Grand Opportunities: Strategies for Addressing Grand Challenges in Organismal Animal Biology

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Grand Opportunities: Strategies for Addressing Grand Challenges in Organismal Animal Biology

AUTHOR/EDITOR QUERIES

Article ID: ICB-icr052

Please respond to all queries and send any additional proof corrections. Failure to do so could

result in delayed publication

Query No Section Paragraph Query

Q1. Author names Please check that all names have been spelled

correctly and appear in the correct order. Please

also check that all initials are present. Please

check that the author surnames (family name)

have been correctly identified by a pink

background. If this is incorrect, please identify

the full surname of the relevant authors.

Occasionally, the distinction between surnames

and forenames can be ambiguous, and this is to

ensure that the authors’ full surnames and

forenames are tagged correctly, for accurate

indexing online. Please also check all author

affiliations.

Q2. Please spell out/define ESA, REU

Q3. Funding Remember that any funding used while

completing this work should be highlighted in

a separate Funding section. Please ensure that

you use the full official name of the funding

body.

Q4. Figure Figure has been placed as close as possible to

its first citation. Please check that it has no

missing sections and that the correct figure

legend is present.

MAKING CORRECTIONS TO YOUR PROOF These instructions show you how to mark changes or add notes to the document using the Adobe Acrobat Professional version 7.0 (or onwards) or Adobe Reader 8 (or onwards). To check what version you are using go to Help then About. The latest version of Adobe Reader is available for free from get.adobe.com/reader.

For additional help please use the Help function or, if you have Adobe Acrobat Professional 7.0 (or onwards), go to http://www.adobe.com/education/pdf/acrobat_curriculum7/acrobat7_lesson04.pdf

Displaying the toolbars

Adobe Reader 8: Select Tools, Comments & Markup, Show Comments and Markup Toolbar. If this option is not available, please let me know so that I can enable it for you.

Acrobat Professional 7: Select Tools, Commenting, Show Commenting Toolbar.

Adobe Reader 10: To edit the galley proofs, use the comments tab at the top right corner.

Using Text Edits

This is the quickest, simplest and easiest method both to make corrections, and for your corrections to be transferred and checked.

1. Click Text Edits

2. Select the text to be annotated or place your cursor at the insertion point.

3. Click the Text Edits drop down arrow and select the required action. You can also right click on selected text for a range of commenting options.

Pop up Notes

With Text Edits and other markup, it is possible to add notes. In some cases (e.g. inserting or replacing text), a pop-up note is displayed automatically.

To display the pop-up note for other markup, right click on the annotation on the document and selecting Open Pop-Up Note.

To move a note, click and drag on the title area.

To resize of the note, click and drag on the bottom right corner.

To close the note, click on the cross in the top right hand corner.

To delete an edit, right click on it and select Delete. The edit and associated note will be removed.

SAVING COMMENTS In order to save your comments and notes, you need to save the file (File, Save) when you close the document. A full list of the comments and edits you have made can be viewed by clicking on the Comments tab in the bottom-left-hand corner of the PDF.

NOT FORPUBLIC RELEASE

//cephastorage2/Journals/application/oup/ICB/icr052.3d

[18.5.2011–2:25pm] [1–7] Paper: icr052

Copyedited by: PSB MANUSCRIPT CATEGORY: GRAND CHALLENGES

GRAND CHALLENGES

Grand Opportunities: Strategiesfor Addressing Grand Challenges

5in Organismal Animal BiologyJonathon H. Stillman,1,*,† Mark Denny,‡ Dianna K. Padilla,§ Marvalee Wake,† Sheila Patek� andBrian Tsukimura*,*

*Romberg Tiburon Center and Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, 3150 Paradise Drive, Tiburon,

10 CA 94920, USA; †Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, Valley Life Sciences Bldg Berkeley,

CA 94720-3140, USA; ‡Hopkins Marine Station, Stanford University, 120 Oceanview Blvd. Pacific Grove CA 93950, USA;§Department of Ecology and Evolution, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794-5245, USA; �Department of

Biology, 221 Morrill Science Center, 611 North Pleasant Street, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003,

USA; **Department of Biology, California State University, Fresno, 2555 E. San Ramon Avenue, MS#SB73, Fresno,

15 CA 93740, USA

1E-mail: [email protected]

The Biology Directorate at the

National Science Foundation

20 (NSF) has requested that organis-

mal biologists develop a vision

and articulate the grand research

challenges that will drive the

future of organismal biology, and

25 the large-scale community-wide

efforts that would be needed to

address those challenges. Over

the past decade, organismal

animal biologists have been slow

30 to develop community-wide ini-

tiatives relative to other bioscience

communities (e.g. molecular biol-

ogists, ecologists, evolutionary bi-

ologists, and plant biologists). In

35 response to NSF’s request, the

Society for Integrative and

Comparative Biology (SICB) or-

ganized an effort to begin to ar-

ticulate grand visions of the

40 research questions that will form

the foundation of future research

in organismal animal biology

(hereafter referred to as ‘‘organis-

mal biology’’ for brevity). White

45 papers, now known as contribu-

tions in the ‘‘Grand Challenges

in Organismal Biology’’ (GCOB)

series, have been published in

Integrative and Comparative

50 Biology over the past 2 years

(Denny and Helmuth, 2009;

Denver et al., 2009; Satterlie

et al., 2009; Schwenk et al., 2009;

Mykles et al., 2010; Sih et al.,

55 2010). These papers define a

number of large-scale forward-

thinking research efforts that

cross the broad array of disci-

plines encapsulated by SICB and

60 move organismal biology in new

directions (1) genotype–pheno-

type relationships, (2) integrating

living and physical systems, (3)

utilizing functional diversity, (4)

65organism-environment linkages,

(5) evolutionary stability versus

change, (6) how non-model or-

ganisms work, (7) garnering

public support for organismal bi-

70ology, (8) transforming organis-

mal biology into 21st century

science, (9) fostering inter-

disciplinary and cross-disciplinary

research to yield emergent princi-

75ples about organisms, (10) com-

munity research efforts in

addressing GCOB, and (11) the

predictive power of organismal

biology in the context of ecologi-

80cal and evolutionary change.

Implementing GCOBs

At the 2010 SICB annual meeting

a workshop was held to initiate a

dialog across organismal biology

Integrative and Comparative Biology, pp. 1–7

doi:10.1093/icb/icr052

� The Author 2011. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology. All rights reserved.

[br]For permissions please email: [email protected]

NOT FORPUBLIC RELEASE

//cephastorage2/Journals/application/oup/ICB/icr052.3d

[18.5.2011–2:25pm] [1–7] Paper: icr052

Copyedited by: PSB MANUSCRIPT CATEGORY: GRAND CHALLENGES

that focused on how to address

the GCOBs articulated by SICB

(Tsukimura et al., 2010). A

number of presentations were

5 made by Executive Committee

members of SICB and other pro-

fessional societies to stimulate dis-

cussion. Major requirements for

implementation, including bridg-

10 ing research fields and new

interdisciplinary approaches to

education, were discussed at

length. Recommendations result-

ing from that workshop included

15 establishment of interdisciplinary

integrative research cooperatives

as a means of increasing activity

between large and small research

laboratories and expanding coor-

20 dinated research efforts beyond

NIH-listed model organisms, fa-

cilitated by sequencing the ge-

nomes of a wider range of

organisms. Much discussion cen-

25 tered on overcoming the vast ed-

ucational challenges to prepare

our students to become the scien-

tists able and ready to take on the

challenges of interdisciplinary in-

30 tegrative research spanning organ-

ismal biology and genomics.

Participants recognized that to

overcome that challenge, signifi-

cant shifts in the mechanics of

35 our educational efforts may be re-

quired. Scientific communication

at all levels from colleagues to

the general public needs improve-

ment. Sharing of information and

40 cooperation (not competition)

must be encouraged. Training

(and re-training) scientists to

enable them to access changing

technology and approaches

45 should be facilitated. We may

need to make difficult decisions

about whether ‘‘context’’ or ‘‘con-

tent’’ is more important for edu-

cational objectives that prepare

50 students for future research envi-

ronments. Participants agreed that

a mechanism for developing an

umbrella coalition is needed to

maintain discussion throughout

55 the year. Outcomes from the

2010 workshop that stood out as

important elements that will allow

us to address the grand challenges

were increased awareness of the

60 grand challenges and identified

foci, integration and education.

At the 2011 SICB meeting, a

second GCOB workshop was or-

ganized with the primary objec-

65 tive of engaging SICB members

in productive breakout discus-

sions to focus our effort to

develop a plan or plans for imple-

mentation of grand challenges,

70 and to move this process forward

at a more rapid pace.

SICB is not the only society

with members that are organismal

biologists, but SICB as a whole

75 possesses the breadth of research

approaches required to address

many of the GCOBs. However,

the complexity of GCOB ques-

tions requires novel collaborations

80 and attitudes about organismal

biology’s contributions to science

and society. SICB is well-poised to

play a leadership role among or-

ganismal biologists in addressing

85 GCOBs because of the broad ex-

pertise in our society and com-

mitment reflected by our

membership. Organismal biolo-

gists, such as those in SICB,

90 have the opportunity to shape

their own destiny with respect to

NSF’s long-term plans for funding

in organismal biology. To develop

our future, we must join in a

95 broadly accepted vision of our re-

search arenas at least 5–10 years

into the future. We must do

more than define GCOB ques-

tions: we must organize a vision

100 for how to marshal the expertise,

financial support, research facili-

ties, and communication channels

needed to address the GCOB

questions in ways that will be pro-

105 ductive and that will continue to

keep our efforts in organismal bi-

ology fresh and forward-thinking.

At the 2011 GCOB workshop,

participants were challenged to

110become involved in thinking

hard about the future of organis-

mal biology, and developing a

community-based approach to

meet the grand challenges.

115Grand-challenge

strategies in otherscientific communities

The 2011 SICB GCOB workshop

opened with a review of how pre-

120vious efforts had unfolded. Other

scientific communities have

moved forward in addressing

their own grand-challenge re-

search objectives. In many cases,

125major research programs have re-

sulted from coordinated efforts

that involve building community

interest, articulating that interest

in a series of workshops and

130white papers, and consolidation

of focus by the community to ad-

dress specific scientific goals and

identify (and obtain) required re-

sources to reach those goals. For

135example, the systematics commu-

nity initiated the ‘‘A Tree of Life

(AToL)’’ program with the initial

goal to identify evolutionary rela-

tionships among as many organ-

140isms as possible, especially at

higher levels of organization, and

in doing so address fundamental

and important problems in ecolo-

gy, agriculture, human health and

145society, and development of bio-

informatic resources. The current

focus among systematic biologists

is a mission to assess and map as

much of the Earth’s biodiversity

150as possible, thereby informing

conservation efforts to preserve

that biodiversity. The molecular

biology community involved in

plant sciences worked together be-

155ginning in the 1990s to launch an

initiative to sequence the genomes

of Arabidopsis (the primary model

species for plant biology) and all

of the major crop plants. While

160not every plant biologist

2 Grand Challenges

NOT FORPUBLIC RELEASE

//cephastorage2/Journals/application/oup/ICB/icr052.3d

[18.5.2011–2:25pm] [1–7] Paper: icr052

Copyedited by: PSB MANUSCRIPT CATEGORY: GRAND CHALLENGES

participated, there was over-

whelming support from the com-

munity in this initiative. In

response, NSF launched a series

5 of requests for proposal initiatives

beginning in 1998 and including

the Plant Genome Research

Program, the National Plant

Genome Initiative, Genome-

10 Enabled Plant Research,

Transferring Research from

Model Systems, Tools and

Resources for Plant Genome

Research, and for fiscal year

15 2010, Comparative Plant Genome

Sequencing. In 2000, the

Arabidopsis research community

proposed the ‘‘Arabidopsis 2010’’

project involving the determina-

20 tion of the function of every

gene in the Arabidopsis genome

by 2010. The plant community is

now working on their next large

vision, the 2020 project, as artic-

25 ulated in white papers (Raikhel,

2008). More recently, the plant

biology community has launched

the ‘‘iPlant collaborative,’’ a

cybernetwork designed to help

30 plant biologists develop interdisci-

plinary integrative research to ad-

dress grand challenges in plant

biology (http://www.iplantcolla

borative.org). Software engineers

35 at iPlant work to develop cyberin-

frastructure including ‘‘Discovery

Environments’’ to help biologists

work on grand challenges. iPlant

cyber-resources are allocated by a

40 community-representative iPlant

board of directors. Members of

the ecology and environmental

biology community have launched

a series of initiatives aimed at

45 solving large-scale grand chal-

lenges. In the early 1990s, the

Sustainable Biosphere Initiative

was launched by ESA and resulted

in a series of workshops and white

50 papers that presented a 10-year

outlook for ecological sciences.

Centers and institutes including

the National Center for

Ecological Analysis and Synthesis

55 (NCEAS), the National

Evolutionary Synthesis Center

(NESCent), and the National

Institute for Mathematical and

Biological Synthesis (NIMBios)

60 have all shaped the way in which

ecologists frame and address

grand-challenge-scale questions.

In recent years, the ecology and

evolutionary biology community

65 has published a new set of white

papers to define the future of

these centers. Presently there is a

new competition for the next-

generation of a national environ-

70 mental synthesis center that will

stimulate research, education and

outreach at the interface of the

biological, geological and social

sciences.

75 Organismal biologists are now

in the early stages in developing

community-wide initiatives such

as those undertaken by the sys-

tematics community, plant biolo-

80 gists, and ecological and

evolutionary biology communi-

ties. We have articulated ideas

about grand challenges in organ-

ismal biology through SICB work-

85 shops and synthetic white papers

(Denny and Helmuth, 2009;

Denver et al., 2009; Satterlie

et al., 2009; Schwenk et al., 2009;

Evans et al., 2010; Mykles et al.,

90 2010; Robinson et al., 2010; Sih

et al., 2010). A group of organis-

mal animal biologists with pri-

mary affiliation in the American

Physiological Society (APS) held

95 a workshop in 2007 to discuss

developing a National Center

Network for Physiological

Research, Integration, Synthesis

and Modeling (PRISM). The

100 stated goals of PRISM (Carey,

2007) were broad and

forward-looking, but PRISM’s ini-

tial efforts were directed toward

development of a center for re-

105 search on the physiology of large

mammals so as to preserve and

maintain present expertise, not

to develop a dynamic future for

organismal biology. PRISM’s ini-

110tial efforts have not gained trac-

tion, but discussion of PRISM at

the April, 2011 APS may substan-

tially shift the present goals of

PRISM. We hope to see increased

115discussion among organismal bi-

ologists allied with SICB and

APS so that we can work together

on scientist-based, not scientific-

society-based approaches to devel-

120oping the resources necessary to

address GCOBs.

How to start addressingGCOBs?

To encourage discussion of how a

125research community could meet

GCOBs, a strawman framework

was presented for how to progress

from a GCOB idea to garnering

the research support needed to

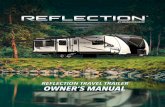

130address the GCOB (Fig. 1). In

this plan, SICB Executive

Officers would initiate the process

by formation of a grand challenge

steering committee (GCSC),

135which would work to identify

one focal interdisciplinary GCOB

question. The process of moving

from that question to a forward-

reaching 5–10 year research

140agenda then involves three

design/discussion loops. Loop 1

is a process that involves a small

group of selected field-leading sci-

entists, loop 2 involves a broader

145group of scientists and students,

and loop 3 involves a smaller

group of scientists working to

engage the community of organis-

mal biologists at large and the

150public, including funding agen-

cies, in the GCOB research

agenda. In loop 1 (Fig. 1), the

GCSC would identify relevant

fields (e.g., biology, physics,

155mathematics) pertinent to the

GCOB question and recruit lead-

ership participants from each of

those fields. Those participants

would work together to refine

160the GCOB focal question, produce

Grand Challenges 3

NOT FORPUBLIC RELEASE

//cephastorage2/Journals/application/oup/ICB/icr052.3d

[18.5.2011–2:25pm] [1–7] Paper: icr052

Copyedited by: PSB MANUSCRIPT CATEGORY: GRAND CHALLENGES

a white paper on novel interdisci-

plinary approaches to addressing

the refined GCOB question, and

hold a workshop with additional

5 participants. At the workshop

(Fig. 1, loop 2), participants

would interact in small subgroups

organized to encourage novel in-

terdisciplinary and emergent ideas

10 about how to address the refined

GCOB question, identify required

resources, and generate a research

plan. Subgroups would then be

shuffled to generate a new set of

15 interactions among participant,

and the process repeated until

the GCOB question and approach

to addressing the question had

been further refined (Fig. 1,

20 loop 3). This workshop would

result in a white paper explaining

both the process and the out-

come. This paper could be used

to identify public support for the

25 GCOB question, including net-

working with representatives

from funding agencies and/or

foundations. Another white

paper would then be issued to

30 communicate how the research

community would coordinate

their efforts in addressing the

GCOB question, and this white

paper, along with the others

35 could then be used as motivation

for funding agencies to launch

initiatives to support the sort of

work outlined in these workshops.

While abstract, members of the

40 audience did find the plan to res-

onate with their expectation of a

process that will ultimately ad-

dress GCOB questions.

As an exemplar of how a com-

45 munity could meet GCOBs, cur-

rent efforts in ecomechanics, the

interface between the fields of

ecology and biomechanics, were

presented. Researchers in ecology

50 and biomechanics have recently

become aware of the potential

utility of collaborative interaction,

but the scope and direction of

these interactions has not been

55 defined. To craft a definition, a

workshop [funded by the

Partnership for Interdisciplinary

Studies of the Coastal Ocean

(PISCO)] was held in September

60 2009 at the Friday Harbor

Laboratories. The outcome of

this workshop was a ‘‘manifesto’’

detailing the potential highlights

and roadblocks to fully develop-

65ing the field of ecomechanics.

Segments of this manifesto have

been published as review articles,

and there is the possibility that

the entire document (and its on-

70going revisions) will be made

available online. A second work-

shop (funded by the Society for

Experimental Biology) was held

in Cambridge, England, in

75March of 2011. The output of

this workshop will be a special

dedicated edition of the Journal

of Experimental Biology. The next

step for ecomechanics will be to

80gather feedback, from both bio-

mechanics and ecologists, on the

vision spelled out in products of

these workshops. The manner in

which feedback will be obtained

85has yet to be determined, but

could potentially take advantage

of the capabilities of web-based

‘‘social’’ networks. We anticipate

that feedback will allow fine-

90tuning of the vision for

Fig. 1. One proposed approach for initiating the development of SICB-based GCOB-implementation plan.

4 Grand Challenges

NOT FORPUBLIC RELEASE

//cephastorage2/Journals/application/oup/ICB/icr052.3d

[18.5.2011–2:25pm] [1–7] Paper: icr052

Copyedited by: PSB MANUSCRIPT CATEGORY: GRAND CHALLENGES

ecomechanics, from which re-

search agendas and the necessary

funding for such a research focus

can be established.

5 Participants’ discussion

Groups of workshop participants

were then tasked with discussing

the following two questions:

(1) How should a broad, cohesive

10 and long-term vision for or-

ganismal biology research be

developed?

(2) How can investment in this

long-term vision be sustained

15 and stimulated by organismal

biologists across all career

stages?

To facilitate small and productive

discussion groups, participants

20 were asked to distribute them-

selves among round tables. In all,

there were five discussion groups

with 8–10 people in each group.

Student scribes recorded the con-

25 tent of discussion. Discussion was

observed by SICB executive com-

mittee members as well as the di-

rector and program officers from

the NSF Division of Integrative

30 Organismal Systems. Following

discussion, each discussion group

was called on to articulate their

main thoughts on the two discus-

sion questions.

35 Developing a long-termvision

Ideas that emerged from the dis-

cussion of Question 1 involved

developing a SICB committee

40 (e.g., akin to the student and

postdoctoral affairs committee

via the SICB secretariat) that

would provide a leadership role

in developing GCOB activities.

45 Activities proposed included

workshops involving scientists at

a range of career stages, broaden-

ing interactions with other disci-

plines in animal biology as well as

50 in fields beyond biology, and

defining/refining a common

vision of the future of organismal

biology. The plant biology com-

munity has effectively organized

55 their Arabidopsis 2010 and

Arabidopsis 2020 (Raikhel, 2008)

projects around a 10-year research

activity plan, and so integrative

biologists may be well served by

60 adopting a similar long-range

vision to their activities.

Workshops should address

broad questions (e.g., how do or-

ganisms respond to a changing

65 environment) that have the po-

tential to engage organismal

biologists from across SICB direc-

torates (as well as other societies

such as APS, Society for

70 Developmental Biology, Animal

Behavior Society). The format of

workshops should encourage

cross-fertilization among faculty,

post-doctoral fellows and graduate

75 students in brain-storming ideas.

At these workshops, participants

should feel free to express ideas

without fear of intimidation or

reproach should their ideas be

80 deemed outrageous. The work-

shops should be summarized as

white papers intended to commu-

nicate broadly to interested mem-

bers of the research community,

85 and could serve as starting docu-

ments for cyberspace dialogs on

the subject through online

forums and wikis. In addition to

dialogs, this cyberinfrastructure

90 could also be developed with ap-

plications to encourage sharing of

data and meta-analyses and the

development of networks to coor-

dinate research

95 Broadening interaction with

other disciplines was viewed as a

component essential for address-

ing many GCOB research areas.

Overcoming communication bar-

100 riers will allow better cross-

understanding of our fields,

especially in terms of mutual un-

derstanding of the research chal-

lenges and specific questions.

105Interdisciplinary approaches aid

in merging intellectual approaches

and material resources needed to

address large challenging ques-

tions. Sharing facilities and equip-

110ment may improve cross-

fertilization of ideas by bringing

disparate groups together.

Interdisciplinary collaborations

require improving effectiveness in

115communicating research topics

and rationale for why a given re-

search area is important.

There was considerable discus-

sion of what position SICB ought

120to take regarding the focused

study of model versus non-model

organisms. The plant biology

community was successful in

their ultimate goals of crop-plant

125research by starting with the

Arabidopsis genome sequencing

project as an initial foray into se-

quencing a plant genome. Is it

possible for SICB scientists to

130come together in the way that

plant biologists have in the devel-

opment of models that will allow

us to address GCOBs from the

vantage of integrative and com-

135parative biology? Doing so will

allow greater vertical integration

among levels of biological com-

plexity, and enhance our under-

standing, for example, of how

140relationships between genes and

organisms vary in the context of

environmental change.

Sustaining a long-termvision by organismal

145biologists across allcareer stages

Ideas that emerged from discus-

sion of Question 2 principally

centered on developing ways to

150integrate research and educational

activities in a focused interdisci-

plinary setting. An exemplar for

how we have successfully done

this is the NSF-Polar Programs

155sponsored Antarctic biology

course. This international course

Grand Challenges 5

NOT FORPUBLIC RELEASE

//cephastorage2/Journals/application/oup/ICB/icr052.3d

[18.5.2011–2:25pm] [1–7] Paper: icr052

Copyedited by: PSB MANUSCRIPT CATEGORY: GRAND CHALLENGES

attracts biologists from across a

wide array of disciplines, and has

also attracted participants from

other scientific disciplines (e.g.,

5 engineering), all of whom have

an interest in understanding life

in the cold (and high and dry).

The Antarctic course successfully

merges across training stages

10 (from graduate students to

senior faculty), and provides an

ideal environment for establish-

ment of novel interdisciplinary

collaborations. The focal point of

15 this course away from a particular

biological problem (e.g., develop-

mental biology) to a broader

question (e.g., life in the cold) is

a key to the engagement of par-

20 ticipants and aids in addressing

the challenge that scientists from

disparate disciplines have diffi-

culty communicating with each

other when immersed in their

25 own field. This course helps biol-

ogists understand engineers and

vice-versa because both groups

are put in an environment (liter-

ally, Antarctica) where they must

30 think more broadly about what

they are doing and why they are

doing it.

Such opportunities for training

may presently be unique to

35 Antarctica, but they could be

developed elsewhere and for ad-

dressing different grand-challenge

questions. Summer courses at bi-

ological field stations (e.g., The

40 Marine Biological Laboratory,

Woods Hole Oceanographic

Institute, Friday Harbor

Laboratories, Hopkins Marine

Station) have traditionally been

45 wonderful immersion learning en-

vironments where students engage

in subjects that cannot be effec-

tively taught during a normal ac-

ademic term. New summer field

50 courses focusing on GCOB ques-

tions, and that bring expertise

from a wide array of approaches,

such as the Antarctic biology

course exemplar, could be very

55 successful. Course instructors,

like those in the Antarctic biology

course, would bring their own re-

search expertise to bear and also

have the needed perspective to

60 help bridge the disparate fields

represented. Potentially, the devel-

opment of national and/or re-

gional centers for GCOB research

could occur at these field stations

65 and part of the center’s mission

could be the summer GCOB

courses. Such national and re-

gional centers have been quite

successful in the European sys-

70 tems where research is focused

on a particular set of questions

and/or areas (e.g., The Alfred

Wegener Institute in Germany is

focused on polar marine biology).

75 These centers not only could pro-

vide both a place for intellectual

exchange and data mining, but

also could provide appropriate re-

search facilities for engaging in

80 actual work as required to address

the GCOB. The Crary laboratory

at McMurdo base in Antarctica

provides discussion rooms and

wet laboratories for the Antarctic

85 Biology course; that blend is an

integral aspect of the development

of new collaborative efforts. The

centers should provide shared

tools and resources and help

90 engage the community in science

through effective communication

and outreach.

To overcome the challenge of

educating future generations of

95 scientists such that they can

work seamlessly among different

scientific disciplines, both within

biology and between biology

and other fields, we need to de-

100 velop some novel educational

approaches that involve all career

stages, especially undergraduate,

graduate, and postdoctoral stu-

dents. Educational efforts in train-

105 ing students to be integrative,

interdisciplinary, and to have a

broad perspective must start

early. Novel undergraduate

majors, and perhaps new types

110of undergraduate degrees, could

be a great way to start. A sugges-

tion was made to establish a new

integrative organismal biology

graduate student and/or postdoc-

115toral funding opportunity specifi-

cally in topics related to

addressing grand challenges in

organismal biology through inter-

disciplinary approaches. Partici-

120pants would be expected to

engage in collaborative research

between at least two laboratories

representing different scientific

fields. For example, to understand

125organism-environment linkages,

one of the grand challenges

posed by Schwenk et al. (2009),

participants could work among

laboratories that specialize in biol-

130ogy, geosciences, engineering,

mathematics, and/or computer

sciences relevant to a specific re-

search question related to the

grand challenge. Those laborato-

135ries need not be located at the

same university, but must have

research areas that in combination

provide a new and effective way

of addressing the GCOB. Gradu-

140ate fellowships would involve ro-

tations among each of the

participant laboratories. Postdoc-

toral fellowships would also in-

clude REU funding so that the

145postdoctoral scholar would gain

experience in mentoring stu-

dents, and undergraduate students

would gain perspective on inter-

disciplinary approaches during

150the travel amongst participant

laboratories.

Cyberinfrastructure will likely

play an important role in the suc-

cessful maintenance of GCOB ef-

155forts, especially in facilitating

interdisciplinary communication.

SICB members and other integra-

tive organismal biologists could

launch a site modeled after

160iPlant in which datasets could be

standardized and used in integra-

tive meta-analyses, and through

6 Grand Challenges

NOT FORPUBLIC RELEASE

//cephastorage2/Journals/application/oup/ICB/icr052.3d

[18.5.2011–2:25pm] [1–7] Paper: icr052

Copyedited by: PSB MANUSCRIPT CATEGORY: GRAND CHALLENGES

which researchers from disparate

fields and physical locations

could work together to integrate

their approaches toward address-

5 ing GCOB questions. In addition

to iPlant, effective grand-

challenges cyberinfrastructure has

been developed by research com-

munities in engineering (http://

10 www.engineeringchallenges.org/)

and global health (http://www

.grandchallenges.org/), for exam-

ple. The engineering grand-

challenges site has interactive poll-

15 ing and discussion forums, as well

as dynamic content. Webinars

could be organized to engage par-

ticipants in GCOB discussions,

and online forums for further

20 discussion organized to enable

frequent open communication

among organismal biologists

specifically centered on GCOB

issues.

25 To keep a channel for discus-

sion open, we have established a

new website, (http://www.grand

challengesinbio.org/). At this site,

we have established a forum to

30 continue discussion on questions

1 and 2 from our workshop, as

well as other questions involving

which of the GCOB questions we

ought to be addressing first. Our

35 future directions may well flow

from a continued discussion

about what process we ought to

be following.

Finally, when moving forward

40 in a coordinated group effort in

seeking public support to trans-

form the ways in which we ap-

proach our science, we must be

mindful of GCOB questions of

45 social relevance, best approaches

in public communication, and

strategies for garnering public

support. Training in clear com-

munication with policy makers,

50 the media, and the general

public is needed for the majority

of our lead scientists, and getting

that training should be a priority.

Conclusions

55 We urge the SICB Executive

Committee to take interim

action and establish the infra-

structure needed to proceed with

the organization to develop and

60 meet the Grand Challenges in

Organismal Biology. As evidenced

in this document, a number of

useful suggestions about both the

challenges and the strategies for

65 meeting them have been pre-

sented. Now, leadership must

emerge that will organize, priori-

tize, and activate the efforts. We

cannot make progress by concen-

70 trating on the Grand Challenges

only once a year at our meetings.

We recommend that a Grand

Challenges Steering Committee

of members committed to the

75 effort be appointed immediately

with the mandate to determine

SICB’s initial foci, establish an

action plan, and designate the

leaders of each focus group, with

80 the expectation that each group

will develop a research or com-

munication activity and seek

funding for it. These groups

should then report substantive

85 progress at next year’s annual

meeting. Only by taking action

and developing focus can we

begin to determine our future.

Acknowledgments

90 We wish to thank all of the par-

ticipants of the workshop for their

intellectual input into this project.

Funding

This project was funded by the

95 National Science Foundation

(IOS- 1007750 to B.T.) and the

Society for Integrative and

Comparative Biology.

References

100 Carey H. 2007. One physiology. The

Physiol 50:49–54.

Denny M, Helmuth B. 2009.

Confronting the physiological bottle-

neck: a challenge from ecomechanics.

105Int Comp Biol 49:197–201.

Denver RJ, Hopkins PM,

McCormick SD, Propper CR,

Riddiford L, Sower SA,

Wingfield JC. 2009. Comparative en-

110docrinology in the 21st century. Int

Comp Biol 49:339–48.

Evans DH, Axelsson M, Beltz B,

Burggren W, Castellini M,

Clements KD, Crockett L,

115Gilmour KM, Henry RP, Hirose S,

Ip AYK, Londraville R, Lucu C,

Poertner H-O, Summers A,

Wright P. 2010. Frontiers in aquatic

physiology - grand challenge. Front

120Physiol 1:6.

Mykles DL, Ghalambor CK,

Stillman JH, Tomanek L. 2010.

Grand challenges in comparative

physiology: Integration across disci-

125plines and across levels of biological

organization. Int Comp Biol 50:6–16.

Raikhel N. 2008. 2020 vision for biolo-

gy: The role of plants in addressing

grand challenges in biology. Mol

130Plant 1:561–3.

Robinson GE, Banks JA, Padilla DK,

Burggren WW, Cohen CS,

Delwiche CF, Funk V, Hoekstra HE,

Jarvis ED, Johnson L,

135Martindale MQ, del Rio CM,

Medina M, Salt DE, Sinha S,

Specht C, Strange K, Strassmann JE,

Swalla BJ, Tomanek L. 2010.

Empowering 21st century biology.

140Bioscience 60:923–30.

Satterlie RA, Pearse JS, Sebens KP.

2009. The black box, the creature

from the black lagoon, august

krogh, and the dominant animal.

145Int Comp Biol 49:89–92.

Schwenk K, Padilla DK, Bakken GS,

Full RJ. 2009. Grand challenges in

organismal biology. Int Comp Biol

49:7–14.

150Sih A, Stamps J, Yang LH, McElreath R,

Ramenofsky M. 2010. Behavior as a

key component of integrative biology

in a human-altered world. Int Comp

Biol 50:934–44.

155Tsukimura B, Carey HV, Padilla DK.

2010. Workshop on the implementa-

tion of the grand challenges. Int

Comp Biol 50:945–7.

Grand Challenges 7