Hopes, Fears and Frustrated Dreams: Infertility in early modern England

Transcript of Hopes, Fears and Frustrated Dreams: Infertility in early modern England

2 | Wellcome HISTORY

Beautifully hideousPioneering plastic surgery in World War I

Jennifer Summers and Max Browne

The sight of “men burned and maimed to the condition of animals” returning from

the trenches motivated a visionary volunteer surgeon, Harold Delf Gillies (1882–1960), to transform the field of maxillofacial reconstructive surgery. The techniques Gillies employed, such as the ‘tubed pedicle’, are the first pioneering examples of modern plastic surgery from World War I.

Facial and head injuries were common in the trenches. Around 15 per cent of those who survived and were evacuated back to Britain for treatment had some form of facial trauma. The typical Tommies’ training did not prepare them, either physically or psychologically, for the horrific conditions of the trenches or the aftermath. An American surgeon in France, Dr Fred Albee, noted that the soldiers “seemed to think they could pop their heads up over a trench and move quickly enough to dodge the hail of bullets”.

The complex nature of these wartime facial injuries, combined with the staggering number of victims, prompted Gillies to develop new techniques, which still underpin many principles of modern plastic surgery today. He was a New Zealander stationed in Britain who felt an “overwhelming urge to change something ugly and useless into some other thing more beautiful and more functional”. From 1916 Gillies worked with a multidisciplinary team of surgeons, nurses and dentists at the Cambridge Military Hospital based in Aldershot, and later at Queen Mary Hospital in Sidcup, Kent.

Responding to the avalanche of victims, Gillies built upon historic skin-grafting techniques used in Germany, France, India and Russia, to develop a radical new surgical procedure, known as the tubular pedicle. This allowed the first cases of modern facial reconstruction to take place.

The construction of the facial pedicles involved taking tissue from other parts of the body and fashioning a ‘tube’ of skin containing blood vessels to the damaged tissue. In this way infection was kept to a minimum, as the pedicle was essentially closed tissue and provided increased blood supply to the face. This was of critical importance during this pre-antibiotic era.

Harold Delf Gillies felt an “overwhelming urge to change something ugly and useless into some other thing more beautiful and more functional”

Gillies, himself an amateur artist, described plastic surgery as “a strange new art” and recognised the need to meticulously document this rapidly evolving and pioneering surgical field. He sought the help of an accomplished artist and by good fortune found the perfect candidate. Professor Henry Tonks (1862–1937) had a unique combination of expertise: coming from a successful surgical career as a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, his stronger leaning towards art had driven him to become Britain’s leading drawing master at the Slade School of Art. Having also volunteered

for War Service, Tonks was only too happy to produce before-and-after surgical illustrations for Gillies (even though he had previously declared Gillies was “not any use as a doctor”).

With Tonks’s extensive knowledge of human anatomy and devotion to the draughtsmanship of the Renaissance masters, his rigorous teaching of life drawing at the Slade became a powerful influence on the work of decades of British artists in the first half of the 20th century. In 1916, as a temporarily commissioned Lieutenant in the British Army Medical Corps, Tonks joined Gillies to become an artistic historian of facial injuries of the war. He once remarked that “faced with crushed faces and torn flesh, what is the surgeon artist to draw?”

Tonks’s contribution over the following year resulted in the now famous series of 69 before-and-after pastel drawings that helped Gillies to record the results of his surgical techniques (see pages 4 and 5).

At this time medical photography was only available in black and white, and Lieutenant Colonel Parkes noted that this specific limitation did “not depict the natural colour of the damaged tissues”. For a practical coloured medium Tonks chose pastel, a traditional choice of portraitists for centuries. As well as meeting the medical and military requirements to record Gillies’s work, the pastels enabled Tonks to capture a more artistic sense of plastic surgery. Renowned art critic Brian Sewell recently commented that Tonks “could not help, as an artist, making them beautifully hideous”.

Winter 2014 | 3

Stages in the repair of a man’s face using a Gillies pedicle tube. From Gillies’s Plastic Surgery of the Face, 1920. archive.org

4 | Wellcome HISTORY

A notable example, detailed in the Gillies Archives at the Royal College of Surgeons, is Private Walter Ashworth, West Yorkshire Regiment (no. 1071), from Bradford, who was wounded on the first day of the Battle of the Somme in 1916. Tonks’s first drawing (left) shows Ashworth waiting for a facial washout with sterile Milton solution. A rare surgical diagram (centre) shows the process to close the wound by suturing flaps of skin and tissue from the cheek and jaw. After three operations and discharge a year later, Gillies commented that it had been necessary to sacrifice some of the

length of the lips to close the wound and that this had left his patient with a “whimsical, one-sided expression that, however, was not entirely unpleasant” (right). Unfortunately, on Ashworth’s return home this proved too much for his former employer and his fiancée to accept. However, he married one of her more supportive friends, and they successfully took up job opportunities offered by a move to Australia. Four decades later patient and surgeon met again, but the latter’s offer of further improvement was turned down – perhaps as a result of Ashworth’s having already

undergone so much surgery, including shrapnel removal from his back, which had continued into the 1950s.

It was sometimes observed that the plastic-surgery patients benefited from the attention given to them by an artist, rather than a more perfunctory depiction by camera. However, Tonks was more concerned about another side-issue: that the pastels were “rather dreadful subjects for the public view”. While other works by the artist, such as ‘Saline Infusion’ (1915) and ‘An Advanced Dressing Station in France’ (1918), also depict intense wartime imagery, Tonks refused to allow the

Left to right: ‘Pvt. Ashworth before Surgery’ (1916), ‘Surgical Diagram for Pvt. Ashworth’ (1916) and ‘Pvt. Ashworth before discharge’ (1917), by Henry Tonks. Reproduced by kind permission of the Royal College of Surgeons, London

Winter 2014 | 5

pastels to be displayed at the Imperial War Museum. He insisted that “they would be viewed by a bloodthirsty public seeking vicarious gratification”, so for most of the 20th century they remained hidden away, before being acquired by the Royal College of Surgeons in London. They have now become one of the most requested loan items in the College’s collection.

The extraordinary legacy created at Sidcup, enhancing and promoting the new medical field of plastic surgery, has also ensured that Gillies is often referred to as the “father of modern plastic surgery”. A recent exhibition and

publication of the pastels he produced has brought their medical story to wide public and critical acclaim. Indeed the recent National Portrait Gallery exhibition The Great War in Portraits has provided continuing insights into the personalities and physical sufferings of the injured men. It is an historical irony that, despite Tonks’s personal misgivings about the public display of his pastels, they are now valued by many as a potent visual expression of an important and popular universal theme in this centenary year of the start of World War I: lest we forget.

Dr Jennifer A Summers was born in Wellington, New Zealand. She holds degrees in Psychology, Statistics and Public Health, and has a PhD in Historical Epidemiology from Otago University, specialising in the 1918–19 influenza pandemic in military populations of World War I. She is currently a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow in Medical Statistics at King’s College London (E [email protected]).

Max Browne (BA Hons) is an independent art historian and documentary cameraman/photographer based in London. He specialises in 19th-century Romantic art (E [email protected]).

6 | Wellcome HISTORY

The Editor’s EyeFocusing on the stories of the medical humanities

Elizabeth T Hurren

The stonemason discovered the vermilion carving when cleaning the back wall of my

cottage for repointing this summer: Sharp frost May 29th 1914 Still, in a building dated 1654 it

was a surprise to find a weather report carved just before the eve of World War I. Lime plaster has to be frost-free when repairing stonework, so the young mason must have been anxious about the inclement ground frost as war threatened on the village horizon in the summer 1914. In a hurry perhaps to get the delayed job done, soon he – and all the young men in Rutland, the smallest county in England – would be packing up for France. It was touching to feel the carving with my fingers, to reconnect to village tradesmen who became unknown soldiers in 1914 on the Western Front.

This 2014 winter issue of Wellcome History features those that should never be forgotten in this World War I centenary year. It touches on themes often associated with wartime medicine: plastic surgery, mental ill-health, suicidal tendencies, force-feeding of conscious objectors, and those dislocated across the British Empire.

This is also the final issue of Wellcome History. In future, the Wellcome Trust will be sharing research in the medical humanities online, to make faster connections across the world in a digital age. Would Henry Wellcome like the e-revamp? Well, he always had a pioneering spirit and was a supreme self-publicist, so it seems very likely that, as a business entrepreneur with a passion for medical history, Henry would have been at the forefront of using the web to engaging the public wherever he could. I hope therefore that contributors will continue to uphold his pioneering spirit by sending in new ideas and ways of thinking to meet whatever human challenges the future of medicine and science holds.

In 2014 the Trust launched Mosaic (mosaicscience.com), publishing weekly stories on any aspect of biology,

medicine, public health, history or ethics that in some way touches on human or animal health, or the human condition. Articles with a historical aspect so far have included Hungary’s struggle with polio in the Cold War, Alan Turing’s contribution to developmental biology, and the many decades of efforts to understand blood groups, Alzheimer’s disease and the dangers of asbestos. The editorial team is always looking for new contributions; you can find out how to contribute at blog.mosaicscience.com/pitching-to-mosaic/.

Meanwhile, the Wellcome Trust blog (blog.wellcome.ac.uk) features news about work the Trust supports, in the medical humanities and public engagement as well

as in science, and the Wellcome Library blog (blog.wellcomelibrary.org) showcases historical research activities and resources.

As the closing editor of this final printed issue, I would like to thank everyone who has contacted me from around the world. It has been a privilege to engage with your cutting-edge research, and I shall continue to follow debates and discussions online as our future innovations give voice to the medical humanities of Henry Wellcome’s extraordinary legacy.

My kindest regards, Elizabeth Hurren

Dr Elizabeth Hurren is Reader in Medical Humanities, University of Leicester (E [email protected]).

Royal Army Medical Corps stretcher-bearers lifting a wounded man out of a trench. By Gilbert Rogers. Wellcome Images

Winter 2014 | 7

Norfolk in World War ICelebrating the workhouse war effort

Stephen Pope

Civil servants responsible for the UK’s public health provision at the start of World War I

coordinated a huge logistical task. They offered to work with the Ministry of Defence to find accommodation to house and train all the new army recruits required to fight a major land war against Germany in Europe. Their inspired solution was to ask the Local Government Board in London to make available any spare workhouse capacity that it had in towns, cities and rural areas like Norfolk. The granting of Old Age Pensions to those over 70 years of age in 1908 meant that by 1914 many of the elderly could afford to live at home. Fewer people in the workhouse created spare capacity that could be used for the war effort. This ensured that medical and healthcare provision for recruits could be managed in practical terms, and it secured the humane treatment of prisoners of war too.

From the start of the war the Local Government Board supported the military by sending out circulars urging workhouse guardians to make arrangements to admit troops into public buildings. Some 20,000 troops were in training camps in Norfolk by the end of 1914, ensuring that local guardians felt obligated to assist. At first, most were accommodated in tents. As winter approached, wooden huts were being built, but the military realised that workhouses could provide weather-proof accommodation for the troops.

In the early days of the war effort, army units paid workhouses directly for requisitioned accommodation. Utilities expenses for fresh water supplies, and coal or oil heating and cooking costs, were refunded promptly to encourage more guardians to cooperate. St Faith’s Union to the north of Norwich, for example, was where the 2nd Service Norfolk Battery Royal Field Artillery were based. During training they paid £13 a quarter direct to the Matron of the local workhouse. Then on 1 July 1915 a formal financial compensation scheme was devised by civil servants. A Local Government

Board official circular was sent out detailing a schedule for all guardians to be compensated by the Army Council for the ongoing use of workhouses’ facilities, with any expenses paid via a local Quartering Committee.

As well as billeting troops in many Norfolk workhouses, basic public health provision was also covered for recruits in the local area, including bathing and washing facilities, and the laundry disinfection of clothing. Yarmouth in February 1916 was asked to provide bathing for an extra 1,500 troops per week. King’s Lynn in August 1915 agreed to house 250 men from the Royal Berkshire Yeomanry and allowed a further 400 men to use the dining hall to get a nutritious meal.

Gradually, with the approach of winter in 1915, the military once again requested that local workhouses house even more troops. At Aylsham, for example, the City of London

Yeomanry requested the use of another wing and the stables. The workhouse guardians were only able to offer the use of a Children’s Home that had been purchased in December 1914. They needed however to first rehouse the children before handing it over to the military. The children were sent to a nearby workhouse and then by February they were moved again to West Beckham and Smallburgh Workhouses, smaller facilities which had spare capacity along the Norfolk coast.

The progress of the war effort often depended on boards of guardians deciding to vacate workhouse buildings altogether. In Norfolk the Docking Workhouse was taken over by the War Office in November 1916, although the guardians requested the continual use of the board room and the stables. This necessitated the transfer of inmates to the King’s Lynn

Postcard photograph of Aylsham Workhouse, Norfolk, in World War I. Author’s personal collection

8 | Wellcome HISTORY

workhouse, a decision that was not without incident. The workhouse Medical Officer at King’s Lynn refused to have anything to do with the Docking inmates. Unfortunately one of the transferred inmates, a baby of two months, had recently been vaccinated and subsequently died from an infected arm. The Medical Officer was censured for not seeing the baby on its arrival and was subsequently forced to resign, in May 1917.

Like many of the workhouses in the county, Smallburgh had been quick in August 1914 to offer accommodation to the War Office. It had the capacity to house up to 800 pauper inmates, although it rarely held more than 100 at any one time, and so had space for the army recruits. The local Tunstead and District Volunteer Training Corps in December 1914 used the stable yard and erected a miniature rifle range with removable targets and butts. With the arrival of winter in 1916, the military then asked to use the workhouse building to accommodate troops. The guardians were still hoping to continue to use part of the building, but by December they had finally agreed to give up the whole workhouse to the military and transferred their inmates to Heckingham.

Other workhouses, such as Horsham St Faith and Lingwood, were also used to accommodate troops but were never fully taken over by the military. At Lingwood the Local Defence Corps asked to use the large dining room for drill, but this was refused as it was thought it would disturb the inmates in the sick wards. Lingwood, like other workhouses in the county, became home to inmates from workhouses that had been taken over by the military, receiving arrivals from Rollesby in January 1917.

Gradually these changes also started to impinge on hospital provision for the vulnerable. In March 1915 all Norfolk workhouses received a letter from the County Asylum at Thorpe outside Norwich. It stated that Thorpe would no longer be able to receive mentally ill patients because it was being taken over as a military hospital. The asylum inmates were reassessed and redistributed to other county asylums in Suffolk, Essex, Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire. Many of them were never to return. All new patients were now to be sent

to Hellesdon Asylum in Norwich. A decision was also taken to try to utilise any spare capacity in newly built infirmaries in the county. Wayland Poor Law Infirmary, for instance, had been constructed near Attleborough in 1912. By November 1917 it had been redesignated as a military hospital, and its sick poor were transferred to Thetford Workhouse to free up military beds. Meanwhile, parts of the workhouse at Swainsthorpe were used by the Red Cross Society as a hospital for wounded soldiers from October 1915 to February 1919.

Lacking a dentist’s chair, Dr Duigan relied on a burly German prisoner to hold the patient’s head while he took out the decayed tooth

As the military started to require more and more manpower, and with the introduction of conscription in 1916, so members of staff in workhouses became liable for call-up. Few workhouses though had men of military age; often it was only the Master, Porter and Medical Officers who found themselves being conscripted. Medical Officers in particular were required by the military. By March 1916, the Local Government Board formally asked all workhouse guardians to release Medical Officers age 45 and under for military service. While smaller workhouses, for instance Swaffham, could afford to let go of their resident medical men, in most cases the guardians maintained that they could not spare theirs. At Aylsham by 1917 the guardians found themselves short of experienced staff. The Porter had been called up in May 1916, and although the Master applied for exemption, by April 1917 the military had appealed and he was also called up too. The workhouse was left to be run by the Matron and her sister.

Guardians often appeared before local tribunals on behalf of their staff to gain exemption from military service. The Assistant Clerk at Lingwood, McRoberts, was granted such an exemption in May 1916. It was however only granted for a short period; by September it was withdrawn and he enlisted in October. His place was taken by Miss Florence Kendall, but at a much reduced salary: £5 instead of £40. In contrast, the guardians

often offered to make up any loss of a Master’s salary when he was serving on a reduced pay grade as a solider or officer. Yet one essential role in workhouses was increasingly difficult to fill, that of the general nursing staff. Many nurses left to work in military hospitals either through a sense of patriotism or because they were better paid there. Thetford Workhouse had a great deal of difficulty retaining nursing staff. In January 1916 there was one Head Nurse and just two assistant nurses in service to tend its 300 beds: on average they cared for 144 inmates per night throughout 1916.

One aspect of the workhouse war effort that merits closer attention is the use of the buildings to house German Prisoners of War (POWs) in Norfolk. Horsham St Faith workhouse housed 50 POWs in a disused building on site in 1919 while they were cleaning out the dam and dykes at a local mill. At Kenninghall, POWs were involved in getting in the 1918 harvest, working in 62 parties throughout the local area. The prisoners worked a 60-hour week and received pay at a rate of 5d per hour for skilled agricultural labour and 4d per hour for unskilled tasks. Two of the POWs are known to have died during their period at Kenninghall: Otto Kohnert on 9 January 1918 and Ludwig Wingert on 15 January 1918. Both were initially buried in the local churchyard before being reinterred in the German War Cemetery at Cannock Chase in January 1963.

POWs arrived at Gressenhall Workhouse in April 1918, and were employed on local farms and clearing out the river Wensum. On arrival they were paraded in the courtyard and inspected by the Medical Officer, Dr John Duigan. He was appointed as a civilian medical practitioner by the military authorities, meaning that he was responsible for the healthcare and welfare of the POWs. Unable to speak German, he relied on a prisoner from Cologne who spoke at least six languages. On several occasions Duigan had to act as a dentist, extracting teeth. Lacking a dentist’s chair, he relied on a burly German prisoner to hold the patient’s head while he took out the decayed tooth.

During the POWs’ time at Gressenhall Workhouse an epidemic of influenza broke out in the camp, with four cases also developing pneumonia.

Winter 2014 | 9

The Army asked Duigan to send them to a hospital in Norwich or Cambridge, but he refused. The POWs were officially under Army control, yet had to abide by workhouse rules. Duigan decided he had the medical authority to keep them at Gressenhall. He was later informed that Gressenhall was the only military base not to have deaths from the epidemic. Duigan credited this to his refusal to transport the pneumonia cases on a risky journey and the good nursing the sick men received from their fellow prisoners. This style of care, however, often contravened workhouse rules. Physical contact between any remaining Poor Law inmates and the POWs should have been minimal, but a female inmate, Mabel Bowman, was found in the camp fraternising with one of the German prisoners. She was not punished because the guardians blamed any laxity on the military guards in charge of the prisoners.

Intriguingly, at Gressenhall Farm and Workhouse Museum, a parcel lid for German prisoner number 18339 has survived today in the museum collection. It was sent by the prisoner’s family and never left the workhouse.

As a result of military occupation a number of Norfolk workhouses never reopened after the war ended, among them Docking, Swaffham and Smallburgh (which had been damaged by fire and been left in a very dirty condition in 1918). The majority of Norfolk workhouses had provided a valuable service to the war effort in practical ways that merit a celebration of their medical successes 100 years on.

Stephen Pope spent 27 years in the Royal Air Force as a radar technician. After leaving, he worked front of house at the Gressenhall Farm and Workhouse Museum in Norfolk. On retiring, he became a volunteer researcher at the Museum and continues to research the history of the Poor Law in Norfolk. To find out more about the history of Gressenhall Workhouse, see museums.norfolk.gov.uk/visit_us/gressenhall_farm_and_workhouse/ or contact Megan Dennis, Curator of the Museum (E [email protected]). If you too have information about the workhouse war effort in World War I, do get in touch with Stephen (E [email protected]).

In Flanders fieldsCasualties of war at Essex Farm, near Ypres

Jonathan Swan

In early 1917, the British Army front line ran in a rough semi-circle about two to three miles around the

east of the town of Ypres in Belgium. On the night of 9 April the men of C Company of the 15th Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers were struggling to keep warm in their trenches to the north of the town. There had been sporadic artillery and machine-gun fire all day, and a gas alert or two, but nothing out of the ordinary. Then, at about 11.30pm, the Germans fired a salvo of rifle grenades at trench post 9, and five men were wounded. Their next destination, Essex Farm Advanced Dressing Station (ADS), was an important part of a medical evacuation chain that is today little appreciated.

During the early hours of 10 April, even as a counter-barrage was being called down, stretcher-bearers collected the casualties and took them back through the maze of trenches to an aid post about 800 yards away, near the battalion headquarters. From there they were taken to Essex Farm, another 1,500 yards away across the Yser canal. This is where they had their wounds initially dressed. It was the sort of place where so many injured men waited until they could be evacuated further back from the front line to safety and medical treatment. Essex Farm still stands today and is one of the most visited – but most poorly understood

– battle sites in Belgium. For many it is closely associated with John McCrae’s poem ‘In Flanders Fields’, the lines of which are on a bronze plate at the top of the path down to the bunker. Visitors peer into the gloom of the seven chambers inside the low ADS concrete structure, but it is hard to imagine the scenes of wounded soldiers and their medical experiences.

The origin of the name Essex Farm is obscure. McCrae was serving at an unnamed Canadian dressing station nearby when he wrote his poem, in early April 1915, but it is unlikely that he knew of Essex Farm. The name may derive from the 2nd Battalion of the Essex Regiment, who regularly passed through the area to get from their billets to the front line at Ypres in late May 1915. Aside from these associations, Essex Farm by August 1915 was a well-established ADS consisting of a series of dugouts in the canal bank. The concrete structure seen today dates from November 1916. It was last used by the British in December 1917, after which it was handed over to the French and subsequently the Belgians.

The ADS was at the front line of military medical care in World War I. Before it was the battlefield and behind it the Casualty Clearing Stations (base hospitals providing comprehensive medical and surgical treatment for the sick and wounded).

An advance dressing station, WWI. By Ugo Matania. Wellcome Images

10 | Wellcome HISTORY

The ADS was staffed by men of the Field Ambulances of the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC; the modern equivalent is the Medical Regiment). The Field Ambulance comprised ten medical officers and 220 RAMC men, with 50 or so Army Service Corps personnel attached as drivers, cooks and handymen. It was divided into three sections – A, B and C – and each of these was further split into a bearer subdivision, responsible for casualty collection, and a smaller tent subdivision, for care and treatment. On deployment, sections B and C each formed an ADS; section A was generally set up as the Main Dressing Station and headquarters. The purpose of the ADS was limited: it was a transient casualty management station. It was not tasked, nor equipped, for anything other than dressing and splinting. Recent research confirms that it was most definitely not a hospital, even in the loosest sense of the term.

In April 1917 Essex Farm was staffed by B and C sections of the 130th (St John) Field Ambulance RAMC, with a bearer section working forward at La Belle Alliance Farm. Their Main Dressing Station was at Gwalia Farm, about four miles away to the west. The wounded Fusiliers of our opening story were evacuated from the front line by their regimental stretcher-bearers. These were infantrymen but had been assigned to this duty and were non-combatants. They were first-aid trained and their role was simply to apply dressings and to extract casualties. Yet their physical presence in the trenches provided a powerful psychological boost to the injured and able-bodied alike.

When the five Fusiliers were injured, the stretcher-bearers carried them to the Regimental Aid Post at La Belle Alliance Farm. Here they were seen by their battalion Medical Officer (MO). His role was limited too: arrest bleeding, apply dressings, relieve pain and splint fractured limbs. Bearers from the field ambulance took over the casualties and they were loaded onto a trolley cart. Carrying up to four stretcher cases, each cart was hand-pushed along wooden rails all the way to Essex Farm. Lightly injured soldiers – the walking wounded – made their own way back.

The moribund would be discreetly moved to a warm hut or dugout; if still alive after the other casualties had been sent on, a place would be found in the next ambulance car

Today there are seven rooms remaining in the Essex Farm complex – others were destroyed by shelling. There were also a number of dugouts, huts and tents, which no longer remain. A sketch (below left) was drawn by a member of 69th Field Ambulance in late 1917, which we can use to form a picture of what happened there when the Fusiliers were brought in as casualties. As the trolley carts rumbled up across the bridge to Essex Farm, the duty MO would have been waiting in room 1, described as the Officers’ Mess. Coming out from behind a heavy anti-gas curtain over the door, he would assess each casualty in the light of an oxyacetylene lamp. The lightly injured or sick would be sent to room 2, in which the MO would check them over and send them down to the cookhouse for a cup of hot sweet tea. Any soldier assessed as likely to recover within two to four days was retained by the ambulance and so, depending on the tactical situation, he would remain at Essex Farm or be taken back to the Main Dressing Station at Gwalia Farm to recuperate. Meanwhile, stretcher cases were taken into room 3.

Shock as a medical problem was only beginning to be understood, but cold was seen as a major factor in casualty-recovery figures. For this reason, while soldiers waited to be seen, they were provided with cigarettes and hot water bottles, as well as hot drinks and dry blankets where available. An RAMC clerk would also take down their personal details and fill in the Field Medical Card for each injured man, a copy of which was pinned to the soldier’s uniform. They waited to go into room 5, which was described as a dressing room; the RAMC men were adept at quick and efficient splinting and bandaging. Surgery was not practised in the ADS, other than emergency amputations and the control of bleeding with ligatures.

In this pre-antibiotic era wounds were heavily contaminated but it was accepted that irrigation, excision and debridement was best managed at the Main Dressing Station and Casualty Clearing Station, further back from the front line. Prophylactic anti-tetanic serum was administered to all of the wounded and morphine was given for pain relief. A ‘T’ was written on a man’s forehead after the serum was administered, and an ‘M’ on his wrist if given morphine. It is important to appreciate that at the ADS the concept of medical triage related only to prioritising casualties for evacuation. Head, abdominal and chest cases were often kept at the ADS for a time to stabilise. The other casualties – walking and on stretcher – would go to room 7 and the huts Drawing of Essex Farm. RAMC Muniment Collection, Wellcome Library

Winter 2014 | 11

outside to await transport onwards. The moribund would be discreetly moved to a warm hut or dugout; if still alive after the other casualties had been sent on, then a place would be found in the next ambulance car.

During the night, cars of the 4th Motor Ambulance Convoy would have been collecting casualties for the onward journey to the 10th Casualty Clearing Station at Remy Sidings (Lijssenthoek). There full medical and surgical facilities were available, together with a railhead for evacuation to the base hospitals on the French coast and beyond. But, poignantly, for some the journey ended at Essex Farm. Of the five men wounded on 9 April 1917, two survived, but the other three – Privates Bowen, Morris and Williams – are buried in the adjacent Essex Farm Cemetery.

The limited historical study of medical war facilities like Essex Farm is understandable. The first priorities of the frontline medical services were evacuating and managing casualties. Treatment happened behind the lines for those that survived the trauma of shelling and trench warfare. The British Army relied on the deployment of field ambulances because these mobile units were ideal for changing battlefield conditions. Essex Farm is not a typical structure: an ADS was usually set up wherever a safe and convenient location could be found in cellars, dugouts or captured pillboxes. This explains why many have been overlooked in surviving military records, in contrast to the Casualty Clearing Stations and base hospitals. Essex Farm was never famous during the war: Ypres Prison, the Asylum and Menin Road were of much greater renown. But today Essex Farm survives as a stark reminder of an industrial scale of warfare in which so many men were broken and damaged, in Flanders fields.

Jonathan Swan is a military historian specialising in the frontline medical services of World War I, and he previously served in the RAMC. He welcomes enquiries from anyone researching the human experience of the medical evacuation chain, from the front line via the Advanced Dressing Stations to the Casualty Clearing Stations and field hospitals, on the Western Front (E [email protected]).

The near-death of the novelistVirginia Woolf’s Veronal overdose, 1913

Ian Franklin

Two men rushed out of a front door and hailed a taxi outside 38 Brunswick Square

in Bloomsbury, central London, on 9 September 1913. They were on a medical emergency. It was essential to collect and return with a stomach pump from St Bartholomew’s Hospital about half a mile away. Their patient, Virginia Woolf, was at death’s door. She was not yet the famous novelist, but this was her first serious suicide attempt and it required an urgent medical intervention.

Dr Geoffrey Keynes, house surgeon at St Bartholomew’s, accompanied Leonard Woolf, Virginia’s distraught husband. Virginia was a gifted

individual who had only started her writing career, completing but not yet publishing The Voyage Out. Already, though, she was disturbed by mood swings that sometimes felt overwhelming; on this particular night, she needed urgent professional help to prevent the risk of a fatal outcome. Had she not received it, the rest of her famous novels might never have been written. In later life, Keynes liked to think that he had saved her future masterpieces for posterity. Sadly, these mental ill-health episodes would continue, culminating in her death by suicide during World War II. Virginia’s medical case notes illuminate how well strong barbiturates were understood

Virginia Woolf, age 20. Wikimedia

12 | Wellcome HISTORY

on the eve of World War I, before the mental traumas of the trenches.

Virginia Woolf’s medical history reveals that she had been unwell for some months earlier in 1913. She had experienced episodes of hypomania in the past, and would do so again, but the problem in the summer and autumn of 1913 was the start of what today would be termed clinical depression. She had been referred to a neurology specialist called Sir George Savage, who worked with private asylum patients and had a reputation for rescuing difficult mental health cases. He had recommended peace and quiet, as well as physical rest and an eating treatment, and he gave her a new sleeping draught to help with her insomnia. This regimen had been taken very seriously by Leonard, whom Virginia had married the previous year, and they had been following Savage’s treatment plan assiduously. However, while they respected Savage, they were not convinced that his holistic prescription was working. So she came to London to seek a second medical opinion. On the recommendation of Roger Fry from the Bloomsbury Group she visited Dr Henry Head, an eminent neurologist and experimental scientist. Head was already a Fellow of the Royal Society, and would be knighted in 1927.

Leonard and Virginia saw Head on the afternoon of Tuesday 9 September, just hours before her first suicide attempt. Leonard gives some idea of the seriousness of her condition in his autobiography, Beginning Again, when he wrote that the day before: “Virginia was in the blackest despair and there was, I knew, danger that she might at any moment try to kill herself by jumping out of the train.” After the appointment with Head, Leonard went to see Savage to advise him that they were consulting Head. Meanwhile, Virginia returned home, where a friend – Katherine (‘Ka’) Cox – had agreed to keep an eye on her. At about 6.30pm Leonard received a telephone message informing him that Virginia had fallen into a deep sleep. She had taken an overdose of a new brand of sleeping drug called Veronal, manufactured from barbitone (first synthesised in 1902 by German chemists Emil Fischer and Joseph von Mering). Generally it was dispensed for insomnia induced by what was then called nervous excitability. The patient was given a capsule or sachet with water at

bedtime, and a therapeutic dose was 15 grains (just under 1 gram). Clearly, Cox’s eye had not been keen enough, for Virginia managed to ingest 100 grains of Veronal – a potentially fatal amount.

By the time that Leonard and Dr Geoffrey Keynes returned from St Bartholomew’s with a stomach pump borrowed from the emergency room, Head had also arrived with a nurse. The two medical men got on with the assembly and use of the apparatus. Keynes’s own account, in Gates of Memory, states that they worked through the night, though it is unclear from the family records how long the ‘pumping’ of her stomach went on for. At one point, it looked doubtful that Virginia would survive the night because her pulse was so weak. Hermione Lee’s biography of Virginia stresses that at around 1.30am she looked dangerously ill. By daybreak, however, she was

stronger and clearly out of danger, although she did not wake up fully until the following day, Thursday.

Although Leonard normally kept the drugs case locked, he inexplicably failed to do so on this occasion. Ka Cox did her best – she was not a trained nurse or doctor – but Virginia managed to elude her. Cox seemed a very popular member of this circle. Michael Holroyd in his life of Lytton Strachey quotes a letter from Strachey at the time of Virgina’s suicide attempt. “Poor Woolf!” he writes – meaning Leonard. “Nearly all the horror of it has been and still is on his shoulders. Ka gave great assistance at the worst crisis…” It seems Ka was not blamed by anyone for this incident.

One hundred years on from the drama of that night, we can ask: how effective was their intervention was in its historical context, and how have things changed in the intervening century?

Enema and stomach pump. Wellcome Library

Winter 2014 | 13

At the time there were a number of leading medical journals that considered Veronal to be an effective drug for mental health patients with persistent insomnia, but all warned that it should be taken in moderation. In March 1913, the British Medical Journal had published a leading editorial entitled ‘Veronal Poisoning’, which was read widely. It contained details of a suicide inquest at Hove in Sussex, which had attracted a lot of adverse publicity because the deceased had been given Veronal. Hugh Eric Trevanion had taken 150 grains 32 hours before he died, and so the jury had advised in their concluding verdict: “That Veronal, its derivatives and allied substances should forthwith be placed on the poisons schedule – That it be illegal to supply any hypnotic drug without the prescription of a medical man.” The California State Medical Journal described that there could be after ingestion a downhill course to death. If the patient looked in danger then a gastric lavage (stomach pump) was essential, followed by the introduction of black coffee and one egg into the stomach. Only two weeks after the BMJ article, Goldney Chitty wrote in the Lancet about a recovery following 125 grains of Veronal poisoning, with gastric lavage being undertaken over the 12 hours after ingestion, with coffee and egg being left in the stomach. Poisoning with Veronal was evidently highly topical in 1913, and this type of commentary suggests that Doctors Keynes and Head, and likely most general practitioners, would have been familiar with the basic emergency procedure given to Virginia.

In Virginia’s case, she was treated in a professional manner by the doctors. The stomach pump procedure would have been necessary but very unpleasant to administer and experience even in a drowsy state. After gastric lavage a pint of strong coffee and some castor oil were left as an aperient in the stomach. Stimulants such as caffeine and strychnine were also sometimes part of the management of Veronal poisoning, as was digitalin: although no mention of the use of these is made in Virginia’s case.

In 1966, Henry Matthew and colleagues from the Poison Centre and University Department of Clinical Chemistry at the Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh, writing in the BMJ, argued

that lavage could be worthwhile in barbiturate poisoning, but only if performed quickly. They found that lavage within four hours of ingestion removed over 200 mg of barbiturate from the stomach a third of the time, but beyond that point such efficacy was extremely rare. Barbiturates were widely used in the first half of the 20th century as a treatment for epilepsy and as hypnotics – essentially sleeping tablets for insomnia. Phenobarbitone was the most widely prescribed until all barbiturates were phased out in the UK during the 1960s because people were becoming habituated to them – and also because of their use in suicide attempts. Barbiturates continue to be used widely in developing countries.

Gastric lavage was essential, followed by introduction of black coffee and one egg into the stomach

The current management of a barbiturate overdose, most commonly with phenobarbitone, does not include gastric lavage. It was however a regular part of the management of self-poisoning into the 1980s, as ubiquitous and often useless as the ‘psychs to see’ referral – medical jargon for a request for a psychiatrist’s opinion. The stomach pump seemed to be a disincentive to repeat the overdose habit, rather than something that was felt to be life-saving. In 1996, three doctors in the Accident & Emergency Department of Hull Royal Infirmary (Greaves, Goodacre and Sprout) reported the results of a survey of 190 other doctors in A&E in the UK. Their results suggested that “‘punitive’ washouts may still be taking place despite a lack of clinical indication”. A systematic review from 2011 by two doctors at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital in Australia (Roberts and Buckley) suggested that there was little in the way of proven therapy, although supportive care and multiple doses of activated charcoal (MDAC) seem usual. The use of MDAC is recommended only after securing the airway, usually with a cuffed endotracheal tube.

This was not available in Virginia’s case: Ian Magill did not invent the soft endotracheal tube until 1919, and cuffed endotracheal tubes were not in use until 1931 or 1932. She had to endure

gastric lavage, which would have been particularly hazardous, with the risk of aspiration of gastric contents or lavage fluid, and subsequent pneumonia. In the pre-antibiotic era this could have grave consequences. Despite the danger, though, Doctors Keynes and Head did exactly what contemporary medical opinion would have held them to do in this case. The fact that Virginia made repeated suicide attempts despite the very harrowing nature of gastric lavage tells us just how disturbed her mind became. They believed that gastric lavage was necessary even though in all probability its side-effects risked endangering her life.

It is intriguing that of all those involved in Virginia Woolf’s first suicide attempt, one or two became famous, and others achieved career success but sank into obscurity. Sir Henry Head is remembered today in part as a minor character in Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy of novels but in medical circles is praised for his seminal work with Dr William Rivers on peripheral nerve innervation. Sir George Savage by contrast is largely forgotten, although evidently Virginia overcame her earlier doubts about his treatments, because she attended his practice on and off over the next decade. Ka Cox is only remembered as the lover of Rupert Brooke; Sir Geoffrey Keynes had proposed marriage to her in 1912 and did so again in 1914, but she turned him down on both occasions. He went on to become an eminent surgeon and man of letters. Leonard Woolf and Roger Fry are still renowned as members of the Bloomsbury Group. Virginia Woolf towers, however, above them all. Whether or not Keynes was correct in his belief that he had saved her (and her future masterpieces) we cannot truly know, but it seems likely that the presence of such a dynamic and decisive young doctor would have been hugely reassuring to the group at 38 Brunswick Square. With his and Head’s help, this promising young writer survived that night, and when eventually she did die, it was the death of a great novelist.

Professor Ian Franklin is a haematologist and has worked in Birmingham, Glasgow and Dublin. He has recently retired as Medical and Scientific Director of the Irish Blood Transfusion Service and previously was in a similar post in Scotland. He is Emeritus Professor of Transfusion Medicine in the University of Glasgow and welcomes enquiries about his research (E [email protected]).

14 | Wellcome HISTORY

Force-feeding and medical ethicsPrison medicine’s roles in therapy and discipline, 1909–80

Ian Miller

Should hunger strikers be force-fed? How should prison doctors care for starving prisoners? And

in what ways does hunger striking impact upon prison medical activity? Medical professionals first posed these ethically driven questions in 1909 when prison doctors began to force-feed imprisoned suffragettes in Winson Street Gaol, Birmingham. Throughout the 20th century, the medical-ethical dimensions of hunger-strike management continued to pose problems when Irish republicans, World War I conscientious objectors, IRA members and other prisoner groups staged protests involving food refusal. More recently, the force-feeding of detainees in Guantánamo Bay and African-American prisoners in California has brought the issue once again to the fore of international public debate.

Recent research brings fresh perspectives to this complex topic, extending beyond the purely political to focus on the history of the body, medical intervention to prevent starvation, and the ethical behaviour of prison staff. In particular, it examines two contrasting policies: force-feeding versus allowing prisoners to starve. One of the project’s key findings is that medical ethics on issues such as force-feeding were deeply informed by the 20th-century evolution of bioethics into a discrete discipline. This shifted ideas about human rights and escalating concern about prison welfare and prisoner rights. By interweaving these lines of inquiry, new research is able to make a significant contribution to histories of medicine in the British Isles, medical ethics and bioethics, as well as medicine and gender, informing Anglo-Irish and Anglo-Northern Irish relations.

Hunger strikers, prison staff and government bodies left an array of official, autobiographical and propagandistic accounts of force-feeding and self-imposed starvation. These provide opportunities for the historian to recapture the physical and psychological ordeal of prison

hunger striking. One of the most important questions first raised by the militant suffragettes – and which remains a current debate in relation to Guantánamo Bay prisoners – is whether prison force-feeding is therapeutic or coercive. Is it really used as a kind mechanism that prevents prisoners from starving or is it instead used to subjugate rebellious prisoners?

Between 1909 and 1914, those that advocated force-feeding insisted that prison doctors were fully complying with their ethical obligation to preserve life and health in the controversial cases of militant suffragettes. The Home Office portrayed prison feeding procedures as therapeutic in nature, not disciplinary, and as indispensable life-preserving

mechanisms. Officials presented so-called ‘artificial feeding’ as safe, humane and ethically uncomplicated. Nonetheless, suffragettes portrayed the procedure as torturous, degrading and life-threatening. From the prisoner’s perspective, force-feeding was not life-saving; instead, it caused vomiting, nightmares and intense pain.

However, while force-feeding was initially most associated with the suffragettes, the procedure was used on a plethora of political and non-political prisoners throughout much of the 20th century. Irish republican Eamon O’Dwyer later recounted his experiences of being force-fed at Mountjoy Prison, Dublin:

”I certainly did not like this pipe being passed down through my throat

Mural of Bobby Sands – IRA prisoner and hunger striker – on Falls Road, Belfast. PPCC Antifa on Flickr

Winter 2014 | 15

and I began to have a horror of it. I must admit that I was very much afraid of it, and often in years afterwards I woke up and felt this damn pipe or tube going down my neck like a snake. Every one of the crowd who suffered this vomited terribly. The days passed with this as the only relief from the monotony of being held in the cell.”

For O’Dwyer, force-feeding was not only highly uncomfortable, but also left a lasting emotional impression.

In 1917, Irish republican Thomas Ashe notoriously died in Mountjoy following a bout of force-feeding. Liquid food had accidentally slipped into Ashe’s lungs and precipitated a fatal heart attack, causing national outrage in Ireland. After Ashe died, the government mostly abandoned force-feeding in Ireland. Given this context, it seems remarkable that the procedure continued to be sanctioned for British conscientious objectors throughout World War I. In 1917, J W Illingworth was force-fed with a nasal tube 135 times in Birmingham Prison. Between 1917 and 1918, Frank Higgins was force-fed 22 times at Newcastle Prison, followed by a prolonged period involving 188 feedings.

Yet when conscientious objector William Edward Burns died in Hull Prison in 1918 following a period of force-feeding, the Home Office feared that public opinion would be inflamed and drawn towards the cause of conscientious objection in much the same way that Ashe’s death had allowed republicans to amass support for Irish independence. Burns had decided to pursue a hunger strike on the basis that he was receiving inadequate medical attention. By refusing food and worsening his health, he sought to secure a transfer to a nursing home. Nonetheless, he was force-fed with one pint of milk and one pint of cocoa through a stomach tube. During a second feeding, he began to spasm, splutter and regurgitate his food. After Burns had settled down, Dr Howlett, the prison doctor, continued his work. The following morning, the prisoner awoke with an alarmingly high temperature, of 101 degrees Fahrenheit, and a sharp pain in his side. Fearing that Burns had developed pneumonia, Howlett removed him to a hospital cell, where he continued to be force-fed twice a day until he eventually died. Burns had fatally taken action in

a prison environment that disallowed protest – no matter how valid – and discouraged autonomy. Although it is possible that Howlett genuinely believed that force-feeding held some therapeutic benefit, it seems likely that he also recognised the disciplinary value of the procedure in restoring order and quelling recalcitrance.

Is force-feeding used as a kind mechanism that prevents prisoners from starving or to subjugate rebellious prisoners?

Even despite these well-publicised casualties, prison doctors continued to force-feed fasting prisoners. Recent research has uncovered 7,734 occurrences of force-feedings in English prison between 1913 and 1940. Although detailed archival evidence does not exist relating to the period after World War II, frequent journalistic reportage indicates that the procedure remained in common use in prisons until the 1970s. The vast majority of convict hunger strikers endured less than one day of force-feeding before they resumed eating, demonstrating the efficacy of gastric technologies in suppressing institutional protest. Those subject to force-feeding included prisoners who were suicidal, mentally ill, in need of medical care, or simply unable to eat their unpalatable prison food. Starting in 1935, Henry Gordon Everett, imprisoned for attempted suicide, endured 474 feedings with a nasal tube over approximately 15 months.

In the 1970s, the controversial feedings in British prisons of IRA prisoners Frank Stagg and Michael Gaughan, and feminist civil rights campaigners Marion and Dolores Price, led to public pressure being placed on the Home Secretary to abandon the practice. Stagg’s jaw was dislocated during the procedure, Gaughan died from a lung puncture caused by a stomach tube, while the Price sisters weakened to a state approaching death. Consequently, the World Medical Organisation declared force-feeding as a torturous, degrading mechanism of punishment in 1975. This formed part of a broader recognition of prisoner rights in the modern period.

But what other options existed for prison medical staff to deal with hunger strikers? Was allowing prisoners to starve to death really more ethical than feeding them? Many prison doctors undoubtedly felt uncomfortable about force-feeding, yet overseeing a slow prison death through food refusal raised its own ethical problems. We can use autobiographical and oral-history testimony to recapture the experience of slow starvation and shed light on the physical and psychological aspects of prison fasting. Although the prolonged deaths of Terence MacSwiney (1920) and Bobby Sands (1981) remained firmly entrenched in popular memory, thousands of other politically motivated prisoners, now often forgotten, endured protracted periods of prison starvation. They experienced physical and emotional collapse, hallucinations, rapid wasting and delusions. By 1981, shifting bioethical regimes ensured that the Maze Prison hunger strikers, including Sands, could not be fed. Prison doctors could now only provide relief, chart the deteriorating health of hunger strikers and strive to offer humane care in a challenging ethical situation.

Examining the history of force-feeding from medical-ethical perspectives holds the potential to shed new light on a number of policy areas. These include: shifting attitudes towards the imprisoned body; the impact of developing 20th-century concerns about prisoner and human rights on institutional life; medicine’s function in periods of intense national or international conflict; and the contested role of prison medicine as either benevolent or disciplinary. In addition, it brings into sharper historical focus important experiential aspects of key political movements (including feminism, conscientious objection and Irish republicanism) to be uncovered and understood in new ways.

Ian Miller is a Wellcome Trust Research Fellow in Medical Humanities at the Centre for the History of Medicine in Ireland, University of Ulster. His publications include A Modern History of the Stomach: Gastric illness, medicine and British society, 1800–1950 (2011), Reforming Food in Post-Famine Ireland: Medicine, science and improvement, 1845–1922 (2014) and Water: A global history (2015). He has published extensively on prison medicine and force-feeding, and would be very interested in sharing his research findings (E [email protected]).

16 | Wellcome HISTORY

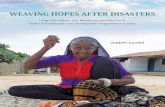

Hopes, fears and frustrated dreamsInfertility in early modern England

Jennifer Evans

IVF has helped many infertile couples have children since 1978. Yet, as the historian Professor

Lisa Jardine recently highlighted, people seldom talk about the times when IVF treatments fail. Soon after her public statement, BBC Magazine published an article entitled ‘I wish IVF had never been invented’, which featured testimonies of people who had struggled with infertility and IVF treatments. These testimonies showed people’s hopes, fears and frustrated dreams of fertility: some spoke of being given nothing but false hope, others spoke of their devastation when the treatment failed. Several spoke of the sense of being in a raffle with no sense of how many times they should buy a ticket. This frustration was echoed by those who lamented the ‘postcode lottery’ system that means couples in one NHS area may get treatment for free, while others nearby have to pay. The search for treatments and the feelings of helplessness and frustration experienced by these couples is part of a long history of fertility medicine, and we can see that early modern men and women expressed the very same hopes and fears.

In his diary Samuel Pepys recorded that on 25 July 1664 he had been at a dinner celebrating the birth of Anthony Joyce’s newborn infant, and when everyone was merry he asked the women their opinions and advice on his “not getting of children”. Pepys had been married to his wife Elizabeth for over eight years at this point, and as his diary reveals he was full of hopes and fears about their fertility. The gossips (the women and female friends who had attended the mother during childbirth and her recovery) happily recited their best advice for promoting conception, including the suggestion that Pepys should drink the juice of sage and eat toast with Tent (a type of wine). These suggestions evidently did not work and by September Pepys appeared more despondent about his and Elizabeth’s inability to have children. He wrote in his diary that after dinner with a friend he returned

home, “where I find my wife not well – and she tells me she thinks she is with child; but I neither believe nor desire it”. Pepys was not alone in feeling anxious about fertility. Another diarist, Sarah Savage, prayed to God, just two months after her own wedding, that she should be a “fruitful vine”. Her story would have been familiar to many women, as she suffered a series of miscarriages and disappointments before finally becoming a mother.

The desperation of childless women and those who struggled to conceive was also captured in 17th-century popular literature. In one pamphlet, called Fumblers-Hall, wives lamented the inability of their husbands to provide them with children and moaned about the way

their neighbours treated them. One wife complained that she had tried everything to make her husband fertile but she was still taunted and jeered at by her neighbours, who called her a “Barren-Doe”. Another wife mourned that her husband was very loving but that this was not enough: “will love beget such beautiful Children as my neighbour K. or my neighbour B. hath, no, no love will not do it alone.” Although these particular wives were fictitious, these stories were designed to resonate with popular thought, and suggest that early modern women could be scorned and ridiculed if they failed to become mothers. Pamphlets also suggest that childless women envied their more fertile neighbours. Indeed,

A physician examining urine brought by a woman. Wellcome Images

Winter 2014 | 17

Sarah Savage recorded in her diary that she envied her sister, who conceived very soon after marriage.

Continual disappointments could strain a couple’s relationship. William Salmon noted in Systema Medicinale (1686) that it was not uncommon for couples to quarrel over who was to blame for their infertility. This is an important point, as it has often been claimed that women were automatically and inevitably blamed for infertility in the early modern period. However, the discord that arose between couples suggests that it was common knowledge that the problem could be with either the male or the female body. To settle such disputes men and women utilised a range of diagnostic tests. Some of these only scrutinised the female body. They used scents and aromas to ascertain whether a woman’s body was free from blockages and obstructions. For example, a clove of garlic, or some other pungent substance, was placed at, or just inside, the woman’s genitals. If she could smell the fragrance in her nose, or if her breath smelled of garlic, then she was considered to be fertile; if the smell failed to travel through her body, then the test revealed that she was barren. Alternatively, the couple could use a range of urine tests to establish who was the most fertile. In this case both the man and the woman would ‘water’ (urinate on) some barley, or other grain, planted in a pot; the barley that grew first demonstrated its water-bearer’s greater fertility. Urine could also be scattered over sage, and whoever’s withered first was accounted barren.

Those couples fearful of being unable to conceive, like Pepys, tried to find remedies that would make them more fertile. Medical treatises offered a range of remedies to combat barrenness, including numerous aphrodisiacs. Sexual stimulants were believed to reinvigorate the reproductive system, improve fertility, stimulate sexual pleasure and ensure that sexual intercourse – the fundamental prerequisite to conception – occurred. Lazarus Riverius’s Practice of Physick (1658), for example, claimed that “A Woman very desirous of Children, but having no appetite to Carnal Embracements entreated me that I would kindle in her the desires of the flesh”. This woman was offered a mixture of well-known aphrodisiacs including eryngo

roots, satyrion (a type of orchis) and flying pismires (ants) to reignite her lacklustre libido. Popular beliefs about aphrodisiacs were widespread and did not have to be gained from a medical book. People would happily share this knowledge with those in need, as shown by Pepys’s case. In The Ten Pleasures of Marriage (1682), a satirical commentary on matrimonial bliss, a sorrowful bride seeks the help of her neighbours. They take pity on her and advise her and her husband to eat oysters, eggs, lamb’s testicles, caviar and chocolate, all of which were recognised aphrodisiacs.

Remedies could also be purchased from a range of medical and irregular sellers. In the 17th century, handbills – one- or two-sided advertisements – suggested that practitioners had a great secret remedy for infertility that they had made use of successfully for many years. In the 18th century, remedies like the ‘Prolifix Elixir’ and the ‘Vivifying Drops’ could be purchased through the newspapers. The Vivifying Drops cost 5 shillings and came, helpfully, with directions; they promised to “rectify the languid State of all the Fluids, rouse, fortify, and increase the Spirits, invigorate the Nerves… and cause a sparkling Gladness and ardent courage to flow in the Heart”, all of which was designed to promote conception and “render both Sexes prolifick in a wonder Manner”. Although it cannot be definitely established, the frequency with which these advertisements appeared suggests that the remedies they peddled were popular and sold well. The willingness of practitioners and sellers to advertise such services and remedies suggests a great number of men and women were desperately seeking help for their fertility problems.

Women, and men, also shared with friends and acquaintances their knowledge of a range of remedies designed to improve fertility. As we have already seen, Pepys asked the advice of several women while at a social gathering. In numerous recipe books, manuscript collections kept by families, we can also glimpse this shared network of reproductive knowledge. It is apparent from the titles and notes accompanying these remedies that women could be waiting for many years before finally having a child. A recipe in the collection of Lady Asycough was accompanied by a short note saying that Mrs Horne had been married four years without having children until, “upon the taking thereof”, she conceived. A similar note in a collection from the Wellcome Library suggests that a Mrs Patrick shared her remedy with a woman who had been childless, or struggling to conceive, for nine years. These women shared their desires, hopes and frustrated dreams of childbearing and worked together to try to help each other conceive the children they longed for.

As with today, it is apparent that fertility and childbearing were not a given for all couples in the early modern period. Men and women felt peer pressure to conceive, expressed their fears and frustrations about their fertility, and went through potentially long processes of testing and treatments in the hope that they would, as Sarah Savage described, become a fruitful vine and produce offspring.

Dr Jennifer Evans is a Lecturer in History at the School of Humanities, University of Hertfordshire. She specialises in the body, medicine and gender from 1550 to 1750. Her current research focus is the understanding of infertility and its treatments in early modern England. Jennifer has published widely on these topics in Historical Research, Women's History Review and Social History of Medicine. Do get in contact with her if you are interested in her latest findings (E [email protected]).

‘The First Day of Oysters’, by William Greatbach, after A Fraser. Wellcome Library

18 | Wellcome HISTORY

Dysfunctional diasporas?Migration and mental illness

Marjory Harper

When 31-year-old Malcolm was admitted to the Royal Asylum at Gartnavel in

Glasgow in October 1859, on the petition of his mother, his previous occupations were listed as “seaman, gold-digger, merchant, and clerk”. At the time of admission he was declared to be “of unsound mind, and suffering under a severe attack of brain disorder” which manifested itself in incoherence and delusions. He was, moreover, the asylum register warned, “very dangerous”. Eight months later, however, Malcolm was discharged, “recovered”, and left almost immediately for Australia, “with the intent of advancing himself in life, but without any settled plan”. It was not his first experience overseas: during an earlier sojourn in America he had first received private psychiatric treatment, before returning to Glasgow to the care of his family and subsequently the custody of the Royal Asylum. Shortly after arriving in Melbourne in 1860, Malcolm corresponded briefly with his brother, a bush missionary, and the two arranged to meet. That rendezvous did not take place, and Malcolm was never heard of again.

Malcolm’s illness may have had hereditary roots, since both his late father and subsequently one of his sisters had been detained in the Royal Edinburgh Asylum. But his unfinished story also demonstrates the phenomenon of the dysfunctional diaspora, notably the perceived relationship between intercontinental migration and insanity across the British world, which was well documented in investigative reports, institutional records and legislation, not least by the bureaucratic infrastructure that underpinned the imperial enterprise. That rich seam of evidence has been mined intermittently by historians in recent decades, but until now has not been scrutinised within a comparative multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary context.

At the heart of recent research is a strategy to integrate historical studies with the scholarship of psychiatrists,

theologians, lawyers, sociologists, anthropologists, policy makers and literary specialists. The strategy will be implemented initially through two symposia, in Halifax (Nova Scotia) and Aberdeen. The Halifax event will root the study of mental health issues within the much wider context of medicine and migration to Canada since the 19th century, harnessing topics of historical exploration to analogous and ongoing contemporary debates. It will bring together historians with current policy makers and practitioners in order to explore continuities and changes of attitude and experience in areas such as immigration policy and public health, migration and communicable diseases, child migration, detention and deportation,

and the recruitment of immigrants as health professionals. The Aberdeen conference will turn the spotlight more exclusively on mental health issues in historical and contemporary contexts, evaluating triggers and treatments through a variety of complementary disciplinary lenses. The project is in its infancy, so these multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary bridges still need to be built.

My own interest – which arose initially out of long-standing scrutiny of the 19th- and 20th-century British diaspora – is on the causes and consequences of insanity among immigrants to Canada in the half-century from Confederation to World War I. I have developed some preliminary

Migrants about to set sail, saying goodbye at the Glasgow docks. After Henry O’Neil, 1891. Wellcome Images

Winter 2014 | 19

hypotheses about causation, based primarily on the records of the British Columbia Provincial Asylum for the Insane in New Westminster.

What were the catalysts for mental breakdown among migrants? And can we demonstrate anything more than circumstantial evidence of a link between migration and insanity? The central question is whether the phenomenon was attributable to an inherent restlessness that had spawned the decision to migrate in the first place, or whether it was triggered by the traumatic repercussions of relocation. The reports of immigration officials in the host lands, and the gatekeeping policies they adopted, tended to emphasise the former, while the case notes of asylums incorporated pre-migration background factors within a much wider analysis of environment and experiences in the new country. Sub-themes to ponder in addressing causation include the relevance of gender, occupation and religion, as well as ethnicity. How did the proportions of different ethnicities in asylums relate to their presence in the population of Canada as a whole? Did the proportions of English, Welsh, Scottish and Irish patients reflect their distribution across

the British Isles? How did perceptions of mental illness among migrants to Canada compare with diagnoses and aetiologies in other parts of the British world? And did theories of causation change over time, both within medical circles and in society at large?

Migrant diaries, letters and memoirs are dotted with recollections of traumatic transitions from old to new worlds: the dilemmas of decision making, the pain of parting, and the discomforts of the journey. In most cases the difficulties were short-lived or manageable, but asylum records occasionally indicate that they were catalysts for mental breakdown. Mrs C from Edinburgh, for instance, who was admitted to the British Columbia asylum in 1890, fell ill, according to her case notes, because of “indisposition and the long trip from Scotland to BC”, during which she had taken opium and attempted suicide. A bad voyage experience was by no means confined to transatlantic travellers: in Angela McCarthy’s sample of foreign-born patients who were admitted to Dunedin’s public asylum within a year of arriving in New Zealand, 8 per cent were said to have been affected deleteriously by the long voyage.

Disappointed expectations feature particularly prominently in migrant testimony and asylum records alike. While these setbacks were often related to work, wages or living standards, they sometimes involved more inflated notions.

Malcolm, whose insanity was first manifested in America, presumably the location of the gold-digging episode in his patchwork of employments, may have been lured to Australia by the Victorian gold fields. We might speculate that both his initial breakdown and his subsequent disappearance were partly a consequence of his failure to find the anticipated El Dorado in either land. Across the world, some of the most disillusioned migrants in the 19th century must have been the restless prospectors who travelled in a vain quest for gold. Not surprisingly, British Columbia was a major magnet, with the Cariboo discoveries of the 1860s and the Klondike stampede three decades later. Just over 6 per cent of the 1,110 patients admitted to the BC asylum between 1872 and 1900 were described as “miners” or “prospectors”, many of whom had delusions about being robbed of their

A family in Glasgow listens to a letter from a migrant relative. After Thomas Faed, 1891. Wellcome Images

20 | Wellcome HISTORY

claims. One Scottish miner claimed to have made over $40,000 from gold mining in the Cariboo, and a Welsh patient was described as a “monomaniac on the subject of gold”.

Immigrants deemed to be mentally or physically defective were always at the top of the list for deportation

Disappointed expectations were exacerbated by the isolation and extreme climate of the Klondike, but environmental disillusionment was not the preserve of prospectors who moiled in the extractive industries of the BC frontier. It is hoped that the current project will in due course incorporate analyses from asylums in other parts of Canada, not least the prairies and the Maritimes. Many prairie settlers bewailed the featureless monotony of their surroundings, and when the Countess of Aberdeen visited the infant Hebridean settlement at Killarney in Manitoba in 1890, she was repelled by the “inexpressible dreariness of these everlasting prairies” where “the struggle to live has swallowed up all the energy”. Across the border, the Norwegian novelist O E Rölvaag charted the descent into insanity of a pioneer settler’s wife as the family’s wagon train moved westwards “beyond the outposts of civilization” across the infinite, formless prairie which “had no heart that beat, no waves that sang, no soul that could be touched – or cared”. Similarly, on the other side of the world, “secluded life on a station” was blamed for the illness of a Scottish shepherd who became a long-term patient at the Sunnyside Asylum in Christchurch, New Zealand, in 1851.

Of course, none of these factors operated unilaterally. Unfulfilled expectations, loneliness and an alien environment could trigger or exacerbate homesickness, which, in extreme cases, could lead to mental illness. Although admission registers did not articulate the problem in those terms, it was clearly evident in correspondence, which highlights another theme and provides a bridge to the second strand of the research agenda – for relatives, doctors and politicians did not speak with one voice about either the causes or the treatment of mental illness.

Heredity was the main bone of contention. It was, as we have seen, a possible factor in the illness of Malcolm the gold digger, and it was cited in over 6 per cent of admissions to the British Columbia asylum. Britain was accused of exporting migrants who were already of “unsound mind”, and doctors and policy makers across the dominions collected evidence of previous hospitalisation or hereditary insanity. But some families hotly disputed such stigmatisation, as we see in the case of a man called Richard, who was sent from the Klondike to the BC Provincial Hospital in 1900. A diagnosis of paranoia elicited an indignant letter from his father in Hertfordshire, who challenged the Medical Superintendent: “What were the circumstances that caused the authorities to charge him with insanity? … I may say for your guidance there has never been any insanity in our family… I am much inclined to judge he has been the victim of an outrage”.

In 1894 Jane, a nurse-maid, was admitted briefly to the BC asylum, suffering – according to the accompanying medical certificates – from “religious mania”. She was upset about a recent schism in the Free Church of Scotland and maintained that “until one of her own people from her own country comes to talk to her in Gaelic nothing will be right”. And when a man called Kenneth was admitted to the same institution 13 years later, one of his certificates reported that he “talks and shrieks in Gaelic continuously. Will not answer any questions, nor talk in English, merely yells in Gaelic”. With these exceptions, the BC asylum records examined to date did not discuss patients’ maladies with any reference to their ethnicity. This is notably different from documentation in New Zealand, where Angela McCarthy has demonstrated a very clear thread of ethnic stereotyping in both medical reports and official returns from the same era. The absence of ethnic labelling in the BC asylum records is surprising, particularly in the eugenics-dominated decade before World War I, when Canadian commentators frequently asserted that weak-minded immigrants from Britain were polluting their society and draining their economy: an article in the University Monthly in 1908, for instance, asserted that a preponderance

of “English defectives” in the admission registers of Toronto’s asylums was a consequence of “the wholesale cleaning out of the slums of English cities”. Further research in the asylum records of other provinces may confirm or contradict the BC approach, but that is a question for another day.