Images of the Modern Girl: From the Flapper to the Joven Moderna (Buenos Aires 1920-1940)

Transcript of Images of the Modern Girl: From the Flapper to the Joven Moderna (Buenos Aires 1920-1940)

1

CECILIA TOSSOUNIAN (Freie Universität Berlin) Images of the Modern Girl: From the Flapper to the Joven Moderna (Buenos Aires, 1920-1940) Abstract:

Scholars have analyzed the emergence of the modern girl figure as a global phenomenon that took

place in many different countries during the first half of the twentieth century. Although she was

undoubtedly a global phenomenon, I am interested on how Argentine contemporaries understood

the modern girl´s modernity. In this particular period and context, ‘Western’ modernity acquired

distinctive contents. The ‘American way of life’, much more than any European lifestyle, became

the symbol of modernity. At the same time, the emergence of the modern girl figure was perceived

as the product of the arrival of US fashions and manners in the country. In order to determine how

the modern girl figure was understood in Argentina, I intend to trace the ways in which the US

embodiment of modernity was appropriated and challenged in the mass media; specifically, I

analyze how the modern girl was dealt with in articles and stories serialized in woman´s magazines

and newspapers that sprang up in Argentina in the 1920s-30s. By means of these multiple

approaches to the modern girl phenomenon, my ultimate purpose is to enhance the understanding

of the relationship between gender, national identity and modernity.

Americanization – modern girl – modernity – national identity - Argentina

In Manuel Gálvez’s short story Una mujer muy moderna (A very modern woman, 1927), the young

protagonist Quica is portrayed as “the perfect embodiment of the modern girl” (la joven moderna).

“She smoked, danced tight with her partner, drank heavily at parties, talked and went out with her

boyfriends, dressed in a provocative way, read indecent books, had radical ideas about morality

[…], rejected religion and was a priestess of the flirt cult.” [1] These attributes are also seen as

what attracted Quica’s husband, a conservative older man, to her. He found the crazy ideas of his

young wife both appealing and controversial. In his view, modern girls like Quica were the product

of a transitional period between old and new morality; he was sure that, with the help of men, over

time modern girls would regain their lost stability. Thus Gálvez implied that modern girls like Quica

would discover their true selves only under the tutelage of a resolute man. And once this shallow

modernity was erased, Quica’s authentic self would be revealed, and she would be transformed

into a respectable housewife. The author’s view of the modern girl is clear: underneath Quica’s

modern manners lay the desire for a ‘traditional’ man and a conservative life style. Gálvez’s story

was one of many cautionary tales with a modern girl as protagonist. Represented as an alluring,

albeit threatening, subject, she appeared in news reports and social commentaries in magazines

2

and newspapers and was the fictional heroine of serialized stories, cheap novels and films. Why

did the modern girl figure so prominently in the mass media during the period under analysis?

What anxieties did she awake? What did she signify in terms of gender and nationalism?

The Modern Girl around the World Research Group has analyzed the emergence of the

modern girl figure as a global phenomenon that took place in many different countries during the

first half of the twentieth century. Referred to as flapper, modern girl, garçonne, moga, neue Frau,

modeng xiaojie and chica moderna in Europe, East Asia, the United States and Latin America, the

modern girl can be typified by her “use of specific commodities”, “explicit eroticism”, provocative

attire, and interest in romantic love. By continually incorporating aesthetic elements from abroad

she created a composite “cosmopolitan look” impossible to reduce to any single national origin.

(The Modern Girl Around the World Research Group “The Modern Girl around the World” 245-46).

While the literature on the modern girl in the United States has linked her emergence to the

rise of a consumer culture, European scholarship has tended to place her within the historical

context of the post-war era. [2] The transnational approach to the modern girl, however, places

greater emphasis on the global aspect of her appearance, suggesting that “modern forms of

femininity emerged through rapidly moving and multi-directional circuits of capital, ideology and

imagery” (The Modern Girl around the World Research Group “The Modern Girl around the World”

248). These latter scholars have termed this process “multidirectional citation”, which they define

as the “mutual, though asymmetrical, influences and circuits of exchange that produce common

figurations and practices in multiple locations.” This perspective questions narratives based on the

diffusion of ideas from the West to the rest (The Modern Girl around the World Research Group

“The Modern Girl as Heuristic Device” 4,7).

Although the modern girl figure was undoubtedly a global phenomenon, I am interested on

how Argentine contemporaries understood the modern girl’s modernity. In this sense, as in other

parts of the colonial and postcolonial world, she was perceieved as a foreign-inspired figure, which

came basically from the US. [3] Research from a postcolonial perspective has focused on the

complex relations between modernity and colonialism on the one hand, and the emergence of a

modern nation on the other. The hypothesis is that in postcolonial contexts women played a key

role as signifiers of both tradition and modernity. According to Mrinalini Sinha, “women […] have

had to carry the more complex burden of representing the colonized nation’s ‘betweenness’ with

respect to precolonial traditions and ‘Western’ modernity”. Accordingly, “this flexibility in the

metaphorical role of women for the gendering of tradition and modernity” has reflected “the

complex ways in which the problem of tradition and modernity is recast in the context of […] anti-

colonial nationalism” (Sinha 254). [4] Indeed, the problems raised by certain postcolonial scholars,

3

especially the conflictive relation between the celebration of a precolonial past—possibly connoting

backwardness—and the imitation of metropolitan cultures—which may deprive subjects of a

‘genuine’ identity— are useful for thinking about nationalism, the construction of national identities,

and their relation with the emergence of modern gender figures in interwar Argentina.

As in other colonial and postcolonial contexts, in general, womanhood in Argentina and,

specifically, the modern girl figure were in the forefront of the debate on how to reconcile the

desirable aspects of ‘Western’ modernity with the need to address national differences. [5] In this

particular period and context in Argentina, ‘Western’ modernity acquired distinctive contents. The

‘American way of life’, much more than any European lifestyle, became the symbol of modernity.

At the same time, the emergence of the modern girl figure was perceived as the product of the

arrival of US fashions and manners in the country. ‘Americanization’ has recently received a great

deal of attention in Latin American historiography. Researchers have focused on the often

ambivalent perceptions elicited by the US in different Latin American nations. This encounter is

viewed more as a transnational interaction among reciprocally transforming domestic and foreign

elements than as a dichotomy between center and periphery conceptualized in terms of

“domination and resistance, exploiters and victims” (Gilbert 4).

In this paper I am concerned with how different social actors, basically male intellectuals

and journalists during the interwar era, interpreted the modern girl phenomenon, as well as how

they confronted the diverse changes associated with this figure. In order to determine how the

modern girl figure was understood in Argentina, I intend to trace the ways in which the US

embodiment of modernity was appropriated and challenged in the mass media; specifically, I

analyze how the modern girl was dealt with in articles and stories serialized in woman’s magazines

and newspapers that sprang up in Argentina in the 1920s-30s. In the first section, I examine the

Buenos Aires of the 1920s-30s, detailing the ways in which the ‘North American way of life’

reached the city. I then study how Argentine journalists and writers cast a selective gaze on North

American women, creatively appropriating and interpreting images of US women that addressed

specific national concerns. And finally, I reconstruct how the modern girl was perceived in

Argentina, taking into account the particular values incorporated domestically. By means of these

multiple approaches to the modern girl phenomenon, my ultimate purpose is to enhance the

understanding of the relationship between gender, national identity and modernity.

A Modern Metropolis: Buenos Aires encounters the ‘American way of life’

4

Historians have described interwar society in Buenos Aires as socially fluid. Class, ethnic and

gender identities underwent a process of profound change in the early decades of the twentieth

century. In turn-of-the-century Argentina, the strengthening of the country’s position in the world

market as grain and meat exporter, combined with the influx of foreign capital and immigrants into

the country, led to widespread economic prosperity. This process produced an important

reconfiguration of Argentine society. According to historians, between the end of World War I and

the beginning of World War II, Buenos Aires experienced a series of material, social and cultural

changes that made it the symbol of this prosperity: it was the busiest commercial port in Argentina,

as well as the main port of entry for European immigrants, and the city where most internal

immigrants chose to live. [6] It became one the largest cities in Latin America during this period; its

opulent city center, studded with impressive banks, fashionable stores, cafés, restaurants,

cabarets, department stores, cinemas and ballrooms, reflected this newfound economic well being.

Eloquent in this regard is the fact that, in allusion to its elegance and glamour, consumerism, and

ties to international capitalism, Buenos Aires was called the “Paris of South America.” [7]

Argentines, especially residents of Buenos Aires known as Porteños, experienced an

explosion of mass culture and consumption. New images showing the latest foreign customs and

commodities began circulating, and a transnational discourse on modernity was evident in

magazines, newspapers, advertisements and motion pictures. As the source of many of these

images, the United States became the ‘symbol of modernity’ for consumers of these commodities.

A publishing boom marked the 1920s. Literacy rates comparable to those in western

Europe greatly expanded the market for popular literature. [8] Newspapers, magazines and books

at accessible prices proliferated. [9] Magazine covers, illustrations and advertisements of the

period showed beautiful women dressed in the latest styles, while the yellow press and cheap

novels offered up detailed accounts of the scandalous private lives of internationally renowned film

stars and wealthy people. In addition to reading a wide range of newspapers and magazines, for

the first time the general public had access to the latest international best-sellers in paperback, as

well as to affordable editions of the classics and pseudo-scientific writings on sexology (Romero

62-3; Sarlo El Imperio 25). Women’s magazine articles, sexology books and specialized journals

turned moral and sexual issues into public topics of conversation characterized by a marked

eroticism. Mariano Plotkin has pointed out that subjects such as relations between the sexes and

sexuality in general drew attention and were discussed more openly than ever before in the mass

media. According to Plotkin, “a new discourse on sexuality, that detached the erotic dimension

from the realm of reproduction and marriage, emerged gradually since the 1920s” (Plotkin 609-10).

5

While the editorial boom was characteristic of the 1920s, the arrival of films from abroad

revolutionized the following decade. By the late 1920s, the cinema had consolidated its popularity,

with Argentina becoming the second largest client for US films. In 1929, 30 million people visited

one of the 972 cinemas in the country, of which 152 were in the city of Buenos Aires (Rocchi

“Inventando la soberanía” 311; Karush 299). European and, to a greater degree, US films offered

these audiences images of and narratives about foreign lifestyles not previously available on a

mass scale. Indeed, Ana López has argued that early cinema became a means for expressing the

contradictions of modernity. While audiences could admire the modernized foreign “other” (modern

cities, customs, fashions and consumer products), this problematized the meaning of locality and

self, producing “a need to assert the self—as modern, but also, and more lastingly, as different;

ultimately as a national subject” (153, 162).

The ‘American way of life’ not only affected mass culture, but also brought about changes

in existing patterns of consumption. US involvement in the Argentine economy drastically altered

the industrial sector. On the one hand, US companies invested in the petroleum industry and

exported cars and agricultural and textile machinery, making Argentina the sixth largest market for

US exports in the late 1920s. And on the other, US machine, metallurgic, electronic,

pharmaceutical and toiletry companies established subsidiaries in Argentina. [10]

The emergence of a domestic industrial sector went hand in hand with the birth of a

consumer society. According to Fernando Rocchi, the middle classes emulated the upper in

fashion and taste, thus blurring class distinctions. In addition, the eight-hour workday law passed in

1929, the subsequent 1932 law installing the English Saturday, and a relative increase in workers’

wages granted some leisure time to people from the working class, whose patterns of consumption

and leisure activities simulated those of the middle classes. Mass consumption generated a sense

of the “democratization” of society: the availability of inexpensive domestic versions of clothing and

other imported products traditionally consumed by the elite gave the impression that everyone

consumed the same things and dressed in similar ways. (Rocchi “Consumir es un placer” 546-47,

Rocchi “La Americanización del Consumo”). Concomitantly, in the early twentieth century the

growth of department stores revolutionized the production and commercialization of consumer

goods. Two of the most important, Gath and Chaves (1910) and Harrods (1913)—targeting the

middle and upper classes respectively—built large, multi-storied stores. (Rocchi “El péndulo de la

riqueza” 44). The products displayed and marketing strategies deployed in these flamboyant

department stores created the sense that, in general, modern consumption patterns came from

abroad, at least for the upper classes that could afford the imported products in question.

6

The spread of the consumer society in Argentina produced a revolution in advertising.

Products were generally manufactured by US-based multinational corporations and advertised by

US ad agencies like J. Walter Thompson (JWT), based in New York with offices around the world.

As Victoria de Grazia has shown, following an agreement with General Motors in 1927, JWT set up

shop in countries where the latter had a plant. In 1929 JWT arrived in Buenos Aires. As new

offices opened, the advertising agency “sought to obtain the local accounts for the other major

brands the company promoted back home” (237).

In the search for new markets to conquer, JWT surveyed consumers in order to ascertain

Argentine preferences and taste. Excluding poor immigrants and “dark-skinned inhabitants from

the provinces” who didn’t qualify as “potential consumers”, the surveys focused on the middle and

high income groups residing in Buenos Aires and several prosperous provinces. As Ricardo

Salvatore has pointed out, the agency discovered that “products of personal hygiene and care,

such as toothpaste, facial cream and powder”, among others, were in high demand in Buenos

Aires, especially among the brand-conscious middle and upper classes. They also discovered that,

in the area of consumer goods, there was a “rapid adoption by urban and middling Argentines of

the consumer pattern associated with American-style high modernity.” The conclusion reached by

JWT was that “in their imitative behavior and quest for prestige goods, ‘Argentine consumers’ were

not different from American consumers” (216, 223-4).

Clearly, this period was characterized by an increase in the global circulation of images,

commodities and capital. Concomitantly, different types of cultural nationalism that viewed this

interdependence with concern emerged. While Porteños seemed fascinated with US fashions and

manners, there was also anxiety regarding the changes the city was experiencing. Cultural

nationalists first and foremost, but also writers and journalists viewed the modernized city as

chaotic and unstable, their assessment usually assuming the form of a nostalgic discourse (Sarlo

Una modernidad 26-33). As Carlos Altamirano has put it, during this period there was a sense that

Argentina was undergoing a “moral crisis”. One of the causes could be found in the materialistic

spirit corrupting old Argentine roots that was embodied in the cosmopolitan city of Buenos Aires

(Altamirano 201-09). According to this diagnosis, excessive cosmopolitanism was diluting the

authentic culture and traditions of the country that had come under threat from foreign influences.

There was a nostalgic cast to the discourse expressing the ideas of the cultural nationalists:

progress was seen as irremediably destroying the past (Delaney 625-6). In this context, “moral

regeneration and the restoration of the national spirit appeared as two sides of the same

movement” (Altamirano 207). As in other Latin American countries, nationalism began to focus on

cultural authenticity as a way of creating ‘unique’ national identities. Expressed in different ways,

this ‘uniqueness’ could embrace praise for indigenous or mestizo cultures, together with the

7

rediscovery of the Hispanic legacy. All in all, the debate about Argentina’s national identity

increasingly targeted US cultural penetration as one of the causes of the Argentine moral crisis.

Gender issues and images and, specifically, the modern girl figure appeared at the heart of this

debate.

The Modern Girl: Views on the North American Flapper

US women appeared with increasing frequency in the mass media of the period. Fascinating yet

intimidating, they were portrayed in different ways as modern girls or flappers, the term commonly

used to identify them. In the pages of the most prominent newspapers and magazines Argentines

were confronted with several versions of this figure.

Since the early 1920s, and especially during the 1930s, media photos of internationally

famous actresses and other performers—especially those from Hollywood—and beauty queens

became the prime means for spreading the figure of the modern girl and her fashions. A case in

point are the social commentaries about, interviews with, and biographies of famous performers

such as Josephine Baker and silent film stars like Clara Bow and Pola Negri that were published in

magazines and newspapers of the period. [11] All magazines and many newspapers available at

the time had a special section dedicated to famous international actresses that included photos

and information about them. Extremely interested in developments in the cinema, in 1919 the

newspaper Crítica began printing a section titled “El cine, sus obras y sus héroes” (Cinema, its

works and heroes), containing photos and information about Hollywood actresses. The so-called

sweet young girls in American films—Mary Pickford and Lillian and Dorothy Gish—merited

frequent articles in this newspaper. Mary Pickford and Dorothy Dalton won one of Critica’s annual

contests for determining the most popular foreign actresses. [12] Magazines also published

photos of beauty queens, especially those from the US, which reinforced the image of the modern

girl as fashionable aesthetic. [13]

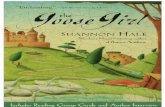

In this type of portrait, the beautiful, erotic body and pretty face of modern girls from the US

were presented as examples of what was trendy. In September 1927 Caras y Caretas published

an article about both actresses and beauty queens under the title “Las mujeres modernas”. The

article was illustrated with four photos of US women. According to the captions, two were

actresses and two, participants in a regional beauty contest. In addition to their names, the

captions expressed admiration for the women’s beauty. The four were pictured making gestures in

tune with their erotic or exotic clothing. As indicated by the title of the article, being modern meant

8

acquiring a special type of image: short hair, heavy makeup, fancy or sexy clothes, and a slender

body. It also meant being beautiful and provocative. [14]

“Las Mujeres Modernas.” Caras y Caretas September 1927.

This was how the modern girl was positively represented. In 1922 the newspaper Crítica

published a photo of a group of actresses in bathing suits posing for the camera in downtown New

York City under the title “El grupo de mujeres más frescas del mundo” (The world’s coolest

women). The caption explained that the women, who had posed in bathing suits in order to win a

bet, were arrested shortly after the photo was taken. Crítica presented the story as an amusing

anecdote, inviting readers to enjoy the image while stating: “Here you have them, reader. Look at

them […] and you will see how you can forget all the unpleasant things of this wretched life!” [15]

Crítica also published photos of ordinary young, beautiful US women, such as one who, after being

arrested for hitting a streetlamp with her car, took off her coat to reveal a bathing suit underneath.

In the photo she had the perfect modern girl look: cloche hat, short hair and the right makeup. She

also had a kind of naughty look or impudent gaze, as if she was making fun of the reader. [16]

Images of the modern girl in the 1920s also circulated in advertisements. Fernando Rocchi

has argued that, because consumption was perceived as a female practice, advertisements

targeted women not only as consumers, but also as objects of ad contents. Advertising relied on

the figure of the modern girl to appeal to consumers by showing images of fashionable women

driving cars and smoking cigarettes. (Rocchi “Inventando la Soberanía del Consumidor” 313,

9

Rocchi, “La Americanización del Consumo” 181-2). Ads for cosmetics and toiletry products, in

which the modern girl appeared massively, often encouraged consumers to cleanse and beautify

their skin and modify facial features or hair color. These ads often used the image of the same

modern girl to advertise its product all over the world, as in the case of a Pepsodent ad that used

an elegant drawing of the modern girl figure to sell toothpaste. [17] Moreover, the ads proclaimed

the same thing around the world: Pepsodent removed the “dingy film” from teeth. Readers were

encouraged to send in a clip-out coupon provided in the ad for a free sample. The Modern Girl

Research Group has suggested that these Pepsodent ads “exhibit an aesthetic that evokes

“Americanness”: an open easy smile, big white teeth, and body language that is noticeably […]

sensual, relaxed, at leisure” (The Modern Girl around the World Research Group, “The Modern Girl

around the World” 254). By the 1930s, in accordance with the allure of ‘authenticity’, photos

commonly showing film stars often replaced drawings in advertisements. Several ads produced by

JWT depicted Hollywood actresses such as Sylvia Sidney, Claudette Colbert, and the Mexican star

Lupe Vélez to sell Lux soap. [18]

Actresses and beauty queens were the most popular figures in magazines, newspapers

and advertisements, and photos or drawings of their bodies proliferated on their pages. What

dominated in all cases was their physical appearance. When their bodies were exposed in public

to the gaze of the Argentine reader, the motive was their beauty and eroticism, which transmitted

at the same time a sense of modernity. Images of the beautiful, provocative bodies of movie stars

and beauty queens were unproblematic as long as they were presented as alien to Argentine

audiences. Their foreignness, remarked upon in photo captions and commentaries, reassured the

audience that this was happening somewhere else, giving the readership the opportunity of

enjoying this type of ‘exotic’ image with voyeuristic pleasure. [19]

While this kind of image of how a modern girl should look continued to appear in the mass

media of the period, articles in the same magazines and newspapers portrayed US manners,

specifically the relation between the sexes and US women, in a less positive way. Interestingly

enough, a great many articles criticized the ‘American way of life’ by means of an analysis of

gender relationships in which the customs of US women were always the center of debate. The

magazine El Hogar, among others, published several articles depicting US habits in its section “La

vida en Norteamérica” (Life in North America). In 1937 the magazine published an article titled “El

noviazgo es en Estados Unidos una amistad excenta de romanticismo” (Going together in the US

is friendship without romanticism), in which the author compared US couples with Argentine ones,

arguing that North American women had more freedom than Argentine women and usually stayed

out until late at night with their boyfriends, hanging around, drinking and smoking. Couples were

portrayed as having a relationship closer to friendship than romance, which could easily end in

10

divorce because of the lack of true love. Conversely, Argentine couples, who understood what real

love and romanticism meant, were more committed to each other and had longer engagements

before getting married, which resulted in more satisfactory marriages because they knew each

other better and took the bond of matrimony more seriously. In this sense, Argentine women, who

tended to be chaste, usually spent only a few hours a day with their boyfriends and did not let

themselves be kissed in public. [20]

It comes as no surprise that the next article in this section was dedicated to the behavior of

married women in the US. On this occasion the author portrayed US woman as dangerous

competitors of men because they chose to work instead of staying home. By abandoning the

‘natural’ place for a woman to be, US women jeopardized the entire social structure. They refused

to have children because they privileged working in an office and then going out for a drink with

colleagues just like their husbands. This situation created resentfulness in men, who did not know

how to react to these altered gender relationships. Of course, as the author stated, North

Americans did not realize that these changes would have devastating consequences for their

country, as this new fashion signified the crumbling of the North American family. By contrast,

Argentines were far removed from such a catastrophic future because Argentine women still

stayed home, keeping house for their husbands and raising the children. [21]

In another article from 1934, this time in the magazine Mundo Argentino, the journalist

portrayed the behavior of US women as the cause of the country’s high divorce rate. Once again

marriage occupied center stage. North American marriages lacked true commitment; they were

only a hobby or a game dictated by the whims of US women embodied in the figure of the

“flapper”, a “being without any sense of morality” who just wanted money or fame. Therefore, when

a female “yanqui” got married, she was to blame for the marriage’s tragic end. “North American

civilization is developing under this dangerous sign of femininity.” Because love was a serious

matter in Argentina, marriage was conceived as a lifelong bond. Furthermore, Argentine woman

were very different from North American ones and, even more importantly, they did not want to be

like their “yanqui” counterparts. Love and marriage were the supreme ideal of happiness for

Argentine women. [22]

It would seem that the declared aim of these articles was to criticize US manners in order to

extoll the virtues of the Argentine way of life. Safe from the dangerous fashions imported from the

US, Argentine women were portrayed as the opposite of their North American sisters. It is

interesting to compare these statements with how a US journalist perceived gender relationships in

Argentina. In a series of articles published in the magazine El Hogar, the North American journalist

Lilia Davis, utilizing data compiled by someone else, recounted how Argentine women were both

11

fond of the institution of marriage and also of “Americanizing” themselves. After investigating

Argentine customs, she wrote that, while showing off their independence by going to dance halls,

drinking, smoking and riding around in cars, as soon as a potential husband showed up, Argentine

women took off this modern “costume” in order to get married. [23] In another article analyzing the

institution of marriage in Argentina, she stated that, in contrast with her North American sister, an

Argentine woman enjoyed little freedom. While husbands went nightly to clubs, female Argentines

stayed home. The author concluded that it was their own fault: they had not “evolved” like US

women and, consequently, their marriages lacked the companionship element. Credulous and

docile, Argentine women remained stuck at home. [24]

Naturally enough, a reply appeared in the next issue of the magazine where one of many

angry letters from male readers was published. In it the writer argued that “we have civilized

ourselves, Miss Davis,” implying that Argentine women did have their independence. The fact that

they preferred to go out with girlfriends and not their husbands made precisely this point. He added

that there were no “flappers” to go dancing with in Argentina because there were no nightclubs like

those in the US to go to. The writer of the letter was eager to note that, although evolved,

Argentine women remained proud of being housewives and mothers, just as Argentine husbands

were proud of being the breadwinner. The concept of “Home Sweet Home” was experienced in

very few countries; Argentine was obviously one of them, and the US most certainly was not. While

the reader appeared angry, mostly because he did not like how Argentine men were described,

everybody, including the US journalist herself, seemed to concur that Argentine women’s behavior

was very different from that of their US counterparts. [25]

While certain authors portrayed US women, especially those in the guise of the flapper, as

having loose morals when compared to Argentine women, others stressed their alleged

masculinity. In 1930 the well-known writer Horacio Quiroga published an article titled “Las

Amazonas” (The Amazons) in the magazine El Hogar. In it he described the US-inspired “flapper”

as a female conqueror seeking to usurp men’s spaces and losing her femininity in the bargain. He

argued that women in the US were fond of practicing masculine sports and driving a car, while

men, in turn, were becoming feminized. He exemplified this transformation by analyzing two

advertisements: in the first, a woman embodying values like brave was shown standing beside a

car; in the second, a man smelling perfume visually represents the “delights of toiletries”. For

Quiroga these images indicated the “subversion of sexual roles” in violation of the rules of nature.

Moreover, in his view, by allowing women to become masculinized, men were emasculating

themselves. He went on to say that “there are some people in the United States who have

observed a decrease in feelings of love in the flapper. […] We just have to wait, watching

pensively, for the punishment that the immutable species has in reserve for these virgins with

12

truncated bosoms.” [26] The flapper was portrayed not only as a freak of nature, but also as a

threatening subject who placed in danger the natural equilibrium of US society.

An article published in 1927 in Caras y Caretas reinforced this image of masculinized

women in the US. In “¿Hacia la supresión de los encantos femeninos?” (Toward the suppression

of feminine charms?) a series of photos appeared in answer to this question. Four ‘masculine’

women dressed in men’s suits were pictured in the first row. The caption stated that the above

figures favored the disappearance of femininity in the US. The second row of photos showed only

female legs. The caption reproved modern dress for exposing women’s legs, arguing that,

although a symbol of femininity, en masse the legs represented an exaggeration. Hence, the

purpose of the article was to show opposing versions of the modern female figure, both worthy of

reproof for tending to suppress female charms. On the one hand were images of overly-

masculinized US female figures, and on the other, examples of exaggerated femininity. [27]

Indeed, the figure of the flapper or modern girl figured prominently in how the ‘American

way of life’ was conceived in Argentina. Up to this point the Argentine representation of the flapper

has been analyzed either as a beautiful, erotic and modern image provoking curiosity and

voyeuristic desire or as a morally threatening masculine subject potentially unleashing vast social

problems in the US. In both cases, however, the figure, originating in a faraway country, was

portrayed as alien to Argentine culture. For the journalists and writers cited above, modernity was

embodied in these bold women who, most significantly, resided abroad. Often English terms such

as flapper were employed when referring to the modern girl. Moreover, the real Argentine woman

was the veritable antithesis of this modern foreign figure. But what happens when the supposedly

distant, and therefore unproblematic, danger is discovered within Argentina itself?

La Joven Moderna: the Argentine Embodiment of the Modern Girl

While some writers and journalists viewed the United States with mixed feelings of curiosity and

concern, others pointed out that North American fashions had already made their presence felt

within the country, provoking changes in the behavior of Argentine women. This prompted a

special effort to explore the nature of the modern girl’s behavior. [28] There was a basic

consensus that the Porteño modern girl’s manners were a copy of foreign female attitudes,

especially those imported from the US. However, different interpretations were given to this fact.

In a series of articles published in 1918 in El Hogar, under the title “De la vida nacional”

(About national life), Luis María Jordán analyzed national traditions and customs. In the first article

13

he refused to accept the picture of Argentina as a country that could only imitate imported styles

and practices, making it a “morally and mentally inferior ethnic community”. In his view, Argentina

was capable of incorporating the values of “modern civilization” without losing its identity. The

author was certain that the country was going through a transitional period and that soon a group

of intellectuals would emerge to synthesize “the aspirations of the race”, while creating a cohesive

national identity. [29] In subsequent articles, Luis María Jordán analyzed different manifestations of

this hypothesis. In “El espíritu femenino” (The feminine spirit), he stated that Argentine women,

especially formerly modest ones with upper class “creole lineage”, had decided to copy Parisian

fashions and be guided by a sense of moral freedom originating in the US in order to distinguish

themselves from middle class women. According to the author, they “became frivolous and lost […]

a lot of their colonial creole modesty”, feeling “a little overwhelmed by the excess of freedom,

surprised by a too rapid liberation”. Nonetheless, he was convinced that this situation was

temporary and that “our youth, faithful to the virtues of our native race, will listen to and never

forget the austere clamor of lineage.” [30]

He was not the only one to portray the Porteño modern girl as phony. In another article

titled “Velocidad y Modernismo” (Speed and modernism), published in 1933, a journalist analyzed

the peculiar characteristics of the Argentine version of the modern girl. He saw modern women as

varying from country to country because “the concept of modern” had to be adapted to each

woman’s prior personality and the peculiar traits of each locality as well. In the case of Buenos

Aires, the essential characteristic of the modern young woman was her lack of creativity. Where

the modern Parisian woman invented, her Porteño counterpart copied and standardized. Indeed,

she refrained from inventing anything new and original for fear of making a fool of herself. Thus

“the female Porteño way of being modern […] has been achieved by a smart assimilation of the

examples available for emulation”. [31]

A similar but more critical and pessimistic point of view was expressed by Ezequiel

Martínez Estrada. In his essay Radiografía de la Pampa (X-Ray of the Pampa), written in 1933, he

gave an interesting interpretation of the modern girl phenomenon. Martínez Estrada described the

Porteño modern girl as an artificial type who copied foreign fashions. Like other features of modern

Argentine life such as city structure or culture, she was characterized by a desire to imitate Europe

or the US. Despite its many manifestations, the attempt was a vicious circle doomed to failure

because of the impossibility of changing the essential nature of Argentina and Argentines. (Sarlo

Una modernidad 221-8).

Using the flapper or garçonne figure interchangeably to refer to the modern female Porteño,

Martínez ridiculed her for not being radical enough. In the author’s view, the Porteño modern girl

14

was simply a fake copy of the original. Unlike her French or North American sisters, she believed

that a change in morals was only a question of fashion, thus failing to follow through on the moral

implications of being modern. Underneath her short hair, loose morals, and customs like smoking,

the author argued, a traditional conception of womanhood was to be found. In his words,

our garçonne is a virtuous young woman who guards her virginity with heroic fortitude. She is still old-fashioned yet already modern; she wears the latest fashions over her Castilian sense of honor. […] But where the liberal woman, whose attitudes and temptations she has copied, gives in, greets and goes off with her lover, she resists and saves her honor […] She disguises herself as what she is not, as what she wouldn’t like to be. [32]

For some Argentine intellectuals and writers, the joven moderna was a fake copy of an

imported original model. They emphasized the imitative behavior of the modern girl as one of her

primary characteristics, depicting her as not having a personality of her own. Underneath this

superficial modernity, some features of the traditional female survived, which the authors claimed

as the true nature of Argentine femininity.

Other writers, however, treated the joven moderna with much greater concern, describing

how foreign fashions had already perverted this ideal type of Argentine femininity. In a series of

articles titled “Los peligros del modernismo”, and published in the magazine Para Tí in 1935,

Graciela Madero argued that “modernism”, a new fashion imported, along with literature and films,

from the US had the worst consequences for women because they were the first to adopt these

novelties. [33]

Perhaps the most comprehensive reconstruction of the Porteño modern girl was the

satirical moral tale titled “La Beba: Historia de una vida inútil” (Beba: The Story of a futile life),

serialized in Caras y Caretas between June 1927 and March 1928. [34] Signed with the

pseudonym of Roxana and published weekly, the story described the life of Beba, a seventeen-

year-old upper class modern girl. In the first episode of the story, Beba was presented as frivolous,

fanciful and conceited, the symbol of an entire generation of young Porteño women, and also men,

who enjoyed a “frenetic”, “agitated”, modern way of life “without caring about its consequences”.

[35]

Beba was pictured as thin and lithe, wearing abundant makeup and short skirts, and having

bobbed hair. Her foil was her sister Martha, described as intelligent, quiet, somewhat old-

fashioned, and always worrying about Beba’s improper, impulsive behavior. As the author noted,

the sisters belonged to two very different generations. While Martha was reflexive and calm, Beba

was flighty and frivolous, someone who “embodies all the manifestations of modern lightness”.

They represented the “past and the present” of Argentine society. [36]

15

In the following 35 episodes, Beba was shown in different scenarios carrying out diverse

activities. She went to theatres and the cinema, cafés and dance halls. She assiduously did the

Charleston and danced the tango. She also smoked, drank, sang tangos, drove her own car, and

dressed up as a theatre actress for Carnival. Indeed, perpetual motion appeared to be her defining

characteristic. In every chapter Beba went to a different place to do something different.

Beba is first portrayed as almost ‘innocent’, someone who wants to experience life and

comes progressively in contact with the customs of the modern city that ‘corrupt’ her spirit. Right

from the beginning, the author leads the reader to understand that challenges to morality originate

outside traditional Argentine values in the form of a materialistic lifestyle imported from the US.

Various examples of this ‘contamination’ process are offered.

On the one hand, Beba is determined to see an allegedly “immoral” Hollywood film that

provokes licentious desires in her. With the complicity of her parents and the opposition of her

sister Martha, who did not want to see a movie she considered indecent, Beba goes with her

brother and a friend. At some point in the film, she is seen struggling against desires inspired by

the film; she succumbs to them in the end as her friend lays a complicit hand over her’s. [37] And

on the other hand, the aspiration of Porteño modern girls like Beba to trendiness induces them to

adopt US and Argentine actresses’ fashions and customs—miniscule bathing suits and low-cut

dresses, dancing the Charleston and the tango—that make them look cheap like the lower class

actresses and singers with dubious morals who populate Porteño cabarets (known as bataclanas).

[38] Beba’s interest in the “morbid” contents of foreign novels by “modern writers” shrivels her

innocent soul. [39] And finally, the fact that Beba likes modern dances such as the Charleston or

the tango requiring body contact and intimate postures is considered scandalous because of the

sexual connotations. [40] These influences serve to pervert an old type of ‘native’ morality

embodied in Martha and depicted nostalgically. By satirizing Beba and elevating Martha, the

author was denouncing the penetration of foreign values and practices.

From the above, one would conclude that being modern clearly signified embracing

wholeheartedly US manners and fashions. However, there were equally clear references to certain

national popular traditions like the tango and the plebian way of dressing and customs of actresses

that Beba also adopted. In this sense it can be said that, while assuming the form of a typical

flapper, she did not merely copy her North American sister. With the inclusion of certain national

popular traits, Beba is also portrayed as ‘authentically’ Argentine from the city of Buenos Aires.

Consequently, the contamination of upper class modern girls came not only from US culture, but

also from the Argentine national popular cultural tradition. These two cultural currents were

16

presented as alien in a dual senses: they lay outside the traditions of the nation and of its upper

classes.

From one standpoint, Beba liked modern dances such as “the Charleston, shimmy and

black-bottom” that had been imported from the US and, even worse, were “exotic”, “savage”,

“uncivilized” and “inspired by the dances of African black people”. The only people who dared

dance them were blacks, cabaret dancers and habitués of popular dance dives in New York City.

[41] The author argued that ‘modern/African’ dances were copied by Hollywood film stars and then

adopted by modern Argentine girls in order to be viewed as different and modern because they

enjoyed these “savage”, exotic dances.

From another standpoint, Beba was fond of the tango. In this story the tango retained its

popular connotations, and dancing it implied downward mobility on the social scale. In addition,

modern girls like Beba not only danced the tango; they sang it as well. The lyrics, based on a

popular jargon called lunfardo, were characterized by graphic, oblique sexual references. [42] The

author considered it indecent for upper class girls to employ this popular argot. [43] Indeed, the

protagonist of the story was presented as embracing the tango and lunfardo slang in order to

differentiate herself from her parents and sister and assume the role of an “ultra-chic” rebellious

modern girl. An interesting aspect of this situation is that, in a sort of mirror gaze game, modern

young women in Europe and the US often danced the tango and dressed tango style in order to

appear different, exotic and modern themselves. And furthermore, this dance was often criticized

for being “lascivious and decadent” and for “encouraging encounters between young ladies and

men who might be of American and South American Negroid origin.” [44]

Beba was also described as incapable of emotional commitment. She had several

“modern” boyfriends who endorsed the same values as she did. They flirted with her but, just like

Beba, did not want to commit to a serious relationship. [45] In terms of morality, the contrast with

Martha became apparent. In one chapter Beba exclaims: “Why should we have to praise old-

fashioned customs? When a man wanted to court a woman, didn’t he kiss her hand? Nowadays he

also kisses her, but now he has the right to choose the place!” [46] In her desire for sentimental

romantic love Martha, on the contrary, embodied the old morals. “Martha, fond of yesteryear

strictness [...] cries because of the advance of a liberalism and materialism that destroys

everything. The sentimentalism and romantic ideals she had dreamed of for so long, are gone

[…]!” [47] In the last chapter the reader gets a glimpse of Beba who, although married, will in the

future simply revert to the habits of her single life. In fact, in the last chapter, Beba ends up

marrying an older man whom she hardly knows and with whom she is not in love. The advantage,

according to the author, is that as a married woman, she will have more freedom, which with time

17

will lead to the “crumbling of her future home”, a dismal forecast of the consequences in store for

national life. [48]

For the above authors, the joven moderna was already an Argentine reality. Viewing her as

a fake copy of the original version located abroad, particularly in the US, certain authors did not

take the joven moderna very seriously; in sharp contrast, for other commentators US fashions and

manners had already perverted Porteño youth, primarily young women, a fact that had the

potential to undermine the future of the nation.

Final remarks

In the early decades of the twentieth century, Argentines were very attuned to the behavior of

North American women. Writers, journalists and intellectuals meticulously described the social

context of the United States, particularly through analyzing the manners of its women, highlighting

those aspects of their behavior most clearly differentiated from Argentine gender patterns. The

exoticism, freedom and boldness of women from the US were the aspects most often emphasized,

together with their materialism, lack of morality and masculine manners. While these differences

from the traditional version of Argentine femininity were stressed by some in order to reassure

Argentine audiences that these changes were occurring abroad, other assessments concluded

that these new fashions and manners had already ‘corrupted’ Argentine women. The existence of

an Argentine version of the flapper was one outcome of the dissemination of U.S. commodity

culture in Argentina, resulting in the joven moderna being perceived as a threat to both gender and

national identity.

What was in question in these assessments was how Argentina could become modern. By

signaling the negative aspects of modernity embodied in the modern girl figure—whether flapper or

joven moderna—, these journalists, writers and intellectuals were attempting to define an identity

for the nation and for its women. The aim of this creative appropriating and translating of US

gender images was to build their own version of a modern Argentina, one that could be cleansed

of their northern neighbor’s excesses.

The modern girl was a worldwide phenomenon, and, as scholars have affirmed, her

globalism makes it necessary to decentralize the idea of ‘Western’ modernity. Nevertheless, if we

focus on how contemporary social actors understood modernity, it becomes clear that in Argentina

they identified it with the ‘American way of life’. They appropriated and utilized certain images of

US women in order to advance their own agendas; conversely, they also viewed these imported

18

fashions and practices as imposed from abroad and consequently the vanguard of a foreign-

inspired, invasive process that threatened to destroy Argentina’s unique authentic character.

Contemporaries not only associated modernity with femininity, conceiving the US flapper as a

threatening figure; they also linked both concepts to nationalistic ideas, making her Argentine sister

the embodiment of an antinationalist subjectivity.

19

Endnotes [1] Gálvez, Manuel. “Una mujer muy moderna.” Una Mujer muy moderna. Buenos Aires: Tor, 1951 (1927). 5-51, 7. [2] For Europe, see, among others, Roberts, Mary Louise. Civilization without Sexes: Reconstructing Gender in Postwar France, 1917-1927. Chicago and London: Chicago University Press, 1994; Von Ankum, Katharina ed. Women in the Metropolis: Gender and Modernity in Weimar Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997. For the US see, among others, Kitch, Carolyn. The Girl on the Magazine Cover: The Origins of Visual Stereotypes in American Mass Media. Chapel Hill, NC: University of Chapel Hill Press, 2001; Peiss, Kathy. Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986; Latham, Angela. Posing a Threat: Flappers, Chorus Girls, and Other Brazen Performers of the American 1920s. Hanover: University Press of New England, 2000. For Latin America, see Hershfield, Joanne. Imagining la Chica Moderna: Women, Nation, and Visual Culture in Mexico, 1917-1936. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2008. [3] See individual chapters of the Modern Girld Around the World Research Group. The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity and Globalization. Weinbaum, Alys Eve, Lynn Thomas, Priti Ramamurthy, Uta Poiger, Madeleine Yue Dong, and Tani Barlow eds. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2008. [4] See also, among others, Chatterjee, Partha. The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993, 116-57; Kandiyoti, Deniz. “Identity and its Discontents: Women and the Nation.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 20.3 (1991): 429-43. There is an uneasy relationship between Latin American scholarship and postcolonial studies, which arises, on the one hand, from the cautiousness of Latin American scholars towards the concept of postcolonialism, on the basis that it contains a universalizing impulse, in particular through “the west and the rest” dichotomy. On the other hand, there is a suspicion about how the postcolonial paradigm could fit into the Latin American case in historical terms, derived from the fact that in the Latin American case postcolonialism as a historical condition preceded postcolonialism as a theoretical perspective by nearly two centuries, thus complicating the adoption of postcolonial theory for the Latin American case. [5] My research is framed by Frederick Cooper’s proposal to think about modernity as a representation, “as the end point of a certain narrative of progress, which creates its own starting point [tradition] as it defines itself by its end point”. Cooper, Frederick. Colonialism in Question: Theory, Knowledge, History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005, 126. [6] In 1880 Buenos Aires had 286,000 inhabitants; in 1895, 649,000, and by 1930, 2,254,000. Romero, José Luis. “La ciudad Burguesa.” Buenos Aires: Historia de Cuatro Siglos. Romero, José Luis and Luis Alberto Romero eds. Buenos Aires: Abril, 1983, 9-17, 9. [7] Between 1880 and 1916 the population tripled, largely due to the influx of immigrants, and the economy grew by a factor of nine, resulting from a G.D.P that increased at an average annual rate of 6%, together with a per capita product growing at an average annual rate of 3%. After the World War I, economic growth continued at the same rate. Rocchi, Fernando. “El péndulo de la riqueza: la economía argentina en el período 1880-1916.” Nueva Historia Argentina: El progreso, la modernización y sus límites. Lobato, Mirta ed. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana, 2000, 17-69, 19. [8] The percentage of illiterates (of more than seven years of age) fell from 18% in 1914 to 7% in 1938. Gutiérrez, Leandro and Luis Alberto Romero. “Sociedades barriales y bibliotecas populares.” Sectores Populares, Cultura y Política. Buenos Aires en la Entreguerra. Gutiérrez, Leandro and Luis Alberto Romero eds. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana, 1995, 69-105, 72. [9] Beatriz Sarlo observed that in 1935 the daily print run of newspapers and magazines was of 2,000,000 copies; there were 300,000 people in charge of distribution, and 15,000 editors, journalists and correspondents. Sarlo, Beatriz. Una Modernidad Periférica. Buenos Aires 1920 y 1930. Buenos Aires: Nueva Visión, 1999, 21. [10] Otis Elevator, Remington Rand, International Harvester; Chrysler, General Motors; Standard Electric, General Electric, IBM, RCA Victor, and Parke Davis, Merck, Colgate, Palmolive. Palacio, Juan Manuel. “La

20

antesala de lo peor: la economía argentina entre 1914 y 1930.” Nueva Historia Argentina. Democracia, conflicto social y renovación de ideas 1916-1930. Falcón, Ricardo ed. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana, 2000, 101-50, 120, 137-8. [11] See, among others, Díaz, Augusto. “Las mujeres de hoy: Josefina Backer.” El Hogar 14 December 1928: 29; “Entrevista a Josephine Backer.” Caras y Caretas 11 February 1928: unpaginated. [12] Crítica, 8 December 1919: p. 5. [13] El Hogar 5 October 1928: 41. See also “En las playas americanas. Concursos de belleza.” Atlántida 7 July 1927: 62-3. For European beauty contests, see El Hogar 15 March 1929: 37; “Bellezas Europeas.” Atlántida 19 September 1929: 32-3. [14] “La mujeres modernas.” Caras y Caretas 10 September 1927: unpaginated. [15] “El grupo de mujeres más frescas del mundo.” Crítica 22 February 1922: 5. [16] Crítica 2 March 1926: 16. [17] Pepsodent ad, Para Ti 15 December 1931: 34. [18] Sylvia Sidney Lux ad. Para Ti 2 July 1935: 31; Claudette Colbert Lux ad. El Hogar 2 June 1939: 31; Lupe Vélez Lux ad. Para Ti, 23 July 1935: 31. [19] For the case of Chile, see Rinke, Stefan “Voyeuristic Exoticism or the Multiple Uses of the Image of U.S. Women in Chile.” North Americanization of Latin America? Culture, Nation and Gender in Inter-American Relations. König, Hans-Joachim and Stefan Rinke eds. Stuttgart: Heinz, 2004, 159-180. [20] Rey, Manuel. “El noviazgo es en Estados Unidos una amistad exenta de romanticismo.” El Hogar 8 October 1937: 14. [21] Rey, Manuel. “En los Estados Unidos la mujer es una peligrosa competidora del hombre.” El Hogar 5 November 1937: 14. [22] Villalobos, Alejandro. “Lo interesante y pintoresco del divorcio son los motivos que invocan los que se divorcian.” Mundo Argentino 28 February 1934: 52, 53, 65. [23] Davis, Lilia. “Las niñas argentinas tienen un gran sentido de la feminidad.” El Hogar 21 April 1933: 17, 67. [24] Davis, Lilia. “Los maridos argentinos no son lo más perfecto del mundo.” El Hogar 28 April 1933: 17. [25] Madariaga, José Manuel. “Contestando a un artículo de Lilia Davies: ¿Somos peores que otros, los maridos argentinos?” El Hogar 5 May 1933: 17, 80. [26] Quiroga, Horacio. “Las Amazonas.” El Hogar 17 January 1930: 8. [27] “¿Hacia la supresión de los encantos femeninos?” Caras y Caretas 5 February 1927: unpaginated. [28] The modern girl was sometimes called mujer moderna (modern woman) and other times joven moderna or muchacha moderna (modern girl). I see the two terms as equivalent since they always refer to young women. [29] Jordán, Luis María. “De la vida Nacional. El espíritu nacional.” El Hogar 1 February 1918: unpaginated. [30] Jordán, Luis María. “De la vida Nacional. El espíritu femenino.” El Hogar 29 March 1918: unpaginated. [31] De España, José. “Velocidad y Modernismo.” El Hogar 24 March 1933: 64, 80. [32] Martínez Estrada, Ezequiel. Radiografía de la Pampa. Buenos Aires: Hyspamérica, (1933)1986, 327.

21

[33] Madero, Graciela. “Los peligros del modernismo.” Para Ti 9 July 1935: 30. This argument appeared in several articles. See, among others, Blanca, Rosa. “Ejemplos inconvenientes.” Para Ti 26 October 1937: 101; Pascarella, Luis. “Antiyanquismo lírico.” El Hogar 19 June 1925: 14, 59. The authors argued that foreign films, fashion and literature were perverting Argentine gender patterns. [34] For a similar approach to this story, which however focuses more on the class status of the joven moderna, see Tossounian, Cecilia. “Configuring Modernity and National Identity: Representations of the Argentine Modern Girl (Buenos Aires 1920-1940).” Krasnick Warsh, Cheryl and Dan Malleck eds. Consuming Modernity: Gendered Behaviour and Consumerism before the Baby Boom. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press: forthcoming 2013. [35] “La Beba: Historia de una vida inútil.” Caras y Caretas 11 June 1927: unpaginated. Consuelo Moreno de Dupuy de Lôme wrote for several magazines under the pseudonym of Roxana. She was one of the first journalists of the country and also worked as a high school Inspector and in the Consejo Nacional de Mujeres, doing beneficent activities. Sosa de Newton, Lily. Diccionario Biográfico de Mujeres Argentinas. Buenos Aires: Plus Ultra, 1986, 427. I would like to thank Julia Ariza for sharing this information. [36] “La Beba ya está en sociedad.” Caras y Caretas 2 July 1927: unpaginated. [37] “Beba va al cine por la tarde.” Caras y Caretas 30 July 1927: unpaginated. [38] “Beba se baña en el mar.” Caras y Caretas 26 January 1928: unpaginated; “Beba aprende a bailar el Charleston.” Caras y Caretas 10 September 1927: unpaginated. [39] “Beba va a comprar libros.” Caras y Caretas 5 November 1927: unpaginated. The reference is to Victor Margueritte’s novel La Garçonne, published in Paris in 1922, which enjoyed a huge success and caused great controversy in Argentina. [40] “La Beba se presenta en sociedad.” Caras y Caretas 25 June 1927: unpaginated. [41] “Beba asiste a lecciones de baile.” Caras y Caretas 29 October 1927: unpaginated; “Beba aprende a bailar el Charleston.” Caras y Caretas 10 September 1927: unpaginated. [42] Lunfardo is understood as a collection of words brought by the immigration process of the turn of the century and used by the working classes of Buenos Aires. Gobello, José. Nuevo Diccionario Lunfardo. Buenos Aires: Corregidor, 2008, 9. [43] “Beba canta tangos.” Caras y Caretas 3 December 1927: unpaginated. [44] Nava, Mica. “The Cosmopolitanism of Commerce and the Allure of Difference: Selfridges, the Russian Ballet and the Tango, 1911-1914.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 1.2 (1998): 163-96, 179. [45] “Beba regresa del crucero.” Caras y Caretas 22 October 1927: unpaginated. [46] “Beba frente al modernismo que avanza.” Caras y Caretas 7 January 1928: unpaginated. [47] “Beba se tutea con sus amigos.” Caras y Caretas 10 December 1927: unpaginated. [48] “Beba es ahora una señora casada.” Caras y Caretas 24 March 1928: unpaginated.

22

Works Cited Altamirano, Carlos. “La fundación de la literatura argentina.” Ensayos Argentinos: De Sarmiento a la

Vanguardia. Altamirano, Carlos and Beatriz Sarlo eds. Buenos Aires: Ariel, 1997, 201-09. Print.

Chatterjee, Partha. The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories. Princeton: Princeton

University Press, 1993. Print.

Cooper, Frederick. Colonialism in Question: Theory, Knowledge, History. Berkeley: University of California

Press, 2005. Print.

Delaney, Jean. “Imagining El Ser Argentino: Cultural Nationalism and Romantic Concepts of Nationhood in

Early Twentieth-Century Argentina.” Latin American Studies 34.3 (2002): 625-65.

De Grazia, Victoria. Irresistible Empire: America’s Advance Through Twentieth-Century Europe. Cambridge:

Belknap Press, 2005.

Gobello, José. Nuevo Diccionario Lunfardo. Buenos Aires: Corregidor, 2008. Print.

Gutiérrez, Leandro and Luis Alberto Romero. “Sociedades barriales y bibliotecas populares.” Sectores

Populares, Cultura y Política. Buenos Aires en la Entreguerra. Gutiérrez, Leandro and Luis Alberto

Romero eds. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana, 1995, 69-105. Print.

Hershfield, Joanne. Imagining la Chica Moderna: Women, Nation, and Visual Culture in Mexico, 1917-1936.

Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2008. Print.

Joseph, Gilbert. “Close Encounters: Toward a New Cultural History of U.S.-Latin American Relations.” Close

Encounters of Empire: Writing the Cultural History of U.S.-Latin American Relations. Joseph, Gilbert,

Catherine Le Grand, Ricardo Salvatore eds. Durham (N.C.): Duke University Press, 1998, 3-46.

Print.

Kandiyoti, Deniz. “Identity and its Discontents: Women and the Nation.” Millennium: Journal of International

Studies 20.3 (1991): 429-43.

Karush, Matthew. “The Melodramatic Nation: Integration and Polarization in the Argentine Cinema of the

1930s.” Hispanic American Historical Review 87.2 (2007): 293-326.

Kitch, Carolyn. The Girl on the Magazine Cover: The Origins of Visual Stereotypes in American Mass Media.

Chapel Hill, NC: University of Chapel Hill Press, 2001. Print.

Latham, Angela. Posing a Threat: Flappers, Chorus Girls, and Other Brazen Performers of the American

1920s. Hanover: University Press of New England, 2000. Print.

23

López, Ana M. “‘A Train of Shadows’: Early Cinema and Modernity in Latin America.” Through the

Kaleidoscope: the Experience of Modernity in Latin America. Schelling, Vivian ed. London and New

York: Verso, 2000, 148-76. Print.

Nava, Mica. “The Cosmopolitanism of Commerce and the Allure of Difference: Selfridges, the Russian Ballet

and the Tango, 1911-1914.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 1.2 (1998): 163-96.

Palacio, Juan Manuel. “La antesala de lo peor: la economía argentina entre 1914 y 1930.” Nueva Historia

Argentina. Democracia, conflicto social y renovación de ideas 1916-1930. Falcón, Ricardo ed.

Buenos Aires: Sudamericana, 2000, 101-50. Print.

Peiss, Kathy. Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York.

Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986. Print.

Plotkin, Mariano. “Tell me your Dreams: Psychoanalysis and Popular Culture in Buenos Aires, 1930-1950.”

The Americas 55.4 (1999): 601-29.

Rinke, Stefan “Voyeuristic Exoticism or the Multiple Uses of the Image of U.S. Women in Chile.” North

Americanization of Latin America? Culture, Nation and Gender in Inter-American Relations. König,

Hans-Joachim and Stefan Rinke eds. Stuttgart: Heinz, 2004, 159-180. Print.

Roberts, Mary Louise. Civilization without Sexes: Reconstructing Gender in Postwar France, 1917-1927.

Chicago and London: Chicago University Press, 1994.

Rocchi, Fernando. “Consumir es un placer: la industria y la expansión de la demanda en Buenos Aires a la

vuelta del siglo pasado”. Desarrollo Económico 37.148 (1998): 533-58.

-----. “El péndulo de la riqueza. La economía argentina en el período 1880- 1916.” Nueva Historia Argentina.

El progreso, la modernización y sus límites. Lobato, Mirta ed. Buenos Aires: Sudamericana, 2000, 1

7-69. Print.

-----. “Inventando la Soberanía del Consumidor”. Historia de la vida privada en la Argentina: La Argentina

plural 1870-1930. Devoto, Fernando and Marta Madero eds. Buenos Aires: Taurus, 1999, 301-21.

Print.

-----. “La Americanización del Consumo: Las Batallas por el Mercado Argentino, (1920-1945).”

Americanización: Estados Unidos y América Latina en el siglo XX. Barbero, María and Andrés

Regalsky eds. Buenos Aires: EDUNTREF, 2003, 131-89. Print.

Romero, José Luis. “La ciudad Burguesa.” Buenos Aires: Historia de Cuatro Siglos. Romero, José Luis and

24

Luis Alberto Romero eds. Buenos Aires: Abril, 1983, 9-17. Print.

Romero, Luis Alberto. “Una empresa cultural: los libros baratos.” Sectores Populares, Cultura y Política.

Buenos Aires en la Entreguerra. Gutiérrez, Leandro and Luis Alberto Romero eds. Buenos Aires:

Sudamericana, 1995, 45-67. Print.

Salvatore, Ricardo. “Yankee advertising in Buenos Aires. Reflections on Americanization.” Interventions 7.2

(2005): 216-35.

Sarlo, Beatriz. El Imperio de los sentimientos. Narraciones de circulación periódica en la Argentina, 1917-

1927. Buenos Aires: Norma, 2000. Print.

Sarlo, Beatriz. Una Modernidad Periférica. Buenos Aires 1920 y 1930. Buenos Aires: Nueva Visión, 1999.

Print.

Sinha, Mrinalini. “Gender and Nation”. Women’s History in Global Perspective. Bonnie Smith ed. Urbana and

Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004, 229-74. Print.

Sosa de Newton, Lily. Diccionario Biográfico de Mujeres Argentinas. Buenos Aires. Plus Ultra, 1986. Print.

The Modern Girl Around the World Research Group: Barlow, Tani, Madeleine Yue Dong, Uta G. Poiger, Priti

Ramamurthy, Lynn M. Thomas, and Alys Eve Weinbaum. “The Modern Girl around the World: A

Research Agenda and Preliminary Findings”. Gender and History 17.2 (2005): 245-94.

The Modern Girl around the World Research Group. “The Modern Girl as Heuristic Device: Collaboration,

Connective Comparison, Multidirectional Citation.” The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption,

Modernity and Globalization. The Modern Girl Around the World Research Group. Weinbaum, Alys

Eve, Lynn Thomas, Priti Ramamurthy, Uta Poiger, Madeleine Yue Dong, and Tani Barlow eds.

Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2008, 1-24. Print.

Tossounian, Cecilia. “Configuring Modernity and National Identity: Representations of the Argentine Modern

Girl (Buenos Aires 1920-1940).” Krasnick Warsh, Cheryl and Dan Malleck eds. Consuming

Modernity: Gendered Behaviour and Consumerism before the Baby Boom. Vancouver: University of

British Columbia Press: forthcoming 2013.

Von Ankum, Katharina ed. Women in the Metropolis: Gender and Modernity in Weimar Culture. Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1997. Print.

Sources

“¿Hacia la supresión de los encantos femeninos?” Caras y Caretas 5 February 1927: unpaginated.

25

“Beba aprende a bailar el Charleston.” Caras y Caretas 10 September 1927: unpaginated.

“Beba aprende a bailar el Charleston.” Caras y Caretas 10 September 1927: unpaginated.

“Beba asiste a lecciones de baile.” Caras y Caretas 29 October 1927: unpaginated.

“Beba canta tangos.” Caras y Caretas 3 December 1927: unpaginated.

“Beba es ahora una señora casada.” Caras y Caretas 24 March 1928: unpaginated.

“Beba frente al modernismo que avanza.” Caras y Caretas 7 January 1928: unpaginated.

“Beba regresa del crucero.” Caras y Caretas 22 October 1927: unpaginated.

“Beba se baña en el mar.” Caras y Caretas 26 January 1928: unpaginated.

“Beba se tutea con sus amigos.” Caras y Caretas 10 December 1927: unpaginated.

“Beba va a comprar libros.” Caras y Caretas 5 November 1927: unpaginated.

“Beba va al cine por la tarde.” Caras y Caretas 30 July 1927: unpaginated.

“Bellezas Europeas.” Atlántida 19 September 1929: 32-3.

“El grupo de mujeres más frescas del mundo.” Crítica 22 February 1922: 5.

“En las playas americanas. Concursos de belleza.” Atlántida 7 July 1927: 62-3.

“Entrevista a Josephine Backer.” Caras y Caretas 11 February 1928: unpaginated.

“La Beba se presenta en sociedad.” Caras y Caretas 25 June 1927: unpaginated.

“La Beba ya está en sociedad.” Caras y Caretas 2 July 1927: unpaginated.

“La Beba: Historia de una vida inútil.” Caras y Caretas 11 June 1927: unpaginated.

“La mujeres modernas.” Caras y Caretas 10 September 1927: unpaginated.

Blanca, Rosa. “Ejemplos inconvenientes.” Para Ti 26 October 1937: 101.

Claudette Colbert Lux ad. El Hogar 2 June 1939: 31.

26

Crítica 2 March 1926: 16.

Crítica, 8 December 1919: p. 5.

Davies, Lilia. “Las niñas argentinas tienen un gran sentido de la feminidad.” El Hogar 21 April 1933: 17, 67.

Davies, Lilia. “Los maridos argentinos no son lo más perfecto del mundo.” El Hogar 28 April 1933: 17

De España, José. “Velocidad y Modernismo.” El Hogar 24 March 1933: 64, 80.

Díaz, Augusto. “Las mujeres de hoy: Josefina Backer.” El Hogar 14 December 1928: 29.

El Hogar 15 March 1929: 37.

El Hogar 5 October 1928: 41.

Gálvez, Manuel. “Una mujer muy moderna.” Una mujer muy moderna. Buenos Aires: Tor, 1951 (1927). Print.

Jordán, Luis María. “De la vida Nacional. El espíritu femenino.” El Hogar 29 March 1918: unpaginated.

Jordán, Luis María. “De la vida Nacional. El espíritu nacional.” El Hogar 1 February 1918: unpaginated.

Lupe Vélez Lux ad. Para Ti, 23 July 1935: 31.

Madariaga, José Manuel. “Contestando a un artículo de Lilia Davies: ¿Somos peores que otros, los maridos

argentinos?” El Hogar 5 May 1933: 17, 80.

Madero, Graciela. “Los peligros del modernismo.” Para Ti 9 July 1935: 30.

Martínez Estrada, Ezequiel. Radiografía de la Pampa. Buenos Aires: Hyspamérica, (1933) 1986.

Pascarella, Luis. “Antiyanquismo lírico.” El Hogar 19 June 1925: 14, 59.

Pepsodent ad, Para Ti 15 December 1931: 34.

Quiroga, Horacio. “Las Amazonas.” El Hogar 17 January 1930: 8.

Rey, Manuel. “El noviazgo es en Estados Unidos una amistad exenta de romanticismo.” El Hogar 8 October

1937: 14.

27

Rey, Manuel. “En los Estados Unidos la mujer es una peligrosa competidora del hombre.” El Hogar 5

November 1937: 14.

Sylvia Sidney Lux ad. Para Ti 2 July 1935: 31.

Villalobos, Alejandro. “Lo interesante y pintoresco del divorcio son los motivos que invocan los que se

divorcian.” Mundo Argentino 28 February 1934: 52, 53, 65.