Jean Delville's 'La Méduse' (1893)

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

5 -

download

0

Transcript of Jean Delville's 'La Méduse' (1893)

J e a n D e l v i l l e“La MeDuse” (1893)

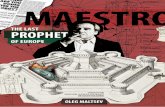

Jean Delville (1867-1953), La Méduse, 1893. Ink, blue pencil, pastel, watercolour and paint on paper, 355 x 150 mm, signed and dated below left. Provenance: eugène de Keyn, Brusells, 1905, Robert de Keyn, Bruselles, sothe-

by’s, London, 22 novembre 1983, lot 84. Collection privée.

PatRICK DeRoM GaLLeRyBRusseLs – New yoRK

Rue aux Laines 11000 Brussels, Belgium

tel +32 2 514 08 82; Fax +32 2 514 11 58e-mail address : [email protected]

http://www.patrickderomgallery.com

58 east 79th street - New york, Ny 10075 tel: 212-861-4050 - Fax: 212-772-1314

J e a n D e lv i l l e ’ s “ l a M e D u s e ” ( 1 8 9 3 )

B r e n d a n C o l [email protected]

Jean Delville was one of the most gift-ed artists of his generation. Born in 1867,

he was the leading figure amongst a young cohort of avant-garde painters and intellec-tually creative individuals whose innovative work defined the spiritual concerns of the fin-de-siècle. His inscrutable La Méduse (1893) is a skilfully executed invention – a disturb-ing sphinx-like creation that is an outstanding example of contemporary anti-realist tenden-cies that valued the imagination and ideas as the primary source of artistic expression.

This exceptional work is an unique re-interpretation of the theme of the frightful Gorgon of antiquity, whose glare petrifies all those who look upon her. she also embod-ies the archetypal, but complex, emblem of the fatal feminine, popular in contemporary symbolist art. His treatment of the theme, however, is highly original. On the one hand he resorts to key iconographic elements de-rived from the traditional myth – notably the head of serpents – but then he also introduces features and motifs that are entirely original: such as the poppies, the feeding-saucers and the motif of the veil. This results in a power-fully evocative work whose narrative is equiv-ocal and mysterious, and not easy to interpret in a strictly reductive way. This attribute is a notable feature of symbolist art generally, which is defined by its suggestive, allusive and ambiguous expressive tropes that invoke an

order of reality lying beyond the surface ap-pearances of the sensual world.

La Méduse is a key example of Delville’s so-phisticated and expert draftsmanship. His re-fined linear technique and subtle modulation of form seen here is evidence of his disciplined academic training. He enrolled at an early age in the Belgian academy of Fine art and dis-played, from the very beginning, a prodigious artistic skill, winning many of the prestigious prizes for drawing while still very young. His adherence to the spirit of the Classical tradi-tion in art remained with him throughout his life, but he continually updated this tradition, reinventing its principles in line with the vi-brant new tendencies in art during the 1890s, as is clearly evident in La Méduse. However, he used his classical technique principally as a vehicle to express more vividly his intellectual and artistic ideas, which were based on a be-lief that the transcendental world should be the goal of artistic expression. in other words, the emphasis on a disciplined linear tech-nique employed here is deliberate and reflects Delville’s deeply felt belief that spiritual val-ues are more clearly articulated through line. in this regard he was profoundly influenced by Quattrocento artists whose linear tech-niques he emulated – at times quite literally – as seen in his tempera masterpiece L’Amour des âmes of 1900 (Musée d’ixelles, Brussels).

patriCk DerOM Gallery 3

in an article published a few years after La Méduse was done, he expressed a clearly mys-tical formulation in his approach to line : ‘l’art a commencé par le Dessin, par le ligne et la ligne, c’est l’âme de l’equilibre, c’est l’es-sence même de la plastique. ... le dessin est la partie la plus élevée, la seul indépendante de la technie picturale et où le génie seul peut se

montrer…’ What Delville is suggesting here is that an intimate relationship exists between line and form and the expression of the ide-al in art. in other words, line is an analogic expression of the union of the material and the spiritual, of nature and the absolute: ‘... la ligne, dans les choses de la nature, c’est la signature de Dieu. la ligne, ne l’oublions

� Jean Delville - la MeDuse

jamais, est l’expression symbolique des affini-tés primordiales qui existent entre l’esprit et la Matière. la ligne, ou la Forme, est le mys-tère du monde physique, le mystère de l’art, le mystère de la Beauté.’1

He places the Medusa in a highly simplified and largely indeterminate setting dominated by a menacing reddish-orange, almost apoca-lyptic, glow. This colour creates a lively tension in the work as it contrasts with the green-blue of the serpents and the blue of the veil that partly conceals the figure of the Medusa. This colour also vaguely suggests the colour of blood – hinting towards the violent murder of the Gorgon described in Classical sources. The composition of this work is narrow and cropped, and he places the figure right up against the picture plane, truncated at the top

and bottom. This not only focuses our atten-tion strongly on the enigmatic and mysterious face of the Medusa, but also contributes to a tense, disquieting and claustrophobic atmos-phere in the drawing as a whole. The Medusa’s delicately articulated, broad face, moreover, is expressionless apart from the very slightest hint of an enigmatic, almost seductive, smile. The lower part of her face is lit up while the remaining areas around her eyes are in dark-ness. This sets off her glowing, pale blue eyes that stare upwards behind the veil, suggest-ing that she is in a trance. The veil softens her facial features which are articulated in a subtle sfumato, concealing, furthermore, the details of her neck and torso. This gives the impression that the head is disembodied – a hint perhaps of her future fate. it is, however, worth noting that her facial features are those

patriCk DerOM Gallery �

of a contemporary woman, and Delville has in no way tried to idealise her or to create a derivative from classical forms. This gives the image a presence and immediacy and forces one to confront her as a figure who belongs to contemporary reality, and not of the past. in other words she lacks any mediating guise derived from the classical tradition or the antique. Contemporary viewers would there-fore have seen her as someone belonging to their world, which would surely have resulted in a disquieting, if thrilling, response.

Delville’s emphasis on the face and head is in fact a typical feature of many of his works as a whole. The head as a subject on its own is an ubiquitous subject of many of Delville’s paintings, especially during the 1890s, wheth-er as a subject of conventional representation such as his many mysterious portraits in blue

(the so-called bleuâtres; particularly his Tête de femme de profil of 189�) or represented in a more iconic mode as seen especially in his Mysteriosa (Portrait of Madame Stuart Mer-rill, 1892) and Parsifal (1890). One of the dominant themes in Delville’s paintings is the severed head, and most striking of these is his Orphée mort (1893) and La fin d’un règne (1893). The theme of the severed head was a key motif in non-realist iconography and pre-dominates in representations of the theme of salome2 and Orpheus.3

This emphasis on the head can be traced to Delville’s hermetic writings where the head is seen to be the seat of the soul. For Delville, the soul animates thought itself through the brain.� The seat of the brain, the head, has for Delville a particular significance: ‘la tête humaine est construite selon les rythmes des

6 Jean Delville - la MeDuse

lois planétaires; elle est attractive et rayon-nante, et c’est sur elle que l’influence astrale, d’ailleurs, se manifeste absolument. il n’y a pas de différence entre les réseaux des attrac-tions planétaires et les rayonnements des tis-sus nerveux.’� This probably explains why he often includes a radiant light around the head of his figures of hero-initiates and also why the illumination of the face is emphasised in most of his works.

Delville reduces his narrative to a few essential motifs concentrating on the veiled Medusa with her dense mass of serpentine hair; her hands holding bowls of fluid consumed by the serpents; and then surrounding her, four seem-ingly burnt-out poppy pods. The Medusa ele-vates the two saucers on either side of her head and they contain an azure blood-like liquid towards which the frenzied mass of serpents swarm – their mouths open as they greedily, energetically, and almost violently, consume the eerie fluid which slops menacingly over the edges of the saucers. The serpents appear to glow, ghost-like, in a green-blue haze. Their bodies are entwined and knotted in a com-plex writhing mass, which is a bravura dem-onstration of his inventive imagination and astonishing technical skill. in fact, the render-ing of these serpents results in a finely articu-

lated artistic passage that is highly memorable amongst his works of this period. This seeth-ing kinetic clot of serpents contrasts strongly with the static and unreactive face of the Gor-gon. This contrast is further enhanced in the way she impassively nurtures her vampirish creatures that, in the original myth, replaced her beautiful locks of hair.

The group of four black poppy pods that surround the Medusa is enigmatic. two are placed symmetrically on either side of her, from which dark fume-like tendrils emanate like some funereal incense staining the mor-bid air surrounding the figure. This motif further enhances the stifling and claustro-phobic atmosphere of this image. interest-ingly, the trailing smoke from the poppies, as well as the poppy pods themselves, are treated in a linear, decorative manner – as a series of parallel meandering contour lines that echo the curvilinear interlaced serpents. it is worth noting how this stylised treatment of the smoke drifting from the poppy pods contrasts distinctly with the finely rendered figural treatment of the Medusa herself. This combination of decorative abstraction and naturalistic representation reinforces the ideographic fiction of the drawing and the subject it portrays. This decorative linear el-ement is, moreover, a significant formal fea-

patriCk DerOM Gallery 7

ture, often seen in the woodcuts of toorop, which prefigures the stylistic conventions of art nouveau. One is, finally, reminded of the fact that these flowers are not commonly as-sociated with the Medusa theme in classical sources, but are, however, commonly linked to sleep and intoxication. This could suggest that the Medusa is performing some kind of trance-induced, chthonic ritual – as though she were some sort of sorceress.

The balance of heightened, dramatic energy in the articulation of the serpents and the passive, controlled expression of the Medusa creates an unsettling tension in Delville’s drawing. Compositionally, how-ever, he manages to achieve a sense of balance through the relationship between the narrow horizontal format of the work and the rigidly symmetrical placing, around the centrally po-sitioned head, of the vertical pillar-like arms carrying the two saucers. The placing of the poppy pods on either side further enhances this symmetry and the concomitant sense of regularity and balance seen elsewhere. More-over the vertical thrust of the arms and veil are offset by the horizontal undulating (and chaotic) mass of serpents and the meandering fumes emerging from the poppies – especially the two lugubrious plumes cutting across the figure in the foreground – all of which en-hance the sense of movement and repose that sustains the underlying logic of this image. it might be worth noting that an absolute symmetry is avoided in the difference in the number of smoke plumes on the left and right hand side: offset by six on the left and five on the right.

in this regard one ought also to comment very briefly on the obvious number symbol-ism implicit in these poppy pods depicted in this work. Three smoky streams emanate from three of the pods, while from the fourth – to the extreme right – only two emerge. added together there are, in other words, ten smoke streams. This configuration therefore results

in the representation of the numbers two, three, four, nine and ten. Delville stated ex-plicitly throughout his writings that number plays a significant role in artistic expression, and his interest in the occult would have drawn him to the works of contemporaries who wrote extensively on the significance of number symbolism such as Gerard encausse (better knows as papus), whose writings such as Traité élémentaire de Science Occulte, Traité Méthodique de Magie Pratique and La Science des Nombres, deals exhaustively with this as-pect of the hermetic world view to which Delville subscribed. The significance of the numbers represented in La Méduse are dealt with extensively in the writings of papus.

Delville left very few written accounts of his art which leaves one with few definitive start-ing points when attempting to interpret his drawing and paintings. This is ironic – given that he was a prodigious author of many books, articles, and essays on art; but perhaps this was also deliberate as it forces one to con-front his paintings in an unmediated way in order to recreate their meaning as one would a symbol. nonetheless, it is worth noting that the theme of the Medusa was very popular amongst his contemporaries. However, it should be emphasised that this drawing is one of the earliest expressions of this motif in symbolist art – khnopff ’s more iconic Blood of the Medusa, would follow much later in 1898, and his allusive sleeping Medusa in 1909. precursors to Delville’s work include arnold Boecklin’s late-romantic interpreta-tion of the theme evident in his Medusa of 1878 – depicting a face that is resigned and dying, an effect enhanced by the flaccid ser-pents sagging around her. But Delville’s in-terpretation of the theme does not focus on the more canonical episode of the decapita-tion of Medusa and the use of the head by perseus as a weapon. a dramatic early exam-ple of this kind expressing the anguish of the

8 Jean Delville - la MeDuse

Gorgon is evident in Caravaggio’s Medusa (1�97, uffizzi) and rubens’s Head of Medusa (161�, kunsthistorisches Museum, vienna). The writhing mass of snakes in the former share the same energy and dynamism seen in Delville’s image. a variation of this theme is also evident in Burne-Jones’s The Baleful Head (1886-7, staatsgalerie stuttgart) with which Delville was most probably familiar, given his enthusiasm for Burne-Jones and other pre-raphaelites. But the suffering of the Medusa is absent in Delville’s treatment of the theme. she is passive, in control and, in fact, a nurturing figure; an image that is far removed from the gruesome, bleeding and disembodied head commonly found in artis-tic images representing this Gorgon.

The great achievement of this work lies in the fact that he creates an allusive and ambiguous motif existing in its own iconographic and pic-torial reality – an autonomous visual emblem not uncommon to symbolist art. The ambi-guity of his Medusa lies in the fact that she is at once gentle and nurturing, but at the same time expressing an understated and subtle cruelty and malevolence. The sense of menace in this work is implicit in the eerily luminous eyes gleaming through the surrounding dark-ness. it gives her a surreal and inhuman char-acter, as if she were a creature of prey whose eyes glow in the dark, or some vampirish fig-ure of the dead. The effect is mesmerising and haunting and reinforces her chilling allure. Delville actually repeats this motif from his earlier evocation of a lubricious, malevolent and ambivalent fatal female seen in his Idole de la Perversité of 1891, which shares many features seen in La Méduse – including an au-reole of luminous serpents and the fact that she wears a veil. When conjuring this motif Delville might have had in mind a passage from Baudelaire’s Fleurs du Mal, especially the lines from ‘l’irrémédiable’ describing the descent of the damned soul into darkness

while surrounded by ‘des monstres visqueux/ Dont les larges yeux de phosphore/ Font une nuit plus noire encore’.

The eyes are turned upwards, highly remi-niscent of his treatment of the head in Mad-ame Stuart Merrill – Mysteriosa (Musées des Beaux-arts, Brussels), which he created the previous year in 1892. This motif is also in-cluded in the expression of the young boy in his Ange des Splendeurs (189�, Musées des Beaux-arts, Brussels). This trance-like attitude is significant and suggests that the Medusa is a more ambivalent figure than one initially suspects. a reference to this ex-pression can be sourced in the writings of eliphas lévi, whose works were influential in Delville’s occult circle of writers and po-ets with whom he was closely associated. in a cogent passage from his Histoire de la Magie, eliphas lévi described exactly this ecstatic visionary attitude, with its rolled-back eyes, as a condition induced through a concentra-tion of astral light – and it would be entirely relevant to read this motif in La Méduse in exactly this sense; suggesting that Delville’s sphinx-like Medusa is experiencing an hal-lucinatory episode – a moment of introspec-tive, perhaps even visionary – clairvoyance: ‘Quand le cerveau se congestionne ou se surcharge de lumière astrale, il se produit un phénomène particulier. les yeux, au lieu de voir en dehors, voient en dedans; la nuit se fait à l’extérieur dans le monde réel et la clarté fantastique rayonne seule dans le monde des rêves. l’œil alors semble retourné et souvent, en effet, il se convulse légèrement et semble rentrer en tournant sous la paupière. … là est la source de toutes les apparitions, de toutes les visions extraordinaires et de tous les phé-nomènes intuitifs qui sont propres à la folie ou à l’extase.’6 in this regard, this motif sug-gests that his Medusa is a figure that alludes to the world of the occult and the transforma-tive magical practises associated with that tra-dition with which Delville was familiar. like

patriCk DerOM Gallery 9

Mme Merrill – with her iconic hermetic book – this Medusa is more of a clairvoyant sorcer-ess of the Mysteries, rather than a malevolent monster derived directly from classical my-thology. Delville’s Medusa is, in other words, a highly textured symbol relating to contem-porary ideas, and less a literal representation derived from classical sources.

This hermetic aspect of La Méduse is further reinforced by the addition of a non-canonical veil draped in front of her. The veil motif is used extensively during the period. The con-notations of the veil are numerous and one is immediately reminded of the veils of salome – temptress supreme – a figure, as Huysmans put it, ‘with a haunting fascination for artists and poets’ of the fin-de-siècle.7 The theme of salome was represented obsessively dur-ing the period, notably in aubrey Beardsley’s The Dancer’s Reward (189�) and Franz von stuck’s Salome (1906). Other typical exam-ples include Félicien rops’ Modernité – a contemporary transformation of the theme, and lucien levy-Dhurmer’s Salome Kiss-ing the head of John the Baptist (1896). The veil, however, also suggests the notion of the Bride. There are several notable examples of the theme of the Bride during the fin de siè-cle. significantly most of these are contem-porary with Delville’s Medusa, for example: Jan Thorn prikker’s The Bride (1893), Jan toorop’s The Three Brides (1893), or works created later such as alfred kubin’s The Bride of Death (1900). But the image of a woman concealed behind a veil was, of course, already present in the work of Delville’s compatriot, Fernand khnopff, notably his funereal The Veil (c. 1890), which might have been a start-ing point for this motif in Delville’s drawing.8 Delville used, however, this motif of the veil in his earlier Idole de la perversité , which in this case is spotted.

The sense of mystery conjured by the veil was extensively exploited during the era and

is emblematic of the notion of concealment, of arcane or mystical secrets revealed to initi-ates in the hermetic and esoteric tradition. it is often associated with the tradition of a myste-rious figure that is the source of higher knowl-edge, found especially in romantic poetry in the figure of the inspirational muse, for exam-ple, in the novellas of the German romantic author novalis and especially his The Pupil of Saïs and Heinrich of Ofterdinge. in the context of the occult tradition, the veil also suggests the figure of isis whose veil conceals the mys-teries of esoteric wisdom and initiation, ‘the thick veil which conceals the invisible wonders from the eyes of men’.9 plutarch records an in-scription at the shrine of isis at sais, frequent-ly quoted in esoteric literature, which states: ‘i am all that hath been, and is, and shall be; and my veil no mortal has hitherto raised.’10 The veil of mystery was an important image in Theosophical writings. Blavatsky refers to this in the title of her first theosophical work Isis Unveiled. A Master Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Theology. lifting the veil was frequently referred to by theosophists (Delville became an ardent Theosophist) as a metaphor for revealing the mystery of the se-cret doctrine of occultism or the attainment of spiritual enlightenment, or initiation.11

The image of isis is a central symbol in my-thology and esoteric thought representing the principle of the ‘eternal Feminine’. she commands the cycles of birth and death in her role as goddess of nature, not only the cycles of physical birth and death but the symbolic birth and death experienced in the ancient rites of initiation. The analogy between death and the awakening to occult knowledge, signified through ‘lifting the veil’, is clearly suggested in de nerval’s incantation to isis: ‘O nature! ô mère éternelle! était-ce là vraiment le sort réservé au dernier de tes fils célestes? les mortels en sont-ils venus à repousser toute espérance et tout prestige, et,

10 Jean Delville - la MeDuse

levant ton voile sacré, déesse de saïs! le plus hardi de tes adeptes s’est-il donc trouvé face à face avec l’image de la Mort?’ 12

The significance of the image of isis, as the embodiment of the esoteric power, would have been familiar to the artists of the fin de siècle from various obvious sources, most no-tably in the writings of edouard schuré’s (a friend of Delville), and particularly his The Great Initiates. schuré explains that isis has three different meanings: ‘literally she per-sonifies Woman, and from this the universal feminine gender. Comparatively, she personi-fies the fullness of terrestrial nature, with all its reproductive powers. in the superlative, she symbolises celestial and invisible nature, itself the element of souls and spirits, spiritual light, intelligible in itself, which initiation alone confers.’13 villiers de l’isle-adam, with whom Delville was acquainted, invoked the egyp-tian goddess in his occult novel Isis of 1862 as the protagonist, the enigmatic tullia Fab-riana, meditates on the enigma of the sphinx:

Sphinx !... ô toi, le plus ancien des dieux! ... murmura la belle vierge prométhéenne, je sais que ton royaume est semblable à des steppes arides et qu’il faut longtemps marcher dans le désert pour arriver jusqu’à toi. L’ardente abstraction ne saurait m’effrayer ; j’essaierai. Les prêtres, dans les temples d’Egypte, plaçaient, auprès de ton image, la statue voilée d’Isis, la figure de la Création; sur le socle, ils avaient inscrit ces paroles: « Je suis ce qui est, ce qui fut, ce qui sera: personne n’a soulevé le voile qui me couvre.» Sous la transparence du voile, dont les couleurs éclatantes suffisaient aux yeux de la foule, les initiés pouvaient seuls pressentir la forme de l’énigme de pierre, et, par intervalles, ils le surchargeaient encore de plis diaprés et mystérieux pour mettre de plus en plus le regard des hommes dans l’impuissance de la profaner. Mais les siècles ont passé sur le voile tombé en poussière ; je franchirai l’enceinte sacrée et j’essaierai de regarder le problème fixement.14

it would not be too far fetched to suppose the Delville’s Medusa embodies qualities of the sphinx as well – an iconic symbol of the period and that she therefore embodies the qualities of an initiatory figure, which popu-lated his art generally. although he never created literal representations of sphinxes (apart from his poster designs for the Salons d’Art Idéaliste), many of his female creations express implicitly qualities commonly associ-ated with the sphinx; i.e., the mysterious fem-inine with her air of mystery and wisdom as well as her ambiguous relationship between the material and transcendental orders of reality. Delville invoked these aspects of this motif in his poem ‘sphinge Blanche’ from his anthology Les Horizon Hantés:

En son profil sacre d’archange hiératiqueravi dans sa mysticité d’un marbre divin,comme un lys transparait l’idéal fémininqui séraphise son blanc visage extatiqueL’infini de ses yeux s’illumine aux splendeurssereines, flammes de l’azur élégiaque,et, vierge immaculée et paradisiaquevestalement rêve son âme d’albes candeursSphinge, sa lèvre énigmatique reniele verbe impur et profane de la vie- et nul songe humain n’a hante son front astralce saint front d’idole, ce pur front d’éliteen la spiritualité duquel palpitela suprême ferveur d’un culte sidéral.

There are some notable passages in this poem which describe very well the enigmatic figure in Delville’s La Méduse; especially the descrip-tion of ‘l’infini de ses yeux’, their ‘flammes de l’azur élégiaque’ her ‘lèvres énigmatique’ and the hieratic nature of this astral ‘idéal féminin’ with her ‘profil sacre’ and ‘visage extatique’.

Delville has created in his La Méduse an im-age that is allusive and complex. she feeds her frenzied brood of serpents in a trance-like demeanour, which is mesmerising – combin-

patriCk DerOM Gallery 11

ing a sense of horror and beauty at the same time. The work tantalises with its reference to the classical source of the fatal Gorgon, but in adding motifs that do not belong to the origi-nal source he reworks the narrative, updating it, and giving it a contemporary gloss. she is a creature of mystery, familiar yet at the same time unknown, resulting in a classic rework-ing of the theme of the archetypal feminine. she is a synthesis of sphinx, sorceress and mythic monster combined to create a power-ful evocation of the eternal feminine.

This work also expresses vividly key as-pects of his aesthetic that he was developing at this early stage of his career, particularly his tendency to synthesise the traditional and the modern, using an expert technique to articu-late his imagination in order to accomplish this. His development of the importance of line, derived from the Classical tradition and used here with such brilliance, is a key for-mal element of his style to which he adhered throughout his career.

in the spirit of the renaissance invenzi-one, he has bodied forth the forms of things unknown, bringing to life this creature of his imagination in a work of art that is startlingly persuasive. idea, form and technique are per-fectly balanced in this drawing to achieve a faultless and compelling realisation of his idealist aesthetic. it is well to remember that Delville’s artistic goal was to initiate a school of painting that would pursue a form of her-metic idealism. in other words, an aesthetic that is fundamentally intellectual in approach and concerned with spiritual ideas that are ex-pressed through ideal forms and articulated in a polished classical-idealist technique. He formulated his aesthetic as a threefold system bringing together his notions of la Beauté spi-rituelle (idea), la Beauté plastique (form) and la Beauté technique (execution). This triple schema – with its emphasis on the expres-sion of ideal Beauty through the perfection of idea, form and technique – he termed l’Es-

thétique Idéaliste. He never wavered from this goal, and La Méduse is an impressive realiza-tion of its core principles.

enDnOtes1 Delville, ‘le Discours de Jean Delville prononcé à sa récep-

tion dans la salle de l’académie comme lauréat du prix de rome.’ La Ligue Artistique. no. 22, november 189�, p. �.

2 see also Moreau’s The Apparition 1876, Franz von stuck’s Salome (1906), lucien lévy-Dhurmer’s Salome embracing the severed head of John the Baptist (1896), and Odilon redon’s Head of a Martyr (n.d) are notable examples.

3 Vide Maria luisa Frongia. Il Mito di Orfeo nella pittura simbolista francese. università Degli studi di Cagliari. estratto de annali delle Facoltà di lettere-Filosofia e Magistero. vol. XXXvi 1973. Gallizzi-sassari 197�.

� Vide. Delville, Dialogue entre Nous. Argumentation Kab-balistique, Occultiste, Idéaliste, Bruges, Daveluy Frères, 189�, pp. 11-1�, 16.

� Delville, Dialogue entre Nous. Ibid., p. 17.6 eliphas lévi, Histoire de la Magie. Avec une Exposition

Glaire et Précise de ses Procèdes, de ses Rites et de ses Mystères. paris : Germer Bailliére, libraire-Éditeur, 1860, pp. 20-21.

7 Huysmans, Against Nature. a new translation by robert Baldick, penguin Modern Classics, penguin, Great Brit-ain, 19�9, p. 6�.

8 Other notable examples by khnopff include: Tête d’une femme (1898), Un Voile bleu (c. 1909) and Un Rideau bleu (1909).

9 edouard schuré. The Great Initiates, san Francisco: Harper and row, 1961

10 plutarch, De Iside, 9, 3��C. a hymn addressed to isis-net expresses this idea of the Veil Of Nature which hides the mystery of truth from human eyes:

Hail, mother great, not hath been uncovered thy birth! Hail goddess great, within the underworld which is doubly hidden thou unknown one! Hail thou divine one great, not hath been unloosed! O unloose thy garment [veil]. Hail [Hidden One], not is given by way of entrance to her... e. a. Wallis Budge, The Gods of the Egyptians, volume i,

london, 190�, p. ��9, cited in M esther Harding, Wom-an’s Mysteries, Ancient and Modern, shambhala, Boston and shaftesbury, 1990, p. 182.

11 The inscription is quoted by G r s Mead in ‘Theosophy and Occultism’ published Lucifer: A Theosophical Maga-zine, eds. Helena petrova Blavatsky and annie Wood Besant, september 1891 to February 1892, p. 112.

12 Gérard de nerval, Isis. in, Nerval le rêve et la vie, Hachet-te, paris, 19��, p. 166.

13 schuré, The Great Initiates, p. 191-192.1� auguste villiers de l’isle-adam, Isis. paris: librairie

internationale, 1862, pp. 131-132. This mystery of the veil is vividly articulated in a late work by khnopff, The Blue Veil, (1909).

Patrick Derom Gallerypaintings, drawings and sculpture from the 19th and 20th c.

teFaF Maastricht 2010, stand n° 71�

rue aux laines 11000 Brussels

Belgiumt + 32 2 �1� 08 82F + 32 2 �1� 11 �8

e-mail address : [email protected] : http://www.patrickderomgallery.com

patrick Derom Gallery opened at the petit sablon in Brussels in 1986. since then it has grown into a gallery offering mainly european art from 1880 till 1980, and specialises in symbolism, surrealism and modern classics. exhibitions (including James ensor - 199�, George Minne - 199�, victor servranckx - 1997, Gustav klimt - 2007, pol Bury - 2007 and 2009 a.o.) have al-ternated with participation in a variety of international art fairs including the salon du Dessin in paris, The international Fine art Fair in new york, the Basel art Fair and the Biennale des antiquaires in paris (Carrousel du louvre). after years of informal collaboration with shepherd Gallery in new york, shepherd & Derom Galleries opened at no. �8 east 79th street in October 1998. The gallery is on the upper-east side, between Madison and park avenue, a stone’s throw from the Metropolitan and Gug-genheim Museums.