High-involvement work processes, work intensification and employee well-being: A study of New...

Transcript of High-involvement work processes, work intensification and employee well-being: A study of New...

http://apj.sagepub.com

Resources Asia Pacific Journal of Human

DOI: 10.1177/1038411107086542. 2008; 46; 38 Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources

Keith Macky and Peter Boxall well-being: A study of New Zealand worker experiences

High-involvement work processes, work intensification and employee

http://apj.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/46/1/38 The online version of this article can be found at:

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Australian Human Resources Institute (AHRI)

can be found at:Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources Additional services and information for

http://apj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://apj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navReprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navPermissions:

http://apj.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/46/1/38SAGE Journals Online and HighWire Press platforms):

(this article cites 54 articles hosted on the Citations

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

38

High-involvement work processes, work intensification andemployee well-being: A study of New Zealand workerexperiences

Keith MackyAuckland University of Technology (AUT), Auckland, New Zealand

Peter BoxallUniversity of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

High-involvement work processes are at the heart of the current interest in high-performance work systems. A study of 775 New Zealand employees shows thatgreater experience of high-involvement processes is associated with higher jobsatisfaction. To a lesser extent, there are also better outcomes in terms of job-induced stress, fatigue and work–life imbalance. However, in situations wherepressures to work longer hours are higher, where employees feel overloaded andwhere managers place stronger demands on personal time, employees are likely toexperience greater dissatisfaction with their jobs, higher stress and fatigue, andgreater work–life imbalance. Increasing the availability of work–life balancepolicies for employees was not found to ameliorate these relationships. The studyimplies that organizations that can foster smarter working without unduepressures to work harder are likely to enhance employee well-being.

Keywords: high-performance work systems, high-involvement work processes, job satisfaction, stress,

work intensification

The notion of high-performance work systems (HPWSs) is no longer novel inthe literature on industrial relations and strategic human resource manage-ment. Studies of automobile assembly by MacDuffie (1995) and of US steel,

Correspondence to: Associate Professor Keith Macky, Department of Management, Business School, Auckland University of Technology (AUT), Private Bag 92006, Auckland,New Zealand; e-mail: [email protected]

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources. Published by SAGE Publications (Los Angeles, London, New Delhi andSingapore; www.sagepublications.com) on behalf of the Australian Human Resources Institute. Copyright © 2008Australian Human Resources Institute. Volume 46(1): 38–55. [1038-4111] DOI: 10.1177/1038411107086542.

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 2008 46(1)

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 38

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

apparel and medical electronics manufacturing by Appelbaum et al. (2000),among other works, have attracted widespread attention. At issue is whetherTaylorized or low-discretion production systems can be reformed throughgreater employee involvement in work decisions and through companioninvestments in skill formation and employee incentives. Such a move is seen asseriously consequential. Not only are many domestic manufacturing capabil-ities at stake in high-wage countries, but the increasing prevalence of ‘off-shoring’ in white-collar work shows there is a palpable threat to a variety ofservice jobs. Over the period from 2001 to 2003, 70 percent of the US workersdisplaced by global competition worked in services, not manufacturing (Jensenand Kletzer 2005).

Early reviews of the HPWS notion pointed to a confusing array of defin-itions (Becker and Gerhart 1996), much of this caused by theorists compilinglists of ‘best practices’ without establishing an internal logic for their chosen‘system’. A close reading of the leading studies noted in our first paragraph,however, reveals a theoretical logic stemming from desired changes to thestructure of work in industries where historical production systems have comeunder serious competitive threat (Cappelli and Neumark 2001). Changes inwork organization towards greater employee involvement, seen as necessary tocompete more effectively on quality, creativity and flexibility, lead logically toimprovements in skill formation (better training and selection to build thehuman capabilities needed) and an appropriate mix of incentives (to ensureworkers want to take part in new work processes and acquire new skills). AsMacDuffie (1995, 201) makes clear, in automobile manufacturing, reforms towork structure lead to changes in how management tries to manage employeeskill and commitment. While the set of practices needed is inevitably depend-ent on industry and occupational contexts (Appelyard and Brown 2001;Kalleberg et al. 2006), at the heart of the dominant HPWS model is a processof building higher levels of employee involvement in decision-making, on thejob and/or off it.

We find ourselves in the midst of a lively debate over the impacts ofHPWSs on firms and workers. There is a full spectrum of positions in thisdebate. Appelbaum et al. (2000) find benefits for both parties while otherstudies call into question the cost-effectiveness of HPWSs for firms (e.g.Cappelli and Neumark 2001; Way 2002). Some scholars find benefits forworkers (e.g. Guest 1999; Macky and Boxall 2007), while others report negativespillovers from work to home (e.g. White et al. 2003). Godard (2004), based ona review of a range of studies, questions the value of the ‘high-performanceparadigm’ for both parties. At this stage, the jury is still out.

Against this backdrop, the purpose of this paper is to investigate whetheror not greater exposure to the management processes associated with theemployee involvement aspects of HPWSs is associated with improvements inemployee well-being. Our interest is in the outcomes for workers. We examinea range of potential employee outcomes, being job satisfaction, job-induced

HIWP, intensification and well-being 39

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 39

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

High-involvement work processes and employee well-being

stress, fatigue and negative work–home spillover. The paper is organized in aconventional manner. We first build our hypotheses through a review of therelevant literature, then outline our research methods and measures. This isfollowed by the analysis of results and our discussion and conclusions.

Greater employee involvement is central to leading studies of HPWSs(Appelbaum et al. 2000; MacDuffie 1995). Like Pil and MacDuffie (1996), andVandenberg, Richardson, and Eastman (1999), we find it descriptively usefulto talk of ‘high-involvement work processes’ (HIWPs) when identifying thepathways through which HPWS practices are intended to affect employeeoutcomes and business performance (see also Godard 2004, 351). Vandenberg,Richardson, and Eastman (1999) develop a research framework based on Lawler’s (1986) ‘PIRK’ model: high-involvement processes encompassworkplace power (P), information (I), rewards (R) and knowledge (K). Thesefour variables are seen as mutually reinforcing. In other words, high-involve-ment work processes aim to empower workers to make more and betterdecisions, enhance the information and knowledge they need to do so, andreward them for doing so.

While there may be a normative assumption that high-involvementprocesses are a ‘win–win’ approach for organizations and their employees,there are both empirical and theoretical issues to consider here. On the onehand, there is research showing practices associated with greater involvementhave positive outcomes in terms of job satisfaction and organizational commit-ment (e.g. Guest 1999; Vandenberg, Richardson, and Eastman 1999; Wall etal. 1990). Also worth noting is Warr’s (1994) review of the environmentalfactors influencing positive self-perceptions of health at work, which lists manyof the factors associated with high employee involvement, including the oppor-tunity for control and autonomy over one’s work, the opportunity to utilizeone’s skills at work, the amount of variety in the work itself, the clarity ofcommunications regarding job expectations, and opportunities for interper-sonal interaction at work.

Pertinent here also is the ‘demand–control’ model of stress, which predictsthat jobs with higher demands combined with low employee discretion orcontrol will be those that create the most strain (Gallie 2005; Karasek 1979;Mackie, Holahan, and Gottlieb 2001). To the extent that employee involve-ment practices give workers greater control over their jobs, they should leadto a reduction in perceived job stress (Mackie, Holahan, and Gottlieb 2001)and positive health effects (Ettner and Crzywacz 2001). Both workload andautonomy therefore appear to be important determinants of stress.

On the other hand, we need to take stock of what high-involvementresearchers are actually positing. They are, in fact, theorizing that work

40 Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 2008 46(1)

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 40

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

practices building employee involvement achieve organizational benefitsthrough eliciting greater discretionary effort from employees. This is centralto Appelbaum et al.’s (2000) theoretical argument. In other words, HPWSsoperate by intensifying work (Cooke 2001; White et al. 2003): for example, byinvolving operating employees in decisions previously made by managers ortechnical specialists, by adopting work systems that require teamwork, or bylinking pay and other rewards to heightened job performance. In respect ofteamwork, a practice central to many conceptions of HPWSs, De Dreu andWeingart (2003, 741) point to ‘considerable’ challenges, not least because of theincreased potential for both task and relationship conflict leading to decreasedteam-member satisfaction. Teams may also intensify work through a socialcontagion effect (Brett and Stroh 2003) where norms defining appropriatelevels of work effort increase due to team performance goals and team-basedpay-for-performance, as does peer pressure to conform to these. Barker (1993)refers to such a phenomenon as ‘concertive control’.

Given an established relationship between work intensification andnegative employee outcomes (e.g. Landsbergis, Cahill, and Schnall 1999;Sparks et al. 1997; Yousef 2002), if high-involvement processes intensify workthrough increased discretionary effort, it seems reasonable to posit that theyshould also be associated with negative employee outcomes. Despite theirtheoretical model, this is not a link that Appelbaum et al. (2000) generally findin their data. They show job satisfaction and commitment improve in steel andmedical electronics manufacturing, and are lower among apparel workers inself-directed teams (Appelbaum et al. 2000, 113–14, 188, 191). They do not findnegative implications for stress (Appelbaum et al. 2000, 113, 198) and, onbalance, are up-beat about HPWSs and employee outcomes. There are otherstudies, however, which are much less sanguine. For example, White et al.(2003) find evidence for increased negative work-to-home spillover, whileGodard (2001) finds that higher levels of adoption of high-performancepractices lead to a decline in satisfaction and increased stress, and both stressand fatigue are associated with team-based work. Ramsay, Scholarios, andHarley (2000) also find an association for increased job strain and work inten-sification.

If high-involvement processes do intensify work and lead to reduced satis-faction and increased stress, we would also expect poorer work–life balance tooccur (e.g. Judge, Boudreau, and Bretz 1994). Interestingly, while Guest (2002)finds a strong correlation between longer working hours and reports ofwork–life imbalance, employees whose jobs had more scope for autonomy andparticipation had less imbalance. This is opposite to White et al.’s (2003)finding, and raises the possibility that work intensification might independ-ently serve to increase negative work–home spillover, while high-involvementwork practices decrease it.

Because of these conflicting findings, we propose the following competinghypotheses:

HIWP, intensification and well-being 41

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 41

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Hypothesis 1 : Perceptions of greater exposure to practices associated withhigh employee involvement will predict positive employee outcomes in the form of higher job satisfaction, lower stress and fatigue, and betterwork–life balance.

Hypothesis 2: Perceptions of greater exposure to practices associated withhigh employee involvement will predict negative employee outcomes in the form of lower job satisfaction, higher stress and fatigue, and poorerwork–life balance.

Sample and data collection

Data were collected through a computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI)survey using random sampling with replacement. Interviews of 1004 NewZealand employees were conducted in late 2005 by a professional survey firmcommissioned by the researchers. Of those contacted who met the criteria forparticipation in the survey – being employees aged 18 and over who hadworked for at least 6 months for an employer with 10 or more employees –the response rate was 34.2 percent. The telephone interviews took, on average,30 minutes to complete.

The findings reported here are based on 775 permanent employees whoworked at least 30 hours a week for their main employer.1 Respondents withmore than one employer (n = 35) were asked to respond to the survey questionsfor the job in which they currently worked the most hours. Most (58.9%) wereemployed in the private sector, followed by the state, either working in agovernment department (12.6%), a publicly funded organization such as ahospital or school (18.6%), or a state-owned enterprise (2.5%). The mediannumber of employees in the employing firm was 140 (range: 10 to 21 000). Mostworked in firms where a union was present that they could join (union reach= 63.5%), with 36.1% of these members of that union.

Respondents named over 450 distinct occupations across 17 majorindustry groups. Using the New Zealand standard classification of occupations(NZSCO) (Statistics New Zealand 2001), occupations were coded into themajor groupings, the largest of these being professionals (26.2%), followed bytechnical and associate professional (18.8%), managerial (16.1%), clericalworkers (11.8%), sales and service occupations (9.6%), and the trades andremaining occupations (17.6%). The main industry groupings were education

42 Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 2008 46(1)

1 A minimum of 30 hours is the official Statistics New Zealand cut-off point for defining a full-time employee.

Method

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 42

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

(19.3%), health and community (12.5%), manufacturing (9.6%), retail andwholesale (8.9%), agriculture, forestry and fishing (6.8%), construction (6.7%),business services (6.3%) and the finance and insurance industry (6.2%). Theremaining nine industry groupings each comprised between 1% and 5% of therespondents.

Slightly more females (54.2%) than males responded to the survey, theaverage age was 43.46 years (SD = 11.22) and slightly over half (51.4%) haddependents living with them at home. The median tenure with their mainemployer was 5 years (range = 6 months to 40 years), the mean hours typicallyworked per week in the respondent’s main job was 44.02 (SD = 8.39), and themedian typical take-home pay reported was NZ$700 (range = $200 to $2500per week).

Any study that collects all data from a single source using the samemethod may be susceptible to common method variance and, therefore,generate biased ‘percept-percept correlations’ (Wright, Gardner, andMoynihan 2003, 27). To reduce the potential for social desirability responses,one of the more likely sources of common-method variance in self-reportsurveys (Kline, Sulsky, and Rever-Moriyama 2000), questions pertaining to theemployee outcome variables were asked before the questions dealing withpeople’s experiences of work practices. It is also worth nothing that the sevenscale variables used to predict employee outcomes were found to be factoriallydistinct from each other, as were the four dependent variables. (Results of thefactor analysis are available from the authors.) As others have noted (e.g.Whitener 2001), demonstrating the factorial independence of measures goessome way to obviating concerns over common-method variance. It is alsoworth noting that the unrotated factor solution for all the scale items identi-fied 11 factors, each corresponding to the a priori scale variables, with thesingle largest factor accounting for only 28.6 percent of the variance; whichfalls somewhat short of any marked degree of common method variance(Podsakoff and Organ 1986; Podsakoff et al. 2003). Furthermore, apart fromthe self-report perceptual data, we only asked for easily recalled factual data ofa personal nature (e.g. age, tenure, hours of work) and these are not particu-larly susceptible to common method variance (Crampton and Wagner 1994).

Measures

All scores for the scale variables were created by averaging the relevant itemswhich, except where otherwise stated, were coded on a 7-point Likert-scalescored from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 ‘strongly agree’. Negatively worded itemswere reverse scored so higher scores represent higher levels of the constructbeing measured. In all instances, only scales previously reported in the litera-ture as having sound psychometric properties have been used to measure thevariables of interest.

HIWP, intensification and well-being 43

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 43

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Work intensification

Measuring the ‘hours worked’ over some defined time period is notuncommon in studies of work intensification and work–life balance (e.g., Dexand Bond 2005; Frone, Yardley, and Markel 1997; White et al. 2003). In thepresent study, participants were asked to state how many hours they usuallyworked each week in their main job, including paid or unpaid overtime orextra hours or any work that they might bring home at night or on weekends.As a potential control variable, respondents were asked to report the numberof hours worked in their main job in the week immediately prior to the survey.No significant difference was found between the usual and actual hoursworked (t (772) = –0.84, p = 0.400), so the latter variable has not been used.

Work intensification was also measured using a six-item measure of‘work-role overload’ combining, as others have done (e.g. Arynee, Srinivas, andTan 2005), the three items from Beehr, Walsh, and Taber’s (1976) measure withthe three items from the MOAQ overload subscale (items sourced from Cooket al. 1981). Defined as ‘having too much work to do in the time available’(Beehr, Walsh, and Taber 1976, 42), example items are: ‘It often seems like Ihave too much work for one person to do’ and ‘There is too much work to doeverything well’. A coefficient alpha for the scale of 0.84 was obtained.

Work may also be intensified through the perceived demands and expectations management places on employee time that might interfere withnon-work activities. A four-item measure of ‘time demands’ developed byThompson, Beauvais, and Lyness (1999) was used. Item wording was slightlymodified from the original measure to read: ‘To get ahead in the organisation,employees are expected to work more than their contracted hours each week’,‘Employees are often expected to work overtime or take work home at nightand/or weekends’, ‘Employees are regularly expected to put their jobs beforetheir families or personal lives’ and ‘To be viewed favorably by senior managers,employees in my organisation must put their jobs ahead of their family orpersonal lives’. A coefficient alpha of 0.85 was obtained for the modified scale.

High-involvement work processes

Two distinct approaches to the measurement of employee involvement are discernable in the literature, being management reports of organization or establishment-level practices (e.g. Green 2004; Huselid 1995; Lawler,Mohrman, and Ledford 1998) versus operationalizing involvement via theaffective responses of individual employees (e.g. Mackie, Holahan, andGottlieb 2001; Vandenberg, Richardson, and Eastman 1999). The secondapproach was used here on the assumption that it is employee experiences ofmanagerial policies and practices, and their reactions to these experiences, thatare more important to employee-level outcomes than managerial assertionsabout the organizational application of such policies and practices. The four

44 Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 2008 46(1)

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 44

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

high-involvement scales developed by Vandenberg, Richardson, and Eastman(1999) were used with responses obtained on a 5-point Likert-scale scored from1 ‘Strongly Disagree’ to 5 ‘Strongly Agree’. Higher scores are therefore indica-tive of greater subjective experience of high-involvement work processes. Thevariables were:

• ‘power’ to make decisions and act autonomously in all aspects of one’swork (7 items; coefficient alpha = 0.91);

• ‘information’ provision regarding organizational mission, goals, policies,procedures and changes, reasoning behind critical company decisions, andimportant business unit issues, as well as employee voice opportunities (11items; coefficient alpha = 0.93);

• ‘rewards’, both intrinsic (praise, recognition, and personal development)and extrinsic (promotion and pay), being tied to personal job, team andorganizational performance (9 items; coefficient alpha = 0.90);

• ‘knowledge’ of the job to be done, including the opportunity to obtainskills and training and development opportunities (8 items; coefficientalpha = 0.95).

In addition to the Vandenberg, Richardson, and Eastman scales, a six-itemmeasure of ‘teamworking’ (Knight-Turvey 2004) was used given the potentialimportance of such organizational structures to facilitating employee partici-pation, information sharing, skill development and rewards (coefficient alpha= 0.88).

Employee well-being

Four variables were used as dependent variables in the present study: job satis-faction, fatigue, job-induced stress, and work–life imbalance.

• ‘Job satisfaction’ was measured using Warr, Cook, and Wall’s (1979)original 15-item instrument with an additional item measuring satisfac-tion with the degree of involvement in decisions. Responses were obtainedon a 7-point scale bounded from 7 ‘very satisfied’ to 1 ‘very dissatisfied’(coefficient alpha = 0.90).

• ‘Fatigue’ was measured using Beehr, Walsh, and Taber’s (1976) three-itemmeasure (alpha = 0.72).

• ‘Job-induced stress’ was measured using House and Rizzo’s (1972) 7-itemscale with responses scored so that higher scores represent greater feltstress. Coefficient alpha for the measure was 0.85.

• ‘Work–life imbalance’ was measured using an instrument Frone andYardley (1996) developed to measure work–family conflict. However, thewording of the six items goes somewhat beyond family to include negativework spillover to non-familial aspects of personal life and friendship. The

HIWP, intensification and well-being 45

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 45

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

response scale was ‘never, seldom, sometimes, often, very often’, boundedfrom 1 to 5, with higher scores suggesting greater negative spillover fromwork to non-work life and therefore greater work–life imbalance.Coefficient alpha was 0.90.

Control variables

A number of organizational and participant variables were analyzed aspotential control variables: respondent age, gender, number of dependents,tenure with main employer, weekly pay in main job, NZSCO occupationalcategory, firm size, and whether or not a union was present at the participant’sworkplace that they could join. Because of their skewed nature, the log oftenure, firm size, and weekly pay was used in these analyses to normalize theirdistribution.

On the assumption that any relationship between the experience of high-involvement work practices and employee outcomes might be ameliorated bypractices adopted by employers to help employees better manage theirwork–life balance, an index of such practices was developed and analyzed asa potential control variable. The correlations shown in table 1 are supportiveof such an assumption. A review of the literature identified 21 practicesassumed to assist employees to better balance work responsibilities with theirnon-work life (Allen 2001; Department of Labour 2003; Haar and Spell 2004;Judge and Colquitt 2004; Liddicoat 2003; Thompson, Beauvais, and Lyness1999; Wood 1999). These practices were: flexible working hours, job sharing,part-time work, compressed work weeks, flexible leave, parental leave beyondthe legal minimum, phase back for new mothers/fathers, telecommuting, on-site childcare facility fully or partially funded by the employer, near-sitechildcare facility fully or partially funded by the employer, childcare referralservice, employer subsidy of childcare, after-school programs for an employee’sdependents, school holiday programs for an employee’s dependents, eldercare,dependent-care carparks, unpaid special leave, employee assistance programincluding addiction and substance abuse programs, employee wellness orhealth promotion programs, time off in lieu to make up for overtime, andflexible shifts. An examination of the correlation matrix for all 21 itemsshowed the mean inter-item correlation to be 0.15 (range = –0.05 to 0.61). Thestrongest correlation, between after-school programs and school holidayprograms for employee dependents, is well short of indicating collinearity andthus item redundancy in the index. The inclusion of all items is thereforeunlikely to lead to overestimating the degree of association between the indexand outcome variables (Delery 1998; Delery and Shaw 2001; Guest, Conway,and Dewe 2004). Respondents were asked to indicate if the practice wasavailable to them (code 1), not available (code 0), or if they were unsure or didnot know if it was available (code 0) and the score calculated by simplysumming the responses coded 1 (Mean = 7.73, SD = 3.35).

46 Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 2008 46(1)

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 46

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Initial multivariate tests did not find any significant effects for union reach(trace (4, 695) = 0.19, p = 0.943), NZSCO occupational category (trace (20, 2792)= 0.94, p = 0.532), and the work–life balance practices index (trace (4, 695) =0.50, p = 0.739). These control variables were therefore dropped from thesubsequent analyses.

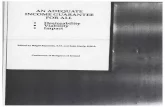

Univariate statistics and correlations between the measures are shown in table1. Visual examination of the scatterplots for each correlation did not reveal anyobviously non-linear relationships. Furthermore, the magnitude of the corre-lations between predictor variables does not suggest multicollinearity. Thestrongest correlations were 0.62 between the high-involvement variables ofinformation provision and the power workers have to make decisions and actautonomously, and also with having rewards tied to performance.

Interestingly, the hours worked by employees were found to be onlyweakly associated with perceptions of work-role overload and the timedemands of management. In turn, overload and time demands were positivelybut only moderately correlated with each other. These analyses lend supportto their use in the present study as informing on different dimensions of thework intensification concept. Further to this, hours worked was found to beindependent of employee job satisfaction and reported fatigue. However,employees working longer hours were slightly more likely to also report higherjob-related stress and greater imbalance in the work–life relationship (table 1).

Table 1 also shows the five high-involvement variables to be positivelycorrelated with job satisfaction and negatively correlated with fatigue, jobstress and work–life imbalance. While the latter associations tend to be weak,they lend support to hypothesis 1 rather than 2. It is also worth noting that nosignificant relationship was found between the five high-involvement variablesand hours worked, while the statistically significant correlations with overloadand time demands were all negative.

Table 1 also shows that the four dependent variables of job satisfaction,fatigue, job-induced stress and work–life imbalance are correlated with eachother, but not to an extent that suggests multicollinearity. Multivariate analysisof covariance (MANCOVA) was therefore used to directly test the competinghypotheses proposed in this study. Gender was entered as a factor variablewhile the remaining independent and control variables were entered into themodel as covariates.

Table 2 reports the tests of between-subjects effects and parameterestimates for each of the dependent variables. Bonferroni corrections wereapplied to all significance levels to reduce the potential for Type I errors arisingfrom multiple statistical tests. The Box’s M test of the equality of the covari-ance matrix was not significant (p = 0.225) and nor was the Levene’s test of the

HIWP, intensification and well-being 47

Results

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 47

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

48 Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 2008 46(1)

Tab

le 1

Uni

vari

ate

stat

isti

cs a

nd c

orr

elat

ions

Varia

ble

Mea

nS

D1

23

45

67

89

1011

12

1 W

eekl

y ho

urs

43.9

48.

33

2 W

ork

over

load

3.69

1.38

.17*

3 Ti

me

dem

and

s3.

351.

68.2

2*.4

6*

4 In

form

atio

n3.

52.9

1.0

3–.

28*

– .3

4*

5 P

ower

4.11

.80

.06

–.25

*–

.30*

.62*

6 R

ewar

ds

3.25

.95

.04

–.20

*–

.32*

.62*

.49*

7 K

now

led

ge3.

601.

05.0

5–.

16*

– .2

1*.5

8*.4

7*.5

5*

8 Te

amw

orki

ng4.

25.9

5.0

1–.

18*

– .2

4*.5

4*.3

8*.4

7*.4

9*

9 W

ork–

life

ind

ex7.

763.

34–.

08–.

16*

– .2

0*.2

8*.2

4*.3

3*.3

0*.2

8*

10 J

ob s

atis

fact

ion

5.16

1.00

.02

–.31

*–

.39*

.63*

.64*

.62*

.52*

.48*

.31*

11 F

atig

ue3.

401.

51.0

5.4

6*.4

0*–.

29*

–.31

*–.

22*

–.21

*–.

22*

–.17

*–.

38*

12 J

ob s

tres

s2.

901.

09.1

7*.5

1*.4

9*–.

37*

–.37

*–.

30*

–.25

*–.

24*

–.17

*–.

45*

.46

13 W

ork–

life

imb

alan

ce2.

59.9

8.3

0*.5

6*.5

5*–.

29*

–.27

*–.

27*

–.16

*–.

16*

–.18

*–.

36*

.46*

.65*

Not

es: N

= 7

20;

*

p<

.01

tw

o–ta

iled

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 48

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

HIWP, intensification and well-being 49

Tab

le 2

Test

s o

f M

AN

CO

VA b

etw

een-

sub

ject

s ef

fect

s an

d p

aram

eter

est

imat

es

Job

sat

isfa

ctio

nJo

b in

duc

ed s

tres

sW

ork–

life

imb

alan

ceFa

tigue

Varia

ble

sF

BF

BF

BF

B

Cor

rect

ed m

odel

(df

= 1

4, 7

22)

77.0

6***

.70a

34.8

4***

2.05

a45

.12*

**.7

5a23

.06*

**6.

07a

HIW

P v

aria

ble

s(d

f =

1,

708)

Pow

er /

aut

onom

y90

.67*

**.3

815

.05*

**–.

211.

71–.

086.

37*

–.20

Info

rmat

ion

pro

visi

on

15.1

1***

.16

1.41

–.07

.52

–.03

.11

–.03

Rew

ard

s50

.59*

**.2

5.4

9–.

034.

70*

–.09

.25

.04

Kno

wle

dge

and

tra

inin

g6.

51*

.08

1.15

–.04

.29

.02

.54

–.04

Team

wor

k10

.55*

*.1

0.1

6–.

021.

35.0

41.

54–.

08

Wor

k In

tens

ifica

tion

varia

ble

s

Wee

kly

hour

s.0

3–.

004.

78*

.01

35.3

9***

.02

.40

.00

Ove

rload

10.1

4**

–.06

84.8

1***

.25

111.

09**

*.2

482

.67*

**.3

6

Tim

e d

eman

ds

13.1

7***

–.06

46.3

7***

.16

86.5

9***

.18

31.7

2***

.19

Con

trol

var

iab

les

Gen

der

(0 m

ale,

1 f

emal

e)5.

45*

–.12

6.43

*–.

188.

06**

–.17

1.48

–.13

Age

8.39

**–.

013.

91*

–.01

.68

–.00

8.18

**–.

01

N d

epen

den

ts3.

91*

.04

.07

.01

7.42

**.0

6.3

6–.

02

Log

tenu

re.5

0.0

28.

39**

.10

1.21

.03

.21

.02

Log

wee

kly

pay

13.1

8***

.26

.95

.09

.03

.02

10.4

6**

–.45

Log

firm

siz

e2.

33–.

02.0

3.0

03.

78–.

03.1

8.0

1

Ad

just

ed R

2.5

96.3

96.4

61.3

00

N=

729

* p

< .

05

** p

< .

01**

* p

< .

001

a=

inte

rcep

t

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 49

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

equality of the error variances for job satisfaction (p = 0.799), stress (p = 0.713),work–life imbalance (p = 0.072), and fatigue (p = 0.557), indicating that theseassumptions underpinning the use of MANCOVA were met (Hair et al. 1998).

For the dependent variable of job satisfaction, significant main effectswere obtained for all five HIWP variables, and with the direction of theregression coefficients indicating higher perceived levels of power, informa-tion provision, rewards, knowledge and training, and teamwork to be associ-ated with higher job satisfaction. Table 2 also shows increased power to actautonomously to be associated with reduced job-induced stress and fatigue,while receiving rewards tied to performance was associated with lowerimbalance between work and non-work life. No HIWPs were found to besignificantly associated with the remaining employee well-being outcomevariables. These findings are more supportive of hypothesis 1 than 2.

With regard to the work intensification variables, longer hours of workwere found to predict increased stress and work–life imbalance, but were inde-pendent of job satisfaction and fatigue (see Table 2). However, significant maineffects were found for perceived work-role overload and time demands withall four well-being variables. Higher perceived overload and managerialdemands on personal time were associated with lower job satisfaction andincreased job-induced stress, work–life imbalance, and fatigue.

To explore whether the high-involvement variables interact with workintensification to predict employee outcomes, or act independently on these,the five involvement variables were combined into a single variable (Mean =3.76, SD = 0.73, coefficient alpha = 0.84). The MANCOVA analysis was thenrepeated substituting this new high involvement variable for the five originalones while including all other variables used in the original analyses.Multivariate tests found none of the interaction terms to be statistically signif-icant for the combined involvement variable with hours worked (trace (4, 706)= 0.66, p = 0.619), role overload (trace (4, 706) = 0.27, p = 0.896), and thedemand managers place on employee personal time (trace (4, 706) = 0.27, p =0.899). In terms of employee well-being, managerial practices encouraginghigh employee involvement appear to act independently of practices thatintensify work.

Our study of New Zealand workers adds strength to the idea that there arelikely to be gains for workers in an involvement-oriented model of HPWSs(hypothesis 1 rather than 2). In particular, we find a clear relationship betweenhigh-involvement work processes and employee job satisfaction. Our studyimplies that where employees’ experience of knowledge, information, rewardsand power increases, the employment relationship moves in a direction thatemployees find more satisfying. We also find that a greater sense of empow-

50 Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 2008 46(1)

Discussion and conclusions

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 50

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

erment is associated with lower fatigue and stress, while higher rewards areassociated with better work–life balance. Furthermore, we find no evidencethat employees who experience greater communication or who have greaterautonomy in their jobs or who perceive better performance-related rewardsor who have greater opportunities for training and development are morelikely to express negative outcomes in the form of increased stress or fatigue orpoorer work–life balance.

In respect of HIWPs, our results are consistent with the findings ofVandenberg, Richardson, and Eastman (1999) in a US insurance company andMackie, Holahan, and Gottlieb (2001) in a US healthcare facility, despite beingbased on a representative national survey of employees. This is interesting inthat all three studies draw their definition of high-involvement processes fromLawler’s (1986) PIRK model and all three studies adopt an approach whichhinges on measuring employee experiences and attitudes. Our findingstherefore throw light on employee reactions to the implementation of partic-ular kinds of managerial policy. As Purcell (1999) reminds us, so much of whataccounts for differences in the climate of employee relations relates to howpolicies are actually carried out.

Our fuller definition and measurement of the pathways through whichHPWSs are supposed to work may account for why we find a positive picturerather than the sort of negative outcomes reported by British researchers suchas White et al. (2003) and Green (2004), whose measures of high-performancepractices rely on the items available in existing surveys (Working in Britain andWERS). These surveys were designed for other purposes, thus offering feweritems that map less well onto an involvement model of HPWSs. In theirconclusions, Ramsay, Scholarios, and Harley (2000, 521–2) debate whetherthere are (implicit) theory and (actual) data limitations in these sorts of surveysthat make them less capable of capturing ‘the complex reality of the imple-mentation and operation of HPWSs’. Our study suggests there are.

On the basis of the evidence presented here, when HPWSs foster Lawler-style high-involvement work processes, there is a distinct possibility of a man-agerial ‘high-road’ to organizational success that also benefits employees.Enhanced autonomy and rewards, implemented with greater information-sharing and employee development and without greater pressure are indeedattractive. There is also, however, a ‘low-road’, consistent with much of theevidence elsewhere regarding the intensification of work. We do find a rela-tionship between work intensification and the negative outcomes of job dissat-isfaction, fatigue, job stress and imbalance between work and non-work life.Perceived overload in an employee’s work role and perceptions of pressurefrom managers to take work home, work overtime or otherwise exceed one’scontracted hours appear to be more important than actual working hours forstress and fatigue, although all three intensification variables are associatedwith work–life imbalance and stress.

Our study does not rule out the possibility that managers may simultane-

HIWP, intensification and well-being 51

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 51

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

ously pursue strategies aimed at encouraging involvement while also inten-sifying work. This is quite likely, for example, when downsizing occurs butmanagement still wants to make better use of the skills and initiative of theemployees who remain (e.g. Bacon and Blyton 2001). In this kind of situation,however, our findings suggest the benefits for employees will be less thanoptimal.

Finally, it is of interest to note that, consistent with research by Haar andSpell (2004) and Guest (2002), we find that the availability of initiativesassumed to aid workers to balance their work and non-work lives does notappear to be associated with the employee well-being outcomes investigatedin the present study. We do not conclude from this that these policies are irrel-evant to worker well-being but think that future research needs to examinethe responses of workers who try to access them.

In sum, this study supports the view that managerial approaches thatintensify work, while perhaps generating organizational gains, are likely tohave negative outcomes for employees, while HPWSs which foster and rewardemployee involvement are likely to have clear benefits for them. Workplacereform which enables employees to work smarter through greater empower-ment, but without undue pressure to work harder, is likely to enhanceemployee well-being.

Keith Macky (PhD) is associate professor of human resource management in the Department of

Management at the Auckland University of Technology (AUT). He has more than 20 years’ HR

experience in both academic and consulting environments, including senior positions at Massey

University, Ernst & Young, and KPMG. He is the co-author (with Gene Johnson) of Managing human

resources in New Zealand.

Peter Boxall (PhD) is professor of human resource management in the Department of Management and

International Business at the University of Auckland. He is co-author with John Purcell of Strategy and

human resource management, co-editor (with John Purcell and Patrick Wright) of the Oxford handbook

of human resource management, and co-editor (with Richard Freeman and Peter Haynes) of What

workers say: Employee voice in the Anglo-American workplace.

References

Allen, T.D. 2001. Family-supportive work environments: the role of organizationalperceptions. Journal of Vocational Behavior 58: 414–35.

Appelbaum, E., T. Bailey, P. Berg, and A.L. Kalleberg. 2000. Manufacturing advantage: Why high-performance work systems pay off. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press.

Appleyard, M., and C. Brown. 2001. Employment practices and semiconductor manufac-turing performance. Industrial Relations 40: 436–71.

Aryee, S., E.S. Srinivas, and H.H. Tan. 2005. Rhythms of life: Antecedents and outcomes ofwork-family balance in employed parents. Journal of Applied Psychology 90(1): 132–46.

Bacon, N., and P. Blyton. 2001. High involvement work systems and job insecurity in the

52 Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 2008 46(1)

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 52

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

international iron and steel industry. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences 18(1):5–16.

Barker, J.R. 1993. Tightening the iron cage: Concertive control in self-managing teams.Administrative Science Quarterly 38(3): 408–37.

Becker, B., and B. Gerhart. 1996. The impact of human resource management onorganizational performance: Progress and prospects. Academy of Management Journal39(4): 779–801.

Beehr, T.A., J.T. Walsh, and T.D. Taber. 1976. Relationship of stress to individually andorganizationally valued states: Higher order needs as a moderator. Journal of AppliedPsychology 61(1): 41–7.

Brett, J.M., and L.K. Stroh. 2003. Working 61 plus hours a week: Why do managers do it?Journal of Applied Psychology 88(1): 67–78.

Cappelli, P., and D. Neumark. 2001. Do ‘high performance’ work practices improveestablishment level outcomes? Industrial and Labor Relations Review 54: 737–76.

Cook, J.D., S.J. Hepworth, T.D. Wall, and P.B. Warr. 1981. The experience of work. London:Academic Press.

Cooke, F.L. 2001. Human resource strategy to improve organizational performance: A routefor firms in Britain? International Journal of Management Reviews 3(4): 321–39.

Crampton, S.M., and J.A. Wagner. 1994. Percept–percept inflation in micro organizationalresearch: An investigation of prevalence and effect. Journal of Applied Psychology 79(1):67–76.

De Dreu, C.K., and L.R. Weingart. 2003. Task versus relationship conflict, team performanceand team member satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 88(4):741–49.

Delery, J.E. 1998. Issues of fit in strategic human resource management: implications forresearch. Human Resource Management Review 8(3): 289–309.

Delery, J.E., and J.D. Shaw. 2001. The strategic management of people in work organizations:Review, synthesis, and extension. Research in Personnel and Human ResourcesManagement 20: 65–197.

Department of Labour. 2003. Perceptions and attitudes towards work–life balance in NewZealand. Auckland: UMR Research Limited.

Dex, S., and S. Bond. 2005. Measuring work–life balance and its covariates. Work,Employment and Society 19(3): 627–37.

Ettner, S.L., and J.G. Crzywacz. 2001. Workers’ perceptions of how jobs affect health: A social ecological perspective. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 6(2): 101–13.

Frone, M.R., and J.K. Yardley. 1996. Workplace family-supportive programmes: Predictors ofemployed parents importance ratings. Journal of Occupational and OrganizationalPsychology 69(4): 351–66.

Frone, M.R., K.K. Yardley, and K.S. Markel. 1997. Developing and testing an integrativemodel of the work–family interface. Journal of Vocational Behavior 50: 145–67.

Gallie, D. 2005. Work pressure in Europe 1996–2001: Trends and determinants. BritishJournal of Industrial Relations 43(3): 351–75.

Godard, J. (2004). A critical assessment of the high-performance paradigm. British Journal ofIndustrial Relations 42(20: 349-378.

Green, F. 2004. Why has work effort become more intense? Industrial Relations 43(4): 709–41.Guest, D.E. 1999. Human resource management: The workers verdict. Human Resource

Management Journal 9(3): 5–25.Guest, D.E. 2002. Perspectives on the study of work–life balance. Social Science Information

41(2): 255–79.Guest, D.E., N. Conway, and P. Dewe. 2004. Using sequential tree analysis to search for

‘bundles’ of HR practices. Human Resource Management Journal 14(1): 79–96.Goddard, J. 2001. High performance and the transformation of work: The implications of

HIWP, intensification and well-being 53

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 53

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

alternative work practices for the experience and outcomes of work. Industrial andLabour Relations Review 54(4): 776–805.

Haar, J.M., and C.S. Spell. 2004. Programme knowledge and value of work–family practicesand organizational commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management15(6): 1040–55.

Hair, J.F., R.E. Anderson, R.L. Tatham, and W.C. Black. 1998. Multivariate data analysis. 5thedn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

House, R.J. and J.R. Rizzo. 1972. Role conflict and ambiguity as critical variables in a modelof organizational behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 7: 467–505.

Huselid, M.A. 1995. The impact of human resource management practices on turnover,productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal38(3): 635–72.

Jensen, J.B., and L. Kletzer. 2005. Tradable services: understanding the scope and impact ofservices offshoring. http://www.brookings.edu/es/commentary/journals/tradeforum/agenda2005.htm (accessed 3 April 2007).

Judge, T.A., J.W. Boudreau, and R.D. Bretz. 1994. Job and life attitudes of male executives.Journal of Applied Psychology 79(5): 767–82.

Judge, T.A., and J.A. Colquitt. 2004. Organizational justice and stress: The mediating role ofwork–family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology 89(3): 395–404.

Kalleberg, A., P. Marsden, J. Reynolds, and D. Knoke. 2006. Beyond profit? Sectoraldifferences in high-performance work practices. Work and Occupations 33(3): 271–302.

Karasek, R. 1979. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for jobredesign. Administrative Science Quarterly 24: 285–308.

Kline, T.J.B., L.M. Sulsky, and. S.D. Rever-Moriyama. 2000. Common method variance andspecification errors: A practical approach to detection. Journal of Psychology 134(4):401–21.

Knight-Turvey, N. 2004. High commitment work practices and employee commitment to theorganisation: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Paper presented at the18th Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management Conference, December, inDunedin, NZ.

Landsbergis, P.A., J. Cahill, and P. Schnall. 1999. The impact of lean production and relatednew systems of work organisation on worker health. Journal of Occupational HealthPsychology 4(2): 108–30.

Lawler, E.E. 1986. High-involvement management: Participative strategies for improvingorganizational performance. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Lawler, E.E., S.A. Mohrman, and G.E. Ledford. 1998. Strategies for high performanceorganisations: Employee involvement, TQM, and reengineering programs in Fortune 1000corporations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Liddicoat, L. 2003. Stakeholder perceptions of family-friendly workplaces: An examination ofsix New Zealand organisations. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 41(3): 354–70.

MacDuffie, J.P. 1995. Human resource bundles and manufacturing performance:organizational logic and flexible production systems in the world auto industry.Industrial and Labor Relations Review 48(2): 197–221.

Mackie, K.S., C.K. Holahan, and N.H. Gottlieb. 2001. Employee involvement managementpractices, work stress, and depression in employees of a human services residential carefacility. Human Relations 54(8): 1065–92.

Macky, K., and P. Boxall. 2007. The relationship between ‘high-performance work practices’and employee attitudes: An investigation of additive and interaction effects.International Journal of Human Resource Management 18(4): 537–67.

Pil, F.K., and J.P. MacDuffie. 1996. The adoption of high-involvement work practices.Industrial Relations 35(3): 423–55.

54 Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 2008 46(1)

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 54

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Podsakoff, P.M., and D.W Organ. 1986. Self-reports in organizational research: problems andprospects. Journal of Management 12(4): 531–44.

Podsakoff, P.M., S.B. MacKenzie, J. Lee, and N.P. Podsakoff. 2003. Common method biasesin behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies.Journal of Applied Psychology 88(5): 879–903.

Purcell, J. 1999. The search for ‘best practice’ and ‘best fit’: chimera or cul-de-sac?. HumanResource Management Journal 9(3): 26–41.

Ramsay, H., D. Scholarios, and B. Harley. 2000. Employees and high-performance worksystems: Testing inside the black box. British Journal of Industrial Relations 38(4): 501–31.

Sparks, K., C. Cooper, Y. Fried, and A. Shirom. 1997. The effect of hours of work on health:a meta-analytic review. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 70(4):391–409.

Statistics New Zealand. 2001. New Zealand standard classification of occupations 1999.Wellington: Statistics New Zealand.

Thompson, C.A., Beauvais, L.L., and K.S. Lyness. 1999. When work–family benefits are notenough: The influence of work–family culture on benefit utilization, organizationalattachment, and work–family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior 54: 392–415.

Vandenberg, R.J., H.A. Richardson, and L.J. Eastman. 1999. The impact of high involvementwork processes on organisational effectiveness: A second order latent variable approach.Group and Organisational Management 24(1): 300–39.

Wall, T., M. Corbett, R. Martin, C. Clegg, and P. Jackson. 1990. Advanced manufacturingtechnology, work design and performance: A change study. Journal of Applied Psychology75(6): 691–97.

Warr, P.B. 1994. A conceptual framework for the study of work and mental health. Work andStress 8: 84–97.

Warr, P., J. Cook, and T. Wall. 1979. Scales for the measurement of some work attitudes andaspects of psychological well-being. Journal of Occupational Psychology 52: 129–48.

Way, S. 2002. High performance work systems and intermediate indicators of firmperformance within the US small business sector. Journal of Management 28(6): 765–85.

White, M., S. Hill, P. McGovern, C. Mills, and D. Smeaton. 2003. ‘High-performance’management practices, working hours and work–life balance. British Journal ofIndustrial Relations 42(2): 175–95.

Whitener, E.M. 2001. Do ‘high commitment’ human resource practices affect employeecommitment? A cross-level analysis using hierarchical linear modelling. Journal ofManagement 27: 515–35.

Wood, S. 1999. Family-friendly management: Testing the various perspectives. NationalInstitute Economic Review April: 99–116.

Wright, P.M., T.M. Gardner, and L.M. Moynihan. 2003. The impact of HR practices on theperformance of business units. Human Resource Management Journal 13(3): 21–36.

Yousef, D.A. 2002. Job satisfaction as a mediator of the relationship between job stressors andaffective, continuance, and normative commitment: A path analytical approach.International Journal of Stress Management 9(2): 99–112.

HIWP, intensification and well-being 55

APJHR 46_1_Macky.qxd 4/02/2008 9:11 PM Page 55

© 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. at Univ of Auckland Library on April 30, 2008 http://apj.sagepub.comDownloaded from