Impacts of the organisation challanges and capacities on attendees satisfaction

Transcript of Impacts of the organisation challanges and capacities on attendees satisfaction

UNIVERSITY

of

GREENWICH

A THESIS ON

“IMPACTS OF THE ORGANISATION CHALLENGESAND CAPACITIES ON ATTENDEES SATISFACTION

AT THE LOCAL COMMUNITY FESTIVALS” Submitted for partial fulfilment of award of

MASTER OF ARTS IN EVENTS MANAGEMENT

By

OZGE ALI

STUDENT ID: 000802210-0

SUPERVISOR

PETER VLACHOS

DEPARTMENT OF MARKETING, EVENTS and TOURISMSCHOOL OF BUSINESS

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

September 2014

ABSTRACT

This study examines the impacts of the organizations’

challenges on the attendees’ satisfaction at local

community events. 255 attendees responded the attendees’

satisfaction survey, four interviews were conducted with

the organisers’ and five community festivals were

observed. The major findings of this study are;

identified the Volunteer organizer constraints and

capacities are not reflecting attendees’ satisfaction.

Conversely, overall enjoyment was correlated with

attendees’ demographic structure. For each festivals

five different activities recognized the responses of

the attendees enjoyed during the event those are

included; the entertainment, children activities,

stalls, food and drink options, and socializing. In

contrast to the most enjoyed activities, the festival

goers made improvement suggestion in seven different

categories. These include; Food and drink options,

entertainment, stalls, children activities, monetary

request, environmental issues and marketing. The

results demonstrate no significant difference for the

attendee’s satisfaction between the two different

locations and the community festival which is run by

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

volunteers and local council. Moreover, while the local

council community festival host 30,000 attendees, the

volunteer organizations hosts between 200 to 7000

festival goers. The responders overall satisfaction does

not reflect the difference in the size of the events. In

depth interviews demonstrated that the volunteer

festival organisers’ major constraints are retain the

volunteers, legal requirements, in sufficient support

for improve organisations capacities. In this study

overall findings provide information for the community

festivals stakeholders regarding managerial constraints

and attendees’ satisfaction at community festivals.

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

Table of Contents

Title Page

Declaration Form

Abstract

List of Contents

Acknowledgements

1.0 Introduction 1

1.1 The Study Aims and Objectives 2

1.2 Background of the Study 3

1.3 Justification of the Study4

1.4 Conclusion of the Introduction 5

2.0 Literature Review 62.1 Community Festivals

2.1.1 Definition of Community Festivals 6

2.1.2 Aims and Powers of Community Festivals7

2.1.3 Impacts of Community Festivals9

2.1.4 Issues Related with Community Festival Management9

2.2 Volunteer Management Constraints11

2.2.1 Definition of Volunteer11

2.2.2 Volunteer Constraints12

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

2.3 Attendees Satisfaction 14

2.3.1 Factors for Attendees Satisfaction14

2.3.2 Importance of Measuring Attendees’ Satisfaction15

2.3.3 Attendees Reasons to Attend Community Festivals16

3.0 Methods Used 17

3.1 Multi-Methods and Analysis Graphs17

3.2 Research Approach 18

3.3 Research Design 19

3.4 Research Methods 19

3.5 Sampling Strategies 20

3.6 Instrument Design 22

3.7 Data Collection Techniques22

3.8 Method Analysis 24

3.9 Discussion of This Study Ethical Consideration24

3.1.1 Limitation of Methodology24

3.1.2 Conclusion of the Methodology Chapter26

4.0 Results and Analysis 27

4.1 Data Results for Attendees’ Satisfaction27

4.2 Discussion of Community Festivals Research Data-

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

2014 - South East London 32

4.2.1 Greenwich PARKSFest (Hornfair Park and Eltham South)39

4.3 Organisers Challenges and Capacity Data40

4.3.1 Discussion of Findings Festival Organisers “A” 43

4.3.2 Discussion of Findings Festival Organiser “B”44

4.3.3 Findings, of the Semi-Independent Volunteer Organiser 44

4.3.4 Findings of Community Festival Run by Council45

4.4 Discussion of the All Festivals Included in This Study45

5.0 Conclusion 48

5.1 Review of the Study Aims and Objectives48

5.2 Key Findings 49

5.3 Key Conclusions and Recommendations 50

5.4 Recommendation for the Future Research50

6.0 References 57

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

I am immensely lucky to work with Peter Vlachos whoencouraged and guided me through each stage of thisresearch as my supervisor and made me believe inmyself, it was a real privilege to work with him. Onceagain thank you Peter.

Also, I would like to add my gratitude to communitychampions for their participation for the communityfestivals; Sarah Parker, Claire Cowen, Terry Powley andJohn Fahy. While I have an opportunity, I would like tosay thanks, the precious benefits that I gained duringmy education; Irem Akin and Weiwei Liu.

This piece of paper demonstrates how festivals areuseful for bringing people together to share the sameexperience with others, regardless of whichorganisation organised the events, regardless of whatthe aims of the organisation. No matter what will be mymark from this research, I do believe next year at someof the festivals, some rides are going to be free forthe children in Greenwich.

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

Dedicated to my Daughters Gozde and Gonul…

1.0 Introduction

Community festivals are rapidly growing in recent years

(Lee and Kyle, 2014; Yoon et. al., 2010; Delamere et

al., 2001; Getz, 1997; Jamieson 2006; Neirotti, 2003;

Prentice and Anderson, 2003; Mayfield and Crompton,

1995; Van Zyl, 2006). The community festivals which were

included in the scope of this study were mainly

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

organized by the volunteers. Because of the nature of

community festivals; the organising committee is

predominantly composed of members of the society (Getz,

1993; Meyer and Edwards, 2007). Local festivals also

described as celebrations of community or “what a

community is all about” (Janiskee and Drew, 1998 cited

in Lee et al., 2009:588). However, the community

festivals management committees face with different

constraints while the events are operating (Meyer and

Edwards, 2007). Moreover, measuring the attendees’

satisfaction is crucial (Lee et. al., 2008), to retain

the attendees (Kim et al., 2010).

Community festivals are aimed at improving community

cohesion, and sometimes authorities organise community

festivals to reach this aim (Jepson et al., 2008). While

local bodies organize this type of event, volunteers

organise independently or semi-independent festivals for

the same purpose. The previous finding in this area is

very narrow (Meyer and Edwards, 2007). However, the

community festival literature mainly investigated

different issues relating to the community Festival;

attendees’ satisfaction which is mainly related with the

marketing and the loyalty (Gursoy et al., 2004; Lee et

al., 2008; Yoon et al., 2010; Kim et al.,2010; Drengner

et al., 2012; Rosenbaum et al., 2005), impacts of

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

community festivals (Delamera, 2001; Delamera et al.,

2001; Small 2007; Wood 2005, 2009; Reid 2007;) and

volunteers (Meyer and Edwards, 2007; Earl et al., 2005;

Cleave and Dorothy 2005; Brennan 2007; Love, 2009;

Downward and Ralston 2005; Baum and Lockstone 2007).

Furthermore, community festivals are recognized by some

of the authors’ within the literature relating to event

tourism because the major driving force for the event

industry is tourism (Getz 2008). Conversely, in the

literature some of the other authors’ such as Clarke and

Jepson (2011) and Meyer and Edwards (2007) researched

community festivals relating to the community

development.

These types of events allow residents to engage with

their community and provide entertainment for a wide

variety of age groups and all community members who have

children or are alone, who are disabled or healthy, and

who are have a religious faith or are atheist. From this

viewpoint community festivals are a way to bring

residents to one place, improve community cohesion,

create an impact on communities while the residents are

entertained and promote governmental or local business

services.

This study focuses on free entry community festival

attendees’ satisfaction and organizers challenges and

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

capacities. In this research there is an emphasis on

volunteer community festival organizer’s challenges and

the study attempts to measure attendees’ satisfaction

related to the organisers’ challenges.

1.1 This Study Aims and Objectives The main aim of this study is to identify impacts of the

organisation on attendees’ satisfaction at the local

community festivals and predict future improvements for

the organisations and on the attendees’ satisfaction.

The hypothesis of this research is sought that

attendees’ satisfaction is dependent on organisers’

challenges and capacity.

Objectives

To determine differences of the aim at the

community festivals dependent on organisation

The community festivals are organised mainly for

community cohesion and promote local services purposes

by the local governments. However, independent volunteer

organisations also organise community festivals. The

community cohesion is main aim. However, there are

variant aims and power of the festivals dependent on

organisations capacities. This study investigated

different organiser’s aims and perceptions of the

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

community festivals by the organisers, festival goers

and the local authority.

To investigate volunteer management constraints and

capacities at the community festivals

The volunteers’ community festival organisers are

struggle with different challenges related with

organisation capacities. However, there is no obligation

to manage community festivals in the legislations. This

study argued impacts of support and the existing gaps in

the legislations.

To analyse factors of the attendees’ satisfaction

at the community festivals

Measuring festival attendee’s satisfaction is essential

(Gursoy et al. 2004; Lee et al., 2008), as with many

industries, because satisfied customers are more likely

to attend subsequent festivals (Lee et al. 2008; Kim et

al., 2010). The previous researchers’ findings show

there is a strong relation between a customer’s decision

to revisit the event and satisfaction with the existing

event (Lee and Kyle 2014). Segmenting the attendees

provide understanding the attendees attitudes and

perceptions.

To predict future improvement for the attendees

satisfaction

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

A community festival has no wide media coverage and

economic impacts (Getz 2008) and none of the existing

research has been conducted on the impacts of the

organisations capacities and constraints on attendees’

satisfaction. This study examines attendees’ attitudes

and perceptions related to demographic segmentations on

satisfaction, and defined improvement topics for the

future community festivals.

To determine the organizers’ improvement concerns

for the future community festivals

Whether organised by volunteers or local authority,

community festivals face with constraints. This study

analyses the limitations for the organisers depending on

organisational structure. The results suggest ways in

which future community festivals could be improved.

1.2 Background of the studyThis research particularly evaluated and focused on

three free festivals which do not have to be pre-booked

to attend. This provides an opportunity for the

attendees’ and the local residents to watch live

performances, access food stalls, entertainments,

children’s activities, arts and craft stalls,

information stalls and so on at the communal spaces.

These festivals are celebrated annually for members of

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

the community, at the same location and hence attract

mainly local people. Moreover, the festivals open to

everyone (include those from different ethnic

backgrounds and people of all ages), providing a range

of activities for different age groups all day long in

South East London.

For this research, data was collected for the attendees’

satisfaction at three different community festivals in

London in June 2014. The research result was verified by

255 survey respondents at three different community

festivals and four interviews were conducted to identify

the organizations’ constraints and capacities. The

Department of Culture, Art and Leisure, (2007) policy

posed; “A community festival is a series of events with

a common theme and delivered within a defined time

period. It is developed from within a community and

should celebrate and positively promote what the

community represents. Community festivals are about

participation, involvement, and the creation of a sense

of identity and are important in contributing to the

social well-being of a community”.

1.3 Justification of the Study

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

The four community festival organisation’s assignees

were interviewed for the purpose of discovering the main

challenges that organisers experienced in South East

London and measured the factors of attendees’

satisfaction at these local festivals. Those annually

community festivals celebrate and entertain residents.

The reasons to focus on these topics were; these

festivals are also organised by volunteer community

groups. The governmental bodies are promoting grants and

training availabilities for the volunteer community

festivals committee at the London Community Foundation

(2014). Conversely, none of the training is mandatory

for being able to run community festivals in London,

moreover, some festivals are failing. Examining the

impacts of these constraints and capacities of the

organisations on the attendees’ satisfaction becomes

more important for understanding the attendees’

attitudes and understanding the organisers’ desires for

potential improvements at future festivals. Nonetheless,

the overall satisfaction at these events was compared to

identify the attendees overall satisfaction at various

community festivals included in this study.

1.4 Conclusion of Introduction

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

The impacts of the organisational challenges and

capacities factors of attendee satisfaction of local

community events will allow the organisers to predict

future improvement on attendee satisfaction,

strengthening their awareness of ways to overcome

volunteer constraints. Volunteers for the community

events are an important element of the social changes

(Brennan 2007), volunteers give their time, skills and

effort without monetary expectations (Meyer and Edwards

2007). In this study the researcher sought to identify

impact of the organisational challenges on attendees’

satisfaction at the local community festivals and

predicts future improvements for the community

festivals.

The research outline was designed as follow: In the

literature review a critical analyses was conducted for

several of the topics, relating to community festivals,

volunteer management constraints and capacities. The

attendees’ satisfaction reviewed with the different

authors’ arguments. The purpose of this was to

strengthen this study. Methodology chapter summarizes,

detailed research methods, which this study conducted

for meeting the aims. Furthermore, other available

methods are discussed and explained with reasons for not

using these options in this study. The following chapter

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

aims to demonstrate the findings of this research, the

attendees’ satisfaction results and the interviews

presented in this chapter. In the concluding chapter all

previous sections are reviewed and recommendations

offered for the future research.

2. Literature ReviewThe scope of community festivals literature review is

narrow (Meyer and Edwards, 2007). There have been

several researches made about volunteer community

festivals (Meyer and Edwards 2007; Huang et al., 2010;

Clarke and Jepson 2011; Jepson et al., 2008), impacts of

community festivals (Wood; 2005, Delamera 2001; Delamera

et al., 2001; Small, 2007; Wood, 2009; Gursoy et al.,

2004), evaluation of attendees satisfaction at festivals

(Yoon et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2010)

and Festival volunteers (Meyer and Edwards 2007; Earl et

al., 2005; Cleave and Dorothy, 2005; Brennan, 2007;

Love, 2009; Downward and Ralston, 2005). In this chapter

the literature review enhanced with these authors’ among

many other authors. Literature review consists of the

three main topics; Community festivals included;

definitions of community festivals, aims and perception

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

of community festivals, impacts of the community

festivals and issues related with community festivals.

Next topic investigated the volunteer management

constraints under; the definitions of volunteer and

volunteer constraints. And the last section of the

literature review discussed, attendees satisfaction

under the topics of, importance of measuring attendees’

satisfaction, attendees’ reasons to attend community

festivals and factors for attendees’ satisfaction.

2.1 Community Festivals

2.1.1. Definitions of Community FestivalsCommunity festivals or as O’Sullivan and Jackson (2002)

described “home grown festivals” are not researched yet

(Li et al., 2009). Allen et al., (2007:50) described;

“festivals and events can be identified in every human

society in every age. They are part of how we interact

as humans, and form part of the social fabric that binds

our communities together”.

However, O’Sullivan and Jackson (2002) posed home grown

festivals are been organised in rural or semi-rural

areas. Furthermore, festival is a way to develop

networking between across sectors (Jepson et al, 2008)

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

and promoting ethnic differences in doing so revealing

local cultures, customs and history (Jepson et al, 2008;

Getz 1997). Love (2009:3) posed “festivals are important

part of the overall economic exchange for the arts and

cultures industry”. Nonetheless, Quinn (2005), cited

culture is used for restructuring prosperity and job

creation thorough the use of festival.

Different definitions and perceptions of community

festivals are emerging in the literature about what

about festivals are? However, the common theme among

some authors about the festival is people’s Culture

(Quinn, 2005). Clarke and Jepson (2011) posed; culture is

used for constructing festivals for the societies and

also the main decision maker for the community to

include or exclude the festivals. Moreover, Getz (2008)

classified, festival industry along with carnivals,

commemorations and religious events under cultural

celebrations. Art and entertainment are another

classification on the Getz typology of planned events.

The main distinction between Getz (2008) and Love (2009)

descriptions is Getz classified festivals under cultural

celebrations whereas Love classified the festival

industry under the arts and culture industry.

Jepson et al (2008:7) posed; “festivals and moreover,

community festivals are public themed celebration which

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

can act as a catalyst for demonstrating community values

and culture”. It is important to investigate why

festivals are organized; Mayfield and Crompton (1995)

enriched literature with their findings and the authors

classified eight main reasons why festivals are

organized, these are; internal revenue generation,

external revenue generation, community spirit and pride,

culture/education, tourism, agriculture,

socialization/recreation and natural resources.

2.1.2 Aims and Power of Community FestivalsCommunity based festivals have diverse varieties of

themes and aims (Huang et al., 2010). Quinn (2005:6),

stated; “the first festival took a place in Athens as

long as 534 BC, in honour of the God Dionysos, the

patron of wine, feast and dance”. Community festivals

are used for many other purposes, educational,

religious, private, public purposes and so on (Quinn

2005). Furthermore, opens spaces, free spaces or Public

spaces also provide opportunity for the community to

learn from others how to behave, respect and many other

aspects for communal living requirements (Poletta,

1999). Nonetheless, usage of parks is becoming a

phenomenon of increasing neighbourhood quality and

attracting low-income communities and increasingly

middle-income residents (Walker, 2004). Hart (1997)

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

posed adequate parks are environmental educator for

children.

The historic community festivals were used as a

political purpose to control the societies (Jarvis

1994). Wood (2005) highlighted local bodies that

utilised the events and festivals to reach various

ranges of economic and social objectives. While interest

in community festivals is increasing in London and the

main aim is to increase the cohesion between residents,

local authorities used funding for running these events

(Wood, 2005) and these festivals contributed to the

essentially well-being of societies (Arcodia and

Whitford, 2007). Festivals are a place where different

voices represent themselves and it is also a place to

manage the tension of generated differences (Derret,

2005). Moreover, at the festivals, attendees’ celebrated

their society identities (Turner, 1982; Gursoy et al.

2004). Attendees attend particular community festivals

to build up bonds with their society (Wood 2005; Gursoy

et al., 2004; Dalemera, 2001; Turner, 1982). The way of

engender local permanency (Quinn, 2005). Furthermore,

Jamieson (2006) stated Community festivals improve

cohesion between local residents which need to be under

control of their local community; author added;

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

community festivals need to give opportunity to the

local residents to represent others in their community.

The governmental body organise these types of festivals

to create consensus between local residents (Mayfield

and Crompton, 1995), increase social pride and for

community well-being. McMillan (1996:322) stated; “to

have experience, the community members must have contact

with one another. Contact is essential for a sense of

community to develop”. Furthermore, the community

festivals increase civic commitments and morale (Wood,

2005). Wood (2009) investigated the local authority

management festivals and posed the need of clarity

within local government and the author proposed the

government needs to focus and be serious about what the

attendees’ expectations are, when they use public funds

as a return of investment to the community.

2.1.3 Impacts of Community FestivalsMany authorities agreed these types of festivals are a

different, valuable approach to improve identification

and commitment-centred, common values (Lee and Kyle

2014). Wood (2005) describes how the importance of scale

impacts of the festivals. The author investigated

attendees’ motivations and attitudes to measure the

economic and social impacts of the festivals. Delamera

(2001) questioned the Local bodies, the local

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

communities and the festival organizers perception on

festival is it to predominantly gain on economic

benefit? However the impacts of each event are variable

(economic, environmental, social) depending on the

local, national and international concept (Wood 2009).

Furthermore, Saayman and Saayman (2006) found that the

location and size of the town had a significant

influence on the event. Many studies focused on

economic impacts to measure success of the event and a

few of the researches focused on the socio-cultural

impacts. This is the reason why the success of the

festival is measured by the financial contribution to

the stakeholders (Small et al., 2005). Furthermore,

Jepson et al. (2008) added without community festivals

local communities cannot achieve involvement of the

population.

Small (2007: 45), explored six dimensions of social

impacts of community festivals. The factors listed as a;

inconvenience, community identity and cohesion, personal

frustration, entertainment and socialization

opportunities, community growth and development and also

behavioural consequences. Prentice and Anderson (2003)

and Reid (2007), findings have also raised the

importance of social impacts and consequences of the

local events. Delamera et al., (2001) investigated

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

social impacts under social benefit and social cost

which is less tangible than economic impacts of

community festivals.

2.1.4 Issues Related with Community Festivals ManagementConversely social benefits of the community festivals,

there are different issues in the literature that is not

commonly in the scope of the research. Jepson et al.,

(2008) posed festival process; develop organisers’

hegemony over the other shareholders and the author

argued about consistently running festival by the same

organiser is not encompassed within the democracy.

Moreover, it is arguable to identify how community

festivals which are steering with the same committee

over the years can be efficiently to represent multi

ethnic communities. Moreover, festivals are going to be

limited to the views of the steering community’s

cultures over the years (Clarke and Jepson, 2011).

Clarke and Jepson (2011) evolved the hegemony of the

steering group at the community festivals related to the

limited resources, the authors added all supports and

consultation meeting are provided in English Language.

This is not allowing non-English speakers to participate

at the organising committee meetings. Other issue

relating to community festivals management is the

financial difficulties which results in insufficient

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

promotion and unproductive marketing research that lead

to events failing to reach target audiences at the

community festivals (Lee and Kyle 2014; Getz, 2008).

However, developing marketing strategies and

coordinating the festival is a responsibility of the

festival expert. Organisers captivate cultural control

of a community festival (Jepson et al., 2008). In

contrast, some event organisers are against the idea of

running community festivals which develop business

approaches at the community based festivals. Because of

reduce the demand from community involvement (Gursoy et

al., 2004). Brennan (2007) suggests investigating to

community resources, enhanced venues for interaction and

increased community capacity building.

The festival and event evaluation kit was developed by

the cooperative research centre for sustainable tourism.

Four sections identified; Demographic Module which is

assessing demographic structure of the area, Economic

module that calculated expenditure and incomes of the

festival, Marketing Module which was scope marketing,

related concerns asking questions for the participants

and getting feedback about motives for attending the

event and the last section is additional questions

module that is collecting data (Allen et al., 2008).

Getz (2008) emphasized the nature of the event that is

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

time limited and the author added (2008: 404) “if you

miss it, it’s a lost opportunity” and then the

researcher clarified the importance of satisfying the

goals at the event industry and the author cited, if the

amateurs are run event this is often too risky for

reaching the event goals. Moreover, Jepson et al.,

(2008) defenced successful community events, in other

words community events which reached their targets is a

consequence of organisation, networking and management.

However, Jamieson (2006: 182) explored the importance of

management structure and the author posed “festivals and

events rely on enthusiastic participation, event

planning does not work best with “top down” management

approach that tries to impose practices onto a

community, region, or institution”. Moreover, Wates

(2008) suggested standard organisational structure for

the successful community festival; the author included

local interest groups, consultants and support bodies in

the main organisation framework. Nonetheless, Huang et

al., (2010: 259) posed; “festival organisers, planners

should encourage local people to support community based

festivals and project the image of a friendly community

to the family market”. In contrast Kim et al., (2010)

cited, this type of local community festival success

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

depends on the organisers and local residents’ passion

for the event.

2.2 Volunteer Management Constraints and Capacities

2.2.1 Definitions of volunteerBaum and Lockstone (2007) defined the volunteers;

“individual volunteer helping others in sport, informal

organization such as clubs or governing bodies, and

receiving either no remuneration or only expenses”.

However, volunteering.org.uk (2014) definition is

slightly different than the aforementioned definition

“volunteering as any activity that involves spending

time, unpaid, doing something that aims to benefit the

environment or someone (individuals or groups) other

than, or in addition to, and close relatives”. Central

to this definition is the fact that volunteering must be

a choice freely made by each individual. This can

include formal activity undertaken through public,

private and voluntary organisations as well as informal

community participation (Volunteer. Org. UK, 2014). One

of the other definitions cited Du Boulay (1996: 4) “a

volunteer is a person who, on a regular basis,

contributes his or her time and energy”. There are

existing gaps even for the definition of the volunteer

in the literature (Baum and Lockstone 2007).

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

Furthermore, in the legislation there is no any

obligation for the employees to pay volunteer expenses

(Volunteering.uk.gov, 2014).

Community festivals are labelled as a community based on

being run by one or a group of volunteers for advantages

of local residents (Huang et al., 2010; O’Sullivan and

Jackson, 2002). Stebbins (1996) posed; volunteering is

more enjoyable and satisfying, however, it does not

require skill or knowledge. However, Baum and Lockstone

(2007: 33) argued against Stebbins definition and the

authors are defined in the Stebbins definition; “the

definition does not sit well with the skills base often

required or acquired as a result of this of

participation”. Furthermore, Stebbins cited, (2004: 7)

“volunteering, considerable planning, effort and

sometimes skill or knowledge, but is for all that

neither serious leisure nor intended to develop into

such”. Davis Smith (1999) recognized five major elements

for volunteering; rewards, free will, benefits from

volunteer activity, organisational brand, the level of

commitment of volunteers. However, emotional attachment

is one of the key motivation factors for volunteers to

work for the particular festivals (M. Thompson & Heron

2005).

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

2.2.2 Volunteer constraints and capacitiesIn the literature of the community festival industry

volunteer constraints are not widely scoped (Meyer and

Edwards, 2007). Love (2009) has researched about

community events and volunteer impacts. Moreover,

volunteer constraints at the festivals related

literature investigated by Cleave and Dorothy (2005),

Brennan (2007), Love (2009) and so on. It is important

to understand the volunteer’s needs and expectations

prior to the event to maximise utilisation of a

volunteer’s time and effort (Downward and Ralston 2005).

At the community involved events, individual

contributions create a long term community (Brennan

2007). Cleave and Doherty (2005), research findings

(from 2001 Canada Summer Games) show volunteers

negotiating with the challenges, however, the same

challenges are not overcome by non-volunteers such as

personal cost, lack of skills, language ability and so

on. Earl et al., (2005) urged a capacity of volunteers

at two different levels; as a group and an individual.

The authors increased awareness of the training needs,

how often, and what position festival organisers

utilised from volunteers, in crowd management, campsite

management, entry and exit control and so on. Brennan

(2007) proposed improvement needs of volunteer on

empowerment, training, support and program development.

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

Volunteer training, through academic, private and

governmental bases would support enabled local

communities into active community leaders (Brennan 2007)

as well as increase capacity and quality of the events

(Brennan, 2007). Furthermore, Earl et al., (2005)

explored how expanding volunteer capacity through

training had a positive effect on the volunteer service

for the authors’ study of the festival. Within this

frame, training and support increases the capacity of

the organisers and simultaneously, increases capacity

and quality of the festivals. Volunteers have positive

impacts on improving the community, individual

volunteers working together with other community members

and build a social network (Cleave and Dorothy, 2005).

Nonetheless, training increases the confidence of the

volunteers for the potential for recruitment (Downward

and Ralston, 2005).

Brennan identified volunteer needs under enhanced or

increased venues for interaction, broad based local

representation, leadership development and increased

skills based training. Instead of conflicts between

community members, distrust, different interest and

variety of other negative conditions. However, the

differences between community members are still not the

barriers to empowering community development (Brenan

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

2007). The aims of the festivals are communities

celebrating a variety of nations and enhanced values of

life (Quinn, 2005). Department for business innovation &

skills defined there is no department in Government

leading and responsible for volunteer events. This site

posed organisers need to review the local authorities

rules and regulations for organising the volunteer event

(Gov. UK, 2014). The site is added, “The value of the

volunteers is in Government big society agenda”.

The community festivals have a real potential to

generate socio-cultural impacts (Small et al., 2005).The

volunteer organising committee serves to community and

have a power to promote what they would like to or

protest during stage performance. The question arises

about whether volunteers are vetted (Baum and Lockstone

2007). Getz (2002) identified the main constraints

perceived by the organisers is the retention of the

volunteer. Love (2009:5) posed “gaining better

understanding of how to improve volunteer retention is

important for the management of non-profit festival

organisation”.

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

2.3 Attendees satisfaction

2.3.1 Factors for attendees’ satisfactionLee et al., (2007: 402) posed for the satisfaction; “it

describes a consumer’s experience, which are the end

state of a psychological process”. In growing festival

industry, understanding festival goers will improve

marketing and festival production (Li et al., 2009). The

authors’ explored six motivational factors at the

festivals in their research; escape novelty, nostalgia

and patriotism, event excitement, family togetherness

and Socialization. Between six different factors escape

found most dominant factor. In spite of festival

popularity many festivals failed because of insufficient

marketing and limited budget (Lee and Kyle, 2014). Lee

and Kyle segmented festival goers based on the attendees

commitment degree and then in socio-demographic

characteristics. The authors posed their finding at the

three different segments; age, education and past

experience and the findings were meaningful and had

significant variation. Moreover, the authors added

(2014: 656) the “more committed visitors were to the

festivals, the higher their overall satisfaction was

with the festival experience, and the more likely they

were exhibit loyalty intension toward the festival”.

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

Yoon et al., (2010) stated, understanding customer

satisfaction and loyalty is as significant as product

quality. Researchers segmented tangible (food,

souvenir) and intangible benefits (festival quality,

loyalty, value and satisfaction benefits) of the

festivals and segmented gender, age, education level and

marital status. Research findings show (:335) “festival

quality dimensions included program, souvenirs, food,

and facilities affect value, which then contributes to

visitors’ satisfaction and loyalty.” Lee et al., (2007)

emphasized promotion, organization and management of the

value of the festival experiences, and the authors

discovered similar result with Yoon et al., (2010). Yoon

et al., found food quality and program content

positively affects customer satisfaction and is

satisfaction leads to customers being loyal to the

festival. Kim et al., (2010) suggested the importance of

facilitating quality services and valuable experiences

for the perception to repurchase the experience and

researchers categorized socio-demographic structure of

research responders. Moreover, Kim et al., findings

specified “perceived value leads to satisfaction”. Getz

(2008) considered possible measures of value the events

as follow; growth potential, appropriateness, market

share, sustainability, quality, economic benefit,

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

community support and image enhancement. The author then

separated these into four divisions; low and high demand

/ high and low value on his evaluation pyramid.

According to this approach local events (periodic and

one-time) are described as a low demand and low value

for the measurement strategy of the “value” for the

event industry.

2.3.2 Importance of measuring attendee’s satisfactionMeasuring the satisfaction of the attendees is crucial

(Kim et al., 2010; Gursoy et al., 2004). Satisfied

customers are more likely to revisit next year events,

in other word, are expected to utilise the same service

(Cronin et al., 2000). In the literature there are

different aspects to engender to attendees satisfaction

factors. Drenger et al., (2012) emphasises that loyalty

is the main driver of the satisfaction; the authors’

research on music festivals explored how the feeling at

being part of a community has a wider influence than

overall satisfactions the authors posed (: 59);

“satisfying the customer is not always the key route to

value creation”. Also the authors added customer

interactions improved the building of positive

experience. Moreover, festival satisfaction indicates

the festival quality (Yoon et al., 2010; lee et al.,

2008). Nonetheless discovering the motivational reasons

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

of the attendees was as inefficient way to measure

attendees’ satisfaction (Yoon et al., 2010).

Wood (2005) recognized vigorous data was a necessity for

planning future events and secures funding from funders.

The authors exposed, 100 per cent audience satisfaction,

moreover, the author added (: 48) “responders stating

they enjoyed the festival “very much” and none of the

responders added any negative comments or complaints to

the recorded assessment. On the other hand, demographic

factors analyses who are the attendees’. Mason and

McCarty (2006) posed; a young visitor feels that they do

not belong the organisation institutions.

2.3.3 Attendee’s reasons to attend community festivalsWoodruff (1997) emphasised the importance of past and

present experience of the value of the event and that

expectation is related with experiences. Prentice and

Anderson (2003) findings, define the experience of the

festival, as the most important reason and socialising

with friends identified, as the second most important

reason for the festival experience of attendees. Wood

(2005) discovered “doing something special” was the most

important factors for attending festivals as followed by

“relaxing entertainment”. On the other hand, repeated

visitors had more awareness than the first time

attending attendees. Huang et al., (2010: 259) exposed

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

“repeat visitors enjoyed the atmosphere of the festivals

and nice people of the host community, whereas first-

time visitors appreciated the tangible more than the

emotional elements”. The other factors which are described

by Lyon (2000); free events attract the most people and

are more popular than paid events; these types of events

generally include concerts, parades at the open spaces.

Moreover, Drengner, John and Gaus (2012) emphasis on

free events offering loyalty to the attendees.

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

3. Methods usedFor this study multi-methods were used to verify most

reliable data and reach the most appropriate result.

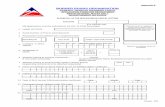

3.1 Multi-Methods and Analysis Table

Below table demonstrated methods used for this study Datacollectiontechniques

Theaspects oftheory

Researchapproach

Nonprobabilitysampling

Probabilitysampling

Purposeofresearch

Quantitative

Deductive

Pragmatistapproach

Purposive

Simplerandom

Descriptive

Survey Snowball Exploratory

Observation

Explanatory

Contentanalyses(Photographs,books,newspaperand soon)Semi-structurequestionnairesSPSS

Existingstatisticsresearch

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

Secondaryanalysis/DataQualitativeObservation

Inductive

Informal,semi-structureinterviewsOpenendedquestions

The festival attendee’s satisfaction data was collected

at the three study sites to measure their satisfaction.

One of the other main resources of this study was the

four organiser’s assignee interviews. The organiser’s

challenges and capacities emerged in detail during these

interviews. In total five community festivals were

included this study. The Royal Borough of Greenwich

(RBG) Deputy Leader represented the local body community

festivals organiser and this interview allows the reader

to explore aims of the local authority festivals’ and

the attitude of the local authority to the community

festivals. Furthermore, one of the festivals was in the

Lewisham Borough, this enables the reader to identify

differences between the two different Boroughs. This

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

research resource includes the many different authors’

academic books, journals, and articles, moreover,

utilised from the secondary data such as census, web-

sites and the photographs taken from the observed

festivals, in addition to primary data from interviewees

and the attendees’ questionnaires.

3.2 Research ApproachThe research was conducted using different approaches

for meeting the most appropriate result of study.

Different perspectives were established during this

study, and allow the reader different views from

different organizational structure. Using multi-methods

refer to pragmatist approach where quantitative and

qualitative data analysed together (Kelemen and Rumens,

2007 and Creswell, 2003). The qualitative approach used

during the interview and part of the attendees’ survey,

when asking attendees most enjoyed activities and

recommendations (Dewhurst, 2006; Berg, 2007). Part of

the survey allows readers to analyse numerically

presented statistical data relating to the attendees’

satisfaction (Neuman, 2007; Bell, 2010). This part of

the research allowed the researcher to develop data

faster with closed questions (Berg, 2007). The overall

findings can be easily compared with different data from

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

the other similar studies. In this study, the researcher

was a physical component that might impact on the result

of the research. Moreover, the study used quantitative

research during spontaneous interviews and sought

answers with inductive analyses for the purpose of “…

involving the intensive examination of a strategically

selected number of cases so as to empirically establish

the causes of a specific phenomenon” as Johnson cited in

Cassel and Symon (2004: 165). During the interviews to

uncover fundamental meanings and governments’ judgement,

multi-method analysis connections and the impacts of

interaction searched for dynamics (Walliman, 2011).

3.3 Research DesignQualitative data collection conducted for analysing the

community festivals organiser’s constraints and

capacities. In depth interviews, photographs,

observation provide gathers and analyses data results

and considered correlation among the concepts, at this

part of research inductive method used. Research

conducted mainly quantitative data collection on

attendees’ satisfaction. Quantitative data collections

allow to reach larger population of responders easily

compare with other data’s for attendees’ satisfaction.

Conversely, qualitative data allow to used exploratory

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

research and results were difficult to duplicate.

Dependant to the interviewee the researcher easily

changed the direction to find out relevant information.

Neuman posed (2007: 115) “reliability means

dependability and consistency” and the author defined

“validity suggest truthfulness and refers to match

between construct, or the way a researcher

conceptualised definition, and a measure. The author

added; “perfect reliability and validity are virtually

impossible to achieve”.

3.4 Research MethodsThe qualitative method was used for understanding the

challenges of the organisers. The four community

festival organiser’s assignees were interviewed without

the questions being decided before the interview.

Similar questions were asked of the organisers because

of the similarities of their responses. Furthermore, all

festivals included in this study were observed. Finally

secondary data was used such as news and pre-existing

ideas within the local press about the festivals, and

the census results of the area examined for the purposed

of developing the data (Neuman 2007).

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

This research was based on survey responses from

attendees of the three local community festivals. The

researcher conducted questionnaires individually within

the attendees who agreed to be part of the research. The

attendees’ questionnaire includes many closed questions

and two open questions, these were; recommendations,

suggestions and what activity during the festival

attendees enjoyed most. That two open questions were not

employs statistical and mathematical concept (Dewhurst,

2006), because of this reason, these questions represent

qualitative methods in the attendees’ survey. The survey

required approximately five minutes of the festival

attendees time. Furthermore, the research required an

interview with the organisers to evaluate organisations

aims and identify challenges, capacities and the

organiser’s experiences during the organisation of the

festival. The interview was conducted wherever the

organiser preferred and voice recorded. The interview

was conducted one week after the festival date. The

primary data reflected on the research from survey and

interview results. The multi-methods data was gathered

to understand different aspects before judging the

responses. Moreover, conducting qualitative data to the

festival goers were vastly difficult because type

recording would not be audible at the festivals. Because

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

festivals entertained attendees with live music and

there was dominant background noise from the crowd.

Qualitative researches involve longer time consumption

than quantitative (Dewhurst, 2006). In addition,

conducting the interview with approximately hundred

responders at each festival, in six hours’ time limit

would have been almost impossible.

3.5 Sampling StrategyThe attendee’s satisfaction part of this study was

conducted using the quantitative approach and the

primary goal was to reach large amount of responder

(Neuman, 2007) and simple random probability sampling

was conducted whereas select responders purely random

process (Neuman 2007) for the part of measuring

attendees’ satisfaction. Any festival goer was regarded

as a potential survey responder. Attendee’s population

elements were non-zero or every attendee had an equal

chance of being a responder (Brotherton, 2008).

In contrast to probability sampling, non-probability

sampling was conducted for the interviews during which

the researcher was not able to control who was going to

be interviewed (Berg 2007). The purposive type of sample

was applied; the main principles for this part of the

research "all possible cases that fit in particular

criteria” (Neuman 2007: 141). However, to enhance the

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

research, the researcher decided to investigate semi-

independent volunteer festivals aim, experiences,

capacities and constraints after the RBG event team

suggestion. At this part, the snowball samples were

involved and the interview was conducted by referral to

the one interviewee (Neuman 2007). One of the other

possible type of sampling is haphazard sample which is

any cases chosen that is convenient for the research.

However, this is more biased and in this sampling it is

not necessary to fit the particular criteria of the

research.

The four interviews conducted, one of the interviewee

was chosen from Lewisham Borough. Furthermore, one semi-

independent (run by volunteer, however, festival

expenses are paid by the local body) organiser assignee

from the RBG area was interviewed to identify

independent volunteer semi-independent festivals aims,

experiences, constraints and capacities. Finally the

researcher interviewed the Deputy Leader of the RBG

Council to include local authority aims and views to the

local community festivals. The post-festival surveys and

post interviews allow the readers to access the

capacities of the festivals and challenges, which

organisers faced before and during the particular

festival.

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

30.000 estimated residents attended the Great Get

Together and Armed Forced Day (GGT) according to The

Telegraphs and Argus (2014), 7.000 people were estimated

to have attended to the Plumstead Make Merry Festival

(PMM) estimated information by local police from

interview with the organiser and Brockley Society Mid-

Summer Fayre (BSMSF) organiser estimated 3000 people

attended their festival. The 269 Festival goers’

responded to questionnaires, 6 responders were under 18

years old and 8 responders did not complete

questionnaire. 255 surveys were accepted as completed of

surveys for this research. This number 255/50,000

considered 0.63% of the total festival goers at the

three included festivals studied.

3.6 Instrument DesignMainly, closed questions were asked of the festival

goers. The attendees’ survey asked some questions to

identify socio demographic population of the attendees

these questions were; age, revisit and residential

status. Latter were asked attitudes and perceptions of

attendees, including community support/ meeting new

people/ meeting old friend /willingness to pay/ do food

encourage to attend/ do feel secure at the environment/

friendly service at the festival. Some of the other

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

questions analysed marketing impacts; where attendees

had heard about the festival/ freebies impacts to attend

festival and do know who are the organisers.

Furthermore, three questions asked the purpose of

recognised attendees’ satisfier. Interval scale was used

to identify the overall enjoyment and two open questions

asked to the attendees for their recommendations and

most enjoyed activities they involved with during the

festival. A result of survey generalises with overall

attendee’s satisfaction. Also, deductive methodology was

applied to that part of research. However, open

questions and interviews were inductive, that might lead

the researcher to find new definitions of the community

festivals. Questions from interviews were spontaneous

(Buckingham and Saunders, 2004; Bell, 2010). The

interview structure and the questions were changed

depending on the interviewee response.

3.7 Data Collection TechniquesThe Royal Borough of Greenwich website was used to find

festivals through the organisation events list for the

most appropriate festivals for the study criteria. Two

community events were found which were suitable for this

study at the local body website. The researcher

contacted the organisers, informed them about the

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

research and requested to conduct on interview with one

of the organiser. The Plumstead Make Merry (PMM)

Organiser accepted. However, the Great Get Together and

Armed Forced Day (GGT) Organiser; Local Authority Event

Team did not agree to be part of the dissertation

because of having insufficient resources. The GGT

organisers suggested the researcher to communicate with

the PARKSfest organisers for this study. The PARKSfest

organisers agreed to be part of this research.

Furthermore, the researcher asked the GGT organising

team permission for survey, the team did not respond but

the researcher conducted survey with the attendees on

the festival day. Then research was developed wider to

discover volunteer challenges and analysed attendees’

satisfaction in the different Borough in London.

The first surveys conducted on 7th of June 2014 at

Plumstead Make Merry, 101 useable surveys were completed

on the day. The second survey was conducted at Brockley

Mid-Summer Fayre, 100 useable surveys accomplished on

21st of June 2014. Finally festival goers answered the

survey at the Woolwich Great Get Together & Armed Forced

Day on 28th of June 2014, 54 usable attendees’ responded

collected. Before attendees answered the survey the aims

and objectives of the research was explained verbally.

Nonetheless, each survey contained a small explanation

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

about the research. However, research aims and

objectives were provided with more details in written

form on A4 paper for any further information request

from any attendees. The Interviewees received the

consent letter before the interview has conducted and on

the interview day a copy of the consent letter has

provided for the interviewee. All interviews were tape

recorded. The Plumstead Make Merry organiser (on 11th of

June) and Brockley Society Hilly Field Mid-Summer

organiser (on 27th of June) preferred to use their house

for the interview. The PARKSfest organiser (on 13th of

August) preferred the South Eltham Park Cafe where one

of the PARKSfest events was celebrated. Finally the

PARKSfest festivals creator Deputy Head of Council John

Fahy responded the interview request and invited the

researcher (on 19th of August 2014) to the councillor’s

formal office at the Town Hall.

3.8 Method analysisThe results of this study emerged as able to be used

with a variety of research methods. For the festival

goers satisfaction; mean, descriptive, correlated and

frequencies analyses used at the raw data in the

Statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS). For

the quantitative part of the attendees’ surveys two

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

different subtitles emerged after analysing the

responders; most enjoyed activities also their

recommendations, comments and suggestions. At the

qualitative part of the research interviews conducted,

similar questions were asked of the organisers during

the interview. However, to identify local body aspects

for the local volunteer festivals different questions

applied to the Councillor. Each answer segmented in a

different topic and analysed the common points and

differences between organisers.

3.9 Discussion of this study ethical considerationThe organiser’s participation was completely voluntary

and a letter of consent was signed before the interview

started. The consent letters contained brief

instructions about the topic, aims and objectives of

this research and the confidentiality was explained in

the consent letter. All relevant documents and raw data

are kept at the researcher’s locked office.

3.1.1 Limitations of MethodologyThere are some limitations to this study; One of the

limitations was responders had answered the questions

for the festival they attended on the day. None of the

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

responders were asked questions about their previous

festival experiences or level of satisfactions. The

other limitation of this research; requires the time of

the organiser who takes part of an interview and

discussion about the problems that they encountered

before, during and after the festival. Some of the

organisers refused to being part of this research

because of they didn’t have enough time resources for

the interview. One of the religious festival organiser’s

requested one to one assessment before confirming

availability to be interviewed, and three different

festival organisers did not respond to emails regarding

the survey and interview request. One of the other

limitations was; at this type of festivals, the attendee

profile is more likely to be a local resident who would

like their family to share family experiences (Small,

2007) from where the festival was organised. Because of

this, some of the attendees refused to be part of this

survey for their children safety, even for the five

minutes the survey would take. This could be a barrier

affected children’s safety. Some of the attendees

refused because they were sun bathing, eating or having

conversation with their family or friends.

The attendees’ satisfaction survey was conducted with

anyone, who could communicate verbally in English or in

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

Turkish Languages. In contrast community events are a

good way to break isolation and increase socialising

(Small, 2007; Reid, 2007; Wood, 2005) for the whole

community. The people who were not able to speak in

English or Turkish were not represented in this research

result. Also, people with severe mental health problems

were excluded from this research beside people under the

age of 18. The researcher did not ask the responders for

ID, however, at the survey, first question was asked

responder’s age group and any attendee’s under the age

of 18 were excluded from the survey. A Royal Borough of

Greenwich Councillor took a part at this study however,

each local authority has different legislations and

criteria for volunteer community festivals as well as

many similar legislations. The RBG represented their

thought for Greenwich. Moreover, the researcher has not

conducted other interviews with the other borough

councillors.

Finally the organisers’ capacities and constraints

measured through interviews with the organisation’s

assignee, for each festival was included in this study.

However, despite all volunteers’ efforts, these

festivals are created and displayed through committee

members and volunteers’ time, skills and efforts. This

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

research did not investigate committee members and other

volunteers’ experiences at the festivals.

3.1.2 Conclusion of the Methodology ChapterThe aim of this study was to seek and identify; the

impacts of the organisers challenges on attendees

satisfaction. A variety of stakeholders were identified

and the most appropriate methodology conducted for the

most reliable results. The study conducted different

approaches for different stakeholders; multi-methods

were applied to this study. First main stakeholders for

this study were attendees and for measuring their

satisfaction the quantitative and qualitative approach

was conducted. Five questions were on nominal scale, one

question was on ordinal and one question was on ratio

scale, 7 multiple questions were on (equal) interval

scale and 2 open questions were asked. Second main

stakeholders were; the organisers and quantitative

approach used; interviews conducted, similar questions

asked and interviews were semi-structured. The

Councillor’s interview identified aspects of volunteer

community festivals. Moreover, secondary data; the

census result, local magazines, website and so on were

explored. Finally two semi-independent community

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

festivals were observed to raise reliability and

analysed wide variety of views.

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

4.0 RESULTS AND ANALYSIS In this chapter, the results are presented; the 255

responders’ satisfaction surveys and four in depth

interviews with the festival management committee

assignees and some photographs are presented. The

provided information demonstrates efficacy of the data

gathered. Moreover, readers are able to see a discussion

of results supported by existing literature.

4.1 Data Results for Attendees’ SatisfactionCommunity Festivals Research Data– South East London 2014

N = 255

Below tables demonstrate 255 festival goers’ responses

at the three festivals in South East London 2014. 101

useable questionnaire collected at Plumstead Make Merry

(PMM), 100 useable questionnaire collected at Brockley

Society Mid-Summer Fayre (BSMSF) and 54 useable

questionnaire collected at Great Get Together and Armed

Forced Day (GGT).

Demographic Perceptions

Marketing Satisfier

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

Questions & Questions

Questions Attitudes

Result All PMM %(n= 101)

BSMSF %(n = 100)

GGT &(n = 54)

Demographic

Q1. Age? 18-28 years= 43(16.89%)29-39 years= 97 (38%)40-50 years= 67 (26.3%)51-59 years= 31(12.15%)Over 60 =17(6.66%)Totalresponse:255 (100%)

18-28 years =25 (24.8%)29-39 years =36 (35.6%)40-50 years =17 (16.8%)51-59years=15(14.9%)Over 60 years=8 (7.9%)Totalresponse: 101(100%)

18-28 years= 15 (15%)29-39 years= 44 (44%)40-50years=31 (31%)51-59 years=6 (6%)Over 60years =4(4%)Totalresponse =100 (100%)

18-28 years =3 (5.6%)29-39 years =17 (31.5%)40-50 years =19 (35.2%)51-59 years=10 (18.5%)Over 60 = 5(9.3)Totalresponse = 54(100%)

Q2. Areyouresident?

Yes=155(60.8%)No=100(39.2)Totalresponses=255 (100%)

Yes= 71(70.3%)No=30 (29.7%)Totalresponse =101 (100%)

Yes=60(60%)No=40 (40%)Totalresponse =100 (100%)

Yes=24(44.4%)No=30 (55.6%)Totalresponse =54(100%)

Q3. Haveyouattendedpreviously?

Yes=158(62%)No=97 (38%)Totalresponses =255 (100%)

Yes=64(63.4%)No=37 (36.6%)Totalresponse =101 (100%)

Yes=60(60%)No=40 (40%)Totalresponse =100 (100%)

Yes=34 (63%)No=20 (37%)Totalresponse =54(100%)

Attitudes andPerceptions

Q4. Doyouthinkfestivalis a waytoSupportcommunity

Yes=232(91%)No=3 (1.2%)Totalresponses =235 (92.2%)Refused/unknown= 20(7.8%)Total=255(10

Yes=90(89.1%)No=3 (3%)Totalresponses=93 (92.1%)Refused/unknown = 8(7.9%)Total=101(100

Yes=93(93%)No=0 (0%)Totalresponse =93 (93%)Refused/unknown= 7(7%)Total=100(1

Yes=49(90.7%)No=0 (0%)Totalresponse =49 (90.7%)Refused/unknown=5(9.3%)Total=

I m p a c t s o f t h e O r g a n i s a t i o n C h a l l e n g e s a n dC a p a c i t i e s

O n A t t e n d e e s S a t i s f a c t i o n a t t h eL o c a l

C o m m u n i t yF e s t i v a l s

0%) %) 00%) 54(100%)

Attitudes andPerceptions

Q5. HowusefulareCommunity eventsto meetnewpeople?

Not useful =53 (20.8%)Slightlyuseful=48(18.8%)Useful=55(21.6%)Very useful= 34 (13.3%)Extremelyuseful=43(16.9%)Totalresponse= 233(91.4%)Refused/unknown=22(8.6%)Total=101(100%)