Ke-ra-me-u or Ke-ra-me-ja? Evidence for Sex, Age and Division of Labour among Mycenaean Ceramicists

Transcript of Ke-ra-me-u or Ke-ra-me-ja? Evidence for Sex, Age and Division of Labour among Mycenaean Ceramicists

Routledge Studies in Archaeology

1 An Archaeology of Materials Substantial Transformations in Early Prehistoric Europe Chantal Conne11er

2 Roman Urban Street Networks Streets and the Organization of Space in Four Cities Alan Kaiser

3 Tracing Prehistoric Social Networks through Technology A Diachronic Perspective on the Aegean Edited by Ann Brysbaert

Tracing Prehistoric Social Networks through Technology A Diachronic Perspective on the Aegean

Edited by Ann Brysbaert

�� ��o����n���up NEW YORK LONDON

First published 2011 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2011 Taylor & Francis

The right of Ann Brysbaert to be identified as the author of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Typeset in Sabon by IBT Global. Printed and bound in the United States of America on acid-free paper by IBT Global.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infomration storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tracing-prehistoric social networks through teclmology : a diachronic

perspective on the aegean I edited by Ann Brysbaert. p. em. - (Routledge studies in archaeology v.3)

Includes bibliographical references and index. I. Bronze age-Aegean Sea Region. 2. Industries, Prehistoric

Aegean Sea Region. 3. Social archaeology-Aegean Sea Region. 4. Aegean Sea Region-Antiquities. I. Brysbaert, Ann .

GN778.22.A35T73 2011 939.1-dc23 2011021678

ISBNI3: 978-0-415-89616-0 (hbk) ISBN13: 978-0-203-15617-9 (ebk)

Contents

List of Figures

List of Tables Acknowledgements

Introduction: Tracing Social Networks through Studying

Technologies

ANN BRYSBAERT

1 Disentangling Neolithic Networks: Ground Stone Technology,

Material Engagements and Networks of Action

CHRISTINA TSORAKI

2 'Thou Shalt Make Many Images of T hy Gods': A Chaine

Operatoire Approach to Mycenaean Religious Rituals Based on

Iconographic and Contextual Analyses of Plaster and Terracotta

Figures

MELISSA VETTERS

3 Technologies of Sound across Aegean Crafts and Mediterranean

Cultures

MANOLIS MIKRAKIS

4 A War of Words: Comparing the Performative Cross-Craft

Interaction of Physical Violence and Oral Expression in the

Mycenaean World

KATHERINE HARRELL

5 Ke-ra-me-u or Ke-ra-me-ja? Evidence for Sex, Age and Division

of Labour among Mycenaean Ceramicists

JULIE HRUBY

vii

lX

Xl

1

12

30

48

72

89

88 Katherine Harrell

Stewart, P.J., and A. Strathern. 2002. Violence: Theory and Ethnography. New York: Continuum.

Tannen, D. 1984. Conversational Style: Analysing Talk among Friends. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Tarlea, A. 2004-2005. Playing by the rules: swords and swordfighters in the Mycenaean society. Dacia 48-49: 125-50.

Thalmann, W.G. 1988. Thersites: comedy, scapegoats, and heroic ideology in the Iliad. Transactions of the American Philological Association 118: 1-28.

Threatte, L. 1998. Book review: Hilary Mackie, Talking Trojan: Speech and Community in the Iliad. Language in Society 27 (4): 556-58.

Treherne, P. 1995. The warrior's beauty: the masculine body and self-identity in Bronze-Age Europe. Journal of European Archaeology 3(1): 105-44.

Ulf, C. 2009. The world of Homer and Hesiod. In K. Raaflaub and H. van Wees (eds.), A Companion to Archaic Greece, 81-99. Oxford: Blackwell.

Vermeule, E. 1979. Aspects of Death in Early Greek Art and Poetry. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Vlachopoulos, A.G. 2007. Mythos, Logos and Eikon: motifs of early greek poetry in the wall paintings of Xeste 3 at Akrotiri, Thera. In S.P. Morris and R. Laffineur (eds.), EPOS: Reconsidering Greek Epic and Aegean Bronze Age Archaeology, 107-18. Liege: Universite de Liege.

Voutsaki, S. 1998. Mortuary evidence, symbolic meanings and social change: a comparison between Messenia and the Argolid in the Mycenaean period. In K. Branigan (ed.), Cemetery and Society in the Aegean Bronze Age. Sheffield Studies in Aegean Archaeology 1: 41-58. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

--. 2010. Middle Bronze Age: mainland Greece. In E.H. Cline (ed.), Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean, 99-112. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Whitehead, N.L. 2004. On the poetics of violence. In N.L. W hitehead (ed.), Violence, 55-78. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

Wright, J.C. 1995. Empty cups and empty jugs: the social role of wine in Minoan and Mycenaean societies. In P.E. McGovern, S.J. Fleming and S.H. Katz (eds.), The Origins and Ancient History of Wine. Food and Nutrition in History and Anthropology, 287-309. Philadelphia, PA: Gordon and Breach Publishers.

----. 2001. Factions and the origins of leadership and identity in Mycenaean society. Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 45: 182.

---. 2004a. The emergence of leadership and the rise of civilization in the Aegean. In J.C. Barrett and P. Halstead (eds.), The Emergence of Civilisation Revisited. Sheffield Studies in Aegean Archaeology 6: 64-89. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

---. 2004b. Mycenaean drinking services and standards of etiquette. In P. Halstead and J.C. Barrett (eds.), Food, Cuisine and Society in Prehistoric Greece, 90-104. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

---. 2004c . A survey of evidence for feasting in Mycenaean society. Hesperia 73(2): 13-58.

--. 2008. Early Mycenaean Greece. In C.W. Shelmerdine (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age, 230-57. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Younger, J.G. 1998. Music in the Aegean Bronze Age. Jonsered: Paul Astri:ims Fi:irlag.

5 Ke-ra-me-u or Ke-ra-me-ja? Evidence for Sex, Age and Division of Labour among Mycenaean Ceramicists

Julie Hruby

Who made it? The question of producer identity is self-evident to any scholar attempting to work from material to culture. Defining 'who' as an individual in the Bronze Age Aegean is particularly challenging; attempts to define 'hands' have been controversial in light of a variety of challenges, including that of distinguishing a workshop from an individual (e.g. Cherry 1999). Efforts to describe ceramicists (here defined broadly as those who work with clay, regardless of the stage of the process in which they are engaged or of the identity of the product) in terms of their gender, age or social identity have been more widely attempted. For example, within the Aegean, Vitelli (1978) has addressed the gender of Neolithic potters, Nordquist (1995) the identities of Middle Helladic potters and Papadopoulos (1997: 453) has asked about potters in general, from the Neolithic through to the Classical period. Among scholars working on Cyprus, the issue of the gender of ancient potters has excited substantial debate (Hankey 1983; Walz 1985; London 1987; 2002; Clarke 2002), as it has for scholars working around the world (Marshall 1985; Wright 1991; Arnold 1985).

Because the process of producing ceramics entails many complex stages (Table 5.1), we cannot assume that a single individual or kind of individual always undertook all tasks to produce an object. This situation requires that we think about questions of gender and age in conjunction with the entire chaine operatoire. Similarly, it may prove productive to think about the production of a wide range of ceramics, such as pots, figurines, tablets and seals, in light of the broad similarities in their production sequences. For example, Kopaka (1997: 527-28) asks about male, female and 'other' genders for tablet-kneaders and scribes, and techniques developed for sexing or gendering potters may prove equally useful for tablet-kneaders or figurine-modellers.

Indeed, it remains unclear what the relationship was between potters and figurine-makers, or between potters and tablet-makers or scribes. The existence of wheel-thrown figurines brings into question whether figurines were made by the same people who made vessels, or by family members of potters or by others with easy access to prepared clay. If potters did make figurines, was the practice undertaken throughout a career, or only by the

90 Julie Hruby

Table 5.1 Stages of Production of Various Ceramic Objects

Activity Pottery Figurines

Plan and schedule activities X X

Dig clay X X

Prepare clay (pick out unwanted ele- X X ments, sieve, levigate, blend clays, add temper, wedge clay, etc.)

Form clay X X

Trim or cut object ? ?

Add adjuncts to object (handles, etc.) X X

Decorate/add information to clay ? ? (paint, incise, impress, add plastic ele-ments, alter forms, etc.)

Move object within workspace(s) ? ?

Obtain fuel X X

Load kiln X X

Fire kiln X X

Unload kiln X X

Add coatings post-firing ?

Transport finished object ? ?

Store object (move into storage, track ? ? inventory, etc.)

Market or otherwise transfer object to ? ? consumer or end-user

Tablets Sea lings

X X

X X

X X

X X

?

X X

? ?

? ?

? ?

? ?

young or the elderly? Similarly, the existence of inscribed stirrup jars forces us to acknowledge that there is a relationship between scribal work and pot-painting and to ask whether tablets were made or inscribed by potters. While the present chapter will not resolve these questions, it will present a survey of methods for addressing them, insofar as identifying the gender and age-grade of producers of a kind of ceramic object may allow us to differentiate them from each other.

An intertwined approach to sex, gender, age and the production process has great potential for the study of ancient economic and social systems, including the division of labour, the relationship between household and society and the impact of the development of economic complexity on actual human beings. These issues provide us with the opportunity to build bridges between an archaeology of issues and an archaeology of people. Therefore, developing reliable methodologies for describing ceramic workers is highly desirable.

Ke-ra-me-u or Ke-ra-me-ja? 91

Let us begin by surveying existing approaches, both from Aegean archaeology and from the wider archaeological world. First, there is limited textual evidence. Kopaka (1997: 528) points out that the Linear B word for potter, ke-ra-me-u, is found in both masculine and feminine forms. While the grammatical gender of nouns need not correspond with the gender of the individual so named, the existence of forms reflecting both genders suggests a correspondence between grammatical and actual gender, though it is possible that masculine plural forms might incorporate groups of mixed gender. There are five relevant uses of the term. At Pylos, tablet Cn 1287.4 uses the nominative singular masculine form ke-ra-me-u, tablets En 467.5 and Eo 371.A use ke-ra-me-wo, genitive singular masculine (these potters also have masculine proper names), and An 207.7 uses ke-ra-me-we, a nominative dual. At Mycenae, tablet Oe 125 uses ke-ra-me-wi translated by Bennett et al. (1958: 111) as 'for the potter', though Aura Jorro (1999: 345) sees this as a personal name. The sole feminine form is from Knossos, where tablet Ap 639 lists ke-ra-me-ja among a list of proper names.

On the mainland, the weight of textual evidence leans toward male potters; on Crete, we may ask whether ke-ra-me-ja is a female potter, merely has a proper name that evokes a (formerly?) female craft, is a foreigner (from a place where she had been a potter?) or a potter's wife; if the last, might she have been engaged in related tasks like pottery distribution (Kopaka 1997: 528)? We have no tools to differentiate among these possibilities. There may be a distinction between male potters on the mainland and a female one on Crete, but the sample size is too small to justify firm conclusions. Furthermore, the relationship between the individuals named as potters and the production process is ambiguous. Were they the heads of workshops filled with assistants or apprentices, male or female? Heads of family workshops? Or sole producers?

The iconographic evidence is equally ambiguous. There is no Bronze Age equivalent to the Classical Caputi hydria, depicting a potter's workshop in which three men and one woman paint vessels (Papadopoulos 1997: 453). Minoan seals depict both males and females with pots, but it is not clear what they are doing with them (Kopaka 1997: 528). Nor is there any activity depicted on Mycenaean ceramics that can be identified as reflecting knowledge that must have been available only to members of one gender, which would identify pot-painters as members of that gender (cf. Hegmon and Trevathan 1996).

A third approach is to extrapolate from other ancient, geographically proximate societies. Kopaka (1997: 528) refers to ancient Cyprus, but the argument is based on a modern ethnographic analogy, and it seems problematic to base an understanding of Mycenaean potters' gender on that of 20'hcentury Cypriot potters. Kopaka (1997: 528) and Walz (1985: 129) both invoke depictions of male potters from ancient Egypt and the Near East. However, the textile industry gives warning that such an extrapolation is unreliable; while the Egyptian textile industry workers were predominantly

92 julie Hruby

masculine, the Mycenaean ones seem, on the basis of textual evidence, to have been predominantly feminine (Barber 1991: 113-15, 272-73).

A fourth approach, ethnographic analogy, has been used in two different ways. One is the argument that, because later traditional potters working in a place were of a specific gender, earlier ones probably were too. Hankey (1983) suggested that this might be the case on Cyprus, where she was familiar with 20'h-century female potters. Walz (1985: 127 ) rebutted her proposition, claiming that to make such an argument, one would need to demonstrate continuity of tradition.

A second approach to ethnographic analogy looks at cross-cultural commonalities. A long history of scholarship associates domestic, unspecialised production with women and specialised workshop production (and the potter's wheel) with men (D. Arnold 1985; P. Arnold 2000: 108). For example, Vitelli (1978) notes that a pattern of female potters (long before the introduction of the wheel) engaging in patrilocal exogamy would explain the stylistic continuities and ranges of variation she sees in the Neolithic pottery from Franchthi and Lerna, and Hankey (1983) suggests that Cypriot pottery was technically conservative because it was made by women who were too busy to master new skills such as the wheel.

There are problems with the use of such cross-cultural commonalities. Wright has argued that they may not actually exist; she finds evidence of bias on the part of the ethnographic observers who have produced ou·r sense of how things 'always' are done (1991: 196). Also, there are many counterexamples where women have functioned as commercial potters, such as the Jutland potters, who produced for markets (Nordquist 1995: 204), and the women who worked in England's North Staffordshire potteries (Sarsby 1988).

The most substantial objection to the use of ethnographic analogy to assign gender to potters, however, comes from a consideration of the entire chaine operatoire. Many people may be involved in production, not just the potter who forms a vessel. Production processes are numerous, timeconsuming and complex (see Table 5.1). Wright establishes that:

in virtually all studies of pottery production, the word p otter has been equated with the person who forms pots, that is with the person who shapes the clay while it is in its plastic state. This means that individuals who perform other tasks in the production sequence . . . are not counted as 'potters' despite Kramer's finding (1985:84) that potters sometime work in groups, and that often different parts of a production sequence are executed by more than one individual. (1991: 198)

As a result, either men or women (and also children) may be excluded from descriptions of potters' work, which focus on the individual at the expense of the group. Certainly there are many contemporary examples of ceramic labour being divided among members of a family or mixed-sex group. London

Ke-ra-me-u or Ke-ra-me-ja? 93

describes modern potters at Kornos on Cyprus as women but points out that they have not always been exclusively female and that men are 'usually involved with clay digging, preparing, and firing' and surface finishing (1987: 321). Nixon's comment seems apropos: 'it is traditional to think in terms of the division of labor, but we might like to think instead about the integration of labor' (1999: 564). A tendency toward gender integration of labour may be especially pronounced in times of economic stress (Mills 1995).

Since these approaches have effectively warned against oversimplification but have borne little fruit for identifying producers, let us turn to promising approaches not yet used by scholars working in the Aegean. One is spatial analysis: Wright asks whether pottery production is integrated into domestic space, likely involving women. Small units 'are at least suggestive of producers related through family or close community ties' (Wright 1991: 211), though the reverse is not true, since nucleated workspaces may include women. Unfortunately, as London (2002) points out, pottery production in domestic spaces tends to use less equipment than that done in workshops and is therefore less visible. Nonetheless, the location of workshops in closer proximity to residences might suggest familial involvement, since siting workshops and kilns further from settlements and closer to sources of firewood, clay and water would otherwise makes sense. Perhaps the relative paucity of recovered Mycenaean ceramic production sites reflects their distance from settlements (Hasaki 2002: 186-218).

Another criterion that has been used in determining gendered division of labour is the compatibility of tasks with child rearing, initially suggested by Brown (1970: 1074). Murdock and Provost, in a cross-cultural study of gender and work, find that the vast majority of potters are female; they cite Brown as providing a rationale (1973: 207, 211). However, there are problems with this argument. First, pottery production is not particularly compatible with rearing young children. Children can damage pottery (London 2002: 267), and firing entails dangerously hot temperatures; replication experiments suggest that Mycenaean fine-wares were typically fired around 700-1100 degrees Celsius (Galaty 1999: 36). Second, as Nosch (2003: 16) points out, women often do undertake labour that is 'incompatible' with child rearing; cooking over an open fire is dangerous. Finally, child rearing is not always the sole responsibility of mothers (Wright 1991: 200-201). Therefore, it is not clear that this criterion is useful.

This survey of traditional approaches to understanding what kinds of people were potters demonstrates that we have learned more about what we do not know than about what we do. While we know that most Mycenaean potters attested textually are male (perhaps all?), we do not know what that means, nor do we know what gender ceramicists who created other products might have been. We have no textual or iconographic evidence telling us anything about scribes or figurine-makers. Indeed, we still do not know whether these producers were the same people who formed vessels. We do know that in some cultures, children and adolescents have engaged in

94 Julie Hruby

aspects of production as they have learned the craft (Arnold 1999; Crown 2007: 678), but we remain ignorant about the age range of Mycenaean producers. In short, we do not yet understand the roles of different people or kinds of people engaged in production or other parts of the chaine operatoire for vessel or other ceramic craft production, nor do we know what kinds of interactions there might have been among practitioners.

Some studies, however, have used analysis of impressed fingerprints to shed light on the identities and organisational structure of ancient ceramic workers. A few have done so by matching prints to identify individuals. For example, Sjoquist and Astrom's (1985) study of the prints from the Palace of Nestor at Pylos found that identifiable individuals formed the tablets, and that the tablets formed by single individuals did not all have the same handwriting. This enabled them to propose that the scribes did not form the tablets. Analysis of matching fingerprints from a late 5'h-century dump in Metapontum also shows that the 'Dolon Painter' workshop included one individual who modelled clay, two who painted pots and one who touched up damage (Holden 1997). While the rewards of successful studies are substantial, challenges should not be underestimated. The preservation of sufficient portions of prints for matching is contingent on a number of factors, including the wetness of the clay, the care taken by the producer and the size of the sample of sherds (Branigan et al. 2002).

Analysis of characteristics of individual prints has also hinted at iden·tities of ceramic producers. Print size correlates with both sex and age: smaller prints with narrower lines are more characteristic of children than adults and of females than males, while larger prints with broader lines are more characteristic of adult males (see the following). An experienced analyst, therefore, can guess with some accuracy that a print belongs to a child, or to an adult male, though differentiating adult females from juveniles is difficult. In Hallager's (1996: 242) study of Minoan roundels, for example, an examiner identified the fingerprints on KN We 44 as likely to belong to a woman or child. Similarly, a team identified a fingerprint impressed in the back of the Gravettian Venus of Dolnf Vestonice as having comparable size and ridge breadths to what a print from a modern child of between 7 and 15 years would have (Kralfk et al. 2002), though because children might have grown more slowly or to smaller sizes in the Palaeolithic than they do today, the estimate may be low. At the opposite end of the age range, it has been hypothesised on the basis of fingerprint wear that some Knossos tablets were shaped by retired potters (Olivier, Astrom and Sjoquist, cited in Kopaka 1997: n. 44).

Promising studies, however, have examined populations through samples of prints, often partial (e.g. Kamp et al. 1999; Jagerbrand et al. 2006). A variety of print attributes are age- or sex-linked (or both) in modern populations. Several new approaches, including frequency of white lines, frequency of interpapillary lines and ridge to valley thickness ratio (RTVTR), have been discovered recently. Badawi et al. (2006)

Ke-ra-me-u or Ke-ra-me-ja? 95

found a highly significant correlation in a modern population between female sex and the presence of white lines (linear depressions that cross ridge detail), though there are individual women without them and men who have them, so they cannot be used to sex individual prints. Roehling et a!. (2001) and Stucker et al. (2001) found interpapillary lines, which are smaller and shallower lines that can appear between ridges, to both increase in frequency over a lifetime and to be found more commonly in the prints of men than in those of women. Badawi et al. (2006) found a highly significant correlation a modern population between female sex and a higher RTVTR, the metrical ratio between the widths of ridges and the widths of valleys.

There are a number of issues that will need to be resolved before these factors will be useful in an archaeological context. Further experimentation is needed to determine whether sex differences detected in modern populations reflect biological sex or hand muscularity, since if they represent the latter, they may prove less useful for sexing groups within ancient populations. Presumably, potters (regardless of biological sex) have well-developed hand musculature. If any factor reflects biological sex and not muscularity, it may prove useful for sexing individuals or populations; if it reflects muscularity, it may correlate with high-intensity ceramic production, or it may suggest that the producer is engaged in other hard labour. It will also be critical to evaluate experimentally whether and how consolidants used to reinforce ceramics before casting alter metrical characteristics, and how the moisture content of the clay at the time the impression was originally formed affects metrical and shape characteristics. Furthermore, it will be necessary to determine how post-firing wear on an impressed sherd affects print characteristics.

Preceding those studies, however, the most profitable approach to both sexing and ageing print populations has been mean ridge breadth (MRB). Ridge breadth is described as 'the distance between the centre of one epidermal furrow and the centre of the next furrow along a line at right angles to the direction of the furrows' (Penrose 1968: 1). More accurate numbers can be gained by taking the mean of a number of measurements from a single print, most simply by measuring the widths of a number of lines simultaneously and dividing by the number of lines (Kralfk and Novotny 2003: 8). Note that this measure is similar to ridge density, which is based instead on the number of lines in a defined area of 25 mm2 (Acree 1999). Ridge density is less useful in an archaeological context because it requires orienting the study-area in a particular direction, often impossible with print fragments of small size and uncertain origin.

The correlation between ridge breadth and both age and sex, the latter only partially accounted for by the hand's physical size, has been documented extensively in modern populations around the world (Ohler and Cummins 1942; David 1981; and Kamali 1984 are a few of many examples). While most studies on modern populations have worked from two-

96 Julie Hruby

dimensional inked prints on paper, a few more recent studies have examined impressions in clay (Kamp et al. 1999; Kralik and Novotny 2003).

Kralik and Novotny (2003: 5) found that among prints taken from ceramic objects made by modern Czech potters and schoolchildren, an MRB of less than 0.39 mm signifies a sub-adult source (under 15 years), an MRB of greater than 0.52 mm signifies an adult male source and those MRBs between 0.39 and 0.52 are ambiguous, representing either an adult female or a juvenile (male or female) source. Their median absolute error of age estimates was 1.71 years with a standard deviation of 2.36 years, and in only 3.6 per cent of cases the error exceeded five years. One approach to differentiating a large sample of adult female prints from one of juvenile prints might be to model the expected curve shapes and levels of variability of each type of sample. MRBs of a group of adult females should be less variable and closer to a normal curve than those of a group of growing teens, since the teen sample would incorporate an additional, substantial source of variation (namely, physical growth).

However, there are a number of concerns that must be taken into account when using ridge breadth. The first is that MRB varies depending on the part of the hand that is used. Ridges on palms tend to be broader than those on fingers, and different parts of fingers have different ridge breadths (Ohler and Cummins 1942), so it is important that studies of prints on ceramics differentiate finger from palm prints. Overall, there is significant variabilit·y within the measurements on a single human's hand, which should make any scholar wary of using MRB to sex individual small print fragments, unless there is sufficient preservation to know which part of the hand is preserved. Fortunately, the prints preserved on ceramics are formed primarily by the fingertips of the thumb and index fingers, which correlate with each other closely. Kralik and Novotny (2003: 11) reach this conclusion numerically, and it is consistent with what I have seen in the field. This makes combining data from fingerprints into sample populations a reasonable choice, so long as there is no indication that the ceramics have been handled in an idiosyncratic way. Since the prints preserved on sealings tend to represent different parts of the finger than do those on pottery, however, it would be prudent to exercise care in any attempt to compare the two.

There is also some variation in MRB from population to population. While both sexual dimorphism and size variation with physical growth: are present in all populations that have been studied, the exact MRBs associated with adult females, adult males or children of any given age do vary. This suggests that it is legitimate to compare groups within a population, but problematic to compare, for example, a sample of prints from Polish adults with a sample from Yoruban adults, or a sample of ancient Mycenaeans with a sample of modern Czechs (Kralfk and Novotny 2003: 10 provide references to relevant studies). It might be reasonable to expect that variations in levels of hand muscularity might also affect MRB, insofar as hands will not gain additional ridges as they grow and should instead

Ke-ra-me-u or Ke-ra-me-ja? 97

have the ridges become more widely spaced, increasing the MRB. However, preliminary indications suggest that muscularity is unlikely to have much effect. No statistically significant difference was found in one study that compared the prints of contemporary potters with non-potters (ibid.: 22), though we might expect potters to have more muscular hands. It is not even clear that there is a significant difference in ridge breadth between older juveniles (16-19 years old) and adults (20+ years), at a time when musculature is undergoing substantial development (David 1981; Kralik and Novotny 2003: 23), so it is unlikely but not impossible that muscularity might play some role in determining an individual's MRB. It seems sensible to exercise caution when comparing prints from individuals or groups with different professions, especially in situations where one profession might result in very muscular hands and the other in much more delicate hands, but the impact of this factor should not be overstated.

Kralik and Novotny (2003: 12) have identified other factors that can complicate interpretation of metrical data, including differential clay shrinkage rates, deformation by later formation processes and deformation caused by excessive water in the clay or by a softened dermis pressing against hard clay. Certainly it is advisable to control for clay shrinkage rates as best one can, ideally by comparing prints made in the same type of clay or through finding the relevant clay sources and firing shrink tiles, 1 less ideally through identifying the densities of non-plastic inclusions and considering their theoretical impact on shrinkage. Deformation of a print by later production processes may sometimes be detectable, and visibly deformed prints should be systematically excluded from samples. The impact of those prints that might be deformed in ways that are not easily identified can be limited by using large samples whenever possible (Kralik and Novotny 2003: 26). A current study by the author and Tina Gebhart is evaluating the ways in which, and extent to which, prints are altered by excessively wet or dry clay, so it may be possible in the future to accommodate this factor.

A number of studies throughout the world have used MRB as a window into the gender and age identities of ancient ceramics producers. Kamp et al. (1999) is a particularly methodical and carefully undertaken example; see also Jagerbrand et al. (2006). One found that ridge breadths on pots excavated at the Mycenaean site of Midea that were dated to LH IIIB were significantly broader than ridge breadths on pots dated to LH IIIC, suggesting the possibility of a shift from adult male to adult female or juvenile producers (Hruby 2007). While larger sample sizes and a broader range of sites must be examined to contextualise the results from Midea, this approach to identifying gender and age of ceramicists is potentially useful.

Print analysis in general and MRBs in particular may also allow us to start thinking about relationships among those who make different kinds of ceramic objects, whether figurines, pots or administrative documents such as sealings and tablets. For example, if we were to find that adult men formed both pots and figurines, it is possible that the same people might

98 Julie Hruby

be engaging in both processes, which would in turn suggest that we should invest labour in looking for matching prints from figurines and pots. If, however, we were to discover that men formed pots and women formed figurines, it would be clear that different individuals were making pots and figurines. It would, then, be useful to ask whether both types of objects were produced in the same spaces as part of the same production contexts where people would inevitably interact socially, and what kinds of crosscraft interaction can be identified.

A third type of study that compares prints might allow us to address whether the same 'kinds' (genders and age-grades) of people engaged in different stages of the production processes. Branigan eta!. (2002: 49) note that it might be possible 'to recognise cases where two or more individuals are involved in the production of a single vessel', but were unable to find the prints to do so by matching; indeed, print matching is not well suited to such an application, since finding two different prints on two different parts of the vessel tells you only that they came from different fingers and not that they came from different individuals. Statistical comparisons of MRBs may be more useful.

As D.E. Arnold notes, task segmentation is 'an indicator of a more complex production organization' (1999: 79), so the identification of different age-grades or genders engaging in different stages of production would suggest a higher level of organisational complexity. Indeed, while it is possible to have production tasks divided among producers of the same gender and age-grade, it is common for assistants or apprentices to be family members of different gender or age. Crown, for example, argues that task segmentation can facilitate teaching the young by giving individuals increasingly challenging tasks as they learn-essentially an apprenticeship model (2007: 680).

It is not possible to use fingerprint analysis to access many of the stages of production, since activities such as digging and preparing clay, obtaining fuel, loading and firing a kiln and marketing completed ceramic goods would not produce prints. However, processes such as forming the clay, adding adjuncts such as handles and painting can all produce identifiable prints. Those prints found at handle attachments, whether inside or outside a pot, are likely to have been made by the person who attached the handle. Those found elsewhere on the interior of a vessel are likely to have been made by the person who formed the pot; those found in paint are likely to have been made by a pot-painter. By contrast, prints left on a vessel's exterior in areas other than the immediate vicinity of a handle are difficult to assign to a particular process; they may have been left by the person forming a pot, or by someone moving it from the wheel to a drying location, or by someone picking it up to attach a handle or spout. As a result, it should be possible to tentatively identify in what context some but not all prints were made, and by comparing ridge breadths from the person or people who formed pots within a unified assemblage with ridge breadths from the person or people who attached handles or painted designs, to test

Ke-ra-me-u or Ke-ra-me-ja? 99

the hypothesis that these people were different in age or gender. If they were different in age or gender, then we know that different stages of the chaine operatoire were undertaken by different people. In the future, it may then be possible to compare the data from pottery with that from other ceramic objects, such as tablets or figurines, in order to build a stronger understanding of cross-craft interactions within ceramics.

The Palace of Nestor at Pylos provides an excellent body of material for a case-study utilising this approach. The pantries (rooms 18-22) contained several metric tons of ceramic vessels, including over 3,000 kylikes, over 1,000 bowls and over 1,000 'teacups' (Blegen and Rawson 1966). All were in what appears macroscopically to have been a single, relatively consistent, fine fabric. Because the palace burned, the assemblage seems to have been in use at a single point in time, though it is possible that a few vessels had been produced earlier than the others. Most vessels are unpainted (Hruby 2006).

From 2002 through to 2010, prints from the pantries were catalogued as they were found. Among the information recorded were the MRB, which part of the hand the print came from and on which part of the pot the print was found. The data set used here has been restricted to prints identifiably from fingers, not palms, in order to reduce the risk that the part of the hand represented might become a confounding variable. For example, many of the prints at the interior of bowl rims where handles were attached are palm prints, where the handle attacher used his or her palm to brace the rim while pressing the handle against it. These cannot be compared reliably to fingerprints. It has also been restricted to the 22 print fragments that can be attributed reliably to the 'potter', the person who formed the pot on the wheel, and those 38 fragments that can be attributed to the 'handle attacher', the person who pressed the handle into the body of the pot.

If the potter or potters were substantially similar to the handle attacher or attachers in age-grade and of identical sex, the MRBs from pot formation and those from handle attachment should not be easily differentiated statistically. However, if the potter or potters are of different sexes or of substantially different age-grades from handle attacher or attachers, it is likely that their MRBs will be statistically differentiable. 2 Specifically, if the 'potter' MRB and the 'handle attacher' MRB data can be shown to have statistically different means, then they must represent people who are of different sex or age.

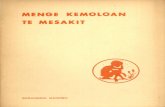

Let us look, then, at the statistics that characterise the prints. At a glance, they appear to be comparable (Figure 5.1). The mean MRB from the potter or potters is 0.47 mm (n = 22, median = 0.48, standard deviation = 0.56), while that for the handle attacher or attachers is 0.49 mm (n = 38, median= 0.50, standard deviation= 0.82). For reference, modern young adult males average approximately 0.48 mm, and modern young adult females average approximately 0.43 mm, though both numbers vary somewhat by population (Cummins and Midlo 1961: 28).

100 Julie Hruby

> (J c: <II ::1 IT 4 <II ...

u..

Handler

-

r .- -r '. -

·· ...

-I

.•. , .. I · •

I> I

Job

.

I 11111 r

-

r-

jr

I· . ••.

Potter

-

. · .

-

r--.• I•

I

3.0000 4.0000 5.0000 6.0000 7.0000 3.0000 4 .0000 5.0000 6.0000 7.0000

Width in 0.1 mm

Figure 5.1 Frequencies of MRBs of prints from potters and handle attachers.

The question, then, is whether there is a statistically significant difference between the two means. There are a number of tests that can be used to evaluate the null hypothesis, that there is no statistically significant difference between means of the two populations. Among the most common are Student's t-test and the Mann-Whitney test (Fletcher and Lock 1994: 86-89). The former is parametric, the latter non-parametric, and it is usual to use the parametric test when the assumption of normality holds because they are more powerful (ibid.: 74). However, it has been found that the Mann-Whitney test is more powerful where samples sizes are unequal (Zimmerman 1987), which is the case here.

First, we should evaluate whether the 'potter' MRB data and the 'handle attacher' MRB data are normally distributed, and if they have comparable variance; if not, Student's t-test is inappropriate (Fletcher and Lock 1994: 86-87). I have chosen a Shapiro-Wilk test to evaluate the null hypothesis, that each sample comes from a normally distributed population; if the p-value is sufficiently low, here below 0.05, we can reject that hypothesis. The sample of potters' prints has a p-value of 0.639, and that of handle attachers a p-value of 0.470, so we cannot reject the hypothesis that each comes from a normally distributed population (Shapiro and Wilk 1965). Levene's test for equality of variances (US Government's Engineering Statistics Handbook; see http:// www.itl.nist.gov/div898/handbook/eda/section3/eda35a.htm) gives an F of

Ke-ra-me-u or Ke-ra-me-ja? 101

2.271 and a significance of 0.137, also above 0.05, hence we cannot exclude the hypothesis that the two distributions have similar variances. Because the data seems to be normally distributed and of comparable variance, we use Student's t-test (two-tailed) to compare the means, which gives a significance of 0.241 (Fletcher and Lock 1994: 86-88); a Mann-Whitney U test gives a comparable result, a p-value of 0.208 (two-tailed), which means that we have not been able to show that the potter or potters were different in gender or age from those who attached handles. In other words, if the potters and handle attachers were the same people, and their prints were sampled, the samples would look as different as or more different from each other than ours do at least 20 per cent of the time. Because one typically looks for a number under 5 per cent in order to reject the idea that the two groups are the same, we cannot in good conscience suggest that they are different. 3 Figure 5.1 reinforces this idea graphically, as the two distributions of data do look like they may be drawn from the same population.

This quantitative data reinforces the author's suspicion, based on observations in the museum, that not only were the pots relatively likely to have been thrown by men, but the handles were almost certainly also attached by adult males. On the interior rim of many bowls, palm prints and fingerprints show where the handle attacher braced the rim as he attached the handles, and the handspan is very large.4 The MRBs for both potters and handle attachers are also, unsurprisingly, comparable to the MRB of 0.48 mm found at LH IIIB Midea, where the sample size was not sufficient to differentiate potters from handle attachers, and where the potters during that period are relatively likely to have been adult males (Hruby 2007: 481).

This result is disappointing, insofar as the discovery of women or children in the realm of ancient craft is desirable, and we might have hoped to find evidence that would allow us to see child apprentices or women (wives?) engaged in ceramic production at Pylos. We still may wonder if women were engaged in other stages of the process, digging and preparing clay, moving drying pots or loading and firing kilns, but we cannot yet demonstrate that they were. This attempt at finding women and children among the Pylos potters may have failed, insofar as it found evidence for neither. On the other hand, identifying gendered work roles associated with adult men may provide a useful counterpoint to those we already associate with women (namely, textile work); further, such studies from other sites, time periods or cultures may yet reveal interesting patterns and questions. In particular, if prints of comparably high MRB (or of significantly lower MRB) are found on tablets or sealings, we will have another tool for discovering the mechanics of cross-craft interactions in the Mycenaean world. So far, our best picture from Pylos and Midea of LH IIIB Mycenaean ceramic production remains palace-centred and needs further contextualisation, but it would include adult male potters throwing pottery and adding handles, with other stages of production or other ceramic crafts (Table 5.1) potentially undertaken by family members, apprentices, retired potters or the active potters.

102 julie Hruby

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank those without whom this work could not have happened: the Kalamata Ephoreia of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, the museum guards at the Archaeological Museum in Hora and Jack Davis and Shari Stocker. Generous financial support was provided by the Institute for Aegean Prehistory and Berea College. Many thanks to Ann Brysbaert for her editorial assistance, patience and advice, and to Areti Pentedeka for her thoughtfuJ comments. Statistical advice was provided by Larry Gratton and his advanced statistics students; the author alone should be held responsible for any mistakes.

NOTES

1. It is common practice for potters to form a rectangular tile of wet clay and draw a 10 em line on that tile; shrinkage rates are determined by measuring the length of that line post-firing, dividing by 10 em, subtracting from 1 and converting to a percentage.

2. See Fletcher and Lock (1994) for the relationship between statistical significance and archaeological significance, and for explanations of the statistical tests used here.

3. My thanks to Larry Gratton and his MAT 438 class for their assistance in choosing appropriate statistical approaches.

·

4. The author uses her own unusually large hands (17.3 and 18.0 em long) as a high approximation of how long women's hands are likely to be; her hands were dwarfed by those of the handle attacher(s).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Acree, M.A. 1999. Is there a gender difference in fingerprint ridge density? Foren

sic Science International 102: 35-44. Arnold, D.E. 1985. Ceramic Theory and Cultural Process. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press. ---. 1999. Advantages and disadvantages of vertical-half molding technology:

implications for production organization. In J. Skibo and G. Feinman (eds.), Pottery and People, 59-80. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Arnold, P.J., III. 2000. Working without a net: recent trends in ceramic ethnoarchaeology. Journal of Archaeological Research 8(2): 105-33.

Aura Jorro, F. 1999. Ke-ra-me-ja. In F. R. Adrados (ed.), Diccionario Micenico,

345. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientfficas. Badawi, A., M. Mahfouz, R. Tadross and R.L. Jantz. 2006. Fingerprint-based

gender classification. In H. Arabnia (ed.), Proceedings of the International

Conference on Image Processing, Computer Vision, & Pattern Recognition.

Las Vegas, Nevada: CSREA Press. Internet Edition: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/ viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.85.4082, accessed February 20, 2010.

Barber, E.J.W. 1991. Prehistoric Textiles. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Bennett, E.L., Jr, E. Wace and J. Chadwick. 1958. The Mycenae Tablets. Trans

actions of the American Philosophical Society 48 (1). Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

Ke-ra-me-u or Ke-ra-me-ja? 103

Blegen, C.W., and M. Rawson. 1966. The Palace of Nestor in Western Messenia I. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Branigan, K., Y. Papadatos and D. Wynn. 2002. Fingerprints on Early Minoan pottery: a pilot study. Annual of the British School at Athens 97: 49-53.

Brown, J.K. 1970. A note on the division of labour by sex. American Anthropologist 72(5): 1073-78.

Cherry, J.F. 1999. After Aidonia: further reflections on attribution in the Aegean Bronze Age. In P.P. Betancourt, V. Karageorghis, R. Laffineur and W.-D. Niemeier (eds.), Meletemata: Studies in Aegean Archaeology Presented to Malcolm H. Wiener as He Enters His 65th Year. Aegaeum 20: 103-10. Liege: Universite de Liege.

Clarke, J. 2002. Gender, economy and ceramic production in Neolithic Cyprus. In D. Bolger and N. Serwint (eds.), Engendering Aphrodite: Women and Society in Ancient Cyprus, 251-63. Boston, MA: American Schools of Oriental Research.

Crown, P.L. 2007. Life histories of pots and potters: situating the individual in archaeology. American Antiquity 72(4): 677-90.

Cummins, H., and C. Midlo. 1961. Finger Prints, Palms and Soles. New York: Dover Publications.

David, T.J. 1981. Distribution, age and sex variation of the mean epidermal ridge breadth. Human Heredity 31: 279-82.

Fletcher, M., and G.R. Lock. 1994. Digging Numbers: Elementary Statistics for Archaeologists. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Galaty, M. 1999. Nestor's Wine Cups: Investigating Ceramic Manufacture and Exchange in a Late Bronze Age 'Mycenaean' State. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Hallager, E. 1996. The Minoan Roundel and Other Sealed Documents in the Neopalatial Linear A Administration. Vol. 2, Aegaeum 14. Liege: Universite de Liege.

Hankey, V. 1983. The ceramic tradition in Late Bronze Age Cyprus. Report of the Department of Antiquities Cyprus: 168-71.

Hasaki, E. 2002. Ceramic Kilns in Ancient Greece: Technology and Organization of Ceramic Workshops. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Hegmon, M., and W.R. Trevathan. 1996. Gender, anatomical knowledge, and pottery production: implications of an anatomically unusual birth depicted on Mimbres pottery from Southwestern New Mexico. American Antiquity 61(4): 747-54.

Holden, C. 1997. Fingering ancient Greek potters. Science 275(5305): 1425. Hruby, J. 2006. Feasting and Ceramics: A View from the Palace of Nestor at

Pylas. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio.

--. 2007. Appendix C. The fingerprints on pottery. In G. Walberg (ed.), Midea: The Megaron Complex and Shrine Area, 481-82. Philadelphia, PA: INSTAP Academic Press.

Jagerbrand, M., C. Lindholm and K.-E. Sjoquist. 2006. Fingeravtryck pa gropkeramik fran Siretorp i Blekinge och Gullrum pa Gotland. Fornvannen 101: 9-17.

Kamali, M.S. 1984. Mean epidermal ridge breadth among the 12 Iranian endogamous groups. Indian Journal of Physical Anthropology and Human Genetics 10(3-4): 150-54.

Kamp, K.A., N. Timmerman, G. Lind, J. Graybill and I. Natowsky. 1999. Discovering childhood: using fingerprints to find children in the archaeological record. American Antiquity 64(2): 309-15.

Kopaka, K. 1997. 'Women's arts-men's crafts'? Towards a framework for approaching gender skills in the prehistoric Aegean. In R. Laffineur and P.P.

104 Julie Hruby

Betancourt (eds.), TEXNH: Craftsmen, Craftswomen and Craftsmanship in the Aegean Bronze Age. Aegaeum 16: 521-31. Liege: Universite de Liege.

Kralik, M., and V. Novotny. 2003. Epidermal ridge breadth: an indicator of age and sex in paleodermatoglyphics. Variability and Evolution 11: 5-30.

Kralik, M., V. Novotny and M. Oliva. 2002. Fingerprint on the venus of Dolnf Vestonice. Anthropologie (Brno) 40(2): 107-13.

Kramer, C. 1985. Ceramic ethnoarchaeology. American Review of Anthropology 14: 77-102.

London, G.A. 1987. Cypriote potters: past and present. Report of the Department of Antiquities Cyprus: 319-22.

---. 2002. Women potters and craft specialization in a pre-market Cypriot economy. In D. Bolger and N. Serwint (eds.), Engendering Aphrodite: women and society in ancient Cyprus, 265-80. Boston, MA: American Schools of Oriental Research.

Marshall, Y. 1985. Who made the Lapita pots? A case study in gender archaeology. Journal of the Polynesian Society 94(3): 205-34.

Mills, B. 1995. Gender and the reorganization of historic Zuni craft production: implications for archaeological interpretation. Journal of Anthropological Research 51(2): 149-72.

Murdock, G.P., and C. Provost. 1973. Factors in the division of labour by sex: a cross-cultural analysis. Ethnology 12(2): 203-25.

Nixon, L. 1999. Women, children, and weaving. In P.P. Betancourt, V. Karageorghis, R. Laffineur and W.-D. Niemeier (eds.), Meletemata: Studies in Aegean Archaeology Presented to Malcolm H. Wiener as He Enters His 65th Year. Aegaeum 20: 561-67. Liege: Universite de Liege.

Nordquist, G. 1995. Who made the pots?Yroduction in Middle Helladic society. In R. Laffineur and W.-D. Niemeier (eds.), Politeia: Society and State in the Aegean Bronze Age. Aegaeum 12: 201-207. Liege: Universite de Liege.

Nosch, M.-L. 2003. The women at work in the Linear B tablets. In L.L. Loven and Agneta Stromberg (eds.), Gender, Cult, and Culture in the Ancient World from Mycenae to Byzantium. Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology 166: 12-26. Gothenburg: Paul Astrom's Forlag.

Ohler, E.A., and H. Cummins. 1942. Sexual differences in breadths of epidermal ridges on finger tips and palms. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 29: 341-62.

Papadopoulos, J.K. 1997. Innovations, imitations, and ceramic style: modes of production and modes of dissemination. In R. Laffineur and P.P. Betancourt (eds.), TEXNH: Craftsmen, Craftswomen and Craftsmanship in the Aegean Bronze Age. Aegaeum 16: 449-62. Liege: Universite de Liege.

Penrose, L.S. 1968. Memorandum on dermatoglyphic nomenclature. Birth Defects Original Article Series 4: 1-13.

Roehling, A., K. Hoffman, M. Geil, M. Stucker, P. Altmeyer, S. Kyeck and U. Memmel. 2001. Interpapillary lines-the variable part of the human fingerprint. Journal of Forensic Sciences 46(4): 857-61.

Sarsby, ]. 1988. Missuses and Mouldrunners: An Oral History of Woman PotteryWorkers at Work and at Home. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Shapiro, S.S., and M.B. Wilk. 1965. An analysis of variance tests for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 52: 591-611.

Sjoquist, K.-E., and P. Astrom. 1985. Pylas: Palmprints and Palmleaves. Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology.and Literature Pocket-Books 31. Gothenburg: Paul Astrom's Forlag.

Stucker, M., M. Geil, S. Kyeck, K. Hoffman, A. Roehling, U. Memmel and P. Altmeyer. 2001. Interpapillary lines-the variable part of the human fingerprint. Journal of Forensic Sciences 46: 857-61.

Ke-ra-me-u or Ke-ra-me-ja? 105

Vitelli, K. 1978. Thoughts on prehistoric potters and ceramic change. Temple University Aegean Symposium 3: 43-46.

Walz, C. 1985. Ethnographic analogy and the gender of potters in the Late Cypriot Bronze Age. Report of the Department of Antiquities Cyprus: 126-32.

Wright, R.P. 1991. Women's labour and pottery production. In J.M. Gero and M.W. Conkey (eds.), Engendering Archaeology: Women and Prehistory, 194-223. Oxford: Blackwell.

Zimmerman, D.W. 1987. Comparative power of Student T test and Mann-Whitney U test for unequal sample sizes and variances. Journal of Experimental Education 55(3): 171-74.