservice teachers understand the relationship between multicultural education, educational psychology, and instructional methods. This can be done in a number of ways including presenting a model depicting the relationships between the three consistently throughout their education coursework. Better still, coursework could be con-sistently sequenced with the explicit instruction to students that concepts from their educational psychology course would, in their social foundations course, be put into the con-text of teaching diverse students and both would be used in their methods courses. With this move, obviously, it would be necessary to use consistent terminology and intentional redundancy to make the connections clear and to implement them, as well as to have faculty buy-in to the need for this integration and to have educational psychology and social foundations faculty teach common syllabi, with common goals and objectives and common terminology, across the multiple sections of a course. Toward this end and perhaps even more effective would be faculty from the three areas team-teaching to integrate the three disciplines through project-based approaches—an approach that is increasingly advocated within the field of education (Chibulka, Hollins, Marx, Nolen, & Woolfolk Hoy, 2011).

Limitations and ConclusionsIt is important to note that this study is specific to this par-ticular teacher education program, though to the extent that most teacher education programs include an educational psychology course and a social foundations course, as well as introductory, methods, and student teaching coursework, others may find it generalizable to other programs. This particular teacher education program had as its mission, at the time of the study, “Students at the center of their own learning, in a rich intellectual environment, characterized by choice.” Although the program aligned with state and National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education

(NCATE) standards concerning preparation of teachers to work with diverse populations, individual course curricula had not been horizontally or vertically integrated to develop any systematic approach to optimize learning about diver-sity.

Another limitation of this study is the fact that the results are based on self-reported data. Thus, it is probable that the posi-tive changes observed in preservice teachers’ attitudes regard-ing culturally diverse students may be more reflective of a greater sensitivity to socially desirable answers toward the end of the SDS course than of a real change in stereotype beliefs and comfort in interacting with culturally diverse students. This sensitivity may have diminished over time leading preser-vice teachers to revert to some degree to more traditional atti-tudes regarding diversity and to the more commonly adopted performance-focused instructional practices as observed toward the end of the STS course. Most of us are so tightly encapsulated within our own chosen discipline and area of research that we fail to incorporate relevant and important work of colleagues with different philosophical underpinnings, perspectives, and approaches to an issue. If schools are to implement reforms and improvements, educationists and researchers must reach a broader understanding and agreement on what reforms will best serve the needs of all students.

We believe that the achievement goal theory approach, focusing on a contextualized approach to students’ motiva-tions and the behavioral choices, complements the multicul-tural social-reconstructionist focus on social structures and interactions. Although multicultural education arose out of a political struggle for equality for the underrepresented minor-ity, achievement goal theory was developed by educational psychologists specifically to examine students’ motivation, learning, and performance in school-related tasks and activi-ties. However, researchers in both fields share the common vision of redefining and transforming teacher instructional practices and school policies to enhance their effectiveness for all students. It is time to make the relationships between courses and disciplines explicit and to design teacher educa-tion programs to reinforce students’ understanding of and reflection on the relationships as well as their implementation of effective practices based on that understanding.

Future studies examining the relationship among preser-vice teachers’ attitudes toward cultural diversity and their proposed instructional practices need to examine whether these relationships are mediated by factors such as preser-vice teachers’ sense of cultural responsibility and cultural sensitivity. The belief measures in this study are explicit self-reports and as such preservice teachers may be unwill-ing to report on their attitudes in an unbiased manner. In the future, it will be important to examine how implicit attitudes toward student diversity related to preservice teachers’ pro-posed instructional practices.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Kumar and Hamer 175

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, author-ship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Ames, C. (1984). Competitive, cooperative, and individualis-tic goal structures: A motivational analysis. In R. E. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation and education Vol. 1 (pp. 177-207). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student moti-vation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84, 261-271.

Ames, R., & Ames, C. (1993). Creating a mastery-oriented school-wide culture: A team leadership perspective. In M. Sashkin & H. J. Walberg (Eds.), Educational leadership and school cul-ture (pp. 124-145). Berkeley, CA: McCutchan.

Anderman, E. M., & Maehr, M. L. (1994). Motivation and middle school grades. Review of Educational Research, 64, 287-310.

Anderman, E. M., & Midgley, C. (2002). Methods for studying goals, goal structures, and patterns of adaptive learning. In C. Midgley (Ed.), Goals, goal structures, and patterns of adap-tive learning (pp. 1-53). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Asendorph, J. B., Borkenau, P., Ostendorf, F., & van Aken, M. A. G. (2001). Carving personality description at its joints: Confirma-tion of three replicable personality prototypes for both children and adults. European Journal of Personality, 15, 169-198.

Banks, J. A. (1997). Educating citizens in a multicultural society. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Banks, J. A. (2004). Multicultural education: Historical develop-ment, dimensions, and practice. In J. A. Banks & C. A. Banks (Eds.), Handbook of research on multicultural education (2nd ed., pp. 3-29). San Francisco, CA: John Wiley.

Banks, J. A. (2008). An introduction to multicultural education (4th ed.). New York, NY: Pearson.

Barry, N. H., & Lechner, J. V. (1995). Preservice teachers’ attitudes about and awareness of multicultural teaching and learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11, 149-161.

Bell, C. A., Horn, B. R., & Roxas, K. C. (2007). We know it’s service, but what are they learning? Preservice teachers’ under-standing of diversity. Equity & Excellence in Education, 40, 123-133.

Bodur, Y. (2012). Impact of course and fieldwork on multicultural beliefs and attitudes. Educational Forum, 76, 41-56.

Byrnes, D. A., & Kiger, G. (1994). Language attitudes of teacher scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 54, 227-231.

Campbell, D. (2010). Choosing democracy: A practical guide to multicultural education (4th ed.). New York, NY: Pearson.

Chibulka, J. G., Hollins, E. R., Marx, R. W., Nolen, S. B., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. E. (2011, April). The role of educational psychology in teacher education. In H. Patrick, & L. H. Anderman, (Chairs), The role of educational psychology in teacher educa-tion. Symposium conducted at the meeting of the American Edu-cational Research Association, New Orleans.

Cho, G., & DeCastro-Ambrosetti, D. (2005). Is ignorance bliss? Preservice teachers’ attitudes toward multicultural education. High School Journal, 89(2), 24-28.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Constructing 21st-century teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 57, 300-314.

DeCastro-Ambrosetti, D., & Cho, G. (2011). A look at “lookism” A critical analysis of teachers’ expectations based on students appearance. Multicultural Education, 18(2), 51-54.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256-273.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (1985). Teacher expectation and student motivation. In J. Dusek (Ed.), Teacher expectancies (pp. 185-217). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Fordham, S. (1996). Blacked out: Dilemmas of race, identity, and success at Capitol High. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Gibson, S., & Dembo, M. (1984). Teacher efficacy: A construct validation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 569-582.

Gilbert, S. L. (1995). Perspective of rural prospective teachers toward teaching in urban schools. Urban Education, 30, 290-305.

Goodwin, W. (1994). The puzzle of redesigning a preparation pro-gram in an evolving, fast changing field. Teacher Education and Special Education, 17, 260-268.

Grady, M. L. (1971). An assessment of teachers’ attitudes toward disadvantaged children. Journal of Negro Education, 40, 146-152.

Grant, C. A., & Sleeter, C. E. (1996). After the school bell rings. Washington, DC: The Falmer Press.

Hair, J. F., & Black, W. C. (2000). Cluster analysis. In L. G. Grimm & P. R. Yarnold (Eds.), Reading and understanding more mul-tivariate statistics (pp. 147-205). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Helfrich, S., & Bean, R. (2011). Beginning teachers reflect on their experiences being prepared to teach literacy. Teacher Educa-tion and Practice, 24(2), 201-222.

Hollins, E. R. (1990). Debunking the myth of monolithic white American culture; or moving toward cultural inclusion. Ameri-can Behavioral Scientist, 34, 201-209.

Hollins, E. R., & Torres-Guzman, M. A. (2005). Research on pre-paring teachers for diverse populations. In M. Cochran-Smith & K. M. Zeichner (Eds.), Studying teacher education: A report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education (pp. 477-548). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ibarra, H. (1999). Provisional selves: Experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 764-791.

Jussim, L., & Harber, K. D. (2005). Teacher expectations and self-fulfilling prophecies: Knowns and unknowns, resolved and unresolved controversies. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9, 131-155.

King, J. E., Hollins, E. R., & Hayman, W. C. (1997). Preparing teachers for cultural diversity. New York, NY: Teachers Col-lege Press.

Kumar, R. (2004). Multicultural education and achievement goal theory. In M. L. Maehr & P. R. Pintrich (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement: Vol. 13. Motivating students, improving schools (pp. 237-257). Greenwich, CT: Jai Press.

Kumar, R. (2006). Students’ experiences of home-school disso-nance: The role of school academic culture and perceptions of

176 Journal of Teacher Education 64(2)

classroom goal structures. Contemporary Educational Psychol-ogy, 31, 253-279.

Kumar, R., Gheen, M. H., & Kaplan, A. (2002). Goal structures in the learning environment and students’ disaffection from learn-ing and schooling. In C. Midgley (Ed.), Goals, goal structures, and patterns of adaptive learning (pp. 143-173). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kumar, R., Karabenick, S., & Burgoon, J. (2012, April). Mastery and performance focused practices: Teachers’ implicit atti-tudes, respect, and responsibility for resolving intergroup con-flicts. Annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Vancouver, Canada.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1993). Culturally relevant teaching: The key to make multicultural education work. In C. A. Grant (Ed.), Research and multicultural education: From the margins to the mainstream (pp. 106-121). Bristol, PA: The Falmer Press.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2000). Fighting for our lives: Preparing teach-ers to teach African American students. Journal of Teacher Education, 51, 206-214.

Larkin, J. (1995). Curriculum themes and issues in multicultural teacher education programs. In J. Larkin & C. Sleeter (Eds.), Developing multicultural teacher education curricula (pp. 1-16). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Maehr, M. L., & Midgley, C. (1991). Enhancing student motivation: A school-wide approach. Educational Psychologist, 26, 399-428.

Maehr, M. L., & Midgley, C. (1996). Transforming school cultures. Boulder, CO: Westview, Harper Collins.

Magos, K. (2006). Teachers from majority population—Pupils from minority: Results of a research in the field of Greek minority edu-cation. European Journal of Teacher Education, 29, 357-369.

Meece, J. L., Anderman, E. M., & Anderman, L. H. (2006). Class-room goal structure, Student motivation, and academic achieve-ment. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 487-503.

Midgley, C. (1993). Motivation and middle level schools. In P. Pintrich & M. L. Maehr (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement (Vol. 8, pp. 219-276). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Midgley, C., Maehr, M. L., Hicks, L., Roeser, R., Urdan, T., Ander-man, E. M., & . . .Middleton, M. (2000). Patterns of Adaptive Learning Survey (PALS). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

Nicholls, J. G. (1984). Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychological Review, 91, 328-346.

Nieto, S. (2000). Placing equity front and center: Some thoughts on transforming teacher education for a new century. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(3), 180-187.

Nieto, S. (2002). Language, culture, and teaching: Cultural per-spectives for a new century. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Oakes, J., & Lipton, M. (2006). Teaching to change the world (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Pintrich, R. R. (2000). Multiple goals, multiple pathways: The role of goal orientation in learning and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 544-555.

Pintrich, P. R., & Garcia, T. (1991). Student goal orientation and self-regulation in the college classroom. In M. Maehr & P. R. Pintrich (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement: Vol. 7. Goals and self-regulatory processes (pp. 371-402). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Pohan, C. A., & Aguilar, T. E. (2001). Measuring educators’ beliefs about diversity in personal and professional contexts. American Educational Research Journal, 38, 159-182.

Roeser, R., Midgley, C., & Urdan, T. (1996). Perceptions of the school psychological environment and early adolescents’ psy-chological and behavioral functioning in school: The mediating role of goals and belonging. Journal of Educational Psychol-ogy, 88, 402-422.

Rubie-Davis, C., Hattie, J., & Hamilton, R. (2006). Expecting the best for students: Teacher expectations and academic outcomes. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 429-444.

Sleeter, C. E. (1985). A need for research on pre-service teacher education for mainstreaming and multicultural education. Jour-nal of Educational Equity and Leadership, 5, 205-215.