Detection of Counterfeit Telecommunication Products using ...

Improving global health governance to combat counterfeit medicines: a proposal for a...

Transcript of Improving global health governance to combat counterfeit medicines: a proposal for a...

Mackey and Liang BMC Medicine 2013, 11:233http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/233

OPINION Open Access

Improving global health governance to combatcounterfeit medicines: a proposal for aUNODC-WHO-Interpol trilateral mechanismTim K Mackey1,2,3* and Bryan A Liang1,2

Abstract

Background: Perhaps no greater challenge exists for public health, patient safety, and shared global health security,than fake/falsified/fraudulent, poor quality unregulated drugs, also commonly known as “counterfeit medicines”,now endemic in the global drug supply chain. Counterfeit medicines are prevalent everywhere, from traditionalhealthcare settings to unregulated sectors, including the Internet. These dangerous medicines are expanding inboth therapeutic and geographic scope, threatening patient lives, leading to antimicrobial resistance, and profitingcriminal actors.

Discussion: Despite clear global public health threats, surveillance for counterfeit medicines remains extremelylimited, with available data pointing to an increasing global criminal trade that has yet to be addressedappropriately. Efforts by a variety of public and private sector entities, national governments, and internationalorganizations have made inroads in combating this illicit trade, but are stymied by ineffectual governance anddivergent interests. Specifically, recent efforts by the World Health Organization, the primary international publichealth agency, have failed to adequately incorporate the broad array of stakeholders necessary to combat theproblem. This has left the task of combating counterfeit medicines to other organizations such as UN Office ofDrugs and Crime and Interpol in order to fill this policy gap.

Summary: To address the current failure of the international community to mobilize against the worldwidecounterfeit medicines threat, we recommend the establishment of an enhanced global health governance trilateralmechanism between WHO, UNODC, and Interpol to leverage the respective strengths and resources of theseorganizations. This would allow these critical organizations, already engaged in the fight against counterfeitmedicines, to focus on and coordinate their respective domains of transnational crime prevention, public health,and law enforcement field operations. Specifically, by forming a global partnership that focuses on combating thetransnational criminal and patient safety elements of this pre-eminent global health problem, there can be progressagainst counterfeit drugs and their purveyors.

Keywords: Counterfeit medicines, Global health governance, Global health policy, Drug supply chain,Falsified medicines, Fraudulent medicines, Substandard medicines

* Correspondence: [email protected] of Anesthesiology, University of California, San Diego School ofMedicine, 200 W. Arbor Drive, San Diego, CA 92103-8770, USA2San Diego Center for Patient Safety, University of California San DiegoSchool of Medicine, San Diego, USAFull list of author information is available at the end of the article

© Mackey and Liang; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of theCreative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use,distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

2013

Mackey and Liang BMC Medicine Page 2 of 102013, 11:233http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/233

IntroductionA global debate has emerged about the appropriatemeans to address the illicit trade in what have tradi-tionally been known as ‘counterfeit medicines.’ Ideologi-cal and economically motivated arguments over publichealth concerns, intellectual property rights (IPRs), andequitable access to medicines have resulted in a plethoraof related but varying terms attempting to define thisproblem, including: ‘spurious,’ ‘substandard,’ ‘falsified,’‘falsely-labeled,’ ‘fraudulent,’ ‘unregistered,’ ‘counterfeit,’‘fake’ and the collective term ‘substandard/spurious/falsely-labeled/falsified counterfeit medical products’(SSFFC) [1]. The variety of terms utilized illustrates thenumerous, complex, and fractious intersecting political,ideological, and policy issues embedded within the term‘counterfeit medicines’ [1,2], yet ongoing arguments overterminology have distracted attention from the actualglobal health crisis, namely, the continued widespreadavailability of counterfeit medicines in a variety of set-tings that are dangerous to public health. At present, noinclusive global health governance structure exists tomobilize health diplomacy and the multitude of stake-holder resources to combat this serious form of trans-national pharmaceutical crime that affects populationhealth [3]. This despite the fact that as early as 1988, theWorld Health Assembly (WHA) of the World HealthOrganization (WHO) had called for international actionagainst counterfeit medicines in the interest of globalmedicine safety [3].However, with ongoing breaches in the global drug

supply chain and increasing detection, it appears thatkey global policymakers have begun to recognize the sig-nificant public health risks associated with counterfeitmedicines [4]. This includes renewed activities by UNspecialized agencies and other international organiza-tions, as well as patient safety groups, law enforcement,civil society, and the private sector, among others [4-9].Although momentum for international action againstthis public health hazard is building, the existing andemerging initiatives lack policy coherence, and havefailed to coalesce around a unified purpose to protectpatient safety and bring about the necessary inter-national co-operation. As these problem, policy, and pol-itical streams join together, they provide the opportunityfor exploration of enhanced global health governancestructures to address this pre-eminent global healthconcern [10].

Global scope of counterfeit medicinesHarm arises from a wide spectrum of detected dange-rous counterfeit medicines across therapeutic classes,with quality, manufacturing, and/or provenance issuesthat make the product ineffective and/or harmful. Inthis discussion, we focus on the subset of ‘dangerous

counterfeit medicines,’ which are intentionally substand-ard, ineffective, or adulterated, as well as those instanceswhere there is criminal intent to deceive regarding theauthenticity or origin of the medicine. In the case ofdangerous counterfeit medicines, there is a clear publichealth risk, given that these products can be harmful tohealth, there is fraud or criminal intent involved, and/orthe authenticity/quality of the medicine cannot be as-sured. This differs from instances where medicines areunintentionally substandard and do not meet the legallyrequired quality specifications (such as, such as an errorin authorized manufacturing) [1]. In these unintentionalcases, legal principles of negligence can apply, and, ifreckless or egregious, possible criminal sanctions mayalso apply. However, for illicit activities and intentionalfraud, a range of other remedial activities must also beexplored to determine an appropriate regulatory andlegal response.Most importantly, dangerous counterfeit medicines

place all patients at risk, from developed to developingcountries, from formal and informal economy sectors,from rural clinics to tertiary care centers, and fromresource-poor to high-income settings [2,11]. However,global trafficking of counterfeit medicines is difficult toquantify, largely because of the criminal element of thetrade and lack of adequate surveillance [2,3]. Previouscrude estimates indicated that 10% of global medicinesare counterfeit, although experts acknowledge the im-precision, regional variation, and general paucity of databehind this claim [12,13]. A report from the Orga-nisation for Economic Co-operation and Development(OECD) also highlighted the difficulty in assessing coun-terfeit medicines, owing to lack of data, divergent ter-minology, and the standard tenet that covert illegalactivity is difficult to measure [14].Available estimates have placed the global market for

counterfeit medicines at between US$75 and US$200billion, indicating that this is a multibillion dollar illicitenterprise, but also highlighting the wide range and gen-eral lack of reliable information on the topic [12,15].Similarly, the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime(UNODC) estimated that the market for counterfeitanti-malarial drugs was more than US$400 million inwest Africa alone, a region of the world where drugregulatory systems have poor technical capacity and gov-ernance [16,17]. OECD also noted expansion and in-creasing diversity of medicines counterfeited, and anincreasing counterfeit presence in supply chains evenin strongly regulated countries [14]. Finally, WHOitself estimated that the prevalence of counterfeitmedicines ranges from less than 1% in developedcountries, to 10 to 30% in developing markets, and up to50% or more from websites that conceal their physicallocation [11,18].

Mackey and Liang BMC Medicine Page 3 of 102013, 11:233http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/233

Safety dangers are further amplified by the advance-ment in technology and the frenetic pace of globaliza-tion, rendering international borders defenseless. Indeed,a primary mechanism for counterfeit medicine distribu-tion and sourcing is the Internet, which is rarely subjectto effective international oversight [19,20]. Instead, indi-viduals from virtually any country with online access cansearch for and potentially purchase pharmaceuticals, in-cluding essential drugs, vaccines, controlled substances,life-saving medicines for serious conditions, and lifestyleproducts, all from the convenience of a computer oreven from a mobile device [2,14,19,21-26]. Addressingonline counterfeit distribution using multi-sector effortssuch as the enforcement action Operation Pangea I-VIof the International Criminal Police Organization (Interpol)has resulted in millions of counterfeit pill seizures andsome 40,000 websites shut down, but appears to havenot stemmed the continued proliferation of illicit onlinepharmacies [20,27].Publicly available data collected by the Pharmaceutical

Security Institute (PSI), a not-for-profit organization ofpharmaceutical industry security directors collecting andanalyzing information on global pharmaceutical crime(which, in addition to counterfeit incidents, includes il-legal pharmaceutical diversion and theft), also shows in-creasing criminal activity: an alarming 77% overall globalincrease in incidents of pharmaceutical crime were veri-fied from 2005 to 2011 (1,123 to 1,986 incidents) invol-ving 532 different pharmaceutical products [28,29]. PSIinformation is based on an incident-based reporting sys-tem, verified in a similar fashion to information collectedby law enforcement agencies, and is sourced from PSIpharmaceutical member and non-member companies,law enforcement agencies, healthcare/regulatory agen-cies, and open-source media reports. To be included, acounterfeit product, using WHO definitions, must besupported by factual information validated by a team ofmultilingual criminal analysts from PSI [30].However, these measurements are likely to be incom-

plete, and may underestimate the scope of the issue.Even beyond the challenges in assessing criminal activity,there is difficulty in assessment in regions such asAfrica, which suffer from low surveillance and reporting.Further, trade in counterfeit medicines often affectsmore than one country, making detection and accuratereporting of origin, transit countries, and destinationdifficult. In addition, measurement limits such as diffi-culty in detection, reporting bias across regions, lack oflaboratory capacity to confirm that the product iscounterfeit, and lack of comprehensive data surveil-lance sources, mean that conclusions from such dataare limited. These limitations emphasize the need forbetter data collection, more robust monitoring andsurveillance, and a requirement for mandatory reporting

at the individual country level to better inform researchersand policymakers about the scope of this global healthproblem.

Limitation of current public health effortsAlthough the available data describing the problem ofglobal counterfeit medicines is less than robust, there isbroad international consensus that this criminal trade isa serious global public health issue needing immediateaction [1,2,4]. Recent investigations and law enforcementefforts have uncovered large-scale illegal counterfeitmanufacturing in emerging markets, ties to organizedcrime and terrorism, and record global seizures in bothproducing and consuming countries, all associated withpatient deaths worldwide [2,4,14,27].Several key international organizations, including WHO,

UNODC, Interpol, and the World Customs Organization(WCO), have attempted to address the global counter-feit medicines issue. Most notably, beginning in 1988,WHO has repeatedly issued resolutions and guidance,while also attempting to be actively engaged in devel-oping policies, programs and governance activities(including its Good Governance for Medicines program)in an attempt to ensure access to safe medicines andcombat against counterfeit drugs [3,31]. However, itshould be noted that WHO does not have enforcementcapabilities, cannot specifically address criminal or lawenforcement issues, and generally engages in technicalcapacity building if resources are available. These limi-tations hamper any attempted response to the criminalelement actively involved in the trade of dangerouscounterfeit medicines.More recently, WHO has struggled to tackle this prob-

lem effectively, owing to divergent member state con-cerns, incompatible ideologies between public healthand commercial IPRs, limitations of its current memberstate-centric governance structures, and lack of adequateresources including challenges from ongoing WHO re-form [32,33]. These conflicts have severely hampered aglobal response to the counterfeit medicines trade, andhave necessitated the entry of new international organi-zations, such as UNODC and Interpol, because ofconcern of WHO leadership and the need for active, fo-cused, and effective engagement against the criminalnetworks involved in this trade [34].Specifically, the attempts by WHO to foster partner-

ships in combating this illicit trade and engage a broaderbase of stakeholders has garnered harsh criticism. Forexample, the WHO-chaired International Medical Pro-ducts Anti-Counterfeiting Taskforce (IMPACT) broughttogether a number of governments, international organi-zations, civil society groups, private sector actors, lawenforcement agencies and others to combat this activityin 2006 [35]. However, the future viability of IMPACT is

Mackey and Liang BMC Medicine Page 4 of 102013, 11:233http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/233

doubtful. Instead, WHA recently adopted the establish-ment of a new member state mechanism (MSM) in re-sponse to criticism regarding perceived associations ofWHO with enforcement activities during its relationshipwith IMPACT, primarily stemming from a customs sei-zure in the Netherlands of generic pharmaceutical pro-ducts en route from India to Brazil [3,36].Importantly, MSM is a new governance structure

driven exclusively by member state participation, anddoes not involve active inclusion of important non-member state stakeholders that have been instrumentaland active in combating this criminal trade [37]. This re-gression is symptomatic of larger contextual governanceproblems within WHO. This includes the failure ofthe WHA to adopt inclusive governance reforms (spe-cifically, the World Health Forum proposal) to ensureadequate funding and broader stakeholder participa-tion [38]. This reflects the reality that WHO is sig-nificantly limited in its ability to engage and leverageresources of multiple stakeholders under its currentgovernance structures, lacks the necessary partner-ships to provide crucial information for enforcementoperations, and has deficient resources to address theissue programmatically.

Filling the gap: UNODC, Interpol, and other organizationsIn response to WHO governance limitations, otherinternational organizations are filling the gap in institu-tional capability that WHO is unable to provide. Thisprimarily involves UNODC, which specializes in estab-lishing policy and coordinating actions in combating allforms of transnational organized crime, including crimeprevention, criminal justice, corruption, terrorism, andthe trade and trafficking of illicit drugs worldwide [39].All these elements have direct ties to the trade in dan-gerous counterfeit drugs, and emerging engagement ofUNODC has already brought much-needed attention tothe fight against this form of transnational pharmaceut-ical crime. Further, UNODC administers internationaltreaties that can be extended to criminal activities in-volving dangerous counterfeit medicines, such as theUN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime(UNTOC), which has widespread international adoption,applicability, and viable enforcement mechanisms [3].Fortunately, UNODC is no stranger to engagement in

global health, as evidenced by its mandate to participatein HIV/AIDS prevention through its ‘Think AIDS’ cam-paign and other health activities [40,41]. In addition,Resolution 20/6 by the UN Commission on Crime Pre-vention and Criminal Justice (CCPCJ) specifically re-quested and empowered UNODC to engage in the fightagainst ‘fraudulent’ counterfeit medicines by conductingresearch, providing technical assistance to member states,and co-operation with other international organizations

[5]. The CCPCJ resolution in conjunction with a recentUNODC high-level conference of experts on fraudulentmedicines makes it clear that UNODC now has an im-portant role to play in global governance responses todangerous counterfeit medicines [39].UNODC has also partnered effectively with other

international organizations, such as Interpol, WCO, andkey actors in the public and private sectors, to lead ini-tiatives that directly target pharmaceutical crime throughmulti-sectoral law enforcement and border controlprograms [42]. Importantly, UNODC resolutions havehistorically supported and gained broad and inclusivestakeholder engagement, extending beyond traditionalmember state-only inclusion. Avoiding incompatible anddivergent member state domestic policy interests by fo-cusing primarily on the transnational criminal aspects ofdangerous counterfeit medicines, UNODC represents amore effective forum for stakeholder collaboration andco-operation, but one that has yet to be fully leveraged.In addition to UNODC activities, Interpol has had a

long-standing and effective role in facilitating training,capacity building, investigations, enforcement, and pro-secutions against dangerous counterfeit drug purveyorsboth regionally and globally, and therefore should besought as an active partner in any response. Interpol hasthe ability to mobilize law enforcement, customs andborder assets, and also engage with both the public andprivate sectors (including scientific experts, financial in-stitutions, laboratory facilities, and the pharmaceuticalindustry) to develop intervention packages that supporton-the-ground operations aimed at directly disruptingthe trade in counterfeit medicines in both the regulatedand unregulated global drug supply chain [43,44]. In-deed, Interpol has been the central actor in large globalseizures of dangerous drugs, and has recently initiatedthe creation of the Interpol Pharmaceutical Crime Pro-gramme as a comprehensive anti-pharmaceutical crimeinitiative, in partnership with 29 of the world’s largestpharmaceutical firms [45].Hence, both UNODC and Interpol have demonstrated

an ability to engage effectively with other importantnon-member state stakeholders on dangerous coun-terfeit medicines, whereas WHO has experienced chal-lenges. This more inclusive approach has resulted intangible results, including global co-operation in fieldoperations that have led to counterfeit drug seizures,illicit website closures, arrests, and ongoing investiga-tions [27]. However, despite this relative progression byUNODC and Interpol on the issue, it is also clear thatoperations and policy formulation need to be informedby evidenced-based data and increased surveillance onthe public health and patient safety risks of dangerouscounterfeit medicines, which have traditionally been theexpertise of organizations such as WHO.

Mackey and Liang BMC Medicine Page 5 of 102013, 11:233http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/233

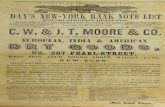

Enhanced global health governance: UNODC-WHO-Interpol trilateral co-operation mechanismCurrently, the official program activities of UNODC,WHO, and Interpol operate in isolation or through adhoc partnerships that lack a formal and sustained gov-ernance mechanism. As an example, neither UNODCnor Interpol have observer status in the new WHOMSM, despite the fact that both of these organizationshave institutional experience in cooperating with WHOthrough initiatives like IMPACT and Interpol operationsin the past [34]. This lack of an active co-operationmechanism is worrisome, and provides an indicationthat WHO may no longer be seeking formal active en-gagement with other international organizations andactors outside of its MSM, at a time when broader en-gagement is crucial.In order to move forward, the respective technical

expertise, international legitimacy, financial and non-financial resources, and leveraging of existing partner-ship networks between these organizations must becoordinated to create a cohesive and transparent gover-nance framework. Given emerging strengths of UNODCas a more inclusive governance forum for broader

Figure 1 Trilateral working group on counterfeit medicines.

stakeholder mobilization and its UN mandate throughCCPCJ, a trilateral governance mechanism under theauspices of UNODC, with the active participation ofWHO and Interpol, should be established [34]. Wepropose the basic structure and primary roles of the or-ganizations participating in this mechanism in Figure 1.This could be accomplished by creating a permanent

intergovernmental trilateral working group (TWG) com-posed of UNODC as the chair, and WHO and Interpolas strategic partners. The purpose of the permanentTWG would focus on enabling coordination and co-operation specifically for combating the global tradein dangerous counterfeit medicines, all within the re-spective mandates and subject matter domains of eachorganization. A similar governance structure was ex-plored by the WHO working group of member states onSSFFC in September 2011, but was dropped in favor ofthe current WHO MSM [46].Fortunately, partnerships within and between UN

specialized agencies and other international/intergo-vernmental organizations are not particularly new. Forexample, WHO, the World Intellectual Property Orga-nization (WIPO), and the World Trade Organization

Mackey and Liang BMC Medicine Page 6 of 102013, 11:233http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/233

(WTO) recently engaged in a trilateral co-operationmechanism on the issue of intellectual property andpublic health, a topic with direct relevance to the globaldebate on counterfeit medicines [47]. Multiple stake-holder global environmental governance coordinatedthrough UN agencies, such as the United Nations Envir-onmental Programme, have also been used to enhanceinternational co-operation, promote national develop-ment planning, provide technical assistance, strengthenlaws and institutions, and engage in science-basedpolicy-making for transnational issues regarding the en-vironment [48].Enabling a pathway for the TWG could be the role of

the United Nations Office of Partnerships (UNOP).UNOP serves as a gateway for partnership and allianceopportunities within the UN, as well as engagement withthe private industry, foundations, and civil society on is-sues supporting progress towards achieving the Millen-nium Development Goals (MDGs) [49]. As the publichealth threat of counterfeit medicines directly affectspopulation-based health and health-related MDGs as aresult of treatment failure, anti-microbial resistance, andpatient injury (leading to stunted economic developmentand productivity), morbidity, and mortality, developmentof partnership collaborations on dangerous counterfeitmedicines would fit into the goals of the programmaticactivities of UNOP, and consequentially should beexplored.Specifically, a trilateral UNODC-WHO-Interpol struc-

ture would also allow the different organizations to moreeffectively manage appropriate relationship with theirown interest-minded stakeholders, all within their re-spective domains and internal governance requirements;for example, WHO could manage public health, drugregulatory authority and access to medicine stake-holders; UNODC could interface with private sectoractors, customs agencies, and international crime andjustice groups; and Interpol could primarily engagewith law enforcement officials and engage in publicoutreach/education campaigns.Importantly, governance should be transparent, so that

the TWG can ensure the legitimacy and appropriate in-clusion of necessary stakeholders in its actions. Thiswould allow for specialization of tasks at a high level,and reduce the duplicative efforts that currently operatein parallel under existing initiatives [3]. Further, eachorganization could establish its own national singlepoints of contact within these subject-area domains. toenable more effective communication and informationsharing from the TWG to relevant national authoritiesfor translation of data and global policy development.Resources to fund activities of the TWG could be pro-cured from a variety of sources subject to individualorganizational requirements. Hence, WHO could limit

participation and funding on issues within its domainthat might prove controversial to its member states,whereas UNODC and Interpol might more freely engagein funding mechanisms from both member and non-member states and entities. However, a minimum per-centage of all collected funds should be earmarked tosupport the general operations of the Trilateral WG inorder to ensure sustainability and maintain internationalattention and co-operation against dangerous counterfeitmedicines, similar to other proposals for global healthgovernance and financing reform [38].The TWG could also develop specific technical work-

ing groups to address unique and key risk factors in thedangerous counterfeit medicines trade that require theimmediate attention and targeted expertise of selectparticipants (Table 1). These groups could include pro-grammatic areas of: 1) global surveillance, pharmacovigi-lance, and data collection (including development of acentral surveillance system, international tracking andtracing systems/standards, and possible development ofm-pedigree solutions); 2) regulatory, legal and policy de-velopment (to strengthen rule of law, enforcement, anddrug regulatory systems); 3) public outreach and educa-tion (to inform consumers, patients, healthcare workers,government agencies, and civil society, among others,about the dangers of counterfeit medicine); and 4) infor-mation technology and cybercrime (to address specificrisk factors such as the link between cybersecurity andcrime and illicit Internet-based sourcing). These tech-nical working groups should also examine existing re-gional or in-country models/tools aimed at combatingdangerous counterfeit medicines for potential regionalor global scalability.The recent emergence of UNODC as an international

forum to lead criminal enforcement action against dan-gerous counterfeit medicines provides an opportunityfor better balancing of global health governance throughthe proposed TWG. Using UNODC as the lead inter-national agency charged with the task of assessing andcoordinating stakeholder actions, coalescing specificallyaround transnational criminal activity of the dangerouscounterfeit medicines trade, should also allow WHO thefreedom to operate as the expert technical agency it isand redirect global efforts towards crime prevention andpatient safety protection.Importantly, WHO can assess and recommend mea-

sures to promote public health issues arising from dan-gerous counterfeit medicines, and contribute specializedscientific and public health knowledge to this effort.WHO could then concentrate on the core issues ofimproving access to safe medicines, strengthening healthsystems for better surveillance, developing monitoringand evaluation protocols for sourcing/distributing safedrugs, strengthening domestic drug regulatory and

Table 1 Proposed specific technical working groups with the trilateral working group

Area of focus Description Existing models/tools Goals

Global surveillance,pharmacovigilance,and data collection

Specialized technical group to developa global, centralized, and harmonizedsurveillance system for counterfeitmedicine detection, reporting, and datasharing. Would also work to developprocess for global report on counterfeitmedicines

Pharmaceutical Security InstituteCounterfeit Incident System. WHO PilotSSFFC Global Surveillance andMonitoring Project

Establish an active an internationallyagreed upon and scientifically validatedsystem for reporting and detection ofcounterfeit medicines from varioussources, including drug regulatoryagencies, customs officials, public healthagencies, consumers and clinicians, andlaw enforcement. Would allow fordevelopment of data collection frommultiple stakeholders that would informevidence-based policy-making bothdomestically and globally. Also possiblydevelop globally harmonized trackingand tracing system, development of e-pedigree/m-pedigree technologies, orbest practices from regional or country-level initiatives

Regulatory, legaland policydevelopment

Would work to harmonize criminal legalframeworks against counterfeitmedicines, harmonizepharmacovigilance activities forcounterfeit detection, engage inregulatory capacity building andstrengthen pharmaceutical goodgovernance

UNTOC: Application of counterfeitmedicines trade as ‘serious crime’ underUNTOC existing framework andtransnational enforcement tools, Councilof Europe MEDICRIME Convention: FirstInternational Counterfeit Medicinestreaty, UN Environmental ProgrammeBasel Convention on transboundarymovement and management ofhazardous waste for pharmaceuticals

Aim to develop and implement publicpolicy, laws, and regulations at local,national, regional, and potentially globallevels to combat the criminal trade indangerous counterfeit medicines. Alsoaim to strengthen pharmaceuticalgovernance to address corruption inhealth systems associated with drugsupply delivery. Should explore existingregulations, laws, legislation, and treatyinstruments for possible expansion orimmediate application. This specificallyincludes application of internationaltreaty instruments such as UNTOC,MEDICRIME, and the Basel Convention

Public outreach andeducation

Development of a unified and effectivepublic outreach and educationcampaign tailored and aimed at adiverse group of stakeholders includingconsumers/patients, healthcareprofessionals, law enforcement, drugregulators, customs agents,policymakers, civil society, and otherinterested parties. Use of multimediachannels and mediums to obtainbroadest coverage sensitive to targetaudience

Interpol Counterfeit MedicinesAwareness Campaign 2010, US Foodand Drug Administration: BeSafeRxCampaign, National Agency for Food,Drug Administration and Control(Nigeria) educational campaigns, HongKong Consumer Council outreach andawareness program on pharmaciesestablishments detected as sellingcounterfeit medicines

Fund initiatives to increase globalawareness among all interested partiesregarding the public health and patientsafety dangers of counterfeit medicines.These efforts would attempt to addressthe demand side of counterfeitmedicines from end users, increaseengagement on prevention fromhealthcare professionals, and enable allstakeholders to better report suspectmedicines to the relevant authorities

Informationtechnology andcybercrime

Special technical working groupcomposed of specialists in informationtechnology, cybersecurity, public health,and law enforcement, with a mandateto specifically address ties betweentransnational cybercrime and illicitonline pharmacies

Interpol Pangea I-VI MultistakeholderOperations.

Development of specific informationtechnology tools to detect and shutdown illicit online pharmacies andaffiliated third-party enablingtechnologies. Exploration of existingweb monitoring technologies forInternet content surveillance, utilizationof tools for technical blocking ofviolating websites, suspension offinancial transactions/processing, anduse of other fraud detection tools.Systems that enable verification andcertification of legitimate onlinepharmacies with education of theconsumer should also be pursued

Public-private partnerships: US Alliancefor Safe Online Pharmacies; Center forSafe Internet Pharmacies, Integrationwith current global efforts of theInternet Governance Forum to promoteonline safety

Mackey and Liang BMC Medicine Page 7 of 102013, 11:233http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/233

pharmaceutical governance capacity, and collecting dataand studying the epidemiology of counterfeit drugs to en-hance the efforts of UNODC and Interpol. Paramount tothis effort is the need for more accurate and reliable dataon the prevalence of dangerous counterfeit medicines, and

surveillance and laboratory capacity for identification. In-deed, proper and robust data collection is fundamentalfor justifying appropriate regulatory, legal, and law en-forcement action. Efforts could include enhancementof data collection under the WHO SSFFC Global

Mackey and Liang BMC Medicine Page 8 of 102013, 11:233http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/233

Surveillance and Monitoring Project by harmonizingreporting fields and collecting information from a varietyof sources (including drug regulatory, customs, and lawenforcement authorities) to form a centralized database.This infrastructure would provide a better evidence basefor determining the true scope of the global counterfeitmedicines trade [50].This trilateral proposal allows UNODC, in direct part-

nership with WHO and Interpol, to lead the effort on glo-bal enforcement against dangerous counterfeit medicines,independent of contentious IPR considerations, focusinginstead on established criminal activities [34]. WHO couldobjectively identify incidents that present a global publichealth danger, without consideration of IPRs, and sharethese findings to this partnership for further assessmentbased on scientifically validated data. Hence, involvementof WHO would provide crucial public health informationto guide criminal enforcement efforts, capacity building,and policy development on the issue, which is largely ab-sent now. UNODC could then actively coordinate and en-act policy to address pharmaceutical transnational crime(including potential applicability of UNTOC), with Inter-pol engaging in educational outreach and mobilizing glo-bal law enforcement resources to actively disrupt criminalnetworks [34]. Trade and IPR disputes would continue tobe heard by WTO and WIPO independently within theirrespective dispute resolution forums. Drugs not fitting theparameters of the dangerous counterfeit drugs group, butthat potentially violate IPRs, would be subject to WTOand WIPO dispute resolution procedures and assessedoutside of the scope of the public health and criminalactivity considerations of the TWG. However, any such as-sessment should also recognize public health prioritiesexpressed by other international treaties, specifically theWTO Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual PropertyRights (TRIPS) Doha Declaration [51]. These agreementsreaffirm rights of member states to exercise TRIPS flexibi-lities in response to a national health emergency in en-suring equitable access to medicines.Such division of labor lends itself to better specialization

of UN agencies, leveraging their respective institutionalstrengths and resources, and establishing better globalhealth governance to combat dangerous counterfeit medi-cines. The union of these specialized UN agencies andintergovernmental organizations under UNODC leader-ship through the TWG would bring global coverage andenhanced policy coherence to the issue. It would also pro-vide greater legitimacy to actions, given that they aremultilateral in nature and not merely regional arrange-ments. Most importantly, it would separate contentiouspolicy issues such as organized crime and public healthfrom IPR, and trade into appropriate international forumsthat may act collaboratively towards shared social welfare,equity, and justice goals.

ConclusionRecognition, coordination, and active engagement of keystakeholders is essential in combating the global healthcrisis of dangerous counterfeit medicines. UNODC rep-resents the best forum to engage the multitude of frag-mented actors currently addressing this issue. Hence,enhanced global health governance and shared responsi-bility through a UNODC-WHO-Interpol TWG mecha-nism may provide a plausible way forward to promoteglobal health security, combat transnational pharmaceu-tical crime, and, most importantly, ensure safe access tomedicines.

AbbreviationsCCPCJ: UN Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice;IMPACT: International Medical Products Anti-Counterfeiting Taskforce;Interpol: International Criminal Police Organization; MSM: World HealthOrganization New Member State Mechanism; OECD: Organisation forEconomic Co-operation and Development; PSI: Pharmaceutical SecurityInstitute; SSFFC: Substandard/spurious/falsely-labeled/falsified counterfeitmedical products; TRIPS: WTO Trade-Related Aspect of Intellectual PropertyRights; UNODC: United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime; UNOP: UnitedNations Office for Partnerships; UNTOC: United Nations Convention againstTransnational Organized Crime; WCO: World Customs Organization;WHA: World Health Assembly; WHO: World Health Organization; WIPO: WorldIntellectual Property Organization; WTO: World Trade Organization.

Competing interestsTKM and BAL received journal open access fees support from thePartnership for Safe Medicines (PSM) for this submission, but otherwisereceived no extramural support from any organization for the submittedwork. TKM is the 2011–2013 Carl L. Alsberg MD Fellow of PSM, whichsupports his general research activities. BAL is a voluntary board memberand Vice President of PSM, and receives no compensation for any PSMactivities. PSM is not connected with the submitted work. BAL also serves asa member of the National Patient Safety Foundation Research ProgramCommittee, which considers grant proposals addressing medication safety.TKM and BAL report no other relationships or activities that could appear tohave influenced the submitted work.

Author’s contributionsWe note that with respect to author contributions, TKM and BAL jointlyconceived the study, and jointly wrote and edited the manuscript. Bothauthors read and approved the final manuscript.

AcknowledgementsBAL and TKM gratefully acknowledge the United Nations Office of Drugs andCrime, and its invitation to and participation in the 2013 Technical ExpertsMeeting; the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers andAssociations and its invitation to and participation in the 2013 Anti-Counterfeit Action Plan and Dedicated Communications Network CrossCutting Expert Meeting; the Pharmaceutical Security Institute and Europol,and their invitation to and participation in the 2013 PSI-Europol Meeting ofthe Security Directors and Global Law Enforcement Against CounterfeitDrugs; the Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation Community and the USDepartment of Commerce, and their invitation to and participation in the2013 Life Sciences Innovation Forum Public Awareness and Establishing aSingle Point of Contact Governance Meeting.

Author details1Department of Anesthesiology, University of California, San Diego School ofMedicine, 200 W. Arbor Drive, San Diego, CA 92103-8770, USA. 2San DiegoCenter for Patient Safety, University of California San Diego School ofMedicine, San Diego, USA. 3Institute of Health Law Studies, CaliforniaWestern School of Law, San Diego, USA.

Received: 31 July 2013 Accepted: 3 October 2013Published: 31 Oct 2013

Mackey and Liang BMC Medicine Page 9 of 102013, 11:233http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/233

References1. Attaran A, Barry D, Basheer S, Bate R, Benton D, Chauvin J, Garrett L,

Kickbusch I, Kohler JC, Midha K, Newton PN, Nishtar S, Orhii P, McKee M:How to achieve international action on falsified and substandardmedicines. BMJ 2012, 345:e7381.

2. Mackey TK, Liang BA: The global counterfeit drug trade: patient safetyand public health risks. J Pharm Sci 2011, 100:4571–4579.

3. Mackey TK: Global health diplomacy and the governance of counterfeitmedicines: a mapping exercise of institutional approaches. J HealthDiplomacy 2013, 1.

4. Institute of Medicine: Countering the problem of falsified and substandarddrugs. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2013/Countering-the-Problem-of-Falsified-and-Substandard-Drugs.aspx.

5. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: Resolution 20/6: Counteringfraudulent medicines, in particular their trafficking. http://www.unodc.org/documents/commissions/CCPCJ/CCPCJ-ECOSOC/CCPCJ-ECOSOC-00/CCPCJ-ECOSOC-11/Resolution_20-6.pdf.

6. Interpol: Pharmaceutical crime: A major threat to public health. http://www.interpol.int/Crime-areas/Pharmaceutical-crime/Pharmaceutical-crime.

7. World Health Organisation: Options for the structure and governance of theMember State mechanism on substandard/spurious/ falsely-labelled/falsified/counterfeit medical products: Report by the Secretariat. http://apps.who.int/gb/ssffc/pdf_files/A_MSM1_3-en.pdf.

8. International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations:The IFPMA Ten Principles on Counterfeit Medicines. http://www.ifpma.org/fileadmin/content/News/2010/IFPMA_Ten_Principles_on_Counterfeit_Medicines_12May2010.pdf.

9. World Customs Organization: Cotonou Declaration against fake medicines,12 October 2009, Cotonou (Benin). http://www.wcoomd.org/en/topics/enforcement-and-compliance/activities-and-programmes/~/media/WCO/Public/Global/PDF/Topics/Enforcement%20and%20Compliance/Activities%20and%20Programmes/IPR/Cotonou%20Declaration/Announcement%20on%20Cotonou%20Declaration%20UK.ashx.

10. Kingdon JW, Thurber JA: Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, UpdateEdition, with an Epilogue on Health Care. Addison-Wesley Longman; 2010.

11. World Health Organization: Medicines: counterfeit medicines. http://www.who.int/medicines/services/counterfeit/impact/ImpactF_S/en/index.html.

12. World Health Organization: Growing threat from counterfeit medicines.Bull World Health Organ 2010:247–248.

13. Fighting fake drugs: the role of WHO and pharma. Lancet 2011,377:1626.

14. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: The EconomicImpact of Counterfeiting and Piracy, Organisation for Economic Co-Operationand Development. Paris, France: OECD Publishing; 2008:1–399.

15. Customs group to fight $200 bln bogus drug industry. http://www.reuters.com/article/2010/06/10/us-customs-drugs-idUSTRE65961U20100610.

16. Gostin LO, Buckley GJ, Kelley PW: Stemming the global trade in falsifiedand substandard MedicinesStemming the global trade in substandardmedicines. JAMA 2013, 309:1693–1694.

17. Cohen JC, Mrazek M, Hawkins L: Tackling corruption in thepharmaceutical systems worldwide with courage and conviction.Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007, 81:445–449.

18. World Health Organization: Counterfeit medicines: an update on estimates 15November 2006. http://www.who.int/medicines/services/counterfeit/impact/TheNewEstimatesCounterfeit.pdf.

19. Liang BA, Mackey T: Searching for safety: addressing search engine,website, and provider accountability for illicit online drug sales. Am JLaw Med 2009, 35:125–184.

20. Mackey TK, Liang BA: Pharmaceutical digital marketing and governance:illicit actors and challenges to global patient safety and public health.Global Health 2013, 9.

21. Campbell N, Clark JP, Stecher VJ, Goldstein I: Internet-ordered Viagra(sildenafil citrate) is rarely genuine. J Sex Med 2012, 9:2943–2951.

22. Liang BA, Mackey TK: Vaccine shortages and suspect online pharmacysellers. Vaccine 2012, 30:105–108.

23. Forman RF: Availability of opioids on the internet. JAMA 2003,290:889.

24. Forman RF, Block LG: The marketing of opioid medications withoutprescription over the internet. J Publ Pol Market 2006, 25:133–146.

25. Mackey TK, Liang BA: Oncology and the internet: regulatory failure andreform. J Oncol Pract 2012, 8:341–343.

26. Khan MH, Tanimoto T, Nakanishi Y, Yoshida N, Tsuboi H, Kimura K:Public health concerns for anti-obesity medicines imported forpersonal use through the internet: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open2012, 2.

27. Interpol: Operations. http://www.interpol.int/Crime-areas/Pharmaceutical-crime/Operations/Operation-Pangea.

28. Pharmaceutical Security Institute: Incident Trends. http://www.psi-inc.org/incidentTrends.cfm.

29. Pharmaceutical Security Institute: Counterfeit Situation: TherapeuticCategories. http://www.psi-inc.org/therapeuticCategories.cfm.

30. Pharmaceutical Security Institute: Counterfeit Situation - Definitions. http://www.psi-inc.org/counterfeitSituation.cfm.

31. World Health Organization: WHO’s relationship with the International MedicalProducts Anti-Counterfeiting Taskforce. http://apps.who.int/gb/ssffc/pdf_files/A_SSFFC_WG4-en.pdf.

32. World Health Organization: Substandard/Spurious/Falsely-Labelled/ Falsified/Counterfeit Medical Products: Report by the Director-General. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA64/A64_16-en.pdf.

33. Intellectual Property Watch: WHO Members Show Dismay At DelayOn Counterfeit Medicines Group. http://www.ip-watch.org/weblog/2011/01/19/who-members-show-dismay-at-delay-on-counterfeit-medicines-group/.

34. Mackey TK, Liang BA, Kubic TT: Dangerous doses: fighting fraud in theglobal medicine supply chain. Foreign Aff 2012.

35. World Health Organization: Conclusions and recommendations of theWHO international conference on combating counterfeit medicines:declaration of Rome. http://www.who.int/medicines/services/counterfeit/RomeDeclaration.pdf.

36. World Health Organization: Sixty-Fifth World Health Assembly: Agenda item13.13: WHA65.19. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s19994en/s19994en.pdf.

37. World Health Organization: Report of the First Meeting of the MemberState mechanism on substandard/spurious/falsely- labelled/falsified/counterfeit medical products. http://apps.who.int/gb/ssffc/pdf_files/A_MSM1_4-en.pdf.

38. Mackey TK, Liang BA: A United Nations global health panel for globalhealth governance. Soc Sci Med 2012, 76:12–15.

39. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: Experts discuss the role oforganized crime in the production and trade of fraudulent medicines.http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2013/February/conference-focuses-on-the-role-of-organized-crime-in-the-trafficking-of-fraudulent-medicines.html?ref=fs4.

40. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: How UNODC deals with HIV.http://www.unodc.org/unodc/hiv-aids/index.html.

41. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: Think AIDS before you shareneedles. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/think-aids-before-you-share-needles.html.

42. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: Criminals rake in $250 billion peryear in counterfeit goods that pose health and security risks. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2012/July/criminals-rake-in-250-billion-per-year-in-counterfeit-goods-that-pose-health-security-risks-to-unsuspecting-public.html.

43. Europol: Europol and Interpol enhance cooperation against counterfeiting totransform regional success into global action. https://www.europol.europa.eu/content/press/europol-and-interpol-enhance-cooperation-against-counterfeiting-transform-regional-suc.

44. Interpol: Global operation strikes at online supply of illegal and counterfeitmedicines worldwide. http://www.interpol.int/News-and-media/News-media-releases/2011/PR081.

45. Interpol: Interpol and pharmaceutical industry launch global initiative tocombat fake medicines. http://www.interpol.int/News-and-media/News-media-releases/2013/PR031.

46. World Health Organization: WHO’s role in the prevention and control ofmedical products of compromised quality, safety and efficacy such assubstandard/spurious/falsely-labelled/ falsified/counterfeit medical products.http://apps.who.int/gb/ssffc/pdf_files/A_SSFFC_WG2_3-en.pdf.

47. World Intellectual Property Organization: WHO, WIPO, WTO TrilateralCooperation on Public Health, Intellectual Property and Trade, http://www.wipo.int/globalchallenges/en/health/trilateral_cooperation.html.

48. United Nations: Environmental Governance. http://www.unep.org/pdf/brochures/EnvironmentalGovernance.pdf.

Mackey and Liang BMC Medicine Page 10 of 102013, 11:233http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/233

49. United Nations Environment Programme: United Nations Office forPartnerships. http://www.un.org/partnerships/.

50. World Health Organization: Ninth meeting of the WHO Advisory Committeeon Safety of Medicinal Products. http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/safety_efficacy/ACSoMP9.pdf.

51. World Trade Organization: Doha 4th Ministerial - Ministerial declaration.http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/minist_e/min01_e/mindecl_e.htm.

Cite this article as: Mackey and Liang: Improving global healthgovernance to combat counterfeit medicines: a proposal for a UNODC-WHO-Interpol trilateral mechanism. BMC Medicine

10.1186/1741-7015-11-233

2013, 11:233

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Centraland take full advantage of:

• Convenient online submission

• Thorough peer review

• No space constraints or color figure charges

• Immediate publication on acceptance

• Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar

• Research which is freely available for redistribution

Submit your manuscript at www.biomedcentral.com/submit