irA;: 1&;8; fa!alr-all:gl"! C:Q1t11fiscafedl tall!dl~

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

6 -

download

0

Transcript of irA;: 1&;8; fa!alr-all:gl"! C:Q1t11fiscafedl tall!dl~

I '11...)8' .... }I,I.~' ' .•• :.:1;1 ... ::.,. ... : ", ... :J!; ... ;.! ]ift:e:~\~a\ .;ift) 1111~ ".J Q UI~I ulr . /c:a, .... IJ.j"~· .. ,.~}

1!i rf \ 1a""" ft .. tit ,8:11.' i .r . IV'IIIill

irA;: 1&;8; fa!alr-all:gl"! C:Q1t11fiscafedl tall!dl~

Volume 1: Report

Evelvn Stokes 1997

U · The • mverSlty ofWaikato Te Whare Wananga

~o~~~~ 0 Waikato

The Allocation of Reserves for Maori

in the Tauranga Confiscated Lands

Volume 1: Report

Evelyn Stokes 1997

J University of Waikato Private Bag 3105 Hamilton, New Zealand

3

Contents

Jlreface ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7

1. IntrOduCtiOIl -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 2. Legisiatioll for Native Reserves -------------------------------------------------------- 16

3. The Katikati Te JlUIla "Jlurchase" 1864 ------------------------------------------------ 25

4. Negotiatiolls 011 the Katikati Te Jlulla Block 1866 ----------------------------------- 37

5. CorrfroIltatioIl over Survey of the CoILfiscated Block 1866 ------------------------- 60

6. The "TauraILga Bush CampaigIL" 1867 ------------------------------------------------70

7. The TauraILga District LaILds Acts 1867 aILd 1868 ----------------------------------- 85

8. The Allocatioll of Reserves ill the Katikati Te JlUIla aILd CoILfiscated Blocks ---- 99

9. The Removal of RestrictioIlS 011 AlieIlatioIl of Reserves -------------------------- 127

10. The "Half-Caste Claims" -------------------------------------------------------------- 145

11. The TOWIl of TauraILga aILd TOWIlShip of GreertoIl--------------------------------- 155

12. EIldowmeIlt Reserves ullder the Native Reserves Acts ---------------------------- 167

13. Summary of Reserves Allocated by 1886 ------------------------------------------- 185

14. Summary of LaILds GraILted to Hapu ------------------------------------------------- 231

15. Some COIlc1udillg Commellts --------------------------------------------------------- 285

16. Referellces ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 296

17. Appelldices:

1. Deeds for the Katikati Te Jlulla Block ------------------------------------------- 302

2. "LaILd could be awarded omy to loyal Natives ... " ----------------------------- 316

3. "Native custom" was "wiped out by the confiscatioll of laILd" --------------- 320

4. Judgmellt 011 the oWIlership of Lot 202, SectioIll, TOWIl ofTauraILga------ 323

5. OpiILiOIlS 011 the vestillg of Lot 210, Jlarish of Te JluIla, ill Jlelle Taka ------- 343

4

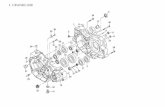

List of Figures ( 1. Tauranga Confiscated Lands ------------------------------------------------------------- 8

2. Tauranga Moana -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10

3. Mackay's Panui 1866 -------------------------------------------------------------------- 42

4. Mackay's Sketch Plan 1867 ------------------------------------------------------------- 44

5. Plan on the Tawera Purchase Deed ---------------------------------------------------- 46

6. Plan of the "Ngaiterangi" Purchase Deed --------------------------------------------- 49

7. Reserves for "Ngaiterangi" on Deed No. 461 ---------------------------------------- 51

8. Plan of the "Pirirakau" Purchase Deed ------------------------------------------------ 53

9. Boundaries of the Katikati Te Puna "Purchase" -------------------------------------- 55

10. Hapu in the Confiscated Block --------------------------------------------------------- 61

11. Clarke's Sketch Map 1867 -------------------------------------------------------------- 78

12. Investigation of Titles of "Land Returned" ------------------------------------------- 88

13. Index Map of Tauranga Confiscated Lands ----------------------------------------- 100

14. Military Settlement and Native Reserves 1868 ------------------------------------- 102

15. Removal of Restrictions on Alienation ---------------------------------------------- 132

16. Tenure of the "Lands Returned" 1886 ----------------------------------------------- 143

17. The Town of Tauranga and Township of Greerton --------------------------------- 156 / ('\',

'\. ,I

18. a and b. Reserves in the Town of Tauranga ----------------------------------- 160- 161

19. Reserves in the Township of Greerton ----------------------------------------------- 162

20. Plan of the "Native Hostelry" Site --------------------------------------------------- 170

21. a, b, c and d. Plans of Native Reserves, Town of Tauranga -----------------171-174

22. Plan of the "Brookfield Reserve" ---------------------------------------------------- 175

23. Reserves Allocated by 1886: Confiscated Block ---------------------------------- 186

24. Mackay's Plan of Reserves Nov. 1866 ---------------------------------------------- 187

25. Te Puna Reserves ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 189

26. Reserves at Otumoetai, Bethlehem and Greerton ---------------------------------- 191

27. Reserves Allocated by 1886: Katikati Te Puna Block ---------------------------- 195

28. "Lands Returned": The Inland Blocks ---------------------------------------------- 199

29. "Lands Returned": East of Tauranga Harbour and Waimapu River------------- 200

30. "Lands Returned": Matakana and Rangiwaea ------------------------------------- 201

31. Relief ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 203

32. Soils -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 204

('

5

33. Vegetation c .1860 ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 205

34. Smith's Sketch Map and "Census" 1864 -------------------------------------------- 209

35. Kainga in 1864 -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 212

36. Maori Population 1881 ---------------------------------------------------------------- 216

37. Matakana and Rangiwaea ------------------------------------------------------------- 225

38. Nga Marae 0 Tauranga Moana-------------------------------------------------------- 233

39. Hapu East of Tauranga Harbour and Waimapu River -----------------------,..,.---- 240

AO. Huria: Lot 452 Parish ofTe Papa 1925 ------~-------------------------------------- 249

41. Hapu of the Wairoa Valley ------------------------------------------------------------ 255

42. The Omokoroa Reserves -------------------------------------------------------------- 268

43. "Unproductive Native Land" 1906 --------------------------------------------------- 291

44. Lands Reported on by Stout-Ngata Commission 1908 ---------------------------- 293

45. Maori Land 1930-1950 ---------------------------------------------------------------- 295

6

Te Papa viewed from Monmouth Redoubt in foreground to the CMSmission station and Mauao c.1870

Photo: Tauranga District Museum

c

i{

7

Preface

This report has been compiled at the request of the Chairperson of the Waitangi Tribunal, Chief Judge E.T. Durie. Before I was appointed as a member of the Tribunal, I had been commissioned to produce an overview report of Maori grievances in the Tauranga confiscated lands (Stokes 1990 and 1992). Since then a good deal more research has been done both by claimants and Tribunal staff. There remained a gap which I am now asked to fill, that is to review just how much land was granted to each hapu in Tauranga Moana. For reasons which will be explained in the introduction, this was not a simple task, given the circumstances of the allocation of reserves, the status allocated to grantees by Crown officials as "friendly" , or "surrendered rebels" , or individuals who were given "compensation", or awards for "loyalty" , or "services rendered". The administration of the reserves was also complex, and covered by numerous different pieces of legislation since the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863 under which the confiscation of Tauranga lands was proclaimed in 1865.

In compiling this report I acknowledge with much appreciation the assistance provided by staff of the Maori Land Court, Hamilton, in particular the present and former Registrars (Lindsay Wilson and Maehe Maniapoto) and Jim Shepherd; staff in the Department of Survey and Land Information (now Land Information New Zealand), particularly Don Prentice (now retired) and John Neal of the Maori Land Section in the Hamilton office; Jinty Rorke of the Tauranga Public Library; and staff in the University of Waikato Library, Hamilton. I also acknowledge gratefully the work of Max Dulton, Department of Geography ,University of Waikato who drafted the maps; Danelle Dinsdale who searched titles; Donald Stokes for his computer work to produce the lists of owners in Volume 2; and Lorraine Brown-Simpson and her staff in the University Secretarial Services who typed the text.

Finally I add a disclaimer. Because of my Tauranga connections, I am disqualified from acting. as a member of the Tribunal panel that will hear the Tauranga claims. This report has been c(}mpiled at the Chairperson's request to assist that Tribunal when it is· appointed. This report 'should not in any way be construed as an expression of opinion of the Waitangi Tribunal. I remain responsible for any interpretations contained therein.

Evelyn Stokes Professor of Geography University of Waikato December 1997

8

N GAT I

H A U A

Matamata.

Peria.

* Maungakawa

• Hanga

N GAT I • Kuranui

RAUKAWA

*

7 • Tapapa

TAURANGA CONFISCATED LANDS P,!, , ~ , . , ,'p

kllamotrn$

Figure 1

Land under New Zealand Settlements Act 1863 .

~ Confiscated·Bi.ock

~ CMSTe Papa Block

KatikatiTe Puna Block

DMOliti Island

(

{

GM:):9/96

(

9

1. Introduction

The Tauranga confiscated lands (Figure 1) comprise the area estimated at 214,000 acres

defined in the Schedule to the proclamation dated 18 May 1865 which declared this area to

be a "District" within the provisions of the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863 (New Zea

land Gazette 1865, p. 187). The "Sim Commission" inquiry into confiscated lands found

that "in fact 290,000 acres" were actually confiscated in the Tauranga district (AllIR 1928,

G-7, p. 19). In effect, the 1865 proclamation extinguished Native title, or Maori customary

tenure of this land, and the whole area became, ipso facto, Crown land. The proclamation

described this area as "the lands of the tribe Ngaiterangi" and also ordered:

that in accordance with the promise made by His Excellency the governor at Tauranga, on the sixth day of August, 1864, three fourths in quantity of the said lands shall be set apart for such persons of the tribe N gaiterangi as shall be determined by the Governor, after due enquiry shall be made (New Zealand Gazette 1865, p. 187)

There were several complicating factors in this situation. One was that both government

officials and the military in the 1860s used the name "Ngaiterangi" to describe all the Maori

in the district now known in Maori terms as Tauranga Moana. The reality was that Ngai Te

Rangi, a tribe of Mataatua descent, comprised a number of different hapu, who had settled

mainly on lands east of the Waimapu River, on Matakana and other islands and the coastal

fringes of Tauranga Harbour at Te Papa, Otfimoetai and the Katikati district. Ngati Ranginui,

a tribe of Takitimu descent comprised several hapu between the Wairoa and Waimapu Riv

ers, and Pirirakau occupied the Te Puna district west of the Wairoa. To the north, Hauraki

tribeslodged claims to the Katikati Te Puna district. Along the Kaimai range were several

hapu, descended from the original tangata whenua as well as Tainui ancestors, who held

rights inside the Tauranga confiscated lands. In particular, Ngati Haua and others had occu

pation rights at Omokoroa and various hapu of N gati Raukawa held customary rights in the

Kaimai district and valley of the Wairoa River. To the south-east and east Te Arawa inter

ests overlapped, particularly those of Wait aha of the Te Puke district and Ngati Rangiwewehi

inland around Piiwhenua-~igure~21.

At the time of Governor Grey's visit in August 1864 it was "agreed" by a few "Ngaiterangi

chiefs" that the lands that became known as the Katikati Te Puna Purchase would be "sold"

11

to the Crown. This transaction was disputed by hapu not party to it. The land which became

known as the Confiscated Block, was "agreed" should be between the Wairoa and Waimapu

Rivers, although a subsequent decision to extend this west across the Wairoa River into Te

Puna created a further grievance among Pirirakau and other inland hapu in particular. The

Te Papa peninsula itself, south to Gate Pa, an area of 1333 acres, had been granted by the

Land Claims Commission to the Church Missionary Society on the basis of a "purchase"

before 1840 (AJRR 1863, D-14). The balance area of the Tauranga confiscated lands made

up the "Lands Returned" (Figure 1).

In the period 1865-1867 negotiations with local people over reserves and other matters were

the responsibility of James Mackay Jr. and Henry Tacy Clarke, Civil Commissioners at

Thames and Tauranga respectively. One of their tasks was to investigate the claims ofHauraki

or Marumahu tribes in the Katikati Te Puna Block, and reserves to be allocated to Tauranga

Moana people in this area. They were also largely responsible for allocating reserves in the

Town of Tauranga and the Confiscated Block. The "Tauranga confiscated lands" comprise

the whole area proclaimed under the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863 (New Zealand

Gazette 1865, p 187). The "Confiscated Block" is the approximately 50,000 acres retained

by the Crown. The "Katikati Te Puna Block" is described as a purchase in many reports but

this transaction was really a form of compulsory acquisition by the Crown. The term cession

was also used for this acquisition which reflected the conflict between Governor Grey and

his Ministers over policy on confiscation (see AJHR 1864, B-2, Dalton 1967, Riseborough

1994). The effect of this debate on the ground in Tauranga Moana was that the Crown

acquired both the Katikati Te Puna and Confiscated Blocks, and the Town of Tauranga

(CMS Block) and reserves for Maori were allocated in all these blocks by Clarke and Mackay.

On 10 October 1867 the Tauranga District Lands Act 1867 was passed, validating all agree

ments and awards within the Tauranga confiscated lands to date. . The Tauranga District

Lands Act 1868 amended the Schedule to the 1867 Act to describe more accurately the

boundaries of the Tauranga confiscated lands. In 1868, Henry Tacy Clarke was appointed

Commissioner of Tauranga Lands. His task was to conduct the "due inquiry" stated in the

1865 proclamation and Tauranga DistrictLands Act 1867 "for the purpose of determining

12

for what persons of the tribe Ngaiterangi three-fourths in quantity of the lands" in the Tauranga ( .

confiscation "shall be set apart". Clarke was to operate under the provisions of the Tauranga

District Lands Act 1867 and the Commissioners Powers Act 1867 (New Zealand Gazette

1868, p. 354).

Clarke remained Commissionerunti11876 apart from a period in 1870 when William Gilbert

Mair held the position. From 1876 to 1878 the Resident Magistrate at Tauranga:; Herbert W.

Brabant, was appointed, and then J.A. Wilson was appointed (New Zealand Gazette 1878,

pp. 91,452,454,1088). Wilson was also a Judge of the Native Land Court and his duties

there prevented his working full time on settling Tauranga lands. In his report to the Native

Minister (AJHR 1879, G-8) Wilson summarised the situation in early 1879:

Administration completed 19,734 acres Administration incomplete 38,951 A waiting administration 77,636 Confiscated-military settlement 50,000 Katikati Te Puna Purchases 88,500

Total contents of block 274,821 acres

This total was considerably more than the estimated 214,000 acres stated in the 1865 procla

mation, but sti11less than the figure of 290,000 acres accepted in the inquiry into confiscated

lands by the Sim Commission in 1927 (AJHR 1928, G-7). Wilson also commented:

. this schedule shows the area of the block to be 60,000 acres above the highest estimate hither to made - all previous estimates being necessarily vague, and varying, I believe, from 208,000 to 215,000 acres (AJHR 1879, G-8, p. 2).

Over the period January-July 1879 Wilson investigated another 7 blocks, a total of 13,221

acres, and "of my predecessors' transactions I have individualized in Court, and partially

administered in way of surveys, roads &tc., 38,951 acres" making a total of 52,172 acres,

within which "I have set aside upwards of 7,000 acres as reserves for the Natives which, I

think, should be inalienable" (ibid). The issue of alienability and restrictions on alienation

of reserves, discussed in chapter 9, is important, as many of Clarke's awards were granted

with no restrictions on alienation.

(

(

1

13

At the end of 1880 H.W. Brabant, already Resident Magistrate at Tauranga, assumed again

the additional role of Commissioner of Tauranga Lands. In May 1886 Brabant reported to

the Native Minister that he had completed his task of "settling the titles to the lands returned

to the Ngaiterangi Tribe under the Tauranga District Lands Acts, 1867 and 1868" (AJHR

1886, G-lO, p. 1). Wilson and Brabant were concerned principally with the "Lands Re

turned", which Brabant estimated contained a total of 136,191 acres in 210 blocks, exclud

ing the Katikati Te Puna Purchase, Town of Tauranga and Confiscated Block.

Th~"surveys of these lands have all been completed, and the certificates of investigation of title have been sent to your office, with the exception of three which are now being prepared.

Applications have been and are being received from Natives for the subdivision of these lands, but these will be left for the ordinary operation of the Native Land Court after the Crown titles have issued (AJHR 1886, G-lO, p. 1).

After 1886 all "reserves" granted to Maori that had not been sold were treated as Maori land

within the jurisdiction of the Native Land Court. The few blocks of Crown land set aside as

"Native reserves" under Native Reserves Acts were, by 1886, administered by the Public

Trustee, mainly as educational endowments, and are reviewed in Chapter 12.

The process of allocation of reserves for Maori in the Tauranga confiscated lands was drawn

out over a long period from 1865 to 1886. The emphasis was on individualisation of Maori

titles, and most reserves were granted to three or fewer individuals in the Katikati Te Puna

Purchase and Confiscated Block. In the Lands Returned, the Commissioners followed more

closely the procedures of the Native Land Court under the Native Land Act 1873, and awarded

blocks to much larger groups of owners.

There were further differences in the way reserves were allocated in the 1860s and 1880s.

Immediately after the confiscation of Tauranga lands in 1865 and until about 1868, a pri

mary concern was whether a grantee was "friendly" or "loyal". No lands were to be granted

to "rebels". Reserves were awarded to individual "chiefs" as "compensation" or for "serv

ices rendered". This was the case in the lots awarded to individuals in the Town of Tauranga

and Township of Greerton which included grants to Te Arawa "chiefs" of tribes who were

not tangata whenua in Tauranga Moana. Another category of grants to "surrendered rebels"

14

was significant in the Confiscated Block. The people who had retreated inland and were still (,

labelled as "rebel" or "Hauhau" in the late 1860s were not eligible for reserves, and an

unrecorded number of people received no land grants in ancestral lands in the Confiscated

Block. By the time the Commissioners were dealing with the "Lands Returned" in the 1880s

the identification of "rebels" had become unimportant. By this stage, according to Commis-

sioner Wilson, the aim was to allocate 50 acres per head of Maori population as inalienable

reserves (AJHR 1879, G-8, p. 2). Commissioner Brabant appears to have conducted inves-

tigations of title along similar lines to the process in the Native Land Court. There is little

information about how earlier commissioners conducted their inquiries.

In previous reports (Stokes 1990 and 1992) the limited evidence of how reserves were nego

tiated has been reviewed and comment made on the gaps in documentation. In this report the

focus is on the actual reserves that were allocated, the complexities of administration, and

the factors that combined to allow many so-called inalienable reserves to be sold. The aim in

tracing through the title records available in the Maori Land Court, Land Titles Office and

Department of Survey and Land Information (now Land Information New Zealand) has

been to establish who was granted land, on what conditions, and try to determine how much ( ,

land each hapu was allocated. In Chapter 2 the relevant legislation is reviewed. The report

then considers the terms of "surrender" in 1864 and negotiations over Katikati Te Puna

Blocks 1864-1866 (Chapters 3 and 4), confrontations over survey of the Confiscated Block

(Chapter 5) and renewed military action in the "Tauranga Bush Campaign" in 1867 (Chapter

6). Chapter 7 reviews the operations of Commissioners appointed under the Tauranga

District Lands Acts 1867 and 1868. The grants made to named individuals in the Town of

Tauranga, Confiscated Block and Katikati Te Puna "Purchase" are considered in Chapter 8.

An important issue is whether, having allocated reserves to Maori, the Crown should have

been more pro-active in protecting Maori lands; the "restrictions on alienation" are consid-

ered in Chapter 9. These did not prevent sales to either Crown or private purchasers before

1886, or after, when Maori lands in the Tauranga confiscation came under the jurisdiction of

the Native Land Court. The allocation of reserves to "half-caste" families is reviewed in

Chapter 10. Reserves in the Town of Tauranga and Township of Greerton and various

endowment reserves are reviewed in Chapters 11 and 12. A summary of reserves allocated

(

15

to Maori by 1886 has been compiled in Chapters 13 and 14 with some concluding comments

in Chapter 15.

16

2. Legislation for "Native Reserves".

The term "reserve", or more usually "Native reserve", was often used very loosely in nine

teenth century land dealings. Its usual meaning before 1865 was land that had been "re

served", or excluded from the sale of a defined block of Maori land to the Crown, for the

continuing use or occupation by Maori, or to protect a wahl tapu. Such lands normally

remained in customary Maori tenure until brought before the Native Land Court for investi

gation of title sometime after 1865. However, there were also lands which, for various

reasons, had become Crown lands and were subsequently set aside as "Native reserves". In

oth~r words, these were Crown lands that were "reserved for Native purposes", either a

specified use such as a Native school or hostelry, or some unspecified benefit generally.

This important distinction was also made in the reserves in the confiscated lands. Some

Native reserves remained Crown lands and were administered by the Crown under various

Native Reserves Acts. Some reserves "for general Native purposes" were subsequently

referred to the Native Land Court for determination of owners and became Maori land.

Many reserves were awarded as Crown grants to named individuals, and in due course came

(

under the jurisdiction of the Native Land Court as Maori land, if they had not been sold in the (

meantime.

The administration of Native reserves that were Crown lands was formalised in the Native

Reserves Act 1856 which in its Preamble stated:

Whereas in various parts of New Zealand lands have been and may hereafter be reserved and set apart for the benefit ofthe aboriginal inhabitants thereof, and it is expedient that the .same should be placed under an effective system of management: And whereas the title of the said aboriginal inhabitants has been extinguished over some portions of such lands, and over other portions thereof such title has not been extinguished.

The Act provided for the appointment of "Commissioners of Native Reserves" who had full

powers and discretion to manage lands in their jurisdiction which, in section 6:

shall have been or shall be reserved or set apart for the benefit of the said aboriginal inhabitants over which lands the Native title shall have been extinguished, such Commissioners shall have and exercise over such lands full power of management and disposition, subject to the provisions of this Act; and, subject to such provisions, may exchange absolutely, sell lease or otherwise dispose of such lands in such manner as they in their

(

17

discretion shall think fit, with a view to the benefit of the aboriginal inhabitants for whom the same may have been set apart. And no purchaser lessee or other person paying money to such Commissioners shall be afterwards answerable for such money or be bound to see the application thereof.

However, in section 7, any sale, exchange or other alienation of such lands, including a lease

longer than 21 years, required the assent of the Governor. The Governor's assent was also

required to enable a Commissioner of Native Reserves, in section 8, to:

set apart any such lands as sites for churches, chapels or burial-grounds, and also by way of~pecial endorsement for schools, hospitals or other eleemosynary [charitable] institutions for the benefit of the said aboriginal inhabitants, and may either manage such lands forthe benefit of such special endowments, and may exercise in relation thereto the same powers as are hereby vested in them, or may with such assent as aforesaid transfer such lands to any person or persons body corporate or bodies corporate as Trustees of such endowments, subject to such provisions for insuring the proper application thereof as may be thought fit.

In section 14 provision was made for any lands reserved from a sale to the Crown to be

brought under their Act by the Governor "with the assent of such aboriginal inhabitants"

which in section 17 was to be ascertained and reported on by "some competent person"

appointed by the Governor. There was also provision in section 15 for conveyance or lease

of any lands in the jurisdiction of the Act:

to any of the aboriginal inhabitants for whose benefit the same may have been reserved or excepted, either for or without valuable consideration, and either absolutely or subject to such conditions as the said Commissioners may think fit.

The 1'~?_6 Act was amended by the New Zealand Native Reserves Amendment Act 1858, the

purpose of the amendment explained in the long title: "An Act to enable Commissioners of

_;Nf!!i~~ Reser~es t2_ Su~_~~_~~~!!ed'~"-_!!!!~~Ac!E~t ~~~_ a C_~~S~!~~~~'P~_~so~~y ~ab~~': __

unless "he shall be guilty of wilful neglect or default" .

In section 2 Native Reserves Act Amendment Act 1862, the Native Reserves Act 1856 was

amended so that the powers vested in Commissioners of Native Reserves were cancelled and

"shall vest in and may be exercised by the Governor". It also provided in section 7 for

extinguishment of "Native title" by Order in Council of the Governor "as effectually as if the

same had been ceded and conveyed by such Aboriginal Inhabitants to Her Majesty". In

18

section 8 the Governor could delegate powers to Commissioners who could advise him. The (

lands and revenue, and power to issue grants, remained with the Governor and Executive

Council who had to authorise any action of a Commissioner. A single full-time Commis-

sioner based in Wellington, George Swainson, was appointed. As Professor Ward com-

mented, "High-flown humanitarian theories of how Maori would benefit from the increased

value of their reserved lands" did not outweigh the reality that Maori did not control, nor

participate in the administration of Native reserves (Ward 1995, p.l51).

The Native Lands Act 1867, at section 13 provided that every Crown grant:

issued of any land comprised in any Native reserve shall contain a provision that the land therein comprised shall be inalienable except by the consent of the Governor by sale or mortgage or by lease for a longer period than twenty-one years.

This provision meant that when any Native reserve lands were granted to Maori then a re

striction on alienation applied. This also applied to reserves for Maori in the confiscated

lands, which became Crown lands by virtue of the proclamation of a confiscation under the

New Zealand Settlements Act 1863, and which, ipso facto, extinguished Native title.

The powers of the Governor to set aside lands by proclamation as reserves within areas

confiscated under the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863 were set out in the Confiscated

Lands Act 1867. In section 2 provision was made in cases where it was considered "just and

reasonable" when the Compensation Court either had not made, or had made insufficient

reserves, for the Governor to grant:

such. lands as to him shall seem fit for the purpose of compensating such persons of the several hapu or tribes whom he shall consider to be entitled to land by way of compensation or for whom he shall consider the same necessary by way of provision and out of such lands so reserved to grant such portion or portions thereof as he shall think fit to any such person or persons aforesaid or by warrant under his hand to set apart such portion or portions as he may think fit of such lands for the benefit of any such persons as aforesaid.

Native reserves could be granted to individuals or could be retained as Crown lands reserved

for general or specified "Native purposes". Grants to named persons would be made to

"friendly Natives" under section 3 whom the Governor shall think deserving and shall ap

pear to him to have acted in the preservation of peace and order and in suppressing the

( \

(

19

rebellion". In section 4 provision was made for grants for "surrendered rebels" who "have

been in rebellion and have subsequently submitted to the Queen's authority". There was

provision in section 5, in lands granted to more than one person, for subdivision of the grant

by partition by the Native Land Court under the Native Lands Act 1865. Sections 6 and 7

provided that some reserves that remained Crown land could be set aside by proclamation

for any specific purpose or for the benefit of Natives generally. Such reserves were in the

nature of endowments and are discussed separately in Chapter 12.

The 'Tl:l.uranga lands were confiscated by Order-in-Council in.1865 under the New Zealand

Settlements Act 1863 (New Zealand Gazette 1865, p. 187) but no Compensation Court pro

vided for under that Act was constituted in Tauranga. The reason given was that no cases

had been referred to it (AJHR 1867, A-13). Because there had been applications to the

Native Land Court for investigation of title to lands at Tauranga, Chief Judge Fenton an

nounced his intention to hold sittings in Tauranga in December 1865 but was advised that

the confiscated lands were outside the jurisdiction of this Court (Stokes 1990, pp. 141-144).

The proclamation confiscating Tauranga lands in effect extinguished Maori customary title

) in the whole area described in the Schedule, regardless of any promises by the Governor or

anyone else to return some lands to Maori ownership by way of a Crown grant or reserves

from purchase.

In 1866 the Civil Commissioners at Tauranga and Thames, Henry Tacy Clarke and James

Mackay Jr., had negotiated purchase agreements for the Katikati and Te Puna Blocks (Turton

1877 ,Deed Nos. 458-461). A number of "reserves" were listed in Deed No. 461 which were

described as "Lands Returned To Natives" (see Chapters 3 and 4). The legal situation was

that, as confiscated lands, the Katikati and Te Puna "purchases" were already Crown lands

by proclamation under the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863. The "reserves" in this case

were lands which the Crown agents, Civil Commissioners Clarke and Mackay confirmed,

after some (undocumented) negotiation, should be returned to Maori by way of Crown grants

or retained by the Crown as reserved for native purposes. To quell any concern over these

proceedings the Tauranga District Lands Act 1867, at section 2, validated "All grants, awards,

contracts or agreements of or concerning any of the land" included in the Tauranga lands

20

confiscated by proclamation under the New Zealand Settlements Act.

In 1869 Chief Judge Fenton of the Native Land Court, who was also a member of the Legis

lative Council, introduced a Native Reserves Bill, largely of his own drafting, which pro

vided for the repeal of previous Native Reserves Acts and the relevant sections of the N ati ve

Lands Act 1867, and the extension of the jurisdiction of the Native Land Court over "any

Native Reserve to which the Native title has been or shall be extinguished". Although the

Bill was passed in the Legislative Council it was defeated in the House of Representatives

and did not become law, mainly on the grounds of opposition to extending the powers of the

Naiive'Land Court and possible restriction on alienation of reserve lands (Ward 1995, pp.

251-252).

While this debate was going on, the Native Minister, Donald McLean appointed Charles

Heaphy as Commissioner of Native Reserves in October 1869. His duties were:

1. The administration of Native reserves held in trust by the Government, and other lands set apart for the benefit of the natives.

2. The supervision of Native hostelries.

3. The supervision and payment to the Natives of the proportionate amount due to them on sale of certain blocks at Remuera and elsewhere.

4. The supervision of lands taken under "The New Zealand Settlements Act, 1863", and "The New Zealand Settlements Amendment Act".

5. The recommendation to the Government of lands proper to be rendered inalienable ,by the Native owners, through the operation of the Native Lands Court, and generally the duties devolving on the "Trustee" contemplated in the provisions of the Native Reserves Act [sic], which passed the Legislative Council last Session.

6. A general supervision over the laying off of the main lines of road through the North Island, and setting apart of districts of land suitable for immigration from Europe (AJHR 1870, D-16, p. 3).

In his letter offering the appointment to Heaphy, McLean noted "your knowledge of the

circumstances under which most of the lands were set apart, your long experience as a sur

veyor in the various Provinces, and on the confiscated lands, and your acquaintance with the

tribes". McLean also suggested that Heaphy establish his office in Auckland, because "much

(

( "

(

21

of the work incidental to confiscated lands and reserves will lie in the North, together with

the greater part of that connected with the operation of the Native Lands Court". Heaphy

was also required "to classify the various Native reserves as soon as possible, bringing them

all under one schedule that shall be descriptive of the objects and circumstances of the trusts"

(AJHR 1870, D-16, p. 3). Over the next two years detailed schedules of Native reserves in

each Province were prepared and presented to Parliament. The list for Auckland Province,

containing reserves in the Tauranga confiscated lands, was presented in 1871 (AJHR 1871,

F-4).

The Native Reserves Act 1873 replaced all previous legislation and provided an administra

tive framework for Native reserves headed by the Commissioner, and a number of District

Commissioners who were to be advised by a Board containing three elected Maori repre

sentatives. The jurisdiction was set out in section 4:

This Act shall apply to all Native reserves heretofore made or hereafter to be made for the use or benefit of Aboriginal Natives; and the term "Native reserve" shall for the purposes of this Act include all lands and moneys issuing out of land which may have been or which may hereafter be reserved set apart or appropriated upon trust for the benefit of Aboriginal Natives under the provisions of this Act, or of any law heretofore in force or hereafter to be in force in the Colony, or under provisions of any contract promise or engagement heretofore lawfully made or entered into, or hereafter lawfully to be made or entered into with Aboriginal Natives.

The Native Reserves Act 1873 thus provided for the administration of Crown lands set aside

for specified or general Native purposes, as well as for certain reserves, still in Maori owner

ship 'Y!rich were being administered on trust for Maori beneficiaries. In this latter category

wereoanumber of reserves, such as the Wellington and South Island "Tenths", many the

subject of perpetual leases, a category of lands later known as "Maori Reserved Lands".

There were no lands in this category in the Tauranga confiscated lands. In the 1870s various

"reserves" were allocated to individual Maori in both the Confiscated Block and the Katikati

Te Puna Block, as well as in the Town of Tauranga and Township of Greerton. Although

many of these were listed in Heaphy's 1871 Schedule of Native Reserves in Auckland Prov

juce most were awarded as Crown grants to individuals and no longer considered to be

reserves under the Native Reserves Acts. Some Native reserves listed as such in 1871 were

22

referred to Commissioner Brabant for determination of Maori owners under the Tauranga (

District Lands Acts 1867 and 1868. A few "reserves" which for various reasons had not

been awarded as Crown grants were subsequently referred for investigation by the Native

Land Court. After 1886, when Commissioner Brabant had completed his investigations of

Tauranga lands under the Tauranga District Lands Acts, all "reserves" Crown granted to

Maori came under the jurisdiction of the Native Land Court as Maori land.

The only Native reserves in the Tauranga confiscated lands under the jurisdiction of the

Co~ssioner of Native Reserves under the Native Reserves Act 1873 were those for speci

fied purposes,such as a Native hostelry or school site, Native purposes generally, or endow

ments for schools or hospitals. Legally these remained Crown land reserved for the pur

poses set out in a notice in the New Zealand Gazette.

In his 1871 report Heaphy had commented that the 21 year maximum for a lease of any

Native reserve was "too short a term to be attractive to good tenants" and recommended

extension to 40 years, but this was not implemented. The revenue raised from such leases

was:

but a small income in relation to what is necessary for the legitimate - I do not allude to the political- government of the Natives. Educational and industrial institutions for their benefit are necessary, as well as hospital and lunatic and other asylums. All these expenses, which, whether borne by Provincial or General Governments, must be heavy, might be met by landed endowments.

··lwDuld, therefore, recommend a very considerable addition to be made to the reserves in confiscated blocks for such purpose, and append a list (List E) of convenient lands.

, :.

It is proper , however, to contemplate the arrival of a time when no distinction of race will exist as far as these purposes are concerned, and I would recommend that the terms of the trust should not be of such nature as to make the revenue available exclusively for the benefit of the Maoris (AJHR 1871, F-4, p. 5, emphasis in original).

Charles Heaphy remained Commissioner of Native Reserves, providing an efficient, if pa

ternalistic, administration until his death in 1881. In the Native Reserves Act 1882 the

administration of Native reserves hitherto vested in the Governor and Commissioner ofNa

tive Reserves was transferred to the Public Trustee. Not all reserves were immediately

transferred as the following summary submitted by the Public Trustee to the House of Rep-

I(

(

23

resentatives on 4 August 1885 indicates:

Previous to the death of Major Heaphy there were three Commissioners of Native Reserves - viz., Major Heaphy, Major Parris for the North Island, and Mr Alexander Mackay for the South Island. Upon the happening of that event, Mr Mackay was appointed sole Commissioner for the colony, which position he occupied until his appointment as Judge of the Native Lands Court on 1st July last, when he resigned the Commissionership of Native Reserves. The administration of such of the Native Reserves as fell within the definition of the Act next hereinafter referred to was transferred from the Commissioner of Native Reserves to the Public Trustee by "The Native Reserves Act,1882", and, since 1stJanuary 1883, the Public Trustee has been the responsible officer. There are, however, a number of reserves which do not fall under such definition, as to which the Public Trustee has no knowledge (AJHR 1886, G-7).

Most of the remaining Native reserves seem to have remained with the Public Trustee until

transferred to the administration of the Native Trustee in the 1930s. However, as will be

outlined in Chapter 12, many were diverted to other uses, a tacit acceptance of Heaphy's

recommended policy that Native reserves were not exclusively intended for the long-term

benefit of Maori.

In general, the concept of reserves for Maori, although ill-defined, was based on a desire to

ensure there were some lands for Maori use and occupation, and, to a lesser extent, to pro

vide endowments to fund social services for Maori, such as schools and hospitals. Over

riding this, however, was a much stronger policy which assumed longer-term assimilation of

Maori, and was implemented by the process of individualisation of title to Maori land. Al

though the Tauranga confiscated lands remained outside the jurisdiction ofthe Native Land

Courtunti11886, the aim of individualising Maori title was just as relevant. Complicating

the is'sue further in the Tauranga lands was the fact of confiscation itself which, ipso facto,

extinguished "Native title" or Maori customary tenure of land. The ancestral estate was

taken by the Crown, and re-allocated by commissioners, appointed by the Crown, who were

not required to take into account ancestral use and occupation, merely to ensure there were

sufficient reserves for Maori. The concept of sufficient reserves also remained poorly de

fined, and there was no effective protection mechanism to ensure that the reserves allocated

to Maori remained in Maori control. The result in Tauranga Moana, as will be outlined in

the following chapters, was that on top of the loss ofland in the Katikati Te Puna "purchase"

24

and Confiscated Block, traditional rights to land and resources were overturned, reserves (

were granted to some in areas where they had no ancestral rights, and social and economic

pressures were such that many of the reserves were also lost by 1886.

'"

(

(

25

3. The Katikati Te Puna ''Purchase'' 1864

The decision of the Crown to purchase the Katikati Te Puna Block appears to have been

made at the time Governor Grey, accompanied by Colonial Secretary and Native Minister

Fox and Attorney General Whitaker visited Tauranga on 5-6 August 1864. The official

record of proceedings was compiled from notes made by Civil Commissioner H.T. Clarke

and Government Interpreter E.W. Puckey. On 5 August there were speeches from local

rangatira welcoming the Governor and acknowledging that the "mana" or "authority" over

the land had been given up to the Governor. Clarification of this was sought by Grey:

Te Harawira replied: What we mean by the mana of the land being given up to you is, that you may consider the mana of the land yours. You may occupy it. Permit us to do so or not, as you please ....

I mean that you are to hold the land as your own, and to do what you like with it. When we made our submission to the Colonel, we gave up our arms and ourselves. The question about the land was left for you to decide; the decision therefore rests with you.

His Excellency thereupon made the following reply: I regret that you should have committed yourself to the evil courses which have caused so much misery to so many people. But since you have done this, you have made the best amends in your power by the absolute and unconditional submission you have made to the Queen's authority, which submission is hereby accepted by me on the Queen's behalf. I will see you again tomorrow, and will then inform you of the decision which has been come to upon all those questions we have spoken of this day; in the meantime informing you that in as far as circumstances will admit of you shall be generously dealt with. You will, for the future, be cared for in all respects as other subjects of the Queen; and the prisoners taken at Pukehinahina (Gate Pa) and Te Ranga shall be allowed to return to you, if you undertake to be responsible for their future good contact (AlHR 1867, A-20, p. 5. Emphasis in original).

At this stage the Governor appears to have accepted on behalf of the Queen a surrender of

the "mana of the land" by the rangatira of Tauranga Moana, and that local people accepted

the authority of the Crown and the right of the Governor to make decisions about their land,

including occupying it. However, we do not have a version of this in the Maori language to

determine just what the rangatira were saying to Grey. Nor is there a complete record of

Maori attendance which might indicate how representative of local hapu and iwi this hui

26

might have been. It is highly unlikely that the rangatira said they were giving up all their (

rights to the Tauranga Moana land, certainly not permanently alienating it. This interpreta-

tion is borne out in Grey's "promise" to deal with them "generously" and treat them "as

other subjects of the Queen". This message was reinforced in Grey's speech to the assem-

bled rangatira on 6 August:

At present I am not acquainted with the boundaries or extent of your land, or with the claims of any individuals or tribes. What I shall therefore do is this:- I shall order that settlements be at once assigned to you, as far as possible, in such localities as you may select, which shall be secured by Crown Grants to yourselves and your children. I will inform you in what manner the residue of your lands will be dealt with.

But as it is right in some manner to mark our sense of the honourable manner in which you conducted hostilities, neither robbing nor murdering, but respecting the wounded. I promise you that in the ultimate settlement of your lands the amount taken shall not exceed one-fourth part of the whole lands.

In order that you may without delay again be placed in a position which will enable you to maintain yourselves, as soon as your future localities have been decided, seed potatoes and the means of settling on your lands will be given you.

I now speak to you, the friendly Natives. I thank you warmly for your good conduct ( under circumstances of great difficulty. I will consider in what manner you shall be rewarded for your fidelity. In the meantime in any arrangement which may be made about the lands of your tribe, your rights will be scrupulously respected (AJHR 1867, A-20, p. 6).

Grey's promises to Tauranga Maori can be summarised:

::1.: Land to live on will be selected in localities to be chosen by the rangatira, and assist

···ance in resettlement (such as seed potatoes) will be given. These lands would be

reserved and secured for their descendants.

2. The Governor would return three quarters of their lands and only keep one quarter.

3. The "friendly Natives" would be rewarded in some way and their land rights would

be respected.

Just how these promises were to be implemented was not explained and, indeed, had prob

ably not been decided at this stage. No discussion of Crown purchase of any Tauranga lands

was recorded at the hui on 5 and 6 August 1864. (

( \

27

The Crown offer to "Tauranga Chiefs"

On 7 August 1864, the day after Grey's promise to return three quarters of the Tauranga

lands, H.T. Clarke wrote to Colonial Secretary Fox:

In obedience to your instructions I held a meeting on Friday night with the rebel Natives who have come in and submitted, for the purpose of endeavouring to ascertain their wishes on the subject of the land which the Governor should retain as a satisfaction for their having joined in the rebellion, and carried arms against Her Majesty's troops. After a dis~ussion of several hours, which was continued the following morning, they unanimogsly declined to adopt any other course than to leave the entire settlement of their lands to His Excellency the Governor, as they had declared at the public interview with him on the previous day, and to receive back from him so much as His Excellency might think proper to restore (AJHR 1867, A-20, pp. 6-7).

Clarke's account does not mention purchase, but Mackay's retrospective report dated 26

June 1867 suggests that the decision to purchase Katikati and Te Puna lands was made by

Whitaker and Fox at the time of their visit to Tauranga with Governor Grey:

His Excellency the Governor, accompanied by the Colonial Secretary and Native Minister (Mr Fox) and the Attorney General (Mr Whitaker) proceeded to Tauranga and on the 5th of August another meeting of natives was held. At this time the Ngaiterangi publicly gave up all their lands to be dealt with as the Governor pleased. His Excellency then said "he would retain one-fourth of the land, and the remaining three-fourths should be returned to the natives after due inquiry had been made". The boundaries of the land to be retained [i.e. the Confiscated Block] were not arranged at that time, which is one of the principal causes of the troubles that have since arisen.

The:ex-rebel natives being disarmed fears were entertained by the Ngaiterangi tribe, that their ancient enemies Taraia and the Thames people, would take advantage of their defenceless position and attack them. The Ongare tragedy of 1840 [sic, Taraia attacked Ongare in 1842] presenting itself to their minds. They therefore offered to sell to the Government all the land between the river Puna and Ngakuriawhare [sic], considering that the occupation of that part of the district by Europeans would place an insurmountable barrier between them and the Thames people. Messrs Fox and Whitaker agreed to purchase the land for the Government. His Excellency and the Ministers returned to Auckland. Shortly afterward several of the leading Ngaiterangi chiefs proceded there, and on the 26 August 1864 they received the sum of one thousand pounds (£1000) deposit on the block of land between Te Puna and Ngakuriawhare, and extending back to the summit of the Aroha range. The understanding was that the land should be surveyed and then when the area was ascertained either two or three shillings (2/- or 3/-) per acre should

28

be paid for the whole of it. The actual rate per acre was never definitely settled (National ( Archives Lel/1867/114).

In his report to the Native Minister on the state of land claims at Tauranga, dated 23 June

1865, Clarke provided some further context to Grey's "promises" and the role of Fox and

Whitaker:

When the Natives made their surrender to His Excellency the Governor the Ngaiterangi gave all their land into the hands of His Excellency.

The friendly Natives were parties to this arrangement.. ..

Before the Governor declared the terms upon which he would accept the surrender of Ngaiterangi, I was instructed by the late Ministers, Messrs. Whitaker. and Fox, to meet the Natives and try to induce them to give up some specific block ofland, but so many difficulties presented themselves, chiefly amongst themselves, that they abandoned the idea and adhered to their first determination of giving up all their land ....

His Excellency the Governor in his reply to the Ngaiterangi told them that he would return to them three-fourths of their land, retaining the remainder as a punishment for their rebellion. The Natives all expressed satisfaction at the liberality of the Governor.

It was afterwards proposed that the block of land to be confiscated was to be that portion ( of Tauranga between the rivers Waimapu, on the south, and Te Wairoa on the north; all . their land to the north of Te Puna the Natives were to be paid for at the rate of three shillings per acre. A deposit of £1,000 was paid upon it, the receipt for which will be found in the Treasury.

With regard to the block of land above described to be confiscated, the Natives, after a little reflection, took exception to the proposition; they stated, with justice, that if it was carried out the punishment would fall heavily upon some, while others would not lose an inch of land, although equally implicated in the war ....

It was also arranged that Ohuki and the Islands of Rangewaea [sic] and Motuhoashould be reserved for the Natives, that the claims should be, as far as practicable individualized, and that they should receive certificates which should be inalienable; this was not intended to exclude them from other reserves that it might be thought proper to make.

It was distinctly understood by the Natives at the time that peace was made, that Te Puna [block] would be absolutely required by the Government, but that it should be paid for. The Natives expressed themselves satisfied with this arrangement as it would place an armed force of Europeans between themselves and the Thames people, who they greatly feared would take advantage of their weakened and disarmed condition to revive some of their old land feuds (AJHR 1867, A-20, p. 12).

(

29

It is difficult to reconcile Clarke's view that Government "absolutely required" the Te Puna

lands for a settlement of the Waikato Militia (who had already arrived at Te Papa Camp),

with a freely made Maori offer to sell to the Government implied in Mackay's report. What

ever the nature of the threat from the "Thames Natives", it could justifiably be interpreted

that, in this transaction, Government Ministers Fox and Whitaker played an important role.

Governor Grey had left Tauranga on the evening of 7 August, but Whitaker and Fox had

stayed another week (Riseborough 1994, p. 27). There is no record of their negotiations but

it seems that these two Ministers took advantage of the disarmed and weakened state of the

Tauranga people by offering the £1000 deposit to a small number of "chiefs" to secure

further land. A number of "Chiefs" travelled to Auckland with Fox and Whitaker, calling on

Governor Grey at Kawau en route, where some prisoners taken at Gate Pa were released

(ibid, p. 29).

Theophilus Reale, District Surveyor, in a report dated 27 June 1865 after 10 months working

in the Tauranga district, provided his view of Grey's promises on 5-6 August 1864 and the

nature of the transaction when £1000 was paid in Auckland on 18 August 1864 as a deposit

on the Katikati Te Puna lands:

In the great loss which the tribe sustained at the Gate Pa and at Te Ranga, every leading supporter of the King movement fell. The remainder of the tribe thoroughly repentant, cordially returned to the old proposal of submission to the Government, and close alliance with the settlers; and in all the terms of their submission, it is evident that their one earnest desire was to bury all the old land feuds for ever, and to become independent of all their tribal enmities and entanglements by complete submission to the Government, and by obtaining the support of a numerous settlement of colonists on their territory .

Thus, at the meeting with His Excellency the Governor the 5th August 1864, all the speakers most emphatically declared that they gave up the mana of all their land absolutely to the Governor, when pressed to explain the mana, they stated they gave up all their land to him for him to deal with it as he thought fit. When informed that only one-fourth part would be confiscated, and pressed to set aside a block ofland for that purpose, they again unanimously declined to adopt any other course than to leave the entire settlement of the lands to the Governor ....

Subsequent to these terms being made at Tauranga with the Natives who had been in rebellion, a number of the loyal Natives went to Auckland to arrange more fully the carrying them out and on the 18th August further promises were made:

30

1. That surveyors should be sent back with them.

2. That roads should be commenced, and the Natives be employed on them.

3. That European settlers should speedily be sent.

4. That Crown Grants should be issued to the Natives &c.

And as it was found that any block of land which the Government might take by way of confiscations would be embarassed by claims to particular pieces, preferred by loyal members of the tribe, a purchase was made from these to include all lands belonging to the sellers, which the Government might take at three shillings per acre, and £1 ,000 was paid on account of this purchase, a sum which, at the price named, is likely to cover any claims .they have on the block required by the Government, which it was given out and understood was for the settlement of the 1 st Waikato Regiment.

The writer of this paper was employed to conduct the surveys, and in fulfIlment of the promises of the Government, he returned to Tauranga with the Natives accompanied by several assistants (AJHR 1867, A-20, pp. 13-14, emphasis in original).

There is no documentation of an agreement to sell the Katikati Te Puna land to the Crown.

The following "receipt", dated 26 August 1864, sets out the boundaries of this "purchase"

contained within what was not yet gazetted as the Tauranga confiscated lands. The procla-

(

mation of confiscation under the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863, dated 18 May 1865, (

was not published until 27 June 1865 (New Zealand Gazette 1865, p. 187). We have no

record of just how "agreement" was reached with the individuals whose names appear on

this receipt:

W,e whose names are hereunto subscribed have received from Henry T. Clarke on this 26th day of August [1864] the sum of £1000. This money is to rest upon one piece ofland at Tauranga. The commencement of the boundary is· at Ngahuria Whare [Nga Kuri a Wharei] to the north of Katikati, following around the outside boundary line of all the Ngaiterangi claiI:D.s. The boundary from the south is from Te Puna; thence running to the forest right across to one outside boundary line. The road to Waikato is within this piece of land now made sacred by this money to the Government (AJHR 1867, A-20, p. 6).

There followed a list of nine names of Tauranga rangatira, and the two interpreters, E.W.

Puckey and James Fulloon, who "witnessed the writing of the names and the giving of the

money". However, the names on this receipt do not entirely tally with a published "List of

Natives and Hapus who received the £1000 from Mr Henry Clarke" (AJHR 1867, A-20, p.

6).

(

31

Receipt List Clarke's List

Hohepa Hikutaia Hohepa

Wiremu Parera Parera

Wiremu Patene

Tomika Te Mutu Tomika

TePatu [?] Turere

,~urere Turere

Harniora Tu Harniora Tu

Raniera Te Hiahla Raniera

Bnoka

Tamati Mawao [sic]

Hapu Amount £

N gaitukairangi 91

Ngaitamawhawa [sic] 91

Ngaituwhiwhia

TePatu

Patutohora

Te Materawaha [sic]

"

91

91

91

91

91

272

91

£1,000

While nine names appear on each list there are unexplained discrepancies. On Clarke's list

the name Turere appears twice with the name Te Patu appearing under hapu, adding to the

confusion. The omission of Bnoka Te Whanake from the receipt list would explain his

remark at a meeting held by Colonel Haultain "with the Tauranga Natives" on 26 February

1866, at which he reminded them of the "agreement made in reference to the purchase of

certain lands for which you received one thousand pounds". To this Bnoka responded:

If the matter of the one thousand pounds (£1,000) had been done by all the tribe, well- but it was the work of the men who went to Auckland. I knew nothing of the arrangement to sell land at Katikati. Can you tell me where the boundaries are? Some of the people who lived peaceably on that land would object to being involved in that manner (AJHR 1867, A-20, p. 20).

It is tempting to suggest that Clarke's undated list was compiled later from memory, but this

does not explain why Bnoka, who claimed he did not go to Auckland and did not sign the

receipt, was recorded as receiving £272. No other documentation has been found which

might explain these discrepancies as no written agreement to sell was made.

32

In response to a request in June 1865 for some record "of the alleged purchase ofTe Puna (

&c. on which £1000 is said to have been advanced", H.T. Clarke replied:

The receipt for the £1000 will be found in the Treasury - the object for which the £1000 deposit was paid is stated on the face of the document. No other record that I am aware of has been kept (DOSLI files 1/5).

Filed with this is a document headed "Copy of Notice to Europeans" which is undated, but

probably issued in July 1866:

Whereas on the 6th August 1864 the tribe Ngaiterangi received from H.M. Govt. the sum of One Thousand Pounds (£1000) on account of their claims to a certain block of land in the District of Tauranga the boundaries whereof are hereafter described. And whereas by Deeds bearing date the 7th July 1866 the tribes Ngatitamatera, Ngatimaru and Tawera, absolutely conveyed and released unto the Crown all their rights title and interest in and to the said lands, I hereby caution all persons whatsoever from having any dealings in respect of, or paying any money on, upon, or on account of any portion of the said lands.

[signed] James Mackay Jr Civil Commissioner

Boundaries of the said lands referred to - Commencing on the seacoast at Ngakuriawhare[i] thence to the Arohaauta, thence along the summit of the watershed range to Mangakaiwhiria ( thence to Te Puna [stream] thence the seacoast to the point of commencement.

N.B. The District commencing at Ngakuriawhare[i] and extending to Wairakei is at present subject to the provisions of the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863 - 1865 (DOSLI files 1/5).

This boundary description includes all the land included in the Katikati Te Puna Purchase,

although the boundary was not yet surveyed. The boundaries of these blocks are considered

further below , as the inland boundary was later disputed.

Hauraki Claims in the Katikati Te Puna ''Purchase'',

Through September 1864, after news of the payment to "Ngaiterangi chiefs" was spread

about, a number of complaints were made by Hauraki leaders (Riseborough 1994, pp. 30-31;

National Archives Le1/1865/138).

On 10 September 1864 Nepia Te Ngarara of Ngati Tamatera wrote to Civil Commissioner

Mackay from Ohinemuri, advising that he had been to Mamora "to see about our dead" and

(

33

had found there a group of Ngati Porou who had been at the battle ofTe Ranga in Tauranga.

"We ejected those people as we did not wish them to enter within our boundaries". Ngati

Tamatera also objected to the Crown purchase of Katikati Block: "Katikati was a disputed

place. That place belongs to Ngatitamatera. Now this is very wrong, and that place shall not

be taken" (DOSLI files 1/5). Mackay annotated his translation of the letter on 22 September:

The lands claimed are in the district of Tauranga, and form a portion of those now under negociation [sic] with the tribe Ngaiterangi. The Ngatitamatera have expressed a deter. mination to obstruct the survey when commenced by the Government. The chief Ropata has requested them to remain quiet until the case can be considered by the Gov't (DOSLI files 1/5).

On 13 September 1864 Mackay had also received and translated a letter addressed to the

Governor from Taraia:

I have heard that you [ the Governor] have purchased Katikati from N gaiterangi for £2000. Friend the Governor this is wrong. The reason it is wrong is, you heard our former talk, that Katikati should be left as a burial place for Ngatitamatera, for Ngatipaoa, for Ngatimaru (this probably means they would sooner die fighting on that land, than part with it). Now do you hear Katikati will not be taken from me, because I know your thoughts, that is of you and Ngaiterangi. You are enticing me with a bait. I am frightened, my fright is -Katikati will not be parted with by me. Although you pay for it, it shall not be taken. I told you "if any person came forward to sell Katikati that you were not to give payment". You consented. Now hearken, if evil commences at Katikati that offence is not mine. It is you that cause me to do evil (DOSLI files 1/5).

On 21 September Te Kou 0 Rehua of Tawera (also known as Ngati PUkenga) wrote to the

Governor, objecting to the transaction, claiming ancestral rights in the Katikati Te Puna

lands,'and stated that his people should not be punished because they had not participated in

the fighting. An almost identical letter, also signed by Te Kou 0 Rehua, was sent on behalf of

Waitaha, which also asserted that Ngai Te Rangi rights were based on conquest, that despite

10 generations of occupation, ancestral title remained with Waitaha (Riseborough 1994, p.

31).

On 24 September, Colonial Secretary Fox, wrote to Governor Grey commenting on these

and other objections to the Katikati Te Puna transaction. Fox disagreed with Grey's insist

ence on cession of land, a policy advocated by the Colonial Office (see Dalton 1967, pp.

195-196 and 201), before authorising confiscation of lands from tribes in rebellion, as de-

34

fined in his proclamation of 11 July 1863, the day before imperial troops crossed the (

Mangatawhiri River to invade the Waikato territory of the Maori King Tawhiao. Fox com-

mented:

The Colonial Secretary has had interviews with the writers of the accompanying letters.

He understands that Te Kou-o-Rehua and his people formerly lived somewhere near Katikati, but left during the interminable wars between the Ngaiterangi, the Arawa and Thames tribes, in which no tribe ever achieved acknowledged victory or undisputed possession. The titles of all these seem to rest solely on the barbarian basis, that they fought the;r~. The extended claim now preferred to all the country is believed to be a mere fiction - much like that put in by the Arawas and repudiated by His Excellency when at Tauranga.

This case appears to the Colonial Secretary to afford an early and very clear proof of the inconvenience and impolicy of the cession principle as opposed to that of confiscation. The Native claimant Te Kou-o-Rehua said to the Colonial Secretary "If the Governor had taken this land because he had beaten the Ngaiterangi that would have been well. I should have said nothing; but now that it is being sold by the Ngaiterangi I will assert my claim", and he does assert one of that class of claims which tend inextricably to complicate Native questions about land, and which even by their own law, have no solid foundation.

The other letters refer to a still less agreeable phase of the question. The writers are Taraia who lately went from the Thames to Tauranga with 170 .armed men to fight with ( the Queen's Troops, and who now writes a threatening letter himself, and sends emissar-ies from the non-committed part of his Tribe, who write others, to advocate his claim to Katikati; a claim really based upon the fact that he there celebrated the last cannibal feast which occurred in New Zealand during the temporary administration of Mr Shortland in 1843 [sic = 1842].

The.Colonial Secretary expects unlimited claims of the same sort as these wherever the ~'C~ssion" principle may be attempted, none of which would probably have been heard of hadi~t,he principle laid down in His Excellency's proclamation of 11 July 1863 been consistently adhered to and made the basis of what is after all a forced acquisition of Native Lands under colour of a voluntary sale (National Archives G 17/3 no. 15; quoted by Riseborough 1994, p. 32).

This last remark would suggest that the Katikati Te Puna transaction with "Ngaiterangi chiefs"

was not viewed by the government of the day as an entirely "voluntary sale". Fox and other

ministers were pushing for the confiscation of all the Tauranga lands.

An investigation of the claims of Hauraki tribes to the Katikati Te Puna lands was proceeded

with by Civil Commissioners Clarke and Mackay, although it is not clear who authorised it,

or the terms of reference set for the inquiry. The following panui, signed by Mackay and (

35

dated 31 October 1864 was filed with the letters from Nepia Te Ngarara and Taraia quoted

above:

Ko te ono (6) 0 nga ra 0 Tihema 1864 te ra kua oti te whakarite he ra huihuinga mo Ngatitamatera mo Ngaiterangi mo Te Tawhera ki Akarana ki te kimi i te tikanga mo te whenua i Katikati. Me haeremai 6 nga tangata 0 Ngatitamatera, 6 nga tangata 0 Ngaiterangi, 6 nga tangata 0 Te Tawhera ki Akarana i tana ra.

Kei aua iwi te whakaaro ki a ratou tangata i pai ai ratou he kai korero mo tana whakawa.

This::was an invitation to Ngati Tamatera, Ngai Te Rangi and Tawera tribes to send six

representatives each, to Auckland, for a hearing of their claims on 6 December 1864. Each

tribe was to appoint a spokesman to argue his tribe 's case. It is not clear how this notice was

promulgated or what discussion preceded it. The file copy was annotated by Mackay "Copy

given to Kahukura". However, the notice suggests that it was intended to limit the attend

ance at the hearing to six from each tribe and restrict proceedings to the appointed spokes

men for each. The restrictions in this notice suggest that it was not considered necessary to

have representatives of the other Hauraki tribes, Ngati Paoa and Ngati Maru, present, nor

any others such as Pirirakau, Ngati Tokotoko, Ngati Hinerangi and so on who did not recog

nise any Ngai Te Rangi right to offer the Katikati Te Puna land to the Crown.

In a report dated 26 June 1867 Mackay provided a retrospective view of events leading to the

arbitration proceedings over Katikati Block:

which had for many years been disputed between the Thames and Tauranga people. When the Thames natives heard of the payment of the deposit (£1000 to Ngaiterangi), Te Mbananui, several of Taraia's relations and others of the tribe Ngatitamatera came to Auckland and objected to the Ngaiterangi selling the land. The Tawera tribe of Manaia, Hauraki also entered a protest against it. All these natives had an interview with Mr Fox at which myself and Mr H.T. Clarke, Civil Commissioner at Tauranga, were also present. It was then proposed to settle the question by arbitration. This was at once agreed to by the natives: The Thames people asking me to act on their behalf and Ngaiterangi electing Mr Clarke to be their arbitrator.

In December 1864 delegates from the Ngatitamatera, and Tawera tribes of the Thames and

the Ngaiterangi of Tauranga met at Auckland, and their claims were investigated by myself

and Mr Clarke as arbitrators (National Archives Lel!1867/114).

36

On 27 December 1864 Clarke and Mackay reported on their investigation which had been (

conducted over five days from 12 December. Te Moananui Tanumeha was spokesman for

Ngati Tamatera and the Tauranga people were represented by Hohepa Hikutaia and Te

Harawira. The decision of the arbitrators recognised Te Moananui's claims to Katikati Block,

and his descent from Ranginui, who with Waitaha were "the original owners of Tauranga

district". Ngai Te Rangi had "no claims by right of inheritance ... but they have their claims

on right of conquest only". It was also agreed that Katikati had been occupied by both Ngati

T~atera and Ngai Te Rangi and there had been periodic disputes between them. Although

m~chpf the area had been abandoned in the 1820s after the raids by Hongi Hika pf Nga

Puhi, :both Ngati Tamatera and Ngai Te Rangi had "exercised certain rights of ownership".

The arbitrators recommended that Katikati Block "be surveyed and valued, and that the

amount of the purchase money be equally divided" between Ngai Te Rangi and Ngati

Tamatera. A postscript was added to this decision on 28 December: "It having been pointed

out that there are some burial grounds within the block, it has been agreed to reserve these

from sale" (AIHR 1867, A-20, p. 7; for details of evidence taken see DOSLI files 114 and

transcript in Stokes 1992, pp. 87-104). (

On 5 December 1864 Te Kou 0 Rehua, on behalf of Tawera, petitioned Parliament to return

to them "our land which has been taken by the hand of Ngaiterangi together with the Gover

nor" (AIHR 1867, A-20, p. 11). On 13 December, Frederick Weld wrote from the Colonial

Secretary's Office requesting Mackay and Clarke investigate the Tawera claims (ibid). This

seems:to have been done in conjunction with the inquiry in Auckland which had beguri on 12

December. In a report dated 22 June 1865 sentto the Native Minister, Clarke-and Mackay

concluded: "That the Tawera can only fairly claim those portions ofland of which they have

retained possession, or which have been returned to them by their former conquerors" (AIHR

1867, A -20, pp. 10-11). Tawera had claimed rights in Tauranga lands extending east to the

Waimapu River. However, it was to be some time before any of the Hauraki tribes received

formal recognition of their claims in the Katikati Te Puna lands.

c

37

4. Negotiations on the Katikati Te Puna Block 1866

There was little progress on surveys, or settling military settlers or allocating reserves on the

Katikati Te Puna "Purchase" through 1865, because officials feared attacks on surveyors by

"Hauhau rebels" in the Kaimai ranges and/or fighting between Hauraki and Tauranga peo

ple. There was also some argument between officials as to whether the Native Land Court

should have jurisdiction in investigating Tauranga lands under the Native Lands Act 1865.

Chief.Judge Fenton went as far as commissioning a survey ofKatikati Te Puna lands, but on

the advice of Mackay and Clarke to the Native Minister this was not proceeded with. The

proclamation bringing the Tauranga district under the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863,

issued on 18 May 1865, put these lands outside the jurisdiction of the Native Land Court.

There was also some correspondence over a Compensation Court provided for in the New

Zealand Settlements Act but no such Court sat on the Tauranga lands. The "due enquiry"

promised by Governor Grey and referred to in the proclamation of 18 May 1865 was carried

out entirely by Clarke and Mackay. No formal records appear to have been kept beyond

rough notes of "promises" to various individuals. The Katikati Te Puna "Purchase" had not

been completed when all these lands were included in the proclamation confiscating Tauranga

lands under the New Zealand Settlements Act. There were also private purchasers making

deals with local people, offering prices for coastal lands around the harbour well in excess of

the three shillings per acre of the Crown's offer for Katikati Te Puna.

On 26,February 1866 Defence Minister Colonel Haultain attended a meeting at Tauranga to

consid~ land matters. The brief notes of proceedings indicate that there was. a. good deal of

confusion over just what lands were to be given up as confiscated by the Crown and the

terms of the Katikati Te Puna "Purchase". Colonel Haultain stated it was time to settle the

terms agreed at the time of surrender in August 1864: