Don't Play it Again Sam: Radio Play, Record Sales, and Property Rights

"I don't like it, I don't love it, but I do it and I don't mind": Introducing a framework for...

-

Upload

westernsydney -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of "I don't like it, I don't love it, but I do it and I don't mind": Introducing a framework for...

Curriculum PersPectivesAustralian Curriculum Studies Association

EditorProfessor KerrY KennedY

Hong Kong Institute of Education

Associate EditorsProfessor Kathrym MoYle

Australian Councii for Educational

Research

Editorial BoardProfessor Marie Brennan

Victoria UniversitY,

Victoria

Emeritus Professor Christine Deer

University of TechnologY SYdneY,

Ner,r'South Wales

Professor Barry Fraser

Curtin UniversitY of TechnologY,

Western Australia

Professor Bill Green

Charles Sturt Universiry

New South Wales

Dr Catherine HartCrowther Centre for Learning and

Innovation, Universlty of Newcastle

(Conjoint Fellow)

EacheditlonofCuticulumPerspectivesisdedicatedtothememolyofitsinauguralEditor,ColinMarsh.Colineditedthis|ournalwithdistlnctionfromlgS0-2012andwasACSl(sFoundationPresident.TheACSAExecutivehonoursColin,sscholarshipandhislegacy.

CurriculumPerspectivesispublishedbytheAustlalianCurriculumstudiesAssociation(ACSA).Therearewvoeditio.ns;thejournaledition,whichisnormallypublishedinApriland September, and the newsletter edition, which is normally eublish:1]n 1:1e indNovember. Views expressed by the authors do not necessarily represent the view of ACSA'

Curriculum Perspectives welcomes contdbutions on all matters relating to curriculum

development, evaluation and theory' Correspondence' manuscripts and.books for review

should be sent to ACSA at the ad.dress below, or by e-mail to cp@acsa'edu'au'

Businesscorrespondence,includingordersandle4ittanceslelatingtosubsCdptions,adveftisements and back issues should be sent to ACSA'

OAustralianCurriculumstudiesAssociationlncorporated2o|4ISSN 0159-7868

This work is copyT ight. Apart from any use as permitted under the CoPyrisht Act 1968'

no part may be reploduced by any process without wdtten permission from ACSA'

Requests and inquiries .ottce'nittg reproduction rlghts should be directed to the

Lrecutir e Director, ACSA'

-{ustratian Curriculum Studies Association (ACSA)

E\r Blr\ 331. Deakin \\tst ACT 260O Tel: (OZ) 6260 5660 Fax: (OZ) 6260 5665

\h::es relating to Curriculum Perspectives: cp@acsa'edu'au

!.€r--r---a- erqui:ies: acsa@acsa'edu'au Web: www'acsa'edu'au

]::m 1,:* .1.:,rr-:sed \o, l3]{-l I0Ol0'l

Associate Professor Deborah Henderson

Queensland University of Technology

I)r Amanda Keddie

University of Queensland,

Queensland

Professor Jane KenwaY

Monash UniversitY,

Victoria

Dr Michael KindlerPrincipal, Stromlo High School,

Australian CaPital Territory

Professor Paul MorrisInstitute of Education, University

of London, United Kingdom

Professor KaY WhiteheadFlinders UniversitY,

South Australia

Professor LYn Yates

UniversitY of Melbourne,

Victoria

Executive DirectorKatherine Schoo

ACSA

Consulting EditorsAssociate Professor David Carless

UniversitY of Hong Kong,

Hong Kong

Emeritus Professor Michael Connelly

Ontario Institute for Studies inEducation, Canada

Professor Ivor Goodson

UniversitY of Brighton,

United Kingdom

Dr Xu JiaCurtin UniversltY,

Western Australia

Design and formattingAngel Ink, Canberrd

PrintingParagon Printers, Canberra

Curriculum PerspectivesFoundation Editor: Colin l. Marsh

Volume 34, Number 3, 2014Edited by Kerry [. Kennedy

,&x*&e$ex

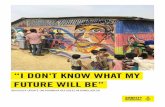

"I don't like it, I don't love it, but I do it and I don't mind": 1

Introducing a framework for engagement with mathematicsCatherine AttardThe effects of standards-based reforms on Indigenous students, 15

access to English as a Second Language curriculum andopportunities to learnLisl Fenwick

"It's a bit hard to tell, isn't it": Identifying and analysing intentions 27behind a cross-curriculum prioritylacinta Maxwell

Exploring the Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages 39Briqn Devlin, Michael Christie, Cotherine Bow, Patricia loyand Rebecca Green

Democracies and democratic education: Reflections from liberal 48and communitarian perspectives

Leonel Lim

$3o&sx& amx* eswrx*erp*&&X

Winanga-y Bagay Gaay: Know the river's story 59A conversation on Australian curriculum betweenfive Indigenous scholars

Kevin Lowe, Vincent Backhaus, Tyson Yunkaporta, Lilly Brown

and Ssrah Loynes

First layer-Mountains to sea 63

Second layer-Water shapes river banks 69Third layer-Landscape moves, grows 74

Fourth layer-Layers of landscape 80

Book reviewAsia's High Performing Education Systems: The Case of Hong Kong 92

Contribax&CIrs 93

Notes ferx' *rx&eme*Xmq aomtr$bxtors

Menxbcrs*x&p app&$eae&xm

95

96

jge

AS

AS

the

rok

"I don't like it, I don't love it, but I do itand I don't mind": Introducing a frameworkfor engagement with mathematics

Catherine Attard

:t!tf&{e--15 ARTICLE lS an introduction to the Framework for Engagement

".'rth Mathematics (FEM), a framework that provides insight for

:l-rcators into the foundations necessary for students to engage

' ,rh mathematics. The framework is the result of a qualitative,

:-gltudinal study of the influences on student engagement

- -:ing the middle years of schooling. Although much has been

--::en about what good mathematics teaching should look like

-:- : several frameworks are available for educators to use as a

' :el for good teaching, continuing negative attitudes and

- :::t{agement with mathematics both imply that teachers may

. :.- accessing the frameworks or the frameworks themselves

.':r.r,taddressingstudentneeds.TheFEMhighlightsthatitis.-:-nply the pedagogical repertoires or the resources that

- - -::s use that influence student engagement, it is the deeper

..:oedagogicalrelationshipsthatdevelopbetweenstudents. ' - :.,chers that are a necessary foundation for engagement to

:=lrple attribute an anxiety or dislike of mathematics to

:r-:.i1ences during the middle years of schooling, avoiding'::'.r:rcs as a result of negative experiences (Boaler, 2009;

: " i ,r'i-o enjoyed and was engaged with mathematics during- --.::',' school years but became disengaged with the subject

- ..: :rst two years of secondary education' The purpose

.* :-e ls to introduce a Framework for Engagement with" :-':..-S ifEM), a framework that may provide insight for

" :, ,:.:t the foundations necessary for students to engage

r - ,::l--atlCS.

' --.:-.=',vork was derived as part of a qualitative, longitu-- - :' --: the influences on student engagement during the

::r: :,i schooling (Years 5 to 9 in New South Wales)' It

.- -:med through a review of current literature on

' :-.:iiment and mathematics and then inductively' : -::-.-:: of this study, which have been reported previ-

'--, I 'rlO; ZO71a,2O77b; in press)' The final framework. : - .r. :his article emerged as an outcome of the research

- - ' .:-= rer-iew of literature. Importantly, the framework

CATHERINE ATTARD

takes student voice seriously in its consideration ofwhat engages learners in mathematics classrooms.This article will explore how the findings of thestudy directly influenced the elements of theframework through student interviews, focus groupdiscussions, teacher interviews and classroomobservations.

The main goal of the research was to investigatethe reasons why many students become disengagedwith mathematics, particularly during the middleyears. One of the central findings of the researchwas that the teacher is the strongest influence onstudents' engagement with mathematics, and thatthis influence can be separated into two distinctyet inter-related elements that form the foundationsfor engagement: the pedagogical relationshipsformed between teachers and their students, andthe pedagogical repertoires that are employed bythe teachers.

Although much has been written about whatgood teaching should look like and several frame-works are available for educators to use as a modelfor good teaching (Australian Association ofMathematics Teachers, 2006; New South Wales

[NSW] Department of Education and Training , ZOO3),

continuing negative attitudes and disengagementwith mathematics both imply that teachers maynot be accesslng the frameworks or the frameworksthemselves are not addressing student needs. Hence,another goal of this research was to provide thestudent participants with a voice in relation to theirlearning needs, specifically in mathematics. Studentvoices then became a vital component informingthe FEM, which has the potential to be used as aplanning tool for practising mathematics teachers.

The FEM is presented below in Figure 1. Followlngthis are three main sections. First, the theoreticalbackground of the study will be reviewed. Second,the context of the study will be discussed. Finally,an overview of the data that contributed to theframework will be used to illustrate its components.

The literature and theoretical framework informingthe study and the framework focused on two mainareas: research relating to the construct of engagementand its definition, and issues specific to the teachingand learning of mathematics in middle years class-rooms. Due to the limitations of this article, a briefoverview of the literature is provided.

Figure '1. Framework for Engagement with Mathematics

ln an engaging mathematics classroom, positive pedagogical relationships exist where:students' backgrounds and pre-existing knowledge are acknowledged and contribute to the learningof others

the teacher is aware of each student's mathematical abilities and learning needsinteraction amongst students and between teacher and students is continuousthe teacher models enthusiasm and an enjoyment of mathematics and has a strong pedagogical contentknowledgefeedback to students is constructive, purposeful and timely

ln an engaging mathematics classroom, engaging pedagogical repertoires mean:

': there is substantive conversation about mathematical concepts and their applications to life:r tasks are positive, provide opportunity for all students to achieve a level of success and are challenging for all:, students are provided an element of choicel' technology is embedded and used to enhance mathematical understanding through a student-centred

approach to learningI the relevance of the mathematics curriculum is explicitly linked to students' lives outside the classroom

and empowers students with the capacity to transform and reform their lives

' mathematics lessons regularly include a variety of tasks that cater to the dlverse needs of learners

Students are engaged with mathematics when:mathematics is a subject they enjoy learningthey value mathematics learning and see its relevance in their current and future livesthey see connections between the mathematics learnt at school and the mathematics used beyond theclassroom

rment

' may!\'orks

Ience,

e thetheir

:dentmingasa

EIS.

rving

rticalond,rally,

theints.

ningnain

:lent

rlnglass-

rrief

)efining engagement

.--= term engagement is used often and widely by: : -tcators when discussing students' levels of:-, olr-ement with teaching and learning; so a critical

- ':: of this study was to provide a definition of: .3g€rr€Dt that would offer a deeper understanding

:1-re concept.

\lany definitions of engagement are found in the:::ature. Some provide a narrow view that relates- ',- to behaviour and participation. Others provide

-:.eper understanding that includes more than:: dimension (Downer, Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta,

- -: Hickey, 2003). Fredricks, Blumenfeld and. s ,2004) define engagement as a deeper student

: -'.:-onship with classroom work, multi-faceted and

::ating at cognitive, emotional and behavioural,..-:. Behavioural engagement encompasses the.:: of active participation and involvement in:r.mic and social activities, and is considered

' .--a1 for the achievement of positive academic

.. .: rmes. Emotional engagement includes students'': i ,::ons to school, teachers, peers and academics,

-rencing willingness to become involved in

-.ln-ork. Cognitive engagement involves the idea' .:.\-estment, recognition of the value of learning'-, a rvillingness to go beyond the minimumi . - raments.

,: is thls multi-dimensional view of engagement,

: .--,ned with more recent, Australian research on

:j.:ement (Fair Go Team NSW Department of,,,-1tion and Training, 2006; Munns & Martin,

- : that informs the definition of engagement

- -- :or this study and within the FEM. Viewed this

, =ngagement occurs with, and can be defined as,

: .cming together' of all three facets; cognitive,

: .'-:i\-e and affective (in line with Fredricks et al.'s

- - cognitive, behavioural and emotional:.:ement) that leads to students valuing and

-,,ng school mathematics and seeing connec-

:.: between school mathematics and their own

:: '*re\-ofld the classroom.

-,-es relating to the teaching and learning:' nathematics during the middle years

. --rerature identifles a broad range of factors that' .-=nce students' engagement with mathematics.

: - rganisational purposes, these influences are

-:=tr lnto layers of influence: from outside the

: :r.lom and not necessarily specific to the mathe-

.:.r.s classroom; influences from inside the

.:):oom; and the core layer, the influence of

"l DON'T LIKE lT, IDON'T LOVE lT, BtrT rDO -

teachers and their pedagogical practices. For thepurpose of this article, the issues directly influencingthe FEM are discussed.

Outside influences include issues surroundingthe nature of adolescence in the 21st century (Bahr,

2010; Douglas Willms, Friesen & Milton, 2009;

Stevens et al.,2007), the sometimes negative impactof transition from primary to secondary schooling(for a deeper review of literature see Attard, 2010)

and the influence of family and peers (Commonwealth

of Australia, 20OB; Martin, Marsh, Mclnerney &Green, 2OO9; Ryan,2000). There also appears to be a

mismatch between the psychological needs of early

adolescents and the type of school environment they

experience. This is also influenced by emerging

technologies and their effect on the social world ofadolescents (Collins & Halverson, 2OO9; Carrington,2006; McGee, Ward, Gibbons & Harlow, 2003). These

outside influences are reflected in the FEM, where

students' backgrounds and pre-existing knowledge

are acknowledged.

Influences on student engagement from withinthe mathematics classroom include the relevance

and applicability of mathematics that sometimes

differs substantially to the mathematics students

use outside the school (Australian Association ofMathematics Teachers, ZOO9; Lowrie, 2OO4). Givet't

all of the new content that is required to meet the

demands of an increasingly technological societr

the literature argues persuasively that it is difficu-:to justify giving substantial classroom tinle : -

topics such as multi-digit long division and conl':.. '

manipulation of fractions and decimals, pr.li:.-:that are still prevalent within many mathirl-.::.,classrooms (Clarke, 2003). The issue of reler l:-.,: ,, r'

the importance of explicitly linking scl'tc-, -. :'-'matics to student' lives is included in th. .-

While there are other 'lnslde' ,:l:1 ,.. .

engagement such as the social rela:: :-.,- .

Lhe mathematics classroottt att.: .:.. . .

grouping, arguably lt is ti"ie te3.l--:: -, --

practices employed that ar. :lt= - .

students' engagement. Tlt. -, . -. - -

seen in mathetttatir\ ..:"spectrum ol pract \q- ..

student-centreC l::: :-. :

and inie(tl_.:t. :. :

tl{o eristil. -, : ,

teachins r-r:-i -::thc \\'..

CATHERINE ATTARD

Department of Education and Training, ZOO3), a

generic framework that evolved from the Productive

Pedagogy framework (Hayes, Mills, Christie &

Lingard, 2006), a result of the seminal Queensland

School Reform Longitudinal Study. The second

framework is speciflc to mathematics: The Standards

of Excellence in Teaching Mathematics in Australian

Schools (Australian Association of Mathematics

Teachers, 2006).

In order to understand how the frameworks

support the engagement of students with mathe-

matics, they were aligned so that similarities, differ-

ences and gaps could be explored. It was found that

although each of the frameworks promoted good

teaching and learning practices, gaps were identified

in relation to teacher professional development and

knowledge of how students learn mathematics (in

the NSW Quality Teaching Framework) and although

the concept of engagement was mentioned, neither

framework specifically addressed student engagement

in detail. Hence, the FEM is influenced by sugges-

tions made within both frameworks and seeks to

address the gaps that relate specif,cally to students,

pedagogl-, and engagement with mathematics.

The nert section of this article briefly describes

the conte,\t rr'lthin rr-l-tich the studr.' took place and

the methodologl' er-r"rplor-ed. This is particularly

lmpofiant, as the unique situation of the secondary

school plat,ed a significant role in the development

of the FEM. Following this, the FEM will be expli-

cated through an exploration of the data that were

collected during the studY.

*.S**&x***c{a:*x:.;

The central question of this study was: What do

students perceive to be influences that impact on

engagement with mathematics during the middle

years of schooling within an Australian setting?

In order to address the research question it was

necessary to situate the research withln a suitable

epistemology and select an appropriate research

methodology that would allow a deep exploration of

the students'insights. Hence, a qualitative case study

approach was adopted that was located within an

interpretive, social constructivism worldview within

which it is assumed that reality is socially constructed

and that there is no single, observable reality (Corbin

& Strauss, 2008; Creswe7l,2OO7; Merriam, 2009)' The

choice of the particular case was made in order to

:dvance our understanding of issues surrounding

.r-.::1gement, and although arguably this case may

not be regarded as 'typical', it is a case from which

much can be learned. Often it is the unique case

that has the most to offer in terms of providing a

stronger understanding of the phenomena being

investigated, "potential for learning is a different and

sometimes superior criterion to representativeness"

(Stake, 2005, p. 451).

The study followed a group of students across

three school years, beginning during Yeat 6, the final

year of primary school in NSW through to Year 8,

the second year of secondary school. Rather than

take a deflcit approach to teaching practices that

may not promote engagement, it was a commitment

in this study to take a positive perspective, focusing

on identification of what was seen by the partici-

pants to be working well and assisting in the mainte-

nance of positive enSagement with mathematics.

However, in order to highlight positive classroom

practice, as a result of the unique context of the

schools within this study, it was sometimes necessary

to explore negative aspects of the students' experi-

ences during the studY.

With a positive perspective as a priority, a 'high

achieving' primary school was purposely sought as

the initial site due to repeated studies showing

moderate to strong correlations between academic

achievement and academic self-concept (Barker,

Dowson & Mclnerney, 2005). It was reasoned

students who experience positive academic self-

concept in mathematics are more likely to be

engaged, and therefore a school that fitted this

criterion would be an appropriate setting from which

to explore students' engagement as they made the

transition to secondarY school.

The participants of the study took part in an

individual interview at the start and again at the

completion of the study. They also took part in a

series of focus group discussions during the

three years. Durlng these discussions the participants

had the opportunity to talk about teaching and

learning mathematics, and teachers who they

believed to be 'good' mathematics teachers. Three of

these teachers were identified by the students

and were then observed during mathematics lessons.

Two of the teachers were also interviewed in relation

to their beliefs about mathematics teaching and

Iearning.The qualitative data gathered from these sources

and the researcher's field notes were transcribed and

analysed at the end of each phase and then synthe-

sised on completion of the data collection. Initial

q'il

rOSS

inalrr 8,

hanthat

rent

;ingtici-ote-

:ics.

rom

the;ary

eri-

hichCASC

o8aeing

and

.ESS,,

ighIasingnic(er,

red

elf-

be

his

ich

:he

:e5

rdte-

al

.nalysis began simultaneously with data collection

'nd continued throughout the study until saturationccurred and nothing new was forthcoming from

::re data. Through the process of constant comparison

'nd the search for regularities within and across

:re data, axial coding resulted in a narrowing of.remes that applied to each phase of the study. These

::rernes were then synthesised across the study in:der to address the central research question and

,'--r-questions.

The selected primary school was located in the",:stern suburbs of Sydney. Half of the school: culation came from language backgrounds:ier than English and the school population was

-.l\\'n from a mix of low to mid socio-economic,rkgrounds. Twenty participants of mixed gender

:.-.d rnlxed academic ability were invited and agreed- :ake part in the project. Selection was based upon-

= students self-identifying as being engaged with--.,:hematics through the administration of Martin's

- ',t9t Motivation and Engagement Scale: High School

l:j-HS) Test User Manual, in particular the scales':.:-ing to their engagement with mathematics.

)uring the second phase of the study, all the.:..cipants progressed to their local secondary. -. rl in a neighbouring suburb. At the time the- -. ,rl ryas in its third year of operation and identified'

=.: as a 'ground breaking' learning community in': :i-oo to its curriculum, pedagogy and the physical'*,-:Llre of its classrooms, which were large, open,::::ng spaces designed to accommodate up to- >tudents at any given time. A multi-disciplinary

. ::--ach to teaching was adopted during this:. :l phase where students undertook programs

':ldr- that incorporated at least two subject

" ' : i j During the students' time in Year 7 and Year 8," : -jractices employed by the school continually

.'. =d and these changes significantly influenced: :rrticipants' engagement with mathematics,

" . -:ing rich data that informed the development, ' - . =:nement of the FEM. In the following section,

-. - ..Ltion of the FEM is discussed in relation to, :,:a gathered in this study.

*- = f ramew*yk $*y *cr{xx*€reerc*

," : r rnatl*e,x3&&&€s

- - .. :he course of the study, the participants experi-

.:.r r rr-ide range of teaching and learning situations' ,- :.:i',-their engagement levels fluctuate. Although: -:rr overwhelmingly indicated the teacher was

' : :, rgest influence on these students' engagement,

,,I DON'T LI(F - ir-- m[ il]llt -"*

this influence appears to be cc,r::.:.'- - r-, :- t- x ]

two separate, yet inter-related elen:c:---:. trt:r ',.:r_ ul

relationships and pedagogical r€pcr-i.-'=s : : --rpurpose of the FEM, pedagogical reiationsh-:! r:r: I -

the interpersonal teaching and learnin-{ relat- ::.-_ :"

between teachers and students that optln--)i :_-,:

learning of, and engagement with, nathe::::.::Pedagogical repertoires refer to the day-to-da\- te.i. :--:- -practices employed by the teacher.

Results of this study suggest that ii is diffic'j_:for students to engage with mathematics r,r-ithout ;foundation of strong pedagogical relationships. Ilcan also be argued that it is through engaginrpedagogies that positive pedagogical relationshlpsare developed, highlighting the connections betweenpedagogical relationships and engaging pedagogicalrepertoires. The two sections of the FEM detailingpedagogical relationships and repertoires are norrexplored. This is followed by a summary that inciudesthe first section of the FEM relating to students'overall engagement with mathematics.

Positive pedagogical relationshipsas a foundation for engagement

The major selection criterion for participation in thisproiect was that the students had to identifythemselves as being engaged with mathematics.With this in mind, much of the data collected duringthe first phase of the study (Year 6) was focusedaround pedagogical repertoires and what the partici-pants considered to be 'good' mathematics lessons.

However, the high level of interaction and thepositive pedagogical relationships were evident andbecame even more so as the students progressed intosecondary school where the relationships and inter-actions decreased considerably.

While the participants were in Year 6, ther'identified their current teacher, Mrs L, as someonethey perceived to be a good mathematics teacher.

When questioned, the students were able to artic-ulate several attributes directly relating to th.pedagogical relationships Mrs L had formed \rith he:students. A typical comment was: "If our task is :-- -

easy, like we're learning what other people ':=learning which is a bit low for us, she'11 ask 'js :

come over and she'll give us a different ta:i -.,.= :

harder one" (George, interview, 29 Septera:c- 1 , ,'This comment reflects the first section .-: ::.= ,":relating to the acknowledgement --:,:-:=-backgrounds and an awareness of lr:d:'.-" : -'., :r- - : - '

mathematical a bilities.

an

he

)ahe

ftsnd

ev

ofrts

ts.

)nrd

.,..CATHE.RINE ATTARD...,..:,...

The importance of positive pedagogical relation-

ships and engaging repertoires is also reflected in

the following comment, in which a student expressed

the need for good teachers to be able to differentiate

tasks, teaching strategies, and/or curriculum to suit

individual students "to be capable of teaching

different age groups so, and also if they're talking

about something not to talk too long because it

gets kind of boring and try to make it a bit fun as

well" (Fred, intetview, 8 September 2008)' When

asked about how the tasks were structured in her

'favourite' lessons, Mrs L, the teacher' made the

following comment:

Some of them were different tasks approaching

the same outcome, others' such as when I

mentioned Billy, he was the one who differen-

tiated his own task and he wanted to go on the

computer and explore volume more with

another boy. So he was able to jump somewhere

else and do that, which is what we try and

encourage. Others were of a lower ability' so

they were more "hands-on" rather than

say technology, because they needed that

connection flrst' (Mrs L, interview' 2 December

2008)

Mrs Us comments indicated her desire to cater to the

individual needs of her students and this is reflected

in the following comment from one student: "If

vou're like struggling behind she would like help you

andiikehaveasmalllittlegrouponthegtound"(Tenille, focus group, 23 October 2008)' The students

appreciated the fact that when difficulties arose'

they were able to seek and receive extra help from

their teacher within the supportive environment of

a small group rather than being singled out in front

of the entire class group'

By providing choice and allowing students to

select their own ways to extend and differentiate

tasks, Mrs L also displayed a desire to tailor learning

activities to the needs and interests of students' This

appeared to empower the students and' as articulated

in the FEM, acknowledged their pre-existing

knowledge, an attribute highly valued by the

students. A quote from this student further illustrates

Mrs Ils acknowledgement of prior knowledge: "She

asks first, if you've ever learnt this before or have you

learnt this in earlier grades' and if so " ' she would

gir-e vou a quick question about it' and then if you

iet it right, they send you off instead of having to sit

----,".'n and listen" (Nathan, focus group' 23 October

'\

Pedagogical relationshiPs and-

the tianiition to secondary school

When the students began Yeat 7 they experiencec

very different pedagogical relationships compared to

those in primary school, and these appeared tc

impact significantly on their engagement with

mathematics. This student's comment at the end of

that year articulates the impact of this: "Everyone's

excited when there's no maths' I think it's because'

not having someone explaining it to you and you

don't get it. If you don't get it that means you don't

like it. It's simple as that" (Ashley' focus group'

29 October ZOO}). This comment strengthens the

argument that positive pedagogical relationships

where teachers have knowledge of student needs

and provide engaging repertoires' as detailed in the

FEM, are required for student engagement to occur'

The structures within the school did not seem to

beconducivetobuildingrelationships,particularlvwithin the mathematics classrooms' There were

several reasons that this appeared to happen' First'

laptops were the main learning resource' replacing

textbooks, and for a signifi'cant proportion of the

school year, replacing opportunities for teacher/

student interactions. Although the laptop approach

was initially a novelty for the students' by the end of

Term 1 many of the participants were displaying

negative attitudes with regard to the dependence on

computers in the mathematics classroom' so much

so that this student cited her favourite lesson as one

in which she was allowed to use a hard-copy textbook:

My favourite was"'when we got to use a

textbook. We did it at the very start of the year

so I was like, wanted to use my Mac' which was

a bit silIy. Now I would die to use the textbook'

(MileY, focus grouP, Z4MarchrZOO9)

The student's comment regarding textbooks does not

necessarily imply that textbooks were considered

'good' teaching by the students' Rather, the students

ii, g"n.rrl felt the books provided a break from the

.orirpr,". and may have provided more opportunity

for interaction between their peers and their teachers'

Second, the mathematics lessons were taught

by a team of four teachers (none of whom were

tiained as specialist mathematics teachers)' The

cohort was split into four heterogeneous 'colour'

groups (according to the students' sport team

lotor.r, and the four teachers rotated through the

groups so that all students were taught by each of the

fourteachers.Mathematicslessonsgenerallyinvolveda brief initial introductory phase during which

a{

ted

toto

irhof

te's

15e/

'ou

n'trP,

.he

ips

:ds

:he

,1r.

toII}'ere

rst,

ng

:he

erirch

iofing

onrch

)ne

ok:

::rts were given instructions for the day's tasks,

ed by the expectation that students would--'-ete the set work individually on their laptops.--: a result of the organisation of mathematics:rs, each teacher did not have the opportunity

:-'.ch & specific group of students for two consec-

= lessons. This made it difficult for the teachers

..:rderstand each individual student's learning.-: and made it difficult to develop continuity

one lesson to the next. This, and the fact that: \r€r€ no specialist mathematics teachers oncould have led to the reliance on computer-

: -- tultion that became the only teaching resource

.::e first 10 weeks of school. Arguably the lack of.-: pedagogical content knowledge specific to:-,=matics (resulting from having non-specialist

..r:rs) impacted on the quality of the teaching.=arning, and although the students would not. .:een

aware of each teacher's qualificatlons,.,ppeared to lack confldence in their teachers'- to provide support:

.:--er- don't sit you down and say "okay, let's

.-,rn" which I know sometimes it can be boring

--: sometimes you could really use some of that

-.,.lse vou're just kind of like well I don't know' s. they're not teaching me, they're not doing

,:-..thing, they're just sitting there waiting for'-.. to do it because they think we know evely-' llg. (Alison, focus group, 1 June 2009)

--'.rtion to the unusuai teaching organisation of.::rool, the typical differences between primary,=condary school in relation to less teacher

::-,.ision and increased expectations of: - :ndence also appeared to negatively influence

,.dents' engagement levels. By the end of Year 7,

).idents/ frustrations in terms of the lack of, .:: student interactions and knowledge of.:--::' abilities and needs were apparent. This

:';nt ls representative of the group:

:::e teachers can be lust kind of rude, and go

. "vou should know it" and they won't help

: ,-r do it. And then they get angry at us for

: Joing it because we've got other things and

::aven't done it. And it's like, it's not really

. -:r-rlt because you haven't even helped us to' :r. it. (fenny, focus group, 2 October 2009)

' = irnal term of Year 7 , some participants:r:.d to feel a sense of abandonment, with'.,, of them reflecting back on their primary

experiences. This comment, typifled the

". rfithin one of the focus groups:

"l Do\

Well at primarv scir. -- 't-..: -::chase you up for things....: '" .. -stand they'd make sure \.,---. -.r'-: -:

they'd do assessments. Ii nobc,;'. ,-r --:r --

it, they'd do it with you so lou -.r--r: :.:'-and you get through it. Where in h-.:: :-..they don't chase you up, the;'lust sar . ^.'. -, .

bring this in, I mean flnish this oii ar:; :-..tomorrow they don't even remernber ... It s . :- -of hard because the teachers aren't on r'. --:

back...They say "do an assessment"...-I-her :.not chasing you up for it or making sure tha:

you know what you're doing. So it's real1v harcl.

Qenny, focus group, 2 October 2009)

It would be a reasonable conclusion from tit.students' perceptions that teachers were nc):

'chasing up' work and had difficulty recognisingthe students' needs in terms of their mathematics

learning. The students felt there was a lack oifeedback on classroom, homework and assessment

tasks. As a result they expressed that they were

unable to improve their understanding of concepts,

and said they felt as though they were falling behind

and potentially limiting their capacity for learning

more abstract mathematics.

The lack of feedback on students' work, whichHattie and Timperley (.ZOO7) describe as a necessar\-

aspect of effective teaching, compounded the decrease

in the students' engagement. Research has consist-

ently shown that feedback is a critical aspect ofpedagogical relationships because of the informatiort

avallable to teachers with regard to students' abilities

and learning needs, hence its inclusion in the FE\1.

The apparent lack of feedback could have been tl-re

result of the rotation of teachers, the total number of

students each teacher had to teach (a total of 93 Year .

students), and perhaps the logistics of keeping records.

The data show that students appeared to be unhap'.'-'

with the amount of feedback being received and t: :

appeared to be adding to the difficulties in esi,::-

Iishing positive pedagogical relationships.

Towards engagement Building relationships

The decreased opportunities for interactiort -.-- -

to difficulties forming pedagogical rel::-- -

between teachers and students during \-e.,- -

stark contrast to the participants' y\-j:r,: --:primary school. During the hn:.. '- r .:':when Lhe student, l.r__:

learning sitr,ratr: rr --. - . .

teachers and ::..:=:-. ,

qATH,ERTNE ATTARD

As a result of having to comply with Board ofStudies requirements and with the appointment ofa new school executive (principal and assistantprincipal), significant changes were implemented tothe learning structures at the school. Class timeswere reduced from 100 minutes to 75 minutes, theinterdisciplinary units of work were abandoned andthe school structure began to resemble that of a moretraditional secondary school. Although this is not anargument for conservative approaches to teachingand learning, rather it is simply an illustration of thechanges that occurred within the school and theireffects on the students' engagement. More impor-tantly, the school was able to employ several specialistmathematics teachers (out of the four mathematicsteachers in Year 8, two were specialist) and each class

group was allocated one mathematics teacher.

An encouraging outcome of the changes thatoccurred was the increased opportunity for teachers

to develop stronger pedagogical relationships withtheir students. Conversely, the students also had theopportunity of getting to know their teachers better.The importance of establishing a positive relationshipin the mathematics classroom is highlighted in thiscomment:

It's easier for them to come around and,

like...get to know what you're capable of and

not what the whole class is capable of. Because

everybody's different and they take in maths indifferent ways, and last term, Mr H, I didn'tunderstand him. I know he knew what I was

capabie of, but I just didn't understand him.(Ashley, focus group, 18 May 2010)

The students felt that they were now seen as

individuals rather than a collective. They also feltthe teachers 'cared' more about their learning, withone student making this statement:

Last year, they wouldn't care about our work,

they would just sit there and just talk, Iike just

write on the whiteboard. But this year, theywould be going around, like they're now intoour work and marking our homework every

day, if we've done it. (Elizabeth, focus group,

18 May 2010)

The students' comments in regard to the changes

in teacher practices during Year 8 overwhelminglyemphasise the importance of interaction within themathematics classroom and its affect on students':I:iasement. A critical component of the FEM is the

- :-:-:: -rous interaction among students and between-: : -:,:: r:rc Sludents. In contrast to their experiences

il

the previous year, the students now felt that if therrequired assistance from their teachers, they felt safe

in asking for help and felt that the teachers wantedto help them. This student's comment describes thechange and its effect on her:

When the teachers walk around it is easier

because when they're sitting down, like, yousort of, like last year I felt like I couldn't putmy hand up 'cause, she didn't really say much,she just wrote on the board what we had to do,

and she would just sit there, she would just

do something on the computer and I just didwhat I could in the book but what I couldn't do,

I never really tried to do it. 'Cause the teacher

wouldn't really come around and help us.

(Samantha, focus group, 18 May 2010)

Almost all of the students felt as though their teachers

were more able to cater to their individual needs due

to the regularity of contact and the clearly definedclass groups. The provision of feedback, as mentionedearlier, also enhanced the perception that theteachers 'care'for their students. It also implied thatassessment was now being used to inform teachers

rather than just as a record of achievement. The

accountability that the students now felt as a resultof teachers regularly marking work and providingfeedback is reflected in the following statement:

Yeah we get more individual attention and thisyear they actually like take our books home and

they mark it. Like they used to iust go through itand if you haven't flnished it, they didn't really

care very much. Once in a blue moon they'dcheck it. But now they actually take the books

home and you're kind of like more stressed outto get it done and all that but yeah, and once

you're done, you're like "yes" I've done mymaths. I think it's like, different because last year

we didn't have any tests. I think we just had an

assessment. This year, when I was with Mr H last

term, he gave us like a pop quiz then he'd give

us the mark, then we'd actually have a proper

test. (Kristie, focus group, 18 May 2010)

The students' experiences of pedagogical relation-ships in Year 8 were in direct contrast to their Year 7

experiences, highlighting the critical role of theteacher when it comes to maintaining or increasing

engagement with mathematics. This commentencapsulates this:

If you like the teacheq you'll "get" maths more.

You'll know what's going on more. And the best

way to enjoy maths is to concentrate and really

.rok at the board and understand everything'

- irat way when you go on to a task you go "oh'

- know that" and you can get the question done

.,'.:ter. Just really concentrate and try to iike it'

-.nny, intewiew 17 MaY ZOTO)

: the students felt they needed to 'like' their

-.r.rs in order to 'like' mathematics' They also

.:d to feel as though they were ln a safe

.,r-Lment in which they could ask questions and

:t the teacher to assist them without the risk of

:--l into trouble for not knowing' The following

.:-.nt illustrates this sentiment: "it makes you

.\e \rourre safe and you're happy' you know

: {oing to have a fun lesson rather than just

. ,it. you might get in trouble for something"

,' intetview, 77 iMay 2010)' Another student

.'. sinilar comment, implying things had been

.: :ierent for the students during the previous

rrn, he's really good' If we don't understand

. .rtg he'll explain it, he won't shout at us or

: :l-iat we're doing it wrong" (Rhiannon'

."^ 17 May 2010)' It appeared that the issues

' -.:r1 surrounding pedagogical relationships

::: e\perienced during Year 7 ' quality commu-

.- \ teacher availability for assistance and

, :l{ students' needs, were no longer causing

. ,. rlegree of anxiety among the students and

.- -,1 be iargely resolved due to the reorgani-

::--at had occurred' As discussed at the

--: of this section, the formation of positive

- : ;at relationships forms a foundation from

::-.Ja$eilI€nt can develop and there is a strong

: . :e r those relationships and the pedagogical

..) .mployed by the teachers' The data

- -l ,n this section was only a small example of

'.. - -'llected in the study' However' it illustrates

. i..tion of the FEM relating to pedagogical

' -,lrrs (Figure 2)' The next section of the FEM

- :red articulates the repertoires identif,ed

--:r and by the students as engaging'

Pedagogical rePertoire: f :-'

promote engagement

During each Phase .: :".-- '

had manY oPPortulliI (: -'

pedagogies, which, duritir- :-''

often saw a conflict betrveen --'r:l: -- - :

classroom experiences' The an--- --:'-'

resulting from the use ol' co' l':--.'allowed the students and teacher lll;: -'

nities for substantive conversatlon Tll : ''" "'to provide students with deeper undersi;:---''' -

mathematics concepts, with one student :''''' :--

"You've got more options to choose froilt r'':'--:'

than if you're by yourself" (George' focus gro-'-:

23 October 2008) and another: "Working rvLii'

partners is fun because you could find differetl:

strategies and you have fun and it's easier" (Dean'

focus group, 23 October 2008)' In addition to the

academic benefits of cooperative learning' the

students reported that lessons were 'fun' when

working together. The ability to associate learning

in mathematics as fun is a powerful influence on

engagement, and the following quote sums up the

collective feeling of the participants: "The group

can work it out together to try and solve the problem

and you've like learned something new or how to

work out something" (Lisa, focus group' 23 October

2008).

'High affective' mathematics lessons

Inordertoidentifypedagogiesthatengage'theparticipants were asked to recall and describe a 'fun'

or favourite mathematics lesson' They were able to

quickly recall such a lesson and articulate man\-

positive aspects of classroom pedagogy that had

positlve influences on their engagement' Most of the

lessonsoractivitiescitedasbeingafavouriteortl'tcmost fun were those that were student-centred atl':

included physicat activity' active learning situatiotl:

-; rr

- -:- -'l]-i - i

llqiluir*€ 2 )ositive pedagogical relationships

- ; - tngaging mathematics classroom' positive pedagogical relationships exist where:

.']:its,backgrounds and pre-existing knowledge are acknowledged and contribute to the learning ci

-=.:acherisawareofeachstudent'smathematicalabilitiesandlearningneeds

---eraction amongst students and between teacher and students is continuous

...'=achermodelsenthusiasmandanenioymentofmathematicsandhasastrongpedagogical.c.

lLr

:,: "iledge

"+eiback to students is constructive, purposeful and timely

94T,H ERrN E ATTARD

involving concrete material, and/or games. Varietyin classroom activities also appears to have a positiveinfluence on students' engagement.

Another aspect of the memorable and 'fun'lessons appears to have been the links made between

'real' life and mathematics, highlighting the impor-tance of relevance and linking mathematics tostudents' lives beyond the school. The incorporationof such tasks appears to have been a strong factorin engaging students with mathematics tasks, as

were the tasks that required the students to take themathematics out of the classroom and into theschool playground. One student recalled a memorable

lesson that involved going outside: "We went downto the sand pit and we got some sand and we had tomeasure. We made these little boxes with an open lidand like cubes and rectangles and stuff" (fenny, focus

group, 23 October 2008). Interestingly, when asked

about a favourite lesson she had taught, Mrs L cited

the same lesson and could see how the incorporationof relevant activities that included hands-on activ-ities and took students outside the classroom could

engage learners of all abilities, reflecting several

aspects of the FEM.

ICT as pedagogy

As discussed in the previous section, the pedagogical

repertoires experienced by the students as they began

Yeat 7 were very different to those described earlier.

The initial reliance on either a traditional textbook(accessed via CD-Rom) or a commercial, interactive

mathematics website (subscription based) and an

emphasis on individual learning was vastly different

to the range of hands-on and interactive mathe-

matics lessons experienced during primary school.

Although their initial reaction to the constant use ofcomputers was one of excitement, the participants

soon reported missing the interactions with theirteachers, each other and with concrete materials.

This comment reflects others made by the group:

Most people are flnding it difflcult because you,

like all you're using is your textbook, you're not

using counters any more, you're not using like

you know, beads, and stuff like that. And now

vou're iust basically writing it off the computer.

,Lnd you don't have time to work it out. (|enny,

iocus group, 24 March 2009)

- :-e use of laptops as the main resource during..::: 1 contrasts with the practices promoted in-.::=:-a::cs education literature on the use of

l

& Chinnappan, 2008). Although the availabilirr- ;,r

computer technology provided the opportunitv fc,r

teachers to deliver a new and relevant way of teaching

and learning (Collins & Halverson, 2009), theiinstead appeared to be used as replacements fciteachers. This student picked up this emerging ida,among the students:

It's probably not the best way of learning because

last year at least if you missed the day that they

taught you, you still had groups so your group

could tell you what was happening. Where now,

we've got the computers...but if you don'tunderstand it, it's really, hard to understand.

(Alison, focus group, 24 March 2OO9)

It is reasonable to suggest that the website anc

textbook were not necessarily bad resources. Hower-er

the data was showing that it was the way therwere used in isolation that meant the students were

beginning to disengage from mathematics. The

reliance on the computers and the way they were

embedded within a conservative pedagogy led to a

lack of interaction among students and between

teachers and students.

'Routine' pedagogical routines

As the year progressed the participants began to

experience a slightly broader range of learning and

teaching resources and practices, with less use of

computers. This student described the changes in the

pedagogical repertoires during this time:Maths has been a lot better. It's not as boring as

doing the same thing over and over again on

(the commercial website). We've been doing

more interactive with the drawing and the

measuring with the ruler and Sketchup and

all these other programs. (George, focus group,

1 June 2009)

Eventually the pedagogical repertoires appeared to

settle into a conservative routine of textbook-based

work with little or no incorporation of hands-on

activities, cooperative learning, or concrete materials.

The students appeared to become accustomed to

these routines and claimed they were better than the

computer-based lessons. Although research has found

the traditional textbook approaches do not enhance

engagement with mathematics (Boaler, 2000; Nardi

& Steward, 2OO3), and current frameworks promote

a more student-centred approach (Australian

Association of Mathematics Teachers, 2006; NSW

Department of Education and Training, 2003), these

students found this approach less disengaging than

!rltor

a,

OI

aa

. : the pedagoglcal routines experienced at the- .:-.-lg of their secondary schooling experience. It

'-rossible to gauge whether such traditional,:s continued to result in sustained student

- .::lent beyond the scope of this current study." . ;r-i the students progressed to year g, the most.,::tental difference in their mathematics lessons' -= change to having one regular teacher rather,: -otation of four teachers. The textbook_based-: continued to dominate the pedagogical

- -:s, \,et although it has been found that this' :.! may have a negative influence on student

-.*:::rent, in this case the students saw it as an- ' .ntent on previous pedagogies and appeared

=:ience higher levels of engagement. It could': :rglled that because the students had begun.' =-op more positive pedagogical relationships' -..ir teachers, they were more open to becoming

-. r.,- u-ith mathematics.. : aspect of the teachers' pedagogies that had

.-. r effect on the students' engagement was the-.,: perceptions of an improvement in teacher"..:ions, indicating more opportunity for higher

, . . engagement and substantive conversation', :rq mathematics. One student made this

::-,: rvhiCh reflected the feelings of many of the: - :. "i think maths has improved because the. , lo through it with you more, whereas last- '=,' rvould just set you a task and leave you" George, interview, 18 May 2OlO).

- :: ^'r,5' recommendations to teachers

, ..:d of the study, the participants were asked' .:. some advice for their teachers in relation

- r'lng mathematics lessons. The students:: the following recommendations which

: - '.,'-th literature and conflrmed their inclusion, ::\1. They said there should be more:

--:i

-.:::uctive feedback and praise;

.,' iearning;'. . learning;

.:a:

: :::,,119 outside the classroom;

-.'ration of concepts;'::,.-Ctlorr with students and teachers;'., :o real life;

"' --: interaction and activities;':::-','itv within the design of tasks.

'DO\irKi - ll\.--:,: -:_- ,_ -

It is interesting that the recomr-r-rendatioll::,::those espoused by much of the literature on qua.1:rteaching and learning (see for example, -{skerr-,Brown, Rhodes, Wiliam &Johnson, 1992; AustralianAssociation of Mathematics Teachers, 2006; Haveset al., 2006), and are in conflict with the conservativepedagogical repertoires the students were currentlyexperiencing. At the conclusion of the study whenasked whether they were still engaged with mathe-matics, the students were reminded of theirinterview and focus group responses from year 6.Several of the students found that although theycor-rld 'pr.rt up I.r-ith it', ther. could not commit tosaving ther llked it. This response appeared to beone of disappr611111.1l.ntt 'l ierl a bit let doir-n bt-ml, nfatl-ts Itgrr f g.;-.i.= :--. '- . .-'..- -:::-:,.lrla- 1S

slon'ing dorr n lu'... . :.: ..':.t . -:. .. ...pri mary cause . rscllr , '. r.. .-._t . _ .. :

'I don't really care an\ nlora -.-'. :>-.- : , _.. . .-,

18 May 2010).

Many of the students compared rltr-: :., - _ '' :, .

school experiences to primary school, clari--:-a .:_.,.was when they had enjoyed the nratherr;:-.:.One student made this comment: ,,That's prettrdifficult because my teacher now, he expiains it in a

good way, same as my teacher back then. She doesthe same but in more of a fun way" (Dean, interview,17 May 2O7O). When reflecting on the changes, itappeared the outstanding feature that the studentsmeasured their views upon was the teacher. Duringthis discussion comparisons were made betweenMrs L, their 'best' primary mathematics teacher, andtheir current teachers. The students admitted thattheir teachers had similar attributes, but the exceptionwas that Mrs L made lessons 'fun'. When askedwhether mathematics was still fun, a studentanswered: "Not really, I don't think so. Like whenwe're going to go from break to maths I don,t reallywant to do it that much" (Miley, interview, 17 May2010).

On a more positive note, some of the studentshad begun to feel optimistic about mathematics.Reasons for this appear to vary, as some students stilltalked about the value of mathematics in terns t:future employment opportunities while others i::.:mentioned how they had begun to understand :_ :.of the content being taught and claimed r:-.:...-matics was more 'fun' when you under::_ :, '

appeared to be a direct result of t1-re ch::t.=, ,. -

mented by the school, whlch had a ;-.=- . ...-the pedagogical practices of the te.-.:-..:,

d

:.

)a

tr

a

l

CATHERINE ATTARD

Findings from the study in relation to thepedagogical practices that engage students are

summarised in the FEM as shown in Figure 3. It can

be argued that the combination of practices suggested

in the FEM all contribute to cognitive, affective and

operative engagement with mathematics leading to

students enioying the study of mathematics, valuingtheir learning and seeing the relevance of mathe-

matics now and in the future, and seeing connec-

tions between school mathematics and the mathe-

matics used outside the classroom.

{*cxe&xs*&13

The participants in this study experienced a broad

range of pedagogies that represented the spectrum

of teaching approaches that support students inconstructing their own learning in primary school,

to a more 'traditional' style of learning in secondary

school. \,Vhile some of the students' experiences

ma,v have disadvantaged them in terms of theirengagement ivith mathematics, their range ofexperiences and perceptions of the differentpedagogies provided rich insights into the ways inwhich pedagogy influences engagement during the

middle years.

Although the study informing the FEM islimited in that it was a single case study, there is a lotto be learned from this group of students that can

be applied to a wider audience. The wide range ofpedagogies experienced by the participants and the

opportunity to gather data over an extended period

of time has provided a deeper understanding of

engagement and the necessary elements required

for positive and sustained engagement to occur.

This understanding may apply to students withinother school contexts and in other subiect areas.

The study also provided insight into current percep-

tions and needs of learners in the 21st century;

insights that would be useful in informing teacht:practices within mathematics and other learninlareas.

"l don't like it, I don't love it, but I do itand I don't mind."

In the opening of this article a secondary studer:.:

described how his attitude to mathematics hacchanged during the transition from primary t:secondary school. Although the above quote implie:complicity and a sense of resignation in relation t.studying mathematics, the purpose of the FEM is tc

encourage and support a love of learning mathe-

matics which is much more than an'I don't mincattitude. It is not suggested that teachers strive tc

achieve every aspect of the framework in everr

mathematics lesson. Rather it is about the devel-

opment of a classroom philosophy and approach.

However, the framework may serve as a useful

reminder and a starting point from which to plan

mathematics teaching and learning experiences

that represent student voice and promote affective,

operative and cognitive engagement. The FE\lshould also be considered as a work-in-progress. As

more research across wider contexts is conducted

and further understandings of engagement emerge,

the FEM will continue to evolve and develop as a toolfor mathematics educators.

The FEM highlights that it is not simply thepedagogical repertoires or the resources that teachers

use that influence student engagement, it is the

deeper level of pedagogical relationships that develop

between students and teachers that are a necessary

foundation for engagement to occur. Within this

deeper pedagogical level is the real hope that students

might come to a feeling that mathematics is an

exciting, relevant and engaging academic pursuit.

More students might then say, "I like it, I love it and

I do it."

Figure 3. Engaging pedagogical repertoires

ln an engaging mathematics classroom, engaging pedagogical repertoires mean:

there is substantive conversation about mathematical concepts and their applications to life

tasks are positive, provide opportunity for all students to achieve a level of success and are challenging for all

students are provided an element of choice

technology is embedded and used to enhance mathematical understanding through a student-centred

approach to learning---e relevance of the mathematics curriculum is explicitly linked to students' lives outside the classroom and

:-Cc',,.'ers students with the capacity to transform and reform their lives

-,-^=-alics lessons regularly include a variety of tasks that cater to the diverse needs of learners

: l3ror,r'n, M., Rhodes, V., Wiliam, D & Johnson' D'

- September). Effectitte teochers of numeracy in prirnary

'.:: Teochers' belicfs, practices and pupils' learning' Paper

::rteLl at the British Educational Research Association

-:ri Conference, University of York, UK' Retrieved

:- http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/,,r.l85.htm

1010). Students' experiences of mathematics during

.:rnsition from prlmary to secondary school in L'

'- ,n' B. Kissane & C. Hurst (Eds1, Shaping the future of

:.itltttics etlucdtiort (Proceedings of the 33rd Annual

:r.nce of the Mathematics Education Research Group

.:tralasia) (pp. 53-60). Fremantle, WA: MERGA'

. 2011a). hrftuences on student eflga:{emctlt during tlrc

..., r'eirts of schooling. Doctoral thesis, Unlversity of

,..rn Sydney, SydneY.

2011b). "My favourite sublect is maths' For some

. r no-one rea11y agrees with me": Student perspectives

:-.rthematics teaching and learnlng in the upper

' ..:r- classroom . Mathematics Erlttctttion Rcsearch [ournol '

.t63-377.

ir.r press). "If I had to plck any subiect' it wouldn't

::-.'.tl-ts": Foundations for engagement with mathe-

:.-: during the middle yeas' Mathematics Educcttion

...'.lt lournal..,:- .\ssociation of Mathematics Teachers' (2006)'

.'..,rls ttf excellence in teacLin; mathematics in AustraLian

.. Adelaide, SA: Author.-. \ssociation of Mathematics Teachers (2OO9)' School

.lilLttics for the 27st cenhffy: Some key irtfluences'

.:.1e. SA: Author.

1,110). The middle years learner' In D' Pendergast &

, ..:-: tEds), Teachitrg miLltlle years: Rctttinking curriculuttt'

. -a\ Llnd ossessmeilt (2nd ed', pp' a8-6a)' Crows Nest'

\ller-r & Unwin. ber).' lol\'son, M. & Mclnerney, D'M' (2005' Novem

: .'cl1\'een tnotivatioildl 3oals, academic self-cttncept and

, '.i: tclilevement: Whcrt is the cdusctl ttrdering? Paper

,:-,ccl at the Australian Association of Educational

. , -r'r, Svdney. Retrieved from http://ww'w'aare'edu'au/. -:irlications/2005/barO53 73'pdf

I ,00). Mathematics from another world: Traditional

:-.,.nities and the alienation of learners' lournal of

' ."...ttical Behavior, 1B(4),379-397 '

: tO9). The elephant in the classroont: Helping children

..,'..i ktve maths. London: Souvenir Press Ltd'

-' :- \'. t2OO6). Rethinking the nricldle years: Early adoles-

,,tnolirrs and digital culture' Crows Nest' Sydney:

-.r Unrvln'lL)03, Decemb et). Challengiry and engaging students

-., ithile mdthematics in the middle years' Paper

'-.d at the Mathematics Association of Victoria

... Conference: Making Mathematicians' Melbourne'

I 1ri09). Mathematics teachlng and learning: Where

.. -':irt;; Matters, .14(1), 3-8'

.. -r Halr'erson, R. (2009)' Rethinkirtg education in the

- .,-ltnology: The rligital rcvolution and schooling' in

. \erv York: Teachers College Press'

Comlnonu'ealtl] ot \u>:::.-'' -t.ePL)t'l. t lnbcrrr' \( l: h":' ' '

Council of Australian (rLr\ <rI-:ll--;l- ':

Corbin, J. & Strauss, A. 12008r' B'i':'' - . . '

TechniErcs ttntl procedu'es t'br '1't'i 'r':' '-

Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications' inc'

Creswell, J.W. (20o7). Qlolitatit' itt'lLtitt ';':; ' "'(2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Pubhcai'::''

Douglas Willms, J., Friesen, S. & Mllton, P (2009 ' lt ;: '

do irt schctol toclay?'loronto, ON: Canadian L:---'Association.

Downer, J.T., Rimm-Kaufman, S'E' & Pianta' R'C l2( )' - 'do classroom conditions and children's risk fo- ':'problems contribute to children's behavioral en$a$i:l-':: :

in learning? Schttol Psycholog;v Review' 36(3)' 413-13l'

Fair Go Team NSW Department of Education and Trainir':

(2006). School is for me: Patltways to student etlgogetTl'1"

Sydney: NSW Department of Education and Training'

Fredricks, J.A., Blumenfeid, P'C' & Paris, A'H' (2004) Schoc'

engagement: Potential of the concept' state of the

evidence. Rettiew of Educationsl Rcsearch' 7 4(7')' 59-1 1 0'

Hattie,.l. & f imperley, H. (2007)' The power of feedback Ret'/ett

rtf ELlucatictnal Research, 77(7), 87-772'

Hayes, D., Mills, M., Christie, P & Lingard' B (2006)' Teachers

anrl schooling making d difference' Sydney: A1ian & Unwin'

Hickey, D.T. (2003). Engaged participation versus marginal

nonparticipation: A stridently sociocultural approach to

achievement motlvation' The Elementary School lounnl'

103(4), 401,-429.

Lowrie,'t'. (2004, December)' Making mathematics meaningful'

realistic and personalised: Changing the direction of

relevance and appticability' In B' Tadich' S' Tobias' C'

Brew, B. Beatty & P' Sullivan (Eds)' Towards excellencc itr

mathematics (l']roceedings of the Mathematical Association

of Victoria Annual Conference 2004)' Brunswick' VIC-:

Mathematical Association of Victoria'

Martln, A.J. (2008). Motivation ancl engagement scctle: High school

(MES-HS) test user manttal' Sydney: Lifelong Achievement

GrouP.

Martin, AJ., Marsh, H.W., Mclnerney, D M' & Green' l' (2009

March). Young people's interpersonal relationships antl

academic and nonacademic outcomes: Scoping the

relativesalienceofteachers,parents'same-sexp€€rS'itl1copposite-sex peers' Teachers College Record' Retrieved fror

http://wrw.tcrecord'org/content'asp?contentid=1 5 5 9 l

McGee, C., Ward, R., Gibbons, J' & Harlow' A' (2003)' Irirrr'::: '

tct secontlary school: A literafutre re?ie1'v' Ne\\- Zea''':':'

Ministry of Education'

Merriam, S.B. (2009). Qlalitative research: A grtitle fo '1'r:'' '

inrplementotion San Francisco: John Wiler'fi So1" :'

Munns, G. & Martin, AJ' (2005) lt's all ubout \t'E: .1 ": ' '

and engagement framework' Paper prL'sLrl .- r-

Australian Assoclation for Academic Re''---

au/ciata/publication:/2005/m u rrUi+r rr'' : j

Nardi, E. & Stewarcl, S' (2003) ls uathe::--'': :

profile of quiet di\alfection ilt t'l'classroom. British Edttcttti(rri'z: : ' '' '

--

345-367.

I-*--

=

==

====

=

::;

:i

]

qATHEBINE ATTARD

NSW Department of Education and Training. (ZOO3). eualityteaching in NSW public schools. Sydney: professional

Support and Curriculum Directorate.Ryan, A.M. (2000). Peer groups as a context for the sociali-

sation of adolescents' motivation, engagement andachievement in school. Educational psychologist, 2S(Z),101-1 1 1.

Stake, R. (2005). Quatitative case studies. In N.K. Denzin & y.S.

Lincoln (Eds), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research(3rd ed., pp. 4a3-466). Thousand Oaks, CA: SagePublications.

Stevens, L.P., Hunter, L., Pendergast, D., Carrington, V., Bahr,N., Kapltzke, C. & Mitchell , l. (2007). Reconceprualizingthe possible narratives of adolescence. The AustralianEducational Researclter, 34(2), 107 -lZB.

Thomas, M. & Chinnappan, M. (2008). Teaching and learningwith technology: Realising the potential. In H. Forgasz, A.Barkatsas, A. Bishop, B. Clarke, S. Keast, W. Seah, p.

Sullivan & S. Wiliis (Eds), Research in mathematics educationin Australasia 2004-2007: New directions in mathematics andscience education (pp. 165-794). Rotterdam: Sense

Publishers.