Investigation of a Romano-British Rural Ritual in Bedford, England

-

Upload

u-bordeaux1 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Investigation of a Romano-British Rural Ritual in Bedford, England

Journal of Archaeological Science (2000) 27, 241–254doi:10.1006/jasc.1999.0451, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on

Investigation of a Romano-British Rural Ritual in Bedford,England

A. Boylston, C. J. Knusel and C. A. Roberts

University of Bradford, Department of Archaeological Sciences, Bradford, BD7 IDP, U.K.

M. Dawson*

Bedfordshire County Archaeology Service, U.K.

(Received 9 November 1998, revised manuscript accepted 26 March 1999)

The Romano-British cemetery at Kempston, a suburb of Bedford, was excavated in 1992 by Bedfordshire CountyArchaeology Service and revealed 12 individuals who had been decapitated and 12 who were placed in the proneposition. These practices are a regular feature of internments in rural and a few urban cemeteries dating to the lateRoman period in a well-defined area of central England. The osteological findings are discussed and placed in thecontext of more widespread Iron Age customs. � 2000 Academic Press

Keywords: DECAPITATION, PRONE BURIAL, RITUAL.

Introduction

D ecapitation is a recognized part of burial treat-ment in rural burial grounds during the lateRomano-British period. Harman, Molleson &

Price (1981) documented over 70 burial grounds wheresuch treatments were practised and found that, inmany of these, prone burials were also a regularoccurrence, distinguishing these people from otherswithin their social group. The location of these sitescovers a wide swath of lowland England from Dorsetin the south-west to the Wash in the north-east. Thereare also occasional urban sites where decapitatedburials have been found, such as at Lankhills,Winchester (Clarke, 1979), Poundbury, Dorchester(Farwell & Molleson, 1993) and Cirencester, Wiltshire(Wells, 1982). Similar customs are seen in early Anglo-Saxon burial grounds such as Walkington Wold,East Yorkshire (Bartlett & Mackey, 1973), but thepractices are neither as common nor as uniform.During the third and fourth centuries there are afew standard locations for the head in relation to theinfra-cranial skeleton, such as beside or between thefemora and tibiae. Philpott (1991) studied the demog-raphy of those burials which date to the Romano-British period. He noted that they reflect the age andsex profile of the rest of the burials excavated sincedecapitated individuals are of both sexes and all ages,

2410305–4403/00/030241+14 $35.00/0

although infants are rare. In Philpott’s opinion, thisfact militates against this treatment being restricted tosociety’s outcasts. Since the term ‘‘outcast’’ differs withsocial mores and cultural practices, though, one canonly say that the individuals so treated are interredin proximity to others who had not received thistreatment.

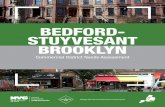

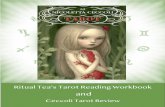

In 1992 during excavations carried out in the courseof constructing the Bedford Southern Orbital Sewer, arural burial ground, Kempston, was discovered on theoutskirts of the town of Bedford (Figure 1) whichcontained both decapitated and prone burials (Dawsonforthcoming). Three of the eight phases of occupationof the site (phases 3, 4 and 5) included a burial groundwhich dated to the third and fourth centuries .Ninety-four graves were uncovered and these included88 inhumation burials, five cremation burials and oneempty grave cut. The burial ground was in operationduring the period of transition from the use of crema-tion to inhumation as the main method of disposal ofthe dead in the late Roman period. Twelve of the 92burials (13%) had been decapitated and four of thesegraves were situated within a ditched enclosure (Figure2), emphasizing their special nature. All these enclo-sures dated to the last phase of the burial ground(phase 5). Most individuals were placed in the graveface upwards and in the extended position, which wasthe norm at this period. However, children were buriedin a crouched position and 12 individuals were facedownward, i.e. in a prone position.

*Current address: Samuel Rose, Cottage Farm, Sywell,Northamptonshire, NN6 0BJ, U.K.

� 2000 Academic Press

242 A. Boylston et al.

AMPTHILL

N

PETERBOROUGH

NORTHAMPTON

BEDFORDSHIRE

BEDFORD

LUTON

ST ALBANS

40 km0

FLITWICK

RUXOX

ASTON WELL VILLA

SHILLINGTON

3 km0

KEMPSTON

GOLD LANEBEDFORD

Figure 1. Map showing position of Kempston in relation to Bedford and surrounding area. (Courtesy of Bedfordshire County ArchaeologyService.)

Investigation of a Romano-British Rural Ritual in Bedford, England 243

Figure 2. Illustration of ritual enclosure surrounding one of the graves (Inhumation 14). (Courtesy of Bedfordshire County ArchaeologyService.)

0Subadult

12

Nu

mbe

r of

indi

vidu

als

2

4

6

8

10

Young adult Young/middle adult Middle adult Mature adult Adult

Indeterminate

?Female

Female

?Male

Male

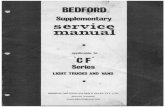

Figure 3. Demography of the burials (see p. 247 for age categories).

Materials and Methods

Upon osteological examination, it was possible toidentify a minimum of 92 individuals. They include 48males or probable males, 29 females or probablefemales, 4 individuals of indeterminate sex and 11

juveniles (less than 18 years of age); one of the adoles-cents could be identified as female since her pelvicbones, which fuse at an earlier age in females, hadfused. The sex profile of the burial ground (which wasdetermined by methods described in Bass, 1987), there-fore, reflected a pattern often seen in Romano-British

244 A. Boylston et al.

burial grounds: there are almost twice as manymales as females and a smaller number of childrenthan would be expected in a pre-industrial population(Figure 3). At Trentholme Drive in York (Warwick,1968) and Cirencester (Wells, 1982), for example, themale:female ratio was similarly distorted. Age estima-tion was undertaken by methods described in Ubelaker(1989) and again the results were different from thoseseen in a rural cemetery dating to the medieval period,such as Raunds, Northamptonshire (Boddington,1987), owing to the lack of women and children atKempston.

The burials were unusually well preserved; 50% ofthem falling into the good or excellent categories(Table 1), indicating that over 75% of the burial wasavailable for observation and that the bone itself wasin good condition. Since the degree of preservationdetermines how much information can be gained froma study of the human remains, this was a very import-ant factor in enabling a comprehensive study of thehead and neck region to be undertaken. Five of the 92

bone assemblages were too scanty to be included inTable 1.

Average stature was very similar to that calculatedfor other Romano-British burial ground populations,although the range was quite wide (Warwick, 1968;Wells, 1982). The males averaged 170 cm in height witha range of 155–182 cm and the females 160·4 cm,ranging from 151·3–177·2 cm suggesting that this wasnot a specially selected group of individuals.

Decapitation was recognized by macroscopic exami-nation of the cervical vertebrae with the assistance ofa hand-lens. Perimortal trauma was indicated by cutmarks on the vertebrae with polishing of the bonesurface (Wenham, 1989) and sometimes also bysplitting of the lamina of the neural arch. Owing topost-mortem destruction of the affected vertebrae,evidence for decapitation was indicated only by theposition of the skull in the grave in some individuals.

Results

Table 1. Preservation

Grade Number %

1 (excellent) 13 152 (good) 30 353 (fair) 19 224 (poor) 14 165 (very poor) 11 12

Table 2. Decapitation

Inhno Sex Position of head Evidence for decapitation

1 Female Below feet, facing north-east Six cut marks on anterior aspect of axis and transverse split through vertebralbody and neural arch

3 Female Below ankles/feet, face down Oblique slice through fourth cervical vertebra from the front, right to left,which has removed left apophyseal facets

5 Female Head and upper five vertebraebelow feet

Possible slice through antero-inferior aspect of fifth cervical vertebra from thefront (margin rather irregular)

6 Male Below feet, facing south-west Oblique slice through fifth cervical vertebra (inferior aspect) from thefront-right to left; shock has fractured neural arch; some splitting of rightlamina superiorly also

14 ? Male Between knees, facing towards head All vertebrae have disintegrated20 Male Between tibiae Post-mortem. ? cut nicked inferior aspect of C3. Part of fourth cervical

vertebra missing33 Male North of right tibia, facing north Cut probably made between third and fourth cervical vertebrae. Only

fragments remain. Left lamina of C4 is split38 Adult Mandible only found, between

femoraPost-mortem. Only a small fragment of third cervical vertebra remains.Possible oblique slice through vertebral body but break is irregular

51 Subadult North-west of tibiae, facingsouth-east

Post-mortem. Fragmentation of third cervical vertebra but no cut marks

57 Male Found in situ Cut from the front between fifth and sixth cervical vertebrae; at least two cutsfrom both left and right with a sharp weapon; flange on neural arch

72 Female Above feet, face down Cut marks on third cervical vertebra (inferior aspect); flange indicates theywere made from left to right

77 Male Between tibiae facing south-eastwith all cervical vertebrae

Cut marks on seventh cervical vertebra (superior and inferior aspects) madefrom left to right also cutting right clavicle

Decapitation

The 12 decapitated individuals included five males, oneprobable male, four females, one adult of indetermi-nate sex and one child (Table 2). In all these instances,apart from one (Inh 57), the head was placed near thetibiae or feet of the burial. Five of the 12 victims ofdecapitation showed definite evidence of cut marks onthe cervical vertebrae; one possessed an oblique slicethrough the fifth cervical vertebra with no evidenceof polishing and in one case all the vertebrae had

Investigation of a Romano-British Rural Ritual in Bedford, England 245

Figure 4. (a) and (b) Anterior and inferior aspects of axis vertebra showing cut through the vertebral body with splitting of the neural arches.

disintegrated and were unavailable for study. Theother five showed only post-mortem degradation andfragmentation of the vertebrae in the position wherethe neck had been severed. Some of the individualswith clear evidence of cut marks had been decapitatedeither just below the cranium (Inh 1), at the level of the

axis vertebra, or near the shoulders (Inh 57 and Inh77), at the level of the 6th or 7th cervical vertebrarespectively. In the group showing only postmortemdestruction, it appeared to be the third and fourthcervical vertebrae which were affected, as reported byClarke (1979) at Lankhills. Three individuals (Inhs 20,

246 A. Boylston et al.

Figure 5. Fifth and sixth cervical vertebrae of Inhumation 57 showing cut marks on vertebrae.

33 and 57) also had cut marks on the mandible(Marshall, 1999). In the last case (Inh 57) the mandiblehad been split in two. Decapitation is likely to be mostefficient when carried out at the level of the fourthcervical vertebra or below as cuts in this region avoidimpacting the gonial angle of the mandible and hyoidbone (Williams, 1995, p. 516).

There were six cut marks on the axis vertebra of ayoung woman (Inh 1) whose grave was situated withinan enclosure at the eastern end of the burial ground.The vertebra had been sliced from front to back(antero-posteriorly) so that the neural arch was splittransversely (Figure 4(a) & (b) and the third and fourthcervical vertebrae destroyed. The appearance of theaxis vertebra was very similar to that described byMcKinley (1993) in a decapitation from Baldock,Hertfordshire. The cuts on the fifth cervical vertebra ofInh 6 also came from the front of the neck andtransected the vertebral body diagonally from right toleft. There was a further possible cut on the upper partof the same vertebra which had split the lamina.

Inhumation 57 showed the most unusual form ofdecapitation. The superior surface of the sixth cervicalvertebral body and articular facets had been removedby a sharp weapon with at least two slices from rightand left, one of which had cut the right side of the fifthcervical vertebra obliquely. The cut from the right hadhit the more dense bone of the spinous process (Figure5). From the position of the burial, it was impossible tosay that this individual had been completely decapi-tated since his head was in its normal alignment, a

situation described by Wells (1982) in six burials fromCirencester. Inhumation 72, an elderly female, hadprobable cut marks on the inferior aspect of her thirdcervical vertebra, which also displayed a flange suggest-ing that the cuts had been made from left to right. Thefinal case, an elderly male (Inh 77) demonstrated cutmarks on the superior aspect of the seventh cervicalvertebra which had sliced through the neck with suchviolence from left to right that the weapon had also cutinto the right clavicle in the mid-shaft region (Figure6). There was also an oblique slice through the antero-inferior aspect of the vertebral body.

Where the cut marks have a polished appearance,the bone must have contained the same amount ofcollagen that it did in life (Wenham, 1989) and, there-fore, decapitation—if not the cause of death—wascarried out immediately after it had occurred. Splittingof the laminae also indicates that the musculature andligaments were present and intact. Certainly most, ifnot all, decapitations took place with the victim in asupine position from the front.

The demography of the burials shows that bothsexes were represented and that no particular agegroup was favoured above any other: 14·5% of males,13·7% of females and 9·1% of children were subjectedto this treatment at Kempston (Table 3).

An examination of the phasing of the decapitatedburials shows that three took place during the earliestphase of the burial ground (mid third to early fourthcentury AD), three were made during phase 4 (early tomid fourth century) and six during the last phase

Investigation of a Romano-British Rural Ritual in Bedford, England 247

(mid-to late fourth century); the last group are situatedperipherally within enclosures. Therefore, decapitationoccurred throughout the duration of the burialground’s use, although it was more common in thefinal phase.

Prone burialTwelve inhumations at Kempston did not conform tothe customary (supine) burial position. These individ-uals were buried face down with their lower extremitieseither flexed or extended, but in only one case wasdecapitation associated with prone burial. The demo-graphic pattern of those placed in the prone positionwas rather different from that of the decapitations.Although the sex ratios were almost equal, half theseburials were those of mature adults aged over 45 years;other age groups were only represented by one individ-ual each (Table 4). Three of these burials took place in

the mid third to early fourth centuries , seven duringthe early to mid fourth century and only two in thefinal phase of the burial ground, namely the mid-to-latefourth century, which is the period when decapitationwas most frequently undertaken.

Figure 6. Seventh cervical vertebra with cut marks on superior aspect and right clavicle showing cut marks anteriorly.

Table 3. Age and sex of decapitation burials

Age Category Male ? Male Female ? Female Indeterminate

Juvenile 1Young adult (18–25) 2Young/middle adult (26–35) 2 1Middle adult (36–45) 2 1 1Mature adult (46 and over) 2 1Total 6 1 4 0 2

Grave furnitureThere is a considerable contrast between the decapi-tated and prone burials with regard to their associatedgrave furniture. Five of the decapitated burials werefurnished with coffins (Inhs 1, 3, 5, 6 and 14); whereas,one of the prone burials was thus provided. Grave 6was particularly elaborate and contained 35 coffinnails, some hinge fragments, a coin dating to 367–375 and a jar. The graves of those who had beeninterred face downwards were simple with no gravegoods accompanying the burial. Personal adornments,such as bracelets and beads, were only found with

248 A. Boylston et al.

children, and the decapitated child (burial 51) wasno exception, with a copper alloy cable bracelet ac-companying the burial. Other grave goods included abeaker and pillowstone for the decapitated head withburial 20, a whetstone in the fill of grave 57, a copperalloy needle with burial 72 and part of a red sandstonesaddlequern with Inh 77.

Table 4. Age and sex of individuals buried in the prone position

Skeletonnumber Sex Age Burial position

2 Male Mature adult Flexed (inboundary ditch)

6 Male Young/middle adult Extended25 Female Mature adult Extended50 Subadult Adolescent Extended60 Female Middle adult Extended61 Male Young adult Extended62 Female Mature adult Flexed66 ? Female Mature adult Extended67 Male Young/middle adult Extended82 Male Mature adult Flexed84 ? Female Adult Extended85 Male Mature adult Extended

DiscussionEthnohistoric and historic texts provide manyexamples of social reasons that motivate decapitationacross cultures and from many periods. In order todistinguish one from another it is necessary to combinethe physical evidence left by the act with the archaeo-logical contexts in which it occurs. Decapitation couldoccur under the following circumstances: (1) as a formof corporal punishment in which an individual isexecuted by severing the head from the body throughthe use of an edged weapon; (2) as a consequence ofarmed confrontation in which the neck becomes atarget in order to disable or kill a foe; (3) as a trophy ofarmed confrontation; (4) as a form of relic collection orveneration; (5) as a result of bloodletting in which thehead is removed in order to collect the body’s bloodsupply; (6) as a result of a mismanaged hanging; (7) asa result of a figurative association between the headand a quality or qualities considered to be associatedwith it. Each of these will be considered in turn.

Perhaps among the most familiar and recentexamples of decapitation comes as a consequence ofexecution. During the Mediaeval and early modernperiod, this form of corporal punishment was fre-quently employed for those deemed to be traitorsagainst the state. During the Mediaeval period, execu-tion by beheading was performed with the individualeither kneeling or standing upright and appears to havebeen associated with ignominy (Daniell, 1997). One ofthe earliest examples of this type of punishment toinclude a block involved the treasonous Duke of

Suffolk who was beheaded in 1450 for his part inpassing information to the French. It took the execu-tioner half a dozen strokes with a rusty sword toremove the hapless nobleman’s head which was thendisplayed on a pole next to his unburied body on thebeach at Dover (Gillingham, 1990). Decapitation wasalso practised by the Romans as a form of punishment.The six decapitated burials at Cirencester appear tohave been the victims of an execution since all but twoof them had been decapitated from behind (Wells,1982). Others are found in 11th-century Viking periodDenmark. Two decapitated burials were found atKalmergarden and another from the same period atLehre; in both cases the head was placed between thefemora and the decapitation was carried out frombehind in an execution-like manner (Bennike, 1985).

Because the individuals at Kempston possess incisedcutmarks on the anterior aspects of the cervical ver-tebrae, this type of execution does not seem to havebeen the motivation. Beheading would be expectedto produce traumatic lesions affecting the posterioraspects of the vertebrae with chop marks deliveredfrom the posterior to the anterior. The physicalevidence from Kempston appears to rule out thisinterpretation. Moreover, that these individuals wereassociated with well-appointed grave furniture wouldseem to suggest that these were not especially ignom-inious burials; these contrast with those contemporaryindividuals found in a prone position and withoutgrave inclusions found at this and other sites during theperiod. Like the adults, the decapitated child, burial 51,was treated as other children at the site. Thus bothphysical and archaeological contextual evidence rulesout execution as a motivation.

One might expect to encounter combat-relatedtrauma throughout the Romano-British period as aconsequence of warfare. Normally, decapitation insuch a situation involves evidence of a chop mark (notan incised or cut mark), indicating that a heavyweapon was involved, coming from one side of theneck or the other (depending on the hand preference ofthe assailant) with the weight of the weapon and forceof the blow creating a fracture that then removes thehead. Usually in such instances one would expect tohave other evidence of weapon trauma to another partof the body, often in the form of defence injuries to theforearms and hands as the individual attempted toward off the blow. Although these injuries are lackingin the majority of individuals from Kempston, threeadult males, Inhs 20, 33, and 57, show evidence ofcutmarks on the mandible, and Inh 77, an elderly adultmale, has a cut mark on the right clavicle. The presenceof cutmarks on the anterior aspects of the vertebrae inthe majority of individuals at Kempston and the ab-sence of cut and chop marks and injuries to other partsof the body would seem to preclude this possibility forall of these individuals. The mandibular cutmarks onsome of these individuals may be the result of inciden-tal contact made with the lower jaw. These are, again,

Investigation of a Romano-British Rural Ritual in Bedford, England 249

incised marks and not chop marks, however, a patternthat does not fit that normally seen in cases in whichinjuries are received in armed combat.

Combat-related trauma is most often associatedwith males (see, for example, Wenham, 1989; Stroud &Kemp, 1993; Boylston et al. 1997), a pattern that couldarguably account for the appearance of Inhs 6, 20, 33,57 and 77 as they are all males. The presence of thehead in proper anatomical position in burial 57, theonly instance at Kempston, recalls the situation ofsome of the individuals Wells (1982) described atCirencester. This may suggest that the head was notentirely severed at the time of burial. The cutmark tothe clavicle of Inh 77, which would have been producedby a powerful blow, would suggest that this individualdied as a result of armed conflict. The cutmarks to themandibulae are, again, of an incised variety that arenot typical of those produced by a heavy weapon. Themixed demographic profile of the individuals fromKempston and those of contemporary individuals simi-larly treated, including both females and children,would also appear to preclude the interpretation ofcombat-related death for the majority of the individ-uals at Kempston. Massacres, which often includefemales and children, are usually found as mass graves(see, for example, Frayer, 1991; Zimmerman & Bradley1993). The single interment pattern and lack of otherinjuries to the infracranial skeleton in the majority ofindividuals found at Kempston contrasts with thisexpected pattern.

A near-contemporary example of the removal of thehead at the time of burial is described at Ribemont,Departement de la Somme, France (Brunaux, 1996),where a pile of headless corpses were excavated whichwere once apparently placed standing-up within anabove-ground structure dating between the third andfirst century . These are thought to have been thedecapitated bodies of warriors since all 65 were malesbetween the ages of 16 and 40 and were accompaniedby parts of 200 weapons of various types. Again, unlikethe Kempston individuals, many of these individuals’infracranial skeletons show extensive evidence of injurysustained at or about the time of death. They are alsofound in a mass grave. Thus near-contemporary con-texts provide evidence of what appears to have beenpunitive decapitation, but the archaeological context isdifferent from that noted at Kempston.

Ethnographic examples of special treatment of thehead after death (e.g. postmortem) are quite common.Among the Dayak of Borneo this part of the body isregarded as a trophy (Needham, 1976), as it appears tohave been in the European Iron Age. Postmortemdecapitation before burial may have its roots in ideasprevalent in the Iron Age when heads were oftendissociated from the rest of the body and publiclydisplayed in some form (Green, 1998). Such practicesare known from the writings of Diodorus Siculus(29,4–5): ‘‘They cut off the heads of enemies slain inbattle and attach them to the necks of their horses . . .

and they nail up these first fruits upon their houses . . .They embalm in cedar-oil the heads of the mostdistinguished enemies and preserve them carefully in achest, and display them with pride to strangers, sayingthat for this head, one of their ancestors, or his father,or the man himself refused the offer of a large sum ofmoney. They say that some of them boast that theyrefuse the weight of the head in gold’’ (Tierney, 1960).

In all of these instances heads, or defleshed craniaand mandibulae, were collected in order to displaythem. The fact that the crania at Kempston and otherRomano-British sites were replaced in the grave andwere not separated from the infracranial skeleton sug-gests that display was not a motivating factor in theseinstances. Moreover, there is no evidence of damage tothe foramen magnum (Boylston, Norton & Roberts,1995) nor evidence for any form of attachment such asthe perforations made by nails in the crania fromEntremont (Benoıt, 1975) found in instances whenheads have been displayed. Rather, the placement ofthe severed elements towards the foot-end of thegrave suggests a deliberate deposition according to apreconceived plan with the elements fully fleshed, orwith at least the ligaments of the vertebral column stilladhering and keeping the associated cervical vertebraein articulation. Thus the Kempston decapitations donot seem to have been carried out for the purposes ofdisplay.

Iron Age peoples placed great significance on thecult of the human head, as demonstrated by theMabinogion (Stone, 1989), where the legend of Brancontains a passage in which the hero encouraged hisfollowers to take his disembodied head to Britain withthem. The motivation here appears to be one moreakin to veneration rather than trophy acquisition. Thecollection and retention of body parts as relics wascommon practice in the High and Late Mediaevalperiods when certain parts were retained after theremainder had been interred. Particular importancewas ascribed to the cranium and long bones, whichwere collected from disturbed burials in crowdedchurchyards and compactly stored in charnel houses,which became repositories for defleshed remains(Roberts, 1982). Little explanation for these practicescan be found in documentary records, so the reasoningbehind such selective storage is obscure. It may thus bea perfunctory practice designed to accommodate localneeds or one that relates to an older, unorthodoxtradition.

The non-doctrinal practice of collecting the de-fleshed bones of those who died faraway and saints’relics—as a means both to ensure the resurrection ofthe faithful and to enhance the prestige of ecclesiasticalfoundations—became so common that, at the turn ofthe 14th century, Pope Boniface VIII repeatedly issuedBulls prohibiting the boiling of the bodies of thedeceased in order to retrieve the bones for transport toa favoured institution. These proclamations were gen-erally ignored such that by the 15th century separate

250 A. Boylston et al.

burial places for the head and heart were carefullyselected to reflect the interests of the individual duringlife (Brown, 1981). The entrails, however, were interredin the place of death, likely as a means by which tostave off decomposition. Similar motivations appear tohave influenced earlier mediaeval practices. Simmer(1982) reported several cases of decapitation during theMerovingian period in eastern France. He attributedthis practice to ‘‘La veneration du crane et l’exaltationde la tete a l’epoque celtique . . .’’, perhaps alluding tothe survival of a pre-Roman practice.

Such practices are also evident in the display ofhuman crania in niches within sanctuaries at IronAge oppida such as Roquepertuse and Entremont,Provence, France in the third century (Benoıt,1975). These are considered to have been sacred placeswhere the magical powers of the spirits were harnessedto ensure the protection of the people as a terrifyingwarning to potential enemies. Both Roquepertuse andEntremont were subjugated by the Romans in the year123 and the sanctuary at Entremont destroyed. Thisdesecration suggests that the destruction was punitiveand directed at debasement of the practices of a localcult. Benoıt (1975) argues that cranial display in associ-ation with statuary of individuals holding heads alsoattests to the existence of an animistic belief systemthat viewed casualties of war as ancestral heroes. Thisreasoning would suggest that the crania were collectedbecause they were those of ancestors, rather than thoseof vanquished foes, although these need not be exclu-sive categories. As there is no evidence to suggest thatthe skulls from Kempston were retained after decapi-tation, veneration of the deceased requiring the physi-cal presence of body parts does not appear to be themotivating factor in this instance.

Both humans and animals may act in sacrificialbloodletting and appear to have been participants inthese rites in the Iron Age (see Green, 1998). In order tocarry out rites involving bloodletting the throat andcarotid arteries and jugular veins are normally thetarget of such treatment. These structures can be sev-ered just below and behind the ear (e.g. at the pressurepoint), but would not require removing the head orany contact with the underlying vertebrae. Given thelocation of the pressure point, one might expect cut-mark evidence in the region of the mastoid process, if atall. Importantly, near-contemporary animal sacrificesappear to have been performed using a blow to thehead. Although Meniel (1992, p. 86) believes thatanimals like some of the dogs found at Vertault, Coted’Or, Burgundy (first century to the first century )may have been bled, she notes that there is no physicalevidence left on the bones to support this hypothesis.Since animal remains did not have their heads removedin this process, one would have to invoke an over-exuberant form of bloodletting to explain the cut-marks, sometimes multiple, on the Kempstonindividuals. It is unlikely, then, that a bloodlettingritual was responsible for these decapitations.

In recent accounts of judicial hangings—that is,those employing a drop—there are occasional refer-ences to decapitations caused by inappropriately man-aged hangings which resulted in decapitation (James &Nasmyth-Jones, 1992). Although the use of the drop isnot recorded before the 19th century (Sternbach &Sumchai, 1989), one should not assume that its firstwritten mention necessarily reflects the first time such amethod was employed. There are Roman examples ofsub-aural (with the knot located beneath the ear)hanging, presumably employing a drop (Wood-Jones,1908). Use of the drop more recently is intended tobreak the individual’s neck through either a cervicaldislocation or a fracture-dislocation (James &Nasmyth-Jones, 1992; Waldron, 1996). Skeletalmarkers indicative of hanging are rarely encountered inthe archaeological record and modern scenarios iden-tifying these processes rely heavily on the appearanceof the soft-tissue in the region of the neck. The mostfrequent skeletal lesion resulting from hanging is afracture through the pedicle in an A-P direction orthrough the pedicle and transverse process across thesuperior articular process of the axis vertebra in aminority of cases (James & Nasmyth-Jones, 1992).No such injuries were encountered in the Kempstonremains. This possibility, then, cannot account for thedecapitations noted.

Turner (1969) draws attention to the ‘‘conventional-ized and obligatory’’ nature of ritual activities thatreveal the values of the society in which they are found.These regularities can help to understand the ethos thatdetermines ritual action. There are such regularities atKempston. With the exception of Inh 77, the majorityof the individuals from Kempston have no physicalsigns of violence or disease other than cutmarks to theneck region, the anterior aspects of the cervical ver-tebrae and mandibulae. These cutmarks are associatedwith what would have been skulls, articulated craniaand mandibulae, with some cervical vertebrae also stillarticulated which were placed at the foot-end of thegrave. It appears, then, that the majority died of somedisease or disorder of the soft tissue. Normally suchdiseases—those that do not affect bone—are the resultof an acute illness or accident, one that kills its victimrelatively rapidly and perhaps with few manifest symp-toms. The absence of defence injuries and other injuriessuggests that these individuals were either drugged,otherwise incapacitated, or already dead when theprocedure was carried out. The orientation and posi-tion of the cutmarks would suggest that the throat wascut through to the vertebrae, which were then prisedapart to remove the head.

Knight (1991, p. 214) records the tell-tale signs of thecut throat: ‘‘The classic description of the cut throat isof the incisions starting high on the left side of the neckbelow the angle of the jaw, which pass obliquely acrossthe front of the neck to end at a lower level onthe right.’’ This is similar to the pattern noted atKempston. The type of decapitation noted, then,

Investigation of a Romano-British Rural Ritual in Bedford, England 251

would have required that the head was held in exten-sion (i.e. pulled back) to achieve access to the greatestarea of the neck. This is most easily achieved with thedecapitator either on top of a prostrate individual orstanding behind him/her. This position also allows thedecapitator to avoid hitting the mandible and hyoid asthese structures are held out of the way with the headextended. Due to the increased power of supinationlent by M. biceps brachii with the elbow flexed inconjunction with the shoulder and upper limb mediallyrotated, the cut will be deepest on the victim’s neckopposite to the hand holding the blade and moreshallow as the blade is drawn across the throat and themedial rotators of the shoulder lose their advantage(the same situation obtains in shaving the face). Oneshould thus expect deeper incisions on the left side ofa decapitated persons’ neck than on the right if thedecapitator is right-handed and performing the oper-ation from behind. The same holds true for a right-hander operating from the front on either a prostrateor standing individual with the head held in extensionin which a slashing motion would be indicated. Theopposite pertains if the decapitator is left-handed andoperating from behind—the cut will run from left toright and it will be deepest on the right side of theindividual’s neck. The lowermost cervical vertebraebeginning from C3 are the most often affected in theKempston individuals, although the multiple cutmarksof Inh 1, an adult female, are similar to those reportedfor a soldier from Fort William Henry in New York,who had been decapitated from behind left to rightwith either an axe or a knife in 1757, leaving fourcutmarks in the region of the odontoid process (Liston& Baker, 1996). Unlike this individual, though, Inh 1had no other injuries to the infracranial skeleton.

There appears to be some regularity in the treatmentof these individuals in that in the majority only theneck area was targeted. Of the decapitated individualsfound at Kempston retaining the cervical vertebrae in acomplete enough state to judge the direction fromwhich cuts were delivered, Inh 3 (an adult female), and6 (an adult male) reveal evidence of the cut being madefrom right to left; whereas, Inh 72 and 77 present withthe opposite pattern—that is, cuts from left to right. Inthe case of 57 cuts came from both right and left sidesof the neck. There are thus different patterns presentthat may relate to different positions taken by thedecapitator in relation to the decapitated.

From the foregoing it is clear that no single motiva-tion can account for all of the decapitations in evidenceat Kempston. Each possibility is discounted either onthe basis of the physical evidence or by that of thearchaeological context in which these burials occur orby both. In the absence of documentation from theperiod relating to a practice of perimortem decapi-tation, ethnographic and mythic sources may suggestpossible motivations for a treatment that appears tohave eluded contemporary chroniclers. The final possi-bility posits that decapitation was carried out as a result

of a figurative association between the head and aquality or qualities considered to be associated with it.

A figurative association is suggested by the prevalentview that the head is the seat of wisdom. This associ-ation is found in a number of myths from NorthernEurope. Odin recovered the head of the emissary of theAesir, Mimir, who was killed out of vengeance byhaving his head hacked off by the Vanir. The dis-embodied head was sent back to the Aesir and theirleader, Odin, who ‘‘. . . took Mimir’s head and cradledit. He [Odin] smeared it with herbs to preserve it, sothat it would never decay. And then the High One sangcharms over it and gave back to Mimir’s head thepower of speech. So its wisdom became Odin’swisdom—many truths unknown to any other being’’(Crossley-Holland, 1993, p. 8). Afterwards Odinplaced the head beneath the third root of Jotunheim inorder that it might guard over a spring, a drink fromwhich endowed wisdom (Odin had traded an eye fora single draft from this spring). In these instances,though, the decapitated head is preserved and retainedor, as in the case of Mimir, buried without the body, ascenario different from that observed at Kempston,where the head is placed in the grave.

Guarding or protecting is also indicated in the abovepassage, an attribute of the head implicated in otherinstances across Eurasia. Benoıt (1975, p. 258) writesthat: ‘‘The severed human head is the most ancienttalisman of mankind. Buried beneath the door-step ofa house, enclosed in the rampart, or carved on therampart of the fortress (as at les Baux, Tarragone,Albarez and Lugo in Celtiberia), it was intended tokeep malevolent powers at a distance and terrify theenemy, like the Gorgon head on the shield of Athena.’’The decapitated Chinese war-god Guandi appears in adream to a monk, demanding his head. Upon beingreminded by the monk that he decapitated manyothers, the warrior becomes a guardian and defenderof the Buddhist faith (Duara, 1988). Other individualsalso benefit from protection conferred by the head. TheVasyugan shaman enjoys the protection of the ‘‘spiritof the head’’ on ecstatic, trance-induced journeys(Eliade, 1964, p. 89). The dismembered head also playsa central role in the dreams that form part of the ritesof passage of the future ritualist among the Tungus ofSiberia. During an illness the initiate dreams that hisbody is cut to pieces, his blood consumed by evilspirits, the souls of dead shamans, who proceed tothrow his head into a cauldron, in which it is meltedwith the metal accoutrements that will later decoratehis ritual costume and symbolise his role as one able tocommunicate with ancestral and personal spirits in thespirit world (Eliade, 1964, pp. 43–44). The story ofBran, who Stone (1989) equates with the northerndeity Odin, is perhaps most germane to the presentdiscussion in that the story takes place in Britain andIreland. Bran’s head, like Mimir’s and Guandi’s, isconsidered a guardian. After a peripatetic journeylasting some eighty years, the head of Bran asks to be

252 A. Boylston et al.

interred in London in the ‘‘ ‘White Mount’ as aprotection against invasion’’ (Stone, 1989, p. 28).Decapitation, then, is associated with an individual’sbecoming a guardian or protector among a number ofrecent and ancient Eurasian cultures.

The effect of separating the head from the bodycould have been to disable the corpse in a society thatdid not see death as final, as in the case of the mythsdiscussed above. Diodorus Siculus (28, 5, cited inTierney, 1960) writes that: ‘‘. . . they are wont to bemoved by chance remarks to wordy disputes, and, aftera challenge, to fight in single combat, regarding theirlives as naught; for the belief of Pythagorus is strongamong them, that the souls of men are immortal, andthat after a definite number of years they live a secondlife when the soul passes to another body.’’ Theremoval of the head, then, may be a means by whichto effect this transference, either to prevent it and toassure that the soul remains in the place of burial orto prepare and permit the souls of such individuals torejoin the living at a future date. Both are possibilities.

At Kempston, the combination of at least one indi-vidual who may have been decapitated in armed con-flict with others who may have died under othercircumstances were perceived to be similar at thetime of interment. The pattern of the burials fromKempston provides evidence that the individuals con-cerned had been through a ritual process (a series ofprescribed rites) that included burial within the vicinityof enclosures, removal of the head and some associatedvertebrae with a bladed weapon—probably a knife inmost cases—and deposition of the severed portion inthe grave immediately prior to its filling. With theexception of Inh 57, whose head was in proper ana-tomical alignment, the head was placed at the foot-endof the grave, facing a variety of directions, perhaps as ifthey were intended to oversee from this position. Onlyin burial 72, an adult female, was the head placed in aface-down position, which may be a variant of theprone position recorded elsewhere on this and otherRomano-British sites. One way of interpreting thisgeneral similarity would be to suggest that all died as aresult of confrontation and the head was removed afterthe individual succumbed to an assailant. The motiva-tion may have been to exact revenge, as is the case withthe decapitation of Mimir. In order to re-unite thesevered head with the body some ritual sanction, asocial payment or exchange, financial or otherwise, hadto be made by survivors (cf. Ucko, 1969). That immor-tality is mentioned in the context of fighting may besignificant in the context of suspected battle casualtiesamong the Kempston individuals and the payment of a‘‘head-price’’ by Diodorus Siculus (above). It seemsodd, though, that the head would not be placed inanatomical position in such an instance.

Another possibility is that those who died suddenly,prematurely or unexpectedly of disease, disorder, oraccident were decapitated and resemble those decapi-tated in armed conflict. In some societies, the removal

of part of the body is considered to facilitate the entryof the soul into the underworld by putting an end tothe old life and destroying the unity of the body oreven disabling the corpse (Wright, 1988). AlthoughHirst (1985) argued that prone burial represented anattempt to inhibit the power of undesirable members ofthe community to return and disturb the living, thedecapitated individuals received mortuary treatmentlike others at Kempston, although the prone individ-uals at the site did not. This difference argues for thedistinctiveness (although not mutual exclusivity, seeHarman, Molleson & Price 1981 and Knusel, Janaway& King 1996) of these two burial rites.

Van Gennep (1960) observed that funeral rites be-come more complex when there are opposing views ofthe afterlife within a community. This would suggestthat individuals buried prone and those who weredecapitated were viewed in distinctive ways at death.The decapitated individuals were accorded funeraryrites—grave furniture and body positioning like that ofother burials at the site. However, as noted by Philpott(1991) decapitation with deposition of the skull atthe foot-end of the grave is mainly found in ruralburial grounds during the Romano-British period.When similar burials are found in urban situationsthey appear to be peripheral to other burials as atPoundbury 3 and Lankhills or found in unusual cir-cumstances, as is the case at Cirencester. This maysuggest that such individuals were excluded from themore common urban form of burial and, when in-cluded within an urban burial ground, they wereconsidered to be as peripheral as if had they beeninterred in a rural setting. Being located on the periph-ery or in a rural area might be related as well to thenotion that decapitated individuals could protect thedead and the living from transgression; they couldguard over them on the periphery like a sentinel. In thissense they would mark the boundary between theliving and the dead.

Bran was decapitated after having been wounded inthe foot by a poisoned spear. His head was removedby his own followers in order that it could be takenwith them. Given the reference to Bran’s and Mimir’sheads in protecting or guarding against some presumedtransgression, the intent could be as much to enable thedead individual to protect the living from transgressionfrom outside the community. Mimir was associatedwith wise advice and Bran with pleasant company,desirous personal qualities, useful to the living, whichwould indicate that such a treatment need not beconsidered punitive. In summary, there is some evi-dence to suggest that some decapitated or nearlydecapitated individuals were casualties of conflict andthat some others were considered similar enough to betreated in a similar manner. That such individualsappear to be interred with those who may have died asa result of armed combat may suggest that individualswho died suddenly of wounds received in battle oracutely from disease, disorder, or accident or even a

Investigation of a Romano-British Rural Ritual in Bedford, England 253

figurative or real poisoning were singled out for specialtreatment.

On the basis of present evidence, two hypothesesseem supported. The first would interpret some of theseindividuals as casualties of armed conflict. Decapi-tation was performed after having been previouslyimmobilized, as at Fort William Henry, related injuriesbeing obscured by preservation or affecting soft tissueonly and not the skeleton (Liston & Baker, 1996). If so,this would suggest that warfare was endemic—widelydispersed geographically and frequent—during the lateRomano-British and post-Roman periods in which theheads of men, women, and children were taken invengeance and to exact social retribution. This is apattern that is very old in Western Europe, dating backinto the Mesolithic (see Frayer, 1991). The otherpossibility—and again not necessarily mutuallyexclusive—is that, if those who died, suddenly, in oddcircumstances were treated in a similar manner, nomatter the cause, decapitation relates to a mortuaryrite directed at individual corpses in imitation of afigurative association between the head and an after-death existence or role. This practice may be a new onethat originated in the Roman period and carried oninto the post-Roman period, especially in rural areaswhere Romanization may not have been complete.This scenario appears especially apt for the situation inBritain, where Jones (1987) has argued that Romaniz-ation was largely an urban phenomenon, short-lived,and incompletely developed. If the latter is the case, weshould expect to see Iron Age precursors to the patternobserved at Kempston and elsewhere that wouldcomplement those found at Iron Age sites likeRibemont or Entremont. However, since the decapi-tated individuals are found amongst the burials ofothers and the treatment is variable in its physicalmanifestations (i.e. the manner of decapitation and theareas of the neck affected are different), this undocu-mented ritual likely represents one performed occa-sionally by and upon individuals who were removedfrom the strictures of urban concepts of life and deathin the Roman period.

AcknowledgementsThe excavation and postexcavation analysis wereundertaken by Bedfordshire County ArchaeologyService and funded by a grant from Anglian Water,for which we would like to express our gratitude. Theproject was monitored by Gifford’s of Chester. Theauthors would like to thank Ms Jean Brown whowas responsible for the photography and Dr KeithManchester and Professor Donald Ortner for assist-ance with the pathological diagnoses. Our gratitude isexpressed to other members of the laboratory staff, MrBrian Connell, Ms Mary Lewis, Ms Sharon Norton,Ms Francesca Boghi and Mr Christopher Stevens, whogave helpful advice during the recording of the burials.

The recording form was designed by Ms Sarah King ona model composed by Dr Charlotte Roberts. Dr CarolPalmer read the manuscript and made valuablecomments.

ReferencesBartlett, J. E. & Mackey, R. W. (1973). Excavations on Walkington

Wold 1967–1969. East Riding Archaeologist 1, 1–93.Bass, W. M. (1987). Human Osteology: A Laboratory and Fieldwork

Manual of the Human Skeleton. Columbia: Missouri Archaeologi-cal Society.

Bennike, P. (1985). Palaeopathology of Danish Skeletons: A Com-parative Study of Demography, Disease and Injury. Copenhagen:Akademisk Forlag.

Benoıt, F. (1975). The Celtic oppidum of Entremont, Provence. In(R. Bruce-Mitford, Ed) Recent Archaeological Excavations inEurope. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, pp. 227–259.

Bienert, H-D. (1991). Skull cult in the prehistoric Near East. Journalof Prehistoric Religion 5, 9–23.

Boddington, A. (1987). From bones to population: the problem ofnumbers. In (A. Boddington, A. N. Garland & R. C. Janaway,Eds) Death, Decay and Reconstruction: Approaches to Archaeologyand Forensic Science. Manchester: Manchester University Press,pp. 180–197.

Boylston, A., Norton, S. & Roberts, C. A. (1995). Ritual or Refuse?Late Bronze Age Mortuary Practices at Runnymede. Unpublishedbone report, Bradford University, Bradford, West Yorkshire,England.

Boylston, A., Holst, M., Coughlan, J., Novak, S., Sutherland, T. &Knusel, C. (1997). Recent excavations of a mass grave fromTowton. Yorkshire Medicine 9, 25–26.

Brown, E. A. R. (1981). Death and the human body in the laterMiddle Ages: the legislation of Boniface VIII on the division of thecorpse. Viator; Medieval and Renaissance Studies 12, 221–270.

Brunaux, J-L. (1996). Les Religions Gauloises: Rituels Celtiques de laGaule Independante. Paris: Editions Errance.

Clarke, G. (1979). The Roman Cemetery at Lankhills. Oxford: TheClarendon Press.

Crossley-Holland, K. (1980). The Penguin Book of Norse Myths.Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Cunliffe, B. (1979). The Celtic World. London: The Bodley Head.Daniell, C. (1997). Death and Burial in Medieval England. London:

Routledge.Dawson, M. (forthcoming). Archaeology in the Bedford Region.

Hadrian Books: British Archaeological Reports, British Series.Duara, T. (1988). Superscribing symbols: the myth of Guandi,

Chinese god of war. The Journal of Asian Studies 47, 778–795.Eliade, M. (1964). Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy.

(Translated by W. R. Trask). London: Arkana.Farwell, D. & Molleson, T. (1993). Poundbury. Vol. 2. The Cem-

eteries. Dorchester: Dorset Natural History and ArchaeologicalSociety Monograph series 11.

Frayer, D. W. (1991). Ofnet: evidence for violence in the EuropeanMesolithic. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, suppl 12,74.

Gillingham, J. (1990). The War of the Roses: Peace and Conflict inFifteenth Century England. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

Green, M. (1998). Humans as ritual victims in the later prehistory ofwestern Europe. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 17, 169–189.

Harman, M., Molleson, T. I. & Price, J. L. (1981). Burials, bodiesand beheadings in Romano-British and Anglo-Saxon cemeteries.Bulletin British Museum of Natural History (Geology) 35, 145–188.

Hirst, S. M. (1985). An Anglo-Saxon Inhumation Cemetery atSewerby, East Yorkshire. York: York University ArchaeologicalPublications, Vol. 4..

James, R. & Nasmyth-Jones, R. (1992). The occurrene of cervicalfractures in victims of judicial hanging. Forensic Science Inter-national 54, 81–91.

254 A. Boylston et al.

Jones, R. F. J. (1987). A false start? Roman urbanization of westernEurope. World Archaeology 19, 47–57.

Knight, B. (1991). Forensic Pathology. New York: Oxford UniversityPress.

Knusel, C. J., Janaway, R. C. & King, S. E. (1996). Death, decay,and ritual reconstruction: archaeological evidence of cadavericspasm. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 15, 121–128.

Liston, M. A. & Baker, B. J. (1996). Reconstructing the massacre atFort William Henry, New York. International Journal of Osteo-archaeology 6, 28–41.

Marshall, C. (1999) The Romano-British Decapitation Ritual. M.Sc.dissertation, University of Bradford, Bradford, West Yorkshire,England.

Matthews, C. L. (1981). A Romano-British cemetery at Dunstable.Bedfordshire Archaeology Journal 15, 1–73.

McKinley, J. I. (1993). A decapitation from the Romano-Britishcemetery at Baldock, Hertfordshire. International Journal ofOsteoarchaeology 3, 41–44.

Meniel, P. (1992). Les Sacrifices d’Animaux chez les Gaulois. Paris:Editions Errance.

Needham, R. (1976). Skulls and causality. Man 11, 71–88.Owsley, D. W. (1994). Warfare in coalescent tradition populations of

the Northern Plains. In (D. W. Owsley & R. L. Jantz, Eds).Skeletal Biology in the Great Plains: Migration, Warfare, Health,and Subsistence. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press,pp. 333–343.

Philpott, R. (1991). Burial Practices in Roman Britain: a Surveyof Grave Treatment and Furnishing A. D. 43–410. TempusReparatum, British Archaeological Reports, British Series, 219.

Roberts, C. A. (1982). Analysis of some human femora from aMedieval charnel house at Rothwell parish church, Northampton-shire, England. Ossa 9, 119–134.

Simmer, A. (1982). Le prelevement des cranes dans l’est de la Francea l’epoque merovingienne. Archeologie Medievale 12, 35–49.

Sternbach, G. & Sumchai, A. P. (1989). Frederic Wood-Jones: theideal lesion produced by hanging. The Journal of EmergencyMedicine 7, 517–520.

Stone, A. (1989). Bran, Odin, and the Fisher King: Norse traditionand the Grail legends. Folklore 100, 25–38.

Stroud, G & Kemp, R. L. (1993). Cemeteries of St. Andrew,Fishergate. The Archaeology of York: The Medieval Cemeteries12/2, York: Council for British Archaeology for York Archaeo-logical Trust.

Tierney, J. J. (1960). The Celtic ethnography of Posidonius. Proceed-ings of the Royal Irish Academy 60, 189–275.

Turner, V. (1969). The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-structure.New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Ubelaker, D. H. (1989). Human Skeletal Remains: Excavation,Analysis, Interpretation. Washington: Taraxacum Press 2nd edn.

Ucko, P. (1969). Ethnography and archaeological interpretation offunerary remains. World Archaeology 1, 262–280.

van Gennep, A. (1960). The Rites of Passage. London: Routledgeand Kegan Paul.

Waldron, T. (1996). Legalized trauma. International Journal ofOsteoarchaeology 6, 114–118.

Warwick, R. (1968). The skeletal remains. In (L. P. Wenham, Ed.)The Romano-British Cemetery at Trentholme Drive, York. London:Ministry of Public Buildings and Works: Archaeological Reports,no. 5., pp. 113–176.

Wells, C. (1982). The human burials. In (A. McWhirr, L. Viner &C. Wells, Eds) Romano-British Cemeteries at Cirencester.Cirencester: Cirencester Excavations vol. 2. Corinium Museum,pp. 135–202.

Wenham, S. J. (1989). Anatomical interpretations of Anglo-Saxonweapon injuries. In (S. C. Hawkes, Ed.) Weapons and Warfare inAnglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Oxford University Committee forArchaeology Monograph, no. 21., pp. 123–139.

Williams, P. (1995). Gray’s Anatomy. 38th edition. New York:Churchill Livingstone.

Wood-Jones, F. (1908). The examination of the bodies of 100 menexecuted in Nubia in Roman times. British Medical Journal i, 736.

Wright, G. R. H. (1988). The severed head in earliest Neolithic times.J. Prehistoric Religion 2, 51–56.

Zimmerman, L. J. & Bradley, L. E. (1993). The Crow Creekmassacre: Initial Coalescent warfare and speculation aboutthe genesis of Extended Coalescent. Plains Anthropologist 38,215–226.